Abstract

To examine the functional role of the interaction between Munc18c and syntaxin 4 in the regulation of GLUT4 translocation in 3T3L1 adipocytes, we assessed the effects of introducing three different peptide fragments (20 to 24 amino acids) of Munc18c from evolutionarily conserved regions of the Sec1 protein family predicted to be solvent exposed. One peptide, termed 18c/pep3, inhibited the binding of full-length Munc18c to syntaxin 4, whereas expression of the other two peptides had no effect. In parallel, microinjection of 18c/pep3 but not a control peptide inhibited the insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 and insulin-responsive amino peptidase (IRAP) to the plasma membrane. In addition, expression of 18c/pep3 prevented the insulin-stimulated fusion of endogenous and enhanced green fluorescent protein epitope-tagged GLUT4- and IRAP-containing vesicles into the plasma membrane, as assessed by intact cell immunofluorescence. However, unlike the pattern of inhibition seen with full-length Munc18c expression, cells expressing 18c/pep3 displayed discrete clusters of GLUT4 abd IRAP storage vesicles at the cell surface which were not contiguous with the plasma membrane. Together, these data suggest that the interaction between Munc18c and syntaxin 4 is required for the integration of GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles into the plasma membrane but is not necessary for the insulin-stimulated trafficking to and association with the cell surface.

The insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4 is predominantly expressed in both striated muscle and adipose tissue and is responsible for the majority of insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (24). In the basal non-insulin-stimulated state, GLUT4 localizes to tubulovesicular elements and small intracellular vesicles throughout the cell cytoplasm (30, 31). Upon stimulation with insulin these GLUT4-containing compartments undergo a series of regulated steps leading to the trafficking, association, and eventual fusion with the plasma membrane (3, 14, 25, 27). This ultimately results in a large increase in the number of functional glucose transporters on the cell surface, termed translocation, and accounts for the majority, if not all, of the insulin-stimulated increase in glucose uptake. More recently, another cargo protein, insulin-responsive amino peptidase (IRAP), has been demonstrated to colocalize with GLUT4 and undergoes an identical pattern of insulin-stimulated translocation (14–16, 18, 20, 28).

The insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles shares several features with the docking and fusion of synaptic vesicles in neurotransmitter release. For example, the interaction of the GLUT4 vesicle v-SNARE protein, VAMP2, with the plasma membrane t-SNARE proteins, syntaxin 4 and SNAP23, is necessary for insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation (2, 19, 23, 33, 37). In addition to these t- and v-SNAREs, there are several accessory proteins involved in the regulation of the GLUT4 and IRAP vesicle translocation. We and others have observed that increased expression of Munc18c, but not Munc18b, the adipocyte homologues of the n-Sec1 regulator of synaptic vesicle trafficking, prevents the translocation of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles when overexpressed in 3T3L1 adipocytes (32, 34). In addition, only the Munc18c isoform binds to syntaxin 4 with high affinity (33, 34). These data, as well as several other expression studies (e.g., Sly1p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Rop in Drosophila melanogaster, and s-Sec1 in squid), are all consistent with this family of syntaxin-binding proteins functioning as a repressor of plasma membrane vesicle trafficking (5, 17, 26, 29). In contrast, null or temperature-sensitive mutations in S. cerevisiae, D. melanogaster, and Caenorhabditis elegans produce a phenotype with a dramatic reduction in vesicle exocytosis, suggesting that these proteins also play an essential positive role in promoting normal v- and t-SNARE function (10, 13, 21). Moreover, introduction of a specific peptide region of s-Sec1 into neurons inhibits the fusion of synaptic vesicles with the presynaptic membrane (5).

In this study we investigated whether Munc18c binding to syntaxin 4 is necessary for insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles. The data presented in this study suggest a model in which the association of Munc18c with syntaxin 4 is not necessary for the trafficking and association of GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles with the cell surface but is required at a subsequent plasma membrane integration-fusion step.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

A rabbit polyclonal GLUT4 antibody (IA02) was obtained as previously described (23). Rabbit polyclonal IRAP antibody was obtained from Steven Waters (Metabolex). Texas red-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-sheep IgG were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (West Grove, Pa.). Wheat germ agglutinin conjugated to Texas red (WGA-TxR) was purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, Oreg.). Vectashield was obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, Calif.). Mini-prep DNA and DNA agarose extraction kits were purchased from Qiagen (Santa Clarita, Calif.). The 18c/pep3 and scrambled 18c/pep3 peptides were chemically synthesized and purified to greater than 95% purity by Bio-Synthesis, Inc., Lewisville, Tex. Other chemicals were reagent grade or the best quality commercially available.

Plasmids.

The pEGFP-Flag-Munc18c (EGFP [enhanced green fluorescent protein]), pGLUT4-EGFP, pEGFP-IRAP, and pcDNA3-Flag-Munc18c constructs were prepared as described previously (34). The name of the EGFP constructs denotes the position of EGFP with respect to the particular protein of interest. For example, GLUT4-EGFP indicates the fusion of EGFP at the carboxyl terminus of GLUT4, whereas EGFP-IRAP denotes the fusion of EGFP at the amino terminus of IRAP. The full-length syntaxin 4 cDNA was obtained from Richard Scheller (Stanford University), and PCR primers directed against the 5′ and 3′ UTRs were used to amplify the DNA for subcloning into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of pcDNA3 (Invitrogen). The soluble syntaxin 4 (Syn4/ΔTM) construct was made by subcloning the cDNA used previously in yeast two-hybrid analyses (34) into the SmaI and SpeI sites of the pCMVflag vector (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.). The Munc18c peptide fragments were expressed as Flag-tagged fusions with the addition of a Kozak sequence, a 5′ start codon, and a 3′ stop codon. Peptide fragments were obtained by PCR with the following primers: 18c/pep1, 5′-GGGCCCAAGCTTAACGGGGAAATGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAAAAGCTTGAAGACTACTACAAAATTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGCGCTCTAGATTAGGACTGAGTTTTACCCTTTATTAGG-3′ (antisense); 18c/pep2, 5′-GGGCCCAAGCTTAACGGGGAAATGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAAAAAGAGAAGGAGGCAGTTCTTG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGTGCTCTAGATTAGTGTCGAACCCGCACCCACAGGCT-3′ (antisense); and 18c/pep3, 5′-GGGCCCAAGCTTAACGGGGAAATGGATTATAAAGATGATGATGATAAAAGAAAGGATCGGTCTGCAGAAGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-GGGCGCTCTAGATTACTCCATGATATCTTTGATAAAAGG-3′ (antisense). PCR products were digested and inserted into the HindIII and XbaI sites of pcDNA3. The double-expression or pDBL-GLUT4 construct, which coexpresses two cDNAs per plasmid, was prepared by modification of the pVgRXR plasmid (Invitrogen). Briefly, the RXR cDNA driven by the Rous sarcoma virus promoter was replaced with the GLUT4-EGFP cDNA fusion used previously (34), and the VgEcR cDNA downstream of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter was removed for insertion of a second cDNA. Full-length Munc18c was subcloned into the NheI and XbaI sites, while the peptide fragments were subcloned into the HindIII and XbaI sites, all located 3′ of the CMV promoter. The EGFP-Flag-18c/pep2 and EGFP-Flag-18c/pep3 constructs were made by subcloning of the HindIII/XbaI peptide fragments used to make the constructs described above into the EGFP-C3 vector and then sequenced for verification.

Cell culture and transient transfection.

3T3L1 preadipocytes were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, differentiated into adipocytes, and transfected by electroporation as previously described (34). As indicated in the figure legends, cotransfected experiments were performed with 50 μg of pEGFP-tagged plasmid DNA plus 200 μg of additional plasmid DNA for analysis of EGFP fluorescence. In the case of proteins expressed from the pDBL vector, 200 μg of DNA was used. After electroporation, the cells were allowed to adhere to coverslips in 35-cm tissue culture dishes for 18 to 24 h and were then serum starved for 2 h prior to stimulation with 100 nM insulin at 37°C.

Whole-cell immunofluorescence.

Fully differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated as described above and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.02% Triton X-100 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.45) for 10 min at room temperature. All subsequent steps in the whole-cell immunofluorescence labeling were done at room temperature. Fixed cells were rinsed with PBS three times and blocked with 1% bovine serum albumin and 5% donkey serum in PBS for 1 h. Blocked cells were incubated with a polyclonal GLUT4 antibody for 1 h diluted in blocking solution at 1:250 or 1:500 for basal or insulin-treated cells, respectively. Cells were washed three times with PBS for 5 min each and incubated with secondary anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Texas red for 1 h. The secondary antibody was rinsed from the cells three times for 10 min each time with PBS, and coverslips were mounted on slides by using Vectashield mounting medium. Whole-cell immunofluorescence analysis of endogenous IRAP was performed similarly, with the substitution of a polyclonal IRAP antibody diluted at 1:100 for both basal and insulin-treated cells. Whole-cell immunofluorescence with WGA-TxR involved the fixing of electroporated cells with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by a 30-min blocking period. Blocked cells were incubated with WGA-TxR for 30 min. Double-labeled images were collected by using confocal microscopy (×60). Each field comprised of multiple cells is actually a compilation of cells from that group that expressed the EGFP fusion protein as described in the figure legends.

Single-cell microinjection and plasma membrane sheet assay.

Fully differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were grown on 35-mm dishes and microinjected as described previously (6). Prior to microinjection the medium was changed to Leibovitz's L-15 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 3 h and then warmed on a 37°C heating stage of a Nikon Diaphot phase-contrast microscope. Cells were impaled and coinjected with 6 mg of the MBP-Ras fusion protein per ml plus 6.6 mM 18c/pep3 peptide (RKDRSAEETFQLSRWTPFIKDIME) or the control scrambled 18c/pep3 peptide (RETKFQMRISPEFAKLDTIRSWDE). After microinjection, the medium was changed to Leibovitz's L-15 containing 0.2% bovine serum albumin, and the adipocytes were incubated for an additional 2 h at 37°C. Plasma membrane sheets were prepared as previously described and fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde for 20 min on ice. The fixed plasma membrane sheets were then blocked with 5% donkey serum for 45 min at 37°C, followed by incubation with a rabbit polyclonal GLUT4 or IRAP antibody (1:100 dilution of antisera) plus a sheep polyclonal MBP-Ras antibody for 15 h at 4°C. The samples were then incubated with lissamine rhodamine-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit and fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated donkey anti-sheep secondary antibodies, respectively, for 4 h in the dark and visualized by confocal fluorescence microscopy (×60).

RESULTS

Increased expression of syntaxin 4 can rescue the inhibitory effect of overexpressed Munc18c.

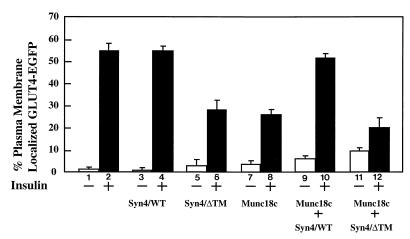

Previously, we and others have observed that increased expression of Munc18c but not Munc18b in 3T3L1 adipocytes inhibits the insulin-stimulated plasma membrane translocation of the endogenous GLUT4 protein (32, 34). We have recapitulated these data by cotransfection of 3T3L1 adipocytes with a double cDNA expression vector encoding for Munc18c and a GLUT4-EGFP fusion construct (Fig. 1). Quantitation of the number of cells displaying a smooth continuous plasma membrane rim fluorescence indicated that insulin stimulated the translocation of GLUT4-EGFP in approximately 55% of the transfected cell population (Fig. 1, bars 1 and 2). Coexpression of GLUT4-EGFP with Munc18c resulted in only approximately 26% of the cells having specific insulin-stimulated translocation (Fig. 1, bars 7 and 8). Although expression of full-length syntaxin 4 had no effect on insulin-stimulated GLUT4-EGFP translocation itself (Fig. 1, bars 3 and 4), coexpression of full-length syntaxin 4 with Munc18c restored the number of cells displaying insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation to that occurring in the absence of Munc18c (Fig. 1, bars 9 and 10).

FIG. 1.

Expression of syntaxin 4 rescues the Munc18c-induced inhibition of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 200 μg of pDBL-GLUT4-EGFP or 200 μg of pDBL-GLUT4-EGFP/Munc18c plus 200 μg of pcDNA3-syntaxin 4 (Syn4/WT) or the soluble domain of syntaxin 4 (Syn4/ΔTM). Cells were allowed to recover for 18 h and then stimulated without (open bars) or with (solid bars) 100 nM insulin for 30 min. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and fluorescence visualized by confocal microscopy (×60). Each point represents the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three to six independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

The ability of syntaxin 4 to rescue the inhibition due to increased Munc18c expression may have resulted from a simple titration of the excess Munc18c protein. To address this issue, we also expressed the cytosolic domain of syntaxin 4 (Syn4/ΔTM), which does not localize to the plasma membrane but can bind to Munc18c (34). Consistent with previous reports (2, 23), expression of the syntaxin 4 cytosolic domain also inhibited GLUT4 translocation, presumably by associating with VAMP2 and/or Munc18c and thereby blocking interaction with plasma membrane-localized endogenous syntaxin 4 (Fig. 1, bars 5 and 6). In any case, coexpression of the soluble syntaxin 4 domain failed to rescue the inhibition of GLUT4 translocation induced by Munc18c (Fig. 1, bars 11 and 12). Thus, these data indicate that the localization of the syntaxin 4-Munc18c complex to the plasma membrane is required for insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation. In addition, these data suggest that the stoichiometry between the plasma membrane-localized Munc18c and syntaxin 4 is not critical as long as syntaxin 4 is in excess over the plasma membrane-localized Munc18c protein.

Expression of the Munc18c peptide (18c/pep3) inhibits insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 and IRAP in 3T3L1 adipocytes.

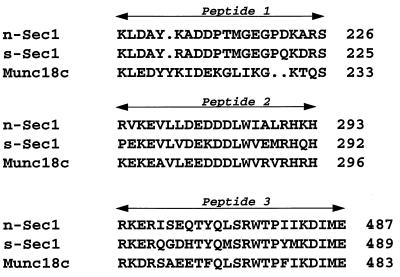

Analyses of yeast, Drosophila, and squid have identified three specific regions within the Munc18 family of proteins that are important for function and/or are solvent exposed (4, 5, 10). A comparison among these peptides in n-Sec1, s-Sec1, and Munc18c is shown in Fig. 2. These regions have a high degree of amino acid conservation between all three isoforms, with identities of 35% for peptide 1, 48% for peptide 2, and 62% for peptide 3. Considering conservative substitutions, the amino acid similarity rises to 68% for peptide 1, 81% for peptide 2, and 80% for peptide 3. We have named the respective three Munc18c peptides 18c/pep1, 18c/pep2, and 18c/pep3.

FIG. 2.

Peptide sequence alignment of three predicted solvent-exposed regions of the n-Sec1, s-Sec1, and Munc18c proteins. Amino acid residue numbers are listed to the right of each peptide.

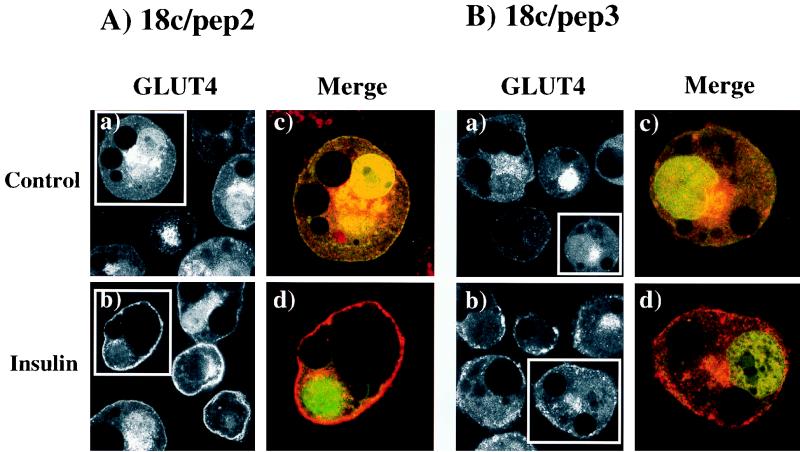

To examine the potential effect of the Munc18c peptides, we expressed 18c/pep2 and 18c/pep3 as EGFP fusion proteins and evaluated their effects upon the insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 by whole-cell immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 3). In the basal state, endogenous GLUT4 was localized to the perinuclear region and small vesicles scattered throughout the cytoplasm. However, as typically observed after insulin stimulation, the GLUT4 protein was translocated to the plasma membrane; this distribution remained unchanged by expression of the EGFP-18c/pep2 peptide fusion (Fig. 3A, panels a and b). As with the control and 18c/pep2-transfected cells, the expression of EGFP-18c/pep3 had no effect upon the basal state distribution of GLUT4 (Fig. 3B, panel a). In contrast, 18c/pep3 inhibited the insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 (Fig. 3B, panel b). Importantly, expression of EGFP-18c/pep3 appeared to increase the number of GLUT4 vesicles juxtaposed to the plasma membrane (Fig. 3B, panel b).

FIG. 3.

Expression of the 18c/pep3 peptide inhibits insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 50 μg of the pEGFP-18c/pep2 (A) or 50 μg of the pEGFP-18c/pep3 (B) expression plasmids. After 18 h, the cells were stimulated without (panels a and c) or with (panels b and d) 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde plus 0.02% Triton X-100 and incubated with the rabbit polyclonal GLUT4 antibody for 1 h, followed by the addition of anti-rabbit Texas red-conjugated secondary antibody. The EGFP and Texas red staining was visualized by confocal microscopy (×47, panels a and b; ×94, panels c and d). No cells showed rim fluorescence in the absence of insulin. In the presence of insulin, EGFP-18c/pep2- and EGFP-18c/pep3-expressing cells displayed 72 and 22% rim fluorescence, respectively. These results are representative of the mean of at least 25 cells per experiment from three independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

This observation was more apparent when we examined endogenous GLUT4 translocation under increased magnification. In the boxed cells in Fig. 3, the merged image from EGFP-18c/pep2 (green) was compared with that of endogenous GLUT4 (red). The EGFP-18c/pep2 and EGFP-18c/pep3 fluorescence was observed throughout the cell cytoplasm and in the nucleus (Fig. 3A and B, panels c and d). Similarly, expression of EGFP itself also resulted in a strong nuclear, as well as cytoplasmic, localization (data not shown). These data indicated that the concentration of EGFP in the nucleus of 3T3L1 adipocytes is a property of EGFP in this cell context and is not due to the presence of the additional fusion peptide sequences. Regardless, the insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation was seen as a continuous rim of immunofluorescence distinct from the green nuclear and cytosolic labeling of EGFP-18c/pep2 (Fig. 3A, panels c and d). However, although expression of EGFP-18c/pep3 had no significant effect on the basal-state distribution of GLUT4, it resulted in the accumulation of multiple GLUT4 vesicles just under the plasma membrane in various states of aggregation (Fig. 3B, panels c and d). In addition to GLUT4, these insulin-responsive translocating compartments are also enriched with a 165-kDa amino peptidase termed IRAP or vp165 (15, 16, 18, 20, 28) and responded to EGFP-18c/pep3 expression in an identical manner (data not shown). Together, these results demonstrate that expression of 18c/pep3 but not 18c/pep2 inhibits the insulin-stimulated translocation of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles.

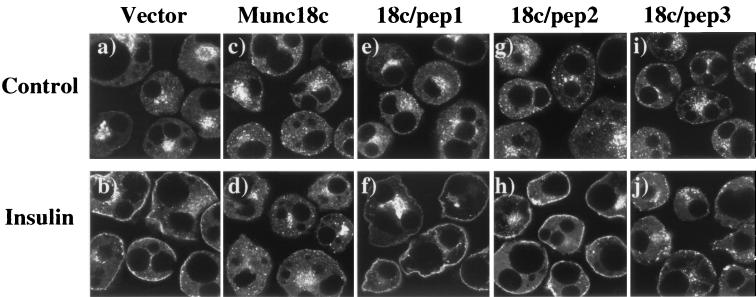

Expression of 18c/pep3 results in an insulin-stimulated accumulation of GLUT4-EGFP and EGFP-IRAP at the cell surface.

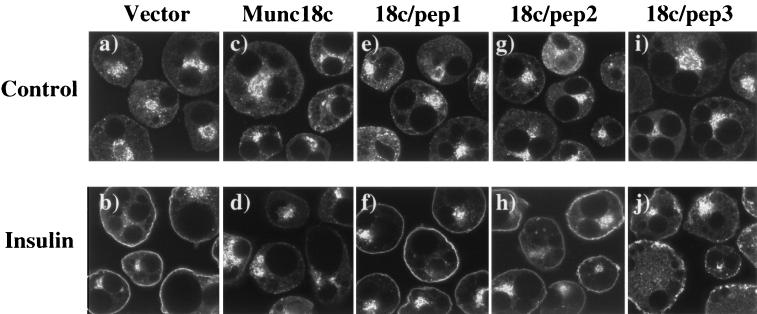

We more closely examined the effects of the Munc18c protein and peptides on the insulin-stimulated translocation by using a GLUT4-EGFP fusion protein (Fig. 4). As previously observed (34), expression of GLUT4-EGFP in 3T3L1 adipocytes resulted in a similar distribution to endogenous GLUT4, being primarily localized to the perinuclear region and small vesicles throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 4a). Insulin stimulation induces a marked redistribution of GLUT4-EGFP to the cell surface, resulting in the characteristic formation of an essentially continuous rim of fluorescence (Fig. 4b). As with endogenous GLUT4, coexpression with Munc18c had no significant effect on the basal distribution of GLUT4-EGFP but inhibited its translocation to the plasma membrane (Fig. 4c and d). Consistent with the endogenous GLUT4, coexpression of 18c/pep1 and 18c/pep2 did not change the basal distribution or the insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4-EGFP (Fig. 4e to h). In contrast to 18c/pep2, expression of 18c/pep3 efficiently blocked the insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4-EGFP (Fig. 4i and j). More surprisingly, the distribution of GLUT4-EGFP was localized in clusters of fluorescent vesicles just below the plasma membrane, a markedly different pattern from that seen in the basal state.

FIG. 4.

Expression of the 18c/pep3 peptide results in the accumulation of GLUT4-EGFP-containing vesicles at the plasma membrane in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 200 μg of the pDBL-GLUT4-EGFP alone or with the following cDNAs also present in the double-expression vector: Munc18c, 18c/pep1, 18c/pep2, or 18c/pep3. The cells were allowed to recover for 18 h and then stimulated without (panels a, c, e, g, and i) or with (panels b, d, f, h, and j) 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and fluorescence visualized by confocal microscopy (×42). In the presence of insulin, 55% ± 5% of the cells expressing GLUT4-EGFP displayed rim fluorescence. This percentage was reduced to 25% ± 4% or 24% ± 2% when Munc18c or 18c/pep3 was coexpressed, respectively. Coexpression of 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 had no effect upon GLUT4-EGFP rim fluorescence. These results are representative of the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three to five independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

Consistent with the effects of Munc18c and 18c/pep3 on GLUT4-EGFP translocation, essentially identical results were obtained when we examined the localization of EGFP-IRAP (Fig. 5). In the basal state, EGFP-IRAP was localized to the perinuclear region and small vesicles throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5a). Insulin stimulation resulted in the translocation of EGFP-IRAP to the plasma membrane, as visualized by the appearance of continuous rim fluorescence (Fig. 5b). Coexpression of Munc18c inhibited the insulin-stimulated translocation of EGFP-IRAP, while cells expressing either 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 still displayed the typical insulin-stimulated rim fluorescence (Fig. 5e to h). However, as with GLUT4-EGFP, coexpression of 18c/pep3 not only inhibited the insulin-stimulated formation of continuous EGFP-IRAP rim fluorescence but also resulted in clusters of fluorescence just below the cell surface membrane (Fig. 5i and j).

FIG. 5.

Expression of the 18c/pep3 peptide results in the accumulation of EGFP-IRAP-containing vesicles at the plasma membrane in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 50 μg of EGFP-IRAP plus 200 μg of either the empty vector (pcDNA3), Munc18c, 18c/pep1, 18c/pep2, or 18c/pep3 and allowed to recover for 18 h. The cells were then stimulated without (panels a, c, e, g, and i) or with (panels b, d, f, h, and j) 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and fluorescence visualized by confocal microscopy (×42). In the presence of insulin, 62% ± 6% of the cells expressing GLUT4-EGFP showed rim fluorescence. This percentage was reduced to 26% ± 4% or 26% ± 5% when Munc18c or 18c/pep3 was coexpressed, respectively. Coexpression of 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 had no effect upon GLUT4-EGFP rim fluorescence. These results are representative of the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

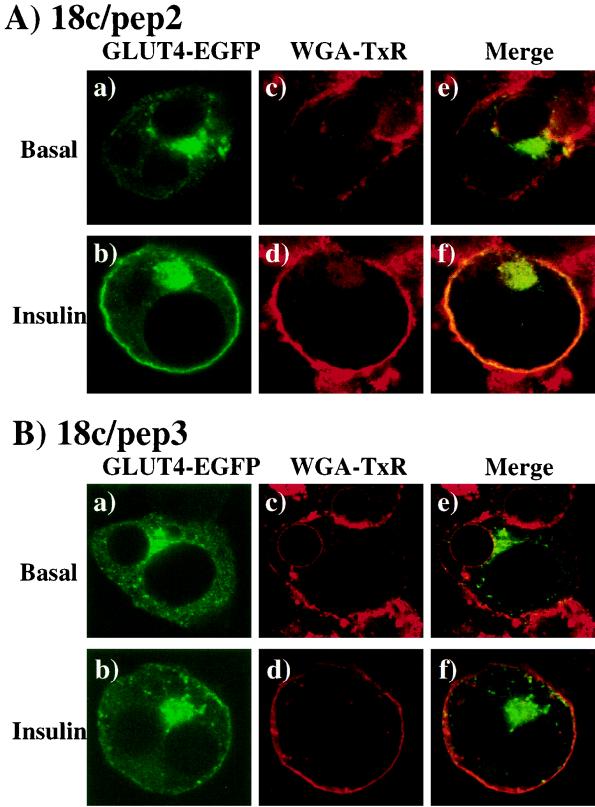

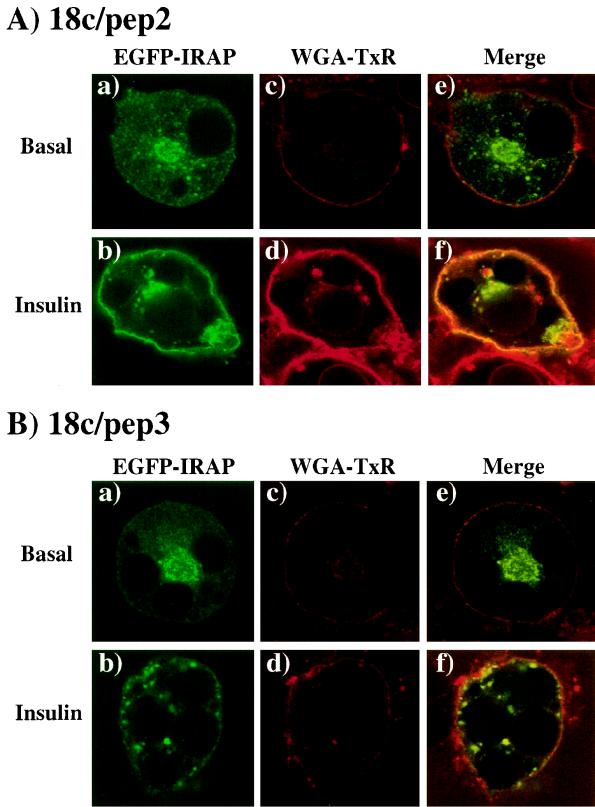

To further assess the relationship of these clusters with the plasma membrane, we compared the colocalization of GLUT4-EGFP with WGA-TxR as a marker for the cell surface (Fig. 6). WGA-TxR binds sialic acid and N-acetylglucosaminyl residues of glycosylated proteins that coat the exterior of the cell surface, which is visualized as a continuous red rim by using whole-cell fluorescence microscopy. As expected, in the basal state, GLUT4-EGFP was found localized to the perinuclear region and small cytoplasmic vesicles when coexpressed with 18c/pep2 (Fig. 6A, panel a). Insulin stimulation resulted in the translocation of GLUT4-EGFP to the plasma membrane, thereby producing the characteristic rim fluorescence (Fig. 6A, panel b). Although colabeling with WGA-TxR gave some diffuse and nonspecific fluorescent signal, the plasma membrane demarcation is clearly evident (Fig. 6A, panels c and d). Furthermore, the merged images demonstrated a clear separation of the WGA-TxR signal from GLUT4-EGFP in the basal state, which colocalized at the cell surface after insulin stimulation (Fig. 6A, panels e and f). Identical results were also observed for the coexpression of GLUT4-EGFP with the empty vector and 18c/pep1 (data not shown). Similarly, coexpression of 18c/pep3 did not affect the basal intracellular distribution of GLUT4-EGFP and was not associated with the plasma membrane WGA-TxR marker (Fig. 6B, panels a and c). However, insulin stimulation resulted in the appearance of GLUT4-EGFP in clusters that were near the cell surface but were not continuous and did not colocalize with WGA-TxR (Fig. 6B, panels b and d). Again, the GLUT4-EGFP-containing vesicles appear to have accumulated beneath the plasma membrane (Fig. 6B, panels e and f).

FIG. 6.

Expression of the 18c/pep3 peptide inhibits insulin-stimulated plasma membrane integration of GLUT4-EGFP in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 200 μg of the pDBL-GLUT4-EGFP plus the 18c/pep2 or 18c/pep3 cDNAs also present in the double-expression vector and then allowed to recover for 18 h. The cells were then stimulated without (panels a, c, and e) or with (panels b, d, and f) 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with WGA-TxR for 30 min, and the fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy (×46). In the presence of insulin, 49% ± 8% of the cells expressing GLUT4-EGFP showed rim fluorescence. This percentage was reduced to 24% ± 6% or 22% ± 3% when Munc18c or 18c/pep3 was coexpressed, respectively. Coexpression of 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 had no effect upon GLUT4-EGFP rim fluorescence. These results are representative of the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

Essentially identical data was obtained for the colocalization of EGFP-IRAP versus WGA-TxR (Fig. 7). That is, coexpression of 18c/pep2 did not affect the basal intracellular distribution of EGFP-IRAP and was not associated with the plasma membrane WGA-TxR marker (Fig. 7A, panels a, c, and e). Insulin induced a redistribution of the EGFP and IRAP to the plasma membrane, showing a merger of the green and red signals (Fig. 7A, panels b, d, and f). Like 18c/pep2, 18c/pep3 expression had no differential effects upon the basal distribution of EGFP-IRAP (Fig. 7B, panels a, c, and e). Unlike 18c/pep2, coexpression of 18c/pep3 resulted in a noncontinuous clustered distribution of EGFP-IRAP vesicles gathered beneath the cell surface (Fig. 7B, panels b, d, and f). Altogether, these data demonstrate that the expression of 18c/pep3 does not prevent the trafficking or association of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles with the plasma membrane. However, expression of this peptide apparently inhibits the integration or fusion of the vesicles into the plasma membrane.

FIG. 7.

Expression of the 18c/pep3 peptide inhibits insulin-stimulated membrane integration of EGFP-IRAP in 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 50 μg of EGFP-IRAP plus 200 μg of 18c/pep2 or 18c/pep3 and then allowed to recover for 18 h. The cells were then stimulated without (panels a, c, and e) or with (panels b, d, and f) 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and incubated with WGA-TxR for 30 min, and the fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy (×46). In the presence of insulin, 62% ± 6% of the cells expressing GLUT4-EGFP showed rim fluorescence. This percentage was reduced to 26% ± 5% or 26% ± 3% when Munc18c or 18c/pep3 was coexpressed, respectively. Coexpression of 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 had no effect upon GLUT4-EGFP rim fluorescence. These results are representative of the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

Microinjection of 18c/pep3 inhibits the insulin-stimulated integration of the GLUT4- and IRAP-containing vesicles into the plasma membrane.

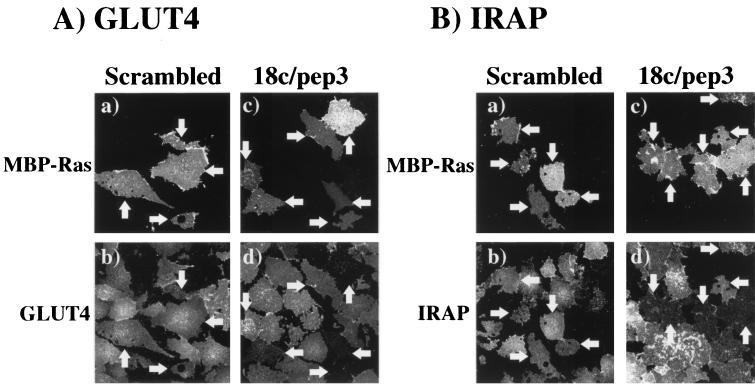

To further differentiate the vesicles clusters localized near the plasma membrane from those integrated into the plasma membrane, we used the plasma membrane sheet assay. Previously, we and others have observed that increased expression of Munc18c inhibited the insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 but not GLUT1 vesicles into the plasma membrane (32, 34). The chemically synthesized 18c/pep3 peptide or a scrambled peptide version of 18c/pep3 (Scrambled) having the same amino acid composition were comicroinjected along with MBP-Ras as a marker for the microinjected cells (Fig. 8). After comicroinjection of MBP-Ras with either Scrambled or 18c/pep3, the isolated plasma membrane sheets displayed a specific MBP fluorescence signal from the microinjected cells compared to the surrounding noninjected cells (Fig. 8A, panels a and c). In the absence of insulin, GLUT4 is intracellularly localized with almost no detectable GLUT4 immunofluorescence in the isolated plasma membrane sheets (data not shown). However, insulin stimulation resulted in a strong plasma membrane sheet GLUT4 immunofluorescence, a finding indicative of GLUT4 vesicle translocation and protein integration into the plasma membrane (Fig. 8A, panels b and d). Microinjection of the Scrambled peptide had no significant effect on the insulin stimulation of GLUT4 translocation compared to the surrounding nonmicroinjected cells (Fig. 8A, panel b). In contrast, microinjection with 18c/pep3 resulted in a reduction in the number of plasma membrane sheets displaying GLUT4 translocation (Fig. 8A, panel d). In multiple experiments, microinjection of 18c/pep3 inhibited the insulin-stimulated plasma membrane integration by 62% compared to the Scrambled peptide.

FIG. 8.

Microinjection of the 18c/pep3 peptide inhibits insulin-stimulated translocation of endogenous GLUT4 and IRAP in isolated plasma membrane sheets from 3T3L1 adipocytes. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were microinjected with approximately 0.1 pl of MBP-Ras (6 mg/ml) mixed 1:1 with 6.6 mM of either the Scrambled peptide (panels a and b) or the 18c/pep3 peptide (panels c and d). The cells were then stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 30 min at 37°C. Plasma membrane sheets from the microinjected cells were identified by immunofluorescence localization with the MBP-specific antibody (panels a and c). The translocations of endogenous GLUT4 (A) and endogenous IRAP (B) were determined in the same samples by double labeling with the GLUT4 and IRAP antibodies (panels b and d). These are representative fields of at least 25 cells per experiment from two to three independent sets of electroporated adipocytes. The plasma membrane sheets derived from the microinjected cells are indicated by the arrows.

Similarly, microinjection of the Scrambled peptide had no effect on the ability of insulin to induce the plasma membrane integration of IRAP compared to the surrounding nonmicroinjected cells (Fig. 8B, panels a and b). However, microinjection of 18c/pep3 resulted in an overall 58% reduction in the number of isolated plasma membrane sheets displaying insulin-stimulated IRAP plasma membrane integration compared to the Scrambled peptide (Fig. 8B, panels c and d). Thus, these data are consistent with the localization of GLUT4 and IRAP observed in the intact cells and indicate that the 18c/pep3 peptide specifically inhibits the insulin-stimulated plasma membrane integration of both GLUT4- and IRAP-containing vesicles.

Expression of 18c/pep3 inhibits the association of Munc18c with syntaxin 4.

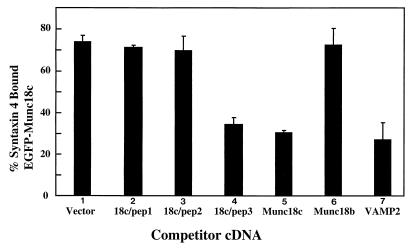

Previous studies attempting to map the n-Sec1 domains responsible for its interaction with syntaxin 1 were unable to generate deletion or truncation mutants that retain their ability to bind to syntaxin 1 (11). Similarly, we have observed that deleted forms of Munc18c are incapable of interacting with syntaxin 4 (data not shown). Having been unsuccessful in expressing a soluble Munc18c fusion protein in bacteria (data not shown), we have used a plasma membrane competition assay to test the effects of the Munc18c peptides on the association of syntaxin 4 with Munc18c (34). In this assay, EGFP-Munc18c is targeted to the plasma membrane by coexpression with syntaxin 4. The effects of various competitors are then determined by scoring their ability to displace the EGFP-Munc18c from the plasma membrane and reduce the number of cells displaying rim fluorescence. In this system, expression of the empty vector results in approximately 75% of the cells positive for EGFP-Munc18c fluorescence at cell surface (Fig. 9, bar 1). Coexpression of 18c/pep1 or 18c/pep2 had no significant effect on the number of EGFP-Munc18c plasma membrane-positive cells (Fig. 9, bars 2 and 3). By contrast, coexpression of 18c/pep3 reduced the number of cell surface-positive cells to the same extent as increased expression of untagged Munc18c itself (Fig. 9, bars 4 and 5). Munc18b, which does not associate with syntaxin 4, had no effect on EGFP-Munc18c localization, whereas the established competitor for syntaxin 4 binding VAMP2 was just as effective as 18c/pep3 and untagged Munc18c (Fig. 9, bars 6 and 7). These data suggest that the expression of 18c/pep3 inhibits the interaction of Munc18c with syntaxin 4.

FIG. 9.

Expression of 18c/pep3 disrupts the Munc18c-syntaxin 4 complex. Differentiated 3T3L1 adipocytes were electroporated with 50 μg of EGFP-Munc18c plus 200 μg of syntaxin 4 and one of the following competitor protein cDNAs in the pcDNA3 vector: Munc18c, VAMP2, Munc18b, 18c/pep1, 18c/pep2, or 18c/pep3. The cells were allowed to recover for 18 h and were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and the fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy. Data are depicted as the percentage of cells exhibiting plasma membrane rim fluorescence. Each point represents the mean ± the standard error of at least 25 cells per experiment from three to five independent sets of electroporated adipocytes.

DISCUSSION

It has become increasingly apparent that the mammalian Munc18 proteins play critical roles in synaptic transmission and in insulin-stimulated GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicle translocation. However, the precise role and mechanism of action appear paradoxical. On one hand, increased expression of Munc18 isoforms in mammalian cells and their counterparts in lower organisms results in an inhibition of vesicle exocytosis (17, 29, 32, 34). These data have been interpreted as evidence for an inhibitory function for Munc18 and that exocytosis would therefore require a derepression of this activity. On the other hand, genetic ablation of the D. melanogaster and C. elegans Munc18 homologs (Rop and Unc18, respectively) also results in a complete loss of exocytosis, suggesting that these proteins are necessary positive effectors of vesicular trafficking (10, 13). Consistent with this positive role in vesicle trafficking, expression of the temperature-sensitive Munc18 yeast homolog Sly1p prevents endoplasmic-reticulum-derived transport vesicle fusion with Golgi membranes at the nonpermissive temperature. However, the association of these vesicles to Golgi membranes was unaffected (1, 35).

These observations are consistent with our results on the insulin regulation of GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicle translocation to the plasma membrane in adipocytes. We and others have demonstrated that overexpression of Munc18c also inhibits insulin-stimulated GLUT4 storage vesicle translocation (32, 34). Similarly, in the present study we observed that overexpression of Munc18c inhibited insulin-stimulated GLUT4 and IRAP vesicle translocation. At face value, these data would be interpreted as evidence for a repressor function of Munc18c. However, we also observed that disruption of the endogenous interaction between syntaxin 4 and Munc18c resulted in an inhibition of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 and IRAP translocation.

This apparent contradiction can be reconciled by considering two additional experimental observations. First, overexpression of Munc18c completely prevents any discernible movement of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles. In contrast, disruption of the endogenous syntaxin 4-Munc18c complex allows for GLUT4 and IRAP vesicle association with the plasma membrane but prevents the subsequent membrane integration events. Second, overexpression of the full-length plasma-membrane-bound syntaxin 4 does not inhibit the insulin-stimulated translocation of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles. In fact, increased expression of full-length syntaxin 4 rescues the inhibition observed by overexpression of the Munc18c protein. This latter finding demonstrates that Munc18c functions at substoichiometric amounts relative to syntaxin 4. This finding is consistent with the quantitation of a 10/1 ratio of syntaxin to Munc18 proteins in rat hepatocytes (8). Importantly, the vast majority of both endogenous and overexpressed syntaxin 4 is localized to the plasma membrane (reference 34 and unpublished results). Similarly, Munc18c is predominantly localized to the plasma membrane when syntaxin 4 is in excess (34).

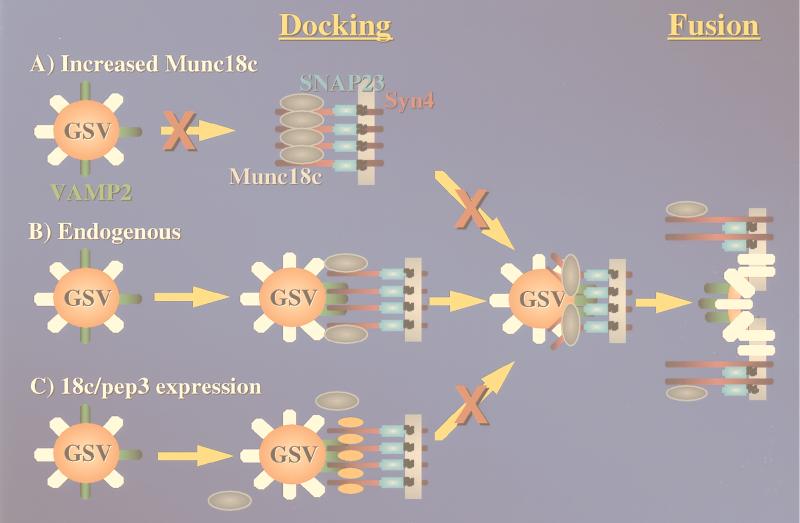

Taking these data into account, we can propose a model depicting the following positive fusogenic function for Munc18c in insulin-stimulated GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicle translocation (Fig. 10). In the basal state, only a small fraction of the total plasma membrane pool of syntaxin 4 is associated with Munc18c. This results in excess free syntaxin 4 on the plasma membrane that is available for binding to VAMP2 present on the GLUT4- and IRAP-containing cargo vesicles. Presumably, this interaction between VAMP2 and syntaxin 4 does not occur in the basal state either because there is negative regulation or because the vesicles remain sequestered away from the syntaxin 4 binding sites. In any case, after insulin stimulation these vesicles can now traffic to the plasma-membrane-localized syntaxin 4 binding sites. However, increased expression of Munc18c results in the occupancy of all the plasma membrane syntaxin 4 binding sites (Fig. 10A). Since syntaxin 4 binding to Munc18c is mutually exclusive of that with VAMP2 (32–34), the complete occupancy of syntaxin 4 prevents the binding of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles. In addition, this model would account for the ability of syntaxin 4 overexpression to reverse the overexpressed Munc18c inhibition of GLUT4 and IRAP translocation by providing additional free plasma membrane binding sites. This interpretation provides a mechanism by which overexpression of Munc18c alone can function in a dominant-interfering manner.

FIG. 10.

Schematic model for the functional role of endogenous Munc18c as a required positive effector of plasma membrane GLUT4-IRAP vesicle fusion. (B) In this model, insulin stimulation results in the trafficking of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles (GSV) to the plasma membrane. These vesicles then associate or dock via the interaction between the v-SNARE VAMP2 and the plasma membrane t-SNAREs syntaxin 4 (Syn4) and SNAP23. Munc18c is associated with syntaxin 4 but at a substoichiometric amount such that free syntaxin 4 binding sites remain available. After docking, the Munc18c provides a positive fusogenic event necessary for the incorporation of the GLUT4-IRAP proteins into the plasma membrane. (A) Overexpression of Munc18c occludes all the syntaxin 4 binding sites, thereby preventing the association of the GSV with the plasma membrane and hence translocation. (C) In contrast, expression of the 18c/pep3 displaces the prebound Munc18c from syntaxin 4, but since there are excess syntaxin 4 binding sites the docking occurs normally. However, in the absence of a catalytic amount of bound Munc18c, fusion does not occur. Thus, both increased expression of Munc18c and disruption of Munc18c-syntaxin 4 binding results in an overall inhibition of GLUT4 and IRAP translocation but through different mechanisms.

In contrast, under normal conditions the insulin-stimulated trafficking and plasma membrane binding of the GLUT4 and IRAP vesicles to syntaxin 4 generate a complete fusion complex in the presence of an appropriate physiological level of Munc18c (Fig. 10B). This is consistent with the effect of 18c/pep3 expression, which disrupts the normal endogenous interaction of Munc18c with syntaxin 4. Under these conditions, insulin is fully capable of inducing the apparent plasma membrane association of the GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles. However, these plasma-membrane-bound GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicles are blocked at this stage of translocation and therefore cannot proceed with the final plasma membrane fusion steps (Fig. 10C).

Even though this model can account for all the experimental observations to date, it should be recognized that Munc18c may possibly interact with other important regulatory proteins involved in GLUT4 translocation. For example, it has been recently reported that the Munc18a isoform can interact with two other proteins, Doc2β (36) and X11γ/Mint (22). However, we have not been able to observe any significant interaction of Munc18c with Doc2β or X11γ/Mint by either coimmunoprecipitation or colocalization by confocal fluorescent microscopy (unpublished results). Alternatively, several studies have suggested that Munc18a function can be regulated by protein kinase C- and cdk5-dependent phosphorylation (7, 9, 12). Whether or not Munc18c undergoes insulin-stimulated phosphorylation and its potential relationship with syntaxin 4 binding remains an important question for future study.

In any case, our data demonstrate that overexpression of Munc18c results in the inhibition of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicle translocation. However, this phenomenon probably results from the saturation of the plasma membrane vesicle binding sites and thereby masks the true function of endogenous Munc18c. Based upon the required interaction of syntaxin 4 with Munc18c for GLUT4 and IRAP storage vesicle incorporation into the plasma membrane, we hypothesize that Munc18c plays an essential positive role at a post-plasma membrane association step and is likely involved in the regulation of plasma membrane integration and fusion events.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Scheller, Hideki Katagiri, and Steven Waters for providing the cDNAs for syntaxin 4, Munc18b, and IRAP and for the IRAP antibody.

This study was supported by research grants DK33823 and DK25925 from the National Institutes of Health. D.C.T. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship training grant DK09813 from the National Institutes of Health. M.K. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Juvenile Diabetes Foundation, International.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cao X, Ballew N, Barlowe C. Initial docking of ER-derived vesicles requires Uso1p and Ypt1p but is independent of SNARE proteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:2156–2165. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheatham B, Volchuk A, Kahn C R, Wang L, Rhodes C J, Klip A. Insulin-stimulated translocation of GLUT4 glucose transporters requires SNARE-complex proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:15169–15173. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.26.15169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Czech M P. Molecular actions of insulin on glucose transport. Annu Rev Nutr. 1995;15:441–471. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.002301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dascher C, Ossig R, Gallwitz D, Schmitt H D. Identification and structure of four yeast genes (SLY) that are able to suppress the functional loss of YPT1, a member of the RAS superfamily. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11:872–885. doi: 10.1128/mcb.11.2.872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dresbach T, Burns M E, O'Connor V, De Bello W M, Betz W M. A neuronal Sec1 homolog regulates neurotransmitter release at the squid giant synapse. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2923–2932. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02923.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elmendorf J S, Chen D, Pessin J E. Guanosine 5′-O-(3-thiotriphosphate) (GTPγS) stimulation of GLUT4 translocation is tyrosine kinase-dependent. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13289–13296. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fletcher A I, Shuang R, Giovannucci D R, Zhang L, Bittner M A, Stuenkel E L. Regulation of exocytosis by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 via phosphorylation of Munc18. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4027–4035. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.7.4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fujita H, Tuma P L, Finnegan C M, Locco L, Hubbard A L. Endogenous syntaxins 2, 3 and 4 exhibit distinct but overlapping patterns of expression at the hepatocyte plasma membrane. Biochem J. 1998;329:527–538. doi: 10.1042/bj3290527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujita Y, Sasaki T, Fukui K, Kotani H, Kimura T, Hata Y, Sudhof T C, Scheller R H, Takai Y. Phosphorylation of Munc-18/n-Sec1/rbSec1 by protein kinase C: its implication in regulating the interaction of Munc-18/n-Sec1/rbSec1 with syntaxin. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7265–7268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison S D, Broadie K, van de Goor J, Rubin G M. Mutations in the Drosophila Rop gene suggest a function in general secretion and synaptic transmission. Neuron. 1994;13:555–566. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hata Y, Sudhof T C. A novel ubiquitous form of Munc-18 interacts with multiple syntaxins. Use of the yeast two-hybrid system to study interactions between proteins involved in membrane traffic. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13022–13028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hirling H, Scheller R H. Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle proteins: modulation of the alpha SNAP interaction with the core complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11945–11949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hosono R, Hekimi S, Kamiya Y, Sassa T, Murakami S, Nishiwaki K, Miwa J, Taketo A, Kodaira K I. The unc-18 gene encodes a novel protein affecting the kinetics of acetylcholine metabolism in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. J Neurochem. 1992;58:1517–1525. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb11373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kandror K V, Pilch P F. Compartmentalization of protein traffic in insulin-sensitive cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:E1–E14. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1996.271.1.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kandror K V, Pilch P F. gp160, a tissue-specific marker for insulin-activated glucose transport. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:8017–8021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.17.8017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandror K V, Yu L, Pilch P F. The major protein of GLUT4-containing vesicles, gp160, has aminopeptidase activity. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30777–30780. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lupashin V V, Waters M G. t-SNARE activation through transient interaction with a rab-like guanosine triphosphatase. Science. 1997;276:1255–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5316.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malide D, St-Denis J F, Keller S R, Cushman S W. Vp165 and GLUT4 share similar vesicle pools along their trafficking pathways in rat adipose cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;409:461–468. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00563-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin L B, Shewan A, Millar C A, Gould G W, James D E. Vesicle-associated membrane protein 2 plays a specific role in the insulin-dependent trafficking of the facilitative glucose transporter GLUT4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:1444–1452. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.3.1444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin S, Rice J E, Gould G W, Keller S R, Slot J W, James D E. The glucose transporter GLUT4 and the aminopeptidase vp165 colocalise in tubulo-vesicular elements in adipocytes and cardiomyocytes. J Cell Sci. 1997;110:2281–2291. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.18.2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novick P, Schekman R. Secretion and cell-surface growth are blocked in a temperature-sensitive mutant of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:1858–1862. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okamoto M, Sudhof T C. Mints, Munc18-interacting proteins in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31459–31464. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson A L, Knight J B, Pessin J E. Syntaxin 4, VAMP2, and/or VAMP3/cellubrevin are functional target membrane and vesicle SNAP receptors for insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation in adipocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2425–2435. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.5.2425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Olson A L, Pessin J E. Structure, function, and regulation of the mammalian facilitative glucose transporter gene family. Annu Rev Nutr. 1996;16:235–256. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.16.070196.001315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pessin J E, Thurmond D C, Elmendorf J S, Coker K J, Okada S. Molecular basis of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 vesicle trafficking. Location! Location! Location! J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2593–2596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.5.2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pevsner J, Hsu S C, Braun J E, Calakos N, Ting A E, Bennett M K, Scheller R H. Specificity and regulation of a synaptic vesicle docking complex. Neuron. 1994;13:353–361. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90352-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rea S, James D E. Moving GLUT4. The biogenesis and trafficking of GLUT4 storage vesicles. Diabetes. 1997;46:1667–1677. doi: 10.2337/diab.46.11.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ross S A, Scott H M, Morris N J, Leung W Y, Mao F, Lienhard G E, Keller S R. Characterization of the insulin-regulated membrane aminopeptidase in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:3328–3332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.6.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schulze K L, Littleton J T, Salzberg A, Halachmi N, Stern M, Lev Z, Bellen H J. rop, a Drosophila homolog of yeast Sec1 and vertebrate n-Sec1/Munc-18 proteins, is a negative regulator of neurotransmitter release in vivo. Neuron. 1994;13:1099–1108. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slot J W, Geuze H J, Gigengack S, James D E, Lienhard G E. Translocation of the glucose transporter GLUT4 in cardiac myocytes of the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7815–7819. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Slot J W, Geuze H J, Gigengack S, Lienhard G E, James D E. Immuno-localization of the insulin regulatable glucose transporter in brown adipose tissue of the rat. J Cell Biol. 1991;113:123–135. doi: 10.1083/jcb.113.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamori Y, Kawanishi M, Niki T, Shinoda H, Araki S, Okazawa H, Kasuga M. Inhibition of insulin-induced GLUT4 translocation by Munc18c through interaction with syntaxin 4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19740–19746. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tellam J T, Macaulay S L, McIntosh S, Hewish D R, Ward C W, James D E. Characterization of Munc-18c and syntaxin-4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Putative role in insulin-dependent movement of GLUT-4. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:6179–6186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thurmond D C, Ceresa B P, Okada S, Elmendorf J S, Coker K, Pessin J E. Regulation of insulin-stimulated GLUT4 translocation by Munc18c in 3T3L1 adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33876–33883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Rheenen S M, Cao X, Lupashin V V, Barlowe C, Waters M G. Sec35p, a novel peripheral membrane protein, is required for ER to golgi vesicle docking. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:1107–1119. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.5.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verhage M, de Vries K J, Roshol H, Burbach J P, Gispen W H, Sudhof T C. DOC2 proteins in rat brain: complementary distribution and proposed function as vesicular adapter proteins in early stages of secretion. Neuron. 1997;18:453–461. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81245-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volchuk A, Wang Q, Ewart H S, Liu Z, He L, Bennett M K, Klip A. Syntaxin 4 in 3T3-L1 adipocytes: regulation by insulin and participation in insulin-dependent glucose transport. Mol Biol Cell. 1996;7:1075–1082. doi: 10.1091/mbc.7.7.1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]