Abstract

Background

Atherosclerotic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) can lead to disabling ischemia and limb loss. Treatment modalities have included risk factor optimization through life‐style modifications and medications, or operative approaches using both open and minimally invasive techniques, such as balloon angioplasty. Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) angioplasty has emerged as a promising alternative to uncoated balloon angioplasty for the treatment of this difficult disease process. By ballooning and coating the inside of atherosclerotic vessels with cytotoxic agents, such as paclitaxel, cellular mechanisms responsible for atherosclerosis and neointimal hyperplasia are inhibited and its devastating complications are prevented or postponed. DEBs are considerably more expensive than uncoated balloons, and their efficacy in improving patient outcomes is unclear.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of drug‐eluting balloons (DEBs) compared with uncoated, nonstenting balloon angioplasty in people with symptomatic lower‐limb peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Search methods

The Cochrane Vascular Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (last searched December 2015) and Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) (2015, Issue 11). The TSC searched trial databases for details of ongoing and unpublished studies.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized controlled trials that compared DEBs with uncoated, nonstenting balloon angioplasty for intermittent claudication (IC) or critical limb ischemia (CLI).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors (AK, TA) independently selected the appropriate trials and performed data extraction, assessment of trial quality, and data analysis. The senior review author (DKR) adjudicated any disagreements.

Main results

Eleven trials that randomized 1838 participants met the study inclusion criteria. Seven of the trials included femoropopliteal arterial lesions, three included tibial arterial lesions, and one included both. The trials were carried out in Europe and in the USA and all used the taxane drug paclitaxel in the DEB arm. Nine of the 11 trials were industry‐sponsored. Four companies manufactured the DEB devices (Bard, Bavaria Medizin, Biotronik, and Medtronic). The trials examined both anatomic and clinical endpoints. There was heterogeneity in the frequency of stent deployment and the type and duration of antiplatelet therapy between trials. Using GRADE assessment criteria, the quality of the evidence presented was moderate for the outcomes of target lesion revascularization and change in Rutherford category, and high for amputation, primary vessel patency, binary restenosis, death, and change in ankle‐brachial index (ABI). Most participants were followed up for 12 months, but one trial reported outcomes at five years.

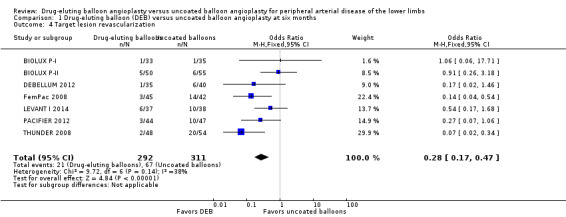

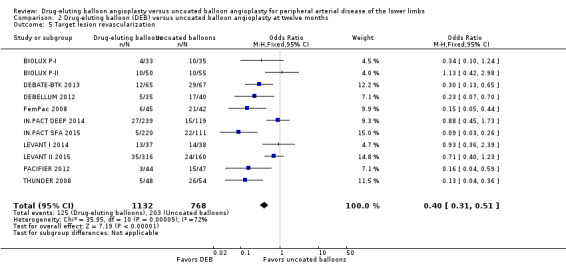

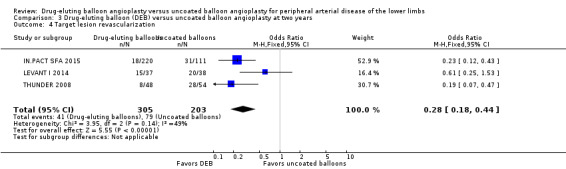

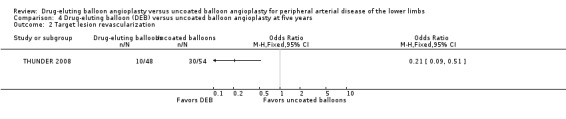

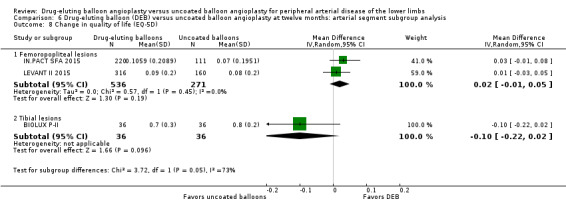

There were better outcomes for DEBs for up to two years in primary vessel patency (odds ratio (OR) 1.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.22 to 9.57 at six months; OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.56 at 12 months; OR 3.51, 95% CI 2.26 to 5.46 at two years) and at six months and two years for late lumen loss (mean difference (MD) ‐0.64 mm, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.28 at six months; MD ‐0.80 mm, 95% CI ‐1.44 to ‐0.16 at two years). DEB were also superior to uncoated balloon angioplasty for up to five years in target lesion revascularization (OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.47 at six months; OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.51 at 12 months; OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.44 at two years; OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.51 at five years) and binary restenosis rate (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.67 at six months; OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.98 at 12 months; OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.66 at two years; OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.30 at five years). There was no significant difference between DEB and uncoated angioplasty in amputation, death, change in ABI, change in Rutherford category and quality of life (QoL) scores, or functional walking ability, although none of the trials were powered to detect a significant difference in these clinical endpoints. We carried out two subgroup analyses to examine outcomes in femoropopliteal and tibial interventions as well as in people with CLI (4 or greater Rutherford class), and showed no advantage for DEBs in tibial vessels at six and 12 months compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty. There was also no advantage for DEBs in CLI compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months.

Authors' conclusions

Based on a meta‐analysis of 11 trials with 1838 participants, there is evidence of an advantage for DEBs compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty in several anatomic endpoints such as primary vessel patency (high‐quality evidence), binary restenosis rate (moderate‐quality evidence), and target lesion revascularization (low‐quality evidence) for up to 12 months. Conversely, there is no evidence of an advantage for DEBs in clinical endpoints such as amputation, death, or change in ABI, or change in Rutherford category during 12 months' follow‐up. Well‐designed randomized trials with long‐term follow‐up are needed to compare DEBs with uncoated balloon angioplasties adequately for both anatomic and clinical study endpoints before the widespread use of this expensive technology can be justified.

Keywords: Humans; Amputation, Surgical; Amputation, Surgical/statistics & numerical data; Angioplasty, Balloon; Angioplasty, Balloon/methods; Angioplasty, Balloon/mortality; Drug‐Eluting Stents; Femoral Artery; Lower Extremity; Lower Extremity/blood supply; Paclitaxel; Paclitaxel/therapeutic use; Peripheral Arterial Disease; Peripheral Arterial Disease/mortality; Peripheral Arterial Disease/therapy; Popliteal Artery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Tibial Arteries; Time Factors; Vascular Patency

Plain language summary

Uncoated balloon angioplasty versus drug‐eluting balloon angioplasty for peripheral arterial disease of the lower limbs

Background

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) of the lower limbs is a widespread condition that affects many people. In its advanced form, PAD can lead to pain, infections, and amputation. People with PAD are usually first treated with medicines and lifestyle modifications including strategies to stop smoking and a walking program to optimize their general health. People who require an operation might have a traditional open surgery or a less invasive procedure known as angioplasty, which uses a balloon to open the blockages in the arteries. A new type of angioplasty, known as drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) angioplasty, has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional balloon angioplasty for the treatment of patients with PAD. By using DEBs to balloon and coat the inside of the blood vessels (tubes that carry blood around the body) with medicines to treat cancer (chemotherapy) such as paclitaxel, the hope is to halt the progression of PAD and prevent or postpone its devastating complications. The goal of this review was to determine how DEB angioplasty compares with traditional balloon angioplasty for the treatment of PAD of the lower limbs.

Study characteristics and key results

Our review included 11 clinical trials that randomized 1838 participants (current until December 2015). The trials included thigh and leg arteries above and below the knee. The trials were carried out in Europe and the USA, and all used DEBs that contained paclitaxel. Four companies manufactured the DEB devices: Bard, Bavaria Medizin, Biotronik, and Medtronic. Most participants were followed for 12 or more months (called follow‐up). At six and 12 months of follow‐up, DEBs were associated with improved primary vessel patency, which is an indicator of whether a vessel is still patent without any further interventions (blood flowing well), late lumen loss, which is the difference in millimeters between the angioplastied segment and how narrow it is on follow‐up, target lesion revascularization, which is an indicator of whether a person received more than one treatment to the same artery during the period covered by the study, and binary restenosis, which occurs when a treated artery becomes narrowed again after being previously treated.

Unfortunately, early anatomic (structural) advantages of DEBs were not accompanied by improvements in quality of life, functional walking ability, or in the occurrence of amputation or death. When we specifically examined arteries below the knee and people who had very advanced PAD, we found no clinical or angiographic advantage for DEBs at 12 months of follow‐up compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty. In summary, DEBs have several anatomic advantages over uncoated balloons for the treatment of lower limb PAD for up to 12 months after undergoing the procedure. However, more data are needed to assess the long‐term results of this treatment option adequately.

Quality of the evidence

All the trials had differences in the way in which they inserted the balloons, and in the type and duration of additional antiplatelet (anticlotting) therapy, leading to downgrading of the quality of the evidence. The quality of the evidence presented was moderate for target lesion revascularization and change in Rutherford category (a way of classifying PAD), and high for amputation, primary vessel patency, binary restenosis, death, and change in ankle‐brachial index (which is used to predict the severity of PAD).

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Drug‐eluting balloon versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months.

| Drug‐eluting balloon compared to uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with peripheral arterial disease of the lower limbs Setting: hospital Intervention: drug‐eluting balloon angioplasty Comparison: uncoated balloon angioplasty | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months | Risk with drug‐eluting balloon angioplasty at 12 months | |||||

| Amputation | Study population | OR 1.56 (0.73 to 3.33) | 1649 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High 1 | ‐ | |

| 14 per 1000 | 22 per 1000 (10 to 46) | |||||

| Primary vessel patency | Study population | OR 1.92 (1.45 to 2.56) | 882 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High 1 | ‐ | |

| 479 per 1000 | 638 per 1000 (571 to 702) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 487 per 1000 | 645 per 1000 (579 to 708) | |||||

| Target lesion revascularization | Study population | OR 0.40 (0.31 to 0.51) | 1900 (11 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Low 1, 2, 3 | ‐ | |

| 264 per 1000 | 126 per 1000 (100 to 155) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 368 per 1000 | 189 per 1000 (153 to 229) | |||||

| Binary restenosis | Study population | OR 0.38 (0.15 to 0.98) | 1094 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1, 3 | ‐ | |

| 350 per 1000 | 170 per 1000 (75 to 346) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 477 per 1000 | 257 per 1000 (120 to 472) | |||||

| Death | Study population | OR 1.09 (0.64 to 1.85) | 1649 (9 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High 1 | ‐ | |

| 43 per 1000 | 46 per 1000 (28 to 76) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 45 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (29 to 80) | |||||

| Change in Rutherford category | ‐ | The mean change in Rutherford category in the intervention group was 0.1 lower (0.29 lower to 0.1 higher) | ‐ | 623 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderate 1 4 | A positive change in Rutherford category reflects a worsening clinical status, although in this case the difference was not statistically significant |

| Change in ankle‐brachial index | ‐ | The mean change in ankle‐brachial index in the intervention group was 0.03 lower (0.07 lower to 0.01 higher) | ‐ | 656 (3 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊕ High 1 | A negative change in the ankle‐brachial index reflects a worsening clinical status, although in this case the difference was not statistically significant |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; OR: odds ratio; RCT: randomized controlled trial. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate quality: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low quality: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low quality: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

1 All of the included trials were at a high risk of performance bias due to lack of blinding of operators. However, because this is an intrinsic limitation to intervention trials, we did not downgrade the GRADE class because of performance bias. 2 Funnel plot analysis indicated a likely publication bias, which resulted in downgrading of the GRADE class. 3 There was moderate heterogeneity between the included studies (P < 0.001), which resulted in downgrading of the GRADE class. 4 There was moderate heterogeneity between the included studies (P = 0.04), which resulted in downgrading of the GRADE class.

Background

Description of the condition

Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is a major healthcare challenge resulting in significant age‐related patient morbidity. It is estimated to affect 4% of adults aged 40 years or older and 14.5% of adults aged 70 years or older in the USA (Selvin 2004). The presence of PAD does not always lead to symptoms, and asymptomatic PAD has been reported in 8% of Scottish adults (Fowkes 1991).

People with symptomatic lower‐limb PAD commonly present with intermittent claudication (IC). The prevalence of IC in people with PAD is estimated to be 3% in people aged 40 years and 6% in people aged 60 years (Norgren 2007). About 25% of people with IC will develop more severe claudication and a deterioration in functional status of their affected limb. Some of those people will also eventually develop critical limb ischemia (CLI) (Norgren 2007). Major amputation is required in less than 10% of people with IC (Aquino 2001).

Description of the intervention

The medical management of lower‐limb PAD is based on an appropriate diet and exercise regimen and vascular disease risk‐factor modification through smoking‐cessation, blood pressure control, tight control of blood sugar levels in people with diabetes, and the prescription of lipid‐lowering and antiplatelet medications (Hirsch 200). Surgical management is indicated when people develop CLI or debilitating IC that is refractory to nonoperative management.

While bypass with an autologous vein or prosthetic conduit is the mainstay of open surgical management of PAD, percutaneous endovascular interventions provide another treatment alternative. Percutaneous interventions use ultrasound and fluoroscopic guidance to access and cannulate the diseased artery. A balloon catheter is then employed to provide pneumatic dilation of the stenotic or occluded vessel segment. The first balloon catheters used for this purpose were not coated with any medications and showed excellent efficacy in treating these diseased arteries (Norgren 2007). More recently, drug‐eluting balloons (DEBs), in addition to stents, have been placed to provide additional support when balloon angioplasty results are not satisfactory.

Balloon angioplasty, with or without stent placement, has the advantage of a shorter hospital stay and fewer short‐term postinterventional complications compared with bypass surgery. It has also been shown to be similar to open surgery in overall and amputation‐free survival at two years (BASIL 2005). However, on long‐term follow‐up, bypass surgery with autologous venous conduit was associated with a seven‐month increase in overall survival while amputation‐free survival remained the same (Bradbury 2010). In cases where autologous venous conduit is not available for bypass, the differences between balloon angioplasty and bypass using a prosthetic graft are probably minimal in terms of outcome (Bradbury 2010).

How the intervention might work

Elastic recoil and vessel restenosis secondary to neointimal hyperplasia remain a challenge for all of the available lower‐limb PAD treatment interventions. Numerous strategies have sought to delay vessel restenosis, including the use of drug‐eluting stents and DEBs. To date, there is only one commercially available drug‐eluting stent for use in the superficial femoral artery (Dake 2013).

DEBs were developed to provide a complete and homogenous coating of an antiproliferative agent to the arterial wall (Seedial 2013). The most commonly used agent is paclitaxel, a highly lipophilic drug that has been shown to prevent neointimal hyperplasia after balloon angioplasty (Axel 1997). The immunosuppressant agent sirolimus has also been used to prevent neointimal hyperplasia (Seedial 2013). The advantages of DEBs compared with other percutaneous treatment modalities include the absence of stent thrombosis or scaffolding to disrupt patterns of flow, immediate drug release, and no residual foreign body (Seedial 2013). However, DEBs are more costly and carry the potential for long‐term negative vessel remodeling and elastic recoil.

Why it is important to do this review

Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of angioplasty using DEBs compared with conventional uncoated balloon angioplasty. Our goal is to review the evidence for the use of DEBs in the management of lower‐limb PAD systematically. This will help guide decision‐making when considering whether to use this costly treatment modality and determine whether it is associated with improved clinical outcomes compared with conventional balloon angioplasty.

Objectives

To assess the efficacy of drug‐eluting balloons (DEBs) compared with uncoated, nonstenting balloon angioplasty in people with symptomatic lower‐limb peripheral arterial disease (PAD).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compare DEBs with uncoated balloon angioplasty for IC or CLI.

Types of participants

People with IC or CLI undergoing drug‐eluting or uncoated balloon angioplasty for symptomatic lower‐limb PAD.

Types of interventions

We compared DEBs for PAD of the lower limbs with uncoated, nonstenting balloon angioplasty. Endovascular access in the included studies was established percutaneously or through a limited incision. We did not include studies of DEBs for the treatment of instent restenosis of the lower‐limb, as well as studies where DEBs were used simultaneously in combination with other angioplasty techniques (such as hybrid procedures involving surgery and DEBs). Our review focused on primary arterial interventions only. We excluded reinterventions and studies using cutting balloon angioplasty.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of amputation.

Amputation‐free survival, defined as the probability of being alive without an amputation.

Amputation‐free rate, defined as the patency of the target vessels and freedom from amputation.

Vessel patency (primary and secondary), as determined by delayed arterial lumen loss, target lesion revascularization, and binary restenosis rate measured with duplex ultrasound or angiography.

Death.

Secondary outcomes

Change in Fontaine stage or Rutherford category of PAD (Norgren 2007).

Change in ankle‐brachial index (ABI).

Change in quality of life (QoL) scores.

Change in functional walking ability, as measured by the Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

The Cochrane Vascular Trials Search Co‐ordinator (TSC) searched the Specialised Register (December 2015). In addition, the TSC searched the Cochrane Register of Studies (CRS) (www.metaxis.com/CRSWeb/Index.asp; (CENTRAL) 2015, Issue 11). See Appendix 1 for details of the search strategy used to search the CRS. The Specialised Register is maintained by the TSC and is constructed from weekly electronic searches of MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, AMED, and through handsearching relevant journals. The full list of the databases, journals, and conference proceedings which have been searched, as well as the search strategies used are described in the Specialised Register section of the Cochrane Vascular module in theCochrane Library (www.cochranelibrary.com).

In addition, the TSC searched the following trial databases for details of ongoing and unpublished studies. See Appendix 2 for details of the search.

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry (apps.who.int/trialsearch/).

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/).

ISRCTN registry (www.controlled‐trials.com/).

Searching other resources

We examined the bibliographies of relevant papers found from the electronic searches to identify other studies. We also attempted to contact study authors for additional information when necessary.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (AK and TA) independently selected trials for inclusion in this review. These trials were sent to a third review author (DR), who assessed and confirmed their suitability for inclusion and acted as an adjudicator in the event of disagreement. The Criteria for considering studies for this review section details the inclusion criteria used in this selection process.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (AK and TA) extracted the data from each trial, including participant demographics (age, gender, comorbidities, Fontaine stage or Rutherford category of PAD, and ABI), interventions (DEBs and other balloon types, vessels treated, history of previous stent placement), and outcomes (as specified in the Criteria for considering studies for this review section). A third review author (DR), then cross‐checked the data and acted as an adjudicator in the event of disagreement. Statistical analysis complied with the standard methods of Cochrane Vascular. We used the computer software package Review Manager 5 to perform all statistical analyses and generate figures (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (AK and TA) assessed potential risks of bias for all included studies using the Cochrane's tool for assessing risk of bias (Higgins 2011). The tool assesses bias in six different domains: sequence generation; allocation concealment; blinding of participants, personnel, and outcome assessors; incomplete outcome data; selective outcome reporting; and other sources of bias. Each domain receives a score of high, low, or unclear depending on each review author's judgment. A third review author (DR) acted as an adjudicator in the event of disagreement. Where doubt existed as to a potential risk of bias, we contacted the study authors for clarification.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated and reported continuous outcome measures such as lumen loss using the mean difference (MD) and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) between the two treatment groups. We calculated and reported dichotomous outcome measures including the occurrence of a postprocedural complication such as death using the odds ratio (OR) and associated 95% CI, depending on the reported data. We based calculations on an intention‐to‐treat approach and all randomized participants were included in the analysis regardless of loss to follow‐up. In one study (FemPac 2008), where the late lumen loss and change in ABI were reported as medians, rather than means, we converted the median values to means as per the method described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the treated limb for outcomes in which repeat or additional procedures on the contralateral side were possible and reported. The unit of analysis was the individual participant when considering participant death, QoL scores, and change in functional walking ability.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted authors of the included studies to inquire about missing or incomplete data, such as information on participants who dropped out of the study, and missing statistics. We excluded no studies from the meta‐analysis due to concerns about missing data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed inter‐study heterogeneity visually using a forest plot. We also calculated the I2 statistic to measure the amount of inter‐study heterogeneity. We considered I2 values less than 50% as indicative of low heterogeneity, I2 values between 50% and 75% as indicative of moderate heterogeneity, and I2 values greater than 75% as indicative of significant heterogeneity (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We constructed a funnel plot to test for reporting bias in meta‐analyses that included 10 or more studies (Higgins 2011).

Data synthesis

We used a fixed‐effect model to calculate the pooled treatment effect data and 95% CIs for continuous and dichotomous outcome variables, as detailed under Measures of treatment effect. We used a random‐effects model when we found significant heterogeneity (defined as I2 greater than 75%). We created a forest plot for each treatment effect, as per Cochrane Vascular guidelines.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed subgroup analyses by the arterial segments treated (femoropopliteal versus tibial), and the severity of PAD (studies that only included participants with a Rutherford's class greater than 4). We were unable to perform subgroup analyses by type of DEB pharmacologic agent, as all the studies used paclitaxel.

Sensitivity analysis

We sequentially excluded studies with a high risk of bias in several domains (as described in the Assessment of risk of bias in included studies section) and performed a pooled sensitivity analysis in order to assess whether the included studies, deemed to be biased, impacted the final analysis.

'Summary of findings' table

We prepared 'Summary of findings' tables to present the evidence for DEB versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months of follow‐up in participants who underwent endovascular lower‐limb interventions for symptomatic PAD. We chose this time point because the greatest amount of data from the included trials was available at 12 months of follow‐up. We used no external information in generating the 'Assumed risk' column. We used the GRADE approach to evaluate the evidence and assign one of four levels of quality: high, moderate, low, or very low (Higgins 2011). No departures from the standard methods for generating these tables were required. We included the following primary and secondary endpoints described under the Types of outcome measures section: amputation, primary vessel patency, target lesion revascularization, binary restenosis, death, change in Rutherford category, and change in ABI. These endpoints were chosen because we deemed them to be the most clinically relevant.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

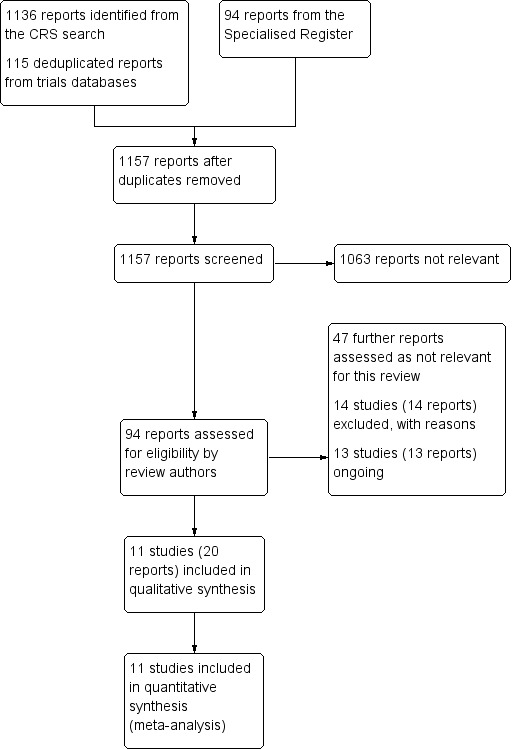

See Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

The review included 11 randomized controlled trials that compared DEB with uncoated balloon angioplasty for lower extremity IC or CLI (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; DEBELLUM 2012; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT DEEP 2014; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015; PACIFIER 2012; THUNDER 2008). The Characteristics of included studies table lists these in more detail.

All of the included studies were partially or entirely conducted in Europe. Three studies also enrolled people in the USA (IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015). Most studies examined treatments for femoropopliteal arteries (BIOLUX P‐I; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015; PACIFIER 2012; THUNDER 2008), and three studies only examined tibial arteries (BIOLUX P‐II; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; IN.PACT DEEP 2014). The DEBELLUM 2012 trial examined both femoropopliteal and tibial arteries. Every included trial used paclitaxel as the balloon‐coating drug.

Medtronic manufactured the most‐frequently studied DEBs and sponsored three trials (IN.PACT DEEP 2014; IN.PACT SFA 2015; PACIFIER 2012). Two trials also used Medtronic devices but did not report receiving any industry sponsorship (DEBATE‐BTK 2013; DEBELLUM 2012). Bavaria Medizin (FemPac 2008; THUNDER 2008), Bard (LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015), and Biotronik (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II) sponsored two trials each.

We also identified 13 trials that were either ongoing or awaiting publication (see Characteristics of ongoing studies table). We contacted authors of all ongoing studies to request study data.

Excluded studies

We excluded 14 trials from our review (COPA CABANA; DEBATE‐ISR; DEBATE SFA; DEFINITIVE AR; EURO CANAL; FAIR; Freeway Stent Study; IDEAS; ISAR‐PEBIS; ISAR‐STATH; PACUBA 1; PHOTOPAC; RAPID; SWEDEPAD). The reasons for exclusion are outlined in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Studies were most commonly excluded for comparing DEB and bare‐metal or drug‐eluting stenting (DEBATE SFA; IDEAS; RAPID), DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty for the management of instent restenosis (COPA CABANA; DEBATE‐ISR; FAIR; Freeway Stent Study; ISAR‐PEBIS; PACUBA 1), or DEB with or without atherectomy (DEFINITIVE AR; ISAR‐STATH). One trial compared DEB with or without photoablation therapy for the prevention of instent restenosis (PHOTOPAC). The SWEDEPAD trial compared drug‐eluting technologies (balloon or stents) with nondrug‐eluting technologies (balloons or stents). The EURO CANAL was terminated early before any data were collected because the manufacturer withdrew the product from the market.

Risk of bias in included studies

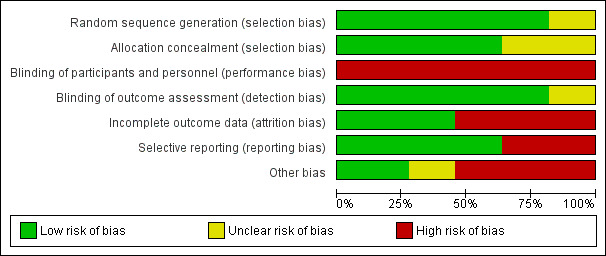

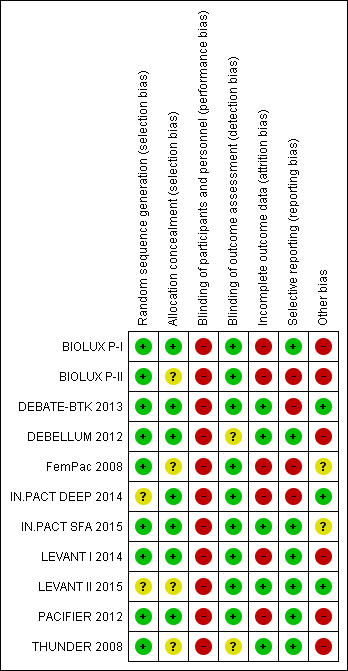

See 'Risk of bias' tables in the Characteristics of included studies table and summary results in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Of the included studies, three were at high risk of bias and were excluded in sensitivity analyses to determine their impact (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008). BIOLUX P‐I was at high risk of bias because of a low follow‐up compliance and a high rate of bailout stenting (26.7%) in the control arm. Furthermore, more than half of the participants in both arms had a history of peripheral vascular interventions, and it is unclear whether the lesions studied in the trial had been previously treated. BIOLUX P‐II did not blind the operators or the participants to the procedure. Approximately 20% of the participants in the intervention arm were lost to follow‐up, and the rate of technical success in the study was relatively low for both arms (54.5% for the DEB arm and 59.6% for the control arm). FemPac 2008 similarly did not have adequate follow‐up data on 27% of the DEB arm and 17% of the control arm. Furthermore, approximately 11% of the trial participants were stented, but the outcomes of those participants were not reported separately.

Allocation

Most of the included studies were at a low risk for sequence generation selection bias. IN.PACT DEEP 2014 randomized participants using "blocks of sealed envelopes" without specifying the methodology for generating those randomization blocks. LEVANT II 2015 did not specify how participants were randomized or allocated to either study arm.

Similarly, most studies were at a low risk for allocation concealment selection bias. However, four studies did not specify how allocation concealment bias was addressed (BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008; LEVANT II 2015; THUNDER 2008).

Blinding

All of the included studies were at high risk for performance bias because the operators were not blinded to the procedure. In BIOLUX P‐II, neither the participants nor the operators were blinded.

Conversely, the risk of detection bias was low as study authors mostly ensured that outcome assessment was carried out by other blinded investigators. The DEBELLUM 2012 authors stated that "postoperative evaluation was deferred to different physicians not informed about the assigned intervention", but it was unclear what type of physicians performed those evaluations and what type of qualifications they had. The THUNDER 2008 authors stated that some of the operators also performed some of the poststudy evaluations.

Incomplete outcome data

Six trials were at high risk of attrition bias (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT DEEP 2014; LEVANT I 2014; PACIFIER 2012). In BIOLUX P‐I, four participants withdrew consent and five participants were lost to follow‐up, which equals a 15% attrition of the study population. Similarly, in BIOLUX P‐II, 19% of participants of the DEB arm either withdrew from the study or were lost to follow‐up at 12 months. FemPac 2008 had six‐month data available on only 73% of participants in the intervention arm and 83% of participants in the control arm. In IN.PACT DEEP 2014, the authors stated that low angiographic and wound imaging compliance may have limited the full assessment of the interventions. In LEVANT I 2014, six‐month angiographic follow‐up was available for 80% of the intervention arm and 69% of the control arm. The PACIFIER 2012 authors reported missing primary outcome data on 20.5% of the intervention arm and 27.3% of the control arm.

Selective reporting

Four trials were at high risk of bias due to incomplete reporting of data (BIOLUX P‐II; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT DEEP 2014). In BIOLUX P‐II, all prespecified outcomes were reported, but the results were not stratified by the type of treated infra‐popliteal vessels (i.e. anterior tibial, posterior tibial, or peroneal arteries). The authors also did not specify whether those participants with more than one target lesion (33.3% of DEB participants and 44.4% of percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) participants) had several target vessels and whether the outcomes differed by the number of treated lesions and vessels. DEBATE‐BTK 2013 was designed to assess infra‐popliteal arterial lesions but some of the participants also received treatment for femoropopliteal lesions. The study authors stated that inflow lesions located in the femoropopliteal segment were "treated by standard techniques during the same session" without elaborating on the nature or number of those techniques. FemPac 2008 reported that "no Doppler or angiographic information was obtained from 7 patients in the control and 9 patients in the coated balloon group", which amounts to approximately 18% of the study participant population. IN.PACT DEEP 2014 did not report several outcomes that were prespecified in the study protocol, such as change in Rutherford classification and QoL scores.

Other potential sources of bias

A major source of bias in many of the included studies was the concurrent use of stenting without separate reporting of the outcomes of stented participants. One quarter of the BIOLUX P‐I control arm (26.7%) required bailout stenting. LEVANT I 2014 randomized participants to the intervention or control arms after successful predilation or stenting "based on whether the interventionalist intended to use only balloon dilation of the lesion or intended concomitant stenting". Twenty‐six per cent of trial participants were stented prior to randomization, and a further 3% in the intervention and 16% in the control arm received "bailout stenting" after undergoing the intended therapy. The DEBELLUM 2012 authors reported that the "decision to implant a nitinol stent in the SFA [superficial femoral artery] territory was left to the judgment of the operator and typically driven by lesion length and presence of severe calcification". However, these stent‐deployment criteria were unclear, and approximately 37% of the treated lesions in the study were stented. The FemPac 2008 authors similarly reported that 11% of all participants received a stent, the PACIFIER 2012 authors reported that 21% of intervention and 34% of control participants received a stent, and in THUNDER 2008, 4% of intervention and 22% of control participants received a stent. The clinical outcomes of those stented participants were not reported separately. LEVANT II 2015 addressed this potential source of bias by only randomizing participants who did not require a stent after an initial angiogram.

In BIOLUX P‐I, predilation was performed more often in DEB than PTA participants (66.7% with DEB versus 30% with PTA, P = 0.01), and technical success was higher in the DEB group (76.7% with DEB versus 46.7% with PTA, P = 0.02). Most of the DEB (56.7%) and PTA (60%) participants had a history of previous peripheral interventions, although the type and location of those interventions was not specified.

In BIOLUX P‐II, while no bailout stenting was required in either treatment arm, the authors had a relatively low technical success rate (defined as less than 30% residual stenosis) in both arms (54.2% with DEB, 59.6% with PTA).

Device malfunction in LEVANT I 2014 was another potential source of bias. Eight DEB devices (16%) malfunctioned and failed to deploy. It was unclear how those participants were managed.

The approach to antiplatelet therapy also varied between trials. While FemPac 2008 did not specify the duration of antiplatelet therapy, participants in all the other trials received acetylsalicylic acid (ASA; aspirin) and at least four weeks of a second antiplatelet agent, most commonly clopidogrel. However, in IN.PACT DEEP 2014 and IN.PACT SFA 2015, the duration of the second antiplatelet agent depended on by whether a stent was deployed. Nonstented participants received a minimum of one month, while stented participants received a minimum of three months of a second antiplatelet agent.

While paclitaxel was used in the intervention arm of all the analyzed studies, there was variability in the paclitaxel dose and balloon drug carrier according to the type of DEB device used.

Finally, DEB device manufacturers sponsored nine of the 11 included studies (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT DEEP 2014; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015; PACIFIER 2012; THUNDER 2008). In the IN.PACT SFA 2015 study, every author listed in the published manuscript declared a financial relationship with the DEB device manufacturer.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcomes

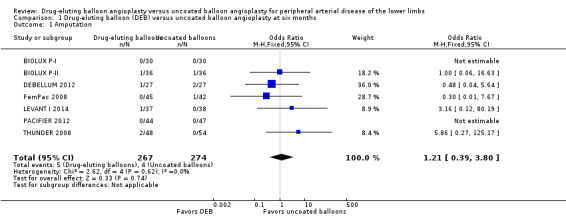

Amputation

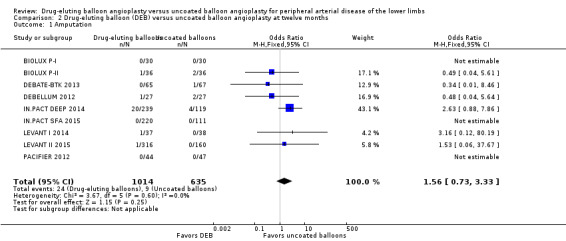

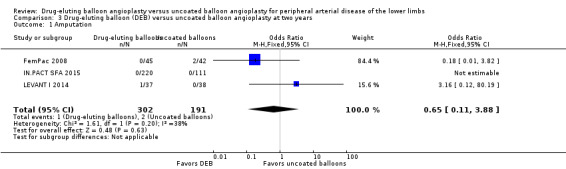

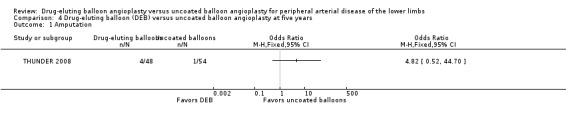

The incidence of amputation was reported as a secondary endpoint in the included trials. While this outcome was not listed in the study protocol, we included it in the analysis because only one trial reported amputation‐free survival (IN.PACT DEEP 2014). There was no significant difference in the incidence of amputations between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.1; OR 1.21, 95% CI 0.39 to 3.80; 541 participants; 7 studies); 12 months (Analysis 2.1; OR 1.56, 95% CI 0.73 to 3.33; 1649 participants; 9 studies); two years (Analysis 3.1; OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.88; 493 participants; 3 studies); or five years (Analysis 4.1; OR 4.82, 95% CI 0.52 to 44.70; 102 participants; 1 study).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 1 Amputation.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 1 Amputation.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 1 Amputation.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at five years, Outcome 1 Amputation.

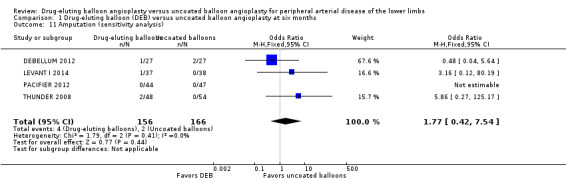

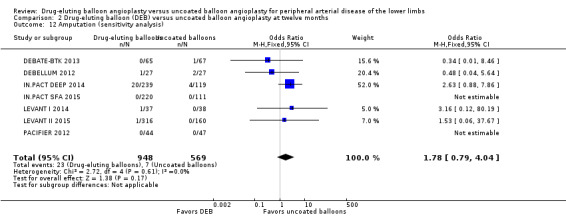

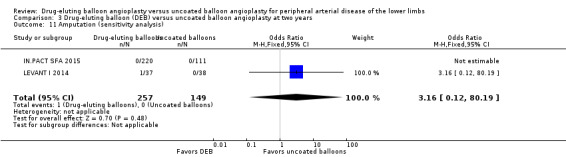

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 at six and 12 months and two years did not result in any significant differences in amputation outcomes (Analysis 1.11; OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42 to 7.54; 322 participants; 4 studies at six months; Analysis 2.12; OR 1.78, 95% CI 0.79 to 4.04; 1517 participants; 7 studies at 12 months; Analysis 3.11; OR 3.16, 95% CI 0.12 to 80.19; 406 participants; 2 studies at two years). The sensitivity analysis was carried out due to concerns about participant follow‐up (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008), and technical success rate (BIOLUX P‐II) in the study population.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 11 Amputation (sensitivity analysis).

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 12 Amputation (sensitivity analysis).

3.11. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 11 Amputation (sensitivity analysis).

Amputation‐free survival

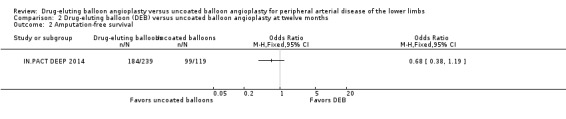

Only IN.PACT DEEP 2014 reported amputation‐free survival at 12 months in (Analysis 2.2; OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.19; 358 participants; 1 study). The trial showed a trend towards improved amputation‐free survival among control arm participants compared with the DEB arm, although this difference did not reach statistical significance.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 2 Amputation‐free survival.

Amputation‐free rate

None of the included studies reported amputation‐free rate.

Vessel patency

Primary vessel patency

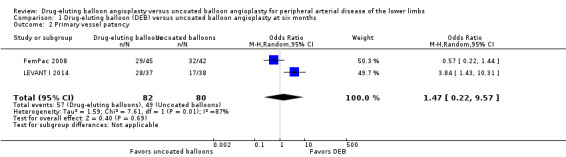

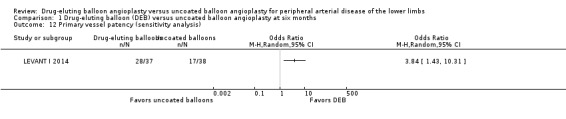

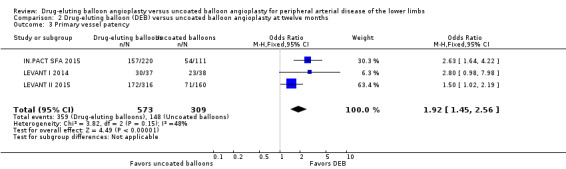

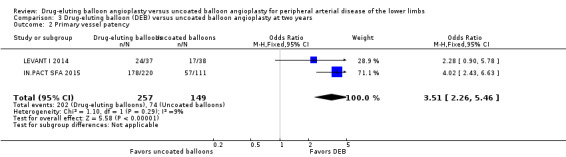

There was no significant difference in primary vessel patency between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.2; OR 1.47, 95% CI 0.22 to 9.57; 162 participants; 2 studies). However, exclusion of FemPac 2008 resulted in a significant advantage for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.12; OR 3.84, 95% CI 1.43 to 10.31; 75 participants; 1 study). FemPac 2008 was excluded due to concerns about incomplete participant follow‐up. DEBs were associated with significantly greater odds of primary vessel patency at 12 months (Analysis 2.3; OR 1.92, 95% CI 1.45 to 2.56; 882 participants; 3 studies) and two years (Analysis 3.2; OR 3.51, 95% CI 2.26 to 5.46; 406 participants; 2 studies).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 2 Primary vessel patency.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 12 Primary vessel patency (sensitivity analysis).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 3 Primary vessel patency.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 2 Primary vessel patency.

Secondary vessel patency

None of the included trials reported secondary vessel patency rates.

Late lumen loss

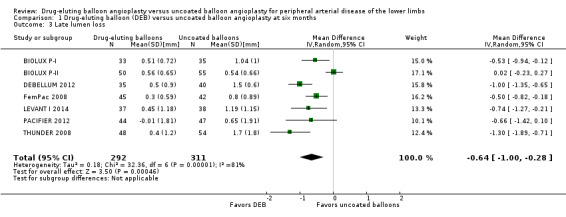

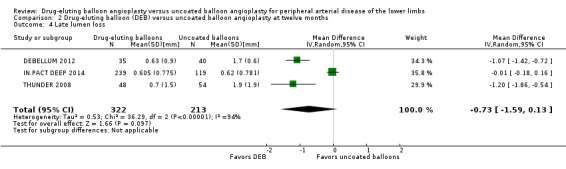

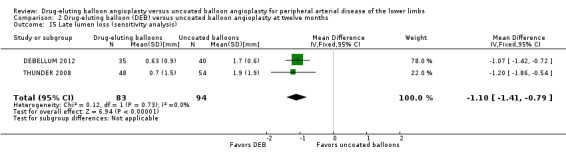

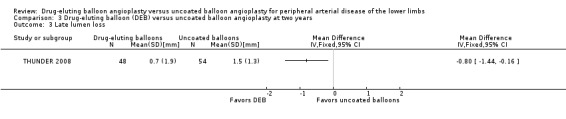

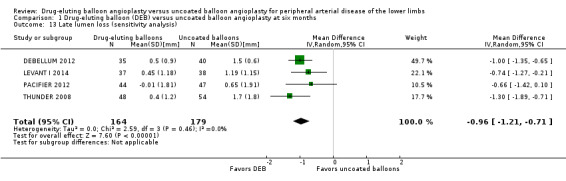

Participants treated with DEB were less likely to develop late lumen loss at six months compared with the control participants (Analysis 1.3; MD ‐0.64 mm, 95% CI ‐1.00 to ‐0.28; 603 participants; 7 studies). However, this advantage was lost after 12 months, primarily due to the inclusion of IN.PACT DEEP 2014 (Analysis 2.4; MD ‐0.73 mm, 95% CI ‐1.59 to 0.13; 535 participants; 3 studies), which was limited to infra‐popliteal vessels that were smaller than the femoropopliteal vessels studied in the other trials. When the analysis excluded IN.PACT DEEP 2014, there was less late lumen loss with DEBs compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty (Analysis 2.15; MD ‐1.10 mm, 95% CI ‐1.41 to ‐0.79; 177 participants; 2 studies). There was an advantage for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years (Analysis 3.3; MD ‐0.80 mm, 95% CI ‐1.44 to ‐0.16; 102 participants; 1 study).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 3 Late lumen loss.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 4 Late lumen loss.

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 15 Late lumen loss (sensitivity analysis).

3.3. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 3 Late lumen loss.

Exclusion of FemPac 2008, which reported late lumen losses as medians, and the BIOLUX P‐I and BIOLUX P‐II studies did not impact the late lumen loss advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.13; MD ‐0.96 mm, 95% CI ‐1.21 to ‐0.71; 343 participants; 4 studies).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 13 Late lumen loss (sensitivity analysis).

Target lesion revascularization

The DEB arm of the trials had a clear advantage in target lesion revascularization compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.4; OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.47; 603 participants; 7 studies), 12 months (Analysis 2.5; OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.51; 1900 participants; 11 studies), two years (Analysis 3.4; OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.44; 508 participants; 3 studies), and five years (Analysis 4.2; OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.51; 102 participants; 1 study).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 4 Target lesion revascularization.

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 5 Target lesion revascularization.

3.4. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 4 Target lesion revascularization.

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at five years, Outcome 2 Target lesion revascularization.

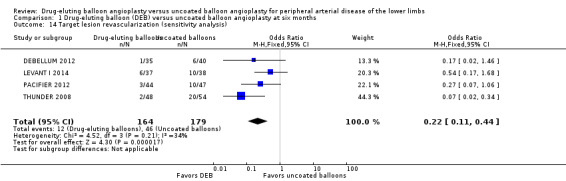

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 at six and 12 months did not impact the target lesion revascularization advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty (Analysis 1.14; OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.44; 343 participants; 4 studies at six months; Analysis 2.13; OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.61; 1640 participants; 8 studies at 12 months).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 14 Target lesion revascularization (sensitivity analysis).

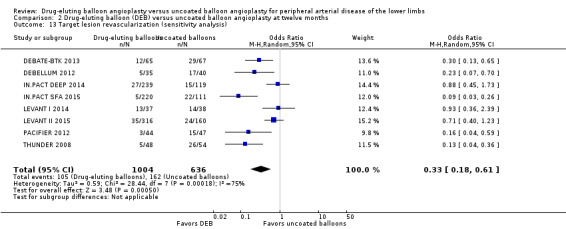

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 13 Target lesion revascularization (sensitivity analysis).

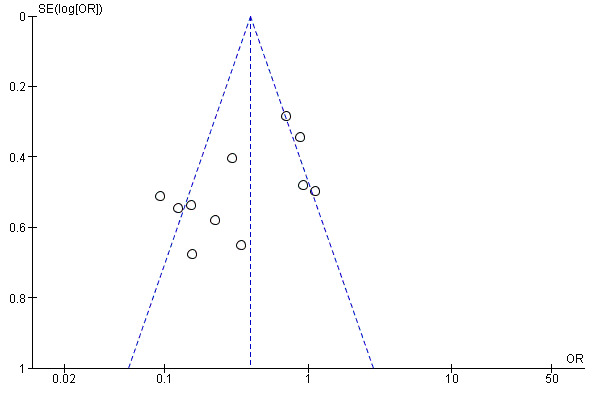

A funnel plot constructed to test for publication bias in target lesion revascularization at 12 months demonstrated asymmetry, which was consistent with the heterogeneity observed in the analysis (Chi2 test for heterogeneity P < 0.0001) (Figure 4).

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Drug‐eluting balloon versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at 12 months, outcome: 2.5 Target lesion revascularization.

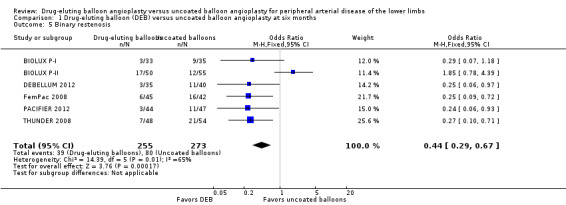

Binary restenosis rate

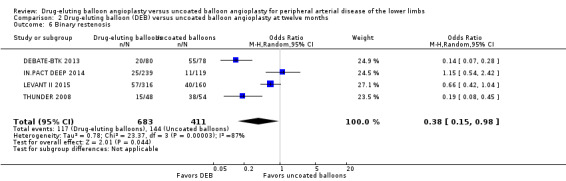

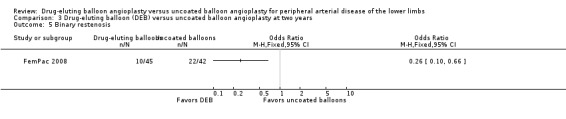

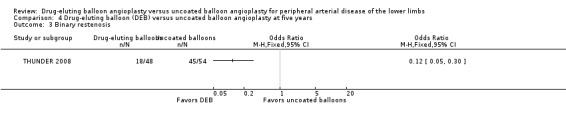

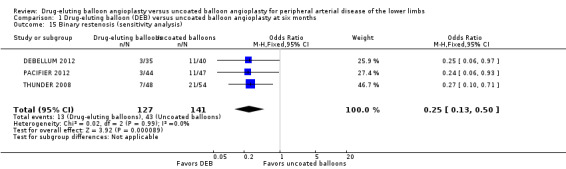

Participants treated with DEBs had significantly lower odds of developing binary restenosis compared with participants in the control group at six months (Analysis 1.5; OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.67; 528 participants; 6 studies), 12 months (Analysis 2.6; OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.98; 1094 participants; 4 studies), two years (Analysis 3.5; OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.66; 87 participants; 1 stud), and five years (Analysis 4.3; OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.30; 102 participants; 1 study).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 5 Binary restenosis.

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 6 Binary restenosis.

3.5. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 5 Binary restenosis.

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at five years, Outcome 3 Binary restenosis.

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 at six months did not impact the binary restenosis rate advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty (Analysis 1.15; OR 0.25, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.50; 268 participants; 3 studies).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 15 Binary restenosis (sensitivity analysis).

Death

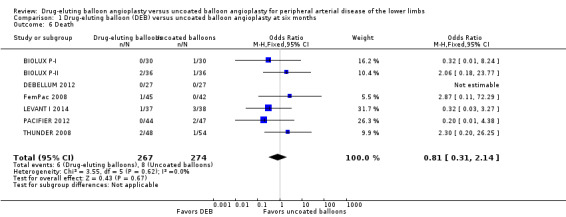

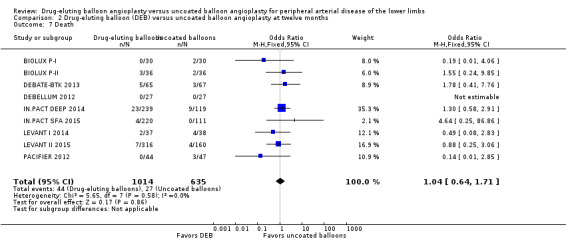

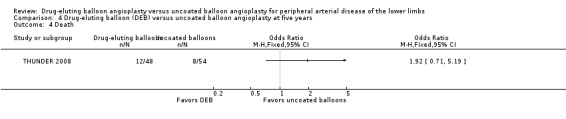

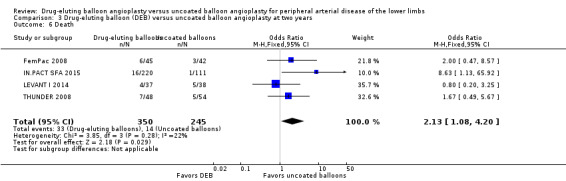

There was no significant difference in mortality between participants who underwent DEB or uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.6; OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.31 to 2.14; 541 participants; 7 studies), 12 months (Analysis 2.7; OR 1.04, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.71; 1649 participants; 9 studies), and five years (Analysis 4.4; OR 1.92, 95% CI 0.71 to 5.19; 102 participants; 1 study). At two years, uncoated balloon angioplasty had a slight mortality advantage compared with DEB (Analysis 3.6; OR 2.13, 95% CI 1.08 to 4.20; 595 participants; 4 studies).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 6 Death.

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 7 Death.

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at five years, Outcome 4 Death.

3.6. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 6 Death.

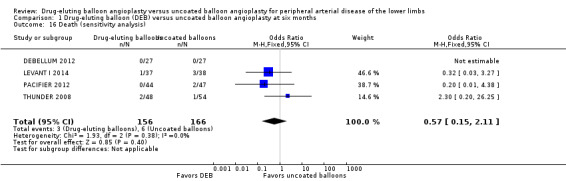

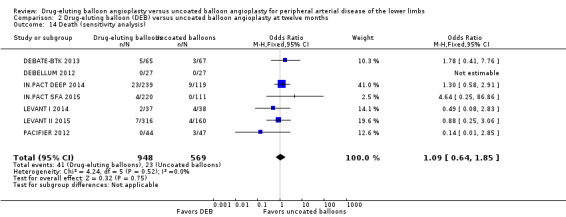

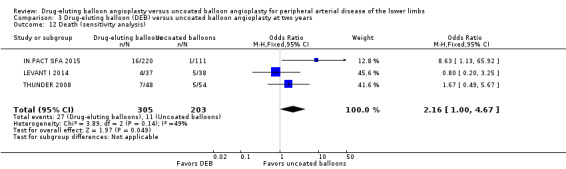

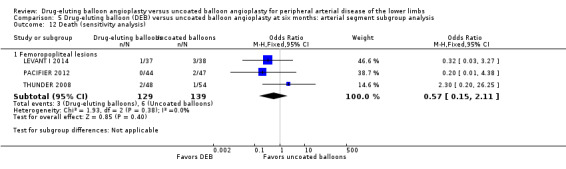

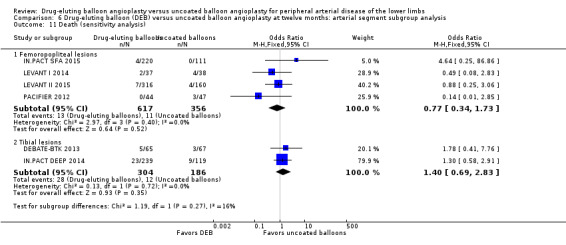

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 at six months, 12 months, and two years did not result in a significant difference in mortality between the treatment groups (Analysis 1.16; OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.11; 322 participants; 4 studies at six months; Analysis 2.14; OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.85; 1517 participants; 7 studies at 12 months; Analysis 3.12; OR 2.16, 95% CI 1.00 to 4.67; 508 participants; 3 studies at two years).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 16 Death (sensitivity analysis).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 14 Death (sensitivity analysis).

3.12. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 12 Death (sensitivity analysis).

Secondary outcomes

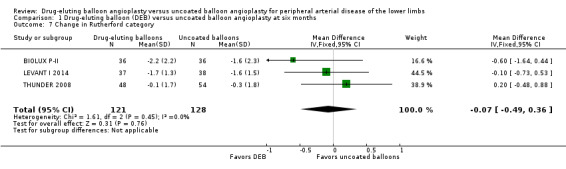

Change in Fontaine stage or Rutherford category of peripheral arterial disease

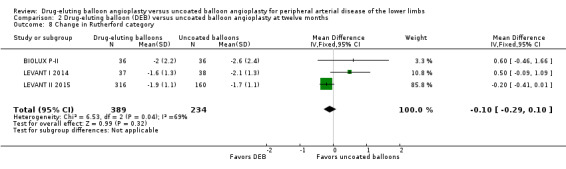

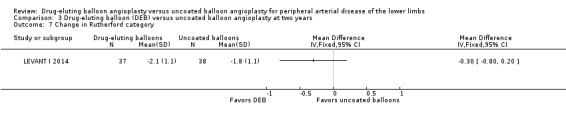

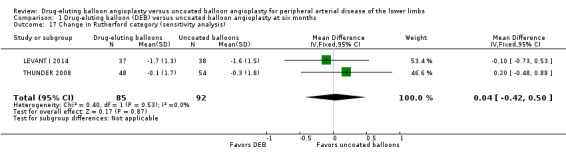

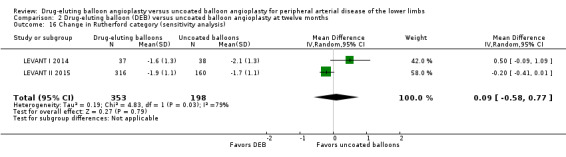

There was no significant difference in the change in Rutherford category between the DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty arms at six months (Analysis 1.7; MD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.36; 249 participants; 3 studies), 12 months (Analysis 2.8; MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.29 to 0.10; 623 participants; 3 studies), and two years (Analysis 3.7; MD ‐0.30, 95% CI ‐0.80 to 0.20; 75 participants; 1 study).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 7 Change in Rutherford category.

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 8 Change in Rutherford category.

3.7. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 7 Change in Rutherford category.

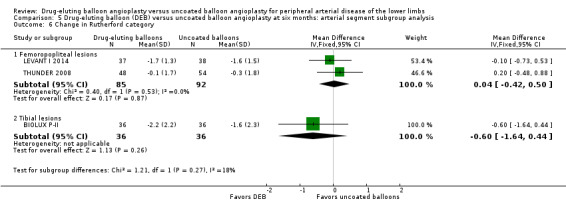

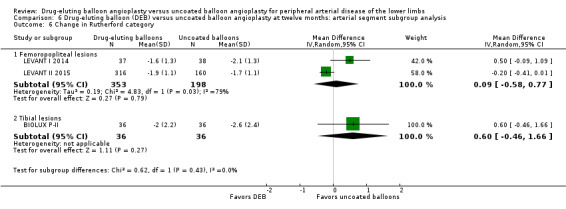

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐II at six and 12 months did not result in a significant change in Rutherford category from baseline between the two treatment groups (Analysis 1.17; MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 0.50; 177 participants; 2 studies at six months; Analysis 2.16; MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 0.77; 551 participants; 2 studies at 12 months).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 17 Change in Rutherford category (sensitivity analysis).

2.16. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 16 Change in Rutherford category (sensitivity analysis).

One trial reported the Fontaine stage rather than the Rutherford classification system (DEBELLUM 2012). Our analysis did not include these data, however, because the authors reported the Fontaine class at six and 12 months rather than the change in Fontaine class from baseline. At six months, the DEB participants were 92% Fontaine class I, 8% class IIa, and 0% class IIb or III, versus uncoated balloon angioplasty participants who were 67% class I, 13% class IIa, 7% class IIb, and 13% class III. At 12 months, the DEB participants were 77% class I, 8% class IIa, 15% class IIb, and 0% class III, versus uncoated balloon angioplasty participants who were 60% class I, 13% class IIa, 13% class IIb, and 13% class III.

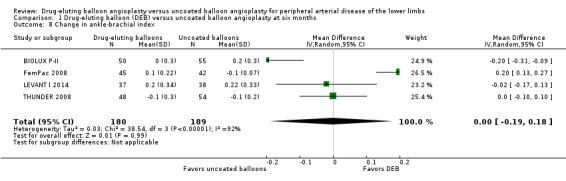

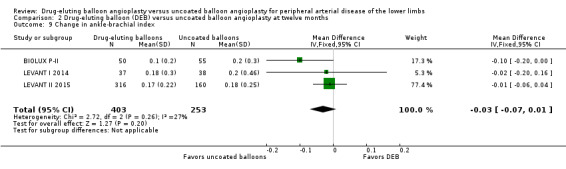

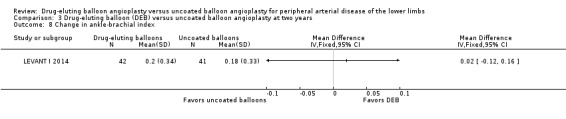

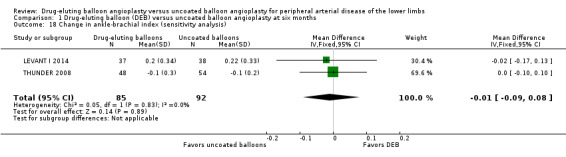

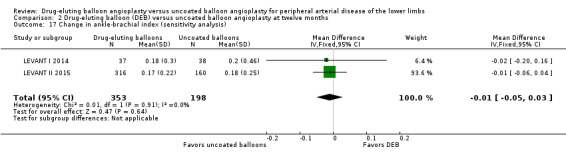

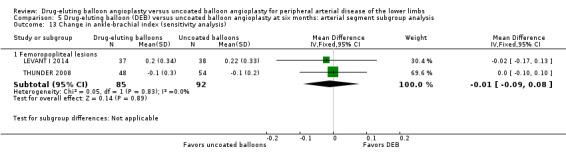

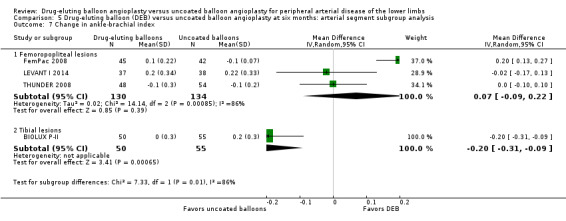

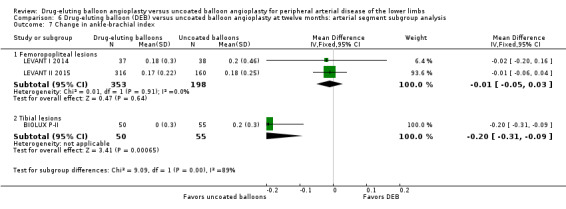

Change in ankle‐brachial index

There was no significant advantage for DEB when evaluating change in ABI at six months (Analysis 1.8; MD ‐0.00, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.18; 369 participants; 4 studies), 12 months (Analysis 2.9; MD ‐0.03, 95% CI ‐0.07 to 0.01; 656 participants; 3 studies), and two years (Analysis 3.8; MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.12 to 0.16; 83 participants; 1 study).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 8 Change in ankle‐brachial index.

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 9 Change in ankle‐brachial index.

3.8. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 8 Change in ankle‐brachial index.

Exclusion of FemPac 2008, which reported changes in ABI as medians, and BIOLUX P‐II demonstrated no advantage in ABI change for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six and 12 months (Analysis 1.18; MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.08; 177 participants; 2 studies at six months; Analysis 2.17; MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.03; 551 participants; 2 studies at 12 months).

1.18. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 18 Change in ankle‐brachial index (sensitivity analysis).

2.17. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 17 Change in ankle‐brachial index (sensitivity analysis).

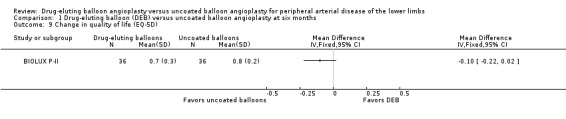

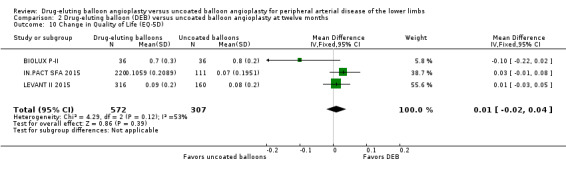

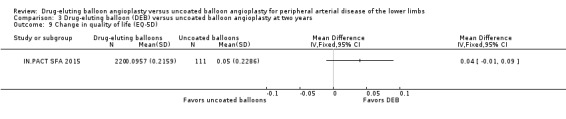

Change in quality of life scores

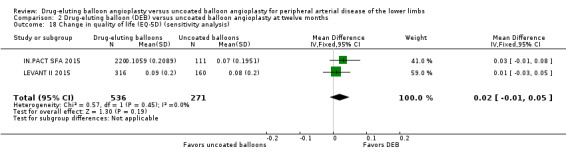

The Euro‐Qol Group 5‐Dimension Self‐Report Questionnaire (EQ‐5D) QoL scores were reported at six months (BIOLUX P‐II), 12 months (BIOLUX P‐II; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT II 2015) and two years (IN.PACT SFA 2015). There was no significant difference in the change of EQ‐5D scores between the DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty arms (Analysis 1.9; MD ‐0.10, 95% CI ‐0.22 to 0.02; 72 participants; 1 study at six months, Analysis 2.10; MD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.02 to 0.04; 879 participants; 3 studies at 12 months; Analysis 3.9; MD 0.04; 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.09; 331 participants; 1 study at two years).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 9 Change in quality of life (EQ‐5D).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 10 Change in Quality of Life (EQ‐5D).

3.9. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 9 Change in quality of life (EQ‐5D).

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐II at 12 months did not result in a significant change in QoL scores from baseline between the two treatment groups (Analysis 2.18; MD 0.02, 95% CI ‐0.01 to 0.05; 807 participants; 2 studies).

2.18. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 18 Change in quality of life (EQ‐5D) (sensitivity analysis).

LEVANT II 2015 also reported 36‐item Short Form (SF‐36) Physical and Mental component scores at 12 months but demonstrated no significant difference. The MD and standard deviation (SD) in the Physical component score between the intervention and control arms was 0.6 ± 11 (95% CI ‐1.7 to 2.9). Similarly, the difference in the Mental component score between the intervention and control arms was ‐0.2 ± 12.8 (95% CI ‐2.9 to 2.5).

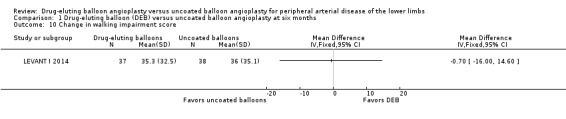

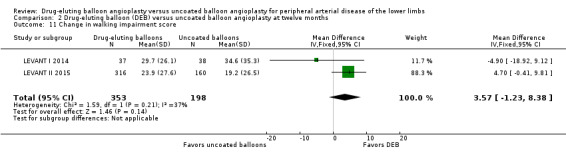

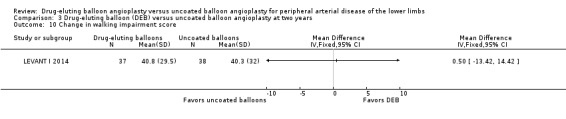

Change in functional walking ability

Two trials assessed the change in functional walking ability using the WIQ (LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015). There were no significant differences in WIQ scores between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 1.10; MD ‐0.70, 95% CI ‐16.00 to 14.60; 75 participants; 1 study), 12 months (Analysis 2.11; MD 3.57, 95% CI ‐1.23 to 8.38; 513 participants; 2 studies), and two years (Analysis 3.10; MD 0.50, 95% CI ‐13.42 to 14.42; 75 participants; 1 study).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months, Outcome 10 Change in walking impairment score.

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months, Outcome 11 Change in walking impairment score.

3.10. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at two years, Outcome 10 Change in walking impairment score.

Subgroup analysis

Arterial segments

Seven trials included only femoropopliteal arterial lesions (BIOLUX P‐I; FemPac 2008; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT I 2014; LEVANT II 2015; PACIFIER 2012; THUNDER 2008), and three trials included only tibial arterial lesions (BIOLUX P‐II; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; IN.PACT DEEP 2014). DEBELLUM 2012 included both femoropopliteal and tibial lesions, but did not stratify the outcomes by type of arterial segment and as such was excluded from this subgroup analysis. Data were available to permit subgroup analysis by arterial segment at six and 12 months for the following outcomes: amputation, late lumen loss, target lesion revascularization, binary restenosis, death, change in Rutherford category, and change in ABI.

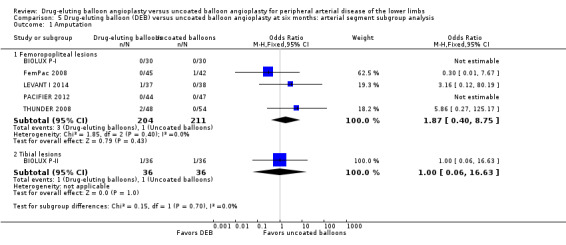

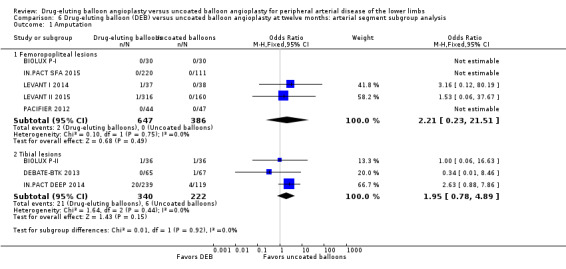

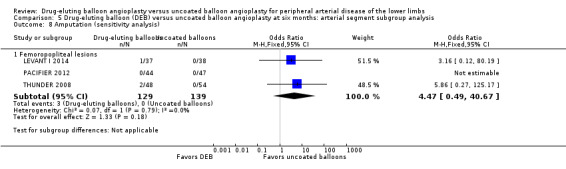

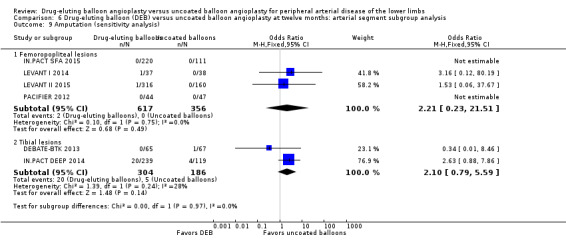

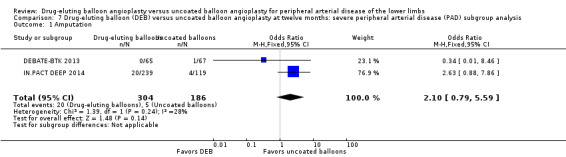

Amputation

There was no significant difference in the incidence of amputation by arterial segment at six months (Analysis 5.1; OR 1.87, 95% CI 0.40 to 8.75; 415 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 1.00, 95% CI 0.06 to 16.63; 72 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.70) or 12 months (Analysis 6.1; OR 2.21, 95% CI 0.23 to 21.51; 1033 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 1.95, 95% CI 0.78 to 4.89; 562 participants; 3 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.92).

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 1 Amputation.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 1 Amputation.

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I and FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in the incidence of amputation for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.8; OR 4.47, 95% CI 0.49 to 40.67; 268 participants; 3 studies for femoropopliteal vessels) and 12 months (Analysis 6.9; OR 2.21, 95% CI 0.23 to 21.51; 973 participants; 4 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 2.10, 95% CI 0.79 to 5.59; 490 participants; 2 studies for tibial vessels).

5.8. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 8 Amputation (sensitivity analysis).

6.9. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 9 Amputation (sensitivity analysis).

Late lumen loss

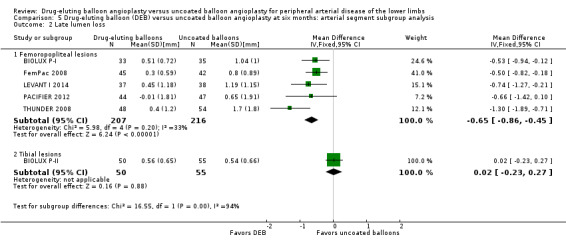

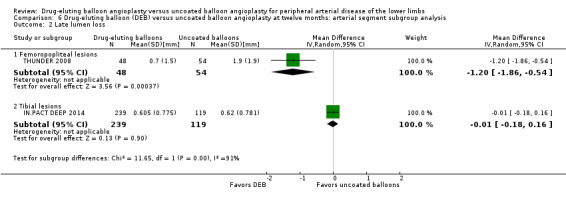

Comparison of the arterial segment subgroups demonstrated a significant difference in late lumen loss favoring the DEB arm of the femoropopliteal group at six months (Analysis 5.2; MD ‐0.65 mm, 95% CI ‐0.86 to ‐0.45; 423 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD 0.02 mm, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.27; 105 participants; 1 study tibial vessels; P < 0.0001) and 12 months (Analysis 6.2; MD ‐1.20 mm, 95% CI ‐1.86 to ‐0.54; 102 participants; 1 study for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD ‐0.01 mm, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.16; 358 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.0006).

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 2 Late lumen loss.

6.2. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 2 Late lumen loss.

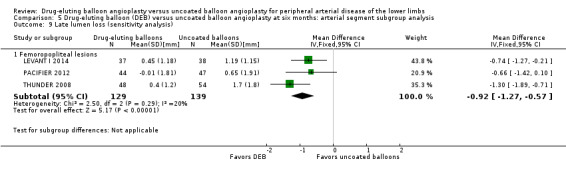

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I and FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in the late lumen loss advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.9; MD ‐0.92 mm, 95% CI ‐1.27 to ‐0.57; 268 participants; 3 studies for femoropopliteal vessels).

5.9. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 9 Late lumen loss (sensitivity analysis).

Given the intrinsic lumen diameter differences between femoropopliteal and tibial vessels, the implications of this analysis are limited.

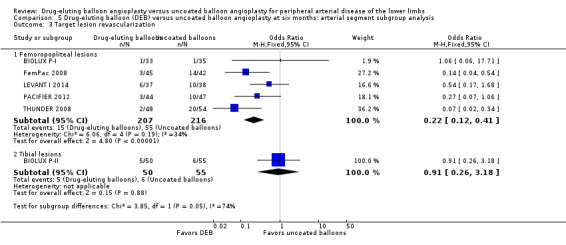

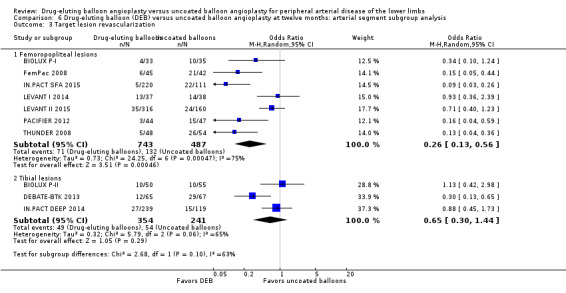

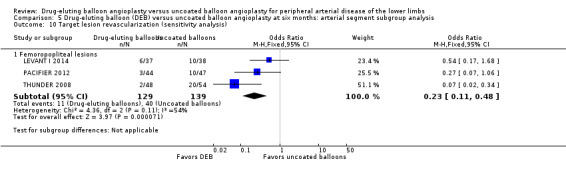

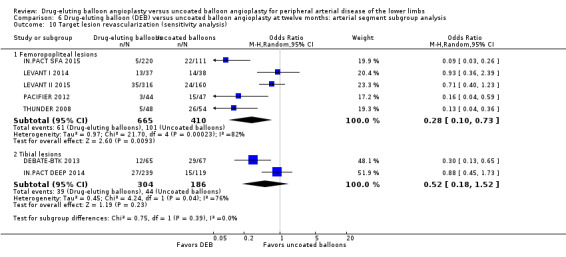

Target lesion revascularization

Comparison of the arterial segment subgroups demonstrated a significant advantage in target lesion revascularization for the DEB arm of the femoropopliteal subgroup, but there was no significant difference between the DEB and control arms of the tibial subgroup at six months (Analysis 5.3; OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.41; 423 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.26 to 3.18; 105 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.05) and 12 months (Analysis 6.3; OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.13 to 0.56; 1230 participants; 7 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.44; 595 participants; 3 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.10).

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 3 Target lesion revascularization.

6.3. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 3 Target lesion revascularization.

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in the target lesion revascularization advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.10; OR 0.23, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.48; 268 participants; 3 studies for femoropopliteal vessels) and 12 months (Analysis 6.10; OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.73; 1075 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.52; 490 participants; 2 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.23).

5.10. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 10 Target lesion revascularization (sensitivity analysis).

6.10. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 10 Target lesion revascularization (sensitivity analysis).

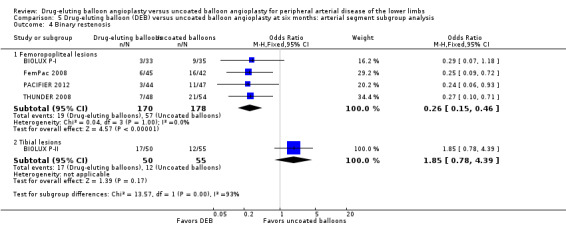

Binary restenosis

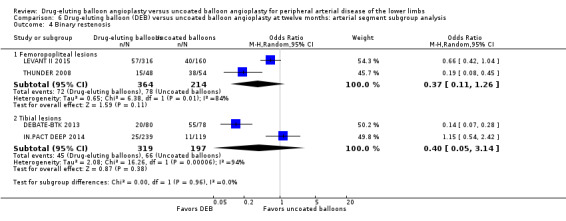

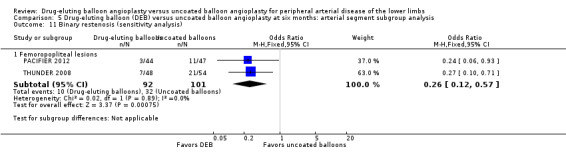

There was a significant advantage for DEB in the incidence of binary femoropopliteal vessel restenosis compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.4; OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.15 to 0.46; 348 participants; 4 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 1.85, 95% CI 0.78 to 4.39; 105 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.0002). However, this effect was not sustained at 12 months (Analysis 6.4; OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.11 to 1.26; 578 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.05 to 3.14; 516 participants; 2 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.96).

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 4 Binary restenosis.

6.4. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 4 Binary restenosis.

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I and FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in the binary restenosis advantage of DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.11; OR 0.26, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.57; 193 participants; 2 studies).

5.11. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 11 Binary restenosis (sensitivity analysis).

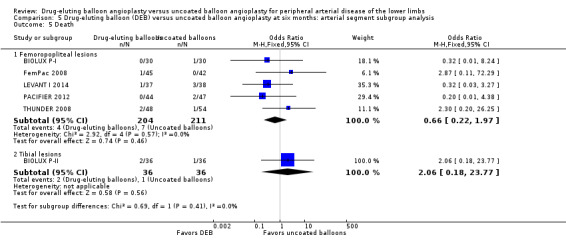

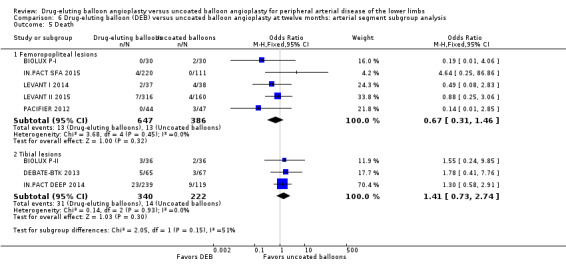

Death

Comparison of the arterial segment subgroups demonstrated no difference in mortality between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.5; OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.97; 415 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 2.06, 95% CI 0.18 to 23.77; 72 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.41) and 12 months (Analysis 6.5; OR 0.67, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.46; 1033 participants; 5 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 1.41, 95% CI 0.73 to 2.74; 562 participants; 3 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.15).

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 5 Death.

6.5. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 5 Death.

Exclusion of BIOLUX P‐I, BIOLUX P‐II, and FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in mortality for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.12; OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.15 to 2.11; 268 participants; 3 studies for femoropopliteal vessels) and 12 months (Analysis 6.11; OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.73; 973 participants; 4 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus OR 1.40, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.83; 490 participants; 2 studies for tibial vessels; P = 0.27).

5.12. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 12 Death (sensitivity analysis).

6.11. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 11 Death (sensitivity analysis).

Change in Rutherford category

Comparison of the arterial segment subgroups demonstrated no difference in Rutherford category between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.6; MD 0.04, 95% CI ‐0.42 to 0.50; 177 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD ‐0.60, 95% CI ‐1.64 to 0.44; 72 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.27) and 12 months (Analysis 6.6; MD 0.09, 95% CI ‐0.58 to 0.77; 551 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD 0.60, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 1.66; 72 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.43).

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 6 Change in Rutherford category.

6.6. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 6 Change in Rutherford category.

Exclusion of FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in Rutherford category between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months (Analysis 5.13; MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.08; 177 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels).

5.13. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 13 Change in ankle‐brachial index (sensitivity analysis).

Change in ankle‐brachial index

There was a significant change in ABI advantage for uncoated balloon angioplasty compared with DEB in tibial vessels, but this advantage was not seen in femoropopliteal vessels at six months (Analysis 5.7; MD 0.07, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.22; 264 participants; 3 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.31 to ‐0.09; 105 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.007) and 12 months (Analysis 6.7; MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.05 to 0.03; 551 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels versus MD ‐0.20, 95% CI ‐0.31 to ‐0.09; 105 participants; 1 study for tibial vessels; P = 0.003).

5.7. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at six months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 7 Change in ankle‐brachial index.

6.7. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: arterial segment subgroup analysis, Outcome 7 Change in ankle‐brachial index.

Exclusion of FemPac 2008 did not result in a significant change in ABI between DEB and uncoated balloon angioplasty for femoropopliteal vessels at six months (Analysis 5.13; MD ‐0.01, 95% CI ‐0.09 to 0.08; 177 participants; 2 studies for femoropopliteal vessels).

Severity of peripheral arterial disease

Two trials included only participants with CLI (Rutherford class 4 or greater) (DEBATE‐BTK 2013; IN.PACT DEEP 2014). The other trials included participants with varying degrees of PAD but did not stratify the outcomes by severity of PAD and as such were excluded from this subgroup analysis. Data were only available to permit subgroup analysis for participants with CLI at 12 months for the following outcomes: amputation, late lumen loss, target lesion revascularization, binary restenosis, and death.

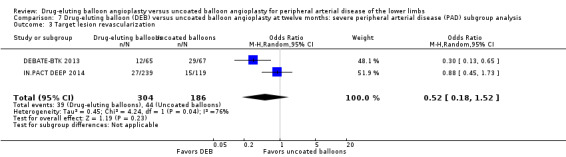

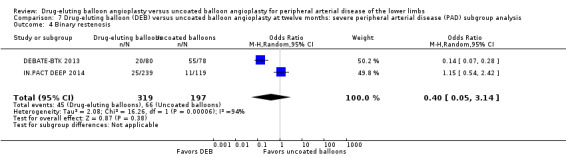

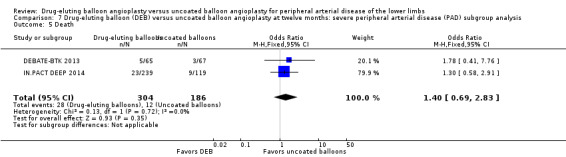

There was no significant difference in the incidence of amputation between the DEB and control arms in participants with CLI (Analysis 7.1; OR 2.10, 95% CI 0.79 to 5.59; 490 participants; 2 studies). Similarly, there was no difference in late lumen loss (Analysis 7.2; MD ‐0.01 mm, 95% CI ‐0.18 to 0.16; 358 participants; 1 study), target lesion revascularization (Analysis 7.3; OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.18 to 1.52; 490 participants; 2 studies); binary restenosis (Analysis 7.4; OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.05 to 3.14; 516 participants; 2 studies); or death (Analysis 7.5; OR 1.40, 95% CI 0.69 to 2.83; 490 participants; 2 studies), between the DEB and control arms in participants with CLI.

7.1. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) subgroup analysis, Outcome 1 Amputation.

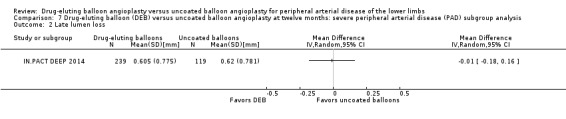

7.2. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) subgroup analysis, Outcome 2 Late lumen loss.

7.3. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) subgroup analysis, Outcome 3 Target lesion revascularization.

7.4. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) subgroup analysis, Outcome 4 Binary restenosis.

7.5. Analysis.

Comparison 7 Drug‐eluting balloon (DEB) versus uncoated balloon angioplasty at twelve months: severe peripheral arterial disease (PAD) subgroup analysis, Outcome 5 Death.

Discussion

Summary of main results

DEB angioplasty was associated with improved primary vessel patency and late lumen loss for up to two years and target lesion revascularization and binary restenosis rates for up to five years. However, there was no advantage for DEB in clinical endpoints such as amputation, change in Rutherford class, QoL scores, functional walking ability, or mortality compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty. On subgroup analysis, DEB angioplasty showed improved late lumen loss, target lesion revascularization, and binary restenosis for up to six months, and late lumen loss and target lesion revascularization for up to 12 months in femoropopliteal vessels. However, DEB angioplasty of tibial vessels was not superior to uncoated balloon angioplasty in any domains. Furthermore, DEB angioplasty was not superior to uncoated balloon angioplasty in people with CLI.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

We included 11 prospective randomized trials that were designed to compare clinical differences after DEB versus uncoated balloon angioplasty. The trial endpoints in all of the included studies were clinically relevant, patient‐oriented, and included a widely utilized mix of anatomic and clinical endpoints, which makes our findings clinically applicable.

While the trials had several limitations (listed in Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), most were conducted at high‐volume centers with experience in device‐efficacy trials. Three trials were at a high risk of bias and their impact was assessed with serial sensitivity analyses, but in most instances their exclusion had no significant impact (BIOLUX P‐I; BIOLUX P‐II; FemPac 2008).

A limitation of our subgroup analysis was that there were only three trials available for the tibial vessel analysis (BIOLUX P‐II; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; IN.PACT DEEP 2014), and only two trials for the CLI subgroup analysis (DEBATE‐BTK 2013; IN.PACT DEEP 2014). As such, it is unclear whether the subgroup analysis results were due to the effects of tibial arteries or CLI. Furthermore, we were unable to carry out any subgroup analyses by severity of PAD because none of the trials reported their outcomes by degree of severity.

Finally, several of the ongoing trials (listed in Characteristics of ongoing studies table) have not published their results in peer‐reviewed publications despite having completed enrolment for several years. Two of those trials started enrolling participants in 2008 (Advance 18PTX Balloon Catheter Study; PICCOLO). This is concerning for possible reporting bias if those privately sponsored trials were not published because of unfavorable results. We have attempted to contact the authors of all ongoing trials with limited success.

We have identified several trials that are still enrolling participants or have not published their results, and several of the studies included in our analysis have not yet published their long‐term results. As such, future versions of this review will hopefully be able to provide better evidence for the efficacy of DEB in managing lower‐limb ischemia.

Quality of the evidence

There was heterogeneity in the frequency of stent deployment and the type and duration of antiplatelet therapy between trials. Using GRADE assessment criteria, the quality of the evidence presented was low for the outcome of target lesion revascularization; moderate for binary restenosis and change in Rutherford category; and high for amputation, primary vessel patency, death, and change in ABI.

The included studies were powered to detect anatomic endpoints that were measured according to angiographic and ultrasound imaging criteria. As such, caution must be taken in interpreting the clinical endpoint results, since the included studies were unlikely to be powered to specifically assess those endpoints.

Risk of selection bias was low in most of the studies. Conversely, performance bias was uniformly high because of the difficulty in blinding operators to the interventions. However, this, is a limitation intrinsic to most surgical and procedural trials. The included studies mostly took adequate steps to address this limitation by implementing measures, such as independent core lab evaluation, to avoid detection bias. While follow‐up compliance was good in half of the included studies, most studies were at low risk for reporting bias.

There was a substantial amount of heterogeneity in the studies that may have biased the analysis. First, while the DEB in all of the included studies employed the mitotic inhibitor paclitaxel, the medication doses varied and were not consistently reported. Second, the DEB devices in the studies employed different drug carriers, as described in Schnorr 2013. The effect of different drug carriers on the results was not clear. Third, the type and duration of antiplatelet therapy differed between trials. Finally, the wide use of stenting in most of the included trials invariably affected the outcomes, but few data were available on the stented subgroups of participants.

It is unclear what criteria were used to determine the need for target lesion revascularization, resulting in heterogeneity between studies reporting this outcome. While most studies stated that target lesion revascularization was carried out for clinically driven indications (BIOLUX P‐I; DEBATE‐BTK 2013; DEBELLUM 2012; IN.PACT DEEP 2014; IN.PACT SFA 2015; LEVANT II 2015; PACIFIER 2012), those indications were not defined or explained.

Those limitations notwithstanding, our analysis demonstrates an advantage for DEB compared with uncoated balloon angioplasty in the management of PAD for up to two years of follow‐up in several anatomic endpoints. There is insufficient evidence to support an advantage for either treatment modality beyond two years. However, with many other ongoing or unreported studies, short‐ and long‐term data will hopefully become available to assess the efficacy of this treatment modality better in the near future.

Potential biases in the review process