Abstract

Background

This is an update of the review published on the Cochrane Library in 2016, Issue 8. Having cancer may result in extensive emotional, physical and social suffering. Music interventions have been used to alleviate symptoms and treatment side effects in people with cancer. This review includes music interventions defined as music therapy offered by trained music therapists, as well as music medicine, which was defined as listening to pre‐recorded music offered by medical staff.

Objectives

To assess and compare the effects of music therapy and music medicine interventions for psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 3) in the Cochrane Library, MEDLINE via Ovid, Embase via Ovid, CINAHL, PsycINFO, LILACS, Science Citation Index, CancerLit, CAIRSS, Proquest Digital Dissertations, ClinicalTrials.gov, Current Controlled Trials, the RILM Abstracts of Music Literature, http://www.wfmt.info/Musictherapyworld/ and the National Research Register. We searched all databases, except for the last two, from their inception to April 2020; the other two are no longer functional, so we searched them until their termination date. We handsearched music therapy journals, reviewed reference lists and contacted experts. There was no language restriction.

Selection criteria

We included all randomized and quasi‐randomized controlled trials of music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in adults and pediatric patients with cancer. We excluded patients undergoing biopsy and aspiration for diagnostic purposes.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently extracted the data and assessed the risk of bias. Where possible, we presented results in meta‐analyses using mean differences and standardized mean differences. We used post‐test scores. In cases of significant baseline difference, we used change scores. We conducted separate meta‐analyses for studies with adult participants and those with pediatric participants. Primary outcomes of interest included psychological outcomes and physical symptoms and secondary outcomes included physiological responses, physical functioning, anesthetic and analgesic intake, length of hospitalization, social and spiritual support, communication, and quality of life (QoL) . We used GRADE to assess the certainty of the evidence.

Main results

We identified 29 new trials for inclusion in this update. In total, the evidence of this review rests on 81 trials with a total of 5576 participants. Of the 81 trials, 74 trials included adult (N = 5306) and seven trials included pediatric (N = 270) oncology patients. We categorized 38 trials as music therapy trials and 43 as music medicine trials. The interventions were compared to standard care.

Psychological outcomes

The results suggest that music interventions may have a large anxiety‐reducing effect in adults with cancer, with a reported average anxiety reduction of 7.73 units (17 studies, 1381 participants; 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐10.02 to ‐5.44; very low‐certainty evidence) on the Spielberger State Anxiety Inventory scale (range 20 to 80; lower values reflect lower anxiety). Results also suggested a moderately strong, positive impact of music interventions on depression in adults (12 studies, 1021 participants; standardized mean difference (SMD): −0.41, 95% CI −0.67 to −0.15; very low‐certainty evidence). We found no support for an effect of music interventions on mood (SMD 0.47, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.97; 5 studies, 236 participants; very low‐certainty evidence). Music interventions may increase hope in adults with cancer, with a reported average increase of 3.19 units (95% CI 0.12 to 6.25) on the Herth Hope Index (range 12 to 48; higher scores reflect greater hope), but this finding was based on only two studies (N = 53 participants; very low‐certainty evidence).

Physical outcomes

We found a moderate pain‐reducing effect of music interventions (SMD −0.67, 95% CI −1.07 to −0.26; 12 studies, 632 adult participants; very low‐certainty evidence). In addition, music interventions had a small treatment effect on fatigue (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.10; 10 studies, 498 adult participants; low‐certainty evidence).

The results suggest a large effect of music interventions on adult participants' QoL, but the results were highly inconsistent across studies, and the pooled effect size was accompanied by a large confidence interval (SMD 0.88, 95% CI −0.31 to 2.08; 7 studies, 573 participants; evidence is very uncertain). Removal of studies that used improper randomization methods resulted in a moderate effect size that was less heterogeneous (SMD 0.47, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.88, P = 0.02, I2 = 56%).

A small number of trials included pediatric oncology participants. The findings suggest that music interventions may reduce anxiety but this finding was based on only two studies (SMD −0.94, 95% CI −1.9 to 0.03; very low‐certainty evidence). Due to the small number of studies, we could not draw conclusions regarding the effects of music interventions on mood, depression, QoL, fatigue or pain in pediatric participants with cancer.

The majority of studies included in this review update presented a high risk of bias, and therefore the overall certainty of the evidence is low. For several outcomes (i.e. anxiety, depression, pain, fatigue, and QoL) the beneficial treatment effects were consistent across studies for music therapy interventions delivered by music therapists. In contrast, music medicine interventions resulted in inconsistent treatment effects across studies for these outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

This systematic review indicates that music interventions compared to standard care may have beneficial effects on anxiety, depression, hope, pain, and fatigue in adults with cancer. The results of two trials suggest that music interventions may have a beneficial effect on anxiety in children with cancer. Too few trials with pediatric participants were included to draw conclusions about the treatment benefits of music for other outcomes. For several outcomes, music therapy interventions delivered by a trained music therapist led to consistent results across studies and this was not the case for music medicine interventions. Moreover, evidence of effect was found for music therapy interventions for QoL and fatigue but not for music medicine interventions. Most trials were at high risk of bias and low or very low certainty of evidence; therefore, these results need to be interpreted with caution.

Plain language summary

Can music interventions benefit people with cancer?

The issue Cancer may result in extensive emotional, physical and social suffering. Music therapy and music medicine interventions have been used to alleviate symptoms and treatment side effects and address psychosocial needs in people with cancer. In music medicine interventions, patients simply listen to pre‐recorded music that is offered by a medical professional. Music therapy requires the implementation of a music intervention by a trained music therapist, the presence of a therapeutic process and the use of personally tailored music experiences.

The aim of the review This review is an update of a previous Cochrane review from 2016, which included 52 studies. For this review update, we searched for additional trials studying the effect of music interventions on psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer. We searched for studies up to April 2020.

What are the main findings? We identified 29 new studies, so the evidence in this review update now rests on 81 studies with 5576 participants. Of the 81 studies, 74 trials included adults and 7 included children.The findings suggest that music therapy and music medicine interventions may have a beneficial effect on anxiety, depression, hope, pain, fatigue, heart rate and blood pressure in adults with cancer. Music therapy but not music medicine interventions may improve adult patients' quality of life and levels of fatigue. We did not find evidence that music interventions improve mood, distress or physical functioning, but only a few trials studied these outcomes. We could not draw any conclusions about the effect of music interventions on immunologic functioning, resilience, spiritual well‐being or communication outcomes in adults because there were not enough trials looking at these aspects. Due to the small number of trials, we could not draw conclusions for children. Therefore, more research is needed.

Overall, the treatment benefits of music therapy interventions were more consistent across trials than those of music medicine interventions, leading to greater confidence in the treatment impact of music therapy interventions delivered by a trained music therapist.

No adverse effects of music interventions were reported.

Quality of the evidence Most trials were at high risk of bias, so these results need to be interpreted with caution. We did not identify any conflicts of interests in the included studies.

What are the conclusions? We conclude that music interventions may have beneficial effects on anxiety, depression, hope, pain, and fatigue in adults with cancer. Furthermore, music may have a small positive effect on heart rate and blood pressure. Reduction of anxiety, depression, fatigue and pain are important outcomes for people with cancer, as they have an impact on health and overall quality of life.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

The lifetime risk of developing any type of cancer is 40% for men and 38% for women (Howlader 2019), and a diagnosis of cancer may result in extensive emotional, physical and social suffering. Many symptoms and treatment side effects have an impact on cancer patients' physical well‐being and quality of life (QoL), including appetite disturbance, difficulty swallowing, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, dyspnea or difficulty breathing, fatigue, insomnia, muscle weakness and numbness (King 2003). In addition, study findings clearly indicate that people with cancer experience elevated levels of psychological distress and depression in response to diagnosis and treatment (Massie 2004; Norton 2004; Parle 1996; Raison 2003; Sellick 1999; Van't Spijker 1997). The actual experience of chemotherapy‐induced side effects, such as nausea and vomiting, and their influence on psychological well‐being varies widely in patients receiving the same cytotoxic agents. This suggests that non‐pharmacological factors possibly play an important role in how patients experience or interpret physical symptoms during the treatment phase (Montgomery 2000; Thune‐Boyle 2006). It is therefore important that cancer care incorporates services that help meet patients' psychological, social and spiritual needs.

Description of the intervention

The use of music in cancer care can be situated along a continuum of care, namely from music listening initiated by patients, to pre‐recorded music offered by medical personnel, to music psychotherapy interventions offered by a trained music therapist. Therefore, when examining the efficacy of music interventions in people with cancer, it is important to make a clear distinction between music interventions administered by medical or healthcare professionals (music medicine) and those implemented by trained music therapists (music therapy). A substantive body of evidence suggests that music therapy interventions provided by music therapists are more effective than music medicine interventions for a wide variety of outcomes (Dileo 2005). This difference might be attributed to the fact that music therapists individualize their interventions to meet patients' specific needs, more actively engage the patients in music‐making, and employ a systematic therapeutic process including assessment, treatment and evaluation. Dileo 1999 categorizes interventions as music medicine when medical personnel offer pre‐recorded music for passive listening. For example, they may offer people a compact disc (CD) for relaxation or distraction; however, no systematic therapeutic process is present, nor is there a systematic assessment of the elements and suitability of the music stimulus. In contrast, music therapy requires the implementation of a music intervention by a trained music therapist, the presence of a therapeutic process and the use of personally tailored music experiences.

These tailored music experiences include:

listening to live, improvised or pre‐recorded music;

performing music on an instrument;

improvising music spontaneously using voice, instruments or both;

composing music;

combining music with other therapeutic modalities (e.g. movement, imagery, art) (Dileo 2007).

How the intervention might work

Music interventions have been used in different medical fields to meet patients' psychological, physical, social and spiritual needs. Research on the effects of music and music therapy for medical patients has burgeoned over the past 20 years, examining a variety of outcome measures in a wide range of specialty areas (Dileo 2005). For both adult and pediatric cancer patients, music has been used to decrease anxiety prior to or during surgical procedures (Alam 2016; Burns 1999; Haun 2001), to decrease stress during chemotherapy or radiation therapy (Bradt 2015; Bro 2019; Clark 2006), to lessen treatment side effects (Bozcuk 2006; Ezzone 1998; Frank 1985), to improve mood (Barrera 2002; Burns 2001a; Cassileth 2003), to enhance pain management (Akombo 2006; Arruda 2016; Beck 1989; Verstegen 2018), to improve immune system functioning (Burns 2001a), and to improve quality of life (QoL) (Burns 2001a; Hilliard 2003; Porter 2018).

There are inherent elements of music — such as rhythm and tempo, mode, pitch, timbre, melody and harmony — that are known to influence physiological and psycho‐emotional responses in humans. For example, music has been found to arouse memory and association, stimulate imagery, evoke emotions, facilitate social interaction, and promote relaxation and distraction (Dileo 2006). In cancer settings, music therapists conduct ongoing assessments and utilize various individualized interventions in people with cancer and their families, including pertinent elements of music within the context of therapeutic relationships, to address prevailing biopsychosocial and spiritual issues, symptoms and needs (Magill 2009; McClean 2012). The following music therapy interventions are common: use of songs (singing, song writing, and lyric analysis); music improvisation (instrumental and vocal), music and imagery, music‐based reminiscence and life review, chanting and toning, music‐based relaxation, and instrumental participation (O'Callaghan 2015). Based on patient preferences and assessment outcomes, music therapists adapt and modify music interventions to address symptoms and areas of difficulty; they utilize music and verbal strategies to provide opportunities for expression and communication, reminiscence, the processing of thoughts and emotions and improvement of symptom management (Magill 2011). Therapist‐supported music therapy environments often provide the space and time through which patients and families may experience social connection, improve self fulfilment and acquire effective coping strategies (Magill 2015).

Why it is important to do this review

Several research studies on the use of music with cancer patients have reported positive results (Beck 1989; Bradt 2015; Cassileth 2003; Harper 2001; Hilliard 2003; Robb 2008). The majority of these studies, however, are compromised by small sample size and lack of statistical power. In addition, differences in factors such as methods of interventions and type and intensity of treatment have led to varying results. A systematic review is needed to more accurately gauge the efficacy of music interventions in cancer patients as well as to identify variables that may moderate its effects.

Objectives

To assess and compare the effects of music therapy and music medicine interventions for psychological and physical outcomes in people with cancer.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and studies with quasi‐randomized methods of treatment allocation (e.g. alternate allocation of treatments) were eligible for inclusion.

Types of participants

This review included participants diagnosed with any type of cancer. We included studies that included a few participants (< 10% of total sample size) with non‐cancer diagnoses (e.g. aplastic anemia). There were no restrictions as to age, sex, ethnicity or type of setting. We did exclude participants undergoing biopsy, bone marrow biopsy and aspiration for diagnostic purposes. This review did not include studies with cancer survivors.

Types of interventions

The review included all trials comparing standard treatment plus music therapy or music medicine interventions (as defined in the Background; Description of the intervention) with:

standard care alone;

standard care plus alternative intervention (e.g. music therapy versus music medicine);

standard care plus placebo.

Placebo treatment can involve the use of headphones for the participant without provision of music stimuli or with another type of auditory stimulus (e.g. audiobooks, white noise (hiss), pink noise (sound of ocean waves) or nature sounds).

Music therapy and music medicine interventions were pooled in the same analysis but, where possible, subgroup analyses were conducted to compare the effects of music therapy and music medicine interventions as outlined in the Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Psychological outcomes (e.g. state anxiety, depression, distress, mood, hope, resilience)

Physical symptoms (e.g. fatigue, pain)

Secondary outcomes

Physiological outcomes (e.g. heart rate, respiratory rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, oxygen saturation, immune system functioning)

Physical functioning

Anesthetic and analgesic intake

Length of hospitalization and recovery time

Social and spiritual support (e.g. spiritual well‐being, social support)

Communication (e.g. verbalization, facial affect, gestures)

Quality of life (QoL)

We presented a 'Table 1 and Table 2 reporting the following outcomes: anxiety, depression, mood, hope, pain, fatigue, and QoL.

Summary of findings 1. Music intervention plus standard care compared to standard care alone for improving psychological and physical outcomes in adult cancer patients.

| Music intervention plus standard care compared to standard care alone for improving psychological and physical outcomes in adult cancer patients | ||||

| Patient or population: adult cancer patients (≥ 18 years) Setting: inpatient and outpatient cancer care Intervention: music intervention (music therapy or music medicine) plus standard care Comparison: standard care alone (i.e. usual cancer treatment as per the site's standard care protocol) | ||||

| Outcomes* |

Illustrative Comparative Risk

(95% CI) __________________ Corresponding Risk __________________ Music intervention |

№ of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Anxiety assessed with: Spielberger State Anxiety Index Scale (STAI) Score range: 20 to 80. A lower score represents less anxiety. Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean anxiety in the music intervention group was 7.73 units less (10.02 less to 5.44 less) than in the standard care group. | 1381 (17 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 | Music intervention may result in a large reduction in anxiety. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Depression Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean depression in the music intervention group was 0.41 standard deviations less (0.67 worse to 0.15 worse) than in the standard care group | 1021 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 3 | Music intervention may result in a small to moderate reduction of depression. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Mood Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean mood in the music intervention group was 0.53 standard deviations better (0.03 worse to 1.11 better) than in the standard care group | 221 (4 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 4 | Music interventions may result in a moderate improvement in mood. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Hope Score range: 12 to 48. A higher score represents greater hope. Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean hope in the music intervention group was 3.19 units more (0.12 more to 6.25 more) than in the standard care group | 53 (2 RCTS |

⊕ ⊝ ⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 7 |

Music intervention may result in a large increase in hope. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Pain Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean pain in the intervention group was 0.67 standard deviations less (1.07 less to 0.26 less) than in the standard care group | 632 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 5 | Music interventions may result in a moderate to large improvement in pain. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| Fatigue Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean fatigue in the music intervention group was 0.28 standard deviations less (0.46 less to 0.01 less) than in the standard care group | 498 (10 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW 1 | Music intervention may result in a slight reduction in fatigue. |

| Quality of Life Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean quality of life in the music intervention group was 0.88 standard deviations more (0.31 less to 2.08 more) than in the standard care group | 573 (7 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 6 | Music interventions may result in a large improvement in quality of life. However, the evidence is very uncertain. |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1 Downgraded two levels for high risk of bias. The majority of the trials were at high risk of bias because participants could not be blinded to the music intervention and outcome was measured using self‐report.

2 Downgraded two levels for very serious inconsistency across studies as evidenced by I2 = 93%.

3 Downgraded one level for serious inconsistency across studies as evidenced by I2 = 72%.

4 Downgraded one level for serious inconsistency across trials as evidenced by I2 = 70%.

5 Downgraded two levels for very serious inconsistency across trials as evidenced by I2 = 81%.

6 Downgraded two levels for very serious inconsistency across trials as evidenced by I2 = 97%.

7 Downgraded two level s for imprecision due to a small number of participants.

Summary of findings 2. Music intervention plus standard care compared to standard care alone for improving psychological and physical outcomes in paediatric cancer patients.

| Music intervention plus standard care compared to standard care alone for improving psychological and physical outcomes in pediatriccancer patients | ||||

| Patient or population: pediatric cancer patients (< 18 years) Setting: inpatient and outpatient cancer care Intervention: music interventions (music therapy or music medicine) plus standard care Comparison: standard care alone (i.e. usual cancer treatment as per the site's standard care protocol) | ||||

| Outcomes |

Illustrative comparative risk (95% CI) ____________________ Corresponding risk ____________________ Music intervention |

№ of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments |

| Anxiety (STAI) The score: 20 to 80. A lower score represents less anxiety. Follow‐up: immediately post‐intervention |

The mean anxiety in the music intervention group was 0.94 standard lower (1.9 lower to 0.03 higher) | 79 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW 1 2 3 | Music intervention may result in a large reduction in anxiety. |

| Depression | not estimable | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Mood | not estimable | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Pain assessed with: 0 to 10 NRS. A higher score represents more pain | Listening to pre‐recorded music resulted in less pain during and after lumbar puncture (during mean: 2.35, SD 1.9; after mean: 1.2, SD 1.36) than standard care (during mean: 5.65, SD 2.5; after mean: 3.0, SD 2.0 ). | 40 (1 RCT) | ⊕ ⊝ ⊝ ⊝ LOW 1 3 |

|

| Fatigue | not estimable | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Quality of Life | not estimable | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| Hope | not estimable | (0 studies) | ‐ | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||

1 Downgraded two levels for high risk of bias. These trials were at high risk of bias because participants could not be blinded to the music intervention and outcome was measured using self‐report.

2 Downgraded one level for serious inconsistency across studies as evidenced by I2 = 76%.

3 Downgraded two levels for imprecision due to a small number of participants.

Search methods for identification of studies

There were no language restrictions for either searching or trial inclusion.

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases and trials registers for the updated review:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 3), in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 1);

MEDLINE via Ovid (January 2016 to March, week 3, 2020) (Appendix 2);

Embase via Ovid (January 2016 to 2020, week 13) (Appendix 3);

CINAHL (EbscoHost)(January 2016 to April 16 2020) (Appendix 4);

PsycINFO (OvidSp) (January 2016 to April 16 2020) (Appendix 5);

LILACS (Virtual Health Library) (2016 to April 2020) (Appendix 6).

The Science Citation Index (ISI) (2016 to April 2020) (Appendix 7).

CancerLit (2016 to 2003) (http://www.cancer.gov) (Appendix 8).

CAIRSS for Music (2016 to April 2020) (http://ucairss.utsa.edu/) (Appendix 9).

Proquest Digital Dissertations (Proquest) (to April 2020) (Appendix 10).

ClinicalTrials.gov (http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/) (to April 2020) (Appendix 11).

Current Controlled Trials (http://www.controlled-trials.com/) (to April 2020) (Appendix 12).

National Research Register (http://www.update-software.com/National/) (inception to September 2010; the NRR is no longer active) (Appendix 13).

http://www.wfmt.info/Musictherapyworld/ (database is no longer functional) (to March 2008) .

RILM Abstracts of Music Literature (EbscoHost) (to April 2020) (Appendix 14).

Searching other resources

We handsearched the following journals from first available date to December 2020:

Australian Journal of Music Therapy.

Australian Music Therapy Association Bulletin.

Canadian Journal of Music Therapy.

International Journal of the Arts in Medicine.

Journal of Music Therapy.

Musik‐,Tanz‐, und Kunsttherapie (Journal for Art Therapies in Education, Welfare and Health Care).

Musiktherapeutische Umschau.

Music Therapy.

Music Therapy Perspectives.

Nordic Journal of Music Therapy;

Music Therapy Today (online journal of music therapy).

Voices (online international journal of music therapy).

New Zealand Journal of Music Therapy.

Arts in Psychotherapy.

British Journal of Music Therapy.

Music and Medicine.

Approaches.

In an effort to identify further published, unpublished and ongoing trials, we searched the bibliographies of relevant trials and reviews, contacted experts in the field, and searched available proceedings of music therapy conferences. We consulted music therapy association websites to help identify music therapy practitioners and conference information (e.g. the American Music Therapy Association at www.musictherapy.org and the British Association for Music Therapy at http://www.bamt.org). We also handsearched the website of the Deutsches Zentrum fur Musiktherapieforschung (www.dzm-heidelberg.de/forschung/publikationen/) and the research pages of the PhD programs that are listed on the website of the European Music Therapy Confederation (emtc-eu.com/music-therapy-research/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We divided the responsibility of the searches, as outlined in the search strategy, amongst JBr, JBi and KMC. JBr, JBi, and KMC scanned titles and abstracts of each record retrieved from the search and deleted obviously irrelevant references. When we could not reject a title or abstract with certainty, we consulted the other review author. We used an inclusion criteria form to assess the trial's eligibility for inclusion (Appendix 15). We kept a record of all excluded trials that initially appeared eligible and the reason for exclusion.

Data extraction and management

JBi and KMC independently extracted data from the selected trials using a standardized coding form. We discussed differences in data extraction until reaching a consensus. We extracted the following data.

General information

Author

Year of publication

Title

Journal (title, volume, pages)

If unpublished, source

Duplicate publications

Country

Language of publication

Intervention information

Type of intervention (e.g. singing, song‐writing, music listening, music improvisation)

Music selection (detailed information on music selection in case of music listening)

Music preference (patient‐preferred versus researcher‐selected in case of music listening)

Level of intervention (music therapy versus music medicine, as defined by the authors in the Background ; Description of the intervention)

Length of intervention

Frequency of intervention

Comparison intervention

Participant information

Total sample size

Number in experimental group

Number in control group

Sex

Age

Ethnicity

Diagnosis

Illness stage

Setting

Inclusion criteria

Outcomes

We extracted pre‐test means, post‐test means, standard deviations and sample sizes for the treatment group and the control group for the following outcomes (if applicable). For some trials, only change scores, instead of post‐test scores, were available.

Psychological outcomes (e.g. depression, anxiety, anger, hopelessness, helplessness)

Physical symptoms (e.g. fatigue, nausea, pain)

Physiological outcomes (e.g. heart rate, respiratory rate, immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels)

Social and spiritual support (e.g. family support, spirituality, social activity, isolation)

Communication (e.g. verbalization, facial affect, gestures)

Quality of life

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (JBr and CD) assessed all included trials for risk of bias for the original review. New studies included in this update were assessed for risk of bias by CD, JBi and KMC (two reviewers per study). All authors were blinded to each other's assessments. JBr reviewed the reviewer authors' decisions. When there was no consensus between the two reviewer authors, JBr provided input to reach consensus. We resolved any disagreements by discussion. The authors used the following criteria for quality assessment.

Random sequence generation

Low risk

Unclear risk

High risk

We rated trials to be at low risk for random sequence generation if every participant had an equal chance to be selected for either condition, and the investigator was unable to predict which treatment the participant would be assigned to. Use of date of birth, date of admission or alternation resulted in a judgement of high risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

-

Low risk methods to conceal allocation include:

central randomization;

serially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes;

other descriptions with convincing concealment.

Unclear risk ‐ authors did not adequately report on method of concealment

High risk (e.g. trials used alternation methods)

Blinding of participants and personnel

Low risk

Unclear risk

High risk

Since participants cannot be blinded in a music intervention trial, we did not downgrade studies for not blinding the participants. As for personnel, in music therapy studies, music therapists cannot be blinded because they are actively making music with the participants. In contrast, in music medicine studies, blinding of personnel is possible by providing control group participants with headphones but no music (e.g. blank CD). Therefore, downgrading for not blinding personnel was only applied in studies that used listening to pre‐recorded music.

Blinding of outcome assessors

Low risk

Unclear risk

High risk

When the study included no objective outcomes, we noted this in the Characteristics of included studies table, and we rated the trial as being at low risk of bias for outcome assessment of objective outcomes. The majority of the studies used self‐report measures for subjective outcomes. We rated these studies as being at high risk of bias for subjective outcomes, unless study participants were blinded to the study hypothesis (for comparative studies).

Incomplete outcome data

We recorded the proportion of participants whose outcomes were analyzed. We coded loss to follow‐up for each outcome as:

low risk: if fewer than 20% of participants were lost to follow‐up and reasons for loss to follow‐up were similar in both treatment arms;

unclear risk: if loss to follow‐up was not reported;

high risk: if more than 20% of participants were lost to follow‐up or reasons for loss to follow‐up differed between treatment arms.

Selective reporting

Low risk: reports of the study were free from suggestions of selective outcome reporting

Unclear risk

High risk: reports of the study suggested selective outcome reporting

Other sources of bias

Low risk

Unclear risk

High risk

We considered information on potential financial conflicts of interest to be a possible source of additional bias.

The above criteria were used to give each article an overall quality rating (based on section 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions;Higgins 2021).

Low risk of bias ‐ all criteria met.

Moderate risk of bias ‐ one or more of the criteria only partly met.

High risk of bias ‐ one or more criteria not met.

Studies were not excluded based on a low quality score. We planned to use the overall quality assessment rating for sensitivity analysis. However, since most trials were at high risk of bias, we could not carry out this analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

We presented all outcomes in this review as continuous variables. We calculated standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for outcome measures using results from different scales. When there were sufficient data available from various studies using the same measurement instrument, we computed a mean difference (MD) with 95% CI.

For cross‐over studies, if no carry‐over effects or period effects were apparent, we used data from the paired analyses in the meta‐analysis using a generic inverse‐variance approach. If paired analyses were not reported, we approximated the mean difference or standardized mean difference using methods outlined in Elbourne 2002. If carry‐over or period effects were present, the cross‐over trial were excluded from the meta‐analysis.

Unit of analysis issues

In all studies included in this review, participants were individually randomized to the intervention or the standard care control group. Post‐test values or change values on a single measurement for each outcome from each participant were collected and analyzed.

Dealing with missing data

We did not impute missing outcome data. We analyzed data on an endpoint basis, including only participants for whom final data point measurement was available (available case analysis). We did not assume that participants who dropped out after randomization had a negative outcome.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We investigated heterogeneity using visual inspection of the forest plots as well as the I2 statistic (Higgins 2002).

Assessment of reporting biases

We tested for publication bias visually in the form of funnel plots (Higgins 2021).

Data synthesis

We presented all outcomes in this review as continuous variables. We calculated standardized mean differences (SMD) for outcome measures using results from different scales. We used mean differences (MD) for results using the same scales. We anticipated that some individual trials would have used final scores and others change scores and even analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) in their statistical analyses of the results. We combined these different types of analyses as MDs. We calculated pooled estimates using the more conservative random‐effects model. We calculated 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each effect size estimate. We interpreted the magnitude of the SMDs using the interpretation guidelines put forth by Cohen 1988. Cohen suggested that an effect size of 0.2 be considered a small effect, an effect size of 0.5 medium, and an effect size of 0.8 large.

We made the following treatment comparisons in meta‐analyses:

Music interventions plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults.

Music interventions plus standard care versus standard care alone in children.

Music interventions plus standard care versus standard care plus placebo control in children.

Music therapy plus standard care versus music medicine plus standard care in adults.

In the update of this review, we separated pediatric studies (participants < 18 years of age) from adult clinical trials for data synthesis. In prior versions of this review, these studies were combined in meta‐analyses.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted the following subgroup analyses within the music interventions plus standard care versus standard care alone comparison for outcomes with a sufficient number of available studies.

Music medicine versus music therapy.

Type of intervention (e.g. music listening alone versus music‐guided relaxation).

Music preference (patient‐preferred music versus researcher‐selected music).

We planned the following subgroup analyses a priori, but we could not carry these out because of insufficient numbers of trials per outcome for age subgroup analysis and because no separate data were available according to stage of illness.

Different age groups.

Stages of illness.

We conducted subgroup analyses as described by Deeks 2001 and recommended in section 10.10 of Higgins 2021.

Sensitivity analysis

We examined the impact of sequence generation by comparing the results of including and excluding trials that used inadequate or unclear randomization methods. We also examined whether the inclusion of studies with non‐cancer participants (< 10%) had an impact on the pooled effect size.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We presented the overall certainty of the evidence for each outcome (see Types of outcome measures) according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach, which takes into account issues not only related to internal validity (risk of bias, inconsistency, imprecision, publication bias) but also to external validity such as directness of results (Langendam 2013; Schünemann 2011). We presented a summary of findings table (see Table 1) based on the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021) and using GRADEpro 2020. We used the GRADE checklist and GRADE Working Group certainty of evidence definitions (Meader 2014). We downgraded the evidence from 'high' certainty by one level for serious (or by two for very serious) concerns study for limitations for each outcome:

High‐certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate‐certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low‐certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low‐certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

For the original review, the database searches and handsearching of conference proceedings, journals and reference lists resulted in 773 unique citations. One review author (JBr) and a research assistant examined the titles and abstracts and identified 101 reports as potentially relevant, which we retrieved for further assessment. One review author (JBr) and a research assistant then independently screened them. We included 30 trials, reported in 36 records, in the original review. Where necessary, we contacted principal investigators to obtain additional details on trials and data.

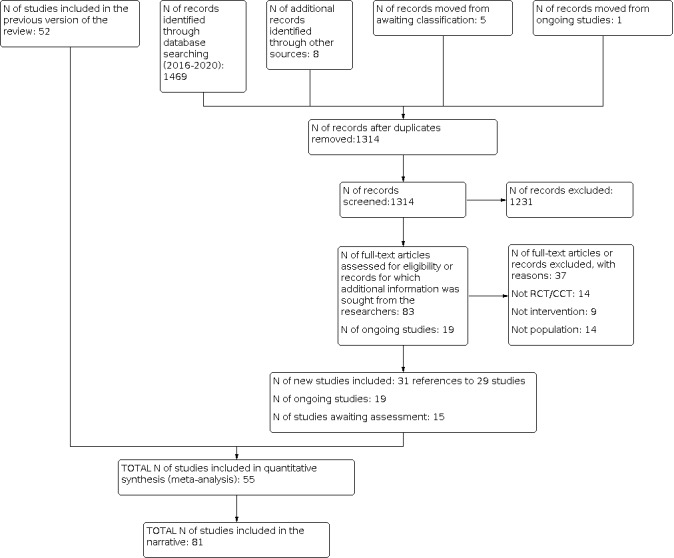

The 2016 update of the search resulted in 1187 unique citations. Two review authors (JBr and AT) and one research assistant examined the titles and abstracts, retrieving full‐text articles, where necessary. This resulted in the addition of 25 references reporting on 22 trials (Figure 1) and three new ongoing trials (Mondanaro 2020; NCT02583139; NCT0258312).

1.

Study flow diagram.

The 2020 update of the search resulted in 1314 unique citations. Two review authors (JBi and KMC) examined the titles and abstracts, retrieving full‐text articles, where necessary. A research assistant helped with article retrieval. This resulted in the addition of 31 references reporting on 29 trials (Figure 1). In addition, we identified 19 ongoing trials (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) and 15 trials awaiting assessment (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) including Mondanaro 2020, which was an ongoing study in the 2016 update and has since been published.

Included studies

We included a total of 81 trials (74 trials with 5306 adult participants and seven trials focused on 270 pediatric oncology participants). Twenty‐six trials included participants who underwent chemotherapy or radiation therapy (Alcantara‐Silva 2018; Bradt 2015; Bro 2019; Bulfone 2009; Burns 2018; Burrai 2014; Cai 2001; Chen 2013; Chen 2020; Clark 2006; Ferrer 2005; Firmeza 2017; Gimeno 2008; Hunter 2020; Jin 2011; Karadag 2019; Lin 2011; Moradian 2015; O'Callaghan 2012; Romito 2013; Rossetti 2017; Smith 2001; Straw 1991; Tuinmann 2017; Xie 2001; Zhao 2008), 23 trials examined the effects of music during procedures or surgery (Alam 2016; Bates 2017; Binns‐Turner 2008; Burns 2009; Cassileth 2003; Danhauer 2010; Doro 2017; Fredenburg 2014a; Fredenburg 2014b; Kwekkeboom 2003; Li 2004; Li 2012; Mou 2020; Pedersen 2020; Palmer 2015; Pinto 2012; Ratcliff 2014; Rosenow 2014; Vachiramon 2013; Wang 2015; Wren 2019; Yates 2015; Zhou 2015), and 25 trials included general cancer participants (Arruda 2016; Beck 1989; Bieligmeyer 2018; Burns 2001a; Burns 2008; Chen 2004; Chen 2018; Cook 2013; Hanser 2006; Harper 2001; Hilliard 2003; Horne‐Thompson 2008; Huang 2006; Jasemi 2016; Keenan 2017; Letwin 2017; Liao 2013; Porter 2018; Ramirez 2018; Reimnitz 2018; Shaban 2006; Verstegen 2016; Verstegen 2018; Wan 2009; Warth 2015). Seven trials (N = 270) examined music interventions in pediatric participants (Bufalini 2009; Burns 2009; Duocastella 1999; Nguyen 2010; Robb 2008; Robb 2014; Robb 2017). Four trials included a few participants (< 10% of total sample size) who had a hematological disease but did not have a cancer diagnosis (e.g. aplastic anemia) (Horne‐Thompson 2008; Porter 2018; Reimnitz 2018; Verstegen 2018).

This review included 3238 adult females and 1809 adult males. The pediatric trials included 103 females and 144 males. Five trials did not provide information on the distribution between sexes (Danhauer 2010; Jin 2011; Robb 2008; Shaban 2006; Xie 2001). The average age of the participants was 54.72 years for adult trials and 11.12 years for pediatric trials.

Thirty‐one studies did not report on the ethnicity of the participants (Alam 2016; Arruda 2016; Bieligmeyer 2018; Bro 2019; Burns 2001a; Burns 2008; Burrai 2014; Cassileth 2003; Chen 2013; Chen 2018; Chen 2020; Cook 2013; Doro 2017; Duocastella 1999; Ferrer 2005; Firmeza 2017; Horne‐Thompson 2008; Jasemi 2016; Karadag 2019; Letwin 2017; Lin 2011; Moradian 2015; Mou 2020; O'Callaghan 2012; Pedersen 2020; Robb 2008; Romito 2013; Straw 1991; Vachiramon 2013; Wang 2015; Zhou 2015). For trials that did provide information on ethnicity, the distribution was as follows: 56% white, 25% Asian, 10% black, 6% Latino, and 3% other.

The trials took place in 13 different countries: the United States (Alam 2016; Bates 2017; Bradt 2015; Burns 2018; Beck 1989; Binns‐Turner 2008; Burns 2001a; Burns 2008; Burns 2009; Cassileth 2003; Clark 2006; Cook 2013; Danhauer 2010; Ferrer 2005; Fredenburg 2014a; Fredenburg 2014b; Hanser 2006; Harper 2001; Hilliard 2003; Hunter 2020; Keenan 2017; Kwekkeboom 2003; Letwin 2017; Gimeno 2008; Palmer 2015; Ratcliff 2014; Reimnitz 2018; Robb 2008; Robb 2014; Robb 2017; Rosenow 2014; Rossetti 2017; Smith 2001; Straw 1991; Vachiramon 2013; Verstegen 2016; Verstegen 2018; Wren 2019; Yates 2015), China (Cai 2001; Chen 2004; Chen 2020; Jin 2011; Li 2004; Li 2012; Liao 2013; Mou 2020; Wan 2009; Xie 2001; Zhao 2008), Denmark (Bro 2019; Pedersen 2020), Germany (Bieligmeyer 2018; Tuinmann 2017; Warth 2015), Italy (Bufalini 2009; Bulfone 2009), Iran (Jasemi 2016; Moradian 2015; Shaban 2006), Ireland (Porter 2018), Spain (Duocastella 1999; Ramirez 2018), Taiwan (Chen 2013; Chen 2018; Huang 2006; Lin 2011; Wang 2015; Zhou 2015), Brazil (Alcantara‐Silva 2018; Arruda 2016; Doro 2017; Firmeza 2017; Pinto 2012), Australia (Horne‐Thompson 2008; O'Callaghan 2012), Turkey (Karadag 2019), and Vietnam (Nguyen 2010). Trial sample size ranged from 8 to 260 participants.

We classified 39 trials as music therapy studies (Alcantara‐Silva 2018; Bates 2017; Bieligmeyer 2018; Bradt 2015; Bufalini 2009; Burns 2001a; Burns 2008; Burns 2009; Burns 2018; Cassileth 2003; Clark 2006; Cook 2013; Doro 2017; Duocastella 1999; Ferrer 2005; Fredenburg 2014a; Fredenburg 2014b; Hanser 2006; Hilliard 2003; Horne‐Thompson 2008; Letwin 2017; Gimeno 2008; Palmer 2015; Porter 2018; Ramirez 2018; Ratcliff 2014; Reimnitz 2018; Robb 2008; Robb 2014; Robb 2017; Romito 2013; Rosenow 2014; Rossetti 2017; Stordahl 2009; Tuinmann 2017; Verstegen 2016 ; Verstegen 2018; Warth 2015; Yates 2015). Of these trials, ten used interactive music‐making with the participants, five used music‐guided imagery, three used music‐guided relaxation, 10 used live patient‐selected music performed by the music therapist, two used music listening accompanied by processing of emotions evoked by the music, five studies used a combination of interactive music making and listening to live music, one study used vibro‐acoustic therapy, and two used music video‐making. We classified 43 trials as music medicine studies (Alam 2016; Arruda 2016; Beck 1989; Binns‐Turner 2008; Bro 2019; Bulfone 2009; Burrai 2014; Cai 2001; Chen 2004; Chen 2013; Chen 2018; Chen 2020; Danhauer 2010; Firmeza 2017; Harper 2001; Huang 2006; Hunter 2020; Jasemi 2016; Jin 2011; Karadag 2019; Keenan 2017; Kwekkeboom 2003; Li 2004; Li 2012; Liao 2013; Lin 2011; Moradian 2015; Mou 2020; Nguyen 2010; O'Callaghan 2012; Pedersen 2020; Pinto 2012; Shaban 2006; Smith 2001; Straw 1991; Vachiramon 2013; Wan 2009; Wang 2015; Wren 2019; Xie 2001; Zhao 2008; Zhou 2015), as defined by the authors in the background section, and used listening to pre‐recorded music as the intervention.

Frequency and duration of treatment sessions greatly varied among the trials. The total number of sessions ranged from 1 to 40 (e.g. multiple music listening sessions per day for length of hospital stay). Most sessions lasted 30 to 45 minutes. We reported details on the frequency and duration of sessions for each trial in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Seventy‐eight trials used parallel‐group designs, whereas three trials used a cross‐over design (Bradt 2015; Beck 1989; Gimeno 2008). Not all trials measured all outcomes identified for this review.

We provided details of the included trials in the review in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Excluded studies

In the original review, 27 of the 101 reports that we retrieved for further assessment were assessed not to be outcome research studies. We identified 38 experimental research studies that appeared eligible for inclusion. However, we excluded these after closer examination or after receiving additional information from the principal investigators. Reasons for exclusions were: not a randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trial (29 studies); insufficient data reporting (2 studies); unacceptable methodological quality (3 studies); not a music intervention (1 study); not exclusively cancer participants (1 study); and article could not be located (2 studies).

For the 2016 update, we retrieved 94 reports for further assessment. We excluded 60 studies for the following reasons: not a randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trial (36 studies), insufficient data reporting (2 studies), not a music intervention (12 studies), not population of interest (8 studies), use of healthy controls (1 study), and use of non‐standardized measurement tools (1 study).

For the current update, we retrieved 83 reports for further assessment. We excluded 37 studies for the following reasons: not a randomized or quasi‐randomized controlled trial (14 studies), not a music intervention (9 studies), and not population of interest (14 studies).

For studies with insufficient data reporting or those that could not be located, we attempted to contact the authors on multiple occasions.

Details about reasons for exclusion are provided in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Risk of bias in included studies

We detailed the risk of bias for each trial in the risk of bias tables included in the Characteristics of included studies table and the risk of bias summary (Figure 2). In addition, readers can consult an overall assessment of risk of bias in Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

We included 61 trials that used appropriate methods of randomization (e.g. computer‐generated table of random numbers, drawing of lots, coin flip), nine trials that used systematic methods of treatment allocation (e.g. alternate group assignment, date of birth), and 11 trials that reported using randomization but failed to state the randomization method.

Thirty‐three trials concealed allocation, whereas 16 trials did not. For the remainder of the trials, authors did not mention allocation concealment.

Blinding

Twenty‐five trials included objective outcomes, but only seven of them reported blinding of the outcome assessors. For 11 trials, the use of blinding was unclear (Bro 2019; Burrai 2014; Chen 2004; Chen 2020; Ferrer 2005; Firmeza 2017; Jin 2011; Palmer 2015; Ramirez 2018; Tuinmann 2017; Wren 2019). The other trials did not use blinding. The majority of the trials included subjective outcomes only. It is important to point out that blinding of outcome assessors is not possible in the case of self‐report measurement tools for subjective outcomes (e.g. STAI; Spielberger 1983) unless the participants are blinded to the intervention. Blinding of the participants is often not feasible in music therapy and music medicine studies. This may introduce possible bias.

Incomplete outcome data

The dropout rate was small for most trials, falling between 0% and 17%. Fifteen trials reported dropout rates of more than 20%. For 21 trials, it was unclear whether there were any participant withdrawals. Most trials reported reasons for dropout. Detailed information on dropout rate and reasons is included in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Selective reporting

We found evidence of selective reporting in three trials (Burns 2008; Hunter 2020; Ratcliff 2014).

We examined publication bias visually in the form of funnel plots for several of the included outcomes. Visual inspection suggested that there was no publication bias for anxiety (Figure 4), depression (Figure 5), pain (Figure 6),

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone with adults, outcome: 1.1 Anxiety (STAI).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone with adults, outcome: 1.6 Depression.

6.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone with adults, outcome: 1.13 Pain.

Other potential sources of bias

For ten trials, it was unclear if there were other potential sources of bias because no explicit declaration of interest statement was included in the publication..

Overall risk of bias

As a result, only one trial was at overall low risk of bias (Bradt 2015). Three additional trials were at low risk of bias for objective outcomes, as they satisfied all criteria used to assess risk of bias (Alam 2016; Duocastella 1999; Nguyen 2010). Five trials were at moderate risk of bias for objective outcomes (Binns‐Turner 2008; Bro 2019; Burrai 2014; Hilliard 2003; Palmer 2015). Seventy‐two trials were at high risk of bias. The main reason for receiving a high risk of bias rating was the lack of blinding. As pointed out above, blinding is often impossible in music therapy and music medicine studies that use subjective outcomes, unless the studies compare the music intervention with another active treatment intervention (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation). This is especially true for music therapy studies that use active music‐making. Therefore, it appears impossible for these types of studies to receive a low or even moderate risk of bias even if they have adequately addressed all other risk factors (e.g. randomization, allocation concealment, etc.).

Effects of interventions

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults

Primary outcomes

Psychological outcomes

State anxiety

Thirty‐three trials examined the effects of music interventions plus standard care compared to standard care alone for anxiety in adult participants with cancer. Nineteen trials measured anxiety by means of the Spielberger State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory ‐ State Anxiety form (STAI‐S) (Alam 2016; Binns‐Turner 2008; Bro 2019; Bulfone 2009; Chen 2013; Danhauer 2010; Firmeza 2017; Harper 2001; Jin 2011; Kwekkeboom 2003; Li 2012; Lin 2011; O'Callaghan 2012; Rossetti 2017; Smith 2001; Vachiramon 2013; Wan 2009; Wren 2019; Zhou 2015); and fourteen trials reported mean anxiety measured by other scales, such as a numeric rating scale (NRS) or a visual analogue scale (VAS) (Cai 2001; Chen 2020; Cassileth 2003; Doro 2017; Ferrer 2005; Hanser 2006; Karadag 2019; Li 2004; Mou 2020; Palmer 2015; Tuinmann 2017; Verstegen 2018; Yates 2015; Zhao 2008). We could not include the data from Burns 2008 because it did not report post‐test or follow‐up scores. The author did provide follow‐up scores (four weeks post‐intervention), but we could not combine these with the post‐test scores of the other trials. Moreover, Burns 2008 reported a large moderating effect of pre‐intervention affect state scores on post‐test scores and follow‐up scores. We also did not include the data from Kwekkeboom 2003 in the meta‐analysis because this study was affected by a serious flaw in the implementation of the intervention. Participants in this trial listened to music while undergoing painful medical procedures. However, they reported that the use of headphones prevented them from hearing the surgeon, increasing their anxiety. Finally, we reported the data from Hanser 2006 narratively and did not include them in the meta‐analysis because of the high attrition rate (40%). In addition, the researchers experienced serious issues with intervention implementation within the predetermined implementation timeframe (three sessions were implemented over a 15‐week period), and the authors concluded that the intervention was significantly diluted because of this.

A meta‐analysis of 17 trials (N = 1381) that used the full STAI‐S (score range: 20 to 80) to examine state anxiety in 1381 participants indicated a lower state of anxiety in participants who received standard care combined with music interventions than those who received standard care alone (MD −7.73, 95% CI −10.02 to −5.44, P < 0.00001; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1). Statistical heterogeneity was high across the trials (I2 = 93%). Removal of outliers (Binns‐Turner 2008; Harper 2001; Wan 2009) did not reduce heterogeneity much (I2 = 80%) . In Kwekkeboom 2003, participants in the music listening group reported higher levels of anxiety at post‐test (mean: 33.45, standard deviation (SD) 1.77) than those in the standard care group (mean: 30.59, SD 1.93). A sensitivity analysis excluding the trials that used inadequate methods of randomization (Bulfone 2009; Chen 2013) had minimal impact on the pooled effect size (MD −7.83, 95% CI −10.91 to −4.76, P < 0.00001, I2 = 92%; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 1: Anxiety (STAI)

The standardized mean difference (SMD) of trials that reported post‐test anxiety scores on measures other than the full‐form STAI‐S (N = 882) also suggested a moderate to large anxiety‐reducing effect of music (SMD −0.76, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.25, P = 0.004; Analysis 1.2; 9 trials (Cai 2001; Chen 2020; Ferrer 2005; Karadag 2019; Li 2004; Mou 2020; Verstegen 2018; Zhao 2008; Yates 2015)). The results were not consistent across the trials (I2 = 91%) with one trial reporting a much larger effect size than other trials (Mou 2020) and one trial favoring the standard care control condition (Chen 2020). We did not include the data of four trials in the meta‐analysis because change scores and final scores should not be combined for the computation of a SMD (Alam 2016; Cassileth 2003; Doro 2017; Palmer 2015) or because only effect sizes were reported (Tuinmann 2017). However, the data by Cassileth 2003 were consistent with the results of the meta‐analysis, reporting a greater effect of music therapy on anxiety (mean change score: −2.6, SD 2.5) than standard care alone (mean change score: −0.9, SD 3.0) on the POMS‐anxiety subscale (score range: 0 to 36). Likewise, the data from Palmer 2015 indicated a beneficial effect of music therapy (mean change score: −30.9, SD 36.3) versus standard care (mean change score: 0, SD 22.7) on the Global Anxiety‐VAS (score range: 0 to 100 mm). The findings from Tuinmann 2017 also supported a greater treatment benefit of music therapy than standard care control (MD = −0.3, 95% CI −1.8 to −1.2). Finally, Alam 2016 reported similar change scores for the music intervention treatment arm (mean change score: −9.94, SD 2.42) and the control treatment arm (mean change score: −9.35, SD = 2.71), whereas Doro 2017 reported negligible change in anxiety for both treatment arms. A sensitivity analysis to examine the impact of randomization method, excluding the data of Cai 2001, Ferrer 2005 and Li 2004, had a minimal impact on the pooled effect size (SMD −0.72; 95% CI −1.67 to 0.23, P = 0.14; Analysis 1.2 ). A sensitivity analysis removing studies that included some participants without a cancer diagnosis (Verstegen 2018) did not impact the effect size estimate (SMD −0.75, 95% CI −1.3 to −0.21, P = 0.007, I2 = 92%; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 2: Anxiety (non‐STAI (full version) measures)

Based on these findings, we can conclude that music interventions may have a large anxiety‐reducing effect. However, because participants could not be blinded to the music intervention and anxiety was measured using self‐report, there is a potential for biased reporting by the participants. Due to this potential bias combined with the high heterogeneity associated with the pooled effect, the finding is low‐certainty evidence (Table 1).

We conducted several a priori‐determined subgroup analyses, as outlined in the Methods.

Firstly, we compared the treatment benefits of music therapy versus music medicine studies for anxiety. We only included studies that reported post‐test scores in this analysis to allow for computation of a standardized mean difference across studies. The pooled effect of four music therapy studies (SMD −0.81, 95% CI −1.16 to −0.46, P < 0.00001, I2 = 0%; Ferrer 2005; Rossetti 2017; Verstegen 2018; Yates 2015) was similar to that of the music medicine studies (SMD −0.87, 95% CI −1.28 to −0.47, P < 0.0001, I2 = 94%; Binns‐Turner 2008; Bro 2019; Bulfone 2009; Cai 2001; Chen 2020; Danhauer 2010; Jin 2011; Karadag 2019; Li 2004; Li 2012; Lin 2011; Mou 2020; O'Callaghan 2012; Smith 2001; Vachiramon 2013; Wan 2009; Wren 2019; Zhao 2008; Zhou 2015). Although there was no evidence of a difference in effect between the music therapy studies and the music medicine studies (P = 0.83), it is worth noting that the results of the music therapy studies were consistent across studies, whereas the results of the music medicine studies were highly heterogeneous (Analysis 1.3). Because the results of the music therapy studies were consistent across studies, we can have greater confidence that music therapy interventions offered by a trained music therapist will result in large reductions in anxiety in adults with cancer.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 3: Anxiety (intervention subgroup)

Secondly, we compared studies that used patient‐preferred music with studies that used researcher‐selected music. For this comparison, we only included studies that used listening to pre‐recorded music as the intervention. Music preference did not appear to impact the treatment benefits for anxiety. The use of patient‐preferred music resulted in a SMD of −0.81 (95% CI −1.3 to −0.32, P = 0.001, I2 = 94%), whereas researcher‐selected music resulted in a SMD of −0.79 (95% CI −1.19 to −0.39, P = 0.0001, I2 = 56%) (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 4: Anxiety (music preference)

Finally, we compared the music medicine studies by type of intervention (e.g. music‐guided relaxation, music listening alone, etc.). We could not conduct this subgroup analysis for music therapy studies because of an insufficient number of trials. The majority of the music medicine studies used listening to pre‐recorded music. Four studies, however, embedded relaxation or imagery instructions within the pre‐recorded music (Jin 2011; Lin 2011; Wan 2009; Zhou 2015). The pooled effect of these four studies (SMD −1.61, 95% CI −2.56 to −0.65, P = 0.0009, I2 = 95%) was much larger than that of music listening only studies (SMD −0.71, 95% CI −1.16 to −0.26, P = 0.002, I2 = 89%), but because of the large heterogeneity, there was no evidence of a difference in effect between these two types of interventions (P = 0.10) (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 5: Anxiety (music‐guided relaxation)

Depression

Twelve trials (N = 1021) examined the effects of music plus standard care compared to standard care alone on depression in 1021 participants (Arruda 2016; Bates 2017; Cai 2001; Cassileth 2003; Chen 2020; Clark 2006; Karadag 2019; Li 2012; Verstegen 2018; Wan 2009; Yates 2015; Zhou 2015). Their pooled estimate indicated a moderate treatment effect of music (SMD −0.41, 95% CI −0.67 to −0.15, P = 0.002; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.6), but the results were inconsistent across trials (I2 = 72%). When we removed two outliers (Karadag 2019; Li 2012), heterogeneity was greatly reduced (I2 = 13%), but there was no identifiable reason why these studies acted like an outlier. At first sight, it appeared that the outlier values might be explained by the fact that both of these studies used a large number of sessions (i.e. up to 25‐60 sessions compared to 1‐5 sessions in other studies). However, Cai 2001 used 30 sessions and this study did not act as an outlier.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 6: Depression

A sensitivity analysis examining the impact of randomization method resulted in a smaller pooled effect size (SMD −0.32, 95% CI −0.59 to −0.04, P = 0.03, I2 = 70%; Analysis 1.6). A sensitivity analysis excluding one study that included some participants who did not have a cancer diagnosis (Verstegen 2018) did not impact the pooled effect size (SMD −0.41, 95% CI −0.68 to −0.15, P = 0.002, I2 = 75%; Analysis 1.6). Because participants could not be blinded to the music intervention and self‐report was used to measure depression, there is a potential for bias. This, as well as the fact that results were inconsistent across trials, makes this very‐low certainty evidence (Table 1).

Subgroup analyses revealed that there was no evidence of a difference in effect between music therapy and music medicine studies for the outcome of depression (P = 0.14) (Analysis 1.7) or between patient‐preferred versus researcher‐selected music (Analysis 1.8).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 7: Depression (intervention subgroup)

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 8: Depression (music preference)

Distress

Two trials (N = 127) examined the effects of music interventions on distress during radiation therapy (Clark 2006; Rossetti 2017). Their pooled estimate did not find support for an effect of music (SMD −0.38, 95% CI −1.43 to 0.66, I2 = 88%, P = 0.47).

Mood

The pooled estimate of five trials (N = 221) resulted in little effect of music interventions for mood in participants with cancer (SMD 0.53, 95% CI −0.03 to 1.11, P = 0.07; very low‐certainty evidence) Analysis 1.10; Burrai 2014; Cassileth 2003; Moradian 2015; Ratcliff 2014). The results were inconsistent across studies (I2 = 76%), with Burrai 2014 reporting much larger treatment benefits than the other studies. Removal of this outlier greatly reduced the heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Although Burrai 2014 was the only study that used live saxophone music played by a nursing staff member, other studies included in this analysis used live music offered by music therapists. Therefore, it is unclear if the use of live music may have accounted for the large treatment benefit in the Burrai 2014 study. The potential bias stemming from participants not being blinded to the music intervention and the high heterogeneity associated with the pooled effect makes this very low‐certainty evidence (Table 1).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 10: Mood

A sensitivity analysis based on randomization method slightly increased the pooled effect (SMD 0.68, 95% CI −0.04 to 1.39, P = 0.06, I2 = 81%; Analysis 1.10) but the evidence concerning the impact of music interventions on mood is very uncertain.. We could not include the data from Burns 2001a in the meta‐analysis because the authors did not use a constant in the computation of their scores, as recommended in the Profile of Mood States (POMS) scoring guide (McNair 1971). The results of the meta‐analysis were robust compared to Burns 2001a, which reported a mean post‐test score of −48.25 (SD 32.96) for the music therapy group and a mean post‐test score of 20.75 (SD 30.87) for the control group. Due to a large baseline difference between the music and control treatment arms in Doro 2017, the post‐test values of this trial could not be included in the meta‐analysis. The results by Bieligmeyer 2018 are reported separately because this study used vibro‐acoustic therapy as the intervention. The authors reported larger mood‐enhancing effects in the vibro‐acoustic treatment arm (pretest scores: 71.8 SD 19.67; post‐test scores: 81, SD 16.26) than the control group (pre‐test scores: 73.52, SD 20.62; post‐test scores: 72.75, SD 20.63).

A subgroup analysis comparing music therapy (SMD 0.37, 95% CI −0.13 to 0.87, P = 0.15) with music medicine (SMD 0.73, 95% CI −0.54 to 1.99, P = 0.26) found no evidence of a difference in effect between the two types of studies (SMD 0.53, 95% CI ‐0.03 to 1.10, P = 0.6), but the results of the music therapy studies were consistent across studies (I2 = 37%), whereas the music medicine studies were inconsistent across studies (I2 = 90%) (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 11: Mood (intervention subgroup)

Hope

Two studies examined the treatment benefits of music interventions for hope (Arruda 2016; Verstegen 2018) (Analysis 1.12). The pooled effect size indicated an increase of 3.19 on the Herth Hope Index with music interventions compared to control (MD, 95% CI 0.12 to 6.25, I2 = 48%, P = 0.04; very low‐certainty evidence).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 12: Hope

Resilience

One music therapy trial with adult cancer participants (N = 15) (Letwin 2017) reported greater improvements in resilience in the music therapy treatment arm (pre‐test scores: 74.13, SD 11.29; post‐test scores: 81.88, SD 7.55) than in the control arm (pre‐test scores: 75.29, SD 13.29; post‐test scores: 78.57, SD 9.14) as measured on the The Response to Stressful Events Scale (RSES) (range: 0 to 88) (Johnson 2011).

Physical symptoms

Pain

Twenty trials compared the effects of music versus standard care on pain (Alam 2016; Arruda 2016; Bieligmeyer 2018; Binns‐Turner 2008; Clark 2006; Danhauer 2010; Doro 2017; Fredenburg 2014a; Huang 2006; Kwekkeboom 2003; Letwin 2017; Li 2012; Moradian 2015; Reimnitz 2018; Tuinmann 2017; Verstegen 2016; Verstegen 2018; Wan 2009; Wren 2019).

We could not include the data from Alam 2016, Clark 2006 or Moradian 2015 in the meta‐analysis because of the use of change scores. We could not include the post‐test scores from Doro 2017 due to large baseline differences between the treatment arms. Tuinmann 2017 only reported effect sizes which could not be included in this meta‐analysis. Kwekkeboom 2003 compared the effects of music listening, audiotape and standard care on procedural pain and anxiety, finding that participants did not like wearing the headsets as it prevented them from hearing the surgeon, causing greater anxiety. The literature suggests that increased anxiety leads to increased pain perception (McCracken 2009); therefore, we excluded these data from the meta‐analysis. We did not include the data from Bieligmeyer 2018 in the meta‐analysis because this study examined the effects of vibro‐acoustic therapy which combines music with vibrations to affect the body.

The pooled effect of the remaining twelve studies with 632 participants resulted in a moderate effect for music on pain perception (SMD −0.67, 95% CI −1.07 to −0.26, P = 0.001; very low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.13). There was disagreement between the trials on the size of the effect (I2 = 81%), but this was due to Li 2012 reporting much larger treatment benefits than the other trials. Removal of this outlier reduced the heterogeneity to 23%. As this was the only study with a large number of sessions (up to 60 sessions), frequency of sessions may be a potential explanation for this outlier. As with other outcomes in this review, there is a potential for bias because the participants could not be blinded and self‐report outcome measures were used. In addition, the large heterogeneity lowered the certainty of the evidence for this outcome. A sensitivity analysis excluding those studies that included some participants who did not have a cancer diagnosis (Reimnitz 2018; Verstegen 2016; Verstegen 2018) resulted in a larger effect size (SMD −0.77, 95% CI −1.25 to −0.29, P = 0.002, I2 = 85%; Analysis 1.13).

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 13: Pain

Using a 0 to 10 numeric rating scale, Clark 2006 found that music therapy resulted in greater pain reduction (mean change score: −0.44, SD 2.55) than standard care (mean change score: 0.45, SD 1.87). In contrast, Moradian 2015 reported similar improvements in pain for the treatment (mean change score: −12.96, SD 24.16) and the control group (mean change score: −13.58, SD 28.51). Tuinmann 2017 reported a greater treatment benefit for music compared to standard care for pain (MD = ‐10, 95% CI ‐18.9 to ‐1.2) on the pain subscale of the European Organization for Research and Treatment on Cancer scale (EORTC). In contrast, Alam 2016 reported minimal pain reduction in participants who listened to pre‐recorded music (mean change score: ‐0.41, SD = 1.69) versus those who did not (mean change score: ‐0.23, SD = 1.57) during cutaneous surgery. Finally, Bieligmeyer 2018 reported greater pain‐reducing effects in participants who underwent vibro‐acoustic therapy (pre‐test scores: 12.88, SD 19.59; post‐test scores: 10, SD 16.3) than those in the control group (pre‐test scores: 12.75, SD 18.62; post‐test scores: 15.36, SD 21.56).

For this outcome, we were able to compare the treatment benefits of music therapy versus music medicine studies (Analysis 1.14). The pooled effect of five music therapy trials suggested a moderate pain‐reducing effect of music therapy. This effect was consistent across trials and therefore enhanced our confidence in this evidence (SMD −0.47, 95% CI −0.86 to −0.07, P = 0.02, I2 = 0%; Fredenburg 2014a; Letwin 2017; Reimnitz 2018; Verstegen 2016; Verstegen 2018). The pooled effect of music medicine studies was larger but was highly inconsistent across studies (SMD −0.81, 95% CI −1.38 to −0.24, P = 0.005, I2 = 89%; (Arruda 2016; Binns‐Turner 2008; Danhauer 2010; Huang 2006; Li 2012; Wan 2009; Xie 2001).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Music intervention plus standard care versus standard care alone in adults, Outcome 14: Pain (intervention subgroup)

We were also able to examine the impact of music preference on treatment effect (SMD −0.84, 95% CI −1.34 to −0.33, P = 0.001, I2 = 87%; Analysis 1.15). Although there was no evidence of a difference in effect between the use of patient‐preferred music and researcher‐selected music (P = 0.78), the use of patient‐preferred music led to a larger pooled effect (SMD −0.87, 95% CI −1.65 to −0.1, P = 0.03, I2 = 90%) than the use of researcher‐selected music (SMD −0.74, 95% CI −1.33 to 0.14, P = 0.02, I2 = 73%). The large heterogeneity was due to some studies reporting a much larger beneficial effect than others.

Fatigue

Ten trials examined the effects of music interventions on fatigue in 498 participants (Bates 2017; Cassileth 2003; Chen 2020; Clark 2006; Ferrer 2005; Fredenburg 2014b; Moradian 2015; Reimnitz 2018; Rosenow 2014; Wren 2019). The pooled estimate of their change scores indicated a small effect for music interventions (SMD −0.28, 95% CI −0.46 to −0.10, P = 0.002; low‐certainty evidence, Analysis 1.16), with consistent results across studies (I2 = 0%). Burns 2008 also collected data on fatigue; however, investigators did not report post‐intervention data; the study provided us with four‐week post‐intervention follow‐up scores, but could not provide the immediate post‐test scores. This prevented us from pooling their data with data from the other three studies. A sensitivity analysis excluding one study due to inadequate randomization methods (Ferrer 2005) had minimal impact on the pooled effect (SMD −0.26, 95% CI −0.45 to ‐0.07, P = 0.007, I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.16). A sensitivity analysis excluding one study that included some participants who did not have a cancer diagnosis (Reimnitz 2018) also had minimal impact on the pooled effect (SMD −0.26, 95% −0.44 to −.0.07, P = 0.007, I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.