Abstract

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) affects babies born to mothers who consume alcohol while pregnant. South Africa has the highest prevalence of FASD in the world. We review the social determinants underpinning FASD in South Africa and add critical insight from an intersectional feminist perspective. We undertook a scoping review, guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews guidelines. Drawing from EBSCOhost and PubMed, 95 articles were screened, with 21 selected for analysis. We used the intersectionality wheel to conceptualize how the social and structural determinants of FASD identified by the literature are interconnected and indicative of broader inequalities shaping the women and children affected. Key intersecting social determinants that facilitate drinking during pregnancy among marginalized populations in South Africa documented in the existing literature include social norms and knowledge around drinking and drinking during pregnancy, alcohol addiction and biological dependence, gender-based violence, inadequate access to contraception and abortion services, trauma and mental health, and moralization and stigma. Most of the studies found were quantitative. From an intersectional perspective, there was limited analysis of how the determinants identified intersect with one another in ways that exacerbate inequalities and how they relate to the broader structural and systemic factors undermining healthy pregnancies. There was also little representation of pregnant women’s own perspectives or discussion about the power dynamics involved. While social determinants are noted in the literature on FASD in South Africa, much more is needed from an intersectionality lens to understand the perspectives of affected women, their social contexts and the nature of the power relations involved. A critical stance towards the victim/active agent dichotomy that often frames women who drink during pregnancy opens up space to understand the nuances needed to support the women involved while also illustrating the contextual barriers to drinking cessation that need to be addressed through holistic approaches.

Keywords: Intersectionality, pregnancy, alcohol, social determinants, South Africa

Key messages.

Key intersecting social determinants that facilitate drinking during pregnancy among marginalized populations in South Africa documented in the existing literature include social norms and knowledge around drinking and drinking during pregnancy, alcohol addiction and biological dependence, gender-based violence, inadequate access to contraception and abortion services, trauma and mental health, and moralization and stigma.

Because of the diverse range of factors that shape the experience of drinking during pregnancy, there is a need for intersectoral collaboration when developing policy responses to address this issue. Isolated interventions are unlikely to be sufficiently impactful, while multi-pronged policies addressing the underlying social determinants of drinking during pregnancy will have beneficial knock-on effects for many other social and health-related problems.

Providing supportive, non-judgemental listening and taking seriously the pain and suffering of women who drink as a result of their harsh environments, as well as their ability to exert agency within the opportunities available to them, are necessary if the emotional, psychological and material challenges women face are to be addressed in constructive and health-enhancing ways for the mother and baby.

Going forward and based on the evidence in this scoping review, health system interventions and policies are re-imagined to address drinking during pregnancy in ways that are innovative, comprehensive, intersectional and compassionate.

Introduction

Foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) affects babies born to mothers who consume alcohol while pregnant. South Africa has an FASD prevalence of between 29 and 290 per 1000 live births, the highest in the world (Olivier et al., 2016). Drinking during pregnancy is a complex issue for all women, shaped by a number of intersecting global, national, historical, commercial, political, legal and social factors. While the social determinants that influence drinking during pregnancy are acknowledged, a thorough engagement with these issues is often missing.

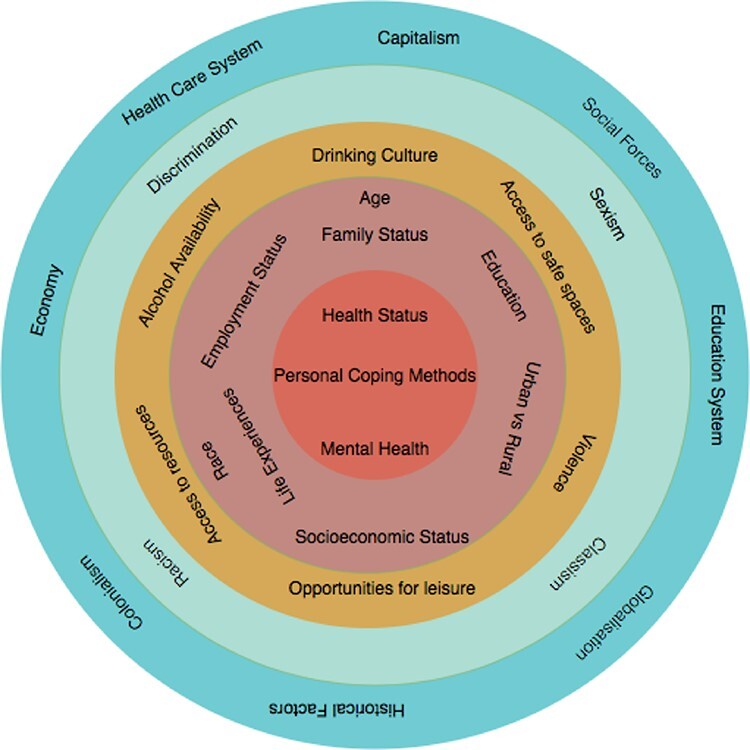

This paper reviews the research on how social and structural determinants play a role in the experiences of women who drink while pregnant in South Africa. We draw on intersectionality research and theory and, in particular, the intersectionality wheel (Simpson, 2009) to provide a conceptualization of the interconnected social determinants, the power relations involved and the constructions of women’s agency in relation to drinking during pregnancy. Intersectionality helps to understand the multidimensional nature of disadvantage and privilege in society, such that these are neither uniform nor static. A central component of the theoretical and analytical approach is the recognition that past and present forms of discrimination and marginalization, such as racism and sexism, are intersecting and compounding social and structural determinants of health (Hankivsky, 2014; Meer and Müller, 2017; Chadwick, 2017).

Taking an intersectionality perspective entails grounding the review in the historical, political and cultural factors that shape drinking during pregnancy in South Africa. While the overall proportion of people who drink in South Africa is low, overall consumption rates are high, because those who do drink engage in episodic heavy drinking. While drinking prevalence is highest among high-income populations, low-income earners on average consume more alcohol, spend more of their income on alcohol and experience a higher burden of alcohol-related harm (Walls et al., 2020). The following paragraphs illustrate from an intersectional viewpoint some of the broader social and structural determinants that play a role in the consumption of alcohol in South Africa. These factors are not specific to pregnant women but still impact them.

Of particular significance is South Africa’s history of racial oppression and the role this played in its drinking culture. The physical availability of alcohol is often cited as an important determinant of how likely someone is to drink and to drink excessively (Pearson et al., 2014). The apartheid system allowed for the payment of (usually coloured) wine farm workers in wine that was often deemed unfit for sale. Some argue that this system (known as the ‘dop’1 system) is responsible for the disproportionately high levels of alcohol consumption among certain communities in the Western Cape province of South Africa, where a large proportion of wine farms are located. Although the ‘dop’ system has been officially prohibited or outlawed for many years, these practices continued as recently as the 1990s (May et al., 2019). They also have enduring legacies that economically, socially and politically disadvantage the communities in which they were carried out.

From the 1950s, illegal taverns or ‘shebeens’ became sites that facilitated the establishment of organized resistance to Apartheid (Parry, 2005 as cited in Bergin, 2013). In this context, consuming alcohol was associated with political activism as well as a respite from spaces where constant scrutiny and discrimination was the norm (Ambler, 2003; Bergin, 2013). However, shebeens also facilitate high levels of alcohol consumption, e.g. by increasing the physical availability of alcohol (by staying open very late and are notably difficult to regulate) [World Health Organization (WHO), 2018]. The physical availability of alcohol is also increased as a result of alcohol’s (especially beer) very low cost in South Africa and increasingly large bottle sizes (Movendi International, 2020).

South Africa’s oppressive history and its corresponding impact on economic inequality also influence alcohol-related behaviours. South Africa ranked the fourth most unequal country globally (Seery et al., 2019). South Africa has been ranked the fourth most unequal country globally (Oxfam, 2019) and the stark differences in income mirror racial divides. Lower socioeconomic status, more frequently experienced by black South Africans, has been associated which a disproportionately high level of alcohol related deaths (Probst et al., 2018; WHO, 2018).

The national enjoyment of sports such as soccer and rugby and the close ties between watching sports and drinking alcohol is also likely to have influenced the strong cultural preference for alcohol consumption as a leisure activity and binge drinking on weekends as a largely accepted social practice. This link between alcohol, sports and leisure is cultivated and reinforced through alcohol marketing and the sponsorship of sports teams by alcohol companies (Parry et al., 2012).

There has also been a purposeful targeting of low-and middle-income countries by global alcohol companies as key markets (Walls et al., 2020). Of particular concern is the specific targeting of young women in Africa by alcohol companies through product design and marketing strategies that are intended to appeal to this demographic (De Bruijn, 2011). While alcohol companies have traditionally argued that alcohol advertising does not encourage drinking and merely allows companies to distinguish their brands from others, this claim is not supported by research which shows an association between alcohol marketing exposure and positive attitudes towards alcohol, earlier drinking initiation (Morgenstern et al., 2011) and higher levels of consumption (Jernigan et al., 2017). The association between alcohol marketing exposure and alcohol use was also noted among South African adolescents (Morojele et al., 2018) and among South African women (Amanuel et al., 2018).

Given this background, in this review we examine what is known from the literature about the social and contextual factors that shape drinking among pregnant women in South Africa. We explain the nature of our scoping review and how we apply an intersectional perspective. We then describe the geographic location and study design of the selected articles, before cataloguing the range of social and contextual factors identified by the articles. We consider the intersections of these factors through the analysis of three clusters: (1) unwanted or unplanned pregnancies, violence and trauma, and mental health, (2) the alcohol environment, alcohol-related social norms and alcohol addiction, and (3) education, access to resources and race. Based on the articles reviewed, we also reflect critically on the framing of drinking during pregnancy drawing on intersectionality theory to review how moralization and stigma are discussed, as well as how we can reframe women who drink during pregnancy.

The review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the research done in this area and provide critical insight into the potential implications for how health systems and policies could best respond to and address this problem in ways that serve women and children. Our intention is to reframe findings, particularly those from the quantitative studies, as more than collections of individual risk factors and to facilitate the depiction of a network of intersecting influences that function to shape what choices are available and preferable to individual women.

Methodology

We chose to undertake a scoping review because it would support the flexibility to explore different types of studies and enable a mapping and synthesis of the available literature, which we felt was important given the relatively nascent application of intersectionality to FASD research in particular and to health policy and systems analysis more broadly. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-Scr) guidelines.

The first stage of the review requires the development of an explicit statement about the research question being addressed, including key elements of the focus of the review. For scoping reviews, the PRISMA-Scr extension says that the key elements of the research can be based on frameworks such as Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome; Setting, Population/Perspective, Intervention, Comparison, Evaluation; PCC: Population, Concept, Context; or other frameworks. We used PCC for the review, given that we did not have an intervention focus.

Statement of research question

What is known from the literature about the social and contextual factors which shape the intersectional experiences of drinking among pregnant women in South Africa?

To source articles to answer this question, the following search terms were run: TI (pregnant OR pregnancy) AND TI (alcohol OR drinking OR drink) AND TX South Africa in EBSCO and PubMed databases. Search results were exported using Endnote and duplicates were removed before articles were assessed for their eligibility for inclusion. Eighty-two articles were collected from EBSCO and 39 articles from PubMed. Once the references were combined and duplicates were removed, the total number of articles was 95.

The first step of the review involved reading the titles and abstracts of all the articles and removing any articles that met any of the exclusion criteria (Table 1). After removing duplicates, empirical research articles, those not based in South Africa and those that did not address the social factors associated with drinking during pregnancy, 26 articles were left. At this point, researchers who worked on related issues were consulted for input and suggestions for additional articles to be included. One article was added bringing the count to 27.

Table 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| In South Africa | Not in South Africa |

| Empirical research | Commentaries and reviews |

| Peer-reviewed journal articles | Grey literature |

| Articles focussed on women who drink during pregnancy | Articles focussed on other populations |

| Identify one or more social determinants that play a role in drinking during pregnancy | Do not cover the social factors that influence or are associated with drinking during pregnancy in the findings/results |

Full-text articles were then reviewed and articles which did not focus on the social determinants of drinking during pregnancy were excluded along with articles which focussed on countries other than South Africa and did not present data on South Africa separately. While going through the full text of the articles the researcher made notes on where the studies were conducted, whether they were qualitative or quantitative and the social determinants which were identified in the findings, as well as reasons for exclusion and possible additional references to explore. In addition, the researcher kept more reflexive notes on the potential implications of some of the study findings, as well as personal perceptions of and reactions to the articles. After this round of screening, and after feedback from peer review, 21 articles remained.

Analysis

The analysis of the reviewed articles involved describing the types of studies included and where they took place. Once this was done a more qualitative thematic grouping of the findings of the articles was undertaken based on intersectionality theory.

Intersectionality theory and its role in the research

The researchers made use of intersectionality theory in two main ways in this research. Firstly, it was used as an epistemological approach (Heard et al., 2019) to the review. This means that intersectionality theory served to frame the researchers understanding of the problem of drinking during pregnancy throughout the process. The researchers adopted an understanding of drinking during pregnancy that framed it as a behavioural choice inseparable from the contextual factors that make up the realities of the women in these studies. In addition, intersectionality also supports an understanding that the social determinants identified in the reviewed articles are interdependent and that exposure to disadvantage in different spheres can have a compounding effect on the experience of drinking during pregnancy (Larson et al., 2016).

Secondly, in order to demonstrate the relevance and applicability of intersectionality theory to public health research, as well as to attempt to provide a comprehensive, yet clear overview of the social determinants of drinking during pregnancy, intersectionality theory was used to guide the analysis of the reviewed articles. This was done by drawing on the intersectionality wheel, which shows how intersecting social characteristics such as age, gender, race and class are determined by layers of power relations that structure their meaning in society. By assigning findings from the reviewed articles to specific segments of the wheel, we were able to visualize how all of these factors may impact individual women. The wheel also helped to contextualize findings within some of the broader ideologies and structures which perpetuate power imbalances and experiences of disadvantage.

Results

This section will first describe the articles selected for review in terms of the location in which the study took place and then the study designs. Following this, key themes from the findings of the studies reviewed will be reported.

Study location

Of the 21 studies, 18 were based on data collected in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The remaining four studies were each based in KwaZulu Natal, Mpumalanga, Gauteng and the Northern Cape provinces.

Study designs

Out of 21 studies, 17 made use of quantitative methods, 3 used qualitative methods (Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Watt et al., 2014, 2016) and 1 was a mixed-methods study (Fletcher et al., 2018). While the quantitative studies provided valuable information on larger samples of women, the qualitative studies deepened the analysis of some of the social and contextual issues surrounding drinking during pregnancy. The qualitative studies found also advanced understandings of some of the mechanisms through which social and contextual determinants were influencing women’s choices and provided insight into their perspectives and experiences.

Some of the quantitative studies also identified determinants that had an unclear relationship to drinking in pregnancy, requiring further research. For example, the family status of participants was identified by five studies as a significant correlate to drinking during pregnancy. This included the marital or relationship status of pregnant women and how many children they had. The findings were not consistent and there could be a number of reasons for the patterns observed, indicating a need for further research.

There were also no studies which were explicitly intersectional in their approach, although there were some which identified interconnected determinants. Despite the identification of significant social factors shaping who was most likely to be affected by the issue of drinking during pregnancy, these factors were seldom framed as issues of power and inequality. The implications discussed in many of the studies appeared to focus on identifying target populations for future interventions and so they were not necessarily intending to gain a deeper understanding of the social context with the purpose of developing interventions aimed at changing these environments.

Study themes

This section will focus on identifying the social determinants which the studies found to have an impact on the likelihood of women drinking during pregnancy or which were found to shape the experience of drinking during pregnancy. We consider the intersections between these factors and explore further how social context, social hierarchies and inequalities play a role in drinking while pregnant. Below, a table represents the themes and how many studies they appeared in (Table 2).

Table 2.

Social determinants addressed by the literature on drinking during pregnancy in South Africa

The diagram below was developed to depict the factors which specifically have an impact on drinking during pregnancy in South Africa to provide a visual representation of the themes identified in the studies reviewed, as well as some of the broader contextual factors identified in the background section, and how they are interrelated (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An intersectionality wheel depicting the factors shaping the experience of drinking during pregnancy

The following section goes into more detail, focusing on some of the themes which came up in the studies reviewed. Not all of the themes listed in the table and wheel are examined, as a choice was made to focus on the themes that were connected with one another or with broader contextual factors to illustrate the intersectional nature of drinking during pregnancy. Themes which present clearer opportunities for intervention were also highlighted as opposed to those with uncertain or more ambiguous pathways to the problem of interest i.e. family status and age (which are not described in more detail below).

Through the analysis of the data, three clusters of interconnected factors were developed which grouped together themes that appeared to link together to shape the experience of drinking during pregnancy. The first cluster includes the interconnected themes of unwanted or unplanned pregnancies, violence and trauma, and mental health. The following cluster included themes relating directly to alcohol, specifically the alcohol environment, alcohol related social norms and alcohol addiction. Lastly, some additional social and contextual factors will be addressed such as education, access to resources and race. Of course, all of these factors relate to one another in various ways but this categorization into clusters illustrates some of these impactful intersections and how together their effects may be reinforcing. From a feminist intersectional perspective it is important to acknowledge that women in South Africa experience discrimination, sexism and oppression on the basis of their sex and gender; however, given the apartheid history and enduring consequences, race is also a significant axis in shaping access to resources and power. This contextual reality is a cross-cutting determinant in the themes presented below.

Unwanted or unplanned pregnancies, violence and trauma, and mental health

Unplanned and unwanted pregnancies

Unplanned and unwanted pregnancies were associated with an increased likelihood of drinking during pregnancy (Watt et al., 2014; Urban et al., 2016; Fletcher et al., 2018). In Watt et al.’s (2014) research on South African women who consumed alcohol during pregnancy, 24 out of the 25 women interviewed had not planned for their pregnancies and almost all of them felt ambivalent towards the foetus and felt no responsibility for the pregnancy and the future baby. Unplanned and unwanted pregnancies are the result of a range of factors that need to be addressed to reduce FASD. Some of these factors include access to contraception and other sexual and reproductive health services, sexual agency and bodily autonomy, gender norms dictating sexual practices, decision-making around contraception and when/if to have children, as well as rape and gender-based violence.

Violence and trauma

Violence was the second most frequently identified theme across the study findings with 12 of the studies mentioning violence and nine showing how gender-based violence acted as a driver of drinking during pregnancy. Child abuse (Choi et al., 2014) and interpersonal violence (Onah, Field et al., 2016; Petersen-Williams et al., 2018) were also found to be significant associated factors. Intimate partner violence was also found to be a predictor of attitudes that are accepting towards drinking alcohol during pregnancy (Fletcher et al., 2018). Related to violence, trauma was also identified to be related to drinking during pregnancy (Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Urban et al., 2016; Fletcher et al., 2018; Myers et al., 2018). Stressful life experiences, fear and childhood trauma were specifically noted as correlated factors.

These findings confirm what has been noted in other research showing a vicious cycle of drinking and violence (Amanuel et al., 2018; Hatcher et al., 2019; Matzopoulos et al., 2020). Drinking is a significant contributor to gender-based violence and rape in particular, and the trauma of rape and the stress of unwanted pregnancies are likely to lead to increased desire to drink. In addition, one of the studies reviewed for this paper found that pregnancy itself predicted higher levels of intimate partner violence (Eaton et al., 2012), exacerbating the above cycle. All of these issues are situated within a patriarchal context characterized by high levels of poverty and inequality influencing and further exacerbating the problem.

Mental health

Linked to the violence and trauma experienced by many women who drink while pregnant, the most common theme emerging from studies was mental health and its role in drinking during pregnancy. Some of the specific issues mentioned include depression (Fletcher et al., 2018; O’Connor et al., 2011; Onah et al., 2016; Wong et al., 2017; Myers et al., 2018), suicidality (Onah et al., 2016), anxiety (Onah et al., 2016), low self-esteem (Morojele et al., 2010), psychological distress (Louw et al., 2011), post-traumatic stress disorder (Peltzer and Pengpid, 2019) and burnout/stress (Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015).

One of the other factors related to mental health was stigma (Wong et al., 2017), specifically human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related stigma. Watt et al.’s (2014) qualitative study provides more detail and colour to the link between mental health and drinking and discusses how drinking during pregnancy is sometimes experienced as self-medicating to manage the trauma and stress resulting from living in violent and/or impoverished circumstances. Consuming alcohol functioned to deaden feelings of sadness, depression, anxiety and fear. The connected issues of violence, trauma and mental health were consistently identified as significant factors related to drinking during pregnancy and so it is crucial that a multi-pronged approach targeting all of these factors be adopted when attempting to address this problem (Hatcher et al., 2019).

Alcohol environment, alcohol-related social norms and alcohol addiction

Culture, social norms and social connections

A number of the studies identified a culture of drinking as an important factor facilitating drinking during pregnancy (Morojele et al., 2010; Louw et al., 2011; Watt et al., 2014, 2016; Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Petersen-Williams et al., 2018). Drinking as an established community norm was related to an increased likelihood of drinking during pregnancy (Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Watt et al., 2016) and drinking during pregnancy specifically was normalized (Watt et al., 2014) making this practice much more difficult to reduce. The most commonly raised factor relating to a culture of drinking and drinking during pregnancy was the drinking habits of partners (Morojele et al., 2010; Louw et al., 2011; Petersen-Williams et al., 2018).

Related to the social norms around drinking and drinking during pregnancy is the link between drinking and social interaction. In some studies, drinking was found to serve as an opportunity for pregnant women to maintain social relationships and access social support (Watt et al., 2014; Fletcher et al., 2018). Avoiding drinking in these situations was experienced as particularly difficult because it was believed to lead to reduced social connection or even to isolation.

In addition, social engagements tend to centre around drinking, partly because drinking is one of few available opportunities for leisure and relaxation (Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Fletcher et al., 2018) and for accessing a relatively safe space (Fletcher et al., 2018) or in a context of limited alternatives. In addition, ready accessibility and affordability of alcohol (Morojele et al., 2010) made drinking an appealing leisure activity. The lack of alternate opportunities for leisure is linked to a range of factors including historical infrastructure and social development inequalities dating back to colonialism and apartheid. Levels of crime and risks of violence may also limit opportunities for outdoor activities.

Social and cultural forces normalizing drinking can be linked back to some of the historical processes described in the Introduction section that highlights how apartheid and the ‘dop’ system cultivated a culture of drinking in South Africa more broadly as well as perpetuating racial oppression. Future interventions must take into account these environmental factors, which extend beyond pregnant women but contribute significantly to their context, when attempting to reduce drinking during pregnancy.

Alcohol addiction and physiological dependence

Within the kinds of contexts described above, becoming physiologically addicted to alcohol either before or during pregnancy is an additional significant factor for consideration. Having a physiological addiction to alcohol was also noted as a significant barrier to cessation (Watt et al., 2014). Substance abuse treatment is a key aspect of addressing alcohol consumption during pregnancy but a specific focus on the gendered nature of alcoholism needs to be incorporated. This must adequately address the problem as it is experienced by women and ensure that substance abuse treatment centres are equipped to deal with the needs of pregnant women.

Education, access to resources and race

Level of education and knowledge about drinking during pregnancy

Only Watt et al., (2014) reported on finding a link between inaccurate knowledge about drinking during pregnancy and an increased likelihood to do so. More broadly, a lack of formal education (Louw et al., 2011) or minimal education (Morojele et al., 2010; Urban et al., 2016) was associated with drinking with pregnancy. This illustrates the contrast between more systemic inequalities such as access to schooling and more narrowly defined problems of having specific knowledge about drinking during pregnancy. The studies show that both of these kinds of educational inadequacies are important and have an impact on the problem, which means that it is necessary to think about education systemically and not only in terms of health information.

Socio-economic status and access to resources

Other systemic inequalities were also highlighted as important contributing factors to drinking during pregnancy. Being unemployed was significantly associated with drinking during pregnancy (Urban et al., 2016; Peltzer and Pengpid, 2019). Access to resources was also found to be linked to drinking during pregnancy (Eaton et al., 2014; Cloete and Ramugondo, 2015; Onah et al., 2016) [with food insecurity cited specifically as a significant factor (May et al., 2005; Eaton et al., 2014; Onah et al., 2016)] and the results of four studies noted socio-economic status as significant. However, these relationships were complex. Some studies found that having better access to resources and a higher socio-economic status was linked to an increased risk of drinking during pregnancy. While other studies found the opposite association.

In Morojele et al.’s (2010) quantitative study, pregnant women living in urban areas were more likely to drink if they were of a higher socio-economic status, but pregnant women in rural areas were more likely to drink if they were impoverished. This article provides a good example of a quantitative study that explores how membership within different social categories intersected to produce differing vulnerabilities in relation to drinking during pregnancy.

While these studies do not identify consistent patterns linking socio-economic status to likelihood of drinking during pregnancy, they do point to the importance of material circumstances when attempting to make sense of the experiences of women who drink while pregnant. The issue of food insecurity is also of particular interest due to the importance of the absence of certain nutrients in the presentation and severity of FASD in children.

Race

Race was reported to be significantly associated with an increased likelihood of pregnant women drinking in four of the quantitative studies (Morojele et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2018; Peltzer and Pengpid, 2019; Petersen-Williams et al., 2018). Women designated as of ‘mixed ancestry’ or ‘coloured’ (Morojele et al., 2010; Myers et al., 2018; Petersen-Williams et al., 2018; Peltzer and Pengpid, 2019) or as ‘white’, as opposed to Black/African (Morojele et al., 2010), were highlighted as at an increased risk of having alcohol-exposed pregnancies. One critique related to this is that these studies tended not to contextualize these findings in their social and historical environments and this runs the risk of (re)producing racist notions that certain racial groupings are inherently more likely to engage in certain behaviours as opposed to acknowledging the contextual factors that disproportionately affect certain groups. South Africa’s history of apartheid’s structural and institutional racism included agricultural sectors, where the institutionalized ‘dop system’ was part of maintaining race inequalities and power relations. Therefore, the interlinked race, gender and class elements of FASD cannot be understood independently of this historical system of racialized inequality, which continues to have significant public health consequences in contemporary South Africa. A deeper analysis of these kinds of findings may help to facilitate a more comprehensive understanding of how racial inequalities are related to the problem of drinking during pregnancy.

Critical reflections on the framing of drinking during pregnancy

Based on the themes identified in the previous section and after gaining a deeper understanding of some of the motivating factors which lead to women drinking while they are pregnant, this section aims to complicate some of the ways in which the issue of drinking during pregnancy is commonly understood and constructed. Drawing on intersectional feminist theories (Larson et al., 2016; Heard et al., 2019), we emphasize a contextualization of experience to critique-dominant constructions of women who drink during pregnancy as mainly irresponsible or uninformed or as victims of their circumstances. Two issues which we would like to pay specific attention to are the notions of stigma and self-care. An intersectional feminist approach foregrounds the importance of the voices of those experiencing multiple, concurrent forms of oppression to understand the depths and relationships among them. While women’s voices were not included in the studies reviewed, it needs to be integrated into how drinking during pregnancy is framed.

Moralization and stigma

FASD is a highly moralized topic which often constructs ‘bad mothers’ and ‘innocent children’ in opposition with one another, sparking public outrage and moralistic judgements. It also leads to the needs of alcohol-consuming mothers and unborn children’s needs being pitted against one another and ranked, with mothers’ needs often valued as less urgent or worthy of public/state support and intervention (Reid et al., 2008). This is a problem for a number of reasons including the psychological and health-related impacts of stigma, but also because of the problematic impacts stigma has on the ability and willingness to access health and psychosocial support services. Women who drink while pregnant often reported revictimization when seeking trauma counselling [felt judged and stigmatized (Myers et al., 2019)], making them unlikely to access these services even when they are available. Decreasing stigma is not only important for changing behaviours but also for accessing accurate data, as stigma is likely to lead to inaccurate self-reports about levels of drinking during pregnancy (Fletcher et al., 2018).

Reframing women who drink during pregnancy—selfish vs self-care

The frequent association between mental health problems and drinking during pregnancy points to an opportunity to review how drinking during pregnancy is framed and to explore how these different framings may influence how the problem is approached. The issue of stigma mentioned above also highlights the need for alternate approaches for managing this issue. In scenarios where women are drinking to manage or cope with negative emotions or to maintain social support networks or even to avoid dangerous or hostile environments, it could be argued that drinking is a form of self-care for these women. Self-care (understood here as all activities attempting to care for or protect one’s body and mind) is generally positively valued among pregnant women in particular, and, as a concept, is something which could be encouraged (in alternate forms). By reframing drinking during pregnancy from being viewed as a selfish or ignorant behaviour to an attempt to protect or care for oneself may also help to reduce stigma towards drinking during pregnancy [which was found to reduce the likelihood of accessing antenatal services (Myers et al., 2018)]. It may facilitate more supportive approaches, focussed on shifting self-care strategies, rather than approaches that shame women for harming their babies.

It may also be useful to attempt to imagine how women come to pursue the habit of drinking while pregnant when exposed to messages that consistently emphasize the negative consequences this has on the health of her child. These kinds of messages could be leading to a defiant response in an attempt to resist efforts to deny or dismiss the significant challenges or suffering she is facing. Through these actions she is reasserting her personhood, her ability to make decisions to protect or take care of herself, to insist that she deserves to have her suffering taken seriously and to attempt to find relief. The women in these studies could be viewed as victims as a result of their experience of violence, trauma, unemployment and poverty. However, they could also be viewed as exerting agency by taking steps to manage their emotions, seeking out social support and safer spaces and resisting a societal disregard of their experiences through their consumption of alcohol. Making sense of women’s choices in this way complicates the victim/active agent dichotomy that can be implicit in understandings of women who drink during pregnancy.

Discussion

The scoping review found that despite the recognition of the importance of social context, no articles applied an intersectional lens to understand or address drinking during pregnancy in South Africa. Most of the studies focussed on the Western Cape and whilst this could be justified in terms of the particularly high levels of FASD in the Western Cape, it also means that available information on the social and contextual factors surrounding drinking during pregnancy in other provinces is limited. The imbalance favouring quantitative studies highlights a need for more qualitative research that attempts to explain some of the patterns found in the quantitative data and to contextualize these findings as well as, crucially, to provide insight into women’s experiences in their own words. Beyond identifying social risk factors that can define target groups, this scoping review also points to the need for empirical studies that ask slightly different research questions, with a broader research aim so that environmental and social determinants can be better understood and addressed from the point of view of marginalized women.

Future research could help to address some of the gaps and imbalances in the studies identified. For example, using phenomenological or case study methods which attempt to provide detailed, nuanced accounts of women’s experiences and which attempt to understand how women make sense of their choices and how drinking is serving them within their contexts would be useful. Research using more participatory approaches may also elicit new kinds of information and may play a role in including women in the process of generating knowledge about themselves. More explicitly, intersectional research which explores how different factors intersect to facilitate drinking during pregnancy or pose as barriers to cessation would also help to provide a more holistic picture of the problem and how to ensure that interventions are responding adequately to the context. Exploring how power and disadvantage may play out within decisions to drink during pregnancy could also help to uncover potential avenues for intervening in ways that disrupt oppressive power systems that make drinking during pregnancy more likely. In addition, it would also be useful to see a closer relationship between quantitative and qualitative studies where quantitative studies attempt to measure the breadth of influence of some of the factors identified in qualitative studies and qualitative studies attempt to unpack and explain some of the relationships identified in quantitative studies.

In re-analysing the findings from studies that did mention social factors underpinning drinking during pregnancy in South Africa, we consider the intersections of these factors through the analysis of three clusters: (1) Unwanted or unplanned pregnancies, violence and trauma, and mental health, (2) alcohol environment, alcohol-related social norms and alcohol addiction and (3) education, access to resources and race. Based on the articles reviewed, we also reflect critically on the framing of drinking during pregnancy drawing on intersectionality theory to review how moralization and stigma are discussed, as well as how we can reframe women who drink during pregnancy.

There is a need to reframe drinking during pregnancy as a problem and to reflect on how pregnant women who drink are implicitly or explicitly constructed within policies and the implications this might have for policy decisions and focus areas. Subtle changes could potentially be facilitated by shifting the focus from exclusively the health and safety of the baby to an incorporation of a comprehensive interest in and acknowledgement of pregnant women’s circumstances. Providing supportive, non-judgemental listening and taking seriously the pain and suffering of women who drink as a result of their harsh environments, as well as their ability to exert agency within the opportunities available to them, are necessary if the emotional, psychological and material challenges women are facing are to be addressed in constructive and health-enhancing ways for the mother and baby.

The findings from the studies reviewed illustrate the need for innovative and comprehensive approaches for addressing drinking during pregnancy. Some of the key factors identified are presented below along with suggestions for how these might be addressed.

In reviewing the social factors that underpin drinking during pregnancy in South Africa from an intersectional lens, the influence of the alcohol industry on young people and women needs to be addressed at a policy level through limiting the marketing of alcoholic beverages and as part of an attempt to shift social norms around drinking (as has been noted by others, e.g. Letsela et al., 2019). In addition, alternative opportunities for socializing and leisure in safe spaces need to be established in collaboration with community members.

Broader implications for policy include the need for intersectoral collaboration, which addresses the intersecting drivers of drinking during pregnancy. The factors which play a role in facilitating drinking during pregnancy extend beyond specific sectors. Limiting the negative impacts of these factors and supporting women in accessing more health-enhancing coping mechanisms and resources require a holistic approach. Policies which do more than acknowledge the importance of social determinants in the context of drinking during pregnancy, but which also propose strategies to practically address them, are needed.

Conclusions

The studies reviewed for this article paint a complex picture of the experience of drinking during pregnancy and highlight a number of neglected social determinants. Some of the most prominently featured themes include the role of violence, trauma and mental health that need to be urgently addressed. They must also be recognized as a core part of FASD and accounted for in all interventions aiming to prevent FASD and reduce drinking during pregnancy. Additional important factors identified from the studies’ findings point to the importance of comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services, as well as substance abuse services that are equipped to deal with the specific problem of alcohol dependence during pregnancy. Because of the diverse range of factors that shape the experience of drinking during pregnancy, there is a need for intersectoral collaboration when developing policy responses to address this issue. Isolated interventions are unlikely to be sufficiently impactful while multi-pronged policies addressing the underlying social determinants of drinking during pregnancy will have beneficial knock-on effects for many other social and health-related problems.

Adopting a critical approach to taken-for-granted assumptions about women who drink during pregnancy, specifically around notions of victimhood and agency, and the implicit messaging underpinning attempts to address FASD is a necessary cognitive shift. This, along with attempting to gain a deeper understanding of women’s experiences, listening to and acknowledging their struggles may help to facilitate new more effective and more compassionate approaches to reducing drinking during pregnancy.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mary Kinney for the supportive role she played by providing advice and resources on the scoping review process.

Endnotes

The word ‘dop’ is the Afrikaans word for ‘drink’.

Contributor Information

Michelle De Jong, School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Road, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, Republic of South Africa.

Asha George, School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Road, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, Republic of South Africa.

Tanya Jacobs, School of Public Health, University of the Western Cape, Robert Sobukwe Road, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, Republic of South Africa.

Data availability statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Funding

This work was supported by the funding received from the South African Research Chair in Health Systems, Complexity and Social Change supported by the South African Research Chair’s Initiative of the Department of Science and Technology and the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa [Grant No. 82769]. Any opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and the NRF does not accept any liability in this regard.

Ethical approval.

Ethical approval for this type of study is not required by our institute.

Conflict of interest statement.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Amanuel H, Morojele N, London L. 2018. The health and social impacts of easy access to alcohol and exposure to alcohol advertisements among women of childbearing age in urban and rural South Africa. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 79: 302–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambler CH. 2003. Southern Africa. In: Blocker JS, Fahey DM, Tyrrell IR (eds). Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History: A Global Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 10–13. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin T. 2013. Regulating Alcohol around the World: Policy Cocktails. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Brittain K, Remien RH, Phillips T. et al. 2017. Factors associated with alcohol use prior to and during pregnancy among HIV-infected pregnant women in Cape Town, South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 173: 69–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chadwick R. 2017. Thinking intersectionally with/through narrative methodologies. Agenda 31: 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Choi KW, Abler LA, Watt MH. et al. 2014. Drinking before and after pregnancy recognition among South African women: the moderating role of traumatic experiences. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 14: 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloete LG, Ramugondo EL. 2015. “I drink”: mothers’ alcohol consumption as both individualised and imposed occupation. South African Journal of Occupational Therapy 45: 34–40. [Google Scholar]

- Culley CL, Ramsey TD, Mugyenyi G. et al. 2013. Alcohol exposure among pregnant women in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Journal of population therapeutics and clinical pharmacology (Journal de la therapeutique des populations et de la pharmacologie clinique) 20: e321–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis EC, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Weichle TW, Rezai R, Tomlinson M. 2017. Patterns of alcohol abuse, depression, and intimate partner violence among township mothers in South Africa over 5 years. AIDS and Behavior 21: 174–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn A. 2011. Alcohol marketing practices in Africa: findings from the Gambia, Ghana, Nigeria and Uganda. Monitoring alcohol marketing in Africa MAMPA project. Brazzaville, Congo: World Health Organization. Africa Regional Office. [Google Scholar]

- Desmond K, Milburn N, Richter L. et al. 2012. Alcohol consumption among HIV-positive pregnant women in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: prevalence and correlates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 120: 113–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ. et al. 2012. Pregnancy, alcohol intake, and intimate partner violence among men and women attending drinking establishments in a Cape Town, South Africa township. Journal of Community Health 37: 208–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Pitpitan EV, Kalichman SC. et al. 2014. Food insecurity and alcohol use among pregnant women at alcohol-serving establishments in South Africa. Prevention Science : The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research 15: 309–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher OV, May PA, Seedat S, Sikkema KJ, Watt MH. 2018. Attitudes toward alcohol use during pregnancy among women recruited from alcohol-serving venues in Cape Town, South Africa: a mixed-methods study. Social Science & Medicine Pergamon 215: 98–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher AM, Gibbs A, McBride RS. et al. 2019. Gendered syndemic of intimate partner violence, alcohol misuse, and HIV risk among peri-urban, heterosexual men in South Africa. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 112637. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankivsky O. 2014. Intersectionality 101 (The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU). [Google Scholar]

- Heard E, Fitzgerald L, Wiggington B, Mutch A. 2019. Applying intersectionality theory in health promotion research and practice. Health Promotion International 35: 1–11. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daz080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jernigan D, Noel J, Landon J, Thornton N, Lobstein T. 2017. Alcohol marketing and youth alcohol consumption: a systematic review of longitudinal studies published since 2008. Addiction 112: 7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson E, George A, Morgan R, Poteat T. 2016. 10 Best resources on… intersectionality with an emphasis on low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning 31: 964–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Letsela L, Weiner R, Gafos M, Fritz K. 2019. Alcohol availability, marketing, and sexual health risk amongst urban and rural youth in South Africa. AIDS Behaviour 23: 175–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louw J, Peltzer K, Matseke G. 2011. Prevalence of alcohol use and associated factors in pregnant antenatal care attendees in Mpumalanga, South Africa. Journal of Psychology in Africa 21: 565–72. [Google Scholar]

- Matzopoulos R, Walls H, Cook S, London L. 2020. South Africa’s COVID-19 alcohol sales ban: the potential for better policy-making. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 9: 486–7. 10.34172/ijhpm.2020.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Brooke LE. et al. 2005. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome in the Western cape province of South Africa: a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health 95: 1190–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP, Marais A-S. et al. 2008. Maternal risk factors for fetal alcohol syndrome and partial fetal alcohol syndrome in South Africa: a third study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 32: 738–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Marais AS, De Vries M. et al. 2019. "The dop system of alcohol distribution is dead, but it’s legacy lives on... ". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 16: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meer T, Müller A. 2017. Considering intersectionality in Africa. Agenda 31: 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern M, Isensee B, Sargent JD, Hanewinkel R. 2011. Attitudes as mediators of the longitudinal association between alcohol advertising and youth drinking. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine 165: 610–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, London L, Olorunju SA, Matjila MJ, Davids AS, Rendall-Mkosi KM. 2010. Predictors of risk of alcohol-exposed pregnancies among women in an urban and a rural area of South Africa. Social Science & Medicine 70: 534–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morojele NK, Lombard C, Harker Burnhams N. et al. 2018. Alcohol marketing and adolescent alcohol consumption: Results from the International Alcohol Control study (South Africa). South African Medical Journal 108: 782–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Movendi International . 2020Africa: big alcohol drives alcohol use with bigger bottles. https://movendi.ngo/news/2020/05/04/africa-big-alcohol-drives-alcohol-use-with-bigger-bottles/, accessed 18 September 2020.

- Myers B, Koen N, Donald KA. et al. 2018. Effect of hazardous alcohol use during pregnancy on growth outcomes at birth: findings from a South African cohort study. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research 42: 369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers B, Carney T, Browne FA. et al. 2019. A trauma-informed substance use and sexual risk reduction intervention for young South African women: a mixed-methods feasibility study. BMJ Open 9: 1–11. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor MJ, Tomlinson M, LeRoux IM, Stewart J, Greco E, Rotheram-Borus MJ. 2011. Predictors of alcohol use prior to pregnancy recognition among township women in Cape Town, South Africa. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 72: 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivier L, Curfs LMG, Viljoen DL. 2016. Fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: prevalence rates in South Africa. South African Medical Journal 106: S103–S6. South African Medical Association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onah MN, Field S, van Heyningen THonikman S. 2016. Predictors of alcohol and other drug use among pregnant women in a peri-urban South African setting. International Journal of Mental Health Systems 10: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry C, Burnhams NH, London L. 2012. A total ban on alcohol advertising: presenting the public health case. South African Medical Journal 102: 602–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peltzer K, Pengpid S. 2019. Maternal alcohol use during pregnancy in a general national population in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychiatry 25: 1–5. doi: 10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v25i0.1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen-Williams P, Mathews C, Jordaan E, Parry CD. 2018. Predictors of alcohol use during pregnancy among women attending midwife obstetric units in the Cape Metropole, South Africa. Substance Use & Misuse 53: 1342–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson AL, Bowie C, Thornton LE. 2014. Is access to alcohol associated with alcohol/substance abuse among people diagnosed with anxiety/mood disorder? Public Health 128: 968–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Probst C, Parry CDH, Wittchen H, Rehm J. 2018. The socioeconomic profile of alcohol-attributable mortality in South Africa: a modelling study. BMC Medicine 16: 1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1080-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid C, Greaves L, Poole N. 2008. Good, bad, thwarted or addicted? Discourses of substance-using mothers. Critical Social Policy 28: 211–34. [Google Scholar]

- Seery E, Okanda J, Lawson M. 2019. “A tale of two continents: fighting inequality in Africa.” Oxfam International. 2 September 2019. https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/africas-three-richest-men-have-more-wealth-poorest-650-million-people-across. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson J. 2009. Everyone Belongs: A Toolkit for Applying Intersectionality. Ottawa, Ontario: Canadian Research Institute for the Advancement of Women. [Google Scholar]

- Urban MF, Olivier L, Louw JG. et al. 2016. Changes in drinking patterns during and after pregnancy among mothers of children with fetal alcohol syndrome: a study in three districts of South Africa. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 168: 13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walls H, Cook S, Matzopoulos R. et al. 2020. Advancing alcohol research in low-income and middle-income countries: a global alcohol environment framework. BMJ Global Health 5: e001958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Eaton LA, Choi KW. et al. 2014. “It’s better for me to drink, at least the stress is going away”: perspectives on alcohol use during pregnancy among South African women attending drinking establishments. Social Science & Medicine 116. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Eaton LA, Dennis AC. et al. 2016. Alcohol use during pregnancy in a South African community: reconciling knowledge, norms, and personal experience. Maternal and Child Health Journal 20: 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt MH, Knettel BA, Choi KW. et al. 2017. Risk for alcohol-exposed pregnancies among women at drinking venues in Cape Town, South Africa. Journal of Studies of Alcohol and Drugs 78: 795–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Myer L, Zerbe A. et al. 2017. Depression, alcohol use, and stigma in younger versus older HIV-infected pregnant women initiating antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. Archives of Women’s Mental Health 20: 149–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2018. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva. https://www.who.int/substance_abuse/publications/global_alcohol_report/en/. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.