Abstract

This follow-up analysis of a randomized clinical trial investigates the association of multidomain interventions targeting vascular risk factors with dementia incidence among community-dwelling older adults.

Epidemiological studies suggest that up to 40% of dementia cases are attributable to modifiable risk factors.1 However, there is no consistent evidence that multidomain interventions targeting these risk factors can prevent or delay dementia.2 In the pragmatic multidomain Prevention of Dementia by Intensive Vascular Care (preDIVA) trial, we observed that targeting vascular risk factors over 6 to 8 years did not significantly reduce dementia risk in community-dwelling older people.3 Here we report the results of the preDIVA trial after an extended observational follow-up up to 12 years after baseline.

Methods

The preDIVA trial included 3526 participants aged 70 to 78 years without dementia who were recruited from the general population between 2006 and 2009, of whom 4% had a Mini-Mental State Examination score less than 24 points. Participants were randomized to either a multidomain intervention that targeted vascular risk factors (smoking, unhealthy diet, physical inactivity, overweight, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes) by a practice nurse or usual care during the 6- to 8-year period.3 The study was approved by the ethical review board of the Academic Medical Centre, and participants gave written informed consent prior to their baseline visit.

During up to 4 years of observational follow-up, we assessed dementia status in all participants who survived without dementia during the trial phase, resulting in a median (IQR) follow-up of 10.3 (7.0-11.0) years since randomization. Surviving participants with a normal Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status4 score greater than 30 and without a formal dementia diagnosis were labeled as having no dementia. In all other cases, the general practitioners’ electronic health records were searched for information on possible dementia. An outcome adjudication committee of dementia specialists validated all clinical outcomes masked to group allocation.3 Cox proportional hazards and Fine-Gray models were used to calculate 2-tailed P values with statistical significance defined at P < .05. All analyses were conducted using R version 4.0.3 (R Foundation).

Results

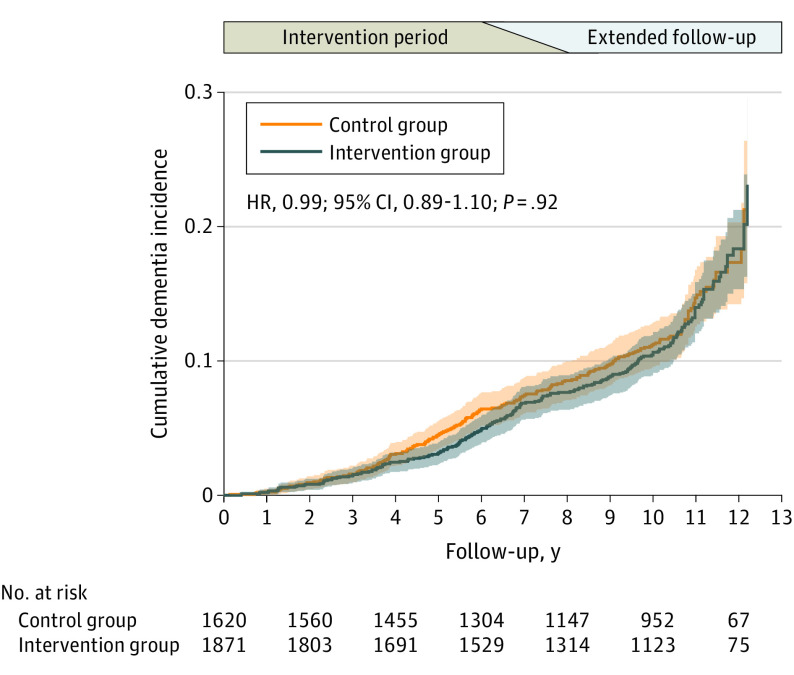

During observational extension, 176 participants diagnosed with dementia were identified in addition to the 233 participants diagnosed with dementia during the trial phase (missing: 35 [1.0%]). Since baseline, dementia developed in 217 of 1871 intervention participants (11.6%) vs 192 of 1620 control participants (11.9%) (hazard ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.89-1.10; P = .92; Figure). In intention-to-treat and per-protocol subgroup analyses, we found no statistically significant interactions for sex, age, cardiovascular history, apolipoprotein e4 genotype, hypertension (treated and untreated), or hypercholesterolemia (treated and untreated). In total, 561 participants (29.7%) died in the intervention group vs 487 (29.8%) in the control group (hazard ratio, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.92-1.04; P = .69). Fine-Gray models that accounted for the competing risk of death gave similar results for the intervention effect on dementia. The proportional hazard assumption was satisfied according to tests and visual inspection of the Schoenfeld residuals as a function of time, and there was no evidence for a time-dependent effect in a dynamic model (Kolmogorov and Cramer tests).

Figure. Cumulative Dementia Incidence Curve.

The shaded area indicates 95% CIs.

Discussion

The results of the present long-term follow-up study support the notion that pragmatic multidomain interventions targeting vascular risk factors in a real-world setting may not reduce dementia incidence in old age. The study population may have been too old to counteract lifetime damage, or the study contrast may have been insufficient because of the high quality of usual care in the control group. However, our findings correspond with the only other long-term multidomain trial with dementia diagnosis as outcome in a younger population of individuals who had diabetes (n = 3800; 83% younger than 65 years at baseline) and with a 10-year highly intensive intervention (10 to 13 years of follow-up).5

The magnitude of potential benefits for dementia prevention by lifestyle interventions may be less than projected from cohort studies,1 as the data have now shown in older individuals. For the broader age-spectrum from midlife to late life, a larger window of opportunity may be present,1 although causality is unclear and achieving optimal risk-level control seems unrealistic in a real-world setting. Multidomain interventions may be probed in populations at higher risk, at younger ages, and in countries with less developed preventive health care.

References

- 1.Livingston G, Huntley J, Sommerlad A, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2020 report of the Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2020;396(10248):413-446. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30367-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Preventing Dementia and Cognitive Impairment; Downey A, Stroud C, Landis S, Leshner AI, eds. Preventing Cognitive Decline and Dementia: A Way Forward. National Academies Press (US); 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moll van Charante EP, Richard E, Eurelings LS, et al. Effectiveness of a 6-year multidomain vascular care intervention to prevent dementia (preDIVA): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10046):797-805. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30950-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt J, Spencer M, Folstein M. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry. Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology. 1988;1(2):111-8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espeland MA, Luchsinger JA, Baker LD, et al. ; Look AHEAD Study Group . Effect of a long-term intensive lifestyle intervention on prevalence of cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2017;88(21):2026-2035. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]