Abstract

Objective

The study sought to assess the feasibility of replacing the International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) with the International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision (ICD-11) for morbidity coding based on content analysis.

Materials and Methods

The most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes from each chapter covering 60% of patients were identified from Medicare claims and hospital data. Each ICD-10-CM code was recoded in the ICD-11, using postcoordination (combination of codes) if necessary. Recoding was performed by 2 terminologists independently. Failure analysis was done for cases where full representation was not achieved even with postcoordination. After recoding, the coding guidance (inclusions, exclusions, and index) of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 codes were reviewed for conflict.

Results

Overall, 23.5% of 943 codes could be fully represented by the ICD-11 without postcoordination. Postcoordination is the potential game changer. It supports the full representation of 8.6% of 943 codes. Moreover, with the addition of only 9 extension codes, postcoordination supports the full representation of 35.2% of 943 codes. Coding guidance review identified potential conflicts in 10% of codes, but mostly not affecting recoding. The majority of the conflicts resulted from differences in granularity and default coding assumptions between the ICD-11 and ICD-10-CM.

Conclusions

With some minor enhancements to postcoordination, the ICD-11 can fully represent almost 60% of the most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes. Even without postcoordination, 23.5% full representation is comparable to the 24.3% of ICD-9-CM codes with exact match in the ICD-10-CM, so migrating from the ICD-10-CM to the ICD-11 is not necessarily more disruptive than from the International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revision–Clinical Modification to the ICD-10-CM. Therefore, the ICD-11 (without a CM) should be considered as a candidate to replace the ICD-10-CM for morbidity coding.

Keywords: ICD-11, ICD-10, ICD-10-CM, controlled medical vocabularies, medical terminologies

INTRODUCTION

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD) has been in use for collection of global health trends and statistics for over a century.1,2 Its latest version, the International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision (ICD-11), was adopted in May 2019 and will be implemented in member countries of the World Health Organization starting in January 2022.3–5 Owing to specific requirements in some countries, over 2 dozen national extensions of the ICD have been developed for past versions of ICD. In the United States, the first version of the national extension known as Clinical Modification (CM) was the International Classification of Diseases–Ninth Revision–Clinical Modification released in 1979 (ICD-9-CM). According to the official documentation of the ICD-9-CM, “the term ‘clinical’ is used to emphasize the modification's intent: to serve as a useful tool in the area of classification of morbidity data for indexing of medical records, medical care review, and ambulatory and other medical care programs, as well as for basic health statistics. To describe the clinical picture of the patient, the codes must be more precise than those needed only for statistical groupings and trend analysis.”6 The same practice of modifying the international ICD core for clinical purpose continued in the ICD-10-CM, which replaced the ICD-9-CM in 2015.

The main advantage of developing a U.S. national extension is the ability to add necessary detail under the framework of the international core to serve clinical and administrative (eg, reimbursement) needs. Another advantage is that updates to the national extension can happen more frequently, as the ICD-10-CM is updated yearly compared with the 3-year cycle for the ICD-10. However, there are potential drawbacks. First, significant effort is involved in maintaining an extension. Second, there is usually a delay between the release of the international version and the national extension. Moreover, there can be incongruence between the national extension and the international core. In principle, everything in the CM should be totally compatible with the parent system. In practice, however, some significant differences can be observed between the ICD-10-CM and ICD-10. For example, the ICD-10 category E14 Unspecified diabetes mellitus is not present in the ICD-10-CM because diabetes mellitus of unspecified type is coded under E11 Type 2 diabetes mellitus by default. Another example is the addition to the ICD-10-CM of a new category, K68 Disorders of retroperitoneum, that is not present in the ICD-10.

Decades of research in controlled medical vocabularies and knowledge representation have resulted in better understanding of the principles and best practices in medical terminology management.7 Some of these principles have been embraced by the ICD-11. Apart from the introduction of the foundation component, the most noticeable novel feature in the ICD-11 is postcoordination.8,9 Postcoordination is the principled combination of codes to represent new meaning—a powerful and efficient way to expand the coverage, expressivity, and granularity of a terminology.10 Toward this end, the ICD-11 offers 14 500 extension codes for postcoordination. This new capability, together with the considerable increase in the number of codes, 4015 (37.9%) more codes than the ICD-10, may lead one to question whether it is still necessary to develop a CM for the ICD-11.10 In fact, the recommendations from the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics to the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services include research to determine whether the ICD-11 can fully support morbidity classification in the United States without development of a U.S. clinical modification.11

The objective of this investigation is to assess the feasibility of replacing the ICD-10-CM with the ICD-11 for morbidity coding based on content analysis and coverage. More specifically, we assess whether some 1000 frequently used ICD-10-CM codes can be fully represented in the ICD-11, with or without postcoordination, and we analyze the reason why full representation cannot be achieved in the remaining cases.

While there are multiple studies comparing the ICD-11 with the ICD-10, a PubMed search returns only 2 that directly compared the ICD-11 with the ICD-10-CM.10,12 Austin et al12 compared the performance of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 in the capture of adverse events to support quality measurement and safety. Our previous study compared the coverage of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 in 6 disease areas.10 The specific contributions of the present study include (1) first systematic and comprehensive comparison of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11; (2) recoding of a representative sample of frequently used ICD-10-CM codes, using postcoordination when necessary, performed independently by 2 terminologists (to improve and assess coding variability); (3) exhaustive analysis of the reason why full representation cannot be achieved; (4) reviewing coding guidance (inclusions, exclusions, and index) to identify subtle differences in code meaning that may not be conveyed by the code names and hierarchies alone; and (5) assessment of the overall feasibility of replacing the ICD-10-CM with the ICD-11 in morbidity coding. The list of ICD-10-CM codes in this study and their recoding results in the ICD-11 are provided in Supplementary Appendix A.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We first identified the most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes from insurance claims and hospital data, and then recoded them using the ICD-11, using postcoordination if necessary. We assessed the coverage of the ICD-11 and noted reasons for not achieving full representation. We then looked for potential conflicts caused by the accompanying coding guidance.

Most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes

Through the Virtual Research Data Center,13 we gathered ICD-10-CM codes in inpatient and outpatient Medicare claims in 2017, the latest full year of data at the time of the study. Because most Medicare beneficiaries were over 65 years of age, obstetric and pediatric codes (chapter 15, 16, and 17) were missing. For these 3 chapters, we used data from 3 community hospitals (1 tertiary, 1 secondary, and 1 pediatrics tertiary care center) affiliated with the University of Nebraska Medical Center. For this smaller data source, we used all data from October 2015 to March 2020 to maximize coverage. For each chapter, we identified the most frequently used codes needed to cover 60% of unique patients with any code from that chapter. We did not differentiate between principal and secondary diagnosis codes. The 60% threshold was used to keep the total number of codes under 1000. We excluded codes that were no longer valid in 2021. This study was rated as not human subject research by the Office of Human Research Protection at the National Institutes of Health.

Recoding ICD-10-CM codes in the ICD-11

Best matching ICD-11 code(s), postcoordination, and match type

For each ICD-10-CM code, we identified the best matching ICD-11 code at the lowest (or “leaf”) level. Recoding was done independently by 2 authors, J.X. and S.M.-L., who are experts in the ICD-10-CM and very knowledgeable in the ICD-11, using the online browser.14 All discrepancies were recorded and discussed to reach consensus. We measured interrater agreement by percentage of code concurrence and the Krippendorff’s alpha (an extension of kappa that could handle multiple raters and different data types).15 Our recoding guidelines are the following:

Follow the ICD-11 morbidity coding reference guide.9

Ignore parts of the ICD-10-CM or ICD-11 name that conveyed absence of information eg, gout unspecified, Zoster without complications.

Use ICD-11 codes that are equivalent or broader than the ICD-10-CM code (see Failure Analysis for Exceptions).

If a broader ICD-11 code is used, attempt postcoordination, as guided by the browser, to improve the match. For example, the ICD-10-CM code H52.13 Myopia, bilateral was recoded as the broader ICD-11 code 9D00.0 Myopia. Full representation could be achieved with postcoordination by adding the extension code XK9J Bilateral.

We defined 3 levels of representation: (1) full representation without postcoordination, (2) full representation with postcoordination, and (3) partial representation (postcoordination was not possible or insufficient to achieve full representation). This determination was based on the name and hierarchical location of the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 codes. Of note, we did not consider matches in index or inclusion terms as indicative of full representation, as these terms were often narrower than the codes themselves. For example, the ICD-10-CM code H54.8 Legal blindness, as defined in USA was recoded as the ICD-11 code 9D90.3 Severe vision impairment that had “Legal blindness—USA” as an inclusion, but we still considered this partial representation because severe vision impairment remained broader than legal blindness defined in a specific country.

Failure analysis

All cases with partial representation were reviewed to determine the reason for failure to achieve full representation and the type of missing information.

Coding guidance review

Both the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 provide coding guidance through inclusions, exclusions, and an index. Most ICD-11 codes are defined by a textual description. Apparently equivalent codes sometimes have different meanings because of differences in the coding guidance.

Definitions, inclusions, and exclusions

We reviewed the coding guidance for the ICD-10-CM codes and their ICD-11 targets for possible conflicts. These conflicts could be between the following:

ICD-11 textual description and inclusions or exclusions of the ICD-10-CM code and its ancestors

inclusions of the ICD-10-CM code and its ancestors, and exclusions of the ICD-11 code and its ancestors (eg, an inclusion in ICD-10-CM was an exclusion in ICD-11)

exclusions of the ICD-10-CM code and its ancestors, and inclusions of the ICD-11 code and its ancestors

Index terms

An index conflict occurred when an index term of the ICD-10-CM code was also found in the ICD-11 index but pointing to a code other than the one selected in recoding. Because 1 ICD code could be associated with many index terms, it was impractical to review them all. Therefore, we used normalized lexical matching to screen for likely conflicts. Normalization involved splitting a term into its constituent words, ignoring punctuations, lower-casing and converting each word to its base form, then sorting them in alphabetical order. Normalization is a common method to deal with the variability in natural language.16 However, it can give rise to erroneous results (eg, “baby blues” and “blue baby” are normalized to the same term). We extracted all index terms pointing to the ICD-10-CM codes, normalized them with the Unified Medical Language System Lexical Tool, luinorm,17 and then matched them to the ICD-11 normalized index terms. All cases in which the matched ICD-11 index term pointed to a code different from the one selected in recoding were reviewed.

RESULTS

Most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes

In the Medicare data, there were 61 million unique patients and 28 981 unique ICD-10-CM codes. In the hospital data, there were 778 000 unique patients and 23 832 unique ICD-10-CM codes. We identified altogether 962 unique ICD-10-CM codes required to cover 60% of unique patients, of which 943 were still active in 2021. The number of codes from each chapter varied considerably, ranging from 5 (chapter 3) to 363 codes (chapter 19) (Table 1). This was dependent on the total number of codes in the chapter and the spread of usage. Usage spread was reflected by the percentage of codes required for 60% coverage (Table 1, right column) which also showed significant variation. The full list of codes is available as online Supplementary Appendix A.

Table 1.

Distribution of most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes by chapter

| Chapter | Code Range | Total No. of Unique Codes | Top Unique Codes Covering 60% of Unique Patients | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A00-B99 Certain infectious and parasitic diseases | 1058 | 19 | 1.8 |

| 2 | C00-D49 Neoplasms | 1661 | 66 | 4.0 |

| 3 | D50-D89 Diseases of the blood and blood-forming organs and certain disorders involving the immune mechanism | 251b | 5b | 2.0 |

| 4 | E00-E89 Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases | 908 | 10 | 1.1 |

| 5 | F01-F99 Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental disorders | 747 | 10 | 1.3 |

| 6 | G00-G99 Diseases of the nervous system | 622 | 13 | 2.1 |

| 7 | H00-H59 Diseases of the eye and adnexa | 2606 | 51 | 2.0 |

| 8 | H60-H95 Diseases of the ear and mastoid process | 653 | 18 | 2.8 |

| 9 | I00-I99 Diseases of the circulatory system | 1378 | 14 | 1.0 |

| 10 | J00-J99 Diseases of the respiratory system | 341 | 12 | 3.5 |

| 11 | K00-K95 Diseases of the digestive system | 799 | 25 | 3.1 |

| 12 | L00-L99 Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue | 871 | 61 | 7.0 |

| 13 | M00-M99 Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | 6487 | 43 | 0.7 |

| 14 | N00-N99 Diseases of the genitourinary system | 672 | 10 | 1.5 |

| 15 | O00-O9A Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | 2267 | 45 | 2.0 |

| 16 | P00-P96 Certain conditions originating in the perinatal period | 443 | 12 | 2.7 |

| 17 | Q00-Q99 Congenital malformations, deformations and chromosomal abnormalities | 838 | 53 | 6.3 |

| 18 | R00-R99 Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified | 722 | 56 | 7.8a |

| 19 | S00-T88 Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes | 40 654a | 363a | 0.9 |

| 20 | V00-Y99 External causes of morbidity | 6940 | 20 | 0.3b |

| 21 | Z00-Z99 Factors influencing health status and contact with health services | 1266 | 37 | 2.9 |

| Total | 72 184 | 943 | 1.3 | |

ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification.

Highest.

Lowest.

Recoding ICD-10-CM codes in the ICD-11

Best matching ICD-11 code(s), postcoordination, and match type

Of the 943 codes, 222 (23.5%) could be fully represented without postcoordination, 81 (8.6%) could be fully represented with postcoordination, and the remaining 640 (67.9%) could be only partially represented (Supplementary Appendix A). Owing to the considerable difference in the number of codes among chapters (Table 1), we also performed a chapter-based analysis (Table 2). All codes from chapter 3 (blood and immune system) could be fully represented, while none of the codes from chapters 19 (injury and poisoning) and 20 (external causes of morbidity) could be fully represented. On average, 47.1% of codes per chapter could be fully represented without postcoordination, corresponding to an average patient coverage of 53.1%. Note that the chapter-based patient coverage here refers to the proportion of patient coverage among the 943 ICD-10-CM codes in this study. Patient coverage data cannot be aggregated across chapters because they come from different sources.

Table 2.

Recoding ICD-10-CM codes in the ICD-11, results by chapter

| Full Representation Without Postcoordination |

Full Representation With Postcoordination |

Partial Representation |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter | % of Codes | % of Patient Coverage | % of Codes | % of Patient Coverage | % of Codes | % of Patient Coverage |

| 1 | 52.6a | 70.1a | 21.1 | 14.3 | 26.3 | 15.6 |

| 2 | 37.9a | 46.8a | 36.4 | 28.9 | 25.8 | 24.2 |

| 3 | 100.0a | 100.0a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 4 | 80.0a | 86.6a | 10.0 | 4.7 | 10.0 | 8.7 |

| 5 | 60.0a | 54.5a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 40.0 | 45.5 |

| 6 | 61.5a | 55.8a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 38.5 | 44.2 |

| 7 | 17.6 | 29.6 | 13.7 | 11.2 | 68.6a | 59.2a |

| 8 | 16.7 | 30.0 | 44.4a | 37.4a | 38.9 | 32.6 |

| 9 | 64.3a | 87.6a | 7.1 | 3.4 | 28.6 | 9.0 |

| 10 | 83.3a | 92.8a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.7 | 7.2 |

| 11 | 64.0a | 81.2a | 8.0 | 3.1 | 28.0 | 15.8 |

| 12 | 16.4 | 21.6 | 14.8 | 11.2 | 68.9a | 67.2a |

| 13 | 20.9a | 33.1a | 34.9a | 32.4a | 44.2 | 34.4 |

| 14 | 70.0a | 72.6a | 10.0 | 5.4 | 20.0 | 22.0 |

| 15 | 26.7 | 34.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 73.3a | 65.8a |

| 16 | 91.7a | 96.7a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 | 3.3 |

| 17 | 45.3 | 44.1 | 5.7 | 2.9 | 49.1a | 53.0a |

| 18 | 53.6a | 56.3a | 0.0 | 0.0 | 46.4 | 43.7 |

| 19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100.0a | 100.0a |

| 20 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.0 | 3.1 | 95.0a | 96.9a |

| 21 | 27.0 | 21.5 | 13.5 | 16.5 | 59.5a | 62.0a |

| Chapter Average | 47.1 | 53.1 | 10.7 | 8.3 | 42.2 | 38.6 |

ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification; ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision.

Dominant category in chapter.

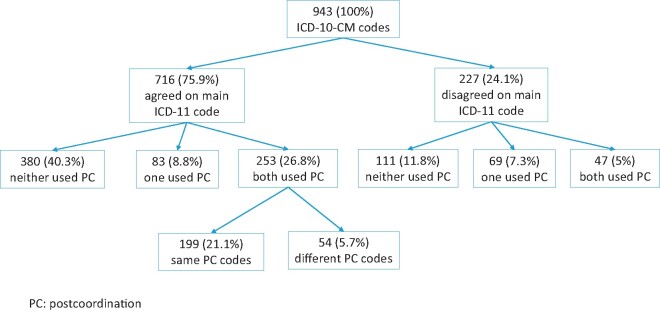

Concerning coding variability, agreement on the ICD-11 main codes was observed in 716 (75.9%) cases before discussion (Figure 1). Among these 716 cases, postcoordination was used by both terminologists in 253 cases, and they used the same postcoordination codes in 199 cases (78.7% agreement). The Krippendorff’s alphas for the main code and postcoordination were 0.756 and 0.786, respectively, generally indicating good to excellent agreement.

Figure 1.

Agreement of International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision (ICD-11) coding between the 2 terminologists. ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification; PC: postcoordination.

Failure analysis

We reviewed all 640 ICD-10-CM codes with partial representation and found 3 types of reason for not achieving full representation (Table 3).

Table 3.

Analysis of failure of full representation even with postcoordination

| Reason for Failure of Full Representation | ICD-10-CM Codes a | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Missing information in postcoordination | Episode of care | 375 (39.8) |

| Laterality | 53 (5.6) | |

| Mode of exposure | 35 (3.7) | |

| Trimester of pregnancy | 16 (1.7) | |

| Other missing information | ||

| - Anatomy | 45 (4.8) | |

| - Devices | 25 (2.7) | |

| - Injury dimension | 25 (2.7) | |

| - Etiology | 16 (1.7) | |

| - Substances | 11 (1.2) | |

| - Severity | 10 (1.1) | |

| - Temporality | 5 (0.5) | |

| - External cause | 4 (0.4) | |

| - Histopathology | 3 (0.3) | |

| - Capacity context | 1 (0.1) | |

| - Others | 100 (10.6) | |

| Total | 245 (26.0) | |

| B. Residual categories | 131 (13.9) | |

| C. ICD-11 more specific | 13 (1.4) | |

Values are n (%).

ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification; ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision.

One code could be associated with more than 1 type of missing information.

Missing information in postcoordination

We identified 3 kinds of limitation in postcoordination:

Postcoordination not allowed. For example, the ICD-10-CM code H93.13 Tinnitus, bilateral was recoded as the ICD-11 code MC41Tinnitus which did not allow postcoordination. Full representation could have been achieved by allowing postcoordination (with the extension code XK9J Bilateral).

Addition of existing extension code not allowed. For example, the ICD-10-CM code M25.552 Pain in left hip was recoded by postcoordination as ME82 Pain in joint & XA4XS4 Hip joint. Full representation could have been achieved if further addition of the extension code XK8G Left was allowed.

Missing extension code. Most ICD-10-CM codes for injury and poisoning included episode of care information (eg, S00.31XA Abrasion of nose, initial encounter), which could not be captured in the ICD-11 because there was no extension code for episode of care. Another example was adverse reactions caused by drugs, which had different codes in the ICD-10-CM according to the mode of exposure (“adverse effect” if the drug was properly administered, “poisoning” for improper use, and “underdosing” if taking less than required). In the ICD-11, there was no such distinction and only a general code NE60 Harmful effects of drugs, medicaments or biological substances, not elsewhere classified was available. Mode of exposure could be captured by adding 3 extension codes. Similarly, capturing trimester of pregnancy would require 3 new extension codes.

Residual categories

Both the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 have residual categories that usually have “other” or “not elsewhere classified” in their names. These codes are “catch-all” codes to ensure coding of every possible case. The meaning of residual codes depends on the neighboring codes, especially the siblings. Therefore, unless all surrounding codes are identical, residual codes from the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11 cannot be assumed to be equivalent. Consider for example the ICD-10-CM code H26.8 Other specified cataract and the ICD-11 code 9B10.2Y Other specified cataracts. H26.8 has a sibling H26.3 Drug-induced cataract while 9B10.2Y does not. This means that drug-induced cataract is included in 9B10.2Y but not n H26.8, so 9B10.2Y is only a partial match of H26.8, despite their exactly matching names.

ICD-11 code more specific than ICD-10-CM code

We would normally select an ICD-11 code that was equivalent to or broader than the ICD-10-CM code. In some cases, the ICD-11 coding guidance pointed to a code more specific than the ICD-10-CM code. For example, the ICD-10-CM code M62.82 Rhabdomyolysis was recoded to the narrower code FB32.20 Idiopathic rhabdomyolysis because the ICD-11 index term “rhabdomyolysis NOS” pointed to this code. We considered these cases partial representation because idiopathic rhabdomyolysis was more specific than rhabdomyolysis. Of note, postcoordination is not applicable here because postcoordination can only refine the meaning of a broad code but cannot make a narrow code broader (eg, postcoordination cannot remove the “idiopathic” characterization from FB32.20).

As shown in Table 3, 4 types of missing information (episode of care, laterality, mode of exposure, and trimester of pregnancy) accounted for a large proportion of cases. By adding 9 extension codes (3 episodes of care, 3 trimesters, and 3 modes of exposure) and allowing the addition of laterality modifiers to applicable anatomical entities, the number of ICD-10-CM codes that could be fully postcoordinated would increase from 81 (8.6%) to 332 (35.2%).

Coding guidance review

Definitions, inclusions and exclusions

We found no conflicts arising from the ICD-11 definitions. We found 10 cases of conflict among the inclusion and exclusion terms (Table 4, left half). In 1 case, there was actual conflict which required changing the target ICD-11 code. This involved the ICD-10-CM code O99.820 Streptococcus B carrier state complicating pregnancy, originally recoded to JA65.Y Maternal care for other specified conditions predominantly related to pregnancy. One of the ancestors of the ICD-11 code had an exclusion “Maternal infectious diseases classifiable elsewhere but complicating pregnancy, childbirth or the puerperium (JB63),” which indicated that, in this case, JB63 should be used instead. Other conflicts were potential ones which only occurred in some specific situations, and they belonged to 3 types:

Table 4.

Conflicts discovered by review of inclusion, exclusion, and index terms

| Inclusion and Exclusion Terms |

Index Terms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Conflict | Number of Conflicts | Unique ICD-10-CM Codes Affected | Number of Conflicts | Unique ICD-10-CM Codes Affected |

| Actual conflict—target ICD-11 code changed | 1 | 1 | 8 | 3 |

| Potential conflict | ||||

| 1. Partial overlap | 6 | 6 | 109 | 41 |

| 2. Granularity difference | 2 | 2 | 119 | 54 |

| 3. Default assumption | 1 | 1 | 20 | 12 |

| Total | 10 | 10 | 266 | 93 |

ICD-10-CM: International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification; ICD-11: International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision.

Partial overlap—an inclusion in one classification was an exclusion in the other and pointed to a broad code different from the originally chosen code. For example, the ICD-10-CM code A41.9 Sepsis, unspecified organism was recoded as the ICD-11 code 1G40 Sepsis without septic shock. “Septicemia” was an inclusion for A41.9 but an exclusion for 1G40, which pointed to MA15 Microbiological findings in blood, blood-forming organs, or the immune system. The ICD-11 code 1G40 was correct in the broader context of sepsis. However, in the special case of septicemia one should use MA15.

Granularity difference—an inclusion in one classification was an exclusion in the other and pointed to a specific code different from the originally chosen code. For example, the ICD-10-CM code K59.00 Constipation, unspecified was recoded as the ICD-11 code ME05.0 Constipation. “Fecal impaction” was an exclusion for K59.00 but an inclusion for ME05.0. In the ICD-10-CM, “fecal impaction” pointed to the more specific code K56.41 Fecal impaction. In this case, the ICD-10-CM was finer-grained and had distinct codes for specific causes of constipation, but the recoding was correct at the broader level.

Default assumption—an inclusion in one classification was an exclusion in the other, but the chosen code was correct according to certain default assumption. For example, the ICD-10-CM code R73.09 Other abnormal glucose was recoded as 5A40.Z Intermediate hyperglycaemia, unspecified in the ICD-11. In the ICD-11, 5A40.Z was defined as “a metabolic disorder characterized by glucose levels too high to be considered normal, though not high enough to meet the criteria for diabetes,” ie, a kind of prediabetes. In the ICD-10-CM, R73.09 had an inclusion “abnormal glucose NOS.” In the ICD-11, 5A40.Z had an exclusion “elevated blood glucose level.” Even though the 2 inclusion and exclusion terms were not exactly the same, one subsumed the other, and they were considered in conflict. In the ICD-11, the exclusion term “elevated blood glucose level” pointed to MA18.0 Elevated blood glucose level (a finding, not a metabolic disorder). However, the original recoding was considered correct because, in the ICD-11 index, “abnormal glucose” pointed to 5A40.Z, indicating that unspecified abnormal glucose was coded in the ICD-11 as a metabolic disorder by default.

Index terms

Of the 266 conflicts, 8 were real conflicts requiring the change of 3 target ICD-11 codes (Table 4, right half). For example, the ICD-10-CM code B19.20 Unspecified viral hepatitis C without hepatic coma was originally recoded as 1E5Z Viral hepatitis, unspecified. “Hepatitis C” was indexed to B19.20 in the ICD-10-CM but to 1E51.1 Chronic hepatitis C in the ICD-11, indicating that unspecified hepatitis C was coded as chronic hepatitis C in the ICD-11. Other cases were potential conflicts. Some examples were the following:

Partial overlap—the ICD-10-CM code Q25.0 Patent ductus arteriosus was recoded as LA8B.4 Patent arterial duct. “Patent ductus arteriosus aneurysm” was indexed to Q25.0 in ICD-10-CM but to LA8B.Y Other specified congenital anomaly of great arteries including arterial duct in the ICD-11.

Granularity difference—the ICD-10-CM code L60.3 Nail dystrophy was recoded as EE10.5 Nail dystrophy, not otherwise specified. “Spoon nail” was indexed to L60.3 in the ICD-10-CM but to EE10.0 Abnormality of nail shape in the ICD-11. In this case, ICD-11 had finer-grained codes for nail abnormalities than the ICD-10-CM.

Default assumption—the ICD-10-CM code O03.9 Complete or unspecified spontaneous abortion without complication was recoded as JA00.09 Spontaneous abortion, complete or unspecified, without complication. While “abortion” was indexed to O03.9, indicating that ICD-10-CM assumed spontaneous abortion by default, in the ICD-11, “abortion” was indexed to a more general code JA00.2 Unspecified abortion.

DISCUSSION

Coverage of the ICD-10-CM by the ICD-11

Compared with our previous study,10 this is a more comprehensive coverage analysis based on real-world data, which substantiates our appraisal of the feasibility of replacing the ICD-10-CM with the ICD-11. Of the 943 codes that we studied, representing the most frequently used codes in each chapter, 23.5% could be fully represented without postcoordination, and a further 8.6% with postcoordination. Analysis of the partially represented codes revealed that a few types of missing information accounted for a large number of cases. These are the “low-hanging fruits.” Addition of 9 extension codes would increase full postcoordination from 8.6% to 35.2%, bringing the proportion of full representation from 32.1% to 58.7%. Further improvement can be achieved by adding more extension codes, though with diminishing returns. According to our analysis, adding extension codes in the subbranches of anatomy, devices and injury dimensions among the ICD-11 extension codes will have the largest impact.

In the ICD, coding guidance (inclusions, exclusions, and index) provides important references in the meaning and the boundaries of a code. Even when an ICD-10-CM code has exactly the same description as an ICD-11 code, nuances in meaning can still exist as indicated by the coding guidance. In this study, coding guidance conflicts resulted in changing the target ICD-11 code in a handful of cases. In about 10% of the codes, we detected potential conflicts, which, even though they did not invalidate the matching with the ICD-11 code, would require a change of code in certain situations (eg, when a specific condition encompassed by a code in one classification is coded differently in the other). This shows that the accompanying coding guidance should be taken into consideration when assessing the alignment between the ICD-10-CM and ICD-11.

The ICD-11 as a replacement for the ICD-10-CM for morbidity coding

One important consideration in changing from one coding system to another is the amount of disruption in coding. Based on the 2016 General Equivalence Maps published by Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services immediately after the transition to the ICD-10-CM, of 14 567 ICD-9-CM codes, only 3533 (24.3%) had an exact match in the ICD-10-CM.18 This is very close to the 23.5% full representation of ICD-10-CM codes by ICD-11 codes without postcoordination found in this study. With postcoordination and some minor enhancements, full representation would further increase to 58.7%. Based on this, moving from the ICD-10-CM to ICD-11 appears less disruptive than moving from the ICD-9-CM to ICD-10-CM. Therefore, before embarking on the development of the ICD-11-CM, serious consideration should be given to using the ICD-11 for morbidity coding. One caveat is that postcoordination has never been used in ICD coding and will have impact on tooling, coder education, and coding variability. In our study, the intercoder agreement for postcoordination is comparable to the agreement for the selection of the main codes. We also show that there is significant variation in coverage among chapters (Tables 1 and 2). Special attention should be paid to chapters with large spread of usage and low coverage (eg, chapter 19 [injury and poisoning]).

Using the ICD-11 for morbidity coding would avoid the cost of maintaining a national extension and potential divergence from the international core. It would also provide an up-to-date medical nomenclature that reflects state-of-the-art biomedical knowledge. Overall, content coverage is only one of the factors in deciding whether the ICD-11 can replace the ICD-10-CM. Other factors such as cost and benefit analysis, resource impact, and burden of implementation are beyond the scope of this study.

Limitations and future work

We recognize the following limitations. Our list of frequently used codes was derived from Medicare claims data and 3 hospitals. Even though the total number of patients covered was substantial, it may not be representative of all healthcare settings. Recoding was done by 2 authors and was not externally validated. Our index terms review was based on conflicts detected by normalized lexical matching which could have false positives and false negatives. The new foundation component of the ICD-11 can confer additional benefits such as easier integration with SNOMED CT (Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms) and other standard terminologies stipulated in the Promoting Interoperability and related initiatives.19–22 In the future, we will investigate how the foundation component in the ICD-11 can help to align the ICD-11 with other terminology standards.

CONCLUSION

Based on the analysis of the 943 most frequently used ICD-10-CM codes covering 60% of patients, 222 (23.5%) codes could be fully represented without postcoordination, 81 (8.6%) codes could be fully represented with postcoordination, the remaining 640 (67.9%) codes could only achieve partial representation. With minor changes to the ICD-11, the proportion that can be fully represented would increase to 58.7%. Even without postcoordination, 23.5% full representation is comparable to the 24.3% of ICD-9-CM codes with exact match in the ICD-10-CM, so migrating from the ICD-10-CM to the ICD-11 is not necessarily more disruptive than from the ICD-9-CM to the ICD-10-CM. Therefore, the ICD-11 (without a CM) should be considered as a candidate to replace the ICD-10-CM for morbidity coding.

FUNDING

This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

KWF, DP, and OB conceived and designed the study. JX and SM-L performed the recoding of International Classification of Diseases–Tenth Revision–Clinical Modification codes and reviewed the coding guidance. KWF performed the data analysis. KWF drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed substantially to its revision.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank James Campbell and Ellen Kerns for providing data from the University of Nebraska Medical Center. The authors thank the National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics for suggesting and promoting research into the feasibility of using International Classification of Diseases–11th Revision for morbidity coding without a U.S. Clinical Modification.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The Medicare claims data are available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Virtual Research Data Center. The International Classification of Diseases–Eleventh Revision recoding results are available as online Supplementary Material.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors do not have competing interests. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health, National Center for Health Statistics, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. History of the development of the ICD. http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/HistoryOfICD.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 2. Gersenovic M. The ICD family of classifications. Methods Inf Med 1995; 34 (1–2): 172–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Assembly Update, 25 May 2019: International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11); 2019. https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/25-05-2019-world-health-assembly-update. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 4. Pocai B. The ICD-11 has been adopted by the World Health Assembly. World Psychiatry 2019; 18 (3): 371–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. ICD-11: a brave attempt at classifying a new world. Lancet 2018; 391 (10139): 2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scientific Data Documentation. International Classification of Diseases - 9 - CM, (1979). https://wonder.cdc.gov/wonder/sci_data/codes/icd9/type_txt/icd9cm.asp. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 7. Cimino JJ. Desiderata for controlled medical vocabularies in the twenty-first century. Methods Inf Med 1998; 37 (4–5): 394–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. ICD-11. International Classification of Disease 11th Revision. The global standard for diagnostic health information. https://icd.who.int/en/. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 9.World Health Organization. ICD-11 Reference Guide. https://icd.who.int/icd11refguide/en/index.html. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 10. Fung KW, Xu J, Bodenreider O.. The new International Classification of Diseases 11th edition: a comparative analysis with ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27 (5): 738–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. Recommendation Letter to Department of Health and Human Services: Preparing for Adoption of ICD-11 as a Mandated U.S. Health Data Standard. 2019. https://ncvhs.hhs.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Recommendation-Letter-Preparing-for-Adoption-of-ICD-11-as-a-Mandated-US-Health-Data-Standard-final.pdf. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 12. Austin JM, Kirley EM, Rosen MA, et al. A comparison of two structured taxonomic strategies in capturing adverse events in U.S. hospitals. Health Serv Res 2019; 54 (3): 613–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). CMS Virtual Research Data Center (VRDC). https://www.resdac.org/cms-virtual-research-data-center-vrdc. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 14.World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics Browser. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 15. Krippendorff K. Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 16. McCray AT, Srinivasan S, Browne AC.. Lexical methods for managing variation in biomedical terminologies. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1994; 235–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.UMLS Reference Manual: SPECIALIST Lexicon and Lexical Tools. Bethesda, MD: National Library of Medicine; 2009. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK9680/. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM and ICD-10 PCS and GEMs Archive. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Coding/ICD10/Archive-ICD-10-CM-ICD-10-PCS-GEMs. Accessed August 2, 2021.

- 19. Mamou M, Rector A, Schulz S, et al. Representing ICD-11 JLMMS using IHTSDO representation formalisms. Stud Health Technol Inform 2016; 228: 431–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rodrigues J-M, Robinson D, Della Mea V, et al. Semantic alignment between ICD-11 and SNOMED CT. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015; 216: 790–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schulz S, et al. What's in a class? Lessons learnt from the ICD - SNOMED CT harmonisation. Stud Health Technol Inform 2014; 205: 1038–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Promoting Interoperability Programs. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/EHRIncentivePrograms/index.html?redirect=/ehrincentiveprograms/. Accessed August 2, 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The Medicare claims data are available through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Virtual Research Data Center. The International Classification of Diseases–Eleventh Revision recoding results are available as online Supplementary Material.