Abstract

Cytokines activate inflammatory signals and are major mediators in progressive β-cell damage, which leads to type 1 diabetes mellitus. We recently showed that the cell-permeable Tat-CIAPIN1 fusion protein inhibits neuronal cell death induced by oxidative stress. However, how the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein affects cytokine-induced β-cell damage has not been investigated yet. Thus, we assessed whether the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein can protect RINm5F β-cells against cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. In cytokine-exposed RINm5F β-cells, the transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein elevated cell survivals and reduced reactive oxygen species (ROS) and DNA fragmentation levels. The Tat-CIAPIN1 protein reduced mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and NF-κB activation levels and elevated Bcl-2 protein, whereas Bax and cleaved Caspase-3 proteins were decreased by this fusion protein. Thus, the protection of RINm5F β-cells by the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein against cytokine-induced cytotoxicity can suggest that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein might be used as a therapeutic inhibitor against RINm5F β-cell damage.

Keywords: Cytokines, Diabetes, MAPK, NF-κB, Protein therapy, Tat-CIAPIN1

INTRODUCTION

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), a chronic autoimmune disease, occurs primarily in childhood and is characterized by hyperglycemia that destroys pancreatic β-cells. T1DM is increasing and affecting millions of people worldwide. It is well known that environmental and genetic factors affect the development of T1DM (1-5). In the early stages of T1DM, the infiltration of inflammatory cells promotes the release of cytokines, such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (INF-γ), and promotes cytotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells, which may contribute to the impairment of insulin secretion and lead to β-cell death (6-8). Thus, inhibition of β-cell damage may ameliorate T1DM progression.

Cytokine-induced apoptosis inhibitor 1 (CIAPIN1; originally named anamorsin) is an identified apoptosis-associated protein. Several studies have reported that CIAPIN1 is an anti-apoptotic molecule that has no homology with the anti-apoptotic proteins, such as Bcl-2, caspase, the IAP families, or other signal-transduction molecules; CIAPIN1 is known as a regulator of the RAS signaling pathway (9-12). CIAPIN1 is expressed in various tissues, including metabolic tissues, and has a critical role in various cancers, including gastric cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, and renal cancer (12, 13). Several previous studies showed that the CIAPIN1 protein inhibits the proliferation of various cancer cells; so this protein could be a new anticancer agent (13-16). In the brain, overexpression of the CIAPIN1 protein reduced dopaminergic neuronal cell death in rat brains. Other studies have reported that this protein is involved in inflammation, ROS, and intracellular signaling-pathway mediators (17-20).

Protein transduction peptides (PTDs) are generally composed of 4-30 basic amino-acid-rich sequences and are promising tools for the delivery of proteins into cells (21, 22). In general, the large molecule of protein prevents them from being deli-vered to cell membranes and the blood-brain barrier (BBB). However, PTD technology permits intracellular delivery of therapeutic molecules without increasing cytotoxicity (23, 24). The Tat PTD is a natural peptide from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and is commonly used to deliver proteins into cells (25-27). We also have reported that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein reduced cell deaths in oxidative-stress-induced hippocampal neuronal cells and reduced inflammatory responses in LPS-induced Raw 264.7 cells (28, 29). In addition, many reports have shown that transduced PTD fusion proteins inhibit cell deaths in oxidative stress- or cytokine-induced cells (28-35). In this study, we investigated whether the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein can protect RINm5F β-cells against cytokines-induced cytotoxicity.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Transduction of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein into RINm5F β-cells

Much evidence has demonstrated that a transduced fusion protein has been an effective tool for application of therapeutic proteins (28-35). Although the precise mechanism of transduction of Tat fusion proteins has not been well established, this fusion protein seems to be transduced into cells by either direct translocation or endocytosis (36, 37). This protein delivery has been getting the spotlight as an alternative means for gene delivery (38, 39). To investigate the transductive efficiency of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein in RINm5F β-cells, we prepared the cell-permeable Tat-CIAPIN1 protein as described previously (28).

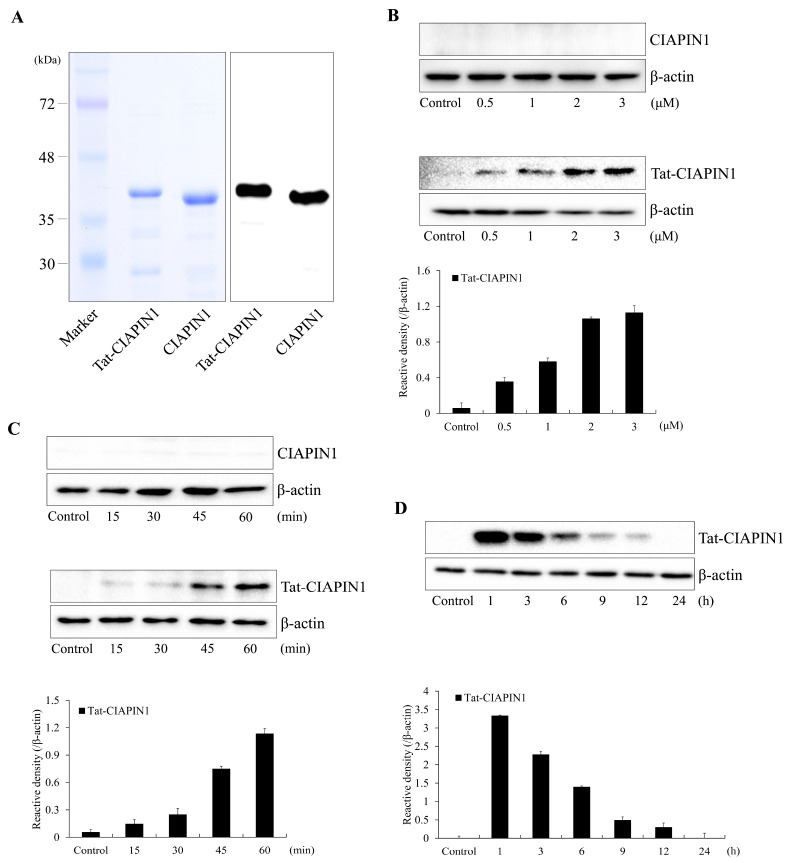

Fig. 1A shows purified Tat-CIAPIN1 and CIAPIN1 proteins. To assess the ability for Tat-CIAPIN1 protein transduction, we treated RINm5F β-cells with Tat-CIAPIN1 proteins (0.5-3 μM) for 1 h or with Tat-CIAPIN1 proteins at 3 μM for 15-60 min. As shown in Fig. 1B and 1C, the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein was transduced into RINm5F β-cells in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. In addition, the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein levels remained stable for 12 h after transduction and subsequently disappeared over time (Fig. 1D). These results indicate that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein was transduced into RINm5F β-cells and was maintained in the cells for at least 12 h. In a previous study, we showed that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein was transduced into HT-22 and Raw 264.7 cells (28, 29).

Fig. 1.

Purification and transduction of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein into RINm5F β-cells. We confirmed purified Tat-CIAPIN1 and CIAPIN1 proteins by 12% SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis (A). Trans-duction of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein into RINm5F β-cells. We added the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (0.5-3 μM) to the culture media for 1 h (B). We then added the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM) to the culture media for 15-60 min (C). We assessed the stability of the transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein after various time periods. The cells were treated with the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM), incubated for 1-24 h, and analyzed by Western blot analysis (D). We repeated all experiments at least three times, and present data as mean ± SEM.

The Tat-CIAPIN1 protein inhibits cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cell damage

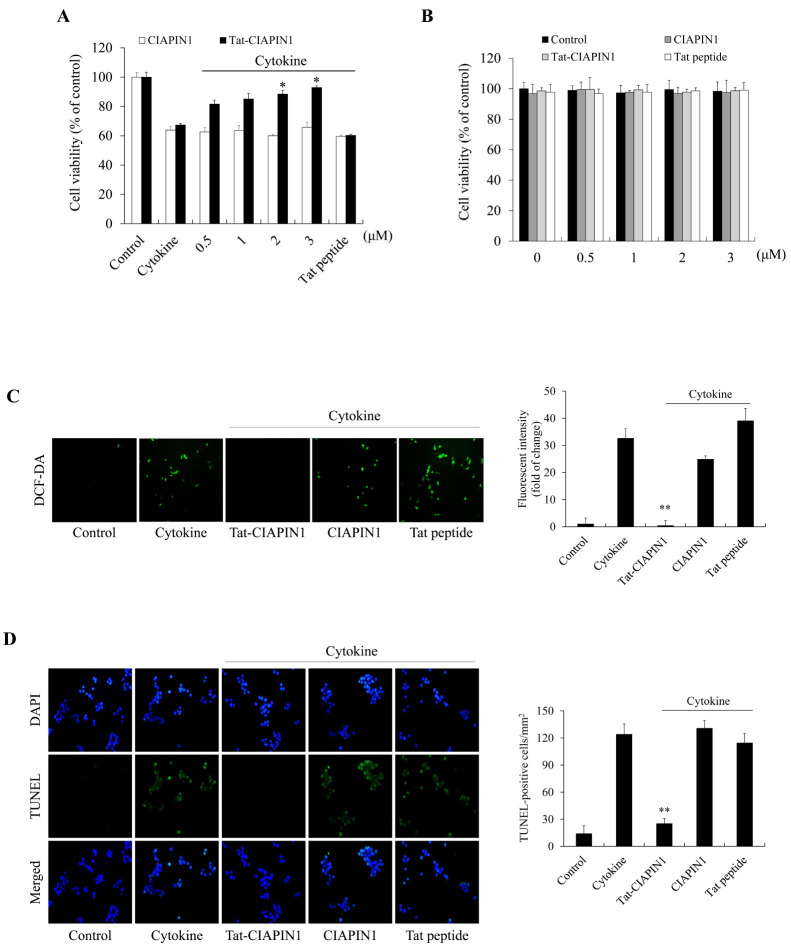

It is well known that cytokines promote cytotoxicity in pancreatic β-cells and lead to β-cell death (6-8). Therefore, we first investigated whether the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein inhibits cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cell deaths. As shown in Fig. 2A, transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein increased cell survival in a concentration-dependent manner against cytokine-induced cell death. Also, we assessed the toxicity of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein by measuring the cell viability. As shown in Fig. 2B, the viability of the cells treated with the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein was consistently maintained.

Fig. 2.

Effects of the transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein on cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cell damage. We pretreated the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (0.5-3 μM or 3 μM) with RINm5F β-cells for 1 h, and then treated it with cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ). Then we assessed cell viability (A and B), ROS production (C), and DNA fragmentation (D) as described in Materials and Methods. *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.001 compared with cytokine-treated cells. We repeated all experiments at least three times, and present data as mean ± SEM.

Next, we investigated whether the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein inhibits ROS production and DNA fragmentation (Fig. 2C, D). In cytokine-exposed RINm5F β-cells, ROS production and DNA fragmentation levels were decreased by the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein. These results indicate that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein can protect against cytokine-induced cytotoxicity. However, the CIAPIN1 protein or Tat peptide alone did not show the protective effects in cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cells.

Since pancreatic β-cells contain significantly fewer antioxidant proteins, including superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxide, than do other tissues in the rat model, several studies have reported that cytokines and oxidative stress are major factors for the destruction of pancreatic β-cells. The anti-oxidant proteins play a beneficial role in pancreatic β-cell viability (40-43).

Effects of Tat-CIAPIN1 against cytokine-induced NF-κB, MAPK, and the apoptosis signaling pathway

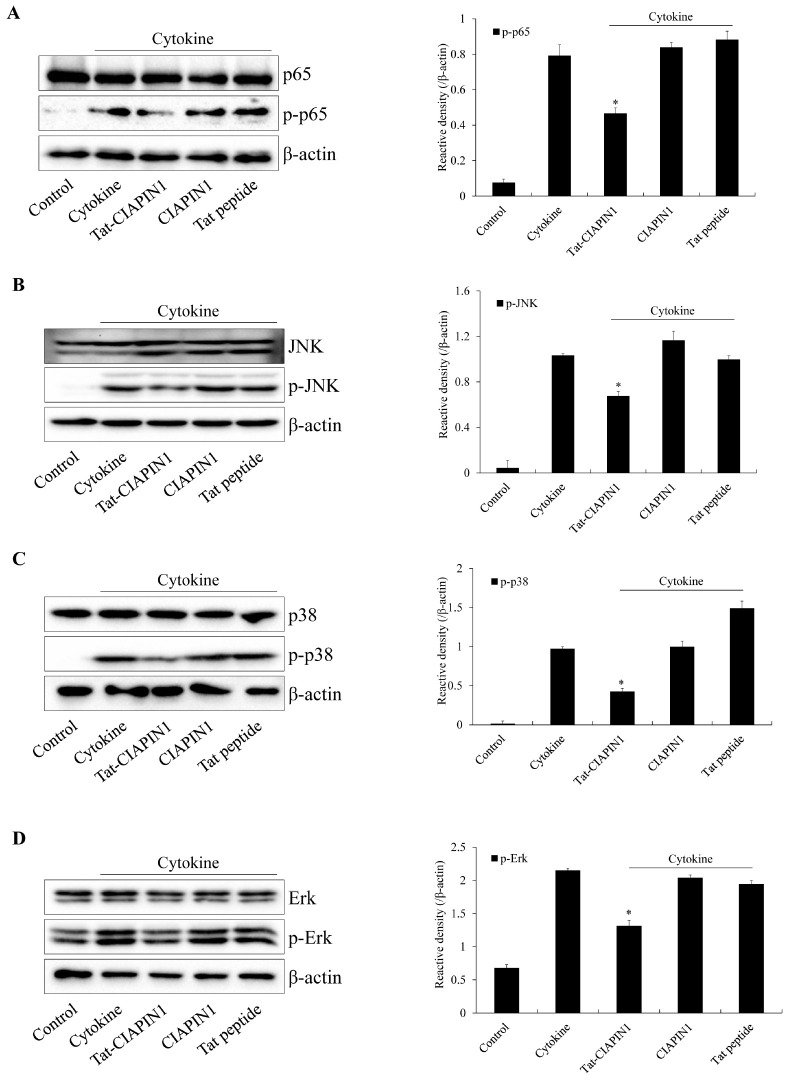

Some studies have shown that NF-κB is a key factor in cytokine-induced pancreatic β-cell damage and have suggested that inhibition of NF-κB may be a novel strategy for delaying the progression of T1DM (44, 45). Sakai et al. (46) have reported that NF-κB and MAPKs are involved in diabetes complications and diabetic nephropathy. Other studies have shown that MAPK and NF-κB activation were increased in streptozotocin-induced rat or INS-1 cells (46-48). In this study, we showed that the levels of NF-κB and MAPK activation were markedly increased in cytokine-exposed RINm5F β-cells by the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein and that this fusion protein reduced NF-κB and MAPK activation levels (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effects of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein on cytokine-induced NF-κB and MAPK activation in RINm5F β-cells. We pretreated the cells with the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM) for 1 h and then treated them with cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ). Then, we assessed the levels of NF-κB (A) and MAPK (B-D) by Western blotting and measured the band intensity by densitometer. *P < 0.01 compared with cytokine-treated cells. We repeated all experiments at least three times, and present data as mean ± SEM.

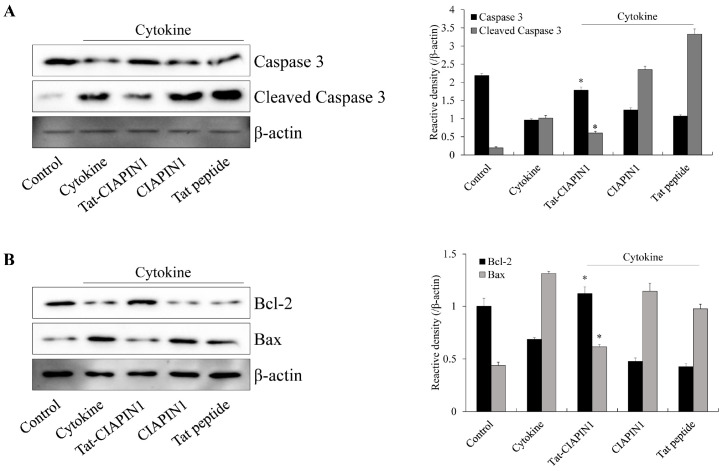

Since it is known that excessive cytokine leads to cell death via the apoptosis signaling pathway and that Bcl-2 and Bax protein expression is associated with apoptosis (47-50), we examined whether the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein regulates apoptotic signaling (Fig. 4). In cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cells, the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein significantly reduced cleaved Caspase-3 and Bax protein expression, whereas Bcl-2 protein expression was significantly increased by this fusion protein. These results indicate that Tat-CIAPIN1 plays a crucial role for cell survival by regulating signaling pathways in cytokine-exposed RINm5F β-cell (Fig. 4). Zhang et al. (51) showed that overexpression of the CIAPIN1 protein significantly increased Bcl-2 protein expression, whereas Bax protein expression was significantly decreased in hypoxia/reoxygenation-damaged H9c2 cells, suggesting that overexpression of the CIAPIN1 protein reduced apoptosis by the changes of expression of apoptosis-associated proteins in hypoxia/reoxygenation injury (51).

Fig. 4.

Effects of the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein on cytokine-induced apoptotic signaling in RINm5F β-cells. We pretreated the cells with the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM) for 1 h and then treated them with cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ). Then, we assessed the indicated protein expression levels (A, B) by Western blotting and measured the band intensity by densitometer. *P < 0.01 compared with cytokine-treated cells. We repeated all experiments at least three times, and present data as mean ± SEM.

In summary, we showed that the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein inhibited pancreatic β-cell death by reducing ROS generation, activating NF-κB and MAPK, and regulating the apoptosis-associated proteins in cytokine-induced RINm5F β-cells. Although the precise function of the CIAPIN1 protein in T1DM remains to be verified, the Tat-CIAPIN1 protein plays a beneficial role in pancreatic β-cells. Therefore, we suggest that Tat-CIAPIN1 may provide a potential therapeutic protein agent for T1DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Tat-CIAPIN1 protein was prepared as described previously study (28). The used antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Bio-technology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). 2‘,7‘-Dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Cytokines (IL-1, TNF-α, and IFN-γ) were obtained from R&D system (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotics (penicillin and streptomycin) were purchased from Gibco (Carlsbad, CA, USA). All other agents were of the highest grade available unless otherwise stated.

Cell culture and Tat-CIAPIN1 protein transduction

Pancreatic β-cells (RINm5F β-cells) were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% FBS and 1% antibiotics.

To assess the ability of Tat-CIAPIN1 protein transduction, RINm5F β-cells were treated with 0.5-3 μM or 15-60 min of Tat-CIAPIN1 protein in culture medium. After washing, transduced levels were determined by Western blotting.

Western blot analysis

Protein concentrations were determined with Bradford assay (52). Equal amount of proteins were loaded onto 12% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The membranes were incubated in 5% milk followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. After washing, the membranes were incubated with Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h. Then, protein bands were visualized using ECL reagents (Amersham, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) (28, 33).

Effect of Tat-CIAPIN1 protein on RINm5F β-cell viability

Cell viability was analyzed using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. After transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (0.5-3 μM) into RINm5F β-cells for 1 h, cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ) were exposed the cells for 12 h. Cell viability was determined as described in previous (28).

Measurement of DNA fragmentation levels

DNA fragmentation was determined using a Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche Applied Science, Basel, Switzerland). After transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM) into RINm5F β-cells for 1 h, cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ) were exposed the cells for 24 h. Then, DNA fragmentation levels were confirmed as described in previous (28, 33).

Measurement of ROS level

Intracellular ROS levels were determined using a DCF-DA staining. After transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 protein (3 μM) into RINm5F β-cells for 1 h, cytokines (5 ng/ml IL-1β, 10 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 ng/ml IFN-γ) were exposed the cells for 22 h and the cells incubated for 30 min with DCF-DA (20 μM). Then, ROS production levels were confirmed as described in previous (28, 33).

Statistical analysis

Data represent the mean of three experiments ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed by ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni’s post-hoc test using GraphPad Prism software (version 5.01; GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). P < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program (2017R1D1A3B04032007 & 2019R1A6A1A11036849) through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Welters A, Lammert E. Diabetes Mellitus. In: Lammert E, Zeeb M, editors. Metabolism of human diseases: organ physiology and pathophysiology. Springer; Vienna: 2014. pp. 163–173. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katsarou A, Gudbjornsdottir S, Rawshani A, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17016. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lukic ML, Pejnovic N, Lukic A. New insight into early events in type 1 diabetes: role for islet stem cell exosomes. Diabetes. 2014;63:835–837. doi: 10.2337/db13-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson CC, Gyurus E, Rosenbauer J, et al. Trends in childhood type 1 diabetes incidence in Europe during 1989-2008: evidence of non-uniformity over time in rates of increase. Diabetologia. 2012;55:2142–2147. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Patterson CC, Dahlquist GG, Gyurus E, Green A, Soltesz G. EURODIAB Study Group: incidence trends for childhood type 1 diabetes in Europe during 1989-2003 and predicted new cases 2005-20: a multicentre prospective registration study. Lancet. 2009;373:2027–2033. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60568-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Imai Y, Dobrian AD, Weaver JR, et al. Interaction between cytokines and inflammatory cells in islet dysfunction, insulin resistance and vascular disease. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:S117–S129. doi: 10.1111/dom.12161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cnop M, Welsh N, Jonas JC, Jorns A, Lenzen S, Eizirik DL. Mechanisms of pancreatic beta cell death in type 1 and type 2 diabetes: many differences, few similarities. Diabetes. 2005;54:S97–S107. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.suppl_2.S97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Corbett JA, McDaniel ML. Does nitric oxide mediate autoimmune destruction of beta-cells? Possible therapeutic interventions in IDDM. Diabetes. 1992;41:897–903. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.8.897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shibayama H, Takai E, Matsumura I, et al. Identification of a cytokine-induced antiapoptotic molecule anamorsin essential for definitive hematopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:581–592. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao Z, Li X, Qiao T, du R, Zhang G, Fan D. Subcellular localization of CIAPIN1. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1437–1444. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6960.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y, Fang J, Ma H. Inhibition of miR-182-5p protects cardiomyocytes from hypoxia-induced apoptosis by targeting CIAPIN1. Biochem Cell Biol. 2018;96:646–654. doi: 10.1139/bcb-2017-0224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Z, Su GF, Hu WJ, Bi XX, Zhang L, Wan G. The study on expression of CIAPIN1 interfering hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and its mechanisms. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2017;21:3054–3060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao Z, Li X, Qiao T, Du R, Hong L, Fan D. CIAPIN1 confers multidrug resistance by upregulating the expression of MDR-1 and MRP-1 in gastric cancer cells. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:261–266. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.3.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li X, Wu K, Fan D. CIAPIN1 as a therapeutic target in cancer. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:603–610. doi: 10.1517/14728221003774127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li X, Fan R, Zou X, et al. Reversal of multidrug resistance of gastric cancer cells by downregulation of CIAPIN1 with CIAPIN1 siRNA. Mol Biol. 2008;42:102–109. doi: 10.1134/S0026893308010135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang X, Pan J, Li J. Cytokine-induced apoptosis inhibitor 1 inhibits the growth and proliferation of multiple myeloma. Mol Med Res. 2015;12:2056–2062. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park KA, Yun N, Shin DI, et al. Nuclear translocation of anamorsin during drug-induced dopaminergic neurodegeneration in culture and in rat brain. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:433–444. doi: 10.1007/s00702-010-0490-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sethi G, Shanmugam MK, Ramachandran L, Kumar AP, Tergaonkar V. Multifaceted link between cancer and inflammation. Biosci Rep. 2012;32:1–15. doi: 10.1042/BSR20100136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sethi G, Tergaonkar V. Potential pharmacological control of the NF-kappaB pathway. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2009;30:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemmon MA, Schlessinger J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell. 2010;141:1117–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gump JM, Dowdy SF. TAT transduction: the molecular mechanism and therapeutic prospects. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:443–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon JI, Han MJ, Yu SH, et al. Enhanced delivery of protein fused to cell penetrating peptides to mammalian cells. BMB Rep. 2019;52:324–329. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.5.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cellular uptake of the tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus. Cell. 1988;55:1189–1193. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kardani K, Milani A, Shabani SH, Bolhassani A. Cell penetrating peptides: the potent multi-cargo intracell-ular carriers. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2019;16:1227–1258. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2019.1676720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsay MA. Peptide-mediated cell delivery: application in protein target validation. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:587–594. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4892(02)00199-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. Modulation of cellular function by TAT mediated transduction of full length proteins. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2003;4:97–104. doi: 10.2174/1389203033487289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snyder EL, Dowdy SF. Cell penetrating peptides in drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2004;21:389–393. doi: 10.1023/B:PHAM.0000019289.61978.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yeo HJ, Shin MJ, Yeo EJ, et al. Tat-CIAPIN1 inhibits hippocampal neuronal cell damage through the MAPK and apoptotic signaling pathways. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;135:68–78. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yeo HJ, Shin MJ, You JH, et al. Transduced Tat-CIAPIN1 reduces the inflammatory response on LPS- and TPA-induced damages. BMB Rep. 2019;52:695–699. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2019.52.12.245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van den Berg A, Dowdy SF. Protein trans-duction domain delivery of therapeutic macromolecules. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22:888–893. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dietz GP. Cell-penetrating peptide technology to deliver chaperones and associated factors in diseases and basic research. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2010;11:167–174. doi: 10.2174/138920110790909731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim DW, Shin MJ, Choi YJ, et al. Tat-ATOX1 inhibits inflammatory responses via regulation of MAPK and NF-κB pathways. BMB Rep. 2018;51:654–659. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2018.51.12.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin MJ, Kim DW, Lee YP, et al. Tat-glyoxalase protein inhibits against ischemic neuronal cell damage and ameliorates ischemic injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2013;67:195–210. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.10.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shin MJ, Kim DW, Jo HS, et al. Tat-PRAS40 prevent hippocampal HT-22 cell death and oxidative stress induced animal brain ischemic insults. Free Radic Biol Med. 2016;97:250–262. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cho SB, Eum WS, Shin MJ, et al. Transduced Tat-aldose reductase protects hippocampal neuronal cells against oxidative stress-induced damage. Exp Neurobiol. 2019;28:612–627. doi: 10.5607/en.2019.28.5.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herbig ME, Weller K, Krauss U, Beck-Sickinger AG, Merkle HP, Zerbe O. Membrane surfaceassociated helices promote lipid interactions and cellular uptake of human calcitonin-derived cell penetrating peptides. Biophys J. 2005;89:4056–4066. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.068692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wadia JS, Stan RV, Dowdy SF. Transducible TAT-HA fusogenic peptide enhances escape of TAT-fusion proteins after lipid raft macropinocytosis. Nat Med. 2004;10:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nm996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Sayed A, Futaki S, Harashima H. Delivery of macromolecules using arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides: ways to overcome endosomal entrapment. AAPS J. 2009;11:13–22. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Frankel AD, Bredt DS, Pabo CO. Tat protein from human immunodeficiency virus forms a metal-linked dimer. Science. 1988;240:70–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2832944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lei XG, Vatamaniuk MZ. Two tales of anti-oxidant enzymes on cells and diabetes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:489–503. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lenzen S, Drinkgern J, Tiedge M. Low anti-oxidant enzyme gene expression in pancreatic islets compared with various other mouse tissues. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:463–466. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)02051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lundh M, Scully SS, Mandrup-Poulsen T, Wagner BK. Small-molecule inhibition of inflammatory beta cell death. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:176–184. doi: 10.1111/dom.12158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rabinovitch A, Suarez-Pinzon WL. Cytokines and their roles in pancreatic islet beta-cell destruction and insulindependent diabetes mellitus. Biochem Pharmacol. 1998;55:1139–1149. doi: 10.1016/S0006-2952(97)00492-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eldor R, Yeffet A, Baum K, et al. Conditional and specific NF-kappaB blockade protects pancreatic beta cells from diabetogenic agents. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5072–5077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508166103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Grey ST, Longo C, Shukri T, et al. Genetic engineering of a suboptimal islet graft with A20 preserves beta cell mass and function. J Immunol. 2003;170:6250–6256. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.12.6250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sakai N, Wada T, Furuichi K, et al. p38 MAPK phosphorylation and NF-kappa B activation in human crescentic glomerulonephritis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:998–1004. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.6.998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Wan X, Shao N, Ye R, Zhang N, Zhang Y. Protective and anti-angiopathy effects of ginsenoside Re against diabetes mellitus via the activation of p38MAPK, ERK1/2 and JNK signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2016;14:4849–4856. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.5821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y, Mei H, Shan W, et al. Lentinan protects pancreatic cells from STZ-induced damage. J Cell Mol Med. 2016;20:1803–1812. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Riedl SJ, Shi Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:897–907. doi: 10.1038/nrm1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reed JC. Proapoptotic multidomain Bcl-2/Bax-family protein: mechanisms, physiological roles, and therapeutic opportunities. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1378–1386. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang HJ, Zhang YN, Teng ZY. Downregulation of miR-16 protects H9c2(2-1) cells against hypoxia/reoxygenation damage by targeting CIAPIN1 and regulation of NF-κB pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2019;20:3113–3122. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2019.10568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]