Abstract

Background

In medical oncology, palliative care principles and advance care planning are often discussed later in illness, limiting time for conversations to guide goal-concordant care. In pediatric oncology, the frequency, timing and content of communication about palliative care principles and advance care planning remains understudied.

Methods

We audio-recorded serial disease re-evaluation conversations between oncologists, children with advancing cancer and their families across the illness trajectory until death or 24 months from last disease progression. Content analysis was conducted to determine topic frequencies, timing and communication approaches.

Results

One hundred forty one disease re-evaluation discussions were audio-recorded for 17 patient–parent dyads with advancing cancer. From 2400 min of recorded dialogue, 119 min (4.8%) included discussion about palliative care principles or advance care planning. Most of this dialogue occurred after frank disease progression. Content analysis revealed distinct communication approaches for navigating discussions around goals of care, quality of life, comfort and consideration of limiting invasive interventions.

Conclusions

Palliative care principles are discussed infrequently across evolving illness for children with progressive cancer. Communication strategies for navigating these conversations can inform development of educational and clinical interventions to encourage earlier dialogue about palliative care principles and advance care planning for children with high-risk cancer and their families.

Subject terms: Paediatric cancer, Quality of life, Paediatric research, Prognosis

Background

For patients with refractory cancer, communication related to palliative care principles and advance care planning is a fundamental aspect of high quality care, not simply only at the end of life but also across the progressive illness trajectory [1–3]. Within cancer care, important palliative care principles include discussing goals of care, quality of life and early involvement of subspecialty palliative care clinicians. Integration of palliative care principles into cancer care has been shown to promote goal-directed care, improve symptoms, reduce caregiver burden and even extend life in adult cancer patients [4–8]. Similar findings have been demonstrated in pediatric cancer, with integration of palliative care associated with improved communication and anticipatory guidance [9, 10], increased comfort and quality of life for patients [10–13] and caregivers [11] and no evidence of decreased survival [14]. Advance care planning further enables patients and families to align their values and preferences with medical care at the end of life, facilitating death with dignity for cancer patients [15, 16].

Within the field of medical oncology, a growing body of literature explores strategies to improve communication around palliative care principles and advance care planning [3, 17–19]. However, the literature describing communication of these sensitive topics in the context of pediatric oncology remains sparse. Research demonstrates that pediatric cancer patients and their families desire direct, empathic and frequent communication even in the face of advancing illness [20–23], yet numerous challenges exist that hinder communication in this setting [24]. No prior studies have explored the frequency, timing and content of dialogue about palliative care principles and advance care planning for children with progressing cancer and their families.

The U-CHAT (Understanding Communication in Healthcare to Achieve Trust) trial was designed to address this gap in the literature. U-CHAT is a prospective, longitudinal, mixed methods investigation of communication between pediatric oncologists, children and adolescents with high-risk cancer and their families, in which serial disease re-evaluation conversations were recorded across the illness course, with a primary goal of describing communication about prognosis and care for advanced disease. In this sub-analysis, we aimed to (1) determine the frequency and timing of conversations about palliative care principles and advance directive discussions for children with advancing cancer and their families, and (2) describe different communication styles and approaches used to broach and discuss these sensitive topics.

Methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital [U-CHAT (Pro00006473); approval date: 7/12/2016]. We present study methods and findings following the COREQ (COnsolidated Criteria for REporting Qualitative Research) checklist (Supplemental Table 1) [25].

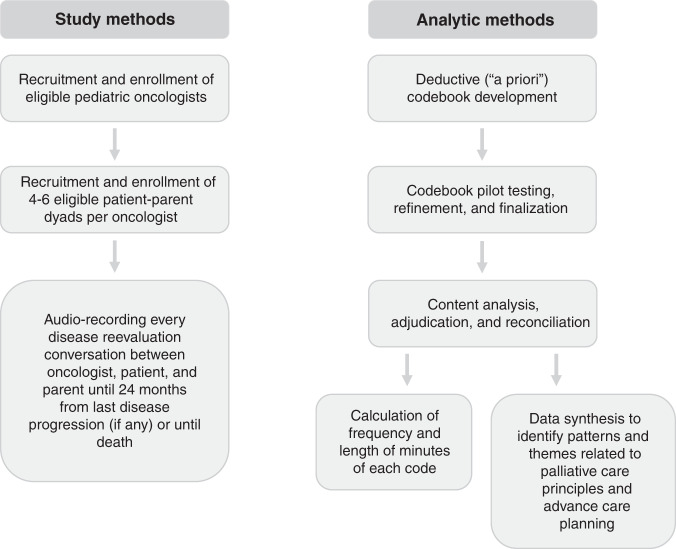

Details related to the study protocol, including specific standardised operating procedures for participant screening, recruitment, enrollment and data collection, have been published previously [26, 27]. Figure 1 presents a flowchart for data collection and analysis methods. Briefly, we enrolled 33 patients with high-risk cancer, their families and their oncology clinicians, with eligibility criteria and recruitment processes described in Table 1. For each patient–parent–oncologist triad, we audio-recorded serial medical conversations occurring in the hospital or clinic or via telephone that corresponded in real-time with discussion of disease re-evaluation imaging or procedures throughout the illness course until the patient’s death or 24 months from disease progression on study, whichever occurred first. For the palliative care principles and advance care planning sub-analysis, we focused on communication occurring within patient–parent dyads that experienced disease progression during the study period. Demographic information was extracted from the electronic medical record using a standardised tool. Recordings of medical dialogue were uploaded into MAXQDA, a mixed methods data analysis software system [28].

Fig. 1. Study methods flowchart.

Figure 1 presents flow of study methods with respect to recruitment, enrollment, data collection and analysis.

Table 1.

Eligibility criteria, recruitment and informed consent processes.

| Protocol domain | Study information |

|---|---|

| Eligibility criteria |

• Eligible oncologists: Primary oncologists providing medical care to solid tumour patients at the institution. • Other eligible providers: Non-primary oncologist healthcare professionals (e.g. fellows, students, nurses, psychosocial providers) who attended a recorded disease re-evaluation conversation for an enrolled study patients (participation limited to attendance during recording). • Eligible patients: Aged 0–30 years, solid tumour diagnosis with survival of ≤50% estimated by their primary oncologist, projected to have ≥2 future timepoints of disease re-evaluations. • Eligible parents/guardians: Legal caregiver of eligible patient, aged ≥18 years, English language proficiency, planned to accompany patient to medical visits. • Others: Family or friends of an enrolled patient–parent dyad who attended a recorded disease re-evaluation conversation (participation limited to attendance during recording). |

| Recruitment and informed consent |

• The Principal Investigator (PI) sent emails to a convenience sample of all eligible primary oncologists at the study site to introduce the study and determine interest in participating; once interest was expressed, the PI met one-on-one with oncologists to describe the study and complete the informed consent process. No oncologists declined participation. • Eligible non-primary oncologist healthcare professionals were introduced to the study by the PI or research team member during clinic or office time preceding a scheduled recording. The study was described and informed consent obtained. • Eligible patient/parent dyads were identified by the research team through review of outpatient clinic schedules and institutional trial lists. The PI reviewed all identified patients to determine those with overall survival reasonably estimated at 50% or less. A member of the research team then asked the patient’s primary oncologist to confirm prognosis by asking: “In your clinical judgement, would you estimate [patient name]’s overall survival at 50% or less?” Permission to approach eligible dyads was requested from the primary oncologist. Patient–parent dyads were then approached by a member of the research team during a clinic visit to determine interest in participation. If interested, the study was described in detail. Dyadic enrollment required agreement from both patient and parent. Patients aged ≥12 years provided assent, and patients aged ≥18 years and parents provided consent. • Eligible family/friends were introduced to the study by the PI or research team member prior to recording the visit, and verbal consent was obtained. |

Codebook development and coding processes

A team of pediatric oncology and palliative medicine clinicians and researchers reviewed the literature related to palliative care and advance care planning in the fields of medical and pediatric oncology. In the absence of a consensus framework for core palliative care and advance care planning concepts in advancing pediatric cancer, we developed and iteratively refined a total of 10 a priori codes to query dialogue on palliative care principles (integration of subspecialty palliative care, goals of care, quality of life, comfort, decreasing toxicities, palliative chemotherapy, palliative radiation) and advance care planning (limitation of invasive interventions, intubation and cardiac resuscitation). Qualitative research analysts (CW, KK, EK) independently pilot-tested the codebook across at least five recordings per participating oncologist, selecting a variety of recordings that included those that were lengthy, nuanced and complex with respect to conversation topic and pacing of dialogue between participants. Variances in application of codes between coders were reviewed and discussed as a team until consensus was reached with respect to saturation of concepts and to ensure consistency in code application. During the pilot phase, iterative revisions made to codebook definitions and examples when needed to improve dependability, confirmability and credibility of independent codes [29]. The full codebook with definitions is presented in Supplemental Table 2. Following codebook finalisation, content analysis was conducted by independent analysts (CW, KK, SV, MG) across all recorded conversations. The research team met weekly to review coding variances with third-party adjudication (EK, JB) as needed to achieve consensus. Consistency in code segmentation was reviewed by separate analysts to ensure a standardised approach (RH, TB, EK). Research team attributes and qualifications are presented in Supplemental Table 3, as per COREQ guidelines.

Analyses

Code frequency, timing and percentage of total recorded dialogue were calculated and reported as descriptive statistics. Dialogue transcripts for select codes were synthesised and reorganised to identify patterns and themes [30] related to the communication styles and strategies used by oncologists to discuss goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of invasive procedures.

Results

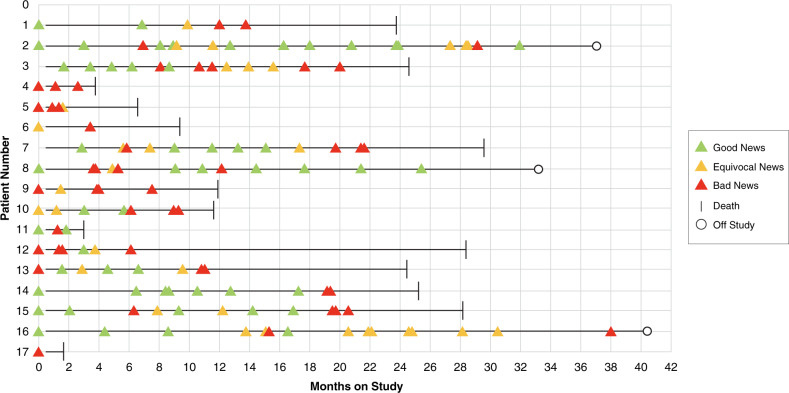

Study findings related to enrollment, retention and capture of longitudinal data have been previously described [26, 27]. Out of 41 eligible dyads approached, 7 (17%) declined to participate in the study (either the patient or the parent); although small numbers, there did not appear to be a difference in race/ethnicity between individuals who chose to participate and those who declined [26]. One patient died unexpectedly prior to beginning data collection, disqualifying that dyad. Within the 33 patient–parent dyads followed longitudinally, 17 patients treated by 6 primary oncologists experienced progressive disease while on study; no participants dropped out. Patient, parent and oncologist demographics are presented in Table 2. In this advancing cancer cohort, 141 disease re-evaluation conversations were recorded across the evolving illness course, comprising ~2400 min of recorded dialogue. The chronological progression of illness with respect to recorded conversations for each patient is shown in Fig. 2. The mean number of recorded conversations was 8.3 [range 1–19], with a mean of 2.9 [range 1–5] timepoints of frank disease progression per patient–parent dyad.

Table 2.

Advancing cancer cohort demographic characteristics.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient (n = 17) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 11 (64.7) |

| Male | 6 (35.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 15 (88.2) |

| Black | 1 (5.9) |

| Mixed | 1 (5.9) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 17 (100) |

| Age at diagnosis | |

| 0–2 years | 2 (11.8) |

| 3–11 years | 6 (35.3) |

| 12–18 years | 7 (41.2) |

| 19+ years | 2 (11.8) |

| Parent (n = 17) | |

| Gender/role | |

| Female/mother | 14 (82.4) |

| Male/father | 3 (17.6) |

| Pediatric Oncologist (n = 6) | |

| Gender | |

| Female | 3 (50) |

| Male | 3 (50) |

| Race | |

| White | 6 (100) |

| Black | 0 (0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) |

| Non-Hispanic | 6 (100) |

| Years in clinical practice | |

| 1–4 years | 2 (33) |

| 5–9 years | 2 (33) |

| 10–19 years | 0 |

| 20+ years | 2 (33) |

Fig. 2. Serial disease re-evaluation conversations recorded per patient with advancing cancer.

Figure 2 presents the illness arc for participating patients, delineating progression of findings across serial disease re-evaluation conversations.

Frequency and timing of palliative care principles and advance care planning dialogue

Across all recordings, 616 codes related to palliative care principles and advance care planning were applied, comprising 1 h and 59 min of dialogue (representing <5% of all recorded conversation). Table 3 presents example quotes representative of each targeted code. Eighty-nine percent of segments (549/616 segments; 107 min of coded dialogue representing 4% of total recorded dialogue) addressed one or more of the palliative care principles listed in the codebook. Advance care planning comprised the remaining 11% of segments (67/616 segments; 11 min of dialogue representing 0.4% of total recorded dialogue). Frequencies and length in minutes of specific codes are detailed in Table 4. Within palliative care principles codes, goals of care conversation comprised nearly one-third of coded segments (32%), with quality of life and focusing on comfort comprising 26% and 17%, respectively. Within advance care planning codes, most discussion involved limitation of invasive procedures (88%), ranging from efforts to minimise blood draws to avoidance of surgical interventions. Dialogue related to limitation of intubation or cardiac resuscitation was coded in 8 segments across serial recordings for all 17 patients with advancing cancer.

Table 3.

Palliative care principles and advance care planning codes and representative examples from recorded dialogue.

| Code | Example |

|---|---|

| Palliative care principles | |

| Palliative care consultation | “We will have the Quality of Life team come here, we are going to optimize her pain meds.” |

| Quality of life | “So, to see you living life a hundred percent, with your arms wipe open, climbing up trees and climbing on granite and really getting out in the middle of the night…Like, holy moly, that is living!” |

| Goals of care | “It’s all about what your goals are, obviously. Our goals are for him to be with us for as long as possible, but the more this comes back and the more treatment he’s had, it makes it very hard for us to make this go away and stay away…So, it’s a matter of what your goals are for him.” |

| Comfort | “As long as she’s not in pain and as long as she’s doing okay, we are going to do our very best to keep her free of pain and as comfortable as possible.” |

| Palliative chemotherapy | “There are probable other oral chemotherapies that we could try, again, the same goal would be to kind of stabilize the disease. We don’t know necessarily the effects of them, or, but it would be more kind of try to prolong things as long as possible.” |

| Limited toxicities | “There’s oral medicines we can try and it doesn’t mean they’re less effective or less powerful, they’re just less toxic.” |

| Palliative radiation | “If you decide that the pain has gotten out of hand, that you would like to consider additional radiation to some sites, that’s what we’re here for.” |

| Advance care planning | |

| Invasive procedures | “If we did a bone marrow [biopsy], maybe she would have disease there or not, I don’t want to put her through a bone marrow, because I don’t want her to hurt after a bone marrow, and given the findings that we have on the scans, it’s irrelevant.” |

| Intubation | “If she were to stop breathing, or, if she were to have a seizure that you cannot control. Do you go to the emergency room? Do you put a tube down her throat to help her breathe?” |

| Cardiac resuscitation | “If her heart stops, if this lesion is there, the heart stops do you start pumping the heart? Do you start giving medicines to bring that back? Or do you just make her as comfortable as possible, and not put her through all of that?” |

Table 4.

Palliative care principles and advance care planning code frequencies and length of time, stratified by disease re-evaluation findings.

| Discussion after improved, stable or equivocal findings | Discussion after findings of frank disease progression | Total recorded discussion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Code | Code frequency (%) | Length of time (min, sec) | Code frequency (%) | Length of time (min, sec) | Code frequency (%) | Length of time (min, sec) |

| Palliative care principles | ||||||

| Palliative care consult | 8 (6.7%) | 1 min, 9 s | 37 (8.6%) | 7 min, 20 s | 45 (8.2%) | 8 min, 29 s |

| Quality of life | 47 (39.2%) | 8 min, 40 s | 95 (22.1%) | 20 min, 24 s | 142 (25.9%) | 29 min, 4 s |

| Goals of care | 26 (21.7%) | 5 min, 33 s | 151 (35.2%) | 31 min, 41 s | 177 (32.3%) | 37 min, 14 s |

| Comfort | 23 (19.2%) | 3 min, 42 s | 71 (16.6%) | 10 min, 39 s | 94 (17.1%) | 14 min, 21 s |

| Palliative chemotherapy | 5 (4.2%) | 1 min, 23 s | 16 (3.7%) | 2 min, 58 s | 21 (3.8%) | 4 min, 21 s |

| Palliative radiation | 3 (2.5%) | 32 s | 25 (5.8%) | 4 min, 54 s | 28 (5.1%) | 5 min, 26 s |

| Limited toxicities | 8 (6.7%) | 1 min, 57 s | 34 (7.9%) | 6 min, 10 s | 42 (7.7%) | 8 min, 7 s |

| Total | 120 (100%) | 22 min, 56 s | 429 (100%) | 84 min, 6 s | 549 (100%) | 107 min, 2 s |

| Advance care planning | ||||||

| Invasive procedures | 6 (100%) | 55 s | 52 (86.7%) | 9 min, 32 s | 58 (87.9%) | 10 min, 27 s |

| Intubation | 0 (0%) | 0 s | 3 (5.0%) | 24 s | 3 (4.5%) | 24 s |

| Cardiac resuscitation | 0 (0%) | 0 s | 5 (8.3%) | 56 s | 5 (7.6%) | 56 s |

| Total | 6 (100%) | 55 s | 60 (100%) | 10 min, 52 s | 66 (100%) | 11 min, 47 s |

When stratified by discussion type, more than three-quarters of codes related to palliative care principles (79%) and nearly all codes related to advance care planning (91%) occurred in discussions that immediately followed frank disease progression (Table 4). Findings were similar for most individual codes, with 76–90% of segments occurring during disease progression conversations. The one exception was for conversation related to quality of life, where one-third of this dialogue occurred during discussions about improving, stable, or equivocal disease and two-thirds in the setting of frank disease progression.

Approaches for communication of palliative care principles and advance care planning

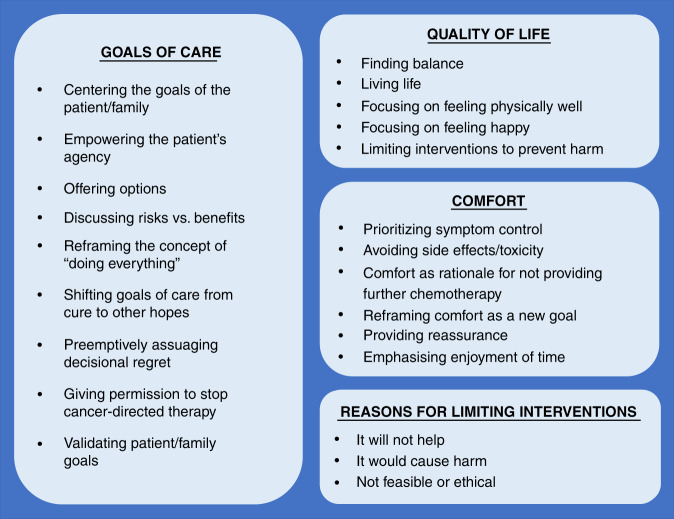

Figure 3 summarises communication approaches that repeatedly emerged from the recorded dialogue for prominent codes: goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of interventions. Additional quotes from the raw data are presented in Table 5.

Fig. 3. Clinician approaches for communication about goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of interventions.

Figure 3 presents core themes identified through content analysis of serial medical dialogue from disease re-evaluation conversations, with respect to communication around goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of interventions.

Table 5.

Representative dialogue highlighting key communication approaches.

| Theme | Examples |

|---|---|

| Goals of care | |

| Centering goals on the patient/family |

• So, it’s all about what your goals are… it’s a matter of what your goals are for him. In terms of treatment and treatment effects, in what you…how you want him to spend the time he has here with us. • We really want you to come up with that, come up with lists. So we can together all make the best decisions for you guys. With you guys, not for you. • The most important [thing] is what [patient] wants… if [patient] wants to do something that lets her be home, but let’s her, still know that we’re continuing to try something. Or whether she would, you know, take a focus and say: I don’t really want to deal with chemo anymore, I would rather just deal with being [patient]. |

| Empowering the patient’s agency |

• You’re in charge. If you don’t want to do it, we need to sit down talk with mom and dad and say, hey. • I don’t want you to do it because I’m offering it to you. I just, I want you to do what you think is best for you…I don’t know what that is, you know, really the one person who does is you. • You know, you—your body and what you have been going through—nobody else knows that but you. And we really follow your lead. • I don’t make decisions by myself, right? Because this all about what you want for your life, right? |

| Offering options |

• Some people would say, ah ok, I like this idea of radiation, right, killing that tumour that’s causing me a lot of pain…other people would say, no, actually I don’t want to do the radiation…and then, other people might say, no I really want to do radiation therapy and then, I want to try really high dose chemotherapy, to try and knock everything out. • At the other end of a spectrum are some patients who are like, you know what, I’ve been doing this cancer thing for a while. I hate how these medicines make me feel…I don’t want to do that, and what I want to do right now is I want to go focus on the things, other things that are important in my life. I still want to, you know, stay in touch with you guys and make sure that I have great quality and all of these things, but I don’t want any therapy. And then, there’s everything in between…A middle ground might be: What I do want, is just possibilities, I do want more therapy because I want to try to make my cancer go away. |

| Discussing risks vs. benefits |

• Because when you think about doing chemotherapy or medicines to treat your cancer you always have to say, what are the risks and benefits, right? So obviously, we always want the benefits to be much better than the risks. • My concern is that if we keep giving you really high dose chemotherapy, that’s not going to help your cancer, right? Because what happens is then you get hospitalised, ok, and then we pick-up big delays and, so all we do for you is make you really, really sick. And then, we’re not able to give you the therapy and your tumours grow. |

| Reframing the concept of “doing everything” |

• We need to make you feeling better and I want you to have a good holiday season, so we’re going to do everything we can to make you feel good. • What I want, we want, is we want you to know that we’re looking at everywhere, right? Everywhere, to try and find what is right [for you]. • The choices are to stay at home and focus on comfort. And focus on making every day the absolute best it can be for [patient]. |

| Shifting goals of care from cure to other hopes |

• It may mean that over time our goals change and that we try to find whatever things the best things are that we can focus on that are specific to [patient] and what she wants. • I think that if we do those things that even if we don’t meet that goal that doing so may give may allow us to meet other goals. • Do we choose differently perhaps with more intent of can we optimise her time that she has and keep her out of the hospital and allow her to do other things? |

| Pre-emptively assuaging decisional regret |

• There’s, there aren’t any wrong decisions that we can all make together. Its just really whatever we all decide. • You know there’s, there’s not necessarily an incorrect path at this point…I think there is only what you guys feel is the best path for [patient] to make sure we’re meeting the goals that we can meet for her. • All the best first-line medicines, right, the best second-line medicines, the best third-line medicines, the best fourth-line medicines, experimental medicines, right? So, we’ve done a lot, and we should have doing all of these things, right? Always with the goal to make your cancer go away. |

| Giving permission to stop cancer-directed therapy |

• You can also say that: I don’t want to do anything…Or you can say, I don’t want to do this right NOW. I just want to take some time and think about it and we can come back and you know, take a break and come back and do things later. And that’s and that’s ok too. • I also recognise that this is a difficult choice for you either way, whether you decide that you want to do this or whether you decide that you wanted to take a break. I wouldn’t fault you either way. • If you at any point decide you do not want to do all those things…if you decide that you would rather…go to Maui and have some fish tacos on the beach; that’s not a bad idea either…ultimately, these are your decisions. |

| Validating patient/family goals |

• Those are all good goals…I won’t be able to tell you which of those is the right goal. Because I don’t think there’s a wrong goal there…I like to get a sense of—what do you think are the most important things for you? • I think that’s a very wise decision on your part. |

| Quality of life | |

| Finding balance |

• My guess is that I think [patient] would still want to do something…but not in the context of having to do something so aggressive that you would end up stuck in the hospital and you know, getting admitted for fever, neutropenia and things like that. • She’s never going to give up, but I think we need to find a balance between what is reasonable and what is not. • That’s where the line comes. We’ve been talking, talking with him about like, wanting to do enough because we know we have a shot. Versus, we want that shot to work, but we also know that there are downsides to- over…burdening that shot with too much radiation. |

| Living life |

• As long as that’s what we are doing; if you can be living while you are taking these medicines and you’re living life, then, then that’s what we should do…If, these medicines and these treatments make that change and you can’t live your life the way you’re wanting to, because they’re making you feel…like crap…If these medicines are not allowing you to live with your arms wide open though, then, we have to have a different plan. Okay? • You deserve to get to go to prom and Disney World and all those kinds of things, and our part of our goals should be to help you do that. • [This treatment] provides some logistical convenience for you, in that it lets you be home and it lets you have a little bit more freedom to be out and about. |

| Focusing on feeling physically well |

• The goal is as much, like, like you feeling as good as you can every second of every day, right? Okay. • If that is that we want to focus on things that are may be not quite so intense and that allow her to you know focus more on feeling good and not being stuck not having as much of a risk of getting stuck in the hospital and side effects things like that we can do that too. • Whether that’s focusing on doing things that allows us to still feel good and allow us to go to school and do the things that we want to do and its just really right now. |

| Focusing on feeling happy | • I’m glad you asked that question because one thing I think that’s really important is you know we always come in and we think about ok what are we going to do to try and go after your cancer but sometimes we miss the bigger picture of thinking about like well what, what’s going to make [patient] most happy and so I’m really glad you asked that question. If there is ever anything that you say hey wait a second I don’t like how this makes me feel or this would be really great for me if we could find out a way that while we’re doing this we could also do something else. I want you to be able to tell us [patient] because how you feel about things and your quality of life is just super super important to us ok. |

| Preventing harm |

• For her at this point would be a very aggressive morbid procedure to and could cause more issues to do a surgery to try to remove it and that’s why it’s better to leave it as it is. • Other stuff is just, would be just random stuff, right. So, like random chemos that aren’t going to work, that just cause side effects; we shouldn’t do that. |

| Comfort | |

| Prioritising symptom control |

• Right now, we need to treat her pain, which is her main thing. • I think that the main things that we would have to concentrate on are pain control, prevention of seizures. • So no one should sit around feeling that. I feel very strongly about that when we have ways that help you. No one should sit around feeling super nauseated when we have other things we can do. |

| Avoiding side effects/toxicity |

• And then we can come up with another plan of something that we can give that is a little less toxic. That perhaps could keep the disease at bay for a while. • I think there’s things we can do that will not affect her marrow that much and her mouth that much and may, may provide a little bit of benefit in prolonging the time to progression. • There’s no reason to add steroids right now, if you give steroids right now, it’s gonna have side effects. |

| Comfort as rationale for not providing further chemotherapy |

• The fact that she’s unable to tolerate chemotherapy would make it very very difficult to try to give anything else, and we believe that we will just add to toxicity and make things much worse. • But it hasn’t done anything and we are just doing her harm by having her counts go down and having to come up here so frequently for transfusions. • I mean today she looks great and… and that’s why I don’t want to add other things that could make her feel uncomfortable. |

| Reframing comfort as a new goal |

• (Parent: No more treatment?) There will be treatment and the treatment will be to make her comfortable and to try to maximise her quality of life. • We are not giving up; we are treating her comfort. |

| Reassuring |

• We can control the pain, we can control the seizures, if she needs steroids, we can do that. • You know obviously our goal is to give her more time and we’re going to keep doing that and keep hoping that…as long as she not feeling [bad] or having issues, we’ll keep working through it. • This regimen does a pretty good job at usually at least making something shrink and then usually when they shrink a little bit, they also start feeling better. Or umm just in making them stable where they’re not growing but there still must be something that they’re doing because they usually have improvement with their symptoms. |

| Enjoying time |

• [We want] for you to be at home as much as possible and for her to enjoy her life at home. • Our main focus right now, in this moment is making sure that you feel as good as humanly possible. • Or, you know, you could even say, you know what, we’ve been doing this a long time and I’m tired, and I just, you know, I’d rather focus on me right now than focus on that. |

| Advance care planning—-reasons to consider limitations on care | |

| It will not help |

• No we can’t and the reason for that is that, that would require a big surgery with this and you still have all this other disease everywhere else and the tumour is just going to come back in another area of your body And then your bone marrow is positive, which means that your tumour is disseminated throughout the body also. So, it doesn’t make sense to go back and cut things out. • I don’t want to do a bone marrow because I don’t know that it’s going to add anything, she may have marrow disease or not, but I don’t know that it’s going to add anything. • My concern is that if we keep giving you really high dose chemotherapy, that’s not going to help your cancer, right? Because what happens is then you get hospitalised, ok, and then we pick-up big delays and, so all we do for you is make you really really sick. And then, we’re not able to give you the therapy and your tumours grow. I don’t want to expose you to a drug that, if I don’t feel it’s going to be effective because we’ve already seen that stress moving far beyond our ability to surgically manage. |

| It would cause harm |

• In the absence of symptoms, [physician] really doesn’t want to do [radiation] because you can make things actually worse by creating some edema. • Giving her chemo at this point might be doing her more harm than any good, especially if we know in the setting that it’s just progressing. • She’s at risk for a bleed, so… you know, if we’re not doing good by giving chemo, potentially bad, we’re doing her harm. |

| Oncologist cannot do it (feasibly or ethically) |

• I think that that is about the extent of that, that we would be able to offer. • We had to cancel the surgery anyway because I was worried about the way you were looking and we were worried about this being a progressive state, in which case, it wouldn’t have been in your best interest to really go forward with that. • When disease has come back rapidly, um, they have not felt that it was in a patient’s best interest to aggressively go after all the legions and do a thoracotomy. • There’s a possibility that she could have disease in her bone marrow, I don’t think, I don’t want to subject her to a bone marrow knowing that she has disease here and here, at this stage. |

Approaches for goals of care communication

We found nine unique approaches for communication around goals of care in the setting of advancing cancer. First, oncologists centered conversations on the goals of the patient and family: “It is our responsibility and one we take very seriously, to come with the best plan, with you as the center.” Second, when developmentally appropriate, oncologists also empowered the patient, emphasising their agency: “We want to make sure that you know…that your voice is just as important as your mom and dad’s…anything we do is your choice, ok?” Third, they offered a range of options, normalising different choices: “Maybe being at home a hundred percent of the time is important to you. Okay great! Let’s figure out how we can make that happen, no problem! Okay, maybe it’s not that important to you, okay great; you’re down here for chemo and then, you’re back and forth.”

Fourth, oncologists discussed risks versus benefits of treatment: “My concern is that if we keep giving you really high dose chemotherapy, that’s not going to help your cancer, right? Because what happens is then you get hospitalized, ok, and then we pick-up big delays and, so all we do for you is make you really, really sick. And then, we’re not able to give you the therapy and your tumors grow.” Fifth, they reframed the concept of “doing everything,” providing reassurance that they would do everything possible to optimise comfort: “We want to be sure that you are offered everything and that you know that we are going to do everything that we need to do for [patient] to be comfortable.” Sixth, they broadened goals of care, creating space to discuss hopes beyond cure: “This is not a conversation that says that we don’t keep fighting, because we always keep fighting. But sometimes the things that we fight for are a little bit different.” Seventh, oncologists pre-emptively assuaged decisional regret, reassuring patients and families that they won’t make an incorrect choice: “Every decision that we make is the right decision for you. Because they’re your decisions. Whatever you decide is never going to be the wrong choice.” Eighth, they offered permission to patients or families to stop cancer-directed therapy, emphasising non-abandonment irrespective of treatment approach: “Sometimes it’s ok to hit the pause button and to take a break. That’s okay. It doesn’t mean that anyone’s going anywhere, we’re not going anywhere.” Ninth, oncologists validated whatever goals patient and families expressed: “To me, that seems like that would be a very reasonable goal and a good goal to have.”

Approaches for quality of life, comfort and advance care planning communication

We identified five distinct approaches used by oncologists for discussing quality of life across advancing illness. Oncologists spoke about finding balance between pursuing treatment: “We are balancing out the most effective treatment, without compromising her quality of life…which means we have to control her symptoms but try to keep this tumor at bay as well.” Oncologists also emphasised the importance of the patient living his/her life: “You deserve to get to go to prom and Disney World and all those kinds of things, and our part of our goals should be to help you do that.” Other communication approaches included focusing on feeling physically well, focusing on feeling happy and preventing harm (Table 5).

When discussing comfort, we found six main communication approaches. The concept of comfort was reframed as a new and valuable goal: “We are not giving up; we are treating her comfort.” Emphasis was placed on enjoyment of time: “[We want] for you to be at home as much as possible and for her to enjoy her life at home.” Oncologists also spoke about prioritising symptom control and avoiding drug toxicity, described comfort as rationale for not pursuing further treatment and provided reassurance (Table 5).

Communication around limiting interventions often evoked four concepts that are similarly related and at times inextricably linked. Oncologists sometimes described treatment or an intervention as simply not feasible or doable: “[Treatment] is not an option, I mean we’ve already maxed out.” Other times, they implicitly referenced their personal ethics (“I don’t want to subject her”) or evoked broader ethics by describing an intervention as “not in a patient’s best interest.” Oncologists also emphasised how an intervention would be ineffective (“it doesn’t make sense” or “I don’t know that it’s going to add anything”). Finally, they described how an intervention would cause harm (describing side effects that would “make things worse”). (Table 5).

Discussion

In the field of medical oncology, the importance of early discussion and integration of palliative care principles and advance care planning is well described [2, 4–8, 15, 16, 31]. In pediatric oncology, however, the frequency, timing and content of these discussions remains understudied. In this paper, we present findings from a prospective, longitudinal investigation of recorded medical dialogue across serial disease re-evaluation conversations with advancing pediatric cancer patients, offering insights into when and how oncologists communicate about palliative care principles and advance care planning across the progressive illness course.

Strikingly, out of 2400 min of recorded disease re-evaluation conversations in this study, fewer than 120 min of discussion centered on palliative care principles or advance care planning dialogue. These data corroborate the medical oncology literature, in which introduction of palliative care and discussion of advance directives are often limited or delayed [32–34]. For children with high-risk cancer, earlier palliative care involvement is associated with earlier documentation of conversations about advance directives [35]; however, this is the first study to assess the frequency of medical dialogue on these important topics across the advancing illness course for children with high-risk cancer.

The infrequency of dialogue related to palliative care principles and advance care planning across serial recordings is particularly notable given the poor prognoses of children in this cohort. To be eligible for enrollment, a patient’s oncologist had to estimate overall survival at 50% or less; all patients in this cohort experienced subsequent disease progression, decreasing their survival odds considerably, and most died during the study period. Notably, most conversation about palliative care principles and advance care planning occurred during discussions that immediately followed disease progression, with relatively few codes found in conversations that followed stable or equivocal scan results. In the setting of an anticipated poor prognosis, opportunities may exist to introduce or explore palliative care principles or advance care planning topics earlier, as opposed to waiting to broach these conversations after disease progression. Prior work from this study suggests that a “seed planting” approach, in which oncologists broach prognosis early and continue to build prognostic disclosure across time may improve prognostic understanding [27]; a similar approach to conversations about palliative care principles and advance care planning may also be useful in the setting of advancing pediatric cancer, although further research is needed to explore this hypothesis.

The relative infrequency of palliative care principles and advance care planning dialogue across recordings likely has multifactorial origins. First, as integration of subspecialty palliative care becomes more prevalent and better integrated within pediatric oncology [36], palliative care principles and advance care planning conversations may be increasingly delegated to subspecialty palliative care teams. Second, pediatric oncologists may avoid or censor communication of distressing information in an effort to avoid fracturing a therapeutic alliance or abrogating parental hope [37, 38]. Yet few pediatric cancer patients and families report negative attitudes towards early integration of palliative care [39], and most families want communication that fully prepares them to understand how their child’s disease will progress [23]. Taken together, these findings suggest that oncologists should encourage discussions about palliative care principles and advance care planning across the advancing pediatric cancer trajectory. Many of these topics, including supporting quality of life and ensuring that personal goals are heard and respected, are important cornerstones of communication across the illness course and can help promote trust and hope for patients and families even in the face of advancing disease [40].

This study also identified unique approaches for oncologist communication related to goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of interventions in the setting of advancing pediatric cancer. These findings have potential for application in clinical practice. When broaching and navigating difficult conversations across an advancing illness course, clinicians may reference these approaches (Fig. 3) to help guide communication choices with intention. For example, in framing conversations about goals of care, clinicians may consider using communication strategies that center or empower the patient or family, reframe the concept of “doing everything,” offer permission to stop treatment, or validate goals. In discussing quality of life, clinicians may contemplate discussing the importance of finding balance, enjoying time or preventing harm. For patients struggling with symptoms, clinicians may engage in conversation around prioritising comfort as a goal. And when navigating discussions about advance care planning, clinicians may consider describing how certain interventions would not help, may cause harm, or are not feasible or ethical to offer. These approaches can serve as a framework to guide education of trainees around difficult communication as well.

These findings also create opportunities for future research exploration. Notably, we did not assess patient or family perspectives on these approaches, and this study was not designed or powered to explore whether specific communication strategies impacted decision-making or outcomes at end of life. Future investigation should engage patients and families in validating and prioritising approaches that they perceive as meaningful for communicating about palliative care principles and advance care planning in the setting of poor prognosis or advancing cancer.

Study limitations include single site design and potential for sampling bias. Patients/parents pursuing cure-directed therapy may be higher at an academic cancer center known for phase I/II trials, which might influence willingness of clinicians to broach palliative care topics. Alternatively, patients/parents who opted to participate in this study may have been more receptive to open communication, including palliative care principles and advance care planning dialogue. This study also was conducted at an institution that subsidises cost of treatment for patients and families; as such, themes around affordability of treatment did not emerge, but may have in other settings. Participants had limited racial and ethnic diversity, which requires prioritisation in future work. A minority of discussions were not recorded due to research logistical/staffing issues (~6.5%) or at the request of the participating patient or parent (~1%), which theoretically could influence data synthesis and interpretation. However, given that only two recordings were missed in the latter context, this is unlikely to impact findings in a meaningful way.

In summary, discussion about palliative care principles and advance care planning occurred infrequently between oncologists, children with advancing cancer and their families during serial disease re-evaluation conversations across the progressing illness course. We identified unique approaches for oncologist communication related to goals of care, quality of life, comfort and limitation of interventions in the setting of advancing pediatric cancer. These findings should inform the development of educational and clinical interventions to encourage earlier integration of dialogue related to palliative care principles and advance care planning for children with high-risk cancer and their families.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We thank Timothy Hammond for his assistance with figure development.

Author contributions

ECK conceptualised and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, carried out the analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and revised the manuscript. CW and MG collected data, coded data, assisted with analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. KK, SV, TB and RH coded data, assisted with analyses and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. MEL critically reviewed the analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript to improve content and presentation of data. JNB conceptualised the study, participated in coding and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. JWM conceptualised the study, critically reviewed the analyses and reviewed and revised the manuscript to improve content and presentation of data. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This work is supported by Dr. Kaye’s Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center and by ALSAC. Additionally, MEL receives salary support from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (K23NS116453).

Data availability

Researchers interested exploring the raw data may reach out to Dr. Erica Kaye/Division of Quality of Life and Palliative Care/Department of Oncology/St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/262 Danny Thomas Place, Mail Stop 260, Memphis, TN 38105/Office: 901-595-8188/Fax: 901-595-9005/Email: erica.kaye@stjude.org. These raw data comprise audio-recordings of serial medical conversations; in the setting of the rarity of advancing pediatric cancer, we believe that a small risk exists for participant identification even following rigorous de-identification of transcripts. Given this risk, we are not planning to share entire raw datasets upfront to all-comers. We will be glad to consider sharing de-identified data on a case-by-case basis with researchers under a data-sharing agreement, as specified by our Institutional Review Board.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital [U-CHAT (Pro00006473); approval date: 7/12/2016]. This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data containing identifiable information are included in this manuscript.

Competing interests

MEL has received compensation for medicolegal work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-021-01512-9.

References

- 1.Gillick MR. Advance care planning. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:7–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp038202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Narang AK, Wright AA, Nicholas LH. Trends in advance care planning in patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:601–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tulsky JA, Beach MC, Butow PN, Hickman SE, Mack JW, Morrison RS, et al. A research agenda for communication between health care professionals and patients living with serious illness. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1361–6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lagman R, Walsh D. Integration of palliative medicine into comprehensive cancer care. Semin Oncol. 2005;32:134–8. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2004.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, Dionne-Odom JN, Ernecoff NC, Hanmer J, et al. Association between palliative care and patient and caregiver outcomes. JAMA. 2016;316:2104–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, Gallagher ER, Admane S, Jackson VA, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmermann C, Swami N, Krzyzanowska M, Hannon B, Leighl N, Oza A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2014;383:1721–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62416-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, Hu M, Wang B, Ortiz JM, et al. Emergency department–initiated palliative care in advanced cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2:591–8. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, Wolfe J. Differences in end-of-life communication for children with advanced cancer who were referred to a palliative care team. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62:1409–13. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, et al. Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:294–300. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groh G, Feddersen B, Führer M, Brandstatter M, Domenico Borasio G, Fuhrer M. Specialized home palliative care for adults and children: differences and similarities. J Palliat Med. 2014;17:803–10. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hays RM, Valentine J, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Villareale N, McKinstry B, et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:716–28. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Dreyfus J, Osenga K, Sencer S, Wolfe J. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2015;18:143–50. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.0285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ullrich CK, Lehmann L, London WB, Guo D, Sridharan M, Koch R, et al. End-of-life care patterns associated with pediatric palliative care among children who underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2016;22:1049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tulsky JA. Beyond advance directives. JAMA. 2005;294:359–65. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silveira MJ, Kim SYH, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villalobos M, Siegle A, Hagelskamp L, Jung C, Thomas M. Communication along milestones in lung cancer patients with advanced disease. Oncol Res Treat. 2019;42:41–46. doi: 10.1159/000496407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomas TH, Jackson VA, Carlson H, Rinaldi S, Sousa A, Hansen A, et al. Communication differences between oncologists and palliative care clinicians: a qualitative analysis of early, integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J Palliat Med. 2019;22:41–49. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2018.0092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Siegle A, Villalobos M, Bossert J, Krug K, Hagelskamp L, Krisam J, et al. The Heidelberg Milestones Communication Approach (MCA) for patients with prognosis <12 months: protocol for a mixed-methods study including a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2018;19:438. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2814-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang TI, Mack JW. Parental distress and desire for information regarding long‐term implications of pediatric cancer treatment. Cancer. 2018;124:4529–37. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mack JW, Fasciano KM, Block SD. Communication about prognosis with adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: information needs, prognostic awareness, and outcomes of disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:1861–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.2128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greenzang KA, Cronin AM, Kang T, Mack JW. Parent understanding of the risk of future limitations secondary to pediatric cancer treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65:e27020. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sisk BA, Kang TI, Mack JW. Prognostic disclosures over time: parental preferences and physician practices. Cancer. 2017;123:4031–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye E, Snaman J, Johnson L, Levine D, Powell B, Love A, et al. Communication with Children with Cancer and their Families throughout the Illness Journey and at the End of Life. In: Wolfe J, Jones BL, Kreicbergs U, Jankovic M Cham, editors. Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology. Switzerland: Springer, 2017.

- 25.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Heal Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Bluebond-Langner M, Baker JN. Longitudinal investigation of prognostic communication: feasibility and acceptability of studying serial disease reevaluation conversations in children with high-risk cancer. Cancer. 2020;126:131–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaye EC, Stall M, Woods C, Velrajan S, Gattas M, Lemmon M, et al. Prognostic communication between oncologists and parents of children with advanced cancer. Pediatrics. 2021;147:e2020044503. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-044503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schönfelder W. CAQDAS and Qualitative Syllogism Logic-NVivo 8 and MAXQDA 10 Compared. Forum Qual Soc Res. 2021. 10.17169/fqs-12.1.1514.

- 29.Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. Eur J Gen Pract. 2018;24:120–4. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications; 1980.

- 31.Dhollander N, De Vleminck A, Deliens L, Van, Belle S, Pardon K. Barriers to the early integration of palliative home care into the disease trajectory of advanced cancer patients: a focus group study with palliative home care teams. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl.) 2019;28:e13024. doi: 10.1111/ecc.13024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Janah A, R. Gauthier L, Morin L, Jean Bousquet P, Le Bihan C, Tuppin P, et al. Access to palliative care for cancer patients between diagnosis and death: a national cohort study. Clin Epidemiol. 2019;11:443–55. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S198499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorensen A, Wentlandt K, Le LW, Swami N, Hannon B, Rodin G, et al. Practices and opinions of specialized palliative care physicians regarding early palliative care in oncology. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:877–85. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Caissie A, Kevork N, Hannon B, Li LW, Zimmerman C. Timing of code status documentation and end-of-life outcomes in patients admitted to an oncology ward. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:375–81. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-1983-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaye EC, Jerkins J, Gushue CA, DeMarsh S, Sykes A, Lu Z, et al. Predictors of late palliative care referral in children with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2018;55:1550–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaye EC, Snaman JM, Baker JN. Pediatric palliative oncology: bridging silos of care through an embedded model. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2740–4. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mack JW, Joffe S. Communicating about prognosis: ethical responsibilities of pediatricians and parents. Pediatrics. 2014;133:S24–30. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3608E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Helft PR. Necessary collusion: prognostic communication with advanced cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3146–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levine DR, Mandrell BN, Sykes A, Pritchard M, Gibson D, Symons HJ, et al. Patients’ and parents’ needs, attitudes, and perceptions about early palliative care integration in Pediatric Oncology. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:1214–20. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mack JW, Wolfe J, Cook EF, Grier HE, Cleary PD, Weeks JC. Hope and prognostic disclosure. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:5636–42. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.6110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Researchers interested exploring the raw data may reach out to Dr. Erica Kaye/Division of Quality of Life and Palliative Care/Department of Oncology/St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital/262 Danny Thomas Place, Mail Stop 260, Memphis, TN 38105/Office: 901-595-8188/Fax: 901-595-9005/Email: erica.kaye@stjude.org. These raw data comprise audio-recordings of serial medical conversations; in the setting of the rarity of advancing pediatric cancer, we believe that a small risk exists for participant identification even following rigorous de-identification of transcripts. Given this risk, we are not planning to share entire raw datasets upfront to all-comers. We will be glad to consider sharing de-identified data on a case-by-case basis with researchers under a data-sharing agreement, as specified by our Institutional Review Board.