Abstract

Anxiety disorders make up the most prevalent class of mental illnesses. Given the growing prevalence of anxiety in the United States and beyond, there is an urgent clinical need to develop nonpharmacologic treatments that effectively treat and reduce its core symptoms (eg, worry). A leading theory posits that although worrying may be unpleasant, the immediate emotions that are avoided by concentrating on worry are often perceived as more aversive (eg, fear, anger, grief). From a mechanistic perspective, worry is thought to be learned and reinforced in a similar manner to other types of positively and negatively reinforced behaviors: habits. Mindfulness training, a practice that brings awareness to cognitive, affective, and physiological experiences, when delivered in-person via programs such as mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), has demonstrated effectiveness in reducing anxiety, but is difficult to scale in this manner. In this review, we explore novel approaches to using mindfulness training to specifically target the theoretical mechanisms underlying the perpetuation of anxiety (eg, worry as a habit), and the emergence of mobile health platforms (eg, digital therapeutics) as potential vehicles for remote delivery of treatment.

Keywords: anxiety, mindfulness, habit change, reinforcement learning, obesity, digital therapeutics, weight loss

Anxiety has shown significant increases since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Case Presentation

A 40-year-old White male with hypertension, steatohepatitis, obstructive sleep apnea, and a body mass index >40 kg/m2, presented to my office with the chief complaint of anxiety. He described sudden onset of racing heart, sweating, and shortness of breath that were triggered by thoughts that arose in his mind while driving on the highway (eg, “Oh, no, I’m in a speeding bullet, I might kill someone.”). He had never been in a car accident, but these episodes had resulted in his avoidance of driving on the highway, and minimal use of local roadways.

On taking a full history, this patient met criteria for both panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). He was not interested in being prescribed a medication as the first-line treatment for his anxiety.

Anxiety: The Growing Epidemic

Over 40 million adults in the United States are affected by anxiety disorders making these the most common mental illnesses in the country. 1 GAD, which generally begins in adulthood, has a 12-month prevalence in adults of 1.8% (lifetime = 3.7%), 2 and has led to a significant economic burden of $46 billon in the United States due to significant work loss, social impairment, 3 morbidity, mortality, and other indirect costs. 4 Panic attack and panic disorder prevalence peak at 9.5% and 3.3% in people aged 30 to 39 and 40 to 49 years, respectively. 5 There are millions of undiagnosed Americans with subclinical anxiety symptoms 6 who fail to seek treatment or proper care due to stigma/shame, financial hardships, lack of awareness, avoiding medication, or lack of access to professional help. 7 This crisis also extends globally, which is estimated to affect 4% of the entire global population. 8

Anxiety has shown significant increases since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. The Census Bureau reported that US adults were more than 3 times as likely to screen positive for anxiety disorder in 2020 compared with 2019 (31% vs 8%); a US study in April 2020 showed a significant 250% increase in severe psychological distress relative to previous years, 9 and a cross-sectional survey of people in China from February 2020 found the prevalence of GAD to be 35.1%. 10 A meta-analysis found an average anxiety prevalence of 32% during the pandemic (17 studies, n = 63 439), 11 while a retrospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with COVID-19 between January and August, 2020 (n = 62 354) found that 1 in 5 patients with no psychiatric history received a new mental health diagnosis, with the greatest health risk being for anxiety disorders. 12 Thus, there is a significant clinical need to address anxiety, which is a public health epidemic that is rapidly growing, substantial, and difficult to treat.

Medication Options for Anxiety

Currently, first-line treatment for anxiety is medication, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and/or benzodiazepines.13-15 Yet, these medications can lead to undesirable side effects. Benzodiazepines also bring potentially dangerous risks for tolerance and addiction (the UK has updated its NICE (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) guidelines to state that benzodiazepines “should not be used routinely to treat anxiety disorders”). 16 Additionally, a recent review showed several limitations of SSRIs, including delayed patient responses and adverse side effects (eg, gastrointestinal, sexual).16,17 The number needed to treat (NNT) for SSRIs is 5.15—one needs to treat more than 5 individuals to see a significant response in 1 individual. 14

Cognitive and Other Strategies for Anxiety

Given the relatively high NNT and medication limitations, there are currently millions of Americans who prefer alternative, nonpharmacological treatments for anxiety. Cognitive treatments (eg, cognitive behavioral therapy, CBT) for anxiety are popular alternative treatments for individuals with anxiety, yielding a medium-to-large effect size.18,19 In conventional cognitive frameworks, anxiety is conceptualized as an overestimation of danger, and an underestimation of one’s ability to cope with it. 20 Thus, cognitive therapies aim to interrupt the cycle of worry by replacing maladaptive cognitions with more constructive ones. Yet, these cognitive approaches are difficult to deliver across a wide population due to the limited availability of trained individuals, time requirements, and associated costs. Virtual reality delivery of cognitive and exposure treatments has a growing evidence base, yet is largely used in combination with in-person treatment (eg, CBT).21,22

Can Anxiety Be Reinforced Like Other Habits? The Worry-Driven Habit Loop

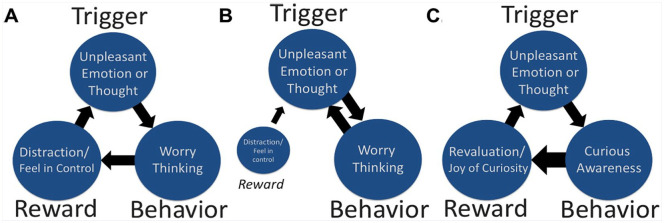

Much has been discovered over the past century about predisposing factors of anxiety as well as how anxiety disorders develop and are perpetuated. Worry is a habitual thought process that is mostly observed in individuals with GAD, but it is also central to other anxiety disorders and anxiety more broadly. 23 A common working definition of worry is “a chain of thoughts and images, negatively affect-laden, and relatively uncontrollable.” This represents an attempt to engage in mental problem solving on an issue with an uncertain outcome. 24 Research has suggested that although worrying may be unpleasant, the immediate emotions that are avoided by focusing on worry are often perceived as more aversive (eg, fear, anger, grief).25,26 In return, these aversive stimuli trigger worry as an avoidant behavior, which over time may be habitual. From a mechanistic perspective, worry is thought to be learned and reinforced in a similar manner to other types of operantly conditioned behaviors. 27 Therefore, with cycles of reinforcement learning, individuals learn a maladaptive, distracting thinking style that uses worry to focus on the future rather than the present. Consequently, worry not only lies at the core of GAD but may also directly perpetuate anxiety “habit loops” (see Figure 1). 28

Figure 1.

(A) Development of a “habit loop” via positive and negative reinforcement. (B) Worry triggers itself when it feels less rewarding. (C) Through training curious awareness as a substitute behavior for worry, mindfulness updates the reward value of worrying and taps into the more rewarding aspect of curiosity itself. Copyright Judson Brewer 2020, reproduced with permission.

Reinforcement learning/operant conditioning (positive and negative reinforcement) requires three components: a trigger, a behavior, and a “reward” (Figure 1).29,30 As a coping mechanism triggered by emotional distress, worry may be reinforced in several ways. Davey et al 31 postulated that worry can contribute to problem solving. Others suggested it provides a feeling of control over a situation. 32 Thus, the “reward” that occurs when worrying feels helpful can lead to it being positively reinforced. More significantly, research shows that worry is triggered as an avoidance reaction to an emotional experience (as if it were threatening).33,34 In other words, worry is triggered as an emotional reaction to unpleasant emotions themselves. In Borkovec’s model, unpleasant emotions trigger worry as a behavioral response to turn away from these emotions, resulting in the “reward” of decreased distress.24,27 When worry is engaged as avoidance or a distraction for triggers such as negative thoughts and emotional states, the reduction in these can lead to worry becoming “a negatively reinforced avoidant behavior” (Figure 1A).35,36

Over time, this behavior becomes habitual, operating largely out of conscious control 37 and a habit loop is formed. Importantly, worry as an avoidance strategy comes with 2 critical caveats: (1) worry is unpleasant in itself and (2) worry thinking rarely solves the problems that triggered it. When the negative affective qualities of worry are strong enough, the prefrontal cortex “goes offline,” impeding higher-order prefrontal cortical function, such as problem solving.38,39 When worry becomes habitual, the negative reinforcement pathway can spiral out of control. Consequently, the felt negative emotional experience of worry increases to the level where it is no longer rewarding, thus becoming its own trigger for more worry (Figure 1B).

Reinforcement learning is driven by the reward value of one’s actions. For instance, if someone is habitually reacting to a trigger, they may not be aware of how rewarding that action is in the present moment; they are acting out a behavior whose value was determined in the past. Without updated information on how rewarding the behavior is right now, the behavior’s value remains the same. A simple analogy is storing money in a mattress for fifty years, going to the store, and realizing that it takes more money to buy goods today than it did decades ago (the value has changed).

Awareness is critical for updating the reward value of a mental or physical action: When one brings awareness to the action, one experiences the actual value of the behavior, which gets updated in one’s memory. In the same way, when one pays attention when getting caught up in a worry thought loop, the result of the behavior becomes clearer, leading to a natural neural depreciation of its reward value. This leads to the question, “How can awareness be trained in a clinical context?”

Mindfulness Training as a Next-Generation Treatment for Anxiety

Next-generation behavioral treatments, such as mindfulness training, have shown promise both in efficacy and cost (treatment is largely delivered in group format), with effect sizes rivaling gold standard treatments.40,41 Mindfulness, by definition, brings awareness to cognitive, affective, and physiological experiences in the present moment, on purpose and nonjudgmentally. 42 In other words, when someone is “being mindful,” the attitudinal quality of not judging and allowing their experience to unfold with curiosity helps them avoid being triggered by either positive or negative affective states, to act out habitual behavior. 43 Individuals learn to pay attention, pause, and “be with” their urges to habitually react, instead of acting on them. Examples include mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT), which assist individuals with stress, anxiety, depression, and pain.44-46 Many current cognitive techniques encourage individuals to distract themselves or substitute another behavior when triggered. In contrast, mindfulness trains people in attention and body awareness, which can lead to a change in self-perspective. 47

Additionally, as one deepens their mindfulness practice, the “rewards” of curious awareness, even of unpleasant emotional states, become clearer as curiosity itself feels better than anxiety or worry thinking (Figure 1C). Thus, mindfulness training may act through reinforcement learning itself to dismantle anxiety habit loops, by helping individuals see the lack of reward in worrying and substituting the more rewarding mental behavior of curious awareness.43,48-52 An example of someone substituting curiosity for anxiety using an app-delivered mindfulness training program is below:

When I first started the program, I didn’t quite buy into the benefits of curiosity. Today I felt a wave of panic and instead of immediate dread or fear, my automatic response was, “Hmm, that’s interesting.” That took the wind right out of its sails! I wasn’t just saying it was interesting, I actually felt it. I was so thrilled.—Unwinding Anxiety app user

Consequently, with mindfulness training, individuals may be able to move away from maladaptive habitual thought processes, such as worry as a distraction strategy. Particularly, mindfulness training has been shown to be effective in breaking the habitual cycle of worry and other symptoms that perpetuates GAD and other anxiety disorders40,41,53-55

A New Way to Deliver Next-Wave Treatments for Anxiety: Digital Therapeutics

While in-person mindfulness training has shown some of its most robust effects in reducing anxiety,41,55-57 there are current challenges surrounding fidelity, competency, and scalability of these types of in-person-delivered treatments. 44 Digital therapies, such as app-based programs, may help bridge these gaps.

Literally hundreds of electronic health (eHealth) platforms exist for anxiety relief (i.e., positive affirmation, hypnosis, CBT, meditation). The most commonly used mindfulness apps are Headspace and Calm, which offer general guided meditations to help people learn to meditate. However, there is a paucity of clinical trial evidence of efficacy. The Anxiety and Depression Association of America (ADAA) has reviewed 19 apps on its website. 58 Seven of these apps have registered clinical trials, yet only 1 has reported results on Clinicaltrials.gov (nonrandomized trial of 10 adolescents), and none have published studies related to anxiety. A 2017 meta-analysis of depression and anxiety summed up the entire eHealth field as follows: “there is inadequate evidence to suggest that eHealth interventions have an effect on long-term outcomes (especially for anxiety).” 59

Recently, in a collaboration between Brown University’s School of Public Health and MindSciences Inc (which merged with Sharecare Inc in 2020), we developed a mobile health (mHealth) digital therapeutic (Unwinding Anxiety) with the aim of delivering mindfulness training to target the underlying behavioral reinforcement learning pathways by which anxiety develops and is perpetuated in individuals with anxiety—emotional reactivity and worry-based habit loops. In 2020, we published an open-label trial of the app-based mindfulness training program in which anxious physicians reported a 57% reduction in Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scores after 3 months of using the program. 60 We have recently completed a National Institutes of Health–funded randomized controlled trial of the digital therapeutic program in individuals with moderate to severe anxiety (baseline GAD-7 scores ≥10), which demonstrated preliminary efficacy at a 2-month follow-up: Treatment as usual showed a 14% reduction in GAD-7 scores while the addition of app-based mindfulness training demonstrated a 67% reduction in GAD-7 scores (P < .001). 61 The number needed to treat in this clinical trial was 1.6.

Mechanistic analysis from this randomized controlled trial suggested that increases in subscales of mindfulness (nonreactivity) mediated a reduction in worry (measured by the Penn State Worry Questionnaire, P = .02), and further, that a reduction in worry mediated decreases in anxiety (GAD-7 scores, P = .03).

Taken together, these results show preliminary promise for taking a mechanistic approach to targeting anxiety: treating worry as a habitual mental behavior may specifically help unwind anxiety through awareness-driven increases in non-reactivity. In other words, the hallmark of mindfulness—being able to change one’s relationship with one’s emotions through a curious observational awareness—may help individuals step out of the habit of worrying, resulting in the nonperpetuation of anxiety and future worry.

While these results require replication, studies of mechanistically informed digital therapeutics are currently being conducted with regard to targeting worry as a driver of sleep disturbances. 62 Additionally, future studies are needed to determine precise mechanisms of action and efficacy of a broad range of CBT and other theory-derived digital therapeutics.

Case Conclusion

In our first clinic visit, I mapped out my patient’s habit loops related to panic with him. Trigger: thoughts of getting in a car accident. Behavior: avoid driving. Reward: reduction of panic attacks. I gave him a coupon code for free access to the mindfulness training app my lab had studied with the instructions to map out his habit loops before the next visit. At his next clinic visit 2 weeks later, he described how he had mapped out a number of habit loops, including one in which anxiety triggered stress eating. Using mindful awareness, he had realized that stress eating was not rewarding and had largely stopped this behavior (resulting in a 14-pound weight loss). Over the next year, his anxiety returned to normal (and he started working as an Uber driver). He lost 100+ pounds and his blood pressure and liver enzymes returned to normal levels.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: Dr Brewer owns stock in and serves as a paid consultant for Sharecare Inc the company that owns the mindfulness app described in this article. This financial interest has been disclosed to and is being managed by Brown University, in accordance with its Conflict of Interest and Conflict of Commitment policies. All other authors report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Contributor Information

Judson A. Brewer, Mindfulness Center, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island; Department of Psychiatry, Warren Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island.

Alexandra Roy, Mindfulness Center, Brown University School of Public Health, Providence, Rhode Island.

References

- 1.Anxiety and Depression Association of America. Managing stress and anxiety. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://adaa.org/living-with-anxiety/managing-anxiety

- 2.Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:465-475. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ormel J, VonKorff M, Ustun TB, Pini S, Korten A, Oldehinkel T. Common mental disorders and disability across cultures: results from the WHO Collaborative Study on Psychological Problems in General Health Care. JAMA. 1994;272:1741-1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Devane C, Chiao E, Franklin M, Kruep EJ. Anxiety disorders in the 21st century: status, challenges, opportunities, and comorbidity with depression. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(12 suppl):S344-S353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olaya B, Moneta MV, Miret M, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Haro JM. Epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder and the moderating role of age: results from a population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2018;241:627-633. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carter RM, Wittchen HU, Pfister H, Kessler RC. One-year prevalence of subthreshold and threshold DSM-IV generalized anxiety disorder in a nationally representative sample. Depress Anxiety. 2001;13:78-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weissman J, Russell D, Jay M, Beasley JM, Malaspina D, Pegus C. Disparities in health care utilization and functional limitations among adults with serious psychological distress, 2006–2014. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:653-659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritchie H, Roser M. Mental health. Published April 2018. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health

- 9.McGinty EE, Presskreischer R, Han H, Barry CL. Psychological distress and loneliness reported by US adults in 2018 and April 2020. JAMA. 2020;324:93-94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Y, Zhao N. Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 epidemic in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;8:130-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoffman EJ, Mathew SJ. Anxiety disorders: a comprehensive review of pharmacotherapies. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75:248-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kapczinski FP, Lima MS, Souza JS, Schmitt R. Antidepressants for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Cochrane Database Syste Rev. 2003;(2):CD003592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute of Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management. Published January 26, 2011. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113 [PubMed]

- 16.Katzman MA. Current considerations in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. CNS Drugs. 2009;23:103-120. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200923020-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bandelow B, Reitt M, Rover C, Michaelis S, Gorlich Y, Wedekind D. Efficacy of treatments for anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:183-192. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Olatunji BO, Cisler JM, Deacon BJ. Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: a review of meta-analytic findings. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010;33:557-577. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.04.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:427-440. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beck A, Emery G, Greenberg R. Anxiety Disorders and Phobias: A Cognitive Approach. Basic Books; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bouchard S, Dumoulin S, Robillard G, et al. Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: a three-arm randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;210:276-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maples-Keller JL, Bunnell BE, Kim SJ, Rothbaum BO. The use of virtual reality technology in the treatment of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2017;25:103-113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borkovec TD, Robinson E, Pruzinsky T, DePree JA. Preliminary exploration of worry: some characteristics and processes. Behav Res Ther. 1983;21:9-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hong RY. Worry and rumination: differential associations with anxious and depressive symptoms and coping behavior. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:277-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Borkovec TD, Roemer L. Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1995;26:25-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borkovec T, Ray WJ, Stober J. Worry: a cognitive phenomenon intimately linked to affective, physiological, and interpersonal behavioral processes. Cogn Ther Res. 1998;22:561-576. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roy A, Druker S, Hoge EA, Brewer JA. Physician anxiety and burnout. Is mindfulness a solution? Symptom correlates and a pilot study of app-delivered mindfulness training. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e15608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewer JA. The Craving Mind: From Cigarettes to Smartphones to Love—Why We Get Hooked and How We Can Break Bad Habits. Yale University Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Duhigg C. The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davey GC, Hampton J, Farrell J, Davidson S. Some characteristics of worrying: evidence for worrying and anxiety as separate constructs. Person Individ Diff. 1992;13:133-147. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Freeston MH, Rhéaume J, Letarte H, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Why do people worry? Person Individ Diff. 1994;17:791-802. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roemer L, Salters K, Raffa SD, Orsillo SM. Fear and avoidance of internal experiences in GAD: preliminary tests of a conceptual model. Cogn Ther Res. 2005;29:71-88. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salters-Pedneault K, Tull MT, Roemer L. The role of avoidance of emotional material in the anxiety disorders. Appl Prevent Psychol. 2004;11:95-114. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Skinner BF. Operant behavior. Am Psychol. 1963;18:503-515. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sibrava NJ, Borkovec TD, eds. The cognitive avoidance theory of worry. In: Worry and its Psychological Disorders. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2008:239-256. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suhler CL, Churchland PS. Control: conscious and otherwise. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:341-347. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arnsten AF. Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex structure and function. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:410-422. doi: 10.1038/nrn2648 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Arnsten AF. Stress weakens prefrontal networks: molecular insults to higher cognition. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1376-1385. doi: 10.1038/nn.4087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010;78:169-183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goyal M, Singh S, Sibinga EMS, et al. Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:357-368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabat-Zinn J. Full Catastrophe Living: Using the Wisdom of Your Body and Mind to Face Stress. Pain and Illness. Delacorte Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brewer JA, Pbert L. Mindfulness: an emerging treatment for smoking and other addictions? J Family Med. 2015;2:1035. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crane RS, Kuyken W, Williams MG, Hastings RP, Cooper L, Fennell MJV. Competence in teaching mindfulness-based courses: concepts, development and assessment. Mindfulness (NY). 2012;3:76-84. doi: 10.1007/s12671-011-0073-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Marx R. Accessibility versus integrity in secular mindfulness: a Buddhist commentary. Mindfulness (NY). 2015;6:1153-1160. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rycroft-Malone J, Anderson R, Crane RS, et al. Accessibility and implementation in UK services of an effective depression relapse prevention programme–mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT): ASPIRE study protocol. Implement Sci. 2014;9:62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hölzel BK, Lazar SW, Gard T, Schuman-Olivier Z, Vago DR, Ott U. How does mindfulness meditation work? Proposing mechanisms of action from a conceptual and neural perspective. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2011;6:537-559. doi: 10.1177/1745691611419671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Brewer JA. Mindfulness training for addictions: has neuroscience revealed a brain hack by which awareness subverts the addictive process? Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;28:198-203. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brewer JA, Elwafi HM, Davis JH. Craving to quit: psychological models and neurobiological mechanisms of mindfulness training as treatment for addictions. Psychol Addict Behav. 2013;27:366-379. doi: 10.1037/a0028490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brewer JA, Ruf A, Beccia AL, et al. Can mindfulness address maladaptive eating behaviors? why traditional diet plans fail and how new mechanistic insights may lead to novel interventions. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1418. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Elwafi HM, Witkiewitz K, Mallik S, Thornbill TA, 4th, Brewer JA. Mindfulness training for smoking cessation: moderation of the relationship between craving and cigarette use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;130:222-229. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mason AE, Jhaveri K, Cohn M, Brewer JA. Testing a mobile mindful eating intervention targeting craving-related eating: feasibility and proof of concept. J Behav Med. 2018;41:160-173. doi: 10.1007/s10865-017-9884-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kabat-Zinn J, Massion AO, Kristeller J, et al. Effectiveness of a meditation-based stress reduction program in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149:936-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vollestad J, Sivertsen B, Nielsen GH. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for patients with anxiety disorders: evaluation in a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther. 2011;49:281-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wong SY, Tang WK, Mercer SW, et al. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for generalised anxiety disorder and health service utilisation among Chinese patients in primary care: a randomised, controlled trial. Hong Kong Med J. 2016;22 suppl 6:35-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hoge EA, Bui E, Marques L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of mindfulness meditation for generalized anxiety disorder: effects on anxiety and stress reactivity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:786-792. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jazaieri H, Goldin PR, Werner K, Ziv M, Gross JJ. A randomized trial of MBSR versus aerobic exercise for social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2012;68:715-731. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21863 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anxiety & Depression Association of America. ADAA reviewed mental health apps. Accessed March 29, 2021. https://adaa.org/finding-help/mobile-apps

- 59.Deady M, Choi I, Calvo RA, Glozier N, Christensen H, Harvey SB. eHealth interventions for the prevention of depression and anxiety in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:310. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1473-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roy A, Druker S, Hoge EA, Brewer JA. Physician anxiety and burnout: symptom correlates and a prospective pilot study of app-delivered mindfulness training. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e15608. doi: 10.2196/15608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Roy A, Hoge EA, Abrante P, Druker S. Clinical efficacy and psychological mechanisms of an app-based digital therapeutic for generalized anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled trial. SSRN Electron J. 2020. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3712934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brewer JA, Roy A, Deluty A, Liu T, Hoge EA. Can mindfulness mechanistically target worry to improve sleep disturbances? Theory and study protocol for app-based anxiety program. Health Psychol. 2020;39:776-784. doi: 10.1037/hea0000874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]