Abstract

Bullying has severe public health consequences, due to its high prevalence worldwide and devastating effects on physical and mental health. Therefore, it is relevant to further understand the factors that contribute to the emergence and maintenance of bullying. This study aimed to examine the differential mediating role of social skills in the relationship between (i) externalizing problems and engagement in aggressive bullying behaviors, and (ii) internalizing problems and the engagement in victimization bullying behaviors. Participants were 669 Portuguese adolescents aged between 12 and 19 years. The Social Skills Improvement System-Rating Scales and the Scale of Interpersonal Behavior at School were used to assess social skills and the engagement in bullying behaviors, respectively. Boys scored higher on aggressive behaviors and externalizing problems. Girls reported higher scores on internalizing problems, communication, cooperation and empathy. Social skills differently mediated the association between behavior problems and engagement in bullying. While empathy negatively mediated the association between externalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors, assertiveness negatively mediated the relationship between internalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors. The risk factors for engaging in bullying are discussed, and so are the protective ones, which may help to prevent bullying behaviors and reduce their negative impact.

Keywords: adolescents, internalizing and externalizing problems, empathy, assertiveness, aggression, victimization

1. Introduction

Adolescence is a critical developmental period, characterized by profound physical and psychological changes, as well as by the expansion and modification of interpersonal relationships [1,2,3]. Dealing with the complexity of the relationships established at school, as one of the most important contexts in which the development occurs, makes adolescents more prone to engage in conflicts with peers [4,5,6,7,8]. Although these conflicts can be expressed in different forms, bullying is considered the most common one [9].

Bullying is a significant public health concern, with devastating effects on physical and mental health [10,11,12] and strong educational, social and political implications. With a high incidence worldwide, one in three students (32%) reported being victims of bullying at school at least once in the last month [9]. Although physical bullying is decreasing in most countries, other forms of bullying (e.g., cyberbullying) are growing [9]. In Portugal, bullying is also frequent [13], with a mean of 39% of children and adolescents reporting having been bullied by their peers at least once in the last month [9]. In a study developed by the Health Behavior in School-aged Children [14], with a sample of 6997 Portuguese adolescents aged between 12 and 16 years, 6599 (94%) adolescents identified themselves as bullies, and 6598 (94%) as victims, which highlights the high incidence of this phenomenon and the relevance of understanding it more deeply.

Due to the widely supported effects of behavioral problems on engagement in bullying, more evidence is needed to understand how socioemotional adjustment problems impact violent interactions with peers. The association between internalizing and externalizing problems with bullying [15,16,17,18,19], as well as between social skills and bullying, are widely reported [17,20,21,22,23,24]. However, evidence on how socioemotional adjustment problems and social skills interact and predict engagement in bullying behaviors is lacking. To fill this gap, this study aimed to investigate the association between externalizing and internalizing problems with bullying engagement in adolescents by exploring the differential mediating role of social skills in this association.

Bullying refers to aggressive behaviors that occur intentionally and repeatedly, over time, to harm others, in a context of observable and/or perceived power or inequity [19,25,26]. These systematic abusive behaviors aim to conquer, or maintain, a privileged social position [25].

Although direct aggression is the most obvious form of bullying behaviors, bullying also comes in indirect forms of aggression and victimization. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [9] proposed the distinction of four main types of bullying: (1) physical, (2) psychological, (3) sexual, and (4) cyberbullying. Physical bullying consists of persistent aggressions, such as making threats, kicking, hitting, hurting, pushing, shoving around or locking indoors, stealing, taking or destroying others’ personal belonging and coercing them to do things. Psychological bullying refers to verbal and emotional abusing, such as intentionally excluding or ignoring someone, insulting, teasing or spreading lies and rumors. Sexual bullying includes sexual jokes, comments or gestures to tease and humiliate someone. Cyberbullying consists of sending messages and treating others in a hurtful or cruel way through social media (i.e., texts, calls, video clips) or online (i.e., email, instant messaging, social networking, chatrooms). Despite its increasing prevalence, cyberbullying continues to be less frequent than the traditional forms of bullying [27].

Several risk and protective factors are associated with bullying behaviors [28,29]. Behavior problems and social skills are among these factors [17,28,29,30,31,32]. Internalizing and externalizing problems contribute to the maintenance and aggravation of bullying interactions [17,32,33,34]. Regarding social skills, specific abilities tend to have a differential effect on the engagement in bullying behaviors, depending on the adolescent’s role in these interactions (i.e., aggressor or victim) [31,35,36,37].

Social skills comprise interpersonal behaviors, leading to positive and adjusted responses, and avoiding negative reactions in social interactions, which allow being judged as socially competent by other/s [38,39,40]. According to Gresham et al. [40], six social skills can be defined: cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, self-control and communication. Cooperation includes helping, sharing things and rule compliance. Assertiveness refers to behaviors that arise from one’s initiative (i.e., talking about oneself and requesting information from others) or from a response to others’ actions (i.e., responding to peer group pressure), as well as to expressions of respect for oneself and others. Responsibility is associated with the ability to communicate with adults and perform requested tasks, and with concern about oneself and others. Empathy comprises the interest and concern for feelings expressed by significant figures (i.e., parents, other significant adults, teachers) and the peer group. Self-control consists of adjusted regulation of emotions, in situations of conflict (i.e., showing an adaptive response to provocations and accepting corrective feedback from adults), as well as of compliance with rules and respect for imposed limits. Communication refers to the ability to initiate and/or maintain dialogues in a proper way, and use social rules and conventions (i.e., saying please and thank you).

Evidence supports the association between social skills and engaging in bullying [17,20,21]. The relationship between social skills and bullying has been mostly studied from the victim perspective [20,22,41,42]. However, when considering both aggression and victimization bullying behaviors, some social skills have a protective role when engaging in bullying, while others make adolescents more prone to engage in these abusive behaviors [31,35,36,37]. Bullies tend to exhibit higher levels of assertiveness and lower levels of empathy, cooperation and self-control [21,23,24,43]. Therefore, bullies, especially those who are indirect aggressors, do not lack all social skills, but only specific ones, as some of them can be very effective in manipulating situations for their advantage [44,45,46]. Contrary to bullies, bullying victims tend to show lower levels of assertiveness, but, as the aggressors, they are more likely to express difficulties in cooperation and self-control [21,47].

Internalizing problems refers to difficulties in controlling both emotions and cognitions, leading to anxiety/depression symptoms, being withdrawn, or somatic complaints [48,49]. Evidence shows that internalizing problems tends to predict the engagement in victimization behaviors [32,33,34,50]. Depressive and anxiety symptoms, self-harm, and suicidal ideation are common among victims of bullying [51,52,53,54,55,56,57].

Externalizing problems are also associated with difficulties in emotion and behavior regulation, but they tend to influence the context more negatively than internalizing problems [58,59]. Externalizing difficulties are usually related to the presence of aggressive, disruptive and acting-out behaviors [48,49]. Externalizing problems are closely associated with bullying engagement [17,50], and disruptive and antisocial behaviors, such as alcohol and substance abuse, which are commonly observed among bullies [15,33,60,61]. Adolescents with externalizing problems are more likely to experiencing difficulties in reading social cues and responding to complex interactions, which can explain their increased engagement in bullying [21,31,35,36,37,62].

The association between behavior problems, social skills and engagement in bullying behaviors is extensively supported [17,28,29,30,31,32]. Both behavior problems and social skills predict engagement in bullying [16,17,18,19,30,31]. However, to the best of our knowledge, the potential mediating role of social skills in the relationship between externalizing and internalizing problems with bullying has not yet been explored. To address this gap, this study examines the potential mediating role of social skills in the relationship between (i) externalizing problems and engaging in aggressive bullying behaviors; and (ii) internalizing problems and engaging in victimization bullying behaviors. It is expected that social skills differentially mediate the relationship between externalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors, and the relationship between internalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors. Particularly, it is hypothesized that lower empathy and self-control and higher assertiveness mediate the relationship between externalizing and aggressive bullying behaviors, whereas lower assertiveness and cooperation mediate the relationship between internalizing and victimization bullying behaviors.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants were 669 adolescents (385 girls and 284 boys) aged between 12 and 19 years (M = 14.58; SD = 1.44), attending schools within the Porto district, Portugal. Of these, 243 (36.3%) attended the 9th grade, 153 (22.9%) the 8th, 95 (14.2%) the 11th, 80 (12.0%) the 10th, 53 (7.9%) the 7th, and 41 (6.1%) the 12th. Boys were aged between 12 and 19 years (M = 14.64; SD = 1.43)—106 (37.3%) attended the 9th grade, 70 (24.6%) the 8th, 39 (13.7%) the 11th, 35 (12.3%) the 10th, 20 (7.0%) the 7th, and 14 (4.9%) the 12th. Girls were aged between 12 and 18 years (M = 14.53; SD = 1.45)—137 (35.6%) attended the 9th grade, 83 (21.6%) the 8th, 56 (14.5%) the 11th, 45 (11.7%) the 10th, 33 (8.6%) the 7th, and 27 (7.0%) the 12th.

Participants were eligible if they were Portuguese speakers without cognitive difficulties—identified by the teachers—so they could, autonomously, complete the questionnaires.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Sociodemographic Questionnaire

Adolescents were invited to answer a sociodemographic questionnaire with questions about their age, sex, school grade and the city of residence.

2.2.2. Social Skills and Behavior Problems

The self-report version of Social Skills Improvement System-Rating Scales (SSIS-RS; [63,64]), was used to assess adolescents’ social skills and behavior problems. It consists of 75 items, assessed in a 4-point Likert-scale (from 0—never/almost never to 3—almost always/always). Two scales are obtained: social skills and behavior problems.

The social skills scale (composed of 46 items) consists of seven subscales: Communication (e.g., I am polite when I talk to other people), Cooperation (e.g., I follow the rules at school), Assertiveness (i.e., I ask questions when I have doubts), Responsibility (e.g., I am well-behaved), Empathy (e.g., I try to forgive when someone apologize.), Engagement (e.g., I get along with other children/adolescents.) and Self-Control (e.g., I try to find a good way to end a discussion). The behavior problems scale (composed by 29 items) consists of four subscales: Externalization (e.g., I hurt people when I feel angry), Bullying (e.g., I try to make others afraid of me), Hyperactivity/Attention Deficit (e.g., I am easily distracted) and Internalization (e.g., I get tired). The total scores for the Social Skills and Behavior Problems scales are obtained by summing the scores of the items of each subscale.

Acceptable-to-good internal consistency results were observed for the social skills and behavior problems subscales: Communication (α = 0.78), Cooperation (α = 0.76), Assertiveness (α = 0.70), Responsibility (α = 0.80), Empathy (α = 0.83), Engagement (α = 0.81), Self-Control (α = 0.76), Internalization (α = 0.83) and Externalization (α = 0.81).

2.2.3. Bullying Engagement

The Interpersonal Behavior at School (SIBS; [65]) scale was used to assess bullying engagement, both as an aggressor or as a victim. This questionnaire comprises 22 items describing aggression and victimization behaviors in bullying interactions. These items are assessed in a 4-point Likert scale (from 1 = never happens to 4 = it happens quite often). SIBS includes four scales: Verbal Aggression, Indirect Aggression, Verbal Victimization and Indirect Victimization. Verbal Aggression encompasses four items regarding verbal aggression while interacting with peers (e.g., I call names to my colleagues that hurt them). Indirect Aggression includes three items regarding aggressive behaviors aiming to withdraw and intimidate victims (e.g., I force other colleagues to do things they don’t want). Verbal Victimization includes four items referring to threats and verbal intimidation (e.g., My colleagues call me names that I don’t like). Indirect Victimization consists of three items concerning to being isolated from the group, threatened or intimidated by their peers (e.g., My colleagues ignore me). The score of each scale is obtained by summing the scores of the corresponding items. For the purpose of this study, the total score of Verbal Aggression and Indirect Aggression were summed to compute the total score of Aggression Bullying Behaviors and the scores of Verbal Victimization and Indirect Victimization were summed to obtain the total score of Victimization Bullying Behaviors.

Good internal consistency results were observed for Aggression Bullying Behaviors (α = 0.83) and Victimization Bullying Behaviors (α = 0.85).

2.3. Procedure

This study was reviewed and approved by the University Ethics Committee from the authors affiliation. Schools in the Porto district, Portugal, were contacted, and invited to participate in the study. An information document describing the study goals, instruments and procedures, as well as ensuring the confidentiality and anonymity of the data collection, was sent by e-mail to the school directors that manifested interest in participating. After giving their consent, school directors selected a teacher, or a group of teachers, to mediate communication with adolescents.

Data collection occurred between October 2020 and June 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Adolescents were asked to fill out the questionnaires online through the Google Forms platform, in the classroom under the supervision of the teacher/s. An e-mail was sent to the school directors with the link to complete the questionnaires, who forwarded it to the selected teacher/s.

The teachers in the classroom provided adolescents with information regarding the study goals, instruments and required procedures, as well as ethical issues. Then, the informed consent was given to the adolescents so their parents, or alternative legal representatives or guardians, could authorize and consent to their participation in the study. Only adolescents who volunteered to be enrolled and whose parents consented to their participation received the link to the questionnaires and participated in this investigation. Data collection lasted approximately 15 to 20 min.

2.4. Data Analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 26.0. Descriptive statistics were computed for sample characterization, with calculation of means, standard-deviations, ranges, and frequencies. A Multivariate Analysis of Variance (MANOVA) with Bonferroni corrections was performed for assessing sex differences regarding all variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the association between all variables (behavior problems, social skills and bullying behaviors). After checking statistical assumptions and correlation coefficients between all variables, two mediation models were conducted, using model 4 from PROCESS macro 3.5.2 for IBM SPSS [66], with Bootstrapping Confidence Intervals. These models assessed the relationships between (1) internalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors and (2) externalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors, both mediated by social skills (communication, cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, engagement, and self-control). Indirect effects were tested with 5000 bootstrap samples based on the 95% Bias-Corrected Bootstrap Confidence Intervals (95% BCBCI; [67]). According to exploratory analysis, variable sex should be controlled and was used as a covariate in the mediation models. Effect-size interpretation criteria (small—0.01; medium—0.09; large—0.25) was performed according to Preacher and Kelley [68], and percentage of total effect mediated was also assessed [69].

3. Results

3.1. Social Skills, Behavior Problems and Bullying

Means, standard deviations, and ranges of the responses regarding social skills, internalizing and externalizing problems, and aggressive and victimization bullying behaviors are illustrated at Table 1. Multivariate analysis of variance revealed significant main effects for sex, Wilks’ lambda = 0.82, F(11,657) = 12.83, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.177. As presented at Table 2, the univariate analysis indicated that boys scored significantly higher on aggressive behaviors (p < 0.001) and externalizing problems (p = 0.011) compared to girls, whereas girls reported higher scores on internalizing problems (p < 0.001), communication (p < 0.001), cooperation (p < 0.001), responsibility (p < 0.001), and empathy (p < 0.001), when compared with boys. Pearson’s correlation coefficients for all variables are presented at Table 2.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and range values, as well as between-sex differences results for internalizing and externalizing problems, aggressive and victimization bullying behaviors, and social skills.

| Variables | Total (N = 669) | Boys (n = 284) | Girls (n = 385) | Between-Sex Differences * | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | M (SD) | Range | F(1667) | p | η 2 | |

| Internalizing problems | 11.55 (6.06) | 0.00–30.00 | 9.90 (5.67) | 0.00–26.00 | 12.77 (6.07) | 0.00–30.00 | 38.72 | <0.001 | 0.055 |

| Externalizing problems | 8.37 (565) | 0.00–36.00 | 9.01 (5.95) | 0.00–36.00 | 7.89 (5.39) | 0.00–36.00 | 6.46 | 0.011 | 0.010 |

| Aggressive bullying behaviors | 8.32 (2.47) | 7.00–28.00 | 8.74 (2.74) | 7.00–28.00 | 8.01 (2.20) | 7.00–27.00 | 14.31 | <0.001 | 0.021 |

| Victimization bullying behaviors | 9.38 (3.26) | 7.00–28.00 | 9.36 (3.36) | 7.00–28.00 | 9.39 (3.19) | 7.00–28.00 | 0.02 | 0.886 | <0.001 |

| Communication skills | 14.73 (3.03) | 0.00–18.00 | 13.98 (3.40) | 0.00–18.00 | 15.28 (2.59) | 0.00–18.00 | 31.33 | <0.001 | 0.045 |

| Cooperation | 15.67 (3.55) | 0.00–21.00 | 14.75 (3.94) | 0.00–21.00 | 16.34 (3.07) | 0.00–21.00 | 34.51 | <0.001 | 0.049 |

| Assertiveness | 11.67 (3.99) | 0.00–21.00 | 11.46 (4.19) | 0.00–21.00 | 11.83 (3.84) | 0.00–21.00 | 1.39 | 0.240 | 0.002 |

| Responsibility | 16.81 (3.53) | 0.00–21.00 | 15.86 (4.01) | 0.00–21.00 | 17.51 (2.94) | 0.00–21.00 | 37.66 | <0.001 | 0.053 |

| Empathy | 14.29 (3.41) | 0.00–18.00 | 13.14 (3.74) | 0.00–18.00 | 15.13 (2.87) | 0.00–18.00 | 60.93 | <0.001 | 0.084 |

| Engagement | 14.36 (4.31) | 0.00–21.00 | 14.07 (4.49) | 0.00–21.00 | 14.58 (4.17) | 0.00–21.00 | 2.36 | 0.125 | 0.004 |

| Self-control | 10.73 (3.71) | 0.00–18.00 | 10.82 (3.98) | 0.00–18.00 | 10.66 (3.51) | 0.00–18.00 | 0.32 | 0.574 | <0.001 |

Note. Values are reported for the total sample (N = 669), and for boys (n = 285) and for girls (n = 385), separately. * Data for univariate tests (Multivariate analysis, F(11,657) = 12.83, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.177).

Table 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between internalizing and externalizing problems, aggressive and victimization bullying behaviors, and social skills (N = 669).

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. | 11. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Internalizing problems | - | ||||||||||

| 2. Externalizing problems | 0.37 *** | - | |||||||||

| 3. Aggressive bullying behaviors | 0.19 *** | 0.50 *** | - | ||||||||

| 4. Victimization bullying behaviors | 0.44 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.56 *** | - | |||||||

| 5. Communication skills | −0.02 | −0.32 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.17 *** | - | ||||||

| 6. Cooperation | −0.01 | −0.37 *** | −0.25 *** | −0.13 *** | 0.73 *** | - | |||||

| 7. Assertiveness | −0.018 *** | −0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.51 *** | 0.51 *** | - | ||||

| 8. Responsibility | −0.01 | −0.40 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.17 *** | 0.77 *** | 0.80 *** | 0.49 *** | - | |||

| 9. Empathy | 0.14 *** | −0.20 *** | −0.27 *** | −0.17 *** | 0.67 *** | 0.61 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.65 *** | - | ||

| 10. Engagement | −0.18 *** | −0.02 | −0.05 | −0.12 ** | 0.49 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.53 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.48 *** | - | |

| 11. Self-control | −0.13 ** | −0.28 *** | −0.15 *** | −0.15 *** | 0.48 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.31 *** | - |

Note. ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

3.2. Mediation Role of Social Skills in the Relation between Externalizing Problems and Aggressive Bullying Behaviors

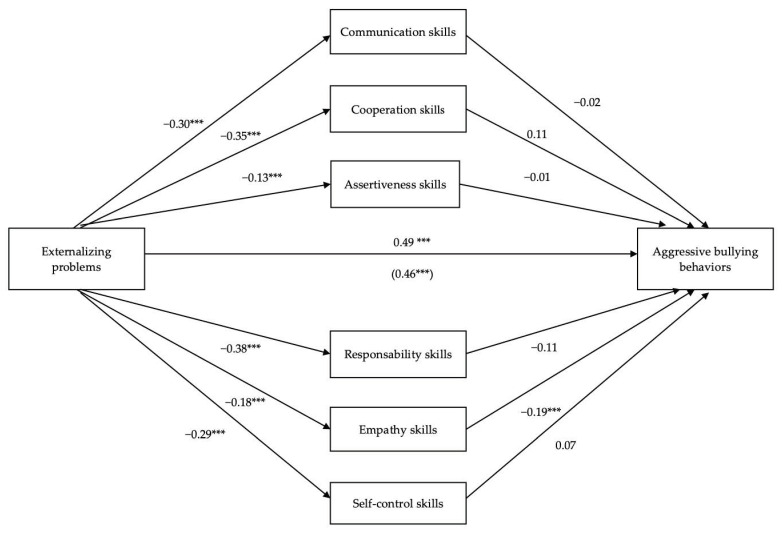

The mediation model is grounded on a variable (externalizing problems) which is theoretically suggested to predict and influence an outcome (aggressive bullying behaviors) through a set of mediating variables (social skills). Two pathways were defined by which externalizing problems may predict aggressive bullying behaviors, controlling for sex (i.e., covariable). The mediators entered into the model were communication skills, cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, and self-control (engagement was excluded due to nonsignificant statistical correlation with externalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors). The mediation model explained 28.8% of the variance of aggressive bullying behaviors, which was significant, R2 = 0.288, F(8,660) = 33.40, p < 0.0001.

The regression of externalizing problems on aggressive bullying behaviors was statistically significant, β = 0.49, SE = 0.01, t = 14.45, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI 0.18–0.24, and the covariable sex revealed a statistically significant effect, β = 0.10, SE = 0.17, t = 2.90, p = 0.004; 95% BCBCI 0.16–0.81, with boys reporting more externalizing problems and being more likely to engaging in aggressive bullying behaviors. The regression of externalizing problems on mediators was statistically significant (communication, β = −0.30, SE = 0.02, t = −8.40, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.20–−0.12; cooperation, β = −0.35, SE = 0.02, t = −9.93, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.26–−0.18; assertiveness, β = −0.13, SE = 0.03, t = −3.28, p = 0.001; 95% BCBCI −0.14–−0.04; responsibility, β = −0.38, SE = 0.02, t = −10.93, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.28–−0.20; empathy, β = −0.18, SE = 0.02, t = −4.74, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.15–−0.06; and self-control, β = −0.29, SE = 0.02, t = −7.65, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.24–−0.14). The regressions of mediators on aggressive bullying behaviors were statistically significant for empathy, β = −0.19, SE = 0.04, t = −3.81, p = 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.20–−0.07, revealing that adolescents with more externalizing problems, who express less empathy skills, engage in more aggressive bullying behaviors. Finally, the regression of externalizing problems on aggressive bullying behaviors after controlling for social skills (mediators) was significant, β = 0.47; SE = 0.02, t = 12.71, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI 0.17–0.23 (Figure 1). The mediation effect size was 0.01. Regarding percentage of mediation, 7.28% of the total effect of externalizing problems on aggressive bullying behaviors was mediated by empathy.

Figure 1.

The mediating role of social skills in the relation between externalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors (N = 669). *** p < 0.001.

3.3. Mediating Role of Social Skills in the Relationship between Internalizing Problems and Victimization Bullying Behaviors

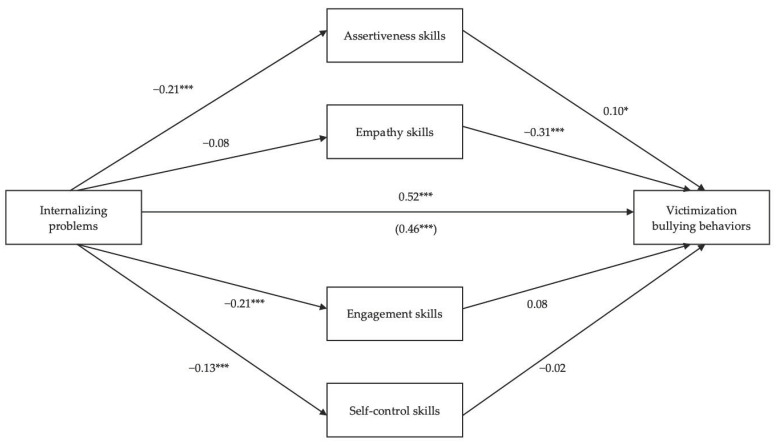

Likewise, the mediation model is supported on a variable (internalizing problems) which is theoretically suggested to predict and influence an outcome (victimization bullying behaviors) through a set of mediating variables (social skills). Two pathways are defined by which internalizing problems may predict victimization bullying behaviors, controlling for sex (i.e., covariable). The mediators entered into the model were assertiveness, empathy, engagement, and self-control (communication, cooperation, and responsibility were excluded, due to the non-significant statistical correlation with internalizing problems). The mediation model explained 26.3% of the variance of aggressive bullying behaviors, which was significant, R2 = 0.263, F(6,662) = 39.40, p < 0.0001.

The regression of internalizing problems on victimization bullying behaviors was statistically significant, β = 0.52, SE = 0.02, t = 13.05, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI 0.21–0.29, and the covariable sex revealed a statistically significant effect, β = 0.10, SE = 0.23, t = 2.90, p = 0.004; 95% BCBCI 0.22–1.14, with girls reporting more internalizing problems and being more likely to engage in victimization bullying behaviors The regression of internalizing problems on mediators was statistically significant (assertiveness, β = −0.21, SE = 0.03, t = −5.29, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.19–−0.09; engagement, β = −0.21, SE = 0.03, t = −5.32, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.20–−0.09; and self-control, β = −0.13, SE = 0.02, t = −3.27, p = 0.001; 95% BCBCI −0.13–−0.03). The regressions of mediators on victimization bullying behaviors were statistically significant for assertiveness, β = 0.10, SE = 0.03, t = 2.37, p = 0.02; 95% BCBCI 0.01–0.15, and for empathy, β = −0.31, SE = 0.04, t = −6.66, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI −0.38–−0.21. Finally, the regression of internalizing problems on victimization bullying behaviors after controlling for social skills (mediators) was significant, β = 0.46; SE = 0.02, t = 13.05, p < 0.0001; 95% BCBCI 0.21–0.29 (Figure 2). The mediation effect size was 0.01. Regarding percentage of mediation, 4.57% of the total effect of internalizing problems on victimization bullying behaviors was mediated by assertiveness, revealing that adolescents with more internalizing problems, who express more assertiveness skills, engage more often in victimization bullying behaviors.

Figure 2.

The mediating role of social skills in the relationship between internalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors (N = 669). * p <0.05; *** p < 0.001.

4. Discussion

This study examined the potential mediating role of social skills in the relationship between (i) externalizing problems and engaging in aggressive bullying behaviors, and between (ii) internalizing problems and engaging in victimization bullying behaviors, in a sample of Portuguese adolescents. As expected, a differential mediating role of social skills was observed in the relationship between behavioral problems and the engagement in aggressive or victimization bullying behaviors. While empathy mediated the relationship between externalizing problems and engagement in aggressive bullying behaviors, assertiveness mediated the relationship between internalizing problems and engagement in victimization bullying behaviors.

4.1. Sex Differences Regarding Social Skills, Behavior Problems and Bullying

Results revealed differences between boys and girls regarding social skills, behavioral problems, and bullying. Boys reported more externalizing problems and more involvement in aggressive behaviors than girls. On the other hand, girls reported more internalizing problems, as well as more social skills—communication, cooperation, responsibility and empathy—than boys.

These results are in line with the existing literature, showing that externalizing problems are more common in boys, while internalizing problems are more frequent in girls [70,71,72,73]. These results also support the evidence that girls tend to read social cues more accurately and to respond in an appropriate way to social interactions [17,74,75], as they are more likely to exhibit higher levels of cooperation [76] and empathy skills, compared to boys [77].

4.2. Association between Externalizing Problems and Aggressive Bullying Behaviors Mediated by Social Skills

These results indicated a positive association between externalizing problems and engagement in aggressive bullying behavior. The effect of externalizing problems on engagement in aggressive behaviors is extensively described [17,33,61,62]. In addition, boys presented greater externalizing problems, which were negatively associated with social skills, particularly poorer communication, cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy and self-control abilities. This is in line with other evidence indicating that socioemotional maladjustment may be related to dysfunctions in social abilities, promoting involvement in bullying [44,45,46].

Importantly, the association between externalizing problems and aggressive bullying behaviors was mediated by empathy. In accordance with other evidence, boys who present lower empathy levels tend to engage in more aggressive behaviors [78]. This is further corroborated by the negative association observed between empathy and aggressive bullying behaviors. Evidence is consistent in demonstrating that those who cannot be interested or demonstrate concern about others’ feelings are more likely to enroll in hostile behaviors [43].

This result may yield important cues for interventional approaches. It suggests that empathy may be used as a protective factor for adolescents who exhibit externalizing problems. It may be that increasing interest and concern about others, thus express more empathy within peer interactions, may prevent engagement in aggressive bullying behaviors. Hence, empathy may act as buffer [79], as several studies support the positive association of empathic distress, or experiencing concern for others, with prosocial behavior (e.g. [80,81,82]). Adolescents who display increased empathy are more effective in reading and responding to others’ emotions, possibly leading them to deal with conflicts with their peers more effectively by employing well-adjusted social coping mechanisms and emotionally regulated responses [83].

4.3. Association between Internalizing Problems and Victimization Bullying Behaviors Mediated by Social Skills

A positive association between internalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors was observed. Girls reported more internalizing problems, which were associated with poorer assertiveness, engagement, and self-control abilities. This is in accordance with studies indicating that poorer social skills may promote depressed/anxious states, which, in turn, promotes their role as victims of bullying [84].

Interestingly, results show that the relationship between internalizing problems and victimization bullying behaviors was positively mediated by assertiveness, contrarily to expected. It may be that internalizing symptoms, such as anxiety and depression, are possibly associated with a cognitive bias in processing information in social interactions [85,86]. This may lead adolescents to use social skills, and specifically assertiveness, in non-adaptative ways and increase the probability of being involved in conflicts with their peers, making them more prone to be victims of bullying. In line with this, the internalizing–externalizing problems’ comorbidity should also be considered, as adolescents who exhibit more socioemotional maladjustment are more likely to be less accurate while reading social interactions and, consequently, in using social skills [4,87]. Hence, they are potentially more vulnerable to be enrolled in conflicts with their peers, namely being victimized in bullying interactions.

4.4. Limitations and Future Studies

This study has some limitations. The first refers to the potential geographical bias, as only adolescents from the Porto district participated in this study. In future studies, geographical representativeness should be ensured to replicate these findings. In addition, data were collected online, preventing identification and resolution of potential difficulties during the completion of the questionnaires. Hence, it would be important to administer the questionnaires face to face, to monitor the adolescents and clarify their doubts more closely. Furthermore, only the adolescents’ perception on their bullying behaviors, social skills and behavior problems were considered. Therefore, future research should broaden the range of informants, including parents and teachers, to achieve a more accurate, valid, and ecological approach.

5. Conclusions

Considering bullying as a major public health concern [10,11,12] which demands specialized interventions for preventing its incidence, current findings are of utmost relevance and have practical implications for psychologists working with adolescents in different contexts (e.g., clinical, school, community, and social), as it suggests specific social skills that should be enhanced and promoted in individual and group interventions with adolescents. For adolescents with externalizing problems and who engage in aggressive bullying behaviors, interventions should focus on developing empathy skills to foster a compassionate understanding of emotions, feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of others, encouraging interactions supported by kindness, solidarity and engagement, whereas for adolescents with internalizing problems and who are often victimized in bullying situations, interventional programs should emphasize assertiveness skills, such as the expression of one’s emotions, feelings, beliefs and desires in a self-confident and effective way. Assertiveness is a marker of self-efficacy and a key component of self-advocacy, when interacting with peers. Promoting more realistic self-image, less self-blame and strategies to speak up against victimization may contribute to reducing engagement in bullying behaviors [84].

This study extends the existing evidence by exploring the differential impact of social skills on the relationship between behavioral problems and bullying behaviors. These results highlight the importance of developing promotional, preventive, and remediation interventions in schools to mitigate socioemotional adjustment problems as psychopathology precursors, and to foster social skills, to prevent bullying behaviors and reduce their effects on peer interactions, as well as on adolescents’ mental and physical health. These interventions will possibly help children and adolescents in dealing with behavioral problems, as well as to communicate and solve conflicts with their peers more effectively, thus contributing to their socioemotional adjustment. Reducing bullying behaviors is imperative, and current findings suggest different pathways to minimize both aggression and victimization bullying behaviors through endorsing and promoting social skills in adolescents.

In addition, the present study emphasizes the need to conduct further studies to deeper understand how specific internalizing and externalizing symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, oppositional and defiant behaviors, interact with certain social skills in predicting engagement in bullying behaviors.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all of the adolescents for engaging in this study. We also thank the collaboration of schools, teachers, and families. We are grateful to Ana Tomás de Almeida, for their kindness in sharing the Interpersonal Behavior at School Scale (SIBS), and to Maria Adelina Barbosa-Ducharne and Joana Soares for their availability in sharing the Social Skills Improvement System-Rating Scales (SSIS-RS).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.L.d.S. and S.F.C.; methodology, M.L.d.S. and S.F.C.; software, M.M.P.; formal analysis, M.M.P.; investigation, M.L.d.S. and S.F.C.; resources, M.L.d.S. and S.F.C.; data curation, M.L.d.S. and S.F.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.d.S., M.M.P. and S.F.C.; writing—review and editing, M.L.d.S., M.M.P. and S.F.C.; project administration, M.L.d.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted at the Centro de Investigação em Psicologia para o Desenvolvimento (CIPD) [The Psychology for Positive Development Research Center] (UID/PSI/04375), Lusíada University-North, Porto, supported by national funds through the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., and the Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education (UID/PSI/04375/2019).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Lusíada University (UL/CE/PSI/200025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was given to the adolescents’ parents, alternative legal representatives or guardians who could authorize and consent their participation in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available upon request to the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Darjan I., Negru M., Dan I. Self-esteem—The decisive difference between bullying and asertiveness in adolescence? J. Educ. Sci. 2020;41:19–34. doi: 10.35923/JES.2020.1.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deniz M.E., Ersoy E. Examining the Relationship of Social Skills, Problem Solving and Bullying in Adolescents. Int. Online J. Educ. Sci. 2015;8 doi: 10.15345/iojes.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Senna S.R.C.M., Dessen M.A. Contribuições das teorias do desenvolvimento humano para a concepção contemporânea da adolescência. Psicol. Teor. Pesqui. 2012;28:101–108. doi: 10.1590/S0102-37722012000100013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bornstein M.H., Hahn C.-S., Haynes O.M. Social competence, externalizing, and internalizing behavioral adjustment from early childhood through early adolescence: Developmental cascades. Dev. Psychopathol. 2010;22:717–735. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gonzalez E., Marques S., Pinto A., Vaz F. Exclusão social: Bullying na infância e na adolescência. Percursos. 2009;4:3–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janssen I., Craig W.M., Boyce W.F., Pickett W. Associations Between Overweight and Obesity With Bullying Behaviors in School-Aged Children. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1187–1194. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee K., Dale J., Guy A., Wolke D. Bullying and negative appearance feedback among adolescents: Is it objective or misperceived weight that matters? J. Adolesc. 2018;63:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sentse M., Prinzie P., Salmivalli C. Testing the Direction of Longitudinal Paths between Victimization, Peer Rejection, and Different Types of Internalizing Problems in Adolescence. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2017;45:1013–1023. doi: 10.1007/s10802-016-0216-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNESCO United Nations Educational. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. 2019. [(accessed on 2 June 2021)]. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org.

- 10.Cho S., Lee J.M. Explaining physical, verbal, and social bullying among bullies, victims of bullying, and bully-victims: Assessing the integrated approach between social control and lifestyles-routine activities theories. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018;91:372–382. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNESCO United Nations Educational. School Violence and Bullying: Global Status Report. 2017. [(accessed on 29 September 2021)]. Available online: http://www.infocoponline.es/pdf/BULLYING.pdf.

- 12.Tsitsika A.K., Barlou E., Andrie E., Dimitropoulou C., Tzavela E.C., Janikian M., Tsolia M. Bullying Behaviors in Children and Adolescents: “An Ongoing Story”. Front. Public Health. 2014;2:7. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mira A., Verdasca J., del Barco B.L., Felipe E., Gómez T. Bullying Escolar Em Escolas De Ensino Básico E De Ensino Secundário Do Alentejo (Portugal) Educ. Temas Probl. 2017;17:55–78. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matos M., Social E.A. A Saúde dos Adolescentes Portugueses Após a Recessão. HBCS. Dados Nacionais. 2018. [(accessed on 21 June 2021)]. Available online: http://aventurasocial.com/publicacoes/publicacao_1545534554.pdf.

- 15.Garcia-Continente X., Pérez-Giménez A., Espelt A., Adell M.N. Bullying among schoolchildren: Differences between victims and aggressors. Gac. Sanit. 2013;27:350–354. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garaigordobil M., Machimbarrena J.M. Victimization and Perpetration of Bullying/Cyberbullying: Connections with Emotional and Behavioral Problems and Childhood Stress. Psychosoc. Interv. 2019;28:67–73. doi: 10.5093/pi2019a3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins L.N., Nickerson A.B. Bystander Intervention in Bullying: Role of Social Skills and Gender. J. Early Adolesc. 2017;39:141–166. doi: 10.1177/0272431617735652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ledwell M., King V. Bullying and Internalizing Problems. J. Fam. Issues. 2015;36:543–566. doi: 10.1177/0192513X13491410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Swearer S.M., Hymel S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis–stress model. Am. Psychol. 2015;70:344–353. doi: 10.1037/a0038929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elliott S.N., Hwang Y.-S., Wang J. Teachers’ ratings of social skills and problem behaviors as concurrent predictors of students’ bullying behavior. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 2019;60:119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jenkins L.N., Demaray M.K., Fredrick S., Summers K. Associations Among Middle School Students’ Bullying Roles and Social Skills. J. Sch. Violence. 2014;15:259–278. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2014.986675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pozzoli T., Gini G. Active Defending and Passive Bystanding Behavior in Bullying: The Role of Personal Characteristics and Perceived Peer Pressure. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 2010;38:815–827. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9399-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Unnever J.D., Cornell D. Bullying, Self-Control, and Adhd. J. Interpers. Violence. 2003;18:129–147. doi: 10.1177/0886260502238731. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J., Iannotti R.J., Nansel T. School Bullying Among Adolescents in the United States: Physical, Verbal, Relational, and Cyber. J. Adolesc. Health. 2009;45:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Volk A.A., Dane A.V., Marini Z.A. What is bullying? A theoretical redefinition. Dev. Rev. 2014;34:327–343. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2014.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Menesini E., Salmivalli C. Bullying in schools: The state of knowledge and effective interventions. Psychol. Health Med. 2017;22((Suppl. 1)):240–253. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2017.1279740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feijóo S.S., O’Higgins-Norman J., Foody M., Pichel R., Braña T., Varela J., Rial A. Sex Differences in Adolescent Bullying Behaviours. Psychosoc. Interv. 2021;30:95–100. doi: 10.5093/pi2021a1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Méndez I., Esteban C.R., Lopez-Garcia J.J. Risk and Protective Factors Associated to Peer School Victimization. Original Research. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:441. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olweus D., Limber S.P. Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:124–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01015.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langeveld J.H., Gundersen K.K., Svartdal F. Social Competence as a Mediating Factor in Reduction of Behavioral Problems. Scand. J. Educ. Res. 2012;56:381–399. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2011.594614. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rupp S., Elliott S.N., Gresham F.M. Assessing elementary students’ bullying and related social behaviors: Cross-informant consistency across school and home environments. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018;93:458–466. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.08.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zych I., Farrington D.P., Llorent V.J., Ribeaud D., Eisner M.P. Childhood Risk and Protective Factors as Predictors of Adolescent Bullying Roles. Int. J. Bullying Prev. 2021;3:138–146. doi: 10.1007/s42380-020-00068-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casper D.M., Card N.A. Overt and Relational Victimization: A Meta-Analytic Review of Their Overlap and Associations With Social-Psychological Adjustment. Child Dev. 2016;88:466–483. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cosma A., Balazsi R., Băban A. Bullying victimization and internalizing problems in school aged children: A longitudinal approach. Cogn. Brain Behav. Interdiscip. J. 2018;22:31–45. doi: 10.24193/cbb.2018.22.03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Horne A., Socherman R.E. Profile of a Bully: Who Would Do Such a Thing? Educ. Horiz. 1996;74:77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perren S., Alsaker F.D. Social behavior and peer relationships of victims, bully-victims, and bullies in kindergarten. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2006;47:45–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sterzing P.R., Shattuck P.T., Narendorf S.C., Wagner M., Cooper B. Bullying Involvement and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2012;166:1058–1064. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gresham F.M., Elliott S.N. Assessment and classification of children’s social skills: A review of methods and issues. Sch. Psychol. Rev. 1984;13:292–301. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gresham F.M., Elliott S.N. Social Skills Rating System: Manual. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gresham F.M., Elliott S.N., Vance M.J., Cook C.R. Comparability of the Social Skills Rating System to the Social Skills Improvement System: Content and psychometric comparisons across elementary and secondary age levels. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011;26:27–44. doi: 10.1037/a0022662. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nickerson A.B., Mele D., Princiotta D. Attachment and empathy as predictors of roles as defenders or outsiders in bullying interactions. J. Sch. Psychol. 2008;46:687–703. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2008.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nickerson A.B., Mele-Taylor D. Empathetic responsiveness, group norms, and prosocial affiliations in bullying roles. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2014;29:99–109. doi: 10.1037/spq0000052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mitsopoulou E., Giovazolias T. Personality traits, empathy and bullying behavior: A meta-analytic approach. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2015;21:61–72. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2015.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gini G., Pozzoli T., Hauser M. Bullies have enhanced moral competence to judge relative to victims, but lack moral compassion. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2011;50:603–608. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2010.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hussein M.H. The social and emotional skills of bullies, victims, and bully–victims of Egyptian primary school children. Int. J. Psychol. 2013;48:910–921. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2012.702908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mascia M., Agus M., Zanetti M., Pedditzi M., Rollo D., Lasio M., Penna M. Moral Disengagement, Empathy, and Cybervictim’s Representation as Predictive Factors of Cyberbullying among Italian Adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2021;18:1266. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18031266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kokkinos C.M., Kipritsi E. The relationship between bullying, victimization, trait emotional intelligence, self-efficacy and empathy among preadolescents. Soc. Psychol. Educ. 2012;15:41–58. doi: 10.1007/s11218-011-9168-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Achenbach T.M. The classification of children’s psychiatric symptoms: A factor-analytic study. Psychol. Monogr. Gen. Appl. 1966;80:1–37. doi: 10.1037/h0093906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Achenbach T.M. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 Profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont; Burlington, VT, USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cook C.R., Williams K.R., Guerra N.G., Kim T.E., Sadek S. Predictors of bullying and victimization in childhood and adolescence: A meta-analytic investigation. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2010;25:65–83. doi: 10.1037/a0020149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Holt M.K., Vivolo-Kantor A.M., Polanin J.R., Holland K.M., DeGue S., Matjasko J.L., Wolfe M., Reid G. Bullying and Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135:e496–e509. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karanikola M.N.K., Lyberg A., Holm A.-L., Severinsson E. The Association between Deliberate Self-Harm and School Bullying Victimization and the Mediating Effect of Depressive Symptoms and Self-Stigma: A Systematic Review. BioMed Res. Int. 2018;2018:4745791. doi: 10.1155/2018/4745791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Myklestad I., Straiton M. The relationship between self-harm and bullying behaviour: Results from a population based study of adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10555-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klomek A.B., Barzilay S., Apter A., Carli V., Hoven C.W., Sarchiapone M., Hadlaczky G., Balazs J., Kereszteny A., Brunner R., et al. Bi-directional longitudinal associations between different types of bullying victimization, suicide ideation/attempts, and depression among a large sample of European adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2018;60:209–215. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lemstra M.E., Nielsen G., Rogers M.R., Thompson A.T., Moraros J.S. Risk Indicators and Outcomes Associated With Bullying in Youth Aged 9–15 Years. Can. J. Public Health. 2012;103:9–13. doi: 10.1007/BF03404061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Price M., Chin M.A., Higa-McMillan C., Kim S., Frueh B.C. Prevalence and Internalizing Problems of Ethnoracially Diverse Victims of Traditional and Cyber Bullying. Sch. Ment. Health. 2013;5:183–191. doi: 10.1007/s12310-013-9104-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skarstein S., Helseth S., Kvarme L.G. It hurts inside: A qualitative study investigating social exclusion and bullying among adolescents reporting frequent pain and high use of non-prescription analgesics. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s40359-020-00478-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campbell J.C., Woods A.B., Chouaf K.L., Parker B. Reproductive Health Consequences of Intimate Partner Violence. Clin. Nurs. Res. 2000;9:217–237. doi: 10.1177/10547730022158555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eisenberg N., Losoya S., Fabes R.A., Guthrie I.K., Reiser M., Murphy B., Shepard S.A., Poulin R., Padgett S.J. Parental socialization of children’s dysregulated expression of emotion and externalizing problems. J. Fam. Psychol. 2001;15:183–205. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.15.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Morris E.B., Zhang B., Bondy S.J. Bullying and Smoking: Examining the Relationships in Ontario Adolescents. J. Sch. Health. 2006;76:465–470. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2006.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Richard J., Grande-Gosende A., Fletcher É., Temcheff C.E., Ivoska W., Derevensky J.L. Externalizing Problems and Mental Health Symptoms Mediate the Relationship Between Bullying Victimization and Addictive Behaviors. Int. J. Ment. Health Addict. 2020;18:1081–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11469-019-00112-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Busch V., Laninga-Wijnen L., van Yperen T.A., Schrijvers A.J.P., De Leeuw J.R.J. Bidirectional longitudinal associations of perpetration and victimization of peer bullying with psychosocial problems in adolescents: A cross-lagged panel study. Sch. Psychol. Int. 2015;36:532–549. doi: 10.1177/0143034315604018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gresham F., Elliott S. Social Skills Improvement System: Rating Scales Manual. Pearson Education Inc.; Minneapolis, MN, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barbosa-Ducharne M., Barroso R., Soares J., Cruz O., Lemos M. Escala de Habilidades Sociais e Problemas de Comportamento—Versão de Auto-Resposta Para Adolescentes (EHSPC-A) Faculty of Psychology and Sciences of Education, University of Porto; Porto, Portugal: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Almeida A. Escala de Comportamentos Interpessoais em Contexto Escolar (ECICE) School of Psychology, University of Minho; Braga, Portugal: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hayes A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach. The Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Preacher K.J., Hayes A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Preacher K.J., Kelley K. Effect size measures for mediation models: Quantitative strategies for communicating indirect effects. Psychol. Methods. 2011;16:93–115. doi: 10.1037/a0022658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shrout P.E., Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods. 2002;7:422–445. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Achenbach T.M., Ivanova M.Y., Rescorla L.A., Turner L.V., Althoff R.R. Internalizing/Externalizing Problems: Review and Recommendations for Clinical and Research Applications. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry. 2016;55:647–656. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Qi C.H., Kaiser A.P. Behavior Problems of Preschool Children From Low-Income Families. Top. Early Child. Spéc. Educ. 2003;23:188–216. doi: 10.1177/02711214030230040201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kramer M.D., Krueger R.F., Hicks B.M. The role of internalizing and externalizing liability factors in accounting for gender differences in the prevalence of common psychopathological syndromes. Psychol. Med. 2007;38:51–61. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rosenfield S. Gender and dimensions of the self: Implications for internalizing and externalizing behavior. In: Frank E., editor. Gender and its Effects on Psychopathology. American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; Arlington, VA, USA: 2000. pp. 23–36. (American Psychopathological Association Series). [Google Scholar]

- 74.Smith C.L., Calkins S.D., Keane S.P., Anastopoulos A.D., Shelton T.L. Predicting Stability and Change in Toddler Behavior Problems: Contributions of Maternal Behavior and Child Gender. Dev. Psychol. 2004;40:29–42. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tan K., Oe J.S., Le M.D.H. How does gender relate to social skills? Exploring differences in social skills mindsets, academics, and behaviors among high-school freshmen students. Psychol. Sch. 2018;55:429–442. doi: 10.1002/pits.22118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Abdi B. Gender differences in social skills, problem behaviours and academic competence of Iranian kindergarten children based on their parent and teacher ratings. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2010;5:1175–1179. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.256. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chaplin T.M., Aldao A. Gender differences in emotion expression in children: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2013;139:735–765. doi: 10.1037/a0030737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bacon A.M., Burak H., Rann J. Sex differences in the relationship between sensation seeking, trait emotional intelligence and delinquent behaviour. J. Forensic Psychiatry Psychol. 2014;25:673–683. doi: 10.1080/14789949.2014.943796. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lockwood P.L., Seara-Cardoso A., Viding E. Emotion Regulation Moderates the Association between Empathy and Prosocial Behavior. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e96555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eisenberg N., Fabes R.A., Spinrad T.L. Prosocial Development. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2006. pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Malti T., Gummerum M., Keller M., Buchmann M. Children’s Moral Motivation, Sympathy, and Prosocial Behavior. Child Dev. 2009;80:442–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Vaish A., Carpenter M., Tomasello M. Sympathy through affective perspective taking and its relation to prosocial behavior in toddlers. Dev. Psychol. 2009;45:534–543. doi: 10.1037/a0014322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Robson D.A., Allen M.S., Howard S.J. Self-regulation in childhood as a predictor of future outcomes: A meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 2020;146:324–354. doi: 10.1037/bul0000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fung A.L.-C. Cognitive-Behavioural Group Therapy for Pure Victims with Internalizing Problems: An Evidence-based One-year Longitudinal Study. Appl. Res. Qual. Life. 2017;13:691–708. doi: 10.1007/s11482-017-9553-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Klein A.M., De Voogd L., Wiers R., Salemink E. Biases in attention and interpretation in adolescents with varying levels of anxiety and depression. Cogn. Emot. 2017;32:1478–1486. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2017.1304359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Orchard F., Reynolds S. The combined influence of cognitions in adolescent depression: Biases of interpretation, self-evaluation, and memory. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2018;57:420–435. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Salavera C., Usán P., Teruel P. The relationship of internalizing problems with emotional intelligence and social skills in secondary education students: Gender differences. Psicol. Reflex. Crít. 2019;32:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41155-018-0115-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available upon request to the corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.