Abstract

Abstract

The role of lateral lymph node dissection (LLND) during total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer is still controversial. Many reviews were published on prophylactic LLND in rectal cancer surgery, some biased by heterogeneity of overall associated treatments. The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to perform a timeline analysis of different treatments associated to prophylactic LLND vs no-LLND during TME for rectal cancer.

Methods

A literature search was performed in PubMed, SCOPUS and WOS for publications up to 1 September 2020. We considered RCTs and CCTs comparing oncologic and functional outcomes of TME with or without LLND in patients with rectal cancer.

Results

Thirty-four included articles and 29 studies enrolled 11,606 patients. No difference in 5-year local recurrence (in every subgroup analysis including preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy), 5-year distant and overall recurrence, 5-year overall survival and 5-year disease-free survival was found between LLND group and non LLND group. The analysis of post-operative functional outcomes reported hindered quality of life (urinary, evacuatory and sexual dysfunction) in LLND patients when compared to non LLND.

Conclusion

Our publication does not demonstrate that TME with LLND has any oncological advantage when compared to TME alone, showing that with the advent of neoadjuvant therapy, the advantage of LLND is lost. In this review, the most important bias is the heterogeneous characteristics of patients, cancer staging, different neoadjuvant therapy, different radiotherapy techniques and fractionation used in different studies. Higher rate of functional post-operative complications does not support routinely use of LLND.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00384-021-03946-2.

Keywords: Rectal cancer, Total mesorectal excision, Lateral pelvic lymphadenectomy

Introduction

Although commonly performed in urologic [1] and gynaecologic [2] surgery, the role of lateral lymph node dissection (LLND) is still a very controversial topic in rectal cancer treatment [3]. This procedure, reported in Japan in the 1970s [4, 5], was standardized by Moriya at the end of the 1980s: “On the basis of the extent of lateral node spread, two types of lateral node dissection were performed, consisting of preservation of internal iliac vessels (conventional) and en-bloc excision of these vessels (extended)” [6].

Currently, total mesorectal excision (TME) remains the gold standard for surgical treatment of mid and low rectal cancer. In contrast, the place of LLND remains a matter of controversy between Eastern and Western surgical guidelines [7–12]. The main conceptual difference is the fact that the lateral pelvic lymph nodes are considered as localized disease in Japanese clinical practice, whereas the West treats them as systemic disease [13–15]. For this reason, in Japan, prophylactic LLND is always performed in patients with stage II/III lower rectal cancer, whereas in the West, chemoradiotherapy (CRT) is routinely performed, thus generally avoiding a more invasive surgical approach [16].

To date, seven systematic reviews and meta-analyses have provided the highest levels of evidence to support the role of LLND for rectal cancer [17–23]. This new systematic review and meta-analysis aims to perform an updated analysis of the different types of treatments associated with prophylactic LLND vs. no-LLND (NLLND) in rectal cancer surgery.

Methods

We performed a systematic review adhering to AMSTAR 2 principles [24]. A literature search was performed from two authors (R.C., F.B.) in PubMed, SCOPUS and WOS for publications up to 1 September 2020. The protocol for this study was registered on PROSPERO, a prospective international database for reviews under the registration number 42020186525.

Inclusion criteria

We considered RCTs (randomized control trial) and CCTs (clinical control trials) comparing patients with rectal cancer who underwent rectal resection and TME with versus without LLND.

Exclusion criteria

Patients having surgery without TME.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed [25](ESM6). The keywords used for PubMed database research were: “extended lymphadenectomy,” “pelvic lymphadenectomy,” “lateral lymph-node dissection,” “total mesorectal excision,” “rectal resection,” “rectal cancer,” and their combinations. The search strategy performed on PubMed was the following: “extended lymphadenectomy”[All Fields] AND (“rectum”[MeSH Terms] OR rectum[All Fields]) “pelvic lymphadenectomy “[All Fields] AND (rectum[MeSH Terms] OR rectum[All Fields]) “lateral lymph-node dissection”[All Fields] AND (rectum[MeSH Terms] OR rectum[All Fields]).

We also manually searched the references of identified articles and relevant reviews and searched conference proceedings, theses and published abstracts on Google scholar. No language restriction was applied.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were the incidence of local recurrence and distant recurrence at 5 years. The secondary outcomes were the 5-year overall and disease-free survival and the incidence of urinary dysfunction (retention), urinary incontinence, evacuatory dysfunction and sexual dysfunction.

The assessment of methodological quality was performed independently by two authors (RC, CR). The risk of bias of randomized control trials (RCTs) was assessed using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [26] and the ROBINS-I tool [27] for observational studies. In the ROBINS-I tool, risk of bias is assessed within specified domains, including bias due to confounding, bias in selection of participants into the study, bias in classification of interventions, bias due to deviations from intended interventions bias due to missing data, bias in measurement of outcomes, bias in selection of the reported result and overall bias. Bias assessments were tabulated with explanation. Disagreements were resolved via discussion between the investigators. Graphic representation of the results was produced using the Robvis online tool [28] (ESM4-5).

Statistical analysis

This meta-analysis was conducted using the Review Manager (RevMan version 5.3.5) computer program (Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, 2014).

The dichotomous outcomes were pooled with a random-effects model with the Mantel-Haenszel method to estimate risk ratios (RRd) and their 95% confidence intervals [29]. Clinical heterogeneity was tested using τ2, Cochrane’s Q and I2 statistics. We considered an I2 value exceeding 50% to be indicative of heterogeneity [30].

We used a random-effect analysis model for the high clinical heterogeneity and statistically significant higher chi2 value and I2 [31]. In all remaining circumstances, we used the random-effects model.

The following subgroup analyses were performed to reduce the heterogeneity:

LLND vs. NLLND

LLND vs. NLLND and adjuvant therapy

LLND and adjuvant therapy vs. NLLND and adjuvant therapy

LLND vs nCRT and NLLND

nCRT and LLND vs nCRT and NLLND

Results

The PRISMA flow diagram for the systematic review is presented in SDC 1 (ESM1). The initial search yielded 2833 potentially relevant articles. After the removal of duplicates, 1767 studies underwent screening of titles/abstracts for relevance and assessment for eligibility; 1724 further articles were eventually excluded leaving 43 studies for analysis of the full text. Of these, nine studies, included in the other systematic review [17–23], were successively excluded (SDC 2)(ESM2) [5, 32–39]. The remaining 34 articles and 29 studies (11.606 patients: 5161 underwent LLND and 6445 NLLND) were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. One study (Tsukamoto 2020) [40] overlapped with a previous study (Fujita 2017) [41]. In effect, the study of Tsukamoto et al. is the result of a long-term follow-up of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) 0212 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00190541) published previously from Fujita et al. in 2017. The other studies included as RCT [40–44] are all based on the same trial (JCOG0212) and therefore represent the same group of patients. The studies of Nagawa 2001 [45] and Watanabe 2002 [7] are both from the same single institution with overlapped years.

Characteristics of the studies

The 28 included studies were published between 1994 and 2020; patients were enrolled between 1985 and 2016 (Table 1). In all studies, the cancer was located at the rectum, except one that also included patients with anal cancer [66]. The level of the cancer was reported in 22 studies. In 18 studies (85.7%%), the tumour was located in the lower rectum. A small proportion of studies included patients with upper rectal cancer (14.3%) [64, 67, 68].

Table 1.

Included studies

| Author and year of publication | Nation | Type of study | Time of enrolment | Location of cancer | Clinical AJCC staging | Patients included | Type of rectal resection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tsukamoto 2020 [40] | Japan | RCT | 2003-2010 | Rectum L | II/III | 701 | NR |

| 2 |

Oki 2019 [46] |

Japan | RCT | 2006-2009 | Rectum | I/II/III | 445 |

RAR APR HP Others |

| 3 | Nishizaki 2019 [47] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

NR | Rectum | NR | 155 | NR |

| 4 |

Ogura 2019 [48] |

Australia//Korea/Netherlands/Japan/UK/USA |

Prospective CCT |

2009-2013 | Rectum L | NR | 968 |

RAR APR PE Others |

| 5 | Matsuda 2018 [49] | Japan | Retrospective CCT | 2005-2016 | Rectum | I/II/III | 45 |

RAR APR HP Others |

| 6 |

Park 2018 [50] |

Korea | Retrospective CCT | 2011-2016 | Rectum L | II/III | 361 |

RAR APR HP |

| 7 |

Ito 2018 [43] |

Japan | RCT | 2003-2010 | Rectum | NR | 701 | NR |

| 8 |

Dev 2017 [51] |

India | RCT | NR | Rectum L | II/III | 240 | NR |

| 9 | Georgiu 2017 [17] | UK |

Retrospective CCT |

2006-2009 | Rectum | NR | 38 | PE |

| 10 | Ishihara 2017 [52] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

2003-2015 | Rectum L | NR | 222 |

RAR APR HP PE Others |

| 11 |

Fujita 2017 [41] |

Japan | RCT | 2003-2010 | Rectum L | II/III | 701 | RAR |

| 12 | Tamura 2017 [53] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

2000-2015 | Rectum L | IV | 50 | NR |

| 13 | Kim 2017 [54] | Korea |

Retrospective CCT |

NR | Rectum L | NR | 377 |

RAR APR |

| 14 | Ogura 2017 [48] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

2005-2014 | Rectum L | II/III | 363 |

RAR APR HP Others |

| 15 |

Saito 2016 [44] |

Japan | RCT | 2003-2010 | Rectum | II/III | 701 | NR |

| 16 |

Ozawa 2016 [55] |

Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1995-2004 | Rectum L | II/III | 998 |

RAR APR Others |

| 17 |

Akiyoshi 2019 [56] |

Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

2004-2010 | Rectum L | II-III | 127 |

RAR APR HP Others |

| 18 |

Fujita 2013 [42] |

Japan | RCT | 2003-2010 | Rectum L | II/III | 701 | RAR |

| 19 |

Akasu 2009 (79) |

Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1992-2006 | Rectum L | NR | 69 | NR |

| 20 | Kusters 2009 [57] | Netherlands/ Japan |

Prospective CCT |

1993-2002 | Rectum L | I/II/III | 1.079 |

RAR APR HP PE |

| 21 | Kobayashi 2009 [58] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1991-1998 | Rectum L | I/II/III | 1.272 | NR |

| 22 | Shiozawa 2007 [59] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1990-2000 | Rectum L | NR | 169 | NR |

| 23 | Kim 2007 [60] | Korea |

Retrospective CCT |

1995-2000 | Rectum L | III | 290 |

RAR APR |

| 24 |

Yano 2007 [61] |

Japan |

Prospective CCT |

1995-2003 | Rectum | I/II/III/IV | 109 |

RAR APR HP |

| 25 | Kyo 2006 [62 | Japan |

Prospective CCT |

1998-2000 | Rectum | I/II/III/IV | 37 |

RAR APR HP |

| 26 | Col 2005 [63] | Turkey |

Retrospective CCT |

1997-2000 | Rectum | NR | 170 |

RAR APR |

| 27 | Hasdemir 2005 [64] | Turkey |

Retrospective CCT |

NR | Rectum U/M/L | I/II/III | 170 |

RAR APR |

| 28 | Matsuoka 2005 [65] | Japan |

Prospective CCT |

1998 - 2003 | Rectum | NR | 57 | RAR |

| 29 | Fujita 2003 [66] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1985-1998 |

Rectum L Anal Canal |

II/III | 246 |

RAR APR |

| 30 | Maeda 2003 [67] | Japan |

Prospective CCT |

1988-1996 | Rectum U/L | NR | 77 |

RAR APR |

| 31 | Watanabe 2002 [7] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1985-1995 | Rectum L | NR | 115 |

RAR APR HP PE |

| 32 | Nagawa 2001 [45] | Japan | RCT | 1993-1995 | Rectum L | NR | 45 |

RAR APR |

| 33 |

Suzuki 1995 [68] |

Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1963-1990 | Rectum U/L | NR | 192 |

RAR APR Others |

| 34 | Moreira 1994 [69] | Japan |

Retrospective CCT |

1981-1991 | Rectum | NR | 178 | NR |

APR abdominoperineal resection, IR intersphincteric resection, LLND lateral lymph node dissection, Non-LLND non-lateral lymph node dissection, PE pelvic exenteration, RAR rectal anterior resection, U upper, M Mid, L lower, ME mesorectal excision

The clinical AJCC staging was reported in 17 studies (50%): II/III stages (9 studies), I/II/III stages (4 studies), I/II/III/IV stages (2 studies), III stage (1 study) and IV stage (1 study). A TME was performed in all patients, and the type of rectal resection was reported in 24 studies (70.6%): anterior resection (23 studies), abdominoperineal resection (20 studies), Hartmann’s procedure (10 studies) and pelvic exenteration (3 studies).

Risk of bias

Seven domains for the potential risk of bias of included RCTs using methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions were analysed [26]. All studies were rated as unclear risk of random sequence generation (selection bias) and five studies for allocation concealment (selection bias). Blinding of participants and personnel and incomplete outcome data were rated as high risk in all included studies. Five studies were rated as low risk of selection bias for selective reporting (reporting bias) and other bias. The ROBINS-I tool was used to evaluate the quality of the comparative studies.

Primary outcomes

Local recurrence at 5 years

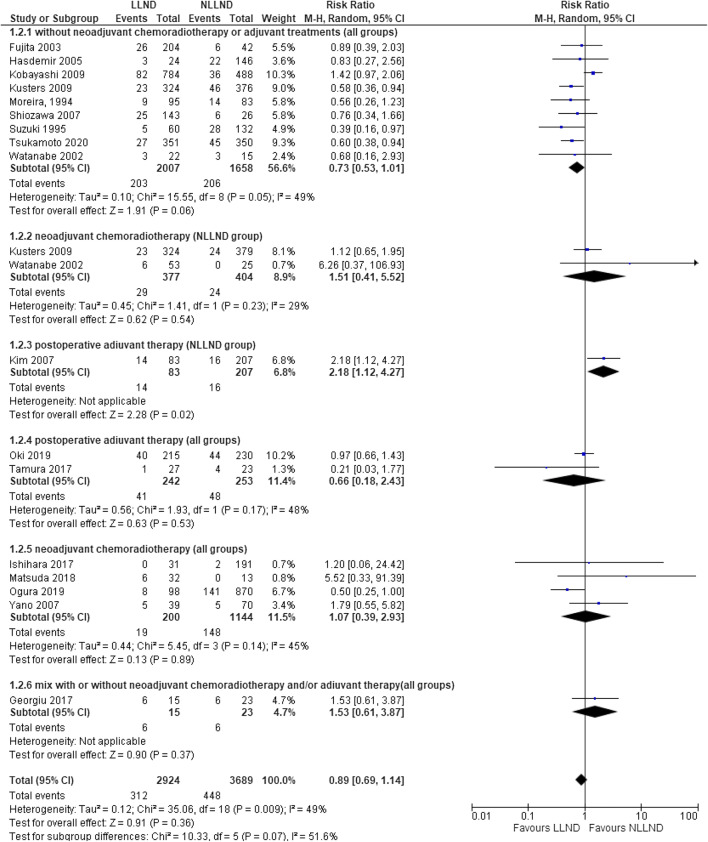

Seventeen studies [7, 17, 42, 45, 46, 48, 49, 52, 53, 57–61, 64, 66, 68, 69] reported local recurrence in 6613 patients (2.924 LLND and 3689 NLLND). The incidence of local recurrence was not statistically different between the overall LLND group (10.7%, 312/2.924) and the overall NLLND group (12.1%, 448/3.689) (RR 0.89, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.14; I2 = 49%, P=0.36) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Forest plot, 5-year local recurrence

In the subgroup analysis of patients who underwent LLND vs NLLND without (Fig. 1 (1.2.1)) or with adjuvant therapy (Fig. 1 (1.2.4)), there was no statistical difference between local recurrence rates in LLND (10.1%) and NLLND (12.4%) group [respectively RR 0.73 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.01) and RR 0.66 (95% CI 0.18 to 2.43)].

In the patients who underwent LLND vs NLLND with neoadjuvant CRT, local recurrence rate was the same in LLND and NLLND (RR 1.51, 95% CI 0.41–5.52) (Fig. 1 (1.2.2))

In all groups that underwent neoadjuvant CRT, there was not a significant difference in local recurrence rate in LLND group (RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.39–2.93) (Fig. 1 (1.2.5)).

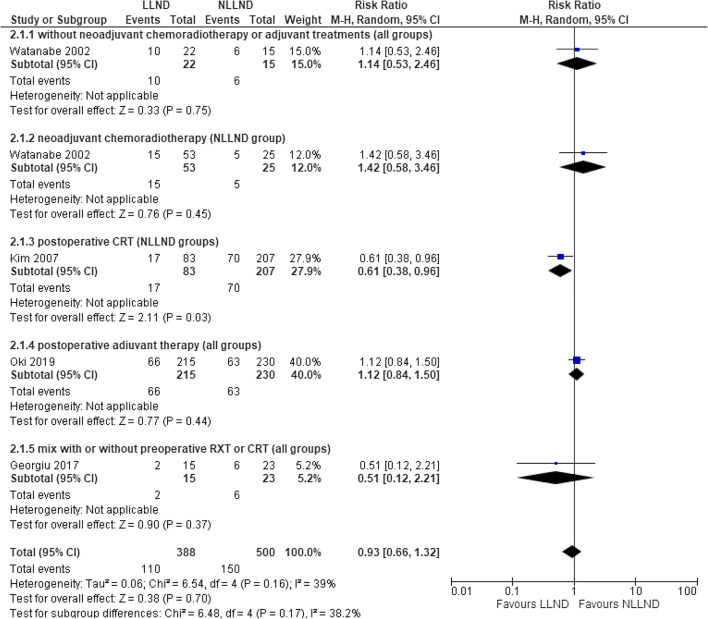

Distant recurrence at 5 years

Four studies [7, 17, 45, 46, 60], including 888 patients (388 LLND and 500 NLLND), reported the rate of distant recurrence.

There was no significant difference in distant recurrence rate between the LLND group (28.6%, 110/388) and the NLLND group (30%, 150/500) (RR 0.93, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.32; I2 = 39%) (Fig. 2). In the subgroup analysis, the results did not show a statistically significant advantage for any group of patients, despite the better results in NLLND with neoadjuvant CRT compared with LLND alone (RR 1.42, 95% CI 0.58–3.46) (Fig. 2 (2.1.2)).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot 5-year distant recurrence

Secondary outcomes

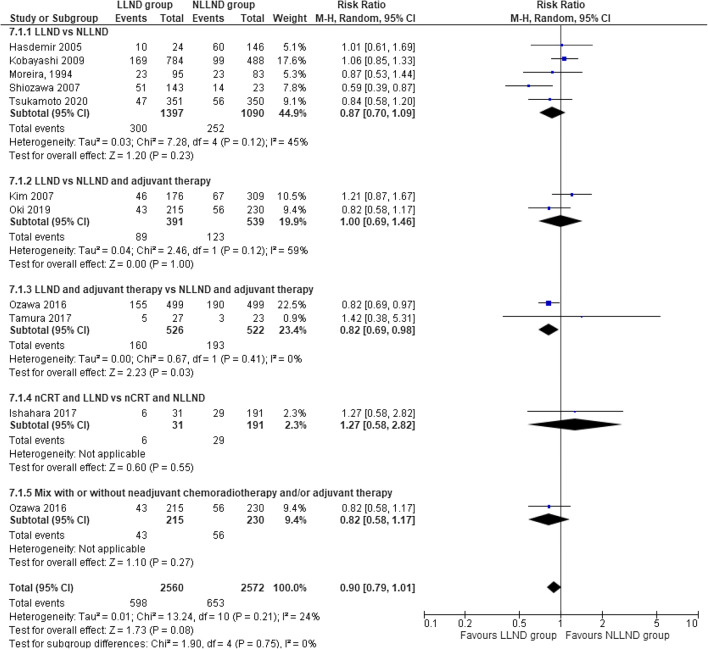

Overall 5-year survival

Ten studies [41, 45, 46, 52, 53, 55, 58–60, 64, 69], including 5132 patients (2560 LLND and 2572 NLLND), reported the rate of this outcome. The overall survival at 5 years was not statistically different between the LLND group (76.6%) and the NLLND group (74.6%), (RR 0.90, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.01; I2 = 17%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot overall survival at 5 years

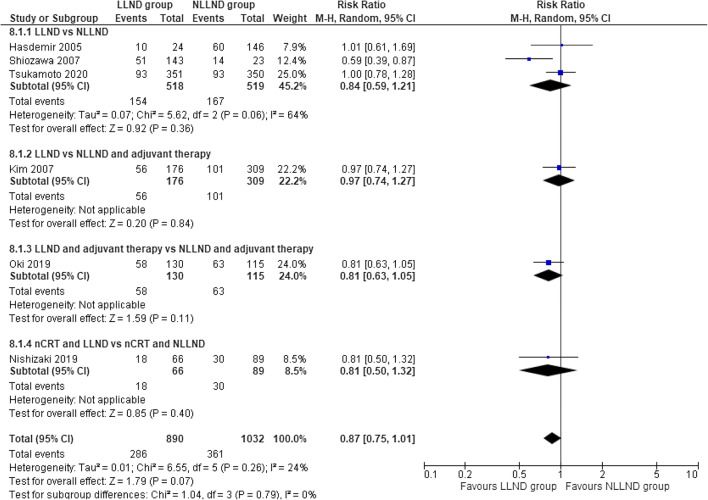

Disease-free 5-year survival

Six studies (41, 45–47, 59, 60, 64), including 1922 patients (913 LLND and 1054 NLLND), reported the rate of this outcome. There was no statistical difference in terms of disease-free survival at 5 years when comparing the LLND group (67.9%) to the NLLND group (65%), (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.01; I2 = 24%) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot disease-free survival at 5 years

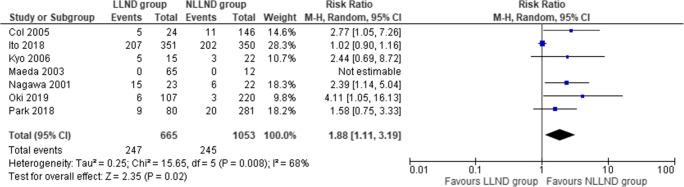

Urinary retention

Seven studies [43, 45, 46, 50, 62, 63, 67], including 1718 patients (665 LLND and 1053 NLLND), reported urinary dysfunction. The incidence of urinary retention was significantly higher in the LLND patients (37%) if compared to the NLLND group (24.4%) (RR 1.88, 95% CI 1.11 to 3.19; I2 = 68%) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Forest plot urinary dysfunction (retention)

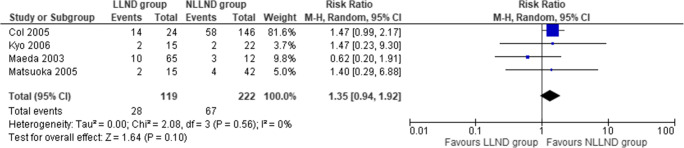

Urinary incontinence

Four studies [62, 63, 65, 67], including 341 patients (119 LLND and 222 NLLND), reported urinary incontinence. The incidence of urinary incontinence was similar between the LLND group (23.5%) and the NLLND group (27.4%) (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.92; I2 = 0%) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Forest plot urinary incontinence

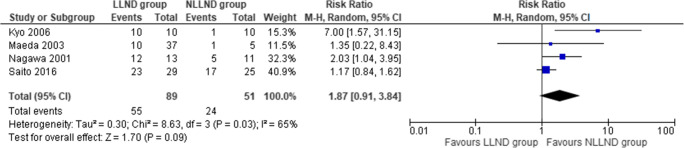

Sexual dysfunction

Four studies [44, 45, 62, 67], including 140 patients (27 LLND and 57 NLLND), reported sexual dysfunction. The incidence of sexual dysfunction was similar between the LLND group (61.7%) and the NLLND group (47%) (RR 1.87, 95% CI 0.91 to 3.84; I2 = 65%) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot sexual dysfunction

Evacuatory dysfunction

Two studies [45, 65], including 84 patients (27 LLND and 57 NLLND), reported evacuatory dysfunction. The incidence of evacuatory dysfunction was similar between the LLND group (62.9%) and the NLLND group (43.9%) (RR 1.57, 95% CI 1.00 to 2.47; I2 = 15%) (SDC 3)(ESM3).

Discussion

Rectal cancer represents the third leading cause of death worldwide with a steadily increasing incidence [70, 71]. The concept of TME, introduced by Heald, has revolutionized the treatment by reducing the local recurrence rates from up to 40% to 4–8% [15, 71]. TME does not include the removal of the lateral pelvic lymph nodes but only those found within the mesorectal fascia and along the course of the mesenteric vessels. The efficacy of the excision of the pelvic lateral lymph nodes is still a controversial topic [72, 73].

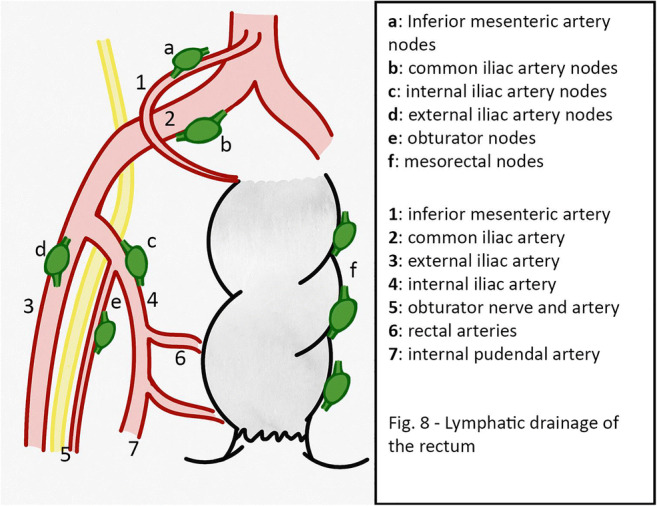

The lymphatic drainage of the rectum, especially for the most distal/lower rectum, through the submucosal plexus, drains in three trunks: the upper branch, which flows into the lymphatic channels of the lower mesenteric vein; the middle branch, draining to the lymph nodes surrounding the internal, external and common iliac vessels; the lower branch draining to the inguinal lymph nodes [15] (Table 2; Fig. 8). These lateral regional lymphatic areas outside of the mesorectum are classified into six regions near the following arteries: the internal pudendal (outside of the pelvic plexus), the internal iliac (proximal to the superior vesical artery), the common iliac, the external iliac, the obturator and the presacral regions. Among these regions, the internal iliac artery and obturator regions have the highest rate of nodal involvement (22-61%) and are called the ‘vulnerable field’ [13, 14].

Table 2.

Lymphatic drainage of the rectum

| Lymphatic drainage | Lymph node group | Tributary Veins |

|---|---|---|

| Upper branch | Rectosigmoid nodes | Lower mesenteric vein |

| Middle branch |

Iliac nodes Sacral nodes |

Common iliac vein Internal Iliac vein External Iliac vein |

| Lower branch |

Inguinal nodes Obturatory nodes External Iliac nodes Pelvic nodes |

Epigastric vein Pudendal vein External iliac vein |

Fig. 8.

Lymphatic drainage of the rectum

The different approaches to the LLND between the East and West stems from the concept that pelvic lateral lymph nodes are considered regional according to Japanese authors and staging systems. The Western world, with the latest AJCC guidelines (AJCC 8th edition), confirms pelvic lateral lymph node stations as remote stations. This is mainly debated in the case of stage II and III low rectal cancer. The involvement of lymph node stations in the iliac and obturator regions varies from 10.6 to 25.5% [15] stage II and III rectal cancer below the peritoneal reflection. More specifically, pelvic extra-regional lymph node involvement is reported in 5.4% of T1 cases, 8.2% for T2, 16.5% for T3 and 37.2% for T4 [58]. For this reason, Japanese surgeons suggest performing TME with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy without neoadjuvant treatment, as they expect that the risk of intrapelvic recurrence decreases by 50%, and 5-year survival improves by 8 to 9% [7, 8].

On the contrary, surgeons of the Western world generally treat rectal cancer with a classical TME and often considering neoadjuvant CRT [74], preserving LLND for patients with clinically suspected lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis [9–11].

The comparison between LLND versus CRT for lateral pelvic lymph nodes mainly concerns the rate of local pelvic recurrence. The only RCT comparing these two surgical techniques is JCOGO212 [41], which compared TME vs. TME and lateral pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients who had no lateral pelvic lymphadenopathy before surgery. The rate of local recurrence decreased from 12.6% in cases of TME alone to 7.4% when TME was associated with lateral lymphadenectomy. A limitation of this study was the choice of not performing preoperative CRT before TME, even when it would have been indicated according to Western guidelines [12, 74]. Long-term follow-up of JCOGO212 confirms the non-inferiority of TME alone compared to TME with pelvic lymphadenectomy in patients without clinically identifiable pelvic lymph node involvement. The study concludes that pelvic lateral lymphadenectomy should only be performed in patients with radiological evidence of lymph node involvement.

Other studies [54] confirm that the risk of pelvic recurrence rises to 19.5% in patients with lateral pelvic lymph nodes of a size more than 7 mm after neoadjuvant therapy. On the other hand, there is little evidence on the true efficacy of bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy for low rectum carcinomas without clinical evidence of bilateral pelvic lymphadenopathy [41]. Although TME alone should not be considered inferior to TME with lateral lymphadenectomy, surgery extended to lateral pelvic lymph nodes reduces the risk of pelvic recurrence, especially in radiologically positive cases.

The main point of the discussion remains the risk of lateral pelvic lymph node metastases even after neoadjuvant CRT. The literature [72] reports a high percentage (up to 30–40%) of pelvic lymph node involvement even after neoadjuvant CRT.

The results from the present analysis confirm that the more radical and invasive surgical approach does not appear to be the safest and optimal way to treat these patients. The comparison between LLND and NLLND groups showed no difference in the rate of local recurrence and distant metastases. The central role in the prevention of local recurrences seems to be the use of neoadjuvant CRT, as the only group with statistically improved results was the non-LLND with neoadjuvant CRT when compared to LLND only. Regarding overall survival, the cumulative analysis also revealed a lack of any advantage of LLND, but the subgroup analysis did show improved overall survival in the group with LLND plus neoadjuvant CRT.

The main concern for the more invasive surgical approach of LLND is additional complications. It is recognized that higher occurrence of urinary, defecatory and sexual dysfunctions is found after LLND [3, 75], despite the introduction of nerve-sparing techniques. In the present analysis, the incidence of urinary retention and incontinence and sexual dysfunctions was directly compared in patients with and without LLND. The only statistically significant difference was the higher incidence of urinary retention in patients undergoing LLND. Another possible confounding factor is the fact that the comparison in most cases was carried out on patients without CRT, which is a procedure also burdened with similar and potentially additional, functional complications. More targeted studies are needed to assess the safety and quality of life following LLND surgery.

An important limitation of the present analysis is the possible bias introduced by the high heterogeneity of the clinical and oncological status of the included patients. Furthermore, our analysis could be expanded and completed by examining other data, such as the number of harvested lymph nodes, additional lymph node metastases detected in the LLND group and differences in functional outcomes between minimally invasive surgeries versus open resections.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that TME with LLND does not offer an oncological advantage over TME without LLND. The advantage of LLND in the pre-neoadjuvant CRT era is lost after the implementation of neoadjuvant CRT. The addition of adjuvant CRT to LLND appears to contribute towards better survival and diminishes the rate of local recurrences. Whilst incurring in heterogeneity of data analysing currently available literature, the evidence would suggest that there is no place for routine LLND in the management of rectal cancer.

These findings reiterate the importance of careful selection of patients for LLND through an improved definition of pathological lymph nodes. Improved imaging techniques to accurately define a reliable cut-off size and describe radiological abnormalities that accurately predict involvement of pelvic lymph nodes are needed. Further studies, preferably prospective, that focus on survival and its association with surgical technique are needed to establish an evidence-based cut-off, which would aid in identifying precise indications for LLND.

Supplementary information

PRISMA flow diagram (DOCX 33 kb)

Excluded studies (DOCX 19 kb)

Forest plot evacuatory dysfunction (DOCX 19 kb)

(DOCX 220 kb)

(PNG 3304 kb)

(DOC 64 kb)

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Ferrara within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

The original online version of this article was revised: One of the co-author name were incorrectly presented. The author should be presented as Salomone Di Saverio instead of Di Saverio Salomone and cited as Di Saverio S.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

8/17/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s00384-021-04010-9

Contributor Information

Alberto Arezzo, Email: alberto.arezzo@unito.it.

Francesco Bagolini, Email: bglfnc@unife.it.

Vito D’Andrea, Email: vito.dandrea@uniroma1.it.

Georgi Popivanov, Email: gerasimpopivanov@rocketmail.com.

Isaac Cheruiyot, Email: isaacbmn@outlook.com.

References

- 1.Silberstein JL, Vickers AJ, Power NE, Parra RO, Coleman JA, Pinochet R, Touijer KA, Scardino PT, Eastham JA, Laudone VP. Pelvic lymph node dissection for patients with elevated risk of lymph node invasion during radical prostatectomy: Comparison of open, laparoscopic and robot-assisted procedures. J Endourol. 2012;26(6):748–753. doi: 10.1089/end.2011.0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wisner KPA, Ahmad S, Holloway RW (2017) Indications and techniques for robotic pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy with sentinel lymph node mapping in gynecologic oncology. Bailliere Tindall Ltd:83–93 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Koch M, Kienle P, Antolovic D, Büchler MW, Weitz J (2005) Is the lateral lymph node compartment relevant? Recent Results Cancer Res:40–45 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Hojo K, Koyama Y, Moriya Y. Lymphatic spread and its prognostic value in patients with rectal cancer. Am J Surg. 1982;144(3):350–354. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(82)90018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koyama Y, Moriya Y, Hojo K. Effects of Extended Systematic Lymphadenectomy for Adenocarcinoma of the Rectum—Significant Improvement of Survival Rate and Decrease of Local Recurrence—. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1984;14(4):623–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moriya Y, Hojo K, Sawada T, Koyama Y. Significance of lateral node dissection for advanced rectal carcinoma at or below the peritoneal reflection. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(4):307–315. doi: 10.1007/BF02553486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Watanabe T, Tsurita G, Muto T, Sawada T, Sunouchi K, Higuchi Y, Komuro Y, Kanazawa T, Iijima T, Miyaki M, Nagawa H. Extended lymphadenectomy and preoperative radiotherapy for lower rectal cancers. Surgery. 2002;132(1):27–33. doi: 10.1067/msy.2002.125357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugihara K, Kobayashi H, Kato T, Mori T, Mochizuki H, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Muto T. Indication and benefit of pelvic sidewall dissection for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49(11):1663–1672. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0714-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson H, Petrelli N, Carlin A, Couture J, Fleshman J, Guillem J, Miedema B, Ota D, Sargent D, National Cancer Institute Expert Panel Guidelines 2000 for colon and rectal cancer surgery. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(8):583–596. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Monson JR, Weiser MR, Buie WD, Chang GJ, Rafferty JF, Buie WD, et al. Practice parameters for the management of rectal cancer (revised) Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56(5):535–550. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e31828cb66c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xynos E, Tekkis P, Gouvas N, Vini L, Chrysou E, Tzardi M, Vassiliou V, Boukovinas I, Agalianos C, Androulakis N, Athanasiadis A, Christodoulou C, Dervenis C, Emmanouilidis C, Georgiou P, Katopodi O, Kountourakis P, Makatsoris T, Papakostas P, Papamichael D, Pechlivanides G, Pentheroudakis G, Pilpilidis I, Sgouros J, Triantopoulou C, Xynogalos S, Karachaliou N, Ziras N, Zoras O, Souglakos J, [the Executive Team on behalf of the Hellenic Society of Medical Oncologists (HeSMO)] Clinical practice guidelines for the surgical treatment of rectal cancer: a consensus statement of the Hellenic Society of Medical Oncologists (HeSMO) Ann Gastroenterol. 2016;29(2):103–126. doi: 10.20524/aog.2016.0003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.You YN, Hardiman KM, Bafford A, Poylin V, Francone TD, Davis K, et al. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Rectal Cancer. Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health); 2020. p. 1191-222 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Canessa CE, Miegge LM, Bado J, Silveri C, Labandera D. Anatomic study of lateral pelvic lymph nodes: implications in the treatment of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004;47(3):297–303. doi: 10.1007/s10350-003-0052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Atef Y, Koedam TW, van Oostendorp SE, Bonjer HJ, Wijsmuller AR, Tuynman JB. Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Metastases in Rectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. World J Surg. 2019;43(12):3198–3206. doi: 10.1007/s00268-019-05135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christou N, Meyer J, Toso C, Ris F, Buchs NC. Lateral lymph node dissection for low rectal cancer: Is it necessary? World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(31):4294–4299. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v25.i31.4294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otero de Pablos J, Mayol J. Controversies in the Management of Lateral Pelvic Lymph Nodes in Patients With Advanced Rectal Cancer: East or West? Frontiers in Surgery. 2020;6(January):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2019.00079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Georgiou PA, Mohammed Ali S, Brown G, Rasheed S, Tekkis PP. Extended lymphadenectomy for locally advanced and recurrent rectal cancer. Int J Color Dis. 2017;32(3):333–340. doi: 10.1007/s00384-016-2711-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng H, Deng Z, Wang ZJ, Zhang W, Su JT. Lateral lymph node dissection with radical surgery versus single radical surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(10):2517–2521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ma P, Yuan Y, Yan P, Chen G, Ma S, Niu X, et al. The efficacy and safety of lateral lymph node dissection for patients with rectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Asian Journal of Surgery. 2020(xxxx) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Hajibandeh S, Hajibandeh S, Matthews J, Palmer L, Maw A. Meta-analysis of survival and functional outcomes after total mesorectal excision with or without lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in rectal cancer surgery. Surgery. 2020;168(3):486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Longchamp G, Meyer J, Christou N, Popeskou S, Roos E, Toso C, Buchs NC, Ris F. Total mesorectal excision with and without lateral lymph node dissection: a systematic review of the literature. Int J Color Dis. 2020;35(7):1183–1192. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03623-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xiang Gao, Cun Wang, Yong-Yang Yu et al. Lateral lymph node dissection reduces local recurrence of locally advanced lower rectal cancer in the absence of preoperative neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis, 21 September 2020, PREPRINT (Version 2) available at Research Square [10.21203/rs.3.rs-42723/v2] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Law BZY, Yusuf Z, Ng YE, Aly EH. Does adding lateral pelvic lymph node dissection to neoadjuvant chemotherapy improve outcomes in low rectal cancer? Int J Color Dis. 2020;35(8):1387–1395. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03656-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ (Online). 2017;358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.JPT Higgins, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane, 2020. Available from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

- 27.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. Bmj. 2016;355:i4919. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods. 2020;n/a(n/a) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical Aspects of the Analysis of Data From Retrospective Studies of Disease. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 1959;22(4):719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Carpenter JR, Schumacher M. Undue reliance on I2 in assessing heterogeneity may mislead. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kontopantelis E, Springate DA, Reeves D. A re-analysis of the Cochrane Library data: the dangers of unobserved heterogeneity in meta-analyses. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Otowa Y, Yamashita K, Kanemitsu K, Sumi Y, Yamamoto M, Kanaji S, Imanishi T, Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Tanaka K, Kakeji Y. Treating patients with advanced rectal cancer and lateral pelvic lymph nodes with preoperative chemoradiotherapy based on pretreatment imaging. Onco Targets Ther. 2015;8:3169–3173. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S89752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong XS, Xu HT, Yu ZW, Liu M, Cu BB, Zhao P, Wang XS. Effect of extended radical resection for rectal cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9(5):970–973. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i5.970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shirouzu K, Ogata Y, Araki Y, Sasatomi T, Nozoe Y, Nakagawa M, et al. Total Mesorectal Excision, Lateral Lymphadenectomy and Autonomic Nerve Preservation for Lower Rectal Cancer: Significance in the Long-term Follow-up Study. Kurume Med J. 2001;48(4):307–319. doi: 10.2739/kurumemedj.48.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Havenga K, Enker WE, Norstein J, Moriya Y, Heald RJ, van Houwelingen HC, van de Velde CJH. Improved survival and local control after total mesorectal excision or D3 lymphadenectomy in the treatment of primary rectal cancer: an international analysis of 1411 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1999;25(4):368–374. doi: 10.1053/ejso.1999.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michelassi F, Block GE. Morbidity and mortality of wide pelvic lymphadenectomy for rectal adenocarcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1992;35(12):1143–1147. doi: 10.1007/BF02251965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hojo K, Sawada T, Moriya Y. An analysis of survival and voiding, sexual function after wide iliopelvic lymphadenectomy in patients with carcinoma of the rectum, compared with conventional lymphadenectomy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1989;32(2):128–133. doi: 10.1007/BF02553825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michelassi F, Block GE, Vannucci L, Montag A, Chappell R. A 5- to 21-year follow-up and analysis of 250 patients with rectal adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 1988;208(3):379–389. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198809000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Enker WE, Pilipshen SJ, Heilweil ML, Stearns MW, Jr, Janov AJ, Hertz RE, et al. En bloc pelvic lymphadenectomy and sphincter preservation in the surgical management of rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 1986;203(4):426–433. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198604000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tsukamoto S, Fujita S, Ota M, Mizusawa J, Shida D, Kanemitsu Y, Ito M, Shiomi A, Komori K, Ohue M, Akazai Y, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Bando H, Tsuchida A, Okamura S, Akagi Y, Takiguchi N, Saida Y, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Long-term follow-up of the randomized trial of mesorectal excision with or without lateral lymph node dissection in rectal cancer (JCOG0212) Br J Surg. 2020;107(5):586–594. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Ito M, Kinugasa Y, Komori K, Ohue M, Ota M, Akazai Y, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Bandou H, Katsumata K, Murata K, Akagi Y, Takiguchi N, Saida Y, Nakamura K, Fukuda H, Akasu T, Moriya Y, Colorectal Cancer Study Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group Mesorectal Excision with or Without Lateral Lymph Node Dissection for Clinical Stage II/III Lower Rectal Cancer (JCOG0212) Ann Surg. 2017;266(2):201–207. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fujita S, Akasu T, Mizusawa J, Saito N, Kinugasa Y, Kanemitsu Y, Ohue M, Fujii S, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Moriya Y, Colorectal Cancer Study Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group Postoperative morbidity and mortality after mesorectal excision with and without lateral lymph node dissection for clinical stage II or stage III lower rectal cancer (JCOG0212): Results from a multicentre, randomised controlled, non-inferiority trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2012;13(6):616–621. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito M, Kobayashi A, Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Kinugasa Y, Komori K, Ohue M, Ota M, Akazai Y, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Akasu T, Moriya Y, Colorectal Cancer Study Group of Japan Clinical Oncology Group Urinary dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery: Results from a randomized trial comparing mesorectal excision with and without lateral lymph node dissection for clinical stage II or III lower rectal cancer (Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study, JCOG0212) Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44(4):463–468. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2018.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saito S, Fujita S, Mizusawa J, Kanemitsu Y, Saito N, Kinugasa Y, Akazai Y, Ota M, Ohue M, Komori K, Shiozawa M, Yamaguchi T, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Male sexual dysfunction after rectal cancer surgery: Results of a randomized trial comparing mesorectal excision with and without lateral lymph node dissection for patients with lower rectal cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study JCOG0212. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42(12):1851–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nagawa H, Muto T, Sunouchi K, Higuchi Y, Tsurita G, Watanabe T, Sawada T. Randomized, controlled trial of lateral node dissection vs. nerve-preserving resection in patients with rectal cancer after preoperative radiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2001;44(9):1274–1280. doi: 10.1007/BF02234784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oki E, Shimokawa M, Ando K, Murata A, Takahashi T, Maeda K, Kusumoto T, Munemoto Y, Nakanishi R, Nakashima Y, Saeki H, Maehara Y. Effect of lateral lymph node dissection for mid and low rectal cancer: An ad-hoc analysis of the ACTS-RC (JFMC35-C1) randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 2019;165(3):586–592. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.08.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nishizaki D, Hida K, Sumii A, Sakai Y, Konishi T, Akagi T, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy with/without lateral lymph node dissection for low rectal cancer: Which patients can benefit? Ann Oncol. 2019;30(October):v205–v20v. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz246.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ogura A, Konishi T, Cunningham C, Garcia-Aguilar J, Iversen H, Toda S, Lee IK, Lee HX, Uehara K, Lee P, Putter H, van de Velde CJH, Beets GL, Rutten HJT, Kusters M, on behalf of the Lateral Node Study Consortium Neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy with total mesorectal excision only is not sufficient to prevent lateral local recurrence in enlarged nodes: Results of the multicenter lateral node study of patients with low ct3/4 rectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(1):33–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matsuda T, Sumi Y, Yamashita K, Hasegawa H, Yamamoto M, Matsuda Y, Kanaji S, Oshikiri T, Nakamura T, Suzuki S, Kakeji Y. Outcomes and prognostic factors of selective lateral pelvic lymph node dissection with preoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer. Int J Color Dis. 2018;33(4):367–374. doi: 10.1007/s00384-018-2974-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Park BK, Lee SJ, Hur BY, Kim MJ, Chan Park S, Chang HJ, Kim DY, Oh JH. Feasibility of selective lateral node dissection based on magnetic resonance imaging in rectal cancer after preoperative chemoradiotherapy. J Surg Res. 2018;232:227–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dev K, Veerenderkumar KV, Krishnamurthy S. Incidence and Predictive Model for Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Metastasis in Lower Rectal Cancer. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2018;9(2):150–156. doi: 10.1007/s13193-017-0719-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishihara S, Kawai K, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Nozawa H, Morikawa T, Watanabe T. Oncological outcomes of lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer treated with preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 2017;60(5):469–476. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamura H, Shimada Y, Kameyama H, Yagi R, Tajima Y, Okamura T, Nakano M, Nakano M, Nagahashi M, Sakata J, Kobayashi T, Kosugi SI, Nogami H, Maruyama S, Takii Y, Wakai T. Prophylactic lateral pelvic lymph node dissection in stage IV low rectal cancer. World Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2017;8(5):412–419. doi: 10.5306/wjco.v8.i5.412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kim HJ, Choi GS, Park JS, Park SY, Cho SH, Lee SJ, Kang BW, Kim JG. Optimal treatment strategies for clinically suspicious lateral pelvic lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8(59):100724–100733. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ozawa H, Kotake K, Hosaka M, Hirata A, Sugihara K. Impact of Lateral Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection on the Survival of Patients with T3 and T4 Low Rectal Cancer. World J Surg. 2016;40(6):1492–1499. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3444-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akiyoshi T, Toda S, Tominaga T, Oba K, Tomizawa K, Hanaoka Y, Nagasaki T, Konishi T, Matoba S, Fukunaga Y, Ueno M, Kuroyanagi H. Prognostic impact of residual lateral lymph node metastasis after neoadjuvant (chemo)radiotherapy in patients with advanced low rectal cancer. BJS open. 2019;3(6):822–829. doi: 10.1002/bjs5.50194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kusters M, Beets GL, Van De Velde CJH, Beets-Tan RGH, Marijnen CAM, Rutten HJT, et al. A comparison between the treatment of low rectal cancer in japan and the netherlands, focusing on the patterns of local recurrence. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):229–235. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318190a664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kobayashi H, Mochizuki H, Kato T, Mori T, Kameoka S, Shirouzu K, Sugihara K. Outcomes of surgery alone for lower rectal cancer with and without pelvic sidewall dissection. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(4):567–576. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a1d994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shiozawa M, Akaike M, Yamada R, Godai T, Yamamoto N, Saito H, Sugimasa Y, Takemiya S, Rino Y, Imada T. Lateral lymph node dissection for lower rectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(76):1066–1070. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim JC, Takahashi K, Yu CS, Kim HC, Kim TW, Ryu MH, Kim JH, Mori T. Comparative outcome between chemoradiotherapy and lateral pelvic lymph node dissection following total mesorectal excision in rectal cancer. Ann Surg. 2007;246(5):754–762. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318070d587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yano H, Saito Y, Takeshita E, Miyake O, Ishizuka N. Prediction of lateral pelvic node involvement in low rectal cancer by conventional computed tomography. Br J Surg. 2007;94(8):1014–1019. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kyo K, Sameshima S, Takahashi M, Furugori T, Sawada T. Impact of autonomic nerve preservation and lateral node dissection on male urogenital function after total mesorectal excision for lower rectal cancer. World J Surg. 2006;30(6):1014–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0050-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Çöl C, Hasdemir O, Yalcin E, Guzel H, Tunc G, Bilgen K, Kucukpinar T. The assessment of urinary function following extended lymph node dissection for colorectal cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2005;31(3):237–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hasdemir O, Cöl C, Yalçin E, Tunç G, Bilgen K, Kuçukpinar T. Local recurrence and survival rates after extended systematic lymph-node dissection for surgical treatment of rectal cancer. Hepatogastroenterology. 2005;52(62):455–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Matsuoka H, Masaki T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Impact of lateral pelvic lymph node dissection on evacuatory and urinary functions following low anterior resection for advanced rectal carcinoma. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2005;390(6):517–522. doi: 10.1007/s00423-005-0577-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fujita S, Yamamoto S, Akasu T, Moriya Y. Lateral pelvic lymph node dissection for advanced lower rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2003;90(12):1580–1585. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Maeda K, Maruta M, Utsumi T, Sato H, Toyama K, Matsuoka H. Bladder and male sexual functions after autonomic nerve-sparing TME with or without lateral node dissection for rectal cancer. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2003;7(1):29–33. doi: 10.1007/s101510300005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Suzuki K, Muto T, Sawada T. Prevention of local recurrence by extended lymphadenectomy for rectal cancer. Surg Today. 1995;25(9):795–801. doi: 10.1007/BF00311455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Moreira LF, Hizuta A, Iwagaki H, Tanaka N, Orita K. Lateral lymph node dissection for rectal carcinoma below the peritoneal reflection. Br J Surg. 1994;81(2):293–296. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800810250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Albandar MH, Cho MS, Bae SU, Kim NK. Surgical management of extra-regional lymph node metastasis in colorectal cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2016;16(5):503–513. doi: 10.1586/14737140.2016.1162718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Oh H-K, Kang S-B, Lee S-M, Lee SY, Ihn MH, Kim D-W, Park JH, Kim YH, Lee KH, Kim JS, Kim JW, Kim JH, Chang TY, Park SC, Sohn DK, Oh JH, Park JW, Ryoo SB, Jeong SY, Park KJ. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy affects the indications for lateral pelvic node dissection in mid/low rectal cancer with clinically suspected lateral node involvement: a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014;21(7):2280–2287. doi: 10.1245/s10434-014-3559-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Williamson JS, Quyn AJ, Sagar PM. Rectal cancer lateral pelvic sidewall lymph nodes: a review of controversies and management. Br J Surg. 2020;107:1562–1569. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Colorectal cancer - NICE guideline [NG151] - Published date: 29 January 2020

- 75.Chan DKH, Tan K-K, Akiyoshi T. Diagnostic and management strategies for lateral pelvic lymph nodes in low rectal cancer—a review of the evidence. Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology. 2019;10(6):1200–1206. doi: 10.21037/jgo.2019.01.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA flow diagram (DOCX 33 kb)

Excluded studies (DOCX 19 kb)

Forest plot evacuatory dysfunction (DOCX 19 kb)

(DOCX 220 kb)

(PNG 3304 kb)

(DOC 64 kb)