Abstract

Social isolation and loneliness were already pressing concerns prior to the pandemic, but recent trends suggest a potential broadening of this public health crisis. Social connections have potent influences on health and longevity, and lacking social connection qualifies as a risk factor for premature mortality. However, social factors are often overlooked in medical and healthcare practice. There is also evidence documenting effects on biomarkers and health-relevant behaviors, as well as more proximal means social connection influences physical health. A recent National Academy of Science consensus committee report provides recommendations for how this evidence can inform medical and healthcare. Clinicians play an important role in assessing, preventing, and mitigating the adverse effects of social isolation and loneliness.

Keywords: social isolation, loneliness, social connection, health behavior change, lifestyle medicine

‘The medical community can play a key role in identifying, preventing, and mitigating risk associated with social isolation and loneliness.’

The onset of a global pandemic has brought several key public health issues into greater awareness, including social isolation and loneliness. Closures and other restrictions across the nation and the world aimed at reducing social contact to slow the spread of the virus have also led to widespread concerns about secondary effects—concerns that the very measures meant to protect us may also be doing harm. Although most of these concerns are focused on mental health, there is strong evidence that we should be equally concerned about the physical health consequences of isolation and loneliness. While the full ramifications of the pandemic will not be known for years or perhaps decades, important questions are being raised regarding the short- and long-term consequences of “social distancing” and other restrictions, who may be most vulnerable or at risk, and what steps can be taken to mitigate risk. However, social isolation and loneliness were growing public health concerns well before the COVID-19 pandemic. For instance, previously, the US Surgeon General raised concerns about a “loneliness epidemic,” and the National Academy of Science issued a consensus report on the medical and health care relevance of social isolation and loneliness among older adults. 1 Thus, this pandemic has shed light on a long-standing health issue that may only become more pronounced if it is not prioritized commensurate with the evidence.

This article will highlight the evidence documenting social isolation and loneliness are independent risk factors for health and mortality and, conversely, social connection as a protective factor. This overview will include evidence of both short- and long-term effects and the biological and behavioral mechanisms that combined suggest a causal association with health and mortality. The medical community can play a key role in identifying, preventing, and mitigating risk associated with social isolation and loneliness. The evidence points to the importance of promoting social connection in lifestyle medicine and the importance of integration into existing primary, secondary, and tertiary care and preventative efforts.

Social Isolation and Loneliness as Health Risk Factors

Social isolation and loneliness are widely recognized as important for emotional well-being and mental health; however, their influence goes beyond distress feelings. Social isolation and loneliness predict earlier death—from both suicide 2 as well as from all causes. 3 For example, a meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological data, including more than 3.4 million participants, found that loneliness is associated with risk for earlier death by 26%, social isolation by 29%, and living alone by 32%. 3 Despite relative differences in effect sizes, each significantly predicts mortality, suggesting that both subjective and objective indicators of social deficits are associated with mortality risk.

Social isolation and loneliness have also been linked to various forms of morbidity, including increased risk for heart attack and stroke 4 and type 2 diabetes, mental and behavioral health issues, including increases risk for depression and anxiety, suicidality and addiction, and cognitive health issues including mild cognitive impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s disease. 1 There is also growing evidence that social isolation and loneliness influence healthcare utilization and costs. For example, social isolation among older adults resulted in 6.7 billion in annual Medicare spending.

Social Connection as a Protective Factor

While the health costs of isolation and loneliness are high, there is substantial evidence that social connection has an equal or greater protective effect. For example, meta-analytic data from 148 independent prospective studies demonstrate that being socially connected increases odds of survival by 50%. 5 These effects controlled for age, initial health status, and several other possible confounding (eg, lifestyle) factors. Suggesting social connection is an independent protective factor. Several large-scale prospective studies have since replicated the protective effects on mortality. When we compare the effect sizes of social connection indicators (eg, complex social integration, or averaged across indicators), the effect on mortality was significantly larger than the effect sizes associated with social deficits (eg, social isolation, loneliness, living alone). 3 Therefore, efforts should not be confined to mitigating risk; rather, powerful protective effects should also be promoted in prevention efforts.

Across decades of research, there is now evidence that the magnitude of risks for premature mortality is similar to the risk associated with other well-recognized lifestyle factors. 6 Social factors are similar, and in some cases, exceed the risk associated with these other factors—factors taken quite seriously for health (see Figure 1). Because some variables are linked to risk and others protection, some were inversed so that each bar represents the strength of the effect on survival. Although the magnitude of risk varies across indicators, the risk of loneliness exceeds the risk associated with physical inactivity, obesity, and air pollution. Additional data from a representative study of US older adults found that a medical diagnosis of cancer and hypertension and health behaviors such as smoking were less important than loneliness in predicting mortality risk. 7 This evidence suggests positive social connection should receive serious attention and resources when it comes to health.

Figure 1.

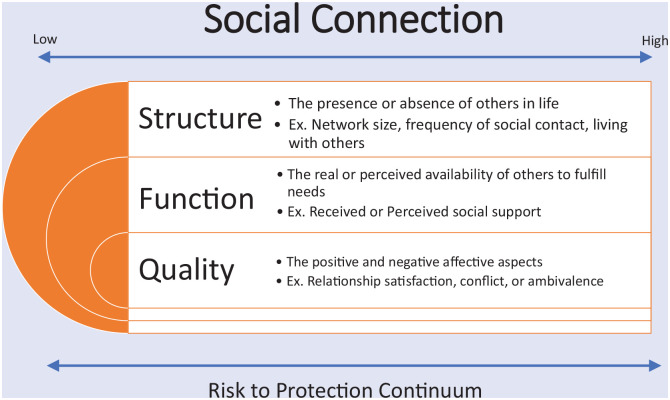

The multi-factorial construct of Social Connection.

Potential Proximal Health Effects

There is evidence of the potential for more immediate effects on health, in addition to the more long-term effects on chronic diseases. First, the distressing feeling experienced when isolated or lonely corresponds to physiological changes. Much like other social species, humans throughout history have needed to rely on others for survival; thus, lacking proximity to trusted others is associated with a general threat response, or heightened state of alert, in the central nervous system (CNS), activating the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA).8,9 This activation of the SNS and HPA can increase blood pressure, stress hormones, and inflammatory responses, increasing the risk for various chronic illnesses if experienced long-term. However, among those with preexisting health conditions, physiological changes may have more proximal effects, including the potential to aggravate the condition, hasten the onset of acute events, or accelerate disease progression. Therefore, social isolation and loneliness may result in more immediately identifiable worsening health among those already predisposed.

Furthermore, there is some evidence that isolation and loneliness increase the risk for infectious diseases. For example, a review of studies over the past 35 years has identified factors associated with susceptibility to cold and flu viruses. 10 In a series of studies, results show that participants experiencing interpersonal stressors such as loneliness increased the likelihood of developing an upper respiratory illness when exposed to cold viruses. Those who had low levels of loneliness and had large social networks had the strongest antibody response to an influenza vaccine. 11 Taken together with other data on the impact of social connection on immune functioning, 12 the broader implications for developing other types of infectious and chronic diseases, and wound healing,13-15 should not be dismissed.

Proximal effects of social isolation and loneliness may also extend to health-relevant behaviors. For example, some evidence suggests that isolation and loneliness are associated with increases in problematic health behaviors, including substance use, inadequate sleep, reduced physical activity, 16 and poorer eating. Furthermore, during the first month of the pandemic, more than 2 million Americans purchased handguns, raising concerns that the social isolation associated with COVID restrictions increased the risk for suicide. 17 Other research has shown a 100% increased risk of death by suicide within 20 days of a handgun purchase. 18 These findings suggest that the risk associated with social isolation and loneliness may not always be downstream chronic diseases, and immediate attention to this issue is needed.

The Continuum of Social Connection

These chronic health and mortality findings are based on scientific evidence that collectively has utilized diverse conceptualization and measurement approaches. Thus, it is important to distinguish between several related terms. There are important distinctions between being homebound, social isolation and loneliness. Homebound refers to never or rarely leaving home over the past month. Social isolation is objectively being alone, having few relationships, or infrequent social contact. 3 Loneliness is a subjective negative experience resulting from inadequate meaningful connections, 19 or the discrepancy between one’s desired level of connection and one’s actual level. 20 Thus, these can co-occur but not necessarily.

Social connection is an umbrella term that comprises the converging evidence demonstrating that the structure, functions, and quality of social relationships all contribute to health and well-being (see Figure 1). The varying conceptual and measurement approaches used in the literature have been categorized into those that examine the existence of relationships and social roles (structure), the actual or perceived availability of support or inclusion (function), and the positive and negative affective qualities (quality) of social relationships. 6 Each of these approaches consistently predicts morbidity and mortality, 5 but are not highly correlated, suggesting each may be contributing to risk and protection independently. 6 Furthermore, the meta-analytic data on mortality found that the odds of survival was 91% among studies using multidimensional assessments of social relationships 91%, compared with 50% when averaging across studies that assessed individual components. 5 Thus, this suggests that approaches using “social connection” as a multifactorial risk and protective factor 6 may be more ideal than focusing on any one particular component.

The evidence, based on aggregate data, also suggests a continuum from risk to protection. Data from four nationally representative samples, including measurement of structure, function, and quality, document a dose-response effect of social connection on physiological regulation (blood pressure, body mass, and inflammation) and health disorders. 21 Importantly, the samples represented the life course, from adolescence to older age. These data suggest for every increase in social connection there was a corresponding decrease in risk. This continuity of influence appears to emerge early and persist over the life course. Physiological dysregulation due to insufficient social connection, if experienced chronically, can lead to chronic diseases and increase the risk for premature mortality. Thus, efforts aimed at disrupting the dysregulation or maintaining regulation associated with social connection are key to delaying or preventing chronic disease and extending lifes pan.

The Role of Physicians and the Health Care System

The health care system is a key and relatively untapped partner in efforts to identify, prevent, and mitigate the adverse health impacts of social isolation and loneliness. 1

It is clear from the evidence that social isolation and loneliness incur adverse health outcomes; thus, the medical community must not relegate this as a nonmedical issue. Physicians and other healthcare professionals play an important role in identifying, preventing, and mitigating these health effects. The World Health Organization’s definition of health is the “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity.” The prevailing medical model, which focuses primarily on diseases, needs to broaden the domains of what is considered acceptable to include social domains.

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued a consensus report focused on enhancing the health care system’s role in addressing the health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. 1 This report identified 5 goals and provided corresponding recommendations related to each of these goals based on the currently available evidence.

Develop a more robust evidence base for effective assessment, prevention, and intervention strategies for social isolation and loneliness

Translate current research into health care practices

Improve awareness of the health and medical impacts of social isolation and loneliness

Strengthen ongoing education and training

Strengthen ties between the health care system and community-based networks and resources

Each of these goals has relevance to how medicine is practiced.

Identify

A key first step to integrating social factors into medicine is via assessment. Given the evidence on continuity of influence, assessment and promotion of social connection should be part of the standard care for every patient from pediatrics to geriatrics. Routine assessments will (1) provide an opportunity to start conversations about the health importance of social connection, (2) identify a patient’s level on the risk spectrum at a given time, and (3) track any changes over time. Such changes are very important for at least two reasons. First, if patients show worsening, it can be an opportunity to intervene. Second, if recommendations, referrals, or formal interventions are offered or implemented, it is important to determine if improvement occurs.

The Institute of Medicine weighed the evidence of various lifestyle factors and recommended the inclusion of social connection/isolation in all electronic health records. 22 Furthermore, the subsequent expert consensus reports have concurred with this recommendation. 1 However, this is not currently routinely collected. One potential reason why social connection/isolation is not routinely collected is that there are many validated instruments to choose from. It will be important when selecting a tool for use in clinical settings that is standardized. Thus, all clinicians should use the same tool or set of tools within any specific healthcare system or organization. Many physicians may feel uncomfortable or have reservations about discussing personal matters with patients, yet routinely ask about many sensitive topics. If such assessments are part of routine care discussed with all patients, it may help remove some of the stigma of discussing the topic.

Prevent

Health care providers should promote positive social connection as a standard part of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention and treatment for all patients. 1 A key component of prevention is awareness and education. One survey suggests that individuals underestimate the degree to which social connection influences health relative to other lifestyle factors. 23 Clinicians should discuss the adverse health outcomes associated with social isolation and loneliness, as well as the evidence indicating social connection is as important to a healthy lifestyle as exercise, limiting alcohol consumption, and quitting smoking. 23

Public awareness is not enough. In a recent survey of over 2000 US adults, 64% of respondents reported that they were aware that social isolation could increase the risk for heart disease, high blood pressure, or sleep disorders; however, only 13% reported that a health care professional had asked them about social isolation, and it was even lower (11%) among those 50 and older. In another study aimed at understanding the general practitioners’ perspective on their role, when interviewed, the practitioners’ responses emphasized general perceptions of loneliness in medicalized and individualistic view. 24 This medicalized view may increase stigma, subsequently creating barriers to raising the topic. A primary finding was the physicians do not feel they have the skills or ability to “fix the problem” and felt that it was more of a personal community issue to solve rather than in primary care. Thus, physicians’ education and competency will be equally important for preventing, assessing, and treating the deleterious health impacts of social isolation and loneliness in clinical settings.

Mitigate

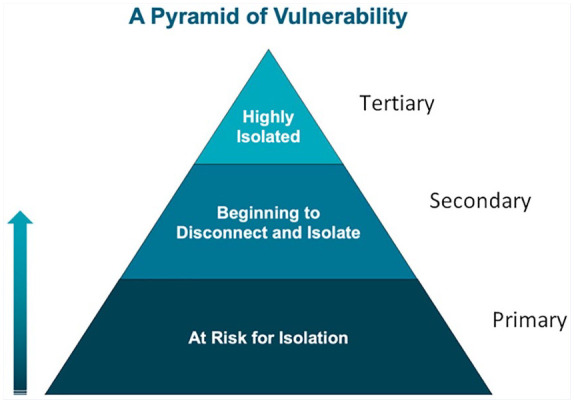

There are several points at which it may be critical to intervene to mitigate adverse health outcomes. Research suggests that several risk factors may increase a person’s risk of becoming isolated or lonely. These include mental or physical health conditions, low education or income, and social factors (eg, unmarried, living alone).1,25 Surveys also suggest younger age may be a risk factor. 26 Life transitions may also trigger isolation and loneliness, including the transition to adulthood, parenthood or retirement, loss of a spouse or significant relationship, employment changes, or changes in health. However, no group appears to be immune and social isolation and loneliness can occur across age, income levels, living situations, and gender. Thus, routine assessments and discussions help identify those at risk for becoming socially disconnected so that mitigation efforts can occur early in the risk trajectory and prevent severe vulnerability (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Pyramid of vulnerability to guide assessment, prevention, and treatment of social isolation and loneliness.

Adapted from an unpublished figure presented to AARP Foundation 2017 by Jeremy Nobel.

Many clinicians may not know how to mitigate risk, given there is currently no pill for loneliness. Although pharmaceutical approaches are being explored in research, no one approach is likely to be the right solution for all, given the variability in underlying causes for social isolation and loneliness. Thus, tailored approaches are both needed and recommended by the National Academy of Science expert consensus committee.

Research suggests there are some evidence-based approaches clinicians can recommend early on to help mitigate any adverse effects. Individual-focused approaches such as mindfulness-based meditation,27,28 engaging in creative arts/expression, and expressions of gratitude29,30 have also shown positive effects on social connection or reducing isolation and loneliness. Data from the National Poll on Healthy Aging found that older adults who regularly engaged in healthy behaviors, such as eating healthier, exercising regularly, and getting enough sleep, were also less likely to experience loneliness. There are several informal social engagement approaches, such as participating in social groups, volunteering, and providing social support to others, which have also been shown to reduce loneliness. For example, some research suggests providing support to others may have a greater benefit than receiving support. Interacting with people in one’s neighborhood or spending at least a few times per week outdoors were also found to be associated with lower feelings of isolation and greater companionship. These are strategies patients can be encouraged to do as part of primary or secondary efforts to nurture and strengthen their social connections and stave off loneliness.

Among those identified as the highest risk, more formalized referrals and interventions may be needed. When evaluating formalized interventions, the quality of the evidence is mixed and generally of poorer quality. 1 Variability in efficacy may be due in part to the heterogeneity of possible underlying causes of isolation and loneliness. For example, cognitive-behavioral therapy may be appropriate for those experiencing loneliness related to mental health 31 but may be less appropriate for isolation or loneliness due to a new or worsening mobility or sensory impairment. When identifying those at highest risk, clinicians and healthcare may use findings to target appropriate interventions to individual patients.

Digital Solutions

There has been increasing interest in digital tools as a means of social connection both informally to stay socially connected and in more formalized digital interventions. However, important questions remain regarding the evidence on the effectiveness of these approaches. Importantly, the decades of evidence that have established the protective effects of social connection are primarily based on in-person contact and predate many of the widely used digital tools. While scalability is an attractive feature, there is currently less evidence of the equivalencies of connecting via digital means. There may be potential limitations to consider (eg, effectiveness, cost, access, and privacy) when utilizing digital tools for mitigating adverse health effects. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic led to the increasing reliance on tools with video chat features to stay socially connected via remote means. However, more than one study found that most older adults did not use video chat features, 32 and even among those who did, video chat was unrelated to loneliness. When considering any solution, clinicians should consider whether the approach will reach the intended target. Furthermore, clinicians need to consider variability in individual access, skills, and preferences.

Overall, these findings suggest clinical recommendations and referrals to social interventions should be evidence-based and tailored to patients’ needs and preferences. To effectively mitigate social isolation and loneliness’s adverse health effects, clinicians need to determine the underlying causes and use evidence-based practices tailored to address those causes appropriately. Furthermore, when determining an appropriate social intervention, patient demographics, background, and potential barriers and preferences should be considered.

Conclusion

To fully address health, medicine needs to integrate social connection into standard care. There is clear evidence of a continuity of risk for morbidity and mortality. Like other social determinants of health, promoting social connection will require solutions coordinated between the health care system and community-based social care providers. Therefore, effective team-based care and the use of tailored community-based services are needed. The data suggest opportunities within clinical settings of care to reduce the incidence and adverse health impacts of social isolation and loneliness and promote flourishing via social connection.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine. Social Isolation and Loneliness in Older Adults: Opportunities for the Health Care System. National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine; 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Van Orden KA, Witte TK, Cukrowicz KC, Braithwaite SR, Selby EA, Joiner TE., Jr. The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:575-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Baker M, Harris T, Stephenson D. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: a meta-analytic review. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10:227-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009-1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holt-Lunstad J, Robles TF, Sbarra DA. Advancing social connection as a public health priority in the United States. Am Psychol. 2017;72:517-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McClintock MK, Dale W, Laumann EO, Waite L. Empirical redefinition of comprehensive health and well-being in the older adults of the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3071-3080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coan JA, Sbarra DA. Social Baseline Theory: the social regulation of risk and effort. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;1:87-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beckes L, Coan J. Social Baseline Theory: the role of social proximity in emotion and economy of action. Soc Person Psychol Compass. 2011;5:976-988. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen S. Psychosocial vulnerabilities to upper respiratory infectious illness: implications for susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Perspect Psychol Sci. 2021;16:161-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pressman SD, Cohen S, Miller GE, Barkin A, Rabin BS, Treanor JJ. Loneliness, social network size, and immune response to influenza vaccination in college freshmen. Health Psychol. 2005;24:297-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi A, Flanigan ME, McEwen BS, Russo SJ. Aggression, social stress, and the immune system in humans and animal models. Front Behav Neurosci. 2018;12:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kelechi TJ, Muise-Helmericks RC, Theeke LA, et al. An observational study protocol to explore loneliness and systemic inflammation in an older adult population with chronic venous leg ulcers. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robinson H, Ravikulan A, Nater UM, Skoluda N, Jarrett P, Broadbent E. The role of social closeness during tape stripping to facilitate skin barrier recovery: preliminary findings. Health Psychol. 2017;36:619-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Broadbent E, Koschwanez HE. The psychology of wound healing. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25:135-140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawkley LC, Thisted RA, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness predicts reduced physical activity: cross-sectional & longitudinal analyses. Health Psychol. 2009;28:354-363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sacks CA, Bartels SJ. Reconsidering risks of gun ownership and suicide in unprecedented imes. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2259-2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Studdert DM, Zhang Y, Swanson SA, et al. Handgun ownership and suicide in California. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2220-2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fried L, Prohaska T, Burholt V, et al. A unified approach to loneliness. Lancet. 2020;395:114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perlman D, Peplau LA. Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In: Gilmour P, Duck S, eds. Personal Relationships 3. Relationships in Disorder. Academic Press; 1981:31-43. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang YC, Boen C, Gerken K, Li T, Schorpp K, Harris KM. Social relationships and physiological determinants of longevity across the human life span. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:578-583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matthews KA, Adler NE, Forrest CB, Stead WW. Collecting psychosocial “vital signs” in electronic health records: why now? What are they? What’s new for psychology? Am Psychol. 2016;71:497-504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haslam SA, McMahon C, Cruwys T, Haslam C, Jetten J, Steffens NK. Social cure, what social cure? The propensity to underestimate the importance of social factors for health. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:14-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jovicic A, McPherson S. To support and not to cure: general practitioner management of loneliness. Health Soc Care Community. 2020;28:376-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlberg L, McKee KJ, Frank A, Naseer M. A systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2021:1-25. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1876638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shovestul B, Han J, Germine L, Dodell-Feder D. Risk factors for loneliness: the high relative importance of age versus other factors. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay EK, Young S, Brown KW, Smyth JM, Creswell JD. Mindfulness training reduces loneliness and increases social contact in a randomized controlled trial. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:3488-3493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creswell JD, Irwin MR, Burklund LJ, et al. Mindfulness-based stress reduction training reduces loneliness and pro-inflammatory gene expression in older adults: a small randomized controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2012;26:1095-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartlett MY, Arpin SN. Gratitude and loneliness: enhancing health and well-being in older adults. Res Aging. 2019;41:772-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caputo A. The relationship between gratitude and loneliness: the potential benefits of gratitude for promoting social bonds. Eur J Psychol. 2015;11:323-334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B, et al. A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52:627-638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kotwal AA, Holt-Lunstad J, Newmark RL, et al. Social isolation and loneliness among San Francisco Bay area older adults during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place orders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021;69:20-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]