Abstract

Brain structural features of healthy individuals are associated with olfactory functions. However, due to the pathophysiological differences, congenital and acquired anosmia may exhibit different structural characteristics. A systematic review was undertaken to compare brain structural features between patients with congenital and acquired anosmia. A systematic search was conducted using PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus electronic databases to identify eligible reports on anosmia and structural changes and reported according to PRISMA guidelines. Reports were extracted for information on demographics, psychophysical evaluation, and structural changes. Then, the report was systematically reviewed based on various aetiologies of anosmia in relation to (1) olfactory bulb, (2) olfactory sulcus, (3) grey matter (GM), and white matter (WM) changes. Twenty-eight published studies were identified. All studies reported consistent findings with strong associations between olfactory bulb volume and olfactory function across etiologies. However, the association of olfactory function with olfactory sulcus depth was inconsistent. The present study observed morphological variations in GM and WM volume in congenital and acquired anosmia. In acquired anosmia, reduced olfactory function is associated with reduced volumes and thickness involving the gyrus rectus, medial orbitofrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, and cerebellum. These findings contrast to those observed in congenital anosmia, where a reduced olfactory function is associated with a larger volume and higher thickness in parts of the olfactory network, including the piriform cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, and insula. The present review proposes that the structural characteristics in congenital and acquired anosmia are altered differently. The mechanisms behind these changes are likely to be multifactorial and involve the interaction with the environment.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00429-021-02397-3.

Keywords: Congenital anosmia, Acquired anosmia, Idiopathic olfactory loss, Upper respiratory tract infection, Post-traumatic brain injury, VBM, MRI

Introduction

The etiologies of olfactory dysfunction include congenital causes, ageing, idiopathic changes, infections of the upper respiratory tract (URTI), sinonasal disease (SND), traumatic brain injury (TBI), and neurologic illnesses including Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease (Wiesmann et al. 2001; Barresi et al. 2012). Olfactory dysfunction can affect all areas of life—from preparation and enjoyment of foods to the appreciation of the fragrances of flowers, detection and avoidance of hazardous odours, maintenance of personal hygiene, and the social or intimate interactions with others (Stevenson 2009; Croy et al. 2014).

The sense of smell allows us to identify the chemical nature in the surroundings. Sensory neurons in the nose detect odour molecules and transmit signals to the olfactory bulb (OB), a structure in the forebrain where initial odour processing occurs (Han et al. 2019). The OB collects the sensory afferents of the olfactory receptor cells located in the olfactory neuroepithelium. The axonal projections are then conveyed with a relay in the OB to the piriform cortex through the olfactory tract (Gottfried 2010). The piriform cortex projects to multiple brain regions within the limbic system. This system is directly connected with the frontal cortex through pathways to the posterior orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) as well as indirectly via the mediodorsal thalamic nucleus (Carmichael et al. 1994; Illig 2005). The OB is closely related to the olfactory sulcus (OS), located in the frontal lobe (Rombaux et al. 2009b). Previous studies suggest the OB volume (Mazal et al. 2016; Shehata et al. 2018; Yousem et al. 1996b), and OS depth (Miao et al. 2015) change according to different types of olfactory disorders suggesting that peripheral olfactory input influences the OB volume, in which OB volume is smaller, and OS depth is shallow in anosmic patients. Little is known about cortical brain areas beyond the OB and OS. Only a few studies reported pattern and variability of grey matter (GM) and white matter (WM) in patients with olfactory loss (Bitter et al. 2010a, b; Peng et al. 2013; Yao et al. 2018; Yousem et al. 1996a).

Previous studies have examined how the human sense of smell is linked to morphological variations in the GM, especially in the piriform cortex and OFC. Delon-Martin et al. (2013) reported that healthy expert perfumers had increased volume in the bilateral posterior gyrus rectus extending into the medial orbital gyrus within the medial OFC (mOFC) compared to healthy controls. Additionally, age and years of professional experience were positively associated with increased volume in the bilateral piriform cortex (Delon-Martin et al. 2013). Studies of patients with hyposmia and anosmia due to various causes were reported to have decreased volumes of right but not left piriform cortex (Bitter et al. 2010a, b) and reduced volume in right mOFC in patients with anosmic (Bitter et al. 2010b). In contrast to acquired loss, individuals with congenital anosmia had increased volume of the left piriform cortex and increased thickness of anterior medial orbital gyrus bilaterally with no apparent volume changes (Frasnelli et al. 2013). Karstensen et al. (2018) also reported congenital anosmia and found reduced GM volume in the left mOFC and increased volume in the right piriform cortex and superior frontal sulcus (SFS) (Karstensen et al. 2018). Another study that also reported congenital anosmia demonstrated GM volume atrophy in bilateral olfactory sulci (Peter et al. 2020). Peter et al. (2020) further showed increased GM volume and cortical thickness in the medial orbital gyri, regions closely associated with olfactory processing, sensory integration, and value-coding (Peter et al. 2020). Taken together, findings to date indicate the morphological changes within the cortex and areas related to olfactory processing vary as a function of olfactory ability. However, it is unclear whether GM and WM expansion or shrinkage differences are connected to different types of olfactory impairment, i.e., acquired and congenital anosmia. This systematic review aims to evaluate the associations between quantitative measures of olfaction to brain structures among patients with acquired and congenital anosmia. A comprehensive understanding of the anatomy and pathophysiology found in the anosmic population is critical to improve our understanding of olfactory loss and olfactory function in healthy people.

Methods

Search strategy and study selection

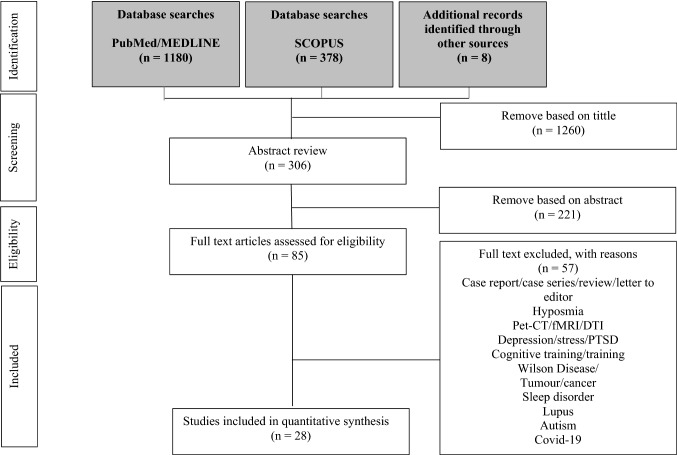

Two independent researchers (HAM and NY) conducted a systematic search using PubMed/MEDLINE and Scopus electronic databases. The systematic search method used in the present study was based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines (PRISMA) (Moher et al. 2009) and followed previous studies (Yahya and Manan 2019, 2020a, b; Yahya et al. 2018; Manan et al. 2020a, b, 2021; Yap et al. 2021). The search was performed to identify studies reporting congenital anosmia and acquired anosmia using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Article search was conducted between the earliest record and 26 July 2021. Search terms were as follow: ((((((((((anosmia)) OR (congenital anosmia)) OR (acquired anosmia)) OR (smell impairment)) OR (olfactory loss)) OR (olfactory dysfunction)) OR (olfactory deficit)) OR (smell blindness)) OR (smell dysfunction)) AND ((( (Magnetic resonance imaging)) OR (MRI)) OR (MR Imaging)). We also manually checked for related articles in references and citations through the Google Scholar database. There was no limitation on the publication date. All records were grouped into a final database after removing duplicates, followed by screening the titles and abstracts and finally full-text article screening and eligibility by HAM and NY, independently, the details of the selected studies are tabulated in Fig. 1. Consensus for eligibility was reached through discussion. We used an assessment tool from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, to assess the quality of included studies https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the search process for studies included in the present systematic review

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Original studies reported in peer-reviewed journals describing research on structural brain changes in anosmia using MRI were included. We included studies describing research on patients with anosmia (congenital and acquired) that include studies that used standardised measures of olfactory function, e.g., the measurement of odour threshold, discrimination and identification (TDI score) (Hummel et al. 2017), and assessing any olfactory component; OB volume, OS depth, WM, and GM. We excluded all review articles as well as case reports and case series studies. We also exclude functional MRI (fMRI), diffusor tensor imaging (DTI), electro-encephalography (EEG), and magneto-encephalography (MEG) studies. We also exclude olfactory dysfunction in relation to neurodegenerative diseases and neuropsychiatric disorders such as; Alzheimer's and syndromes such as Kallmann and Bardet Biedl syndromes. Finally, we exclude anosmia in patients with SARS-CoV-2 or COVID-19 infection because findings on COVID-19 are currently developing and unclear. We estimate that olfactory loss due to COVID-19 requires an independent review due to its emerging nature. Following the removal of duplicates and citations from non-English language journals, those evidently outside the review’s scope were rejected. From the eligible studies, the following variables were recorded: year of publication, country, study author(s), analysis mode, participants’ demographics, including age, handedness, duration of olfactory loss, psychophysical and physiological tests, and principal findings.

Results

Study demographics and details

Table 1 provides a summary of demographic information of anosmic patients with various etiologies, including congenital anosmia, idiopathic olfactory loss (IOL), infections of the upper respiratory tract (URTI), and traumatic brain injury (TBI). Across 28 studies, 2024 participants have investigated; 1639 patients and 385 healthy controls. Generally, studies have reasonable quality, as shown in Supplementary A. Sample size calculations were rarely mentioned, and the number of anosmic patients reported was between 3 and 378 patients per study. None of the studies was blinded due to the nature of the studies, which require the direct involvement of personnel-in-charge. Gender of participants were reported in some of the studies and indicated slightly more females (anosmia: males = 581, females = 625 and not mentioned = 433, healthy controls: male = 173, female = 196 and not mentioned = 16). The studies were conducted in multiple countries, including South Korea, The Netherlands, Germany, Belgium, PR China, the USA, and Taiwan. The age of the participants ranged from 9 to 73 years old. Seventeen studies compared anosmic patients to age-and sex-matched healthy controls. However, no study conducted separate analyses based on age and gender. Seven studies exclusively accrued right-handed participants (Bitter et al. 2010a, b; Peng et al. 2013; Yao et al. 2014, 2018; Miao et al. 2015; Frasnelli et al. 2013; Jiang et al. 2009a, b). Information provided on the duration of olfactory loss varied across studies (10 days to 600 months). However, for congenital anosmia, the time of diagnosis was typically not provided. Most studies performed nasal endoscopy to screen for obstructive or inflammatory causes of smell dysfunction.

Table 1.

Studies of anosmia with various etiologies: demographic information, clinical characteristics, and associated tests

| No. | MRI filed strength | Age, gender, and etiology | Duration of olfactory loss | Otorhinolaryngological evaluation | Psychophysical, physiological tests and questionnaire | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Various etiology | ||||||

|

(Chung et al. 2018) Korea |

3T CX Philips 64-channel |

34 Pt. (15M/19F) 9–72 years CRS = 15 PIOD = 7 Trauma = 2 Idiopathic ` = 10 |

Mean = 59.2 months 2–552 months |

Nasal endoscopic |

Sniffin’ Sticks (Korean version) Sino-Nasal Outcome Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorder (QOD) |

|

|

(Hummel et al. 2015) Germany |

1.5T Signa Echospeed, GEMS |

378 Pt. (185M/193F) Mean age: 49 ± 14 CRS = 99 PIOD = 78 Trauma = 201 |

Nasal endoscopic Otorhinolaryngological investigation |

Sniffin’ Sticks | ||

|

(Goektas et al. 2009) Germany |

1.5T Symphony Vision |

10 Pt. PIOD = 3 Trauma = 4 Idiopathic ` = 3 |

Mean = 146 ± 203 7–600 months |

Nasal endoscopic | Sniffin’ Sticks | *Only anosmia Pt. were included in this study |

|

(Fonteyn et al. 2014) Belgium |

267 Pt. PIOD = 76 Trauma = 103 Idiopathic ` = 40 Congenital = 27 Toxic = 10 Neurological = 11 |

Sniffin’ Sticks |

Retronasal psychophysical performances were evaluated by the application of 20 standardized odorant powders on the mobile part of the patient’s tongue *Total participants were 469, but the rest is hyposmia |

|||

|

(Rombaux et al. 2006b) Belgium |

1.5T Sigma Echospeed GEMS |

33 Pt. PIOD = 11 (5M/6F) 27–63 years Trauma = 11 (5M/6F) 20–60 years NP = 11 (4M/7F) 35–60 years HC = 11 (5M/6F) 22–61 years |

Nasal endoscopic | Sniffin’ Sticks |

Retronasal Psychological performance was evaluated using 20 stimuli Stimulants were applied to the midline of the tongue |

|

| (Mueller et al. 2005) |

31 Pt. RVI = 22 (9 M/13 F) (mean age, 57 years) Trauma = 9 (7 M/2 F) (mean age = 52 years HC = 17 (4 M/13 F) (mean age = 49 years) |

3–108 months | Sniffin’ Sticks | Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia | ||

|

(Bitter et al. 2010b) Germany |

3.0T Magnetom TrioTim 12-channel |

17 Pt. (6M/11F) 19–64 years Mean age: 49.6 ± 13.8 PIOD = 4 Trauma = 5 Idiopathic ` = 8 17 HC (6M/11F) 22–65 years Mean age: 40.4 ± 14.9 *Right-handed |

12–252 months | Nasal endoscopic | Sniffin’ Sticks | |

|

(Peng et al. 2013) China |

3T Siemens Trio Tim Magnetom 8-channel |

19 Pt. (5M/14F) 28–57 years Mean age: 45.3 ± 10.2 PIOD = 13 Trauma = 4 Idiopathic ` = 1 20 HC (6M/14F) 24–59 years Mean age: 43.6 ± 14.8 *Right-handed |

2–240 months | Toyota and Takagi olfactometry | ||

|

(Rombaux et al. 2012) Belgium |

3T Philips Achieva 8-channel |

60 Pt. (21M/39F) 24–79 years Mean age: 50 PIOD = 28 Trauma = 32 |

Sniffin’ Sticks Retronasal psychophysical olfactory tests |

|||

| Idiopathic olfactory loss | ||||||

|

(Liu et al. 2018) China |

3T Siemens Trio Tim Magnetom 12-channel |

20 Pt. (8M/12F) 26–77 years Mean age: 44 ± 12 20 HC (8M/12F) 23–69 years Mean age: 44 ± 12 |

Mean = 26.4 months 4–96 months |

Nasal endoscopic and paranasal sinus examination |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry |

|

|

(Rombaux et al. 2010a) Belgium |

1.5T Signa Echospeed, GEMS |

22 Pt. (9M/13F) 31–78 years Mean age: 53.7 22 HC (9M/13F) 28–77 years Mean age: 52.00 |

Mean = 8.4 months 3–19 months |

Sniffin’ Sticks |

Retronasal psychophysical performances (R), using odorized powders presented to the oral cavity so that orthonasal olfactory stimuli were avoided Parosmia in three Pt |

|

|

(Yao et al. 2014) China |

3T Siemens Trio Tim Magnetom 12-channel |

16 Pt. (9M/7F) 29–61 years Mean age: 48.6 ± 9.9 16 HC 32–60 years Mean age: 52.5 ± 8.7 *Right-handed |

6–120 months | Nasal endoscopic |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry Mini-Mental-State-Examination |

|

| Upper respiratory tract infection (postinfectious olfactory loss) | ||||||

|

(Yao et al. 2018) China |

3T Siemens Trio Tim Magnetom |

19 Pt. (5M/14F) 21–50 years Mean age: 37.7 ± 8.4 20 HC (8M/12F) 22–49 years Mean age: 35.4 ± 7.9 *Right-handed |

Mean = 49.2 ± 31.2 months 6–104.4 months |

Nasal endoscopic |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry Mini-Mental-State-Examination |

|

|

(Rombaux et al. 2006a) Belgium |

1.5T Signa Echospeed, GEMS | 11 Pt. |

Mean = 6 months 1–15 months |

Nasal endoscopic Otorhinolaryngological investigation |

Sniffin’ Sticks | |

|

(Rombaux et al. 2009a) Belgium |

1.5T Signa Echospeed, GEMS | 122 Pt. but only 50 Pt. with OB measurement | Sniffin’ Sticks | |||

| Congenital anosmia | ||||||

| (Karstensen et al. 2018) |

3 T Siemens Magnetom Verio 32-channel |

17 Pt. (6M/11F) Mean age: 49.1 ± 13.8 16 HC (7M/9F) Mean age: 47.2 ± 16.1 |

*Taste, vision and hearing examination |

Sniffin’ Sticks MoCA |

||

| (Yousem et al. 1996b) |

3 Pt. (borderline function) |

Sinonasal endoscopic |

UPSIT Mini-Mental Status Examination |

*Total participants were 25, but the rest is hyposmia | ||

| (Frasnelli et al. 2013) |

1.5T Siemens Sonata 8-channel |

17 Pt. (11M/6F) Mean age: 40.30 ± 17.6 17 HC (5M/12F) Mean age: 39.2 ± 14.4 |

Sniffin’ Sticks | |||

|

(Huart et al. 2011) Brussels |

1.5T Signa Echo Speed (Brussel) 1.5T Siemens Magnetom Vision (Dresden) |

36 Pt. (12M/24F) Mean age: 38 7–79 years old 70 HC (34M/36F) Mean age: 36.5 7–72 years old |

Sniffin’ Sticks | |||

|

(Abolmaali et al. 2002) Germany |

1.5T Siemens Magnetom Vision |

21 Pt. (2M/19F) Mean age: 29 12–73 years old 8 HC (4M/4F) Mean age: 24 21–27 years old |

Sniffin’ Sticks | |||

|

(Peter et al. 2020) Sweden and Netherlands |

3T Siemens Magnetom Prisma 20-channel (Swedish) 3T Siemens Magnetom Verio 32-channel (Netherland) |

33 Pt. (13M/21F) (1 Pt. removed due to abnormal anatomy) 34 HC (12M/22F) |

Sniffin’ Sticks |

24/34 individuals with ICA had received a diagnosis from a physician 27/34 lacked bilateral OB 3/34 had identifiable (albeit small) OB 4/34 non-determinable due to the limited spatial resolution of 1 mm3 |

||

| Traumatic brain injury | ||||||

| (Han et al. 2018) |

1.5T Siemens Sonata 8-channel |

24 Pt. (15M/9F) Mean age: 53.7 ± 13.7 22 HC (17M/5F) Mean age: 45 ± 13.9 |

Mean = 32.2 ± 22 months | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||

| (Miao et al. 2015) |

26 Pt. (15M/11F) Mean age: 40.08 ± 10.70 21 HC (12M/9F) Mean age: 42.52 ± 11.64 *Right-handed |

Mean = 11.5 months 10 days–108 months |

Nasal endoscopic |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry |

Side of head trauma: occipital (19 Pt.) | |

| (Rombaux et al. 2006b) | 1.5T Signa Echospeed GEMS | 20 Pt. |

Mean = 14.9 months 3–60 months |

Nasal endoscopic |

Sniffin’ Sticks Psychophysical tests of olfactory function assessed both for the orthonasal (olfactory perception during sniffing) and retronasal routes perception during eating, drinking |

*Only anosmia Pt. were included in this study |

|

(Yousem et al. 1999) USA |

36 Pt. (21M/15F) Mean age: 36 ± 11.40 24 HC (12M/12F) Mean age: 39 ± 11.50 |

Mean = 52 months ± 95.6 | Nasal endoscopic |

UPSIT Picture Identification Test 30-item Mini-Mental Status Examination |

||

|

(Yousem et al. 1996a) USA |

25 Pt. (14M/11F) Mean age: 36 ± 9.80 |

3–183 months | Nasal endoscopic |

UPSIT Picture Identification Test 30-item Mini-Mental Status Examination |

||

|

(Jiang et al. 2009b) Taiwan |

1.5T Exite GEMS |

54 Pt. (32M/22F) 17–60 years Mean age: 39 30 HC (24M/6F) 20–79 years Mean age: 43.4 *Right-handed |

1–125 months | Nasal endoscopic | Phenyl ethyl alcohol (PEA) *odor detection threshold | |

| (Doty et al. 1997) |

148M Mean age: 40.4 ± 16.2 120F Mean age: 42.3 ± 17.8 |

UPSIT | ||||

Pt. patient, CRS chronic rhinosinusitis, RVI respiratory viral infection, IOL idiopathic olfactory loss, PIOD postinfectious olfactory dysfunction, NP nasal polyposis, HC healthy control, OB olfactory bulb, OS olfactory sulcus, GM gray matter, SFS superior frontal sulcus, MFG middle frontal gyrus, UPSIT University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test

*Sinonasal endoscopy was evaluated to exclude obstructive or inflammatory causes of smell dysfunction

All studies used validated measures to measure olfactory outcomes. Twenty-two studies used a standardised measure of olfactory function in their cohort, the “Sniffin’ Sticks”. The test is composed of three parts: odour threshold for n-butanol or phenyl ethyl alcohol (T), odour discrimination (D), and odour identification (I). The final score is expressed as the sum of the T, D, and I value. Five studies used “T&T olfactometry” (Kondo et al. 1998), and four studies used the University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) (Doty et al. 1984). Seven studies included symptom questionnaires and other assessments such as the Sino-Nasal Outcome Questionnaire of Olfactory Disorder (QOD) (Frasnelli and Hummel 2005), picture identification test, mini-mental status examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al. 1975), and MoCA test (Nasreddine et al. 2005).

OB volume

In the present study, we note that the measuring technique used to measure the OB volume can make a difference to the outcomes. Moreover, none of the studies reported the details of the method used. However, we expected that differences between the techniques are within an acceptable range. The MRI and psychophysical result of patients with anosmia, including the OB volume and OS depth, are provided in Table 2. The range of OB volume for IOL patients on the right is between 26.90 mm3 and 31.94 ± 3.33 mm3 and 26.50 mm3 to 31.68 ± 3.24 mm3 for the left. Patients with URTI, 29.20 ± 7.20 mm3 on the right and 26.90 ± 5.80 mm3 on the left hemisphere (Rombaux et al. 2006a, b, c). One study reported combining the right and left OB volume, 49.20 ± 20.10 mm3 (Rombaux et al. 2009a, b). Patients with TBI show a wide range of OB volumes; 19.20 ± 9.10 mm3 to 45.20 mm3 for the right and 17.60 ± 9.70 mm3 to 46.30 mm3 for the left hemisphere. Compared to other etiologies, patients with congenital anosmia shows the smallest OB volumes; 19.74 ± 21.16 mm3 for the right and 21.15 ± 23.83 mm3 for the left hemisphere (Karstensen et al. 2018). When comparing the average OB volumes between left and right hemispheres with aetiology, OB volume on the right side was larger in IOL, URTI, and TBI. However, congenital anosmia shows a contradictory result where the OB volume is more prominent on the left. Results also show that the OB volumes differ in relation to the cause of the olfactory disorder. As predicted, relative to healthy controls, patients with anosmia had significantly smaller OB volumes. The range of OB volume in healthy controls is between 37.90 mm3 and 93.50 mm3 on the right and 36.60 mm3 and 91.60 mm3 on the left. The typical human OB volume is about 58 mm3 and contains about 5500 glomeruli (Weiss et al. 2019). Interestingly, there are people with a functioning sense of smell but without OB or radically small OB (Rombaux et al. 2009b). The studies suggested that very few people can perform basic olfaction even without OB, implying plasticity in the functional neuroanatomy of the sensory system (Weiss et al. 2020).

Table 2.

MRI and psychophysical result of patients with anosmia with various etiology and healthy control group

| Author | Anosmia patients | Healthy control | Psychophysical, physiological tests and questionnaire and notes | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Olfactory bulb volume (mm3) | Olfactory sulcus depth | Sniffin Sticks Score | Olfactory bulb volume (mm3) | Olfactory sulcus depth | Sniffin Sticks Score | ||||||||||||

| R | L | R | L | Total | T | D | I | R | L | R | L | Total | T | D | I | ||

| Various etiology | |||||||||||||||||

| (Chung et al. 2018) | 15.3 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 5.5 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||||||

| (Goektas et al. 2009) | 3.28 ± 4.29 | 2.8 ± 5.24 | 4.00 ± 2.61 | Sniffin’ Sticks | |||||||||||||

| (Fonteyn et al. 2014) | 16.0 (15.4–16.7) |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia |

|||||||||||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2006b) | 50.67 | 72.90 |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of all participants |

||||||||||||||

| (Mueller et al. 2005) |

Trauma = 52.2 RVI = 57.5 |

Trauma = 54.5 RVI = 58.5 |

Trauma = 11.3 RVI = 18.4 |

93.5 | 91.6 | 31.6 |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia |

||||||||||

| (Bitter et al. 2010b) | 10.2 ± 2.7 | 14.9 ± 1.3 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||||||||

| (Peng et al. 2013) |

T&T score > 5.5 |

T&T score − 1.0–1.2 |

Toyota and Takagi olfactometry | ||||||||||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2012) |

Trauma = 50.30 PIOD = 67.56 |

Trauma = 17.3 PIOD = 20.6 |

Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||||||||

| Ideopathic olfactory loss | |||||||||||||||||

| (Liu et al. 2018) | 31.94 ± 3.33 | 31.68 ± 3.24 | 14.16 ± 5.42 |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry |

|||||||||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2010a) | 26.90 | 26.5 | 8.80 | 8.90 | 14.50 | 2.60 | 5.90 | 6.00 | 37.90 | 36.60 | 9.10 | 8.70 | 30.40 | 7.40 | 10.50 | 12.60 | Sniffin’ Sticks |

| (Yao et al. 2014) |

9.4 ± 3.6 T&T: 5.8 ± 0.2 |

29.9 ± 1.3 T&T: 0.6 ± 0.4 |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry |

||||||||||||||

| Upper respiratory tract infection | |||||||||||||||||

| (Yao et al. 2018) | 4.80 ± 2.40 |

Sniffin’ Sticks Toyota and Takagi olfactometry |

|||||||||||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2006a) | 29.20 ± 7.2 | 26.90 ± 5.8 | 9.50 ± 1.9 | 8.60 ± 2.0 | 17.50 ± 5.20 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 6.8 ± 2.7 |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia |

||||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2009a) | 49.20 ± 20.1 | 18.50 ± 6.8 | 3.1 ± 1.9 | 7.7 ± 3.1 | 7.6 ± 2.3 |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia |

|||||||||||

| Congenital anosmia | |||||||||||||||||

| (Karstensen et al. 2018) | 19.74 ± 21.16 | 21.15 ± 23.83 | 4.20 ± 3.25 | 3.33 ± 3.34 | 15.43 ± 4.99 | 2.43 ± 2.06 | 7.23 ± 2.38 | 5.71 ± 2.20 | 56.45 ± 21.51 | 59.41 ± 21.18 | 6.89 ± 2.42 | 6.63 ± 2.31 | 31.59 ± 4.80 | 8.09 ± 2.36 | 12.38 ± 2.23 | 11.13 ± 2.13 | Sniffin’ Sticks |

| (Yousem et al. 1996b) |

UPSIT score L: 5.2, R: 5.2, and total: 10.5 |

UPSIT score L: 18.5, R: 18.1, and total: 36.6 |

UPSIT | ||||||||||||||

| (Huart et al. 2011) | 5.50 ± 3.40 | 5.30 ± 3.40 | 13.40 ± 4.10 | 12.40 ± 3.40 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||||||

| (Abolmaali et al. 2002) | 6.40 ± 3.40 | 5.00 ± 1.40 | 8.90 ± 1.40 | 8.80 ± 1.50 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||||||

| (Peter et al. 2020) | 5.8 (3.6) | 4.9(3.3) | 10.9 (2.3) | 1.2 (0.5) | 4.9 (1.6) | 4.8 (1.5) | 8.8 (2.3) | 8.6 (2.3) | 35.4 (3.8) | 8.7 (3.2) | 13.5 (1.6) | 13.4 (1.3) | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||

| Traumatic brain injury | |||||||||||||||||

| (Han et al. 2018) | 11.3 ± 2.70 | 1.1 ± 0.30 | 6.3 ± 2.30 | 3.9 ± 1.60 | 33.8 ± 3.10 | 7.8 ± 2.20 | 12.4 ± 1.70 | 13.6 ± 1.30 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||||

| (Miao et al. 2015) | 27.41 ± 8.66 | 29.75 ± 9.07 | 8.18 ± 1.18 | 4.48 ± 1.45 | 5.38 ± 2.826 | 51.58 ± 16.93 | 49.95 ± 15.79 | 7.45 ± 1.34 | 6.70 ± 1.36 | 32.05 ± 2.89 | Sniffin’ Sticks | ||||||

| (Rombaux et al. 2006b) | 19.20 ± 9.1 | 17.6 ± 9.7 | 12.00 ± 5.8 | 2.52 ± 1.5 | 4.96 ± 2.30 | 4.64 ± 2.90 |

Sniffin’ Sticks *Results are a combination of anosmia and hyposmia |

||||||||||

| (Jiang et al. 2009b) | 45.2 | 46.3 | 59.7 | 66.0 | Phenyl ethyl alcohol (PEA) *odour detection threshold | ||||||||||||

| (Doty et al. 1997) |

UPSIT score: Back of the head: 15.38 ± 7.96 Side of the head: 16.31 ± 9.99 Front of the head: 19.90 ± 10.67 |

UPSIT | |||||||||||||||

L left, R right, HC healthy control, OFC orbital frontal cortex, Pt. patient, OB olfactory bulb, TDI score Threshold-Discrimination-Identification score, T threshold, D discrimination, I identification, OD olfactory dysfunction, IOL idiopathic olfactory loss, RVI respiratory viral infection, UPSIT University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test,

*Variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation unless mentioned

Most of the studies demonstrated a positive correlation between OB volume and olfactory function across the etiologies, details in Table 3. However, in an older study, Doty et al. (1997) found that this correlation is only present in male patients. The study reported TBI patients with a large sample size, 148 males and 120 females. Four studies reported the association between OB volume and the duration of olfactory loss. A positive correlation was found in Rombaux et al. which reported 11 patients with URTI and olfactory loss duration ranging between 1 and 15 months. The others reported a different finding. Yao et al. (2018) reported this dissociation only in the right OB and right olfactory cortex (OFC) and reported 19 patients with URTI. The duration of olfactory loss ranged between 6 and 104 months. Furthermore, both Goektas et al. (2009) and Chung et al. (2018) reported an inverse correlation between OB volume and the duration of olfactory dysfunction. Both studies reported anosmia with various etiologies with small sample sizes; 10 and 34 patients, respectively. The olfactory loss duration reported in Goektas et al. ranged between 7 and 600 months and in Chung et al. between 2 and 552 months. Goektas et al. (2009) agreed that the outcomes could be due to the small study population.

Table 3.

Summary of the association between OB volume, OS depth, and TDI score across anosmia with various etiologies

| No. | Main findings | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Various etiology | |||

| (Chung et al. 2018) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume and TDI score - Negative correlation between OB volume with a duration of olfactory loss and age - Negative correlation between an olfactory function with aetiology and age |

||

| (Hummel et al. 2015) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume and TDI score - Positive correlation between OB volume and olfactory function - Positive correlation between R OS depth and olfactory function but NOT L OS depth - Negative correlation between OS depth and age |

Assessment of the OB volume and OS depth produces useful clinical indicators of olfactory dysfunction | |

| (Goektas et al. 2009) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume and olfactory function - Negative correlation between OB volume and TDI score - Negative correlation between OB volume and duration of olfactory loss - Negative correlation between OB volume with etiologist |

*These findings are a sharing finding between anosmia and hyposmia | |

| (Fonteyn et al. 2014) | - Positive correlation between orthonasal and retronasal score | *These findings are a sharing finding between anosmia and hyposmia | |

| (Rombaux et al. 2006b) | - Positive correlation between OB volume with both orthonasal and retronasal score | ||

| (Mueller et al. 2005) | - Positive correlation between OB volume with olfactory function | Reduced OB volumes may also be characteristic of parosmia | |

| (Bitter et al. 2010b) |

- Positive correlation between GM volume with disease duration - Positive correlation between GM volume with olfactory function |

GM areas involved were nucleus accumbens, MPC including the MCC and ACC, DLPFC, piriform cortex, insular cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and cerebellum Patients with disease duration longer than 2 years showed stronger atrophy in these areas compared with patients who were anosmic less than 2 years |

|

| (Peng et al. 2013) |

- Positive correlation between GM and WM volume with disease duration - Positive correlation between GM volume with olfactory function |

Different GM and WM areas have different sensitivities to olfactory injury GM areas involved were ACG, MTG, STG, fusiform gyrus, SMG, SFG, MFG, MOG, anterior-insular cortex, cerebellum, piriform cortex, ITG, precuneus, and subcallosal gyrus |

|

| (Rombaux et al. 2012) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume with both orthonasal and retronasal score - Positive correlation between OB volume with olfactory functions |

OB volume is suggested to be a predictor of olfactory recovery in patients with postinfectious and post-traumatic olfactory loss With larger volumes → greater improvement of olfactory function |

|

| Idiopathic olfactory loss | |||

| (Liu et al. 2018) |

- No difference in OS depth between IOL and HC in both sides of the brain - No difference in OB volume between in both hemisphere of the two groups |

||

| (Rombaux et al. 2010a) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume with odour thresholds in both groups - Positive correlation between OB volume with olfactory function |

||

| (Yao et al. 2014) |

- Negative correlation between the two olfactory tests: higher scores for T&T and lower scores for SS compared to HC - Positive correlation between GM volume with olfactory function |

GM areas involved were OFC ACC, insular cortex, parahippocampal cortex, and piriform cortex | |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | |||

| (Yao et al. 2018) |

- Negative correlation between R OB volume with a duration of olfactory loss - Negative correlation between R OFC volume with a duration of olfactory loss |

||

| (Rombaux et al. 2006a) | - Positive correlation between OB volume with olfactory function and duration of olfactory loss | ||

| (Rombaux et al. 2009a) | -Positive correlation between OB volume with orthonasal and retronasal score | ||

| Congenital anosmia | |||

| (Karstensen et al. 2018) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume and OS depth with olfactory function - Positive correlation between an olfactory function with a volume of R posterior cingulate and parahippocampal cortex |

Lifelong olfactory deprivation trigger changes in GM of prefrontal and limbic cortices - Larger GM volume of the L MFG and in R SFS - Larger GM volume of the R piriform cortex - Smaller GM volume in the L posterior olfactory sulcus within the mOFC Whole-brain analyses - Larger GM volume of the R SFS and L MFG |

|

| (Yousem et al. 1996b) |

- Positive correlation between an olfactory function with temporal and/or frontal lobe volume loss - Absence of OB and OT (68–84%) in all Pt |

Eight individuals had Kallmann’s syndrome (hypogonadotropic hypogonadism with anosmia) Congenital anosmia or hyposmia appears to be an olfactory bulb olfactory tract phenomenon rather than a cerebral process *These findings are a sharing finding between anosmia and hyposmia |

|

| (Frasnelli et al. 2013) |

- Negative correlation between GM volume with olfactory function (thicker medial orbitofrontal cortex bilaterally, denser, and thicker left piriform cortex, left entorhinal cortex, smaller cortical thickness of the posterolateral) - Negative correlation between WM volume with olfactory function (increased WM density of the left superior longitudinal fasciculus in an area posteromedial to the left insula, as well as of an area posterior to the parietal operculum) |

||

| (Huart et al. 2011) | - Positive correlation between OS depth with olfactory function (decrease OS depth) |

The depth of the OS is a useful clinical indicator and 8 mm clearly indicates isolated anosmia 10 Pt. with IA had OS deeper than 8 mm, and 26 Pt. had smaller than 8 mm None of the healthy controls exhibited a depth of 8 mm |

|

| (Abolmaali et al. 2002) |

- Positive correlation between OS depth with olfactory function (decrease OS depth) - Depth of the OS was more significant on the right than on the left, and there was no overlap - Depth of the OS differed between those with and those without visible OT |

The present study speculates that olfaction may be processed predominantly in the right hemisphere | |

| (Peter et al. 2020) |

- Negative correlation between GM volume with olfactory function (increased GM volume and cortical thickness in the medial orbital gyri; regions associated with olfactory processing, sensory integration, and value-coding) - Positive correlation between GM volume with olfactory function (GM atrophy in bilateral olfactory sulci, explained by decreased cortical area, curvature, and sulcus depth) |

||

| Traumatic brain injury | |||

| (Han et al. 2018) |

- Negative correlation between OB volume and TDI score - Positive correlation between GM volume with disease duration (frontal and temporal gyrus) - Positive correlation between GM volume with olfactory function (in primary and secondary olfactory areas including gyrus rectus, medial OFC, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and cerebellum) |

Pt. with anosmia more frequent lesions in OB, OFC, and temporal lobe pole compared to hyposmia and HC | |

| (Miao et al. 2015) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume with olfactory function - Positive correlation between R OS depth with olfactory function - Positive correlation between OB volume and OS depth with age |

||

| (Rombaux et al. 2006b) |

- Positive correlation between OB volume and retronasal - Negative correlation between OB volume and orthonasal |

*These findings are a sharing finding between anosmia and hyposmia Pt. with anosmia had smaller OB volumes than Pt. with hyposmia |

|

| (Yousem et al. 1999) | - Positive correlation between left OB volume, OT, and total UPSIT scores |

OB, OT, and frontal lobe encephalomalacia coexist in many Pt *These findings are a sharing finding between anosmia and hyposmia |

|

| (Yousem et al. 1996a) | - Negative correlation between OB volume and individual olfactory test scores | Pt. without smell function had more significant volume loss in OB and OT than did those trauma Pt. who retained some sense of smell | |

| (Jiang et al. 2009b) | - Positive correlation between OB volume and olfactory loss |

Findings indicate that a loss of peripheral sensory input may have resulted in reduced OB volume in Pt A high incidence of sub-frontal lobe damage concurred in Pt |

|

| (Doty et al. 1997) | - Positive correlation between OB volume and OT volume with olfactory loss in male patients (but not female) |

Pt. complaint olfactory dysfunction typically have anosmia and rarely regain the normal olfactory ability Frontal impacts produced less dysfunction than back or side impacts |

|

Pt. patient, IA isolated anosmia, CR Chronic rhinosinusitis, RVI respiratory viral infection, IOL idiopathic olfactory loss, NP nasal polyposis, HC healthy control, OB olfactory bulb, OS olfactory sulcus, OT olfactory sulcus, GM gray matter, WM white matter, SFS superior frontal sulcus, MFG = middle frontal gyrus, MPC medial prefrontal cortex, DLPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, MTG middle temporal gyrus, STG superior temporal gyrus, SMG supramarginal gyrus, SFG superior frontal gyrus, MOG middle occipital gyrus, MCC middle cingulate cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, SFS superior frontal sulcus, UPSIT University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test, T&T Toyota and Takagi, SS Sniffin’ Sticks

*Retronasal = odorant was presented to the oral cavity so that orthonasal and gustatory stimuli were avoided

*Orthonasal = e.g. Sniffin’ sticks task

Most selected studies do not evaluate the correlation between OB volume and ageing exclusively. Chung et al. (2018) reported anosmia with various etiologies and found no correlation between OB volume and age. In contrast, Miao et al. (2015) reported that older patients had smaller OB volume; however, the result cannot be concluded due to TBI or natural ageing. There is a correlation between OB volume and age in healthy participants, although this is not particularly strong (Çullu et al. 2020; Kondo et al. 2020). However, for patients with olfactory dysfunction, the correlation between OB volume and age is challenging to evaluate due to the underlying olfactory loss.

Finally, seven studies (64%) reported a positive correlation between OB volume and TDI scores. The remaining four studies observed no correlation between both OB volume and TDI score (Rombaux et al. 2006a, b, c; Han et al. 2018; Yousem et al. 1996a; Goektas et al. 2009).

OS depth

The average OS depth in patients with IOL is 8.80 mm for the right and 8.90 mm for the left (Rombaux et al. 2010a, b). For URTI, the mean right depth is 9.50 ± 1.90 mm and 8.60 ± 2.00 mm for the left hemisphere. OS depths for patients with TBI are 8.18 ± 1.18 mm for the right and 4.45 ± 1.45 mm for the left. Compared to other aetiologies, congenital anosmia shows the shallowest OS depth, between 4.20 ± 3.25 mm and 6.40 ± 3.40 mm for the right and 3.33 ± 3.34 mm and 5.30 ± 3.40 mm for the left; the details are tabulated in Table 2.

Five studies of both congenital and acquired anosmia repored the association between OS depth and olfactory function. Three studies reported a positive correlation (Karstensen et al. 2018; Huart et al. 2011; Abolmaali et al. 2002), and reported patients with congenital anosmia with sample sizes: 17, 36, and 21 patients, respectively. Two studies found that only the right OS correlates with olfactory function (Hummel et al. 2015; Miao et al. 2015). Hummel et al. reported anosmia with various etiologies in a large pool of patients (n = 378), and Miao et al. reported TBI patients with 26 patients.

Voxel-based morphometry

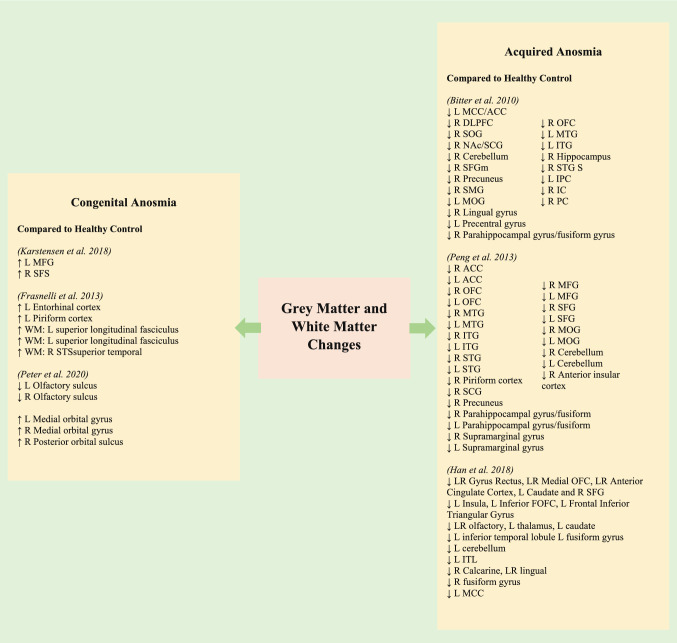

Nine studies evaluated voxel-based morphometry (VBM). Three studies of patients with congenital anosmia exhibit larger GM volumes in a few regions such as the left medial frontal gyrus (MFG), right superior frontal sulcus (SFS) (Karstensen et al. 2018), left entorhinal cortex, left piriform cortex (Frasnelli et al. 2013) bilateral medial orbital gyrus (MOG) and right posterior orbital sulcus (POS) (Peter et al. 2020). Furthermore, this study also reported larger WM density in the areas, including the left insula and the region posterior to the parietal operculum (Frasnelli et al. 2013). These findings were in contrast to those observed in patients with acquired anosmia, where the reduced olfactory function is associated with reduced GM and WM volumes and thickness (Han et al. 2018; Bitter et al. 2010a, b; Peng et al. 2013). The areas that show a reduction in GM volume and density were including gyrus rectus, medial orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), anterior cingulate cortex, insula, and cerebellum (Bitter et al. 2010a, b; Peng et al. 2013; Yao et al. 2014; Han et al. 2018). Details of the GM/WM areas and size are shown in Table 4 and Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Summary of studies included in which VBM has been used to assess changes and alteration in the olfactory system

| Author | VBM (cm3) |

|---|---|

| Various etiology | |

| (Bitter et al. 2010b) |

Anosmia < HC (p < 0.001) L MCC/ACC = 16,663 (cluster size) R DLPFC = 3112 (cluster size) R SOG = 1750 (cluster size) R NAc/SCG = 1667 (cluster size) R Cerebellum = 1605 (cluster size) R SFGm = 933 (cluster size) R Precuneus = 850 (cluster size) R SMG = 772 (cluster size) L MOG = 754 (cluster size) R Lingual gyrus = 648 (cluster size) L Precentral gyrus = 638 (cluster size) R Parahippocampal gyrus/fusiform gyrus = 453 (cluster size) R OFC = 347 (cluster size) L MTG = 330 (cluster size) L ITG = 280 (cluster size) R Hippocampus = 213 (cluster size) R STG S = 140 (cluster size) L IPC = 126 (cluster size) R IC = 112 (cluster size) R PC = 90 (cluster size) |

| (Peng et al. 2013) |

Anosmia < HC (p < 0.001) R ACC = 48 (cluster size) L ACC =519 (cluster size) R OFC = 11 (cluster size) L OFC = 463 (cluster size) R MTG = 679 (cluster size) L MTG = 279 (cluster size) R ITG = 60 (cluster size) L ITG = 160 (cluster size) R STG = 1987 (cluster size) L STG = 2287 (cluster size) R MFG = 731 (cluster size) L MFG = 477 (cluster size) R SFG = 158 (cluster size) L SFG = 34 (cluster size) R MOG = 164 (cluster size) L MOG = 78 (cluster size) R Parahippocampal gyrus/fusiform gyrus = 398 (cluster size) L Parahippocampal gyrus/fusiform gyrus = 345 (cluster size) R Supramarginal gyrus = 249 (cluster size) L Supramarginal gyrus = 862 (cluster size) R Cerebellum = 262 (cluster size) L Cerebellum = 151 (cluster size) R Anterior insular cortex = 1023 (cluster size) R Piriform cortex = 25 (cluster size) R SCG = 28 (cluster size) R Precuneus = 133 (cluster size) |

| Idiopathic olfactory loss | |

|

(Yao et al. 2014) China |

Pt.: Average total brain volume: 1139.6 ± 76.7 Mean GM volume: 560.5 ± 49.6 HC: Average total brain volume: 1141.9 ± 95.8 Mean GM volume: 599.8 ± 48.4 Both whole brain and GM volume alterations were not different between 2 groups |

| Upper respiratory tract infection (postinfectious olfactory loss) | |

| (Yao et al. 2018) |

Average total brain volume: 1126.1 ± 64.9 GM volume: 542.9 ± 36.7 |

| Congenital anosmia | |

| (Karstensen et al. 2018) |

Congenital anosmia > HC (pcorrected < 0.05) L MFG = 1236 (cluster size) R SFS = 943 (cluster size) |

| (Frasnelli et al. 2013) |

Congenital anosmia > HC (p < 0.001) L Entorhinal cortex = 28 (cluster size) L Piriform cortex = 12 (cluster size) WM: L superior longitudinal fasciculus = 534 (cluster size) WM: L superior longitudinal fasciculus = 134 (cluster size) WM: R STSsuperior temporal = 3 (cluster size) |

| (Peter et al. 2020) |

Congenital anosmia < HC pcorrected < 0.05 L Olfactory sulcus = 2185 (cluster size) R Olfactory sulcus = 2135 (cluster size) Congenital anosmia > HC pcorrected < 0.05 L Medial orbital gyrus = 532 (cluster size) R Medial orbital gyrus = 244 (cluster size) R Posterior orbital sulcus = 8 (cluster size) * Cluster size has unit mm3 |

| Traumatic brain injury | |

| (Han et al. 2018) |

HC > anosmia (puncorrected < 0.001) LR Gyrus Rectus, LR Medial OFC, LR Anterior Cingulate Cortex, L Caudate and R SFG = 5403 (cluster size) L Insula, L Inferior FOFC, L Frontal Inferior Triangular Gyrus = 881 (cluster size) LR olfactory, L thalamus, L caudate = 472 (cluster size) L inferior temporal lobule L fusiform gyrus = 317 (cluster size) L cerebellum = 179 (cluster size) L ITL = 219 (cluster size) R Calcarine, LR lingual = 141 (cluster size) R fusiform gyrus = 110 (cluster size) L MCC = 101 (cluster size) |

| (Yousem et al. 1996a) |

Pt.: Average total brain volume (temporal lobe) 69 864.5 mm3 Mean total brain volume right and left hemisphere (25 patients): 70 094 mm3 and 69 635 mm3, respectively (SD, 8216 mm3 and 10 516 mm3, respectively) |

L left, R right, OFC orbital frontal cortex, Pt. patient, OB olfactory bulb, TDI score Threshold-Discrimination-Identification score, T threshold, D discrimination, I identification, OD olfactory dysfunction, IOL idiopathic olfactory loss, GM gray matter, ERPs event related potentials, oERPs olfactory event related potentials, SFS superior frontal sulcus, MFG middle frontal gyrus, MPC medial prefrontal cortex, DLPFC dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, MTG middle temporal gyrus, STG superior temporal gyrus, SMG supramarginal gyrus, SFG superior frontal gyrus, MOG middle occipital gyrus, MCC middle cingulate cortex, ACC anterior cingulate cortex, ITG inferior temporal gyrus, SFS superior frontal sulcus, MPC medial prefrontal cortex, SCG subcallosal gyrus, NAc = nucleus accumbens, SOG = superior occipital gyrus, IC = anterior insular cortex, SMG = supramarginal gyrus

Fig. 2.

Diagram of the grey matter and white matter alteration in congenital and acquired anosmia

A positive correlation between disease duration and GM atrophy was reported. Two studies found that longer disease duration was associated with stronger atrophy in GM, and these studies reported patients with various etiologies. Bitter et al. (2010a, b) further proposed that patients with disease duration longer than 2 years showed more robust atrophy than patients who were anosmic for less than 2 years. The areas included the nucleus accumbens, the medial prefrontal cortex (MPC), and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC). All the involved regions are part of the basal ganglia limbic loop, except the DLPFC, a secondary olfactory area. GM volume reduction in the piriform cortex, insular cortex, orbitofrontal cortex, hippocampus, parahippocampal gyrus, supramarginal gyrus, and cerebellum was also reported (Peng et al. 2013; Bitter et al. 2010a, b).

Discussion

This present review is the first systematic review summarising the evidence of anatomical changes of the brain following congenital and acquired anosmia. The heterogeneity of the findings was high due to the differences in factors, including population, aetiology, and the complexity of brain interaction with the respective disorders. Despite these differences, olfactory bulb volume was found to be consistently associated with olfactory function. The most interesting findings were the larger volumes of GM and WM in a few areas related to olfactory processing, sensory integration, and higher-order olfactory memory (prefrontal and limbic cortices) in congenital anosmic patients. This finding contrasts with smaller GM and WM volumes in patients with acquired olfactory loss.

Anosmia related to structural alteration

OB, OS, and olfactory function

The present review demonstrated that both right and left OB volumes were significantly smaller in anosmic patients than healthy controls. The difference is likely due to the decline of sensory input from the periphery to the OB, leading to decreased olfactory neurons passing through the cribriform plate (Schofield et al. 2014). This is likely when the olfactory fibres are damaged after TBI or when metaplasia developed within the olfactory neuroepithelium after a URTI (Mueller et al. 2005). Among all aetiologies, the most altered OB volume was observed in patients with congenital anosmia, followed by TBI (which has a broader range of OB volume); however, URTI and IOL show equal OB volume range. Possible explanations are discussed below.

The right OB volumes were larger in patients with IOL, URTI, and TBI. However, the observation was the opposite in patients with congenital anosmia except in one study (Karstensen et al. 2018). Possibly, there was no OB visible, or the OB was too small or too variable in congenital anosmic patients to allow for consistent volumetrics (Boesveldt et al. 2017). For patients with IOL, URTI, and TBI, this finding is in line with some evidence demonstrating that the right hemisphere is more critical for higher-order processing of smell sensation (Jones-Gotman and Zatorre 1993; Zatorre et al. 1992; Hummel et al. 2015). The absence of the OB in congenital anosmia patients can be explained by aplasia or hypoplasia of OB (Yousem et al. 1996b). Structural alterations in congenital anosmic patients are not only limited to OB volume, but also in OS depth. The OS depth, located between the medial orbital gyrus and gyrus rectus in the frontal lobe and positioned over the olfactory tract and OB, is considered another significant parameter for evaluating the olfactory processing system with MRI (Karstensen et al. 2018). The OS depth is reduced in anosmic patients (Abolmaali et al. 2002; Buschhüter et al. 2008). This is further supported by the observation that patients with congenital anosmia show the smallest OB volume and shallow OS depth than other aetiologies. The present review also observes that OS depth is consistently deeper on the right compared to the left side (Hummel et al. 2003). The present study observed a similar pattern of this laterality in healthy controls. Furthermore, lateralisation of OS depth may correlate to functional lateralisation in the olfactory system (Hummel et al. 2003). The same finding was observed in previous studies (Rombaux et al. 2006a, b, c; Abolmaali et al. 2002; Peter et al. 2020), supporting the idea of lateralised differences in structures involved in the processing of olfactory information. Besides, there is evidence that suggests the right hemisphere is more important to the sense of smell (Abolmaali et al. 2001) than the left (Sobel et al. 1999; Yousem et al. 1999; Zatorre et al. 1992). This idea is also supported by observations suggesting that the right hemisphere is better at ‘holistic’ or ‘global’ processing and the left hemisphere at ‘local’ processing (Arnold et al. 2020).

Compared to other aetiologies, patients with post-TBI show a broader range of OB volume. The possible explanations are the severity and location of the injury. Previous studies also suggested that the injury’s location may influence the outcomes, with frontal lesions leading to a lower degree of dysfunction than injuries in the head’s back or side (Fujii et al. 2002; Doty et al. 1997). Also, the duration of olfactory dysfunction data ranges between 10 days and 183 months (Table 1). A previous study reported many TBI patients with olfactory dysfunction remain undiagnosed for a long time, probably due to the lack of rehabilitative and diagnostic services for patients suffering from olfactory dysfunction (Schofield et al. 2014). Moreover, TBI is associated with the initiation of complex pathophysiological mechanisms (Gardner et al. 2017).

The OB is the first relay station in the olfactory pathway, connecting the peripheral olfactory system and other cortical structures. In agreement with previous research, the present review confirmed the correlation between OB volume and olfactory functions. Furthermore, more than half of the studies (64%) reported a correlation between OB volume and psychophysical tests of olfactory function, again strongly confirming previous works. Previous studies also considered the OS’s depth is another relevant parameter for evaluating olfactory function (Huart et al. 2011; Abolmaali et al. 2002). However, only seven studies reported OS’s depth, and the present review observed mixed findings. Therefore, it is suggested that the combined evaluation of OB volume and OS depth may be valuable in the differential assessment of patients with olfactory dysfunction.

Comparison between aetiology on GM and WM atrophy

For the primary olfactory cortex; Peng et al. (2013) and Bitter et al. (2010a, b) found piriform cortex atrophy on the right GM; both studies reported anosmic with various aetiology. Yao et al. (2014) reported patients with IOL and found a smaller GM volume in the left piriform cortex. The inconsistent findings of the piriform cortex were also observed in congenital anosmia. There was a larger volume in the left (Frasnelli et al. 2013) or right piriform cortex (Karstensen et al. 2018), or no difference was found (Peter et al. 2020). The current observation indicates that the piriform cortex is particularly vulnerable in patients with dysfunctional olfactory processing, and both hemispheres were affected.

In the secondary olfactory areas, Peng et al. (2013) observed GM atrophy in the right insular cortex, left anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and left orbital frontal cortex (OFC). Bitter et al. (2010a, b) reported GM atrophy in the right insular cortex, and right OFC. Yao et al. (2018) and Bitter et al. (2010a, b) observed a similar GM volume reduction pattern in the right OFC. Yao et al. (2014) included patients with URTI and further observed smaller GM volume in the insular cortex, OFC, and ACC. ACC is closely related to olfactory sensations, and the ACC has been called a key node in the flavour network (Gottfried and Zelano 2011; Shepherd 2006). All three congenital anosmia studies also observed alterations in GM volume in OFC. One study shows a larger GM volume in bilateral OFC (Frasnelli et al. 2013); reduced volume in the left medial OFC (Karstensen et al. 2018), and significantly altered morphology in bilateral medial OFC, and larger GM volume (Peter et al. 2020). Peng et al. (2013) found WM atrophy which was more pronounced in the left ACC and OFC. Several functional imaging studies have shown more robust GM activity in the right insular cortex during olfactory tasks, which might be explained by laterality in olfactory processing at the insular cortex (Hummel et al. 2005; Bengtsson et al. 2001; Wang et al. 2005). Previously OFC has been suggested to play an essential role in various aspects of olfactory processing (Potter and Butters 1980). The right OFC is mainly involved in complex olfactory tasks, e.g., the distinction between the smells of predator and kin (Gottfried and Zelano 2011). The OFC is involved in olfactory processing and several other complex functions such as emotional control, emotion-guided behaviours, and decision-making (Nogueira et al. 2017). Insular cortex contributes to odour quality coding (Veldhuizen et al. 2010). This is by representing the taste-like aspects of food odours (Veldhuizen et al. 2010). Therefore, GM and WM volume reduction in the insular cortex may be associated with impaired performance to correctly assess sensory information quality, including gustatory and olfactory sensations (Bitter et al. 2010a, b).

Peng et al. also found atrophy in other areas, such as the middle occipital gyrus and precuneus, in addition to these primary and secondary olfactory areas. These areas are suggested to be involved in the recall of episodic memories during olfactory matching. Peng et al. (2013) and Bitter et al. (2010a, b) also observed GM and WM atrophy in the cerebellum and was more dominant in the right-sided. The cerebellum is suggested to receive olfactory information for modulating sniffing, which, in turn, modulates olfactory input (Sobel et al. 1998). Cerebellum also plays an essential role in chemosensory processing (Zhou and Chen 2008). Bitter et al. (2010a, b) reported atrophy in areas involved in olfactory memory such as dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), superior temporal gyrus (STG), superior frontal gyrus (SFG), lingual area, inferior parietal lobule, SMG, hippocampus and parahippocampal gyrus. These areas tend to exhibit stronger right-sided atrophy.

The present study observed that GM and WM alteration involved primary and secondary olfactory areas and few additional areas related to olfactory processing. We further observed that this brain alteration affects both hemispheres and is more pronounced with longer disease duration (Bitter et al. 2010a, b; Peng et al. 2013)—although these conclusions are based on cross-sectional investigations. The present study also observed inconsistent findings in terms of brain laterality. We proposed that both hemispheres were involved but with differential contributions, and that the alterations occur at a different pace. Our proposal is supported by a previous study reporting that some patients with an initially unilateral reduced sense of smell developed into a bilateral olfactory loss over several months or years (Gudziol et al. 2010).

Comparison of GM and WM atrophy between congenital and acquired anosmia

Interestingly, compared to healthy controls and acquired anosmia, congenital anosmia shows a larger GM and WM volume in core structures of the olfactory system such as primary olfactory areas (e.g., entorhinal cortex, piriform cortex) (Frasnelli et al. 2013; Karstensen et al. 2018), secondary olfactory areas such as OFC, ACC and insular cortex (Peter et al. 2020; Karstensen et al. 2018; Frasnelli et al. 2013) and other olfactory-related areas such as the cerebellum, MFG, medial orbital gyrus and superior longitudinal fasciculus. Although there are discrepancies in the lateralisation of the reported findings, these observations certainly deserve further investigation.

Changes in cortical thickness due to lack of sensory processing are not yet fully understood. Previous studies of congenital sensory dysfunction in visual and auditory systems also observed a similar trend (Bridge et al. 2009; Hasson et al. 2016; Park et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2009a, b). The studies found that people with acquired blindness exhibit lower cortical thickness in visual brain areas (Park et al. 2009; Voss and Zatorre 2012). On the contrary, patients with congenital blindness show larger cortical thickness in the occipital cortex (Voss and Zatorre 2012; Qin et al. 2013; Park et al. 2009; Jiang et al. 2009a, b) as well as decreased GM density in the visual cortex (Bridge et al. 2009). In the auditory system, Hyde et al. (2007) observed that patients with congenital tone-deafness had larger cortical thickness and density (Albouy et al. 2013) of the right auditory cortex. A previous report suggests that sensory dysfunction or loss at very early developmental stages (congenital) is correlated with an increase of cortical thickness in some of the core structures, with a mechanism that is fundamentally different from the alteration in acquired loss (Coppola 2012; Frasnelli et al. 2013). A probable explanation relates to the complete lack of sensory input to a cortical area. The study further suggests that the most probable justification of this observation can be explained with brain development (Frasnelli et al. 2013), and it is well known that the pruning of axons and synapses during development is experience-dependent and are more sensitive early in life (Coppola 2012; Tierney and Nelson 2009). The best-studied and understood sensory processing is vision. The main areas involved in visual processing are V1, primary, calcarine, or striate cortex (Lee et al. 2012; Wandell and Wade 2003). These areas show a rapid increase in brain volume during fetal life and early childhood and decrease rapidly in later years (Huttenlocher et al. 1982). The number of neurons remains relatively stable throughout the development. However, there are changes in the number of synaptic connections, which undergo rapid growth in early life and are reduced over time. This synaptic connection closely reflects brain volume (Huttenlocher and Dabholkar 1997). Furthermore, afferent input in early life is crucial for forming functional connections (Huttenlocher et al. 1982). Synaptic pruning or developmental excitement (Innocenti and Price 2005) was proposed to increase cortical thickness in patients with congenital blindness. This is due to synaptic overgrowth, which is interrupted in missing afferent input (Park et al. 2009). Therefore, similar mechanisms may apply to the olfactory system, where missing olfactory input (with no OB or small OB) fails to induce synaptic pruning in the primary and secondary olfactory cortices piriform and the orbitofrontal cortices, as well as in other neighbouring brain regions.

On the other hand, Hasson et al. (2016) suggested that patients with congenital blindness had a different genetic organisation that may alter the brain structural network. In contrast, it has also been suggested that the larger GM and WM volumes could also indicate an increase in connectivity (Kolb and Gibb 2011).

Limitations in the literature

The heterogeneity of the findings was high due to the differences in many factors. The results show morphological variations, particularly in GM and WM atrophy. For example, both congenital and acquired anosmia studies reported inconsistency in brain areas and laterality. Even though some of the studies reported similar aetiology, their findings were at times contradictory. Six studies reported congenital anosmia; however, only three studies reported larger volumes of GM and WM compared to healthy controls in a few areas related to olfactory processing. Most importantly, the areas involved and the laterality of the involved areas were varied from one study to another. Furthermore, most of the existing studies also have a very small sample size, and future research requires further investigation in a larger sample.

Future directions for research in this area

We would like to suggest more comprehensive research in the future for both congenital and acquired olfactory loss. This includes more regions being considered, more comprehensive measures of anosmia, and the usage of MRI methods like DTI. In the current study, we proposed that the neural mechanism of brain alterations is different between aetiology, but the underlying details of these differences are unclear. More importantly, congenital anosmia shows larger GM and WM volume than HC, which is not found in acquired anosmia. This finding is fascinating, but the current data show discrepancies in terms of areas involved and brain laterality.

Conclusion

The present review suggests that MRI evaluations of OB volume could objectively diagnose olfactory dysfunction in patients with subjective olfactory loss. However, because the correlation between OS depth and olfactory dysfunction is not apparent and contradictory, a combined OB volume and OS depth evaluation is suggested. We also observed the right dominance of OB volume and OS depth, which is in line with the idea that the right hemisphere is relatively more important for olfactory processing than the left hemisphere. The present review also observed both primary and secondary olfactory areas show GM and WM alterations and conclude that brain alteration is more pronounced with longer disease duration. Finally, congenital anosmia shows larger GM and WM volumes in a few regions in primary and secondary olfactory areas. This is opposite to the presence of smaller GM and WM volumes in patients with acquired olfactory loss. The present study suggests that the difference in the volume and thickness of GM and WM between congenital and acquired anosmia is due to different mechanisms responsible for the olfactory dysfunction. We further suggest that the mechanisms underlying congenital anosmia differ from those involved in acquired loss. The mechanism behind these structural and neural changes are likely to be multifactorial. This result motivates further neuroimaging research into the pathophysiology of lifelong olfactory dysfunction.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Abbreviations

- URTI

Infections of the upper respiratory tract

- SND

Sinonasal disease

- TBI

Traumatic brain injury

- OB

Olfactory bulb

- OS

Olfactory sulcus

- GM

Grey matter

- WM

White matter

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- fMRI

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

- DTI

Diffusor tensor imaging

- EEG

Electroencephalography

- MEG

Magnetoencephalography

- VBM

Voxel-based morphometry

- TDI score

Threshold-Discrimination-Identification score

- OFC

Orbital frontal cortex

- SFS

Superior frontal sulcus

- MFG

Middle frontal gyrus

- MPC

Medial prefrontal cortex

- DLPFC

Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

- ACC

Anterior cingulate cortex

- MTG

Middle temporal gyrus

- STG

Superior temporal gyrus

- SMG

Supramarginal gyrus

- SFG

Superior frontal gyrus

- MOG

Middle occipital gyrus

- MCC

Middle cingulate cortex

- ACC

Anterior cingulate cortex

- ITG

Inferior temporal gyrus

- SFS

Superior frontal sulcus

- MPC

Medial prefrontal cortex

- SCG

Subcallosal gyrus

- NAc

Nucleus accumbens

- SOG

Superior occipital gyrus

- IC

Anterior insular cortex

- SMG

Supramarginal gyrus

Author contributions

Original idea: TH. Articles search and selection: HAM and NY. Conceptualisation, writing the original draft: HAM. Review and editing: HAM, NY, PH and TH.

Funding

This work was supported by the Geran Galakan Penyelidik Muda (Incentive Grant for Young Researchers) Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (UKM) GGPM-2017-016, Dana Fundamental Pusat Perubatan Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (PPUKM) (PPUKM Fundamental Fund) FF-2020-013 and Publication Incentive Fund GP-2020-K021856.

Availability of data and material (data transparency)

Not applicable.

Code availability (software application or custom code)

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not need informed consent by any of the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abolmaali ND, Kühnau D, Knecht M, Köhler K, Hüttenbrink KB, Hummel T. Imaging of the human vomeronasal duct. Chem Senses. 2001 doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abolmaali ND, Volker H, Thomas JV, Karl BH, Thomas H. MR evaluation in patients with isolated anosmia since birth or early childhood. Am J Neuroradiol. 2002;23:157–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albouy P, Mattout J, Bouet R, Maby E, Sanchez G, Aguera PE, Daligault S, et al. Impaired pitch perception and memory in congenital amusia: the deficit starts in the auditory cortex. Brain. 2013 doi: 10.1093/brain/awt082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold TC, You Y, Ding M, Zuo X-N, de Araujo I, Li W. Functional connectome analyses reveal the human olfactory network organization. Eneuro. 2020 doi: 10.1523/eneuro.0551-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barresi M, Ciurleo R, Giacoppo S, Cuzzola VF, Celi D, Bramanti P, Marino S. Evaluation of olfactory dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. J Neurol Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson S, Berglund H, Gulyas B, Cohen E, Savic I. Brain activation during odor perception in males and females. NeuroReport. 2001 doi: 10.1097/00001756-200107030-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter T, Brüderle J, Gudziol H, Burmeister HP, Gaser C, Guntinas-Lichius O. Gray and white matter reduction in hyposmic subjects—a voxel-based morphometry study. Brain Res. 2010;1347(August):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitter T, Gudziol H, Burmeister HP, Mentzel HJ, Guntinas-Lichius O, Gaser C. Anosmia leads to a loss of gray matter in cortical brain areas. Chem Senses. 2010 doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boesveldt S, Postma EM, Boak D, Welge-Luessen A, Schöpf V, Mainland JD, Martens J, Ngai J, Duffy VB. Anosmia-a clinical review. Chem Senses. 2017 doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjx025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridge H, Cowey A, Ragge N, Watkins K. Imaging studies in congenital anophthalmia reveal preservation of brain architecture in 'visual' cortex. Brain. 2009 doi: 10.1093/brain/awp279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschhüter D, Smitka M, Puschmann S, Gerber JC, Witt M, Abolmaali ND, Hummel T. Correlation between olfactory bulb volume and olfactory function. Neuroimage. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmichael ST, Clugnet M-C, Price JL. Central olfactory connections in the macaque monkey. J Comp Neurol. 1994;346(3):403–434. doi: 10.1002/cne.903460306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung MS, Choi WR, Jeong HY, Lee JH, Kim JH. MR imaging-based evaluations of olfactory bulb atrophy in patients with olfactory dysfunction. Am J Neuroradiol. 2018 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola DM. Studies of olfactory system neural plasticity: the contribution of the unilateral naris occlusion technique. Neural Plast. 2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/351752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy I, Nordin S, Hummel T. Olfactory disorders and quality of life-an updated review. Chem Senses. 2014 doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjt072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çullu N, Yeniçeri İÖ, Güney B, Özdemir MY, Koşar İ. Evaluation of olfactory bulbus volume and olfactory sulcus depth by 3 T MR. Surg Radiol Anat. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s00276-020-02484-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delon-Martin C, Plailly J, Fonlupt P, Veyrac A, Royet JP. Perfumers' expertise induces structural reorganisation in olfactory brain regions. Neuroimage. 2013;68(March):55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Shaman P, Kimmelman CP, Dann MS. University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test: a rapid quantitative olfactory function test for the clinic. Laryngoscope. 1984 doi: 10.1288/00005537-198402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doty RL, Yousem DM, Pham LT, Kreshah AA, Gechle R, William Lee V. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with head trauma. Arch Neurol. 1997 doi: 10.1001/archneur.1997.00550210061014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. ‘Mini-Mental State’. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonteyn S, et al. Non-sinonasal-related olfactory dysfunction: a cohort of 496 patients. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasnelli J, Hummel T. Olfactory dysfunction and daily life. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2005 doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0796-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasnelli J, Fark T, Lehmann J, Gerber J, Hummel T. Brain structure is changed in congenital anosmia. Neuroimage. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.07.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujii M, Fukazawa K, Takayasu S, Sakagami M. Olfactory dysfunction in patients with head trauma. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2002 doi: 10.1016/S0385-8146(01)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner AJ, Shih SL, Adamov EV, Zafonte RD. Research frontiers in traumatic brain injury: defining the injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2016.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goektas O, Fleiner F, Sedlmaier B, Bauknecht C. Correlation of olfactory dysfunction of different etiologies in mri and comparison with subjective and objective olfactometry. Eur J Radiol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA. Central mechanisms of odour object perception. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nrn2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried JA, Zelano C. The value of identity: olfactory notes on orbitofrontal cortex function. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudziol V, Paech I, Hummel T. Unilateral reduced sense of smell is an early indicator for global olfactory loss. J Neurol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00415-009-5445-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P, Winkler N, Hummel C, Hähner A, Gerber J, Hummel T. Alterations of brain gray matter density and olfactory bulb volume in patients with olfactory loss after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2018 doi: 10.1089/neu.2017.5393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han P, Zang Y, Akshita J, Hummel T. Magnetic resonance imaging of human olfactory dysfunction. Brain Topogr. 2019;32(6):987–997. doi: 10.1007/s10548-019-00729-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasson U, Andric M, Atilgan H, Collignon O. Congenital blindness is associated with large-scale reorganisation of anatomical networks. Neuroimage. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huart C, Meusel T, Gerber J, Duprez T, Rombaux P, Hummel T. The depth of the olfactory sulcus is an indicator of congenital anosmia. Am J Neuroradiol. 2011 doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A2632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Damm M, Vent J, Schmidt M, Theissen P, Larsson M, Klussmann JP. Depth of olfactory sulcus and olfactory function. Brain Res. 2003 doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)02589-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Doty RL, Yousem DM. Functional MRI of intranasal chemosensory trigeminal activation. Chem Senses. 2005 doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Urbig A, Huart C, Duprez T, Rombaux P. Volume of olfactory bulb and depth of olfactory sulcus in 378 consecutive patients with olfactory loss. J Neurol. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00415-015-7691-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hummel T, Whitcroft KL, Andrews P, Altundag A, Cinghi C, Costanzo RM, Damm M, et al. Position paper on olfactory dysfunction. Rhinology. 2017 doi: 10.4193/Rhino16.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, Dabholkar AS. Regional differences in synaptogenesis in human cerebral cortex. J Comp Neurol. 1997 doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19971020)387:2<167::AID-CNE1>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenlocher PR, de Courten C, Garey LJ, Van der Loos H. Synaptogenesis in human visual cortex - evidence for synapse elimination during normal development. Neurosci Lett. 1982 doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(82)90379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde KL, Lerch JP, Zatorre RJ, Griffiths TD, Evans AC, Peretz I. Cortical thickness in congenital amusia: when less is better than more. J Neurosci. 2007 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3039-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Illig KR. Projections from orbitofrontal cortex to anterior piriform cortex in the rat suggest a role in olfactory information processing. J Compar Neurol. 2005;488(2):224–231. doi: 10.1002/cne.20595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innocenti GM, Price DJ. Exuberance in the development of cortical networks. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005 doi: 10.1038/nrn1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang J, Zhu W, Shi F, Liu Y, Li J, Qin W, Li K, Chunshui Yu, Jiang T. Thick visual cortex in the early blind. J Neurosci. 2009 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5451-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]