Abstract

OBJECTIVES

This study sought to describe clinical and procedural characteristics of veterans undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) within U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) centers and to examine their association with short- and long-term mortality, length of stay (LOS), and rehospitalization within 30 days.

BACKGROUND

Veterans with severe aortic stenosis frequently undergo TAVR at VA medical centers.

METHODS

Consecutive veterans undergoing TAVR between 2012 and 2017 were included. Patient and procedural characteristics were obtained from the VA Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking system. The primary outcomes were 30-day and 1-year survival, LOS >6 days, and rehospitalization within 30 days. Logistic regression and Cox proportional hazards analyses were performed to evaluate the associations between pre-procedural characteristics and LOS and rehospitalization.

RESULTS

Nine hundred fifty-nine veterans underwent TAVR at 8 VA centers during the study period, 860 (90%) by transfemoral access, 50 (5%) transapical, 36 (3.8%) transaxillary, and 3 (0.3%) transaortic. Men predominated (939 of 959 [98%]), with an average age of 78.1 years. There were 28 deaths within 30 days (2.9%) and 134 at 1 year (14.0%). Median LOS was 5 days, and 141 veterans were rehospitalized within 30 days (14.7%). Nonfemoral access (odds ratio: 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.10 to 2.74), heart failure (odds ratio: 2.51; 95% CI: 1.83 to 3.44), and atrial fibrillation (odds ratio: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.95) were associated with increased LOS. Atrial fibrillation was associated with 30-day rehospitalization (hazard ratio: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.63).

CONCLUSIONS

Veterans undergoing TAVR at VA centers are predominantly elderly men with significant comorbidities. Clinical outcomes of mortality and rehospitalization at 30 days and 1-year mortality compare favorably with benchmark outcome data outside the VA.

Keywords: aortic stenosis, transcatheter aortic valve replacement, veterans

In 2011, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first transcatheter prosthetic aortic valve system, the balloon-expandable SAPIEN valve (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, California), for treatment of patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) at prohibitive risk for surgical valve replacement (1). Against that backdrop, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) developed a process for approval of intramural transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) sites that supplemented the approval and vetting process already implemented by the first FDA-approved TAVR vendor (Edwards Lifesciences) (2). TAVR has been performed at VA medical centers since 2011, when the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston became the first to develop a TAVR program (2,3). Following that initial pilot experience, a total of 8 VA TAVR centers have been approved to date, among approximately 40 to 45 VA centers that perform surgical aortic valve replacement.

Although Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services reimbursement is not a direct factor for TAVR implementation at VA medical centers, a white paper was created by a group of TAVR experts to guide the development of internal VA requirements harmonized to the experiential, personnel, and other key requirements of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services while imposing additional VA-specific standards. These included independent multidisciplinary site inspections and stringent hybrid operating room standards that exceed requirements outside the VA system (4,5). Dual over-sight standards and dual structured reporting were also mandated, via both the VA Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking System (CART) program, a national clinical quality and safety program for invasive cardiac procedures, and the National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program (6–8). This process was accompanied by the establishment of a national VA quality committee of peer experts to optimize quality improvement opportunities through a real-time alert system and periodic conference calls to monitor and collectively discuss every major adverse event at any VA center.

TAVR has since become an increasingly used treatment option for patients with severe AS, both within the VA and more generally, and is associated with low peri-procedural morbidity and mortality (9–11). In 2014, the FDA approved a second TAVR device in the United States—the first self-expanding prosthetic valve (CoreValve System, Medtronic, Minneapolis, Minnesota)—and both valve types are now in routine clinical use in VA TAVR centers (9,12). In August 2016, the FDA expanded the indications for TAVR to include patients at intermediate surgical risk, which has continued to increase the number of patients referred for TAVR consideration, and the VA has not been immune to this trend (13).

Initial results from the Houston VA’s experience demonstrated clinical outcomes that compared favorably with those in the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves) trial (3,11). As with the introduction of any new procedural treatment, careful patient selection may influence the initial experience and results. Veterans are known to have a different cardiovascular risk profile from non-veterans, and their experience and outcomes after TAVR in a pure veteran population, performed in dedicated intramural TAVR programs, may be quite different from results in the general population (14–17). We therefore sought to describe the characteristics and procedural experiences of veterans undergoing TAVR at VA medical centers. We also sought to evaluate whether certain patient and procedural characteristics were associated with favorable outcomes among veterans, particularly survival at 30 days, freedom from rehospitalization within 30 days, and length of the index hospital stay.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION.

The VA CART program is a national quality and safety program for invasive cardiac procedures performed by cardiologists throughout the VA health care system (6,7). Because of VA policies regarding veterans’ data security, the VA does not participate in the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS) TVT (Transcatheter Valve Therapy) (TVT) Registry and instead uses the intramural CART registry. As described previously, this program captures standardized patient and procedural elements for all coronary and structural heart interventions performed throughout the VA (6). Data collection for structural heart interventions is derived from previously established data definitions from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (7). The present analysis included all patients undergoing TAVR at any VA medical center between the time of initial FDA approval in 2011 and December 31, 2017. During this study period, an indeterminate number of veterans underwent TAVR outside the VA through a combination of the VA-funded Veterans Choice Program, local arrangements and/or contracts with affiliated universities or other local TAVR programs, or direct access using private insurance or Medicare. This analysis was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institution Review Board, which includes the Rocky Mountain Regional VA Medical Center, with a waiver of the requirement to obtain informed consent.

PATIENT AND PROCEDURAL CHARACTERISTICS.

Patient and procedural characteristics were prospectively collected and abstracted from the linked electronic medical record and cardiac catheterization report documentation. These data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, height, weight, and body mass index, as well as history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, tobacco use, coronary artery disease, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease, cerebrovascular disease, current use of dialysis, current use of an oral anticoagulant agent, prior coronary artery bypass graft or valve surgery, or prior percutaneous coronary intervention. Procedural characteristics were documented by the operators at the time of the procedure and included access site (transaortic, transapical, transaxillary, cutdown transfemoral, and percutaneous transfemoral), contrast amount, number of vascular access sites, largest sheath size, valve type, and in-laboratory complications.

POST-PROCEDURAL OUTCOMES.

The primary outcomes were survival at 30 days, rehospitalization within 30 days, and index length of stay >6 days. Mortality was ascertained from the VA Information Resource Center Vital Status File, which includes data from the Beneficiary Identification Record Locator Subsystem Death File, the VA Medicare Vital Status File, and the Social Security Administration Death Master File (18). Additional outcomes included index length of stay >6 days (2 days longer than the overall 5-day median), hospital readmission within 30 days, and in-hospital mortality. Hospital readmission was ascertained from the electronic medical record and supplemented with information from VA fee-basis files for those that were readmitted outside the integrated health care system. Additional secondary outcomes included intensive care unit length of stay, vascular complication during the index hospital stay, stroke within 30 days, and pacemaker insertion within 30 days. Procedural complications, including post-procedural vascular complications, were voluntarily reported by individual sites. The administrative codes used to assess readmission for stroke or pacemaker insertion are listed in Online Table 1.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS.

Differences in pre-procedural and procedural characteristics between patients receiving transfemoral access versus nonfemoral access, including death within 30 days, were compared using a chi-square test for categorical variables, Student’s t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables not normally distributed. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to estimate the associations between the predictors age, diabetes, dialysis use, atrial fibrillation, heart failure, chronic lung disease, body mass index, anticoagulant use, and access site with rehospitalization within 30 days. Logistic regression analysis was used to estimate the associations between the same predictors and the outcome of length of stay longer than 6 days. Log-rank testing was used to compare the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of veterans stratified by access site. All analyses were carried out using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). The assumption of proportional hazards was tested with plots of the standardized score process. A p value of <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

RESULTS

From 2011 to 2017, 959 veterans underwent TAVR at 8 VA medical centers, including 616 (64.6%) with the balloon-expandable Edwards valve and 319 (33.4%) with the self-expanding CoreValve. The majority of cases were performed with transfemoral access (860 [89.7%]), with a smaller percentage done by the apical (50 [5.3%]) or axillary (36 [3.8%]) approach. Table 1 presents the pre-procedural patient characteristics, stratified by transfemoral versus nonfemoral access site. The mean age was 78.1 years, and 97.9% were men. Veterans requiring nonfemoral access had significantly higher rates of peripheral arterial disease (77.8% vs. 39.8%; p < 0.001), prior coronary artery bypass graft surgery (58.6% vs. 37.6%; p < 0.001), chronic lung disease (59.6% vs. 44.9%; p = 0.005), and prior percutaneous coronary intervention (49.5% vs. 38.8%; p = 0.04).

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Veterans Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement at Veterans Affairs Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Centers, 2012 to 2017

| All Veterans (N = 959) |

Transfemoral Access (n = 860 [89.7%]) |

Other Access (n = 99 [10.3%]) |

p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at TAVR, yrs | 78.1 ± 9.0 | 78.3 ± 9.0 | 76.4 ± 8.3 | 0.04 |

| Male | 939 (97.9) | 842 (97.9) | 97 (98.0) | 0.96 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.2 ± 6.2 | 29.2 ± 6.2 | 28.6 ± 6.1 | 0.37 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 829 (86.4) | 742 (86.3) | 87 (87.9) | 0.66 |

| Black | 53 (5.5) | 50 (5.8) | 3 (3.0) | 0.25 |

| Hawaiian | 15 (1.6) | 12 (1.4) | 3 (3.0) | 0.21 |

| Indian | 7 (0.7) | 7 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.37 |

| Asian | 5 (0.5) | 4 (0.5) | 1 (1.0) | 0.48 |

| Hypertension | 915 (95.4) | 818 (95.1) | 97 (98.0) | 0.20 |

| Diabetes | 514 (53.6) | 463 (53.8) | 51 (51.5) | 0.66 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 880 (91.8) | 784 (91.2) | 96 (97.0) | 0.05 |

| Tobacco use (ever) | 549 (57.2) | 487 (56.6) | 62 (62.6) | 0.25 |

| Heart failure | 643 (67.0) | 569 (66.2) | 74 (74.7) | 0.09 |

| Myocardial infarction | 356 (37.1) | 316 (36.7) | 40 (40.4) | 0.48 |

| CABG | 381 (39.7) | 323 (37.6) | 58 (58.6) | <0.001 |

| Valve surgery | 120 (12.5) | 107 (12.4) | 13 (13.1) | 0.84 |

| PCI | 383 (39.9) | 334 (38.8) | 49 (49.5) | 0.04 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 417 (43.5) | 368 (42.8) | 49 (49.5) | 0.20 |

| Dialysis use | 56 (5.8) | 48 (5.6) | 8 (8.1) | 0.32 |

| Chronic lung disease | 445 (46.4) | 386 (44.9) | 59 (59.6) | 0.01 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 335 (34.9) | 296 (34.4) | 39 (39.4) | 0.33 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 419 (43.7) | 342 (39.8) | 77 (77.8) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 351 (36.6) | 317 (36.9) | 34 (34.3) | 0.62 |

| Oral anticoagulant use | 152 (15.8) | 135 (15.7) | 17 (17.2) | 0.70 |

Values are mean ± SD or n (%).

Chi-square test or Student’s t-test.

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement.

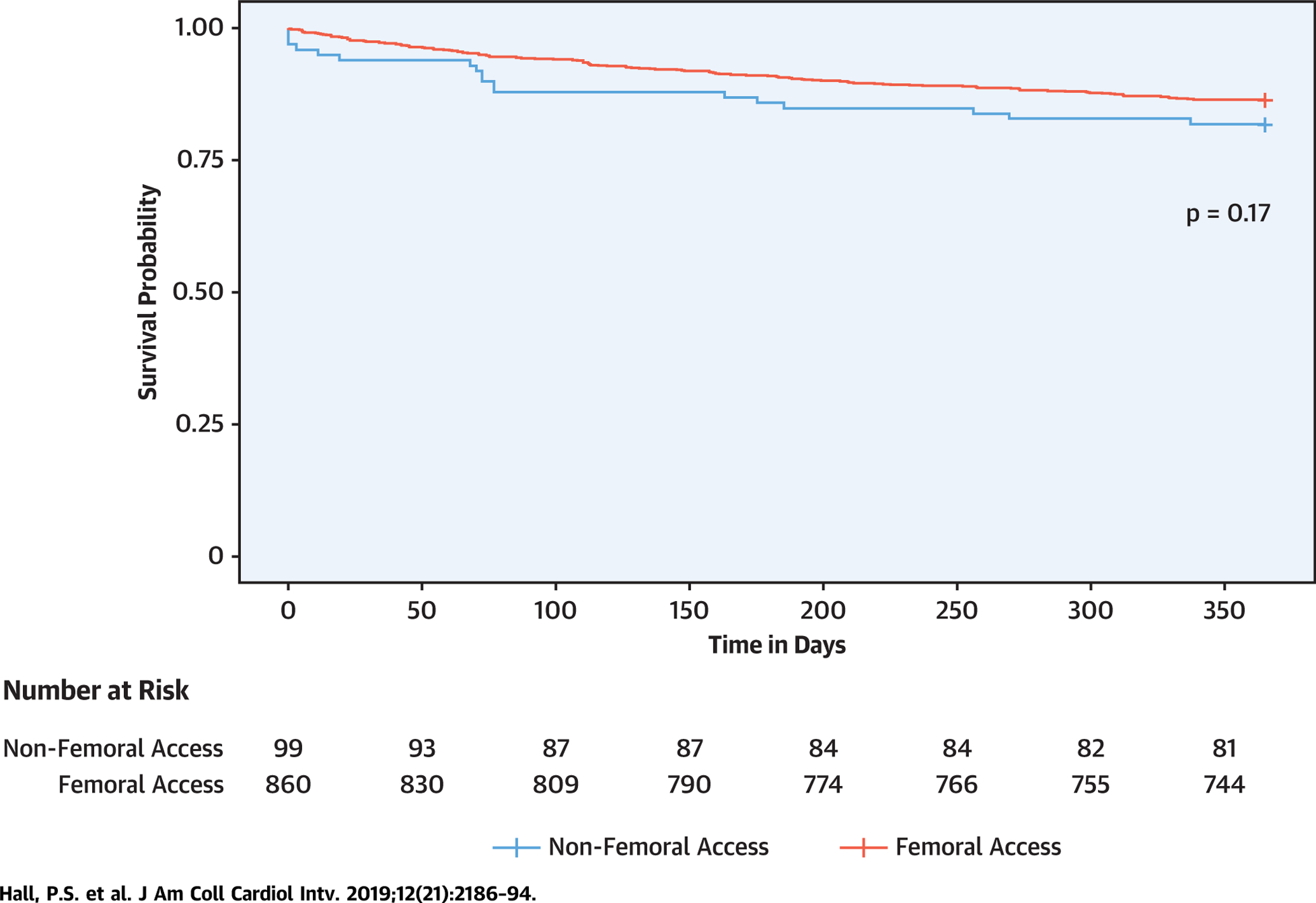

Table 2 presents the procedural characteristics, and Table 3 presents the procedural outcomes. A total of 699 veterans (73.7%) had percutaneous transfemoral access, and 161 (17.0%) received cutdown transfemoral access. Ten veterans (1.0%) had unspecified access sites. There were 28 deaths and 3 strokes within 30 days (2.9% and 0.3%, respectively), and 141 veterans were rehospitalized within 30 days (14.7%). The median length of stay was 5 days for transfemoral access and 7 days for nonfemoral access (p = 0.03). A total of 172 patients underwent pacemaker placement within 30 days (17.9%). The immediate intraprocedural complications are presented in Table 4. There were 16 in-hospital deaths (1.7%), including 3 intraprocedural deaths (0.3%). The Central Illustration presents the Kaplan-Meier survival curves for all patients and for all patients stratified by femoral versus other access site. The median follow-up duration was 365 days (interquartile range: 311 to 365 days). Complete mortality data at 1 year were not available for all veterans, but there were 134 deaths at 1 year (14.0%), and there was no statistically significant difference in mortality on the basis of access site (log-rank p = 0.17).

TABLE 2.

Procedural Characteristics of Veterans Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement at Veterans Affairs Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Centers, 2012 to 2017 (N = 959)

| Access site | |

| Transfemoral (percutaneous) | 699 (73.7) |

| Transfemoral (cutdown) | 161 (17.0) |

| Transapical | 50 (5.3) |

| Transaxillary | 36 (3.8) |

| Transaortic | 3 (0.3) |

| Unspecified | 10 (1.0) |

| Valve type | |

| Balloon expandable (Edwards SAPIEN) | 616 (64.6) |

| Self-expanding (Medtronic CoreValve) | 319 (33.4) |

| Mechanically expandable (Boston Scientific Lotus) | 19 (2.0) |

| Contrast (ml) | 145.7 ± 94.9 |

| Number of access sites | 3 ± 0.4 |

| Sheath size (F) | 16 (14–18) |

Values are n (%), mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range).

TABLE 3.

Procedural Outcomes of Veterans Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement at Veterans Affairs Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Centers, 2012 to 2017

| All Veterans (N = 959) |

Transfemoral Access (n = 860 [89.7%]) |

Other Access (n = 99 [10.3%]) |

p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Death within 30 days | 28 (2.9) | 22 (2.6) | 6 (6.1) | 0.05 |

| Total length of stay, days | 5 (3–8) | 5 (3–8) | 7 (3–10) | 0.03 |

| Rehospitalization within 30 days | 141 (14.7) | 124 (14.4) | 17 (17.2) | 0.46 |

| Vascular complication during stay | 25 (2.6) | 22 (2.6) | 3 (3.0) | 0.78 |

| ICU length of stay, days | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–4) | 2 (1–5) | 0.39 |

| Stroke within 30 days | 3 (0.3) | 3 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 0.56 |

| Pacemaker within 30 days | 172 (17.9) | 161 (18.7) | 11 (11.1) | 0.06 |

Values are n (%) or median (interquartile range).

Chi-square test or Mann-Whitney U test.

ICU = intensive care unit.

TABLE 4.

Immediate Intraprocedural Complications (N = 959)

| Death | 3 (0.3) |

| Dysrhythmia | 16 (1.7) |

| Valve embolization into ventricle | 1 (0.1) |

| Cardiogenic shock | 3 (0.3) |

| Annular rupture | 2 (0.2) |

| Arterial dissection/perforation | 5 (0.5) |

| Emergent CABG | 2 (0.2) |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass | 1 (0.1) |

| Acute pulmonary edema | 1 (0.1) |

| Limb ischemia | 5 (0.5) |

| Retroperitoneal hematoma | 1 (0.1) |

Values are n (%).

CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Survival Among Veterans Undergoing Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers by Access Site.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by transfemoral versus nonfemoral access. Includes 860 veterans (90.7%) who underwent transfemoral transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) compared with 89 (9.4%) who underwent nonfemoral TAVR. Log-rank p = 0.17.

Tables 5 and 6 demonstrate the associations with length of stay and with 30-day rehospitalization. Nonfemoral access (odds ratio: 1.74; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.10 to 2.74), heart failure (odds ratio: 2.51; 95% CI: 1.83 to 3.44), and atrial fibrillation (odds ratio: 1.40; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.95) were associated with higher odds of prolonged length of stay, and atrial fibrillation was also associated with higher risk for rehospitalization (hazard ratio: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.22 to 2.63).

TABLE 5.

Association of Patient Characteristics With Increased Length of Stay (Beyond 6 Days)

| Age (per year) | 1.01 (0.99–1.03) |

| Diabetes | 0.93 (0.70–1.24) |

| Dialysis use | 1.66 (0.94–2.92) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.40 (1.01–1.95) |

| Heart failure | 2.51 (1.83–3.44) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.92 (0.69–1.21) |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) | 1.21 (0.35–4.26) |

| Overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) | 0.93 (0.65–1.32) |

| Obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 0.73 (0.50–1.06) |

| Anticoagulant use | 0.64 (0.41–0.99) |

| Nonfemoral access | 1.74 (1.10–2.74) |

Values are odds ratio (95% CI).

BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval.

TABLE 6.

Association of Patient Characteristics With Rehospitalization Within 30 Days

| Age (per year) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

| Diabetes | 1.15 (0.81–1.64) |

| Dialysis use | 0.97 (0.49–1.93) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1.79 (1.22–2.63) |

| Heart failure | 1.04 (0.71–1.53) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 1.30 (0.93–1.84) |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5 kg/m2) | 2.33 (0.70–7.77) |

| Overweight (BMI >25 kg/m2) | 1.06 (0.68–1.64) |

| Obese (BMI >30 kg/m2) | 0.90 (0.57–1.43) |

| Anticoagulant use | 0.68 (0.41–1.13) |

| Nonfemoral access | 1.23 (0.73–2.08) |

Values are hazard ratio (95% CI).

Abbreviations as in Table 5.

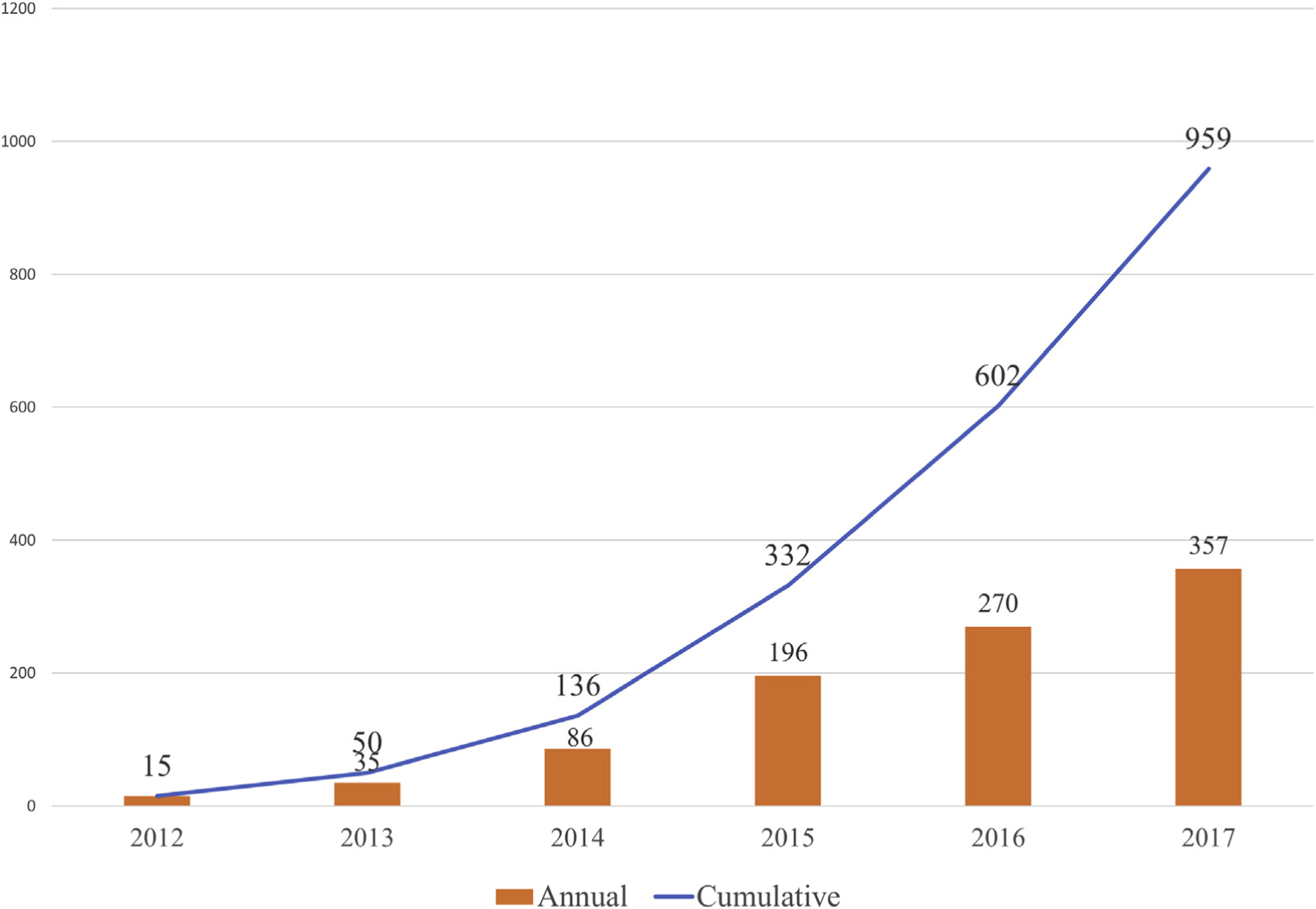

The cumulative TAVR experience at VA medical centers is displayed in Figure 1. There were 15 procedures performed in 2012, and the number has steadily grown, to 357 TAVRs performed at 8 centers in 2017.

FIGURE 1. Annual and Cumulative Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Performed at Veterans Affairs Medical Centers.

The number of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) procedures has consistently risen every year, as the number of approved Veterans Affairs (VA) TAVR centers has increased from 1 to 8.

DISCUSSION

We report here the collective outcomes of the first 959 veterans to undergo TAVR within the intramural network of VA TAVR centers. Veterans undergoing TAVR at VA centers are predominantly older men with significant comorbidities, presenting a different risk profile compared with nonveteran populations. The 2016 annual TVT Registry report, linked with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administrative claims, published the characteristics and outcomes of 54,782 patients who underwent TAVR from 2012 to 2015, and some comparison with that experience is instructive (Table 7) (19). The median age in the TVT Registry was higher than in our TAVR population (83.0 years vs. 78.7 years), and 48% were women compared with only 2.1% in our cohort. The prevalence of peripheral artery disease (44% vs. 32% in TVT) and prior cardiac surgery (40% vs. 31% in TVT) are both higher among the veteran population undergoing TAVR (10). The 2.9% 30-day mortality rate we report compares favorably with the 5.7% rate in the TVT Registry, as does the 1-year mortality rate of 14.0%, compared with 21% to 26% in the TVT registry, but this may be related to the higher prevalence of nonfemoral access in the TVT registry. In comparison, veterans had a higher rate of vascular complications and pacemaker placement than in the TVT registry. Direct comparison and adjustment of risk between registries remain a controversial challenge, and the definition of risk in multidisciplinary teams varies (20,21). STS risk scores were important “objective” measures for initial TAVR approval trials but are of declining relevance in clinical practice, in which the bar is simply intermediate (or moderate) risk. Currently, the surgical members of each VA heart team do not generally find a clinical need to calculate and document an STS score to determine if a patient is a candidate for TAVR. For example, an octogenarian veteran with prior sternotomy would at least be considered at moderate clinical risk. Consequently, capture of STS scores in our cohort declined over the enrollment period, and meaningful statements about the STS risk of our cohort are unfortunately not possible. Additional limitations include the incomplete mortality data at 1 year, incomplete recording of valve type and access site, and the lack of additional important predictors not included in CART, such as anesthesia or sedation type, ejection fraction, and the characterization of pulmonary and renal disease.

TABLE 7.

Comparison of the Veterans Affairs Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement Population With the 2016 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry Annual Report

| Veterans (n = 959) |

2016 STS TVT Registry Annual Report (19) (n = 54,782) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Median age at TAVR, yrs | 78.7 | 83.0 |

| Male | 939 (97.9) | 28,342 (51.7) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 829 (86.4) | 51,517 (94.0) |

| Black | 53 (5.5) | 2,056 (3.8) |

| Asian | 5 (0.5) | 628 (1.1) |

| Valve type | ||

| Balloon expandable | 616 (64.6) | 41,021 (74.9) |

| Self-expanding | 319 (33.4) | 12,815 (23.4) |

| Access site | ||

| Transfemoral | 860 (90.7) | 40,596 (74.1) |

| Transapical | 50 (5.3) | 9,318 (17) |

| Other | 39 (4.1) | 4,557 (8.3) |

| Death in-hospital | 16 (1.7) | 2,111 (3.9) |

| Death within 30 days | 28 (2.9) | 2,814 (5.7) |

| Death within 1 yr | 134 (14.0) | 21–26 |

| Stroke within 30 days | 3 (0.3) | 829 (1.9) |

| Pacemaker within 30 days | 172 (17.9) | 4,159 (11.8) |

| Vascular complication | 25 (2.6) | 551 (1.3) |

Values are n (%).

STS = Society of Thoracic Surgeons; TAVR = transcatheter aortic valve replacement; TVT = Transcatheter Valve Therapy.

The results reported here are somewhat heterogeneous, as a reflection of the rapid evolution of TAVR over the course of this experience across the 3 domains of: 1) best practices and collective experiences; 2) device iterations; and 3) patient risk profiles. For the first domain, best practices both broadly and within the VA have evolved, for example to a nearly universal abandonment of general anesthesia and transesophageal echocardiography, rare deviation from transfemoral percutaneous access, and selective removal of pacing wires at the end of each case. In the second domain, decreases in sheath size and advances in SAPIEN and CoreValve iterations have accompanied an increase in percutaneous transfemoral access. In the third domain of patient risk profile, competing trends are present. On one hand, the FDA approval of the use of TAVR in patients at intermediate surgical risk, combined with early reports and the ongoing studies in low-risk patients, has contributed to an overall decline in the risk profile of veterans undergoing evaluation for TAVR (13,15,22,23). On the other hand, certain highly comorbid patients who in the past would have been considered “cohort C” are successfully undergoing TAVR at more experienced VA TAVR centers (5,24–26). The net result is that over the enrollment period of this study, a given veteran’s risk for being ultimately deemed not a candidate for and not being offered TAVR after evaluation by an experienced heart team has declined precipitously, both within the VA and in the private sector. These competing trends likely drive a bifurcation of the risk profile within our cohort over time, superimposed on the overall decline.

CONCLUSIONS

This report, the first from the VA system of intramural TAVR programs, despite representing a heterogeneous experience during a period of several program initiations and rapid evolution, nevertheless demonstrates a robust experience of 959 patients with excellent outcomes across multiple dimensions. Through use of the data housed within the VA CART program, we will continue to evaluate how best to deliver quality care to our veterans.

Supplementary Material

PERSPECTIVES.

WHAT IS KNOWN?

Veterans with severe symptomatic AS undergoing TAVR have different cardiovascular risk profiles from nonveterans.

WHAT IS NEW?

Veterans’ initial outcomes at 8 intramural VA TAVR centers compare favorably with published outcomes from nonveterans undergoing TAVR.

WHAT IS NEXT?

Longer term follow-up of veterans undergoing TAVR will lead to better understanding of the difference in risk and allow better delivery of quality care to veterans.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hall has received research funding from the American College of Cardiology Foundation/Merck Research Award 2016. Dr. Garcia is a consultant for Surmodics, Osprey Medical, Medtronic, Edwards Lifesciences, and Boston Scientific; and has received research grants from Edwards Lifesciences and the VA Office of Research and Development. Dr. Bavry is a proctor for Edwards Lifesciences; and has received an honorarium from the American College of Cardiology. Dr. Banerjee has received speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Cardiovascular Systems, Gore, and Medtronic; and has received institutional research grants from Boston Scientific and Merck. Dr. Tseng has received research grants from the National Institutes of Health (5R01HL119857-04), a University of California-San Francisco, Surgical Innovations grant, VA CSP #588 Regroup, and Cryolife (Perclot trial); and is a founder of ReValve Med. Dr. Waldo receives unrelated investigator-initiated research support to the Denver Research Institute from Abiomed, Cardiovascular Systems, and Merck Pharmaceuticals. Dr. Shunk is a consultant for Medeon Bio, TransAortic Medical, and Terumo; and has received institutional research support from Siemens Medical Systems, Cardiovascular Systems, and Svelte Medical Systems. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the U.S. government. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- AS

aortic stenosis

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CART

Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking

- CI

confidence interval

- FDA

U.S. Food and Drug Administration

- HF

heart failure

- STS

Society of Thoracic Surgeons

- TAVR

transcatheter aortic valve replacement

- TVT

Transcatheter Valve Therapy

- VA

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Footnotes

APPENDIX For a supplemental table, please see the online version of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first artificial aortic heart valve placed without open-heart surgery. November 2, 2011. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/newsevents/newsroom/pressannouncements/ucm278348.htm. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- 2.Bakaeen FG, Kar B, Chu D, et al. Establishment of a transcatheter aortic valve program and heart valve team at a Veterans Affairs facility. Am J Surg 2012;204:643–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omer S, Kar B, Cornwell LD, et al. Early experience of a transcatheter aortic valve program at a Veterans Affairs facility. JAMA Surg 2013;148: 1087–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes DR, Mack MJ, Kaul S, et al. 2012 ACCF/AATS/SCAI/STS expert consensus document on transcatheter aortic valve replacement: developed in collaboration with the American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Heart Failure Society of America, Mended Hearts, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, and Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012;144:e29–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shunk KA, Zimmet J, Cason B, Speiser B, Tseng EE. Development of a Veterans Affairs hybrid operating room for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. JAMA Surg 2015;150:216–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maddox TM, Plomondon ME, Petrich M, et al. A national clinical quality program for Veterans Affairs catheterization laboratories (from the Veterans Affairs Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking Program). Am J Cardiol 2014;114: 1750–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Byrd JB, Vigen R, Plomondon ME, et al. Data quality of an electronic health record tool to support VA cardiac catheterization laboratory quality improvement: the VA Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking System for Cath Labs (CART) program. Am Heart J 2013;165:434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khuri SF, Daley J, Henderson W, et al. The Department of Veterans Affairs’ NSQIP: the first national, validated, outcome-based, risk-adjusted, and peer-controlled program for the measurement and enhancement of the quality of surgical care. National VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg 1998;228:491–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmes DR, Nishimura RA, Grover FL, et al. Annual outcomes with transcatheter valve therapy: from the STS/ACC TVT Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;66:2813–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holmes DR, Brennan JM, Rumsfeld JS, et al. Clinical outcomes at 1 year following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. JAMA 2015;313: 1019–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al. Two-year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012;366: 1686–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med 2014;371: 967–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves expanded indication for two transcatheter heart valves for patients at intermediate risk for death or complications associated with open-heart surgery. August 18, 2016. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm517281.htm. Accessed October 10, 2016.

- 14.Fryar CD, Herrick K, Afful J, Ogden CL. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among male veterans, U.S. 2009–2012. Am J Prev Med 2016;50: 101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garcia S, Kelly R, Mbai M, et al. Outcomes of intermediate-risk patients treated with transcatheter and surgical aortic valve replacement in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System: a single center 20-year experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2018;92:390–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldo SW, Gokhale M, O’Donnell CI, et al. Temporal trends in coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2018;11:879–88. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang J, Zimmet JM, Ponna VM, et al. Evolution of Veterans Affairs transcatheter aortic valve replacement program: the first 100 patients. J Heart Valve Dis 2018;27:24–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. VIReC Home. Available at: https://www.virec.research.va.gov/index.htm. Accessed July 27, 2016.

- 19.Grover FL, Vemulapalli S, Carroll JD, et al. 2016 annual report of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy Registry. J Am Coll Cardiol 2017;69:1215–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coylewright M, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, O’Gara PT. A call for an evidence-based approach to the heart team for patients with severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:1472–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reyes M, Reardon MJ. Transcatheter valve replacement: risk levels and contemporary outcomes. Methodist DeBakey Cardiovasc J 2017;13: 126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Waksman R, Rogers T, Torguson R, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in low-risk patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;72:2095–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bekeredjian R, Szabo G, Balaban Ü, et al. Patients at low surgical risk as defined by the Society of Thoracic Surgeons Score undergoing isolated interventional or surgical aortic valve implantation: in-hospital data and 1-year results from the German Aortic Valve Registry (GARY). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1323–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arnold SV, Spertus JA, Lei Y, et al. How to define a poor outcome after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: conceptual framework and empirical observations from the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve (PARTNER) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2013;6:591–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zimmet J, Kaiser E, Tseng E, Shunk K. Successful percutaneous management of partial avulsion of the native aortic valve complex complicating transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Invasive Cardiol 2014;26:E137–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma M, Tseng E, Schiller N, Moore P, Shunk KA. Closure of aortic paravalvular leak under intravascular ultrasound and intracardiac echocardiography guidance. J Invasive Cardiol 2011;23:E250–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.