Abstract

Aortic stenosis (AS) is defined as severe in the presence of: mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, peak aortic velocity ≥4 m/s, and aortic valve area (AVA) ≤1 cm2 (or an indexed AVA ≤0.6 cm2/m2). However, up to 40% of patients have a discrepancy between gradient and AVA, i.e. AVA ≤1 cm2 (indicating severe AS) and a moderate gradient: >20 and <40 mmHg (typical of moderate stenosis). This condition is called ‘low-gradient AS’ and includes very heterogeneous clinical entities, with different pathophysiological mechanisms. The diagnostic tools needed to discriminate the different low-gradient AS phenotypes include colour-Doppler echocardiography, dobutamine stress echocardiography, computed tomography scan for the definition of the calcium score, and recently magnetic resonance imaging. The prognostic impact of low-gradient AS is heterogeneous. Classical low-flow low-gradient AS [reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)] has the worst prognosis, followed by paradoxical low-flow low-gradient AS (preserved LVEF). Conversely, normal-flow low-gradient AS is associated with a better prognosis. The indications of the guidelines recommend surgical or percutaneous treatment, depending on the risk and comorbidities of the individual patient, both for patients with classic low-flow low-gradient AS and for those with paradoxical low-flow low-gradient AS.

Keywords: Severe aortic stenosis, Low-flow low-gradient, Calcium score, TAVI, Aortic valve replacement

Introduction

Aortic stenosis (AS) is the most common valve disease in developed countries and the most frequently treated. Treatment decision is guided by (i) severity of stenosis, (ii) symptoms, and (iii) reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). According to the guidelines,1,2 AS is defined as severe in the presence of a mean gradient ≥40 mmHg, aortic peak velocity ≥4 m/s, and aortic valve area (AVA) ≤1 cm2 (or an indexed AVA ≤0.6 cm2/m2). In these patients, in the presence of symptoms and/or reduced ejection fraction (EF), surgical or percutaneous treatment of AS is indicated, as it significantly improves the outcome. On the other hand, AS is defined as moderate in the presence of AVA >1 and <1.5 cm2 and an average gradient >20 but <40 mmHg. However, up to 40% of patients have a discrepancy between gradient and AVA, i.e. an AVA ≤1 cm2 (indicating severe AS) and a moderate gradient: ≥ 20 and ≤40 mmHg (typical of moderate stenosis). This condition is called ‘low-gradient AS’. This discrepancy creates important diagnostic and therapeutic dilemmas, as it questions the severity of the AS and the indication for treatment. This complexity in the clinical management of AS derives from the high heterogeneity of the clinical phenotypes, each with different pathophysiological mechanisms, included under the term ‘low-gradient AS’.

Heterogeneity of low-gradient aortic stenosis

An essential element in understanding low-gradient AS is the relationship between the transaortic gradient and flow. In fact, according to the simplified Bernoulli equation, the transvalvular gradient is equal to 4 × V2, where V is the flow velocity. Therefore, even a small reduction in transaortic flow results in a significant reduction in the gradient, even in the presence of a significantly reduced valve area (known as ‘gradient pseudo-normalization’). On the other hand, a reduction in flow is associated with a reduction in the forces applied on the aortic cusps, resulting in less valve opening and less AVA (a phenomenon known as ‘pseudo-severe stenosis’). So, in the presence of a low-flow, the gradient can underestimate the severity of the stenosis, while the AVA can overestimate the severity of the stenosis. According to the guidelines, the low-flow state is defined by a stroke volume index (SVI) <35 mL/m21,2; the prognostic value of this cut-off has been recognized in multiple studies and meta-analyses.3–5

SVI represents the estimate of left ventricular function and is influenced by left ventricular contractility, geometry, and global haemodynamic overload (valvular-arterial impedance). Therefore, reduced transaortic flow can be observed both in the presence of a reduced LVEF, as in classical low-flow low-gradient AS, and in the presence of a preserved LVEF, as in paradoxical low-flow low-gradient AS. Conversely, even in the presence of normal SVI (≥35 mL/m2), severe AS with a gradient <40 mmHg can be observed in the presence of reduced arterial compliance. In these patients, the increased aortic stiffness can lead to a ‘dumping’ of the transvalvular gradient of severe AS.4 This condition is known as normal-flow, low-gradient AS.

The classic ‘low-flow low-gradient’ aortic stenosis

In patients with AS and left ventricular dysfunction, the clinical entity classically referred to as ‘low-flow, low-gradient AS’ is configured. Typically, these patients have AVA ≤1 cm2, mean gradient <40 mmHg, and EF <50%. This clinical phenotype is present in 5–10% of patients with AS, is more common in men and is often associated with coronary artery disease, left ventricular dilation and functional mitral insufficiency.4 Reduced EF may be secondary to AS-related overload and/or intrinsic myocardial contractile dysfunction.

The pivotal diagnostic element in the management of this population is represented by the distinction between severe AS with a reduced gradient (due to ventricular contractile deficit) and pseudo-stenosis in which the aortic valve, not severely stenotic per se, presents an incomplete opening (secondary to reduced transvalvular flow related to low EF). This discrimination can be carried out with the use of low-dose dobutamine stress echocardiography (DSE; max 20 micrograms/kg/min) which allows to evaluate the presence of contractile reserve and the consequent increase in transaortic flow.6 With adequate recruitment of contractile reserve, severe AS shows an increase in the gradient without an increase of the AVA; on the other hand, the pseudo-stenosis shows a lack of/or scarce increase in the gradient but a significant increase in AVA over 1 cm2. However, some patients have a contractile reserve that is not sufficient to normalize transvalvular flow with persistent discordance between reduced AVA and low-gradient. In these patients it may be useful, as proposed by the researchers of the TOPAS study (Truly or Pseudo-Severe Aortic Stenosis), to evaluate the so-called ‘projected AVA’, i.e. the area that the patient would have had if a normal flow (250 mL/s) would have be obtained during the test.4 Finally, about one-third of patients undergoing DSE has no contractile reserve (i.e. they show an increase in stroke volume <20% during the test) and this does not allow the definition of the true severity of the stenosis. In these patients, the study of the calcium score on the aortic valve with the computed tomography (CT) scan may be useful to discriminate true severe AS from pseudo-stenosis. The cut-offs used to define severe AS are: Agaston Units (AU) ≥1200 in women and ≥2000 in men.4

The paradoxical low-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis

This clinical entity occurs in patients whose LVEF is normal. The diagnostic criteria are: AVA ≤1 cm2 (or indexed AVA ≤0.6 cm2/m2), mean gradient <40 mmHg, LVEF≥ 50% and low transaortic flow, i.e. SVI ≤35 mL/m2. It is present in 5–25% of patients with AS and is more frequent in women and in the elderly and is often associated with a history of hypertension. Typically, the left ventricle is highly hypertrophic with concentric remodelling, small ventricular volumes, and restrictive pathophysiology resulting in reduced flow despite normal EF. In this situation, DSE is not useful because it is unable to guarantee an increase in flow due to the morphological characteristics of the ventricle and frequently induces side effects that preclude its use (obstruction to the outflow, hypotension, etc.). Conversely, a Doppler Velocity Index <0.25, which is the ratio between the maximum velocity of flow on the left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) and on the aortic valve, indicates severe AS. However, the essential investigation for defining the diagnosis of low-flow, low-gradient paradoxical AS is the calculation of the calcium score with the CT scan. This study provides an anatomical assessment of the severity of the stenosis, quantifying its calcifications. It has also been shown that the calcium score measured on the aortic valve correlates with hemodynamic parameters and with the outcome of patients with AS.4 The cut-offs that define severe AS are the same as for classic low-flow low-gradient AS, i.e. ≥1200 AU in women and≥ 2000 AU in men.

The normal-flow low-gradient aortic stenosis

This clinical phenotype of AS is characterized by LVEF >50%, normal transaortic flow, i.e. >35 mL/m2, AVA ≤1 cm2 (or indexed AVA ≤ 0.6 cm2/m2) and a gradient <40 mmHg. This pattern is present in up to 25% of patients with AS, and up to 50% of these AS are really severe.4 In addition to the presence of reduced vascular compliance and hypertension, these low-gradient AS can be explained by the intrinsic inconsistency of the cut-offs proposed by the guidelines to define severe AS. In fact, from a haemodynamic point of view, the 1 cm2 cut-off does not correspond to a gradient of 40 mmHg, but of 30–35 mmHg. To compensate for this discrepancy, some authors have proposed to use the cut-off of 0.8 cm2.4 However, since the 1 cm2 cut-off was shown to more accurately predict mortality, it was also retained in the definition of AS severity.

Practical guide to the diagnostic definition of low-gradient aortic stenosis

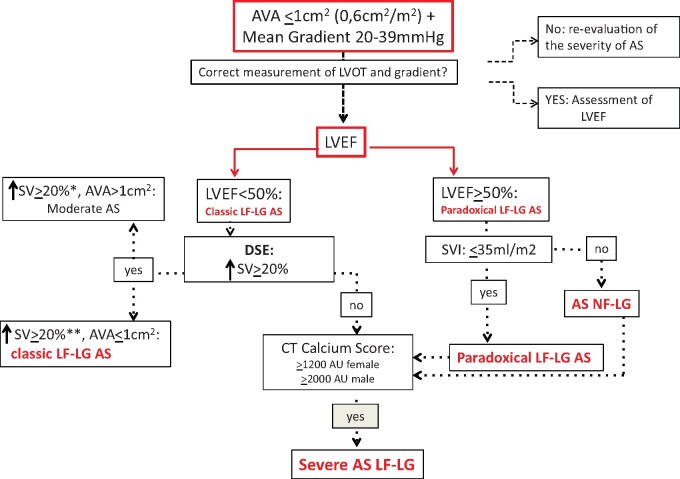

In clinical practice, the diagnostic definition of a low-gradient AS can be quite complex because there are many anatomical and flow parameters to consider. First of all, facing a patient with a moderate transaortic gradient (i.e. between 20 and 39 mmHg) and a Doppler area ≤1 cm2 (or indexed ≤0.6 cm2/m2) it is essential to verify that the valve has calcific cusps during the morphological evaluation, with reduced excursion and anatomic AVA ≤1 cm2. In fact, an anatomic AVA >1 cm2 excludes the presence of a severe AS. The next step is to verify: (i) that the Doppler interrogation of the stenosis was performed in all recommended echocardiographic windows (including the right parasternal), in order not to underestimate the gradient and (ii) that the LVOT measurements were performed correctly and exactly at the point of insertion of the cusps, as recommended for the quantification of AS.4 In fact, in the continuity equation, an underestimation of the LVOT can result in an important overestimation of the severity of the AS (because the dimensions of the LVOT are squared in the calculation of the AVA). There are two methods to corroborate the measurement of the LVOT. Since the measurement of the LVOT is related to the body surface area (BSA), it can be calculated according to the following formula: diameter of the LVOT = (5.7 × BSA) + 12.1 mm.4 If the measurement obtained with echocardiography differs by more than 2 mm from the size predicted by the formula, it is necessary to think of a technical error and repeat the measurement. The other method is represented by the Doppler Velocity Index between LVOT and aortic valve which if <0.25 indicates a severe AS and indirectly corroborates the size of the LVOT, otherwise it is necessary to repeat the measurement. Once it is ascertained that the AVA is really ≤1 cm2 (or ≤indexed 0.6 cm2/m2), the next step is to evaluate the LVEF. If the EF is <50% we are facing with a classic low-flow low-gradient AS. In this case, it is necessary to proceed with a low-dose DSE which, in the presence of adequate contractile reserve, allows to discriminate between severe pseudo-stenosis (which is actually moderate) and a real severe AS. In the absence of adequate contractile reserve, it is necessary to perform a quantification of the calcium score on the aortic valve with the CT scan. If the EF is ≥50%, it is necessary to evaluate the SVI which if it is ≤35 mL/m2 indicates a paradoxical low-flow low-gradient AS, whether if it is >35 mL/m2 indicates a normal-flow low-gradient AS. In both cases, it is necessary to perform a CT scan to quantify the calcium score to confirm the diagnosis of severe AS. In the presence of calcium score values ≥1200 AU in women and ≥2000 AU in men, the diagnosis of severe AS can be considered certain.4 The diagnostic path of low-gradient AS is summarized in the flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Diagnostic flow chart. AS, aortic stenosis; AU, Agaston unit; AVA, aortic valve area; DES, dobutamine stress echocardiography; LF-LG, low-flow low-gradient; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract; NF-LF, normal-flow low-gradient; SVI, stroke volume index. aWithout significant gradient increase. bWith a significant increase in the gradient.

Low-gradient aortic stenosis prognosis

Patients with classic low-flow low-gradient AS have a particularly poor prognosis when managed with medical therapy.7,8 However, in these patients also the operative risk is very high, especially if treated surgically, with a 30-day mortality between 6% and 33%.9 Correct stratification of operative risk is therefore essential. DSE has been shown9 to adequately discriminate patients at higher operative risk (those with an increase in stroke volume <20%, risk of 22–33%) from those at lower risk (increase in stroke volume >20%, risk of 5–8%). However, the absence of flow reserve during echo-stress does not indicate that these patients cannot benefit from the treatment anyway, as removing the overload determined by severe AS from a dysfunctional ventricle can still be beneficial. In fact, a French multicentre study10 reported in a group of patients with classic low-flow low-gradient AS without flow reserve, who survived the surgery, a significant increase in LVEF, improvement of symptoms and a higher long-term survival than in medically treated patients. Furthermore, in the TOPAS-TAVI study11 the flow reserve was not correlated with cardiovascular mortality at 2 years. DSE therefore has an important role in the stratification of strictly operative risk, while it does not adequately predict the medium and long-term prognosis. Therefore, in the absence of flow reserve, the treatment of AS in patients with low EF should not be denied a priori. In these patients, the evaluation of the extent of myocardial fibrosis with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (RMC) could help in predicting the outcome.

The prognostic significance of the low-flow, low-gradient AS paradox has been more controversial in recent years. In fact, while many studies have confirmed the negative prognostic value12 demonstrated in the historical work of Hachicha,3 others have shown that the prognosis of these patients is more similar to that of patients with moderate AS.13 The heterogeneity of the populations studied and the possibility of diagnostic errors in the definition of the haemodynamic phenotype of AS can explain these discrepancies. However, in a meta-analysis,12 which included nine studies, involving over 3000 patients, it was shown that patients with low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS have an overall mortality similar to patients with high gradient AS and a higher mortality than those with normal-flow low-gradient AS (who had the best outcome). The negative prognostic impact of low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS has recently been confirmed in a population of patients followed for 7 years.14 However, patients with low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS have, compared to patients with severe high gradient AS, more comorbidities, they are more frequently women, are older, have a restrictive pathophysiology and smaller aortic annular dimensions. This causes the operative risk of these patients to be higher. Indeed, the presence of low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS has been associated with a 67% increase in mortality compared to patients with severe high-gradient AS.7 However, in this population, aortic valve replacement (AVR) reduced mortality by 57%.7 Identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from treatment is a complex process that may require, in addition to flow assessment, assessment of intra-myocardial fibrosis and exclusion of infiltrative myocardial diseases such as wild type transthyretin amyloidosis that coexists with low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS in a non-negligible percentage of patients and which significantly impacts on the outcome.15

Low-gradient aortic stenosis therapy

Once it has been confirmed that the patient with low-gradient AS actually has severe AS, international guidelines agree on the indication for AVR, based on numerous (though not randomized) studies that have documented its efficacy.1,2 In patients with classic low-low flow low-gradient AS, both the American and European guidelines recognize a class I indication for AVR. On the other hand, in patients with low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS, the most recent American guidelines1 have increased the class of recommendation for the treatment of AS from IIa to I, provided that it is established that valvular problem is the main cause of symptoms. A similar up-grading will probably be followed in the forthcoming European guidelines. Finally, both guidelines do not provide specific indications for the treatment of normal-flow low-gradient AS. This reflects on the one hand the perception that this form of AS has a less severe prognostic impact and on the other, it recognizes the difficulty of a correct and homogeneous diagnostic classification of this phenotype.

Choice of the type of intervention

Surgical or transcatheter AVR [transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI)] represent the therapeutic options available for the treatment of severe AS. In particular, in the subset of patients with low-gradient AS, the choice between the two options must be individualized, made by the Heart Team and based on multiple factors that include surgical risk, age, and comorbidities of the patient. In recent years, the improvement of the TAVI technique and the good results obtained in randomized trials vs. surgery for the treatment of severe high gradient AS in patients with variable surgical risk profiles from high to low, have favoured the tendency to use TAVI increasingly early, both in terms of the patient’s age and in terms of the severity of AS. However, it should be noted that the major limitation of TAVI is represented by the lack of evidence on the long-term durability of the prosthesis (>5 years) and therefore in patients aged <65 years it would be preferable to choose surgical AVR.1 On the other hand, it has been suggested that in patients with low LVEF and moderate AS (AVA >1 cm2), TAVI may still be indicated as it reduces afterload and could result in a clinical benefit. This hypothesis is currently being evaluated in the TAVR-UNLOAD trial. Pending the results of this study, however, the criterion of the severity of the AS (AVA ≤1 cm2 or indexed ≤0.6 cm2/m2) is an essential element to indicate the intervention.

The evidence on TAVI in low-gradient AS derives from observational studies and registries that unanimously support the use of TAVI in this population, as TAVI was associated with lower mortality, shorter hospital stay and less bleeding. On the other hand, TAVI is burdened by a higher frequency of peri-valvular leak and need for pacemaker implantation.

In the individual patient, therefore, it is necessary to carefully evaluate numerous anatomical, hemodynamic and vascular factors by the Heart Team, as well as age and comorbidities to ensure the best therapeutic option. In particular, in patients with low LVEF, the surgical AVR is burdened by a particularly poor prognosis, therefore in these patients, the TAVI is certainly preferable, even if the peri-procedural complications such as the presence of a peri-valvular leak or the need implantation of a pacemaker can have a significant impact on prognosis. In patients with low-flow low-gradient paradoxical AS, age <65 years is a preference criterion for surgical AVR, while age ≥65 years may be a guiding criterion towards TAVI as these patients have important comorbidities that increase the risk of surgery even if they have normal EF.

Conclusions

The ‘low-gradient AS’ includes very heterogeneous clinical entities, with different pathophysiological mechanisms. Once the degree of severity has been confirmed, which implies a poor prognosis, surgical or percutaneous treatment is indicated, depending on the risk and comorbidities of the individual patient.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

- 1. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP 3rd, Gentile F, Jneid H, Krieger EV, Mack M, McLeod C, O'Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM 3rd, Thompson A, Toly C.. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021;143:e35–e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumgartner H, Falk V, Bax JJ, De Bonis M, Hamm C, Holm PJ, Iung B, Lancellotti P, Lansac E, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Rosenhek R, Sjögren J, Tornos Mas P, Vahanian A, Walther T, Wendler O, Windecker S, Zamorano JL; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2739–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hachicha Z, Dumesnil JG, Bogaty P, Pibarot P.. Paradoxical low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite preserved ejection fraction is associated with higher afterload and reduced survival. Circulation 2007;115:2856–2864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Clavel MA, Burwash IG, Pibarot P.. Cardiac imaging for assessing low-gradient severe aortic stenosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017;10:185–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Eleid MF, Goel K, Murad MH, Erwin PJ, Suri RM, Greason KL, Nishimura RA, Rihal CS, Holmes DR.. Meta-analysis of the prognostic impact of stroke volume, gradient, and ejection fraction after transcatheter aortic valve implantation. Am J Cardiol 2015;116:989–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. deFilippi CR, Willett DL, Brickner ME, Appleton CP, Yancy CW, Eichhorn EJ, Grayburn PA.. Usefulness of dobutamine echocardiography in distinguishing severe from nonsevere valvular aortic stenosis in patients with depressed left ventricular function and low transvalvular gradients. Am J Cardiol 1995;75:191–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clavel MA, Magne J, Pibarot P.. Low-gradient aortic stenosis. Eur Heart J 2016;37:2645–2657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sato K, Sankaramangalam K, Kandregula K, Bullen JA, Kapadia SR, Krishnaswamy A, Mick S, Rodriguez LL, Grimm RA, Menon V, Desai MY, Svensson LG, Griffin BP, Popović ZB.. Contemporary outcomes in low-gradient aortic stenosis patients who underwent dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e011168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pibarot P, Dumesnil JG.. Low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis with normal and depressed left ventricular ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60:1845–1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tribouilloy C, Lévy F, Rusinaru D, Guéret P, Petit-Eisenmann H, Baleynaud S, Jobic Y, Adams C, Lelong B, Pasquet A, Chauvel C, Metz D, Quéré J-P, Monin J-L.. Outcome after aortic valve replacement for low-flow/low-gradient aortic stenosis without contractile reserve on dobutamine stress echocardiography. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1865–1873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ribeiro HB, Lerakis S, Gilard M, Cavalcante JL, Makkar R, Herrmann HC, Windecker S, Enriquez-Sarano M, Cheema AN, Nombela-Franco L, Amat-Santos I, Muñoz-García AJ, Garcia del Blanco B, Zajarias A, Lisko JC, Hayek S, Babaliaros V, Le Ven F, Gleason TG, Chakravarty T, Szeto WY, Clavel M-A, de Agustin A, Serra V, Schindler JT, Dahou A, Puri R, Pelletier-Beaumont E, Côté M, Pibarot P, Rodés-Cabau J.. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis: the TOPAS-TAVI Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71:1297–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bavishi C, Balasundaram K, Argulian E.. Integration of flow-gradient patterns into clinical decision making for patients with suspected severe aortic stenosis and preserved LVEF: a systematic review of evidence and meta-analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9:1255–1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tribouilloy C, Rusinaru D, Maréchaux S, Castel A-L, Debry N, Maizel J, Mentaverri R, Kamel S, Slama M, Lévy F.. Low-gradient, low-flow severe aortic stenosis with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction: characteristics, outcome, and implications for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sen J, Huynh Q, Stub D, Neil C, Marwick TH.. Prognosis of severe low-flow, low-gradient aortic stenosis by stroke volume index and transvalvular flow rate. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14:915–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ternacle J, Krapf L, Mohty D, Magne J, Nguyen A, Galat A, Gallet R, Teiger E, Côté N, Clavel M-A, Tournoux F, Pibarot P, Damy T.. Aortic stenosis and cardiac amyloidosis: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74:2638–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]