Abstract

Sexual assault (SA) often occurs in the context of substances, which can impair the trauma memory and contribute to negative cognitions like self-blame. Although these factors may affect posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) treatment, outcomes for substance-involved SA have not been evaluated or compared with other types of SA. As such, we conducted a secondary analysis of a dismantling trial for cognitive processing therapy (CPT), focusing on 58 women with an index trauma of SA that occurred since age 14. Women who experienced a substance-involved SA (n = 21) were compared with those who experienced a non–substance-involved SA (n = 37). Participants were randomized to CPT, CPT with written account (CPT+A), or written account only (WA). Regressions controlling for pretreatment symptom levels revealed no differences by SA type in PTSD severity at posttreatment. At 6-month follow-up, substance-involved SA was associated with more severe residual PTSD severity than non–substance-involved SA, with no significant differences by treatment condition. Among participants in the substance-involved SA group, the largest effect for reduced PTSD symptom severity from pretreatment to follow-up emerged in the CPT condition, d = −2.02, with reductions also observed in the CPT+A, d = −0.92, and WA groups, d = −1.23. Although more research in larger samples is needed, these preliminary findings suggest that following substance-involved SA, a cognitive treatment approach without a trauma account may facilitate lasting change in PTSD symptoms. We encourage replications to better understand the relative value of cognitive and exposure-based treatment for PTSD following substance-involved SAs.

Sexual assault (SA) refers to unwanted sexual contact, including, but not limited to, sex without consent, known as rape. Often, SA occurs in the context of substance use, with up to half of survivors reporting they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time of SA (Kilpatrick et al., 2007). The nature and aftermath of substance-involved SAs differ in important ways from non–substance-involved SAs, which can affect PTSD symptoms and related treatment. Substance-involved SAs are often perpetrated by acquaintances (Lorenz & Ullman, 2016) and may involve less physical force when the victim is more severely intoxicated (Abbey et al., 2002). Higher levels of alcohol consumption prior to SA have been associated with the perception of a lower threat level and a lower degree of physiological fear in survivors (Clum et al., 2002). After the assault, compared to survivors of non–substance-involved SA, survivors of substance-involved SA are less likely to acknowledge the experience as “rape” (Walsh et al., 2016), seek health care (Walsh et al., 2016), or report the assault to authorities (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2011). When survivors do disclose SA, victim substance use is associated with more negative social reactions to disclosure (see Lorenz & Ullman, 2016). These reactions can be internalized or appear to confirm existing erroneous beliefs around self-blame. In turn, survivors of substance-involved SA report more negative cognitions, such as self-blame, than survivors of non–substance-involved SA (Littleton et al., 2009; Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2018). Given that alcohol is the most common substance involved in SA (Kilpatrick et al., 2007), a survivor’s memory of a substance-involved SA may also be impaired (White, 2003). Finally, recovery following substance-involved SA may follow a unique pattern, with fewer initial PTSD symptoms but a slower recovery relative to non–substance-involved SA (Gong et al., 2019).

To address PTSD following SA, psychotherapies with the strongest empirical support generally involve targeting trauma-related cognitions and/or recalling the trauma memory (Schnyder et al., 2015). One of the therapies with strong empirical support, listed as a front-line intervention across multiple treatment guidelines is cognitive processing therapy (CPT; American Psychological Association, 2017; Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense, 2017; International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, 2019). Resick and colleagues (2008) conducted a dismantling study of CPT to assess the relative efficacy of the two theorized active elements of CPT compared to the full treatment protocol. This study compared a version of CPT that included a written account of the traumatic event (CPT+A), a version that delivered CPT without the written account (CPT), and the use of a written account only (WA). Although all three conditions were shown to significantly reduce PTSD symptoms, the CPT group had lower participant dropout and a faster rate of improvement compared to the two other conditions. Based on these findings, current practice recommends using CPT without the written account (Resick et al., 2017) but continuing to offer both versions of the therapy. The treatment manual does recommend that for patients without a clear trauma memory, CPT may be the preferred option. However, few studies have directly compared these variants of CPT, and, thus, little is known about patient characteristics that predict better treatment response to CPT+A versus CPT, including the impact of trauma memories on treatment outcomes across variants of CPT.

The CPT protocol involves writing about and reflecting on the meaning and interpretation of the traumatic event. Within the context of substance-involved SA, both variants of CPT may be well-suited to address “stuck points” regarding inaccurate self-blame for substance use prior to the assault as well as difficulty accepting memory impairment for the SA, if relevant. Although technically, no specific trauma memory is required in either version of CPT, clinicians administering CPT+A are instructed to ask patients to write about what they can remember about the event, including their thoughts and feelings at the time of the trauma (Galovski et al. 2020, p. 214). For a substance-involved SA, the memory of the SA may be unclear, but other memories may be experienced as traumatic (e.g., regaining consciousness or realizing an assault occurred), which can be the focus of an account. However, case studies have described challenges with exposure-based treatments in substance-involved SA, including increased rumination when attempting to recall the assault, which may have implications for using a trauma account (Gauntlett-Gilbert et al., 2004; Padmanabhanunni & Edwards, 2013).

In sum, CPT without the written account may be best suited to address negative cognitions following substance-involved SA without activating concerns about memory impairment. To examine this possibility, we conducted a secondary analysis of data from the dismantling trial for CPT (Resick et al., 2008). Our first aim was to characterize differences between individuals in the clinical trial who had experienced substance-involved SA and non–substance-involved SA. Second, we examined the efficacy of treatment in these groups. We expected cognitive treatment only (i.e., CPT group) would outperform CPT+A and WA to a greater degree for individuals who experienced a substance-involved SA compared to those who experienced a non–substance-involved SA.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited for a larger dismantling study of CPT (Resick et al., 2008). To be included, women had to be at least 3 months posttrauma and meet the criteria for PTSD related to childhood or adulthood sexual or physical assault, as outlined in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). Exclusion criteria were illiteracy; current psychosis; suicidal intent; current abusive relationship; currently being stalked; unstable medication regimen; substance dependence, if not abstinent for 6 months; and substance abuse, if a participant did not agree to abstain from substance use during treatment. The intent-to-treat sample for the larger trial consisted of 150 women. Given the focus of the current study on victim substance use prior to sexual assault, analyses were further limited to the 61 women with an index trauma for which such substance use is particularly common: SA in adolescence or adulthood (i.e., since age 14 years, with age criteria consistent with Koss et al., 2007). Regarding other trauma types represented in the larger study but not included in the current analyses, substance involvement was reported by two of 46 individuals with an index physical assault and zero of 40 individuals with an index childhood sexual assault (i.e., before 14 years of age). Three individuals did not report their age or the date at the time of the sexual assault; because we could not confirm the index assault occurred at 14 or later, these participants were excluded from analyses. An additional three participants were excluded for unclear substance involvement (i.e., two participants indicated they were “not sure,” and one participant had a missing response). Thus, the final analytic sample included 58 participants. The mean participant age was 33.52 years (SD = 13.52, range: 18–74 years), and the majority of the sample was White (69.0%), single (60.3%), and reported an annual income under $30,000 (USD; 66.1%).

Procedure

Participants were recruited from a city in the Midwestern United States through victim assistance agencies, therapists, flyers, newspaper advertisements, and word of mouth. Interested individuals completed a telephone screening, provided written informed consent, and completed a baseline (i.e., pretreatment) assessment. Participants were randomly assigned to one of the following treatment conditions: cognitive therapy only (i.e., CPT; Resick et al., 2008), CPT with a written account (CPT+A; Resick, 2001; Resick & Schnicke, 1993), or written account only (WA; see Resick et al., 2008). The CPT intervention involves addressing beliefs about the meaning and implications of the traumatic event through cognitive restructuring. The account component of the CPT+A and WA interventions involves writing and reading a detailed recollection of the trauma memory, followed by Socratic dialogue with the therapist. Treatments were matched for contact time, with each condition receiving 12 hr of therapy within a 12-week period. Both CPT and CPT+A involved 12 twice-weekly, 60-min sessions. The WA condition involved two 60-min sessions in the first week followed by five weekly 120-min sessions. Additional assessments were completed posttreatment (i.e., 2 weeks after treatment ended) and at a 6-month follow-up assessment. All procedures were approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board.

Measures

Substance-Involved SA

The Standardized Trauma Interview, adapted from Resick et al. (1988), was used to assess trauma history, including the details of the index (i.e., most distressing) SA. To assess substance involvement, participants were asked whether they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time of the index trauma, with response options of “no” (0), “yes” (1), or “not sure” (2). If a participant answered “yes,” they were asked about the type and quantity of substances, allowing for open-ended responses, and whether they experienced impairment in each of the following domains: attention or memory, incoordination, unsteady gait, slurred speech, inadvertent rolling of eyes (nystagmus), and stupor or coma, with response options for each domain of “no” (0) or “yes” (1).

Additional SA Characteristics

The Standardized Trauma Interview (Resick et al., 1988) involved additional questions to further characterize the index SA. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they feared serious injury or being killed at the time of the traumatic event, scoring responses on a scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (I thought about it all of the time). Participants reported the nature of their relationship with the perpetrator (i.e., “yes” or “no” responses in relation to eight types of relationships) and clarified the number of perpetrators via an open-ended response question. Perpetrator type was recoded to represent five mutually exclusive categories: (1) stranger (“stranger” or “seen before, but never talked to assailant”), (2) acquaintance (“talked to assailant but was not a friend,” date, co-worker/boss, friend), (3) intimate partner (i.e., boyfriend, girlfriend, partner, spouse), (4) relative, or (5) multiple perpetrators. Participants provided “yes” or “no” responses to indicate whether the event was a completed rape (i.e., involved “forced sex”), was a part of a series of events, involved the display of a weapon by the perpetrator, or was reported to police or other authorities. Regarding experiences since the SA, participants indicated the overall quality of social support they had received, rating responses on a scale of 0 (could not have been worse) to 4 (could not have been better), with an option to specify they did not tell anyone. In addition, participants were asked to report whether their substance use decreased, increased, or did not change (i.e., remained stable) since the index SA. Although changes in alcohol and drug use were assessed separately, no participants reported an increase in one substance and a decrease in another. Thus, any change in alcohol or other drug use was summarized in a single variable.

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

The Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-IV; Blake et al., 1995) was used to assess PTSD symptom severity in accordance with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria. The CAPS-IV includes 17 items, the frequency and intensity of which are rated by an interviewer on standard scales of 0 (never) to 4 (daily or almost daily) for frequency and 0 (none) to 4 (extreme) for intensity. A sum score of frequency and intensity across all times was computed to represent PTSD symptom severity, with total scores ranging from 0 to 136. The CAPS-IV has been shown to have excellent reliability and validity (Weathers et al., 2001). In the present sample, Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .76 at baseline to .91 at posttreatment and follow-up.

Data Analysis

To characterize the sample and examine differences by SA type, descriptive statistics and group comparisons were calculated using t tests, chi-square tests, and Fisher exact tests and examined using SPSS (Version 25). Then, to determine whether there were differences in treatment outcomes by SA type, intent-to-treat analyses were conducted in Mplus (Version 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, 2015) using maximum likelihood with standard errors robust to nonnormality (MLR). The severity of PTSD symptoms at posttreatment and follow-up were evaluated as outcomes that were allowed to covary. Regarding missing data, most participants completed the posttreatment (n = 47, 81.0%) and follow-up assessments (n = 49, 84.5%). There were no significant differences in survey completion by baseline PTSD severity or SA type. Covariances between predictors were estimated to retain all participants in analyses regardless of missing data. Predictors were treatment condition, represented by two dummy variables for CPT (coded as 1) and WA (coded as 1), with CPT+A entered as the reference group (coded as 0 for both dummy variables) given that it was the original format of the treatment; SA type (1 = substance-involved SA vs. 0 = non–substance-involved SA); and the interaction between treatment and SA type. To account for variability in pretreatment PTSD severity and its association with symptom severity after treatment, pretreatment PTSD severity was included as a covariate. We also examined the effect sizes for each treatment group, separated by SA type. Based on recommendations by Morris (2008), effect sizes were computed as the bias-corrected difference between mean PTSD severity scores at pretreatment and 6-month follow-up divided by the pooled pretreatment standard deviation.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Among the 58 participants who reported an adolescent or adulthood SA, 21 (36.2%) reported they were under the influence of alcohol or drugs at the time (i.e., experienced a substance-involved SA). Alcohol was the most commonly reported substance type (n = 16), although several participants reported being under the influence of other substances (i.e., crack cocaine, n = 1; marijuana laced with PCP, n = 1; Vicodin and Tylenol, n = 1), and two individuals believed they were drugged but unsure of the substance. Most participants who experienced a substance-involved SA (n = 15, 71.4%) reported at least one form of impairment, including impairment in attention or memory (n = 12), incoordination (n = 12), unsteady gate (n = 12), slurred speech (n = 7), stupor or coma (n = 6), or nystagmus (n = 3).

Descriptive characteristics, by SA type (i.e., substance-involved vs. non–substance-involved), are presented in Table 1. Compared to women who experienced a non–substance-involved SA, those who experienced a substance-involved SA reported more perceived fear and a higher likelihood of completed rape versus another form of unwanted sexual contact. Although efforts were made to exclude childhood sexual abuse experiences, defined as index SA that occurred before 14 years of age, abuse experiences still may have been represented to some degree in the non–substance-involved SA group, as indicated by a larger proportion of participants indicating that their index SA was part of a series of events and perpetrated by a relative. However, there were no differences in other SA characteristics by substance-involvement, including the perpetrator’s display of a weapon or whether the SA was reported to police or other authorities. Only two women, both in the non–substance-involved SA group, stated they did not tell someone about the SA, and the quality of social support did not differ by SA type. Individuals in the substance-involved SA group were more likely to report having decreased their substance use since the assault than those in the non–substance-involved SA group, but there was no difference by SA type in baseline PTSD symptom severity. Random assignment did not differ by SA type, with representation in each treatment condition. In addition, treatment initiation and the number of sessions completed did not differ by SA type.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Variable | Substance-involved SA (n = 21) | Non–substance-involved SA (n = 37) | p | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||||||

| n | % | M | SD | n | % | M | SD | ||

| Baseline demographic characteristics | |||||||||

| Race | .042 | ||||||||

| White | 19 | 90.5 | 23 | 62.2 | |||||

| African American/Black | 2 | 9.5 | 13 | 35.1 | |||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.7 | |||||

| Age (years) | 29.94 | 10.14 | 35.54 | 14.85 | .131 | ||||

| Educational attainment (years) | 13.95 | 1.77 | 13.49 | 2.80 | .495 | ||||

| Baseline trauma interview | |||||||||

| Feared serious injury/killed (range: 0–4) | 2.68 | 1.46 | 1.73 | 1.58 | .032 | ||||

| SA was a completed rape (vs. other unwanted sexual contact) | 20 | 95.2 | 26 | 70.3 | .024 | ||||

| Series of events (vs. single event) | 1 | 4.8 | 10 | 31.3 | .035 | ||||

| Perpetrator status | .004 | ||||||||

| Stranger | 3 | 14.3 | 10 | 28.6 | |||||

| Acquaintance | 11 | 52.4 | 11 | 31.4 | |||||

| Intimate partner | 1 | 4.8 | 7 | 20.0 | |||||

| Relative | 0 | 0 | 6 | 17.1 | |||||

| Multiple perpetrators | 6 | 28.6 | 1 | 2.9 | |||||

| Weapon displayed by perpetrator | 3 | 15.8 | 8 | 21.6 | .732 | ||||

| Reported to police/authorities | 10 | 47.6 | 12 | 32.4 | .252 | ||||

| Quality of social support (range: 0–4) | 1.81 | 1.40 | 1.43 | 1.46 | .342 | ||||

| Substance use change since assault | .002 | ||||||||

| Decreased | 12 | 57.1 | 5 | 13.5 | |||||

| No change | 6 | 28.6 | 24 | 64.9 | |||||

| Increased | 3 | 14.3 | 8 | 21.6 | |||||

| Baseline symptoms | |||||||||

| PTSD (range: 0–136) | 72.24 | 20.00 | 73.08 | 19.22 | .875 | ||||

| Treatment | |||||||||

| Random assignment | .404 | ||||||||

| CPT | 9 | 42.9 | 11 | 29.7 | |||||

| CPT+A | 7 | 33.3 | 11 | 29.9 | |||||

| WA | 5 | 23.8 | 15 | 40.5 | |||||

| Never started treatment | 5 | 23.8 | 4 | 10.8 | .262 | ||||

| Number of sessions completed | |||||||||

| CPT (range: 0–12) | 8.78 | 4.99 | 9.55 | 4.76 | .730 | ||||

| CPT+A (range: 0–12) | 7.14 | 6.09 | 7.55 | 5.45 | .886 | ||||

| WA (range: 0–7) | 4.30 | 3.83 | 5.40 | 2.16 | .388 | ||||

Note. p values reflect differences by SA type. For continuous variables, p values correspond to t tests; for categorical variables, p values correspond to chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact test (for expected cell sizes < 5, with the Freeman-Halton extension for contingency tables larger than 2 × 2). SA = sexual assault; PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; CPT = cognitive processing therapy (cognitive only); CPT+A = cognitive processing therapy with written account; WA = written account only.

Differential Treatment Efficacy

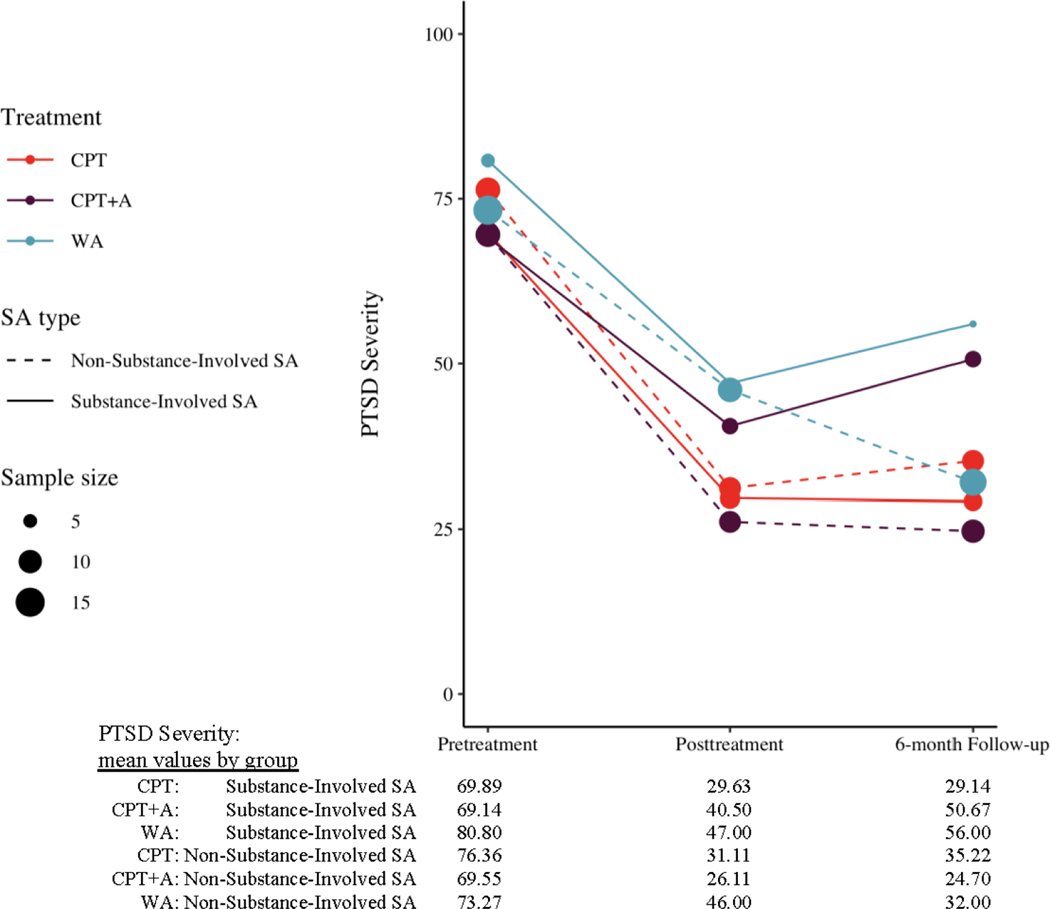

Participants’ average PTSD symptom severity, by treatment condition, SA type, and time, is represented visually in Figure 1, and the model results are shown in Table 2. After controlling for pretreatment PTSD severity, there were no significant main or interactive effects of SA type on posttreatment PTSD severity. However, there were differences at the 6-month follow-up. After controlling for pretreatment severity, a main effect revealed PTSD severity at the 6-month follow-up was higher for individuals who experienced a substance-involved SA compared to a non–substance-involved SA among individuals in the reference group (i.e., CPT+A), p = .047. This difference by SA type did not significantly differ by treatment condition.

Figure 1.

Mean Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Severity, by Treatment Condition and Sexual Assault Type

Note. CPT = cognitive processing therapy (cognitive only); CPT+A = cognitive processing therapy with written account; WA = written account only; SA = sexual assault.

Table 2.

Differential treatment efficacy on PTSD severity by sexual assault characteristics (N = 58)

| Predictor | Posttreatment PTSD severity | 6-month follow-up PTSD severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| B | SE | p | R 2 | B | SE | p | R 2 | |

| .197 | .246 | |||||||

| Pretreatment PTSD | 0.53 | 0.22 | .014 | 0.51 | 0.20 | .009 | ||

| CPT (v. CPT+A) | −0.12 | 10.97 | .991 | 5.21 | 11.52 | .651 | ||

| WA (v. CPT+A) | 19.23 | 11.00 | .080 | 3.60 | 9.68 | .710 | ||

| Substance-involved SA (vs. non–substance-involved SA) | 14.74 | 12.37 | .233 | 25.93 | 13.06 | .047 | ||

| CPT x Substance-Involved SA | −10.87 | 17.92 | .544 | −28.75 | 17.01 | .091 | ||

| WA x Substance-Involved SA | −20.63 | 19.34 | .286 | −5.88 | 19.07 | .758 | ||

Note. Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) severity at posttreatment and 6-month follow-up were allowed to covary. CPT = cognitive processing therapy (cognitive only); CPT+A = cognitive processing therapy with written account; WA = written account only, SA = sexual assault.

Regarding effect sizes, among women who experienced substance-involved SA, those assigned to CPT had a 2.02 standard deviation reduction in PTSD severity relative to 0.92 for those in the CPT+A group and 1.23 for those in the WA condition. A comparison of these values revealed a large effect for CPT relative to both CPT+A, d = −1.10; and WA, d = −0.79, among women who experienced a substance-involved SA. Among participants who experienced a non–substance-involved SA, those assigned to CPT had a 2.04 standard deviation reduction in PTSD severity, relative to 2.22 for those who received CPT+A and 2.05 for those in the WA group. Thus, the effects for treatment differences were small, ds = 0.01–0.18, among women who experienced a non–substance-involved SA.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the present study was the first to consider the differential efficacy of PTSD treatments for substance-involved SA. All treatment conditions (i.e., CPT, CPT+A, WA) evinced large treatment effects with regard to reducing SA-related PTSD severity, including among participants who experienced a substance-involved SA. Although there were no differences by SA type immediately following treatment completion, trends emerged at the 6-month follow-up assessment, providing preliminary evidence that substance involvement during SA may affect how well treatment gains are maintained. Specifically, at the 6-month posttreatment assessment, substance-involved SA was associated with a higher level of residual PTSD symptom severity compared to non–substance-involved SA. This finding builds upon prior research in samples unselected for treatment (Gong et al., 2019) and suggests that although evidence-based treatment works to substantially reduce PTSD symptoms following substance-involved SA, residual PTSD symptoms can be relatively more persistent when substances are involved in sexual trauma.

Contrary to our expectations, there were no significant differences by treatment modality depending on SA type. However, given the small sample size, we did not focus our interpretation solely on significance tests; rather, we also considered effect sizes. The results suggest that CPT without a written account demonstrated a larger effect in maintaining PTSD treatment gains following substance-involved SA than treatments involving a written account. One possible explanation is the potentially poor fit between the use of trauma accounts and substance-related impairment of the trauma memory. Indeed, past case studies (Gauntlett-Gilbert et al., 2004; Padmanabhanunni & Edwards, 2013) have suggested that individuals with amnesia related to a substance-involved SA can be distressed by the gap in memory and may believe that they will be able to fill in the gaps by recalling the memories that do exist. Although these memory processing–focused treatments were still effective in reducing PTSD symptoms among participants in the current study, such interventions may inadvertently reinforce stuck points related to memory gaps, which may contribute to higher levels of PTSD symptom persistence after treatment ends. Alternatively, an account may be helpful when a clear memory of the SA exists. This possibility is consistent with the present finding that of the three interventions, CPT+A demonstrated the largest effect size among the non–substance-involved SA group.

It is also important to note that women in all conditions experienced significant improvements in PTSD. The focus on cognitive stuck points in both variants of CPT may be important for long-term recovery, especially given that cognitions of self-blame are often prominent following substance-involved SA (Littleton et al., 2009; Peter-Hagene & Ullman, 2018). Clinicians should be alerted to the fact that stuck points specific to substance-involved SA might exist and work to tease them out. These stuck points can involve self-blame around substance use as well as an individual’s potential memory impairment.

The present findings should be interpreted in the context of the current treatment-seeking sample, which evidenced different characteristics for substance-involved SA than is typical in community and college samples. In the present study, women who experienced substance-involved SA reported more peritraumatic fear and similar rates of reporting the SA to authorities compared to those who experienced non–substance-involved SA, which is in contrast to patterns observed in broader SA research (e.g., Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2011). In addition, in contrast to prior work in community samples that has suggested women who disclose substance-involved SA commonly experience negative social reactions (Lorenz & Ullman, 2016), the quality of social support did not differ by type of SA in the present study. Further, past work with college students has shown substance-involved SA to be prospectively associated with heavier alcohol use (Kaysen et al., 2006); however, in the current clinical sample, which excluded individuals with substance dependence, substance-involved SA was associated with self-reported decreases in substance use following the traumatic event. Although measurement error, small sample size, and differences in assessment measures may have contributed to these unexpected findings, this pattern may also reflect that women who experience substance-involved SA are generally less likely to seek health care services than women who experience other types of SA (Walsh et al., 2016). Thus, survivors of substance-involved SA who presented to the current PTSD treatment study may be different from those who present to other types of research. For example, compared to women in the general population with a history of substance-involved SA, the substance-involved SA group in the current sample may have had higher-than-average levels of postassault support to facilitate reporting and treatment-seeking.

In addition to the small sample size, additional limitations merit noting. First, analyses to characterize the sample revealed that whether substances were used prior to the SA was associated with various demographic and SA characteristics. Although the sample size was too small to evaluate whether related characteristics may better explain differences in PTSD treatment outcomes, we encourage future researchers to disentangle the effects of substance involvement at the time of the SA from related demographic and SA characteristics. Second, although we considered differences in PTSD treatment outcomes between individuals who experienced substance-involved and non–substance-involved SA, the current sample was too small to explore possible mechanisms for such differences. It is possible that treatments that focus on trauma memory processing may be less appropriate for patients with substance-related impairment in SA memory. Alternatively, CPT may be better able to address maladaptive cognitions in-depth following substance-involved SA given that CPT includes more time for cognitive processing than CPT+A. We encourage future studies to examine these possibilities. In addition, although CPT+A is not considered an exposure-based therapy, these findings may have implications for other therapies that do focus more specifically on the processing of trauma memories, such as prolonged exposure, written exposure therapy, and narrative exposure therapy. Future research should operationalize what is a “sufficient” memory to engage in these exposure-based treatments. Finally, although participants most frequently reported alcohol as the substance involved in the SA, the physiological effects of other substances and their specific relation to treatment outcomes merit further study.

Overall, the present findings highlight that although some PTSD treatments may be somewhat less effective for substance-involved SA in the long-term, they can still lead to substantive treatment gains. These preliminary findings also highlight the potential that cognitive therapy treatments may be preferred for this type of Criterion A index traumatic event. In the present study, CPT led to especially large effects, and this intervention may sidestep challenges that stem from recalling substance-involved SA while still addressing trauma-related cognitions to facilitate long-term relief from PTSD symptoms. The present findings also indicate that booster sessions—while not included in the current study—may be considered to maintain treatment gains for PTSD related to substance-involved SA. Finally, these findings from a small sample suggest future studies should consider the role of substance use at the time of the traumatic event in PTSD treatment outcomes.

Open Practices Statement

The study reported in this article was not formally preregistered. Neither the data nor the materials have been made available on a permanent third-party archive; requests for the data or materials should be sent via email to Dr. Patricia Resick at patricia.resick@duke.edu.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH51509, PI: Patricia A. Resick). Manuscript preparation was supported by grants from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (T32AA007455, PI: Mary Larimer; R01AA020252, PIs: Debra Kaysen, Tracy Simpson). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism.

Debra Kaysen, Tara Galovski, and Patricia A. Resick have published books, for which they receive royalties, on the delivery of cognitive processing therapy (CPT). Debra Kaysen, Tara Galovski, and Patricia A. Resick provide training, for which they receive honoraria, to providers in the delivery of CPT.

References

- Abbey A, Clinton AM, McAuslan P, Zawacki T, & Buck PO (2002). Alcohol-involved rapes: Are they more violent? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(2), 99–109. 10.1111/1471-6402.00048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/ptsd.pdf

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, & Keane TM (1995). The development of a Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 8(1), 75–90. 10.1002/jts.2490080106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clum GA, Nishith P, & Calhoun KS (2002). A preliminary investigation of alcohol use during trauma and peritraumatic reactions in female sexual assault victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(4), 321–328. 10.1023/A:1016255929315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galovski TE, Nixon RDV, & Kaysen D. (2020). Flexible applications of cognitive processing therapy: Evidence-based treatment methods. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Keegan A, & Petrak J. (2004). Drug-facilitated sexual assault: Cognitive approaches to treating the trauma. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 32(2), 215–223. 10.1017/S1352465804001481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong AT, Kamboj SK, & Curran HV (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorder in victims of sexual assault with pre-assault substance consumption: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 92. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS). (2019). ISTSS PTSD prevention and treatment guidelines: Methodology and recommendations. https://istss.org/clinical-resources/treating-trauma/new-istss-prevention-and-treatment-guidelines [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kaysen D, Neighbors C, Martell J, Fossos N, & Larimer ME (2006). Incapacitated rape and alcohol use: A prospective analysis. Addictive Behaviors, 31(10), 1820–1832. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Ruggiero KJ, Conoscenti LM, & McCauley J. (2007). Drug-facilitated, incapacitated, and forcible rape: A national study. Medical University of South Carolina. [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, Ullman S, West C, & White J. (2007). Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31(4), 357–370. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Grills-Taquechel A, & Axsom D. (2009). Impaired and incapacitated rape victims: Assault characteristics and post-assault experiences. Violence and Victims, 24(4), 439–457. 10.1891/0886-6708.24.4.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz K, & Ullman SE (2016). Alcohol and sexual assault victimization: Research findings and future directions. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 31, 82–94. 10.1016/j.avb.2016.08.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic MB, & Resick PA (1999). The Personal Beliefs and Reactions Scale: Assessing rape-related cognitions [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Missouri—St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Morris SB (2008). Estimating effect sizes from pretest–posttest–control group designs. Organizational Research Methods, 11(2), 364–386. 10.1177/1094428106291059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/MplusUserGuideVer_7.pdf

- Padmanabhanunni A, & Edwards D. (2013). Treating the psychological sequelae of proactive drug-facilitated sexual assault: Knowledge building through systematic case-based research. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(3), 371–375. 10.1017/S1352465812000896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peter-Hagene LC, & Ullman SE (2018). Longitudinal effects of sexual assault victims’ drinking and self-blame on posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(1), 83–93. 10.1177/0886260516636394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA (2001). Cognitive processing therapy: Generic manual [Unpublished manuscript]. University of Missouri—St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Galovski TE, Uhlmansiek MO, Scher CD, Clum GA, & Young-Xu Y. (2008). A randomized clinical trial to dismantle components of cognitive processing therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in female victims of interpersonal violence. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(2), 243–258. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Jordan CG, Girelli SA, Hutter CK, & Marhoeder- Dvorak S. (1988). A comparative outcome study of behavioral group therapy for sexual assault victims. Behavior Therapy, 19(3), 385–401. 10.1016/S0005-7894(88)80011-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Monson CM, & Chard KM (2017). Cognitive processing therapy for PTSD: A comprehensive manual. Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, & Schnicke MK (1993). Cognitive processing therapy for rape victims: A treatment manual. Sage. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnyder U, Ehlers A, Elbert T, Foa EB, Gersons BPR, Resick PA, Shapiro F, & Cloitre M. (2015). Psychotherapies for PTSD: What do they have in common? European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 6(1), 28186. 10.3402/ejpt.v6.28186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense (VA/DoD). (2017). VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/MH/ptsd/VADoDPTSDCPGFinal012418.pdf

- Walsh K, Zinzow HM, Badour CL, Ruggiero KJ, Kilpatrick DG, & Resnick HS (2016). Understanding disparities in service seeking following forcible versus drug- or alcohol-facilitated/incapacitated rape. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 31(14), 2475–2491. 10.1177/0886260515576968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Keane TM, & Davidson JR (2001). Clinician‐Administered PTSD Scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety, 13(3), 132–156. 10.1002/da.1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AM (2003). What happened? Alcohol, memory blackouts, and the brain. Alcohol Research & Health, 27(2), 186–196. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Resnick HS, Amstadter AB, McCauley JL, Ruggiero KJ, & Kilpatrick DG (2011). Reporting rape in a national sample of college women. Journal of American College Health, 59(7), 582–587. 10.1080/07448481.2010.515634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]