Abstract

As mental disorders impact quality of life and result in high costs for society, it is important patients receive timely and adequate care. This scoping review first aims to summarize which factors contribute to specialized mental health care (SMHC) use. Within the Dutch health care system, the general practitioner (GP) is the filter for SMHC and care use costs are relatively low. Second, to organize factors by Andersen and Newman’s care utilization model in illness level, predisposing, and enabling factors. Third, to assess equity of access to SMHC in the Netherlands. A health care system is equitable when illness level and the demographic predisposing factors age and gender account for most variation in care use and inequitable when enabling factors and social predisposing factors such as education predominate. We identified 13 cross-sectional and cohort studies in the Netherlands published between 1970 and September 2020 with 20 assessed factors. Illness level factors, disease severity, diagnosis, personality, and comorbidity contributed the most to SMHC use. Predisposing factors related to a more solitary lifestyle contributed to a lesser degree. Enabling factors income and urbanicity contributed the least to SMHC use. These results imply inequity. Factors that did not fit the care utilization model were GP related, for example the ability to recognize mental disorders. This emphasizes their importance in a system where patients are dependent on GPs for access to SMHC. Focus should be on improving recognition of mental disorders by GPs as well as collaboration with mental health care professionals.

Keywords: Mental health care, psychiatric diseases, Andersen-Newman’s care utilization model, access to care, predisposing and enabling factor

Introduction

Annually, almost 1 in 5 people in the Netherlands suffer from at least 1 mental disorder. 1 Next to the impact on the quality of life of both patients and their caregivers, 2 mental disorders result in high costs for society due to the use of health services, employment loss, and reduced productivity. 3 This stresses the importance of patients receiving timely and adequate care. To describe access to care Goldberg and Huxley 4 proposed “the pathways to care model.” A model where the general practitioner (GP) represents the essential filter to specialized care. Due to different types of health care systems per country, international comparisons provide limited perspectives on the factors determining access to specialized mental health care (SMHC). The objective of the present review is to identify all factors contributing to SMHC use within the Dutch health care system, a health care system where costs are relatively low for the rates of care utilization, compared to other countries. 5 In the Netherlands, formal referral by a GP is required to access SMHC. Health care is organized with the aim to provide access equal to all citizens. Health insurance is obligated for everyone and insurance companies are obligated to accept every citizen and cover most of the costs of evidence-based treatments. A review of factors contributing to SMHC in the Netherlands could inform policymakers in the Netherlands and in countries with similar health care systems. If the Dutch health care system is deemed equitable from this review, results could be taken into consideration for adopting this type of health care system for countries with health care systems that do not have GPs as a filter for SMHC.

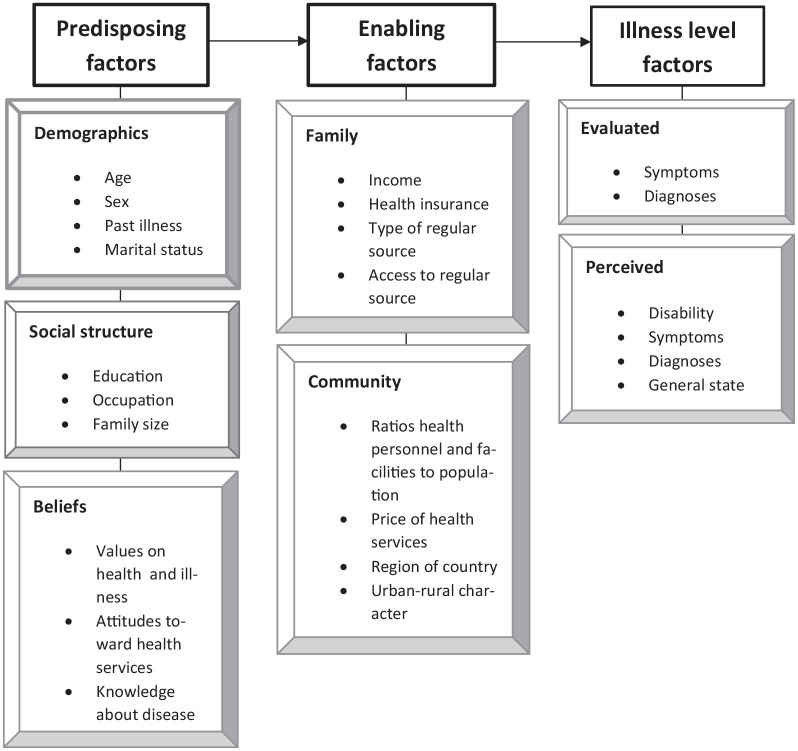

Factors that determine health care use are classified in the Behavioral Model of Health Services Utilization by Andersen and Newman 6 (Figure 1). This model on care use consists of illness-level factors, predisposing factors, and enabling factors. 6 Illness level factors include both the patient’s and the professional’s perspective on health, described as the perceived and evaluated illness level. The perceived illness level comprises the individual’s perception of his health, consisting of the experienced symptoms, the number of disability days, and general health state. The evaluated illness level is assessed by a health professional and reflects symptoms, diagnoses, and illness severity. 6 Predisposing factors refer to demographics (eg, age, gender, and marital status), social structure (eg, educational level, ethnicity, and occupation), and beliefs (eg, values on health and illness, attitudes on health services, and knowledge of disease). Enabling factors determine the ability to secure health care services, such as the individual’s finances, insurance, and also the availability of adequate care. 6 In the Netherlands, health insurance is compulsory for all inhabitants and almost all health care use is reimbursed. There is a well-developed system of mental health care providers available throughout the country. Therefore, it is expected that enabling factors have a small contribution to SMHC use. People with a low-income get financial support from the Dutch government to pay for their health insurance. However, people annually must pay a fixed amount when using specialized care before the insurance covers the costs, which could be a barrier to use SMHC. The Netherlands has a good geographical availability of GPs and hospitals within the maximum of a 30-minute car ride. Also, the Netherlands has the lowest unmet need for care compared to other European countries due to costs, distance, or waiting times with little difference between income groups. 7 If health services are distributed equally and fairly, a health care system is deemed equitable. Whether there is equity in access to care depends on which factors account for most of the variance in care use. According to Andersen and Davidson 8 , access to care in a health care system is deemed equitable when illness level factors, and to a lesser extent the demographic predisposing factors age and gender, explain most of the variation in utilization. It would be undesirable and inequitable when enabling factors, such as income and social predisposing factors such as educational level, decide whether people access care. 8

Figure 1.

Andersen and Newman’s 6 behavioral model of health services utilization.

This review analyses literature on the contribution of illness level, predisposing, and enabling factors to the referral or use of SMHC, organized by the care utilization model of Andersen and Newman. 6 Until now, knowledge on factors determining pathways to SMHC use is fragmented as international comparisons provide limited perspectives, due to different types of health care systems per country. A scoping review is conducted, to summarize research on factors contributing to SMHC in the Netherlands and identify gaps in current research. This review has 3 objectives: (1) to map all contributing factors to SMHC use found in literature, (2) to organize these factors by the care utilization model of Andersen and Newman, and (3) to evaluate equity of access to SMHC use within a health care system that is expected to have almost no enabling barriers. The outcomes of the review demonstrate which factors contribute and whether access to SMHC is equitable in the Netherlands. The results inform health care providers on what patients with certain characteristics or contexts have lower chances of receiving adequate care.

Methods

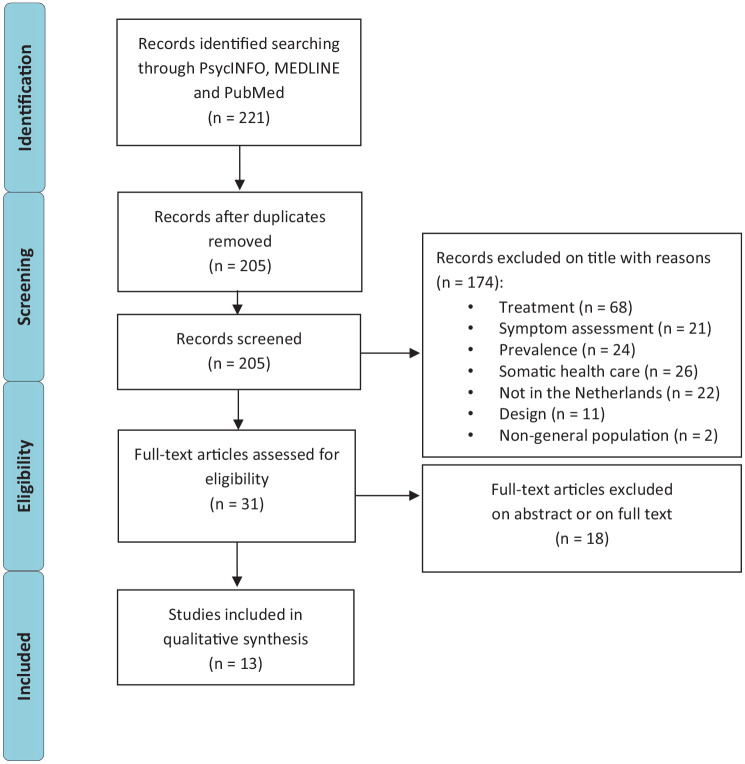

A literature search was done following the PRISMA-ScR guideline for scoping reviews. 9 The following search strategy was used to search the title and abstract on factors of SMHC use in the Netherlands: (“Netherlands”) AND (“primary health care”) AND (“exp Community Mental Health Services/or exp Mental Health Services/or exp Mental Disorders/” or “mental health”.mp. or exp Mental Health/). The search was performed in the databases Psych INFO, Medline (Ovid), and PubMed in September 2020. A flow chart shows which studies were excluded and for what reasons (Figure 2). Next, the lead author screened the studies by title and abstract and selected prospective cross-sectional or cohort studies of the Dutch health care system to assess predictive factors of SMHC. Papers had to be published in English and all date ranges were included. Research was included when factors for referral or use of SMHC were studied. Studies that were duplicates or focused on specific (disease) populations or treatments and studies on symptom assessment were excluded. This review focused on SMHC use for people in the general population and patients with common mental disorders to generalize the results to access to the SMHC sector and not only for certain types of treatments for a specific mental disorder. Studies were eligible when they were performed in the general population, in SMHC patients, in patients in a primary care setting or when the studies were comparisons between these groups. From the included studies we first recorded study characteristics, like inclusion criteria, sample size, and design. Next, the effect sizes of the factors associated with referral to or use of SMHC (odds ratios, relative risk ratios, or correlations with P-values) were extracted from the studies that were included. Then, the factors were organized by both the lead and the second author according to the care utilization model of Andersen and Newman, 6 in illness level factors, predisposing factors, and enabling factors. Illness level factors were split into evaluated and perceived illness level factors. Predisposing factors into demographics, social structure, and beliefs. Enabling factors were divided by income and community factors. Other factors that are not included in the model of Andersen and Newman, were categorized as additional factors. After organizing the factors by category, equity of access to SMHC in the Netherlands was assessed on the impact of the factors per category on referral to or use of SMHC. The effect sizes of factors within each study indicated its relevance for referral to or use of SMHC. All reported relative risk ratios (RRR; ratio of probabilities, the likelihood an event occurs compared to all events), odds ratios (OR; comparing non-events with events, as a ratio of ratios), and correlations (r) with the use of SMHC are described. 10 As this review relied only on published secondary data, institutional review board approval was not required.

Figure 2.

Search and screening results.

Results

The literature search identified 13 studies in 5 cohorts that described factors associated with utilization of SMHC (Table 1).

Table 1.

Study populations.

| Study | Authors | Inclusion | Population | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NEMESIS-I | Bijl et al 11 | Sufficiently speaking Dutch. | First wave: n = 7076. | Prospective longitudinal cohort study. |

| Aged 18-64 years. | Second wave: n = 5618. | |||

| Not institutionalized for long periods. | Third wave: n = 4848. | |||

| Fixed address. | ||||

| NEMESIS-II | de Graaf et al 13 | Sufficiently speaking Dutch. | First wave: n = 6646. | Prospective longitudinal cohort study. |

| Aged 18-64 years. | Second wave: n = 5303. | |||

| Not institutionalized for long periods. | Third wave: n = 4618. | |||

| Fixed address. | ||||

| NESDA | Penninx et al 15 | Community sample: see NEMESIS. | Community sample: n = 564. | Multisite naturalistic cohort study. |

| Primary care sample: patients aged 18-65 years who consulted a GP divided by current diagnosis of depression/anxiety, life-time diagnosis, or subthreshold symptoms or a family history of depression/anxiety, and a group of healthy controls. | Primary care practices: n = 1610 patients and n = 65 GPs. | |||

| Mental health care organizations: patients with primary depressive or anxiety DSM-IV disorder. | Mental health care organizations: n = 807. | |||

| NIVEL a | Foets et al 17 | Registered as patient in a Dutch general practice of a practicing GP on 1-1-1985 (when the sample was drawn). | n = 161 GPs within n = 103 practices and n = 335 000 practice population, of which n = 9 practices, n = 808 patients followed for 12 months. | Longitudinal prospective cohort study. |

| Wilmink et al study | Wilmink et al 19 | Patients are seen within 10 days by GPs from the northern Netherlands and registered with a GP for at least 12 months. | n = 25 GPs and n = 1994 patients with a follow-up of patient management information. | Prospective cohort study. |

| Dutch cultural background. | ||||

| Aged 16-65 years. |

Abbreviations: NEMESIS, Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study; NESDA, Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety; NIVEL, The Netherlands Institute of Health care Research.

Dutch National Study of Morbidity and Intervention in General Practice conducted by the NIVEL.

Study Characteristics

The first Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS-I cohort) measured DSM-III psychiatric disorders in the general population in 3 waves between 1996 and 1999, 11 and showed that 4.3% used SMHC in the final wave. 12 The NEMESIS-II cohort was conducted in the general population between 2007 and 2009 13 of which 5.2% used SMHC. 14 The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) cohort 15 recruited people in the general population, multiple local general practices, and regional mental health care organizations. Personality traits were, amongst other factors, assessed in both NEMESIS and NESDA. Participants of NESDA were divided into 3 groups: the first group consisted of people with the current diagnosis of a depressive or an anxiety disorder, the second group of people who have had earlier episodes or were at risk because of family history or subthreshold depressive or anxiety symptoms, and the third group without depressive or anxiety disorder or symptoms. Within the first group, 13.6% of people with a current depressive or anxiety diagnosis used SMHC. 16 The fourth cohort was set up by the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) and randomly selected GPs in the Netherlands 17 who were asked to keep a record of the morbidity of all registered patients. After 1 year, psychosocial and general health problems were assessed. The records demonstrated 1310 referrals to SMHC or social work. 18 The fifth cohort consisted of 25 randomly selected GPs who registered every patient’s demographics, the reason for visit, and the GP’s judgment of somatic or psychiatric complaints. Of these patients, 3.4% used SMHC. 19

Major findings

Factors that were associated with SMHC use were categorized by illness level, predisposing, and enabling factors as described in the framework of Andersen and Newman (Table 2). Factors that could not be classified under these categories, were analyzed as additional factors.

Table 2.

Study results: factors of SMHC.

| Category | Factor | Outcome* | Analysis | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illness level | Severity 14 | Severe mental disorder | RRR = 30.58, adjusted for gender and age; RRR = 24.81, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. |

| Moderate mental disorder | RRR = 7.85, adjusted for gender and age; RRR = 7.05, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. | |||

| Mild mental disorder | RRR = 3.30, adjusted for gender and age; RRR = 3.16, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. | |||

| Illness level | Diagnosis 20 | Schizophrenia | OR = 6.97, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | Logistic regression analyses. |

| Bipolar disorder | OR = 6.81, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Major depression | OR = 6.31, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Panic disorder | OR = 3.63, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Generalized anxiety disorder | OR = 3.34, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | OR = 2.91, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Agoraphobia (without panic) | OR = 2.61, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Dysthymia | OR = 2.30, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. | |||

| Illness level | Personality | Neuroticism | r = .42, χ2 = 57.52, df = 14, P = .000. 12 | |

| OR = 6.51, adjusted for the number of somatic disorders; OR = 3.40, adjusted for the number of somatic disorders and depressive- and anxiety disorders. 21 | Multiple logistic regression analysis. | |||

| OR = 1.06, entered variables: confidence in professional and confidence in help from relatives and friends. 16 | ||||

| OR = 1.04, adjusted for symptoms of depression and anxiety (severity), age, gender, and education level. 22 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. | |||

| Conscientiousness | OR = 1.04, adjusted for symptoms of depression and anxiety (severity), age, gender, and education level. 22 | |||

| Illness level | Comorbidity | Number of diagnoses of mental illness | OR = 1.47, entered variables: confidence in professional and confidence in help from relatives and friends, neuroticism, having at least 1 depressive disorder, having at least 1 anxiety disorder, severity of depression, and patient perceives a mental health problem him/herself. 16 | Multilevel logistic regression analysis. |

| Multiple mental disorders | OR = 6.09, adjusted for gender, age, and comorbidity. 20 | |||

| Any physical disorder | RRR = 1.53, adjusted for gender and age. 14 | Logistic regression analyses. | ||

| Substance use disorders and a somatic condition | RRR = 2.49, unadjusted; RRR = 2.15, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. | ||

| Anxiety disorders and a somatic condition | RRR = 1.58, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Substance use disorder with digestive tract disorder | RRR = 5.43, unadjusted; RRR = 3.09, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Substance use disorder with chronic backache | RRR = 4.90, unadjusted; RRR = 6.05, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Substance use disorder with hypertension | RRR = 3.72, unadjusted. 23 | |||

| Anxiety disorder with digestive tract disorder | RRR = 3.20, unadjusted; RRR = 3.56, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Mood disorder with digestive tract disorder | RRR = 2.96, unadjusted; RRR = 2.92, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Mood disorder with rheumatoid arthritis | RRR = 2.25, unadjusted; RRR = 3.04, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Anxiety disorder with chronic backache | RRR = 1.91, unadjusted; RRR = 2.14, adjusted for age, gender, education level, living situation, work status, and degree of urbanization. 23 | |||

| Illness level | Impairments | Emotional role functional impairments † | OR = 7.83, unadjusted; OR = 2.85, adjusted for education and DSM-III-R disorder. 24 | Logistic regression analysis. |

| Social functional impairments † | OR = 5.01, unadjusted; OR = 2.47, adjusted for education and DSM-III-R disorder. 24 | |||

| Multiple functional impairments † | OR = 4.61, unadjusted; OR = 2.86, adjusted for mental disorder, living alone, and low perceived social support. 25 | |||

| Predisposing | Demographics | 25-34 years of age | RRR = 1.56, adjusted for age and gender. 14 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. |

| 35-44 years of age | RRR = 1.52, adjusted for age and gender; RRR = 1.75, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | |||

| 45-54 years of age | RRR = 1.58, adjusted for age and gender. RRR = 1.99, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | |||

| Male gender and younger age | χ2 = 628, df = 39, P < .001, with interactions between age and diagnoses, age and gender, and gender and diagnosis. 18 | |||

| Female gender | RRR = 1.35, adjusted for age and gender. 14 | Analysis of variance and hierarchical log linear analysis. | ||

| Predisposing | Social structure | Education | ⩾16 years OR = 2.39, 13-15 years OR = 2.00 and 12 years OR = 1.67, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. |

| OR = 1.09, adjusted for DSM-III-R disorder and functional impairment. 24 | ||||

| t = 12.412, P = .000, β = .094, r = .06, adjusted for anxiety- and/or depressive disorder. 12 | Logistic regression analyses. | |||

| Primary basic vocational education | RRR = 1.85, adjusted for age and gender. 14 | Structural equation modeling. | ||

| Higher secondary vocational education | RRR = 0.71, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. | ||

| Lower secondary vocational education | RRR = 0.57, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | |||

| Unemployed | RRR = 3.26, adjusted for age and gender; RRR = 2.25, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | |||

| OR = 1.95, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | ||||

| Retired | OR = 1.85, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | Logistic regression analyses. | ||

| Low perceived social support | OR = 2.78, unadjusted; OR = 1.7 entered variables: multiple functional impairments and DSM-III-R disorder. 25 | Logistic regression analyses. | ||

| Females aged 45-64 with multiple functional impairments ‡ OR = 12.02, non-adjusted. 25 | Bivariate and multiple logistic regression analysis. | |||

| Without partner | RRR = 3.77, adjusted for age and gender; RRR = 2.32, adjusted for age, gender, severity of mental disorder, physical disorder, education, having a partner, job status, income, and urbanization. 14 | Logistic regression analyses. | ||

| Living alone | OR = 2.60, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. | ||

| OR = 1.85, unadjusted; OR = 1.42 entered variables: multiple functional impairments and DSM-III-R disorder. 25 | Logistic regression analyses. | |||

| Females aged 45-64 with multiple functional impairments ‡ OR = 11.25, non-adjusted. 25 | Bivariate and multiple logistic regression analysis. | |||

| Single parent status | OR = 1.94, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | Bivariate and multiple logistic regression analysis. | ||

| Predisposing | Beliefs | Confidence in professional help | OR = 1.54, entered variables: confidence in professional and confidence in help from relatives and friends and neuroticism; OR = 1.73, entered variables: confidence in professional and confidence in help from relatives and friends, neuroticism, having at least 1 depressive disorder, having at least 1 anxiety disorder, severity of depression, and patient perceives a mental health problem him/herself. 16 | Bivariate and multiple logistic regression analysis. |

| Confidence in help from relatives and friends | OR = 0.71 (for entered variables see Confidence in professional help); OR = 0.73 (for entered variables see Confidence in professional help). 16 | Multilevel logistic regression analysis. | ||

| Enabling | Middle-income level | OR = 1.38, adjusted for age, gender, and DSM-III-R diagnoses. 20 | Multilevel logistic regression analysis. | |

| Low household income | RRR = 4.01, adjusted for age and gender. 14 | Logistic regression analyses. | ||

| Urban character of practice area | F = 4.46, P < .01, referral ratio large city practice areas = 10.21, urban practice areas = 6.35, suburban practice areas = 5.75, and rural practice areas = 4.73. 18 | Analysis of variance and hierarchical log linear analysis. | ||

| Additional | Recognition of mental disorder by the GP | OR = 3.0.26,27 | Difference of proportions test. | |

| Overtly expressed psychological distress | P < .05. 28 | T-tests. | ||

| Type of practice | F = 4.34, P < .01, referral ratio health centers = 8.70, 2 partner practices = 5.99, doctors in group practices = 5.23, and single-handed practices = 4.79. 18 | Multinomial logistic regression analysis. | ||

Abbreviations: df, degrees of freedom; OR, Odds Ratio; r, Correlation coefficient; RRR, Relative Risk Ratio; SMHC, specialized mental health care.

Only significant results are presented in this table, see references for exact P-values.

Perceived illness level factor (all other illness level factors are evaluated illness level factors).

Interaction effects of multiple functional impairments combined with 2 dimensions of social support: living alone and perceived social support. These interactions regarding SMHC use only appeared for women aged 45 to 64.

Illness level factors

Evaluated illness level factors

Four evaluated illness factors were found: severity, diagnosis, personality, and comorbidity. People with severe (RRR = 30.58, 95% CI: 20.26-46.15), moderate (RRR = 7.85, 95% CI: 5.19-11.87), and mild mental disorder (RRR = 3.30, 95% CI: 2.07-5.25) were in an ascending trend more likely to use SMHC compared to people without mental disorder. 14 Patients with a formal diagnosis of schizophrenia (OR = 6.97, 95% CI: 2.53-19.22), bipolar disorder (OR = 6.81, 95% CI: 3.60-12.89), or major depression (OR = 6.31, 95% CI: 4.49-8.86), had the highest likelihoods to use SMHC, compared to people with other psychiatric diagnoses. Next, patients with panic disorder (OR = 3.63, 95% CI: 2.33-5.65), generalized anxiety disorder (OR = 3.34, 95% CI: 1.61-6.91), obsessive compulsive disorder (OR = 2.91, 95% CI: 1.14-7.38), agoraphobia (without panic; OR = 2.61, 95% CI: 1.30-5.26), or dysthymia (OR = 2.30, 95% CI: 1.36-3.90) were more likely to use SMHC compared to patients without these disorders. Whereas patients with a diagnosis of a (social) phobia, alcohol/drug abuse or dependence, or bulimia nervosa were not more likely to use SMHC than patients with other psychiatric diagnoses. 20 Also, people with high scores on neuroticism were more likely to use SMHC (OR = 3.40, 95% CI: 2.35-4.90; r = .42, χ2 = 57.52, df = 14, P < .001), compared to people with lower scores.12,21 For patients with 1 or more DSM-IV depressive and/or anxiety disorder, high scores on neuroticism/conscientiousness increased the likelihood of being referred to SMHC compared to patients with lower scores on the 2 personality traits, which was irrespective of the severity of the disorder (OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00-1.08; OR = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00-1.07, respectively). Patients with high scores on other personality traits, such as extraversion, openness, and agreeableness, were not more likely to be referred to SMHC. 22 Having a comorbid psychiatric disorder increased the likelihood to use SMHC, compared to people with a single diagnosis in the NEMESIS-I cohort (OR = 6.09, 95% CI: 3.19-11.62) 20 and in the NESDA population (OR = 1.47, 95% CI: 1.01-2.13). 16 Patients with a comorbid physical disorder were also more likely to use SMHC, compared to people without a physical disorder (RRR = 1.53, 95% CI: 1.18-1.98). 14 Patients with a substance use disorder and a comorbid physical disorder more often used SMHC (RRR = 2.49, 95% CI: 1.40-4.40), compared to patients without a comorbid physical disorder, in particular in the case of digestive tract disorder (RRR = 5.43, 95% CI: 2.23-13.23). 23

Perceived illness level factors

People with problems in daily activities due to emotional problems (“emotional role impairments”) had a higher likelihood of utilizing SMHC, compared to people who did not have these impairments (OR = 2.85, 95% CI: 2.06-3.95). People with social impairments, which include problems in one’s social activities as a result of emotional or physical problems, also had a higher likelihood to use SMHC (OR = 2.47, 95% CI: 1.76-3.46). 24 However, emotional and social role impairments were not associated with SMHC use in another study. 12 Having multiple functional impairments had an effect on the likelihood of SMHC use compared to people with few or no functional impairments (OR = 2.86, 95% CI: 2.08 -3 .93). 25

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors were categorized by demographics, social structure, and beliefs.

Demographics

People aged 25 until 54 years were more likely to use SMHC than people of 55 to 64 years in NEMESIS-II (Table 2), whereas people aged 18 to 24 years did not differ from the group of 55 to 64 years. Women were more likely to use SMHC than men in NEMESIS-II (RRR = 1.35, 95%CI: 1.04-1.76), 14 while men were more often referred to SMHC in the NIVEL cohort. 18 In NESDA and NEMESIS-I age and gender were not associated with SMHC use.16,20

Social structure

Being higher educated was a predisposing factor for SMHC use in NEMESIS-I (OR = 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01-1.18 and b = 0.094, t = 12.412, P < .000)12,24; people with more than 12 years of education were more likely to use SMHC compared to people with less education (Table 2). 20 On the contrary, in NEMESIS-II, people with lower primary basic vocational education, were more likely to use SMHC compared to people with higher professional or university education (RRR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.08-3.18). 14 Level of education was not a factor for SMHC use in NESDA. 16

One study reported that people who were retired, irrespective of their age and gender, were more likely to use more SMHC (OR = 1.85, 95% CI: 1.21-2.85). 20 Unemployed (including disabled) people were more likely to use SMHC in NEMESIS-I (OR = 1.95, 95% CI: 1.33-2.84) compared to employed people. Similar results were found for unemployed people in NEMESIS-II (RRR = 2.25, 95% CI: 1.59-3.18). 14 Unemployment was not a predisposing factor in the NESDA cohort. 16

People with low perceived social support had higher odds to use SMHC compared to people with higher perceived social support (OR = 2.78, 95% CI: 2.09-3.69). 25 Patients without a partner and patients who live alone were more likely to use SMHC when compared to patients with a partner (respectively RRR = 2.32, 95% CI: 1.45-3.73 and OR = 2.60, 95% CI: 2.01-3.36; Table 2).14,20,25 Single parents were also more likely to use SMHC (OR = 1.94, 95% CI: 1.26-2.98). 20

Beliefs

Attitudes on mental health services were associated with SMHC use: people with positive confidence in professional help use SMHC more often (OR = 1.73, 95% CI: 1.16-2.58), as well as people with negative confidence in help from relatives and friends (OR = 0.73, 95% CI: 0.54-0.98). 16

Enabling factors

Income

In the NESDA cohort, income was not associated with SMHC use, 16 but people with middle-income levels were more likely to use SMHC, irrespective of DSM-III-R diagnoses, compared to people with low-income levels in the NEMESIS-I cohort (OR = 1.38, 95%CI: 1.05-1.83). 20 However, in the NEMESIS-II cohort people with low-income levels were more likely to use SMHC, compared to people with high-income levels (RRR = 4.01, 95%CI: 2.91-5.54). 14

Community

While in most cohorts urbanization was not associated with SMHC use,14,16,20 the urban character of the practice area had a relationship with referral in the NIVEL cohort: the urbanization degree was associated with a higher chance of being referred to SMHC (F = 4.46, P < .01). 18

Additional factors of SMHC not included in the Andersen and Newman model

Besides the factors described in the model of Andersen and Newman, additional factors not included in the model and related to the general practice were found. GPs referred more patients to SMHC (F = 4.34, P < .01) in multidisciplinary health centers, than GPs in 2-partner practices, doctors in group practices, or solo-practices. 18 The GP’s ability to recognize mental disorder(s) was also important, as patients who were diagnosed with a mental disorder by their GP were more likely to refer to SMHC compared to unrecognized mental disorder patients (OR = 3.0, no 95% CI provided). The GP’s recognition of psychiatric disorder depended on the reason for encounter, severity, recency of onset, exacerbation of disorder, and comorbidity.26,27 In addition, patients who overtly expressed psychological distress to their GP in a demand for psycho-social help, were more often referred to SMHC than patients who presented their psychological distress as physical complaints. 28

Discussion

Main results on factors organized by the care utilization model

In this review 13 studies which assessed 20 factors in total were associated with SMHC use in the Netherlands. We used Andersen and Newman’s care utilization model to organize these factors by category. Almost all factors could be organized in illness level, predisposing, and enabling factors. Illness level factors and predisposing factors had the greatest contribution to SMHC use. Enabling factors were found to have the least contribution. Unexpectedly, a fourth category that was not included in the care utilization model was found. This category is related to the role of the GP in the Dutch health care system. Results are discussed below in more detail, what factors per category were found as well as equity implications of access to SMHC in the Dutch health care system.

Results for illness level factors

Notably, illness-level factors have the greatest contribution to SMHC use. Having a more severe mental illness, the diagnosis schizophrenia, comorbidity with other mental or physical disorders, more functional impairments, and the personality traits neuroticism and consciousness were associated with SMHC use. First, severity of mental illness was associated with the use of SMHC. 14 The relative risk ratio increased for each severity category, so as expected, people with a higher severity of mental illness were more likely to use SMHC. Second, higher chances were found for specific mental disorders. As expected, schizophrenia had the strongest association with SMHC use. 20 As schizophrenia is advised to be diagnosed and treated in SMHC, at least at illness onset, 29 it is not surprising that these patients have a higher chance of using SMHC. Third, comorbid mental or physical disorder, or alcohol/drug abuse increased utilization of SMHC.14,16,20,23 This is also unsurprising, as comorbidity indicates a higher complexity of patients’ mental illness. Comorbidity could require more specialized treatment than in primary care and is included as a referral criterion (other criteria include inadequate treatment response, recurrence, chronic, or severe symptoms) in clinical guidelines for GPs on anxiety and depressive symptoms.30,31 Fourth, certain personality traits of patients with depressive and anxiety disorders were associated with SMHC use: neuroticism and conscientiousness.12,16,21,22 As several studies found an association between neuroticism, conscientiousness, and the severity of depression and anxiety,32-34 this could explain the association between these personality traits and SMHC. Fifth, another expected result was that patients with more functional impairments had a higher chance of using SMHC than patients with less functional impairments.24,25 Functional impairments consist of problems in daily and social activities. Although the association with these impairments was inconsistent, a possible explanation for higher SMHC use could be, that for GPs more impairments imply higher consequences and impact of mental and sometimes also somatic illness on a patients’ life. Therefore, GPs would find these patients in more urgent need of SMHC than people with fewer impairments.

Results for predisposing factors

After illness level factors, predisposing factors contributed most to SMHC use. Being without a partner, 14 living alone,20,25 unemployed,14,20 having low social support, 25 and high confidence in professional help or low confidence in help of relatives or friends, 16 were associated with SMHC use, even after adjustment for (severity of) mental disorder. These results imply, that especially people who live more solitary with less social contacts, are more likely to receive SMHC. Lack of a social network could be a reason to refer someone to specialized care sooner.

Conflicting results were found for gender, age, and education. Women were more likely to use SMHC in NEMESIS-II but, men were more likely to be referred to SMHC in the NIVEL study. An explanation may be that men consult their GP when symptoms are more severe when referral is appropriated, 18 while women generally use more primary and specialized care services for mental health issues. 35 One study showed that being of middle age was associated with SMHC use. However, this was the case for SMHC use in both specialized and primary care setting compared to no use of these services. When analyzing SMHC use versus primary care mental health care use, age no longer contributed as a factor. This indicates that gender and age have an effect independent of factors related to the mental disorder. Besides, the predictive value of these factors is not necessarily related to the type of health care system, as age and gender were also found as factors for SMHC use in countries both with similar and different health care systems. 35 We also found an association between the level of education and SMHC use. However, this finding was not consistent. While in NEMESIS-I more education years were associated with more SMHC use,12,20,24 in NEMESIS-II this association was reversed. 14 However, in NEMESIS-II, the association was no longer present when controlled for severity of mental disorder. This is likely due to the fact that lower education correlates with more severe psychopathology. Speculating about possible interpretations, 1 study 36 found an association between higher education and insight about the attribution of symptoms among outpatients with depressive disorders. Another study, 37 found lower education in patients with mental disorders associated with poorer insight in their thought processes regarding their illness. Hence, patients with a higher education level who have more insight into their symptoms might communicate psychological problems more adequately with their GP, resulting in more referrals to SMHC. Another possible explanation, might be that people with a higher education act sooner upon symptoms of mental disorders in seeking for help, compared to people with a lower education. One study, 38 found an association between higher education and more positive views on the necessity of seeking help, but also a shorter duration without psychiatric treatment. Lastly, a potential explanation might be that cognitive behavioral therapy and psychotherapy provided in SMHC, demand patients’ insight into emotional symptoms and communicating these. This might be a reason not to refer someone. Future studies should investigate whether higher educated people have a better reaction to these interventions.

Results for enabling factors

The enabling factors were the least studied type of factors. This might be explained by the expectation that these types of factors only have a minor role in SMHC use due to the obligated health insurance covering most of the costs. With respect to the enabling factors that were studied, only income and urbanicity of the general practice were associated with SMHC use. However, some remarks must be made about these results. In NEMESIS-II, people with a low-income level were more likely to use SMHC. 14 As with education, this association is probably due to a confound with severity of psychopathology. When controlling for severity of the mental disorder, low-income was no longer associated with SMHC use. In NEMESIS-I, middle-level compared to low-level income was associated with SMHC use. 20 However, in the study this analysis was not controlled for illness severity. It is unknown whether middle-level income would still be associated after controlling for severity. Also, the association with urbanicity was only found in 1 study and could possibly be due to the increased availability of mental health care in larger cities. 18 Other enabling factors that were not studied but could have an association with SMHC are the size of the waiting list for SMHC in the area of the patient and the number of SMHC facilities nearby. Although, the urban character of the area of the patient was measured as an indicator for availability of facilities, there could be discrepancies in the number of SMHC facilities between cities with a high urbanization level.

Results for GP factors

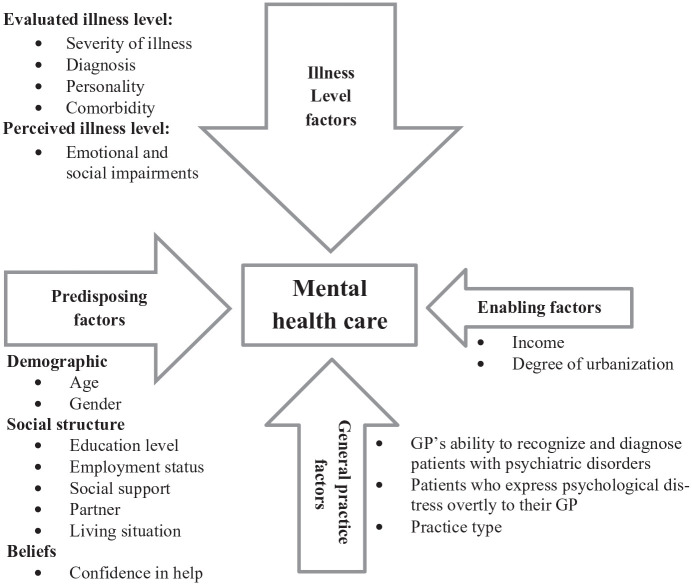

Strikingly, factors that did not fit the model of Andersen and Newman but were nonetheless significant in predicting referral to SMHC, were related to the GPs themselves. As GPs are the filter for SMHC in the Dutch system, this is important because this could mean that care accessibility is next to factors related to the patient also dependent on factors related to the GP. The type and intensity of treatment could be determined by which GP the patient consults. This could suggest that factors related to the filter to SMHC in other types of health care systems may also be important. One of the GP factors found was related to mental disorder recognition. GPs who recognized their patients’ mental disorders referred more patients to SMHC.26,27 Patients that presented with a psychological or a social reason for encounter, experienced more severe disorder, had a recent onset or exacerbation, or had multiple disorders, were better recognized by their GP. 28 Also, GPs who consulted patients in multidisciplinary health centers referred more patients to SMHC, which could be due to more communication and consultation between GPs and mental health care providers. 18 Although the importance of the variation in the experience of doctors with certain diseases is mentioned in the care utilization model, 8 it is not included as a separate category but rather mentioned as a social component of evaluated illness level factors. We would suggest a separate category in the model to emphasize the importance of GP factors (Figure 3). The GP factors could be especially relevant for mental health care use, as GPs report experiencing a lack of skill and time constraints to treat patients with psychological problems as well as communication problems with SMHC.39,40 This could have an impact on patient management and therefore on access to care.

Figure 3.

Factors of SMHC.

Abbreviation: SMHC, specialized mental health care.

The magnitude of the arrows indicates the size of the association of the factors with SMHC.

Equity implications

In an equitable health care system, illness level and demographic predisposing factors should predominate access to care. In contrary, when enabling and social predisposing factors explain most variation in care use, a health care system is deemed inequitable. 8 The results of this review show that illness level factors have the greatest contribution and enabling factors the least, suggesting equity. These results support the claim that adopting a system in which the GP is the filter to SMHC would be beneficial in countries with different health care systems. Nonetheless, the social predisposing factors have a contribution as well. The impact of these factors implies inequity. More awareness amongst GPs regarding the differentiation between patients on factors such as social support and education level is important. However, the predisposing factors associated with SMHC use found in the Netherlands are highly similar to factors found in other high-income countries as well as in low-income countries. 35 Additional factors related to the GP that do not fit the care utilization model contribute as well. The impact of GP factors such as the ability to recognize mental disorders and the type of general practice, emphasize the importance of these factors in a health care system where access to SMHC depends on GPs. It is unclear whether this would imply inequity, because in the Dutch health care system every patient requires a referral from their GP in order to access SMHC. Factors related to the GP have a higher degree of mutability compared to enabling and social predisposing factors. This means there are opportunities to improve a health care system where SMHC use depends on GPs. A first step would be the enhancement of knowledge and recognition of mental disorders through continuing education for GPs. Also, we expect that the collaboration between GPs and mental health care professionals will further increase the chance of detecting mental disorders. 41 Providing the GP with direct access to psychiatric consultation within general practice may decrease practice variation in referral and thereby improving health care quality for patients with mental disorders. 40

Future directions in research

Not all illness-level factors mentioned in the Andersen and Newman model, such as past illness, knowledge of mental disorders, and the patient’s values concerning health were studied in this review. These factors are recommended to include in future studies. More research on factors of mental health care use in the general population is also advised as these studies are mostly done in specific subpopulations with a single or a group of mental disorders. Another recommendation would be, to also study the contribution of other GP factors, such as the GP’s satisfaction with cooperating with SMHC or the GP’s perspectives on treating patients with symptoms of mental disorder by prescribing medication. Also, to study these GP factors in other countries with a similar health care system. It would be interesting to study the contribution of factors related to all concerned parties in the general practice: GP’s, patients, mental health care specialists the GP communicates with, and the amount of mental health care experience within the general practice. Lastly, it would be relevant to also study the contribution of GP factors on SMHC use in health care systems where the GP has a less central role. Although SMHC can be accessed directly, patients must pay for using care depending on their health insurance, which could be a barrier to access SMHC. It is interesting to know whether other factors or similar predisposing, enabling, and illness level factors are associated in countries where the GP is not a gatekeeper of SMHC. This could lead to insights on what impact the role of the GP has on which type of patients use SMHC and which health care system has more equitable access to SHMC.

Limitations

This review has several limitations. First, while the NEMESIS cohort included the general population, NESDA included people with symptoms or a diagnosis of a depressive and/or anxiety disorder, which hinders generalization of the results to patients with other mental disorders. Second, all reviewed studies were of a cross-sectional design, so no causal conclusions could be drawn. Third, the studies used different terms for the outcome variable: most studies assessed factors associated with SMHC use and some assessed factors associated with referral. The studies on referral were included because these also included predictors from the GP. However, not all people will use health care services after referral. 42 Finally, not all factors of Andersen and Newman’s model were assessed in the reviewed studies: the predisposing factors past illness, knowledge of disease, and values concerning health and illness were not reported in the reviewed studies.

Conclusions

In 13 studies 20 factors contributed to SMHC use in the Netherlands. These factors could be organized in illness level, predisposing, and enabling factors according to the care utilization model. Three additional factors were found related to the GP that do not fit within the organization of the care utilization model. Although the Dutch health care system aims for equity of access to care, the contribution of enabling factors income and urbanicity and social predisposing factors related to a more solitary lifestyle, could possibly be barriers in access to SMHC. The GP factors associated with SMHC such as the ability to recognize mental disorders, demonstrate the importance of these factors in a health care system where patients are dependent on their GP for referral to SMHC. Still, illness level factors, such as mental illness and its severity, have the greatest contribution in access to SMHC in the Netherlands. This shows that access to SMHC within the Dutch health care system overall is equitable, but there is room for improvement. To reduce the influence of factors not directly related to the illness of the patient, the first step could be increasing knowledge and recognition of mental disorders through continuing education for GPs as well as improving communication with mental health care professionals.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The included studies on the NESDA cohort were funded through the Geestkracht program of the Dutch Scientific Organization (ZON-MW, grant number 10-000-1002) and matching funds from participating universities and mental health care organizations (VU University Medical Center, GGZ Buitenamstel, GGZ Geestgronden, Leiden University Medical Center, GGZ Rivierduinen, University Medical Center Groningen, Lentis, GGZ Friesland, GGZ Drenthe), Scientific Institute for Quality of Healthcare (IQhealthcare), Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL), and Netherlands Institute of Mental Health and Addiction (Trimbos). The included studies on the NEMESIS cohort were funded through the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport (VWS), the Medical Sciences Department of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO), and the National Institute for Public Health and Environment (RIVM). The NEMESIS-II cohort with the included studies was funded through the Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, with supplementary support from the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and the Genetic Risk and Outcome of Psychosis (GROUP) investigators. The NIVEL cohort with the included studies was funded by the Ministry of Welfare, Health and Cultural Affairs and the National Council of Sickness Funds. The Wilmink cohort with the included studies was supported by grant no. 900-556-002 from the Foundation for Medical and Health Research (MEDIGON) of the NWO and by grant no. 28-1209 from the Dutch Prevention Fund.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: DD and ED created the search criteria and strategy. DD executed the primary and performed the secondary screening with ED, organizing the factors from the included studies. DD, ED, DB, AB, and AJB all contributed to writing and approving the final manuscript.

ORCID iD: Daphne Aimée Van der Draai  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1058-5845

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1058-5845

References

- 1. de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Gool C, van Dorsselaer S. Prevalence of mental disorders and trends from 1996 to 2009. Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study-2. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2012;47:203-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vos T, Barber RM, Bell B, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Lancet. 2015;386:743-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2017. Published 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272735/9789241514019-eng.pdf?ua=1

- 4. Goldberg D, Huxley P. Mental Illness in the Community: The Pathway to Psychiatric Care. Tavistock; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024-1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andersen R, Newman JF. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1973;51:95-124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. State of Health in the EU. Country Health Profile; 2019. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/state/docs/2019_chp_nl_english.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 8. Andersen R, Davidson P. Improving access to care in America: individual and contextual indicators. In: Andersen RM, Rice TH, Kominski GF, eds. Changing the US Health Care System: Key Issues in Health Services Policy and Management. Jossey-Bass; 2007:3-31. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Last A, Wilson S, Rao G. Relative risks and odds rations: what’s the difference? J Fam Pract. 2004;53:108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bijl RV, van Zessen G, Ravelli A, de Rijk C, Langendoen Y. The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study (NEMESIS): objectives and design. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1998;33:581-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ten Have M, Iedema J, Ormel J, Vollebergh W. Explaining service use for mental health problems in the Dutch general population: the role of resources, emotional disorder and functional impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41:285-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Graaf R, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S. The Netherlands mental health survey and incidence study-2 (NEMESIS-2): design and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2010;19:125-141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ten Have M, Nuyen J, Beekman A, de Graaf R. Common mental disorder severity and its association with treatment contact and treatment intensity for mental health problems. Psychol Med. 2013;43:2203-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, et al. The Netherlands study of depression and anxiety (NESDA): rationale, objectives and methods. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2008;17:121-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Verhaak PF, Prins MA, Spreeuwenberg P, et al. Receiving treatment for common mental disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:46-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Foets M, van der Velden J, de Bakker D. Dutch National Survey of general practice: a summary of the survey design. Published 1992. https://www.nivel.nl/sites/default/files/bestanden/1002614.pdf?

- 18. Verhaak PF. Analysis of referrals of mental health problems by general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1993;43:203-208. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wilmink FW, Ormel J, Giel R, et al. General practitioners’ characteristics and the assessment of psychiatric illness. J Psychiatr Res. 1989;23:135-149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bijl RV, Ravelli A. Psychiatric morbidity, service use, and need for care in the general population: results of the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Am J Public Heal J Public Heal. 2000;90:602-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ten Have M, Oldehinkel A, Vollebergh W, Ormel J. Does neuroticism explain variations in care service use for mental health problems in the general population? Results from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study (NEMESIS). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2005;40:425-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seekles WM, Cuijpers P, van de Ven P, et al. Personality and perceived need for mental health care among primary care patients. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:666-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Ten Have M, Penninx BW, Beekman AT, Smit JH, De Graaf R. Presence of comorbid somatic disorders among patients referred to mental health care in the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:1119-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ten Have M, Oldehinkel A, Vollebergh W, Ormel J. Does educational background explain inequalities in care service use for mental health problems in the Dutch general population? Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:178-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ten Have M, Vollebergh W, Bijl R, Ormel J. Combined effect of mental disorder and low social support on care service use for mental health problems in the Dutch general population. Psychol Med. 2002;32:311-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ormel J, Van DenBrink W, Koeter MW, et al. Recognition, management and outcome of psychological disorders in primary care: a naturalistic follow-up study. Psychol Med. 1990;20:909-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ormel J, Koeter MW, van den Brink W, van de Willige G. Recognition, management, and course of anxiety and depression in general practice. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:700-706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Verhaak PF, Tijhuis MA. Psychosocial problems in primary care: some results from the Dutch national study of morbidity and interventions in general practice. Soc Sci Med. 1992;35:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hasan A, Falkai P, Wobrock T, et al. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia – a short version for primary care. Int J Psychiatr Clin Pract. 2017;21:82-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. GGZ Standaarden. Zorgstandaard Depressieve Stoornissen. Published 2018. https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/depressieve-stoornissen/samenvatting

- 31. GGZ Standaarden. Zorgstandaard Angstklachten En Angststoornissen. Published 2017. https://www.ggzstandaarden.nl/zorgstandaarden/angstklachten-en-angststoornissen/samenvatting.

- 32. Karsten J, Penninx BW, Riese H, Ormel J, Nolen WA, Hartman CA. The state effect of depressive and anxiety disorders on big five personality traits. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46:644-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Newby J, Pitura VA, Penney AM, Klein RG, Flett GL, Hewitt PL. Neuroticism and perfectionism as predictors of social anxiety. Pers Individ Dif. 2017;106:263-267. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Boudouda NE, Gana K. Neuroticism, conscientiousness and extraversion interact to predict depression: a confirmation in a non-Western culture. Pers Individ Dif. 2020;167:1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110219 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang PS, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, et al. Use of mental health services for anxiety, mood, and substance disorders in 17 countries in the WHO world mental health surveys. Lancet. 2007;370:841-850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yen CF, Chen CC, Lee Y, Tang TC, Ko CH, Yen JY. Insight and correlates among outpatients with depressive disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2005;46:384-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sagayadevan V, Jeyagurunathan A, Lau YW, et al. Cognitive insight and quality of life among psychiatric outpatients. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Madianos MG, Zartaloudi A, Alevizopoulos G, Katostaras T. Attitudes toward help-seeking and duration of untreated mental disorders in a sectorized Athens area of Greece. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47:583-593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. van Rijswijk E, van Hout H, van de Lisdonk E, Zitman F, van Weel C. Barriers in recognising, diagnosing and managing depressive and anxiety disorders as experienced by family physicians; a focus group study. BMC Fam Pract. 2009;10:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fredheim T, Danbolt LJ, Haavet OR, Kjønsberg K, Lien L. Collaboration between general practitioners and mental health care professionals: a qualitative study. Int J Ment Health Syst. 2011;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Magnée T, de Beurs DP, de Bakker DH, Verhaak PF. Consultations in general practices with and without mental health nurses: an observational study from 2010 to 2014. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Orden ML, Deen ML, Spinhoven P, Haffmans J, Hoencamp E. Five-year mental health care use by patients referred to collaborative care or to specialized care. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:840-844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]