Abstract

Background

As the urgent care landscape evolves, specialized musculoskeletal urgent care centers (MUCCs) are becoming more prevalent. MUCCs have been offered as a convenient, cost-effective option for timely acute orthopaedic care. However, a recent “secret-shopper” study on patient access to MUCCs in Connecticut demonstrated that patients with Medicaid had limited access to these orthopaedic-specific urgent care centers. To investigate how generalizable these regional findings are to the United States, we conducted a nationwide secret-shopper study of MUCCs to identify determinants of patient access.

Questions/purposes

(1) What proportion of MUCCs in the United States provide access for patients with Medicaid insurance? (2) What factors are associated with MUCCs providing access for patients with Medicaid insurance? (3) What barriers exist for patients seeking care at MUCCs?

Methods

An online search of all MUCCs across the United States was conducted in this cross-sectional study. Three separate search modalities were used to gather a complete list. Of the 565 identified, 558 were contacted by phone with investigators posing over the telephone as simulated patients seeking treatment for a sprained ankle. Thirty-nine percent (216 of 558) of centers were located in the South, 13% (71 of 558) in the West, 25% (138 of 558) in the Midwest, and 24% (133 of 558) in New England. This study was given an exemption waiver by our institution’s IRB. MUCCs were contacted using a standardized script to assess acceptance of Medicaid insurance and identify barriers to care. Question 1 was answered through determining the percentage of MUCCs that accepted Medicaid insurance. Question 2 considered whether there was an association between Medicaid acceptance and factors such as Medicaid physician reimbursements or MUCC center type. Question 3 sought to characterize the prevalence of any other means of limiting access for Medicaid patients, including requiring a referral for a visit and disallowing continuity of care at that MUCC.

Results

Of the MUCCs contacted, 58% (323 of 558) accepted Medicaid insurance. In 16 states, the proportion of MUCCs that accepted Medicaid was equal to or less than 50%. In 22 states, all MUCCs surveyed accepted Medicaid insurance. Academic-affiliated MUCCs accepted Medicaid patients at a higher proportion than centers owned by private practices (odds ratio 14 [95% CI 4.2 to 44]; p < 0.001). States with higher Medicaid physician reimbursements saw proportional increases in the percentage of MUCCs that accepted Medicaid insurance under multivariable analysis (OR 36 [95% CI 14 to 99]; p < 0.001). Barriers to care for Medicaid patients characterized included location restriction and primary care physician referral requirements.

Conclusion

It is clear that musculoskeletal urgent care at these centers is inaccessible to a large segment of the Medicaid-insured population. This inaccessibility seems to be related to state Medicaid physician fee schedules and a center’s affiliation with a private orthopaedic practice, indicating how underlying financial pressures influence private practice policies. Ultimately, the refusal of Medicaid by MUCCs may lead to disparities in which patients with private insurance are cared for at MUCCs, while those with Medicaid may experience delays in care. Going forward, there are three main options to tackle this issue: increasing Medicaid physician reimbursement to provide a financial incentive, establishing stricter standards for MUCCs to operate at the state level, or streamlining administration to reduce costs overall. Further research will be necessary to evaluate which policy intervention will be most effective.

Level of Evidence

Level II, prognostic study.

Introduction

Because it is challenging to access musculoskeletal care [19] from overcrowded emergency departments [14, 15], an increasing number of patients are turning to musculoskeletal-specific urgent care centers (MUCCs) for accessible, affordable care. Treatment at MUCCs has many benefits, such as decreasing emergency department overcrowding, providing more cost-effective care, and offering patients shorter wait times for care [2, 5, 15, 16, 21, 25]. In addition, MUCCs have an advantage over general-purpose UCCs, as they are staffed by dedicated orthopaedic providers, allowing for expedited access to specialty musculoskeletal care [2].

The existing studies on Medicaid acceptance at UCCs either focus only on general-care urgent care centers or have an extremely limited geographic scope [10, 26]. In a 2018 study of MUCCs in Connecticut, the authors found that there were policies in place designed to limit the proportion of patients with Medicaid insurance. All 29 MUCCs in Connecticut were owned by private practices. Of these MUCCs, 66% did not accept any form of Medicaid insurance, and 21% had a variety of barriers in place including location restrictions and referral out after the initial visit to reduce the number of patients with Medicaid who would receive treatment [26]. Although centers may not outright refuse to care for patients with Medicaid, refusing to accept Medicaid insurance and requiring cash payment is likely to act as a significant barrier to care [22]. This may have been a function of the relatively low Medicaid physician reimbursement in Connecticut. According to an industry whitepaper from the Urgent Care Association, on average, 400 to 500 new UCCs open each year, with numbers swelling from 6400 in 2014 to 8774 UCCs in 2018. Additionally, the whitepaper predicts a continued rise in specialty UCCs, in particular, MUCCs [23]. Given the overall low proportion of Medicaid acceptance by MUCCs in Connecticut and the expanding presence of MUCCs nationally, it is important to investigate patient access to MUCCs on a national level to identify the variables associated with Medicaid acceptance based on state-level policies, including Medicaid reimbursements.

Therefore, we comprehensively surveyed all MUCCs across all 50 states and asked: (1) What proportion of MUCCs in the United States provide access for patients with Medicaid insurance? (2) What factors are associated with MUCCs providing access for patients with Medicaid insurance? (3) What barriers exist for patients seeking care at MUCCs?

Materials and Methods

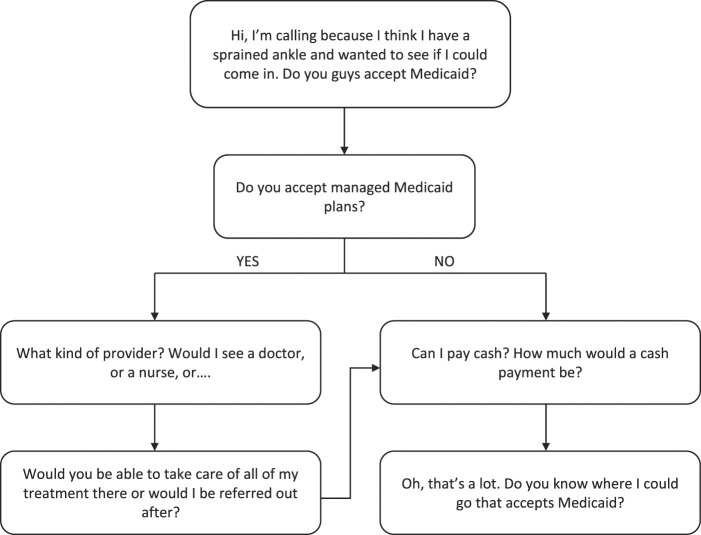

Our cross-sectional study used a secret-shopper methodology, as set out in previous studies [10, 13, 26], to evaluate access to MUCCs. Our study population included all MUCCs in the 50 states of the United States, located using Google Maps [6], Solv Health [20], and the Urgent Care Association’s Find an Urgent Care Database [24]. Three separate search modalities were used to maximize MUCCs identified and gather a complete list. The search terms “MSK,” “musculoskeletal,” or “orthopedic” with “walk-in clinic” or “urgent care center” were used. We included any MUCC self-labeled as such a facility. To be considered an MUCC, we required that the center have its own website, share a website with a medical or surgical practice, or have a unique location marker on Google Maps. We excluded general UCCs and orthopaedic clinic offices. We included MUCCs that were co-located with a clinic office. We identified 565 MUCCs across the United States that met these criteria. In June 2019, the authors called each center following a standardized script (Fig. 1). Responses were obtained from 558 of the 565 MUCCs.

Fig. 1.

The call script used by researchers when contacting MUCCs.

Investigators posed as fictitious patients seeking a consultation for a sprained ankle. The primary outcome measure was the acceptance of Medicaid insurance. Investigators inquired about acceptance of both state-run and managed care organization Medicaid plans such as Centene, Amerigroup, or WellCare. Managed care organization acceptance was determined by comparing plans named using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s list of Medicaid managed care organization plans [11]. Secondary outcomes included barriers to care. At the conclusion of each call, no appointments were confirmed to avoid inconveniencing providers.

Individual MUCCs were classified into three categories: 6% (31 of 558) were nonaffiliated, defined as an MUCC with no connection to a hospital or practice; 86% (479 of 558) were extension, defined as an MUCC affiliated with an independent private practice or with a nonacademic health system; and 9% (48 of 558) were academic, defined as an MUCC associated with a teaching hospital. Classifications were chosen based on organizations having similar business models and patterns of behavior within each group. Geographic region of MUCCs was characterized as well, with 39% (216 of 558) of centers located in the South, 13% (71 of 558) in the West, 25% (138 of 558) in the Midwest, and 24% (133 of 558) in New England. Demographic information including Joint Commission Accreditation status, Urgent Care Association Accreditation Status, total patient population in the MUCC’s ZIP code, and ZIP code median household income were collected for each MUCC. MUCCs were located in ZIP codes with an average median household income of USD 72,200. State Medicaid expansion status was determined using the Kaiser Family Foundation’s Status of State Action page [12]. State median income and the proportion of the state population that was uninsured were determined from United States Census data. Medicaid physician reimbursements for a Level III new patient were obtained from individual states’ Medicaid website physician fee schedules.

Primary and Secondary Study Outcomes

Our primary study goal was to characterize the acceptance of Medicaid at MUCCs and variables related to acceptance of Medicaid. To achieve this, we calculated the proportion of MUCCs in the United States that provide access for patients with Medicaid insurance. Access was defined as acceptance of Medicaid insurance. This was done by assessing the Medicaid acceptance policies of all MUCCs characterized via a secret-shopper phone survey. To further our investigation, we examined the factors that are associated with MUCCs providing access for patients with Medicaid insurance. We combined our results from this phone survey with center-specific and state-level information, including center classification and state Medicaid physician reimbursements. These data on MUCC characteristics collected outside of the phone survey were then analyzed for potential relationships with Medicaid acceptance.

Our secondary study goal was to identify any other barriers to care for Medicaid patients at MUCCs. To achieve this, we investigated the barriers that exist for patients seeking care at MUCCs. This was assessed through the secret-shopper phone survey. In addition to general acceptance of Medicaid, MUCCs were also questioned about any other stipulations related to treatment of patients with Medicaid insurance. Barriers anticipated included geographic restriction on Medicaid acceptance and mandatory referrals limiting care.

Ethical Approval

Our study design was reviewed and received an institutional review board exemption waiver by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using JMP Pro 13. We performed univariable and multivariable regressions to evaluate the association of center demographics with the acceptance of Medicaid insurance. We explored factors like state Medicaid expansion status, the proportion of state on Medicaid, physician reimbursement, and center classification in a univariable model, and advanced those that were associated with a p value < 0.05 to a multivariable model. For the individual center-level analysis, the following factors were thus advanced and considered in that multivariable model: classification of center, median household income by ZIP code, and population by ZIP code. In the state-level analysis, Medicaid physician reimbursement, the proportion of the state uninsured, and state median income were considered in that multivariable model.

Results

Proportion of MUCCs that Accept Medicaid Insurance

A total of 58% (323 of 558) of the MUCCs accepted Medicaid insurance, either state-run or managed care organization (Table 1). We found that there was substantial variation by state in availability of MUCC access to patients with Medicaid insurance. In 22 states, all MUCCs surveyed accepted Medicaid insurance. However, in 16 states, the proportion of MUCCs accepting Medicaid was at or below 50% (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual centers (n = 558)

| Characteristic | Population parameter |

| Overall Medicaid acceptance | 58 (323) |

| Classification of center | |

| Independent | 6 (31) |

| Extension of hospital or physician practice | 86 (479) |

| Academic | 9 (48) |

| Population per UCC ZIP code | 33,315 ± 14,001 |

| Household median income per UCC ZIP code in USD | 72,200 ± 27,844 |

Data presented as % (n) or mean ± SD.

Fig. 2.

This graph displays the Medicaid acceptance proportion by state.

Factors Associated with Accepting Medicaid Insurance

We found that a higher proportion of academic-affiliated MUCCs (88% [42 of 48] versus 36% [11 of 31]; odds ratio 14 [95% CI 4.2 to 44]; p < 0.001) accepted patients with Medicaid than did independent centers (Table 2). The individual state Medicaid physician reimbursement (OR 36 [95% CI 14 to 99]; p < 0.001), the proportion of the state’s population who were uninsured (OR 0.007 [95% CI 0.002 to 0.021]; p < 0.001), and state median income (OR 0.12 [95% CI 0.05 to 0.30]; p < 0.001) were factors associated with higher odds of Medicaid acceptance at MUCCs (Table 3). We did not observe a difference in the proportion of Medicaid acceptance between MUCCs located in states that had expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and MUCCs located in states that did not expand Medicaid (56% [192 of 342] versus 61% [131 of 216]; OR 1.2 [95% CI 0.85 to 1.7]; p = 0.29).

Table 2.

Variables associated with Medicaid acceptance (individual centers)

| Parameter | Medicaid acceptance, % (n) | Multivariable OR/range OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Classification of center | |||

| Independent (n = 31) | 35 (11) | Ref. | |

| Extension of hospital or physician practice (n = 479) | 56 (270) | 2.1 (0.9-4.6) | 0.08 |

| Academic (n = 48) | 88 (42) | 14 (4.2-44) | < 0.001 |

| Median household income by ZIP code | 0.012 (0.003-0.05) | < 0.001 | |

| Population by ZIP code | 0.23 (0.07-0.75) | 0.01 |

Table 3.

Variables associated with Medicaid acceptance (state-level data)

| Parameter | Multivariable OR/range OR (95% CI) | p value |

| Reimbursement (bivariate fit) | ||

| 36 (14-99) | < 0.001 | |

| Proportion of state uninsured (bivariate fit) | ||

| 0.007 (0.002-0.021) | < 0.001 | |

| State median income (bivariate fit) | ||

| 0.12 (0.05-0.30) | < 0.001 | |

Other Barriers to Access

We identified other barriers, including: 5% (17 of 323) of centers accepted Medicaid but restricted Medicaid coverage based on a patient’s location of residence, 27% (88 of 323) required a referral for a patient with Medicaid’s initial visit, and 8% (26 of 323) mandated a referral out of the MUCC after the first visit as opposed to continuing care at the MUCC. In some cases, referrals may reflect state-specific legal Medicaid regulations and not an individual clinic decision. Of the MUCCs surveyed, 39% (127 of 323) accepted Medicaid but had one type of barrier in place. One percent (4 of 323) had more than one barrier in place.

Discussion

MUCCs continue to rise in relevance as their numbers grow across the United States [23], with more individuals seeking out shorter wait times and lower costs. However, it has been demonstrated that the urgent care model may disproportionately limit access to care for patients on Medicaid, as indicated by studies with a narrow geographic focus on MUCCs and studies that focused on general UCCs [10, 26]. Our study sought to characterize the phenomenon of disparities in care for Medicaid patients previously characterized in the evidence [1, 7, 13, 18, 27], but specifically regarding Medicaid-insured patients seeking musculoskeletal urgent care. We found that there is large variation in Medicaid acceptance rates across the country, indicating a need for state-specific legislation to tackle disparities in acceptance. Additionally, privately owned centers and centers located in states with low Medicaid physician reimbursement had lower levels of Medicaid acceptance, demonstrating that any policy change must tackle some aspect of MUCCs’ profit-driven motivations, whether that be incentivizing them or legislatively tempering them.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, no centralized database of MUCCs exists, so our research team needed to conduct an online search. Although we intended our search to be comprehensive of all MUCCs across the United States, it is possible that some MUCCs were not contacted because of a lack of an identifying presence on the internet. However, we used broad search terms to identify MUCCs to maximize the likelihood of a comprehensive list. Additionally, an individual MUCC’s decision to accept Medicaid is a complex choice that ultimately factors in many cost of practice variables, including each state’s individual Medicaid policies, liability and malpractice environment, and administrative paperwork burden. Physician reimbursement takes into account cost of practice. However, although we considered reimbursement for part of our analysis, we did not take into account cost of practice. Despite this, in evaluating the very strong association between reimbursement and Medicaid acceptance as well as evaluating the profit-driven motives of an MUCC, there likely are much greater factors that drive the relationship.

Further, there are limitations with regard to variation in rural and urban locations. Functionality of location analysis on the basis of ZIP code is limited, as there is likely a substantial amount of crossover from ZIP codes located close to each other in urban areas with drastically different demographic features. Further, urban areas are more likely to have more options for musculoskeletal care nearby, while those in rural areas may have fewer options and possibly limited to MUCCs. Although the analysis has its limitations, the instances of crossover between ZIP codes is a smaller factor compared with the overall trend of ZIP code demographics.

Additionally, another limitation in our dataset is the sparseness of centers classified as independent or academic compared to those classified as extension of hospital or physician practice. Due to this, the confidence interval of the odds ratio is quite wide, yielding an imprecise estimate of exactly how much more likely an academic center is to accept Medicaid than an independent center. However, while the magnitude of this relationship is not precisely estimated, the overall direction of the relationship is still clear.

Proportion of MUCCs that Accept Medicaid Insurance

We found that there was substantial variation by state in the availability of MUCC access to patients with Medicaid insurance, with an overall proportion of Medicaid acceptance of 58%. In particular, California and Florida had the lowest proportions of Medicaid acceptance, of 0.00% and 0.04%, respectively (Figure 2). This indicates a widespread lack of treatment at MUCCs for a large segment of the Medicaid-insured population. This finding gives a national perspective to a previous regional study that concluded MUCCs in Connecticut decline to treat Medicaid-insured patients [26]. This variation by state suggests that state-level policy changes could be preferred over federal changes, possibly by strengthening regulations and requiring MUCCs to accept Medicaid patients as a prerequisite for state-level licensing. Our findings also contrast with a recent study that characterized the proportion of nonspecialized urgent care center Medicaid acceptance as 79% [10]. Although both general and specialized urgent care center business models are profit-driven, the much lower proportion of MUCCs that accept Medicaid may be explained by some other factor related to their orthopaedic focus. In this instance, urgent care centers providing specialty care seem to be less likely to accept patients with Medicaid than those providing general care.

Factors Associated with Accepting Medicaid Insurance

We found that center classification as academic as opposed to privately owned and higher Medicaid physician reimbursement were associated with an MUCC being more likely to provide access. In fact, 8 of the 10 highest reimbursement states had 100% Medicaid acceptance rates. This finding clearly indicates that MUCCs operate on a profit-driven model and may be motivated to broaden access through financial incentives such as raising reimbursements in states with lower proportions of Medicaid acceptance. This follows a general pattern of increased physician reimbursements correlating with improved access to care by patients with Medicaid. One previous study that evaluated the effect of insurance type on access to knee arthroplasty and revision found that higher Medicaid physician reimbursements were directly correlated with Medicaid patient appointment success for both procedures [13]. Another study found that increases in the Medicaid-to-Medicare reimbursement ratio raises the rates of outpatient physician visits, emergency department use, and prescription fills [4]. Increasing Medicaid physician reimbursements may be a powerful lever to increase patient access to care, especially in profit-driven settings such as MUCCs.

Other Barriers to Access

Even at centers that accept Medicaid-insured patients, Medicaid patients continue to face additional barriers, including residence restrictions, requirement of a referral for the initial treatment, and a referral after the initial visit. Referral requirements specific to Medicaid-insured patients were found across the United States; this is a well-known policy usually enforced by state Medicaid programs to control costs. Because of this referral requirement, patients with Medicaid have more difficulty scheduling appointments with healthcare providers, even though those providers accept their insurance [8, 9]. If state Medicaid programs are seeking to cut down on costs, possible solutions lie in streamlining the overhead required for healthcare administration, as proposed by both reform advocates and government healthcare bureaucrats [3, 17]. For example, an updated Medicaid reimbursement model proposed by the New York State Department of Health could be established for urgent care providers that recognizes the facility as direct, streamlining the reimbursement accounting process by directing reimbursements to the facility as opposed to each individual provider.

Conclusion

Based on the results of our national secret-shopper survey, we found that MUCCs limit access to patients with Medicaid, and the disparity between privately owned and academic MUCCs indicates that financial pressures influence clinic policies. A possible solution lies in adjusting Medicaid physician reimbursements. However, physician reimbursements are just one of many factors that influence practice policy decisions in complex state healthcare economic environments. As privately run MUCCs pursue privately insured patients and place a disproportionate financial burden on academic safety net centers, it may become necessary to require Medicaid acceptance for state licensing to avoid collapse of public and academic hospitals. On an even greater scale, large inefficiencies lie in healthcare administration, hindering budgets for the Medicaid program. Reforms to streamline administration, especially in the relationship between Medicaid and MUCCs, are necessary to free up more dollars for actual patients instead of overhead. Further investigation is needed to determine the effect of reimbursement and state policy on patient access to care at MUCCs.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that there are no funding or commercial associations (consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article related to the author or any immediate family members.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Ethical approval for this study was waived by the Yale University Institutional Review Board.

Contributor Information

Laurie C. Yousman, Email: Laurie.yousman@yale.edu.

Walter R. Hsiang, Email: walter.hsiang@yale.edu.

Grace Jin, Email: grace.jin@yale.edu.

Michael Najem, Email: michael.najem@yale.edu.

Alison Mosier-Mills, Email: alison.mosiermills@gmail.com.

Akshay Khunte, Email: akshay.khunte@yale.edu.

Siddharth Jain, Email: siddharth.jain@yale.edu.

Howard Forman, Email: howard.forman@yale.edu.

References

- 1.Alcalá HE, Cook DM. Racial discrimination in health care and utilization of health care: a cross-sectional study of California adults. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1760-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson TJ, Althausen PL. The role of dedicated musculoskeletal urgent care centers in reducing cost and improving access to orthopaedic care. J Orthop Trauma. 2016;30:S3-S6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blasier RD. CORR Insights®: Musculoskeletal urgent care centers in Connecticut restrict patients with Medicaid insurance based on policy and location. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1450-1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Callison K, Nguyen BT. The effect of Medicaid physician fee increases on health care access, utilization, and expenditures. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:690-710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlson LC, Raja AS, Dworkis DA, et al. Impact of urgent care openings on emergency department visits to two academic medical centers within an integrated health care system. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;75:382-391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Google Maps. Google Maps. Available at: https://www.google.com/maps. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 7.Higgins PS, Shugrue N, Ruiz K, Robison J. Medicare and Medicaid users speak out about their health care: the real, the ideal, and how to get there. Popul Health Manag. 2015;18:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsiang W, McGeoch C, Lee S, et al. The effect of insurance type on access to inguinal hernia repair under the Affordable Care Act. Surgery. 2018;164:201-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsiang WR, Lukasiewicz A, Gentry M, et al. Medicaid patients have greater difficulty scheduling health care appointments compared with private insurance patients: a meta-analysis. Inq J Health Care Organ Provis Financ. 2019;56:004695801983811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hsiang WR, Wiznia D, Yousman L, et al. Urgent care centers delay emergent surgical care based on patient insurance status in the United States. Ann Surg. 2020;272:548-553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaiser Family Foundation. Medicaid MCO enrollment by plan and parent firm, 2018. KFF. 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/medicaid-enrollment-by-mco/ Accessed November 3, 2020.

- 12.Kaiser Family Foundation. Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. KFF. 2020. Available at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/ Accessed November 3, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim C-Y, Wiznia DH, Hsiang WR, Pelker RR. The effect of insurance type on patient access to knee arthroplasty and revision under the Affordable Care Act. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1498-1501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laws M, Scott MK. The emergence of retail-based clinics in the United States: early observations. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:1293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merritt B, Naamon E, Morris SA. The influence of an urgent care center on the frequency of ED visits in an urban hospital setting. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:123-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montalbano A, Rodean J, Kangas J, Lee B, Hall M. Urgent care and emergency department visits in the pediatric Medicaid population. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153100-e20153100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.New York State Department of Health. Ambulatory services: urgent care policy options. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/facilities/public_health_and_health_planning_council/meetings/2013-09-13/docs/uc_policy_options.pdf. Accessed March 18, 2021.

- 18.Nguyen J, Anandasivam NS, Cooperman D, Pelker R, Wiznia DH. Does Medicaid insurance provide sufficient access to pediatric orthopedic care under the Affordable Care Act? Glob Pediatr Health. 2019;6:2333794X1983129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rao MB, Lerro C, Gross CP. The shortage of on-call surgical specialist coverage: a national survey of emergency department directors. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:1374-1382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Solv Health. Urgent Care near me. Available at: https://www.solvhealth.com/urgent-care. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 21.Thygeson M, Van Vorst KA, Maciosek MV, Solberg L. Use and costs of care in retail clinics versus traditional care sites. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:1283-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tolbert J, Nov 06 ADP, 2020. Key facts about the uninsured population. Available at: https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/ Accessed March 18, 2021.

- 23.Urgent Care Association. Urgent care industry white paper: the essential role of the urgent care center in population health. Available at: ucaoa.org. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 24.Urgent Care Association. Find an urgent care center near me. Available at: https://www.ucaoa.org/Resources/Find-an-Urgent-Care. Accessed June 1, 2019.

- 25.Weinick RM, Bristol SJ, DesRoches CM. Urgent care centers in the U.S.: findings from a national survey. BMC Health Serv Res. Published online May 15, 2009. DOI: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wiznia DH, Schneble CA, O’Connor MI, Ibrahim SA. Musculoskeletal urgent care centers in Connecticut restrict patients with Medicaid insurance based on policy and location. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1443-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiznia DH, Wang M, Kim C-Y, Leslie MP. The effect of insurance type on patient access to ankle fracture care under the Affordable Care Act. Am J Orthop. 2018;47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]