Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

Parents of children with cancer perceive deficits in quality of prognostic communication. How oncologists disclose information about disease progression and incurability and how prognostic communication impacts parental understanding of prognosis are poorly understood. In this study, we aimed to (1) characterize communication strategies used by pediatric oncologists to share prognostic information across a child’s advancing illness course and (2) explore relationships between different communication approaches and concordance of oncologist-parent prognostic understanding.

METHODS:

In this prospective, longitudinal, mixed-methods study, serial disease reevaluation conversations were audio recorded across an advancing illness course for children with cancer and their families. Surveys and interviews also were conducted with oncologists and caregivers at specific time points targeting disease progression.

RESULTS:

Seventeen children experienced advancing illness on study, resulting in 141 recordings (40 hours). Fewer than 4% of recorded dialogue constituted prognostic communication, with most codes (77%) occurring during discussions about frank disease progression. Most recordings at study entry contained little or no prognosis communication dialogue, and oncologists rated curability lower than parents across all dyads. Parent-oncologist discordance typically was preceded by conversations without incurability statements; ultimately, concordance was achieved in most cases after the oncologist made direct statements about incurability. Content analysis revealed 3 distinct patterns (absent, deferred, and seed planting) describing the provision of prognostic communication across an advancing pediatric cancer course.

CONCLUSIONS:

When oncologists provided direct statements about incurability, prognostic understanding appeared to improve. Further research is needed to determine optimal timing for prognostic disclosure in alignment with patient and family preferences.

Children with cancer and their families report a desire for direct, empathic, and frequent prognostic communication,1–4 yet barriers to high-quality communication persist. Parents of children with cancer perceive deficits in the quality of information that they receive about their child’s prognosis,5 and retrospective data suggest that pediatric oncologists may avoid or censor distressing prognostic information in an effort to avoid fracturing a therapeutic alliance or abrogating parental hope.6,7 Counter to these perceptions, many parents of children with cancer report a preference for engaging in detailed, longitudinal prognostic dialogue across the illness arc,4 and honest prognostic disclosure appears to engender peace of mind, trust in the physician, and hopefulness for patients and families even in the context of poor prognoses.2,8–11

Shared prognostic understanding also has the potential to improve clinical outcomes for patients and families. In the absence of clear prognostic communication, parents may overestimate their child’s likelihood of cure in ways that adversely impact decision-making.12–14 Conversely, concordance of prognostic awareness between oncologists and parents is associated with increased provision of interventions to alleviate suffering and enhanced palliative care integration.15,16

Historically, literature on prognostic communication in pediatric oncology has been largely cross-sectional, retrospective, and/or reliant on survey methodology.17 Although prospective investigation of recorded medical dialogue is increasingly recognized as the gold standard for prognostic communication research, few published studies have been used to analyze prognostic communication from recorded conversations discussing disease progression in children with cancer,18,19 and no previous studies have been used to describe prognostic disclosure occurring in real time across serial time points across the illness journey to end of life.17

The Understanding Communication in Healthcare to Achieve Trust (U-CHAT) trial was designed to better understand the evolution and impact of prognostic communication across the advancing pediatric cancer trajectory. The U-CHAT trial is a prospective, longitudinal investigation of communication among pediatric oncologists, children and adolescents with high-risk cancer, and their families, in which serial disease reevaluation conversations are audio recorded across the illness course to the time of death. We aimed to better understand the specific communication strategies used by pediatric oncologists to share prognostic information as well as the impact of varying communication approaches on parental understanding of prognosis in the setting of advancing pediatric cancer.

METHODS

The U-CHAT trial was developed by an interdisciplinary team of pediatric oncology and hospice and palliative medicine experts in collaboration with the Bereaved Parent Steering Council; the protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (U-CHAT [Pro00006473]; approval date: July, 12, 2016).

Data Collection

In this article, we focus on data collected for patient-parent dyads with advancing disease while on study. Study eligibility criteria and processes related to recruitment and informed consent are summarized in Table 1. All conversations after a disease reevaluation time point were audio recorded across the illness course. The patient’s oncologist and caregiver completed matched surveys at two time points: after the first discussion after enrollment and after the subsequent disease progression discussion. Both oncologist and caregiver completed matched semistructured interviews after disease progression discussions. In surveys and interviews, we asked the following question: How likely do you think it is that your patient/child will be cured of cancer? Demographic information and data related to the illness course were extracted from the electronic medical record by using a standardized tool.

TABLE 1.

Eligibility Criteria, Recruitment, and Informed Consent Processes

| Protocol Domain | Study Information |

|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria | Primary oncologists providing medical care to patients with a solid tumor at the institution were eligible for enrollment on study. |

| Nonprimary oncologist health care professionals (eg, fellows, students, nurses, psychosocial providers) who attended a recorded disease reevaluation conversation for an enrolled study patient were also eligible for enrollment (with participation limited to attendance in the recording). | |

| Patients aged 0–30 y who had a solid tumor diagnosis with survival of ≤50% estimated by their primary oncologist and were projected to have ≥2 future time points of disease reevaluations were eligible for enrollment. | |

| Parents or legal guardians of eligible patients who were aged ≥18 y, had English-language proficiency, and planned to accompany the patient to medical visits were eligible for enrollment. One caregiver per patient was eligible for enrollment; if >1 caregiver was present, they self-selected the caregiver who preferred to participate. | |

| Family or friends of an enrolled patient-parent dyad who attended a recorded disease reevaluation conversation were also eligible for enrollment (with participation limited to attendance in the recording). | |

| Recruitment and informed consent | Eligible primary oncologists were introduced to the study by the PI who presented the study objectives and design at a Solid Tumor Division faculty meeting and addressed questions with the group. The study was presented as an investigation of communication between clinicians, patients with high-risk cancer, and their families across time. The PI individually sent e-mails to eligible oncologists to determine interest in participating; once interest was expressed, the PI met one-on-one with oncologists to describe the study at length and complete the informed consent process using verbal consent documents approved by the IRB. No oncologists were required to participate. All were approached and agreed to participate after informed consent. No oncologists declined participation. |

| Eligible nonprimary oncologist health care professionals were introduced to the study by the PI or research team member during clinic or office time preceding a scheduled recording. The study was described and informed consent obtained by using verbal consent documents approved by the IRB. All clinical staff who planned to attend the recorded discussion needed to agree independently to participate in the study for the discussion to be recorded. | |

| Eligible patient-parent dyads were identified by the research team through systematic review of outpatient clinic schedules and institutional trial lists. An algorithm was used to identify patients with any of the following diagnoses: (1) high-risk neuroblastoma, (2) any sarcoma, (3) any carcinoma, (4) desmoplastic small round cell tumor, (5) incompletely resected or metastatic retinoblastoma, (6) incompletely resected or metastatic Wilms tumor, or (7) incompletely resected or metastatic melanoma. The PI, who has dual training in pediatric oncology and hospice and palliative medicine, reviewed all identified patients to determine those with overall survival reasonably estimated at ≤50%. A member of the research team then asked the patient’s primary oncologist to answer the following standardized question: “In your clinical judgement, would you estimate [patient name]’s overall survival at 50% or less?” For dyads who met eligibility criteria, permission was requested from the primary oncologist to approach the patient and parent. With approval granted, patient-parent dyads were approached by a member of the research team during a clinic visit unrelated to a disease reevaluation discussion time point to determine interest in participation. If the dyad was interested, the study was described in detail with ample opportunity provided to answer questions. Dyadic enrollment required agreement from both the patient and parent; any disagreement between the patient and parent eliminated the dyad from participation. Patients aged ≥12 y provided assent, and patients aged ≥18 y and parents provided consent through written documents approved by the IRB. | |

| Eligible family and/or friends were introduced to the study by the PI or research team member before recording the visit, and verbal consent was obtained by using documents approved by the IRB. All individuals who planned to attend the recorded discussion needed to agree independently to participate in the study for the discussion to be recorded. |

IRB, institutional review board; PI, principal investigator.

Codebook Development

A team of pediatric oncology and palliative medicine clinicians and researchers reviewed the literature related to prognostic communication in the fields of adult and pediatric oncology. In the absence of consensus guidelines specific to prognostic communication in pediatric oncology,20 previously established communication standards in adult oncology,21,22 recent patient-clinician communication consensus guidelines endorsed by the American Society of Clinical Oncology,23 and the Prognostic and Treatment Choices scale24 informed the development of the Pediatric Oncology Prognostic Communication codebook, in which facets of prognostic communication were systemized into 6 a priori codes to describe prognostic communication content (Supplemental Table 5). The term “curability,” as used in this study, represented the ability or potential to cure a disease, irrespective of favorable or poor prognosis. Curability language did not need to encompass the words “cure” or “prognosis”; any language transmitting information related to a patient’s chance for survival was included. Curability codes were classified as “likely” or “unlikely” and also as “cloudy” (indirect) or “clear” (direct). Qualitative research analysts (E.C.K., M.G., M.S., C.W., and S.V.) independently pilot tested the codebook across a series of medical dialogue recordings until consensus was reached to ensure consistency in code application. The research team met to reconcile variances and achieve consensus, modifying the codebook when indicated to improve dependability, confirmability, and credibility of independent codes.25

Code Application and Reconciliation

After codebook finalization, coding was conducted by independent analysts (M.G., M.S., C.W., S.V.) and the research team met weekly to review coding variances with third-party adjudication (E.C.K., J.N.B.) as needed to achieve consensus. Consistency in code segmentation was reviewed to ensure a standardized approach (M.S., C.W., E.C.K.).

Analyses

Coding and analyses were conducted by using MAXQDA, a mixed-methods data analysis software system.26 Code frequency, temporal duration, and distribution across discussion subtype were calculated and reported as descriptive statistics. Concordance between oncologist and parent perceptions of curability was determined by comparing curability item responses on matched surveys, supplemented by interview data. All oncologist interview transcripts contained language that mirrored the surveys and/or percentages to enable straightforward curability grouping. Several parent interview responses did not directly answer the targeted question; when this occurred, we deferred to the survey response corresponding to the same recorded conversation.

Degree of discordance was categorized dichotomously, with responses that matched or fell within 1 response category labeled as concordant and any greater difference in response labeled as discordant. An exception was made for the difference between unlikely and “somewhat likely,” which was considered discordant. Iterative review and serial memo writing of coded dialogue27 informed the development of inductive codes describing the communication approaches used by oncologists to navigate prognostic disclosure.

RESULTS

A total of 33 patient-parent dyads enrolled on study and were followed until death or 24 months from first disease progression while on study, whichever occurred first. Seventeen children experienced advancing illness while enrolled in the study, yielding 141 recordings of disease reevaluation conversations constituting ∼40 hours of recorded dialogue. Occasionally, multiple recordings were made for the same disease reevaluation if clinicians gave news at different times; if different recordings occurred on the same day, these were considered 1 discussion, resulting in 134 disease reevaluation discussions. One patient progressed rapidly, resulting in the capture of a single disease reevaluation discussion before death; all other patients had multiple disease reevaluation conversations recorded (range: 1–16; median 6; mean 7.8). Most patients (14 of 17) had disease reevaluation conversations recorded until death; 3 patients remained alive at 24 months from on-study disease progression.

All health care providers affiliated with patient-parent dyads agreed to participate in the study (80 clinicians attended recorded conversations, including 6 primary oncology attending physicians). Primary participant demographics are presented in Table 2. Study feasibility and acceptability metrics related to participant enrollment and capture of longitudinal data have been previously published28 and are summarized in Supplemental Tables 6 and 7.

TABLE 2.

Participating Patient, Parent, and Oncologist Demographics

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient (n = 17) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 11 (64.7) |

| Male | 6 (35.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 15 (88.2) |

| Black | 1 (5.9) |

| Mixed | 1 (5.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 17 (100) |

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| 0–2 | 2 (11.8) |

| 3–11 | 6 (35.3) |

| 12–18 | 7 (41.2) |

| 19+ | 2 (11.8) |

| Parent (n = 17) | |

| Sex/role | |

| Female/mother | 14 (82.4) |

| Male/father | 3 (17.6) |

| Pediatric oncologist (n = 6) | |

| Sex | |

| Female | 3 (50) |

| Male | 3 (50) |

| Race | |

| White | 6 (100) |

| Black | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 6 (100) |

| Years in clinical practice | |

| 1–4 | 2 (33) |

| 5–9 | 2 (33) |

| 10–19 | 0 |

| 20+ | 2 (33) |

Frequency of Prognosis Communication Across Serial Disease Reevaluation Discussions

Across all recordings, a total of 557 prognosis communication codes were applied, entailing 92 minutes of prognosis discussion (3.8% of all recorded conversation). Two-thirds (91 of 134) of recorded disease reevaluation discussions contained at least 1 prognostic communication code. Disease reevaluation discussions that centered on improving, stable, or equivocal scan findings constituted fewer than one-quarter of prognostic communication (127 codes across 43 recordings, 21 minutes), compared with disease reevaluation discussions after unequivocal findings of disease progression (430 codes across 48 recordings, 71 minutes). Nearly all recordings that lacked prognostic communication codes were classified by the oncologist as good, stable, or equivocal news (42 or 43); only 1 recording described by the oncologist as bad news lacked prognostic communication codes. The frequencies of coded segments and curability content and language subtypes across serial disease reevaluation discussions for patients with advancing disease are presented in Tables 3 and 4.

TABLE 3.

Frequency of Prognosis Communication Codes in Serial Medical

| Code | Recorded Dialogue in the Setting of Improving, Stable, or Equivocal Disease | Recorded Dialogue in the Setting of Unequivocal Disease Progression | Totals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Frequency (%) | Time, min | Frequency (%) | Time, min | Frequency (%) | Time, min | % Total (for min) | |

| Understanding prognosis | 9 (7.1) | 00:52.0 | 35 (8.1) | 5:12.6 | 44 (79) | 6:04.6 | 0.2 |

| Prognostic uncertainty | 66 (52.0) | 10:55.6 | 84 (19.5) | 13:58.8 | 150 (26.9) | 24:54.4 | 1.0 |

| Change for worse | 36 (26.3) | 5:52.3 | 183 (42.6) | 30:49.8 | 219 (39.3) | 36:42.1 | 1.5 |

| Best versus worst | 5 (3.9) | 1:12.0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 5 (0.9) | 1:12.0 | 0.04 |

| Survival time | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 13 (3.0) | 2:07.5 | 13 (2.3) | 2:07.5 | 0.08 |

| Curability | 11 (8.7) | 2:13.8 | 115 (26.7) | 18:36.1 | 126 (22.6) | 20:49.9 | 0.9 |

| Total | 127 (100) | 21:05.7 | 430 (100) | 70:44.8 | 557 (100) | 91:50.5 | 3.8 |

TABLE 4.

Subtypes of Curability Content and Language Style in Serial Medical Discussions Across Advancing Illness

| Code | Recorded Dialogue in the Setting of Improving, Stable, or Equivocal Disease | Recorded Dialogue in the Setting of Unequivocal Disease Progression | Totals | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||

| Frequency (%) | Time, min | Frequency (%) | Time, min | Frequency (%) | Time, min | % Curability Time (for min) | |

| Curability | 11 (100) | 2:13.8 | 115 (100) | 18:36.1 | 126 (100) | 20:49.9 | 100 |

| Odds of cure | |||||||

| Likely | 4 (36.4) | 1:06.9 | 3 (2.6) | 01:10.3 | 7 (5.6) | 02:17.2 | 9.5 |

| Unlikely | 5 (45.5) | 00:40.9 | 61 (53.0) | 09:19.4 | 66 (52.4) | 10:00.3 | 47.6 |

| Zero | 2 (18.2) | 00:26.0 | 49 (42.6) | 07:53.5 | 51 (40.5) | 08:19.5 | 38.1 |

| Clarity of statement | |||||||

| Clear | 5 (45.5) | 00:56.8 | 52 (45.2) | 07:46.2 | 57 (45.2) | 08:43.0 | 42.9 |

| Cloudy | 6 (54.5) | 1:17.0 | 63 (54.8) | 10:50.1 | 69 (54.8) | 12:07.1 | 57.1 |

In the context of improving, stable, or equivocal disease findings, more than half (52%) of prognostic communication codes represented statements of prognostic uncertainty. Proportionally fewer codes encompassed assessment of prognostic understanding (7.1%) or curability statements (8.7%). When curability statements occurred, 36.4% described cure as likely, 45.5% as unlikely, and 18.2% as not possible. More curability statements (54.5%) were coded as cloudy (ie, indirect or vague) versus clear (45.5%).

Comparatively, in the context of overt disease progression, the most frequent type of prognostic communication involved statements about the disease changing for the worse (42.6%). Prognostic uncertainty statements represented a smaller percentage of the dialogue (19.5%), and more discussion about curability occurred (26.7%). In the presence of disease progression, most curability statements described unlikely (45.2%) or 0 (42.6%) chance of cure; the percentage of statements endorsing likely chance of cure was low (2.6%). The percentages of cloudy (54.8%) versus clear (45.2%) curability statements remained nearly identical between cohorts.

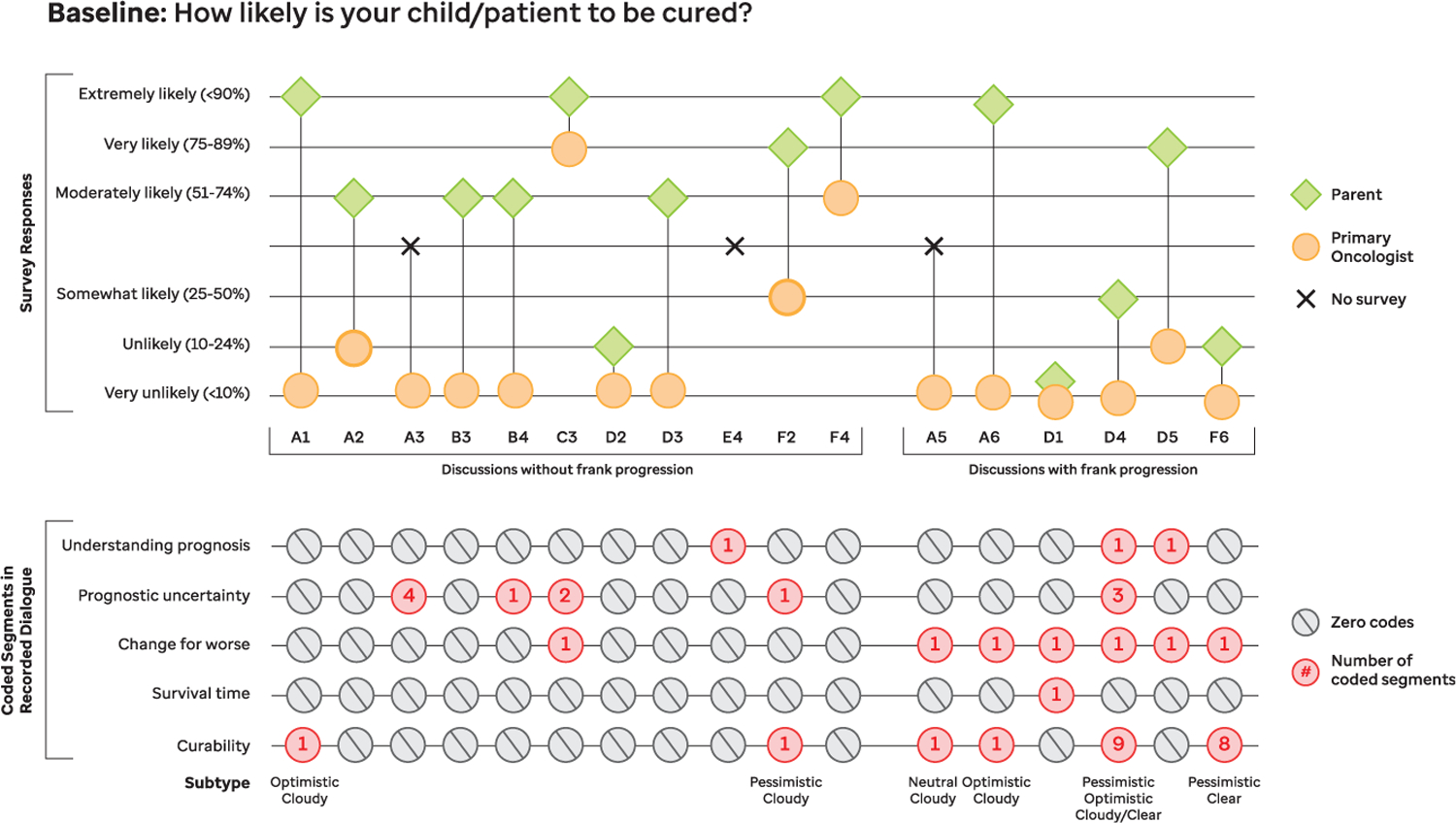

Prognostic Communication and Parent-Oncologist Concordance on Curability at Study Baseline

For most patients (13 of 17), the primary oncologist rated curability as very unlikely (,10%) or unlikely (10%–24%) after the initial recorded disease reevaluation conversation. For 3 patients, oncologists rated curability at 50% or higher, despite previous attestation of curability at 50% or lower during enrollment processes (Fig 1). For 1 patient, no baseline oncologist survey was completed. In contrast with oncologists, a majority of parents (11 of 14) rated their child’s curability at 50% or greater. Paired oncologist and parent baseline curability ratings were obtained for 14 patients, of which most (10) dyads were discordant. Most baseline recordings contained little to no prognosis communication dialogue, with 5 of 17 (29.4%) containing no prognostic statements.

FIGURE 1.

Baseline curability concordance and prognosis communication code frequencies. Concordance between parent and oncologist understanding of curability at study entry is shown in parallel with prognosis communication code frequencies from the corresponding baseline recorded conversation.

Relationship Between Prognostic Communication and Curability Concordance Across Time

Most patient-parent dyads (14 of 17) completed longitudinal survey and/or interview data, enabling assessment of evolution of prognostic communication and concordance in reported prognostic understanding across time. The majority of dyads (11 of 14) reached oncologist-parent concordance by the final recording. Of these 11 dyads, 4 maintained concordance across most of the illness course; all had at least 1 recording with direct statements about disease incurability.

In 6 of the remaining 7 dyads, all discordant time points were preceded by recordings with 0 statements about incurability; concordance was then achieved after a recorded discussion with statements about disease incurability. In 1 dyad, discordance persisted after a discussion that included a direct incurability statement.

Three dyads remained discordant through the final recording before death (n = 2) or coming off study (n = 1). In the 2 dyads with patients who died on study, no incurability statements were made across the illness course. Unprompted, both parents mentioned lack of discussion about incurability during their interviews. In the remaining dyad, direct statements about poor prognosis were made in 2 recorded discussions; however, the parent continued to report cure as likely.

Distinct Patterns of Prognostic Communication Evolution

Further content analysis revealed 3 dominant patterns describing the evolution of prognostic communication across an advancing illness course. Pattern visualization and representative case studies are presented in Figs 2 and 3, respectively. No one pattern was localized to a single oncologist; rather, all 3 patterns were seen in at least half of participating oncologists.

FIGURE 2.

Communication patterns describing the evolution of prognostic disclosure across advancing illness. Trends in prognostic communication approaches across time are visually depicted. Each pattern represents the synthesis of multiple case studies.

FIGURE 3.

Representative case studies. PET, positron emission tomography.

Absent: No Direct Discussion of Poor Prognosis or Incurability

The first pattern was found in 5 dyads, representing 3 different oncologists, in which no direct statements describing poor prognosis were identified across serial recordings before the patient’s death. Within these 5 dyads, 4 patients died on study and 1 remained alive with advancing disease after 24 months. In each case, most recorded dialogue centered on discussion of details related to disease progression or treatment without linking cancer advancement with incurability. Two oncologists offered statements that implied poor prognosis, such as, “It keeps coming back” and “We’re in a difficult spot”; however, no frank communication around prognosis was identified. In all 5 cases, the oncologist described likelihood of cure as either 0% (n = 4) or <10% (n = 1) during postrecording interviews. Concordance varied, with 2 parents not changing their perception of curability (stable discordance), 2 parents showing increased awareness of prognosis (improved concordance before death), and 1 parent declining to answer postrecording questions related to prognosis.

Deferred: Discussion of Poor Prognosis or Incurability Reserved for the Penultimate or Final Recording

The second pattern occurred in 6 dyads, representing 3 oncologists, in which dialogue related to poor prognosis occurred during the final 1 to 2 disease reevaluation discussion recorded before the patient’s death. All patients in this group died while on study. Earlier prognostic communication typically centered on discussion of sites of disease and treatment options, without direct connection to curability. In 5 dyads, the parent’s perception of prognosis evolved to become closer to the oncologist’s, describing cure in the spectrum of unlikely to impossible before the child’s death; 1 remaining parent declined to answer postrecording questions related to prognosis.

Seed Planting: Early Discussion About Poor Prognosis, Laying Foundation for Frank Disclosure

The third pattern occurred in 5 dyads, representing 4 oncologists, in which dialogue describing poor prognosis occurred across earlier recordings, laying the groundwork for future difficult conversations. Three patients in this group died on study; after 24 months, 2 remained alive with active disease. In 3 dyads, the parent’s perception of curability gradually decreased to align more closely with their oncologist’s impression; 1 parent declined to answer and 1 parent remained confident about a good prognosis (notably, this parent’s child was alive after 24 months on study).

DISCUSSION

We present the findings from a mixed-methods, prospective, longitudinal, cohort study of prognostic communication across a child’s advancing cancer trajectory. By building on previous retrospective and cross-sectional investigation of prognostic communication, this study design allowed us to examine the evolution and impact of prognostic communication across illness progression extending to death. Given the sample size, our findings may not be generalizable; yet they highlight potential opportunities for improvement in clinical care provision.

Overall, prognostic communication comprised <4% of recorded dialogue in this study. Lack of dialogue related to prognosis is particularly striking when juxtaposed with the fact that oncologists rated curability as unlikely or very unlikely at study entry for 80% of patients in this cohort. Frank statements about poor prognosis were identified rarely in recorded discussions. On occasions when prognosis was discussed, indirect language was often used to describe curability, paralleling findings from the literature in which adult oncologists often use indirect language when disclosing prognosis.29 Our findings suggest that oncologist-parent discordance in prognostic understanding is not due solely to a lack of receptivity or understanding on the part of parents; rather, lack of specific prognostic disclosure on the part of oncologists likely plays a role.

When direct incurability statements occurred, the language was clear, honest, and compassionate, and these statements were often associated with increasing prognostic awareness for parents. However, the low frequency of prognostic communication by oncologists is worrisome in concert with oncologist-parent discordance in prognostic understanding. Similar discordance has been seen previously, with pediatric patients with cancer and parents reporting higher chances of cure relative to oncologists,14,16,30 highlighting the need for research to better understand how different communication approaches influence prognostic understanding.

Toward this end, we examined progression of language over time and found that achievement of oncologist-parent concordance in perceived curability generally followed recordings with direct statements about disease incurability. We identified absent, deferred, and seed-planting patterns of prognostic communication evolution, and described evidence to suggest that seed-planting patterns yield improvements in prognostic understanding across time. These findings support frameworks that encourage preemptive “what if?” conversations with children with cancer and their families as a potential mechanism to explore informational and emotional needs, goals of care, and prognostic understanding during times of relative disease stability.31 Additional reflective questions and prompts to encourage clinicians in the practice of patient- and/or parent-centered, timely prognostic communication are offered in Supplemental Table 8.

Although absent or delayed prognostic communication is a key contributor to oncologist-parent discordance in prognostic understanding, other factors likely influence parental understanding of prognosis, including health literacy, personal experiences, intrinsic personality traits, religiosity, worldview, and coping preferences. Specific best practices to guide content, timing, and delivery of individualized, patient- and/or parent-centered prognostic disclosure in pediatrics are not known. We do know, however, that parents of children with cancer desire detailed, longitudinal prognostic conversations, with many parents wishing for more prognostic information than they received, nearly no one preferring to hear less prognostic information, and most wanting serial conversations about prognosis across time.4 In contrast to these preferences, in our study, we found that most prognostic communication occurred in the setting of significant disease progression, with infrequent discussion of prognosis arising during periods of disease stability. These findings suggest an opportunity to develop and study the effect of clinical interventions aimed toward improving the amount and frequency of prognostic dialogue across the advancing illness course.

A growing adult oncology literature centered on strategies to improve prognostic communication may help inform the next steps in pediatric oncology. When adult oncologists use a serious illness communication guide they are more likely to have earlier, better, and more frequent serious illness conversations with advancing patients with cancer.32 A similar approach has not yet been investigated in pediatric cancer and may hold promise. Use of the “surprise question” (ie, “Would I be surprised if this patient died in the next year?”) also has been shown to be a feasible and effective tool to identify adult patients with cancer33 and children34 in their last year of life. Whether integration of the surprise question into clinical practice can impact the frequency, timing, and quality of prognostic disclosure by pediatric oncologists is unknown and warrants investigation.

Ultimately, drivers of oncologist communication behaviors are likely multifactorial, including clinician desire to preserve hope and maintain therapeutic alliance.6,7 The advent of new therapies also fosters prognostic uncertainty35 and hinders discussion of incurability. Although parents generally wish for more, not less, prognostic information, oncologists appear to respond in different ways depending on the family. Oncologists may try to read the room to determine how much information to disclose and when the right time is for frank discussion. However, the exploration of approaches for how and when to disclose prognostic information in alignment with patient and family preferences remains understudied. More research is needed to determine how patients and families perceive and benefit from different communication patterns.

Study limitations include its single-site design and sample size, which may limit generalizability. Sample bias for parents hoping for cure may be higher at an academic cancer center that draws patients for phase I/II trials. Oncologists occasionally declined the research team’s request to approach a dyad, generating potential for gatekeeper bias. Additionally, parents who were receptive to participate may have been more receptive to prognostic conversations. Participating oncologists represent both sexes and a wide range of experience levels, yet all are white, representing lack of eligible multiracial faculty. Dyad recruitment was conducted sequentially, as opposed to purposively, resulting in underrepresentation of racial and ethnic minorities. Multiracial dyads did not decline participation more than white dyads in the pilot,28 suggesting that use of purposive sampling in future studies may improve representation. A few discussions were not recorded because of logistic and/or staffing issues or at the request of the participating patient or parent, and several parents declined to complete surveys or interviews; these missing data could influence synthesis and interpretation of findings.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, improving communication around prognosis for children with cancer and their families has been identified as a top research priority by experts in oncology and palliative care.23,36 The literature reveals that parents of children with advancing cancer frequently make decisions on the basis of unrealistic expectations,16 suggesting that new strategies for effective prognosis communication are needed.16 The U-CHAT study offers insights into how prognostic information is shared, processed, and understood by pediatric oncologists, patients with advancing cancer, and their families, suggesting opportunities to explore benefits of integrating direct statements about incurability across a seed-planting pathway. We hope these data may offer a framework to develop and investigate communication-based clinical interventions geared toward improving prognostic understanding and overall communication experiences for this vulnerable patient population.

Supplementary Material

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT:

Children with cancer and their parents want honest and frequent prognostic communication, yet many parents identify deficits in the quality of prognostic information received. Improved parental prognostic understanding is associated with improved clinical outcomes for patients and families.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS:

With this longitudinal study, we analyzed >140 serial conversations among oncologists, children with advancing cancer, and families, in which prognostic communication represented <4% of dialogue. Direct incurability statements appeared to improve prognostic understanding, and distinct patterns of prognostic disclosure were identified.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors acknowledge the Quality of Life Research Division for its support of this study.

FUNDING:

Partially supported by Dr Kaye’s Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and by ALSAC. Additionally, Dr Lemmon receives salary support from the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (K23NS116453).

ABBREVIATION

- U-CHAT

Understanding Communication in Healthcare to Achieve Trust

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: Dr Lemon has received compensation for medicolegal work; the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2021-050208.

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Parental distress and desire for information regarding long-term implications of pediatric cancer treatment. Cancer 2018;124(23): 4529–4537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Communication about prognosis with adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: information needs, prognostic awareness, and outcomes of disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(18): 1861–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang T, Mack JW. Parent understanding of the risk of future limitations secondary to pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65(7):e27020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. Prognostic disclosures over time: parental preferences and physician practices. Cancer 2017;123(20):4031–4038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaye E, Mack JW. Parent perceptions of the quality of information received about a child’s cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60(11):1896–1901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics 2014;133(suppl 1):S24–S30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helft PR. Necessary collusion: prognostic communication with advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(13): 3146–3150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Peace of mind and sense of purpose as core existential issues among parents of children with cancer. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2009; 163(6):519–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Communication about prognosis between parents and physicians of children with cancer: parent preferences and the impact of prognostic information. J Clin Oncol 2006;24(33):5265–5270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2007; 25(35):5636–5642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marron JM, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Intended and unintended consequences: ethics, communication, and prognostic disclosure in pediatric oncology. Cancer 2018;124(6):1232–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mack JW, Cook EF, Wolfe J, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children with cancer: parental optimism and the parent-physician interaction. J Clin Oncol 2007;25(11):1357–1362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Kang TI, et al. Differences in parent-provider concordance regarding prognosis and goals of care among children with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32(27):3005–3011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. How parents of children with cancer learn about their children’s prognosis. Pediatrics 2018;141(1):e20172241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. JAMA 2000;284(19):2469–2475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mack JW, Cronin AM, Uno H, et al. Unrealistic parental expectations for cure in poor-prognosis childhood cancer. Cancer 2020;126(2):416–424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaye EC, Kiefer A, Zalud K, et al. Advancing the field of communication research in pediatric oncology: a systematic review of the literature analyzing medical dialogue. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65(12):e27378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kamihara J, Nyborn JA, Olcese ME, Nickerson T, Mack JW. Parental hope for children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics 2015;135(5):868–874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nyborn JA, Olcese M, Nickerson T, Mack JW. “Don’t try to cover the sky with your hands”: parents’ experiences with prognosis communication about their children with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med 2016;19(6):626–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sisk BA, Mack JW, Ashworth R, DuBois J. Communication in pediatric oncology: state of the field and research agenda. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2018;65(1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist 2000;5(4):302–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan M SPIKES: a framework for breaking bad news to patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2010;14(4): 514–516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gilligan T, Coyle N, Frankel RM, et al. Patient-clinician communication: American Society of Clinical Oncology Consensus Guideline. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35(31):3618–3632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fenton JJ, Duberstein PR, Kravitz RL, et al. Impact of prognostic discussions on the patient-physician relationship: prospective cohort study. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(3):225–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract 2018;24(1):120–124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schönfelder W CAQDAS and qualitative syllogism logic-NVivo 8 and MAXQDA 10 compared. Forum Qual Soc Res 2011;12: 21 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Birks M, Francis K. Memoing in qualitative research: probing data and processes. J Res Nurs 2008;13:68–75 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Bluebond-Langner M, Baker JN. Longitudinal investigation of prognostic communication: feasibility and acceptability of studying serial disease reevaluation conversations in children with high-risk cancer. Cancer 2020;126(1):131–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chou WYS, Hamel LM, Thai CL, et al. Discussing prognosis and treatment goals with patients with advanced cancer: a qualitative analysis of oncologists’ language. Health Expect 2017;20(5):1073–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Communication about prognosis with adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: information needs, prognostic awareness, and outcomes of disclosure. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(18): 1861–1867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Snaman JM, Feraco AM, Wolfe J, Baker JN. “What if?”: addressing uncertainty with families. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2019;66(6):e27699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paladino J, Bernacki R, Neville BA, et al. Evaluating an Intervention to Improve Communication between Oncology Clinicians and Patients with Life-Limiting Cancer: A Cluster Randomized Clinical Trial of the Serious Illness Care Program. In: JAMA Oncol, vol. 5. 2019: 801–809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moss AH, Lunney JR, Culp S, et al. Prognostic significance of the “surprise” question in cancer patients. J Palliat Med 2010;13(7):837–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burke K, Coombes LH, Menezes A, Anderson AK. The ‘surprise’ question in paediatric palliative care: a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2018;32(2): 535–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.LeBlanc TW, Temel JS, Helft PR. “How much time do I have?”: communicating prognosis in the era of exceptional responders. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:787–794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Baker JN, Levine DR, Hinds PS, et al. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care. J Pediatr 2015;167(2): 467–70.e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kaye E, Snaman J, Johnson L, et al. Communication with Children with Cancer and Their Families throughout the Illness Journey and at the End of Life. In: Wolfe J, Jones B, Kreicbergs U, Jankovic M, eds. Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pino M, Parry R, Land V, Faull C, Feathers L, Seymour J. Engaging terminally ill patients in end of life talk: how experienced palliative medicine doctors navigate the dilemma of promoting discussions about dying. PLoS One 2016; 11(5):e0156174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kruser JM, Nabozny MJ, Steffens NM, et al. “Best case/worst case”: qualitative evaluation of a novel communication tool for difficult in-the-moment surgical decisions. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015;63(9): 1805–1811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kruser JM, Taylor LJ, Campbell TC, et al. “Best case/worst case”: training surgeons to use a novel communication tool for high-risk acute surgical problems. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53(4):711–719.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarze ML, Zelenski A, Baggett ND, et al. Best case/worst case: ICU (COVID-19)-A tool to communicate with families of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Palliat Med Rep 2020;1(1):3–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.