Abstract

It is important to provide nutritionally adequate food in shelters to maintain the health of evacuees. Since the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has released the “Nutritional Reference Values for Evacuation Shelters” (Reference Values) after every major natural disaster. There is clear evidence, however, that the Reference Values have only been used infrequently. This study aims to revise these guidelines to include the actual situation in the affected areas and the feasibility of the endeavor. This qualitative study uses group interviews with local government dietitians to propose revisions to Japan’s Reference Values. These revisions include the following: issuing Reference Values within 1 week of a disaster, showing one type of values for meal planning for each age group, showing the minimum values of vitamins, upgrading salt to basic components, creating three phases of nutrition (Day 1, Days 1–3, and After Day 4), stipulating food amounts rather than nutrient values, and creating a manual. Local government officials could use the Reference Values as guidelines for choosing food reserves, and dietitians could use them while formulating supplementary nutrition strategies for a model menu in preparation for disasters.

Keywords: evacuation shelter, nutrition assistance, natural disaster, public health dietitian, Japan

1. Introduction

Disaster relief and food assistance in refugee camps worldwide often use nutrition standards provided by international organizations, such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Sphere Project [1,2]. In Japan, however, after every cataclysm since the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, the government has provided national nutritional guidelines (“Nutritional Reference Values for Feeding at Evacuation Shelters”; hereafter referred to as “Reference Values”). Japan is perhaps the first country to have this kind of national standard. However, nutrition after disasters remains an ongoing concern in Japan. There is clear evidence that the Reference Values have been used only infrequently. After the Great East Japan Earthquake in 2011, only 13.8% of dietitians in the affected areas used the Reference Values [3]. According to a 2013 national survey, for instance, only 47.5% of municipalities reported knowledge regarding the Reference Values, of which only 6.5% reported using them [4]. Moreover, pneumonia resulting from poor nutrition accounts for nearly a quarter of all disaster-related deaths [5]; because evacuation shelter meals lack protein, the risk of aspiration pneumonia due to poor swallowing function is all too real [6,7]. Additionally, since the Great East Japan Earthquake, a succession of disasters involving earthquakes and torrential rain has occurred.

In emergency situations, food aid is difficult. Infants and young children are regarded as the most vulnerable, and many feeding guidelines for them during emergencies have been published [8,9,10]. However, as the global population is aging, we need to address the needs of older people as well. The United Nations High Commission for Refugees estimates that, on average, 10% of its caseload includes refugees aged >60 years [11]. Japan became an aging society (population aged 65 years and over >14%) in 1994, and the percentage of older citizens in 2020 was nearly 30%. Other developed countries will need nutritional requirements in emergencies for aged societies such as Japan in the near future.

Despite the ongoing problems surrounding nutrition after a disaster, there has been little research examining how the Reference Values have been used in actual disaster areas. The Fukushima Health Management Survey assessed dietary intake among evacuees; however, the postal survey was conducted 1 year after the Great East Japan Earthquake, and energy and nutrient intakes were not calculated [12,13].

The Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) for Japanese is revised every 5 years. Following the release of the 2020 edition of the DRIs, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) is considering establishing new Reference Values. Because simply announcing the new Reference Values is not sufficient to ensure their widespread use, it is important to consider measures for revising and publicizing the Reference Values. Therefore, in this study, we examined policies adopted toward revising and circulating the Reference Values by conducting group interviews with local government dietitians who had experience in providing food to residents following natural disasters over the past decade. Our findings contribute to the processes of designing disaster food assistance in local governments by highlighting how to develop an evidence-based, locally adapted nutritional standard for nutritionally balanced and culturally tailored diets at evacuation shelters. Public health dietitians could also use our study to revise their nutritional practices during disasters for efficient and appropriate delivery of services.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study Background

In Japan, municipalities provide primary support to disaster victims; their disaster management department establishes evacuation shelters and procures food. However, there are no dietitians, public health nurses, or other healthcare professionals in this department. Dietitians at regional prefectural public health centers support the municipalities in their jurisdiction. They procure missing items at the request of the municipalities and appropriately allocate them based on assessed needs. Additionally, they analyze dietary survey data collected from the shelters and coordinate with municipalities’ requests for external help. With technical help from prefectural dietitians, municipal dietitians, usually allocated at health departments, negotiate the nutrition packed into the bento meal boxes ordered and distributed at evacuation shelters by the disaster management department. For instance, dietitians might reduce the amount of fried foods and increase the amount of vegetables. These boxes are particularly important because survivors otherwise receive only stockpiled food and relief supplies, both of which mainly comprise carbohydrates, such as instant rice, sandwiches, and instant noodles [14].

In 2011, the MHLW provided guidelines for prefectures affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake by releasing Reference Values for meal planning at evacuation shelters in April and Reference Values for meal assessment in June (Table 1). The former indicates values of calories and four nutrients that ought to be packed into evacuation shelter meals, and the latter are used to assess the meals provided at the evacuation shelters on the basis of nutritional calculations. Since then, Reference Values for assessment have been issued to health authorities of the affected prefectures of each major natural disaster based on population composition of the affected prefecture and the Estimated Average Requirements (EAR) of the DRIs used at the time of the disaster.

Table 1.

Nutritional Reference Values at evacuation shelters (per day and per person aged 1 year and above).

| For Meal Planning (Based on RDA) a |

For Dietary Assessment (Based on EAR) b |

|

|---|---|---|

| Energy (kcal) | 2000 | 1800–2200 |

| Protein (g) | 55 | ≥55 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 1.1 | ≥0.9 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 1.2 | ≥1.0 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 100 | ≥80 |

| Date of release | 21 April 2011 | 14 June 2011 |

Note. RDA, Recommended Dietary Allowance. EAR, Estimated Average Requirement. a Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011). Nutritional Reference Values to Be Used as Near-term Targets for the Planning and Assessment of Meal Provision in Evacuation Shelters. b Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011). Implementation of Appropriate Nutrition Management in Meal Provision at Evacuation Shelters.

2.2. Study Design

In this study, we selected three prefectures, each of which was affected by one of the three major disasters in the 2010s and was informed of the Reference Values. In the first prefecture, an earthquake occurred concomitant with a tsunami buffeting the coast. The second prefecture experienced an earthquake, and 4 years after the earthquake, it experienced torrential rains. There were torrential rains in the third prefecture. The first prefecture was chosen because it had the highest number of deaths, the second prefecture because it had the most damage from the earthquake, and the third prefecture because it had the highest number of cities flooded by the rains.

We conducted group interviews with public health dietitians in each of our chosen prefectures. We selected these dietitians by asking other dietitians currently working in the relevant prefectural governments to select those who, at the time of the disaster, had provided support to disaster victims as public health dietitians. Details of the selected dietitians are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Number and categorization of local government dietitians who participated in group interviews.

| Earthquake/Tsunami (Prefecture X) |

Earthquake (Prefecture Y) |

Heavy Rain (Prefecture Z) |

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prefectural Government | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Prefecture-run Public Health Center |

1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| City-run Public Health Center | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| City Government | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Town Government | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 5 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

2.3. Dates of Interviews

The interview for Prefecture Z was conducted via Zoom on 30 September 2020, with a total of five participants: two from the prefectural government, one from a prefecture-run health center, one from a city-run health center, and one city dietitian. The interview for Prefecture X was conducted via Zoom on 1 October 2020, with a total of five participants: two from the prefectural government, one from a prefecture-run health center, one city dietitian, and one town dietitian. The interview for Prefecture Y was conducted via Zoom on 19 November 2020, with a total of three participants: one from the prefectural government, one from a prefecture-run health center, and one from a city-run health center. An interview with one city dietitian and one town dietitian from Prefecture Y, who were unable to accommodate the original schedule, was conducted via Zoom on 4 December 2020.

2.4. Interview Content

Each structured interview was approximately 2 h long and was recorded on Zoom. The interview was then transcribed by a specialist agency, and the participants checked the transcriptions. The first author served as the interviewer, and all the authors attended all the interviews. For the questions that all participants could answer (for example, questions about experiences), all participants were requested to provide answers. For questions to which not all participants might have a reply (for example, questions about new ideas or opinions on revisions to the Reference Values and food aid practices), only those with specific responses were requested to speak. The questions were divided into two topics: those related to the revision of the Reference Values and those related to the revision of the “Simulator for calculating nutritional food stocks in preparation for large-scale disasters” published by the MHLW in 2020. This study reports only responses to the former. The questions related to the former part were as follows:

-

(1)

How and for what were the Reference Values used?

-

(2)

Were the Reference Values for meal planning and assessment used separately?

-

(3)

Is there a need for Reference Values for stockpile planning that can be used during normal times?

-

(4)

Are the types of nutrients covered and the values for them acceptable as they are?

-

(5)

Are there any nutrients for which you think that new Reference Values are needed?

-

(6)

Should the priority of nutrients be indicated for each phase?

-

(7)

Are Reference Values for each age group needed?

-

(8)

Is there a need to address chronic conditions other than hypertension?

-

(9)

What is needed for the Reference Values to become more widely adopted?

2.5. Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed and approved in accordance with the provisions of the Ethics Committee for Researches of Humanities and Sciences at Ochanomizu University (Notification No. 2020-35) and the institutional ethics committees of the National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (Notification No. KENEI-139). A letter of request, an interview guide, and a research cooperation consent form were mailed to participants in advance, addressing the individuals and the heads of their affiliated organizations. Participants then sent in their signed consent forms before the interview. To avoid identifying the local governments involved, the date and name of the disasters were not given. Because we considered it necessary to indicate the order of disaster occurrence to interpret the participants’ responses, we named the prefectures X, Y, and Z based on the order in which the disasters occurred.

3. Results

Overall, we found that the Reference Values were used by the dietitians as authorized evaluation indicators to persuade disaster management officials to improve the meals at shelters. However, dietitians did not separately use the two types of Reference Values (for meal planning and for nutritional assessment) and thought that only one set was enough. Conversely, the participants agreed with the need for new Reference Values for stockpile planning because stockpile planning would offer the opportunity for every local government to recognize the need for Reference Values. The Reference Values for each age group were hardly used because participants were often unaware of them; however, these values might have been used if the participants had known about them, suggesting the importance of publicity. Because of this lack of awareness, creating a manual demonstrating how to use the Reference Values in each phase and the preparations necessary to use them was considered essential.

3.1. Use of Reference Values

Other than one prefectural dietitian in Prefecture Z, whose assigned evacuation shelter closed down within a day, all participants used the Reference Values. A Prefecture X participant from the prefectural government noted that the Reference Values could be used to persuade disaster management officials to improve the meals (Table 3).

Table 3.

How and for what were the Reference Values used? (Q1).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

| We evaluated the results of the dietary survey using DRIs; however, one month after the disaster, the MHLW provided the Reference Values to use as standards during disasters. This made it easier to persuade those in charge of supplies to prioritize improving the meals (Prefectural Government). |

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) (the statements below refer to usage during the second torrential rain disaster) |

| As this was the second disaster, the public health center took the lead in conducting a dietary survey alongside the prefectural government, establishing an assessment process using the Reference Values (Prefectural Government). A few days after the disaster, a dietary survey was conducted at two evacuation shelters where catered meal boxes were distributed (City-run Public Health Center). |

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

| To get improvements made to the meals, we needed to make proposals based on nutritional calculations. A document titled “Proposals for the Implementation of Appropriate Nutritional Management in the Provision of Meals at Evacuation Shelters” was issued in the name of the director of the prefectural health and welfare department, addressed to the heads of public health center in a core city in the prefecture, and this included the results of nutritional calculations. The Reference Values were used for this assessment (Prefectural Government). From about the third day, three boxed meals were provided each day. Just by looking at them, I could tell that they were lacking in vegetables, but I confirmed this in numerical terms by using the Reference Values (City Government). |

The separate use of Reference Values for meal planning and for assessment (Table 1), however, was more varied. Prefecture X, as an interviewee from the city government noted, could only use the Reference Values for meal planning. This was because those for assessment were not issued until 3 months after the earthquake and tsunami. Interviewees from this prefecture also noted that the values in both sets of Reference Values were quite similar, which is why individual sets of Reference Values were not necessary (Table 4). A Prefecture Y participant from the prefectural government recalled that they only used the Reference Values for assessment because they were not aware that there were two sets of values. In Prefecture Z, a city government interviewee stated that the Reference Values for meal planning were used for assessment, and interviewees again noted that only one set of Reference Values was necessary because the values in the two sets were similar to one another.

Table 4.

Were the Reference Values for meal planning and assessment used separately? (Q2).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

| As the values (for planning and assessment) do not differ much, I don’t think we need to be so strict and can just use one rounded number (City Government). |

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

| We weren’t really aware (that there were two types of Reference Values) (Prefectural Government). This group interview made us aware (of the two types of Reference Values) (Prefecture-run Public Health Center, City Government). |

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

| Complaints about the meals started to come up quite often from day 3 or 4. Once there was a significant number of people asking for a change to the meals, the upper management of the municipalities would take action; thus, it would have been helpful if the word had got to them earlier (in fact, notice of the assessment values was given about a month later). Just one would be enough (City Government). |

3.2. Need for Reference Values for Stockpile Planning

Participants from Prefecture X agreed on the need for Reference Values for stockpile planning because these values would then be shared with everyone; Reference Values issued after a disaster can only be viewed in the disaster areas (Table 5). Participants from Prefecture Y were more cautious; those from the city government likewise wanted Reference Values for stockpiling but were worried regarding whether local governments could meet the Reference Values with their stockpiling and hence recommended that minimum values be provided. The interviewee from the prefectural government stressed the need to specify food amounts rather than nutrient values and suggested that the Cabinet Office directly notify the department in charge of stockpiling. In Prefecture Z, the interviewee from the prefectural public health center again emphasized the importance of stipulating food amounts rather than nutrient values because administrative staff with no knowledge of nutrition purchased the stockpiles.

Table 5.

Is there a need for Reference Values for stockpile planning that can be used during normal times? (Q3).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

3.3. Types and Values of Nutrients Covered

When asked which of the five categories in Table 1 (for all people 1 year and older) and the four nutrients in Table 6 (for specific groups) were most helpful, participants from all the prefectures indicated that all categories in Table 1 were used. For Prefecture X, the prefectural government participant noted the difficulty in meeting the Reference Values, and the city government participant suggested that the values should be at a minimum and that not meeting them should be considered a serious liability. In Prefecture Y, the interviewees from the town and city governments observed the importance of simplifying the meal plan requirements for the bento meal box vendors. For instance, they suggested that a list of ingredients instead of nutrients would be helpful. Additionally, as with Prefecture X participants, the city government participant recommended minimum standards as more persuasive. The participants from the prefectural and city governments of Prefecture Z said that Table 1 was sufficient in the case of heavy rains where the length of evacuation and damages to commodity distribution were limited.

Table 6.

Nutritional Reference Values for meal assessment—nutrients requiring consideration for specific groups.

| Purpose | Nutrients | Considerations Relating to Specific Characteristics (Excerpt) |

|---|---|---|

| Avoiding insufficient nutrient intake |

Calcium | For bone mass accumulation, especially in 6–14-year-olds, 600 mg/day is recommended, with a varied food intake |

| Vitamin A | To prevent growth impairment, intake should be no less than 300 μg RAE/day, especially for children aged 1–5 years, and attention should be paid to the intake of main and side dishes | |

| Iron | Menstruating persons with a history of anemia should undergo professional evaluation by a physician or dietitian |

|

| Primary prevention of lifestyle-related diseases | Sodium (salt) |

To prevent hypertension, avoid excessive intake in adults, referring to the target amount |

Note. RAE, Retinol Activity Equivalent. Matters of concern regarding excessive or inadequate nutrient intake after 3 months; Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011). Implementation of Appropriate Nutrition Management in Meal Provision at Evacuation Shelters.

Interviewees also had recommendations regarding what should be included in the list of Reference Values. All prefectures agreed that sodium should be added to Table 1 (Table 7). The prefectural government interviewee in Prefecture X was reluctant to lengthen the list of Reference Values, although she recollected calculating additional values, including potassium and dietary fiber. Many of the participants from Prefecture Y likewise recommended adding dietary fiber, as did the participant from the prefectural health center in Prefecture Z. The Prefecture Z dietitians also suggested removing vitamin A.

Table 7.

Types and values of nutrients covered. (Q4 and Q5).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

3.4. Prioritizing of Nutrients

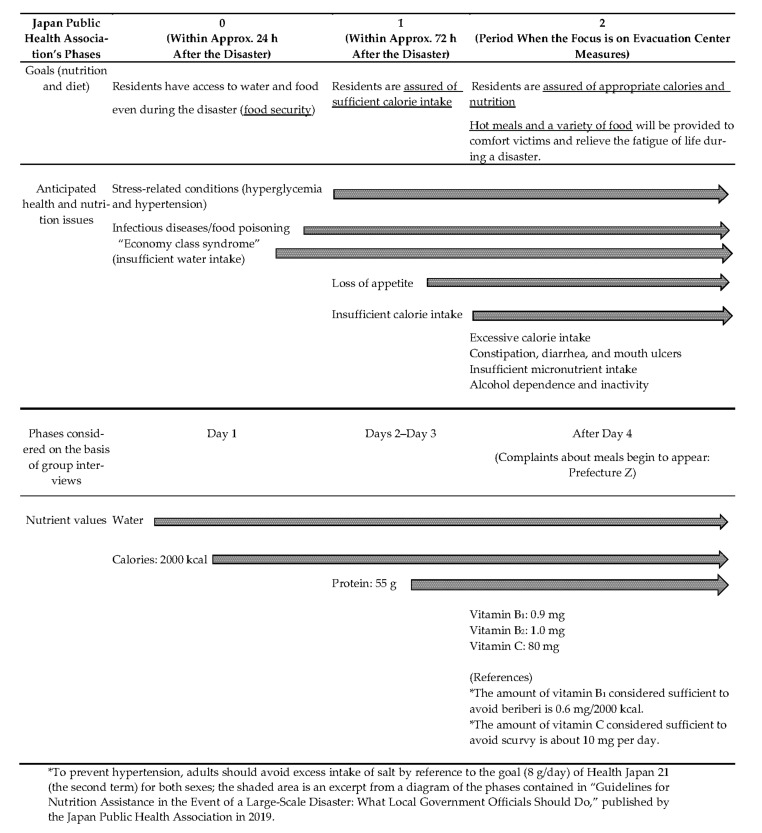

We asked whether nutrients should be prioritized according to the phases outlined in the 2011 MHLW report entitled “Lines of Thinking for Nutrition Improvement Measures at Evacuation Shelters” (Table 8), instead of the current blanket list of nutrients in Table 1 and Table 6. The participant from the prefectural public health center in Prefecture X recommended that the phases be shorter than 6 months because although the earthquake and tsunami disaster that hit the prefecture was said to be unprecedented in scale, there were only 1–2 months when food could not be purchased (Table 9). Prefecture Y’s prefectural dietitians indicated a need to be careful about the manner of presenting the information, fearing that administrative staff would say, “We have enough water and calories, so we do the meals later, right?” A participant from the city government of Prefecture Y suggested that showing the values as in Table 8 had its benefits and that there should be standard values for each phase. Just as with the participant from the prefectural public health center of Prefecture X, the prefectural public health center and city government interviewees from Prefecture Z recommended shortening the phases proposed in the MHLW 2011 report. They, in fact, specified reducing the months of the report to days or weeks in response to both health issues and complaints by residents about the meals. Additionally, the interviewee from the municipal public health center of Prefecture Z proposed that food examples be given for each phase of the diagram contained in the “Guidelines for Nutrition Assistance in the Event of a Large-Scale Disaster: What Local Government Officials Should Do,” published by the Japan Public Health Association [15], bearing in mind that non-dietitians will also look at the standard and suggest specific ingredients, such as “rice balls with a salmon filling” in place of “sweet buns,” could avoid the misconception that calorie intake alone is sufficient.

Table 8.

Lines of thinking for nutrition improvement measures at evacuation shelters (excerpt).

| Phases | Approaches to Improving Nutrition |

|---|---|

| Within 1 month |

|

| 1–3 months |

|

| 3–6 months |

|

| 6 months onwards |

|

Note. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011). Lines of Thinking for Nutrition Improvement Measures at Evacuation Shelters.

Table 9.

Should the priority of nutrients be indicated for each phase? (Q6).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

3.5. Reference Values for Each Age Group

In April 2011, the MHLW announced Reference Values (for those aged 1 year and older) in the left-hand side column of Table 1 and values for each age group in Table 10. When we asked whether Reference Values for each age group were necessary for the new Reference Values, all the interviewees from Prefecture X said that none of them used Table 10 and that it would not be necessary in the future. The participant from the city government, however, noted that she had not used Table 10 because she had not known about it (Table 11). Had she known about it, she might have used it and concluded that, following a disaster, it would be helpful to have as much information as possible Reference Values for each age group. While none of the participants from Prefecture Y used Table 10, they disagreed over whether they might have used it. The participant from the prefectural government stated that there were too many people in shelters to make sorting food according to age group viable; however, the town and city government interviewees believed that Reference Values for each age group would have helped with sorting food appropriately and quickly. The city government interviewee especially noted the difficulty of compiling meals for children. In Prefecture Z, the prefectural public health center participant remembered using Table 10 in a city, following the suggestion of the center, but one value (15–69 years old) was uniformly applied to all instead of the left-hand side column of Table 1; she could not remember the reason for which she had done so.

Table 10.

Nutritional Reference Values for planning by age group.

| Reference | Per Person Per Day | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants (Aged 1–5 Years) |

Growth Period I (Aged 6–14 Years) |

Growth Period II and Adults (Aged 15–69 Years) |

Elderly People (Aged 70 Years and above) |

|

| Energy (kcal) | 1200 | 1900 | 2100 | 1800 |

| Protein (g) | 25 | 45 | 55 | 55 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg) | 0.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.1 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 45 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

Note. Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (2011). Nutritional Reference Values to Be Used as Near-term Targets for the Planning and Assessment of Meal Provision in Evacuation Shelters.

Table 11.

Are Reference Values for each age group needed? (Q7).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

3.6. Adding Reference Values for Chronic Conditions

Of the current Reference Values, only sodium in Table 6 is set in relation to lifestyle-related diseases (the prevention of hypertension). When asked whether the new Reference Values should include nutrients to address chronic conditions other than hypertension, participants from all prefectures responded that they could not use them even if they existed and instead recommended using preexisting guidelines for each particular illness (Table 12). They offered a range of reasons for not being able to use Reference Values adjusted to particular chronic conditions. The city government and prefectural public health center participants from Prefecture X and the city government interviewee from Prefecture Z noted that it was not possible to tailor the bento meal boxes to individual patients. The city in Prefecture Z was able to provide special meals tailored to clinical conditions, diabetes, kidney disease, and dialysis patients only because of the small number of vulnerable people involved, along with assistance from the Association of Medical Doctors of Asia. The city government participant in Prefecture Y also noted that the similarity between disease guidelines for normal conditions and for disasters made it possible to use the guidelines for normal conditions when necessary after a disaster. The prefectural government participant in Prefecture Z feared that Reference Values for chronic conditions could lead to disparities among evacuation shelters as only those with external professional support could help the patients.

Table 12.

Is there a need to address chronic conditions other than hypertension? (Q8).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

3.7. Increasing the Use of Reference Values

Many of the participants in this study learned about Reference Values only because of the disaster in their prefecture. To increase awareness of the Reference Values, the Prefecture X interviewees suggested including them in the work guidelines for administrative dietitians and in the DRIs, which are covered in the on-the-job training sessions held every 5 years when the DRIs are revised (Table 13). In the Prefecture Y interview, the prefectural government participant recommended creating a manual demonstrating how to use the Reference Values in each phase and the preparations necessary for using them; she had not used them herself because she could not envision how to put them into practice. In the Prefecture Z interview, the municipal government interviewee proposed producing a website that would contain all necessary information. However, the prefectural government interviewee added that people would probably not peruse the website unless it was absolutely necessary.

Table 13.

What is needed for the Reference Values to become more widely adopted? (Q9).

| Prefecture X (Earthquake and Tsunami) |

|

| Prefecture Y (Earthquake) |

|

| Prefecture Z (Torrential Rains) |

|

4. Discussion

This study was conducted to identify the challenges of food security responses after natural disasters in Japan. To the best of our knowledge, little research has been done on the utilization of nutritional guidelines on disaster sites. This study could lay the foundation for the development of guidelines in other countries.

4.1. Use of Reference Values

It has been indicated that scientific data collection and dietary surveys following the Great East Japan Earthquake were extremely limited [16]. Dietary surveys at shelters, however, were conducted by administrative dietitians following the three major natural disasters, although these data were rarely published as a scientific paper unless researchers were involved. As the interviewees were not fully aware of the usage of Reference Values, a dietary assessment manual for shelter meals needs to be compiled. Although the Iranian Ministry of Health has proposed formulations for emergency food basket and other supporting organizations have separate guidelines in this regard, the health and nutrition controlling guidelines of the stakeholders were not implemented in critical situations after natural disasters [17]. These facts imply that the need to provide not only the guidelines but also teaching material regarding how to use them.

4.2. Need for Reference Values for Stockpile Planning

Based on the nutrient reference values published by the Australian Government, Haug et al. [18] estimated that a food stockpile should provide an average energy intake of about 2150 kcal per person per day to avoid significant weight loss. However, this is near the average intake―men need a little more than women, while children and elderly need less. The new Reference Values will also be shown in normal times for stockpile planning and provided to accommodate differences in demographic characteristics among prefectures. Schofield and Mason [19] also pointed out that using one figure for setting the rations for all populations is inappropriate.

Some governments of developed countries have published guidelines for household food stockpiling that show which foods and in what quantities people are recommended to have [20,21]. However, food and nutrition guidelines for stockpiling by local governments have never been established.

4.3. Types and Values of Nutrients Covered

The interviewees noted the difficulty in meeting the Reference Values and suggested that the values should be at a minimum. Nutritional deficiencies have been widely observed in emergencies. Further, a significant rise in the incidence of malnutrition and all forms of vitamin and micronutrient deficiency was reported after natural or man-made disasters [22]. In particular, vitamin content in most rations is inadequate because they heavily rely on cereals [23]. Previous studies have reported that a beriberi epidemic occurred in a refugee camp [24], in which 55% of ration distribution provided less than half the riboflavin Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) [25]. Although it would be cheaper and require less manpower to rely on multivitamin tablets rather than main/side dishes to cover the requirements of vitamins, Japan’s nutrition policy considers supplementation as the last option and tries to first improve diets.

4.4. Prioritizing of Nutrients

The group interviews show that food scarcity following a disaster could be resolved in two months at the longest. The Reference Values should be given in shorter phases using phases 0–2 from the Japan Public Health Association guidelines [15], and specific examples of food items should be given as in Figure 1 and Table 14.

Figure 1.

Proposed format for presenting the new nutritional reference values (white area).

Table 14.

Examples of foods for meeting the new Reference Values.

| Phases | Phase 0: Day 1 | Phase 1: Day 2–Day 3 | Phase 2: After Day 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrients to be considered and their Reference Values |

Water

Calories: 2000 kcal |

Water

Calories: 2000 kcal Protein: 55 g |

Water

Calories: 2000 kcal Protein: 55 g Vitamin B1: 0.9 mg Vitamin B2: 1.0 mg Vitamin C: 80 mg |

| Examples of foods for meeting the above Reference Values |

Day 1 Breakfast: Canned bread 100 g Water Lunch: Porridge 250 g Hardtack 100 g Water Dinner: Pregelatinized rice 100 g Rice cookies 100 g Water Calories: 1820 kcal |

Day 2 Breakfast: Udon in a cup (noodles made from wheat flour) 75 g Canned mandarin orange 50 g Water Lunch: Pregelatinized rice 100 g Vegetable mix juice 200 mL Mackerel simmered in miso sauce 90g Snack: Rice cookies 70 g Dinner: Pregelatinized rice 100 g Canned grilled chicken 75 g Canned boiled soybeans 50 g marinated with dried salty kelp 5 g Water Calories: 1924 kcal Protein: 55 g |

Day 4 Breakfast: Bread roll 30 g * 2 rolls Orange juice 150 mL Fish sausage 90 g Corn cream soup 150 g Lunch: Pregelatinized rice 100 g Chicken curry (retort) 200 g 1 banana Green tea 200 mL Snack: Dried sardine with almond 30 g Dinner: Boiled rice with barley 250 g Canned tuna and asparagus marinated with mayonnaise 70 g Miso soup with soy milk (boiled bamboo shoots 20 g, potatoes 40 g) 1 bowl Green tea 200 mL Calories: 1975 kcal Protein: 60 g Vitamin B1: 0.8 mg Vitamin B2: 1.5 mg Vitamin C: 126 mg Salt: 8.8 g |

|

Day 3 Breakfast: Porridge 250 g Canned barbecued Brevoort 50 g Biscuits 30 g Water Lunch: Canned bread 100 g Vegetable mixed juice 200 mL Canned seasoned beef 50 g Snack: Azuki-bean jelly 50 g Dinner: Pregelatinized rice 100 g Green tea 200 mL Chicken stew 200 g Canned sardines in tomato sauce 50 g Canned mandarin orange 50 g Calories: 1787 kcal Protein: 58 g |

Day 5 Breakfast: 1 sliced bread 60 g Peanut butter 13 g 1 egg 55 g Yogurt 80 g Grapefruit juice 150 mL Lunch: Fortified rice 200 g Beef stew (retort) 200 g Canned boiled soybeans 50 g Canned pineapple 50 g Green tea 200 mL Dinner: 2 rice balls with laver 250 g Canned seasoned sardines 50 g 1 tomato Somen noodles in soup with breast chicken (canned, boiled), dried white radish, brown seaweed, and dried mushrooms 180 g Green tea 200 mL Calories: 1722 kcal Protein: 60 g Vitamin B1: 1.0 mg Vitamin B2: 1.3 mg Vitamin C: 146 mg Salt: 5.5 g |

||

|

Day 6 Breakfast: Bread roll 30 g * 2 rolls Corn flakes 40 g Milk 100 g 2 slices of ham 20 g 1 cucumber 100 g 1 egg 55 g Apple juice 150 mL Lunch: Boiled rice with barley 250 g Chicken stew 200 g (with canned boiled mushrooms 30 g) Cheese 18 g 1 Mandarin orange 80 g Green tea 200 mL Dinner: Fortified rice 250 g Clams boiled in soy sauce 10 g Marinated canned tuna in oil, broccolis, and cherry tomatoes 200 g Green tea 200 mL Calories: 1872 kcal Protein: 61 g Vitamin B1: 1.2 mg Vitamin B2: 1.4 mg Vitamin C: 138 mg Salt: 6.8 g | |||

|

Day 7 Breakfast: 2 rice balls with dried bonito 250 g Fried Spam and bamboo shoots 80 g Vegetable mixed juice 200 mL Lunch: Boiled rice with barley 250 g Kenchin soup with quail eggs and tofu 250 g Canned peach 50 g Green tea 200 mL Dinner: Fortified rice 250 g Tomato soup with mackerel 300 g Green tea 200 mL Calories: 1820 kcal Protein: 60 g Vitamin B1: 1.1 mg Vitamin B2: 1.2 mg Vitamin C: 115 mg Salt: 3.1 g |

* To prevent hypertension, adults should avoid excess intake of salt by reference to the goal (8 g/day) of Health Japan 21 (the second term).

4.5. Reference Values for Each Age Group

Although a number of strategies, frameworks, policies, and guidance have been set out in relation to feeding infants and young children in emergencies, the needs of other age groups are seldom addressed [26]. Nor did our participants, except one, use Table 10. Given the variability and complexities of evacuees, however, it is evident that tailored nutrition assistance cannot be accomplished with a single template for those aged ≥1 year. In the group interviews, the participants presented some ideas of how Table 10 could be used had they known about it.

4.6. Adding Reference Values for Chronic Conditions

Many survivors of major disasters die shortly after the event, and hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for disaster-related issues [27]. Compared to nonevacuees, a greater increase in mean blood pressure was observed in evacuees after the Great East Japan Earthquake [28]. Increased exacerbations of cardiovascular diseases, including worsening control of hypertension and myocardial infarctions, with an associated increased risk of death, were observed after hurricane events associated with flooding [29]. It was reported that not only adults but also children reporting four or more traumatic experiences had marginally significant elevated levels of diastolic blood pressure [30]. Among the nine global targets for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) 2013–2020 [31], reduction of salt intake is only one dietary target and modifiable factor even in evacuation shelters. In the context of significance and implementability, hypertension might be the only chronic condition that needs to be addressed at shelters. All prefectures agreed that sodium should be added as one of the nutrients in Table 1, while they responded that they could not use other nutrients to address chronic conditions other than hypertension. Foods distributed during federal disaster relief response in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria contained a high amount of sodium [32]. High salt content in disaster food is a universally common characteristic because of food processing and long shelf life. In Caribbean regions, poor control of chronic NCDs was responsible for at least 30 percent of deaths after two recent hurricanes [33]. Management of NCDs in the setting of disasters in low- and middle-income countries would be the challenge.

4.7. Increasing the Use of Reference Values

There is currently an undergraduate education system for learning about Reference Values; however, it is limited and was put into practice after the participants in this study graduated from training colleges. In December 2010, the national examination standards for Registered Dietitian Nutritionists (RDNs) were revised to include “Health Crisis Management and Nutrition Assistance” as a sub-item of “Public Health Nutrition” and “Counter Measures for Accidents and Disasters” as a sub-item of “Food Service Management.” “Nutrition in Disasters” was then added as a sub-item of “Applied Nutrition” in February 2015. The textbooks for these specialized subjects for RDNs include tables of the Reference Values; hence, RDNs who have studied this curriculum will have learned about the Reference Values. However, the relevant sections of the textbooks vary widely in content and quantity [34], and a nationwide postal survey reported that nearly half of the students at Japan’s RDN training colleges did not understand them [35].

Provision of Reference Values for stockpile planning could get more people involved, including those without disaster experience. Creating a manual demonstrating the manner in which to use the Reference Values could contribute to detailed descriptions in the textbooks given that teachers with enough knowledge of disaster nutrition is limited [36].

5. Conclusions

This study has revealed potential ways of revising the Reference Values, circulating the revisions more widely, and examining the actual situation in Japan with respect to nutrition assistance during disasters. Based on the results of the aforementioned group interviews, a proposed policy for revising the Reference Values is outlined below.

In the event of a disaster, receiving notice from the national government serves as an impetus for disaster management staff to make improvements to meals; hence, the Reference Values tailored to age–number distribution of people in affected prefectures should be issued in writing within 1 week of the disaster.

Only one type of value for meal planning should be issued.

A manual should be created that explains different features in meal assessment at shelters where individuals’ intakes are difficult to measure. For assessment, the amount of provision should be compared with EAR and RDA of DRIs.

The Reference Values should be used under normal conditions for stockpiling. In addition to a basic standards for the whole Japanese population, an Excel Sheet that shows amounts of calories and nutrients, calculated by weighing the DRI values by the gender and age ranges of the city/town/village, should be presented to reflect differences in demographics so that each municipality can find a precise scheme.

To prevent nutritional deficiencies, current Reference Values for meal planning are RDA-based. For vitamins B1, B2, and C, however, they should be EAR-based because even EARs are set beyond the minimum necessary intake that prevents deficiencies.

A Reference Value for sodium should be added to those for calories, protein, and vitamins B1, B2, and C in Table 1. The nutrients for specific groups in Table 6 are unnecessary. Other nutrients deemed necessary in specific situations could be calculated using the DRI values.

The Reference Values should be given in shorter phases than the monthly phases in Table 8. Phases 0–2 from the Japan Public Health Association guidelines should be used, and specific examples of food items should be given (Figure 1 and Table 14).

If the Reference Values by age group are to be used as a meal plan, it would be for individualized support. The combination of relief supplies that can meet these nutritional requirements should be shown for each age group (for one meal and for 1 day), and the characteristics of particular life stages, such as infancy and old age, should be considered. Table 10 is a reference for assessing the sufficiency of nutrients for children.

There is no need to address particular medical conditions other than hypertension.

To circulate information among dietitians with no personal experience with disasters or work in disaster support and to enhance undergraduate education, the use of Reference Values should be explained in the manual.

Under normal conditions, local government officials could use Reference Values as the guideline for choosing food reserves. Dietitians could also use them while formulating supplementary nutrition strategies for creating a model menu in preparation for disasters.

In addition to the revisions of the Reference Values, the group interviews showed the importance of facilitating cooperation between different departments within the local government and among different professionals, such as dietitians, non-dietitians, and bento vendors. In future studies, we intend to conduct another round of group interviews with the same public health dietitians to confirm whether we correctly reflected their opinions in the current revisions. Furthermore, we will conduct new group interviews with disaster management personnel who are in charge of purchasing stockpile foods to check if the new Reference Values and their manual are understandable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the interviewees for their active participation in the study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.S. and N.T.-K.; methodology, N.S.; software, N.S. and I.S. and K.S.; validation, N.S., I.S. and K.S.; formal analysis, N.S., I.S. and K.S.; investigation, N.S., I.S., N.T.-K. and K.S.; resources, N.S.; data curation, N.S., I.S., N.T.-K. and K.S.; writing—original draft preparation, N.S.; writing—review and editing, N.S., I.S. and N.T.-K.; visualization, N.S. and I.S.; supervision, N.S. and N.T.-K.; project administration, N.S.; funding acquisition, N.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by a Grant-in-Aid from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Health and Labour Sciences Research Grants, Japan “Grant Number 20FA2001.”

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Ethics Committee for Researches of Humanities and Sciences at Ochanomizu University (Notification No. 2020-35) and the institutional ethics committees of the National Institutes of Biomedical Innovation, Health and Nutrition (Notification No. KENEI-139).

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the study was voluntary. Full consent of the participants was sought before the interview, and each participant signed a consent form before participating in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Sphere Association . The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response. Sphere Association; Geneva, Switzerland: 2018. pp. 157–236. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . The Management of Nutrition in Major Emergencies. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirano M., Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N., Ishikawa-Takata K., Nozue M., Takizawa A., Oka J., Sako K., Takimoto H. The recognition and usage rates of the nutritional supporting information tools for evacuees at the disaster. J. Jpn. Disaster Food Soc. 2016;3:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudo N., Matsumoto S., Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N., Yamada K., Shimoura Y. A nationwide survey on local governments’ preparedness for nutrition assistance during natural disasters: Recognition and application of “Nutritional Reference Values for Feeding at Evacuation Shelters”. J. Jpn. Disaster Food Soc. 2018;5:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adachi R. Necessity of dental health assistance. In: Nakakuki K., Kitahara M., Ando Y., editors. Dental Health Care in Disasters: Toward Cooperation and Standardization. Issei Publishing; Tokyo, Japan: 2015. pp. 116–121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudo N. What is essential quality of nursing care food? Trends Nutr. 2017;2:146–151. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N., Kondo A., Harada M., Ueda S., Sudo N., Kanatani Y., Shimoura Y., Nakakuki K. Analysis of an oral health report from dietitians dispatched to the areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake. Jpn. J. Dysphasia Rehab. 2017;21:191–199. doi: 10.32136/jsdr.21.3_191. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGrath M., Seal A., Taylor A. Infant feeding indicators for use in emergencies: An analysis of current recommendations and practice. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5:365–371. doi: 10.1079/PHN2001310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . Guiding Principles for Feeding Infants and Young Children during Emergencies. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gribble K., Peterson M., Brown D. Emergency preparedness for infant and young child feeding in emergencies (IYCF-E): An Australian audit for emergency plans and guidance. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1278. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7528-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knight L.A. Humanitarian crises and old age: Guidelines for best practice. Age Ageing. 2000;29:293–295. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang W., Ohira T., Abe M., Kamiya K., Yamashita S., Yasumura S., Ohtsuru A., Maeda M., Harigane M., Horikoshi N., et al. Evacuation after the Great East Japan Earthquake was associated with poor dietary intake; the Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. J. Epidemiol. 2017;27:14–23. doi: 10.1016/j.je.2016.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Uemura M., Ohira T., Yasumura S., Otsuru A., Maeda M., Harigane M., Horikoshi N., Nakano H., Zhang W., Hirosaki M., et al. Association between psychological distress and dietary intake among evacuees after the Great East Japan Earthquake in a cross-sectional study: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011534. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N., Hoshi Y., Onodera K., Mizuno S., Sako K. What factors were important for dietary improvement in emergency shelters after the Great East Japan Earthquake? Asia Pac. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014;23:159–166. doi: 10.6133/apjcn.2014.23.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kubo A. Guidelines for Nutrition Assistance in the Event of a Large-Scale Disaster: What Local Government Officials Should Do. Japan Public Health Association; Tokyo, Japan: 2019. p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amagai T., Ichimaru S., Tai M., Ejiri Y., Muto A. Nutrition in the Great East Japan Earthquake Disaster. Nutr. Clin. Pract. 2014;29:585–594. doi: 10.1177/0884533614543833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ainehvand S., Raeissi P., Ravaghi H., Maieki M. Natural disasters and challenges toward achieving food security response in Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2019;8:51. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_256_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haug A., Brand-Miller J.C., Christophersen O.A., McArthur J., Fayet F., Truswell S. A food “lifeboat”: Food and nutrition considerations in the event of a pandemic or other catastrophe. Med. J. Aust. 2007;187:674–676. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2007.tb01471.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schofield E.C., Mason J.B. Setting and evaluating the energy content of emergency rations. Disasters. 1996;20:248–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7717.1996.tb01037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing Hope Page The Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza. [(accessed on 12 September 2021)]; Available online: https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/ohp-ahmppi.htm.

- 21.Japanese Government Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries Home Page [(accessed on 12 September 2021)]; Available online: https://www.maff.go.jp/j/zyukyu/foodstock/guidebook.html.

- 22.Shrivastava S.R.B., Shrivastava P.S., Ramasamy J. Meeting nutritional requirements of the community in disaster: A guide to policy-makers. Int. J. Health Syst. Disaster Manag. 2014;2:246–248. doi: 10.4103/2347-9019.144414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Inoue T., Nakao A., Kuboyama K., Hashimoto A., Masutani M., Ueda T., Kotani J. Gastrointestinal symptoms and food/nutrition concerns after the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011: Survey of evacuees in a temporary shelter. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2014;29:303–306. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X14000533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hilderbrand K., Boelaert M., Van Damme W., Van der Stuyft P. Food rations for refugees. Lancet. 1998;351:1213–1214. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79169-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nichols E.K., Talley L.E., Birungi B., McClelland A., Madrra E., Chandia A.B., Nivet J., Flores-Ayala R., Serdula M.K. Suspected outbreak of riboflavin deficiency among populations reliant on food assistance: A case study of drought-stricken Karamoja, Uganda, 2009–2010. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaker-Berbari L., Ghattas H., Symon A.G., Anderson A.S. Infant and young child feeding in emergencies: Organizational policies and activities during the refugee crisis in Lebanon. Matern. Child Nutr. 2018;14:e12576. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tanaka R., Okawa M., Ujike R. Predictors of hypertension in survivors of the Great East Japan Earthquake, 2011: A cross-sectional study. Prehosp. Disaster Med. 2015;31:17–26. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X15005440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ohira T., Hosoya M., Yasumura S., Satoh H., Suzuki H., Sakai A., Ohtsuru A., Kawasaki Y., Takahashi A., Ozasa K., et al. Evacuation and risk of hypertension after the Great East Japan Earthquake: The Fukushima Health Management Survey. Hypertension. 2016;68:558–564. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paterson D.L., Wright H., Harris P.N.A. Health risks of flood disasters. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018;67:1450–1454. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe M., Hikichi H., Fujiwara T., Honda Y., Yagi J., Homma H., Mashiko H., Nagao K., Okuyama M., Kwachi I. Disaster-related trauma and blood pressure among young children: A follow-up study after Great East Japan Earthquake. Hypertens. Res. 2019;42:1215–1222. doi: 10.1038/s41440-019-0250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases 2013–2020. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colon-Ramos L., Roess A.A., Robien K., Marghella P.D., Waldman R.J., Merrigan K.A. Foods distributed during federal disaster relief response in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria did not fully meet federal nutrition recommendations. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2019;119:1903–1915. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hassan S., Nguyen M., Buchanan M., Grimshaw A., Adams O.P., Hassell T., Ragster L., Nunez-Smith M. Management of chronic noncommunicable diseases after natural disasters in the Caribbean: A scoping review. Health Aff. 2020;39:2136–2143. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.01119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yoshida H., Sudo N. Development of a teaching material for multidisciplinary practicum of registered dietitian nutritionist training courses and its educational effects to learn nutrition assistance during disaster. Jpn. J. Health Hum. Ecol. 2018;84:158–172. doi: 10.3861/kenko.84.5_158. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Watanabe C., Sudo N., Tsuboyama-Kasaoka N. The current state of knowledge and interest about nutrition assistance in disasters among university students in Registered Dietitian training courses. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 2017;75:80–90. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.75.80. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudo N., Yoshiike N. A Japanese nationwide survey on education regarding nutrition during disasters by public health nutrition and food service management teachers in universities with registered dietitian training programs. Jpn. J. Nutr. Diet. 2012;70:188–196. doi: 10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.70.188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]