Abstract

We examined the relationship between moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity using an online survey via Mechanical Turk. In order to determine how moral foundations contribute to empathic traits and moral identity, we performed classical correlation analysis as well as Bayesian correlation analysis, Bayesian ANCOVA, and Bayesian regression analysis. Results showed that individualizing foundations (harm/care, fairness/reciprocity) and binding foundations (ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, purity/sanctity) had various different relationships with empathic traits. In addition, the individualizing versus binding foundations showed somewhat reverse relationships with internalization and symbolization of moral identity. This suggests that moral foundations can contribute to further understanding of empathic traits and moral identity and how they relate to moral behavior in reality. We discuss the implications of these results for moral educators when starting to teach students about moral issues.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12144-021-02372-5.

Keywords: Moral foundations, Empathy, Moral identity, Moral behavior, Bayesian analysis

The fundamental issue in the field of moral psychology referred to as the “gappiness problem” (Darnell et al., 2019) is related to how to bridge the gap between moral judgment and moral behavior. According to prior research, moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity play fundamental roles in moral judgment and how to fill the gap between moral judgment and behavior (Hoffman, 2000; Smith et al., 2014). Since all of these factors have a unique relationship with moral behavior, and it has been proposed that the solution to the gappiness problem likely will not be any one factor alone (Darnell et al., 2019), it would be helpful to understand the relationship between factors that have shown some degree of promise in filling the gap. In order to gain a comprehensive understanding of this issue, we first reviewed theoretical frameworks about each of these factors and then moved on to how they are associated with each other. Next, we empirically examined the relationship between the factors by conducting a Bayesian analysis with cross-sectional data.

Moral Foundations Theory

Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) was developed by Haidt and Joseph (2004) in order to provide a pluralistic theory of the intuitions and values that people use to make decisions about how to behave morally. Haidt and Joseph (2004) surveyed five major theoretical pieces examining universal components of morality, cultural variations in morality, and evolutionary underpinnings of morality in order to determine what common values were found in all of the perspectives. From this, they suggested five foundations that people employ to be moral; these are: harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity. MFT proposes that, to a degree, everybody has a sense of morality at birth related to these five intuitions, but these moral values are strongly influenced by experience and one’s environment (Graham et al., 2013). Graham et al. (2013) state that the morals somebody is born with should be thought of something like a first draft that will be rewritten time and time again throughout one’s life.

According to this theory, most individuals have intuitions connected to these foundations that provoke their reaction when encountering moral issues. Harm/care entails having a negative reaction to seeing others being harmed, fairness/reciprocity places value on equal relationships which do not involve cheating, ingroup/loyalty prioritizes acting in accord with one’s ingroup and feeling negatively towards those who disrupt it somehow, authority/respect places value on mutual respect in relationships, and purity/sanctity entails having negative feelings towards impure behavior that strays from the norm (Haidt & Graham, 2007; Haidt & Joseph, 2004). These foundations are broken down into two categories, which are individualizing and binding. Harm/care and fairness/reciprocity are classified as individualizing foundations because they benefit the individual and focus on autonomy whereas ingroup/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity are classified as binding foundations because they focus more on community and the good of the group.

When examining how individuals differently use these foundations to assess moral issues, political identity is one factor that has provided key insights as to how endorsing different foundations influences moral thought. For example, Haidt and Graham (2007) found that political identity was the most significant explanatory variable for predicting the moral foundations among other categorical variables such as age, education level, gender, etc. It is commonly found that liberals rely on only harm/care and fairness/reciprocity while conservatives typically employ all five foundations more evenly when considering what is moral and how to behave morally (Graham et al., 2009; Silver & Silver, 2017). This distinction offers one explanation for why some individuals view certain moral issues as more relevant than others and suggests a significant link between moral values and political identity (Graham et al., 2009).

This is important when considering the connection between moral thought and moral action, since whether an individual embraces individualizing or binding foundations may significantly influence their moral behavior. For example, as Smith et al. (2014) discuss, endorsing the binding foundations has a potential dark side since placing value on acting in accord with the in-group may justify immoral behavior towards a member of the out-group. This effect was highlighted in a recent study on the COVID-19 pandemic, which found that strongly endorsing binding foundations and having faith in President Trump, the current president at the time of the study, resulted in defying recommendations such as social distancing (Graham et al., 2020). Since individuals that score high on binding foundations are more likely to feel the need to be a part of a group and fit in, this may result in putting even more trust in authority figures during times of crisis.

Another study that explored the effects of binding foundations and the COVID-19 pandemic found that there was an indirect link between COVID-19 concerns and prejudice against migrants, which was mediated by need for cognitive closure (NCC) and respect for authority (Bianco et al., 2021). In fact, previous studies have shown a significant positive relationship between binding foundations and NCC (Baldner et al., 2018). Individuals who have NCC want absolute answers in order to avoid dealing with uncertainty and are willing to overlook contradictory information to maintain closure. This suggests that binding foundations may be more appealing to some individuals that prefer to rely on group norms and authority figures for answers instead of contemplating complex issues such as harm and fairness.

These previous studies demonstrate the real-world implications for how people rely on moral foundations to make decisions. It is important to note that previous research has shown promise in appealing to whichever moral foundations somebody endorses in order to receive support on moral issues. For example, even though environmental issues spark much disagreement between conservatives and liberals, one previous study found that when the issues were framed in terms of purity, instead of harm as it usually is, differences between the groups were significantly minimized (Feinberg & Willer, 2013). In order to better understand how prosocial behavior can result from the endorsement of either binding or individualizing foundations, it is important to understand how other moral characteristics influence the foundations.

Empathy and Morality

In general, empathy refers to how an individual responds to the experiences of others (Davis, 1983). Although there has been focus on either affective or cognitive responses over the years, it is now generally accepted that multiple aspects of individuals’ reactions to others, including emotional (e.g., emotion contagion), motivational (e.g., empathic concern), and cognitive aspects (e.g., affective perspective taking) are important for a complete understanding of empathy (Decety & Cowell, 2014).

This multidimensional approach to studying empathy was originally expanded upon by Davis (1983) who suggested four components of empathy that are still commonly used: empathic concern (EC), perspective taking (PT), personal distress (PD), and fantasy (FS). EC involves a concern for others who are experiencing difficulties, PT involves identifying with another person’s thoughts and considering their point of view, PD involves being overwhelmed by the experiences of others, and FS involves imagining oneself experiencing the thoughts and feelings of fictitious characters.

Although these aspects are all related to empathy, the mechanisms and functions they serve can be quite different, which is why it is important to differentiate between them, especially when considering issues of morality. In general, among the four subcomponents, only EC and PT have been deemed to be conducive to moral and prosocial behavior while PD and FS have not. Because EC is about genuine concern for others’ pain and wellbeing and PT is required to consider diverse perspectives to make appropriate behavioral decisions, these two constructs are inseparable from morality and prosociality (Decety & Cowell, 2014). Findings from previous studies support such a point. EC and PT positively predict complying with preventive measures during COVID-19 (Galang et al., 2021) and diverse moral functioning indicators, such as developed moral reasoning and prosocial purpose (Han et al., 2020). On the other hand, the two components are negatively associated with antisocial behavior, such as criminal behavior (Martinez et al., 2014).

Interestingly, PD is reportedly negatively associated with morality in several studies. Darnell et al. (2019) suggests that because PD is a self-oriented emotion, it does not produce moral behavior but rather other-oriented emotions such as sympathy or EC do. Along with this, empathy has been found to prevent moral disengagement whereas PD has been found to promote moral disengagement (Paciello et al., 2013). Similarly, additional previous studies have also reported negative association between PD and morality and prosociality in diverse domains, such as compassion (Thomas, 2013) and volunteering (Carlo et al., 1999).

Finally, compared with the other empathy subcomponents, FS shows a relatively weaker association with moral functioning. For instance, in terms of correlation coefficients, FS showed weaker correlation with moral reasoning, moral disengagement, and prosocial purpose (Han et al., 2020). Likewise, in other previous studies, FS was not significantly associated with moral identity (Black & Reynolds, 2016), moral agency (Black, 2016), moral decision-making (Gleichgerrcht & Young, 2013), or self-reported moral behavior (Strobel et al., 2017). Given FS is about how to deal with pains and difficulties experienced by imaginary beings, not real people or animals (Davis, 1983), FS would be less important in predicting moral functioning compared with other subcomponents, which address more realistic issues.

Although the previous studies have examined the relationship between the subcomponents of empathy and moral functioning, none of them have focused on the association between moral foundations and different empathic traits. Given that different subcomponents reported association with moral functioning indicators in different directions as reported in the studies, they would also be differently associated with different moral foundations. Such a point might need to be examined with an empirical investigation.

Moral Identity

Moral identity refers to how important being a moral person is to an individual’s overall identity (Hardy & Carlo, 2005). This is considered important for moral behavior because it has been suggested that if someone has a strong sense of who they are and their moral compass is important to their identity, they will be motivated to act morally in order to stay consistent with their identity (Aquino et al., 2009; Blasi, 1983; Damon & Gregory, 1997).

The two components of moral identity that Aquino and Reed (2002) have conceptualized and most of the work on moral identity has embraced (Jennings et al., 2015) are internalization and symbolization. Internalization refers to the private experience of moral identity that others do not necessarily see or know about. Symbolization, on the other hand, refers to the outward expression of moral identity, such as that reflected in actions or personal belongings. Internalization has been shown to have implications for moral behavior, such as in Winterich et al.’s study ( 2012) where donation behavior increased once the charity’s moral foundations aligned with the participants’ values, but only for those participants with high internalization of moral identity. However, other studies have found symbolization to increase charitable giving since it is an outward way to demonstrate a sense of moral identity (Reynolds & Ceranic, 2007). In addition to self-report survey measures, other methodologies have also been used to explore moral identity, such as Colby and Damon’s (1992) study, in which they interviewed individuals who were considered moral exemplars and investigated how their sense of self and morals intertwined. They found that for these highly moral individuals, their sense of self and morality were closely aligned. These findings suggest a significant link between moral identity and moral behavior, however it is still unclear exactly how moral identity influences behavior and its relationship to other factors, such as moral foundations and empathic traits.

As mentioned previously, there is concern about a possible dark side of the binding foundations. Importantly, Smith et al. (2014) found that moral identity can play a significant role in mitigating these potential risks by expanding individuals’ moral circle. This suggests a possible avenue for promoting moral behavior regardless of which foundations somebody endorses by expanding who is considered when deciding how to act. Still, this study only utilized the individualization subcomponent of moral identity, so further work investigating the relationship of the foundations with symbolization is necessary.

Connecting Moral Foundations Theory, Empathic Traits, Moral Identity, and the “Gappiness” Problem

Due to the previously mentioned “gappiness” problem (Darnell et al., 2019) in the field, it would be beneficial to explore how the aforementioned three factors, moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity, have been considered to influence moral judgment and moral behavior. One previous study that addressed the relationship between moral foundations and moral judgment reported that individualizing foundations are significantly associated with more sophisticated moral reasoning (Baril & Wright, 2012; Glover et al., 2014; Han & Dawson, 2021). It is plausible to see such an association, because sophisticated moral reasoning, moral reasoning based on the postconventional schema, requires a capability to evaluate and deliberate upon existing social norms and conventions in a critical manner based on universal moral principles (Choi et al., 2020; Rest et al., 1999). Additional study findings support the point by demonstrating that postconventional moral reasoning is negatively associated with the endorsement of authority and tradition (Curtis et al., 1988; Lan et al., 2008) while positively associated with the endorsement of core moral principles, such as harm prevention and caring (Fang et al., 2017; Myyrya et al., 2010).

These studies have demonstrated the nature of sophisticated moral judgment in terms of its relationship with different moral foundations. This has provided researchers with ideas about how different moral foundations differently contribute to the formation of moral judgment and its development. However, none of them have paid sufficient attention to empathy or moral identity. Because scholars have been concerned about the gap between moral judgment and action and many of them have examined empathy and moral identity as candidate constructs to fill the gap, examining how empathy and moral identity are associated with moral foundations would be informative.

Empathy and moral identity are two factors commonly proposed to better understand the discrepancy between moral beliefs and moral action (Bergman, 2002; Darnell et al., 2019; Hoffman, 2000). This is supported by the current mainstream theoretical framework in the field, the four-component model (Han, 2014; Rest et al., 2000), which is also referred to as a model that explains the mechanisms of moral behavior to address the gappiness issue (Darnell et al., 2019). This theoretical framework suggests four psychological components important for moral behavior: moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character. Moral sensitivity is about decerning whether the current situation is potentially morally problematic and may cause any potential harm to others’ welfare (Bebeau, 2002); it is required to initiate the further moral psychological processes to generate moral behavior (Han, 2017). Moral judgment is related to making a decision to address a morally dilemmatic situation based on moral reasoning (Rest et al., 1999). Moral motivation is related to whether moral values are prioritized over other self-oriented values, so that one can implement the result of moral judgment by behaving morally (Blasi, 2013). Finally, moral character, such as courage, is required to initiate and sustain moral behavior even under difficulties and threats (Nunner-Winkler, 2007). According to the Neo-Kohlbergians, implementation of moral behavior can be explained by these multiple components, not by one component (Bebeau, 2002). Similar to what has been proposed in recent discussions on the gappiness issue, moral judgment does not necessarily result in moral behavior but should be supported by other functional components from this perspective.

Empathy and moral identity, which are two main constructs of interest in the present study, have close relationships with the aforementioned functional components filling the gap between moral judgment and moral behavior. Empathy is especially important for the moral sensitivity component because it involves imagining how others will feel and be affected by certain actions (Morton et al., 2006; Sadler, 2004). In addition, moral identity has been suggested to be a source of moral motivation because it emphasizes how important one’s moral values are to their sense of self in the context of their overall values (Aquino & Reed, 2002). Furthermore, if moral values are central to who an individual is, motivation to act morally will be enhanced (Hardy & Carlo, 2005).

Finally, moral foundations can be considered as the factors that constitute the basis of moral values, moral beliefs, and how to behave morally. Thus, it would be necessary to examine how moral foundations are associated with the aforementioned factors in moral functioning, empathic traits and moral identity, to better understand the mechanism of moral behavior. In fact, Walker (2002) notes that moral functioning is significantly influenced by how important an individual considers their moral values to their identity. Thus, moral foundations, which are closely associated with different sets of moral values, perhaps contribute to one’s moral identity.

Given this, we expect that moral foundations might play a fundamental role in moderating the functioning of moral identity and empathic traits, which have been suggested to modulate moral behavior. Although many previous studies have demonstrated that moral foundations significantly influence moral judgment (e.g., Graham et al., 2009; Koleva et al., 2012), which constitutes the basis of moral functioning, as mentioned earlier, only a few have addressed the relationship between moral foundations and the aforementioned two constructs, moral identity and empathy. Although a few previous studies have shown various relationships between moral foundations and moral identity (e.g., Smith et al., 2014) as well as between moral foundations and empathic traits (e.g., Graham et al., 2009; Graham et al., 2011) there has been little work done on the relationship between all three, specifically that of how different moral foundations predict moral identity and empathy. Because of this, the present study examined how moral foundations contributed to empathic traits and moral identity in order to better understand the mechanisms of moral behavior.

The Present Study

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, we used data-driven methods such as Bayesian statistics and model selection in order to properly investigate the relationships of interest. Specifically, we wanted to know how moral foundations uniquely contribute to empathic traits and moral identity. To answer the question, we collected data about moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity from participants and examined the relationship between those factors with a data-driven analysis method based on Bayesian inference. Because we were mainly interested in the relationship between moral foundations and other moral indicators, differences between the moral foundations themselves, such as among different political affiliations, were out of the scope of the current study.

Method

Participants and Procedure

We recruited 401 participants who completed the questionnaires online via Mechanical Turk (mTurk), however after detecting for responses by bots and problematic human response sets, the final analysis included 329 participants (171 females; Age M = 35.47, SD = 9.72; 268 Caucasians, 26 African Americans, 1 American Indian or Alaska Native, 10 Asian Americans, 8 Hispanic or Latinx, 15 other ethnicities). For the screening procedures, we employed Dennis et al.’s (2020) bot detection method and Dupuis et al.’s (2019) method for detecting the problematic human response sets. The Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Moral Foundations Questionnaire, and Moral Identity Scale were presented, followed by demographic questions.

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study at the beginning of the online survey session. Only the participants who agreed to participate in the present study after reviewing the consent form were presented with the questionnaires. As compensation, participants received $7.25 after completing the study. The study design and informed consent form were reviewed by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Alabama (IRB protocol number: 17–12-787).

Measures

Interpersonal Reactivity Index

This measure was developed by Davis (1983) in order to provide a measure that takes into account the multidimensional nature of empathy. We used each of the four subscales: empathic concern (EC) for emotional reactivity, perspective taking (PT) for ability to anticipate others’ thoughts, personal distress (PD) for discomfort resulting from emotions of others, and fantasy subscale (FS) for level of emotional investment in works of fiction such as books and movies. The index consisted of a total of 28 items. Each item was designated to measure one of the four subscales. Participants were provided with a list of different thoughts and feelings and asked to rate how well the statements describe them using a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (doesn’t describe me at all) to 4 (describes me very well). Sample items from each subscale include: “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me (EC),” “I try to look at everybody’s side of a disagreement before I make a decision (PT),” “I sometimes feel helpless when I am in the middle of a very emotional situation (PD),” “I daydream and fantasize, with some regularity, about things that might happen to me (FS).” The overall reliability of the index, which was estimated in terms of Cronbach’s α was good, α = .88. The calculated Cronbach’s α values of all subscales were also good, EC’s α = .89, PT’s α = .85, PD’s α = .89, and FS’s α = 84.

Moral Foundations Questionnaire

Moral Foundations were measured using this questionnaire developed by Graham et al. (2011). The measure begins by asking participants to rate the extent to which certain considerations affect how they decide what is right or wrong using a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all relevant) to 5 (extremely relevant). Sample items for each foundation subscale include: “Whether or not someone cared for someone weak or vulnerable (harm/care),” “Whether or not some people were treated differently than others (fairness/reciprocity),” “Whether or not someone’s action showed love for his or her country (ingroup/loyalty),” “Whether or not someone showed a lack of respect for authority (authority/respect),” and “Whether or not someone violated standards of purity and decency (purity/sanctity).” There is then a second part of the measure which asks participants to rate their level of agreement using a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) with statements similar in nature to the first part. We examine the reliability of this questionnaire with Cronbach’s α. The overall α indicated good reliability, α = .89. All foundation subscales also showed acceptable to good reliability, harm/care’s α = .76, fairness/reciprocity’s α = .76, ingroup/loyalty’s α = .74, authority/respect’s α = .80, and purity/sanctity’s α = 86.

Moral Identity Scale

Moral Identity was measured using this scale developed by Aquino and Reed (2002) in order to assess how important different moral traits are to somebody’s self-concept. Participants were given a list of nine traits (e.g., caring, fair, honest) related to being a moral person and asked to imagine somebody with these characteristics and how they would think, feel, and act. They then used a 5-point Likert scale to rate their level of agreement or disagreement with 13 statements from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Of the 13 statements, five (e.g., “It would make me feel good to be a person who has these characteristics”) are assigned to the internalization subscale and six (e.g., “I often buy products that communicate the fact that I have these characteristics”) to the symbolization subscale. Two statements are not used to measure moral identity. The overall Cronbach α was good, α = 81. Cronbach’s α values of both subscales were acceptable to excellent, the internalization subscale’s α = .78, and the symbolization subscale’s α = .92.

Demographics Survey

We surveyed participants’ demographic information and used them as control variables in the analyses. The survey questions included questions for participants’ age, gender, socioeconomic status (SES), occupation, and political affiliation. The SES was measured in terms of participants’ highest earned degree and annual income. The SES was quantified in terms of the composite score of the aforementioned two factors. Participants’ occupation and political affiliation were measured as categorical variables. The participants were asked to select their occupation and political affiliation among presented options (e.g., “management, professional, and related,” “service,” “sales and office,” etc. for occupation; “republican,” “democratic,” “libertarian,” etc. for political affiliation).

Analysis

In order to examine the relationships between the variables of interest, we conducted classical correlation analysis along with Bayesian correlation analysis, Bayesian ANCOVA, and Bayesian regression analysis. Bayesian methods have been used to examine which prediction model best predicted the intended dependent variable with the greatest model parsimony in previous studies in moral psychology (e.g., Han, 2021; Han & Dawson, 2021). Following the previous studies, in the present study, Bayesian ANCOVA was conducted to examine which independent variables best predicted dependent variables of interest, empathy and moral foundation variables. We set five moral foundations as independent variables and empathy- and moral identity-related variables as dependent variables. In the ANCOVA models, participants’ demographic information (i.e., age, gender, SES, occupation, political affiliation) was entered into the models as control variables. Regression analysis was performed to examine the direction of association (positive versus negative) between independent variables, which were identified in Bayesian ANCOVA, and dependent variables, and to estimate regression coefficients.

We examined whether evidence positively and/or strongly supported our hypotheses (e.g., presence of non-zero correlation) with resultant Bayes Factors. Calculated Bayes Factors were interpreted based on statistical guidelines that were introduced by Bayesian statisticians (Kass & Raftery, 1995) and have been used in previous studies (e.g., Han et al., 2018). In the present study, we used a logarithm of Bayes Factor (log(BF)). We assumed that 1 ≤ log(BF) < 3 indicates the presence of evidence positively supporting our hypothesis, 3 ≤ log(BF) < 5 indicates the presence of evidence strongly supporting our hypothesis, and 5 ≤ log(BF) indicates the presence of evidence very strongly supporting our hypothesis.

For readers’ information, all data files and JASP scripts are available via the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/kgznt/.

Results

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics of the collected dataset (N = 329 after screening) are presented in Table 1. The reported descriptive statistics include the mean, standard deviation, median, skewness, and kurtosis of each subscale in each measure (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of interpersonal reactivity index, moral foundations questionnaire, and moral identity scale variables

| M | SD | Median | Skewness | Kurtosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interpersonal Reactivity Index | Empathic concern (EC) | 3.78 | .90 | 3.86 | −.61 | −.16 |

| Perspective taking (PT) | 3.72 | .80 | 3.71 | −.48 | .09 | |

| Personal distress (PD) | 2.56 | .96 | 2.57 | .24 | −.56 | |

| Fantasy subscale (FS) | 3.45 | .89 | 3.43 | −.34 | −.35 | |

| Moral Foundations Questionnaire | Harm/Care | 4.62 | .86 | 4.67 | −.59 | .45 |

| Fairness/Reciprocity | 4.62 | .83 | 4.67 | −.52 | −.05 | |

| Ingroup/Loyalty | 3.31 | 1.03 | 3.17 | .19 | −.30 | |

| Authority/Respect | 3.51 | 1.08 | 3.50 | −.02 | −.57 | |

| Purity/Sanctity | 3.17 | 1.38 | 3.33 | .05 | −1.07 | |

| Moral Identity Scale | Internalization | 4.28 | .76 | 4.38 | −.94 | −.12 |

| Symbolization | 2.76 | 1.08 | 2.75 | .02 | −.78 |

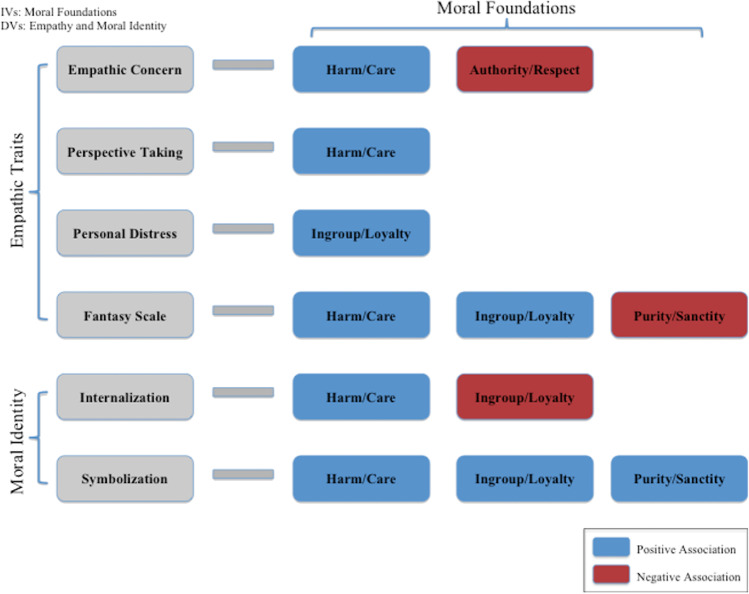

Fig. 1.

Results from both classical and Bayesian correlation analyses. All colored circles indicate a significant correlation at p < .05. Circle size and color corresponds to correlation coefficients, which are shown in the legend on the right. *: 1 ≤ logBF <3, **: 3 ≤ logBF <5. ***: 5 ≤ logBF. mfq_hc: harm/care. mfq_fr: fairness/reciprocity. mfq_igl: ingroup/loyalty. mfq_ar: authority/respect. mfq_ps: purity/sanctity. iri_ec: empathic concern. iri_pd: personal distress. iri_pt: perspective taking. iri_fs: fantasy scale. mis_int: internalization. mis_sym: symbolization

Correlation Analysis

For empathic traits, Bayesian correlation analysis showed EC positively correlated with harm/care, log(BF10) = 65.318, fairness/reciprocity, log(BF10) = 18.542, internalization, log(BF10) = 65.047, and symbolization, log(BF10) = 5.588. According to the guidelines for interpreting log(BF), all of these results suggest the presence of evidence very strongly supporting non-zero correlation between the aforementioned variables. PT positively correlated with harm/care, log(BF10) = 35.499, fairness/reciprocity, log(BF10) = 10.258, and internalization, log(BF10) = 27.833. PD positively correlated with ingroup/loyalty, log(BF10) = 2.903 and negatively correlated with internalization, log(BF10) = 5.395. FS positively correlated with harm/care, log(BF10) = 16.687, fairness/reciprocity, log(BF10) = 7.270, internalization, log(BF10) = 13.019, and symbolization, log(BF10) = 4.788.

For moral identity, internalization was positively correlated with harm/care, log(BF10) = 29.197 and fairness/reciprocity, log(BF10) = 14.682 but did not have a significant correlation with the other foundations. Symbolization, however, had a positive correlation with ingroup/loyalty, log(BF10) = 21.605, authority/respect, log(BF10) = 16.213 and purity/sanctity, log(BF10) = 14.882 but did not have a significant correlation with the other foundations.

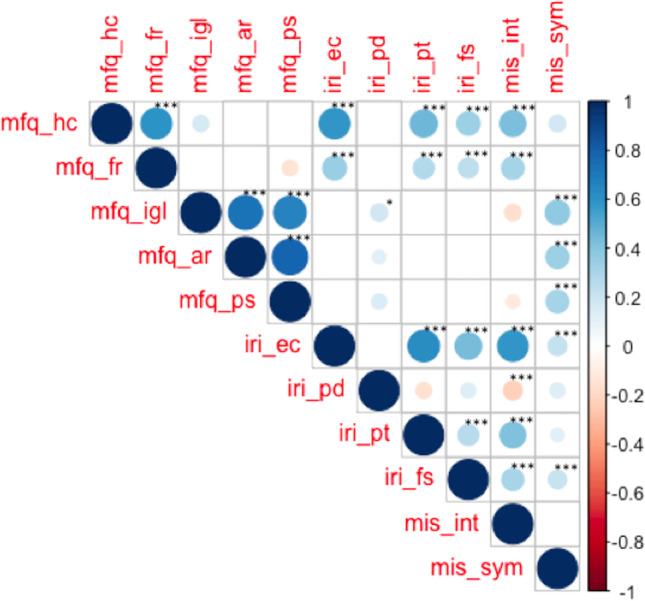

Bayesian Model Selection and Regression Analysis

Model selection using Bayesian ANCOVA and the estimation of selected regression coefficients with Bayesian regression showed the best model for EC included harm/care (+, positive association) and authority/respect (−, negative association), for PT harm/care (+), for PD ingroup/loyalty(+), for FS harm/care(+), ingroup/loyalty(+), and purity/sanctity(−), for internalization harm/care(+) and ingroup/loyalty(−), and for symbolization purity/sanctity(+), harm/care(+), and ingroup/loyalty(+) (see Fig. 2 for the visualization). For further details about the results from Bayesian model selection and regression (e.g., estimated regression coefficients), see supplementary tables.

Fig. 2.

Results from Bayesian ANCOVA and regression analysis

Discussion

The main goal of this study was to explore the associations between moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity through data-driven examination. The results from classical and Bayesian correlation analyses demonstrated that each empathic trait and moral identity subscale was differently correlated with the various individualizing and binding foundations proposed in MFT. The results of our Bayesian ANCOVA and regression analysis showed interesting aspects regarding how moral foundations differently contributed to various moral functionalities, empathic traits, and moral identity. Our Bayesian ANCOVA results showed that EC, PT, and moral internalization, which have been found to be significantly associated with moral decision-making and motivation in general, were well explained by harm/care. This is in line with Gray and Schein’s (2012) argument that the functioning of the five moral foundations in moral judgment can be explained by the harm/care foundation alone. However, PT was the only variable that had a significant association with only harm/care. All of the other variables had significant associations with other moral foundations as well.

Interestingly, several binding foundations negatively contributed to the aforementioned variables. EC was negatively associated with authority/respect and internalization with ingroup/loyalty. In addition, PD was positively associated with ingroup/loyalty. These trends are consistent with previous studies that demonstrated the complex relationship between loyalty and ethical behavior (e.g., Hildreth et al., 2016). If, as the authors suggested, loyalty makes people more likely to act ethically when pressure is low but less likely to act ethically when pressure is high, this may result in PD when faced with a moral dilemma or upon feeling conflicted when considering how one’s actions will affect the people involved while also considering acting in accord with the ingroup. Additionally, since PD was originally thought to hinder the ability to maintain social relationships (Davis, 1983), it is possible that once individuals with high PD find an ingroup, they are more motivated to be loyal to this group.

Moral symbolization was positively predicted by both individualizing and binding foundations: harm/care, ingroup/loyalty, and purity/sanctity. The positive correlation between moral symbolization and harm/care is in line with previous research that has shown concern for how others will be harmed when deciding the best course of action to take (Cohn et al., 2019). Conversely, given that moral symbolization is more related to the conduct of moral values within social and relational contexts (Aquino & Reed, 2002; Sunil & Verma, 2018), it makes sense that moral symbolization would be influenced by binding foundations, which are associated with how to maintain community and communal good (Smith et al., 2014). Moral symbolization as opposed to moral internalization being positively predicted by binding foundations may suggest a possible way to buffer against the potential negative effects of endorsing binding foundations. Since individuals who prefer binding foundations are more likely to be concerned with their in-group and its values, it may be more effective to approach moral issues with them in a manner that emphasizes moral symbolization. One previous study suggests that encouraging these individuals to focus on the possibility of losing their perception of a moral figure to the public may be effective in promoting moral behavior (Szekeres et al., 2019).

Finally, although the FS subscale of the Interpersonal Reactivity Index is controversial due to confusion over how to interpret the subscale and possible similarities between empathizing with real people and empathizing with fictional characters (Nomura & Akai, 2012), it is worth noting that for the model selection, FS was predicted by three of the five moral foundations; harm/care and ingroup/loyalty were both positively correlated while purity/sanctity was negatively correlated. Additionally, FS was positively correlated with both internalization and symbolization.

These findings from our study may provide moral educators with several useful insights for moral education. Since empathy and moral identity have been suggested as sources of motivation to participate in moral acts by promoting a sense of purpose (Hardy et al., 2014; Malin et al., 2015), it may be helpful to understand which moral foundations support a strong sense of moral identity. More specifically, our study showed that the harm/care foundation is positively associated with both internalization and symbolization. This result suggests this is an important place to start when educating children. Thus, moral educators may need to consider how to help young children acquire skills to effectively deal with potential harm to others and caring for others’ welfare.

In fact, such an aspect of moral functioning has been underscored by Neo-Kohlbergians; in their theoretical model of moral functioning, the four component model, moral sensitivity plays a fundamental role in detecting potential harm to others as well as factors that may influence their welfare (Bebeau et al., 1985). Without such moral sensitivity, it is difficult to interpret the current situation, perceive potential moral outcomes in terms of potential harm and changes in others’ welfare, and behave morally to deal with the situation. Moral education focusing on harm and care in early childhood will contribute to the development of the aforementioned functionalities including, but not limited to, empathic traits, moral sensitivity, and moral identity, as well as future moral development.

In line with this, Thornberg and Jungert (2013) found that moral sensitivity in students was negatively associated with bullying behavior, however, they note that moral disengagement and self-efficacy are also crucial factors that mediate this relationship. That is, it is important to have moral sensitivity, but if a student does not believe they can do something to stop the bullying, or if they are able to remove themselves from the reality of the situation, moral sensitivity may not result in actual behavior (see Bandura, 2002 for further details about mechanisms of moral disengagement). This is interesting considering the previously discussed idea that empathy is important for moral sensitivity and the finding from the current study that authority/respect was negatively associated with EC. One previous study used interviews to explore why soccer players committed immoral acts on the field and found that many of them placed responsibility for their actions onto referees, whom they viewed as an authority figure (Traclet et al., 2011). This suggests that it is important to not only teach students the importance of moral values associated with the harm/care foundation but also to avoid using mechanisms that promote moral disengagement. This point can be related to Neo-Kohlbergian theory that underscores moral education for the development of moral judgment to achieve the sophistication of postconventional moral thinking that enables students to critically evaluate the moral justifiability of existing authority and convention based on moral principles (Rest et al., 1999).

Given this, methods for moral education that target young children may need to start with how to develop their sensitivity to harm and welfare. For instance, Han et al. (2017) suggest that using attainable and relevant moral exemplars with strong empathy and moral identity may be an effective way to show children examples of people being moral in a way that feels realistic for them to emulate. Along with Bandura and McDonald’s (1963) suggestion that the presentation of moral exemplars can be an effective measure to promote moral development among young children, moral educators may utilize attainable and relevant exemplars in the domain of harm and care in moral education for young children. Finally, as Malin et al. (2015) suggest, concern for moral issues is necessary for youth to possess civic purpose and eventual positive youth development, but it needs to be supported by learning about and freely exploring moral values. In fact, Han et al. (2021) showed that the presence of moral identity significantly contributed to the formation and maintenance of political purpose during emerging adulthood. Taken together with the present study, this would suggest that young children need the opportunity to learn about core values related to morality, particularly harm/care that significantly contributes to empathy and moral identity, in addition to participating in activities that allow them to understand the values on a deeper level.

Furthermore, the aforementioned points related to moral education and development can be applicable to older populations, adults. Although we collected data from college students, who are old adolescents or young adults, findings from studies on adulthood moral development suggest that moral development can occur beyond adolescence (Colby & Damon, 1992). For instance, old adults can identify their prosocial purpose as well as empathy even after retiring from their primary career (Bundick et al., 2021). Hence, it would be possible to consider developing and implementing programs and activities focusing on the core value of harm/care as a way to promote the development of empathic traits and moral identity among adults.

Additionally, due to the negative association between ingroup/loyalty and moral internalization, morals based on identifying with a certain group may not lead to a sense of empathy and moral identity and ultimately moral behavior. We may discuss the implication of this result based on Neo-Kohlbergian theory of moral judgment development. The result from our study is connected with evidence that the ingroup/loyalty foundation is associated with the personal interests schema and maintaining norm schema, while the postconventional schema that indicates more sophisticated moral judgment is associated with a stronger preference for the harm/care foundation (Baril & Wright, 2012). Hence, moral educators may need to help students critically reflect upon existing social norms and conventions, which are concerned about ingroup membership and loyalty to authority, and take into account fundamental moral principles, which address potential harm to others and their welfare. Doing so would be a possible way to promote students’ empathy and moral identity given that the harm/care foundation was the fundamental predictor of empathic traits and moral identity as demonstrated in our study.

Limitations

This study was exploratory in nature, which is a primary limitation. Future research is needed in order to replicate the findings as well as investigate the operative power of theories of moral identity (Hardy, 2017). It would be interesting to investigate whether the relationships examined between moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity would affect actual behavior in the real world. Specifically for our measure of moral identity, the moral identity scale, it has been found to have strong explanatory power but weak predictive power. Due to this, a different measure of moral identity may be necessary when studying actual behavior. Moreover, further longitudinal research would be necessary to examine the potential causal relationships among moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity that could not be examined in the present study that analyzed cross-sectional data.

Conclusion

We found that in general, harm/care commonly predicted empathic traits and moral internalization, which are closely associated with moral decision-making and motivation at the personal level. Interestingly, binding foundations also significantly predicted moral symbolization, which deals with moral identity within social and relational contexts. These findings may suggest the differentiated associations between moral foundations, empathic traits, and moral identity within different domains.

Supplementary Information

(PDF 100 kb)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Joshua May and Clifford I. Workman for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of this manuscript. This work was supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation (Grant number: 48365) and the University of Alabama Research Grant Committee (RG14785).

Authors’ Contributions

Conceptualization: Hyemin Han and Kelsie J. Dawson; Methodology: Hyemin Han, Kelsie J. Dawson, and YeEun Rachel Choi; Formal analysis and investigation: Hyemin Han and Kelsie J. Dawson; Writing – original draft preparation: Hyemin Han, Kelsie J. Dawson, and YeEun Rachel Choi; Writing – review and editing: Hyemin Han, Kelsie J. Dawson, and YeEun Rachel Choi; Funding acquisition: Hyemin Han; Supervision: Hyemin Han.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the John Templeton Foundation (Grant number: 48365) and the University of Alabama Research Grant Committee (RG14785).

Data Availability

For readers’ information, all data files and JASP scripts are available via the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/kgznt/.

Code Availability

For readers’ information, all data files and JASP scripts are available via the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/kgznt/.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Alabama Institutional Review Board (17–12-787) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study at the beginning of the online survey session. No identifying information is included in this article.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kelsie J. Dawson and Hyemin Han contributed equally to this work and are listed alphabetically.

References

- Aquino K, Reed II. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(6):1423–1440. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.6.1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aquino K, Freeman D, Reed II, Lim VK, Felps W. Testing a social-cognitive model of moral behavior: The interactive influence of situations and moral identity centrality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;97(1):123–141. doi: 10.1037/a0015406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldner C, Pierro A, Chernikova M, Kruglanski AW. When and why do liberals and conservatives think alike? An investigation into need for cognitive closure, the binding moral foundations, and political perception. Social Psychology. 2018;49(6):360–368. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education. 2002;31(2):101–119. doi: 10.1080/0305724022014322. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, McDonald FJ. Influence of social reinforcement and the behavior of models in shaping children's moral judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 1963;67(3):274–281. doi: 10.1037/h0044714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baril GL, Wright JC. Different types of moral cognition: Moral stages versus moral foundations. Personality and Individual Differences. 2012;53(4):468–473. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.04.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeau MJ. The defining issues test and the four component model: Contributions to professional education. Journal of Moral Education. 2002;31:271–295. doi: 10.1080/0305724022000008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebeau MJ, Rest JR, Yamoor CM. Measuring dental students’ ethical sensitivity. Journal of Dental Education. 1985;49(4):225–235. doi: 10.1002/j.0022-0337.1985.49.4.tb01874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman R. Why be moral? A conceptual model from developmental psychology. Human Development. 2002;45(2):104–124. doi: 10.1159/000048157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, F., Kosic, A., & Pierro, A. (2021). COVID-19 and prejudice against migrants: the mediating roles of need for cognitive closure and binding moral foundations. A comparative study. The Journal of Social Psychology, 1–15. 10.1080/00224545.2021.1900046 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Black JE. An introduction to the moral agency scale. Social Psychology. 2016;47(6):295–310. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000284. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Black JE, Reynolds WM. Development, reliability, and validity of the moral identity questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016;97:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi A. Moral cognition and moral action: A theoretical perspective. Developmental Review. 1983;3(2):178–210. doi: 10.1016/0273-2297(83)90029-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blasi A. Handbook of moral motivation. SensePublishers; 2013. The self and the management of the moral life; pp. 229–248. [Google Scholar]

- Bundick MJ, Remington K, Morton E, Colby A. The contours of purpose beyond the self in midlife and later life. Applied Developmental Science. 2021;25(1):62–82. doi: 10.1080/10888691.2018.1531718. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlo G, Allen JB, Buhman DC. Facilitating and disinhibiting prosocial behaviors: The nonlinear interaction of trait perspective taking and trait personal distress on volunteering. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1999;21(3):189–197. doi: 10.1207/S15324834BASP2103_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Choi Y-J, Han H, Bankhead M, Thoma SJ. Validity study using factor analyses on the defining issues Test-2 in undergraduate populations. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0238110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn A, Maréchal MA, Tannenbaum D, Zünd CL. Civic honesty around the globe. Science. 2019;365(6448):70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.aau8712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby A, Damon W. Some do care: Contemporary lives of moral commitment. Free Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis J, Billingslea R, Wilson JP. Personality correlates of moral reasoning and attitudes toward authority. Psychological Reports. 1988;63:947–954. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1988.63.3.947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W, Gregory A. The youth charter: Towards the formation of adolescent moral identity. Journal of Moral Education. 1997;26(2):117–130. doi: 10.1080/0305724970260201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darnell C, Gulliford L, Kristjánsson K, Paris P. Phronesis and the knowledge-action gap in moral psychology and moral education: A new synthesis? Human Development. 2019;62(3):101–129. doi: 10.1159/000496136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1983;44(1):113–126. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decety J, Cowell JM. The complex relation between morality and empathy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2014;18(7):337–339. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis SA, Goodson BM, Pearson C. Online worker fraud and evolving threats to the integrity of MTurk data: A discussion of virtual private servers and the limitations of IP-based screening procedures. Behavioral Research in Accounting. 2020;32(1):119–134. doi: 10.2308/bria-18-044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis M, Meier E, Cuneo F. Detecting computer-generated random responding in questionnaire-based data: A comparison of seven indices. Behavior Research Methods. 2019;51(5):2228–2237. doi: 10.3758/s13428-018-1103-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Jung WH, Korczykowski M, Luo L, Prehn K, Xu S, Detre JA, Kable JW, Robertson DC, Rao H. Post-conventional moral reasoning is associated with increased ventral striatal activity at rest and during task. Scientific Reports. 2017;7(1):7105. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07115-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg M, Willer R. The moral roots of environmental attitudes. Psychological Science. 2013;24(1):56–62. doi: 10.1177/0956797612449177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galang CM, Johnson D, Obhi SS. Exploring the relationship between empathy, self-construal style, and self-reported social distancing tendencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology. 2021;12:588934. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.588934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleichgerrcht E, Young L. Low levels of empathic concern predict utilitarian moral judgment. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e60418. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0060418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover RJ, Natesan P, Wang J, Rohr D, McAfee-Etheridge L, Booker DD, Bishop J, Lee D, Kildare C, Wu M. Moral rationality and intuition: An exploration of relationships between the defining issues test and the moral foundations questionnaire. Journal of Moral Education. 2014;43(4):395–412. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2014.953043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Haidt J, Nosek BA. Liberals and conservatives rely on different sets of moral foundations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(5):1029–1046. doi: 10.1037/a0015141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Nosek BA, Haidt J, Iyer R, Koleva S, Ditto PH. Mapping the moral domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101(2):366–385. doi: 10.1037/a0021847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J, Haidt J, Koleva S, Motyl M, Iyer R, Wojcik SP, Ditto PH. Moral foundations theory: The pragmatic validity of moral pluralism. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2013;47:55–130. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00002-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Graham A, Cullen FT, Pickett JT, Jonson CL, Haner M, Sloan MM. Faith in trump, moral foundations, and social distancing defiance during the coronavirus pandemic. Socius. 2020;6:2378023120956815. doi: 10.1177/2378023120956815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gray K, Schein C. Two minds vs. two philosophies: Mind perception defines morality and dissolves the debate between deontology and utilitarianism. Review of Philosophy and Psychology. 2012;3(3):405–423. doi: 10.1007/s13164-012-0112-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Graham J. When morality opposes justice: Conservatives have moral intuitions that liberals may not recognize. Social Justice Research. 2007;20(1):98–116. doi: 10.1007/s11211-007-0034-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haidt J, Joseph C. Intuitive ethics: How innately prepared intuitions generate culturally variable virtues. Daedalus. 2004;133(4):55–66. doi: 10.1162/0011526042365555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. Analyzing theoretical frameworks of moral education through Lakatos’s philosophy of science. Journal of Moral Education. 2014;43(1):32–53. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2014.893422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. Neural correlates of moral sensitivity and moral judgment associated with brain circuitries of selfhood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Moral Education. 2017;46(2):97–113. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2016.1262834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han H. Exploring the association between compliance with measures to prevent the spread of COVID-19 and big five traits with Bayesian generalized linear model. Personality and Individual Differences. 2021;176:110787. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.110787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., & Dawson, K. J. (2021). Improved model exploration for the relationship between moral foundations and moral judgment development using Bayesian model averaging. Journal of Moral Education.10.1080/03057240.2020.1863774

- Han H, Kim J, Jeong C, Cohen GL. Attainable and relevant moral exemplars are more effective than extraordinary exemplars in promoting voluntary service engagement. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:283. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Park J, Thoma SJ. Why do we need to employ Bayesian statistics and how can we employ it in studies of moral education?: With practical guidelines to use JASP for educators and researchers. Journal of Moral Education. 2018;47(4):519–537. doi: 10.1080/03057240.2018.1463204. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Han H, Dawson KJ, Choi YR, Choi Y-J, Glenn AL. Development and validation of the English version of the moral growth mindset measure [version 3; peer review: 4 approved] F1000Research. 2020;9:256. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.23160.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han, H., Ballard, P. J., & Choi, Y. J. (2021). Links between moral identity and political purpose during emerging adulthood. Journal of Moral Education. 10.1080/03057240.2019.1647152

- Hardy SA. Moral identity theory and research: A status update. In: Helwig CC, editor. New perspectives on moral development. Routledge; 2017. pp. 99–114. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SA, Carlo G. Identity as a source of moral motivation. Human Development. 2005;48(4):232–256. doi: 10.1159/000086859. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy SA, Walker LJ, Olsen JA, Woodbury RD, Hickman JR. Moral identity as moral ideal self: Links to adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(1):45–57. doi: 10.1037/a0033598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildreth JAD, Gino F, Bazerman M. Blind loyalty? When group loyalty makes us see evil or engage in it. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes. 2016;132:16–36. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2015.10.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman ML. Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings PL, Mitchell MS, Hannah ST. The moral self: A review and integration of the literature. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2015;36(S1):S104–S168. doi: 10.1002/job.1919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kass RE, Raftery AE. Bayes factors. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1995;90(430):773–795. doi: 10.2307/2291091. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koleva SP, Graham J, Iyer R, Ditto PH, Haidt J. Tracing the threads: How five moral concerns (especially purity) help explain culture war attitudes. Journal of Research in Personality. 2012;46(2):184–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jrp.2012.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lan G, Gowing M, McMahon S, Rieger F, King N. A study of the relationship between personal values and moral reasoning of undergraduate business students. Journal of Business Ethics. 2008;78(1–2):121–139. doi: 10.1007/s10551-006-9322-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malin H, Ballard PJ, Damon W. Civic purpose: An integrated construct for understanding civic development in adolescence. Human Development. 2015;58(2):103–130. doi: 10.1159/000381655. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez AG, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. Can perspective-taking reduce crime? Examining a pathway through empathic-concern and guilt-proneness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2014;40(12):1659–1667. doi: 10.1177/0146167214554915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton KR, Worthley JS, Testerman JK, Mahoney ML. Defining features of moral sensitivity and moral motivation: Pathways to moral reasoning in medical students. Journal of Moral Education. 2006;35(3):387–406. doi: 10.1080/03057240600874653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Myyrya L, Juujärvi S, Pesso K. Empathy, perspective taking and personal values as predictors of moral schemas. Journal of Moral Education. 2010;39(2):213–233. doi: 10.1080/03057241003754955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nomura K, Akai S. Empathy with fictional stories: reconsideration of the fantasy scale of the interpersonal reactivity index. Psychological Reports. 2012;110(1):304–314. doi: 10.2466/02.07.09.11.pr0.110.1.304-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunner-Winkler G. Development of moral motivation from childhood to early adulthood1. Journal of Moral Education. 2007;36(4):399–414. doi: 10.1080/03057240701687970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paciello M, Fida R, Cerniglia L, Tramontano C, Cole E. High cost helping scenario: The role of empathy, prosocial reasoning and moral disengagement on helping behavior. Personality and Individual Differences. 2013;55(1):3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rest J, Narvaez D, Bebeau M, Thoma S. A neo-Kohlbergian approach: The DIT and schema theory. Educational Psychology Review. 1999;11(4):291–324. doi: 10.1023/A:1022053215271. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rest JR, Narvaez D, Thoma SJ, Bebeau MJ. A neo-Kohlbergian approach to morality research. Journal of Moral Education. 2000;29(4):381–395. doi: 10.1080/713679390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, S. J., & Ceranic, T. L. (2007). The effects of moral judgment and moral identity on moral behavior: an empirical examination of the moral individual. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(6), 1610–1624. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1610 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sadler TD. Moral sensitivity and its contribution to the resolution of socio-scientific issues. Journal of Moral Education. 2004;33(3):339–358. doi: 10.1080/0305724042000733091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver JR, Silver E. Why are conservatives more punitive than liberals? A moral foundations approach. Law and Human Behavior. 2017;41(3):258. doi: 10.1037/lhb0000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith IH, Aquino K, Koleva S, Graham J. The moral ties that bind... even to out-groups: The interactive effect of moral identity and the binding moral foundations. Psychological Science. 2014;25(8):1554–1562. doi: 10.1177/0956797614534450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strobel A, Grass J, Pohling R, Strobel A. Need for cognition as a moral capacity. Personality and Individual Differences. 2017;117:42–51. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunil S, Verma SK. Moral identity and its links to ethical ideology and civic engagement. Journal of Human Values. 2018;24(2):73–82. doi: 10.1177/0971685818754547. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szekeres H, Halperin E, Kende A, Saguy T. The effect of moral loss and gain mindset on confronting racism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2019;84:103833. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2019.103833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J. Association of Personal Distress with Burnout, compassion fatigue, and compassion satisfaction among clinical social workers. Journal of Social Service Research. 2013;39(3):365–379. doi: 10.1080/01488376.2013.771596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg R, Jungert T. Bystander behavior in bullying situations: Basic moral sensitivity, moral disengagement and defender self-efficacy. Journal of Adolescence. 2013;36(3):475–483. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traclet A, Romand P, Moret O, Kavussanu M. Antisocial behavior in soccer: A qualitative study of moral disengagement. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology. 2011;9(2):143–155. doi: 10.1080/1612197x.2011.567105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LJ. The model and the measure: An appraisal of the Minnesota approach to moral development. Journal of Moral Education. 2002;31(3):353–367. doi: 10.1080/0305724022000008160. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Winterich KP, Zhang Y, Mittal V. How political identity and charity positioning increase donations: Insights from moral foundations theory. International Journal of Research in Marketing. 2012;29(4):346–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2012.05.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 100 kb)

Data Availability Statement

For readers’ information, all data files and JASP scripts are available via the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/kgznt/.

For readers’ information, all data files and JASP scripts are available via the Open Science Framework, https://osf.io/kgznt/.