Abstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has had a profound impact on the world. To address the impact of COVID-19 in the state of Hawai‘i, the Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA) Community Care Outreach Unit conducted an assessment survey to determine the impact of COVID-19 on the health and social welfare of individuals and their families across the state. This article presents key statewide findings from this assessment, including areas of need and community-based recommendations to help mitigate the impact of the pandemic, particularly for vulnerable groups. A total of 7927 participants responded to the assessment survey from across the state's counties. In all questions related to paying for essentials, the percentage of participants that expect to have problems in the future, as compared to now, almost doubled. Slightly higher than one-third reported that they would know how to care for a family member in the home with COVID-19, and half of the respondents reported a lack of space for isolation in their home. About half reported that if they got COVID-19, they would have someone available to care for them. Overall, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Filipino groups reported greater burden in almost all areas surveyed. The results presented provide a baseline in understanding the impact, needs, and threats to the health and social welfare of individuals and their families across the state of Hawai‘i. Local stakeholders can utilize this information when developing priorities, strategies, and programs to address current and future pandemics in the state.

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2), has had a profound impact on the world, with 33 496 454 cases reported and 602 401 lives lost in the United States as of July 1, 2021.1 The US national response plan for most disasters is based on state and local planning and response that is augmented, when necessary, with federal assets. Knowing where these assets should be focused to serve the community better is vital, especially as social determinants of health are key factors in determining health outcomes in underserved and racial minority population groups.2,3

Data from California, Alaska, Hawai‘i, Oregon, Colorado, Utah, and King County in Washington state documented that Native Hawaiian (NH) and Pacific Islander (PI; termed as indigenous to regions of Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia) populations have disproportionately higher rates of COVID-19 cases compared to other racial or ethnic groups.4–6 Hawai‘i COVID-19 data reports indicate NHs have approximately one-fifth of all cases, which is proportional to their population; however, PI and Filipino ethnicities have disproportionately high rates relative to the overall population.4 As of June 30, 2021, PIs in Hawai‘i have the highest proportion of COVID-19 cases (20%), hospitalizations (28%), and deaths (21%), though this ethnic group makes up only about 4% of the total population.4 Filipinos in Hawai‘i, which are 16% of the population, have the second-highest proportion of COVID-19 cases (20%), hospitalizations (22%), and deaths (23%).4

Likewise, inequities in social determinants, which have been linked to higher rates of chronic conditions, such as obesity and diabetes, further exacerbate the risks of severe symptoms and consequences of COVID-19.6 Racial minorities in the United States are exposed to COVID-19 at higher rates due mainly to greater representation in the essential workforce, which is needed for critical infrastructure operations to continue. For example, Filipino Americans account for approximately 45% of the nurses in Hawai‘i and 20% of the nursing workforce in California and typically work in frontline specialties, such as intensive care units, that care for patients with COVID-19.2,7,8 Socio-cultural factors also put NH, PI, and Filipino families at higher exposure and transmission of COVID-19 due to multi-generational households, cultural practices where social distances are considered disrespectful, and stigma-related to contracting the disease, which results in delayed or no reporting.5,9 Health care options are influenced by culture and religion; hence, COVID-19 information is more likely to be effective if delivered with cultural sensitivity.2

In addition to the health needs of the community, the COVID-19 pandemic has presented unique challenges for the state: (1) Hawai‘i depends on tourism as the key driver of its economy, (2) most food and other goods are imported, and (3) geographical isolation reduces the delivery of rapid mutual aid from other states. To protect its population, the Hawai‘i State government made an early decision to markedly limit tourism, enact strict social distancing and isolation directives, and curtail all commerce that was not deemed to be essential. Despite these actions, COVID-19 cases increased, and a severe concern emerged regarding the current and projected impact of pandemic response on citizens’ health and social welfare across the state. In particular, as demonstrated by the findings of this study, vulnerable populations (1) had a higher burden of cases, (2) experienced greater challenges financially, and (3) had to navigate institutional changes caused by the pandemic (e.g., work, school, access to care, resources, and information).

The Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency (HI-EMA) was activated, using the National Incident Management System's Incident Command System (ICS) structure to manage the state's pandemic response.10 Within the ICS operations section, a medical and public health branch was formed, and within this branch, a Community Care Outreach Unit (CCO Unit) was established. The mission of the CCO Unit was to monitor the health and social welfare capacity, needs, and threats to members of the community due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Hawai‘i, and work with community members to recommend mitigation strategies. As a first step, the CCO Unit surveyed community-based health and social service entities and community organizations across the state to help identify the needs and threats of individual aggregate groups within Hawaii's population.11 This information was integral to recruiting community partners for the CCO Unit, which comprised key leaders from the NH, PI, and Filipino communities and stakeholders with in-depth expertise in the areas of rural communities, homelessness, and the elderly.

The partners collaborated to develop an assessment survey to examine the Impact of COVID-19 on Individuals Health and Social Welfare (ICIHSW) in Hawai‘i. Assessment data was collected from individuals across the state during a period of 3 weeks. During this time the COVID-19 pandemic in the state was at its peak and public officials and citizens were all very concerned for the health and safety for citizens of the state. This article presents key statewide findings from the ICIHSW assessment survey and community partners' recommendations to mitigate the pandemic's impact, particularly for vulnerable groups across the state.

Methods

In collaboration with the CCO Unit, essential health and social service entities, community organizations, and multiple key agencies and organizations from across the state provided their expertise and assistance in developing the ICIHSW survey questions, identifying dissemination strategies, analyzing and interpreting the findings, and recommending data distribution and mitigation strategies (Appendix A). The survey contained 35 questions that collected information about demographics, household profiles, health and well-being, family finances, social welfare, personal beliefs, and activities regarding COVID-19. The survey tool also included questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) to assess mental health (emotion level).12 See Appendix B for specific questions on the ICIHSW 35-item assessment survey.

A mixed-methods framework was utilized for ICIHSW survey distribution and recruitment of participants from across the state, with special outreach to vulnerable populations. Recruitment strategies included snowball sampling via website and social media advertisements, word-of-mouth, and paper ICIHSW survey with return postage mailers available for in-person completion at agency sites, community meeting places, and homeless outreach clinics. Survey shepherds were utilized to help assist or arrange assistance for individuals completing the ICIHSW online or in-person. Both electronic and paper formats were distributed across all counties in the state. Community partners served as the lead survey shepherds and identified processes for dissemination and participant recruitment, including navigating access to vulnerable populations. The ICIHSW assessment survey was open from August 12, 2020, through September 5, 2020.

Descriptive analysis of the statewide data is presented to give a basic overview of the status of COVID-19 burden in Hawai‘i. The results presented provide an initial understanding of the impact, needs, and threats to the health and social welfare of individuals and their families in Hawai‘i.

Results

Demographics

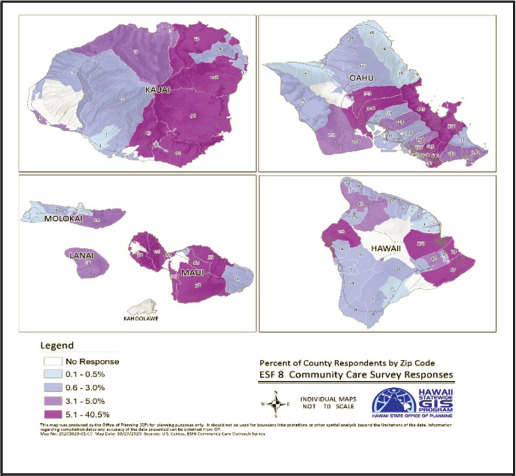

A total of 7927 participants (69.3% female, 25.4% male, and 5.3% who identify as ‘non-binary‘) responded to the ICIHSW assessment survey from across the state's counties (Kaua‘i [5.3%], Honolulu [75.4%], Maui [7.4%], and Hawai‘i [11.9%]). See Figure 1 for survey response across counties. The race/ethnicity groups the participants most closely self-identified with were White (34.8%), Asian (28.8%), NH (14.2%), Filipino (11.6%), PI (3.5%), and other (7.0%). Of note, the Filipino group was identified as a vulnerable group and separated from the Asian category for this article. According to the US Census Bureau, 37.6% of the state's population is Asian, and 10.1% is NH/PI.13 See Table 1 for detailed demographic data.

Figure 1.

State of Hawai‘i Survey Response by County by Zip Code

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| nb | %c | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Women | 5465 | 69.3 |

| Men | 2004 | 25.4 |

| Non-binarya | 419 | 5.3 |

| County | ||

| Hawai‘i | 938 | 11.9 |

| Honolulu | 5968 | 75.4 |

| Kaua‘i | 420 | 5.3 |

| Maui | 583 | 7.4 |

| Age Group | ||

| 18–24 | 1163 | 14.9 |

| 25–34 | 1302 | 16.6 |

| 35–44 | 1580 | 20.2 |

| 45–54 | 1383 | 17.7 |

| 55–64 | 1315 | 16.8 |

| 65 and older | 1083 | 13.8 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 2704 | 34.8 |

| Filipino | 904 | 11.6 |

| Asian | 2240 | 28.8 |

| Native Hawaiian | 1108 | 14.3 |

| Pacific Islander | 264 | 3.5 |

| Other (eg, black, Hispanic, Other) | 549 | 7.1 |

Non-binary refers to the self-reported sexual identity of the survey respondent.

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Household Profile

Across the state, 17.2% of the participants reported a total family annual income of less than $40 000, and 20.7% reported an income between $46 000 and $75 000. The median household income range was reported to be $76 000 to $125 000. This range is consistent with the median Hawai‘i State household income of $83 102, reported by the US Census Bureau.22 About one-third (32.2%) of the participants experienced reduced work hours, 19.6% reported that they lost their job, and 11.2% experienced increased work hours. Amongst the identified vulnerable groups, participants identifying as PI had the lowest household income of less than $75 000 (66%), followed by NH (44%) and Filipino (41%). The Filipino participants reported the highest reduction in work hours due to COVID-19 (42%) compared to other racial and ethnic groups. NH and PI participants also had the highest percentage that reported losing their job—both at 32% (Table 2).

Table 2.

Estimated Income and Impact on Employment and Work Hours Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927) After COVID-19

| na | %b | |

|---|---|---|

| Income Range (in 2019) | ||

| Less than $40 000 | 1361 | 17.2 |

| $41 000–$75 000 | 1639 | 20.7 |

| $76 000–$125 000 | 2082 | 26.3 |

| $126 000 or more | 1752 | 22.1 |

| Choose not to answer | 1082 | 13.7 |

| Employment or Work Hour Changes After COVID-19 | ||

| No effect | 2923 | 37.0 |

| Increased work hours | 886 | 11.2 |

| Reduced work hours | 2544 | 32.2 |

| Lost job | 1552 | 19.6 |

| Impact On Household Income | ||

| No effect | 3158 | 39.9 |

| Yes, a little | 1930 | 24.4 |

| Yes, a moderate amount | 1433 | 18.1 |

| Yes, a large amount | 1393 | 17.6 |

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

The majority of the participants responded to having at least 1 other person in the household (89%), about one-third reported having at least 1 person aged 65 years or older, and one-third reported having at least one child younger than 18 years living in the home.

Digital Connectivity

Overall, 99% of participants reported having both internet connectivity at either home or work and that someone in the home had a cell phone that worked.

Housing

Survey participants were asked where they live now and where they expected to live in 3 months. At the time of the survey, 58.2% of the respondents statewide owned their place of residence, and 38.2% of respondents rented living space. However, in 3 months, each category dropped (48.2% and 32.8%, respectively). The percent of those that responded houseless increased from 0.5% now to an expected 1.3% in 3 months (Table 3).

Table 3.

Housing Situation Today and Likely in 3 Months Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| Housing Situation | TODAY na (%b) | 3 Months From Now na (%b) |

|---|---|---|

| A home, condo, or apartment that you OWN. | 4588 (58.2) | 3803 (48.2) |

| A home, condo, or apartment that you RENT. | 3005 (38.5) | 2578 (32.8) |

| Houseless: Live with others that you know, in their home or apartment. | 272 (3.5) | 317 (4.0) |

| Houseless: Live in a public shelter. | 22 (0.3) | 32 (0.4) |

| Houseless: Live in a tent, car, or outside. | 13 (0.2) | 70 (0.9) |

| Essentials | TODAY | 3 Months From Now |

| Food | 979 (12.4) | 1821 (23.1) |

| Rent or mortgage | 1142 (14.5) | 2222 (28.2) |

| Auto expenses (eg, gas, insurance, car payments) | 1099 (14.0) | 1942 (24.7) |

| Medicines | 657 (8.4) | 1206 (15.4) |

| Utility bills (eg, electric, water, cable, internet) | 1090 (13.9) | 1839 (23.4) |

| Cell phone, internet, cable bill | 1055 (13.4) | 1741 (22.1) |

| Care for children and older persons | 416 (5.3) | 720 (9.2) |

| Health care | 816 (10.4) | 1437 (18.3) |

| Public transportation | 312 (4.0) | 536 (6.8) |

| Other debts | 1244 (15.8) | 1966 (25.0) |

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Daily Essentials

In every category of paying for various essentials, the percentage of families with problems paying for essentials now compared to in 3 months almost doubled. Respondents predicted that by December 2020, nearly one-quarter of the respondents would have difficulties paying for food, rent/mortgage, auto expenses, utility bills, cell/internet costs, and health care/medicines (Table 3).

Challenges with School

More than one-half of respondents (55.5%; n=5502) expect to have someone in the household in school in fall 2020. Expected challenges included lack of funds to purchase school supplies (20%; n=881), lack of face-covering (10%; n=428); and language barrier (2.5%; n=110).

Language Spoken Mostly in the Home, and Translation Needs

Over 92% of respondents (n=7167) reported that English is the language that is most spoken in the home. Translation needs not met were reported by 179 (7.6%) of respondents; most were for health (n=82), social services (n=57), and educational services (n=40). The PI group had the highest proportion of language barriers.

Use of Statewide Assistance Hotline Number (211)

Only 4% of respondents (n=317) reported that they ever called 211 for social service assistance.14 Of these 317 individuals, 39% reported that they did receive the assistance that they requested. Thirty-two percent reported they did not receive the assistance that they requested, and 32% reported that they were only directed to an internet site.

Attempt at Applying for Benefits

Respondents were asked about success with the application for benefits in the areas of health insurance, finance, food, or health services. Health insurance and health benefits were the easiest to complete; over 80% reported success in completing these applications. Several of the service areas seemed to be more challenging to apply for; 70.4% reported success in completing applications for food assistance, 67.4% were successful for financial assistance, but only 43.6% were successful with completing the application for rent assistance. The most common reasons for not completing an application included finding out how to complete the form or not having all the documents. For some, contacting the agency via the telephone was a barrier (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Outcomes When Applying for Assistance Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| Type of Assistancea | Applied | If YES, Were You Able to Complete the Application? | If NO, You Could Not Complete the Application: Reason(s) [Check All That Apply] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n (%) | Yes n (%) | No n (%) | No internet access n (%) | Could not figure out how to navigate the form n (%) | Did not have all the documents n (%) | Do not understand questions in English n (%) | Tried to call on phone butcould not get through n (%) | |

| Prequalification for financial hardship relief | 817 (11.2) | 693 (67.4) | 335 (32.6) | 25 (7.5) | 109 (32.5) | 106 (31.7) | 7 (2.1) | 95 (28.4) |

| Rental assistance | 292 (4.2) | 224 (43.6) | 289 (56.3) | 20 (6.9) | 70 (24.2) | 74 (25.6) | 9 (3.1) | 58 (20.1) |

| Food | 822 (11.4) | 678 (70.4) | 285 (29.6) | 12 (4.2) | 74 (26.0) | 66 (23.2) | 8 (2.8) | 47 (16.5) |

| Health insurance | 1344 (18.6) | 1258 (83.3) | 253 (16.7) | 12 (4.7) | 53 (21.0) | 42 (16.6) | 7 (2.8) | 33 (13.0) |

| Healthcare benefits (eg, Med-QUEST or WIC) | 1023 (14.2) | 913 (80.5) | 221 (19.5) | 12 (5.4) | 53 (24.0) | 43 (19.5) | 6 (2.7) | 38 (17.2) |

Abbreviation: WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children.

Type of assistance applied for in Hawai‘i between August 12, 2020, and September 5, 2020.

Chronic Disease Burden

More than half (56.1%) of the participants reported that at least 1 household member had at least 1 chronic disease. Asthma, obesity, diabetes, and mental health disorders were most commonly reported. As shown in Table 5, those that self-identified as NH, PI, or Filipino reported a disproportionate number of chronic diseases among household members compared to respondents from the state as a whole.

Table 5.

Chronic Disease Burden Among Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, and Filipino Respondents that Report at Least 1 Household Member Having a Chronic Disease (N=7927)

| Chronic Disease | Native Hawaiian (n=1108) n (%) | Pacific Islander (n=264) n (%) | Filipino (n=904) n (%) | Statewide (N=7927) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 319 (29.2) | 100 (39.2) | 257 (28.8) | 1500 (19.0) |

| Heart disease | 181 (16.6) | 40 (16.0) | 122 (13.7) | 982 (12.4) |

| Asthma | 411 (37.7) | 82 (32.6) | 268 (30.0) | 2010 (25.5) |

| Lung disease | 40 (3.6) | 8 (3.2) | 26 (2.9) | 255 (3.2) |

| Kidney disease | 44 (4.0) | 24 (9.5) | 61 (6.8) | 300 (3.8) |

| Mental health illness | 191 (17.6) | 37 (14.9) | 114 (12.8) | 1181 (15.0) |

| Obesity | 338 (31.0) | 69 (27.3) | 172 (19.3) | 1478 (18.7) |

| Cancer | 70 (6.4) | 24 (9.6) | 43 (4.8) | 413 (5.2) |

Usual Source of Health Care

The majority reported that they usually receive health care in a family doctor's office (70.9%), hospital-based clinic (17.6%), or community health center (12.4%). Some participants reported having either no usual source of health care or using the emergency department as their usual source of health care (9.2%; Table 6).

Table 6.

Usual Source of Health Care Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| Usual Source of Health Care | na | %b |

|---|---|---|

| Family doctor office | 5598 | 70.9 |

| Community health center or community | 976 | 12.4 |

| Hospital based clinic | 1385 | 17.6 |

| Emergency department | 315 | 4.0 |

| Have no usual source of healthcare | 344 | 4.4 |

| Other | 378 | 4.8 |

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Mental Health

The survey tool included the 4 questions from the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) to assess mental health (emotional level).12 About half (54.4%) of statewide respondents reported being bothered by feelings of being nervous, worried, having little pleasure, or feeling down at least several days over the past 2 weeks. One third of respondents (33.5%) reported feeling nervous more than half or nearly every day in the past 2 weeks, and 24.7% reported feeling worried more than half or almost every day in the past 2 weeks.

A mental health score was then computed via assigning points for the reported level of each emotion; about one-quarter (27%) of respondents statewide had a moderate or severe negative emotion score (Table 7).

Table 7.

Mental Health Scores Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| PHQ-4 Score | na | %b |

|---|---|---|

| Normal 0–2 | 3593 | 45.5 |

| Mild 3–5 | 2177 | 27.6 |

| Moderate 6–8 | 1221 | 15.5 |

| Severe 9–12 | 904 | 11.5 |

Abbreviation: PHQ-4, Patient Health Questionnaire-4.

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Personal Beliefs and Activities Regarding COVID-19 Prevention

The majority of people in the state consider COVID-19 to be quite serious, with more than 80% considering the disease either highly or very highly serious.

There was a moderate level of knowledge about COVID-19. About two-thirds (66.3%) knew that those aged 65 years and older, and those with a chronic disease are most at risk for severe disease, and 69.7% reported their own ability to recognize if a family member with COVID-19 needed to go to the hospital. Only about two-thirds (64.9%) reported knowing where to go for COVID-19 testing, and 38.7% would know how to provide care for someone in their family with COVID-19.

More than half of the respondents (57%) reported that they practice social distancing all of the time; when combined with usually practice social distancing, the percentage increased to 96.1%. Seventy-five percent reported they wear a face-covering “all of the time” when combined with “always,” and “usually,” the percentage increases to 97%. The majority (98%) of participants reported that their family members wash their hands the “same” or “more often” after COVID-19. Three-fourths (75.8%) reported that they have a working thermometer at home.

As shown in Table 8, 55.5% of the respondents reported there is a lack of space in their home for isolation, and 31.2% reported they would not have enough cleaning supplies. Slightly more than half (53.8%) reported that if they got COVID-19, there would be a family member available to care for them.

Table 8.

Factors for COVID-19 Household Preparedness and Response Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| na | %b | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude/Belief Question | ||

| Perceived Severity of COVID-19 | ||

| Not serious | 133 | 1.7 |

| Low level | 296 | 3.7 |

| Moderate level | 977 | 12.4 |

| High level | 2362 | 29.9 |

| Very high level | 4146 | 52.4 |

| Knowledge Questions | ||

| Know vulnerable populations (eg, older persons or those with chronic disease) | 5259 | 66.4 |

| Know where to go for COVID-19 testing | 5126 | 64.8 |

| Know how to provide medical care for someone at home with COVID-19 | 3061 | 38.7 |

| Able to recognize when a family member with COVID-19 would need to go to the hospital | 5466 | 69.4 |

| Behaviors Questions | ||

| “Usually” or “Always” practice social distancing by staying at least 6 feet away from others when not at home | 7598 | 96.1 |

| “Usually” or “Always” wear a face-covering when outside of your home | 7685 | 97.2 |

| Family members wash hands the “same frequency” or “more frequently” since COVID-19 | 7889 | 99.8 |

| Have a thermometer that works at home | 5997 | 75.8 |

| Resources Questions | ||

| Problems would face if someone lived with had COVID-19 | ||

| Lack of space for isolation | 4388 | 55.6 |

| No face mask | 193 | 2.4 |

| No hand sanitizer | 449 | 5.7 |

| Not enough cleaning supplies | 2458 | 31.2 |

| Have someone be available to care for you if you got COVID-19 | 4249 | 53.8 |

Abbreviation: COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019.

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Overall Household Preparedness for COVID-19

To assess overall household preparedness for COVID-19, scores were computed for each factor by assigning points for each level of preparedness within each factor: attitude/belief, knowledge, behaviors, and resources. Results revealed a high level of positive attitude/belief regarding the seriousness of COVID-19 and compliance with preventive behaviors, a moderate level of knowledge about the disease and how to care for someone with COVID-19, and a low to moderate level of availability of resources (Table 9).

Table 9.

Overall Household Preparedness for COVID-19 Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| na | %b | |

|---|---|---|

| Attitude/Belief – Perceived Severity of COVID-19 (1 question) | ||

| Low (none–low) | 429 | 5.4 |

| Moderate (moderate) | 977 | 12.4 |

| High level (high–very high) | 6508 | 82.2 |

| Knowledge (4 questions) | ||

| Low level of knowledge (0–2) | 1944 | 24.5 |

| Moderate level of knowledge (3) | 4391 | 55.4 |

| High level of knowledge (4) | 1592 | 20.1 |

| Behaviors – Compliance With Measures (4 questions) | ||

| Low level of compliance (0–1) | 28 | 0.4 |

| Moderate level of compliance (2–3) | 2220 | 28.0 |

| High level of compliance (4) | 5669 | 71.6 |

| Resources Needed (6 questions) | ||

| None (0) | 1783 | 22.5 |

| Low level of needs (1) | 2479 | 31.3 |

| Mod level of needs (2–3) | 3093 | 39.0 |

| High level of needs (4–6) | 570 | 7.2 |

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Best Source of Accurate Information

While many sources of information were reported to be used, most respondents across Hawai‘i reported using the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) website, followed by the Hawai‘i State Department of Health website and television news for reliable information regarding COVID-19 (Table 10).

Table 10.

Sources of Information About COVID-19 Used by Community Members Among All Hawai‘i Respondents (N=7927)

| Source of Information about COVID-19 | na | %b |

|---|---|---|

| Church leader | 35 | 0.5 |

| Community leader | 127 | 1.6 |

| Local community organization | 95 | 1.2 |

| Department of Health website | 1496 | 19.1 |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website | 4116 | 52.4 |

| Television news reports | 907 | 11.6 |

| Other source | 1073 | 13.7 |

Totals may not equal to 7927 due to unanswered/missing data.

Percentages may not equal 100% due to unanswered/missing data.

Discussion

Key findings from the ICIHSW assessment survey were used to establish recommendations by the CCO Unit in collaboration with community partners to address the impact of COVID-19 and mitigate the response strategies to serve the health and welfare of Hawai‘i's population. Community partners distributed the survey results to constituent groups and worked together to identify recommendations to best serve community health needs focusing on vulnerable populations and health disparities.

The results reported here are aggregate statewide data and provide an overall understanding of the impact of COVID-19 and its burden on the people of Hawai‘i. Specific data for the counties of Honolulu, Kaua‘i, Maui, Hawai‘i and identified vulnerable groups of Filipino, NH, and PI are presented separately.15–21

Demographics

Overall, the response rate of the ICIHSW assessment survey aligned with the state's demographics. Self-reported gender was the only category that had a disproportionate response rate from female participants, as the US Census reports that the gender breakdown in Hawai‘i is equal between men and women.13 The total participants from each of the counties were similar to proportions reported by the US Census Bureau, with a slightly higher response rate (a 6.6% increase) from City and County of Honolulu and slightly lower response rates from the counties of Hawai‘i and Maui.22

Household Profile

The median household income reported by respondents in the state of Hawai‘i was among the top fifth median income bracket in the nation due to Hawaii's exceptionally high cost of living. The estimated Asset Limited, Income Constrained, Employed (ALICE) Survival Budget, defined as the minimal total cost for a family of 4 to survive, is $90 828.23 According to the ALICE report, 42% of the Hawai‘i state population struggle with their household budget, and 9% of this group live under the poverty level. PIs have both the highest unemployment rate and the highest number of households living in poverty.24 NH, PI, and Filipino participants had the lowest incomes and the most increased employment risks due to COVID-19. These groups, therefore, have both higher socioeconomic disparities and chronic disease burdens which make it even more difficult to weather the COVID-19 pandemic.

Digital Connectivity

While most of the state's population reported having access to the internet, access does not necessarily equate with equity. The digital divide still exists in Hawai‘i, where underserved areas, economically disadvantaged, and homeless households have the lowest internet access speeds and availability. This exacerbates technological challenges related to COVID-19. Technological inequities become apparent with limited internet access and devices that allow for enrolling or participating in COVID-19-related health, social, and economic services offered online or remotely. This challenge carries over to disadvantages related to education as schools and colleges must use distance learning or hybrid formats.25,26

To address the technological challenges in the short term, the CCO Unit identified possibilities where internet access could be more readily available statewide. These possibilities included facilitating the use of public-based libraries for public internet access and providing computers and internet connectivity to churches and congregations that serve disadvantaged populations. Medium- and long-term goals include developing policies and infrastructure to meet the digital needs of those without access.

Housing

The percentage of participants that reported living in a home or condominium that they own or rent (at the time of the survey) dropped by 15% when asked if they expected to be in the same housing situation in 3 months. This percentage is expected to increase with the expiration of the Order under Section 261 of the Public Health Service Act to halt any evictions.27 Preparations must continue to assure housing stability for the poor and middle-income families across the state.

CCO Unit community members provided recommendations to enhance access to stable housing. These included providing readily available information on mediation and mortgage counseling programs that could extend the timeframe for renters and homeowners to negotiate terms with landlords and lenders. Another recommendation was to provide education on resources to mitigate unlawful evictions or other similar violations to address immediate needs. Additionally, leveraging federal and state resources available for housing placement and rapid rehousing, including efforts such as the City and County of Honolulu's new Landlord Engagement Program (LEP), was proposed.

Daily Essentials

When asked about the ability to pay for daily essentials, the percentage that expected to have difficulty paying for such in 3 months almost doubled in all categories. This data illustrates the progressive financial toll that the pandemic was having on the state population, especially among the vulnerable groups. Not surprisingly, PI, NH, and Filipino participants reported higher expectations of financial hardships than other races/ethnicities and reported higher percentages of a lack of resources than White and Asian families. This prediction by respondents has proven to be correct. As of March 3, 2021, the Hawai‘i Foodbank reported unprecedented challenges with providing food to those affected by the pandemic. More than 250 000 residents in the state, and 1 out of every 4 children are struggling with hunger.28 Proactive programming must be kept in place to ensure that the most vulnerable groups in the state have access to the basic daily essentials for living, including housing, food, communication, transportation, and health care. On July 16, 2021, the Hawai‘i Department of Education announced that all public school students will receive free meals through the school year 2021–22.29

Attempt at Applying for Benefits

Most of the participants were able to apply for finance, food, or health benefits. However, those who did encounter problems with applying reported the most common reasons were the inability to complete the form or did not have all of the necessary documents. Several participants reported they could not get through on the telephone. Work must continue to assure that applications are simplified, and required documentation kept to a minimum and streamlined. Telephone assistance centers must increase capacity or perhaps work with local grassroots community organizations to reach vulnerable groups.

Mental Health

The COVID-19 pandemic caused stress and anxiety for many. Stress and anxiety were influenced by many factors that likely included social support, financial situation, and the communities in which one resides. Approximately half of the ICIHSW assessment survey respondents reported being bothered by feelings of nervousness, worry, having little pleasure, or feeling down at least several days over the past 2 weeks. These feelings may have been exacerbated by family financial challenges, coupled with the heavy burden of underlying medical conditions and chronic diseases that increase the risk for severe COVID illness and uncertainty of the future. In Hawai‘i, obesity, asthma, and diabetes, disproportionately affect NH, PI, and Filipino populations.

To help mitigate the worry and stress caused by COVID-19, Aloha United Way, partnering with the Hawai‘i State Department of Health, initiated the telephone call number 211 for any questions or concerns related to COVID-19.20 This service included round-the-clock assistance and advice on various areas, such as access to food, shelter, financial help, child care, and care for older persons. However, only 4% of ICIHSW participants reported ever having called 211 for social service assistance. The reasons for the relatively low utilization of this service should be further explored. Perhaps a different approach to link people to services needs to be considered (e.g., community workers, grassroots organizations). To address issues related to pandemic-fatigue, anxiety, depression, suicide, substance abuse, and interpersonal violence, the CCO Unit community partners recommended funding, developing, and promoting cultural and community-based mental health activities and plans. These actions included addressing stigma and providing culturally appropriate, COVID-19-related health care delivery. Additionally, the CCO Unit community partners proposed programs and legislative actions to address barriers to health care access and raise awareness to advance health equity. It was noted that policies likely to affect health inequalities need to be evaluated and delivered through effective involvement of state and local government, private sectors, individuals, and communities.

Personal Beliefs and Activities Regarding COVID-19 Prevention

Hawai‘i is a geographically isolated island state that is culturally diverse and where family and social ties are strong. Combined with the high cost of living, the state leads the nation in the number of households with 3 or more generations (1 in 5 households), highest in Filipino, NH, and PI ethnic groups. As household size increased past 9 individuals, the risk of contracting COVID-19 increased among household members.9 More than half of the respondents stated there was a lack of space in their home to socially isolate. All groups across the state had similar emotional responses to COVID-19. This finding illustrates the widespread impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the state's population as a whole. Continued awareness and information campaigns are essential to educating the public, using diverse methods, such as social media and churches, to increase awareness of disease prevention and care in a culturally sensitive manner.

Recommendations on increasing awareness of COVID-19 beliefs include community outreach with the collaboration of the Hawai‘i State Department of Health to explore vehicles of communication for those that do not have access to a cell phone or internet. Additional work is needed that incorporates brainstorming with community leaders (eg, pastors, public figures) and universities to develop materials and resources for safe cultural practices. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a widespread impact on individuals, households, and communities across the state. Community engagement is essential to monitor the situation and develop and implement strategies to mitigate the situation.

Limitations

A convenience-sampling frame was used; all responders were self-selected and there is no way to determine an actual response rate. Therefore, the report results must be viewed within the context of potential self-selection bias. In addition, while the survey was available in both paper form and online, the vast majority of respondents participated online. Thus, there is a chance that those with no access to the internet and hidden groups, such as the houseless, may not be adequately represented in the sample. In addition, all data were self-reported and not verified. However, there are consistent trends in responses across respondents from all of Hawai‘i counties, which lends credence to the findings. To mitigate some of these concerns, the community partners reviewed and corroborated the results.

Conclusion

Community stakeholders must be involved in creating solutions that effectively communicate and support COVID-19 prevention and care needs and address social determinants of health related to the pandemic. Our findings in this report are intended to provide a baseline to understand the impact, needs, and threats to the health and social welfare of individuals and their families across the state of Hawai‘i. Local stakeholders are encouraged to use this information to continue to develop priorities, strategies, and programs to address this pandemic and its impact.

PI, NH, and Filipino households will continue to experience greater financial burdens due to living expenses and employment risks heightened by the pandemic. State and federal government leaders should implement initiatives that support better health for our communities and promote equity in access to safe housing, food, support, mental health, technology, and education.

Increased knowledge may provide a source of comfort and power in dealing with COVID-19 uncertainty and decision-making and alleviate anxiety and stress caused by COVID-19. Effective messaging and community engagement must provide culturally relevant information to both the people of Hawai‘i and health care providers in various formats. Information areas may include COVID-19 prevention, disease detection, quarantine and isolation, training, capacity building, payment for community navigators, and assessments and recommendations to improve recovery and resiliency for those most affected by health disparities. The CCO Unit recommends that information dissemination should be carried out using varying communication methods, such as written text, radio, community meetings, news media, and social media. The role of community health workers who come from the communities most impacted should be expanded. Community health works can serve as navigators for vulnerable groups.

Lastly, results from the ICIHSW assessment survey demonstrated that health disparities exist across Hawai‘i. PI, NH, and Filipino groups report greater burden in almost all areas surveyed: household profile, health and well-being, living expenses, and COVID-19 prevention. Elected and community leaders may use this data to initiate programmatic efforts that are focused on support for these vulnerable populations, as well as the community at large. This audience includes planning and supporting communities across the state of Hawai‘i as the response to the COVID-19 pandemic continues.

Acknowledgments

The entire team wishes to thank the community partners of the HI-EMA CCO Unit (Appendix A).

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CCO Unit

Community Care Outreach Unit

- COVID-19

Coronavirus disease 2019

- HIDOH

Hawai‘i State Department of Health

- HI-EMA

Hawai‘i Emergency Management Agency

- ICIHSW

Impact of COVID-19 on Individual's Health and Social Welfare

- ICS

incident command system

- LEP

limited English proficiency

- NH

Native Hawaiian

- PHQ-4

Patient Health Questionnaire-4

- PI

Pacific Islander

- PPE

personal protective equipment

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

Appendix A. Community Partner Recognition

For questions please contact:

Kristine Qureshi (CCO Unit Lead) kqureshi@hawaii.edu or

Lee Buenconsejo-Lum (CCO Unit co-Lead) lbuencon@hawaii.edu

Project participants included:

-

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

Kristine Qureshi, PhD, RN, FAAN, PHNA-BC, CEN (CCO Unit lead)

Lee Buenconsejo-Lum, MD, FAAFP (CCO Unit co-lead)

Neal A. Palafox, MD, MPH (CCO Unit senior advisor)

Robin Arndt, MSW, LSW (CCO Unit team member)

Tetine Sentell, PhD (CCO Unit team member)

Gary Glauberman (CCO Unit team member)

Qi Zi, MPH (UHM Nursing Graduate Assistant, CCO Unit Statistical Support)

-

Community partners

Sheri Daniels, Ed.D – Native Hawaiian community - Papa Ola Lokahi

Barbara Tom, RN – Pacific Island community - Nations of Micronesia

Jocelyn Howard, MSW – Native Hawaiian & Pacific Island communities. - We are Oceania

Mele Look, MBA – Native Hawaiian community - UHM JABSOM

Annilet Pingul, RN, BS – Filipino community

Isabela Silk – RMI and the Pacific Island community – Consul General, Consulate of the RMI

Kenson Alik, BS, Med – Marshallese community

-

State organization leaders

Allison Mikuni – Rural health (HIDOH Office of Primary Care and Rural Health)

Emma Grochowsky-- Homeless Community (HI State Office of Homelessness)

Christine Chaplin – (DBEDT Statewide GIS Program)

Fenix Grange, PhD – (HIDOH Emergency Operations)

Glen Wasserman, MD, MPH – (HIDOH Communicable Disease and Public Health Nsg.)

Joan Takamori, RN, MS – (HIDOH Public Health Nursing Branch)

Gloria Fernandez, RN, MS, DNP – (HIDOH Public Health Nursing Branch)

Antonette Torres, RN, MS – (HIDOH Public Health Nursing Branch)

Jasmine Staup, RN, MS – (HIDOH Public Health Nursing Branch)

Blanca Baron – (HIDOH Kaua’i County District Heath Office)

Lori Ching, NN, BSN – (HIDOH Hansen’s Disease Program)

Christopher Johnson – (HIDOH Community Outreach and Education)

Appendix B. Impact of COVID-19 on Individual’s Health and Social Welfare Surveys Questions

-

1.

Gender: Male ____; Female ____; Other: _____

-

2.

ZIP Code where you live ____________

-

3.

Age: _____

-

4.

Race/Ethnicity Group(s) that you most closely identify with (check all that apply): Caucasian___; Filipino___; Japanese ____; Chinese____; Other Asian (please specify)_____ Native Hawaiian___; Pacific Islander (please specify) ______________; African American ____; Hispanic ____; Other: __________

-

5.

If you checked more than one race or ethnicity… which Race/Ethnicity Group do you most closely identify with (check ONE): Caucasian___; Filipino___; Japanese ____; Chinese____; Other Asian (please specify) ____; Native Hawaiian____; Pacific Islander (please specify) ______________; African American ____; Hispanic ____; Other: _______.

-

6.

How many people do you live with? ______; How many people in your home are older than 64 years? _______; and how many are under 18 years? ______

-

7.

Today, do you have access to the internet: At home ____; At work: ____; Other: ___ No access to the internet _____

-

8.

Do you have a cell phone that works? Yes ___; No ____;

-

9.

Estimate of the total income of your household during 2019? Less than $40,000____; $41,000 - $75,000 ___; $76,000-$125,000 ___; $126,000+ ___; Choose not to answer___

-

10.

Has COVID 19 made your family income go down? No ___; Yes a little ___; Yes a moderate amount ___; Yes a large amount ____

-

11.

Has COVID -19 affected the employment or work hours of any family members in your home? No effect ___; Increased work hours ___; Reduced work hours ___; Lost job___

-

12.

Does anyone you live with have any of the following chronic diseases? (check all that apply): Diabetes ___; Heart disease ___; Asthma ___; Lung disease ___; Kidney disease ___; Mental health illness___; Obesity ____; Cancer ____

-

13.

Where did you usually go for health care? Family doctor office ____; Community Health Center/or Community Clinic ____; Hospital based clinic ____; Emergency Room ____; Have no usual source of healthcare_____; Other (please specify):________________

-

14.Please tell us about how you are feeling: Over the past two weeks (14 Days) how often have you been bothered by the following problems:

Not at all Several days More than half Nearly every day Feel nervous, anxious or on edge Not able to stop or control worrying Little interest or pleasure in doing things Feel down, depressed, or hopeless -

15.Housing: Please tell us about your housing situation today and in the next three months

TODAY where do you live? In 3 months where will you likely live? A home, condo or apartment you OWN A home, condo or apartment you OWN A home, condo or apartment you RENT A home, condo or apartment you RENT Houseless, live with others you know, in their home or apartment Houseless, live with others you know in their home or apartment Houseless, live in a public shelter Houseless, live in a public shelter Houseless, live in a tent, car, or outside Houseless, live in a tent, car, or outside -

16.Money for essentials TODAY & in 3 months. Please tell us if you think you will have problems paying for any of these things today and in the future?

TODAY Three months from now Food Food Rent or mortgage Rent or mortgage Auto expenses (e.g., gas, insurance, car payments) Auto expenses (e.g., gas, insurance, car payments) Public transportation Public transportation Medicines Medicines Utility bills (e.g., electric, water) Utility bills (e.g., electric, water) Cell phone bill, internet, cable bill Cell phone, internet, cable bill Child care/ elder care Child care/ elder care Healthcare Healthcare Other debts Other debts -

17.

Are any people in your household (including yourself) attending school this coming fall? No____; Yes____

-

17 a.

If yes which categories: Preschool ____; K-12 ____; College ____

-

17 b.

What challenges do you expect to experience during the fall related to school for your family members or yourself? None ___; Language barrier____; Lack of face covering ___; Lack of funds to buy school supplies ___; Lack of access to the internet ___; Lack of computer; ___Other: ___________________

-

17 a.

-

18.

What language is mostly spoken in your home? _________________

-

19.

Have you encountered translation needs that have not been met? No __; Yes __; N/A___

-

19 a.

If yes, which type of agencies: Health ___; Education___; Social service___; Other: _______________

-

19 a.

-

20.

In the past 6 months, have you ever called 211 for assistance? No ___ Yes ___

-

20 a.

If yes, please check all that apply

You received the assistance you needed ___

You did NOT receive the assistance you needed ___

You were only directed to an internet site ___

Comments: ____________________________________

-

20 a.

-

21.Have you tried to apply for any of the benefits or services listed below? For any that you have tried to apply for, please tell us if you could you complete the application, and if not, the reason why.

Service /Benefit Applied for? If YES, was the applicationcompleted? If NO, you could not complete the application, checkall of the reasons why. Prequalification for financial hardship relief Yes No Yes No __No internet access

__Could not figure out how to complete

__Did not have all of the documents

__Did not understand questions in English

__Tried to call on phone for help but could not get thruRental assistance Yes No Yes No __No internet access

__Could not figure out how to complete

__Did not have all of the documents

__Did not understand questions in English

__Tried to call on phone for help but could not get thruFood stamps Yes No Yes No __No internet access

__Could not figure out how to complete

__Did not have all of the documents

__Did not understand questions in English

__Tried to call on phone for help but could not get thruHealth insurance Yes No Yes No __No internet access

__Could not figure out how to complete

__Did not have all of the documents

__Did not understand questions in English

__Tried to call on phone for help but could not get thruHealthcare benefits (e.g., Quest or WIC) Yes No Yes No __No internet access

__Could not figure out how to complete

__Did not have all of the documents

__Did not understand questions in English

__Tried to call on phone for help but could not get thru

PLEASE TELL US ABOUT YOUR BELIEFS & ACTIVITIES WITH REGARDS TO COVID-19

-

22.

Compared to other challenges that you face in life every day, how serious do think COVID-19 is? Not at all ___; low level__; moderate level __; high level __; very high level ___

-

23.

Which of these groups do you think are more likely to get very sick or die from COVID-19? (check all that you think): Elderly___; Chronic disease___; Women ___; Children ___

-

24.

Do you know where to go for COVID-19 testing if needed? Yes ___; No ___; Not sure ___

-

25.

How often do you practice social distancing by staying at least 6 feet away for others when not at home? Never___; Sometimes ___; Usually ___; Always ___

-

26.

Do you wear a face covering when outside of your home? Never___; Sometimes ___; Most times ___; Always ___

-

27.

Since COVID-19, is the frequency your family members wash their hands (or use hand sanitizer): the same__ ; more often ___; less often ___.

-

28.

Today, do you have a thermometer that works in your home? Yes ___; No___; Not sure __

-

29.

Would you know how to provide medical care for someone in your home with COVID-19? Yes___; No___; Not sure___

-

30.

If someone you live with had COVID-19, what problems do you think would you have for caring for them? (check all that apply) Lack of space for isolation ___; No face masks____; No hand sanitizer___; No thermometer___; Not enough cleaning supplies ____

-

31.

Do you think that you would be able to recognize when a family member with COVID-19 would need to go to the hospital? Yes___; No ____; Not sure ____

-

32.

If you got COVID-19 would someone in your family be available to care for you? Yes__; No__; Not sure__

-

33.

What do you think is the best source for accurate information about COVID-19: Church leader ____; Community leader ___; Local community organization___ ; Department of Health website ___; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website___; TV News Reports___; Other source (please specify): ____;

-

34.

Do you have any other COVID-19 issues you want to tell us about or suggestions about how to make things better for COVID-19 response? _____________________

-

35.

Please tell us: howdid you receive this survey? Email ___; Website ___; Social media ___; Mail ___; Paper copy (please indicate location: ____________); Other: _______

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors identify a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.CDC COVID data tracker US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available from: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days. Updated January 26, 2021. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- 2.Cuellar NG, Aquino E, Dawson MA, et al. Culturally congruent health care of COVID-19 in minorities in the United States: a clinical practice paper from the national coalition of ethnic minority nurse associations. J Transcult Nurs. 2020;31((5)):434–443. doi: 10.1177/1043659620941578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chowkwanyun M, Reed AL., Jr Racial health disparities and Covid-19 — caution and context. NEJM. 2020;383((3)):201–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2012910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hawai‘i COVID-19 data State of Hawai‘i – Department of Health Disease Outbreak Control Division, COVID-19 website. Available from: https://health.hawaii.gov/coronavirusdisease2019/what-you-should-know/current-situation-in-hawaii. Updated December 28, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2021.

- 5.Vaughn K, Fitisemanu J, Hafoka I, Folau K. Unmasking the essential realities of COVID-19: the Pasifika community in the Salt Lake Valley. Oceania. 2020;90:60–67. doi: 10.1002/ocea.5267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaholokula JK, Samoa RA, Miyamoto RES, Palafox N, Daniels S-A. COVID-19 special column: COVID-19 hits Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander communities the hardest. Hawai’i J Health Soc Welf. 2020;79((5)):144–146. Accessed December 23, 2020. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang D, Gee GC, Bahiru E, Yang EH, Hsu JJ. Asian-Americans and Pacific Islanders in COVID-19: emerging disparities amid discrimination. JGIM. 2020;35((12)):3685–3688. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-06264-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oliveira CM. Hawaii's nursing workforce supply 2019. Hawai‘i State Center for Nursing. 2019. Available from: https://www.hawaiicenterfornursing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/2019-Nursing-Workforce-Supply-Report-vFinal.pdf. Accessed January 5, 2021.

- 9.Family Ties: Are Hawaii's multigenerational households more at risk? Hawaii Data Collaborative website. Available from: https://www.hawaiidata.org/ideas/2020/5/21/are-hawaiis-multigenerational-households-more-at-risk. Published May 26, 2020. Accessed January 4, 2021.

- 10.State of Hawaii, Hawaii Emergency Management Agency Available from: https://dod.hawaii.gov/hiema/. Accessed February 10, 2021.

- 11.Sentell T, Choi SY, Maldonado F, et al. Hawai‘i community based organizational capacity and needs for COVID-19 response and recovery: snapshot from spring 2020. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50((6)):613–621. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.50.6.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hawaii Population Characteristics 2019. Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism Census website. Available from: https://census.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Hawaii-Population-Characteristics-2019.pdf. Published June 25, 2020. Accessed January 2, 2021.

- 14.Aloha United Way 211. Aloha United Way website. Available from: https://www.auw211.org/s/. Accessed January 12, 2021.

- 15.Qureshi K, Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Palafox NA, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare in the City and County of Honolulu, Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Qureshi K, Berreman J, Arndt R, Palafox NA, Buenconsejo-Lum LE. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare in the County of Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Qureshi K, Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Palafox NA, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare in the County of Maui, Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Qureshi K, Buenconsejo-Lum LE, Palafox NA, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare in the County of Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Palafox NA, Alik K, Howard J, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare of the Pacific Islander population in Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Palakiko D, Daniels S, Birnie KK, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare of the Native Hawaiian population in Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Dela Cruz MR, Glauberman G, Buenconsejo-Lum L, et al. A report on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the health and social welfare of the Filipino population in Hawai‘i. In press. Hawai‘i J Health Soc Welf. 2021. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.County population facts for the state of Hawaii: July 1, 2010, through July 1, 2019. Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism Census website. Available from: https://census.hawaii.gov/home/data-products/. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed January 2, 2021.

- 23.ALICE in Hawaii: a financial hardship study. United for ALICE website. https://www.auw.org/alice-study-financial-hardship-hawaii. Published 2020. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 24.Demographic, social, economic, and housing characteristics for selected race groups in Hawai‘i. Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism Census website. Available from: https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/economic/reports/SelectedRacesCharacteristics_HawaiiReport.pdf. Published March 2018. Accessed January 2, 2021.

- 25.Hawaii broadband strategic plan. Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism Census website. Available from: https://broadband.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Hawaii-BB-Plan-2020-FINAL_10-23-20_v1.1.pdf. Published October 2020. Accessed January 2, 2021.

- 26.Lee S. Educators Worry about kids with no computers as online classes start. Honolulu Civil Beat website. Available from: https://www.civilbeat.org/2020/04/educators-worry-about-kidswith-no-computers-as-online-classes-kick-in/. Published April 5, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 27.Temporary halt in residential evictions to prevent the further spread of COVID-19. National Archives website. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/04/2020-19654/temporary-halt-in-residential-evictions-to-prevent-the-further-spread-of-covid-19. Published September 4, 2020. Accessed January 3, 2021.

- 28.COVID-19 recovery. Hawaii Food Bank website. Available from: https://hawaiifoodbank.org/covid-19/. Updated February 1, 2021. Accessed March 10, 2021.

- 29.All public school students to receive free meals throughout school year 2021-22. Hawai‘i Department of Education website. Available from: https://www.hawaiipublicschools.org/ConnectWithUs/MediaRoom/PressReleases/Pages/SY2021-Free-School-Meals.aspx. Published July 16, 2021. Accessed July 17, 2021.