Abstract

Purpose: To explore the association between Alzheimer’s disease and apolipoprotein E (ApoE). Studies on this relationship are plentiful, but they mostly suffer from the disadvantage of inadequate sample size, so we conducted this meta-analysis to assess the association between ApoE polymorphisms and AD in humans. Method: The research literature centered on the association between Alzheimer’s disease and ApoE polymorphisms was searched using databases including EMBASE, CQVIP, Medline, Web of knowledge, PubMed, Cochrane Library, CNKI, and Wanfang Data up to July 2020. The quality of the included literature was assessed using the NOS scale. We used RevMan 5.3 statistical software for the data extraction and meta-analysis. Results: A total of 569 studies were retrieved according to the search strategy and the inclusion criteria. After removing the duplicate studies and studies that did not match the topic, 155 studies were obtained. 39 publications were finally included according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Five of them were selected for the meta-analysis after a careful evaluation. Conclusion: Patients with Alzheimer’s disease have a high positive rate of the ε4 allele (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.38-3.48) and a low positive rate of the ε3 allele, but there is no significant association between the ApoE ε2 allele and AD (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.19-2.58). The positivity rates of the ε4/ε4 and ε3/ε4 genotypes were higher in the case group (OR = 3.82, 95% CI: 1.86-7.84; OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.40-3.06), but the positivity rates of the ε2/ε3 and ε3/ε3 genotypes were significantly lower in the case group than in the control group (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.18-2.11; OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36-0.75).

Keywords: Apolipoprotein E, polymorphisms, Alzheimer’s disease, meta-analysis

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a degenerative disease of the central nervous system characterized by a gradual decline in memory, reasoning, and other abilities over time, a decline that significantly reduces patients’ quality of life [1]. It is divided into two subtypes, early-onset (LOAD, age ≤ 65 years) and late-onset (EOAD, age > 65 years) [2]. Due to the increasing prevalence of AD, its treatment and mechanisms attract increasing interest [3]. However, there are only five approved therapies for AD, and they only control the progression of the disease, but they do not cure it, let alone prevent it. There is also no unanimous opinion on the specific pathogenesis of AD. A variety of hypotheses, including hormonal decline and neurotransmitter depletion, partially explain the onset and progression of the disease [4,5].

In recent years, the genetic polymorphisms of this disease have become a hot topic in exploring the mystery of AD. AD is particularly closely linked to apolipoprotein E (ApoE) [6], the ApoE gene located on chromosome 19 with a molecular weight of about 34 kDa, and mainly sourced from the liver and brain [7]. In humans, ε2, ε3, and ε4 are the three most common alleles of ApoE, with ε4 having the closest relationship to AD [8]. These three alleles can be combined into six corresponding genotypes, ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε3, ε3/ε4, and ε4/ε4 [9]. The link between the onset of AD and ApoE is particularly strong because it has been well documented that the risk of having AD with an ApoE ε4 allele is three times higher than without [10], and the elimination of this gene can significantly improve the condition, which is very compelling [11]. There are now a large number of studies examining the association between AD and ApoE, but most of the studies were based on small sample sizes, so we conducted this meta-analysis to assess the association between ApoE polymorphisms and AD.

Materials and methods

Ethics

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria: (1) articles studying patients diagnosed with AD according to the diagnostic manual, (2) articles covering patients who signed an informed consent, (3) articles in Chinese or English, and (4) articles with full-text information available. Exclusion criteria: (1) reviews, case reports, (2) articles with incomplete data or inaccessible full text, (3) articles incompatible with the study topic, and (4) articles that did not clearly indicate the method of diagnosing AD.

Literature search method

The PubMed, CQVIP, EMBASE, China Knowledge, and Wanfang data databases were searched up to July 2020. The search filter was set as (“AD”[Mesh]) OR (AD)) OR (Dementia, Senile)) OR (Senile Dementia)) OR (Dementia, Alzheimer Type)) OR (Alzheimer Type Dementia)) OR (Alzheimer-Type Dementia (ATD))) OR (Alzheimer Type Dementia (ATD))) OR (Dementia, Alzheimer-Type (ATD))) OR (Alzheimer Type Senile Dementia)) OR (Primary Senile Degenerative Dementia)) OR (Dementia, Primary Senile Degenerative)) OR (Alzheimer Sclerosis)) OR (Sclerosis, Alzheimer)) OR (Alzheimer Syndrome)) OR (Alzheimer Dementia)) OR (Alzheimer Dementias)) OR (Dementia, Alzheimer)) OR (Dementias, Alzheimer)) OR (Senile Dementia, Alzheimer Type)) OR (Acute Confusional Senile Dementia)) OR (Senile Dementia, Acute Confusional)) OR (Dementia, Presenile)) OR (Presenile Dementia)) OR (AD, Late Onset)) OR (Late Onset AD)) OR (AD, Focal Onset)) OR (Focal Onset AD)) OR (Familial Alzheimer Disease (FAD))) OR (Alzheimer Disease, Familial (FAD))) OR (Alzheimer Diseases, Familial (FAD))) OR (Familial Alzheimer Diseases (FAD))) OR (Alzheimer Disease, Early Onset)) OR (Early Onset Alzheimer Disease)) OR (Presenile Alzheimer Dementia) AND (ApoE). When searching the Chinese database by title or keyword, the search filter is “Alzheimer” OR “AD” AND “ApoE”.

Data extraction

The extracted data included the title, first author, publication date, number of cases in each group, country and ethnicity of the patients, type of study, criteria for AD diagnosis, and genotype distribution.

The literature search was conducted by two researchers based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. When disagreements arose about the inclusion, a third researcher helped decide the final results. The quality of the included literature was assessed on a case-by-case basis using the NOS scale.

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis was performed using RevMan 5.3 statistical software. An I2 test was used to determine the heterogeneity among the studies, and if I2 < 50%, then the studies were considered homogeneous, and the fixed effect model was used to analyze the included data. If I2 ≥ 50% the studies were considered heterogeneous, and then the random effect model was used to analyze the included data. In the meta-analysis, P < 0.05 indicates a difference is statistically significant. A bias analysis of the included studies was performed using a funnel plot, and the results of the analysis were represented by forest plots.

Results

Baseline data for including the literature

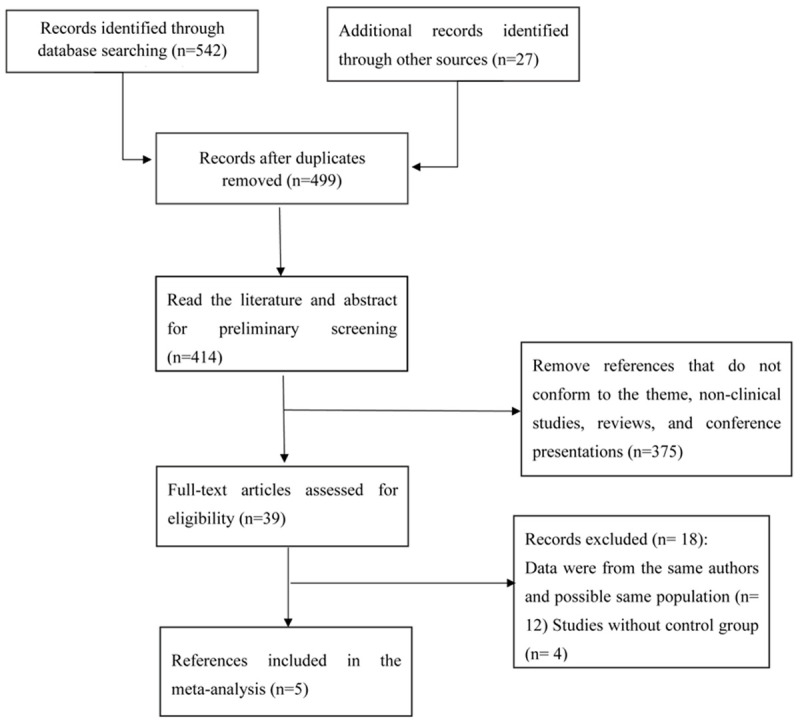

The detailed selection procedure is shown in Figure 1. The initial search using the search strategy produced a total of 569 articles. 155 studies were obtained after a careful examination. 39 publications were finally chosen with regard to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Five of them were included in the meta-analysis after a careful evaluation. Table 1 shows the basic information of the five included studies.

Figure 1.

Detailed flowchart for selecting the studies.

Table 1.

Basic information on the included studies

| First author | Year | Country | Research type | Controls/Cases | NOS score | Diagnostic method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Ganguli [27] | 2000 | America | retrospective | 4450/886 | 9 | DSM |

| Arjen JC Slooter [30] | 1998 | Netherland | retrospective | 997/97 | 8 | DRS |

| Scott C. Neu [31] | 2017 | Canada | prospective | 9279/10485 | 8 | DSM |

| Xiao Y. Dai [32] | 1994 | Japan | retrospective | 186/176 | 7 | DRM |

| R Katzman [33] | 1997 | China | retrospective | 363/103 | 7 | MMSE |

The number of alleles and genotype-positive cases corresponding to the case and control groups in each study (Table 2)

Table 2.

The OR values of the 6 genotypes and three alleles within the case and control groups in each study

| Study | Year | Groups | ε2/ε2 | ε2/ε3 | ε2/ε4 | ε3/ε3 | ε3/ε4 | ε4/ε4 | ε2 | ε3 | ε4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Ganguli | 2000 | Controls | 13 | 290 | 33 | 3515 | 577 | 22 | 178 | 3961 | 312 |

| Cases | 2 | 103 | 16 | 595 | 159 | 11 | 62 | 726 | 97 | ||

| Arjen JC Slooter | 1998 | Controls | 10 | 148 | 19 | 563 | 241 | 16 | 157 | 558 | 256 |

| Cases | 0 | 6 | 2 | 55 | 31 | 3 | 6 | 51 | 31 | ||

| Scott C. Neu | 2017 | Controls | 46 | 1061 | 203 | 5468 | 2257 | 244 | - | - | - |

| Cases | 15 | 421 | 288 | 3578 | 4641 | 1542 | - | - | - | ||

| Xiao Y. Dai | 1994 | Controls | 0 | 5 | 2 | 71 | 14 | 1 | 7 | 161 | 18 |

| Cases | 0 | 3 | 0 | 35 | 45 | 5 | 3 | 118 | 55 | ||

| OR | 0.33 | 0.62 | 1.47 | 0.52 | 2.07 | 3.82 | 0.71 | 0.55 | 2.19 | ||

| 95% CI | 0.19-0.57 | 0.18-2.11 | 0.87-2.48 | 0.36-0.75 | 1.40-3.06 | 1.86-7.84 | 0.19-2.58 | 0.35-0.86 | 1.38-3.48 | ||

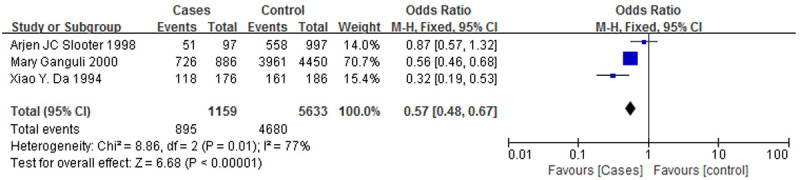

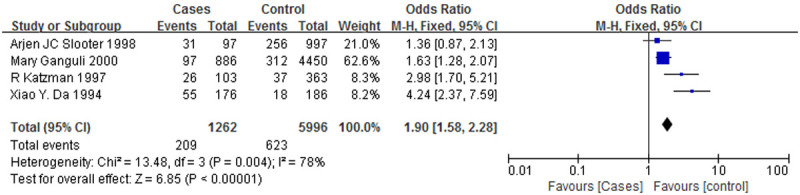

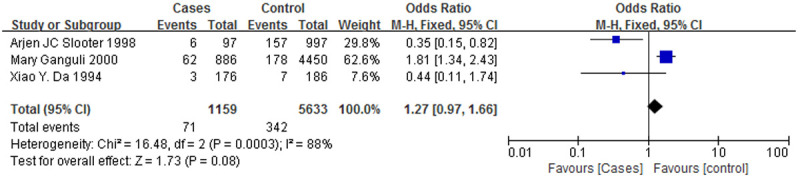

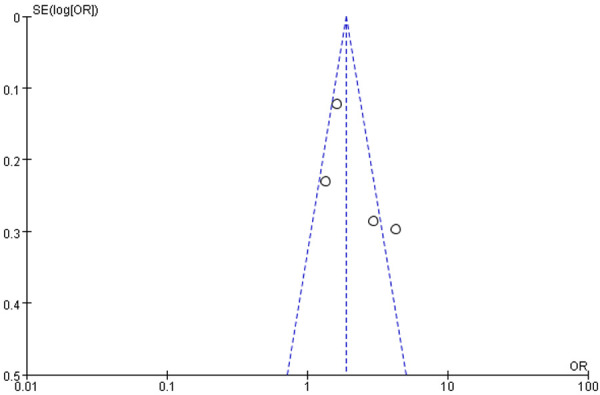

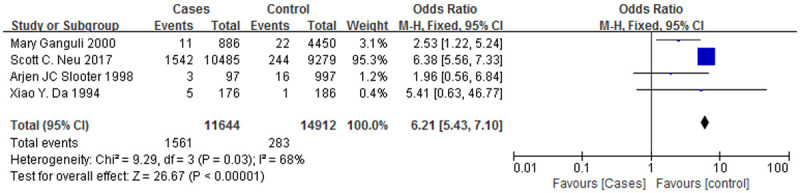

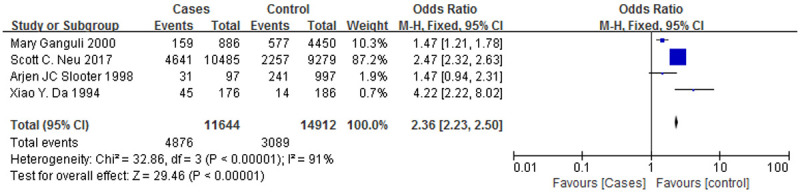

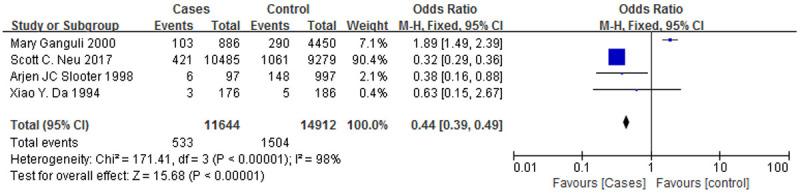

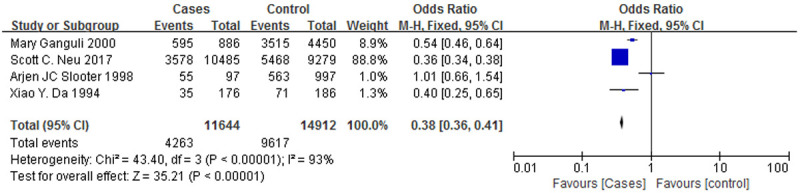

Figure 2 is a forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε3 allele and AD, and Figure 3 is a forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε4 allele and AD. It was clear that the ε3 allele positivity rate was lower in patients with AD than in the normal controls (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.35-0.86). The AD patients had a higher rate of positivity for the ε4 allele (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.38-3.48), suggesting that the ε4 allele is a risk factor for AD. Figure 4 is a forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε2 allele and AD, which shows that there is no significant association between the ApoE ε2 allele and AD (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.19-2.58), but Figure 5 is a funnel plot of the association between the ApoE ε4 allele and AD.

Figure 2.

A forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε3 allele and AD.

Figure 3.

A forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε4 allele and AD.

Figure 4.

A forest plot of the association between the ApoE ε2 allele and AD.

Figure 5.

A funnel plot of the association between the ApoE ε4 allele and AD.

The positive rate for the ApoE ε4 allele is higher in individuals with AD than in normal individuals

Table 3 shows the number of positive cases and the corresponding positivity rates of the ApoE ε4 allele in the control and case groups in each study. The number of cases in each study that were positive for the ApoE ε4 allele was higher than it was the corresponding control group (P < 0.05). This is consistent with previous findings that people with AD have a higher positive rate for the ApoE ε4 allele than normal controls, and that the ApoE ε4 allele is a risk factor for AD.

Table 3.

The ApoE ε4 allele positive rates in the control and case groups among the studies

| Study | Groups | ApoE ε4+ | ApoE ε4- | Total | positive rate | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mary Ganguli | Controls | 312 | 4138 | 4450 | 7.011% | < 0.05 |

| Cases | 97 | 789 | 886 | 10.948% | ||

| Arjen JC Slooter | Controls | 256 | 741 | 997 | 25.67% | < 0.05 |

| Cases | 31 | 66 | 97 | 31.96% | ||

| R Katzman | Controls | 37 | 326 | 363 | 10.2% | < 0.05 |

| Cases | 26 | 77 | 103 | 25.4% | ||

| Xiao Y. Dai | Controls | 18 | 168 | 186 | 9.677% | < 0.05 |

| Cases | 55 | 121 | 176 | 31.25% |

Link between 6 genotypes and AD

Figure 6 is a forest plot of the association between the ε4/ε4 genotype and AD, and Figure 7 is a forest plot of the association between the ε3/ε4 genotype and AD. The case groups showed a higher ε4/ε4 genotype positive rate (OR = 3.82, 95% CI: 1.86-7.84) and a higher ε3/ε4 genotype positive rate (OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.40-3.06), and the correlations with AD were similar for both genotypes. However, Figures 8 and 9 are forest plots between the ε2/ε3 genotype (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.18-2.11), the ε3/ε3 genotype (OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36-0.75) and AD, respectively. The two genotypes, ε2/ε3 and ε3/ε3, have significantly lower positive rates among the case group than the control group, and it can also be said that patients who are positive for these two genotypes are less likely to suffer from AD.

Figure 6.

A forest plot of the ApoE ε4/ε4 genotypes associated with AD.

Figure 7.

A forest plot of the ApoE ε3/ε4 genotypes associated with AD.

Figure 8.

A forest plot of the ApoE ε2/ε3 genotypes associated with AD.

Figure 9.

A forest plot of the ApoE ε3/ε3 genotypes associated with AD.

Sensitivity analysis

After excluding the articles one by one, a meta-analysis was carried out on the remaining articles, and the combined OR values showed no significant changes, all of which were statistically significant.

Specificity analysis

The included literature in this study had the same design type, experimental purpose, and intervention measures, ensuring clinical homogeneity. If I2 ≥ 50% was calculated using the RevMan 5.3 software, it was considered that there was statistical heterogeneity among the various articles. Therefore, the random effects model was used to analyze the included data.

Discussion

The onset of AD is insidious, slow, and irreversible [12], so patients with the AD can only be treated with drugs, and there is no effective way to prevent it [13]. Once diagnosed, it can seriously affect one’s ability to learn and understand, resulting in a dramatic decline in quality of life. The morbidity and mortality rates of AD have been rising yearly in both developed and developing countries, so it has become a common public concern [14-16].

AD is characterized by deposits of amyloid plaques, so the detection of these plaques can be used to confirm the diagnosis [17]. There have been several studies that have found ApoE [18] present in the amyloid plaques in the brains of patients with AD. There have also been many studies demonstrating a link between Apo and AD, such as a significant increase in Apo levels, the release of large amounts of inflammatory factors, and a high susceptibility to atherosclerosis [19-21]. The systemic hardening of the blood vessels increases the likelihood of having AD or worsens the condition in patients already diagnosed with AD [22]. This meta-analysis therefore focused on studies exploring the connection between ApoE and AD, with the aim of expanding the sample size and increasing the credibility.

Of all the apolipoprotein alleles, ε4 is the most studied and is considered the strongest risk factor for AD [23], as confirmed by the results of the present meta-analysis, namely a high positivity rate of the ε4 allele was observed in patients with AD (OR = 2.19, 95% CI: 1.38-3.48). We also found that the patients with AD had a lower positive rate for the ε3 allele (OR = 0.55, 95% CI: 0.35-0.86), but there was no significant association between the ApoE ε2 allele and AD (OR = 0.71, 95% CI: 0.19-2.58). The positivity rates of the ε4/ε4 and ε3/ε4 genotypes were significantly higher in the case group (OR = 3.82, 95% CI: 1.86-7.84; OR = 2.07, 95% CI: 1.40-3.06), but the positivity rates of the ε2/ε3 and ε3/ε3 genotypes were significantly lower than they were in the control group (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.18-2.11; OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.36-0.75). The studies found that the ApoE ε4 allele significantly increases the risk of AD, and the higher the number of this gene, the higher the prevalence of AD [24,25]. It has also been shown that the ApoE ε3 allele decreases the risk of AD [26]. The present meta-analysis is consistent with the results of the previous studies, and the possible mechanism is that different phenotypes of the ApoE gene can participate in the immune regulation of the nervous system, among which the immune response of the central nervous system induced by ε4+ is stronger than the immune response induced by ε3+, and the excessive immune response further leads to brain damage, thus causing AD [27].

In conclusion, the various alleles and six genotypes of ApoE have positive and negative differences among Alzheimer’s patients and normal individuals [28], and these differences undoubtedly provide direction for AD treatment, providing a possibility of genetically curing this disease, or even preventing it [29].

The present meta-analysis also has some shortcomings, such as not exploring the association between the ApoE alleles, genotypes, and AD separately by country and gender, and not categorizing AD as LOAD and EOAD. In addition, the diagnosis of AD is inconsistent, leading to possible errors. Research on the relationship between ApoE and AD is continuing, and it is expected to become a breakthrough point in the prevention and treatment of AD.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81904266 and No. 81973796).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Zurutuza L, Verpillat P, Raux G, Hannequin D, Puel M, Belliard S, Michon A, Pothin Y, Camuzat A, Penet C, Martin C, Brice A, Campion D, Clerget-Darpoux F, Frebourg T. APOE promoter polymorphisms do not confer independent risk for Alzheimer’s disease in a French population. Eur J Hum Genet. 2000;8:713–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zou T, Chen W, Zhou X, Duan Y, Ying X, Liu G, Zhu M, Pari A, Alimu K, Miao H, Kabinur K, Zhang L, Wang Q, Duan S. Association of multiple candidate genes with mild cognitive impairment in an elderly Chinese Uygur population in Xinjiang. Psychogeriatrics. 2019;19:574–583. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu X, Borenstein AR, Zheng Y, Zhang W, Seidner DL, Ness R, Murff HJ, Li B, Shrubsole MJ, Yu C, Hou L, Dai Q. Ca:Mg ratio, APOE cytosine modifications, and cognitive function: results from a randomized trial. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75:85–98. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dekosky ST, Gandy S. Environmental exposures and the risk for Alzheimer disease: can we identify the smoking guns? JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:273–275. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.6031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang L, Wang H, Abel GM, Storm DR, Xia Z. The effects of gene-environment interactions between cadmium exposure and apolipoprotein E4 on memory in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Toxicol Sci. 2020;173:189–201. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfz218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zuo L, van Dyck CH, Luo X, Kranzler HR, Yang BZ, Gelernter J. Variation at APOE and STH loci and Alzheimer’s disease. Behav Brain Funct. 2006;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zulfiqar S, Fritz B, Nieweg K. Episomal plasmid-based generation of an iPSC line from an 83-year-old individual carrying the APOE4/4 genotype: i10984. Stem Cell Res. 2016;17:523–525. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou Z, Shen Q, Pang Y, Li X, Chen Y, Wang X, Luo X, Wu Z, Bao Z, Zhang J, Liang J, Kong L, Yan L, Xiong L, Zhu T, Yuan S, Wang M, Cai K, Yao Y, Wu J, Jiang Y, Liu H, Liu J, Zhou Y, Dong Q, Wang W, Zhu K, Li L, Lou Y, Wang H, Li Y, Lin H. The synthesized transporter K16APoE enabled the therapeutic HAYED peptide to cross the blood-brain barrier and remove excess iron and radicals in the brain, thus easing Alzheimer’s disease. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2019;9:394–403. doi: 10.1007/s13346-018-0579-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walton RL, Soto-Ortolaza AI, Murray ME, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Ogaki K, Heckman MG, Rayaprolu S, Rademakers R, Ertekin-Taner N, Uitti RJ, van Gerpen JA, Wszolek ZK, Smith GE, Kantarci K, Lowe VJ, Parisi JE, Jones DT, Savica R, Graff-Radford J, Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Graff-Radford NR, Ferman TJ, Dickson DW, Boeve BF, Ross OA, Labbé C. TREM2 p.R47H substitution is not associated with dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurol Genet. 2016;2:e85. doi: 10.1212/NXG.0000000000000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zou F, Gopalraj RK, Lok J, Zhu H, Ling IF, Simpson JF, Tucker HM, Kelly JF, Younkin SG, Dickson DW, Petersen RC, Graff-Radford NR, Bennett DA, Crook JE, Younkin SG, Estus S. Sex-dependent association of a common low-density lipoprotein receptor polymorphism with RNA splicing efficiency in the brain and Alzheimer’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:929–935. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zulfiqar S, Garg P, Nieweg K. Contribution of astrocytes to metabolic dysfunction in the Alzheimer’s disease brain. Biol Chem. 2019;400:1113–1127. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2019-0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zunarelli E, Nicoll JA, Graham DI. Presenilin-1 polymorphism and amyloid beta-protein deposition in fatal head injury. Neuroreport. 1996;8:45–48. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199612200-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zúñiga Santamaría T, Yescas Gómez P, Fricke Galindo I, González González M, Ortega Vázquez A, López López M. Pharmacogenetic studies in Alzheimer disease. Neurologia. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.nrleng.2018.03.022. S0213-4853(18)30156-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brookhouser N, Zhang P, Caselli R, Kim JJ, Brafman DA. Generation and characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) lines from an Alzheimer’s disease (ASUi003-A) and non-demented control (ASUi004-A) patient homozygous for the Apolipoprotein e4 (APOE4) risk variant. Stem Cell Res. 2017;25:266–269. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2017.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brookhouser N, Zhang P, Caselli R, Kim JJ, Brafman DA. Generation and characterization of human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) lines from an Alzheimer’s disease (ASUi001-A) and non-demented control (ASUi002-A) patient homozygous for the Apolipoprotein e4 (APOE4) risk variant. Stem Cell Res. 2017;24:160–163. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brookes KJ, McConnell G, Williams K, Chaudhury S, Madhan G, Patel T, Turley C, Guetta-Baranes T, Bras J, Guerreiro R, Hardy J, Francis PT, Morgan K. Genotyping of the Alzheimer’s disease genome-wide association study index single nucleotide polymorphisms in the brains for dementia research cohort. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;64:355–362. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brookhouser N, Zhang P, Caselli R, Kim JJ, Brafman DA. Generation and characterization of two human induced pluripotent stem cell (hiPSC) lines homozygous for the Apolipoprotein e4 (APOE4) risk variant-Alzheimer’s disease (ASUi005-A) and healthy non-demented control (ASUi006-A) Stem Cell Res. 2018;32:145–149. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Broce IJ, Tan CH, Fan CC, Jansen I, Savage JE, Witoelar A, Wen N, Hess CP, Dillon WP, Glastonbury CM, Glymour M, Yokoyama JS, Elahi FM, Rabinovici GD, Miller BL, Mormino EC, Sperling RA, Bennett DA, McEvoy LK, Brewer JB, Feldman HH, Hyman BT, Pericak-Vance M, Haines JL, Farrer LA, Mayeux R, Schellenberg GD, Yaffe K, Sugrue LP, Dale AM, Posthuma D, Andreassen OA, Karch CM, Desikan RS. Dissecting the genetic relationship between cardiovascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;137:209–226. doi: 10.1007/s00401-018-1928-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zollo A, Allen Z, Rasmussen HF, Iannuzzi F, Shi Y, Larsen A, Maier TJ, Matrone C. Sortilin-related receptor expression in human neural stem cells derived from Alzheimer’s disease patients carrying the APOE epsilon 4 allele. Neural Plast. 2017;2017:1892612. doi: 10.1155/2017/1892612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zokaei N, Grogan J, Fallon SJ, Slavkova E, Hadida J, Manohar S, Nobre AC, Husain M. Short-term memory advantage for brief durations in human APOE ε4 carriers. Sci Rep. 2020;10:9503. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-66114-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zokaei N, Čepukaitytė G, Board AG, Mackay CE, Husain M, Nobre AC. Dissociable effects of the apolipoprotein-E (APOE) gene on short- and long-term memories. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;73:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Briels CT, Stam CJ, Scheltens P, Bruins S, Lues I, Gouw AA. In pursuit of a sensitive EEG functional connectivity outcome measure for clinical trials in Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neurophysiol. 2020;131:88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2019.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klein RC, Mace BE, Moore SD, Sullivan PM. Progressive loss of synaptic integrity in human apolipoprotein E4 targeted replacement mice and attenuation by apolipoprotein E2. Neuroscience. 2010;171:1265–1272. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.10.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brickell KL, Steinbart EJ, Rumbaugh M, Payami H, Schellenberg GD, Van Deerlin V, Yuan W, Bird TD. Early-onset Alzheimer disease in families with late-onset Alzheimer disease: a potential important subtype of familial Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1307–1311. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.9.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bretsky PM, Buckwalter JG, Seeman TE, Miller CA, Poirier J, Schellenberg GD, Finch CE, Henderson VW. Evidence for an interaction between apolipoprotein E genotype, gender, and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1999;13:216–221. doi: 10.1097/00002093-199910000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bridel C, Hoffmann T, Meyer A, Durieux S, Koel-Simmelink MA, Orth M, Scheltens P, Lues I, Teunissen CE. Glutaminyl cyclase activity correlates with levels of Aβ peptides and mediators of angiogenesis in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9:38. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0266-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ganguli M, Chandra V, Kamboh MI, Johnston JM, Dodge HH, Thelma BK, Juyal RC, Pandav R, Belle SH, DeKosky ST. Apolipoprotein E polymorphism and Alzheimer disease: the Indo-US Cross-National Dementia Study. Arch Neurol. 2000;57:824–830. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.6.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleinschmidt M, Schoenfeld R, Göttlich C, Bittner D, Metzner JE, Leplow B, Demuth HU. Characterizing aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia with blood-based biomarkers and neuropsychology. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50:111–126. doi: 10.3233/JAD-143189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klimentidis YC, Raichlen DA, Bea J, Garcia DO, Wineinger NE, Mandarino LJ, Alexander GE, Chen Z, Going SB. Genome-wide association study of habitual physical activity in over 377,000 UK Biobank participants identifies multiple variants including CADM2 and APOE. Int J Obes (Lond) 2018;42:1161–1176. doi: 10.1038/s41366-018-0120-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slooter AJ, Cruts M, Kalmijn S, Hofman A, Breteler MM, Van Broeckhoven C, van Duijn CM. Risk estimates of dementia by apolipoprotein E genotypes from a population-based incidence study: the Rotterdam study. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:964–968. doi: 10.1001/archneur.55.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neu SC, Pa J, Kukull W, Beekly D, Kuzma A, Gangadharan P, Wang LS, Romero K, Arneric SP, Redolfi A, Orlandi D, Frisoni GB, Au R, Devine S, Auerbach S, Espinosa A, Boada M, Ruiz A, Johnson SC, Koscik R, Wang JJ, Hsu WC, Chen YL, Toga AW. Apolipoprotein E genotype and sex risk factors for Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:1178–1189. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dai XY, Nanko S, Hattori M, Fukuda R, Nagata K, Isse K, Ueki A, Kazamatsuri H. Association of apolipoprotein E4 with sporadic Alzheimer’s disease is more pronounced in early onset type. Neurosci Lett. 1994;175:74–76. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)91081-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katzman R, Zhang MY, Chen PJ, Gu N, Jiang S, Saitoh T, Chen X, Klauber M, Thomas RG, Liu WT, Yu ES. Effects of apolipoprotein E on dementia and aging in the Shanghai survey of dementia. Neurology. 1997;49:779–785. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.3.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]