Abstract

Background:

The polymorphism Arg16 in β2-adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) gene has been associated with an increased risk of exacerbations in asthmatic children treated with long-acting β2-agonists (LABA). However, it remains unclear whether this increased risk is mainly attributed to this single variant or the combined effect of the haplotypes of polymorphisms at codons 16 and 27.

Objective:

We assessed whether the haplotype analysis could explain the association between the polymorphisms at codons 16 (Arg16Gly) and 27 (Gln27Glu) in ADRB2 and risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) plus LABA.

Methods:

The study was undertaken using data from ten independent studies (n = 5,903) of the multi-ethnic Pharmacogenomics in Childhood Asthma (PiCA) consortium. Asthma exacerbations were defined as asthma-related use of oral corticosteroids or hospitalizations/emergency department visits in the past 6 or 12 months prior to the study visit/enrolment. The association between the haplotypes and the risk of asthma exacerbations was performed per study using haplo.stats package adjusted for age and sex. Results were meta-analyzed using the inverse variance weighting method assuming random-effects.

Results:

In subjects treated with ICS and LABA (n = 832, age: 3–21 years), Arg16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Glu27 (OR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.05−1.87, I2 = 0.0%) and Arg16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Gln27 (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.05−1.94, I2 = 0.0%), but not Gly16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Glu27 (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.71−1.39, I2 = 0.0%), were significantly associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations. The sensitivity analyses indicated no significant association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and asthma exacerbations in the other treatment categories i.e., as-required short-acting β2-agonists (n = 973), ICS monotherapy (n = 2,623), ICS plus leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA; n = 338), or ICS plus LABA plus LTRA (n = 686).

Conclusion and clinical relevance:

The ADRB2 Arg16 haplotype, presumably mainly driven by the Arg16, increased the risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA. This finding could be beneficial in ADRB2 genotype-guided treatment which might improve clinical outcomes in asthmatic patients.

Keywords: asthma exacerbations, long-acting β2-agonists, inhaled corticosteroids, ADRB2, haplotypes

Graphical Abstract

Asthmatic children and young adults treated with inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) plus long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) were more prone to asthma exacerbations if they were carriers of ADRB2 haplotype (Arg16Gln27) compared to non-carriers. The ADRB2 Arg16 haplotype, presumably mainly driven by the Arg16, increased the risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA. This finding could be beneficial in ADRB2 genotype-guided asthma treatment and might improve patient outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a common, heterogeneous, and chronic respiratory disease. Despite treatment, patients might experience exacerbations that can be life-threating. The combination therapy of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) is one of the recommended treatments for the control of asthma in children.1 However, response to treatment with LABA varies inter-individually and this might be partly mediated by genetic variation.2

The β2-adrenergic receptor is a member of the G protein-coupled transmembrane receptors broadly located on airway smooth muscle cells.3 The β2-adrenergic receptor (ADRB2) gene, a small intron-less gene on chromosome 5q31.32, encodes the receptor and contains different single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Of these SNPs, the coding non-synonymous variants rs1042713 (Arg16Gly), a Glycine-to-Arginine amino acid substitution at codon 16, and rs1042714 (Gln27Glu), a Glutamine-to-Glutamic acid amino acid substitution at codon 27, that are in linkage disequilibrium, have been found to be associated with asthma and asthma phenotypes4–6

Although various studies have investigated the association between the ADRB2 polymorphisms and response to LABA, the results are conflicting and inconclusive.7–11 A recent meta-analysis in the Pharmacogenomics in Childhood Asthma12 (PiCA) consortium showed that asthmatic children carrying 1 or 2 Arg allele(s) at rs1042713 and treated with ICS plus LABA have an increased risk of exacerbations.10 Previous studies showed that the Gln allele at rs1042714 was a risk factor for asthma and associated with a less effective response to treatment with inhaled β2-agonists during an acute asthma exacerbation.6,13 Furthermore, most studies, as well as the recent meta-analysis in the PiCA consortium,10 evaluated the effect of each variant independently but not the combined effect of their haplotypes that might yield additional insight into the association between the ADRB2 variants and asthma exacerbations. Therefore, it is still unclear whether the combined effect of the ADRB2 polymorphisms at codons 16 and 27 is associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations or whether the association is driven by just the single polymorphism at codon 16.

Therefore, we aimed to assess whether the haplotype analysis could explain the association between the polymorphisms at codons 16 and 27 of ADRB2 and the risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA.

METHODS

Study population

Data from ten independent studies participating in the PiCA consortium12 were analyzed. BREATHE is an observational study that includes children and young adults (age: 3–22 years)14 with physician-diagnosed asthma recruited from primary and secondary care units in Tayside, Scotland, and Brighton, United Kingdom. The Effectiveness and Safety of Treatment with Asthma Therapy in children (ESTATe) is a case-control study that includes children and young adults (4–19 years) with physician-diagnosed asthma recruited from primary care units in the Netherlands. The followMAGICS study is the follow-up study of the observational Multicenter Asthma Genetics in Childhood Study (MAGICS), which includes physician-diagnosed asthmatic children and young adults (age: 7–25 years)15 recruited from secondary and tertiary centers in Germany and Austria. The Genes-Environment and Admixture in Latino Americans (GALA II) and the Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments (SAGE) studies are two independent case-control asthma cohorts (age: 8–21 years) that focus on two different racial/ethnic groups based on the self-identified ethnicity of the four grandparents of each subject: Hispanics/Latinos (GALA II) and African Americans (SAGE) in the United States and Puerto Rico.16,17 The Pharmacogenetics of Asthma Medication in Children: Medication with Anti- inflammatory effects (PACMAN) study in the Netherlands,18 is an observational cohort study that included children (age: 4–12 years) with self-reported regular use of asthma medication recruited through community pharmacies. Children were selected from community pharmacies in the Netherlands that belonged to the Utrecht Pharmacy Practice Network for Education and Research (UPPER).19 The Pediatric Asthma Gene Environment Study (PAGES) is a cross sectional observational study designed to relate asthma outcomes to environmental and genetic factors. Children (age: 5–16 years) with physician-diagnosed asthma were recruited from primary and secondary care centers across Scotland.20 The Pharmacogenetics of Adrenal Suppression Study (PASS) in the United Kingdom (age: 5–18 years) is a multicenter cohort of asthmatic children. The study initially aimed to explore the association between use of corticosteroids and adrenal suppression, and how genetic factors influence this association.21,22 The Singapore Cross Sectional Genetic Epidemiology Study (SCSGES)23 (age: 6–31 years) is an ongoing cross-sectional genetic epidemiology study on allergic diseases among Singapore Chinese individuals. The ethnicity of subjects was self-reported Chinese and confirmed by principal component analysis. Asthma was defined by having a physician-diagnosis of symptoms prior to recruitment.23,24 The SLOVENIA study is a case-control cohort (age: 5–18) and includes asthmatic children and young adults recruited from tertiary health centers from Murska Sobota, Slovenia.25 Further details on the study population are described in the Supporting Information.

All studies have been approved by their local medical ethics committees/institutional review boards and parents or participants provided written consent. The Tayside Committee on Medical Research Ethics (Dundee, United Kingdom) approved BREATHE (reference number: NFB/FB/106/03). ESTATe was approved by the Medische Ethische Toetsings Commissie, Erasmus Medical Center (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) (reference number: MEC-2011–474). GALA II and SAGE were approved by the Human Research Protection Program Institutional Review Board of the University of California, San Francisco (San Francisco, United States) (reference numbers: 10–00889 and 10–02877, respectively). PACMAN was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the University Medical Centre Utrecht (Utrecht, the Netherlands reference number: NL2124.021.08). PAGES has been approved by the Cornwall and Plymouth Research Ethics Committee (reference number: 07/H0203/204). PASS was approved by the Liverpool Pediatric Research Ethics Committee (Liverpool, United Kingdom, reference number: 08/H1002/56). SLOVENIA was approved by the Slovenian National Medical Ethics Committee (Ljubljana, Slovenia, reference number: 0120–569/2017/4). The Ethik- Kommission der Bayerischen Landesärztekammer (Munich, Germany) (reference number: 01218) and ethics committee of the medical University of Hannover (reference number: 1021–2011) approved followMAGICS. The ethical approval for the SCSGES cohort was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the National University of Singapore (NUS-IRB), reference numbers: 07–023, 09–256, 10–343, 10–445 and 13–075 for the large scale epidemiology and genetics study and the Institutional Review Board of the National Healthcare Group Domain, Specific Review Board - B/04/055.

Medication data

Data on asthma treatment was collected either from pharmacy records, parent/patient-reported medication use, or completed study questionnaires (PACMAN, followMAGICS, BREATHE, GALA II, PAGES, SAGE, and SCSGES) or physician prescriptions and pharmacy records (ESTATe, PASS, and SLOVENIA). Asthma treatment was categorized as follows: (1) as-required short-acting β2-agonists (SABA) (2) inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) monotherapy, (3) ICS in combination with LABA, (4) ICS in combination with leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA), and (5) ICS in combination with LABA and LTRA. All children in categories 2–5 used as-required SABA.

Main outcome

Asthma exacerbations, the main outcome, were defined based on the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) guidelines as episodes of worsening of asthma symptoms which require a short course (3–5 days) of oral systemic corticosteroids (OCS) use, hospitalizations or emergency department (ED) visits.26 Cases were determined if subjects had at least one asthma exacerbation (described above) in the past 6 or 12 months prior to the study visit or enrolment.

Data on asthma exacerbations, asthma-related OCS use or hospitalizations/ED visits, were reported by the parent/child at the study visit or based on study questionnaires or physician records: 1) BREATHE, and PASS: hospitalizations or OCS use in the past six months preceding the study visit; 2) PACMAN: ED visits or OCS use in the past 12 months preceding the study visit; 3) GALA II, SLOVENIA, ESTATe, SAGE, PAGES, and SCSGES: hospitalizations/ED visits or OCS use in the past 12 months preceding the study visit. In followMAGICS, only data on asthma-related hospitalizations or ED visits were available in the past 12 months preceding the study visit.12

Genotyping

In BREATH and PAGES, genotypes were determined by using Taqman-based allelic discrimination assays on an ABI 7,700 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif)4,27 In followMAGICS, samples were genotyped using Illumina Sentrix HumanHap300 BeadChip array (Illumina, Inc.)15 In both GALA II and SAGE, samples were genotyped using the Axiom® LAT1 array (Affymetrix Inc.), and quality control (QC) procedures were performed as described previously.28,29 In PACMAN and ESTATe, samples were genotyped using the Illumina Infinium CoreExome-24 BeadChip (Illumina, Inc.).30 In PASS, genotyping was performed using the Illumina Omni Express 8v1 array (Illumina, Inc.). QC procedures and imputation are described elsewhere.22 In SCSGES, genotyping was conducted using Kompetitive Allele Specific PCR (KASP) genotyping platform (LGC, Inc). QC was performed based on the quality of clustering.23 In the SLOVENIA study, genotyping of 336 samples was performed with the Illumina Global Screening Array-24 v1.0 BeadChip (Illumina). QC procedures and imputation described elsewhere.30

Functional annotation of variants and expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analysis

We used HaploRegv4.1 (http://www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php)31 to retrieve all proxy SNPs in strong linkage disequilibrium (LD) (r2 threshold > 0.8, limit distance 100 kb, and population panel CEU using 1000 Genomes project) with rs1042713 and rs1042714 in ADRB2 and to assess the predicted functions of the variants including protein structure, effects on gene regulation, and splicing. We also checked the correlation of the SNPs and their proxies with the expression level of ADRB2 in whole blood using expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) data from Genenetwork.32

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to calculate means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was assessed for each SNP using a web program (http://www.oege.org/software/hwe-mr-calc.shtml) which uses the Pearson chi-squared test for HWE testing.33 In our main analysis, we analyzed the association between haplotype combinations of polymorphisms at codons 16 and 27 of the ADRB2 gene and asthma exacerbations in the category of children treated with ICS plus LABA. We used the haplo.stats package (version 1.7.7)34 in R adjusting for age and sex in each study separately, and the resulting odds ratios (ORs) were meta-analyzed. The statistical methods of the haplo.stats package assume that all subjects are unrelated and linkage phase of the genetic markers is unknown.34 To address potential heterogeneity between studies, we used the inverse variance weighting method assuming random-effects. We also reported I2 and Cochran’s Q-test of the meta-analysis.35 Forest plots were made using the ‘metafor’ package in R (version 3.3.3).36

Data on asthma-related OCS use were not available in followMAGICS. Therefore, in a sensitivity analysis, we repeated the haplotype analysis (as described above) separately for asthma-related hospitalizations/ED visits outcome as well as for asthma-related OCS use outcome. Furthermore, to test the robustness of our result in the treatment category of ICS plus LABA, we repeated the haplotype analysis (as described above) in the other treatment categories as follows; as-required SABA, ICS monotherapy, ICS plus LTRA, and ICS plus LTRA plus LABA. Since we investigated the association of haplotype combinations of two polymorphisms and asthma exacerbations, we considered a P-value less than 0.025 (0.05/2) for our main meta-analysis to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the study populations (for each study) are presented in Table 1. Data on age, sex, and treatment were available for 5,903 children and young adults. Out of these 5,903 subjects, data on asthma exacerbations were available in 5,726 subjects.

Table 1:

Characteristics of the study populations

| Characteristics | BREATHE | ESTATe | Follow MAGICS | GALA II | PACMAN | PAGES | PASS | SAGE | SLOVENIA | SCSGES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 998 | 101 | 167 | 1,618 | 791 | 722 | 384 | 740 | 212 | 170 |

| Male sex, % | 60.0 | 58.0 | 62.3 | 55.7 | 62.3 | 57.6 | 56.0 | 52.3 | 56.1 | 68.2 |

| Mean age, y (SD) | 10.2 (4.0) | 10.6 (4.2) | 17.3 (3.0) | 12.4 (3.2) | 8.7 (2.3) | 9.8 (3.7) | 11 (3.3) | 13.8 (3.5 ) | 10.8 (3.4) | 14.0 (6.4) |

| Ethnicity, n. (%) | ||||||||||

| Caucasian | 998 (100) | 96 (95) | 167 (100) | N/A | 711 (89.9) | 360 (50) | 384 (100) | N/A | 212 (100) | N/A |

| Hispanic | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,618.(100) | 3 (0.4) | N/A | N/A | 744 (100) | N/A | N/A |

| Asian | N/A | 1 (1) | N/A | N/A | 6 (0.8) | 11 (1.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | 170 (100) |

| African | N/A | 0 (0) | N/A | N/A | 9 (1.1) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mixed | N/A | 2 (2) | N/A | N/A | 53 (6.7) | 15 (2) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Unknown (missing) | N/A | 2 (2) | N/A | N/A | 9 (1.1) | 336 (46.5) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Treatment group, n. (%) | ||||||||||

| SABA alone | 173 (17.3) | 0 (0.0) | 25 (15.0) | 576 (35.6) | 80 (10.1) | 79 (10.9) | 0 (0.0) | 207 (27.9) | N/A | N/A |

| ICS alone | 562 (56.3) | 65 (64.0) | 39 (23.3) | 538 (33.2) | 497 (62.8) | 271 (37.6) | 29 (7.5) | 367 (49.6) | 212 (100) | 170 (100) |

| ICS + LABA | 142 (14.3) | 34 (34.0) | 84 (50.3) | 165 (10.2) | 148 (18.7) | 135 (18.7) | 126 (33.0) | 98 (13.2) | N/A | N/A |

| ICS + LTRA | 37 (3.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.4) | 208 (12.9) | 21 (2.7) | 65 (9.0) | 0 (0.0) | 35 (4.7) | N/A | N/A |

| ICS + LABA + LTRA | 84 (8.4) | 2 (2.0) | 15 (9.0) | 131 (8.1) | 45 (5.7) | 172 (23.8) | 229 (59.5) | 33 (4.6) | N/A | N/A |

| Asthma exacerbations in the past year or in the last six months prior to the study visit/enrolment | ||||||||||

| Hospitalizations/ED*, n. (%)# | 147 (14.7) | 13 (12.9) | 11 (6.6) | 865 (54.8) | 42 (5.5) | 151 (21.7) | 290 (75.5) | 272 (39.0) | 49 (27.7) | 34 (20.0) |

| OCS use*, n. (%)# | 234 (23.4) | 36 (35.6) | N/A | 587 (37.4) | 46 (5.8) | 316 (45.7) | 198 (51.6) | 162 (22.4) | 23 (12.9) | 36 (21.2) |

| Asthma exacerbations*, n. (%)# | 250 (25.0) | 49 (48.5) | N/A | 1,013 (64.3) | 75 (9.7) | 346 (50.0) | 331 (86.2) | 317 (45.8) | 54 (30.3) | 59 (34.7) |

N/A. Not Applicable

ED, emergency department visits; OCS use, oral corticosteroids use; Asthma exacerbations, asthma-related hospitalizations/ED visits or oral corticosteroids use.

Data on asthma-related hospitalizations/ED visits outcomes were missing in 40 subjects in GALA II, 24 subjects in PACMAN, 27 subjects in PAGES, 43 subjects in SAGE, and 35 subjects in SLOVENIA; data on asthma-related oral OCS use were missing in 49 subjects in GALA II, 30 subjects in PAGES, 16 subjects in SAGE, and 34 subjects in SLOVENIA, data on asthma exacerbations were missing in 44 subjects in GALA II, 21 subjects in PACMAN, 30 subjects in PAGES, 48 subjects in SAGE, and 34 subjects in SLOVENIA. In followMAGICS, only data on asthma-related hospitalizations/ED visits were available.

Asthma exacerbations occurred in 2,494 patients (43.5%) and the proportion of asthma exacerbations ranged from 9.7% (PACMAN) to 86.2% (PASS) across the studies. The mean age (SD) of the patients ranged between 8.7 (2.3) years for PACMAN and 17.3 (3.0) years for followMAGICS, and in all studies, the majority of patients were male. The percentage of subjects treated with ICS plus LABA differed across the studies and ranged from 10.2% in GALA II to 50.3% in followMAGICS. In addition, all patients in SLOVENIA and SCSGES were treated with ICS monotherapy.

Table 2 shows the ADRB2 genotype and haplotype data. The risk allele (Arg) frequency for rs1042713 was highest in SCSGES, (0.55) followed by SAGE, (0.51). The risk allele (Arg) frequency for rs1072713 ranged between (0.34) for ESTATe and (0.41) for PACMAN across the European studies. The risk allele (Gln) frequency for rs1042714 was highest in SCSGES (0.93) followed by SAGE, (0.82). The risk allele (Gln) frequency for rs1042714 was similar across the European studies and ranged between (0.54) for PASS and (0.60) for ESTATe and SLOVENIA. Both SNPs were in HWE in all studies (in each cohort) and they showed a complete LD (D’ ~ 1) with r2 that ranged from 0.10 in SCSGES to 0.50 in PASS.

Table 2:

ADRB2 genotype and haplotype data

| Characteristics | BREATHE | ESTATe | Follow MAGICS | GALAII | PACMAN | PAGES | PASS | SAGE | SLOVENIA | SCSGES |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subjects with data on rs1042713. n. | 998 | 101 | 167 | 1,618 | 791 | 720 | 384 | 740 | 212 | 170 |

| Risk allele (Arg) frequency | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| rs1042713 genotype, no. (%) | ||||||||||

| Arg/Arg | 154 (15.4) | 14 (13.9) | 25 (15.0) | 306 (18.9) | 124 (15.7) | 101 (14.1) | 59 (15.4) | 198 (26.7) | 35 (16.5) | 46 (27.0) |

| Arg/Gly | 436 (43.7) | 40 (39.6) | 78 (46.7) | 819 (50.6) | 402 (50.8) | 330 (45.8) | 167 (43.5) | 355 (48.0) | 87 (41.0) | 96 (56.5) |

| Gly/Gly | 408 (40.9) | 47 (46.5) | 64 (38.3) | 493 (30.5) | 265 (33.5) | 289 (40.1) | 158 (41.1) | 187 (25.3) | 90 (42.5) | 28 (16.5) |

| Subjects with data on rs1042714. n. | 998 | 101 | 167 | 1,622 | 791 | 722 | 384 | 744 | 212 | 169 |

| Risk allele (Gln) frequency | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.78 | 0.63 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.82 | 0.60 | 0.93 |

| rs1042714 genotype, no. (%) | ||||||||||

| Gln/Gln | 307 (30.8) | 36 (35.6) | 57 (34.1) | 971 (59.9) | 313 (39.6) | 232 (32.1) | 115 (30.0) | 497 (66.8) | 81 (38.2) | 144 (85.2) |

| Gln/Glu | 495 (49.6) | 50 (49.5) | 79 (47.3) | 576 (35.5) | 376 (47.5) | 349 (48.4) | 184 (47.9) | 223 (30.0) | 91 (42.9) | 25 (14.8) |

| Glu/Glu | 196 (19.6) | 15 (14.9) | 31 (18.6) | 75 (4.6) | 102 (12.9) | 141 (19.5) | 85 (22.1) | 24 (3.2) | 40 (18.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Subjects with data on both SNPs. n. | 998 | 101 | 167 | 1,618 | 791 | 714 | 384 | 740 | 212 | 169 |

| Haplotype frequency | ||||||||||

| Arg16/Gln27 | 0.37 | 0.34 | 0.38 | 0.44 | 0.41 | 0.37 | 0.37 | 0.51 | 0.37 | 0.55 |

| Gly16/Gln27 | 0.18 | 0.27 | 0.20 | 0.34 | 0.22 | 0.19 | 0.17 | 0.31 | 0.23 | 0.37 |

| Gly16/Glu27 | 0.45 | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.40 | 0.08 |

| Linkage disequilibrium between rs1042713 and rs1042714 | ||||||||||

| r2 (D`) | 0.47 (~1) | 0.33 (1) | 0.43 (0.98) | 0.23 (1) | 0.40 (~1) | 0.46 (~1) | 0.50 (~1) | 0.23 (1) | 0.40 (1) | 0.10 (1) |

Three haplotypes were determined at positions 16 and 27, and haplotype frequencies were as follows: Arg16/Gln27 (ranged from 0.34 to 0.55), Gly16/Gln27 (ranged from 0.17 to 0.37), and Gly16/Glu27 (ranged from 0.08 to 0.46), (Table 2).

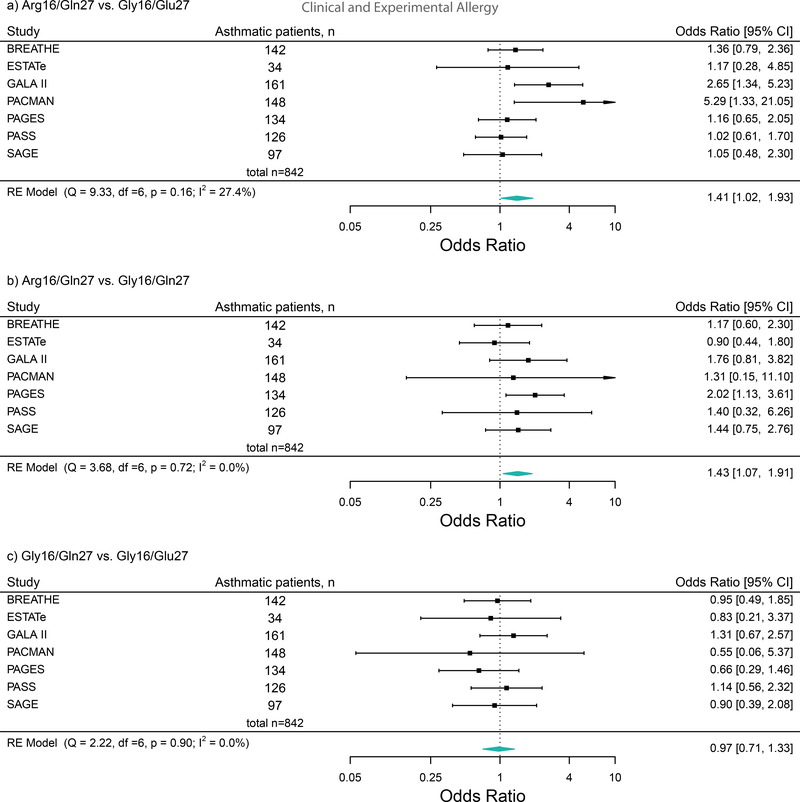

Risk of asthma exacerbations in children treated with ICS plus LABA

Data on the outcome, asthma exacerbations (asthma-related OCS use or hospitalizations/ED visits), haplotypes, and ICS plus LABA treatment were available in seven studies (n = 832, age = 3–21 years). The meta-analysis indicated that Arg16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Glu27 (OR: 1.40, 95% CI: 1.05−1.87, I2 = 0.00%, P = 0.022) and Arg16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Gln27 (OR: 1.43, 95% CI: 1.05−1.94, I2 = 0.00%, P = 0.023), were significantly associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations (Figure 1). However, Gly16/Gln27 vs. Gly16/Glu27 (OR: 0.99, 95% CI: 0.71−1.39, I2 = 0.00%, P = 0.946), was not associated with the risk of asthma exacerbations.

Figure 1:

Forest plots of the association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and the risk of asthma exacerbations (asthma-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits or oral corticosteroids use) in ICS plus LABA treatment group across studies These plots describe Odds Ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), adjusted for age and sex.

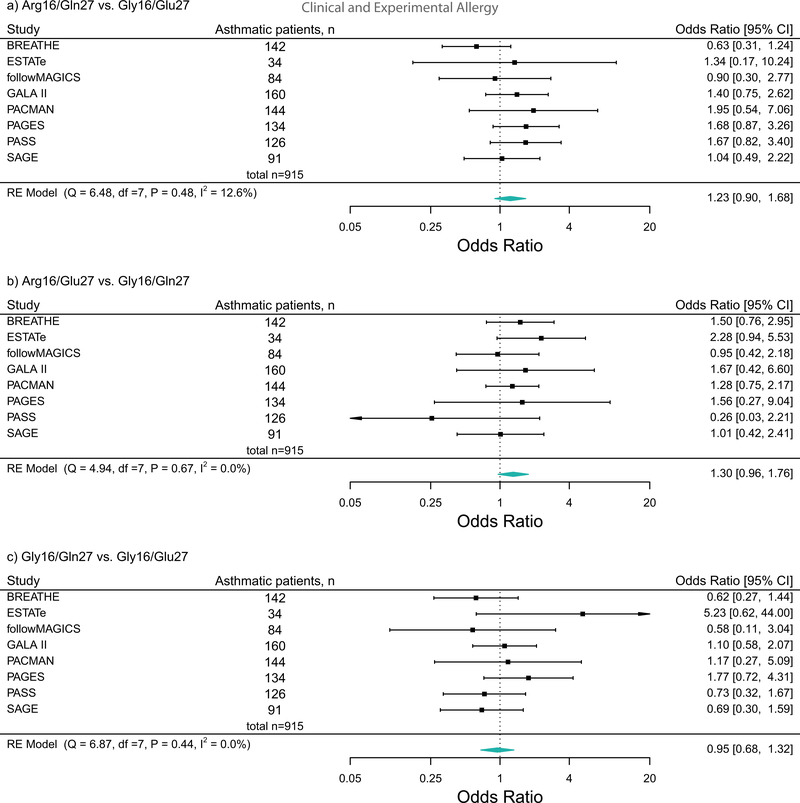

Sensitivity analyses

In patients treated with ICS plus LABA, we repeated the haplotype analysis separately for asthma-related OCS use and for asthma-related hospitalizations/ED visits. We observed the similar trends as the main analysis (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Furthermore, no association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and the risk of asthma exacerbations was observed in any of the other treatment groups (Table 3).

Figure 2:

Forest plots of the association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and the risk of asthma-related oral corticosteroids use in ICS plus LABA treatment group across studies. These plots describe Odds Ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), adjusted for age and sex.

Figure 3:

Forest plots of the association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and the risk of asthma-related hospitalizations/emergency department visits in ICS plus LABA treatment group across studies. These plots describe Odds Ratios (ORs) and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs), adjusted for age and sex.

Table 3:

Risk of asthma exacerbations* across the other treatment groups.

| Haplotypes | BREATHE | ESTATe | followMAGICS | GALA II | PACMAN | PAGES | PASS | SAGE | SLOVENIA | SCSGES | Total Combined Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) for asthma exacerbations in patients treated with as-required SABA | |||||||||||

| n = 173 | N/A | N/A | n = 557 | N/A | n = 51 | N/A | n = 192 | N/A | N/A | n = 973 | |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 1.28 (0.61, 2.70) |

N/A | N/A | 1.17 (0.84, 1.62) |

N/A | 0.54 (0.13, 2.31) |

N/A | 0.67 (0.36, 1.24) |

N/A | N/A | 1.00 (0.71, 1.40) I2 = 21.50% |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Gln27 | 0.92 (0.33, 2.60) |

N/A | N/A | 1.13 (0.80, 1.60) |

N/A | 2.10 (0.26, 17.03) |

N/A | 0.80 (0.42, 1.55) |

N/A | N/A | 1.05 (0.79, 1.41) I2 = 0.00% |

| Gly16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 1.40 (0.50, 3.97) |

N/A | N/A | 1.03 (0.73, 1.45) |

N/A | 0.26 (0.03, 2.09) |

N/A | 0.83 (0.43, 1.61) |

N/A | N/A | 0.99 (0.74, 1.32) I2 = 0.00% |

| OR (95% CI) for asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS monotherapy | |||||||||||

| n = 562 | n = 65 | N/A | n = 527 | n = 484 | n = 268 | n = 29 | n = 341 | n = 178 | n = 169 | n = 2,623 | |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 1.21 (0.88, 1.65) |

0.74 (0.31, 1.76) |

N/A | 1.47 (1.00, 2.16) |

0.74 (0.45, 1.21) |

1.21 (0.80, 1.82) |

N/A | 0.70 (0.45, 1.09) |

0.72 (0.44, 1.18) |

1.00 (0.38, 2.62) |

0.98 (0.78, 1.23) I2 = 46.37% |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Gln27 | 1.06 (0.72, 1.56) |

1.58 (0.58, 4.30) |

N/A | 1.22 (0.88, 1.70) |

0.96 (0.54, 1.71) |

0.99 (0.61, 1.60) |

N/A | 1.01 (0.99, 1.02) |

0.93 (0.50, 1.70) |

0.67 (0.39, 1.15) |

1.01 (0.99, 1.02) I2 = 0.00% |

| Gly16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 1.15 (0.78, 1.70) |

0.47 (0.16, 1.37) |

N/A | 1.74 (1.15, 2.62) |

0.77 (0.43, 1.36) |

1.25 (0.78, 2.00) |

0.67 (0.34, 4.97) |

0.70 (0.43, 1.14) |

0.78 (0.43, 1.42) |

1.49 (0.55, 4.04) |

1.01 (0.77, 1.33) I2 = 46.05% |

| OR (95% CI) for asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS+LTRA | |||||||||||

| n = 37 | N/A | N/A | n = 203 | N/A | n = 64 | N/A | n = 34 | N/A | N/A | n = 338 | |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 0.96 (0.29, 3.24) |

N/A | N/A | 1.33 (0.72, 2.45) |

N/A | 1.01 (0.44, 2.27) |

N/A | 1.11 (0.19, 6.55) |

N/A | N/A | 1.16 (0.75, 1.80) I2 = 0.00% |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Gln27 | 1.14 (0.32, 4.07) |

N/A | N/A | 0.96 (0.60, 1.52) |

N/A | 0.43 (0.14, 1.25) |

N/A | 1.50 (0.41, 5.54) |

N/A | N/A | 0.91 (0.62, 1.34) I2 = 0.00% |

| Gly16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 0.84 (0.25, 2.90) |

N/A | N/A | 1.39 (0.75, 2.60) |

N/A | 2.36 (0.72, 7.78) |

N/A | 0.74 (0.11, 5.04) |

N/A | N/A | 1.35 (0.83, 2.20) I2 = 0.00% |

| OR (95% CI) for asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS+LABA+LTRA | |||||||||||

| n = 84 | N/A | N/A | n = 129 | n = 43 | n = 168 | n = 229 | n = 33 | N/A | N/A | n = 686 | |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 0.81 (0.42, 1.58) |

N/A | N/A | 0.96 (0.38, 2.44) |

0.41 (0.08, 2.14) |

0.97 (0.56, 1.68) |

1.58 (0.89, 2.83) |

0.65 (0.10, 4.31) |

N/A | N/A | 1.03 (0.75, 1.41) I2 = 2.57% |

| Arg16Gln27 vs. Gly16Gln27 | 1.53 (0.63, 3.72) |

N/A | N/A | 0.84 (0.40, 1.79) |

0.27 (0.04, 1.63) |

1.82 (0.93, 3.57) |

1.40 (0.65, 3.01) |

0.26 (0.02, 3.31) |

N/A | N/A | 1.22 (0.83, 1.79) I2 = 5.91% |

| Gly16Gln27 vs. Gly16Glu27 | 0.53 (0.21, 1.35) |

N/A | N/A | 1.13 (0.45, 2.87) |

1.52 (0.36, 6.47) |

0.53 (0.28, 1.00) |

1.13 (0.56, 2.29) |

2.48 (0.18, 34.37) |

N/A | N/A | 0.83 (0.54, 1.26) I2 = 17.70% |

Asthma exacerbations, asthma–related hospitalizations/emergency department visit or oral corticosteroids use. SABA, short-acting β2-agonists; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; LABA, long-acting β2-agonists; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonists. Odds Ratio (ORs) and corresponding 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were reported, adjusted for age and sex. N/A, Not applicable.

Functional annotation and eQTL analysis of the ADRB2 variants

Functional annotation, using Haploreg v4.1 data,31 showed that rs1042713 and rs1042714 had several proxy variants in strong LD (D` = 1 and r2 > 0.8), but none of them was a non-synonymous proxy (Table S1 and Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Furthermore, the cis-eQTL data from Genenetwork showed that not only the Arg allele of rs1042713 but also the Gln allele of rs1042714 was associated with reduced levels expression of ADRB2 in whole blood.32 Therefore, these data indicated that the variants alters the ADRB2 expression and function.

DISCUSSION

In this large multi-ethnic meta-analysis, we observed that the Arg16/Gln27 haplotype vs. the Gly16/Glu27 haplotype and the Arg16/Gln27 haplotype vs. the Gly16/Gln27 haplotype were associated with an increased risk of asthma exacerbations in children and young adults treated with ICS plus LABA. Considering that no statistically significant association was observed between the Gly16/Gln27 haplotype vs. the Gly16/Glu27 haplotype and the risk of asthma exacerbations, we could conclude that the combined effect of two polymorphisms at codons 16 and 27 on asthma exacerbations is presumably mainly driven by the Arg16. Furthermore, we did not find an increased risk for exacerbations in asthmatic children carrying the Arg16 haplotype in any of the other treatment categories. The lack of association in the treatment category containing ICS, LABA, and LTRA might be due to both the bronchodilation and anti-inflammation effects of LTRA37, as well as to the relatively small sample size.

There was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0.00%) in the main analysis between studies (Figure 1); however, the ORs were slightly different across the studies. The proportion of asthma exacerbations largely varied between the studies, lowest in PACMAN (recruiting from primary care and community pharmacies) and highest in PASS (recruiting from tertiary care), which might be due to the recruitment of patients from different health care settings (i.e., primary, secondary, and tertiary care, or community pharmacies) and thus reflect differences in asthma severity. Also, asthma treatment policy that affects doctors’ underlying tendencies to prescribe OCS varies in different countries, which in turn could influence the proportion of asthma exacerbations.38 In all studies, both SNPs were in complete linkage disequilibrium (D’~1) with each other; as a result, we determined three haplotypes of the four possible haplotypes (Arg16/Glu27 was not reported), which is in line with previous findings.39,40 Furthermore, considering ethnicity variability in our study populations, we observed different minor allele frequencies in each SNP that resulted in considerable variations in r2, which indicates the correlation coefficient of the allele frequencies. We also observed the highest risk allele frequencies (the Arg allele at rs1042713 and the Gln allele at rs1042714) in SCSGES, SAGE, and GALA II, whereas the Gly16/Glu 27 haplotype frequency was substantially the lowest in these three studies, consistent with previous works.41–46 A recent systematic review2 reported studies that investigated the association between the ADRB2 variants and response to LABA in children and adults with asthma. In children, most studies reported an increased risk of asthma exacerbations in carriers of Arg 16, whereas no association was found in adults.4,7,8,10,47 So far, only two studies investigated the effect of rs1042714 on asthma exacerbations in children treated with ICS plus LABA and did not report significant associations.4,9 Similarly, in adults, no association between rs1042714 and response to LABA concerning asthma exacerbations has been shown in a post hoc analysis from a randomized clinical trial.8

A few studies examined the association between these ADRB2 haplotypes in subjects with asthma. However, they mainly focused on changes in forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1),42 forced vital capacity (FVC), FEV1/FVC ratio,43 and overall mean changes in morning peak flow as primary outcomes.48 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first large meta-analysis investigating the association between the ADRB2 haplotypes and the risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA to this date. We know from the literature that Arg16 at rs1042713 is associated with an increased risk for asthma exacerbations; however, this association has not yet been investigated in the Arg haplotype carriers.4,5,10

The exact mechanism by which ADRB2 polymorphisms confer risk for asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA is still unknown. The mechanism(s) underlying the association between the Arg16 allele and an increased risk of exacerbations in asthmatic patients treated with ICS plus LABA might involve an enhanced agonist-induced downregulation and uncoupling of airway β2-receptor, resulting in subsensitivity of bronchoprotective response.49 There is some evidence from the literature that ADRB2 haplotypes regulate receptor transcript and protein expression.42 Previous in-vitro findings indicated that the expression of the Arg16/Gln27 haplotype was significantly lower than the Gly16/Glu27 haplotype.42 The latter results42 are in line with eQTL data,32 demonstrating decreased expression levels of ADRB2 in the carriers of Arg16 and Gln27. Another possible explanation, based on the dynamic baseline receptor model proposed by Liggett,50 could be that the Arg16 genotype would be slightly more resistant than the Gly16 genotype to endogenous downregulation and desensitization. Thus the Arg 16 genotype would remain more susceptible to further subsensitivity to the chronic use of exogenous agonists.50 Hence, the observed weakened response to LABA in carriers of the Arg16/Gln27 haplotype is plausible.

As for all observational research, our study has strengths and limitations. The current study is to be the largest meta-analysis investigating the combined effect of the ADRB2 variants in asthmatic patients treated with ICS plus LABA. Also, we used quality-controlled genotyping data, physician diagnosed-asthma, and relevant clinical outcomes (asthma exacerbations). As the first limitation, we did not determine haplotype frequency using gene-counting estimates based on phase-known data. Instead, we obtained haplotype frequency estimates using the expectation-maximization (E-M) algorithm that previous studies have demonstrated the usefulness of this approach (E-M method),51 and the validity of the statistical technique of this method.52 Second, although the ADRB2 rare variants could affect treatment response to LABA therapy,53 our study was not powered to conduct rare variant analysis. Third, as we lacked information on treatment adherence and dosing in some of the PiCA cohorts, we could not adjust for these factors in our analyses. Fourth, as gene expression and eQTL are tissue-specific, ideally, they should be examined in the lung tissue of patients with asthma, treated with ICS plus LABA. Finally, in our meta-analysis, we observed a significant OR (1.40), 95% CI (1.05−1.87) with a P = 0.022, applying a multiple testing correction (P < 0.025) to define statistically significant results. We also calculated a prediction interval (PI); the PI in a random-effects model contains a highly probable effect estimate (OR) for a future observation if a new setting is similar to those included in the meta-analysis.54,55 In this case, the 95% PI is (0.96–2.04), and thus indeed broader than the 95% CI.

In conclusion, we found that the Arg16 haplotype in ADRB2, presumably mainly driven by the Arg16, increased the risk of asthma exacerbations among users of ICS and LABA. The clinical benefits and risks associated with the use of LABA in patients with the Arg16 haplotype and genotypes need to be evaluated in randomized clinical trials such as the ongoing precision medicine clinical trial (the PUFFIN trial) investigating ADRB2 genotype-guided (the Arg16 genotype) treatment in children with asthma.56

Supplementary Material

KEY MESSAGE:

Response to treatment with inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting β2-agonists (LABA) varies inter-individually in asthmatic patients.

The ADRB2 Arg16 haplotype increased the risk of asthma exacerbations in patients treated with ICS plus LABA.

This finding could be beneficial in ADRB2 genotype-guided treatment in asthmatic patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge the dedication, commitment, and contribution of the patients, families, recruiters, health care providers, and pharmacists participating in all the studies involved in the PiCA consortium. In particular, the authors thank Sandra Salazar for her support as the GALA II / SAGE study coordinator.

Individual cohorts were funded as follows: BREATHE was funded by Scottish Enterprises Tayside, the Gannochy Trust, and the Perth and Kinross Council, and Brighton and Sussex Medical School. ESTATe was supported by a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw; priority for medicines for children, Grant/Award Number: 113201006). PAGES was funded by The Chief Scientist Office (reference number: CZH/4/418). GALAII was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01HL117004 and X01HL134589; study enrolment supported by the Sandler Family Foundation, the American Asthma Foundation, the RWJF Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, Harry Wm. and Diana V. Hind Distinguished Professor in Pharmaceutical Sciences II and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences grant R01ES015794. SAGE was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institute of Health (NIH) grants R01HL117004 and X01HL134589; study enrolment supported by the Sandler Family Foundation, the American Asthma Foundation, the RWJF Amos Medical Faculty Development Program, Harry Wm. and Diana V. Hind Distinguished Professor in Pharmaceutical Sciences II. This study was also funded by the award (AC15/00015) funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through Strategic Action for Health Research (AES) and European Community (EC) within the Active and Assisted Living (AAL) Programme framework and the SysPharmPedia grant from the ERACoSysMed 1st Joint Transnational Call from the European Union under the Horizon 2020, and Maria Pino-Yanes was supported by the Ramón y Cajal Program (RYC-2015–17205) by the Spanish Ministry of Economy, Industry, and Competitiveness. Natalia Hernandez-Pacheco was supported by a fellowship (FI16/00136) from ISCIII and co-funded by the European Social Funds from the European Union (ESF) “ESF invests in your future. PACMAN was supported by an unrestricted grant from GSK (part of a strategic alliance between GSK and Utrecht Institute for Pharmaceutical Sciences (UIPS). PASS was funded by the UK Department of Health through the NHS Chair of Pharmacogenomics and carried out at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Alder Hey Clinical Research Facility. In the SLOVENIA study, the authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research Agency (research core funding No. P3–0067) and the SysPharmPedia grant, co-financed by the Ministry of Education, Science and Sport of the Republic of Slovenia (contract number C3330–16-500106). Dr. CHEW Fook Tim (Singapore) received grants from the Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund, Singapore Immunology Network, National Medical Research Council (NMRC) (Singapore), and the Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) (Singapore); Grant Numbers: N-154–000-038–001; R-154–000-191–112; R-154–000-404–112; R-154–000-553–112; R-154–000-565–112; R-154–000-630–112; R-154–000-A08–592; R-154–000-A27–597; R-154–000-A91–592; R-154–000-A95–592; R154–000-B99–114; BMRC/01/1/21/18/077; BMRC/04/1/21/19/315; SIgN-06–006; SIgN-08–020; NMRC/1150/2008; H17/01/a0/008; and APG2013/108. FollwMAGICS was founded by the German charity Atemwegsliga and the German Ministry of Science and Education, grant Sysinflame (grant number 01ZX1306E).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Maitland-van der Zee reports personal fees for participating in advisory boards from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, unrestricted research grants from Boehringer Ingelheim, and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK). Dr. Vijverberg has received a grant from GSK during the conduct of the study. Dr. Pino-Yanes reports grants and non-financial support from the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII); during the conduct of the study. Dr. CHEW reports grants from the Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund, Singapore Immunology Network, National Medical Research Council (NMRC) (Singapore), and the Agency for Science Technology and Research (A*STAR) (Singapore), during the conduct of the study; consultancy fees from Sime Darby Technology Centre; First Resources Ltd; Genting Plantation, and Olam International, outside the submitted work. Dr. Janssens reports grants from Vectura and personal fees from Vertex, outside the submitted work. Dr. Katia Verhamme reports grants from ZonMw, during the conduct of the study; and KV works for a research group who receives/received unconditional research grants from Yamanouchi, Pfizer/Boehringer Ingelheim, Novartis, and GSK; outside the submitted work. Dr. Engelkes reports grants from ZonMw, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Kabesch reports that his institution received a grant from European Union, German Ministry of Education and Research, German Research Foundation, and received personal fees from consultancy and for participating in advisory boards from Bionorica, Sanofi, Novartis, Bencard, European respiratory society (ERS), European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (EAACI), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Novartis, Glaxo, Nutricia, Hipp; Allergopharma, and Teva; outside the submitted work. Hernandez-Pacheco reports grants from Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) during the conduct of the study. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest. The rest authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data Availability Statement,

Not required.

REFERENCES

- 1.The Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention,(GINA) 2020. Available from: http://www.ginasthma.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Slob EMA, Vijverberg SJH, Palmer CNA, et al. Pharmacogenetics of inhaled long-acting beta2-agonists in asthma: A systematic review. Pediatric allergy and immunology : official publication of the European Society of Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2018;29:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson M Molecular mechanisms of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006;117:18–24; quiz 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palmer CN, Lipworth BJ, Lee S, et al. Arginine-16 beta2 adrenoceptor genotype predisposes to exacerbations in young asthmatics taking regular salmeterol. Thorax. 2006;61:940–944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuurhout MJ, Vijverberg SJ, Raaijmakers JA, et al. Arg16 ADRB2 genotype increases the risk of asthma exacerbation in children with a reported use of long-acting beta2-agonists: results of the PACMAN cohort. Pharmacogenomics. 2013;14:1965–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Paiva AC, Marson FA, Ribeiro JD, et al. Asthma: Gln27Glu and Arg16Gly polymorphisms of the beta2-adrenergic receptor gene as risk factors. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2014;10:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor DR, Drazen JM, Herbison GP, et al. Asthma exacerbations during long term beta agonist use: influence of beta(2) adrenoceptor polymorphism. Thorax. 2000;55:762–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bleecker ER, Postma DS, Lawrance RM, et al. Effect of ADRB2 polymorphisms on response to longacting beta2-agonist therapy: a pharmacogenetic analysis of two randomised studies. Lancet (London, England). 2007;370:2118–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giubergia V, Gravina L, Castanos C, et al. Influence of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms on asthma exacerbation in children with severe asthma regularly receiving salmeterol. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2013;110:156–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner S, Francis B, Vijverberg S, et al. Childhood asthma exacerbations and the Arg16 beta2-receptor polymorphism: A meta-analysis stratified by treatment. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;138:107–113.e105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wechsler ME, Kunselman SJ, Chinchilli VM, et al. Effect of beta2-adrenergic receptor polymorphism on response to longacting beta2 agonist in asthma (LARGE trial): a genotype-stratified, randomised, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Lancet (London, England). 2009;374:1754–1764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farzan N, Vijverberg SJ, Andiappan AK, et al. Rationale and design of the multiethnic Pharmacogenomics in Childhood Asthma consortium. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18:931–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martin AC, Zhang G, Rueter K, et al. Beta2-adrenoceptor polymorphisms predict response to beta2-agonists in children with acute asthma. The Journal of asthma : official journal of the Association for the Care of Asthma. 2008;45:383–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tavendale R, Macgregor DF, Mukhopadhyay S, et al. A polymorphism controlling ORMDL3 expression is associated with asthma that is poorly controlled by current medications. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2008;121:860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffatt MF, Kabesch M, Liang L, et al. Genetic variants regulating ORMDL3 expression contribute to the risk of childhood asthma. Nature. 2007;448:470–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neophytou AM, White MJ, Oh SS, et al. Air Pollution and Lung Function in Minority Youth with Asthma in the GALA II (Genes-Environments and Admixture in Latino Americans) and SAGE II (Study of African Americans, Asthma, Genes, and Environments) Studies. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2016;193:1271–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishimura KK, Galanter JM, Roth LA, et al. Early-life air pollution and asthma risk in minority children. The GALA II and SAGE II studies. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;188:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster ES, Raaijmakers JA, Koppelman GH, et al. Pharmacogenetics of anti-inflammatory treatment in children with asthma: rationale and design of the PACMAN cohort. Pharmacogenomics. 2009;10:1351–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koster ES, Blom L, Philbert D, et al. The Utrecht Pharmacy Practice network for Education and Research: a network of community and hospital pharmacies in the Netherlands. International journal of clinical pharmacy. 2014;36:669–674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turner SW, Ayres JG, Macfarlane TV, et al. A methodology to establish a database to study gene environment interactions for childhood asthma. BMC medical research methodology. 2010;10:107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawcutt DB, Jorgensen AL, Wallin N, et al. Adrenal responses to a low-dose short synacthen test in children with asthma. Clinical endocrinology. 2015;82:648–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hawcutt DB, Francis B, Carr DF, et al. Susceptibility to corticosteroid-induced adrenal suppression: a genome-wide association study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2018;6:442–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andiappan AK, Sio YY, Lee B, et al. Functional variants of 17q12–21 are associated with allergic asthma but not allergic rhinitis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2016;137:758–766 e753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andiappan AK, Anantharaman R, Nilkanth PP, et al. Evaluating the transferability of Hapmap SNPs to a Singapore Chinese population. BMC genetics. 2010;11:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berce V, Kozmus CE, Potocnik U. Association among ORMDL3 gene expression, 17q21 polymorphism and response to treatment with inhaled corticosteroids in children with asthma. The pharmacogenomics journal. 2013;13:523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2009;180:59–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Basu K, Palmer CN, Tavendale R, et al. Adrenergic beta(2)-receptor genotype predisposes to exacerbations in steroid-treated asthmatic patients taking frequent albuterol or salmeterol. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2009;124:1188–1194.e1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pino-Yanes M, Thakur N, Gignoux CR, et al. Genetic ancestry influences asthma susceptibility and lung function among Latinos. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135:228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.White MJ, Risse-Adams O, Goddard P, et al. Novel genetic risk factors for asthma in African American children: Precision Medicine and the SAGE II Study. Immunogenetics. 2016;68:391–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez-Pacheco N, Farzan N, Francis B, et al. Genome-wide association study of inhaled corticosteroid response in admixed children with asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.HaploReg v4.1, Broad Institute, 2015. Available online: www.broadinstitute.org/mammals/haploreg/haploreg.php;. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westra HJ, Peters MJ, Esko T, et al. Systematic identification of trans eQTLs as putative drivers of known disease associations. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1238–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rodriguez S, Gaunt TR, Day IN. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing of biological ascertainment for Mendelian randomization studies. American journal of epidemiology. 2009;169:505–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinnwell J, Schaid D. Statistical Analysis of Haplotypes with Traits and Covariates when Linkage Phase is Ambiguous. R package version 1.7.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=haplo.stats 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viechtbauer W Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package Journal of Statistical Journal of Statistical Software; 2010; 36; Available from: http://www.ginasthmaorg. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dempsey OJ. Leukotriene receptor antagonist therapy. Postgraduate medical journal. 2000;76:767–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wahlström R, Hummers-Pradier E, Lundborg CS, et al. Variations in asthma treatment in five European countries--judgement analysis of case simulations. Family practice. 2002;19:452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Slatkin M Linkage disequilibrium--understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2008;9:477–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karimi L, Lahousse L, Ghanbari M, et al. beta2-Adrenergic Receptor (ADRB2) Gene Polymorphisms and Risk of COPD Exacerbations: The Rotterdam Study. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019;8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hizawa N Beta-2 adrenergic receptor genetic polymorphisms and asthma. Journal of clinical pharmacy and therapeutics. 2009;34:631–643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Drysdale CM, McGraw DW, Stack CB, et al. Complex promoter and coding region beta 2-adrenergic receptor haplotypes alter receptor expression and predict in vivo responsiveness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10483–10488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hawkins GA, Tantisira K, Meyers DA, et al. Sequence, haplotype, and association analysis of ADRbeta2 in a multiethnic asthma case-control study. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2006;174:1101–1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ortega VE, Meyers DA. Pharmacogenetics: implications of race and ethnicity on defining genetic profiles for personalized medicine. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;133:16–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao N, Liu X, Wang Y, et al. Association of inflammatory gene polymorphisms with ischemic stroke in a Chinese Han population. Journal of neuroinflammation. 2012;9:162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ramphul K, Lv J, Hua L, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms predisposing to asthma in children of Mauritian Indian and Chinese Han ethnicity. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 2014;47:394–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wechsler ME, Yawn BP, Fuhlbrigge AL, et al. Anticholinergic vs Long-Acting beta-Agonist in Combination With Inhaled Corticosteroids in Black Adults With Asthma: The BELT Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama. 2015;314:1720–1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bleecker ER, Yancey SW, Baitinger LA, et al. Salmeterol response is not affected by beta2-adrenergic receptor genotype in subjects with persistent asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2006;118:809–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipworth B beta-Adrenoceptor genotype and bronchoprotective subsensitivity with long-acting beta-agonists in asthma. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2013;188:1386–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liggett SB. The pharmacogenetics of beta2-adrenergic receptors: relevance to asthma. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2000;105:S487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tishkoff SA, Pakstis AJ, Ruano G, et al. The accuracy of statistical methods for estimation of haplotype frequencies: an example from the CD4 locus. American journal of human genetics. 2000;67:518–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zaykin DV, Westfall PH, Young SS, et al. Testing association of statistically inferred haplotypes with discrete and continuous traits in samples of unrelated individuals. Human heredity. 2002;53:79–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ortega VE, Hawkins GA, Moore WC, et al. Effect of rare variants in ADRB2 on risk of severe exacerbations and symptom control during longacting beta agonist treatment in a multiethnic asthma population: a genetic study. The Lancet. Respiratory medicine. 2014;2:204–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Rovers MM, et al. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2016;6:e010247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spineli LM, Pandis N. Prediction interval in random-effects meta-analysis. American journal of orthodontics and dentofacial orthopedics : official publication of the American Association of Orthodontists, its constituent societies, and the American Board of Orthodontics. 2020;157:586–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vijverberg SJ, Pijnenburg MW, Hovels AM, et al. The need for precision medicine clinical trials in childhood asthma: rationale and design of the PUFFIN trial. Pharmacogenomics. 2017;18:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not required.