Abstract

B52, an essential SR protein of Drosophila melanogaster, stimulates pre-mRNA splicing in splicing-deficient mammalian S100 extracts. Surprisingly, mutant larvae depleted of B52 were found to be capable of splicing at least several pre-mRNAs tested (H. Z. Ring and J. T. Lis, Mol. Cell. Biol. 14:7499–7506, 1994). In a homologous in vitro system, we demonstrated that B52 complements a Drosophila S100 extract to allow splicing of a Drosophila fushi tarazu (ftz) mini-pre-mRNA. Moreover, Kc cell nuclear extracts that were immunodepleted of B52 lost their ability to splice this ftz pre-mRNA. In contrast, splicing of this same ftz pre-mRNA occurred in whole larvae homozygous for the B52 deletion. Other SR protein family members isolated from these larvae could substitute for B52 splicing activity in vitro. We also observed that SR proteins are expressed variably in different larval tissues. B52 is the predominant SR protein in specific tissues, including the brain. Tissues in which B52 is normally the major SR protein, such as larval brain tissue, failed to produce ftz mRNA in the B52 deletion line. These observations support a model in which the lethality of the B52 deletion strain is a consequence of splicing defects in tissues in which B52 is normally the major SR protein.

Many genes are interrupted by introns that are removed in the process of making a functional mRNA and, ultimately, a protein product. This splicing process takes place in a megadalton RNA-protein complex termed the spliceosome. The spliceosome consists of many components, including five small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles (snRNPs) each consisting of a small nuclear RNA and a complement of proteins (17). Additionally, 100 or more non-snRNP proteins are present in the spliceosome (23).

One group of non-snRNP proteins that has been studied intensively since their discovery is the SR protein family (8). SR proteins have a similar protein structure, with at least one RNA recognition motif (RRM) at the N terminus and a region rich in arginine-serine dipeptides (RS domain) at the C terminus. The RRM consists of 80 to 90 amino acids; is present in many RNA-binding proteins, including members of the SR protein family; and confers RNA binding specificity (13, 20). The RS domain has been postulated to mediate protein-protein interactions between SR family members (15, 39, 40). The SR protein family includes proteins with sizes of 20, 30, 40, 55, and 75 kDa, and the high degree of conservation from Drosophila to humans indicates the importance of these proteins (8). This family of SR proteins, purified by a two-step salt precipitation procedure, has a well-defined biochemical activity, such that each member can complement a splicing-deficient cytoplasmic (S100) extract, indicative of a functional redundancy among SR proteins.

In Drosophila melanogaster, only two SR proteins, RBP1 and B52, have been cloned and characterized to date. RBP1, homologous to human SRp20, is expressed in all tissues throughout development and colocalizes with RNA polymerase II on larval salivary gland polytene chromosomes. RBP1 also tested positive for splicing activity in a cell-free human splicing system (14). B52, the Drosophila homolog of human SRp55 is present during all stages of development and was initially characterized because of its localization to heat shock puffs on polytene chromosomes. B52 brackets RNA polymerase at the largest heat shock puffs and stains within developmental puffs (4, 18). The proper level of expression of B52 is critical for development of the animal. Overexpression of B52 in various tissues results in developmental arrest in almost all cases (18). The generation of a B52-null mutant showed that B52 expression was essential, given that these animals do not develop past the second-instar larval stage. Surprisingly, several genes analyzed thus far show proper splicing patterns in arrested larvae of the B52-null mutant (22, 24). Thus, a global RNA processing defect may not explain the lethality of the B52 deletion mutation.

In order to understand the cause of the lethality of the null mutation, we sought to characterize more thoroughly the splicing activity of B52 in vivo and in vitro. Here, we show that B52 is essential for splicing an ftz pre-mRNA in Drosophila extracts in which B52 is the predominant SR protein. In vivo, other SR proteins appear to complement the B52 deficiency in most tissues. However, by analyzing RNA isolated from the brain, a tissue in which B52 is the major SR protein expressed, we showed that the production of ftz mRNA is dependent on B52. These results support the hypothesis that the lethality seen in the B52-null mutant is a consequence of splicing defects in tissues that lack sufficient concentrations of other SR protein family members.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Northern blot analysis.

RNAs were transferred to a Gene Screen Plus membrane (Dupont) by using a Trans-Blot apparatus (Bio-Rad). The membrane was prewashed and hybridized at 42°C, in a solution containing 20% formamide, 10% dextran sulfate, and 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate), with 250 μl of salmon testis DNA (10 mg/ml) and 5 × 106 cpm of a 32P-labeled, kinase-treated oligonucleotide (5′-AGTCTTTGCAATCTGATGCCAAAG). The membrane was washed twice in 6× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for 20 min at room temperature and once in 6× SSC prior to exposure for autoradiography.

In vitro splicing assay.

The ftz pre-mRNA substrate was synthesized in 50-μl reaction volumes containing the following: 0.04 mg of template DNA/ml; T7 RNA polymerase; 0.5 mM diguanosine triphosphate; 0.4 mM each ATP, CTP, and GTP; 0.3 mM UTP; and 5 μl of [32P]UTP (NEN 007H). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 30 min. The template DNA was removed by a DNase digestion, and free nucleotides were removed by using a Sephadex G50 spin column. The RNA was extracted with phenol and chloroform and then precipitated with ethanol. Nuclear and cytoplasmic (S100) extracts were made from Kc cells (6). In vitro splicing reaction mixtures, consisting of nuclear extract or S100 supplemented with B52, were assembled as described previously (25), and reactions were carried out at 20°C for 90 min. The resulting RNAs were treated with proteinase K (0.6 mg/ml) for 10 min at 30°C and purified by a phenol-chloroform extraction followed by an ethanol precipitation. The RNAs were separated on a 6% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel.

Immunoblot analysis.

Proteins separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel (10 or 12.5%) were transferred to nitrocellulose filters (Schleicher & Schuell). The filters were blocked in Tris-buffered saline containing 3% gelatin and 10% calf serum, washed, and incubated with primary antibody (0.15 μg of the RRM antibody [18] or the mAb104 antibody [27]/ml) in 1% gelatin containing 10% calf serum. The filters were washed again, incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse immunoglobulin G (Amersham), and processed by chemiluminescence according to the directions of the manufacturer. Frozen Drosophila larvae or dissected tissues were ground to a fine powder and sonicated in isolation buffer (41). The proteins from whole larvae were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 20 min, while the proteins from tissues were spun at 13,000 × g for 5 min. The supernatants were collected, and aliquots were loaded on a gel.

D. melanogaster transformation.

The ftz pre-mRNA substrate was subcloned into the pUAST transformation vector (1) to produce the plasmid UASgal-ftz. UASgal-ftz was introduced into the B52 deletion fly line (B5228/TM6b Tb e) by P-element-mediated germ line transformation (26, 29, 33). An insertion into the B5228 third chromosome was identified and confirmed by segregation analysis of chromosomes. To produce ftz pre-mRNA, these flies were crossed with a strain that uses the hsp70 promoter to express GAL4.

RT-PCR.

RNA isolation and reverse transcription (RT)-PCR of whole larvae were performed as described previously (24). The following gene-specific primer pairs were used for: ftz, 5′-AACTGCAGGTCGACTACTTGGACGTCTACTCGC and 5′-CGGGATCCCTCGAGCTCCAGGGTCTGGT; for B52, 5′-AAGGAAGCGTTATCATGGTGGGA and 5′-GGATGTCGCGTGTGCGGCCGTATC; and for Hsp70, 5′-AAGGACAACAATGCATTGGGC and 5′-GCTGGCCGCAGTTTGCTCCCGG. All samples were treated with DNase to eliminate any possible DNA contamination of the RNA preparation. Larval dissections were performed in Ringer's solution (110 mM NaCl, 4 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.2]), and the isolated tissues were frozen immediately on dry ice. Carrier tRNA (10 μg) was added, and RNA was isolated as described above. The RNA was reverse transcribed as described above except that random hexamers were used as primers. Ten percent of the RT product served as the template for the PCR, which was kept in the linear range of amplification using primers for the ftz gene as well as 18S rRNA internal standards (Ambion). The products were separated on a 4% polyacrylamide–7 M urea gel.

Protein preparations. (i) B52.

B52 was prepared as described previously (32).

(ii) RBP1.

RBP1 was purified by Ni2+ chelate chromatography as described elsewhere (14).

(iii) SR proteins.

SR protein preparation was performed as described elsewhere (41) with the following modification. After ammonium sulfate precipitation, gel filtration was carried out instead of dialysis, with G25 resin (Sigma) being used to rapidly desalt the proteins.

RESULTS

B52 activity in a Drosophila in vitro splicing system.

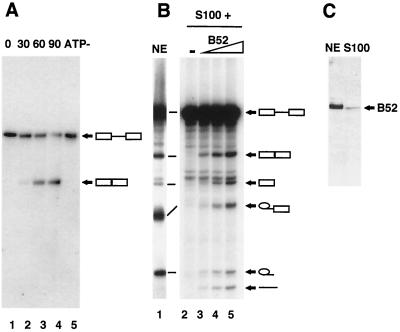

We characterized the splicing activity of B52 by using a homologous Drosophila in vitro splicing system composed of a mini-pre-mRNA substrate from the Drosophila fushi tarazu gene (ftz) (25) and nuclear extract prepared from a Drosophila cell line (Kc). Northern blotting with an exon junction oligonucleotide probe was used to identify the spliced ftz RNA produced in the splicing reaction. This probe consists of 12 nucleotides from the 3′ end of exon 1 joined to 12 nucleotides from the 5′ end of exon 2. Therefore, it will label the mRNA preferentially over the pre-mRNA, other splicing intermediates, or the 5′ exon product due to the increase in hybridization possible with the mRNA and the radiolabeled oligonucleotide. The junction oligonucleotide hybridized to the mRNA and, weakly, to the pre-mRNA during a splicing time course (Fig. 1A, lanes 2 to 4). Production of the mRNA was dependent on the presence of ATP and incubation at the splicing temperature (lanes 5 and 1), and the product was of the expected size. This assay identifies the mRNA not only by size but by sequence identity and demonstrates the fidelity of the in vitro Drosophila splicing system used in our laboratory.

FIG. 1.

B52 functions as an in vitro splicing factor in a homologous Drosophila splicing system. (A) Identification of the ftz mRNA by Northern blotting with an exon junction oligonucleotide as the probe. A splicing time course is shown, with either 0 (lane 1), 30 (lane 2), 60 (lane 3), or 90 (lane 4) min under splicing conditions. A control reaction without ATP (ATP−) is also shown (lane 5). The junction oligonucleotide probe identifies the mRNA and also the pre-mRNA (although much more weakly). Even though the signals look comparable, the amount of pre-mRNA on the blot is much larger than the amount of mRNA (see Fig. 2 for an example). (B) The ftz pre-mRNA substrate was uniformly radiolabeled for these reactions. The splicing activities of nuclear extract (NE) and uncomplemented S100 extract (−) are shown (lanes 1 and 2, respectively). S100 extract was complemented with 0.25 (lane 3), 0.5 (lane 4), or 1 (lane 5) μg of B52 produced in a baculovirus expression system. Diagrams of the splicing products and intermediates are shown on the right, where boxes represent exons and lines represent introns. (C) Western blot prepared by using the RRM antibody, indicating the relative amounts of B52 present in the nuclear extract and S100.

One characteristic of SR proteins is that they can complement the splicing-deficient S100 extract to restore splicing activity (8). B52 has been previously shown to have this activity in a human cell-free system (21). We sought to determine whether B52 had a similar activity in the Drosophila splicing system. For this and the following in vitro splicing experiments, the pre-mRNA substrate was uniformly labeled with [32P]UTP. The splicing-deficient S100 extract (Fig. 1B, lane 2) was complemented by B52, yielding spliced mRNA (lanes 3 to 5). The spliced products and splicing intermediates were produced in larger amounts as B52 was titrated into the reaction. We found that the splicing activities of the Kc nuclear and S100 extracts differed greatly (compare lanes 1 and 2 in Fig. 1B). Since addition of SR protein restored splicing activity to the S100 extract, a lack of SR proteins in the S100 line is the probable cause of the deficiency. An alternative explanation is the presence of a splicing inhibitor in the S100 extract. We examined the levels of B52 in these two extracts by Western blotting with the anti-B52RRM antibody (18). This antibody is specific for B52 and does not recognize other RRM-containing proteins (18). As expected, there was much less B52 present in the S100 extract than in the nuclear extract (Fig. 1C). A similar result was seen with fractionation studies in mammalian systems, which explained the splicing deficiency of S100 (16). The results found here with Drosophila components are consistent with what has been previously observed in mammalian systems.

B52 is an essential splicing factor.

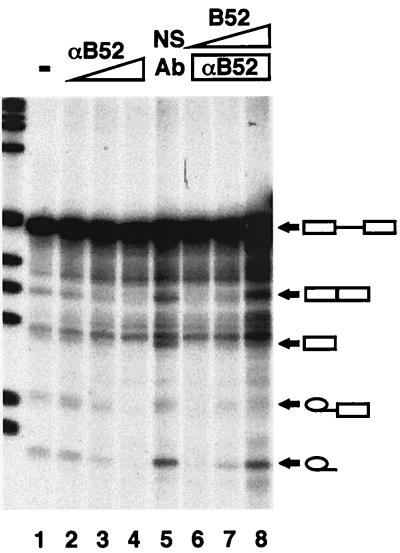

Antibodies have been useful tools in the study of splicing factors. In the initial characterization of two mammalian SR proteins (9G8 and SC35), antibodies were used to show that these proteins are essential splicing factors (3, 9). These authors showed that titrating increasing amounts of antibody against one of these specific splicing factors decreased splicing activity, presumably because the antibody bound to the corresponding splicing factor and prevented it from functioning. We used the RRM antibody to test whether B52 could be functionally inhibited in a similar fashion. Although the splicing efficiency in this experiment was less than we generally observe, it was clear that splicing activity could be seen in a reaction using nuclear extract and in a control reaction in which a nonrelevant antibody was added (Fig. 2, lanes 1 and 5, respectively). The addition of increasing amounts of antibody resulted in a gradual reduction of both the spliced products and splicing intermediates until splicing inhibition became virtually complete (lanes 2 to 4). The inhibition of splicing intermediates suggests that the antibody inhibits B52 function early in the splicing reaction, as proposed previously for SR proteins (35). The addition of increasing amounts of baculovirus-produced B52 to the antibody-inhibited reaction restored splicing activity (lanes 6 to 8). This recovery of splicing activity indicates that the inhibitory action of the antibody is specific for B52 and that B52, like mammalian SR proteins, plays an important role in the splicing reaction.

FIG. 2.

B52 is required for ftz pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. The resultant RNAs from a splicing reaction using uninhibited nuclear extract (−) are shown (lane 1). Increasing amounts of RRM antibody (αB52) were added to splicing reactions (lanes 2 to 4), causing a loss of splicing activity compared to a reaction in which a nonspecific antibody (NS Ab) was used (lane 5). The RRM antibody was added to splicing reactions, as well as increasing amounts of B52 (0.25, 0.5, and 1 μg) (lanes 6 to 8, respectively). The size markers to the left are the 1-kb ladder (Gibco BRL).

B52 is not essential for splicing in whole larvae.

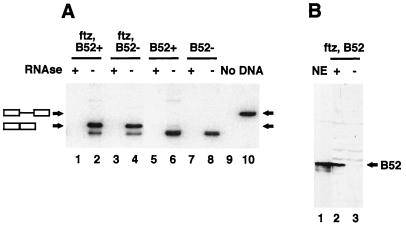

Since B52 is a necessary splicing factor when assayed in vitro, we took advantage of the B52 deletion fly strain to analyze the RNA splicing requirement for B52 in the organism. The same ftz pre-mRNA was joined to a promoter that contains a regulatory protein binding site (UASgal) for the positive yeast activator protein GAL4 (1) and introduced into the B52 deletion fly line (B5228/TM6b Tb e) by germ line transformation (see Materials and Methods). Crossing the UASgal-ftz-containing transformant line with a GAL4-expressing line provided a means of producing the ftz pre-mRNA in the larvae. The B52 deletion, balanced over the dominant balancer (Tm6B), allows the hand selection of larvae containing one copy of the complete B52 gene (for simplicity, these larvae will be called B52+). These larvae have a tubby phenotype and are easily separable from the nontubby larvae homozygous for the B52 deletion (B52− larvae) (24).

An inducible gene has a distinct advantage over an endogenous gene in analyses. If the RNA from an endogenous gene is stable, then all or a portion of the spliced product detected may have been processed before B52 became limiting in the larva. By using an inducible gene, expression of the gene is turned on after B52 has already been depleted, ensuring that any processing has occurred in the absence of B52. The RNA from B52+ and B52− larvae expressing the ftz transgene was assayed by RT-PCR (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 4). These results showed that the ftz pre-mRNA was efficiently spliced in both groups of larvae (compare lanes 2 and 4). Treatment of the RNA preparations with RNase before the RT reaction eliminated PCR products (compare lanes 1 and 3 with lanes 2 and 4), while a pretreatment with DNase had no effect. This control confirms that the ftz mRNA identified in the assay was amplified from RNA. RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from larvae without the ftz transgene showed endogenous expression of the ftz gene to cause no background (lanes 5 to 8). Since a splicing effect in the B52− larvae was not observed, it was necessary to show that the B52− selected larvae were depleted of B52. Western blots of proteins (4 μg total) prepared from larvae confirmed that there was no detectable B52 present in the B52− larvae (Fig. 3B; compare lanes 2 and 3). These results demonstrate that B52 is not necessary to splice the ftz pre-mRNA in whole second-instar larvae.

FIG. 3.

Significant splicing of the ftz pre-mRNA occurs in larvae lacking the B52 gene. (A) RT-PCR analysis of RNA isolated from larvae expressing the ftz transgene and containing (ftz, B52+) (lanes 1 and 2) or lacking (ftz, B52−) (lanes 3 and 4) a complete B52 gene. Results of a similar analysis for RNA isolated from larvae without the transgene are shown to determine the endogenous ftz levels (lanes 5 to 8). The RNA in lanes 1, 3, 5, and 7 was treated with RNase and then subjected to RT-PCR. A control reaction without RNA (No) (lane 9) and a reaction using a plasmid containing the ftz pre-mRNA to indicate the position of the pre-mRNA (DNA) (lane 10) are also shown. The band below the mRNA is not dependent on the ftz transgene and is not always observed. −, no RNase added. (B) Western blot prepared by using the RRM antibody, indicating the amount of B52 present in ftz B52+ (lane 2) and ftz B52− (lane 3) larvae; nuclear extract (NE) (lane 1) is shown for comparison.

Other SR proteins may complement the B52 deletion to retain splicing activity.

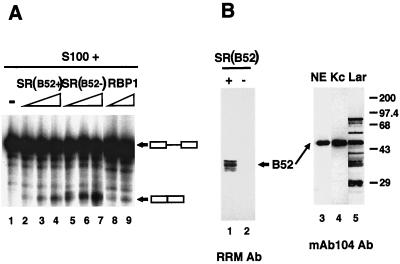

One simple hypothesis to explain ftz mRNA production in B52− larvae is that in larvae there are other SR proteins present that can complement the B52 deletion for general splicing activity. To test this hypothesis, we prepared SR proteins from hand-selected B52+ and B52− larvae. Equal amounts of protein from the two SR protein preparations were titrated in the splicing reaction. Both SR preparations complemented the S100 extract such that splicing of the ftz pre-mRNA occurred in vitro (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 to 7). The B52− SR preparation even showed slightly more splicing activity than the B52+ preparation, probably due to subtle differences in the specific activities of the two preparations. Defective splicing activity of the S100 extract was evident (lane 1). Since both SR preparations were functional in this splicing assay, it was necessary to verify that the SR proteins from B52− larvae did not contain B52. Western blotting with the RRM antibody showed that the SR preparation from B52− larvae was devoid of B52 (Fig. 4B; compare lanes 1 and 2). Another Drosophila SR protein (RBP1), prepared in Escherichia coli, also complemented the S100 extract to generate splicing activity (Fig. 4A, lanes 8 and 9). These experiments demonstrate that other Drosophila SR proteins can complement the B52-deficient (S100) extract to splice the ftz pre-mRNA and provide a possible explanation for the presence of ftz mRNA in B52− larvae.

FIG. 4.

Larval SR proteins other than B52 rescue ftz splicing in vitro. (A) RNAs from splicing reactions of uncomplemented S100 (−) (lane 1) or S100 complemented with SR proteins purified from B52+ larvae (200, 400, or 600 ng) (lanes 2, 3, and 4, respectively) or B52− larvae (200, 400, or 600 ng) (lanes 5, 6, and 7, respectively) or RBP1 (250 or 500 ng) (lanes 8 and 9, respectively) are shown. (B) The left panel shows a Western blot of the SR protein preparations (4 μg) from B52+ (lane 1) and B52− (lane 2) larvae, prepared by using the RRM antibody (Ab). The right panel shows a Western blot, prepared using the SR protein-specific antibody mAb104, of nuclear extract (NE) prepared from Kc cells (lane 3), Kc cells (Kc) (lane 4), or proteins from B52+ larvae (Lar) (lane 5). Multiple proteins are present in the B52+ larvae, including different SR proteins and, most likely, their degradation products. The positions of protein molecular mass standards (in kilodaltons) are shown to the right.

The above-described experiment shows that other Drosophila SR proteins can stimulate the splicing of the ftz pre-mRNA. However, the B52 antibody was able to inhibit the splicing activity of Kc nuclear extract. To explain the results of these two experiments, we compared the SR protein compositions of Kc cells and larvae. The mAb104 antibody (27), which identifies members of the SR protein family through a phospho epitope of the RS domain, was used in Western blot analysis. Immunoreactivity to this antibody is diagnostic of SR proteins. Only B52 was detected in Kc cells (Fig. 4B, lanes 3 and 4). This result is not surprising, since an earlier study found B52 to be by far the most abundant protein present in Kc cells (28). The similarity of the SR protein profiles of nuclear extract and Kc cells indicates that the nuclear extract procedure does not alter the SR protein composition. In contrast, multiple SR proteins were identified in Drosophila larvae (lane 5). In addition to B52, we see the previously identified SR proteins with molecular masses of 75, 40, and 30 kDa (the 20-kDa SR family member was run off the gel) and several other bands, which may be breakdown products of these proteins. Taken together, these results suggest that other SR proteins can complement a lack of B52 in the developing larvae (Fig. 3 and 4A), but in Kc cells, in which B52 is the only SR protein present in an adequate quantity, this complementation cannot take place and splicing activity is lost when B52 is inactivated (Fig. 2).

B52 is essential for splicing activity in the larval brain.

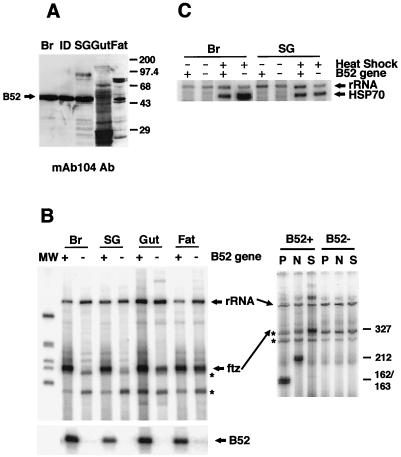

Given that in mouse, calf, and rat tissues, SR proteins are differentially expressed (11, 31, 42), we were prompted to examine whether there is in Drosophila larvae a specific tissue in which B52 is the major SR protein. In such a tissue, the function of B52 can be assayed without the background of other SR proteins, which may complement B52 function. Various tissues from 15 developing Drosophila larvae were dissected, and from them, proteins were prepared and then analyzed by Western blotting with the mAb104 antibody (Fig. 5A). B52 was the predominant SR protein found in the brain and imaginal discs. The other SR proteins identified in whole larvae were present in different tissues. The gut contained large amounts of the 30-kDa protein, fat bodies had the 75-kDa protein, while the 40-kDa protein was prevalent in the cuticle (data not shown). Since B52 is the only SR protein present in detectable quantities in the brain, and the tissue is not difficult to dissect, brain was the tissue chosen to assay the requirement for B52 in ftz pre-mRNA splicing.

FIG. 5.

B52 is necessary for the production of ftz mRNA in the B52− larval brain. (A) Fifteen larvae were dissected, like tissues were pooled, and proteins were prepared and separated on an SDS–12.5% polyacrylamide gel. Western analysis with the mAb104 antibody (Ab) shows the SR protein complement of brain (Br), imaginal disc (ID), salivary gland (SG), gut, and fat body (Fat). The mobilities of B52 and protein molecular mass standards (in kilodalton) are indicated. (B) (Left panel) Brain or salivary gland RNA was isolated from single B52+ (+) and B52− (−) larvae, and RT-PCR was performed. Shown and labeled are the PCR products for rRNA, ftz, and B52 separated on a 4% denaturing gel. The template DNA for all three PCRs came from the same RT reaction. Asterisks indicate nonspecific PCR products. MW, 32P-labeled 1-kb ladder (Gibco-BRL). (Right panel) Either the B52+ or B52− PCR product was digested with PvuII (P), NaeI (N), or SspI (S), and the digestion products were separated on a 8% denaturing gel. The expected sizes (in nucleotides) of the digestion products of ftz mRNA (shown to the right) are 162 and 163 with PvuII, 212 and 113 with NaeI, and 327 (uncut) with SspI. The 113-nucleotide NaeI digestion product was run off the bottom of the gel. (C) Transcription of newly induced Hsp70 mRNA occurs in B52− larvae. RT-PCR was performed with Hsp70-specific primers, using RNA isolated from the brain or salivary glands of B52+ and B52− larvae that were (+) or were not (−) subjected to heat shock.

Individual brains of B52+ and B52− larvae were dissected, and RNA was prepared. Other tissues were also dissected as controls, since the SR proteins other than B52 in these tissues should complement the lack of B52 in a B52− larva to produce ftz mRNA. To normalize the amount of RNA isolated from each tissue, rRNA primers were included in the PCR to serve as an internal control. The RT reaction was primed with random oligonucleotides to allow the analysis of both rRNA and the ftz transgene from the same RNA sample. ftz mRNA was observed in the B52+ larval brain but not in the B52− larva (Fig. 5B, left panel). This result was reproduced with RNA isolated from multiple brains. In all other tissues examined, ftz mRNA was observed at a reduced level in B52− larva (Fig. 5B, left panel), but this effect was most pronounced in salivary glands, where B52 makes up a larger percentage of the total SR protein present (Fig. 5A).

Since more bands than expected were observed in the experiment described above (marked by asterisks in Fig. 5B), the PCR products were subjected to restriction enzyme analysis to confirm the identity of ftz mRNA. The PCR product resulting from ftz RNA should be digested with PvuII and NaeI, which cut in an exon, but not with SspI, which recognizes a restriction site in the intron of the transgene. Both PvuII and NaeI yielded the expected digestion products, and SspI did not digest the PCR product from B52+ larvae, confirming its identity as ftz mRNA (Fig. 5B, right panel). These three enzymes did not digest any other bands present in the gel of the B52− larva RT-PCR product, indicating that these products were nonspecific. To verify that the B52− larva did not contain B52, PCR with oligonucleotides hybridizing within an exon of the B52 gene was used to show that B52 RNA was abundant only in the B52+ tissues (Fig. 5B, lower left panel). These experiments demonstrate that B52 is necessary for the production of this ftz mRNA in tissues in which it is the predominant SR protein expressed. By using an oligonucleotide pair that specifically amplifies across an intron-exon junction, we were able to detect the ftz pre-mRNA (data not shown). An increase in pre-mRNA was not observed in the B52− brain RNA. Presumably this RNA is not stable in the cell and is turned over, preventing its accumulation (5).

The transcription of genes in the B52− larvae is not compromised by this mutation. When whole larvae were assayed, we saw production of the mRNA in B52− larvae (Fig. 3), indicating that transcription of the ftz gene did occur. However, this analysis did not address whether the pre-mRNA was transcribed in the brain. To show that transcription in the brain of the B52 mutant larva was occurring, newly induced Hsp70 RNA was assayed by RT-PCR. By assaying a newly induced gene, it was determined that the bulk of the transcripts observed in the second-instar larva were made after B52 was depleted. Hsp70 mRNA was produced in response to heat shock in both the brain and salivary glands in the presence or absence of B52 (Fig. 5C). Although the heat shock induction was not as good in the B52+ larva, the experiment clearly showed that B52− larvae underwent transcription in the absence of B52. This result supports the interpretation that in B52− larval brains, ftz mRNA is not produced due to a splicing defect.

DISCUSSION

Many in vitro studies have shown that SR proteins function in pre-mRNA splicing (8, 35). Although some of the interactions of SR proteins with splicing factors have been defined in recent years, the role of these specific interactions needs further investigation. In addition to functioning as essential splicing factors, SR proteins can regulate alternative splice site choice. In splicing substrates with multiple splice sites, some SR proteins promote proximal splicing while others, or hnRNP A1, shift splicing to distal splice sites (10, 21, 43). Similar effects have been reproduced in tissue culture by overexpressing ASF/SF2 and hnRNP A1 in HeLa cells (2, 36). In addition, studies using the chicken B-cell line DT40 showed the SR protein ASF/SF2 to be essential, since targeted disruption of the gene resulted in a loss of cell viability (37). The depletion of ASF/SF2 in this cell line was shown to affect the splicing of a few specific transcripts (38). However, splicing studies in multicellular organisms have lagged behind these studies in cell culture and certainly those performed in vitro.

In this study, we characterized the splicing activity of B52 to investigate the lethal phenotype of the B52-null mutant. This is the only mutant of an SR family member studied in a whole organism. Using a Drosophila homologous in vitro splicing system, we demonstrated that B52 is an essential splicing factor. Given that finding a natural target gene has proven difficult, we introduced into Drosophila the ftz minigene splicing substrate, which we used successfully in vitro, to assay the splicing activity of B52 in vivo. Other SR proteins appear to complement the lack of B52 for splicing activity in whole B52− larvae. However, we found that B52 was the major SR protein expressed in the brain. In this tissue from B52− larvae, we detected no ftz mRNA, although the mRNA was observed in tissues in which SR proteins other than B52 are expressed. mRNA of the newly induced Hsp70 gene was detected, which demonstrates that RNA transcription functions in the brain of the B52− larva. These results, taken together, show that B52 functions in vivo as a critical splicing factor in tissues in which it is the predominant SR protein. The lethality of the B52 deletion mutant may be a consequence of splicing defects for specific genes in the brain, where other SR proteins cannot complement for the loss of B52.

In a previous study, flies homozygous for a P-element insertion in another Drosophila splicing factor showed severely reduced viability and bristle defects but no obvious splicing defects (30). Analogously, we also did not observe an effect on splicing in the B52 mutant when whole larvae were analyzed. However, since B52 is an essential gene, it has at least one particular function that other SR proteins cannot complement. We screened several genes and found that the B52− larvae were modestly defective (twofold) in the splicing of one of these, the dopa decarboxylase pre-mRNA (B. E. Hoffman and J. T. Lis, unpublished results). A distinct pre-mRNA substrate specificity (3, 7) and different alternative splicing patterns (42, 43) have been found for different SR proteins in mammalian systems. Such assays using synthetic RNA substrates are informative, but the identities of genes requiring a specific SR protein for proper processing remain elusive.

To analyze the issue of SR protein redundancy versus specificity more closely, in vitro selection was performed to identify the RNA binding sequences for two Drosophila SR proteins, RBP1 (12) and B52 (32). The target sequences identified by the two proteins are not similar and presumably identify different genes. A functional selection procedure also resulted in different consensus sequences for three different SR proteins (19). More specifically, the Drosophila doublesex gene contains multiple copies of the RBP1 sequence but no B52 target sequences. A specific endogenous target gene for B52 has not been identified. Binding site analysis of two different mammalian SR proteins agree with the findings for Drosophila and suggest that different SR proteins interact with a set of distinct RNA sequences (34). However, both B52 and RBP1 can activate splicing of the same ftz pre-mRNA. We found that ftz pre-mRNA contains a partial match to the B52 consensus binding site (32), but we have not found an RBP1 consensus binding site (12). Whether one or both of these SR proteins interact with the ftz pre-mRNA directly, possibly at different sites, or function indirectly through other splicing factors is not known. It has been shown that SR proteins can act directly on pre-mRNAs containing their target sequences, since placing the selected binding sites of B52 or ASF/SF2 in a pre-mRNA increases the splicing efficiency of the substrate (34; H. Shi, B. E. Hoffman, and J. T. Lis, unpublished results). Alternatively, SR proteins have been proposed to bridge the gap across introns to facilitate splicing through protein-protein interactions (39).

Understanding the roles of the SR family of proteins will require a battery of in vitro and in vivo studies. While some functions may be shared, others are clearly specific to particular members of the family. The differences in their RNA binding specificity, in the strength of their interactions with other proteins (39), and in their patterns of expression in whole organisms could all contribute to more-specialized roles for individual SR proteins. Finally, while it is clear that SR proteins function as splicing factors in vitro and that their levels influence splicing in vivo, we cannot rule out the possibility of other roles for these proteins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank D. Rio, V. Heinrichs, and B. Baker for plasmids; P. Ciampa and H. Shi for help with larval dissections; and E. Andrulis, D.-k. Lee, H. Shi, and R. C. Wilkins for critical readings of the manuscript. We especially thank J. Werner for performing the embryo injections.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM40918 to J.T.L. and National Research Service Award 5F32GM17509 to B.E.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brand A H, Perrimon N. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development. 1993;118:401–415. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cáceras J F, Stamm S, Helfman D M, Krainer A R. Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science. 1994;265:1706–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.8085156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavaloc Y, Popielarz M, Fuchs J P, Gattoni R, Stevenin J. Characterization and cloning of the human splicing factor 9G8: a novel 35 kDa factor of the serine/arginine protein family. EMBO J. 1994;13:2639–2649. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Champlin D T, Frasch M, Saumweber H, Lis J T. Characterization of a Drosophila protein associated with boundaries of transcriptionally active chromatin. Genes Dev. 1991;5:1611–1621. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darnell J E., Jr Variety in the level of gene control in eukaryotic cells. Nature. 1982;297:365–371. doi: 10.1038/297365a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dignam J D, Lebovitz R M, Roeder R G. Accurate transcription initiation by RNA polymerase II in a soluble extract from isolated mammalian nuclei. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:1475–1489. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.5.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fu X-D. Specific commitment of different pre-mRNAs to splicing by single SR proteins. Nature. 1993;365:82–85. doi: 10.1038/365082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu X-D. The superfamily of arginine/serine-rich splicing factors. RNA. 1995;1:663–680. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu X-D, Maniatis T. Factor required for mammalian spliceosome assembly is localized to discrete regions in the nucleus. Nature. 1990;343:437–441. doi: 10.1038/343437a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ge H, Manley J L. A protein factor, ASF, controls cell-specific alternative splicing of SV40 early pre-mRNA in vitro. Cell. 1990;62:25–34. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90236-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanamura A, Cáceres J F, Mayeda A, Franza B R, Jr, Krainer A R. Regulated tissue-specific expression of antagonistic pre-mRNA splicing factors. RNA. 1998;4:430–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinrichs V, Baker B S. The Drosophila SR protein RBP1 contributes to the regulation of doublesex alternative splicing by recognizing RBP1 RNA target sequences. EMBO J. 1995;14:3987–4000. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00070.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kenan D J, Query C C, Keene J D. RNA recognition: towards identifying determinants of specificity. Trends Biochem Sci. 1991;16:214–220. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90088-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim Y-J, Zuo P, Manley J L, Baker B S. The Drosophila RNA-binding protein RBP1 is localized to transcriptionally active sites of chromosomes and shows a functional similarity to human splicing factor ASF/SF2. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2569–2579. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kohtz J D, Jamison S F, Will C L, Zuo P, Luhrmann R, Garcia-Blanco M A, Manley J L. Protein-protein interactions and 5′-splice site recognition in mammalian mRNA precursors. Nature. 1994;368:119–124. doi: 10.1038/368119a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krainer A R, Maniatis T. Multiple factors including the small nuclear ribonucleoproteins U1 and U2 are necessary for pre-mRNA splicing in vitro. Cell. 1985;42:725–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramer A. The structure and function of proteins involved in mammalian pre-mRNA splicing. Annu Rev Biochem. 1996;65:367–409. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.002055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraus M E, Lis J T. The concentration of B52, an essential splicing factor and regulator of splice site choice in vitro, is critical for Drosophila development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5360–5370. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.8.5360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu H-X, Zhuang M, Krainer A R. Identification of functional exonic splicing enhancer motifs recognized by individual SR proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:1998–2012. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.13.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayeda A, Screaton G R, Chandler S D, Fu X-D, Krainer A R. Substrate specificities of SR proteins in constitutive splicing are determined by their RNA recognition motifs and composite pre-mRNA exonic elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1853–1863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayeda A, Zahler A M, Krainer A, Roth M. Two members of a conserved family of nuclear phosphoproteins are involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1301–1304. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng X, Mount S M. Genetic enhancement of RNA-processing defects by a dominant mutation in B52, the Drosophila gene for an SR protein splicing factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:6273–6282. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.6273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reed R, Griffith J, Maniatis T. Purification and visualization of native spliceosomes. Cell. 1988;53:949–962. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)90489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ring H Z, Lis J T. The SR protein B52/SRp55 is essential for Drosophila development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7499–7506. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.11.7499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rio D C. Accurate and efficient pre-mRNA splicing in Drosophila cell-free extracts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:2904–2908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.9.2904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robertson H M, Preston C R, Phillis R W, Johnson-Schlitz D M, Benz W K, Engels W R. A stable genomic source of P element transposase in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1988;118:461–470. doi: 10.1093/genetics/118.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roth M B, Murphy C, Gall J G. A monoclonal antibody that recognizes a phosphorylated epitope stains lampbrush chromosome loops and small granules in the amphibian germinal vesicle. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2217–2223. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roth M B, Zahler A M, Stolk J A. A conserved family of nuclear phosphoproteins localized to sites of polymerase II transcription. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:587–596. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rubin G M, Spradling A C. Genetic transformation of Drosophila with transposable element vectors. Science. 1982;218:348–353. doi: 10.1126/science.6289436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudner D Z, Kanaar R, Breger K S, Rio D C. Mutations in the small subunit of the Drosophila U2AF splicing factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10333–10337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Screaton G R, Cáceres J F, Mayeda A, Bell M V, Plebanski M, Jackson D G, Bell J I, Krainer A R. Identification and characterization of three members of the human SR family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. EMBO J. 1995;14:4336–4349. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi H, Hoffman B E, Lis J T. A specific RNA hairpin loop structure binds the RNA recognition motifs of the Drosophila SR protein B52. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2649–2657. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simon J A, Sutton C A, Lobell R B, Glaser R L, Lis J T. Determinants of heat shock-induced chromosome puffing. Cell. 1985;40:805–817. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90340-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tacke R, Manley J L. The human splicing factors ASF/SF2 and SC35 possess distinct, functionally significant RNA binding specificities. EMBO J. 1995;14:3540–3551. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valcárcel J, Green M R. The SR protein family: pleiotropic functions in pre-mRNA splicing. Trends Biochem Sci. 1996;21:296–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang J, Manley J L. Overexpression of the SR proteins ASF/SF2 and SC35 influences alternative splicing in vivo in diverse ways. RNA. 1995;1:335–346. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Takagaki Y, Manley J L. Targeted disruption of an essential vertebrate gene: ASF/SF2 is required for cell viability. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2588–2599. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.20.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang J, Xiao S-H, Manley J L. Genetic analysis of the SR protein ASF/SF2: interchangeability of RS domains and negative control of splicing. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2222–2233. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.14.2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J Y, Maniatis T. Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell. 1993;75:1061–1070. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90316-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xiao S-H, Manley J M. Phosphorylation of the ASF/SF2 RS domain affects both protein-protein and protein-RNA interactions and is necessary for splicing. Genes Dev. 1997;11:334–344. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.3.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zahler A M, Lane W S, Stolk J A, Roth M B. SR proteins: a conserved family of pre-mRNA splicing factors. Genes Dev. 1992;6:837–847. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.5.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zahler A M, Neugebauer K M, Lane W S, Roth M B. Distinct functions of SR proteins in alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Science. 1993;260:219–222. doi: 10.1126/science.8385799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zahler A M, Roth M B. Distinct functions of SR proteins in recruitment of U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein to alternative 5′ splice sites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2642–2646. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.2642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]