Abstract

Translating ribosomes accompany co-translational regulation of nascent polypeptide chains, including subcellular targeting, protein folding, and covalent modifications. Ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) is a co-translational surveillance mechanism triggered by ribosomal collisions, an indication of atypical translation. The ribosome-associated E3 ligase ZNF598 ubiquitinates small subunit proteins at the stalled ribosomes. A series of RQC factors are then recruited to dissociate and triage aberrant translation intermediates. Regulatory ribosomal stalling may occur on endogenous transcripts for quality gene expression, whereas ribosomal collisions are more globally induced by ribotoxic stressors such as translation inhibitors, ribotoxins, and UV radiation. The latter are sensed by ribosome-associated kinases GCN2 and ZAKα, activating integrated stress response (ISR) and ribotoxic stress response (RSR), respectively. Hierarchical crosstalks among RQC, ISR, and RSR pathways are readily detectable since the collided ribosome is their common substrate for activation. Given the strong implications of RQC factors in neuronal physiology and neurological disorders, the interplay between RQC and ribosome-associated stress signaling may sustain proteostasis, adaptively determine cell fate, and contribute to neural pathogenesis. The elucidation of underlying molecular principles in relevant human diseases should thus provide unexplored therapeutic opportunities.

Keywords: Integrated stress response, Neuronal physiology, Proteostasis, Ribosome-associated quality control, Ribotoxic stress response

INTRODUCTION

Ribosomes are macromolecular machinery that decodes the genetic information embedded in nucleotide sequences of messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and translates it into polymers of amino acids. This genetic decoding is not a one-dimensional amplification process since three-dimensional structures of the gene products dictate specific biological functions. Accordingly, translation kinetics, messenger ribonucleoprotein remodeling, and co-translational regulations of nascent polypeptide chains are all coordinated at the translating ribosome level to achieve quality gene expression as needed (1, 2). Translating ribosomes also serve as an essential medium for quality control pathways and proteostasis as erroneous gene products are generated by genetic mutations or inaccurate processing during gene expression. The mRNA surveillance pathways sense different types of faulty mRNAs during translation and promote their degradation via nonsense-mediated decay, nonstop decay (NSD), or no-go decay (NGD) mechanisms (3, 4). The ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) pathway recognizes non-functional ribosome stalling and collisions on mRNAs as faulty translational events (5-8). Sequential action of several RQC factors leads to the dissociation of stalled ribosomes for recycling while targeting aberrant translation intermediates for degradation. Moreover, ribotoxic stressors, like translation inhibitors, ribotoxins, or UV radiation, induce global ribosome collisions that activate ribosome-associated kinases for specific stress signaling events (9-11). Translating ribosomes and their biochemical states thus serve as an integrating hub for quality gene expression and cellular homeostasis. Here, we discuss recent findings on molecular mechanisms of RQC and ribosome-associated stress sig-naling in mammalian models and their implications in a range of physiology from cell-fate decisions to neurological disorders.

SENSING AND SPLITTING OF STALLED RIBOSOMES DURING ABERRANT TRANSLATION

Ribosomal stalling occurs when translating ribosomes encounter molecular lesions in their mRNA substrates. These include 1) specific codon sequences and their translation intermediates (e.g., polylysine chains translated from polyadenylated residues on mRNA), 2) secondary RNA structures, 3) RNA truncation (e.g., endonucleolytic intermediates in RNA-decaying processes or premature polyadenylation), 4) RNA damage (e.g., chemical modifications, UV radiation), and 5) aminoacyl-tRNA deficiency (5, 12, 13). In addition, translation inhibitors induce ribosomal stalling globally, depending on their dosage and mode of translation repression (14-19). Cells have evolved distinct mechanisms that sense and “rescue” the stalled ribosomes for recycling while selectively triaging aberrant mRNAs and translation intermediates.

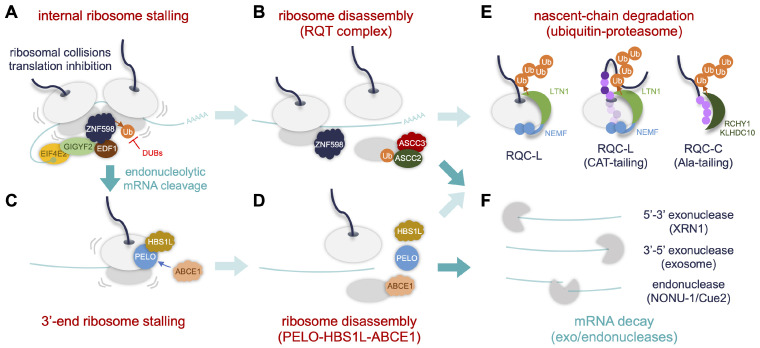

The RING E3 ubiquitin ligase zinc finger 598 (ZNF598) is central to the RQC pathway (Fig. 1A) (20, 21). Ribosomal stalling on an mRNA molecule leads to collisions of the two consecutive translation machineries. ZNF598 binds to the 40S-40S interface of collided ribosomes and mediates the ubiquitination of specific small ribosomal subunit proteins in the disomal context (i.e., RPS3, RPS10, RPS20) (16, 17, 20-22). The ZNF598-dependent stalling mark in the 40S ribosomal subunit is recognized by the RQC-trigger (RQT) complex that subsequently facilitates ribosomal splitting (Fig. 1B). The RQT complex includes two components of the activating signal cointegrator complex (ASCC), ASCC2 and ASCC3, necessary for RQC function (23-25). The ATPase activity of helicase ASCC3 is important for dissociating stalled ribosomes in a ZNF598-dependent manner, whereas it remains to be clarified if the RQC activity re-quires ASCC2 binding to the ubiquitinated ribosomal proteins (23, 24). Other ASCC-associating factors such as thyroid hormone receptor interactor 4 (also known as ASC-1) and ASCC1 are likely dispensable for RQC-relevant ASCC function. Stop-codon readthrough or endonucleolytic RNA cleavage at the stalled ribosomes could further lead to ribosomal stalling at the 3’-end of mRNA molecules (Fig. 1C, F) (6, 26, 27). The 3’-end stalling may not necessarily accompany ribosomal collisions; however, it requires a complex of pelota mRNA surveillance and ribosome rescue factor (PELO) and HBS1 like translational GTPase (HBS1L) that subsequently recruits ATP-binding cassette subfamily E member 1 (ABCE1) for the ribosomal disassembly and RQC function (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

An overview of the RQC pathway. (A, C) Ribosomal collisions occur when the preceding ribosome stalls during translation. In addition, stop-codon readthrough or endonucleolytic mRNA cleavage at the internally stalled ribosomes leads to 3’-end ribosome stalling. The collided ribosomes are detected by ribosome-associated collision sensors (e.g., ZNF598, EDF1). The cap-binding translation repressor complex of EIF4E2 and GIGYF2 is then recruited to the stalled ribosomes, blocking additional ribosome loading. (B, D) The RQT complex consisting of ASCC2 and ASCC3 likely senses ZNF598-dependent ubiquitination of specific ribosomal proteins (e.g., RPS10) at internally stalled ribosomes and triggers their disassembly. On the other hand, the PELO-HBS1L complex senses 3’-end ribosome stalling and recruits ABCE1 for the ribosome disassembly. (E) Nascent polypeptide chains associating with the 60S subunit undergo ubiquitindependent proteasomal degradation via three distinct pathways: 1) LTN1-dependent ubiquitination of the nascent chain for degradation (RQC-L); 2) NEMF-dependent C-terminal alanine/threonine (CAT)-tailing of the nascent chain, followed by RQC-L; and 3) NEMF-dependent alanine-tailing of the nascent chain, followed by the C-end rule pathway for protein degradation (RQC-C). Light and dark purple circles depict alanine and threonine residues, respectively, added to C-terminus of the nascent chain by NEMF activity. (F) The mRNAs are also degraded by exo- and endonucleases.

In fact, the ubiquitination of small ribosomal subunit proteins (RPSs) occurs hierarchically upon genetic or physiological per-turbations. For instance, RPS3 or RPS10 ubiquitination precedes that of RPS2 and RPS20 (14, 28). The ubiquitination status of small ribosomal subunits is also balanced by the opposing activities of ribosome-associated E3 ligases (e.g., ZNF598) and deubiquitinases (DUBs) (Fig. 1A). It has been shown that ovarian tumor deubiquitinase 3 and ubiquitin-specific peptidase 21 deubiquitinate RPS10 and RPS20, antagonizing ZNF598 function in the RQC pathway (14). A complex of G3BP stress granule assembly factor and ubiquitin-specific peptidase 10 also deubiquitinates the rate-limiting RPS3 in the dissociated 40S ribosomal subunit, thereby protecting it from lysosomal degradation and promoting 40S recycling (28).

ALTERNATIVE SENSORS FOR RIBOSOMAL STALLING AND CO-TRANSLATIONAL REGULATION

In addition to the E3 ubiquitin ligase activity on stalled ribosomal proteins, ZNF598 associates with a translational repressor complex of GRB10 interacting GYF protein 2 (GIGYF2) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E family member 2 (EIF4E2; also known as 4EHP) to suppress translation initiation or trigger mRNA decay (Fig. 1A) (29-31). This mode of ZNF598 function likely attenuates the translational burden on mRNAs harboring stalled ribosomes while promoting the removal of problematic transcripts. Interestingly, ZNF598-dependent translational repression is sensitive to the type of ribosome stalling (e.g., NSD vs. NGD substrates) and does not require its ubiquitin ligase activity (29), indicating a mechanism independent of ribosomal ubiquitination and disassembly. It has been further shown that stalled ribosomes recruit the GIGYF2-EIF4E2 complex in a ZNF598-independent manner to suppress translation from the stalling mRNAs (see below) (29, 30, 32).

While ZNF598 plays a key role in initiating the RQC pathway, the amount of endogenous ZNF598 protein is likely limit-ing since ZNF598 overexpression phenotypes are readily detected in translational stalling reporters as well as RPS ubiquitination (21, 33). It is thus plausible that cells employ additional sensors to monitor a myriad of ribosomal events for aberrant translation. Makorin Ring Finger Protein 1 (MKRN1) is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that likely acts as a sequence-specific sensor for the RQC substrate. MKRN1 forms a complex with poly(A)-binding protein C1 (PABPC1) and associates with translating polyribosomes (34). It has been proposed that direct binding of the MKRN1-PABPC1 complex to poly(A) tracks may interfere with ribosomal readthrough, preceding ZNF598-dependent RQC activity (34). MKRN1 substrates for ubiquitination include RPS10 and PABPC1. However, MKRN1-dependent ubiquitination sites in RPS10 (K53/K107) are distinct from ZNF598-dependent ones (K138/K139) and their functional hierarchy following ribosome stalling and RQC activation remains to be determined (14, 33-35).

Biochemical approaches have revealed that endothelial differentiation-related factor 1 (EDF1) associates preferably with collided ribosomes and subsequently recruits the GIGYF2-EIF4E2 complex for feedback inhibition of translation initiation (Fig. 1A) (30, 32). EDF1 function is independent of ZNF598, likely acting upstream of ZNF598-dependent ribosomal ubiquitination and disassembly. Given the abundance of EDF1 molecules in the cells, it has been proposed that EDF1 acts as a primary sensor for ribosomal collisions, reducing ribosomal density on the affected mRNA via translation inhibition by the GIGYF2-EIF4E2 complex (30, 32). Persistent ribosomal stalling may increase the probability of EDF1-dependent recruitment of ZNF598 to collided ribosomes, triggering ZNF598-dependent RPS ubiquitination, ribosomal disassembly, and the canonical RQC pathway.

TRIAGING ABERRANT TRANSLATION INTERMEDIATES

Regardless of their nature (e.g., NGD vs. NSD), the disassembly of stalled ribosomes should be followed by the clearance of translation intermediates from the two ribosomal subunits before recycling. In particular, the 60S subunit associates with a nascent polypeptide that carries a peptidyl-tRNA conjugate and further recruits specific enzymatic activities for proteasomal degradation (Fig. 1B, D). The co-translational elimination of the aberrant intermediate minimizes any proteotoxic effects while efficiently recycling the stalled ribosomes (36). Nuclear export mediator factor (NEMF) plays a key role in this process. NEMF has a stronger binding affinity to the dissociated 60S subunit than the 80S ribosome and stabilizes the association of E3 ubiquitin ligase listerin 1 (LTN1) with the ribosome exit channel (Fig. 1E) (37-42). Subsequent ubiquitination of the 60S-associating nascent chain by LTN1 targets it for proteasomal degradation. In fact, the nascent chain release from the 60S subunit requires additional enzymes such as ankyrin repeat and zinc finger peptidyl tRNA hydrolase 1 (ANKZF1) and valosin-containing protein (VCP). ANKZF1 is a mammalian homolog of yeast Vms1 that hydrolyzes the peptidyl-tRNA conjugate (43-45). The ATPase VCP complex (a mammalian homolog of Cdc48 in yeast) further facilitates the extraction of nascent chains from the 60S subunit (39, 46). Together with sensing and splitting of the stalled ribosomes, the series of these molecular events represent a canonical RQC pathway.

Some RQC substrates, however, may lack a lysine residue near the ribosome exit channel upon ribosomal stalling, limiting LTN1-dependent ubiquitination. NEMF displays selective biochemical affinity to tRNA-alanine among other tRNA species and mediates mRNA template-independent addition of alanine residues to the C-terminus of a nascent chain stalled on the 60S subunit (47, 48). The C-terminal modification of RQC substrates designated as C-terminal alanine/threonine (CAT)- or CAT-like tailing is conserved across species, including bacteria and yeast (42, 49-53). This NEMF-dependent process is thought to drive the stalled nascent chain out of the 60S subunit, thereby exposing the internal lysine residues to LTN1-dependent ubiquitination for proteasomal degradation (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, the C-terminal alanine tail in NEMF-dependent RQC substrates associates with other E3 ligases such as ring finger and CHY zinc finger domain containing 1 (RCHY1; also known as PIRH2) and kelch domain containing 10 (KLHDC10), leading to ubiquitindependent proteasomal degradation (Fig. 1E) (47). KLHDC10 acts as an important E3 ligase component that recognizes select C-terminal degrons in the C-end rule pathway for protein stability (54-56). The two RQC pathways (i.e., LTN1-dependent vs. RCHY1/KLHDC10-dependent) downstream of NEMF may thus operate in parallel and act as a fail-safe mechanism for triaging C-terminally modified RQC substrates. Additional factors important for RNA degradation (e.g., Xrn1/5’-3’ exoribonuclease 1, Ski2/the exosome-associating helicase, Cue2/endonuclease) or 40S ribosome recycling (e.g., Tma20, Tma22, Tma64) have been identified in yeast studies (Fig. 1F) (22, 26, 57, 58). Future studies should demonstrate whether mammalian models and their homologous gene products have evolved similar mechanisms at the appropriate steps of RQC pathways.

SUBTYPES OF RQC PATHWAYS: ER-RQC

Translation of non-cytoplasmic proteins (e.g., organellar, secretory, or membrane proteins) intrinsically accompanies ribosomal stalling during their subcellular targeting or co-translational translocation (59, 60). Mammalian cells express a substantial number of mRNAs that are co-translationally translocated into ER (61, 62). Consequently, ribosomal stalling and its downstream RQC occur robustly at the cytoplasm-ER interface, defining ER-RQC that may play an important role in ER physiology. Transcriptome-wide mapping of ribosomal collisions or PELO targets has also revealed an ER stress-responsive transcription factor (i.e., X-box binding protein 1) as an endogenous RQC substrate (63, 64), further linking RQC function to ER stress via the unfolded protein response. Several studies have elucidated the relevance of ER-RQC to the canonical RQC in the cytoplasm or the ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway for the proteasomal clearance of misfolded ER proteins (65-68).

The key RQC factors NEMF and LTN1 associate biochemically with ER in a ribosome-dependent manner, while 60S-associating nascent polypeptides are polyubiquitinated at the ER translocon (69). LTN1, VCP/p97, and the proteasome are responsible for the degradation of ER-RQC substrates. The ER chaperone heat shock protein family A member 5 (also known as BiP/GRP78) and deubiquitinase YOD1 mediate both ER-RQC and ERAD pathways (66). Nonetheless, it remains elusive whe-ther or not the co-translational ER-RQC is indeed linked to the post-translational ERAD pathway (66, 70). A yeast homolog of the ribosome collision sensor ZNF598 has also been shown to titrate the expression of misfolded ER transporter (70) and associate with mRNAs encoding secretory proteins to minimize their defective targeting to mitochondria (71). However, the latter may not occur at the ER translocon.

Interestingly, ribosomal stalling during co-translational translocation at ER leads to the covalent linkage of ubiquitin fold modifier 1 (UFM1) to RPL26 in the 80S or 60S ribosomal subunits (72). The ER-localizing UFM1 ligase mediates this unique post-translational modification of stalling ribosomes that could be reversed by the UFM1-specific peptidase 2. Importantly, RPL26 UFMylation destabilizes the translationally arrested products at the ER translocon and targets them for lysosomal degradation (72). This process is likely independent of the canonical RQC or ERAD pathways that involve proteasomal degradation of aberrant translation intermediates. Accordingly, we speculate that the complexity of the proteome biogenesis at the cytoplasm-ER interface (e.g., polytopic membrane proteins) has co-evolved with distinct mechanisms and relevant factors for protein quality control upon individual ribosome stalling events at the ER translocon.

SUBTYPES OF RQC PATHWAYS: MITO-RQC

Yeast cells produce substantial amounts of aberrant mitochondrial proteins from ribosome stalling even under non-stress conditions. Ribosomal stalling during co-translational translocation of mitochondrial proteins is accompanied by NEMF-dependent CAT tailing. LTN1 ubiquitinates these nascent chains for proteasomal degradation. However, CAT-tailed products can escape the LTN1-dependent pathway, translocate into mitochondria, form protein aggregates, and contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction. Vms1 suppresses NEMF association with 60S ribosomes (73, 74), thereby inhibiting CAT-tailing. The quality-controlling activities of the key RQC factors at mitochondrial translocon thus define mito-RQC (73), possibly overlapping with ER-RQC. Of note, Vms1 also localizes to the ER membrane and is expected to play a similar role in ER-RQC.

Complex-I 30 kDa subunit (C-I30) constitutes the core assembly of human mitochondrial complex-I. C-I30 translation is regulated by PTEN induced kinase 1 (PINK1) and parkin RBR E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase, two gene products relevant to Parkinson’s disease (PD) (75). Mitochondrial damage induces translational stalling of C-I30 mRNA on the mitochondrial outer membrane and recruits NGD-related RQC factors including PELO, ABCE1, and CCR4-NOT transcription complex subunit 4 (CNOT4) to the ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex (76). Depletion of these RQC factors reduces the polyubiquitin levels associated with damaged mitochondria or with the C-I30 containing RNP complex, inhibiting mitophagy. These processes require PINK1 and are likely mediated by CNOT4-dependent polyubiquitination of ABCE1 that subsequently recruits autophagy receptors. On the other hand, the overexpression of PELO, ABCE1, or CNOT4 induces mitophagy in Drosophila mutants of Pink1 and rescues their mitochondrial aggregation and neu-ronal loss. In addition, mitochondrial stress impairs translation termination by the eukaryotic translation termination factor 1 and ABCE1 and extends the C-terminus of C-I30 protein via a NEMF-dependent CAT-tailing-like process (75). This non-templated addition of amino acids to the full-length C-I30 protein is distinct from those added to nascent polypeptides during CAT-tailing. Nonetheless, both C-terminal modifications lead to loss- of-function effects or protein aggregation (49, 53, 77). Consistent with these observations, PD brain samples display low expression of ABCE1 and HBS1L (76), while aged PD patient fibroblasts exhibit more C-terminal extensions and insolubility of mitochondrial proteins (75), implicating mito-RQC in PD pathogenesis.

These observations suggest that RQC may accompany translational activities in various subcellular compartments. It is thus likely that context-specific substrates and trans-acting factors define the RQC subtypes, diversifying their underlying principles and physiological significance. For instance, defective ribosomal products (DRiP) have been proposed as a significant self-peptide source for MHC-I mediated antigen presentation (78, 79). The definition of DRiPs suggests their analogy to aberrant translation intermediates generated by co-translational RQC. LTN1 indeed contributes to shaping the pool of antigens presented with MHC class I (80). LTN1-dependent immune peptides correspond to the middle parts of proteins and over-represent membrane proteins with multiple transmembrane domains, indicating the role of ER- or mito-RQC in this process.

RQC FUNCTION IN NEURONS AND NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS

Emerging evidence supports RQC function in neural physiology and neurological disorders (Table 1). A recessive “lister” mutant phenotype was originally isolated from the forward genetic screen in mice. The corresponding genetic mutation was mapped to a locus encoding the E3 ubiquitin ligase, and the gene was accordingly designated as Ltn1 (81). Lister mutants display age-dependent decline in motor function and motor neuron degeneration. Reactive astrogliosis, dystrophic neuronal processes, vacuolated mitochondria, and hyperphosphorylated tau are also observed in the brainstem and spinal cord of lister mutants (81). In yeast, loss of ltn1 function induces the pathogenic aggregation of CAT-tailed RQC substrates (49). CAT-tailing has been proposed to serve as a mechanism for increasing the amyloid-aggregation propensity of RQC substrates, sequestering the CAT-tailed products for aggrephagy-mediated degradation, and sustaining proteostasis. However, inclusions of CAT-tailed RQC intermediates also sequester chaperone proteins non-functionally, thereby in-ducing proteotoxic stress (49, 53, 77).

Table 1.

Implications of ribosome-associated surveillance factors in neurological disorders

| Gene | Pathway | Relevance to neurological disorders | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| LTN1 | RQC |

|

(48, 81, 97, 98) |

| NEMF | RQC |

|

(82-84) |

| GTPBP2 | RQC |

|

(86, 89-91) |

| GTPBP1 | RQC |

|

(88) |

| ABCE1 | RQC |

|

(75, 76) |

| PELO | RQC |

|

(94) |

| HBS1L | RQC |

|

(92-94) |

| GIGYF2 | RQC |

|

(99-103) |

| MAP3K20/ZAK | RSR |

|

(17, 121) |

CAT-tailed nonstop products are similarly prone to aggregate in mammalian cell cultures, forming nonstop foci (48). NEMF and LTN1 act as positive and negative regulators, respectively, to set a steady-state level of the endogenous RQC intermediates. Moreover, the overexpression of nonstop proteins or alanine-tailed proteins is sufficient to cause caspase-3 dependent apoptosis. LTN1 depletion consistently impairs neurite outgrowth and neuronal survival in mouse primary neuron cultures, and the Ltn1 phenotypes are rescued by NEMF depletion (48). Importantly, NEMF variants associate with a spectrum of central neurological disorders in humans, including intellectual disability, developmental delay, and juvenile neuromuscular disease (82-84). While NEMF is broadly expressed in the human brain, its strong enrichment in the newborn excitatory neurons suggests a role in early neurodevelopment (82, 85). Homozygous Nemf mice carrying CAT-tailing-defective mutations display progressive motor neuron degeneration (84). NEMF depletion in mouse pri-mary neuron cultures also leads to the impairments of axonal outgrowth and synapse development, and these phenotypes are rescued by human NEMF overexpression (82).

Additional evidence for RQC implication in neuronal homeostasis is derived from elegant epistatic analyses of a neurodegenerative mouse model. Genetic mutations in a central nervous system (CNS)-specific arginyl-tRNA gene and the PELO-interacting GTP binding protein 2 (Gtpbp2) together lead to ribosomal stalling and neurodegeneration phenotypes in mice, including short life span and age-dependent locomotor deficits (86). The ribosomal stalling is accompanied by GCN2-mediated phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 subunit α (eIF2α; also known as EIF2S1) and the ISR activation that feeds back to inhibit neurodegeneration in Gtpbp2 mutant mice (87). The CNS-specific tRNA deficiency in Gtpbp1 mutant mice also causes ribosomal stalling, ISR activation, and neurodegeneration, indicating the non-redundant role of these two ribosome-rescue factors (i.e., GTPBP1 and GTPBP2) (88). Not surprisingly, mutant alleles in human GTPBP2 have been shown to associate with Jaberi-Elahi syndrome, and the affected individuals manifest prenatal onset neurological dysfunction with an age-dependent accumulation of brain iron (89-91). Pathogenic HBS1L variants also associate with multiple congenital anomalies, including microcephaly and general developmental delay (92, 93). Although genomic deletion of Hbs1l or Pelo in mice causes embryonic lethality, their conditional deletion consistently leads to abnormal cerebellar development with neurogenesis defects (92, 94).

The direct relevance of ribosomal stalling and RQC function to well-established neurological disorders has been further documented. Altered expression of RQC-relevant factors (e.g., ABCE1 and HBS1L) and C-terminally extended mitochondrial proteins in PD models suggest implications of mito-RQC in PD pathogenesis (75, 76). The same group has also elucidated the role of mito-RQC and CAT-tailing in Drosophila models of C9ORF72-associated amyotrophic lateral sclerosis/frontotempo-ral dementia (95). Mouse neuronal cells expressing mutant huntingtin (mHtt) exhibit a high ratio of polysome to monosome but a low rate of protein synthesis, suggesting ribosomal stalling (96). mHtt indeed interacts with ribosomes and slows down their translocation. Consistently, ribosomal footprinting has revealed a Huntington disease-specific profile toward 5’- or 3’-end as well as single-codon pauses on select mRNAs. On the other hand, ltn1 deletion in yeast enhances the nuclear accumulation of Htt polyglutamine (polyQ) protein via RQC2-mediated CAT-tailing (97, 98). LTN1 thus exhibits a neuropro-tective function against the cytotoxicity of nuclear polyQ protein.

Finally, the RQC-relevant translational repressor GIGYF2 has been linked to neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism spectrum disorder (99, 100) and schizophrenia (101), although its implications for PD remain unclear (102). While homozygous Gigyf2 mutant mice display early post-natal lethality, heterozygous mutants show age-dependent motor dysfunction, adult-onset neurodegeneration, and defective signaling for the insulin-like growth factor (103). The phenotypic screen in zebrafish mutants of human schizophrenia-associated genes also suggests a role of GIGYF2 homolog in forebrain development and behavioral pathogenesis relevant to schizophrenia (101). Taken together, these observations convincingly demonstrate the conserved roles of RQC in neuronal development, homeostasis, and degeneration.

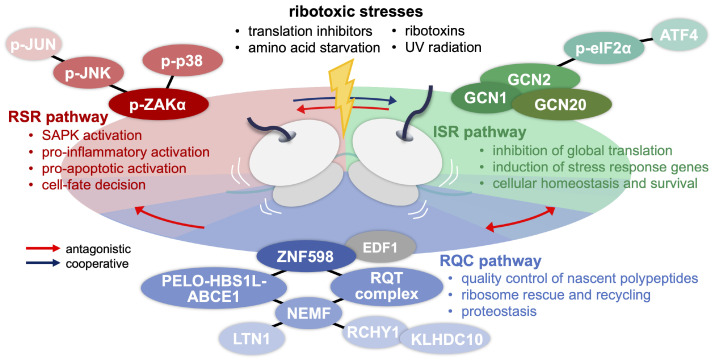

TWO SIGNALING PATHWAYS FROM RIBOSOMAL COLLISIONS: INTEGRATED STRESS RESPONSE (ISR) AND RIBOTOXIC STRESS RESPONSE (RSR)

Ribosomal collisions trigger the RQC pathway via ZNF598-dependent ubiquitination of specific ribosomal proteins. Dissociation of the stalled ribosomes is followed by mechanistic cascades that triage aberrant translation intermediates and rescue the stalled ribosomal subunits for recycling. This cotranslational quality control of individual translation events is essential for sustaining proteostasis. On the other hand, a range of ribotoxic stressors (e.g., translation inhibitors, ribotoxins, UV radiation) induces global ribosome stalling (Fig. 2) (10). Dedicated ribosome-associated factors then initiate cellular stress signaling to regulate the general tone of the translational environment for cellular homeostasis or determine cell fate (e.g., survival vs. apoptosis) (9-11).

Fig. 2.

Ribosomal collisions trigger RQC, ISR, and RSR pathways. Ribotoxic stresses induce ribosomal collisions, and their distinct quality (e.g., scale, kinetics) and molecular signatures (e.g., structural changes in the collided ribosomes) may lead to differential activation of the three ribosomal surveillance pathways. RQC is responsible for the tonic control of ribosomal stalling and the quality expression of nascent chains to sustain proteostasis. ISR shuts down general translation via GCN2-dependent eIF2α phosphorylation upon global ribosome collisions while elevating the homeostatic stress response for cell survival. ZAK-initiated RSR activates SAPKs (i.e., JNK and p38) via the MAPK cascade, stimulating pro-inflammatory and pro-apoptotic pathways for cell-fate decisions. Antagonistic or cooperative crosstalks among the three ribosomal surveillance pathways have been documented and depicted accordingly.

Integrated stress response (ISR) is one of the two signaling pathways that are activated by ribosomal collisions, leading to the phosphorylation of translation initiation factor eIF2α (Fig. 2). The stable complex of the phospho-eIF2α and eIF2B is inhibitory to the formation of the eIF2-GTP/Met-tRNA initiator ternary complex, thereby suppressing global translation initiation (104-106). General amino acid control nondepressible 2 (GCN2; also known as EIF2AK4) is one of the four eIF2α kinases (EIF2AKs) that phosphorylate eIF2α in a stress-specific manner. GCN2 displays homology to histidyl-tRNA synthetase, and both bind deacylated tRNAs, likely leading to GCN2 activation upon amino acid deprivation (107). It has been further shown that direct interaction between GCN2 and the ribosomal P-stalk induces a conformational change in the GCN2 kinase domain, activating the GCN2-dependent ISR pathway (108). Modest inhibition of the ribosomal peptidyl transferase activity by anisomycin leads to eIF2α phosphorylation in a GCN2-dependent manner. However, potent ribosomal stalling by a high concentration of anisomycin does not accompany ISR activation, suggesting the role of ribosomal collisions in the activation process (18). Given that the ribosomal P-stalk is usually occupied by the translation elongation factors eEF1A and eEF2, GCN2 likely acts as a ribosomal collision sensor for the ribosome-derived ISR pathway (108, 109).

Ribotoxic stress response (RSR) is the other signaling pathway that is activated upon ribosomal collisions (Fig. 2). RSR is triggered by the ribosome-associating leucine zipper and sterile-alpha motif kinase ZAK (also known as MAP3K20), a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) family (17, 18, 110, 111). There are two major splicing isoforms, ZAKα and ZAKβ. The flexible C-terminal arm in the longer isoform ZAKα binds to a specific region in the 18S rRNA at ribosomal intersubunit space (17). Consistently, ZAKα but not ZAKβ associates with ribosomes where phosphorylated ZAKα is highly enriched in collided ribosome fractions (18). Ribosomal collisions induced by modest ribotoxic stressors such as anisomycin treatment, amino acid deprivation, or UV exposure lead to ZAKα autophosphorylation and activate the RSR pathway via the MAPK cascade (17, 18). Downstream of the ZAK activation is the phosphorylation and activation of the two stress-activated protein kinases (SAPKs), p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), that are implicated in inflammation and cell-fate decision (10, 112, 113).

HIERARCHICAL CROSSTALK OF THE RIBOSOMAL SURVEILLANCE PATHWAYS

All three ribosome-associated surveillance pathways are triggered by their own molecular sensors for ribosomal collisions (i.e., EDF1 and ZNF598 for RQC; GCN2 for ISR; and ZAK for RSR). Accordingly, their responses to different types and ranges of ribotoxic stresses may vary in sensitivity and kinetics (9). For instance, RQC activation (i.e., ZNF598-dependent RPS10 ubiquitination) is detected only upon modest ribosomal collisions, whereas RSR activation persists over a range of ribosomal collisions (17). Also, the three surveillance pathways share collided ribosomes as the common substrate for activation, raising the possibility of crosstalk in their initiation threshold and downstream signaling (Fig. 2). Mutually antagonistic effects between RQC and ISR pathways have been described in yeast. In fact, the yeast genome encodes a single eIF2α kinase (i.e., GCN2) for ISR activation but not a ZAK homolog for RSR activation (19, 114). A current yeast model proposes that the low frequency of ribosomal collisions may be resolved by RQC activity, thereby elevating the threshold for the collision-activated ISR (19). A high frequency of ribosomal collisions then activates ISR to block general translation initiation via eIF2α phosphorylation, suppress additional ribosome loading on mRNA, and subsequently lower the probability of disome formation for RQC activation.

RQC activation does not require RSR in mammalian cells and vice versa (17). Nevertheless, RSR activation is more potent in ZNF598-deleted cells (18). Similar to the yeast model, it is likely that RQC activity clears any stalled ribosomes and reduces local ribosome density, thereby suppressing the disome formation for ISR or RSR activation. On the other hand, ISR activation is compromised in ZAK-deleted cells (18). It could be explained by the ZAKα-dependent association of the GCN2 activator GCN1 with disomes. These observations indicate that RQC titrates RSR activation, whereas RSR supports ISR activation (Fig. 2). Pharmacological inhibition of the ISR pathway indeed generates more disomes upon amino acid deprivation and potentiates the RSR activation (18), further validating the antagonistic effects of ISR on RSR activation (Fig. 2).

CONCLUDING REMARKS

Transcriptome-wide disome profiling reveals widespread ribosomal collisions on endogenous mRNAs (64, 114-116). The collision loci include specific codon pairs (e.g., proline/aspartic acid/glycine-containing motifs), lysine/arginine-rich polybasic tracts, and stop codons in general, while select mRNA species may display the collision signatures corresponding to ribosomal pausing for co-translational regulation (e.g., organellar or membrane proteins). In addition, transcriptional errors or post-transcriptional mis-processings (e.g., splicing errors, premature polyadenylation) generate substantial amounts of aberrant translation substrates (117). Basal RQC activity may deal with mRNA-specific ribosomal stalling and aberrant translation for proteosta-sis. However, ribotoxic cellular stresses may induce ribosomal collisions more globally, exceeding the capacity of RQC-depen-dent surveillance. The activation of ribosome-associated GCN2 and the ISR pathway may then lower ribosomal density on mRNA and suppress ribosomal collisions by blocking translation initiation while promoting cellular survival via stress-specific translational/transcriptional programs (e.g., cap-independent translation of activating transcription factor 4 and induction of its transcriptional targets) (118-120). Persistent ribosomal collisions may switch the tone of systemic response from ISR-dependent survival to RSR-dependent apoptotic signaling. This hierarchical model for the three ribosomal surveillance pathways is tempting, yet their response kinetics and scales can vary depending on the types of translation inhibitors or ribotoxins (17-19). Future studies should thus define the quality or structural signature of ribosomal collisions that lead to the activation of pathway-specific sensors and determine how ribosome-associating factors and cellular context (e.g., cell type, physiological conditions) tune the output of the three pathways.

Another outstanding question will be the physiological significance of the ribosomal surveillance pathways. As discussed above, evidence for RQC function in neuronal physiology and neurological disorders has exploded since the original description of neurodegenerative phenotypes in Ltn1 mutant mice (81). In addition, mutant alleles of the key RSR factor ZAKα have been associated with abnormal limb development in humans and genome-edited mouse models (17, 121). zak-1 deletion sensitizes Caenorhabditis elegans to anisomycin-induced stress and shortens its lifespan (17). This mutant phenotype is consistent with observations in mammalian cell cultures (18), indicating conservation of the RSR pathway in vertebrate development and homeostatic recovery from ribosomal stress. The RSR-relevant SAPKs and ISR pathway are strongly implicated in neuroinflammation, neurodevelopment, and synaptic plasticity, and their activation is commonly associated with major neurodegenerative diseases (113, 118, 119, 122, 123). Accordingly, pharmacological inhibition of SAPK activity or the ISR pathway has been proposed as a therapeutic strategy for suppressing their pathogenesis and neuronal loss. Nonetheless, various cellular stresses of non-ribosomal origin also activate the SAPK and ISR pathways. We anticipate that animal models for the ribosome-specific factors and their genetic assessments will validate the direct relevance of the two ribosomal surveillance pathways to specific neural physiology. We also note that RQC and ISR are conserved across species, including yeast, whereas ZAK homologs are found in select species. It will be interesting to determine if RSR has acquired any distinct function during the evolution of animal species.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the Suh Kyungbae Foundation (SUHF-17020101); from the National Research Foundation funded by the Ministry of Science and Information & Communication Technology (MSIT), Republic of Korea (NRF-2021R1A2C3011706; NRF-2021M3A9G8022960; NRF-2018R1A5A1024261).

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicting interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Collart MA, Weiss B. Ribosome pausing, a dangerous necessity for co-translational events. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:1043–1055. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stein KC, Frydman J. The stop-and-go traffic regulating protein biogenesis: how translation kinetics controls proteostasis. J Biol Chem. 2019;294:2076–2084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.REV118.002814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D'Orazio KN, Green R. Ribosome states signal RNA quality control. Mol Cell. 2021;81:1372–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolin SL, Maquat LE. Cellular RNA surveillance in health and disease. Science. 2019;366:822–827. doi: 10.1126/science.aax2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandman O, Hegde RS. Ribosome-associated protein quality control. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2016;23:7–15. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inada T. Quality controls induced by aberrant translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:1084–1096. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joazeiro CAP. Mechanisms and functions of ribosome-associated protein quality control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019;20:368–383. doi: 10.1038/s41580-019-0118-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sitron CS, Brandman O. Detection and degradation of stalled nascent chains via ribosome-associated quality control. Annu Rev Biochem. 2020;89:417–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-013118-110729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meydan S, Guydosh NR. A cellular handbook for collided ribosomes: surveillance pathways and collision types. Curr Genet. 2021;67:19–26. doi: 10.1007/s00294-020-01111-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vind AC, Genzor AV, Bekker-Jensen S. Ribo-somal stress-surveillance: three pathways is a magic number. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:10648–10661. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yip MCJ, Shao S. Detecting and rescuing stalled ribosomes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2021;46:731–743. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikeuchi K, Izawa T, Inada T. Recent progress on the molecular mechanism of quality controls induced by ribosome stalling. Front Genet. 2019;9:743. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2018.00743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoemaker CJ, Green R. Translation drives mRNA quality control. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19:594–601. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garshott DM, Sundaramoorthy E, Leonard M, Bennett EJ. Distinct regulatory ribosomal ubiquitylation events are reversible and hierarchically organized. Elife. 2020;9:e54023. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Higgins R, Gendron JM, Rising L, et al. The unfolded protein response triggers site-specific regulatory ubiquitylation of 40S ribosomal proteins. Mol Cell. 2015;59:35–49. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.04.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juszkiewicz S, Chandrasekaran V, Lin Z, Kraatz S, Ramakrishnan V, Hegde RS. ZNF598 is a quality control sensor of collided ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2018;72:469–481. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vind AC, Snieckute G, Blasius M, et al. ZAKalpha recognizes stalled ribosomes through partially redundant sensor domains. Mol Cell. 2020;78:700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu CC, Peterson A, Zinshteyn B, Regot S, Green R. Ribosome collisions trigger general stress res-ponses to regulate cell fate. Cell. 2020;182:404–416. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yan LL, Zaher HS. Ribosome quality control antagonizes the activation of the integrated stress response on colliding ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2021;81:614–628. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.11.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Juszkiewicz S, Hegde RS. Initiation of quality control during poly(A) translation requires site-specific ribosome ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2017;65:743–750. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sundaramoorthy E, Leonard M, Mak R, Liao J, Fulzele A, Bennett EJ. ZNF598 and RACK1 regulate mammalian ribosome-associated quality control function by mediating regulatory 40S ribosomal ubiquitylation. Mol Cell. 2017;65:751–760. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ikeuchi K, Tesina P, Matsuo Y, et al. Collided ribosomes form a unique structural interface to induce Hel2-driven quality control pathways. EMBO J. 2019;38:e100276. doi: 10.15252/embj.2018100276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hashimoto S, Sugiyama T, Yamazaki R, Nobuta R, Inada T. Identification of a novel trigger complex that facilitates ribosome-associated quality control in mammalian cells. Sci Rep. 2020;10:3422. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-60241-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Juszkiewicz S, Speldewinde SH, Wan L, Svejstrup JQ, Hegde RS. The ASC-1 complex disassembles collided ribosomes. Mol Cell. 2020;79:603–614. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Matsuo Y, Ikeuchi K, Saeki Y, et al. Ubiquitination of stalled ribosome triggers ribosome-associated quality control. Nat Commun. 2017;8:159. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00188-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Orazio KN, Wu CC, Sinha N, Loll-Krippleber R, Brown GW, Green R. The endonuclease Cue2 cleaves mRNAs at stalled ribosomes during No Go Decay. Elife. 2019;8:e49117. doi: 10.7554/eLife.49117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glover ML, Burroughs AM, Monem PC, et al. NONU-1 encodes a conserved endonuclease required for mRNA translation surveillance. Cell Rep. 2020;30:4321–4331. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer C, Garzia A, Morozov P, Molina H, Tuschl T. The G3BP1-family-USP10 deubiquitinase complex rescues ubiquitinated 40S subunits of ribosomes stalled in translation from lysosomal degradation. Mol Cell. 2020;77:1193–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hickey KL, Dickson K, Cogan JZ, et al. GIGYF2 and 4EHP inhibit translation initiation of defective messenger RNAs to assist ribosome-associated quality control. Mol Cell. 2020;79:950–962. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juszkiewicz S, Slodkowicz G, Lin Z, Freire-Pritchett P, Peak-Chew SY, Hegde RS. Ribosome collisions trigger cis-acting feedback inhibition of translation initiation. Elife. 2020;9:e60038. doi: 10.7554/eLife.60038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weber R, Chung MY, Keskeny C, et al. 4EHP and GIGYF1/2 mediate translation-coupled messenger rna de-cay. Cell Rep. 2020;33:108262. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sinha NK, Ordureau A, Best K, et al. EDF1 coordinates cellular responses to ribosome collisions. Elife. 2020;9:e58828. doi: 10.7554/eLife.58828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garzia A, Jafarnejad SM, Meyer C, et al. The E3 ubiquitin ligase and RNA-binding protein ZNF598 orchestrates ribosome quality control of premature polyadenylated mRNAs. Nat Commun. 2017;8:16056. doi: 10.1038/ncomms16056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hildebrandt A, Bruggemann M, Ruckle C, et al. The RNA-binding ubiquitin ligase MKRN1 functions in ribosome-associated quality control of poly(A) translation. Genome Biol. 2019;20:216. doi: 10.1186/s13059-019-1814-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.DiGiuseppe S, Rollins MG, Bartom ET, Walsh D. ZNF598 plays distinct roles in interferon-stimulated gene expression and poxvirus protein synthesis. Cell Rep. 2018;23:1249–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.03.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sitron CS, Brandman O. CAT tails drive degradation of stalled polypeptides on and off the ribosome. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2019;26:450–459. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bengtson MH, Joazeiro CA. Role of a ribosome-associated E3 ubiquitin ligase in protein quality control. Nature. 2010;467:470–473. doi: 10.1038/nature09371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandman O, Stewart-Ornstein J, Wong D, et al. A ribosome-bound quality control complex triggers degradation of nascent peptides and signals translation stress. Cell. 2012;151:1042–1054. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.10.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Defenouillere Q, Yao Y, Mouaikel J, et al. Cdc48-associated complex bound to 60S particles is required for the clearance of aberrant translation products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:5046–5051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221724110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lyumkis D, Oliveira dos Passos D, Tahara EB, et al. Structural basis for translational surveillance by the large ribosomal subunit-associated protein quality control complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15981–15986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1413882111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shao S, Brown A, Santhanam B, Hegde RS. Structure and assembly pathway of the ribosome quality control complex. Mol Cell. 2015;57:433–444. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen PS, Park J, Qin Y, et al. Rqc2p and 60S ribosomal subunits mediate mRNA-independent elongation of nascent chains. Science. 2015;347:75–78. doi: 10.1126/science.1259724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kuroha K, Zinoviev A, Hellen CUT, Pestova TV. Release of ubiquitinated and non-ubiquitinated nascent chains from stalled mammalian ribosomal complexes by ANKZF1 and Ptrh1. Mol Cell. 2018;72:286–302. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verma R, Reichermeier KM, Burroughs AM, et al. Vms1 and ANKZF1 peptidyl-tRNA hydrolases release nascent chains from stalled ribosomes. Nature. 2018;557:446–451. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0022-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zurita Rendon O, Fredrickson EK, Howard CJ, et al. Vms1p is a release factor for the ribosome-associated quality control complex. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2197. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04564-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma R, Oania RS, Kolawa NJ, Deshaies RJ. Cdc48/p97 promotes degradation of aberrant nascent polypeptides bound to the ribosome. Elife. 2013;2:e00308. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thrun A, Garzia A, Kigoshi-Tansho Y, et al. Convergence of mammalian RQC and C-end rule proteolytic pathways via alanine tailing. Mol Cell. 2021;81:2112–2122. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2021.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Udagawa T, Seki M, Okuyama T, et al. Failure to degrade CAT-Tailed proteins disrupts neuronal morpho-genesis and cell survival. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108599. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choe YJ, Park SH, Hassemer T, et al. Failure of RQC machinery causes protein aggregation and proteotoxic stress. Nature. 2016;531:191–195. doi: 10.1038/nature16973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kostova KK, Hickey KL, Osuna BA, et al. CAT-tailing as a fail-safe mechanism for efficient degradation of stalled nascent polypeptides. Science. 2017;357:414–417. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lytvynenko I, Paternoga H, Thrun A, et al. Alanine tails signal proteolysis in bacterial ribosome-associated quality control. Cell. 2019;178:76–90. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Osuna BA, Howard CJ, Kc S, Frost A, Weinberg DE. In vitro analysis of RQC activities provides insights into the mechanism and function of CAT tailing. Elife. 2017;6:e27949. doi: 10.7554/eLife.27949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yonashiro R, Tahara EB, Bengtson MH, et al. The Rqc2/Tae2 subunit of the ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) complex marks ribosome-stalled nascent polypeptide chains for aggregation. Elife. 2016;5:e11794. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Koren I, Timms RT, Kula T, Xu Q, Li MZ, Elledge SJ. The eukaryotic proteome is shaped by E3 ubiquitin ligases targeting C-terminal degrons. Cell. 2018;173:1622–1635. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin HC, Yeh CW, Chen YF, et al. C-terminal end-directed protein elimination by CRL2 ubiquitin ligases. Mol Cell. 2018;70:602–613. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rusnac DV, Lin HC, Canzani D, et al. Recognition of the diglycine C-end degron by CRL2(KLHDC2) ubiquitin ligase. Mol Cell. 2018;72:813–822. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Simms CL, Yan LL, Zaher HS. Ribosome collision is critical for quality control during No-Go Decay. Mol Cell. 2017;68:361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Young DJ, Meydan S, Guydosh NR. 40S ribosome profiling reveals distinct roles for Tma20/Tma22 (MCT-1/DENR) and Tma64 (eIF2D) in 40S subunit recycling. Nat Commun. 2021;12:2976. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23223-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Phillips BP, Miller EA. Ribosome-associated quality control of membrane proteins at the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2020;133:jcs251983. doi: 10.1242/jcs.251983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang L, Ye Y. Clearing traffic jams during protein translocation across membranes. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:610689. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.610689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hegde RS, Kang SW. The concept of translocational regulation. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:225–232. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200804157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nyathi Y, Wilkinson BM, Pool MR. Co-translational targeting and translocation of proteins to the endoplasmic reticulum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1833:2392–2402. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Arribere JA, Fire AZ. Nonsense mRNA suppression via nonstop decay. Elife. 2018;7:e33292. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Han P, Shichino Y, Schneider-Poetsch T, et al. Genome-wide survey of ribosome collision. Cell Rep. 2020;31:107610. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.107610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Arakawa S, Yunoki K, Izawa T, Tamura Y, Nishikawa S, Endo T. Quality control of nonstop membrane proteins at the ER membrane and in the cytosol. Sci Rep. 2016;6:30795. doi: 10.1038/srep30795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cesaratto F, Sasset L, Myers MP, Re A, Petris G, Burrone OR. BiP/GRP78 mediates ERAD targeting of proteins produced by membrane-bound ribosomes stalled at the STOP-codon. J Mol Biol. 2019;431:123–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2018.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crowder JJ, Geigges M, Gibson RT, et al. Rkr1/Ltn1 ubiquitin ligase-mediated degradation of translationally stalled endoplasmic reticulum proteins. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:18454–18466. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.663559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wu X, Rapoport TA. Mechanistic insights into ER-associated protein degradation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2018;53:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.von der Malsburg K, Shao S, Hegde RS. The ribosome quality control pathway can access nascent polypeptides stalled at the Sec61 translocon. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2168–2180. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-01-0040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lakshminarayan R, Phillips BP, Binnian IL, et al. Pre-emptive quality control of a misfolded membrane protein by ribosome-driven effects. Curr Biol. 2020;30:854–864. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Matsuo Y, Inada T. The ribosome collision sensor Hel2 functions as preventive quality control in the secretory pathway. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108877. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang L, Xu Y, Rogers H, et al. UFMylation of RPL26 links translocation-associated quality control to endoplasmic reticulum protein homeostasis. Cell Res. 2020;30:5–20. doi: 10.1038/s41422-019-0236-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Izawa T, Park SH, Zhao L, Hartl FU, Neupert W. Cytosolic protein Vms1 links ribosome quality control to mitochondrial and cellular homeostasis. Cell. 2017;171:890–903. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Su T, Izawa T, Thoms M, et al. Structure and function of Vms1 and Arb1 in RQC and mitochondrial proteome homeostasis. Nature. 2019;570:538–542. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1307-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wu Z, Tantray I, Lim J, et al. MISTERMINATE mechanistically links mitochondrial dysfunction with proteostasis failure. Mol Cell. 2019;75:835–848. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wu Z, Wang Y, Lim J, et al. Ubiquitination of ABCE1 by NOT4 in response to mitochondrial damage links co-translational quality control to PINK1-directed mitophagy. Cell Metab. 2018;28:130–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Defenouillere Q, Zhang E, Namane A, Mouaikel J, Jacquier A, Fromont-Racine M. Rqc1 and Ltn1 prevent C-terminal alanine-threonine tail (CAT-tail)-induced protein aggregation by efficient recruitment of Cdc48 on stalled 60S subunits. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12245–12253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.722264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Anton LC, Yewdell JW. Translating DRiPs: MHC class I immunosurveillance of pathogens and tumors. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;95:551–562. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1113599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yewdell JW. DRiPs solidify: progress in understanding endogenous MHC class I antigen processing. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:548–558. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Trentini DB, Pecoraro M, Tiwary S, et al. Role for ribosome-associated quality control in sampling proteins for MHC class I-mediated antigen presentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:4099–4108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1914401117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chu J, Hong NA, Masuda CA, et al. A mouse forward genetics screen identifies LISTERIN as an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2097–2103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812819106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ahmed A, Wang M, Bergant G, et al. Biallelic loss-of-function variants in NEMF cause central nervous system impairment and axonal polyneuropathy. Hum Genet. 2021;140:579–592. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02226-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Anazi S, Maddirevula S, Faqeih E, et al. Clinical genomics expands the morbid genome of intellectual disability and offers a high diagnostic yield. Mol Psychiatry. 2017;22:615–624. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Martin PB, Kigoshi-Tansho Y, Sher RB, et al. NEMF mutations that impair ribosome-associated quality control are associated with neuromuscular disease. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4625. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18327-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nowakowski TJ, Bhaduri A, Pollen AA, et al. Spatiotemporal gene expression trajectories reveal developmental hierarchies of the human cortex. Science. 2017;358:1318–1323. doi: 10.1126/science.aap8809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ishimura R, Nagy G, Dotu I, et al. Ribosome stalling induced by mutation of a CNS-specific tRNA causes neurodegeneration. Science. 2014;345:455–459. doi: 10.1126/science.1249749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ishimura R, Nagy G, Dotu I, Chuang JH, Ackerman SL. Activation of GCN2 kinase by ribosome stalling links translation elongation with translation initiation. Elife. 2016;5:e14295. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Terrey M, Adamson SI, Gibson AL, et al. GTPBP1 resolves paused ribosomes to maintain neuronal homeostasis. Elife. 2020;9:e62731. doi: 10.7554/eLife.62731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bertoli-Avella AM, Garcia-Aznar JM, Brandau O, et al. Biallelic inactivating variants in the GTPBP2 gene cause a neurodevelopmental disorder with severe intellectual disability. Eur J Hum Genet. 2018;26:592–598. doi: 10.1038/s41431-018-0097-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Carter MT, Venkateswaran S, Shapira-Zaltsberg G, et al. Clinical delineation of GTPBP2-associated neuro-ectodermal syndrome: report of two new families and review of the literature. Clin Genet. 2019;95:601–606. doi: 10.1111/cge.13523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jaberi E, Rohani M, Shahidi GA, et al. Identification of mutation in GTPBP2 in patients of a family with neurodegeneration accompanied by iron deposition in the brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;38:216 e211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.O'Connell AE, Gerashchenko MV, O'Donohue MF, et al. Mammalian Hbs1L deficiency causes congenital anomalies and developmental delay associated with Pelota depletion and 80S monosome accumulation. PLoS Genet. 2019;15:e1007917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sankaran VG, Joshi M, Agrawal A, et al. Rare complete loss of function provides insight into a pleiotropic genome-wide association study locus. Blood. 2013;122:3845–3847. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-09-528315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Terrey M, Adamson SI, Chuang JH, Ackerman SL. Defects in translation-dependent quality control pathways lead to convergent molecular and neurodevelopmental pathology. Elife. 2021;10:e66904. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Li S, Wu Z, Tantray I, et al. Quality-control mechanisms targeting translationally stalled and C-termi-nally extended poly(GR) associated with ALS/FTD. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:25104–25115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2005506117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eshraghi M, Karunadharma PP, Blin J, et al. Mutant Huntingtin stalls ribosomes and represses protein synthesis in a cellular model of Huntington disease. Nat Commun. 2021;12:1461. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21637-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yang J, Hao X, Cao X, Liu B, Nystrom T. Spatial sequestration and detoxification of Huntingtin by the ribosome quality control complex. Elife. 2016;5:e11792. doi: 10.7554/eLife.11792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zheng J, Yang J, Choe YJ, et al. Role of the ribosomal quality control machinery in nucleocytoplasmic translocation of polyQ-expanded huntingtin exon-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;493:708–717. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.08.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krumm N, Turner TN, Baker C, et al. Excess of rare, inherited truncating mutations in autism. Nat Genet. 2015;47:582–588. doi: 10.1038/ng.3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wang T, Guo H, Xiong B, et al. De novo genic mutations among a Chinese autism spectrum disorder cohort. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13316. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thyme SB, Pieper LM, Li EH, et al. Phenotypic landscape of schizophrenia-associated genes defines can-didates and their shared functions. Cell. 2019;177:478–491. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.01.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Saini P, Rudakou U, Yu E, et al. Association study of DNAJC13, UCHL1, HTRA2, GIGYF2, and EIF4G1 with Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;100:119 e117–119. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Giovannone B, Tsiaras WG, de la Monte S, et al. GIGYF2 gene disruption in mice results in neurodegeneration and altered insulin-like growth factor signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4629–4639. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Adomavicius T, Guaita M, Zhou Y, et al. The structural basis of translational control by eIF2 phospho-rylation. Nat Commun. 2019;10:2136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10167-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Jennings MD, Kershaw CJ, Adomavicius T, Pavitt GD. Fail-safe control of translation initiation by dissociation of eIF2alpha phosphorylated ternary complexes. Elife. 2017;6:e24542. doi: 10.7554/eLife.24542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Krishnamoorthy T, Pavitt GD, Zhang F, Dever TE, Hinnebusch AG. Tight binding of the phosphorylated alpha subunit of initiation factor 2 (eIF2alpha) to the regulatory subunits of guanine nucleotide exchange factor eIF2B is required for inhibition of translation initiation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:5018–5030. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.15.5018-5030.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Dong J, Qiu H, Garcia-Barrio M, Anderson J, Hinnebusch AG. Uncharged tRNA activates GCN2 by displacing the protein kinase moiety from a bipartite tRNA-binding domain. Mol Cell. 2000;6:269–279. doi: 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Inglis AJ, Masson GR, Shao S, et al. Activation of GCN2 by the ribosomal P-stalk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:4946–4954. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1813352116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Harding HP, Ordonez A, Allen F, et al. The ribosomal P-stalk couples amino acid starvation to GCN2 activation in mammalian cells. Elife. 2019;8:e50149. doi: 10.7554/eLife.50149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jandhyala DM, Ahluwalia A, Obrig T, Thorpe CM. ZAK: a MAP3Kinase that transduces Shiga toxin- and ricin-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:1468–1477. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01139.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang X, Mader MM, Toth JE, et al. Complete inhibition of anisomycin and UV radiation but not cytokine induced JNK and p38 activation by an aryl-substituted dihydropyrrolopyrazole quinoline and mixed lineage kinase 7 small interfering RNA. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:19298–19305. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Canovas B, Nebreda AR. Diversity and versatility of p38 kinase signalling in health and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:346–366. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00322-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Coffey ET. Nuclear and cytosolic JNK signalling in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:285–299. doi: 10.1038/nrn3729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Meydan S, Guydosh NR. Disome and trisome profiling reveal genome-wide targets of ribosome quality control. Mol Cell. 2020;79:588–602. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Arpat AB, Liechti A, De Matos M, Dreos R, Janich P, Gatfield D. Transcriptome-wide sites of collided ribosomes reveal principles of translational pausing. Genome Res. 2020;30:985–999. doi: 10.1101/gr.257741.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhao T, Chen YM, Li Y, et al. Disome-seq reveals widespread ribosome collisions that promote cotranslational protein folding. Genome Biol. 2021;22:16. doi: 10.1186/s13059-020-02256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Klauer AA, van Hoof A. Degradation of mRNAs that lack a stop codon: a decade of nonstop progress. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2012;3:649–660. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Costa-Mattioli M, Walter P. The integrated stress response: from mechanism to disease. Science. 2020;368:eaat5314. doi: 10.1126/science.aat5314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Pakos-Zebrucka K, Koryga I, Mnich K, Ljujic M, Samali A, Gorman AM. The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep. 2016;17:1374–1395. doi: 10.15252/embr.201642195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Wek RC. Role of eIF2alpha Kinases in Translational Control and Adaptation to Cellular Stress. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:e032870. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a032870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Spielmann M, Kakar N, Tayebi N, et al. Exome sequencing and CRISPR/Cas genome editing identify mutations of ZAK as a cause of limb defects in humans and mice. Genome Res. 2016;26:183–191. doi: 10.1101/gr.199430.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Asih PR, Prikas E, Stefanoska K, Tan ARP, Ahel HI, Ittner A. Functions of p38 MAP kinases in the central nervous system. Front Mol Neurosci. 2020;13:570586. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2020.570586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Bond S, Lopez-Lloreda C, Gannon PJ, Akay-Espinoza C, Jordan-Sciutto KL. The integrated stress response and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha in neurodegeneration. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2020;79:123–143. doi: 10.1093/jnen/nlz129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]