Abstract

Background:

Ketamine has been a safe and effective sedative agent commonly used for painful pediatric procedures in the emergency department (ED). This study aimed to compare the effect of dexmedetomidine (Dex) and propofol when used as co-administration with ketamine on recovery agitation in children who underwent procedural sedation.

Materials and Methods:

In this prospective, randomized, and double-blind clinical trial, 93 children aged between 3 and 17 years with American Society of Anesthesiologists Class I and II undergoing short procedures in the ED were enrolled and assigned into three equal groups to receive either ketadex (Dex 0.7 μg/kg and ketamine 1 mg/kg), ketofol (propofol 0.5 mg/kg and ketamine 0.5 mg/kg), or ketamine alone (ketamine1 mg/kg) intravenously. Incidence and severity of recovery agitation were evaluated using the Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale and compared between the groups.

Results:

There was no statistically significant difference between the three groups with respect to age, gender, and weight (P > 0.05). The incidence of recovery agitation was 3.2% in the ketadex group, 22.6% in the ketofol group, and 22.6% in the ketamine group (P = 0.002, children undergoing short procedures were recruited). There was a less unpleasant recovery reaction (hallucination, crying, and nightmares) in the ketadex group compared with the ketofol and ketamine groups (P < 0.05). There was no difference in the incidence of oxygen desaturation between the groups (P = 0.30).

Conclusion:

The co-administering of Dex to ketamine could significantly reduce the incidence and severity of recovery agitation in children sedated in the ED.

Keywords: Dexmedetomidine, ketamine, procedural sedation, propofol, recovery agitation

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric patients in the emergency department (ED) frequently require painful procedures, and humane care in such situations often necessitates medical sedation and analgesia. Analgesics and sedatives are required in ED to prevent the potential pain and stress caused by painful procedures. Numerous agents have been suggested for this purpose, while each of them has some disadvantages that limit their use in different clinical situations.[1]

Ketamine has been a safe and effective sedative agent commonly used for painful ED pediatric procedures.[2,3] Ketamine is a noncompetitive antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor, which is used for premedication, sedation, and induction as well as maintenance of general anesthesia. It has a rapid onset with a short duration of action that induces good analgesia, sedation, and amnesia with a rapid recovery.[4,5] Maintaining airway reflexes with minimal effect on cardiovascular and respiratory function made ketamine a popular sedative choice for pediatric procedures in the ED.[4,5,6]

Some emergency physicians have limited the use of ketamine as a sedative in the ED due to recovery agitation. Recovery agitation is characterized by disorientation, agitation, delusion, hallucination, and restlessness.[7,8] In this regard, cognitive changes, memory impairment, and wild crying might occur, especially in children.[2,3,4,5,6,7,8] However, the ketamine-induced agitation can be overcome by co-administration of other drugs. Numerous studies have been tried to compare different drugs such as midazolam, dexmedetomidine (Dex), propofol, clonidine, and haloperidol to reduce these adverse responses.[8,9,10]

Dex is a potent α2-adrenergic agonist, used to induce sedation, reduce the dose of anesthetic agent, and improve hemodynamic stability, which suggests that it can be a suitable adjuvant to ketamine anesthesia.[11] Propofol is a sedative-hypnotic agent with rapid onset and short duration of action. It has been proposed that propofol can reduce the incidence of emergence agitation.[6]

This study aimed to evaluate the effect of Dex and propofol when used as co-administration with ketamine on recovery agitation in children who underwent procedural sedation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and setting

This prospective, randomized, and double-blind study was conducted from May 2017 to March 2019 at Al-Zahra and Kashani Hospitals, Isfahan, Iran. The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.REC.1396.3.356). The trial was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials under the number IRCT20190422043340N1. The investigators adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki principles throughout the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients' parents or legal guardians before enrollment into the study.

Study population

All the patients aged between 3 and 17 years who were candidates for painful procedures in the ED were eligible for inclusion. Inclusion criteria were pain score >5 and class 1 or 2 in the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification. Pain score was evaluated using Faces Pain Scale-Revised in children aged 3–5 years or Visual Analog Scale in children aged >5 years.[12]

Patients with any of the following criteria were not included in the study: receiving any sedative or analgesic agents within the previous 24 h; all types of heart block, congenital heart diseases, or ventricular dysfunction; allergy to ketamine, Dex, or propofol; patients with hepatic or renal disorders or a previous history of psychiatric; and any contraindication to study drugs (e.g. hypersensitivity). Procedures that took more than 15 min and permanent instability in hemodynamic after medication administration were excluded too.

Study protocol

The included participants were random allocated to one of the three groups using a random-allocation software package: ketadex group (Dex and ketamine), ketofol group (propofol and ketamine), and ketamine group (Ketamine only).

The study drugs were prepared by an independent investigator who was not involved in clinical management. The nurses who administered the agents had to leave the sedation unit after medication administration and then physicians were permitted for entrance. The patients and their parents as well as the physicians were blinded to the drugs administered.

Ketadex group: Received intravenous (IV) Dex 0.7 μg/kg (200 mcg/2 ml vial of Precedex; Hospira, Inc., Lake Forest, IL 60045, USA) and ketamine 1 mg/kg (500 mg/10 ml vial of ketamine hydrochloride, Trittau, Germany) diluted by 0.9% saline up to 20 mL in one syringe over 4 min

Ketofol group: Received IV propofol 0.5 mg/kg (200 mg/20 ml ampoule of propofol 1%; Fresenius Kabi, Homburg, Germany) and ketamine 0.5 mg/kg diluted by 0.9% saline up to 20 mL in one syringe over 4 min

Ketamine group (control group): Received IV ketamine 1 mg/kg diluted by 0.9% saline up to 20 mL over 4 min.

In all participants, sedations were performed by emergency medicine residents under the supervision of an emergency medicine specialist. Sedation level was assessed using Richmond Agitation–Sedation Scale (RASS) [Table 1].[9] The RASS was assessed every 5 min until the end of the procedure. Additional doses of ketamine 0.25 mg/kg IV bolus were administered when RASS was more than − 4 (deep sedation) at any moment during the procedure in each group. Standard treatment has been taken for all patients, such as an ice bag or limb immobilization and splinting.

Table 1.

Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

| Score | Term | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Combative | Overtly combative or violent; immediate danger to staff |

| 3 | Very agitated | Pulls on or removes tube(s) or catheter(s) or has aggressive behavior toward staff |

| 2 | Agitated | Frequent nonpurposeful movement or patient-ventilator dyssynchrony |

| 1 | Restless | Anxious or apprehensive but movements not aggressive or vigorous |

| 0 | Alert and calm | |

| −1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert, but has sustained (>10 s) awakening with eye contact to voice |

| −2 | Light sedation | Briefly (<10 s) awakens with eye contact to voice |

| −3 | Moderate sedation | Any movement (but no eye contact) to voice |

| −4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice, but any movement to physical stimulation |

| −5 | Unarousable | No response to voice or physical stimulation |

Adapted from Ely EW, et al.: Monitoring sedation status over time in ICU patients: Reliability and validity of the RASS. JAMA 2003; 289: 2983-2991. RASS=Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

Presedation agitation and postprocedure agitation by a research physician, who was blinded to the group allocation, were recorded using RASS. Severe agitation (RASS ≥3) in the recovery phase was treated by 0.05 mg/kg of midazolam if needed. Patients with a RASS of ≥1 were considered as having agitation.

The noninvasive blood pressure, continuous cardiac monitoring, and pulse oximetry of each patient were monitored during the sedation. The oxygen saturation (SpO2), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate (PR), and RASS were recorded at baseline and then every 5 min.

Physicians provided any supportive/resuscitative measures at their discretion. Adverse effects such as hypoxia (SpO2 <92% for 30 s), hypotension, and bradycardia (according to minimum of heart rate and blood pressure for child age) were assessed and managed during sedation.

After the procedure, the patients were evaluated regarding hallucination, crying, and nightmares during recovery and the results were recorded in the data gathering form.

The data including age, sex, weight, and type of procedure were collected by a research physician. Furthermore, the duration of procedure and adverse events were recorded.

The requisite sample size was calculated to be 31 patients in each group regarding the confidence level of 95%, power of 80%, α-error of 5%, and an agitation incidence of 25% in the group receiving ketamine alone base on a previous study.[13]

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS), version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for statistical analysis. The normality of data was assessed by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Numerical data were expressed as means ± standard deviation and categorical data as frequency (percentage). Chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were performed to examine the relationship between categorical variables. The independent t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for comparison of numerical data. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

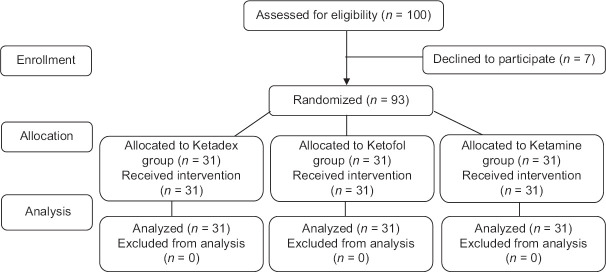

A total of 100 patients were initially enrolled. Of them, 7 were excluded. Therefore, data regarding the 93 children were included in the study [Figure 1]. The baseline characteristics of patients are shown in Table 2. The mean ages of patients were 8.16 ± 4.36 years and 55 (59.1%) were male. There were no significant differences in age, sex, weight, procedures, and ASA classifications between the groups (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Consort study flowchart

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study patients

| Variables | Ketadex (n=31) | Ketofol (n=31) | Ketamine (n=31) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 7.27±3.74 | 8.95±5.04 | 8.24±4.18 | 0.31 |

| Gender, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 18 (58.1) | 20 (64.5) | 17 (54.8) | 0.73 |

| Female | 13 (41.9) | 11 (35.5) | 14 (45.2) | |

| Weight, kg | 25.9±11.9 | 33.3±20.1 | 29.0±14.6 | 0.18 |

| ASA class, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 22 (71.0) | 22 (71.0) | 21 (67.8) | 0.87 |

| 2 | 9 (29.0) | 9 (29.0) | 10 (32.2) | |

| Procedure, n (%) | ||||

| Fracture reduction | 13 (41.9) | 14 (45.2) | 20 (64.5) | 0.56 |

| Laceration repair | 16 (51.6) | 13 (41.9) | 9 (22.6) | |

| Dislocation reduction | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| FB removal | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 0 | |

| Others | 0 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) |

Data were expressed as mean±SD. ASA=American society of anesthesiologists; FB=Foreign body; SD=Standard deviation

Mean PR, MAP, and SpO2 were not different between the three groups at evaluated times (P > 0.05). There were no significant differences between the groups in the pain scores, presedation agitation, and duration of procedure [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of sedation-related parameters in the three groups

| Variables | Ketadex (n=31) | Ketofol (n=31) | Ketamine (n=31) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pain score, VAS/FPS-R | 7.23±1.17 | 7.32±0.87 | 7.84±1.11 | 0.063 |

| Duration of procedure, minute | 10.2±3.1 | 10.1±3.4 | 10.5±3.5 | 0.900 |

| Presedation agitation, 1≤ RASS | 7 (22.6) | 3 (9.7) | 2 (6.5) | 0.134 |

| Recovery agitation, 1≤ RASS | 1 (3.2) | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | 0.002 |

| Severe agitation (3≤ RASS), n (%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (12.9) | 0.015 |

| Additional ketamine required patients, n (%) | 11 (35.5) | 24 (77.4) | 27 (87.1) | <0.001 |

Data were expressed as mean±SD. VAS=Visual Analog Scale; FPS-R=Faces Pain Scale-Revised; SD=Standard deviation; RASS=Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale

The incidence of recovery agitation (RASS ≥1) was 3.2% in the ketadex group, 22.6% in the ketofol group, and 22.6% in the ketamine group (P = 0.002). The recovery agitation was significantly less in the ketadex group [Table 3]. The number of patients who developed severe agitation requiring midazolam (RASS ≥3) was four patients, and all of them were in the ketamine group. There was a less unpleasant recovery reaction (hallucination, crying, and nightmares) in the ketadex group compared with the ketofol and ketamine groups [Table 4].

Table 4.

Adverse events and interventions in the three groups

| Variables | Ketadex (n=31) | Ketofol (n=31) | Ketamine (n=31) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crying | 1 (3.2) | 4 (12.9) | 4 (12.9) | 0.045 |

| Hallucinations | 0 | 3 (9.7) | 5 (16.1) | 0.024 |

| Nightmares | 1 (3.2) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (19.3) | 0.028 |

| Desaturation | 14 (45.2) | 20 (64.5) | 17 (54.8) | 0.307 |

| Hypotension (transient) | 7 (22.6) | 2 (6.5) | 0 | 0.009 |

| Respiratory intervention | ||||

| Airway maneuvers | 7 (22.6) | 5 (16.1) | 5 (16.2) | 0.377 |

| Oxygen supplement was need | 7 (22.6) | 15 (48.4) | 14 (45.2) | 0.067 |

| Midazolam administration, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 4 (12.9) | 0.015 |

Data expressed as, n (%)

Additional ketamine (0.25 mg/kg at least) was required in 62 patients to achieve deep sedation. It was significantly less in the ketadex group (P < 0.001).

There was no difference in the incidence of oxygen desaturation between the groups. No patients in either group required assisted ventilation (bag-valve-mask ventilation and tracheal intubation), and all responded quickly to airway repositioning or supplemental oxygen [Table 4]. The transient hypotension was significantly higher in the ketadex group. Transient hypotension was treated mainly with IV fluid (0.9% saline 10 mL/kg) bolus administration in all subjects.

DISCUSSION

In this trial, we found that the co-administering of Dex to ketamine could significantly reduce the incidence and severity of recovery agitation. This is clinically important and that clinicians formerly reluctant to administer ketamine as a sole agent for PSA can now do so with greater confidence by co-administering Dex.

The incidence of recovery agitation (ketamine group) in this study (22.6%) was similar to previous studies. In some studies, in Europe and the United States, recovery agitation has been estimated approximately 15% to 20% and in Turkey and India approximately 25% and 30%, respectively.[4,9,13,14] In many previous studies, it was not clear which symptoms were known as agitation. Some studies have identified recovery agitation based on patient's dreams and experiences or observations made by researchers during sedation and recovery, none of which are objective.[4,6,9,13,14]

Recovery agitation in a meta-analysis of 32 ED studies on pediatric ketamine PSA was described in 7.6% and was considered clinically important in 1.4%.[15] In this study, four patients (12.9%) in the ketamine group aged 14–16 years had severe recovery agitation treated with midazolam. Green et al. showed that increased age was significantly associated with recovery agitation, but adolescents were not at substantially higher risk of clinically important recovery agitation.[15]

Dex has recently been introduced in clinical practice. The optimal clinical dose has not been well documented. Based on the experience of previous studies,[16,17] we chose a 0.7 μg/kg dose of Dex for our study. In the current study, Dex reduced significantly the incidence of recovery agitation and unpleasant recovery reaction (hallucination, crying, and nightmares). Dex may prevent the emergence phenomena from ketamine, whereas ketamine may prevent bradycardia and hypotension, which has been reported with Dex.[18] Trivedi et al. reported that Dex reduced delirium caused by ketamine significantly in comparison to the control group and midazolam group. This result was in accordance with a previous study that reported Dex decreased significantly the frequency of psychomotor impairment and delirium in comparison to midazolam.[10] Djaiani et al. showed that postoperative delirium in cardiac surgery was less common when Dex was used for sedation compared to propofol.[19] These findings also were reported by Pasin et al. in critically ill patients.[20] Several studies reported that Dex significantly reduces the incidence of emergence agitation after general anesthesia in children.[16,21,22] In contrast to current studies, these trials were done in the operation room.

In the current study, recovery agitation was similar in the ketofol group (22.6%) and the ketamine group (22.6%). Previous studies by Shah et al. have shown similar findings.[23] The sedative effects of propofol are thought to mitigate adverse effects such as recovery agitation. Willman and Andolfatto suggested that ketofol may be associated with a lower incidence of unpleasant recovery reaction than ketamine alone.[24] Jalili et al. reported that the incidence of emergence agitation in the ketofol group was lower as compared to the control group in children undergoing tonsillectomy, but this difference was not significant.[25] This difference may be because this study was performed in a different setting and different age groups of patients.

The incidence of oxygen desaturation in the ketofol group was higher than in other groups, but it was not significant. Taghinia et al. demonstrated that Dex decreased the incidence of oxygen desaturation and reduced the amounts of narcotic and anxiolytic requirements.[26] In a study by Canpolat et al., a significant amount of respiratory depression and hypoxia was observed in the ketamine-propofol group but not in the ketamine-Dex group.[27] Tammam reported that oxygen desaturation and emergence phenomena occurred more frequently in the ketamine group as compared to the ketamine-Dex group.[28] In previous studies, similar to the current study, no patients in either the ketadex, ketofol, or ketamine group required any significantly assisted ventilation (bag-valve-mask ventilation or tracheal intubation); only a few cases required supplemental oxygen or airway repositioning.[10,23,24,27,29]

Limitations

There are some limitations to this study. First, the sample size was small. Second, only children undergoing short procedures were recruited in the study. Third, evaluation scales for recovery agitation were subjective, which might lead to some errors. The majority of children in this study were younger than 10 years. Teenage patients may manifest more unpleasant recovery reactions. Furthermore small children (under 3 years old) not included in this study because of difficulty in their pain score assessment, inability to exactly explore their psychological experiences and some difference in their medication dosage. We may suggest to compare the different doses of Dex in these specific groups separately in future studies.

CONCLUSION

The co-administering of Dex to ketamine (ketadex) could significantly reduce the incidence and severity of recovery agitation in children sedated in the ED. There was a less unpleasant recovery reaction (hallucination, crying, and nightmares) in the ketadex group compared with the ketofol and ketamine groups. These findings suggest that administration of Dex with ketamine may form an effective combination for procedural sedation in children.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was funded by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences.

Conflict of interests

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Krauss BS, Krauss BA, Green SM. Procedural sedation and analgesia in children. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1405676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizkhani R, Bahadori A, Shariati M, Golshani K, Ahmadi O, Masoumi B. Ketamine versus ketamine/magnesium sulfate for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department: A randomized clinical trial. Adv Biomed Res. 2018;7:19. doi: 10.4103/abr.abr_143_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majidinejad S, Kajbaf A, Khodadoostan M, Dolatkhah S, Kajbaf MH, Adibi P, et al. Ketamine administration makes patients and physicians satisfied during gastro-enteric endoscopies. J Res Med Sci. 2015;20:860–4. doi: 10.4103/1735-1995.170607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perumal DK, Adhimoolam M, Selvaraj N, Lazarus SP, Mohammed MA. Midazolam premedication for Ketamine-induced emergence phenomenon: A prospective observational study. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:89–93. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.155758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MajidiNejad S, Goudarzi L, Heydari F. Effect of ondansetron on the incidence of ketamine associated vomiting in procedural sedation and analgesia in children: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Int J Pediatr. 2018;6:7511–8. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amr MA, Shams T, Al-Wadani H. Does haloperidol prophylaxis reduce ketamine-induced emergence delirium in children? Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2013;13:256–62. doi: 10.12816/0003231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heydari F, Azarian R, Masoumi B, Ghahnavieh AA. The effect of low dose ketamine on the need for morphine in patients with multiple trauma in emergency department. Eurasian J Emerg Med. 2020;19:219–26. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherwin TS, Green SM, Khan A, Chapman DS, Dannenberg B. Does adjunctive midazolam reduce recovery agitation after ketamine sedation for pediatric procedures.A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial? Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:229–38. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(00)70073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akhlaghi N, Payandemehr P, Yaseri M, Akhlaghi AA, Abdolrazaghnejad A. Premedication with midazolam or haloperidol to prevent recovery Agitation in adults undergoing procedural sedation with ketamine: A randomized double-blind clinical trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2019;73:462–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Trivedi S, Kumar R, Tripathi AK, Mehta RK. A comparative study of dexmedetomidine and midazolam in reducing delirium caused by ketamine. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:C01–4. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2016/18397.8225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azizkhani R, Heydari F, Ghazavi M, Riahinezhad M, Habibzadeh M, Bigdeli A, et al. Comparing sedative effect of dexmedetomidine versus midazolam for sedation of children while undergoing computerized tomography imaging. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2020;15:245–51. doi: 10.4103/jpn.JPN_107_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hicks CL, von Baeyer CL, Spafford PA, van Korlaar I, Goodenough B. The Faces Pain Scale-Revised: Toward a common metric in pediatric pain measurement. Pain. 2001;93:173–83. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00314-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vardy JM, Dignon N, Mukherjee N, Sami DM, Balachandran G, Taylor S. Audit of the safety and effectiveness of ketamine for procedural sedation in the emergency department. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:579–82. doi: 10.1136/emj.2007.056200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sener S, Eken C, Schultz CH, Serinken M, Ozsarac M. Ketamine with and without midazolam for emergency department sedation in adults: A randomized controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:109–14.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green SM, Roback MG, Krauss B, Brown L, McGlone RG, Agrawal D, et al. Predictors of emesis and recovery agitation with emergency department ketamine sedation: An individual-patient data meta-analysis of 8,282 children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:171–80.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen JY, Jia JE, Liu TJ, Qin MJ, Li Wx. Comparison of the effects of dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and placebo on emergence agitation after strabismus surgery in children. Can J Anaesth. 2013;60:385–92. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-9886-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuen VM. Dexmedetomidine: Perioperative applications in children. Paediatr Anaesth. 2010;20:256–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2009.03207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tobias JD. Dexmedetomidine and ketamine: An effective alternative for procedural sedation? Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:423–7. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318238b81c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Djaiani G, Silverton N, Fedorko L, Carroll J, Styra R, Rao V, et al. Dexmedetomidine versus propofol sedation reduces delirium after cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Anesthesiology. 2016;124:362–8. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pasin L, Landoni G, Nardelli P, Belletti A, Di Prima AL, Taddeo D, et al. Dexmedetomidine reduces the risk of delirium, agitation and confusion in critically Ill patients: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2014;28:1459–66. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun Y, Li Y, Sun Y, Wang X, Ye H, Yuan X. Dexmedetomidine effect on emergence agitation and delirium in children undergoing laparoscopic hernia repair: A preliminary study. J Int Med Res. 2017;45:973–83. doi: 10.1177/0300060517699467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akin A, Bayram A, Esmaoglu A, Tosun Z, Aksu R, Altuntas R, et al. Dexmedetomidine vs midazolam for premedication of pediatric patients undergoing anesthesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2012;22:871–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2012.03802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah A, Mosdossy G, McLeod S, Lehnhardt K, Peddle M, Rieder M. A blinded, randomized controlled trial to evaluate ketamine/propofol versus ketamine alone for procedural sedation in children. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:425–33.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willman EV, Andolfatto G. A prospective evaluation of “ketofol” (ketamine/propofol combination) for procedural sedation and analgesia in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:23–30. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalili S, Esmaeeili A, Kamali K, Rashtchi V. Comparison of effects of propofol and ketofol (Ketamine-Propofol mixture) on emergence agitation in children undergoing tonsillectomy. Afr Health Sci. 2019;19:1736–44. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v19i1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taghinia AH, Shapiro FE, Slavin SA. Dexmedetomidine in aesthetic facial surgery: Improving anesthetic safety and efficacy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:269–76. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000293867.05857.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Canpolat DG, Esmaoglu A, Tosun Z, Akn A, Boyaci A, Coruh A. Ketamine-propofol vs ketamine-dexmedetomidine combinations in pediatric patients undergoing burn dressing changes. J Burn Care Res. 2012;33:718–22. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3182504316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tammam TF. Comparison of the efficacy of dexmedetomidine, ketamine, and a mixture of both for pediatric MRI sedation. Egypt J Anaesth. 2013;29:241–6. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joshi AB, Shankaranarayan UR, Hegde A, Manju R. To compare the efficacy of two intravenous combinations of drugs ketamine-propofol vs ketamine-dexmedetomidine for sedation in children undergoing dental treatment. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;13:529–35. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]