Abstract

Four large trials have recently evaluated the effects of anti-inflammatory drugs in the secondary prevention of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in over 25 000 patients followed for 1.9–3.7 years. CANTOS tested subcutaneous canakinumab [an anti-interleukin (IL) 1β antibody] 300 mg every 3 months against placebo in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) and serum C-reactive protein (CRP) >2 mg/L, demonstrating efficacy in preventing MACE but increased rates of fatal infections. COLCOT (in patients with recent MI) and LoDoCo2 (in patients with chronic coronary syndromes) tested oral colchicine (an NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor) 0.5 mg daily vs. placebo, demonstrating prevention of MACE with a slightly increased risk of pneumonia in COLCOT (0.9 vs. 0.4%) but not in LoDoCo2. CIRT tested oral methotrexate (an anti-rheumatic anti-nuclear factor-kB) 15–20 mg per week against placebo in ischaemic heart disease patients with diabetes or metabolic syndrome, without significant reduction in MACE rates or in circulating IL6 or CRP levels, and with increased risk of skin cancers. In summary, canakinumab and colchicine have shown efficacy in preventing MACE in ischaemic heart disease patients, but only colchicine has acceptable safety (and cost) for use in secondary cardiovascular prevention. Clinical results are expected with the anti-IL6 ziltivekimab.

Keywords: Inflammation, Ischaemic heart disease, Atherothrombosis, Canakinumab, Colchicine

Introduction

Four large trials conducted in recent years have tested the hypothesis that anti-inflammatory drugs, such as canakinumab and colchicine, can reduce the incidence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with previous myocardial infarction (MI) or chronic coronary syndromes.1 To optimize the understanding of these studies we briefly illustrate the mechanisms of action of the tested drugs, the multiple aspects that relate inflammation to ischaemic heart disease, and some preliminary results with aspirin and ziltivekimab; the main findings of the large placebo-controlled trials with canakinumab, colchicine, and methotrexate are presented and their clinical implications briefly discussed.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and ischaemic heart disease

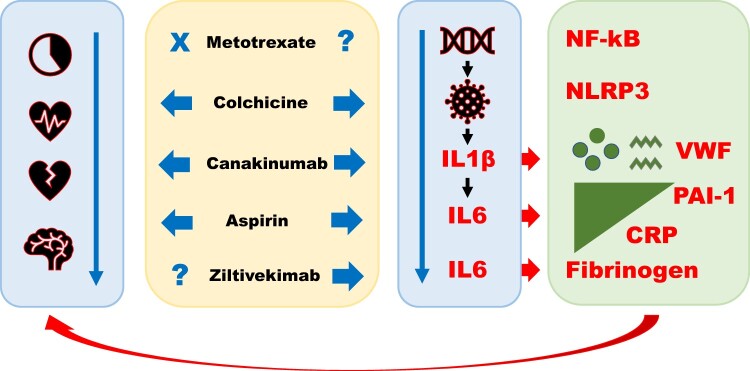

The anti-inflammatory effects of low-dose aspirin (100–300 mg/day), although less well known than its antiplatelet effects, are documented in various clinical settings2–4 and may contribute to aspirin’s benefits in the secondary prevention of MACE2; the exact molecular mechanisms of such effects are under investigation.2–4 Canakinumab is a recombinant human monoclonal G1k immunoglobulin against interleukin (IL) 1β that neutralizes the signals induced by IL1β on lymphoid, myeloid, endothelial, and other cell types; canakinumab administration reduces circulating IL6, fibrinogen, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels compared to placebo.1,5 Colchicine is a plant alkaloid that inhibits tubulin polymerization and the nod-like receptor pyrin domain containing protein-3 (NLRP3) inflammasome within monocytes and other cell types1; in vitro, colchicine is reported to reduce platelet aggregation, superoxide production, neutrophil recruitment and adhesion, mast cell degranulation, monocyte chemotaxis, endothelial pyroptosis by cholesterol crystals, and endothelial activation by oxidized LDL cholesterol1; in rats, colchicine has been found to inhibit hepatic secretion of fibrinogen causing fibrinogen accumulation within the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi apparatus6; rabbits subjected to hypercholesterolaemic diets treated with colchicine show reduced atherosclerotic development and reduced circulating fibrinogen levels7; in rodents, colchicine was found to protect against acute cerebral ischaemia by inhibiting cell chemotaxis and exocytosis.1 Methotrexate—used to treat rheumatic diseases and cancer—has multiple effects including inhibition of the nuclear transcription factor-kB, of DNA/RNA synthesis and of dihydrofolate reductase1; in patients with previous MI, methotrexate did not reduce circulating IL6 levels.8 Ziltivekimab is an anti-IL6 human monoclonal antibody; unlike antibodies directed against the IL6 receptor, ziltivekimab may act at lower concentrations causing fewer adverse events.9 The actions of the aforementioned drugs are schematically illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Anti-inflammatory drugs and ischaemic heart disease. Colchicine, canakinumab, and aspirin (but not low-dose methotrexate) have shown efficacy in preventing major adverse cardiovascular events in phase III trials of patients with ischaemic heart disease (left blue arrow). These three agents inhibit the inflammatory cascade at various levels, from the NLRP3 inflammasome to interleukin-1β and interleukin-6 (right blue arrow). Their administration leads to significant reductions in circulating levels of C-reactive protein and of prothrombotic factors such as fibrinogen and—presumably—plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 and von Willebrand factor. A phase III trial is planned with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherothrombotic risk. CRP, C-reactive protein; IL, interleukin; NF-kB, nuclear transcription factor-kB; NLRP3, nod-like receptor pyrin domain containing protein-3; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Inflammation and ischaemic heart disease

The close links between inflammation, atherothrombosis, and coronary syndromes have long been known, stemming from pathological, mechanistic, and clinical data (Table 1). Atherosclerosis itself has been defined as a chronic vascular inflammatory process.10 Unstable plaques have specific characteristics, with an increased share of macrophages and neutrophils compared to stable plaques.11 Coronary thrombi contain leucocytes, in addition to platelets, fibrin, and red cells.12 Various prothrombotic factors, such as fibrinogen (the precursor of fibrin and bridging molecule among aggregated platelets), plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (rapid inhibitor of endogenous fibrinolysis and profibrotic factor), and von Willebrand factor (platelet adhesion molecule), are acute phase proteins.13,14 As stated, in animal models, colchicine can slow the development of atherosclerosis7 and hepatic fibrinogen secretion.6,7 In humans, inhibition of IL1β or IL6 reduces circulating levels not only of other inflammatory cytokines and CRP but also of prothrombotic factors such as fibrinogen.5,9 The main traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidaemia, smoking, obesity, sedentary lifestyle) are associated with systemic low-grade inflammation: for each additional factor, an approximate increase of 1 mg/L of circulating CRP is observed.15 Subclinical low-grade inflammation increases the risk of MACE among healthy subjects: elevated fibrinogen concentrations16 and white blood cell counts,17 even within the normal range, are predictors of MACE. Common inflammatory markers predict the risk of MACE in patients with both acute18 and chronic19 coronary syndromes. In patients with chronic coronary syndromes, low-dose aspirin reduces the circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers and the incidence of inducible ischaemia.2 Finally, acute MI stimulates an acute-phase and prothrombotic response, with peak values and duration of response directly proportional to the extent of MI.12,13 Based on this extensive collection of data, phase II studies and recent large-scale trials have evaluated the effects of anti-inflammatory drugs for the secondary prevention of atherothrombotic events.

Table 1.

Multiple interrelations between inflammation and ischaemic heart disease

| Histopathology |

|

| Molecular and experimental data |

|

| Pathophysiology and prognostic data |

|

| Large randomized trials |

|

CRP, C-reactive protein; CV, cardiovascular; IL, interleukin; MI, myocardial infarction; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1; VWF, von Willebrand factor.

Selected phase II studies

RESCUE (Trial to Evaluate Reduction in Inflammation in Patients With Advanced Chronic Renal Disease Utilizing Antibody-Mediated IL-6 Inhibition) is a recent, double-blind, randomized US study that tested increasing doses of subcutaneous ziltivekimab (7.5, 15, or 30 mg monthly) vs. placebo in 215 patients with moderate to severe renal impairment and circulating CRP levels >2 mg/L considered to be at high risk for atherothrombotic events.9 The dose of 30 mg per month for three months vs. placebo reduced circulating CRP by 80%, fibrinogen by 35%, and lipoprotein(a) by 20%, with persistent results at 6 months and without excess adverse events. A large-scale trial will evaluate the efficacy and safety of ziltivekimab in secondary prevention of MACE.9

In another phase II study, patients with stable obstructive coronary artery disease, compared to age-matched healthy controls, had more than double the plasma concentrations of the inflammatory markers macrophage colony stimulating factor (800 vs. 372 pg/mL), IL6 (3.9 vs. 1.7 pg/mL), and CRP (1.25 vs. 0.23 mg/L; P < 0.01 for all comparisons).2 Patients with inducible ischaemia on ambulatory electrocardiogram, randomized in a double blind crossover fashion to aspirin 300 mg daily or placebo for 3 weeks, showed significantly reduced MCSF, IL6, and CRP plasma levels after aspirin vs. placebo (P < 0.05).2 MCSF was associated with ischaemic burden (P < 0.01) and low ischaemic threshold (P < 0.01) and, together with IL1β, with number of diseased epicardial arteries (P < 0.05).2 Significantly reduced inflammatory cytokine levels after aspirin (100 and 300 mg daily) have also been documented in healthy subjects3 and in patients with metabolic syndrome.4 Among chronic coronary syndrome patients, MCSF and CRP values are predictive of long-term adverse events.19

Large randomized placebo-controlled trials

CANTOS: Canakinumab ANti-inflammatory Trombosis Outcomes Study

CANTOS20 is a double blind, randomized study of over 10 000 patients followed for an average of 3.7 years. It compared three doses of canakinumab, a drug already approved for the treatment of rheumatic diseases (50, 150, or 300 mg subcutaneously every 3 months), against placebo. Patients had a history of MI, serum CRP levels >2 mg/L, and good control of other cardiovascular risk factors. At higher doses (300 mg every 3 months), canakinumab vs. placebo significantly reduced plasma levels of IL6 and CRP and the combined endpoint of cardiovascular death, nonfatal MI and nonfatal stroke: 3.9 vs. 4.5 events per 100 person-years [hazard ratio 0.86; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.75–0.99; P = 0.031]. The other two tested doses did not yield favourable results. Regarding safety, canakinumab was associated with a higher rate of fatal infections than placebo, with no significant difference in the rates of death from any cause. Canakinumab did not enter the cardiovascular therapeutic arena, mainly due to the high cost and potential risk of fatal sepsis. However, the study was very relevant in defining the role of the IL1/IL6/CRP cascade in the development of atherothrombotic events. The ongoing search for sustainable, safe and viable large-scale treatments has led to two other drug approaches in specific trials: low-dose methotrexate (CIRT) and low-dose colchicine (COLCOT and LoDoCo2).

CIRT: Cardiovascular Inflammation Reduction Trial

CIRT8 is a double blind, randomized study sponsored by the National Institutes of Health. It compared low-dose methotrexate (target 15–30 mg once weekly) vs. placebo in 4786 patients with previous MI or multivessel epicardial artery disease plus diabetes or metabolic syndrome followed for a median of 2.3 years. The primary endpoint was the classical triple composite of MACE, i.e. non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or cardiovascular death; subsequently, for a lower than expected event rate, hospitalization for revascularization from unstable angina was added. The results were disappointing: low-dose methotrexate did not reduce circulating levels of IL1β, IL6, or CRP, nor cardiovascular events vs. placebo (201 vs. 207; hazard ratio 0.96, CI 0.79–1.16). With methotrexate vs. placebo, there was an increased incidence of oral lesions, leucopenia, unwanted weight loss, transaminase elevation, and cancer (mostly non-basal cell skin cancers; 52 vs. 30, P = 0.02). For these reasons, the trial was terminated prematurely.

COLCOT: COLchicine Cardiovascular Outcome Trial

COLCOT21 is an independent, multinational study funded by the Canadian government. It randomized double-blindly 4745 patients with recent MI (within 30 days), regardless of CRP values, to colchicine (0.5 mg daily) or placebo. Patients were treated with optimal medical therapy and followed for a median of 2.3 years. The primary endpoint was the combination of cardiovascular death, resuscitated cardiac arrest, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, and revascularization for unstable angina. The primary endpoint was documented in 5.5% of patients treated with colchicine and in 7.1% treated with placebo, a significant relative reduction of 23% (hazard ratio 0.77, CI 0.61–0.96; P = 0.02). Treatment with colchicine had favourable effects on each individual component of the composite primary endpoint. All-cause mortality was not different in the two arms (43 deaths with colchicine vs. 44 with placebo). A higher rate of pneumonia was observed with colchicine vs. placebo, albeit with a low incidence (0.9% vs. 0.5%, P = 0.03), while the frequency of diarrhoea (9.7% vs. 8.9%) did not differ significantly in the two arms. Study limitations include the relatively short follow-up and the relatively small sample size, providing reliable answers for the entire population but not for specific subgroups.

COLCOT has confirmed the crucial role of inflammation in the progression of ischaemic heart disease by providing an effective, low cost, reasonably safe preventive treatment with a drug already known to the medical community for the treatment of gout, familial Mediterranean fever and pericarditis. The COLCOT results, however, cannot be generalized to all ischaemic heart disease patients, being limited to patients with recent MI, in whom the intensity of inflammation may be more relevant than in stable patients with either an old MI or no previous history of acute coronary syndromes.

LoDoCo2: Low-Dose Colchicine 2 trial

LoDoCo222 is a double blind, randomized study that tested low-dose colchicine (0.5 mg daily) vs. placebo in 5500 patients with documented obstructive epicardial artery disease, stable for at least 6 months, followed for a median of 2.4 years. It was conducted in Australia and the Netherlands, and funded by public and private foundations and a consortium of pharmaceutical companies. The primary endpoint was a composite of cardiovascular death, spontaneous (non-procedural) MI, ischaemic stroke, and ischaemia-driven coronary revascularization. The main secondary endpoint was the classical triple composite of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke. The results were, once again, favourable. The primary endpoint occurred in 6.8% of patients treated with colchicine and in 9.6% of patients treated with placebo, representing a highly significant relative reduction of 31% (hazard ratio 0.69, CI 0.57–0.83; P < 0.001). The primary secondary endpoint showed a relative reduction of 28% (absolute rate 4.2% with colchicine vs. 5.7% with placebo; hazard ratio 0.72, CI 0.57–0.92; P = 0.007), i.e. a significant reduction not only from a statistical but also from a clinical standpoint. Regarding safety, there were no significant differences in the rates of expected adverse events, such as pneumonia or gastrointestinal disturbances, between treatment arms. The incidence of non-cardiovascular death was numerically (but not statistically) higher with colchicine vs. placebo (0.7 vs. 0.5 events per 100 person-years; hazard ratio 1.51, CI 0.99–2.31). Subgroup analyses showed homogeneous effects in all analysed subgroups. An important study limitation was the lack of information on circulating levels of inflammatory indices before and after treatment.

Thus, LoDoCo2 and COLCOT appear to close the circle, confirming that inflammation is a determinant of ischaemic heart disease progression and atherothrombosis, and that anti-inflammatory drugs can prevent MACEs in patients with recent MI (COLCOT) or chronic coronary syndrome (LoDoCo2).

Conclusions and perspectives

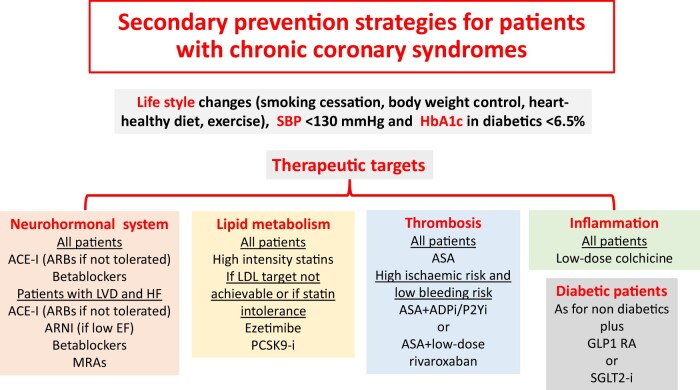

Recent large-scale placebo-controlled trials have confirmed the role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of atherothrombotic events by demonstrating that specific anti-inflammatory drugs are able to prevent MACE in patients with ischaemic heart disease. As a result, the therapeutic options for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events are expanding. CANTOS demonstrated a significant involvement of IL1β in atherothrombosis, and the colchicine trials have confirmed the benefits of anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with recent MI or chronic coronary syndromes using a well-known, reasonably safe and economical treatment. Inflammation can therefore be added to the three traditional therapeutic targets of atherothrombotic diseases (thrombosis, dyslipidaemia, neuroendocrine activation) (Figure 2).1 Forthcoming international guidelines will very likely provide indications on the use of colchicine for the secondary prevention of MACE. The addition of a new drug to existing ones will trigger discussion on the problem of medical adherence, for both prescribers and patients, and may stimulate de-prescribing strategies.1 Education on evidence-based medicine and, even more so, implementation strategies may be useful, including sharing health protocols within, among and out of hospitals.1 Research with colchicine is extending to other vascular fields—such as prevention of MACE in patients with previous stroke or transient ischaemic attack and prevention of nephropathy progression in patients with diabetes and microalbuminuria—as well as areas not strictly cardiovascular, such as coronavirus-2019 disease.1 The large-scale evaluation of the specific IL6 inhibitor, ziltivekimab, will provide further interesting data.9

Figure 2.

Secondary prevention strategies in patients with chronic coronary syndromes. Future clinical guidelines on the management of chronic coronary syndromes will likely include anti-inflammatory strategies. ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ASA, aspirin; EF, ejection fraction; GLP1 RA, glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonist; Hb, haemoglobin; HF, heart failure; i, inhibitor; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LVD, left ventricular dysfunction; MRAs, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists; PCSK9, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; SBP, systolic blood pressure; SGLT2, sodium glucose cotransporter type 2.

Conflict of interest: F.A. reports receiving personal fees from Amgen, Bayer, BMS-Pfizer, Daiichi Sankyo, Medscape and Radcliffe Cardiology outside the present work. A.P.M. reports fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Fresenius, Novartis for participation in study committees outside the present work. The other authors report that they are unaware of any economical or personal conflict affecting the content of this work.

References

- 1. Maggioni AP, Iervolino A, Andreotti F.. Is it time to introduce anti-inflammatory drugs into secondary cardiovascular prevention: evidence from clinical trials? Vessel Plus 2021;5:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ikonomidis I, Andreotti F, Economou E, Stefanadis C, Toutouzas P, Nihoyannopoulos P.. Increased proinflammatory cytokines in patients with chronic stable angina and their reduction by aspirin. Circulation 1999;100:793–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. von Känel R, Kudielka BM, Metzenthin P, Helfricht S, Preckel D, Haeberli A, Stutz M, Fischer JE.. Aspirin, but not propranolol, attenuates the acute stress-induced increase in circulating levels of interleukin-6: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Brain Behav Immun 2008;22:150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Gao X-R, Adhikari CM, Peng L-Y, Guo X-G, Zhai Y-S, He X-Y, Zhang L-Y, Lin J, Zuo Z-Y.. Efficacy of different doses of aspirin in decreasing blood levels of inflammatory markers in patients with cardiovascular metabolic syndrome. J Pharm Pharmacol 2009;61:1505–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ridker PM, Howard CP, Walter V, Everett B, Libby P, Hensen J, Thuren T; CANTOS Pilot Investigative Group. Effects of interleukin-1β inhibition with canakinumab on hemoglobin A1c, lipids, C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and fibrinogen: a phase IIb randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Circulation 2012;126:2739–2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feldmann G, Maurice M, Sapin C, Benhamou JP.. Inhibition by colchicine of fibrinogen translocation in hepatocytes. J Cell Biol 1975;67:237–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wójcicki J, Hinek A, Jaworska M, Samochowiec L.. The effect of colchicine on the development of experimental atherosclerosis in rabbits. Pol J Pharmacol Pharm 1986;38:343–348. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Pradhan A, MacFadyen JG, Solomon DH, Zaharris E, Mam V, Hasan A, Rosenberg Y, Iturriaga E, Gupta M, Tsigoulis M, Verma S, Clearfield M, Libby P, Goldhaber SZ, Seagle R, Ofori C, Saklayen M, Butman S, Singh N, Le May M, Bertrand O, Johnston J, Paynter NP, Glynn RJ; CIRT Investigators. Low-dose methotrexate for the prevention of atherosclerotic events. N Engl J Med 2019;380:752–762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ridker PM, Devalaraja M, Baeres FMM, Engelmann MDM, Hovingh GK, Ivkovic M, Lo L, Kling D, Pergola P, Raj D, Libby P, Davidson M; RESCUE Investigators. IL-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab in patients at high atherosclerotic risk (RESCUE): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2021;397:2060–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ross R. Atherosclerosis—an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 1999;340:115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Crea F, Andreotti F.. The unstable plaque: a broken balance. Eur Heart J 2009;30:1821–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishihira K, Yamashita A, Ishikawa T, Hatakeyama K, Shibata Y, Asada Y.. Composition of thrombi in late drug-eluting stent thrombosis versus de novo acute myocardial infarction. Thromb Res 2010;126:254–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Andreotti F, Roncaglioni MC, Hackett DR, Khan MI, Regan T, Haider AW, Davies GJ, Kluft C, Maseri A.. Early coronary reperfusion blunts the procoagulant response of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and von Willebrand factor in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol 1990;16:1553–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Andreotti F, Burzotta F, Maseri A, Fibrinogen as a marker of inflammation: a clinical view. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 1999;10(Suppl 1):S3–S4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bermudez EA, Rifai N, Buring J, Manson JE, Ridker PM.. Interrelationships among circulating interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and traditional cardiovascular risk factors in women. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2002;22:1668–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Meade TW, Mellows S, Brozovic M, Miller GJ, Chakrabarti RR, North WR, Haines AP, Stirling Y, Imeson JD, Thompson SG.. Haemostatic function and ischaemic heart disease: principal results of the Northwick Park Heart Study. Lancet 1986;2:533–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Castelli WP, D'Agostino RB.. Fibrinogen and risk of cardiovascular disease. The Framingham Study. JAMA 1987;258:1183–1186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Gallimore JR, Grillo RL, Rebuzzi AG, Pepys MB, Maseri A.. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid a protein in severe unstable angina. N Engl J Med 1994;331:417–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ikonomidis I, Lekakis J, Revela I, Andreotti F, Nihoyannopoulos P.. Increased circulating C-reactive protein and macrophage-colony stimulating factor are complementary predictors of long-term outcome in patients with chronic coronary artery disease. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1618–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, MacFadyen JG, Chang WH, Ballantyne C, Fonseca F, Nicolau J, Koenig W, Anker SD, Kastelein JJP, Cornel JH, Pais P, Pella D, Genest J, Cifkova R, Lorenzatti A, Forster T, Kobalava Z, Vida-Simiti L, Flather M, Shimokawa H, Ogawa H, Dellborg M, Rossi PRF, Troquay RPT, Libby P, Glynn RJ; CANTOS Trial Group. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N Engl J Med 2017;377:1119–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tardif J-C, Kouz S, Waters DD, Bertrand OF, Diaz R, Maggioni AP, Pinto FJ, Ibrahim R, Gamra H, Kiwan GS, Berry C, López-Sendón J, Ostadal P, Koenig W, Angoulvant D, Grégoire JC, Lavoie M-A, Dubé M-P, Rhainds D, Provencher M, Blondeau L, Orfanos A, L'Allier PL, Guertin M-C, Roubille F.. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine after myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2019;381:2497–2505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, Eikelboom JW, Schut A, Opstal TSJ, The SHK, Xu X-F, Ireland MA, Lenderink T, Latchem D, Hoogslag P, Jerzewski A, Nierop P, Whelan A, Hendriks R, Swart H, Schaap J, Kuijper AFM, van Hessen MWJ, Saklani P, Tan I, Thompson AG, Morton A, Judkins C, Bax WA, Dirksen M, Alings M, Hankey GJ, Budgeon CA, Tijssen JGP, Cornel JH, Thompson PL; LoDoCo2 Trial Investigators. Colchicine in patients with chronic coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2020;383:1838–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]