Abstract

Background

In human skin, miRNAs have important regulatory roles and are involved in the development, morphogenesis, and maintenance by influencing cell proliferation, differentiation, immune regulation, and wound healing. MiRNAs have been investigated for many years in various skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, as well as malignant tumors. Only during recent times, cosmeceutical use of molecules/natural active ingredients to regulate miRNA expression for significant advances in skin health/care product development was recognized.

Aim

To review miRNAs with the potential to maintain and boost skin health and avoid premature aging by improving barrier function, preventing photoaging, hyperpigmentation, and chronological aging/senescence.

Methods

Most of the cited articles were found through literature search on PubMed. The main search criteria was a keyword “skin” in combination with the following words: miRNA, photoaging, UV, barrier, aging, exposome, acne, wound healing, pigmentation, pollution, and senescence. Most of the articles reviewed for relevancy were published during the past 10 years.

Results

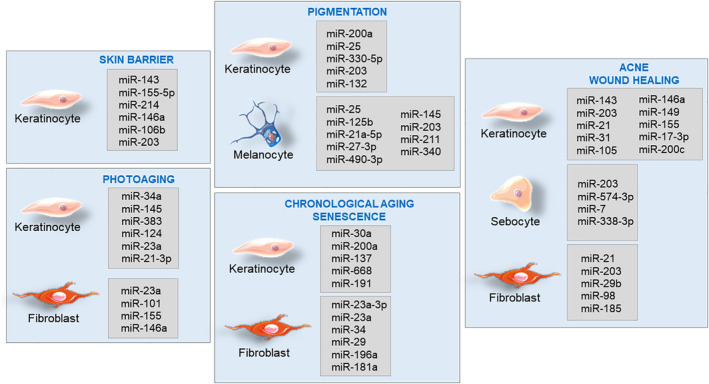

All results are summarized in Figure 1, and they are based on cited references.

Conclusions

Thus, regulating miRNAs expression is a promising approach for novel therapy not only for targeting skin diseases but also for cosmeceutical interventions aiming to boost skin health.

Keywords: cosmetics, microRNA, Skin health

1. INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs, miRs) are a group of short (~22 nucleotides) single‐stranded RNAs, which are highly conserved gene regulators. 1 Although not coding for any protein by themselves, miRNAs can regulate the expression of other protein‐coding gene at post‐transcriptional level. To this end, miRNAs guide the RNA‐induced silencing complex (RISC) to bind to the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the target messenger RNAs (mRNAs) in a sequence‐specific manner, which leads to translation inhibition, and/or degradation of their target mRNAs. 1 , 2 , 3 It has been shown that miRNAs play an important role in almost all the biological and physiological processes, whereas abnormal miRNAs expression and function have been discovered in many diseases. Nowadays, modulation of the disease‐related miRNAs has been shown to be beneficial in several clinical trials, thus making miRNAs a promising candidate for novel therapy. 4

In human skin, miRNAs are involved in the development, morphogenesis, and maintenance by influencing cell proliferation, differentiation, 5 , 6 immune regulation, 7 and wound healing. 8 , 9 The roles of miRNAs have been investigated for more than a decade in various skin disorders such as atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, as well as tumors. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 Unlike the traditional ways of turning on or shut off specific targets, miRNAs exert their biological functions by fine‐tuning protein‐coding genes as mild regulators. 3 Thus, miRNAs may be ideal candidates in targeting to improve skin health and prevent premature aging.

1.1. MiRNAs in skin barrier functions

The skin, especially the epidermal epithelium, is a mechanical, chemical, biological, and immunological barrier protecting the body from the external environment and dehydration. 16 Cornified envelope, tight junctions (TJ), lipids, and microbiome are essential components of the barrier. Ghatak et al demonstrated that miRNAs are fundamental for skin barrier function by using Dicer‐ablated mice. Dicer, an enzyme that cleaves double‐stranded RNA (dsRNA) and pre‐microRNA (pre‐miRNA) into small interfering RNA and microRNA, plays a vital role in re‐establishing the barrier function of the skin post‐wounding via a miRNA‐dependent mechanism. 17

In atopic dermatitis (AD), miR‐143 has been shown to target IL‐13Rα1, thus blocking the IL‐13‐induced dysregulation of filaggrin, loricrin, and involucrin, which are important proteins for the epidermal barrier. 18 Inhibition or overexpression of miR‐155‐5p alters the expression of protein kinase inhibitor α (PKIα) TJ proteins such as occludin and claudins, thymic stromal lymphopoietin TSLP and consequently regulates allergic inflammation. 19 Moreover, overexpression of miR‐214 resulted in decreased epidermal thickness due to reduced keratinocyte proliferation and accelerated terminal differentiation in the epidermis by targeting β‐catenin. In chronic wounds, Roy et al characterized biofilm‐induced miR‐146a and miR‐106b. 20 , 21 These miRs silenced Zonula occludens‐1 (ZO‐1) and Zonula occludens‐2 (ZO‐2) and compromised tight junction function, resulting in leaky skin as measured by TEWL (trans‐epidermal water loss). Intervention strategies aimed at inhibiting biofilm inducible miRNAs may be effective in restoring the barrier function of host skin. 21

Numerous miRNAs are associated with keratinocyte differentiation by extracellular calcium levels. 22 Among them, epidermally expressed MiR‐203 regulates calcium‐induced keratinocyte differentiation by activation of the protein kinase C (PKC) and activator protein 1 (AP‐1) pathway. 23 Interestingly, oleic acid, a naturally occurring fatty acid, also a constituent of sebum, has been shown to upregulate miR‐203 expression to induce keratinocyte differentiation along with involucrin expression by targeting p63. 24 More relevant studies are still needed to map the relationship between regulatory/structural components of epidermal barrier and miRNAs, in order to better understand the cosmeceutical potential of miRNA targeted technologies.

1.2. MiRNAs in photoaging

Ultraviolet radiations like UVA and UVB are the primary cause for human skin aging. Srivastava et al revealed many changes in miRNA expression in the skin exposed to UV. 25 Among them, miR‐34a, miR145, and miR‐383 were the common ones regulated by both chronological aging and photoaging, implying their crucial role in the skin aging processes.

Syed et al 26 showed that miRNA expression was altered by UVB in both keratinocyte and fibroblasts, which could be categorized as a short‐term or a long‐lasting regulation after UV exposure. Comparing the samples from young and elderly human facial skin, 27 miR‐124 was identified as the most upregulated miRNA in the senescent skin. In cultured human keratinocytes, miR‐124 expression was increased by UVB irradiation in a dose‐dependent manner, and overexpression of miR‐124 enhanced the number of SA‐β‐gal positive keratinocytes, revealing a link from UVB to miR‐124 and senescence. 27

Using human primary keratinocytes, Kraemer et al revealed the different changes in miRNA expression by either UVA or UVB irradiation. 28 Among them, miR‐23a was remarkably upregulated by UVA treatment, and RRAS2 (related RAS viral oncogene homolog 2) was identified as its direct target. Also, in the human keratinocyte cell line (HaCaT), miR‐23a was shown to be upregulated by UVB irradiation. MiR‐23b regulated DNA damage repair and apoptosis and protected HaCaT cells from UVB damage via regulation of topoisomerase‐1\caspase7\STK4. 29

Degueurce et al 30 identified miR‐21‐3p as a UV‐ and PPARβ/δ‐activated pro‐inflammatory miRNA in keratinocytes, and in human ex vivo skin, inhibition of miR‐21‐3p reduced UV‐induced inflammation. In human diploid fibroblasts, a genome‐wide screening for UVB‐regulated microRNAs was performed to identify miRNA‐mRNA interaction network mediating UVB‐induced senescence, where a parallel activation of the p53/p21(WAF1) and p16(INK4a)/pRb pathways was observed. 31 Interestingly, among these miRNAs, miR‐101 was further studied, and Ezh2 was identified as its target to modulate UVB‐induced senescence. Using UVA‐irradiated human dermal fibroblasts, miR‐155 was found to directly control c‐Jun expression at the post‐transcriptional level and might function as a protective miRNA in human dermal fibroblasts (HDFs) with a potential for the treatment of photoaging. 32 In another study, UVA‐induced photoaging in fibroblasts resulted in specific patterns of miRNA response, and miR‐146a was able to antagonize UVA‐induced photoaging partially through targeting Smad4. 33 Using miRNA microarrays, it was determined that Entella asiatica (a culinary vegetable and medicinal herb) and troxerutin (a natural flavonoid rutin mainly found in extracts of Sophora japonica) exerted protective effects against UVB‐induced damage by regulating the expression profile of variable miRNAs. 34

Thus, targeting above discussed/referred miRNAs could be an attractive approach to “master regulate” UV‐induced aging processes in the skin.

1.3. MiRNAs in skin pigmentation

Localized melanin/age spots/hyperpigmentation is a critical aging sign in Chinese women. 35 Skin pigmentation is a vital process of defense against UV light that involves highly interactive cellular players: melanocytes, keratinocytes, and fibroblasts. 36 , 37 The cause of hyperpigmentation is the excessive accumulation of melanin pigments in the epidermal basal layer. 38 Melanin pigments are synthesized in the melanosomes, which are specific organelles produced by melanocytes residing at the basal layer of the epidermis, and melanosomes containing melanin pigments are transported to the neighboring keratinocytes. 38

An interesting study documented that exosomes secreted by keratinocytes from donors with different phototypes could control melanocyte pigmentation, which was modulated by UVB. 39 More than 30 miRNAs were reported to be differentially expressed between exosomes from Caucasian and dark skin keratinocytes, including miR‐200a, miR‐132, and miR‐203. Furthermore, miR‐3196 was the only one miRNA upregulated by UVB irradiation in Caucasian keratinocyte exosomes. However, exosomes from UVB‐irradiated Caucasian keratinocytes with miR‐3196 inhibition lost the ability to upregulate melanin production in melanocytes. 39 Later research also suggested that keratinocyte secreted exosomes containing miR‐330‐5p inhibited expression of tyrosinase (TYR), an enzyme controlling melanin production, in melanocytes. 40

Both UV and airborne pollutants are known to induce oxidative stress on the skin. 41 Shi et al verified that oxidative stress could enhance miR‐25 expression in both melanocytes and keratinocytes. 42 By targeting MITF (microphthalmia‐associated transcription factor, a master regulator of melanocyte development, survival, and function), miR‐25 contributed to melanocyte dysfunction, inhibited TYR activity, and decreased melanin content. 36 Besides, miR‐25 inhibited the production and secretion of SCF (stem cell factor) and bFGF (basic fibroblast growth factor) from keratinocytes, thus impairing their paracrine protective effect on the survival of melanocytes under oxidative stress conditions. 36 In addition, multiple microRNAs have been reported to directly target MITF mRNA, such as miR‐137, 43 miR‐218, 44 and miR‐508. 45

MiRNAs also regulate skin pigmentation through other mechanisms. MiR‐21a‐5p positively regulated melanogenesis by targeting SOX5, a potential transcriptional inhibitor of MITF. 46 On the contrary, miR‐27‐3p 47 inhibited melanogenesis by targeting Wnt3a, while miR‐125b reduced melanin content by inhibiting the expression of pigmentation‐related genes such as TYR, TYRP1, DCT, and SH3BP4. 48 Overexpression of miR‐145 resulted in hypopigmentation, as this miRNA targeted the genes implicated in the first step of melanogenesis (SOX9, MITF, TYR, and TYRP1), as well as the genes involved in melanosome transport (MYO5A and RAB27A). 49 Moreover, miR‐203 could reduce melanosome transport and promote melanogenesis by targeting KIF5B and also negatively regulating the CREB1/MITF/Rab27a pathway. 50 Interestingly, miR‐211 regulated melanocyte stem cell maintenance and pigmentation by targeting TGF‐β receptor 2, 51 while the overexpression of miR‐340 led to an increased dendrite formation and melanosome transport. Interestingly, downregulation of miR‐340 inhibited these processes. 52

A good example for epigenetic regulation to hyperpigmentation is achieved by giving an active ingredient of Lansium Domesticum leaf extract, which has 100% natural component, acting on miR‐490‐3p, resulting in lighten pigmented spots on the skin by reducing tyrosinase and melanin levels. 53 These studies reveal an important role of miRNAs in regulating pigmentation processes in the skin and appear as potential targets to prevent undesired hyperpigmentation of aging skin in certain ethnicities.

1.4. MiRNAs in chronological skin aging and senescence

The characteristics of intrinsic or chronological aging include visible signs such as thin and dry skin, fine wrinkles, decreased elasticity, aberrant pigmentation, epidermal and dermal thinning. 54 , 55 , 56 , 57 Besides, the number of senescent cells increases during chronological aging of human skin. 58 , 59 , 60 , 61 , 62 Many miRNAs have been identified as critical regulators in chronological aging in various animal models and cell types. 63 Röck et al 64 have profiled miRNA expression in fibroblasts isolated from young and old human donors and identified miR‐23a‐3p as a miRNA that was highly expressed in both aged and senescent fibroblasts. Furthermore, in the skin of old mice, miR‐23a was found to be increased, which led to down‐regulation of hyaluronic acid by directly targeting hyaluronan synthase 2 (HAS2). One interesting study in HDFs demonstrated that inhibition of miR‐23a stimulated autophagy and rescued UV‐induced premature senescence in fibroblasts. 65 In another study, 66 the miRNA expression between the young and elderly human dermis was compared, where miR‐34 and miR‐29 families were found to be highly expressed in the aged than the young dermis. A computationally constructed miRNA‐target gene network revealed that miR‐34 family, miR‐29 family, and miR‐424 may play a dominant role in the regulatory network involving cell adhesion, collagen synthesis, focal adhesion, insulin, and ErbB signaling pathway. Similarly, altered levels of miR‐34 in aged human dermis have correlated with the phenotype of senescent HDFs in vitro, with reduced expression of COL1A1 and elastin, but with an induced MMP‐1 expression, which might be regulated through interaction with p16. 66 Recently, Srivastava et al performed a microarray analysis of the skin from three age groups of individuals—18‐25 years, 40‐50 years, and over 70 years—and reported that miR‐34a was increased with age. 25

To explore epidermal aging, Muther et al performed miRNA expression profiling in human keratinocytes from young and elderly subjects, and both strands of miR‐30a were found to be overexpressed in aged keratinocytes, human epidermis, and reconstructed skin model mimicking chronological aging. 67 Overexpression of miR‐30a impaired epidermal differentiation and induced apoptosis in keratinocytes, by targeting several key regulators of skin homeostasis, such as LOX (lysyl oxidase), IDH1 (isocitrate dehydrogenase), and AVEN (apoptosis and caspase activation inhibitor). Tinaburri et al discovered a higher level of miR‐200a in elderly human keratinocytes and its role in keratinocyte aging: miR‐200a reduced oxidative DNA repair activity, while inducing several senescence features through upregulation of p16 and IL‐1β. 68 Shin et al identified senescence‐inducing miRNA profile in normal human keratinocytes. Overexpression of miR‐137 or miR‐668 induced senescence in proliferating human keratinocytes with a notable increase in senescence‐associated β‐galactosidase activity, p16INK4A, and p53. 69 Another study reported that miR‐191 triggered keratinocyte senescence by targeting SATB1 and CDK6. 70 One example for modulation in the miRNA expression for cosmetic purpose was demonstrated using Plantago lanceolata extract, which reduced the levels of miR‐29 and miR‐196a, known for exerting negative control on the synthesis of collagens and elastin. Moreover, by decreasing the expression of miR‐30e and miR‐181a, P lanceolata extract helped prolong cell survival and reduced the appearance of senescent phenotypes in fibroblasts. 71

Thus, miRNAs are important regulators of some key processes in the skin during chronological aging/senescence and, therefore, could be considered as a target tool to prevent or delay premature skin aging.

1.5. MiRNAs in acne and acne wound healing

Acne is a chronic inflammatory disease of the pilosebaceous unit. Although the mechanisms of acne vulgaris development are complicated, some key features have been well characterized, including hyperseborrhea (increased sebum production), altered sebum fatty acid composition, follicular hyperkeratinization, epithelial hyperproliferation, systemic and local hormonal imbalance, inflammation, and bacterial colonization by Cutibacterium acnes. Other triggers of acne can be UV radiation, airborne pollution, smoking, dietary factors, and stress. 72 Interestingly, Xia et al showed that Staphylococcus epidermidis inhibited C. acnes‐induced inflammation in the skin via the induction of miR‐143 in both human keratinocytes and a mouse model, and miR‐143 in turn directly targeted TLR2 to inhibit C. acnes‐induced pro‐inflammatory cytokines. 73 Another pathway to target TLR‐2 is via miR‐105. This approach has already been proposed in cosmetogenomics. Briefly, Syringa vulgaris (Lilac) extract had the potential to reduce the expression of TLR2 via miR‐105 upregulation. Reduced number of bacterial binding sites resulted in the induction of less pro‐inflammatory cascade. 74

When acne breaks out, the wound healing process initiates to recover the skin integrity, which includes inflammatory response, cell proliferation, and migration, and also extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling. MiR‐203, a skin‐specific miRNA, promotes keratinocyte differentiation but restricts cell proliferation and migration. 23 , 75 , 76 On the other hand, miR‐21 has both anti‐inflammatory and pro‐migratory roles in keratinocytes via regulating PTEN and also in fibroblasts, as reviewed below. 77 , 78 , 79 MiR‐31 is one of the major miRNAs promoting re‐epithelialization, as it can enhance keratinocyte proliferation, migration, 80 , 81 and differentiation, 82 by regulating epithelial membrane protein 1 (EMP‐1), hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (FIH‐1), Notch signaling, and Ras/MAPK pathway. Schneider et al detected reduced sebaceous lipogenesis in DICER‐impaired human SZ95 sebocyte, implying global miRNA activity is essential for lipid synthesis. The expression of several miRNAs was found to be altered during sebaceous lipogenesis, including upregulation of miR‐203, miR‐574‐3p, and downregulation of miR‐7. Functionally, overexpression of miR‐574‐3p led to a significant increase in lipid synthesis. 83 Interestingly, Liu et al found that miR‐338‐3p has inhibited TNF‐α‐induced lipogenesis in human sebocytes by targeting PREX2a to suppress PI3K/AKT signaling events. 84 Modulation of several miRNAs, such as miR‐146a overexpression, 85 , 86 , 87 , 88 miR‐149 overexpression, 89 and miR‐155 inhibition, 90 , 91 was able to restrict the inflammatory response of keratinocytes and improve wound healing. MiR‐17‐3p promotes keratinocyte proliferation and migration. 92 On the contrary, miR‐200c inhibits keratinocyte migration and delays re‐epithelialization of human ex vivo wounds. 93

Acne scars can be divided into three main types: atrophic, hypertrophic, or keloidal (based on a net loss or gain in collagen), where atrophic acne scars are the most common type. 94 The multi‐player miR‐21 also functions in fibroblasts to promote cell proliferation, migration, and fibrogenesis from normal skin or hypertrophic scars. 95 , 96 , 97 , 98 Interestingly, both downregulation 78 , 99 and upregulation 100 of miR‐21 impair wound healing in vivo by impairing re‐epithelialization and granulation of tissue formation. MiR‐203 is also a multi‐player by decreasing cell proliferation, invasion, and ECM production of keloid fibroblasts by repressing EGR1 and FGF2. 101 Local inhibition of miR‐203 accelerated wound closure and reduced scar formation in vivo associated with an increased re‐epithelialization, skin attachment regeneration, and collagen reassignment. 102

Local delivery of miR‐29b in vivo has improved wound remodeling with reduced contraction, increased collagen III/I ratios, and thus reducing excessive scar formation via suppression of TGF‐β1‐Smad‐CTGF signaling. 103 , 104 MiR‐98 could directly target the COL1A1 gene, reduce viability, and increase apoptosis of fibroblasts. 105 In hypertrophic scar fibroblasts, miR‐185 suppressed cell growth and directly targeted TGF‐β1 and Col‐1 genes. 106 Thus, miRNA‐based potential approaches in anti‐acne and acne scar skin care are an attractive idea and require more research to identify the best miRNA candidates or miRNA targets for therapy.

2. CONCLUSION

Here we summarized miRNAs (Figure 1) that could be useful for combating premature skin aging with a focus on improving skin barrier function, preventing photoaging, hyperpigmentation, and chronological aging/senescence. Thus, miRNAs are promising targets in cosmeceutical research for exclusive skincare product development aiming to improve skin health.

FIGURE 1.

Collection of skin miRs, expressed in different cell types, associated with skin barrier, photoaging, pigmentation, chronological aging, senescence, acne, and wound healing

FUNDING

The study was funded by Oriflame Cosmetics AB.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work. The only data associated with this article are presented in Figure 1. No additional data are associated with this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Ia Khmaladze

Supervision: Ia Khmaladze

Writing: Xi Li, Sakthi Ponandai‐Srinivasan, Kutty Selva Nandakumar, Ia Khmaladze

Review & Editing: Xi Li, Sakthi Ponandai‐Srinivasan, Kutty Selva Nandakumar, Susanne Fabre, Ning Xu Landén, Alain Mavon, Ia Khmaladze

TRANSPARENCY STATEMENT

The corresponding author confirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported.

Li X, Ponandai‐Srinivasan S, Nandakumar KS, et al. Targeting microRNA for improved skin health. Health Sci Rep. 2021;4:e374. doi: 10.1002/hsr2.374

Funding information Oriflame Cosmetics AB

REFERENCES

- 1. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281‐297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350‐355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215‐233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rooij E, Kauppinen S. Development of microRNA therapeutics is coming of age. EMBO Mol Med. 2014;6:851‐864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ning MS, Andl T. Control by a hair's breadth: the role of microRNAs in the skin. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2013;70:1149‐1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Horsburgh S, Fullard N, Roger M, et al. MicroRNAs in the skin: role in development, homoeostasis and regeneration. Clin Sci. 2017;131:1923‐1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sonkoly E, Ståhle M, Pivarcsi A. MicroRNAs: novel regulators in skin inflammation. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33:312‐315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Herter EK, Xu Landén N. Non‐coding RNAs: new players in skin wound healing. Adv Wound Care. 2017;6:93‐107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fahs F, Bi X, Yu FS, Zhou L, Mi QS. New insights into microRNAs in skin wound healing. IUBMB Life. 2015;67:889‐896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Singhvi G, Manchanda P, Krishna Rapalli V, Kumar Dubey S, Gupta G, Dua K. MicroRNAs as biological regulators in skin disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:996‐1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Rozalski M, Rudnicka L, Samochocki Z. MiRNA in atopic dermatitis. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016;33:157‐162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hawkes JE, Nguyen GH, Fujita M, et al. microRNAs in psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:365‐371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen L, Li J, Li Q, et al. Non‐coding RNAs: the new insight on hypertrophic scar. J Cell Biochem. 2017;118:1965‐1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. García‐Sancha N, Corchado‐Cobos R, Pérez‐Losada J, Cañueto J. MicroRNA dysregulation in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:2181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ross CL, Kaushik S, Valdes‐Rodriguez R, Anvekar R. MicroRNAs in cutaneous melanoma: role as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233:5133‐5141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Madison KC. Barrier function of the skin: “La raison d'être” of the epidermis. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;121:231‐241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ghatak S, Chan YC, Khanna S, et al. Barrier function of the repaired skin is disrupted following arrest of dicer in keratinocytes. Mol Ther. 2015;23:1201‐1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zeng YP, Nguyen GH, Jin HZ. MicroRNA‐143 inhibits IL‐13‐induced dysregulation of the epidermal barrier‐related proteins in skin keratinocytes via targeting to IL‐13Rα1. Mol Cell Biochem. 2016;416:63‐70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang X, Chen Y, Yuan W, et al. MicroRNA‐155‐5p is a key regulator of allergic inflammation, modulating the epithelial barrier by targeting PKIα. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Roy S, Elgharably H, Sinha M, et al. Mixed‐species biofilm compromises wound healing by disrupting epidermal barrier function. J Pathol. 2014;233:331‐343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ahmed MI, Alam M, Emelianov VU, et al. MicroRNA‐214 controls skin and hair follicle development by modulating the activity of the Wnt pathway. J Cell Biol. 2014;207:549‐567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hildebrand J, Rütze M, Walz N, et al. A comprehensive analysis of microRNA expression during human keratinocyte differentiation in vitro and in vivo. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131(1):20‐29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sonkoly E, Wei T, Pavez Loriè E, et al. Protein kinase C‐dependent upregulation of miR‐203 induces the differentiation of human keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130(1):124‐134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim YJ, Lee S, Lee HB. Oleic acid enhances keratinocytes differentiation via the upregulation of miR‐203 in human epidermal keratinocytes. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2019;18(1):383‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Srivastava A, Karlsson M, Marionnet C, et al. Identification of chronological and photoageing‐associated microRNAs in human skin. Sci Rep. 2018;8:12990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Syed D, Khan M, Shabbir M, Mukhtar H. MicroRNAs in skin response to UV radiation. Curr Drug Targets. 2013;14:1128‐1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Harada M, Jinnin M, Wang Z, et al. The expression of miR‐124 increases in aged skin to cause cell senescence and it decreases in squamous cell carcinoma. Biosci Trends. 2016;10:454‐459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kraemer A, Chen IP, Henning S, et al. UVA and UVB irradiation differentially regulate microrna expression in human primary keratinocytes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Guo Z, Zhou B, Liu W, et al. MiR‐23a regulates DNA damage repair and apoptosis in UVB‐irradiated HaCaT cells. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;69:68‐76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Degueurce G, D'Errico I, Pich C, et al. Identification of a novel PPAR β/δ/miR‐21‐3p axis in UV ‐induced skin inflammation. EMBO Mol Med. 2016;8(8):919–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greussing R, Hackl M, Charoentong P, et al. Identification of microRNA‐mRNA functional interactions in UVB‐induced senescence of human diploid fibroblasts. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Song J, Liu P, Yang Z, et al. MiR‐155 negatively regulates c‐Jun expression at the post‐transcriptional level in human dermal fibroblasts in vitro: implications in UVA irradiation‐induced photoaging. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012;29:331‐340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Li W, Zhou BR, Hua LJ, Guo Z, Luo D. Differential miRNA profile on photoaged primary human fibroblasts irradiated with ultraviolet A. Tumour Biol. 2013;34:3491‐3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. An I‐S, An S, Choe T‐Β, et al. Centella asiatica protects against UVB‐induced HaCaT keratinocyte damage through microRNA expression changes. Int J Mol Med. 2012;30:1349‐1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Porcheron A, Latreille J, Jdid R, Tschachler E, Morizot F. Influence of skin ageing features on Chinese women's perception of facial age and attractiveness. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2014;36:312‐320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Serre C, Busuttil V, Botto JM. Intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of human skin melanogenesis and pigmentation. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2018;40:328‐347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rijken F, Bruijnzeel PLB, Van Weelden H, Kiekens RCM. Responses of black and white skin to solar‐simulating radiation: differences in DNA photodamage, infiltrating neutrophils, proteolytic enzymes induced, keratinocyte activation, and IL‐10 expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:1448‐1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hearing VJ. Biogenesis of pigment granules: a sensitive way to regulate melanocyte function. J Dermatol Sci. 2005;37:3‐14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lo Cicero A, Delevoye C, Gilles‐Marsens F, et al. Exosomes released by keratinocytes modulate melanocyte pigmentation. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Liu Y, Xue L, Gao H, et al. Exosomal miRNA derived from keratinocytes regulates pigmentation in melanocytes. J Dermatol Sci. 2019;93:159‐167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Marrot L. Pollution and Sun exposure: a deleterious synergy. Mechanisms and opportunities for skin protection. Curr Med Chem. 2018;25:5469‐5486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shi Q, Zhang W, Guo S, et al. Oxidative stress‐induced overexpression of miR‐25: the mechanism underlying the degeneration of melanocytes in vitiligo. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:496‐508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bemis LT, Chen R, Amato CM, et al. MicroRNA‐137 targets microphthalmia‐associated transcription factor in melanoma cell lines. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1362‐1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Guo J, Zhang JF, Wang WM, et al. MicroRNA‐218 inhibits melanogenesis by directly suppressing microphthalmia‐associated transcription factor expression. RNA Biol. 2014;11:732‐741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu Z, et al. Role of microRNA508‐3p in melanogenesis by targeting microphthalmia transcription factor in melanocytes of alpaca. Animal. 2017;11:236‐243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wang P, Zhao Y, Fan R, Chen T, Dong C. MicroRNA‐21a‐5p functions on the regulation of melanogenesis by targeting Sox5 in mouse skin melanocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17:959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Zhao Y, Wang P, Meng J, et al. MicroRNA‐27a‐3p inhibits melanogenesis in mouse skin melanocytes by targeting Wnt3a. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:10921‐10933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kim KH, Lee TR, Cho EG. SH3BP4, a novel pigmentation gene, is inversely regulated by miR‐125b and MITF. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Dynoodt P, Mestdagh P, Van Peer G, et al. Identification of miR‐145 as a key regulator of the pigmentary process. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:201‐209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Noguchi S, Kumazaki M, Yasui Y, Mori T, Yamada N, Akao Y. MicroRNA‐203 regulates melanosome transport and tyrosinase expression in melanoma cells by targeting kinesin superfamily protein 5b. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:461‐469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Dai X, Rao C, Li H, et al. Regulation of pigmentation by microRNAs: MITF‐dependent microRNA‐211 targets TGF‐β receptor 2. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015;28:217‐222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jian Q, An Q, Zhu D, et al. MicroRNA 340 is involved in UVB‐induced dendrite formation through the regulation of RhoA expression in melanocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 2014;34:3407‐3420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Reymermier CBV. New active ingredient proven to shrink pigmented spotsA 100% natural ingredient that is proven to address a major sign of skin ageing. HPC Today. 2020;15(5). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kaidbey KH, Agin PP, Sayre RM, Kligman AM. Photoprotection by melanin—a comparison of black and Caucasian skin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1979;1:249‐260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Montagna W, Carlisle K. Structural changes in aging human skin. J Invest Dermatol. 1979;73:47‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Mimeault M, Batra SK. Recent advances on skin‐resident stem/progenitor cell functions in skin regeneration, aging and cancers and novel anti‐aging and cancer therapies. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:116‐134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Dreesen O, Chojnowski A, Ong PF, et al. Lamin B1 fluctuations have differential effects on cellular proliferation and senescence. J Cell Biol. 2013;200:605‐617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Dimri GP, Lee X, Basile G, et al. A biomarker that identifies senescent human cells in culture and in aging skin in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:9363‐9367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ressler S, Bartkova J, Niederegger H, et al. p16INK4A is a robust in vivo biomarker of cellular aging in human skin. Aging Cell. 2006;5:379‐389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Waaijer MEC, Parish WE, Strongitharm BH, et al. The number of p16INK4a positive cells in human skin reflects biological age. Aging Cell. 2012;11:722‐725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ghosh K, Capell BC. The senescence‐associated secretory phenotype: critical effector in skin cancer and aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:2133‐2139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Shuster S, Black MM, McVITIE E. The influence of age and sex on skin thickness, skin collagen and density. Br J Dermatol. 1975;93:639‐643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Thalyana SV, Slack FJ. MicroRNAs and their roles in aging. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:7‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Röck K, Tigges J, Sass S, et al. miR‐23a‐3p causes cellular senescence by targeting hyaluronan synthase 2: possible implication for skin aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:369‐377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Zhang JA, Zhou BR, Xu Y, et al. MiR‐23a‐depressed autophagy is a participant in PUVA‐ and UVB‐induced premature senescence. Oncotarget. 2016;7:37420‐37435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Li T, Yan X, Jiang M, Xiang L. The comparison of microRNA profile of the dermis between the young and elderly. J Dermatol Sci. 2016;82:75‐83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Muther C, Jobeili L, Garion M, et al. An expression screen for aged‐dependent microRNAs identifies miR‐30a as a key regulator of aging features in human epidermis. Aging (Albany NY). 2017;9:2376‐2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Tinaburri L, D'Errico M, Sileno S, et al. miR‐200a modulates the expression of the DNA repair protein OGG1 playing a role in aging of primary human keratinocytes. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:9147326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Shin KH, Pucar A, Kim RH, et al. Identification of senescence‐inducing microRNAs in normal human keratinocytes. Int J Oncol. 2011;39:1205‐1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lena AM, Mancini M, Rivetti di Val Cervo P, et al. MicroRNA‐191 triggers keratinocytes senescence by SATB1 and CDK6 downregulation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:1763‐1768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Debacker A, Lavaissière L, Ringenbach C, Mondon P. Controlling MicroRNAs to fight skin senescence. Cosmetics & Toiletries; 2016.

- 72. Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. Lancet. 2012;379:P361‐P372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Xia X, Li Z, Liu K, Wu Y, Jiang D, Lai Y. Staphylococcal LTA‐induced miR‐143 inhibits Propionibacterium acnes‐mediated inflammatory response in skin. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:621‐630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. IRB by Sederma . MicroRNA's control: a powerful new strategy for skin embellishment. Cosmetics & Toiletries; 2014.

- 75. Sonkoly E, Wei T, Janson PCJ, et al. MicroRNAs: novel regulators involved in the pathogenesis of psoriasis? PLoS One. 2007;2:e610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, Fuchs E. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature. 2008;452:225‐229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wang J, Qiu Y, Shi NW, et al. microRNA‐21 mediates the TGF‐β1‐induced migration of keratinocytes via targeting PTEN. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2016;20:3748‐3759. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Yang X, Wang J, Guo SL, et al. miR‐21 promotes keratinocyte migration and re‐epithelialization during wound healing. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2011;7:685‐690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Han Z, Chen Y, Zhang Y, et al. MiR‐21/PTEN Axis promotes skin wound healing by dendritic cells enhancement. J Cell Biochem. 2017;18:3511‐3519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Li D, Li X, Wang A, et al. MicroRNA‐31 promotes skin wound healing by enhancing keratinocyte proliferation and migration. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1676‐1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shi J, Ma X, Su Y, et al. MiR‐31 mediates inflammatory signaling to promote re‐epithelialization during skin wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138:2253‐2263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Peng H, Kaplan N, Hamanaka RB, et al. microRNA‐31/factor‐inhibiting hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 nexus regulates keratinocyte differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:14030‐14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Schneider MR, Samborski A, Bauersachs S, Zouboulis CC. Differentially regulated microRNAs during human sebaceous lipogenesis. J Dermatol Sci. 2013;70:88‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Liu J, Cao L, Feng Y, Li Y, Li T. MiR‐338‐3p inhibits TNF‐α‐induced lipogenesis in human sebocytes. Biotechnol Lett. 2017;39:1343‐1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Hou J, Wang P, Lin L, et al. MicroRNA‐146a feedback inhibits RIG‐I‐dependent type I IFN production in macrophages by targeting TRAF6, IRAK1, and IRAK2. J Immunol. 2009;183:2150‐2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Srivastava A, Nikamo P, Lohcharoenkal W, et al. MicroRNA‐146a suppresses IL‐17–mediated skin inflammation and is genetically associated with psoriasis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:550‐561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Taganov KD, Boldin MP, Chang KJ, Baltimore D. NF‐κB‐dependent induction of microRNA miR‐146, an inhibitor targeted to signaling proteins of innate immune responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12481‐12486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Xu J, Wu W, Zhang L, et al. The role of microRNA‐146a in the pathogenesis of the diabetic wound‐healing impairment: correction with mesenchymal stem cell treatment. Diabetes. 2012;61:2906‐2912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lang H, Zhao F, Zhang T, et al. MicroRNA‐149 contributes to scarless wound healing by attenuating inflammatory response. Mol Med Rep. 2017;16:2156‐2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. van Solingen C, Araldi E, Chamorro‐Jorganes A, Fernández‐Hernando C, Suárez Y. Improved repair of dermal wounds in mice lacking microRNA‐155. J Cell Mol Med. 2014;18:1104‐1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Yang LL, Liu JQ, Bai XZ, et al. Acute downregulation of miR‐155 at wound sites leads to a reduced fibrosis through attenuating inflammatory response. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;453:153‐159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Yan H, Song K, Zhang G. MicroRNA‐17‐3p promotes keratinocyte cells growth and metastasis via targeting MYOT and regulating Notch1/NF‐κB pathways. Pharmazie. 2017;72:543‐549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Aunin E, Broadley D, Ahmed MI, Mardaryev AN, Botchkareva NV. Exploring a role for regulatory miRNAs in wound healing during ageing:involvement of miR‐200c in wound repair. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Clark AK, Saric S, Sivamani RK. Acne scars: how do we grade them? Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:139‐144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Madhyastha R, Madhyastha H, Nakajima Y, Omura S, Maruyama M. MicroRNA signature in diabetic wound healing: promotive role of miR‐21 in fibroblast migration. Int Wound J. 2012;9:355‐361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Li G, Zhou R, Zhang Q, Jiang B, Wu Q, Wang C. Fibroproliferative effect of microRNA‐21 in hypertrophic scar derived fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2016;345:93‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Liu Y, Wang X, Yang D, Xiao Z, Chen X. MicroRNA‐21 affects proliferation and apoptosis by regulating expression of PTEN in human keloid fibroblasts. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:561e‐573e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Zhu HY, Li C, Bai WD, et al. MicroRNA‐21 regulates hTERT via PTEN in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Wang T, Feng Y, Sun H, et al. miR‐21 regulates skin wound healing by targeting multiple aspects of the healing process. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:1911‐1920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Pastar I, Khan AA, Stojadinovic O, et al. Induction of specific microRNAs inhibits cutaneous wound healing. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:29324‐29335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Shi K, Qiu X, Zheng W, Yan D, Peng W. MiR‐203 regulates keloid fibroblast proliferation, invasion, and extracellular matrix expression by targeting EGR1 and FGF2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2018;108:1282‐1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zhou Z, Shu B, Xu Y, et al. microRNA‐203 modulates wound healing and scar formation via suppressing Hes1 expression in epidermal stem cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;49:2333‐2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Guo J, Lin Q, Shao Y, Rong L, Zhang D. miR‐29b promotes skin wound healing and reduces excessive scar formation by inhibition of the TGF‐β1/Smad/CTGF signaling pathway. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2017;95:437‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Guo L, Huang X, Liang P, et al. Role of XIST/miR‐29a/LIN28A pathway in denatured dermis and human skin fibroblasts (HSFs) after thermal injury. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119:1463‐1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Bi S, Chai L, Yuan X, Cao C, Li S. MicroRNA‐98 inhibits the cell proliferation of human hypertrophic scar fibroblasts via targeting Col1A1. Biol Res. 2017;50:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Xiao K, Luo X, Wang X, Gao Z. MicroRNA‐185 regulates transforming growth factor‐β1 and collagen‐1 in hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:1489‐1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]