Abstract

In the agricultural setting, core global food safety elements, such as hand hygiene and worker furlough, should reduce the risk of norovirus contamination on fresh produce. However, the effect of these practices has not been characterized. Using a quantitative microbial risk model, we evaluated the individual and combined effect of farm-based hand hygiene and worker furlough practices on the maximum risk of norovirus infection from three produce commodities (open leaf lettuce, vine tomatoes, and raspberries). Specifically, we tested two scenarios where a harvester’s and packer’s norovirus infection status was: 1) assumed positive; or 2) assigned based on community norovirus prevalence estimates.

In the first scenario with a norovirus-positive harvester and packer, none of the individual interventions modeled reduced produce contamination to below the norovirus infectious dose. However, combined interventions, particularly high handwashing compliance (100%) and efficacy (6 log10 virus removal achieved using soap and water for 30 seconds), reduced produce contamination to <1–82 residual virus. Translating produce contamination to maximum consumer infection risk, 100% handwashing with a 5 log10 virus removal was necessary to achieve an infection risk below the threshold of 0.032 infections per consumption event.

When community-based norovirus prevalence estimates were applied to the harvester and packer, the single interventions of 100% handwashing with 3 log10 virus removal (average 0.02 infection risk per consumption event) or furlough of the packer (average 0.03 infection risk per consumption event) reduced maximum infection risk to below the 0.032 threshold for all commodities. Bundled interventions (worker furlough, 100% glove compliance, and 100% handwashing with 1-log10 virus reduction) resulted in a maximum risk of 0.02 per consumption event across all commodities. These results advance the evidence-base for global produce safety standards as effective norovirus contamination and risk mitigation strategies.

Keywords: hand hygiene, foodborne illness, quantitative microbial risk model, produce microbial safety

1. Introduction

Human norovirus is the leading cause of foodborne disease, with an estimated 125 million (95% UI: 70 – 251 million) cases annually worldwide (Kirk et al., 2015; Pires et al., 2015). In the European Union (2004–2012) (Callejon et al., 2015) and the United States (1998–2013) (Bennett et al., 2018), norovirus was the primary etiological agent among reported produce-associated outbreaks (53–54%). Frequently implicated fresh produce commodities associated with norovirus outbreaks include lettuce (Ethelberg et al., 2010; Mesquita and Nascimento, 2009; Muller et al., 2016), tomato (Zomer et al., 2010), and raspberries (Chatziprodromidou et al., 2018; Le Guyader et al., 2004; Maunula et al., 2009; Sarvikivi et al., 2012). Despite the risk to consumers, there is no clear guidance on effective measures to protect fresh produce consumers from norovirus illness. Moreover, preventing contamination of fresh produce with norovirus is imperative given the extremely low infectious dose (ID50: 18 virus particles) (Teunis et al., 2008), high environmental persistence and stability (Cannon et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2009; Seitz et al., 2011), and lack of lethal processing steps prior to consumption.

Norovirus has been occasionally detected on produce along the farm-to-fork supply chain (Felix- Valenzuela et al., 2012; Maunula et al., 2013; Stals et al., 2011; Van Pelt et al., 2018), with contamination likely occurring through several exposure pathways. While numerous studies have investigated the norovirus infection risks attributed to contaminated irrigation water (Chandrasekaran and Jiang, 2018; Lim et al., 2015; Troldborg et al., 2017) and wastewater reclamation (Barker, 2014; Mara and Sleigh, 2010; Mok et al., 2014; Silverman et al., 2013), the contribution of infected farmworkers to norovirus contamination of food is unclear. Epidemiological studies suggest that direct contact by norovirus-infected food workers (e.g. bare-handed contact by an ill food worker, improper hand hygiene) (Bennett et al., 2018; Moe, 2009; Todd et al., 2007) represents a critical norovirus transmission pathway along the produce supply chain, usually occurring during food preparation (Todd et al., 2007). However, fresh produce intended for direct consumption is frequently harvested and processed by hand without processing steps that would eliminate the pathogen. Researchers have detected norovirus RNA on farmworker hands and gloves, suggesting farmworker hands may be involved in virus transmission (Huvarova et al., 2018; Kokkinos et al., 2012; Leon-Felix et al., 2010).

There are limited studies evaluating farmworker health and hygiene strategies to reduce norovirus contamination in the farm environment. Bouwknegt et al., (2015), evaluated the impact of handwashing on norovirus and hepatitis A virus levels along leafy green vegetable and berry fruit supply chains. This study identified hand transfers to be the dominant contamination source for lettuce (infection risk of 3 × 10−4 per 200g romaine lettuce consumed), rather than irrigation water, the conveyor belt, or final wash water. Jacxsens et al., (2017), explored the impact of handwashing and hand disinfection on transmission of norovirus during pre-harvest, harvest, and processing of raspberry fruits, which resulted in an estimated 1.9 log10 reduction in virus on 11 tons of the daily raspberry production. Verhaelen et al., (2013), simulated the amount of norovirus transferred per tactile event of a food handler sequentially picking raspberries with contaminated gloved fingertips (varying virus transfer efficiencies), which resulted in an estimated 20–125 infections from consumption of the norovirus-contaminated raspberries. However, these studies were limited to leafy green vegetables or berries and did not assess the combined effect of multiple hand hygiene behaviors (i.e. handwashing and glove use), nor a higher range of handwashing efficacy (Tuladhar, 2015), both of which are included in the US Food Safety Modernization Act Produce Rule (FSMA) (FDA, 2015) and other global fresh produce safety standards (FAO, 2017) and guidelines (FAO, 2012b).

Hand hygiene and worker furlough have been demonstrated as effective strategies to disrupt norovirus transmission during foodborne outbreaks (Bhatta et al., 2019) and in the retail food setting. During food preparation, Mokhtari and Jaykus, (2009), predicted that simultaneous gloving and handwashing compliance were most effective in controlling norovirus contamination of food products. Similarly, worker furlough in a retail food setting until 24 hours after symptom resolution resulted in a 75% reduction in the number of norovirus infections among consumers relative to the baseline model (Duret et al., 2017). While these mathematical modeling studies and others (Grove et al., 2015; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2019; Ronnqvist et al., 2014; Stals et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2019) support the efficacy of hand hygiene and worker furlough in the retail food setting, their application to the farm harvest and production environment has been somewhat limited.

To address these needs, in this study, we evaluated the individual and combined effect of farm-based hand hygiene and worker furlough practices on maximum consumer norovirus infection risk from three at-risk food commodities (lettuce, tomato, and raspberries). This work advances the evidence-base for global produce safety standards (FAO, 2012b, 2017) as effective norovirus contamination control and risk mitigation strategies.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Overview of the model.

Model conceptualization was informed by prior fresh produce field studies conducted in the southern United States and northern Mexican border states (Ailes et al., 2008; Johnston et al., 2005; Johnston et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2017). We also applied similar model structure (contamination of workers’ hands, transfer efficiencies, hand hygiene interventions etc.,) as used by Mokhtari and Jaykus, (2009) in a retail food setting.

2.2. Model Structure.

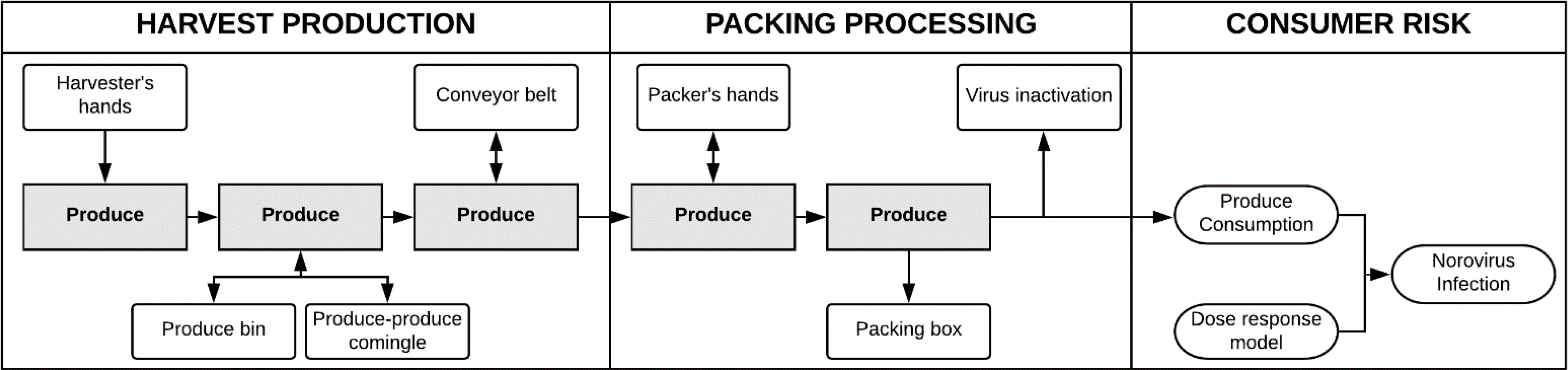

The model outcomes were two-fold: estimating the amount of norovirus contamination on produce items and the maximum consumer risk of norovirus infection. The commodities evaluated in this model included: red raspberries, vine-ripened tomatoes, and open leaf lettuces including red leaf, green leaf, and romaine. The degree of contamination was expressed as total infectious virus particles remaining on the final packed produce item that was contacted (first tactile event(s)) by the norovirus-contaminated hands of the infected harvester and/or packer. Maximum consumer risk of norovirus infection was defined as the risk after consumption of the average daily serving amount of this final packed product. The conceptual model (Figure 1) is comprised of three phases. The first phase is produce harvesting in the field (harvest phase), the second phase is post-harvest processing in the packing facility (packing phase), and the third phase is estimation of maximum consumer infection risk. In the model, two workers, a harvester and a packer, who are independent of one another, handle produce items during a single work shift. Both workers are assumed to contact the lettuce and tomato commodities, whereas only the harvester is assumed to contact the raspberries. With a fixed, sequential workflow, produce items pass through the model from the harvest phase to the packing phase as follows: 1) produce is harvested by hand in the field by the harvester (first tactile event) and placed in a re-usable harvest bin (for raspberries this is a clamshell); 2) produce in the harvest bin comingles with other produce items (produce-to-produce tactile events) and contact the bin interior (produce-to-bin tactile events); 3) produce is transferred via emptying of the bin onto a conveyor belt (produce-to-belt tactile events; not simulated for raspberries) for transport to the packing facility; and 4) in the packing facility produce items are transferred by hand by the packer (final tactile event) from the conveyor belt to a large final packing box (not simulated for raspberries). Please refer to Appendix A for additional details on model vetting by produce industry experts.

Figure 1. Full conceptual model.

Conceptual norovirus risk model applied to farms and packing facilities. This model depicts the three discrete modeling phases used in this study, as indicated by the large boxes representing Production-Harvest, Packing-Processing, and Consumer Risk, following fresh produce consumption. Produce commodities pass through the model starting in the Production-Harvest phase with a single direct hand contact by a harvester, followed by transfer to produce bins, contact with other produce (comingling), and transfer to a conveyor belt. From the conveyor belt, produce transitions into the Packing-Processing phase with a single direct hand contact by the packer during transfer from the conveyor belt to a final produce box. While the lettuce and tomato commodities followed this sequence of events, raspberries were contacted only by the harvester followed by placement into a clamshell. Virus decay occurs during a holding period prior to produce distribution and consumption. In the Consumer Risk phase, norovirus infection risk characterization integrates exposure assessment using US EPA commodity-specific consumption rates with a fractional Poisson norovirus dose response model. In this model, maximum infection risk represents the risk from consumption of the final packed product associated with the first tactile event, rather than risk associated with diffuse contamination across an entire produce lot. Boxes represent discrete steps and shaded boxes represent produce within the Production-Harvest and Packing-Processing phases along the fresh produce supply chain. Circles in the Consumer Risk phase represent a transition from norovirus contamination events to risk assessment. Arrows represent norovirus transmission between compartments influenced by transfer efficiency and frequency of contacts. Single and bidirectional arrows indicate contamination pathways, with norovirus assumed to transfer from highest to lowest concentration.

The model was used to evaluate two scenarios where a harvester’s and packer’s norovirus infection status was: 1) positive; or 2) assigned to community-based norovirus prevalence estimates of asymptomatic norovirus disease where the harvester and packer each had a 4% likelihood of infection (Qi et al., 2018) and, otherwise, were assumed to be uninfected. Asymptomatic norovirus disease estimates were selected as a proxy to represent acutely infected individuals without clinical symptoms or newly returned workers following symptom resolution with extended or persistent virus shedding. Community estimates of symptomatic norovirus disease were not included as ill individuals should be excluded from contact with produce or produce-contact surfaces (FAO, 2017; FDA, 2015). The model was developed in R (version 3.4.2; R Development Core Team; Vienna, Austria) using the mc2d package for Monte Carlo simulation (Pouillot and Delignette-Muller, 2010). For each simulation, 10,000 iterations were run, with each iteration representing the first ten produce items consecutively harvested and packed using model parameters selected from defined probability distributions or assigned values (Table 1).

Table 1.

Parameters, values, and probability distributions used in the QMRA models.

| Variable Notation | Definition [units] | Distribution and/or Values | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Inputs associated with norovirus viral load and contamination of hands by fecal matter | |||

| conc/concp | Concentration of norovirus in stool – harvester and packer [virions/gram] | 10BetaPert (2,6,11); min: 100, mode: 1,000,000, max: 100,000,000,000 (shape = 10) | (Atmar et al., 2014; Kirby et al., 2014; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009) |

| mfh/mfhp | Mass of feces/hand—harvester and packer [grams/hand] | Generalized beta: shape1: 4.57, shape2: 2.55, min: −8.00, max: −1.00 | (Bouwknegt et al., 2015) |

| Inputs associated with farmworker health and hygiene behavior (handwashing compliance and efficacy, glove use) | |||

| hweff/hweffp | Handwashing removal efficacy— harvester and packer [log10 virions] | Triangle (0.0, 0.5, 6) | (Doultree et al., 1999; Duizer et al., 2004; Grove et al., 2015; Kampf et al., 2005; Kramer et al., 2006; Lages et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2010; Macinga et al., 2008; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009; Sattar, 2002; Tuladhar, 2015) |

| Phhw/Pphw | Probability of handwashing— harvester and packer [%] | Empirical (0.27,0.73) | (Green et al., 2006) |

| Phwg/Ppwg | Probability of using gloves— harvester and packer [%] | Empirical (0.25,0.75) | (Emery, 1990; FDA, 2000; Green et al., 2006; Michaels and Ayers, 2002; Michaels et al., 2004; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009) |

| prev | Community-based asymptomatic norovirus prevalence among adults — harvester and packer [%] | Empirical (0.04,0.96) | (Qi et al., 2018) |

| Inputs associated with tactile contacts during harvesting and packing | |||

| Trhhp/Trphp | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from bare hands to produce— harvester and packer: | ||

| Lettuce | Uniform (0.123, 0.237) | (Bidawid et al., 2004) | |

| Tomato | Log Normal: mean log: −2.22, SD log: −0.17 | (Tuladhar et al., 2013) | |

| Raspberry | Log Normal: mean log: −2.32, SD log: −0.15 | (Bouwknegt et al., 2015) | |

| Trhgp/Trpgp | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from gloved hands to produce— harvester and packer | Beta, shape 1: 1.165, shape 2: 2.630 | (Barker et al., 2004; Bidawid et al., 2004; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009) |

| Trpph | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from produce to bare hands— packer only: | (Bidawid et al., 2004; Bouwknegt et al., 2015; Verhaelen et al., 2013) | |

| Lettuce | Uniform (0.105, 0.175) | ||

| Tomato | Uniform (0.105, 0.175) | ||

| Raspberry | Beta, shape 1: 7.42, shape 2: 39.51 | ||

| Trhpbi | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from produce to bin | Triangle (0.009,0.028, 0.038) | (D’Souza et al., 2006; Escudero et al., 2012; Stals, 2013; Stals et al., 2015) |

| Trppbe | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from packing produce to belt | Triangle (0.009,0.028, 0.038) | (D’Souza et al., 2006; Escudero et al., 2012; Stals, 2013; Stals et al., 2015) |

| Trhhg/Trphg | Proportion of norovirus transfer per touch from contaminated bare hand /restroom environment to glove— harvester and packer | Uniform (0,0.444) | (Ronnqvist et al., 2014) |

| Trhppbi | Proportion of produce to produce norovirus transfer per contact in harvest bin | Beta, shape 1: 2.257, shape 2: 15.502 | (Barker et al., 2004; Bidawid et al., 2004; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009) |

| nhPh/npPh | Number of hand-to-produce contacts—harvester and packer | Empirical (1), p(1) | Assumption |

| nPbi | Number of produce-bin contacts | Empirical (1–5), p(0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2) | Assumption |

| nPbe | Number of produce-belt contacts | Empirical (1–5), p(0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2,0.2) | Assumption |

| nPPbi | Number of produce-to-produce contacts in bin | Empirical (1–10), p(0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1, 0.1) | Assumption |

| norodecay | Norovirus log10 reduction per day at: Lettuce: 5°C Tomato, raspberry: 20°C |

Point (0.011) Point (0.151) |

(Bouwknegt et al., 2015) |

| Inputs associated with dose-response, exposure assessment, and risk characterization for the consumer | |||

| μ | Mean aggregate size | Triangle (399, 1106, 2428) | (Messner et al., 2014) |

| P | Dose-response: probability of infection among susceptible subjects | Triangle (0.63, 0.722, 0.8) | (Messner et al., 2014) |

| bodyweight | Adult body weight [kilograms] | Point (80) | (EPA, 2011) |

| weightlettucehead | Reported weight per single raw lettuce head (representing red leaf, green leaf, and romaine lettuces) [grams] | Triangle (309, 360, 626) | (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2019) |

| weighttomato | Reported weight per single tomato [grams] | Triangle (91, 123, 182) | (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2019) |

| weightberry | Reported weight per single raspberry [grams] | Triangle (3, 4, 5) | (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2019) |

| lettuceconsumpt | Consumer-Only 2-Day average intake of lettuce, whole population [g/kg-day] | Normal 0.44, SD: 0.01 | (EPA., 2018) |

| tomatoconsumpt | Consumer-Only 2-Day average intake of tomatoes, whole population [g/kg-day] | Normal 0.83, SD: 0.02 | (EPA., 2018) |

| berryconsumpt | Consumer-Only 2-Day average intake of berries, whole population [g/kg-day] | Normal 0.45, SD: 0.02 | (EPA., 2018) |

2.3. Data sources.

Model parameters (Table 1) were grouped into four categories: (i) norovirus shedding and amount of fecal contamination on hands; (ii) farm-worker health and norovirus-control measures (i.e. hand hygiene, furlough); (iii) tactile contacts and transfer efficiencies of virus between fomite surfaces (resulting in virus dilution); and (iv) dose-response, infectious-dose, and maximum consumer-risk characterization. Norovirus infection and virus shedding data were obtained from challenge studies in which symptomatic individuals shed norovirus ranging from 2 to 11 log10 viral genome copies per gram of feces (Atmar et al., 2014; Kirby et al., 2014; Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009). Data from laboratory studies on the persistence and transfer of noroviruses between hands and fomites (i.e. surfaces, foods) were applied to this agriculture model setting. Please refer to Appendix A for additional details on the model sequential tactile events, data sources, and assumptions.

2.4. Norovirus contamination of workers’ hands.

In this model, the primary source of produce contamination is from contact with norovirus-contaminated hands of the harvester and/or packer immediately following restroom use. Hands are assumed to become contaminated via contact with personal feces in the restroom, which is the most likely location for fecal events to occur (Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009), and is the single norovirus source in the model. Model estimates of norovirus contamination on worker’s hands were also calibrated against a single report quantifying GI.1 norovirus on hands among norovirus infected challenge study volunteers which found an average of 3.86 log10 genomic equivalent copies (GEC) per hand (Liu et al., 2013). One restroom event was simulated for each worker based on prior fieldwork observations (Ailes et al., 2008; Johnston et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2017) in which workers were compensated by produce volume harvested and not time, which incentivized taking fewer breaks and restroom visits. For the harvester/packer, the initial norovirus contamination on one hand, nvhH, is expressed as norovirus virions per one hand:

Here, mfh, represents the mass of feces per hand of the harvester and packer [grams/hand]. Conc, is the concentration of norovirus in stool [infectious virions/gram], hweff is the handwashing removal efficacy [log10 virions], and Phhw is the probability of handwashing (handwashing compliance). Handwashing was assumed to be with soap and water for 30 seconds and was considered independently for each worker. How well the workers washed their hands (handwashing efficacy) was derived from laboratory studies on norovirus removal from hands (Liu et al., 2010; Tuladhar, 2015). Glove use sequentially followed handwashing and was defined as the probability of a worker using gloves. In this model, all hand hygiene practices were assumed to occur one time immediately following restroom use. Repeat handwashing, glove changes, and sanitizing of gloves were not simulated. Norovirus contamination on the gloves of the harvester, nvhG, transferred from contaminated hands to gloves during the gloving process, (Ronnqvist et al., 2014), was modeled independently for each worker and calculated using Trhhg, the proportion of norovirus transferred per touch from a contaminated bare hand to a glove and Phwg, the probability of using gloves.

2.5. Produce contamination during harvest.

Initial produce contamination occurs in the harvest phase when produce items are picked by hand by the harvester. Norovirus contamination of produce after harvest, nvhP1 was defined as the proportion of total virus transfer from a bare or gloved hand to produce during harvesting per contact using Trhgp, the virus transfer efficiency from a gloved hand or Trhhp, the virus transfer efficiency from a bare hand, per one touch to produce, nhPh.

For raspberries, instead of the palm of the harvester’s hand (245 cm2) contacting the berry, this surface area was scaled by a point estimate of 2.1 cm2 representing the surface area of three fingers (Bouwknegt et al., 2015; Verhaelen et al., 2013). Following harvesting, produce is placed in a harvest bin, leading to virus transfer between the produce and bin (for raspberries this is in a clamshell). The norovirus concentration on produce following bin contact, nvhP2, was calculated as the proportion of total virus transfer from bin to produce during harvesting per contact using Trhpbi, the virus transfer efficiency from bin to produce, per bin contact with produce, nPbi:

Produce comingling within the harvest bin allows for transfer of virus between produce items along a concentration gradient. Using Trhppbi, the virus transfer efficiency between produce-to-produce items and the number of produce to produce contacts, nPPbi, we simulated the norovirus contamination, nvhP3, after produce comingling in the harvest bin:

Following the harvest bin, lettuce and tomato commodities are emptied onto a conveyor belt where produce to belt contacts occur without produce comingling. For raspberries, this step was not simulated and instead, the berries remained in their clamshell. Norovirus contamination on produce after the conveyor belt contact, nvpP1, was calculated using Trppbe, the virus transfer efficiency between produce and the belt and, nPbe, the number of produce to belt contacts.

2.6. Produce contamination during packing.

Contamination of lettuce and tomato commodities can also occur in the packing phase as they enter via the conveyor belt and are transferred by hand (one contact) by the packer to a final produce box. This was not simulated for raspberries as it was assumed no additional repackaging/handling would occur after placement in the clamshell by the harvester. Similar to produce handling by the harvester, produce contamination after packing by hand, nvpP2, was calculated from a bare or gloved hand to produce using Trpgp, the virus transfer efficiency from a gloved hand or Trpph, the virus transfer efficiency from a bare hand, per one touch to produce, npPh:

No produce comingling or produce washing/intentional virus removal processes were considered in the final packed produce step. Further, alternate contamination pathways such as from irrigation water, soil, and via root uptake were outside the scope of this study.

2.6. Risk Assessment.

The norovirus ingested dose was calculated using the virus particles on the packed product, nvpP2, after accounting for virus decay during short holding periods prior to consumption. For tomatoes, norodecay, represented virus log reduction per day at 22°C for 7 days, whereas for raspberries and lettuce, this was virus log reduction per day at 5°C for 7 days (Bouwknegt et al., 2015; Verhaelen et al., 2012). The amount of virus contamination following virus decay on the packed product was calculated as follows:

Using lettuce as an example, the total norovirus dose ingested, doselettuce, expressed in units of total infectious viral particles was:

Here, the multiplication of bodyweight (EPA-reported average bodyweight for adults [kg] (EPA, 2011)) with lettueconsump (EPA Exposure Handbook commodity-specific daily consumption rate for adults of lettuce [g/kg-day] (EPA., 2018)) represented national adult consumption patterns. Here, nvpP2decay was the total norovirus contamination of lettuce following virus decay (Bouwknegt et al., 2015); and weightlettucehead was weight in grams per head of lettuce (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2019). Norovirus dose was calculated for the tomato and raspberry commodities using commodity-specific consumption (EPA., 2018) and weight data (U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 2019). The fractional Poisson dose-response model for human noroviruses (Messner et al., 2014) was used to model the infection endpoint following exposure to varying norovirus doses. This risk characterization by infection rather than illness is consistent with the norovirus QMRA literature (Teunis et al., 2008; Van Abel et al., 2017). Maximum norovirus infection risk was characterized as the probability of infection resulting from ingestion of the daily serving size of each contaminated produce item.

2.7. Sensitivity analysis.

A stochastic sensitivity analysis was conducted to determine the most influential and relevant determinants of norovirus contamination on produce items and of consumer risk from produce consumption (Zwietering and van Gerwen, 2000). Spearman rank correlation coefficients were used to rank the correlation between the norovirus produce contamination levels or consumer risk and parameter values using the tornado function within the mc2d package in R. We also applied built-in functions in the mc2d R-package including “tornadounc” (tornado of uncertainty) and “mcratio” (measures of variability, uncertainty, and both combined for model parameters) in order to examine the impact and propagation of uncertainty within the model on the virus contamination and consumer infection risk estimates.

2.8. Intervention impact testing.

Scenarios were selected that are potentially modifiable food safety practices and are included in global produce safety guidelines (FAO, 2012a; FDA, 2015): handwashing with soap and water (compliance ranging from 0–100%; efficacy ranging from 0–6 log10 virus removal); glove use (disposable gloves donned once); and furlough of symptomatic, infected workers (either the harvester or the packer). The handwashing efficacy of 6 log10 virus removal was selected as this is the highest reduction reported from empirical handwashing studies with human norovirus (Tuladhar, 2015). We assumed baseline interventions for handwashing were 27% compliant (Green et al., 2006) with 2 log10 removal efficacy (Liu et al., 2010) and glove use 25% (Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009). For each scenario, the median concentration of infectious virus particles on the produce item were simulated with the log reduction in virus contamination reported relative to no intervention. “Acceptable” thresholds included a contamination amount less than 18 infectious norovirus particles per commodity, which is equivalent to the ID50 and which has been previously used as a dose cut-off (Mokhtari and Jaykus, 2009; Teunis et al., 2008; Trujillo et al., 2006). For consumer risk, an “acceptable” threshold was an infection risk of 0.032 per consumption event which is the threshold from EPA surface water quality monitoring for viral and fecal indicators (Boehm, 2019; EPA, 2012).

3. Results

3.1. Norovirus contamination on fresh produce with two norovirus-positive infection status workers

In the first scenario where both the harvester and packer were norovirus-positive and assuming baseline hand hygiene (refer to Methods), the median virus concentration on the final packed product was elevated: lettuce (7.69, 95% CI: [7.68, 7.71] log10 virus), tomato (7.48, 95% CI: [7.47, 7.50] log10 virus) and raspberry (4.91, 95% CI: [4.89, 4.93] log10 virus). We also observed, between the first and tenth packed product, a modest attenuation (dilution effect) across all commodities: raspberries (0.37 log reduction), tomato (0.43 log reduction), and lettuce (0.74 log reduction) (Supplemental Material Appendix A, Figure 1).

3.1.1. Relative contribution of each norovirus-infected worker to lettuce and tomato contamination

Following this first scenario involving both an infected harvester and packer, we investigated the relative contribution of each worker to norovirus contamination of the lettuce and tomato commodities. Raspberries were excluded from this analysis as they were not contacted by the packer. We consistently found across both commodities that when the packer was infected, this accounted for approximately 70% of the total norovirus concentration on the commodity and the consumed dose relative to when both workers are infected (Supplemental Material Appendix A).

3.1.2. Impact of individual interventions on commodity contamination with two norovirus-infected workers

Investigating the impact of individual interventions on norovirus contamination with two norovirus-infected workers, we found gloving resulted in only modest reductions in norovirus contamination across all commodities (Supplemental Material Appendix A, Figure 2A); ranging from harvester-only wearing gloves (average 0.11 log10 reduction per item) to both harvester and packer wearing gloves (0.26 log10 reduction). For handwashing (2 log10 virus removal efficacy), sequentially higher reductions in virus concentration were found from full compliance (100%) with packer-only handwashing (lettuce and tomato commodities average 0.48 log10 virus reduction), harvester-only handwashing (across all commodities average 0.78 log10 virus reduction), and both harvester and packer handwashing (across all commodities average 2 log10 reduction), compared to no handwashing (Supplemental Material Appendix A, Figure 2B). For lettuce and tomato commodities, furlough of the symptomatic, infected harvester (average 0.17 log10 reduction) had less of an impact on contamination than did furlough of the packer (0.56 log10 reduction) (Supplemental Material Appendix A, Figure 2C). As raspberries were only contacted by the harvester, furlough of the harvester resulted in no viral contamination and furlough of the packer resulted in no protective effect. In the context of two norovirus-infected workers, across all commodities, the individual interventions modeled did not reduce produce contamination to below the norovirus infectious dose.

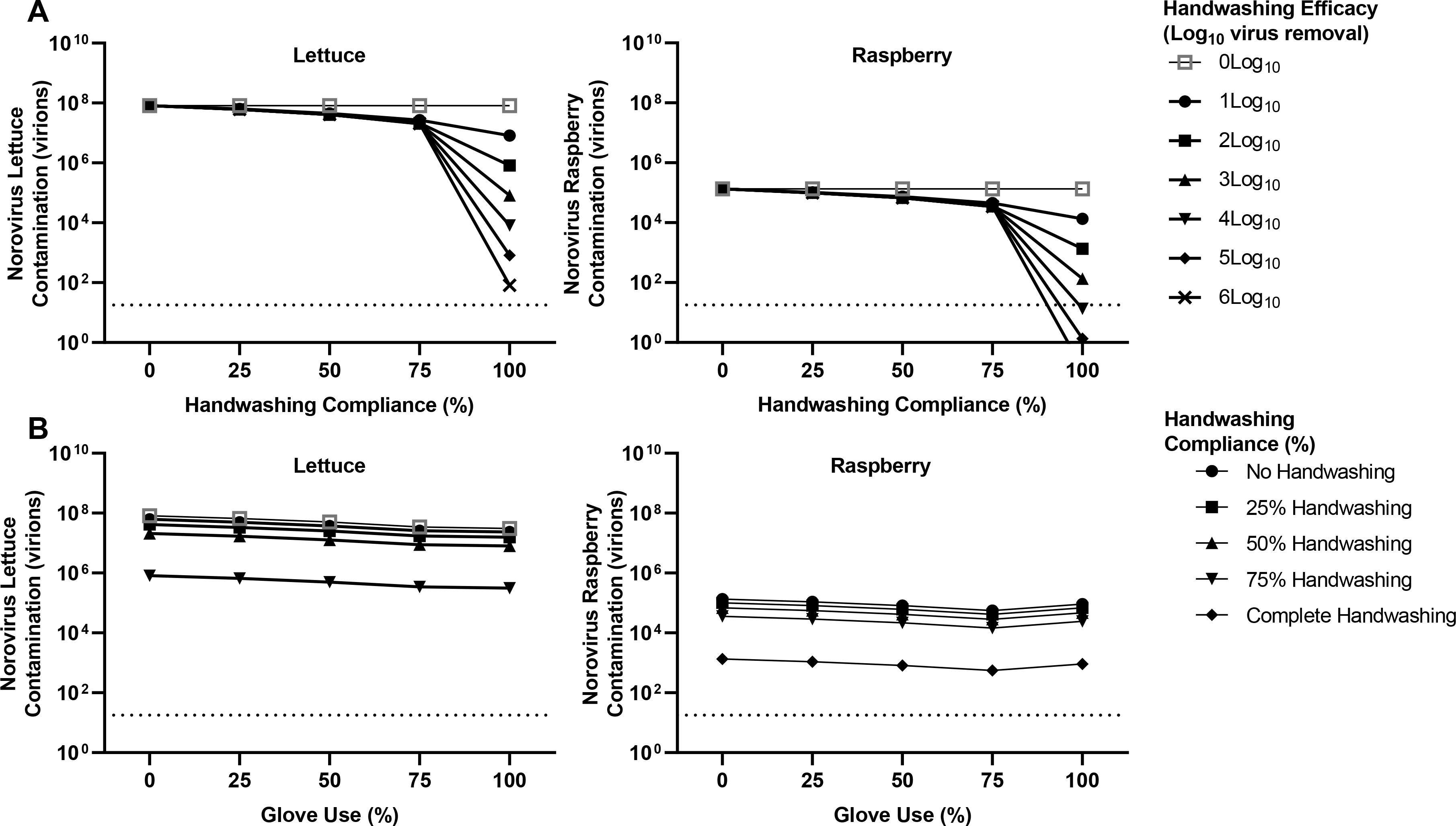

3.1.3. Impact of combined interventions on norovirus contamination with two infected workers

We next evaluated the ability of combined interventions, for instance increasing handwashing compliance and handwashing efficacy, to enhance reductions in produce contamination when two norovirus-infected workers are present (Figure 2A, Supplemental Figure 3A, Supplemental Material Appendix A). Increasing handwashing compliance to 100% and handwashing efficacy to 6 log10 virus removal resulted in a synergistic effect on contaminant concentration in the first harvested tomato (50.1, 95% CI: [48.8, 51.6] residual virus particles), lettuce (81.9, 95% CI: [80.0, 84.2] residual virus particles), and raspberries (0.14, 95% CI: [0.13, 0.14] residual virus particles).

Figure 2.

Impact of combined hand hygiene interventions (handwashing compliance, handwashing efficacy, and glove use compliance) on norovirus concentration in two fresh produce commodities (lettuce, raspberry). For lettuce, contamination represents a single focal contamination event resulting from direct tactile contact with two norovirus-positive food handler. Raspberries are contacted only by the norovirus-infected harvester and placed in a clamshell with no repackaging or contact with the norovirus-infected packer. The horizontal reference line represents the lower range of the estimated norovirus infectious dose of 18 virus particles (Teunis et al., 2008). (A) Joint effects of handwashing compliance and handwashing efficacy (in the absence of glove use) on norovirus contamination (estimated total virus particles) of the first raspberry and lettuce commodities handled by the food worker(s). (B) Joint effects of glove usage compliance and handwashing compliance (with handwashing efficacy set at 2 log10 virus removal) on norovirus contamination (estimated total virus particles) of the first lettuce and raspberry commodities handled by the food worker(s). For all figures, error bars represent 95% credible intervals.

The combined effect of 100% glove use paired with 100% handwashing compliance (2 log10 viral removal efficacy) (Figure 2B, Supplemental Figure 3B, Supplemental Material Appendix A) resulted in an average 2.26 log10 virus reduction in norovirus contamination across all commodities. However, following this combined intervention, residual norovirus contamination still remained: 2.97 95% CI: [2.94, 2.99] log10 (raspberries) and 5.49 95% CI: [5.47, 5.51] log10 (tomato and lettuce). Full gloving compliance combined with furlough of the symptomatic, infected packer resulted in only modest log10 reductions relative to no intervention: 0.86 log10 virus reduction (tomato) and 1.07 log10 virus reduction (lettuce). For the tomato and lettuce commodities, 100% handwashing compliance (2 log10 virus removal) combined with furlough of the symptomatic, infected packer resulted in larger contamination reductions (average 2.56 log10 reduction), relative to no intervention. However, for both of these combined interventions, residual contamination remained above the norovirus infectious dose (Supplemental Material Appendix A).

Rank prioritization of these combined interventions in the context of a norovirus-infected harvester and packer, suggests that complete handwashing compliance with high handwashing efficacy (6 log10 virus removal) was superior to any dual combinations of glove use, furlough of the symptomatic, infected worker, and handwashing compliance with a modest handwashing efficacy (2 log10 virus removal). Among worker furlough interventions, in general, packer furlough with 100% handwashing compliance (2 log10 virus removal) was superior to 100% handwashing (2 log10 virus removal) with 100% glove compliance and the worst performing intervention was packer furlough with 100% glove compliance.

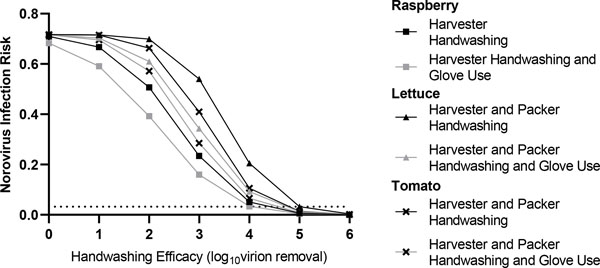

3.1.4. Impact of combined interventions on maximum consumer risk with two infected workers

Using the first model scenario with two infected workers, we estimated the maximum norovirus infection risk to consumers ingesting the norovirus-contaminated commodities. In the absence of hand hygiene interventions, there was an elevated average maximum norovirus infection risk of 0.714 per consumption of any of the commodities (raspberry, tomato, and lettuce commodities) (Figure 3). To achieve an infection risk below the risk threshold of 0.032, it was necessary to combine complete handwashing compliance and a handwashing efficacy of at least 5 log10 virus removal efficacy: (raspberries: 6.13 × 10−3, 95% CI [5.92 × 10−3, 6.44 × 10−3]; tomato: 1.34 × 10−2, 95% CI [1.30 × 10−2, 1.37 × 10−2]; and lettuce: 3.23 × 10−2, 95% CI [3.15 × 10−2, 3.31 × 10−2]). Layering on 100% glove compliance with 100% handwashing compliance did not serve to reduce the handwashing efficacy necessary to reach below the 0.032 risk threshold for the raspberry, tomato, and lettuce commodities.

Figure 3.

Contribution of hand hygiene interventions (handwashing compliance, handwashing efficacy, and glove use compliance) interventions, using the first model scenario with two norovirus-infected workers, on maximum consumer norovirus infection risk, defined as the risk of infection to the one individual consuming the daily serving amount of the final packed product. For raspberries, only the infected harvester contacted the fruit, therefore hand hygiene interventions were targeted to the harvester only. Complete glove use was defined as 100% glove use compliance for both the harvester and packer. Complete handwashing was defined as 100% handwashing compliance for both the harvester and packer.

Maximum consumer risk per consumption event across lettuce and tomato commodities remained above the risk threshold (0.032 infections per consumption event) for the combined interventions of 100% gloving compliance and furlough of the symptomatic, infected packer, with an average risk of 0.68. For lettuce and tomato, complete handwashing with a 5 log10 virus removal efficacy paired with furlough of the packer was sufficient to reduce consumer risk to below the threshold: lettuce 9.34 × 10−3, 95% CI [8.96 × 10−3, 9.77 × 10−3] and tomato 3.76 × 10−3, 95% CI [3.63 × 10−3, 3.93 × 10−3].

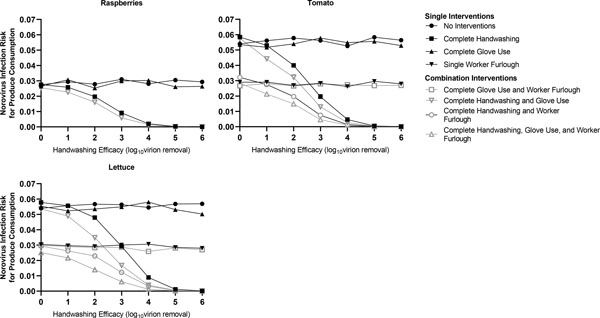

3.2. Harvester’s and packer’s infection status assigned to community-based norovirus prevalence

Our second model scenario simulated a more conservative norovirus infection in the agriculture harvest and packing environment. Specifically, in these simulations, both on-site workers were assigned estimates of community-based, asymptomatic norovirus prevalence (Qi et al., 2018), which represents plausible virus shedding in workers who: 1) are not aware they are sick (asymptomatic), and/or 2) continue to shed virus after symptom resolution. The same viral shedding titer distribution was applied in these analyses as was used in the first modeling scenario (Newman et al., 2016; Teunis et al., 2014).

Similar to the first scenario (both harvester and packer infected), using this community-based norovirus prevalence scenario, we evaluated the impact of individual and combined hand hygiene and worker furlough interventions on maximum consumer risk (Figure 4). As anticipated, when adjusting for this community norovirus prevalence, we observed a dramatic decrease in maximum consumer risk even in the absence of interventions: 0.054 95% CI [0.0536, 0.054] risk per consumption event of tomato or lettuce and 0.0275 95% CI [0.0273, 0.0276] risk per raspberry consumption event. Repeating this analysis with reduced viral shedding rates (2 to 6 log10 viral genome copies per gram of feces), that may be found with asymptomatic or post-symptom resolution infected individuals (Atmar et al., 2008; Sabria et al., 2016), resulted in maximum consumer risks less than 0.01 for all commodities, even in the absence of interventions (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Contribution of hand hygiene interventions and furlough of a symptomatically infected worker, using the community-based norovirus prevalence model scenario, on maximum consumer norovirus infection risk, defined as the risk of infection to the one individual consuming the final packed product associated with the first tactile event. In contrast to the first model scenario with two norovirus-infected workers, this second model scenario adjusts for a community-based norovirus prevalence estimate (4%) of asymptomatic norovirus infection among the harvester and packer workers. The same viral shedding titer distribution was applied to this scenario as was used in the first scenario with the two norovirus-infected workers. Single worker furlough was defined as the exclusion of the symptomatically infected packer with replacement by a healthy worker for the duration of the simulation. As this model assumes there are only two workers, the removal of one norovirus-infected worker represents partial (50%) worker furlough and does not fully eliminate the potential source of norovirus infection nor infection risk. Complete glove use was defined as 100% glove use compliance for both the harvester and packer. Complete handwashing was defined as 100% handwashing compliance for both the harvester and packer. For raspberries, only the harvester was in contact with the produce, resulting in no impact on consumer risk estimates by furlough of the packer.

Among individual interventions, furlough of the packer (average risk per lettuce or tomato consumption event: 0.029) and 100% handwashing compliance with at least a 3 log10 virus removal (average risk per consumption event: 0.019) effectively reduced maximum consumer risk for all commodities to below the 0.032 infection risk threshold. In contrast, 100% glove compliance alone was unable to reduce maximum infection risk to below the risk threshold across all commodities (average risk per consumption event: 0.045).

All bundled interventions effectively reduced maximum consumer risk to below the risk threshold. A handwashing efficacy of at least 3 log10 virus removal was necessary to reduce the maximum risk associated with lettuce consumption when combining 100% handwashing and 100% gloving compliance: lettuce 0.017 95% CI [0.016, 0.018]. At a handwashing efficacy of at least one log10 norovirus removal, notably, complete compliance with hand hygiene practices (handwashing and glove use) paired with the furlough of the packer had an enhanced risk reduction for tomato (0.021 95% CI [0.0204, 0.022]) and lettuce (0.022 95% CI [0.021, 0.022]). Complete compliance with all hand hygiene interventions and at least one log10 norovirus removal resulted in a raspberry risk of 0.023 95% CI [0.022, 0.024].

3.3. Sensitivity analyses

Spearman’s correlation coefficients were used to identify the most influential parameters for produce contamination. The parameters which contributed to more significant increases in norovirus contamination included the mass of feces on the packer’s (mfhp, rho=0.41) and harvester’s (mfh, rho=0.28) hands; and norovirus titer in stool for the packer (concp, rho=0.34) and harvester (conc, rho=0.23) (Supplemental Material Appendix A Figure 4). For maximum consumer risk, the single parameter with the greatest contribution was the probability of infection of either the harvester or packer (rho = 0.96). Notably, the parameters describing tactile events such as transfer efficiency and number of contacts generally had smaller effects (rho = −0.091 – 0.057) on the estimated norovirus concentrations. We also evaluated the propagation of parameter uncertainty and variability through the model, finding little correlation between these model inputs and uncertainty in the consumer risk outcomes (Supplemental Material Appendix A).

4. Discussion

In fresh produce production, core elements of global food safety such as hand hygiene and worker furlough should reduce norovirus contamination risk, but this has not been well characterized. The purpose of this work was to evaluate the individual and combined effect of farm-based hand hygiene and worker furlough practices on maximum consumer norovirus infection risk from three at-risk food commodities (lettuce, tomato, and raspberries). Using a stochastic quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) model, we tested two scenarios based on the infection status of one harvester and one packer: 1) both workers assumed norovirus-positive; or 2) worker infection status assigned based on community norovirus prevalence estimates. In the context of two norovirus positive workers, 100% handwashing compliance with a 5 log10 virus removal effectively reduced norovirus risk to consumers. Similarly, when applying community-based norovirus prevalence estimates to the harvester and packer, 100% handwashing with 3 log10 virus removal or bundled interventions (worker furlough, 100% glove compliance, and 100% handwashing with 1-log10 virus reduction) reduced risks across all commodities (<0.032 infections per consumption event). This work demonstrates that global produce safety standards, with a particular emphasis on handwashing, effectively control norovirus contamination and mitigate risks to consumers.

In this study, our model explicitly dealt with a single focal contamination event rather than diffuse contamination occurring from fecal-contaminated waters or soils (Chandrasekaran and Jiang, 2018; Troldborg et al., 2017), or else multiple contamination events (Maunula et al., 2013; Stals, 2015). In addition, maximum consumer risk was defined as the risk to the one individual who consumes the initial focally contaminated product, rather than risk associated with entire produce lots or scaled to population per-capita estimates. This approach differs from Verhaelen et al., (2013), who simulated the population-level impact of norovirus infections (20–125) resulting from sequential tactile events of 1,000 raspberries by a norovirus-infected food handler. Similarly, our model is distinct from Jacxsens et al., (2017), who simulated norovirus contamination across 10 farms with up to 20 infected workers on 11 tons of daily raspberry production lots. Whereas Bouwknegt et al., (2015) examined the relative contribution of both diffuse contamination via irrigation water and direct contact with food worker hands, Bouwknegt et al., applied a rather similar approach to estimating infection risk per serving of lettuce (200g lettuce consumption event). However, their risk characterization was restricted to a single commodity. In this way, we conceptualize our approach to consumer risk as aligning with retail food and school settings in which focal contamination via an infected food handler is proximal to the consumption event (Duret et al., 2017; Perez-Rodriguez et al., 2019). Each QMRA approach has its own advantages and disadvantages, but differences can make it difficult to directly draw comparisons between study results. We make those comparisons when applicable.

A notable comparison between our study and that of Jacxsens et al., (2017) is the estimated raspberry contamination levels. Our raspberry contamination estimates were considerably higher (range: 4.5 to 5.1 log10 viral particles) than those of Jacxsens et al., (2017), who reported a mean of 5.6 log10 norovirus/11 tons (or 36.2 norovirus/kg) of raspberries. Differences in these norovirus concentrations can be attributed to Jacxsens et al., (2017) averaging viral contamination across a combined one-day batch of 11 tons of raspberries, likely serving as a dilution effect. In addition, the mean viral shedding among infected food handlers was 6.65 log10 norovirus/g stool, which is lower than the peak viral shedding simulated in our model of (6–11 log10 infectious virus particles). However, contamination levels of raspberries simulated in our model are consistent with norovirus quantified from fresh and frozen raspberries (2.5 to 5.0 log10 norovirus RNA/10g) (Stals et al., 2011). Regarding risk assessment, direct comparisons could not be drawn as Jacxsens et al., (2017) approximated risk by comparing the estimated number of viral particles on frozen berries or ready-to-eat frozen cake containing the contaminated raspberries to the norovirus ID50 threshold. Only 1% of raspberry packages (250g) were calculated to have a contamination higher than 18 virus particles and in the case of ready-to-eat raspberry cake, no portions exceeded the ID50. In contrast, our study applied an established norovirus dose-response relationship and estimated a 3% infection risk from consumption of contaminated raspberries in our community norovirus prevalence scenario. Infection risk estimates in our study were most comparable to those reported by (Bouwknegt et al., 2015).

Our model simulations further advance the evidence-base for consistent handwashing practices (handwashing compliance and efficacy) as effective infection control strategies for norovirus contamination in the fresh produce production and packing environment. Specifically, 100% handwashing compliance with at least a 5 log10 viral removal (“harvester and packer both norovirus-positive” scenario) or at least a 3 log10 viral removal (“community-based norovirus prevalence” scenario) effectively reduced the norovirus infection risk to the consumer for all commodities. The simulated 3 log10 virus removal is readily achieved with washing hands for at least 20s with liquid or foaming soap as recommended by health and produce safety agencies (Grove et al., 2015). The consumer risk estimates from the community-based norovirus prevalence scenario on harvested and packed lettuce with 100% handwashing (5 log10 viral removal) (1.21 × 10−3 95% CI [1.06 × 10−3, 1.39 × 10−3] per lettuce consumption event) were within the range reported by (Bouwknegt et al., 2015), of 3 × 10−4 95% CI [6 × 10−6, 5 × 10−3] per lettuce consumption event. They are also largely consistent with Duret et al., (2017) and Perez-Rodriguez et al., (2019), who found handwashing compliance paired with increasing handwashing efficacy (1–3 log10 removal efficacy) reduced norovirus transmission in retail and school food service settings. While maintaining elevated hand hygiene compliance (current compliance estimates range from: 17% to 79%) remains a challenge in a variety of settings (Evans et al.; Fung and Cairncross; Lubran et al.; Surgeoner et al.), it is clear that effective handwashing practices applied at the appropriate time are a critical means by which to protect the fresh produce food supply from norovirus contamination.

In contrast to our findings on handwashing compliance, we found that 100% glove compliance alone was unable to reduce produce contamination or consumer risk to below the 0.032 infection risk threshold. These findings are consistent with Stals et al., (2015), who found that in the retail food setting, wearing and changing of gloves or using hand sanitizer were ineffective norovirus transmission intervention measures. Similarly, Duret et al., (2017), found that glove use alone did not decrease the risk of norovirus transmission. In fact, Duret et al., (2017) found 100% glove use and compliance with glove changing guidelines would increase the mean number of infected customers relative to the baseline scenario by 1.14-fold. Findings such as these can be attributed to cross-contamination events during glove use (Montville et al.; Ronnqvist et al., 2014). The ability of contaminated gloves to serve as viral vectors (Maitland et al., 2013; Todd et al., 2010; Verhaelen et al., 2013) underscores the importance, first and foremost, of consistent and thorough handwashing even in the presence of a gloving policy.

In the first model scenario (infected harvester and packer), we found that furlough of one symptomatically infected worker (partial worker furlough) resulted in only an average 1.2% reduction in risk for lettuce and tomato commodities. This finding is likely attributed to the peak viral titers (106-1011 infectious virus/gram feces) shed by a single infected worker, and the low virus infectious dose (ID50 18 virions). In short, one infected food worker being present is enough to result in elevated risk to the consumer ingesting the worker’s focally contaminated produce. Additional focal contamination events, or cross-contamination of comingled contaminated produce, would theoretically result in more contaminated product and elevated risk to more consumers, than that modeled. However, we did not assess these in our modeling approach. Using our community-based norovirus prevalence scenario, furlough of one worker resulted in risks below the 0.032 infection risk threshold. We would expect when translating these results to the real-world that this scenario would be analogous to a norovirus infected worker returning to work following symptom resolution who is then placed in areas without direct contact with food. Others have found higher risk reduction when using furlough as a management strategy. Duret et al., (2017) reported a 25% reduction in the mean number of infected consumers with full adherence to exclusion of employees during their symptomatic illness period and for 24-hours after symptoms resolve in the retail food setting. Using a population-based modeling approach, Yang et al., (2019), estimated greater than 40% reduction in norovirus cases per year with furlough of workers while symptomatic and for 2 days while post-symptomatic. It appears that furlough of ill workers is helpful in preventing downstream infection in consumers, however, the extent to which this is a significant public health protection measure depends upon the degree and nature of the contamination to the food commodity, and the modeling approach. It should be noted that our model, and those of others, did not explicitly evaluate risk after the return of infected food handlers to work following symptom resolution. Given the potential for extended viral shedding (Kirby et al., 2014), exploring the length of furlough is merited.

Not unexpectedly, the current study demonstrates that combined, as opposed to individual, interventions were more effective at mitigating consumer risk. Duret et al., (2017), found that handwashing frequency associated with gloving compliance reduced the mean number of infected customers to 62% of baseline in a retail food settings. Our study found higher reductions in consumer risk (average 99.9% risk reduction per consumption event), when employing higher handwashing efficacies with higher handwashing and glove use compliance combined. Our work also aligns with Mokhtari and Jaykus, (2009), who found that contamination control was most effective when two interventions were practiced simultaneously in a retail setting, such as gloving and handwashing compliance. In our community-based norovirus prevalence scenario, bundled interventions synergistically reduced consumer risk and alleviated the need for elevated handwashing efficacies. Given the biological factors of high viral titers and low infectious dose (Teunis et al., 2008), an intervention bundle comprised of multiple separate measures implemented simultaneously (handwashing frequently and often, glove use where appropriate) should be used to reduce norovirus transmission risks. This intervention bundle would help reduce the risk from norovirus-infected workers in the harvesting and packing phases, who are either asymptomatic (Okabayashi et al., 2008; Phillips et al., 2010) or who may shed virus before symptom onset (Rockx et al., 2002). Additionally, bundled interventions can serve as a “buffer” and reduce infection risks in the event that high levels of hand hygiene are unattainable for harvesters in the field due to time constraints and limited access to facilities.

Although it was not the primary purpose of our study, we found two modest attenuation, or dilution effects, in norovirus contamination of produce. The first dilution effect was observed following the initial tactile event between the product and harvester’s hand as the product underwent additional multiple tactile events (produce-to-bin, produce-to-produce, produce-to-conveyor belt). These multiple tactile events represented produce moving along the harvest and packing lines (dilution effect, average 0.4 log10 reduction across lettuce and tomato commodities, data not shown). The second dilution effect was observed between the first and tenth handled and packed produce commodity, (between 0.4 and 0.74 log10 reduction). This second dilution effect represented decreasing norovirus contamination on worker’s hands from repeated produce touches (Supplemental Material Appendix A, Figure 1). While this and other studies (Bouwknegt et al., 2015) found minimal associations between tactile transfer efficiencies and risk outcome estimates, our model suggests that the dilution effect from fomite surface tactile events can result in minimized contaminant concentration in the final packed produce. Further, there are likely subsequent dilution effects when produce is in the final packing box and when transported and repacked at retail stores. We anticipate these dilutions would further reduce consumer risk of norovirus infection. Scaling up to production of entire produce lots, we anticipate even greater attenuation in viral contamination attributed to these fomite surface tactile events. As previously noted, the focus of our analysis was on the infection risk to the one individual who consumes the focally contaminated product. When extrapolated beyond this single individual to the population-level, we do anticipate that contamination associated with harvesters and packers would affect more people. That being said, it is likely that these worker focal contamination events lead to sporadic norovirus infections rather than large-scale outbreaks associated with widespread contamination (e.g. sewage-contaminated irrigation water (EFSA, 2014; Verhaelen et al., 2013). Additionally, the effective risk mitigation strategies demonstrated for the single consumer in this model are expected to have protective effects among populations of consumers.

Strengths of our model include a detailed exposure assessment design of harvesting and packing and a well characterized human-environment contact network based on direct observation of fresh produce harvest and processing production lines from our past field work (Ailes et al., 2008; Johnston et al., 2006; Newman et al., 2017). A particular strength of our hand hygiene interventions is that we utilized published handwashing efficacy data for reducing norovirus contamination on hands, ranging from (0.58 to 1.58 log10 reduction) (Liu et al., 2010) to (4 to >6 log10 reduction) (Tuladhar, 2015). Additional strengths of the model include: simulating norovirus transmission during sequential produce harvesting and processing steps; calibrating the model to viral shedding and hand contamination data from norovirus human challenge studies; and including hand hygiene practices informed by global produce safety guidelines (FAO, 2012a; FDA, 2015). Regarding limitations, the first is that we did not include the important pathways of irrigation water or soil amendments in our study and instead, focused on transmission associated with direct contact with infected workers. As norovirus has been detected in irrigation water (El-Senousy et al., 2013; Kokkinos et al., 2017; Rusinol et al., 2020), future work will expand this model to investigate the contribution of irrigation water and rinse waters on risk to fresh produce consumers. Another limitation is that we did not consider other factors that may serve to modify infection risks, such as produce texture or food ligands which may enhance virus bindings and retention (Almand et al., 2017), internalization of norovirus into lettuce (Esseili et al., 2018), and surface cleaning and disinfection protocols.

Findings from our study demonstrate the primary importance of hand hygiene in preventing focal contamination with norovirus in important harvesting and packing agricultural settings. Future studies might focus on: evaluating the feasibility of modified handwashing protocols; consideration of alternative wash-sanitize regimens (Edmonds et al., 2012); and qualitative work to identify and address barriers to conducting adequate hand hygiene (e.g., access to handwashing stations). Translating results from this study into practice, future work with farmworkers should emphasize educational programs on norovirus transmission in the agriculture setting (Wainaina et al., 2020); offering refresher training sessions on hand hygiene and ill worker furlough procedures; and providing adequate hand hygiene facilities in primary production settings. Of particular interest is also investigating ways to improve handwashing compliance and efficacy, such as farmworker pay practices, updated handwashing protocols, and new hand hygiene products and formulations that enhance virus removal from workers’ hands. Finally, this and future work is well positioned to inform infection control policies in the agriculture and retail food settings for individuals returning to work following norovirus infection (duration of furlough, restriction from food preparation and food contact surfaces, etc.). Notably, during this time of the SARS-CoV-2 global pandemic, it is also imperative to evaluate these same hand hygiene and ill worker furlough policies as COVID-19 infection risk mitigation strategies for protection of the health of produce workers on farms and in packing/processing facilities.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Impact of norovirus-infected workers on produce contamination and consumer risks

Full (100%) compliance and effective (5 log10 removal) handwashing reduced risk

Gloves alone did not reduce maximum risk below 0.032 infections/consumption event

Bundled interventions resulted in the largest reductions in consumer risk

Equipment and transfers minimally contributed to contamination (rho= −0.091–0.057)

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Dr. Justin Remais for early advice regarding risk assessment models and to David Berendes for thoughtful consideration of alternative models. This work was partially supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 grant (J.S.S., grant 2T32ES012870–16), F30 grant (K.L.N., grant 1F30DK100097), the ARCS Foundation (K.L.N), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (J.S.L., grant 1K01AI087724), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM124280), the National Institute of Food and Agriculture at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (J.S.L., grant 2010–85212-20608, 2011–67012-30762, 2015–67017-23080, 2019–67017-29642; J.S.S., grant 2020–67034-31728), the Emory University Global Health Institute (J.S.L.), and the U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Food Research Initiative Competitive Grant Program (L.A.J., grant 2011–68003- 30395). The contents of this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ailes EC, Leon JS, Jaykus LA, Johnston LM, Clayton HA, Blanding S, Kleinbaum DG, Backer LC, Moe CL, 2008. Microbial concentrations on fresh produce are affected by postharvest processing, importation, and season. J Food Prot 71, 2389–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almand EA, Moore MD, Jaykus LA, 2017. Norovirus Binding to Ligands Beyond Histo-Blood Group Antigens. Front Microbiol 8, 2549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Estes MK, Crawford SE, Neill FH, Graham DY, 2008. Norwalk virus shedding after experimental human infection. Emerg Infect Dis 14, 1553–1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atmar RL, Opekun AR, Gilger MA, Estes MK, Crawford SE, Neill FH, Ramani S, Hill H, Ferreira J, Graham DY, 2014. Determination of the 50% human infectious dose for Norwalk virus. J Infect Dis 209, 1016–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker J, Vipond IB, Bloomfield SF, 2004. Effects of cleaning and disinfection in reducing the spread of Norovirus contamination via environmental surfaces. Journal of Hospital Infection 58, 42–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker SF, 2014. Risk of norovirus gastroenteritis from consumption of vegetables irrigated with highly treated municipal wastewater--evaluation of methods to estimate sewage quality. Risk Anal 34, 803–817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett SD, Sodha SV, Ayers TL, Lynch MF, Gould LH, Tauxe RV, 2018. Produce-associated foodborne disease outbreaks, USA, 1998–2013. Epidemiol Infect 146, 1397–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta MR, Marsh Z, Newman KL, Rebolledo PA, Huey M, Hall AJ, Leon JS, 2019. Norovirus outbreaks on college and university campuses. J Am Coll Health, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidawid S, Malik N, Adegbunrin O, Sattar SA, Farber JM, 2004. Norovirus cross-contamination during food handling and interruption of virus transfer by hand antisepsis: Experiments with feline calicivirus as a surrogate. Journal of Food Protection 67, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boehm AB, 2019. Risk-based water quality thresholds for coliphages in surface waters: effect of temperature and contamination aging. Environ Sci Process Impacts 21, 2031–2041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouwknegt M, Verhaelen K, Rzezutka A, Kozyra I, Maunula L, von Bonsdorff CH, Vantarakis A, Kokkinos P, Petrovic T, Lazic S, Pavlik I, Vasickova P, Willems KA, Havelaar AH, Rutjes SA, de Roda Husman AM, 2015. Quantitative farm-to-fork risk assessment model for norovirus and hepatitis A virus in European leafy green vegetable and berry fruit supply chains. Int J Food Microbiol 198, 50–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callejon RM, Rodriguez-Naranjo MI, Ubeda C, Hornedo-Ortega R, Garcia-Parrilla MC, Troncoso AM, 2015. Reported foodborne outbreaks due to fresh produce in the United States and European union: trends and causes. Foodborne Pathog Dis 12, 32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon JL, Papafragkou E, Park GW, Osborne J, Jaykus LA, Vinje J, 2006. Surrogates for the study of norovirus stability and inactivation in the environment: A comparison of murine norovirus and feline calicivirus. Journal of Food Protection 69, 2761–2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekaran S, Jiang SC, 2018. A dynamic transport model for quantification of norovirus internalization in lettuce from irrigation water and associated health risk. Sci Total Environ 643, 751–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatziprodromidou IP, Bellou M, Vantarakis G, Vantarakis A, 2018. Viral outbreaks linked to fresh produce consumption: a systematic review. J Appl Microbiol 124, 932–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Souza DH, Sair A, Williams K, Papafragkou E, Jean J, Moore C, Jaykus L, 2006. Persistence of caliciviruses on environmental surfaces and their transfer to food. Int J Food Microbiol 108, 84–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doultree JC, Druce JD, Birch CJ, Bowden DS, Marshall JA, 1999. Inactivation of feline calicivirus, a Norwalk virus surrogate. Journal of Hospital Infection 41, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duizer E, Bijkerk P, Rockx B, De Groot A, Twisk F, Koopmans M, 2004. Inactivation of caliciviruses. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 70, 4538–4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret S, Pouillot R, Fanaselle W, Papafragkou E, Liggans G, Williams L, Van Doren JM, 2017. Quantitative Risk Assessment of Norovirus Transmission in Food Establishments: Evaluating the Impact of Intervention Strategies and Food Employee Behavior on the Risk Associated with Norovirus in Foods. Risk Anal 37, 2080–2106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds SL, McCormack RR, Zhou SS, Macinga DR, Fricker CM, 2012. Hand hygiene regimens for the reduction of risk in food service environments. J Food Prot 75, 1303–1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA, 2014. Scientific Opinion on the risk posed by pathogens in food of non-animal origin. Part 2 (Salmonella and Norovirus in berries). EFSA Journal 12, 3706. [Google Scholar]

- El-Senousy WM, Costafreda MI, Pinto RM, Bosch A, 2013. Method validation for norovirus detection in naturally contaminated irrigation water and fresh produce. International Journal of Food Microbiology 167, 74–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery HC, 1990. Changing poor handwashing habits - a continuing challenge for sanitations. Dairy, Food and Environmental Sanitation 10, 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U.S., 2011. Exposure Factors Handbook 2011 Edition (Final Report), in: Agency, U.S.E.P. (Ed.), Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- EPA, U.S., 2012. Recreational Water Quality Criteria, in: Agency, U.S.E.P. (Ed.), OFFICE OF WATER 820-F-12–058 [Google Scholar]

- EPA., U.S., 2018. Exposure Factors Handbook Chapter 9 (Update): Intake of Fruits and Vegetables., in: Development, U.S.E.O.o.R.a. (Ed.). EPA, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Escudero BI, Rawsthorne H, Gensel C, Jaykus LA, 2012. Persistence and transferability of noroviruses on and between common surfaces and foods. J Food Prot 75, 927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esseili MA, Meulia T, Saif LJ, Wang Q, 2018. Tissue Distribution and Visualization of Internalized Human Norovirus in Leafy Greens. Appl Environ Microbiol 84, e00292–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ethelberg S, Lisby M, Bottiger B, Schultz AC, Villif A, Jensen T, Olsen KE, Scheutz F, Kjelso C, Muller L, 2010. Outbreaks of gastroenteritis linked to lettuce, Denmark, January 2010. Euro Surveill 15, 19484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans EA-O, Samuel EJ, Redmond EC, A case study of food handler hand hygiene compliance in high-care and high-risk food manufacturing environments using covert-observation. Int J Environ Health Res, 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAO, 2012a. Guidelines on the Application of General Principles of Food Hygiene to the Control of Viruses in Food, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, 2012b. Guidelines on the Application of General Principles of Food Hygiene to the Control of Viruses in Food, CAV/GL 79–2012. FAO and WHO, CODEX ALIMENTARIUS International Food Standards. [Google Scholar]

- FAO, 2017. Code of Hygienic Practice for Fresh Fruits and Vegetables. FAO and WHO, CODEX ALIMENTARIUS International Food Standards. [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2000. CFP 2000 Backgrounder: No Bare Hand Contact, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- FDA, 2015. Food Safety Modernization Act final rule on produce safety, standards for the growing, harvesting, packing, and holding of produce for human consumption. 21 CFR Parts 16 and 112, vol. FDA-2011-N-0921. [Google Scholar]

- Felix- Valenzuela L, Resendiz- Sandoval M, Burgara- Estrella A, Hernández J, Mata-Haro V, 2012. Quantitative Detection of Hepatitis A, Rotavirus and Genogroup I Norovirus by RT- qPCR in Fresh Produce from Packinghouse Facilities. Journal of Food Safety 32, 467–473. [Google Scholar]

- Fung IC, Cairncross S, How often do you wash your hands? A review of studies of handwashing practices in the community during and after the SARS outbreak in 2003. Int J Environ Health Res 3, 161–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LR, Selman CA, Radke V, Ripley D, Mack JC, Reimann DW, Stigger T, Motsinger M, Bushnell L, 2006. Food worker hand washing practices: an observation study. J Food Prot 69, 2417–2423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grove SF, Suriyanarayanan A, Puli B, Zhao H, Li M, Li D, Schaffner DW, Lee A, 2015. Norovirus cross-contamination during preparation of fresh produce. International Journal of Food Microbiology 198, 43–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huvarova V, Kralik P, Vasickova P, Kubankova M, Verbikova V, Slany M, Babak V, Moravkova M, 2018. Tracing of Selected Viral, Bacterial, and Parasitic Agents on Vegetables and Herbs Originating from Farms and Markets. J Food Sci 83, 3044–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacxsens L, Stals A, De Keuckelaere A, Deliens B, Rajkovic A, Uyttendaele M, 2017. Quantitative farm-to-fork human norovirus exposure assessment of individually quick frozen raspberries and raspberry puree. Int J Food Microbiol 242, 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LM, Jaykus LA, Moll D, Anciso J, Mora B, Moe CL, 2006. A field study of the microbiological quality of fresh produce of domestic and Mexican origin. Int J Food Microbiol 112, 83–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LM, Jaykus LA, Moll D, Martinez MC, Anciso J, Mora B, Moe CL, 2005. A field study of the microbiological quality of fresh produce. J Food Prot 68, 1840–1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampf G, Grotheer D, Steinmann J, 2005. Efficacy of three ethanol-based hand rubs against feline calicivirus, a surrogate virus for norovirus. Journal of Hospital Infection 60, 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby AE, Shi J, Montes J, Lichtenstein M, Moe CL, 2014. Disease course and viral shedding in experimental Norwalk virus and Snow Mountain virus infection. J Med Virol 86, 3055–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk MD, Pires SM, Black RE, Caipo M, Crump JA, Devleesschauwer B, Dopfer D, Fazil A, Fischer-Walker CL, Hald T, Hall AJ, Keddy KH, Lake RJ, Lanata CF, Torgerson PR, Havelaar AH, Angulo FJ, 2015. World Health Organization Estimates of the Global and Regional Disease Burden of 22 Foodborne Bacterial, Protozoal, and Viral Diseases, 2010: A Data Synthesis. PLoS Med 12, e1001921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos P, Kozyra I, Lazic S, Bouwknegt M, Rutjes S, Willems K, Moloney R, de Roda Husman AM, Kaupke A, Legaki E, D’Agostino M, Cook N, Rzezutka A, Petrovic T, Vantarakis A, 2012. Harmonised investigation of the occurrence of human enteric viruses in the leafy green vegetable supply chain in three European countries. Food Environ Virol 4, 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokkinos P, Kozyra I, Lazic S, Soderberg K, Vasickova P, Bouwknegt M, Rutjes S, Willems K, Moloney R, de Roda Husman AM, Kaupke A, Legaki E, D’Agostino M, Cook N, von Bonsdorff CH, Rzezutka A, Petrovic T, Maunula L, Pavlik I, Vantarakis A, 2017. Virological Quality of Irrigation Water in Leafy Green Vegetables and Berry Fruits Production Chains. Food Environ Virol 9, 72–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, Galabov AS, Sattar SA, Dohner L, Pivert A, Payan C, Wolff MH, Yilmaz A, Steinmann J, 2006. Virucidal activity of a new hand disinfectant with reduced ethanol content: comparison with other alcohol-based formulations. J. Hospital Infection 62, 98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lages SL, Ramakrishnan MA, Goyal SM, 2008. In-vivo efficacy of hand sanitisers against feline calicivirus: a surrogate for norovirus. Journal of Hospital Infection 68, 159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Guyader FS, Mittelholzer C, Haugarreau L, Hedlund KO, Alsterlund R, Pommepuy M, Svensson L, 2004. Detection of noroviruses in raspberries associated with a gastroenteritis outbreak. International Journal of Food Microbiology 97, 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon-Felix J, Martinez-Bustillos RA, Baez-Sanudo M, Peraza-Garay F, Chaidez C, 2010. Norovirus Contamination of Bell Pepper from Handling During Harvesting and Packing. Food and Environmental Virology 2, 211–217. [Google Scholar]

- Lim KY, Hamilton AJ, Jiang SC, 2015. Assessment of public health risk associated with viral contamination in harvested urban stormwater for domestic applications. Sci Total Environ 523, 95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Chien Y-W, Papafragkou E, Hsiao H-M, Jaykus L-A, Moe C, 2009. Persistence of human noroviruses on food preparation surfaces and human hands. Food and Environmental Virology 1, 141–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Escudero B, Jaykus LA, Montes J, Goulter RM, Lichtenstein M, Fernandez M, Lee JC, De Nardo E, Kirby A, Arbogast JW, Moe CL, 2013. Laboratory evidence of norwalk virus contamination on the hands of infected individuals. Appl Environ Microbiol 79, 7875–7881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P, Yuen Y, Hsiao HM, Jaykus LA, Moe C, 2010. Effectiveness of liquid soap and hand sanitizer against Norwalk virus on contaminated hands. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 76, 394–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubran MB, Pouillot R Fau - Bohm S, Bohm S Fau - Calvey EM, Calvey Em Fau - Meng J, Meng J Fau - Dennis S, Dennis S, Observational study of food safety practices in retail deli departments. J Food Prot 10, 1849–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macinga DR, Sattar SA, Jaykus LA, Arbogast JW, 2008. Improved inactivation of nonenveloped enteric viruses and their surrogates by a novel alcohol-based hand sanitizer. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 74, 5047–5052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maitland J, Boyer R, Gallagher D, Duncan S, Bauer N, Kause J, Eifert J, 2013. Tracking Cross-Contamination Transfer Dynamics at a Mock Retail Deli Market Using GloGerm. Journal of Food Protection 76, 272–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mara D, Sleigh A, 2010. Estimation of norovirus infection risks to consumers of wastewater-irrigated food crops eaten raw. J Water Health 8, 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]