Abstract

Background

Targeting tumor microenvironment (TME) may provide therapeutic activity and selectivity in treating cancers. Therefore, an improved understanding of the mechanism by which drug targeting TME would enable more informed and effective treatment measures. Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch (GUF, licorice), a widely used herb medicine, has shown promising immunomodulatory activity and anti-tumor activity. However, the molecular mechanism of this biological activity has not been fully elaborated.

Methods

Here, potential active compounds and specific targets of licorice that trigger the antitumor immunity were predicted with a systems pharmacology strategy. Flow cytometry technique was used to detect cell cycle profile and CD8+ T cell infiltration of licorice treatment. And anti-tumor activity of licorice was evaluated in the C57BL/6 mice.

Results

We reported the G0/G1 growth phase cycle arrest of tumor cells induced by licorice is related to the down-regulation of CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex, which subsequently led to an increased protein abundance of PD-L1. Further, in vivo studies demonstrated that mitigating the outgrowth of NSCLC tumor induced by licorice was reliant on increased antigen presentation and improved CD8+ T cell infiltration.

Conclusions

Briefly, our findings improved the understanding of the anti-tumor effects of licorice with the systems pharmacology strategy, thereby promoting the development of natural products in prevention or treatment of cancers.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12935-021-02223-0.

Keywords: Tumor microenvironment, NSCLC, Licorice, Systems pharmacology strategy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the most prevalent diagnosed cancer worldwide and a major contributor of cancer mortality. And non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for approximately 85% of the diagnosed lung cancers [1–3]. In recent years, immunotherapy targeting T cells has increasingly shown its potentiality in the treatment of a wide variety of solid tumors, such as NSCLC [4–6]. Although encouraging, it is the fact that still only a small fraction of patients obtain long-term benefit, which is likely correlated with the complex network of the tumor microenvironment (TME) [7]. TME, a complex physical and biochemical system, plays a pivotal role in tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and drug resistance [8]. It contains cells of the immune system, tumor cells, tumor vasculature and extracellular matrices (ECM) [9]. Among them, tumor cells could express inhibitory ligands that suppress the T-cell activity to evade immune destruction. Immune cells could produce some cytokines, growth factors, enzymes, and angiogenic mediators to promote the growth of tumor [10]. And ECM consists of biological barriers around the tumor tissue to hamper lymphocyte penetration. Therefore, better understanding of the interactions in the TME would increase the ratio of patients benefiting from cancer therapies.

Traditional herb medicines and herbal derived components are playing increasingly critical roles in prevention and treatment of cancers [11, 12]. Compared with conventional chemotherapy, they are low toxicity and pleiotropic actions, targeting the complex network of TME by modulating multiple cell-signaling pathways involved in immune. Thereby, natural products could be a great repository for the development of novel therapeutic approaches in cancer treatment. As a well-known herbal medicine used worldwide for centuries, to date, several reports have published the immunomodulatory activity of licorice on multiple cancers, including colon cancer, breast cancer, acute myeloid leukemia, gastric cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer [13–16]. However, the molecular underpinnings of licorice exert its immunomodulatory potential have not been fully elaborated.

To address this question, we used a systems pharmacology strategy [17] to elaborate that how licorice exerts anti-tumor effects by regulating multiple immune-related signaling pathways and targets, influencing cell cycle progression, and mitigates the growth of NSCLC cancer. First, by screening the poly-pharmacology molecules of licorice, predicting the targets of active compounds, constructing the networks, and linking the targets to the immune phenotype in lung cancer patients, we observed that the active ingredients of licorice targeted a great variety of tumor-related signaling pathways, including cell cycle, inflammation, and migration. Then, we used in vitro and in vivo experiments to reveal the anti-tumor effects of licorice. On the one hand, we found that licorice down-regulates CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex, resulting in G0/G1 phase arrest and increased PD-L1 levels in lung cancer cells. On the other hand, we also found that licorice increased antigen presentation and infiltration of CD8+ T cell, significantly decreased tumor volume of mouse models of NSCLC in vivo. Taken together, our studies indicate that the systems pharmacology strategy greatly uncovered the action mechanism of poly-pharmacology molecules of licorice, contributing the use of natural products for further anti-cancer drug development.

Results

Systems pharmacology uncovers that licorice targets cell cycle progression and immune process

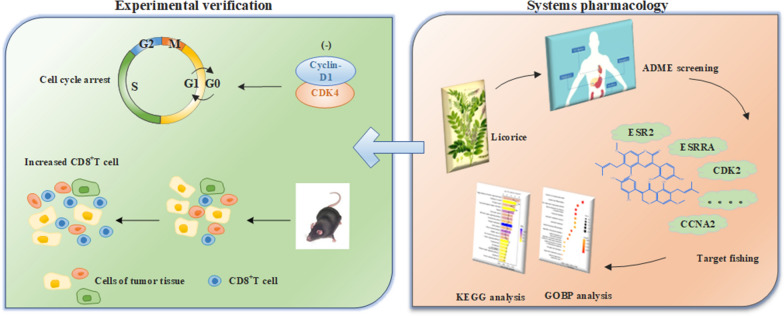

As a comprehensive system, the systems pharmacology approach was used to investigate the complex molecular mechanisms of licorice as a treatment for NSCLC in this study (as shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Workflow of systems pharmacology analysis to uncover mechanism of licorice

Altogether, 280 ingredients were identified in licorice with the searching literatures and using TCMSP and BATMAN-TCM, and a total of 23 active ingredients (shown in Table 1) with higher druggability were screened out by in silico ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) system, with the criteria of oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 50% and drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.40. Take Liquiritin as an example, it was predicted with OB = 65.69% and DL = 0.74, and inhibited H1975 cells growth significantly after 48 h treatments (Fig. 1a). The inhibitory effect by Liquiritin was also presented in the growth of colon carcinoma cell lines [18] and human cervical cancer cell lines [19]. These results demonstrated the validity of the raised criteria on screening potential druggability compounds for anti-tumor treatment.

Table 1 .

Chemical information and pharmacokinetics parameters of the 23 active compounds of licorice

| MOL-ID | Compounds | Structure | Categories | OB | DL | Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOL005008 | Glycyrrhiza flavonol A |

|

Flavonoids | 41.28 | 0.60 | 30 |

| MOL001484 | Inermine |

|

Flavonoids | 75.18 | 0.54 | 35 |

| MOL000211 | Mairin |

|

Saponins | 55.38 | 0.78 | 16 |

| MOL002311 | Glycyrol |

|

Coumestans | 90.78 | 0.67 | 14 |

| MOL004808 | Glyasperin B |

|

Others | 65.22 | 0.44 | 31 |

| MOL004810 | Glyasperin F |

|

Others | 75.84 | 0.54 | 33 |

| MOL004820 | Kanzonols W |

|

Flavonoids | 50.48 | 0.52 | 38 |

| MOL004855 | Licoricone |

|

Flavonoids | 63.58 | 0.47 | 23 |

| MOL004863 | 3-(3,4-Dihydroxyphenyl)-5,7-dihydroxy-8-(3-methylbut-2-enyl)chromon |

|

Others | 66.37 | 0.41 | 26 |

| MOL004879 | Glycyrin |

|

Coumarins | 52.61 | 0.47 | 22 |

| MOL004885 | Licoisoflavanone |

|

Flavonoids | 52.47 | 0.54 | 31 |

| MOL004891 | Shinpterocarpin |

|

Flavonoids | 80.3 | 0.73 | 44 |

| MOL004903 | Liquiritin |

|

Flavonoids | 65.69 | 0.74 | 21 |

| MOL004904 | Licopyranocoumarin |

|

Flavonoids | 80.36 | 0.65 | 25 |

| MOL004908 | Glabridin |

|

Flavonoids | 53.25 | 0.47 | 39 |

| MOL004912 | Glabrone |

|

Flavonoids | 52.51 | 0.5 | 38 |

| MOL004914 | 1,3-Dihydroxy-8,9-dimethoxy-6-benzofurano[3,2-c]chromenone |

|

Others | 62.9 | 0.53 | 20 |

| MOL004959 | 1-Methoxyphaseollidin |

|

Flavonoids | 69.98 | 0.64 | 35 |

| MOL005001 | Gancaonin H |

|

Others | 50.1 | 0.78 | 30 |

| MOL005003 | Licoagrocarpin |

|

Flavonoids | 58.81 | 0.58 | 37 |

| MOL005007 | Glyasperins M |

|

Flavonoids | 72.67 | 0.59 | 39 |

| MOL005012 | Licoagroisoflavone |

|

Flavonoids | 57.28 | 0.49 | 36 |

| MOL005017 | Phaseol |

|

Coumestans | 78.77 | 0.58 | 21 |

OB: oral bioavailability; DL: drug-likeness

Then, predicted by the weighted ensemble similarity method (WES) [20] and systematic drug targeting tool (SysDT) [21], we found that these 23 ingredients in licorice were investigated interacted with 109 targets (shown in Table 2 and Additional file 1: Table S1). And we constructed the compound-target (C-T) network graph to greatly illustrate the relationships between compounds and targets. In terms of the targets interacted with licorice, we observed that most of which were related to cell cycle, immune, inflammation, cancer and neoplasm metastasis with higher scores, specifically, such as CDK2, ESR1, PPARG, ESRRA, PRKACA, CXCL8, PLAA, RXRB, MAPK14 and so on (shown in Fig. 2a).

Table 2.

The information of licorice’s targets

| UniProt-ID | Protein names | Gene names | Degree | Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P0DP23 | Calmodulin-1 | CALM1 | 19 | Homo sapiens |

| P35368 | Alpha-1B adrenergic receptor | ADRA1B | 5 | homo sapiens |

| P00918 | Carbonic anhydrase 2 | CA2 | 17 | Homo sapiens |

| P18031 | Tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 1 | PTPN1 | 17 | Homo sapiens |

| P46098 | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 3A | HTR3A | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P20309 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M3 | CHRM3 | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| P23219 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 1 | PTGS1 | 8 | Homo sapiens |

| Q14524 | Sodium channel protein type 5 subunit alpha | SCN5A | 11 | Homo sapiens |

| P07477 | Trypsin-1 | PRSS1 | 18 | Homo sapiens |

| P17612 | cAMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit alpha | PRKACA | 6 | Homo sapiens |

| O14757 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase | CHEK1 | 18 | Homo sapiens |

| P11309 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase pim-1 | PIM1 | 20 | Homo sapiens |

| P35354 | Prostaglandin G/H synthase 2 | PTGS2 | 20 | Homo sapiens |

| P27487 | Dipeptidyl peptidase 4 | DPP4 | 13 | Homo sapiens |

| Q16539 | Mitogen-activated protein kinase 14 | MAPK14 | 13 | Homo sapiens |

| P48736 | Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit gamma isoform | PIK3CG | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| P21730 | C5a anaphylatoxin chemotactic receptor 1 | AR | 22 | Homo sapiens |

| P49841 | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta | GSK3B | 17 | Homo sapiens |

| P24941 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | CDK2 | 17 | Homo sapiens |

| Q92731 | Estrogen receptor beta | ESR2 | 16 | Homo sapiens |

| P07900 | Heat shock protein HSP 90-alpha | HSP90AA1 | 12 | Homo sapiens |

| P20248 | Cyclin-A2 | CCNA2 | 20 | Homo sapiens |

| B2RXH2 | Lysine-specific demethylase 4E | KDM4E | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| O00767 | Stearoyl-CoA desaturase | SCD | 10 | Homo sapiens |

| O95622 | Adenylate cyclase type 5 | ADCY5 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P08842 | Steryl-sulfatase | STS | 13 | Homo sapiens |

| P11474 | Steroid hormone receptor ERR1 | ESRRA | 12 | Homo sapiens |

| P12644 | Bone morphogenetic protein 4 | BMP4 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16152 | Carbonyl reductase [NADPH] 1 | CBR1 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P28223 | 5-hydroxytryptamine receptor 2A | HTR2A | 18 | Homo sapiens |

| P51843 | Nuclear receptor subfamily 0 group B member 1 | NR0B1 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| Q99814 | Endothelial PAS domain-containing protein 1 | EPAS1 | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9Y263 | Phospholipase A-2-activating protein | PLAA | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| O60218 | Aldo–keto reductase family 1 member B10 | AKR1B10 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P05093 | Steroid 17-alpha-hydroxylase/17,20 lyase | CYP17A1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P10276 | Retinoic acid receptor alpha | RARA | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11413 | Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase | G6PD | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11473 | Vitamin D3 receptor | VDR | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16662 | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 | UGT2B7 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P18405 | 3-oxo-5-alpha-steroid 4-dehydrogenase 1 | SRD5A1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P19793 | Retinoic acid receptor RXR-alpha | RXRA | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P36873 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase PP1-gamma catalytic subunit | PPP1CC | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P80365 | Corticosteroid 11-beta-dehydrogenase isozyme 2 | HSD11B2 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q08828 | Adenylate cyclase type 1 | ADCY1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q12908 | Ileal sodium/bile acid cotransporter | SLC10A2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9NRD8 | Dual oxidase 2 | DUOX2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9UBM7 | 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase | DHCR7 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P03372 | Estrogen receptor | ESR1 | 13 | Homo sapiens |

| P03420 | Fusion glycoprotein F2 | F2 | 18 | Homo sapiens |

| P37231 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma | PPARG | 19 | Homo sapiens |

| P30291 | Wee1-like protein kinase | WEE1 | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| P23141 | Liver carboxylesterase 1 | CES2 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P05067 | Amyloid-beta precursor protein | APP | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P09960 | Leukotriene A-4 hydrolase | LTA4H | 10 | Homo sapiens |

| P10636 | Microtubule-associated protein tau | MAPT | 9 | Homo sapiens |

| Q04206 | Transcription factor p65 | RELA | 6 | Homo sapiens |

| P22303 | Acetylcholinesterase | ACHE | 11 | Homo sapiens |

| Q15596 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 2 | NCOA2 | 10 | Homo sapiens |

| P11388 | DNA topoisomerase 2-alpha | TOP2A | 11 | Homo sapiens |

| P35968 | Vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 | KDR | 8 | Homo sapiens |

| P00742 | Coagulation factor X | F10 | 16 | Homo sapiens |

| P08709 | Coagulation factor VII, EC 3.4.21.21 | F7 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| P11926 | Ornithine decarboxylase | ODC1 | 10 | Homo sapiens |

| P14061 | 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 | HSD17B1 | 5 | Homo sapiens |

| P18054 | Olyunsaturated fatty acid lipoxygenase ALOX12 | ALOX12 | 7 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9UHC3 | Acid-sensing ion channel 3 | ASIC3 | 12 | Homo sapiens |

| P05091 | Aldehyde dehydrogenase | ALDH2 | 4 | Homo sapiens |

| P37058 | Testosterone 17-beta-dehydrogenase 3 | HSD17B3 | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| Q13887 | Krueppel-like factor 5 | KLF5 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q15788 | Nuclear receptor coactivator 1 | NCOA1 | 6 | Homo sapiens |

| Q12809 | Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily H member 2 | KCNH2 | 5 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9H4B7 | Tubulin beta-1 chain | TUBB1 | 5 | Homo sapiens |

| P12268 | Inosine-5'-monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 | IMPDH2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11308 | Transcriptional regulator ERG | ERG | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P45985 | Dual specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 | MAP2K4 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P25100 | Alpha-1D adrenergic receptor | ADRA1D | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P36544 | Neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit alpha-7 | CHRNA7 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P28702 | Retinoic acid receptor RXR-beta | RXRB | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P08912 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M5 | CHRM5 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P11229 | Muscarinic acetylcholine receptor M1 | CHRM1 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P07550 | Beta-2 adrenergic receptor | ADRB2 | 4 | Homo sapiens |

| P35372 | Mu-type opioid receptor | OPRM1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P41143 | Delta-type opioid receptor | OPRD1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| O60502 | Protein O-GlcNAcase | OGA | 1 | homo sapiens |

| P08514 | Integrin alpha-IIb | ITGA2B | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P16278 | Beta-galactosidase | GLB1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P28838 | Cytosol aminopeptidase | LAP3 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P31639 | Sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 | SLC5A2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P53396 | ATP-citrate synthase | ACLY | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P54577 | Tyrosine–tRNA ligase, cytoplasmic | YARS | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| O75907 | Diacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 | DGAT1 | 3 | Homo sapiens |

| P14222 | Perforin-1 | PRF1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P51684 | C–C chemokine receptor type 6 | CCR6 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P05177 | Cytochrome P450 1A2 | CYP1A2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q16678 | Cytochrome P450 1B1 | CYP1B1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q92959 | Solute carrier organic anion transporter family member 2A1 | SLCO2A1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P29474 | Nitric oxide synthase | NOS3 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P08684 | Cytochrome P450 3A4 | CYP3A4 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P09211 | Glutathione S-transferase P | GSTP1 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| Q99835 | Smoothened homolog | SMO | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q9NYA1 | Sphingosine kinase 1 | SPHK1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P48039 | Melatonin receptor type 1A | MTNR1A | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| Q03181 | Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta | PPARD | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P10145 | Interleukin-8 | CXCL8 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P62993 | Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2 | GRB2 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

| P01857 | Immunoglobulin heavy constant gamma 1 | IGHG1 | 2 | Homo sapiens |

| P35228 | Nitric oxide synthase | NOS2 | 20 | Homo sapiens |

| P04798 | Cytochrome P450 1A1 | CYP1A1 | 4 | Homo sapiens |

| Q12791 | Calcium-activated potassium channel subunit alpha-1 | KCNMA1 | 1 | Homo sapiens |

Fig. 2.

Systems pharmacology analysis of targets of licorice. a Construction of compound-target network, the triangle represents compounds, the octagon represents targets, the edge represents connection between compounds and targets. b GO enrichment analysis of potential targets of licorice, the y-axis represents the enriched GO terms, and the GeneRatio represents the number of targets located in this GO/the total number of targets located in the GO. c GO terms associated with immune process were shown, and the size of the circle represents the count. d KEGG analysis of targets of licorice, the color represents the enrichment significance, the y-axis represents pathways, and the GeneRatio represents the number of targets located in this KEGG pathways/the total number of targets located in the KEGG pathways

To analyze the biological processes in which the targets of the bioactive ingredients participated, we implemented Gene Ontology (GO) biological processes enrichment analysis. As shown in Fig. 2b, metabolic processes or pathways of steroid, hormone and fatty acid were enriched, such as “steroid metabolic process”, “hormone metabolic process” and “fatty acid derivative metabolic process”, which are the most prominent metabolic alterations in cancer [22], 23. The biological processes of “response to peptide”, “cellular response to peptide” were also enriched, which are important ways to stimulate the acquired immune system. Thus, enrichment analysis of targets demonstrated that licorice has the potential anti-tumor effects by regulating tumor cell viability and anti-tumor immunity [24, 25].

To further clarify the relationship between licorice targets and biological processes of immunity, we therefore screened out the immune-related GOBP terms (Fig. 2c) and found that terms of differentiation, activation and migration of innate immune cells, myeloid cell, leukocyte or neutrophil were top enriched. Several inflammation-associated processes were also presented including “ regulation of cytokine production involved in inflammatory response”, “response to lipopolysaccharide”, etc., which involve in the processes of tumor growth such as angiogenesis [26–28]. These biological processes showed that the targets of bioactivate compounds are closely related to cancer.

In the list of the TOP 20 pathways, 10 significantly enriched pathways involved in cancer and immune were found by the KEGG Pathway analysis (Fig. 2d). A cohort of pathways (7/10) directly related to cancer, for example, “Pathways in cancer”, “Prostate cancer”, “Pancreatic cancer”, “Small cell lung cancer”, “Bladder cancer”, “non-small cell lung cancer”, and “Chronic myeloid leukemia” were enriched. Besides, “NOD-like receptors signaling pathway”, “T cell receptor signaling pathway”, and “Toll-like receptor signaling pathway”, these immune related pathways (3/10) were also identified. “Apoptosis” and “Calcium signaling pathway” were also showed in the chart which were downstream process or signaling pathway in cancer development. All the data indicated the reliability of the potential effect of compounds of licorice on cancer treatment.

Therefore, the systems pharmacology analysis uncovers that licorice mainly targets cancer cell and immune progress to exert its anti-cancer effect, and paves the way for in-depth understanding of the multi-target molecular mechanism of licorice treating for NSCLC.

Licorice induced tumor cells cycle arrest mainly by down-regulating Cyclin D1-CDK4

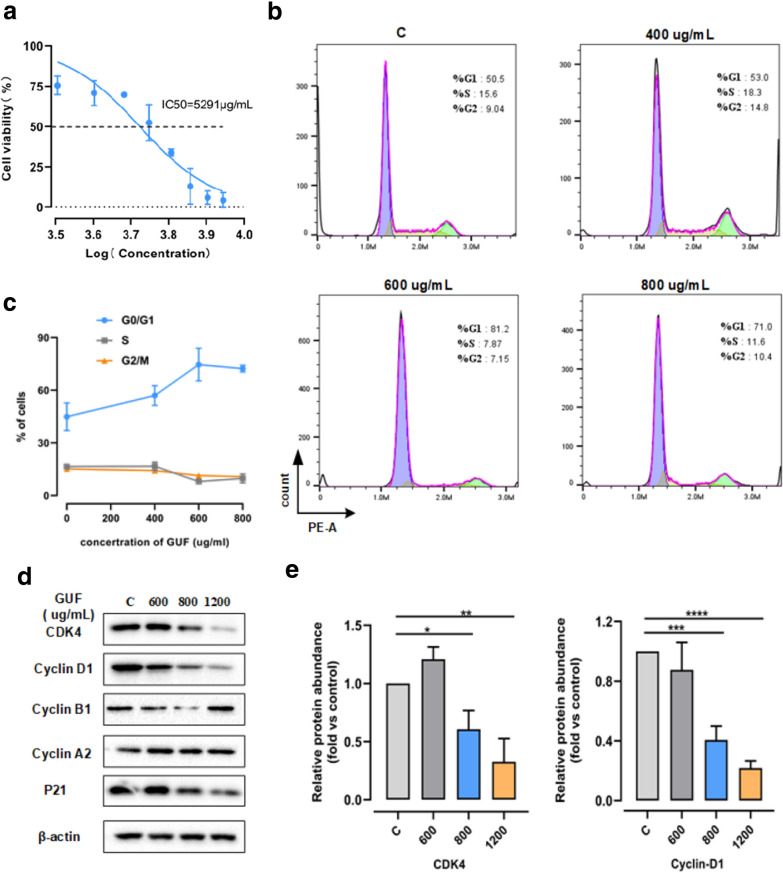

To further study the anti-cancer effect of licorice on NSCLC, we firstly tested the effects of licorice on the growth of tumor cells. According to the CCK8 assay results shown in Fig. 3a, we could recognize that licorice induced a concentration-dependent inhibition of H1975 cell proliferation. Treating licorice 2 days with concentrations of 3200, 5600 and 7200 μg/mL, we found that compared to the control group, the H1975 cell growth decreased by 25, 48 and 87%, respectively. Moreover, the IC50 value on it is ~ 5400 μg/mL.

Fig. 3.

Licorice induces tumor cell G0/G1 phase arrested with the degradation of CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex. a H1975 cells were treated with different concentrations of licorice for 48 h, cell viability was determined using the CCK-8 assay. (mean ± SD, n = 6). b The cell-cycle profiles of H1975 cells incubated with 400, 600, 800 µg/ml GUF or vehicle control for 48 h were shown by using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). c Percentages of H1975 cells in b at different cell cycle states. d The protein expression in H1975 cells pretreated with 400, 600, 800 µg/ml GUF or vehicle control were measured by western blot anaylsis , versus β-actin as a loading control. e Relative protein abundance of CDK4 and Cyclin D1 of d. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001

Next, given the analysis of systems pharmacology for licorice, and a number of studies have shown that the negative effects of licorice or its relatives on cell cycle progression [15, 16, 29, 30], we reasoned that licorice might influenced cell cycle to exert the anti-tumor effect on NSCLC to some extent. To test the hypothesis, we treated H1975 cells with different concentrations of licorice followed by flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle profile. Strikingly, H1975 cells subjected to licorice led to a significant increase in the number of cells arrested at G0/G1 growth phase, in a dose-dependent manner, compared with vehicle control containing media (shown in Fig. 3b and c). At the same time, the number of cells at both S growth phase and G2/M growth phase slightly decreased (Fig. 3c). This findings consistent with previous study that licorice induced G1 cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells [16].

It has been known that cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK)/cyclin complexes, such as CDK2/Cyclin E, CDK4, CDK6/Cyclin D1, and P21 play crucial roles in cell cycle progression [31]. Therefore, to elucidate the underlying molecular mechanism with which licorice induced cell cycle arrest at G0/G1 growth phase, immunoblot analysis were performed to evaluate cell cycle-related protein abundance in vitro experiment. Notably, we found that the levels of CDK4, cyclin D1 were reduced with concentration dependent, while the expressions of Cyclin B1 and Cyclin A2 were relatively maintained at the level of the control group following licorice treatment (Fig. 3d and e). Interestingly, the expression of p21, a CDK inhibitor, was slightly decreased in response to licorice exposure vs control group (shown in Fig. 3d).

In addition, previous works uncovered that cyclin D1 degradation occurs mainly at the G1/S phase boundary [31, 32]. Collectively, these results indicated that licorice is likely to induce tumor cells arrested at G0/G1 growth phase by down-regulating CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex.

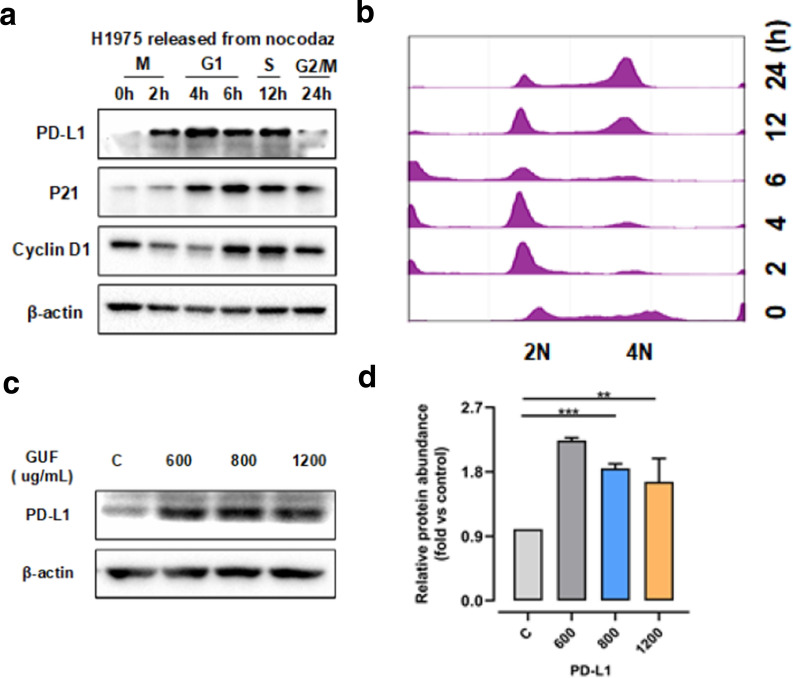

Licorice positively regulates PD-L1 protein abundance

It has been shown that PD-L1 expression can be modulated at both transcriptional and post-translational levels, however, it is not yet clear whether PD-L1 expression is regulated under physiological conditions for example during cell cycle progression [33–36]. In this setting, to further understand the connection between PD-L1 and cell cycle, we used cell synchronization by nocodazole arrest and western blot analysis to explore variation of PD-L1 during cell cycle. As shown in Fig. 4a and b, we found that PD-L1 protein expression increased in M/early G1 phases, followed by a great decrease in late G1/S phases.

Fig. 4.

Licorice induces increase of expression level of PD-L1. a Western blot results of whole cell lysates derived from H1975 cells synchronized in M phase by nocodazole treatment prior to releasing back into the cell cycle for the indicated times. b The cell-cycle profiles in a were monitored by FACS. c The protein expression in H1975 cells pretreated with 400, 600, and 800 µg/ml GUF or vehicle control, was measured by western blot, versus β-actin as a loading control. d Relative protein abundance of PD-L1 of c. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

As our results showed that licorice down-regulates CDK4-Cyclin D1expression to arrest cell cycle progression, we probed whether licorice participated in variation of PD-L1. To do this, we treated H1975 cells with different concentration of licorice extract, followed by western blot analysis. Strikingly, licorice administration result in a significant increase in the expression of PD-L1 protein (Fig. 4c and d), in a dose-dependent manner. Similar to H1975 cells, we also found that licorice down-regulates CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex and leads to increased protein abundance of PD-L1 in A549 cells subjected to different concentrations of licorice (Fig. 3). Furthermore, recent finding had shown that CDK4-Cyclin D 1 kinase destabilized PD-L1, inhibition of CDK4/6 in vivo increased PD-L1 protein levels [37]. Together, these findings indicated that increased levels of PD-L1 expression by licorice correlated with down-regulation of CDK4-Cyclin D1 expression.

Licorice induces tumor regression by affecting CDK4-Cyclin D1

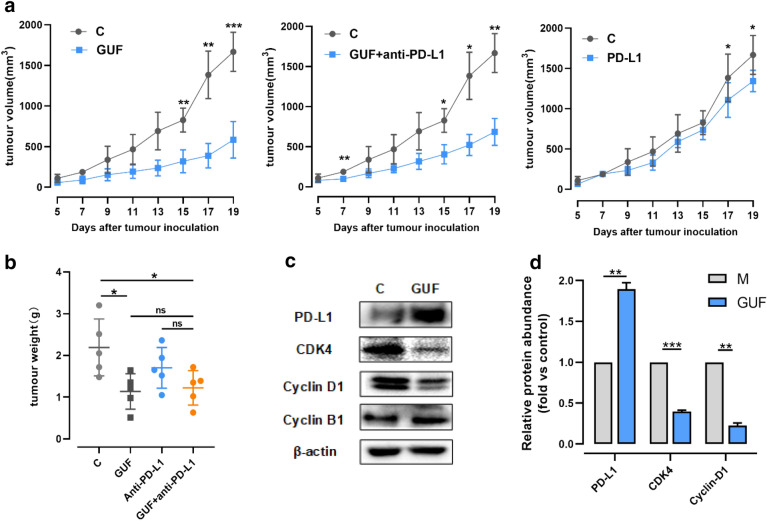

Based on previous studies that various natural compounds in licorice possess effective antitumor activity [14, 16, 38, 39], we wanted to know whether licorice can function in vivo to suppress tumor progression for NSCLC. To do so, we utilized C57/BL6 female mice bearing LLC tumor to assess the anti-tumor impact of licorice. And the size-matched tumor-bearing mice were divided into 4 groups randomly and received the administrations (as depicted in Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5.

Licorice inhibits the growth of tumor volume depending on the CDK4-Cyclin D1 axis. a C57BL/6 mice were injected with 5×105 LLC cells. 24 h later, 200 mg/kg GUF or vehicle were administered once daily from day 2 and/or 200 μg/mouse anti-PD-L1 (i.p.) on day 4, 7, 10 (n = 5 per group). The tumor growth curve is shown, with tumor sizes presented as mean ± SD. b Primary tumor mass of mice is shown, presented as mean ± SD. c Protein expression in tumors from GUF group and control group was measured by western blot, versus β-actin as a loading control. d Relative protein abundance of PD-L1, CDK4, Cyclin D1, Cyclin B1 of c, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, n.s.: no significant

By day 20 of treatment, as expected, all control mice encountered humane endpoints. Then mice from each group were killed and dissected tumor, mouse serum was taken out and stored for subsequent experiments.

It is critical to note that licorice treatment result in a 64.9% tumor volume regression, and we found that there was slightly inhibitory effect on tumor volume of mice treated with anti-PD-L1 antibody alone vs control mice. Interestingly, we also observed a 54.7% tumor volume reduction in licorice + anti-PD-L1 mice compared with control mice over time (Fig. 5a).

Consistent with the observed reduction in tumor volume, treatment of licorice led to a significant induction of tumor weight, this also occurred in licorice + anti-PD-L1 group compared with untreated group. However, slight reduction of tumor weight was observed in anti-PD-L1 alone group (Fig. 5b). No significant loss of mice body weight was displayed among all the groups throughout the period of the experiment (Additional file 1: Fig. S4a).

Having pinpointed the critical role for licorice in affecting Cyclin D1-CDK4 expression in vitro, we next examined whether licorice had similar influence in vivo. Therefore, we assayed cell cycle-related protein for tumor tissue using the western blot assay. Consistent with earlier observation in vitro (Fig. 3d), licorice treatment markedly reduced the abundance of CDK4 and Cyclin D1, and led to a dramatic PD-L1 accumulation compared with control group significantly (Fig. 5c and d).

Therefore, these results coherently indicated that licorice might mainly function through down-regulating CDK4-Cyclin D1 to stabilize PD-L1 and subsequently suppress tumor progression.

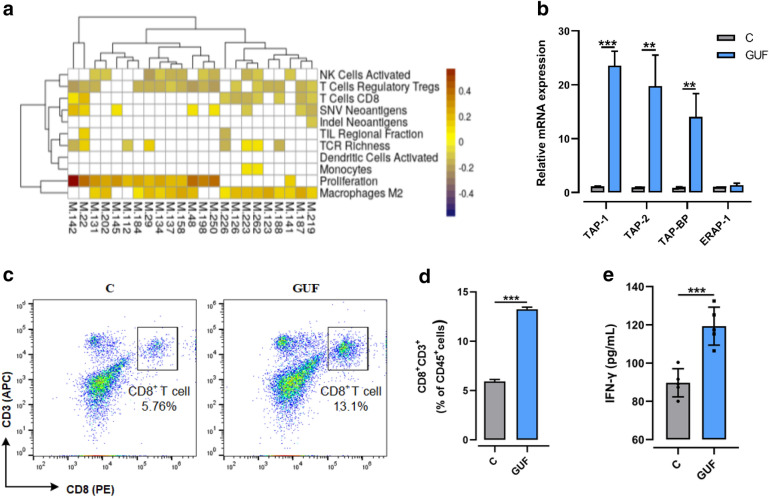

Licorice increases antigen presentation and infiltration of CD8+ T cell

Furthermore, we showed that targets of licorice active compounds correlated with CD8+ T-cell infiltration in TCGA LUAD patients . And the immune phenotypes of TCGA LUAD patients were evaluated by Thorsson et al. [40] , (Fig. 6a, Additional file 1: Figs. S4b, c). Then intratumoral CD8+ T-cell infiltration in tumor tissue lysates were measured by flow cytometry analysis. To this end, a flow cytometry staining protocol was established to identify CD8+ T cell populations in tumors. We manually analyzed the flow cytometry data using a common rational gating strategy included three gate events as follows in the work: total number of all live-gated events, immune compartment gate events, and CD8+ T gate events (Additional file 1: Figure S4d). Importantly, CD8+ T cell infiltration of licorice-treated mice we detected increased by 6% of that in untreated mice (Fig. 6c and d). To further support of the physiological role for licorice in promoting CD8+ T cell infiltration, we used the mice serum to perform ELISA-based assays and found a remarkable increase of IFN-γ in licorice-treated mice (Fig. 6e). These results were in line with a previous study that CDK4/6 inhibitors induce breast cancer cell cytostasis and enhance their capacity to present antigen and stimulate cytotoxic T cells [41].

Fig. 6.

Licorice increases antigen presentation and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in vivo. a Heatmap of Pearson’s correlation coefficients (PCCs) between gene expression level of targets of licorice and immune phenotypes in TCGA LUAD dataset. For the targets of each active compound, we used the GSVA method to evaluate the overall expression level of targets based on the gene expression profiles of LUAD patients. The y-axis represents the compounds of licorice. b Relative Quantitative real-time PCR (q RT-PCR) analyses of relative mRNA levels of antigen presentation gene from licorice-treated tumors or vehicle. The experiments were repeated three times. Data was analyzed using ANOVA test. c Freshly isolated lymphocytes of tumor tissue samples from the GUF-treated and control groups were stained with anti-CD45 (PE-Cy7), anti-CD3 (APC), and anti-CD8 (PE) antibodies and infiltration of CD8+ T cells examined by FACS. Representative flow-cytometry plots were shown. d Ratio of infiltration of CD8+ T cells in mice tumor samples from the GUF-treated group versus control group. e Bar graph of IFN-γ levels based on ELISA in mice tumor samples from the GUF-treated group and control group were shown, (n = 5). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Next, to gain insights into the physiological role of licorice in modulating tumor regression at a gene level, RT-qPCR analysis was performed. Specifically, we sought to determine relative mRNA levels of antigen presentation genes by RT-qPCR analysis, and observed that transporter–MHC interactions (Tap-bp) had at least a 15 × fold increase in licorice-treated tumor tissues compared to control tumor samples. And peptide transporters (Tap1 and Tap2) were also markedly up-regulated in licorice-treated tumors, although directing peptide cleavage (Erap1) hardly change to some extent (Fig. 6b).

Altogether, these studies indicated that licorice increased expression of antigen presentation genes and promoted CD8+ T cell infiltration of tumor tissue.

Discussion

Natural products were shown broadly to interfere growth signals by multi-specific actions [42], which may open an opportunity to treat NSCLC effectively. In a panel of human cancers, licorice has been uncovered to provide growth-limiting activities [16, 38, 43]. Although changes in the cell-cycle have been noted under licorice treatment settings [29, 30], dissecting mechanism of the biological activity of licorice remains a challenge. Here, the critical findings of our study, summarized in Figs. 5c and 2d, include the discovery that licorice limits lung cancer growth mainly related with down-regulating CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex and enhancing intra-tumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration. Our detailed investigation shows that licorice induces G1 cell-cycle arrest in lung cancer cells by inhibiting CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex, which in turn increases antigen presentation and results in intra-tumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration but increase PD-L1 levels. These findings convincingly argue for a potential treatment option of licorice in the prevention and treatment of NSCLC.

Beginning with systems pharmacology analysis, flow cytometry analysis of cell cycle profile and western blot, we observed that licorice treatment led to G1 cell-cycle arrest and inhibit the expression of CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex in H1975 cells. This biological activity was further validated in licorice-treated tumor. It is well known that CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex were required for progression of cells cycle through the G0/G1 phase [44–46], which would suggest that G1 cell-cycle arrest is largely associated with decreased levels of CDK4-Cyclin D1 after licorice treatment. The tumor regression caused by down-regulation of CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex has been demonstrated in CDK4/CDK6 inhibitor studies. As a kind of CDK4/6 inhibitors, abemaciclib caused regression of bulky tumors in mouse models of mammary carcinoma [41]. Furthermore, many human cancers harbor genomic or transcriptional aberrations that could activate CDK4/6 [47–49]. Therefore, our findings revealed that licorice inhibit the expression of CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex would be critically important for prevention and treatment of lung cancers.

Moreover, CDK4-Cyclin D was found negatively regulates PD-L1 protein stability in several tumor cell lines [37, 50]. And previous studies revealed that response to PD-1/PD-L1 blockade might correlate with PD-L1 expression levels in tumor cells [51–53]. Notably, we discovered that licorice treatment induced increased expression of PD-L1 levels both in vitro and in vivo. These studies, together with our findings, shed light on a viable option for the management of NSCLC, with or without other treatments in conjunction, to enhance the efficiency of cancer immunotherapies.

The functional impairment of T cell-mediated immunity in the TME is a defining feature sharing by many cancers, and CD8+ T cells became the central focus of new cancer therapeutics [54, 55]. Data showed that licorice could increase the expression of antigen presentation genes and promote CD8+ T cell infiltration within the circumstance of cell cycle arrest. So, we concluded that licorice induces G1 cell-cycle block in lung cancer cells by inhibiting CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex, which in turn increase antigen presentation and results in intra-tumoral CD8+ T cell infiltration. Consistent with the results of multiple studies, cell cycle blockade can activate anti-tumor immunity by increasing the immunogenicity of tumor cells [56] and can also increase the expression of PD-L1 to inhibit anti-tumor immunity [57]. Theoretically, licorice increases the infiltration of CD8+ T cells into the TME, which may enhance the anti-tumor effect of anti-PD-L1. However, the expected enhancement effect was not observed in the combination of licorice and anti-PD-L1. We speculate that licorice may affect the activation of CD8+ T cells through the direct PD-1/PD-L1 signaling pathway of T cells, which is consistent with the function of anti-PD-L1. Therefore, the combination of licorice and anti-PD-L1 did not show a synergistic anti-cancer effect. In fact, licorice has been known to promote maturation and differentiation of lymphocyte in order to activate the immune system [58, 59]. In the subsequent research, we will focus in-depth research and verification on this problem.

In summary, this study evidenced that licorice induced G0/G1 phase cell cycle arrest by down-regulating CDK4-Cyclin D1 complex on tumor cells. In addition, licorice increased the expression of antigen presentation genes and infiltration of CD8+ T cells in TME . Therefore, this study illuminated a novel mechanism of anti-tumor effect of licorice in NSCLC treatment, and provide functional evidence for the development of natural products in anti-tumor immunity.

Methods

Pharmacokinetic evaluation

The ingredients of licorice were identified based on Traditional Chinese Medicine Systems Pharmacology Database (TCMSP, http://tcmspw.com/) [60] and Bioinformatics Analysis Tool for Molecular mechANism of Traditional Chinese Medicine (http://bionet.ncpsb.org.cn/batman-tcm/), [61], and active ingredients (shown in Table 1) were further screened out by the in silico ADME system, with the criteria of oral bioavailability (OB) ≥ 50%, drug-likeness (DL) ≥ 0.40.

Target fishing and validation

We identified direct and indirect targets of licorice on the basis of two in-house computational methods: WES and SysDT. The WES model was introduced to detect drug direct targets of the active ingredients based on a large-scale of 98,327 drug-target relationships. As a novel tool, the obtained model performs well in predicting the binding with average sensitivity of 85% (SEN) and the non-binding patterns with 71% (SPE) with the average areas under the receiver operating curves (ROC, AUC) of 85.2% and an average concordance of 77.5% [62]. SysDT is performed with the combination of the chemical, genomic and pharmacological information based on Random Forest (RF) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) for target identification effectively. The obtained model is served as a valuable platform for prediction of drug-target interactions with an overall accuracy of 97.3%, an activated prediction accuracy of 87.7% and an inhibited prediction accuracy of 99.8% [63].

Then obtained targets were uploaded to Uniprot (http://www.uniprot.org) [64] to normalize their name and organisms. And the targets of Homo sapiens were chosen for further investigation. We used Cytoscape 3.7.0 software to construct and analyze compound-target network.

GO enrichment analysis and KEGG analysis for targets

GOenrichment analysis and KEGG analysis were performed through mapping targets to DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov) for classification. We chose the terms with P value less than 0.05.

Cell proliferation assay

Cellular proliferation was assayed using a Cell Counting Kit‐8 (CCK‐8, Beyotime, China). In brief, 1 × 104 cells were seeded in 96‐well microplates. After 24 h, cells were treated with different concentrations of licorice or vehicle for 48 h. Then, 10μL CCK‐8 solution was added to each well and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured using a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, California, USA).

Cell lines, compounds, and reagents

H1975 A549 cells (National Collection of Authenticated Cell Cultures, Shanghai, China) were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (C11875500BT, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (10099141, Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Licorice powder was purchased from LEMETIAN MEDICINE. And Typical HPLC chromatogram of licorice extract performed by LEMETIAN MEDICINE (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

FACS analysis of cell cycle

Once H1975 cells achieved a 70% to 80% confluency, they were treated with 0.1% DMSO or different concentration of licorice for 48 h. Then, cells were fixed with ice-cold 70% ethanol at − 20 °C overnight. After fixation, cells were washed thrice with cold PBS and then stained with Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis Kit (C1052, Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were then analyzed using a NovoCyte Flow Cytometer (ACEA Biosciences). The results were analyzed by Flow Jo software (BD bioscience).

Western blotting

For western blot analysis, cells or tumor tissue were lysed in lysis buffer from the Qproteome Mammalian Protein Prep Kit (37901, QIAGEN) with the addition of protease inhibitors after PBS washing. Protein concentrations were measured by a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, California, USA) using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (P0010S, Beyotime, China). Then equal amounts of protein were resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) and incubated with primary antibodies against: CDK4 (1:5000, ab108357, Abcam), cyclin D1 (1:1000, 554180, BD Bioscience, USA), cyclin A2 (1:2000, ab181591, Abcam), cyclin B1 (1:50000, ab32053, Abcam), P21 (1:5000, ab109520, Abcam), PD-L1 (1:500, ab205921, Abcam or 1:2000, PA5-28115, Thermo Fisher scientific) and β-actin (1:2000, ab8227, Abcam); Secondary antibodies were goat anti-rabbit HRP (1:10000, ab6721, Abcam) and goat anti-mouse HRP (1:5000, ab97023, Abcam). Immunoreactive polypeptides were detected by electrochemiluminescence (ECL) reagents (Cat#170-5061, Bio Rad) using ChemiDoc™ XRS + Imaging System (Bio-Rad). Western blot band intensity quantification was calculated using ImageJ.

Cell synchronization and FACS analyses

For synchronization into the G2/M phase of the cell cycle progression, H1975 cells were treated with 100 ng/mL of nocodazole (M1404, Sigma-Aldrich) for 16 h. Then cells release was collected at the indicated time points and fixed by 70% ethanol at − 20 °C overnight. After fixation, cells were washed 3 times with cold PBS and stained with Cell Cycle and Apoptosis Analysis Kit (C1052, Beyotime Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Stained cells were sorted with NovoCyte Flow Cytometer (ACEA Biosciences). The results were analyzed by Flow Jo software (BD bioscience).

Experimental model in vivo and subject details

All animal protocols described in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC: 2018120202) at The Kanion Parmaceutical. C57BL/6 female mice (purchased from The Comparative medicine center of Yangzhou University) with 6–8 weeks of age were used. To generate tumor model, 5 × 105 LLC cells/mouse were injected into the flanks of mice. Licorice (200 mg/kg of body weight) was administered daily by gastric gavage from day 2 after inoculation; Anti-PD-L1 (B7-H1) (10F.9G2) (BE0101, BioXCell) was administered by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection on day 4, 7, and 10 after inoculation (200 ug of each mouse); control mice were treated with vehicle (0.9% NaCL) 5 ml/kg by i.p. injection. Tumor volume was measured once every two days when diameter of tumor reached 5 × 5 mm, and tumor volume was calculated by using the formula: 1/2 × length × width2. Mice with tumors greater than 2000 mm3 were sacrificed and tumors were collected and snap-frozen. And mice body weight of all the groups was also recorded every three days during the experiment.

Real-time RT-PCR analyses

Total RNAs were extracted using the RNeasy mini kit (74106, QIAGEN), and reverse transcription reactions were performed using the Prime Script RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (RR047A, Takara). After mixing the generated cDNA templates with primers/probes and Green® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (RR820B (A × 2), Takara), reactions were performed with the Step One Plus TM Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems).

Mouse GAPDH: Forward, 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′,

Reverse, 5′-GGGGTCGTTGATGGCAACA-3′;

Mouse Tap1: Forward, GGACTTGCCTTGTTCCGAGAG,

Reverse, GCTGCCACATAACTGATAGCGA;

Mouse Tap-2: Forward, CTGGCGGACATGGCTTTACTT,

Reverse, CTCCCACTTTTAGCAGTCCCC;

Mouse Tap-bp: Forward, GGCCTGTCTAAGAAACCTGCC.

Reverse, CCACCTTGAAGTATAGCTTTGGG.

Mouse Erap1: Forward, TAATGGAGACTCATTCCCTTGGA.

Reverse, AAAGTCAGAGTGCTGAGGTTTG.

Single cell generation from tumor tissue and flow cytometry analysis

Tumor tissues were minced and digested with Collagenase IV (2 mg/ml, 17104-019, Gibco) and DNase I (2000U/ml, D7073, Beyotime) and Hyaluronidase (0.5 mg/ml, S10060, YuanYe Biotechnology) and Dispase II (0.5 mg/ml, S25046, YuanYe Biotechnology) in DMEM for 30 min at 37 °C. Cells were then collected by centrifuge and filtered through a 70 μm strainer (15–1070 BIOLOGIX) in DMEM. Cell pellets were suspended and lysed in red blood cell lysis buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) for 5 min. The cells were then filtered through a 40 μm strainer (15-1040, BIOLOGIX) in 1 × PBS with 2% BSA. 1×106 cells were incubated with antibodies against Anti-mouse CD3e APC (145-2C11) (05122-80-25, Biogems), Anti-mouse CD8a PE (53-6.7) (100707, BioLegend), Anti-mouse CD45 PE/Cy7 (30-F11) (103114, BioLegend) at room temperature for 30 min. Cells were washed by 1 × PBS with 2% BSA 3 times and detected by NovoCyte Flow Cytometer (ACEA Biosciences).

Elisa analysis

Cytokines of mouse serum in licorice-treated group and control group were analyzed according to the manufacturer’s recommendations: Mouse IFN-γ Immunoassay (Cat#MIF00, R&D, USA.). Absorbance was measured on a microplate reader (Molecular Devices, California, USA) using Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc.).

Quantification and statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). Two groups comparison using student’s t test. Multiple comparisons using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey test. Tumor volume were analyzed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey test. Differences were considered statistically significant at a p value ≤ 0.05. Data are presented as the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. All data shown is representative two or more independent experiments, unless indicated otherwise.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Table S1 Candidate targets for each active compound. Fig. S1 Additional file 1 Inhibition of Liquiritin on H1975 cells. Fig. S2 Typical HPLC chromatogram of licorice extract where: (1) Liquiritin, 2.28% (2) Liquiritigenin, 0.18% (3) Glycyrrhizin, 2.95% (4) Isoliquiritigenin, 0.035%. Fig. S3 Regulation of the CDK4-Cyclin D1/PD-L1 axis with GUF in A549 cells. Fig. S4 Correlation between CD8+ T cell infiltration and licorice targets in TCGA LUAD dataset and infiltration of CD8+ T cells caused by GUF in LLC mouse model.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jiangsu Kanion Pharmaceutical, Co., ltd. for helpful experimental support.

Authors' contributions

RH and JZ contributing equally to this work. RH, JZ, RY, and YX, JY carried out the experiment. RH wrote the manuscript with support from CZ and CH. WX and YW helped supervise the project. CZ and CH conceived the original idea. CZ, CH, RH and JZ revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 81803960), the 64th batch of postdoctoral general programs in China (Grant No. 2018M643723), and National Science and Technology Major Project of China (Grant No. 2019ZX09201004-001).

Availability of data and materials

All other data are included within the Article or Supplementary Information or available from the authors on request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All animal protocols described in this study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC: 2018120202) at The Kanion Parmaceutical (Lianyungang, Jiangsu,China).

Consent for publication

We would like to declare on behalf of my co-authors that the work described was original research that has not been published previously, and not under consideration for publication elsewhere, in whole or in part. No conflict of interest exits in the submission of this manuscript, and manuscript is approved by all authors for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinglin Zhu and Ruifei Huang contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Wei Xiao, Email: xw_kanion@163.com.

Chao Huang, Email: huangchao1989@nwafu.edu.cn.

Yonghua Wang, Email: yh_wang@nwafu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kao, S., et al., IGDB.NSCLC: integrated genomic database of non-small cell lung cancer. Nucleic Acids Res, 2012. 40(Database issue): p. D972–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Al-Yozbaki M. et al. Targeting DNA methyltransferases in non-small-cell lung cancer. Semin Cancer Biol, 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Pilipow K, Darwich A, Losurdo A. T-cell-based breast cancer immunotherapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Zheng H, et al. HDAC inhibitors enhance T-Cell chemokine expression and augment response to PD-1 immunotherapy in lung adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22(16):4119–4132. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards J, et al. CD103(+) tumor-resident CD8(+) T cells are associated with improved survival in immunotherapy-naive melanoma patients and expand significantly during anti-PD-1 treatment. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(13):3036–3045. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chabanon RM, et al. PARP inhibition enhances tumor cell-intrinsic immunity in ERCC1-deficient non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(3):1211–1228. doi: 10.1172/JCI123319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou Z, Lu Z-R. Molecular imaging of the tumor microenvironment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;113:24–48. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang H, Qiao J, Fu Y-X. Immunotherapy and tumor microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2016;370(1):85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2015.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Becht E, de Reyniès A, Fridman WH. Integrating tumor microenvironment with cancer molecular classifications. Genome Med. 2015;7(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13073-015-0241-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, et al. Synergistic effect and molecular mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine on regulating tumor microenvironment and cancer cells. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:1490738. doi: 10.1155/2016/1490738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He J, Yin P, Xu K. Effect and molecular mechanisms of traditional Chinese medicine on tumor targeting tumor-associated macrophages. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2020;14:907–919. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S223646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niu Y, Xu J, Sun T. Cyclin-dependent kinases 4/6 inhibitors in breast cancer: current status, resistance, and combination strategies. J Cancer. 2019;10(22):5504–5517. doi: 10.7150/jca.32628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanazawa M, et al. Isoliquiritigenin inhibits the growth of prostate cancer. Eur Urol. 2003;43(5):580–586. doi: 10.1016/S0302-2838(03)00090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu YL, Kuo PL, Lin CC. Isoliquiritigenin induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest through p53-dependent pathway in Hep G2 cells. Life Sci. 2005;77(3):279–292. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jo EH, et al. Chemopreventive properties of the ethanol extract of Chinese licorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis) root: induction of apoptosis and G1 cell cycle arrest in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2005;230(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng C, Xiao Y, Chen C, Zhu, Yang R, Yan J, Huang R, Xiao W, Wang Y, Huang C (2021) Systems pharmacology: a combination strategy for improving efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Briefings Bioinfo. 10.1093/bib/bbab130 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Yang L et al. Liquiritin represses proliferation, migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells through inhibition of the miR-671/HOXB3 signaling pathway. 2020.

- 19.He S, et al. Liquiritin (LT) exhibits suppressive effects against the growth of human cervical cancer cells through activating Caspase-3 in vitro and xenograft mice in vivo. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;92:215–228. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng C, et al. Large-scale direct targeting for drug repositioning and discovery. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11970. doi: 10.1038/srep11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H, et al. A systematic prediction of multiple drug-target interactions from chemical, genomic, and pharmacological data. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(5):e37608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poulose N, et al. Genetics of lipid metabolism in prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2018;50(2):169–171. doi: 10.1038/s41588-017-0037-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bian X, et al. Lipid metabolism and cancer. J Exp Med. 2020;218(1):e20201606. doi: 10.1084/jem.20201606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L, et al. Peptide-based materials for cancer immunotherapy. Theranostics. 2019;9(25):7807. doi: 10.7150/thno.37194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu D, et al. Peptide-based cancer therapy: opportunity and challenge. Cancer Lett. 2014;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Disis ML. Immune regulation of cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4531. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Greten FR, Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and cancer: triggers, mechanisms, and consequences. Immunity. 2019;51(1):27–41. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.06.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhao H, et al. Inflammation and tumor progression: signaling pathways and targeted intervention. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):1–46. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00451-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou Y, Ho WS. Combination of liquiritin, isoliquiritin and isoliquirigenin induce apoptotic cell death through upregulating p53 and p21 in the A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;31(1):298–304. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ii T, et al. Induction of cell cycle arrest and p21(CIP1/WAF1) expression in human lung cancer cells by isoliquiritigenin. Cancer Lett. 2004;207(1):27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alao JP. The regulation of cyclin D1 degradation: roles in cancer development and the potential for therapeutic invention. Mol Cancer. 2007;6:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-6-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hitomi M, Stacey DW. Cyclin D1 production in cycling cells depends on ras in a cell-cycle-specific manner. Curr Biol. 1999;9(19):1075–S2. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(99)80476-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casey SC, et al. MYC regulates the antitumor immune response through CD47 and PD-L1. Science. 2016;352(6282):227–231. doi: 10.1126/science.aac9935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dorand RD, et al. Cdk5 disruption attenuates tumor PD-L1 expression and promotes antitumor immunity. Science. 2016;353(6297):399–403. doi: 10.1126/science.aae0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li C-W, et al. Glycosylation and stabilization of programmed death ligand-1 suppresses T-cell activity. Nat commun. 2016;7(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lim SO, et al. Deubiquitination and stabilization of PD-L1 by CSN5. Cancer Cell. 2016;30(6):925–939. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J, et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3-SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature. 2018;553(7686):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature25015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hong SH, et al. Anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic effects of Licochalcone A through ROS-mediated cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human bladder cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(15):3820. doi: 10.3390/ijms20153820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ayeka PA, et al. The immunomodulatory activities of licorice polysaccharides (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch.) in CT 26 tumor-bearing mice. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):536. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-2030-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorsson V, et al. The immune landscape of cancer. Immunity. 2018;48(4):812–830. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goel S, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;548(7668):471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature23465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen X, et al. Celastrol induces ROS-mediated apoptosis via directly targeting peroxiredoxin-2 in gastric cancer cells. Theranostics. 2020;10(22):10290–10308. doi: 10.7150/thno.46728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu X, et al. Glycyrrhizin suppresses the growth of human NSCLC cell line HCC827 by downregulating HMGB1 level. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:6916797. doi: 10.1155/2018/6916797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schade AE, et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 relieves cooperative repression of proliferation and cell cycle gene expression by DREAM and RB. Oncogene. 2019;38(25):4962–4976. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0767-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Topacio BR, et al. Cyclin D-Cdk 4,6 drives cell-cycle progression via the retinoblastoma protein's C-terminal helix. Mol Cell. 2019;74(4):758–770. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dong Y, et al. Cyclin D1-CDK4 complex, a possible critical factor for cell proliferation and prognosis in laryngeal squamous cell carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;95(4):209–215. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010720)95:4<209::AID-IJC1036>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hamilton E, Infante JR. Targeting CDK4/6 in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:129–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lingfei K, et al. A study on p16, pRb, cdk4 and cyclinD1 expression in non-small cell lung cancers. Cancer Let. 1998;130(1–2):93–101. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00115-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun H, et al. Linc00703 suppresses non-small cell lung cancer progression by modulating cyclinD1/CDK4 expression. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(11):6131–6138. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_202006_21508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin X, et al. Phosphorylated RB promotes cancer immunity by inhibiting NF-kappaB activation and PD-L1 expression. Mol Cell. 2019;73(1):22–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen L, et al. CD38-mediated immunosuppression as a mechanism of tumor cell escape from PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1156–1175. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herbst RS, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515(7528):563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iwai Y, et al. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99(19):12293–12297. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192461099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maimela NR, Liu S, Zhang Y. Fates of CD8+ T cells in tumor microenvironment. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2019;17:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2018.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lanitis E, et al. Mechanisms regulating T-cell infiltration and activity in solid tumors. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(12):xii18–32. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goel S, et al. CDK4/6 inhibition triggers anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;548(7668):471–475. doi: 10.1038/nature23465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang J, et al. Cyclin D-CDK4 kinase destabilizes PD-L1 via cullin 3–SPOP to control cancer immune surveillance. Nature. 2018;553(7686):91–95. doi: 10.1038/nature25015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ma C, et al. Immunoregulatory effects of glycyrrhizic acid exerts anti-asthmatic effects via modulation of Th1/Th2 cytokines and enhancement of CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells in ovalbumin-sensitized mice. J Ethnopharmacol. 2013;148(3):755–762. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ng SL et al. Licorice: a potential herb in overcoming SARS-CoV-2 infections. J Evid Based Integr Med. 2021; 26: 2515690X21996662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Ru J, et al. TCMSP: a database of systems pharmacology for drug discovery from herbal medicines. J Cheminform. 2014;6:13. doi: 10.1186/1758-2946-6-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu Z, et al. BATMAN-TCM: a bioinformatics analysis tool for molecular mechANism of traditional Chinese medicine. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-016-0001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng C, et al. Large-scale direct targeting for drug repositioning and discovery. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/srep11970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu H, et al. A systematic prediction of multiple drug-target interactions from chemical, genomic, and pharmacological data. Plos ONE. 2012;7(5):e37608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.UniProt C. UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Table S1 Candidate targets for each active compound. Fig. S1 Additional file 1 Inhibition of Liquiritin on H1975 cells. Fig. S2 Typical HPLC chromatogram of licorice extract where: (1) Liquiritin, 2.28% (2) Liquiritigenin, 0.18% (3) Glycyrrhizin, 2.95% (4) Isoliquiritigenin, 0.035%. Fig. S3 Regulation of the CDK4-Cyclin D1/PD-L1 axis with GUF in A549 cells. Fig. S4 Correlation between CD8+ T cell infiltration and licorice targets in TCGA LUAD dataset and infiltration of CD8+ T cells caused by GUF in LLC mouse model.

Data Availability Statement

All other data are included within the Article or Supplementary Information or available from the authors on request.