Abstract

The phytopathogenic basidiomycete Ustilago maydis requires its host plant, maize, for completion of its sexual cycle. To investigate the molecular events during infection, we used differential display to identify plant-induced U. maydis genes. We describe the U. maydis gene mig1 (for “maize-induced gene”), which is not expressed during yeast-like growth of the fungus, is weakly expressed during filamentous growth in axenic culture, but is extensively upregulated during plant infection. mig1 encodes a small, highly charged protein of unknown function which contains a functional N-terminal secretion sequence and is not essential for pathogenic development. Adjacent to mig1 is a second gene (mdu1) related to mig1, which appears to result from a gene duplication. mig1 gene expression during the infection cycle was assessed by fusing the promoter to eGFP. Expression of mig1 was absent in hyphae growing on the leaf surface but was detected after penetration and remained high during subsequent proliferation of the fungus until teliospore formation. Successive deletions as well as certain internal deletions in the mig1 promoter conferred elevated levels of reporter gene expression during growth in axenic culture, indicative of negative regulation. During fungal growth in planta, sequence elements between positions −148 and −519 in the mig1 promoter were specifically required for high levels of induction, illustrating additional positive control. We discuss the potential applications of mig1 for the identification of inducing compounds and the respective regulatory genes.

The phytopathogen Ustilago maydis belongs to the fungal class Basidiomycetes and causes smut disease in maize (4). All aerial parts of the host plant can be infected. Disease is initially characterized by tissue chlorosis and anthocyanin pigmentation and culminates in the development of plant tumors filled with masses of black teliospores. U. maydis adopts two different morphologies during its life cycle. Haploid sporidia grow yeast-like and can be propagated on artificial media. After fusion of two compatible sporidia, a filamentous dikaryon is generated; this structure is infectious. The dikaryon depends on the plant for further proliferation. Cell fusion, the morphologic switch, and pathogenicity are governed by two unlinked mating-type loci termed a and b (4). The a locus exists in two alleles, a1 and a2, each encoding a pheromone precursor and the receptor recognizing the pheromone of opposite mating type (7, 38). The multiallelic b locus contains two divergently transcribed genes, bE and bW, encoding a pair of homeodomain proteins (11, 21, 35). In pairwise combinations, bE and bW proteins from different alleles can dimerize and trigger subsequent pathogenic development (19).

In nature, compatible haploid sporidia fuse on the leaf surface and the filamentous dikaryon differentiates in an appressorium-like structure that penetrates the host cell wall (36). Penetration through stomata has also been reported (5). From the infection site, the fungus spreads rapidly and grows primarily intracellularly through epidermal cells. During this stage the fungus is surrounded by the host cell plasma membrane and is thus not in direct contact with the cytoplasm of the plant (37). Later the fungus grows mostly intercellularly around cells of the vascular bundle (37). The intercellularly growing hyphae are frequently branched, and some branches protrude into plant cells, where they can swell and adopt finger-like projections (5, 37). Small bumps on leaves or leaf blades indicate the onset of tumor development 4 to 6 days after infection. Within tumor tissue, hyphae proliferate vigorously in the intercellular space and within plant cells. Finally, sporogenic hyphae are formed, nuclei fuse, and the hyphae fragment and differentiate to become diploid teliospores (5, 37). The molecular triggers for these developmental processes are unknown. Because these events require the host plant, it has been hypothesized that specific plant compounds are perceived by the fungus and result in the activation or repression of specific sets of genes. Identification of such genes is likely to provide insight into the molecular mechanisms that govern pathogenic development. In this report, we describe the identification and characterization of the U. maydis gene mig1, whose expression is strongly stimulated after fungal penetration of maize tissue. We show that expression of mig1 is subject to negative as well as positive regulation and discuss how mig1 can be exploited for the identification of signaling components derived from the maize plant.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

Escherichia coli K-12 strain DH5α (Bethesda Research Laboratories) was used as host for plasmid amplification. Haploid U. maydis FB1 (a1b1) and FB2 (a2b2) and the diploid strain FBD11 (a1a2b1b2) have been described (3). CL13 (a1bE1bW2) is a solopathogenic haploid strain (8). Cells were grown at 28°C in YEPS (42), potato dextrose medium (PD) (Difco), complete medium (CM) (18), or minimal medium (18). To test for mating, strains were cospotted on charcoal-containing PD plates and incubated at room temperature for 48 h. Plant infections were done as described previously (11, 32) with the varieties Early Golden Bantam (Olds Seed, Madison) or Gaspe Flint (kindly provided by B. Burr, Brookhaven National Laboratory).

To investigate the influence of nitrogen and carbon sources on mig1 expression, strains FB1Δmig1::GFP2 and FB2Δmig1::GFP2 were cultivated in CM and starvation medium consisting only of the Holliday vitamin and salt mixtures (18) with either 1 mM glutamate or 1 mM proline as the nitrogen source and either glucose (1%) or arabinose (1%) as the carbon source. To investigate the influence of plant extracts on mig1 gene expression, the leaves from 8-day-old maize seedlings were frozen in liquid nitrogen and reduced to powder by grinding. CM limited to the Holliday vitamin and salt mixtures in the presence or absence of 1% sucrose was supplemented with this plant material to a final concentration of 4%. To assay expression in the dikaryotic stage, strains FB1Δmig1::GFP2 and FB2Δmig1::GFP2 were cospotted on solid media of the same composition to which 1% charcoal had been added. Expression was also monitored in cultures that had been placed on water agar. The influence of cyclic AMP (cAMP) on mig1 induction was assessed in PD cultures supplemented with 6 mM cAMP (23). Expression was monitored by fluorescence microscopy between 12 and 48 h after transfer to the respective medium. To assess mig1 expression in strain FBD11, this strain was cultivated on solid charcoal-containing CM, solid charcoal-containing minimal medium, solid charcoal-containing minimal medium with 2 mM glutamate as the nitrogen source and either glucose (1%) or arabinose (1%) as carbon source, and solid charcoal-containing minimal medium containing 4% plant extract (see above). For Northern analysis, RNA was isolated 48 h after transfer to the respective medium.

DNA and RNA procedures.

U. maydis chromosomal DNA was prepared by the method of Hoffman and Winston (17). Maize chromosomal DNA was isolated with the DNEasy plant minikit (Qiagen). A fragment of the 26S rRNA encoding gene was amplified from genomic maize DNA with the primers 26S1 (5′-GAGTAGAGGTCGCGAGAGAGCAG-3′) and 26S2 (5′-GATTGGTCGTTGTGTGTCACC-3′). Transformation of U. maydis followed the protocol of Schulz et al. (35). RNA was isolated from strains grown in liquid PD or on solid CM charcoal plates by the methods of Timberlake (41) and Schmitt et al. (33), respectively. Infected plant tissue was harvested at the time points indicated and frozen in liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted by the method of Schmitt et al. (33). Radioactive labeling of DNA was performed with the megaprime DNA labeling kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Detection and quantification of the signals was done with a STORM PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics) and ImageQuant software. Nucleotide sequences were determined by automated sequencing with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer (Perkin Elmer). Both DNA strands were sequenced. Nucleotide sequences were compared by using Gapped BLAST and PSI-Blast (1). Potential promoter binding sites were analyzed with the use of the TRANSFAC database (15). All PCR-generated plasmid portions and cDNA fragments were sequenced. All other DNA manipulations followed standard procedures as described by Sambrook et al. (31).

Differential display.

Total RNA was isolated from tumor tissue of maize seedlings 6 days after infection with a mixture of FB1 and FB2, and mock-infected plants were injected with water. RNA samples were treated with DNase. The reaction mixtures contained total RNA (50 μg), 10 U of RNase-free DNaseI (Boehringer), 10 U of human placental RNase inhibitor (Boehringer), 2.5 mM dithiothreitol, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2. The reaction products were incubated for 30 min at 37°C and were subsequently extracted twice with phenol-chloroform followed by ethanol precipitation. Differential display was performed essentially as described previously (6, 27). For reverse transcription, two individual RNA preparations from infected and control plants were used in a 20-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μg of total RNA, 1 μM T11AG and T11AC primer mixture, 40 μM each of the four nucleoside triphosphates (NTPs), 3 mM MgCl2, 20 U of human placental RNase inhibitor (Boehringer), and 200 U of reverse transcriptase (SuperScript II RNase H−; GIBCO BRL). Prior to the addition of reverse transcriptase, the mixture was incubated at 65°C for 5 min and then at 37°C for 10 min. The reaction was carried out at 40°C for 1 h and terminated by heating at 95°C for 5 min.

For PCR amplification, 2 μl of cDNA solution from the first step and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) were incubated in 20-μl reaction mixtures in buffer containing 16 μM NTPs, 0.5 μM [α-35S]dATP, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 μM oligo(dT) primer mixture used for reverse transcription, and 1 μM 10-mer primer with a defined but arbitrary sequence (5′-((C/G)TCACGGACG-3′). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 30 s, 40°C for 2 min, and 72°C for 30 s for 40 cycles and then a 5-min elongation at 72°C. PCR amplifications were carried out in duplicate. The amplified cDNAs were separated on a 6% DNA sequencing gel, differential bands were excised, and DNA was eluted and reamplified as described for the first PCR in the presence of 25 μM NTPs. Amplified cDNA fragments were cloned into the pCR 2.1-TOPO vector (Invitrogen) as specified by the manufacturer. To identify colonies containing cDNA inserts of differentially expressed genes, Southern blots were prepared in duplicate from EcoRI-digested plasmid DNA and hybridized to 10 μl of the original 35S-labeled PCR products from either control samples or infected samples. Hybridization was done overnight at 58°C and the membranes were washed twice in 2× SSPE (1× SSPE is 0.18 M NaCl, 10 mM NaH2PO4, and 1 mM EDTA [pH 7.7])–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) and once in 1×SSPE–0.1% SDS at 58°C. Clones whose differential expression was confirmed were subsequently used for Northern analysis.

Plasmids and plasmid constructions.

For subcloning and sequencing, plasmids pUC18, pUC19, and pTZ19R (Pharmacia) were used. The U. maydis cosmid library has been described previously (8). As selectable markers for U. maydis, a hygromycin resistance cassette was isolated as a 2,923-bp BamHI-EcoRV fragment from the U. maydis vector pSP-hyg (14) and a carboxin resistance cassette was isolated as a 1,968-bp PvuII/StuI fragment from pSLCbx− (A. Brachmann and R. Kahmann, unpublished data). Plasmid p123 (C. Aichinger and R. Kahmann, unpublished data) contains the eGFP gene (Clontech) fused to the otef promoter (39). The eGFP gene and the otef promoter were excised as a 1,030-bp NcoI-EcoRV fragment and as a 938-bp HindIII-NcoI fragment from p123, respectively. Plasmid pMIGB contains the 3,434-bp genomic BamHI fragment encompassing the mig1 gene. pMIGBΔNE is a deletion derivative of pMIGB which was generated by deleting a 1,045-bp EcoRI-NcoI fragment and religating after refilling protruding ends with Klenow polymerase. Plasmid pMIGBS contains the 4,744-bp genomic BamHI-SpeI fragment encompassing the mig1 and mdu1 genes. To construct the deletion derivative pΔmig, the 2,019-bp genomic MscI-PmlI fragment encompassing mig1 and mdul was replaced in pMIGBS with the 2.9-kb hygromycin B cassette as a BamHI-EcoRV fragment. To replace the resident mig locus with the Δmig allele, a 4.6-kb SnaBI-SphI fragment was isolated from pΔmig and transformed into U. maydis FB1 and FB2. For Southern analysis, genomic DNA of transformants was digested with AlwNI and SspI and probed with fragments of mig1 and mdu1.

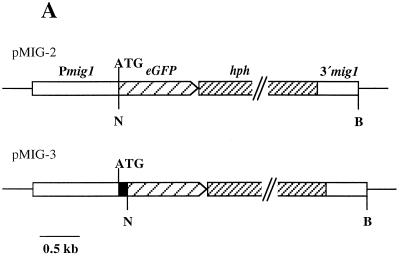

For construction of the mig1::eGFP reporter plasmids pMIG-2 and pMIG-3, pMIGBΔNE was amplified with a forward primer containing an EcoRV restriction site (TIGD, 5′-GCATGATATCCGTGAATCGCCATCTACC-3′) and two different reverse primers containing an NcoI restriction site (TIGU1 for pMIG-2, 5′-AACGCCATGGTGATCTGGAGGAAGAGAATGG-3′; TIGU2 for pMIG-3, 5′-CGATCCATGGTGGGCGCTGGCCAGGCATGG-3′). PCR mixtures contained 15 ng of plasmid DNA as template, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 3 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dNTPs, 30 pmol of each primer, and 2 U of DyNAzyme EXT DNA polymerase (Finnzymes OY). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 74°C for 3.5 min for 30 cycles and then a 10-min elongation at 74°C. PCR products were cleaved with EcoRV and NcoI and ligated to the eGFP gene isolated as an NcoI-EcoRV fragment to yield pMIG-2V and pMIG-3V, respectively. Plasmids pMIG-2 and pMIG-3 were generated from these plasmids by cloning the hygromycin B cassette as an end-filled BamHI-EcoRV fragment into the EcoRV site. In pMIG-2, the mig1 promoter is fused to eGFP at translational position 1; in pMIG-3, fusion is at the downstream ATG at position 88 in mig1. To replace the resident mig1 gene with the eGFP-reporter alleles, a 4.9-kb AvrII-SphI fragment was isolated from pMIG-2 and pMIG-3 and transformed into U. maydis FB1 and FB2. For Southern analysis, genomic DNA was cleaved with AlwNI and SspI and probed with either the NcoI-KpnI or the KpnI-NruI fragment of mig1.

In pMIG-2otef and pMIG-3otef, the otef promoter was ligated as a HindIII-NcoI fragment into the AvrII and NcoI sites of pMIG-2 and the AvrII and MfeI sites of pMIG-3, respectively, after refilling of the protruding ends. For integrative transformation, both plasmids were linearized with SspI and ectopically integrated in the genome of U. maydis FB2. For Southern analysis to confirm ectopic integration of the plasmids, genomic DNA was digested with BamHI and SspI. A NcoI-KpnI mig1 promoter fragment was used as a probe.

For the construction of the pNN plasmid containing the 2,075-bp promoter fragment of the mig1 gene, the NcoI site of pMIGB (position −1124 in the mig1 promoter) was eliminated by cleavage and religation after refilling of protruding ends. pEN, pES, and pEM deletion derivatives were constructed by excising the respective EcoRI-NcoI, EcoRI-SnaBI, and EcoRI-MfeI fragments from pMIGB and religating the refilled ends. The resulting plasmids were used as PCR templates with primers TIGU1 and TIGD under the conditions described above. The eGFP gene was cloned as an NcoI-EcoRV fragment into the respective sites of the cleaved and purified PCR products, and the cbx cassette was ligated as PvuII-StuI fragment into the EcoRV site. pENΔM148 was constructed by replacing the MfeI-NcoI fragment in pMIG-2V with the respective 5′-shortened fragment generated by PCR with a forward primer containing a MfeI restriction site (5′-ATTCCAATTGGCAACGAGGAGACGCTC-3′) and a reverse primer containing a NcoI restriction site (5′-AACGCCATGGTGATCTGGAGGAAGAGAATGG-3′) prior to the insertion of the cbx cassette. In pS148 and pSA, the SspI-MfeI fragment of pENΔM148 and the SspI-AvrII fragment of pEN, respectively, were eliminated by cleavage and religation of refilled ends. In pENΔAM and pENΔA148, the AvrII-MfeI fragments of pEN and pENΔM148, respectively, were eliminated by cleavage and religation of refilled ends. In pENΔAA and pENΔM1, the AgeI-AvrII and the MfeI-NcoI fragment, respectively, of pEN were eliminated by cleavage and religation of refilled ends. Prior to transformation in strain CL13, plasmids pNN, pEN, pES, pSA, pEM, pS148, pENΔM148, pENΔAM, pENΔA148, pENΔAA, and pENΔM1 were linearized with XhoI, which cleaves within the cbx gene (20). Transformants were selected on carboxin-containing medium (2 μg/ml). Homologous integration events in the cbx locus were verified by Southern analysis after cleaving genomic DNA with XhoI and SspI and probing with the AgeI-NdeI or PvuII-StuI fragments of the cbx gene.

Isolation of mig1 and mdu1 cDNA clones.

Tumor RNA as prepared for differential-display analysis was reverse transcribed with a T11AG primer (above) and used as a template for the amplification of a mig1 cDNA fragment, extending from −94 to 759, with the forward primer 5TIGA (5′-AATCAAGCCACATCCTTGACG-3′) and the reverse primer TIG3BR (5′-GAAGCATCTTTGATCAATGC-3′). To amplify an mdu1 cDNA, total RNA (1 μg) from U. maydis FBD11 grown on CM charcoal was digested with 20 U of RNase-free DNAse (Boehringer). RNA was reverse transcribed with a degenerate T16(A/G/C)N primer under the conditions described above and was used as template for the amplification of an mdu1 cDNA clone, extending from 1479 to 2001, by using the forward primer TIGE2B (5′-GCCATCATTTCAGTACTCACC-3′) and the reverse primer TIGT (5′-GTGAATACAGGCAGTCTTTGC-3′). PCR mixtures contained 2 μl of the reverse-transcribed RNA, primers (each 15 μM), 0.1 mM NTPs, 1.5 mM Mg2Cl, and 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Qiagen). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 40 s for 38 cycles and then a 10-min elongation at 72°C. The following control reactions were included to verify amplification of an mdu1 cDNA fragment: a mig1 cDNA fragment could be amplified from the FBD11 cDNA preparation with primers CDU1H (5′-ATGACGCTCTTTCGGTACCCAGC-3′) and TIG3BR, whereas a genomic PCR fragment was amplified exclusively from genomic DNA of FB1. With the use of the forward primer TIGB1 (5′-CAATCGTATCATTCGTGTTCG-3′) and TIGT, an mdu1 PCR product could be amplified from genomic FB1 DNA but not from the FBD11 cDNA preparation.

Immunodetection.

U. maydis strains were grown in PD to an optical density at 600 nm of 1.5. Cell-free supernatants were collected after two centrifugation cycles for 10 min at 3,000 rpm and were lyophilized. The cell pellets were washed with water and stored frozen at −80°C. After resuspension in Laemmli buffer (24) and boiling for 5 min, proteins of cell pellets and supernatants corresponding to 40 and 125 μl of cell culture, respectively, were subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Recombinant green fluorescence protein (GFP) (40 ng; Boehringer) was run as control. The proteins were blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (Millipore). Binding of the primary antibody (monoclonal GFP immunoglobulin G mouse [kindly provided by M. Maniak, MPI Martinsried]) was enzymatically detected by using rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase HRP conjugate (Promega). Immunostaining was performed with the ECL+ chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Microscopy.

Infected leaf tissue was excised from regions adjacent to chlorotic areas or from tumor tissue with a razor blade. Samples were observed with differential interference contrast optics or under fluorescence microscopy by using a Zeiss Axiophot as described previously (39). Photographs were taken on Kodak GOLD 800 film. Color figures were prepared from digitized images of color prints by using Adobe (Mountain View, Calif.) Photo-Shop, with only those processing functions that could be applied equally to all pixels of the image being used.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of the mig1 locus has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AF195613.

RESULTS

Isolation of the mig1 gene.

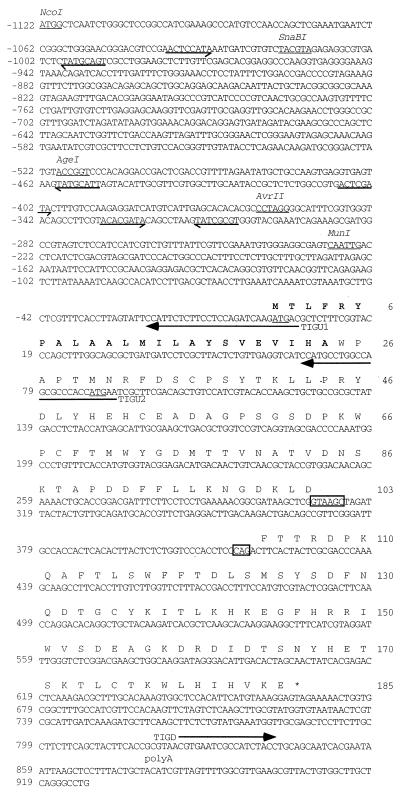

We used the method of differential display (27) to identify U. maydis genes which are specifically expressed during the interaction with maize. RNA extracted from leaf tumor tissue 6 days postinfection was compared to corresponding RNA isolated from mock-infected leaf tissue. From a screen in which 42 different primer combinations were tested, 23 differential fragments were cloned and verified for differential expression by Northern analysis with the same RNA preparations as used for differential display. We identified eight maize genes that were upregulated between 3- and 60-fold in tumor tissue compared to noninfected control tissue and 2 maize genes that were downregulated upon infection. Furthermore, we identified mig1 as a fungal gene that is strongly upregulated in tumor tissue. Among three additional fungal genes strongly expressed during the tumor stage, one displayed similar regulation to mig1 (data not shown). The original amplified DNA fragment of mig1 comprised the 3′ part of the gene including the poly(A) site. The 3′ untranslated region contains a motif (AATAAT) that matches the poly(A) consensus sequence (12) and precedes the poly(A) site (Fig. 1). The amplified fragment was used to screen a cosmid library of U. maydis, which led to the identification of a 4.7-kb genomic BamHI-SpeI fragment encompassing mig1. The sequence of the mig1 gene including 5′ and 3′ regions was determined (Fig. 1). A cDNA fragment was amplified by PCR from reverse-transcribed tumor RNA. An alignment with the corresponding genomic sequence revealed the existence of an intron of 109 bp (Fig. 1). The cDNA allowed us to define an open reading frame (ORF) encoding a protein of 185 amino acids with a calculated molecular mass of 21.4 kDa. The N-terminal 24 amino acids represent a hydrophobic stretch predicted to function as a secretion signal by the program PSORT (28). The mig1 ORF encodes a hydrophilic protein highly enriched in aspartic acid and lysine residues and contains one potential N-glycosylation site at Asn-80 (Fig. 1). The Mig1 protein sequence showed no significant homologies to known proteins in the BLAST database (1).

FIG. 1.

Nucleotide sequence and derived amino acid sequence of mig1. Shown is the DNA sequence of the 2,059-bp genomic NcoI-AlwNI region containing the mig1 gene. Primers used for generating mig1::eGFP fusions are indicated (arrows). Intron/exon borders are boxed, and the poly(A) site at position 878 is indicated. The two ATGs used as translation starts in eGFP-reporter strains are underlined. The amino acid sequence of the mig1 ORF is given in capital letters. The predicted secretion sequence is shown in boldface type. The stop codon of mig1 is indicated by an asterisk. Repeated sequence elements in the mig1 promoter are denoted by arrows indicating their orientation. Restriction sites used for promoter deletions are underlined.

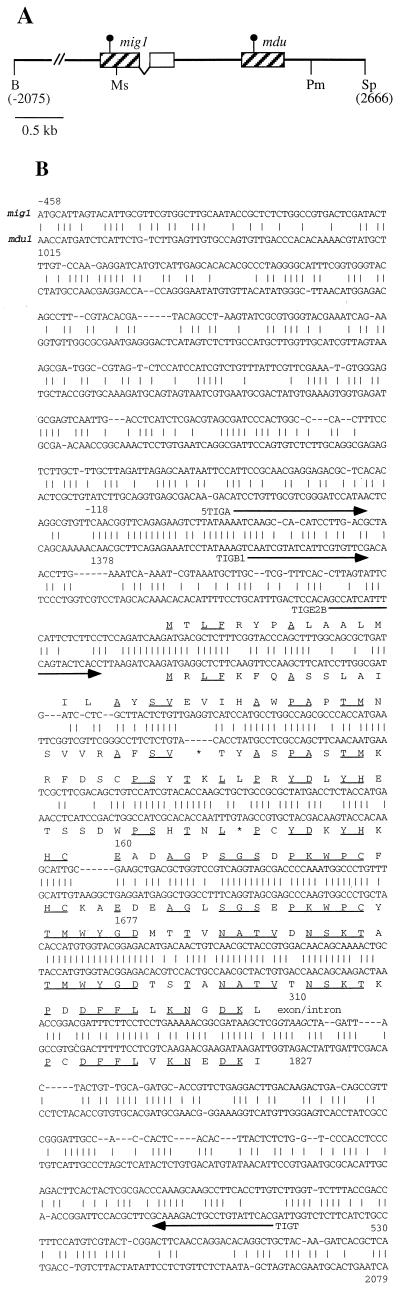

Gene duplication in the mig1 locus.

Closer inspection of the DNA sequence downstream of mig1 revealed a region from nucleotides 1378 to 1827 with 67% sequence identity to mig1. We have termed this putative mig1 homolog mdu1 (for “mig duplicated”). With respect to the mig1 gene, the similarity extends from position −118 to 310 (Fig. 2). Extended regions of identity are at the immediate 5′ end of the coding sequence from positions −8 to 11 and from positions 160 to 310 in mig1, with 79% identity to the region from positions 1677 to 1827 in mdu1. Sequence identities break abruptly at the mig1 intron/exon border. With respect to mig1, mdu1 contains a 6-bp insertion (position 1549), a 5-bp deletion (position 1573), and an amber mutation (position 1638) (Fig. 2B). Consequently, the hypothetical product of mdu1 comprises only 53 amino acids with no significant similarity to Mig1 or to protein sequences in the database. Since we were unable to isolate cDNA clones corresponding to mdu1, we followed a reverse transcription-PCR approach. The region from positions 1479 to 2001 could be amplified by PCR from reverse-transcribed RNA of strain FBD11 grown on charcoal medium whereas no PCR product was obtained with a more 5′-positioned primer hybridizing between 1405 and 1425. Subsequent sequence analysis of the cloned PCR fragment revealed complete identity to the genomic sequence. This illustrates that the mdu1 transcript is not spliced, which could have removed the stop codon. Therefore, we consider mdu1 to be a pseudogene.

FIG. 2.

Regions of similarity between mig1 and mdu1. (A) Physical map of the mig1 genomic region. Sequence similarities are indicated by hatched boxes, and the second exon of mig1 is depicted by the open box. The presumed translation initiation codons are marked by dots. The mig1 intron is represented by two diagonal lines. Cleavage sites for BamHI (B), SpeI (Sp), MscI (Ms), and PmlI (Pm) are indicated. (B) Nucleotide sequence alignment of the duplicated regions. Numbers indicate the position and orientation of aligned sequences. Identical residues are indicated by vertical lines, gaps introduced to maximize alignment are shown as dashes. The intron/exon border of mig1 is indicated (italics). The amino acid coding potential of mig1 and mdu1 is given in capital letters. Identical amino acids are underlined. The stop codon and frameshift mutation in mdu1 are shown by asterisks. Primers used for amplification of cDNA fragments are indicated (arrows).

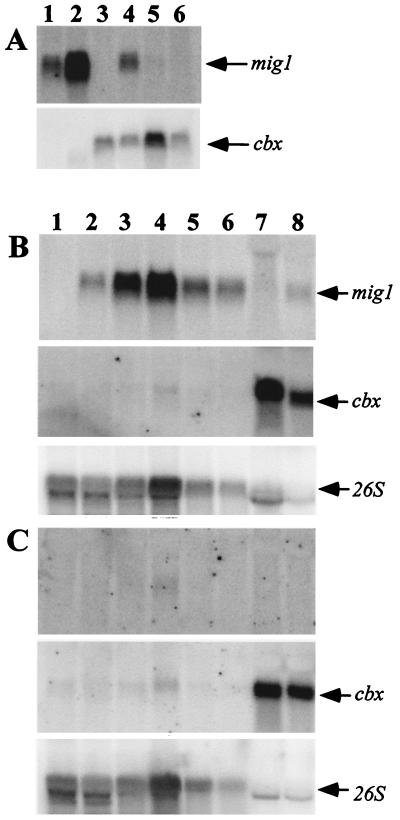

Expression analysis of mig1.

As judged by Northern analysis, mig1 mRNA was not detectable in the haploid strain FB1 (a1b1) (Fig. 3A, lane 3) and gave a weak signal in the diploid strain FBD11 (a1a2b1b2) (lane 4). In the latter strain, the pheromone-signaling cascade is turned on through binding of the pheromone to its cognate receptor. This cascade activates the transcriptional regulator Prf1 (13, 14), which in turn leads to the transcriptional activation of the b genes. Because the diploid strain FBD11 carries two alleles of the b locus, an active bE/bW heterodimer is formed and enables subsequent pathogenic development (19). To discriminate whether mig1 expression results from an active pheromone cascade or the b heterodimer, mig1 expression levels were assayed in the diploid strain FBD11#007 (a1a2b1b1), in which pheromone signaling is activated but no b heterodimer is produced (Fig. 3A, lane 6), and the haploid strain HA103, in which transcription of the bE1 and bW2 genes is driven by constitutive promoters without an activated pheromone cascade (13) (lane 5). Neither situation led to an induction of the mig1 gene (Fig. 3A). In contrast, mig1 expression was dramatically induced during growth in planta (Fig. 3A and B). Expression of mig1 could be detected 2 days postinoculation by using the combination of haploid strains FB1 and FB2 and increased steadily until 6 days after inoculation, culminating in an approximately 1,000-fold induction compared to the expression level in the diploid strain FBD11 grown on charcoal CM (Fig. 3B). This huge difference in expression levels is best documented when mig1 expression signals are compared with those from the constitutively expressed fungal cbx gene, which reflects the amounts of fungal RNA. Because of the underrepresentation of fungal RNA in total RNA isolated from tumor tissue, hybridization with the maize 26S RNA gene served to determine the total RNA amounts loaded (Fig. 3B and C). In contrast to mig1, the expression of mdu1 was not detectable during plant infection or on charcoal CM as judged by Northern analysis (Fig. 3C).

FIG. 3.

Analysis of temporal expression of mig1 and mdu1 in U. maydis during infection and axenic growth. (A) The Northern blot was probed with the 32P-labeled mig1 cDNA fragment (see Materials and Methods). RNA prepared from infected tissue 2 and 4 days postinoculation is shown in lanes 1 and 2; RNA from strains FB1, FBD11, HA103, and FBD11#007 grown on CM charcoal for 2 days is shown in lanes 3 to 6. Strains FBD11 and HA103 undergo filamentous growth on charcoal medium. About 10 μg RNA was loaded per lane. (B) The Northern blot was probed with the 32P-labeled NruI-PstI fragment of the mig1 coding region. Lanes 1 to 6 contain total RNA from maize seedlings immediately after inoculation with a mixture of strains FB1 and FB2 (lane 1) and from infected tissue 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10 days (lanes 2 to 6) postinoculation. In lanes 1 through 4, about 10 μg of RNA was loaded; in lanes 5 and 6, 5 μg of RNA was used. Lanes 7 and 8 contained 15 and 7 μg of RNA from strains FB1 and FBD11, respectively, grown on CM charcoal for 2 days. (C) The Northern blot was probed with the 32P-labeled BamHI-FspI fragment containing mdu1. The same RNA samples were loaded as described for panel B, except that 10 μg of RNA was loaded in each of lanes 7 and 8. Filters shown in all panels were subsequently hybridized with a probe from the cbx locus, and filters shown in panels B and C were additionally hybridized with the 26S rRNA-encoding maize gene (lower panels). The constitutive expressions of the cbx and the 26S genes reflect the amounts of U. maydis and maize RNA, respectively, that were loaded.

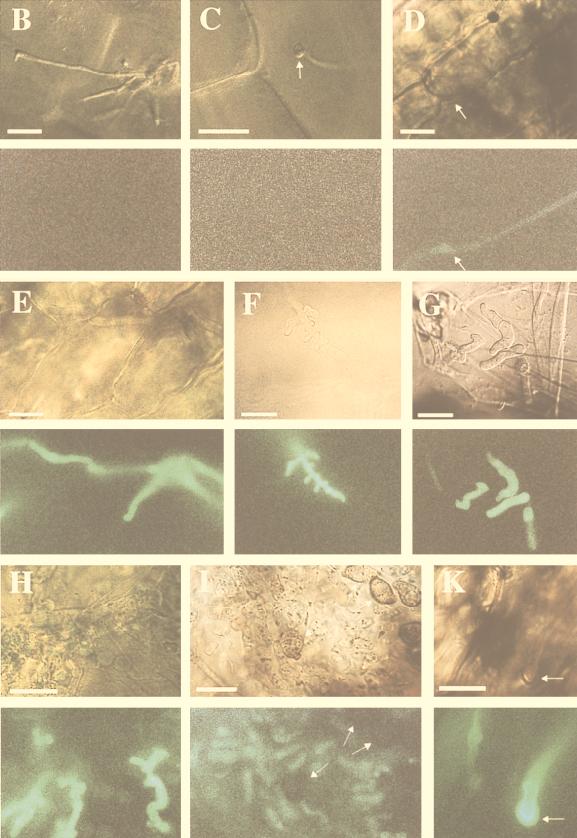

Due to a limited amount of fungal biomass during the early infection phase, Northern analysis does not reflect the detailed temporal expression pattern; in particular, it does not allow us to determine the precise stage at which mig1 gene expression is initiated. To achieve this, we replaced the mig1 ORF with the gene encoding GFP (eGFP), which can be used as reporter of gene activity (39) (Fig. 4A). To assess whether the 5′ sequence of mig1 encodes a secretion signal, we generated, in addition to the ATG at position 1, an eGFP fusion at the in-frame ATG at position 88 (Fig. 1 and 4A). These plasmids, termed pMIG-2 and pMIG-3, respectively, were transformed into the haploid strains FB1 and FB2. Transformants where the resident mig1 gene was replaced by eGFP and the hygromycin resistance cassette were identified by Southern analysis (data not shown). The resulting strains, FB1Δmig1::eGFP2, FB2Δmig1::eGFP2, FB1Δmig1::eGFP3, and FB2Δmig1::eGFP3, showed normal growth on PD plates and could mate in the respective compatible combinations (data not shown). This indicates that mig1 is a nonessential gene not required for mating and subsequent filamentous growth of the dikaryon. Neither the haploid strains nor the filamentous dikaryon carrying the mig1 promoter eGFP fusions displayed GFP fluorescence after excitation (data not shown). After the compatible strains FB1Δmig1::eGFP2 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP2 were coinjected into young maize seedlings, tumor development was indistinguishable from that due to a cross of respective wild-type strains. GFP activity could not be detected in the various stages prior to penetration, e.g., in filaments and appressoria (Fig. 4B and C). After penetration, intracellularly growing hyphae displayed weak GFP activity (Fig. 4D). Fluorescence was strongly elevated within the next 2 days of hyphal development and was also seen in multiply-branched structures protruding into plant cells (Fig. 4E and F). GFP activity remained high during subsequent stages of development and was still present in hyphal fragments as well as in branched short sporogenic hyphae within tumor tissue between 8 and 11 days after infection (Fig. 4G and H). Fluorescence was no longer detectable in pigmented teliospores (Fig. 4I). The absence of fluorescence in teliospores is likely to reflect downregulation of the mig1 promoter at this developmental stage, because constitutive egfp expression results in strongly fluorescing teliospores (39).

FIG. 4.

mig1::eGFP expression during maize infection. (A) Physical map of reporter constructs pMIG-2 and pMIG-3. Plasmids (thin line) contain eGFP fused to the mig1 promoter (Pmig1) at two different in-frame-positioned ATGs, the hygromycin resistance cassette (hph), and the 3′ untranslated sequences of mig1. The ATG in boldface type indicates the ATG at position 1 of mig1. The remaining coding sequence of mig1 is indicated by a black bar. N, NcoI; B, BamHI. (B to K) Temporal and spatial GFP expression of Δmig1::eGFP strains. Maize seedlings were infected with mixtures of FB1Δmig1::eGFP2 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP2 (B to I) as well as FB1Δmig1::eGFP3 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP3 (K). Maize tissue samples were assayed by differential interference contrast light microscopy (upper panels) and epifluorescence (lower panels). Bars, 10 μm. (B) Extended hyphae growing on the leaf surface 40 h postinfection. (C) Hyphae growing on a leaf surface 40 h postinfection; the hyphal tip is swollen to an appressorium-like structure (arrow). (D and E) Intracellular hyphae at 50 and 72 h postinfection, respectively (arrow in panel D). (F) Multiply branched hyphae inside a host cell 4 days postinfection. (G) Hyphal fragments in a leaf tumor section 8 days postinfection. (H) Leaf tissue excised adjacent to the leaf tumor 11 days postinfection, showing swollen, sporogenic hyphae. (I) Leaf tumor section 11 days postinfection, revealing fragmented hyphae and pigmented teliospores (arrows). (K) Characteristic accumulation of GFP activity at the hyphal tip (arrow) 72 h postinfection.

In infections with the compatible strains FB1Δmig1::eGFP3 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP3 fluorescence followed the same time course as observed with strains FB1Δmig1::eGFP2 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP2 (data not shown). However, in this cross, fluorescence appeared most intense at hyphal tips, which may indicate that the respective fusion protein is secreted (Fig. 4K).

Strains FB1Δmig1::eGFP2 and FB2Δmig1::eGFP2 were also used to monitor mig1 gene expression after growth in different media to assess whether induction can be achieved. We tested nitrogen starvation, alternative carbon sources like arabinose instead of glucose, prolonged incubation on water agar, the addition of 6 mM cAMP to liquid PD medium, as well as the addition of a maize seedling extract to solid charcoal medium. However, mig1 gene expression could not be detected under these conditions (data not shown). To analyze whether heterozygosity at the a and b loci is a prerequisite for environmentally induced mig1 expression, the levels of mig1 mRNA were determined in strains FB1 and FBD11 grown on solid charcoal minimal medium starved for nitrate and glucose either alone or in combination, as well as in the presence of leaf homogenates. On these media, strain FBD11 was still able to undergo filamentous growth but mig1 expression was reduced compared to that on solid charcoal CM and, as expected, was not detectable in strain FB1 (data not shown).

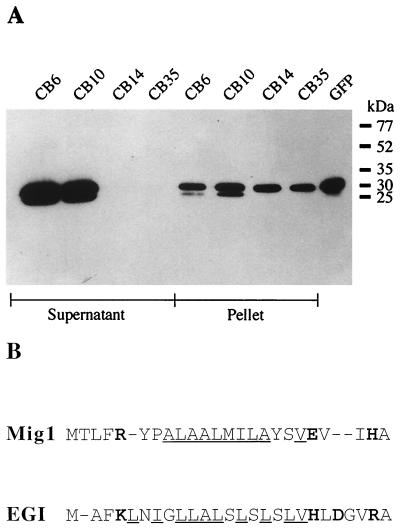

The Mig1 protein can be secreted.

To test whether the N-terminal region of Mig1 represents a functional secretion sequence, the constitutive strong otef promoter was inserted into pMIG-2 and pMIG-3 so that it directs the synthesis of eGFP and the respective eGFP fusion proteins. This should allow the investigation of eGFP secretion in cultures of corresponding transformants. The resulting plasmids pMIG-2otef and pMIG-3otef were introduced into the haploid U. maydis strain FB2, and cultures of transformants harboring single-copy ectopic integrations as assessed by Southern analysis (data not shown) were analyzed microscopically for fluorescence. Of the four transformants selected (strains CB35 and CB14 carrying pMIG-2otef and strains CB6 and CB10 carrying pMIG-3otef), CB6, CB10, and CB35 showed comparable fluorescence while CB14 expressed significantly higher eGFP levels, presumably due to position effects. Supernatants from these four strains and cell extracts were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with an anti-GFP monoclonal antibody. In supernatants of strains CB6 and CB10 expressing eGFP fused to the 5′ signal sequence of mig1, immunoreactive material could be detected, whereas supernatants of CB14 and CB35 did not react with the antibody (Fig. 5A). Signals of comparable intensities were visible in cell extracts of all transformants (Fig. 5A). This indicates that Mig1 can be efficiently secreted due to the presence of an N-terminal signal sequence. This sequence exhibits similarities to the N-terminal 26 amino acids of EGI, an endoglucanase from U. maydis which was shown to be secreted (32) (Fig. 5B) (see Discussion).

FIG. 5.

Immunodetection of GFP in culture supernatants of mig1::eGFP reporter strains and characterization of the Mig1 secretion sequence. (A) U. maydis CB6, CB10, CB14, and CB35 were grown in PD. Proteins from culture supernatants (0.5 μg was loaded), whole cells (see Materials and Methods), and purified recombinant GFP (40 ng) were separated by SDS-PAGE (10% polyacrylamide) and immunostained as described in Materials and Methods. Numbers on the right indicate the positions of molecular mass standards in kilodaltons. The amounts of released proteins cannot be compared directly since no internal protein standard was included as a control for cell lysis. (B) Alignment of the N-terminal amino acid sequences of Mig1 and EGI. Hydrophobic amino acids in the central region are underlined, and charged amino acids are in boldface type. Gaps have been inserted to maximize the number of similarities.

Pathogenic development of mig1-null mutants.

Although in the Δmig1::eGFP reporter strains the entire mig1 ORF was replaced by eGFP, fungal development in planta and pathogenicity were not compromised, indicating that mig1 is not essential for pathogenicity. To address the question of functional gene redundancy between mig1 and mdu1, the region between the MscI and PmlI sites of the mig locus (Fig. 2A) was deleted in U. maydis FB1 and FB2. This deletion eliminates all mig1 and mdu1 coding sequences except those encoding the N-terminal secretion signal of Mig1. Southern analysis with U. maydis DNA isolated from strains lacking both genes revealed no additional mig1-related genes when the genes were hybridized under standard conditions, i.e., conditions which allowed cross-hybridization to mdu1 (data not shown). To analyze whether deletion of the mig locus affected the mating reaction, strains FB1Δmig and FB2Δmig were cospotted onto PD charcoal plates. Formation of dikaryotic filaments was comparable to that produced in respective wild-type strains (data not shown). To determine whether the double mutants were compromised in pathogenicity, corn plants were inoculated with the mixture of FB1Δmig and FB2Δmig by the standard injection method. Tumors arose with comparable frequencies in plants infected with either a mixture of FB1 and FB2 (54 of 80 inoculated plants) or the corresponding deletion strains FB1Δmig and FB2Δmig (44 of 88 inoculated plants). Pathogenicity tests were repeated by spotting cultures in the spiral leaf whorls of 2-week-old maize seedlings of the variety Gaspe Flint, an infection method which does not rely on mechanical wounding. Tumors arose with similar frequencies in mixtures of compatible wild-type strains (37 tumors from 52 inoculated plants) and Δmig mutant strains (45 tumors from 63 inoculated plants), excluding the possibility that the mig locus is required during penetration.

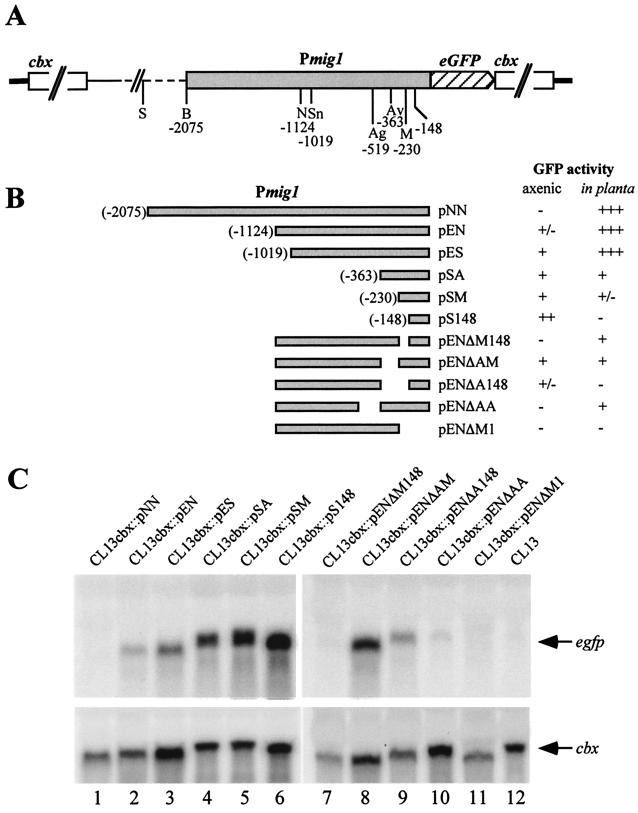

Regulation of mig1.

To elucidate the regulatory mechanism by which the mig1 expression pattern is established, we have analyzed the promoter of the mig1 gene. To this end, eGFP was fused to the ATG codon at position 1 of mig1 (Fig. 1), including promoter fragments differing in length. The resulting integrative plasmids pNN, pEN, pES, pSA, pEM, and pS148 contained promoter fragments ending at positions −2075, −1124, −1019, −363, −230, and −148, respectively (Fig. 6A). In addition, plasmids harboring internal promoter deletions were created (Fig. 6B). All of these plasmids contained the cbx gene as resistance marker (20). To obtain single-copy transformants where the plasmid is inserted in the same genomic context, plasmids were linearized within the cbx gene and transformed into the haploid, solopathogenic strain CL13 (8). This strain was chosen because single-copy transformants had to be generated in only one genetic background for an assessment of eGFP activity both during axenic growth and during infection. Strains CL13cbx::pNN, CL13cbx::pEN, CL13cbx::pES, CL13cbx::pSA, CL13cbx::pSM, CL13cbx::pS148, CL13cbx::pENΔM148, CL13cbx::pENΔAM, CL13cbx::pENΔA148, CL13cbx::pENΔAA, and CL13cbx::pENΔM1 (Fig. 6B) were identified by Southern analysis as containing single homologous recombination events within the cbx locus (data not shown). First, we assessed GFP activities in the individual transformants cultivated in PD. Unexpectedly, fluorescence increased with successive deletions of the mig1 promoter from the 5′ end and was highest in strain CL13cbx::pS148, which contained the shortest promoter fragment (Fig. 6B). This was corroborated by subsequent Northern analysis in which the same strains were grown in PD medium and total RNA was probed with eGFP (Fig. 6C). While weak hybridization signals were obtained in strains CL13cbx::pEN and CL13cbx::pES, the intensities of the hybridization signals increased with successive shortening of the promoters from the 5′ ends (Fig. 6C). These results suggest the existence of multiple negatively acting cis-regulatory elements between positions −148 and −2075. A study of the internal deletion derivatives revealed that crucial sequences for negative regulation are located (at least in part) between positions −230 and −363 (Fig. 6B and C, lanes 8 and 9). In addition, eGFP expression was lower in a strain harboring the internal deletion from positions −230 to −148 than in the respective strain not carrying this deletion (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 2 and 7), and enlarging the deletion extending from −363 to −230 to position −148 also resulted in a reduction of promoter activity (Fig. 6C, compare lanes 8 and 9). Not surprisingly, no expression of the mig1 gene was detected in transformants harboring a deletion in the mig1 promoter from positions 0 to −230. When the same set of strains was assayed for GFP expression after plant inoculation, a different expression profile emerged. Strong GFP activity was conferred by promoter constructs containing up to position −1019, the GFP activity dropped to barely detectable levels in promoter constructs extending to −363 and −230, and the activity was no longer detectable in the shortest construct, carrying sequences up to −148 (Fig. 6B). This illustrates that the expression level of this construct seen under axenic culture conditions is insufficient for GFP detection during fungal growth in planta. Interestingly, three of the internal deletion constructs conferred weak GFP activity in planta, suggesting that these regions harbor positively acting sequence elements required for induction during growth in planta.

FIG. 6.

mig1 promoter deletion analysis. (A) Genomic arrangement of plasmids pNN, pEN, pES, pSA, pSM, and pS148 after integration into the cbx locus by homologous recombination. Cleavage sites for SspI (S), BamHI (B), NcoI (N), SnaBI (Sn), AgeI (Ag), AvrII (Av), and MfeI (M) and their respective positions are indicated. The mig1 promoter is depicted by the shaded box. The thick line represents sequences flanking the cbx locus, the thin line represents sequences 3′ to the mig1 ORF, and broken lines represent the plasmid backbone. (B) Schematic representation of the various promoter deletion constructs and GFP activities of the respective transformants 4 to 6 days after inoculation of maize seedlings and during growth in liquid PD medium (axenic). Relative GFP activities were evaluated by microscopy and are indicated by + and − symbols. −, no fluorescence; +/−, very weak fluorescence, in planta detectable in the epidermal layer; +, weak GFP activity, in planta also detectable in cells underneath the epidermal layer; ++, intermediate GFP activity; +++, strong GFP activity detectable during all stages after penetration. (C) Strains CL13cbx::pNN, CL13cbx::pEN, CL13cbx::pES, CL13cbx::pSA, CL13cbx::pSM, CL13cbx::pS148, CL13cbx::pENΔM148, CL13cbx::pENΔAM, CL13cbx::pENΔA148, CL13cbx::pENΔAA, CL13cbx::pENΔM1, and CL13 were grown in PD for subsequent Northern analysis. Approximately 10 μg of total RNA was loaded. The blot was probed with the 32P-labeled NcoI-NotI eGFP fragment. The same filter was hybridized with a cbx probe (lower panel) to assess the amount of RNA loaded. Apparent size variations of the hybridizing mRNAs reflect differences in migration due to sample impurities.

DISCUSSION

The mig1 gene of U. maydis represents the first gene identified in this organism whose expression is coupled to the biotrophic phase. Based on reporter gene activity, the expression of mig1 is undetectable during hyphal growth on the leaf surface and formation of infection structures but is immediately switched on after penetration and remains high during fungal colonization between 4 and 11 days postinfection. Subsequently, the expression appears downregulated in proliferating sporogenic hyphae and becomes virtually undetectable in mature teliospores.

The mig1 gene is located in a locus containing a second gene, mdu1, which appears closely related to mig1 on the DNA level. However, the expression of mdu1 is not plant induced and expression levels during growth in axenic culture are undetectable by Northern analysis. We consider mdu1 to be a pseudogene for the following reason. The putative Mdu1 protein lacks similarity to Mig1, and this is due to a deletion in the 5′ coding region of the gene, leading to a frameshift. Despite this lack of similarity in coding potential, the sequences from positions 160 to 310 of mig1 and 1677 to 1827 of mdu1 are highly conserved (79% identity) and substitutions at synonymous coding positions clearly exceed those at nonsynonymous positions. This indicates that the respective highly conserved protein portion remained under selection and suggests that the Mdu1 protein may have been functional. In this respect, it should be interesting to analyze the mig1 locus in different U. maydis strains and other Ustilago species to ascertain the possibility that functional mdu1 genes still exist.

The mig1 gene encodes a highly charged protein of 185 amino acids, which is predicted to be processed at Ala-24 during the secretion process. Secretion was demonstrated by fusing the N-terminal 29 amino acids to eGFP. The N-terminal amino acid sequence of Mig1 reveals amino acid similarity to the N-terminal sequence of the U. maydis endoglucanase EGI, which is also secreted (32) (Fig. 5B). Both peptides are characterized by a basic N-terminal region followed by a central hydrophobic stretch and a more polar C-terminal region, and both fit the (−3,−1) rule (44). Mig1 contains the dipeptide PR at position 44, which could represent a cleavage site for the postulated U. maydis Kex2 protease (29). Cleavage at this site would further reduce the size of Mig1 to 140 amino acids. At present we cannot discriminate between the possibilities that Mig1 is secreted to the extracellular space or remains bound to the fungal cell wall. According to secondary-structure predictions made by using the program SOPM (10), the Mig1 protein could contain an α-helical region at the C terminus, as well as several β sheets and coiled regions, which may indicate that major domains of Mig1 are surface exposed. The predicted amino acid sequence of the mature Mig1 protein is not related to known proteins in databases and thus does not provide clues to its function. Because of the high level of expression during infection and the possible localization of Mig1 in the extracellular space or the fungal cell wall, this protein could function as an elicitor, similar to the action of fungal avr gene products (26), or serve to protect the fungus from host recognition. Alternatively, the Mig1 protein could be an enzyme required for nutrient aquisition or could be involved in nutrient uptake. Since pathogenic development was not compromised in Δmig1 mutant strains, this could point to a more subtle phenotype which escaped detection in our test system or could reflect functional gene redundancy.

For the Cladosporium fulvum Avr9 gene and a number of other plant-induced genes in fungi, it has been demonstrated that expression can also be increased under conditions of nitrogen and/or carbon deprivation (9, 30, 40, 43). In contrast, the mig1 gene was not induced under the starvation conditions tested. Neither exposure to cAMP, which is involved in a variety of processes including cell growth, morphogenesis, and sexual development in filamentous fungi (22, 23), nor exposure to metabolites released by wounding due to the infection conditions used or addition of plant extracts resulted in enhanced reporter gene expression.

The moderate expression of the mig1 gene in the diploid strain FBD11, which is heterozygous for a and b and undergoes filamentous growth on charcoal medium, is reminiscent of the U. maydis egl1 gene, which is not expressed in haploid sporidia but is strongly induced during filamentous growth of strain FBD11 (32). This indicates that mig1 gene expression responds to some extent to the a and b mating-type loci, which are known to regulate a large number of genes prior to infection (13).

To investigate the regulation of the mig1 promoter, we have successively shortened the mig1 gene promoter and could show that a 1,019-bp fragment confers strong differential expression. Further truncations from the 5′ end of the promoter resulted in significant expression of the mig1 gene during growth in PD. The expression level increased with the shortening of the 5′ region and was highest with a promoter fragment comprising only 148 bp. This indicates that the mig1 gene is under negative control and shows, furthermore, that several sequence elements upstream of position −148 must contribute to its repression under axenic culture conditions. The observation that promoter constructs carrying different internal deletions extending up to position −148 are significantly different in promoter activity can be explained by assuming context-dependent effects on the basal 148-bp promoter which are brought about by fusing it to different 5′ regions containing negatively acting sequence elements. In addition, we could localize a negative regulatory element between positions −363 and −230. Inspection of the nucleotide sequence revealed nine elements with the consensus sequence 5′-ACT(C/G)(C/G)ATA-3′ between positions −1954 and −307 in the mig1 promoter (Fig. 1 and data not shown), which locate to the region shown to provide for repression. Whereas motifs containing the 5′-GATA-3′ core occur in all GATA transcription factor binding sites, the sequence 5′-ACT(C/G)(C/G)ATA-3′ is not mentioned as a consensus protein binding sequence in the TRANSFAC database (15).

The negative regulation of mig1 is in contrast to that of Avr9 and MPG1 of C. fulvum and Magnaporthe grisea, respectively, the only plant-induced genes that have been analyzed in this respect in some detail. For both Avr9 and MPG1, it has been demonstrated that expression is strongly induced during nitrogen-limiting conditions, possibly as result of a positively acting regulatory factor (40, 43). In M. grisea, two regulatory genes, NPR1 and NPR2, that are required for MPG1 induction when strains are starved for either nitrate or glucose have been identified (25).

Although relief of repression is clearly observed in the mig1 promoter construct reduced in size to 148 bp, it is also apparent that the level of expression seen here does not approach that of mig1 gene expression observed during fungal colonization of the maize plant (compare Fig. 3B and 6C). We infer from these results that the mig1 gene promoter is subject to additional positive regulation. Internal promoter deletion studies allowed us to locate regions between positions −148 and −226, positions −230 and −363, and positions −363 to −519, respectively, contributing to high levels of GFP activity in planta. This is consistent with the inability of the 363-bp mig1 promoter fragment to confer efficient GFP activity in planta and illustrates an overlap of elements conferring negative and positive regulation in the mig1 promoter. The respective internal deletions affecting GFP activity during growth within the plant contained an Aspergillus nidulans AbaA consensus binding sequence, 5′-CATTC(C/T)-3′ (2), at position −154, a yeast GCN4 consensus binding sequence, 5′-TGACTC-3′ (16), at positions −234 and −410, and a sequence element that fits the consensus sequence of stress response elements (5′-AGGGG-3′) in various Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes (34) at position −360. Detailed mutational studies are necessary to assess the role of these motifs in mig1 regulation.

The availability of functional mig1-reporter gene fusions will allow us to address signaling between U. maydis and its host genetically. Through the isolation of U. maydis mutants derepressed in mig1 gene expression and subsequent cloning of the affected gene(s) by complementation, information on the numbers of genes involved as well as their specific function in repressing the mig1 gene promoter will be obtained. Such mutants could be selected for in a strain which carries an ectopic insertion of a resistance marker gene fused to a mig1 promoter fragment sufficient to confer differential regulation. Mutants derepressed in mig1 would express not only the resistance marker gene but also the endogenous mig1 gene. It is conceivable that relief from negative regulation may be prerequisite for the strong induction observed during growth in planta. Once available, the mig1 repressor mutants may also allow us to identify the inducing maize compounds directly; alternatively, they could be used to screen an expression library for the respective activator. By transferring this strategy to other genes, which have a plant-specific expression profile, we expect to uncover whether these genes are subject to control by common or distinct regulatory pathways.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nicole Euer and Sebastian Kolb for constructing plasmids and Christine Kerschbamer for providing technical assistance.

This work was supported by the Leibniz program of the DFG and by SFB369.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andrianopoulos A, Timberlake W E. The Aspergillus nidulans abaA gene encodes a transcriptional activator that acts as a genetic switch to control development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:2503–2515. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.4.2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banuett F, Herskowitz I. Different a alleles of Ustilago maydis are necessary for maintenance of filamentous growth but not for meiosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:5878–5882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.15.5878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banuett F. Genetics of Ustilago maydis, a fungal pathogen that induces tumors in maize. Annu Rev Genet Dev. 1995;122:2965–2976. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.001143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banuett F, Herskowitz I. Discrete developmental stages during teliospore formation in the corn smut fungus, Ustilago maydis. Annu Rev Genet. 1996;29:179–208. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.10.2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bohlmann R. Isolierung und Charakterisierung von filamentspezifisch exprimierten Genen aus Ustilago maydis. Ph.D. thesis. Munich, Germany: LMU München; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bölker M, Urban M, Kahmann R. The a mating type locus of Ustilago maydis specifies cell signalling components. Cell. 1992;68:441–450. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90182-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bölker M, Genin S, Lehmler C, Kahmann R. Genetic regulation of mating and dimorphism in Ustilago maydis. Can J Bot. 1995;73:320–325. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman M, Henricot B, Arnau J, Oliver R P. Starvation-induced genes of the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum are also induced during growth in planta. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 1997;10:1106–1109. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.9.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geourjon C, Deléage G. SOPM: a self-optimised method for protein secondary structure predictions. Protein Eng. 1994;7:157–164. doi: 10.1093/protein/7.2.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillissen B, Bergemann J, Sandmann C, Schroer B, Bölker M, Kahmann R. A two-component regulatory system for self/non-self recognition in Ustilago maydis. Cell. 1992;68:647–657. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90141-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gurr S J, Unkles S E, Kinghorn J R. The structure and organization of nuclear genes of filamentous fungi. In: Kinghorn J R, editor. Gene structure in eukaryotic microbes. Oxford, United Kingdom: IRL Press; 1988. pp. 93–139. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartmann H A, Kahmann R, Bölker M. The pheromone response factor coordinates filamentous growth and pathogenicity in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 1996;15:1632–1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartmann H A, Krüger J, Lottspeich F, Kahmann R. Environmental signals controlling sexual development of the corn smut fungus Ustilago maydis through the transcription factor Prf1. Plant Cell. 1999;11:1293–1306. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.7.1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heinemeyer T, Wingender E, Reuter I, Hermjakob H, Kel A E, Kel O V, Ignatieva E V, Ananko E A, Podkolodnaya O A, Kolpakov F A, Podkolodny N L, Kolchanov N A. Databases on transcriptional regulation: TRANSFAC, TRRD and COMPEL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:362–367. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill D E, Hope I A, Macke J P, Struhl K. Saturation mutagenesis of the yeast his3 regulatory site: requirements for transcriptional induction and for binding by GCN4 activator protein. Science. 1986;234:451–457. doi: 10.1126/science.3532321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman C S, Winston F. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene. 1987;57:267–272. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90131-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holliday R. Ustilago maydis. In: King R C, editor. Handbook of genetics. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1974. pp. 575–595. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kämper J, Reichmann M, Romeis T, Bölker M, Kahmann R. Multiallelic recognition: nonself-dependent dimerization of the bE and bW homeodomain proteins in Ustilago maydis. Cell. 1995;81:73–83. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90372-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keon J P R, White G A, Hargreaves J A. Isolation, characterization and sequence of a gene conferring resistance to the systemic fungicide carboxin from the maize smut pathogen Ustilago maydis. Curr Genet. 1991;19:475–481. doi: 10.1007/BF00312739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kronstad J W, Leong S A. The b mating-type locus of Ustilago maydis contains variable and constant regions. Genes Dev. 1990;4:1384–1395. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.8.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kronstad J W. Virulence and cAMP in smuts, blasts and blights. Trends Plant Sci. 1997;2:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Krüger J, Loubradou G, Regenfelder E, Hartmann A, Kahmann R. Crosstalk between cAMP and pheromone signalling pathways in Ustilago maydis. Mol Gen Genet. 1998;260:193–198. doi: 10.1007/s004380050885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau G, Hamer J E. Regulatory genes controlling MPG1 expression and pathogenicity in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1996;8:771–781. doi: 10.1105/tpc.8.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lauge R, De Wit P J. Fungal avirulence genes: structure and possible functions. Fungal Genet Biol. 1998;24:285–297. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang P, Pardee A B. Differential display of eukaryotic messenger RNA by means of the polymerase chain reaction. Science. 1992;257:967–971. doi: 10.1126/science.1354393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakai K, Kanehisa M. A knowledge base for predicting protein localization sites in eukaryotic cells. Genomics. 1992;14:897–911. doi: 10.1016/S0888-7543(05)80111-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park C M, Bruenn J A, Ganesa C, Flurkey W F, Bozarth R F, Koltin Y. Structure and heterologous expression of the Ustilago maydis viral toxin KP4. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:155–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pieterse C M, Derksen A M, Folders J, Govers F. Expression of the Phytophthora infestans ipiB and ipiO genes in planta and in vitro. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;244:269–277. doi: 10.1007/BF00285454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schauwecker F, Wanner G, Kahmann R. Filament-specific expression of a cellulase gene in the dimorphic fungus Ustilago maydis. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler. 1995;376:617–625. doi: 10.1515/bchm3.1995.376.10.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt M E, Brown T A, Trumpower B L. A rapid and simple method for preparation of RNA from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:3091–3092. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.10.3091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schüller C, Brewster J L, Alexander M R, Gustin M C, Ruis H. The HOG pathway controls osmotic regulation of transcription via the stress response element (STRE) of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae CTT1 gene. EMBO J. 1994;13:4382–4389. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06758.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schulz B, Banuett F, Dahl M, Schlesinger R, Schäfer W, Martin T, Herskowitz I, Kahmann R. The b alleles of U. maydis, whose combinations program pathogenic development, code for polypeptides containing a homeodomain-related motif. Cell. 1990;60:295–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90744-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snetselaar K M, Mims C W. Infection of maize stigmas by Ustilago maydis: light and electron microscopy. Phytopathology. 1993;83:843–850. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Snetselaar K M, Mims C W. Light and electron microscopy of Ustilago maydis hyphae in maize. Mycol Res. 1994;98:347–355. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spellig T, Bölker M, Lottspeich F, Frank R W, Kahmann R. Pheromones trigger filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis. EMBO J. 1994;13:1620–1627. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06425.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Spellig T, Bottin A, Kahmann R. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a new vital marker in the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis. Mol Gen Genet. 1996;252:503–509. doi: 10.1007/BF02172396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Talbot N J, Ebbole D J, Hamer J E. Identification and characterization of MPG1, a gene involved in pathogenicity from the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Plant Cell. 1993;5:1575–1590. doi: 10.1105/tpc.5.11.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Timberlake W E. Isolation of stage and cell-specific genes from fungi. In: Bailey J, editor. Biology and molecular biology of plant-pathogen interactions. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag KG; 1986. pp. 343–357. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsukuda T, Carleton S, Fotheringham S, Holloman W K. Isolation and characterization of an autonomously replicating sequence from Ustilago maydis. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:3703–3709. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.9.3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van den Ackerveken G F, Dunn R M, Cozijnsen A J, Vossen J P, Van den Broek H W, De Wit P J. Nitrogen limitation induces expression of the avirulence gene Avr9 in the tomato pathogen Cladosporium fulvum. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;243:277–285. doi: 10.1007/BF00301063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.von Heijne G. A new method for predicting signal sequence cleavage sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:4683–4690. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.11.4683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]