Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to evaluate the validity, reliability and acceptability of the Implementation Leadership Scale in the Chinese nursing context.

Design

This study utilized a cross‐sectional design.

Methods

This study was conducted in one general tertiary hospital with 234 nurses (85.3% response rate) from 35 clinical units in China. Content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, reliability (internal consistency), agreement indices and acceptability were evaluated. The data collection was from December 1st, 2017 to June 30th, 2018.

Results

Confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated a good model fit to the four‐factor implementation leadership model. The psychometric testing also indicated good convergent validity, high internal consistency and acceptable aggregation. Most participants completed the scale in two minutes or less and agreed or strongly agreed that the questions were relevant to implementation leadership, clear and easy to answer.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the Chinese Implementation Leadership Scale is a valid, reliable and pragmatic tool for measuring strategic leadership for implementing evidence‐based practices.

Keywords: China, evidence‐based practice, health services research, leadership, nursing, psychometrics

1. INTRODUCTION

Evidence‐based practice (EBP) refers to a practitioner's conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence when making decisions about patient care (Sackett et al., 1996), and requires integration of the best research evidence with individual clinical expertise and patient's unique values and circumstances (Straus, 2019). The implementation of EBP has been widely accepted as a global priority for promoting high‐quality clinical practices and optimal patient outcomes (Grol & Grimshaw, 2003; Munten et al., 2010). However, studies show that many EBPs have not been consistently used by nurses across different clinical settings (Asamani et al., 2020; Weng et al., 2013).

2. BACKGROUND

Many contextual factors have been identified that influence EBP implementation (Aarons et al., 2011; Damschroder et al., 2009; Hu et al., 2020). Leadership is among these factors and plays a critical role in promoting the integration of evidence into nursing care (Hu & Gifford, 2018). Implementation leadership has been defined as a multidimensional process that influences staff, their environment and the organizational infrastructures to promote the integration of evidence in clinical practice (Gifford et al., 2007).

Numerous studies have been conducted to understand the concept of implementation leadership. A recent systematic review identified 31 studies investigating the leadership behaviours of managers that are associated with research use by clinical staff in nursing and allied health professionals (Gifford et al., 2018). Leadership development interventions have also been developed and studied to strengthen the implementation leadership of nurses and other healthcare providers (Aarons et al., 2017; Gifford et al., 2019; Richter et al., 2016; Välimäki et al., 2018). With the increased recognition of leadership in EBP implementation, valid, reliable and pragmatic measures of implementation leadership are needed (Reichenpfader et al., 2015).

In 2014 and with funding from the US National Institutes of Health, Aarons, Ehrhart and Farahnak developed the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS) that focussed on strategic leadership for EBP implementation (Aarons et al., 2014). They used an iterative approach (i.e. literature review, expert panel), factor analytic methods and quantitative psychometric testing to develop and validate the 12‐item scale (Aarons et al., 2014). The ILS was also developed to be a brief and pragmatic measure that has high utility for research and clinical quality improvement activities (Glasgow, 2013; Glasgow & Riley, 2013). The ILS assesses behaviours that leaders enact to facilitate EBP implementation and includes four dimensions of leadership: proactive, knowledgeable, supportive and perseverant (Aarons et al., 2014). The ILS has been validated and used in varied settings, such as mental health clinics, alcohol and drug use treatment agencies, education, child welfare services and nursing in the USA (Aarons et al., 2014, 2016; Finn et al., 2016; Lyon et al., 2018; Shuman et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2018). Translations and validations have been done or are in process, in Norwegian (Torres et al., 2018), Greek (Mandrou et al., 2020) and other languages (i.e. Finnish, German, Swedish and Vietnamese).

EBP was introduced to the context of Chinese nursing in 2001 and is now considered an important step in effective and high‐quality nursing care in China (The Lancet, 2012). A validated, reliable and acceptable measurement tool of implementation leadership is necessary to understand and evaluate the impact of nursing leadership on EBP implementation. Thus, our research team translated, adapted and validated the ILS in the Chinese nursing context. We used a systematic process set forth by Sousa and Rojjanasrirat (2011) based on a comprehensive review of methodological approaches to translation, adaptation and validation of research instruments for cross‐cultural research (Sousa & Rojjanasrirat, 2011). The translation and adaptation process of the ILS was completed and reported in a previous study (Hu et al., 2019).

The purpose of the current study was to analyse the psychometric properties of the translated and adapted ILS in the Chinese nursing context. Specifically, this study aimed to test the validity, reliability and acceptability of the translated ILS in China. Validity and reliability included content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, internal consistency and aggregation analyses. Acceptability testing included time to complete the Chinese ILS, ease of completion, relevance and clarity of each item in the Chinese ILS (Sousa & Rojjanasrirat, 2011; Streiner, 2008).

3. METHODS

3.1. Study design

This study utilized a cross‐sectional research design.

3.2. Setting and participants

The content validation focussed on whether the scale had appropriate items sampled to adequately represent the construct being measured (Streiner, 2008). Ten experts who were knowledgeable about healthcare leadership and EBP were recruited to evaluate the relevance of each item in the scale for measuring implementation leadership in Chinese nursing context. Our invited panel included senior administrators and clinical leaders in medicine and nursing at a university‐affiliated hospital in China, and researchers and educators in leadership from the affiliated university.

To test other psychometric properties, convenience sampling was used to recruit nursing staff from the affiliated university teaching hospital. Inclusion criteria were nursing staff who had worked for more than one year in their current positions. The estimated sample size was 230, which was determined by the requirement of the confirmatory factor analysis and the number of participants from previous studies (Aarons et al., 2014, 2016; Finn et al., 2016; Lyon et al., 2018; Shuman et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2018).

3.3. Data collection

For content validation, each expert completed a content validity questionnaire, where they were asked to rate each Chinese ILS item (postlanguage validation) for relevance using a four‐point scale (1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant) (Polit & Beck, 2006). Comments or suggestions on wording revisions were encouraged through an open‐ended question at the end of the questionnaire.

To test the other psychometric properties, each eligible nurse received an invitation link to participate in the online survey through WeChat, which is one of the most popular social media platforms in China. WeChat was first released in 2011, and by 2018 had over 1 billion daily active users. WeChat has been widely used to disseminate surveys to healthcare professionals in China (Xia et al., 2019). After reviewing and signing an electronic consent with information on the study, participants were given access to the survey, which included four questionnaires: demographic information, Chinese ILS (staff version), Chinese Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) and an acceptability questionnaire. The demographic information included age (year), gender, the highest level of education, the type of clinical unit, number of years nursing and number of years worked in the hospital.

3.4. Instruments

The ILS includes 12 items scored on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 4 (a very great extent) (Aarons et al., 2014). There are two different versions of the ILS: one allows staff to assess their leader and another for leaders to assess themselves (Aarons et al., 2014). Both versions have the same 12 statements but differ in the referent of the items (the leader name being used in the staff version, which is replaced by “I” in the leader version). The staff version of the Chinese ILS was used in this study, and nursing staff were instructed to report on the leadership behaviours of the nurse manager in their units (Hu et al., 2019).

The MLQ was used to evaluate convergent validity. The MLQ is one of the most commonly used measurement tools used in research to assess transformational leadership and transactional leadership (Bass & Avolio, 1995). The MLQ has good psychometric properties, including internal consistency and concurrent and predictive validity (Aarons, 2006). Transformational leadership was measured with 20 items in four subscales: idealized influence (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87, eight items), inspirational motivation (Cronbach's alpha = 0.91, four items), intellectual stimulation (Cronbach's alpha = 0.90, four items) and individualized consideration (Cronbach's alpha = 0.90, four items) (Bass & Avolio, 1995). Transactional leadership was measured with one subscale: contingent reward (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87, four items) (Bass & Avolio, 1995). All items were scored on a 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“frequently, if not always”) scale.

The acceptability questionnaire for the ILS included one question about the time it took to complete the survey (“How long did you take to finish the 12 items?”) and three items that participants rated to the extent they agreed with each item on a five‐point scale (0 = not at all; 4 = a very great extent). The three items were as follows: (1) These questions are easy to respond to; (2) These questions are relevant to implementation leadership; and (3) These questions are clear.

3.5. Statistical methods

The content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, internal consistency, aggregation analyses and acceptability of the Chinese ILS were tested using the following statistical methods. Content validity was evaluated using item‐level content validity index (I‐CVI: percentage of experts rating an item as “relevant” or “highly relevant”), scale‐level CVI/averaging calculation (S‐CVI/Ave: mean of the I‐CVIs for all items on the scale) and scale‐level CVI/universal agreement calculation (S‐CVI/UA: percentage of items on a scale rated as “relevant” or “highly relevant” by all the experts) (Polit & Beck, 2006; Polit et al., 2007). To remove agreement by chance, modified Cohen's coefficient kappa (k*) was analysed for inter‐rater agreement (Polit et al., 2007). The minimal I‐CVI, S‐CVI/Ave and S‐CVI/UA recommended were 0.78, 0.90 and 0.80, respectively (Polit & Beck, 2006; Polit et al., 2007). The criteria for k* was the following: poor < 0.40, fair = 0.40–0.59, good = 0.60–0.74 and excellent ≥ 0.75 (Polit et al., 2007).

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to test structural validity. Standardized estimates were obtained, which provided the factor loadings (if >0.6, good) and correlations between factors. Model fit was assessed using the following indices: normed chi‐square (if <3, good), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; if <0.08, adequate), the upper limit (90% confidence interval) of the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA 90CI; if <0.08, good), the comparative fit index (CFI; if >0.95, good), the Tucker–Lewis index (TLI; if >0.95, good) and the standardized root mean square residual (SRMR; if <0.05, good) (Mulaik et al., 1989).

Convergent validity was assessed by computing Pearson correlation coefficients of ILS subscale and total scale scores with MLQ subscale and total scale scores. The correlation is considered high when the Pearson correlation coefficient is greater than 0.5, and moderate when the coefficient is >0.3 (Cohen, 1988). Reliability (i.e. internal consistency) was assessed by examining Cronbach's alpha for each of the subscales and the total scale. The internal consistency is considered good when Cronbach's alpha is >0.7 (Streiner, 2008).

In order to determine whether the scores represented a unit‐level construct, agreement indices, which includes the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC, type 1) and the average correlation in group (awg), were tested for aggregation analyses. This is relevant as nurses were working in units led by a single leader who was the subject of the implementation leadership being evaluated. Higher levels of agreement suggest that higher levels of aggregation are supported. Specifically, an ICC value of 0.01 is considered a small effect, 0.10 is considered a medium effect and a value of 0.25 is considered a large effect (LeBreton & Senter, 2008). It is recommended that an awg be interpreted with values of 0.31–0.50 as a weak agreement, values between 0.51–0.70 as moderate agreement, and values of 0.71–0.90 indicating strong agreement in group (LeBreton & Senter, 2008).

The length of time in seconds to complete the Chinese ILS and the scores on ease of completion, relevance and clarity of each item in the Chinese ILS were summarized using mean, standard deviation (SD) and range. The descriptive analyses and tests for content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, internal consistency and acceptability were performed using the IBM SPSS and AMOS for Windows Version 25 statistical package (IBM Inc). ICC (type 1) and awg statistics were calculated using the “multilevel” package (Bliese, 2016) and performed using R statistical software version 3.6.0 (R Core Team).

4. RESULTS

Ten experts participated in the content validation of the ILS in Chinese (71.4% response rate). Two‐hundred and thirty‐four of 285 eligible nurses completed the surveys (85.3% response rate). There were no missing data in the surveys. Survey respondents were from 35 clinical units with three to 16 nurses completing the questionnaire from each unit (mean = 6.7). Demographic characteristics of the survey respondents are presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographic characteristics of expert panel in content validation and participating nurses in psychometric testing

| Expert panel in content validation | N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Female | 8 |

| Male | 2 |

| Education | |

| Doctoral degree | 5 |

| Master's degree | 3 |

| Bachelor's degree | 2 |

| Position | |

| Hospital administrative leaders | 2 |

| Physician senior leaders | 3 |

| Nurse senior leaders | 2 |

| Professors | 3 |

| Working years | |

| 11–20 | 6 |

| >20 | 4 |

| Participating nurses in psychometric testing | N = 234 |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 231 (98.7%) |

| Male | 3 (1.3%) |

| Highest level of education | |

| Bachelor's degree | 88 (37.6%) |

| Associate degree (i.e. a three‐year education programme) | 144 (61.5%) |

| Master's degree | 2 (0.9%) |

| Type of clinical settings | |

| Surgery | 97 (41.4%) |

| Emergency | 47 (20.1%) |

| Internal medicine | 46 (19.7%) |

| Paediatrics | 27 (11.5%) |

| Gynaecology and obstetrics settings | 17 (7.3%) |

| Age (year) | Mean = 30.6, SD = 6.1, range = 22–52 |

| Number of years nursing | Mean = 9.0, SD = 6.8, range = 1–33 |

| Number of years worked in the hospital | Mean = 8.6, SD = 6.8, range = 1–33 |

All content validity indices reached the recommended standards (see Table 2). Two experts commented that scale item 4 “Your supervisor/I am knowledgeable about evidence‐based practice” was not itself related to implementation leadership, but a prerequisite for a leader to have to perform implementation leadership; this item had the lowest I‐CVI (0.80) and k* (0.79). Moreover, four experts suggested that item 11 “Your supervisor/I carry on through the challenges of implementing evidence‐based practice” was very similar to item 10 “Your supervisor/I persevere through the ups and downs of implementing evidence‐based practice.”

TABLE 2.

Content validity indices

| E1 | E2 | E3 | E4 | E5 | E6 | E7 | E8 | E9 | E10 | N of “4” | N of “3” and “4” | I‐CVI | Pc | k* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ILS Item 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 0.80 | 0.043945 | 0.79 |

| ILS Item 5 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 7 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 8 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 9 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 10 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| ILS Item 11 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 0.90 | 0.009766 | 0.89 |

| ILS Item 12 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 9 | 10 | 1.00 | 0.000977 | 1 |

| S‐CVI/Ave = 0.98 | |||||||||||||||

| S‐CVI/UA = 0.83 | |||||||||||||||

1 = not relevant, 2 = somewhat relevant, 3 = quite relevant, 4 = highly relevant. Pc (probability of a chance occurrence) = [N!/A!(N‐A)!] *0.5N where N = number of experts and A = number agreeing on good relevance. k* = (I‐CVI ‐ Pc)/(1 ‐ Pc). ILS items can be found in Supplements 1 and 2.

Abbreviations: E, Expert; I‐CVI, item‐level content validity index; k*, modified Cohen's coefficient kappa; S‐CVI/Ave, scale‐level CVI/averaging calculation; S‐CVI/UA, scale‐level CVI/universal agreement calculation.

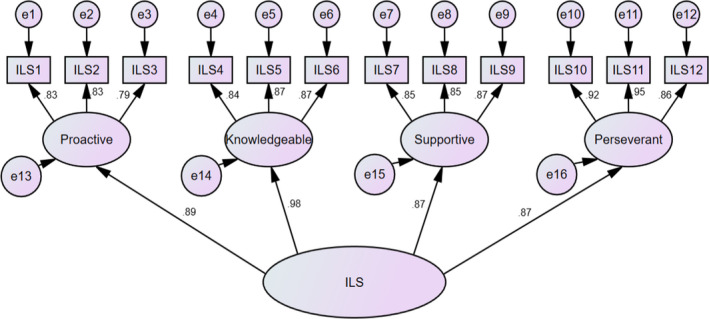

In the confirmatory factor analysis, factor loadings for four domains ranged from 0.87–0.98 and factor loadings for the 12 items ranged from 0.79–0.95 (p's < .05; see Table 3 and Figure 1). The multiple indicators demonstrated a good model fit to the four‐factor implementation leadership model (i.e. proactive, knowledgeable, supportive and perseverant) with the hypothesized first‐ and second‐order factor structure: normed chi‐square = 2.00, RMSEA = 0.07, RMSEA 90% CI = 0.04–0.08, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, and SRMR = 0.034.

TABLE 3.

Implementation leadership scale, subscale and item statistics

| ILS items, subscales and total | Mean | SD | ICC | awg | α | CFA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive leadership | 2.38 | 0.93 | 0.16 | 0.56 | 0.95 | 0.89 |

| 1. Develops a plan to facilitate EBP implementation | 2.34 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.62 | 0.83 | |

| 2. Minimizes obstacles to implementation of EBP | 2.41 | 1.02 | 0.14 | 0.58 | 0.83 | |

| 3. Establishes clear standards for implementation of EBP | 2.40 | 1.13 | 0.08 | 0.46 | 0.79 | |

| Knowledgeable leadership | 2.52 | 0.99 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.86 | 0.98 |

| 4. Is knowledgeable about EBP | 2.55 | 1.12 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.84 | |

| 5. Is able to answer staff questions about EBP | 2.48 | 1.07 | 0.15 | 0.55 | 0.87 | |

| 6. Knows what he/she is taking about when it comes to EBP | 2.55 | 1.09 | 0.10 | 0.51 | 0.87 | |

| Supportive leadership | 2.87 | 0.94 | 0.20 | 0.56 | 0.90 | 0.87 |

| 7. Recognizes and appreciates employee efforts | 2.75 | 1.08 | 0.18 | 0.53 | 0.85 | |

| 8. Supports employee efforts to learn more about EBP | 2.99 | 1.04 | 0.11 | 0.46 | 0.85 | |

| 9. Supports employee efforts to use EBP | 2.87 | 1.00 | 0.22 | 0.57 | 0.87 | |

| Perseverant leadership | 2.52 | 1.02 | 0.13 | 0.52 | 0.89 | 0.87 |

| 10. Perseveres through the ups and downs of implementing | 2.53 | 1.10 | 0.10 | 0.49 | 0.92 | |

| 11. Carries on through the challenges of implementing EBP | 2.56 | 1.10 | 0.11 | 0.48 | 0.95 | |

| 12. Addresses critical issues about implementation of EBP | 2.45 | 1.06 | 0.12 | 0.54 | 0.86 | |

| Implementation leadership scale total | 2.57 | 0.87 | 0.19 | 0.57 | 0.93 |

Abbreviations: awg, Average correlation in group; α, Cronbach's alpha; CFA, Confirmatory factor analysis factor loadings; EBP, Evidence‐based practice; ICC, Intraclass correlation coefficients (type 1).

FIGURE 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis

The internal consistency analysis showed a Cronbach's alpha of 0.93 for the total score, and 0.86–0.95 for the subscale scores of the Chinese ILS (see Table 3). As shown in aggregation analyses, the ICC (type 1) indicated medium effect (0.19) for the total ILS score and a weak to moderate degree of dependency (0.08–0.22) for the scores of the ILS subscale and individual items among nurses in the same unit (see Table 3). In addition, the awg indicated a moderate agreement (0.57) for the ILS scale and weak to moderate agreement ranging from 0.46–0.62 for individual items and subscales among nurses in the same unit (see Table 3).

The total score and subscale scores of the Chinese ILS had moderate to high correlations (0.40–0.63) with MLQ total and subscale scores (see Table 4). Participants spent an average of 80 s (SD = 49.61, range = 30–240 s) to complete the Chinese ILS. Most participants completed the Chinese ILS in one minute or less (N = 140, 59.8%), 62 participants (26.5%) used two minutes or less, and only 32 participants (13.7%) spent more than two minutes. Over three fourth of participants agreed or strongly agreed that the questions were relevant to implementation leadership (N = 209, 88.9%), clear (N = 196, 83.8%) and easy to answer (N = 178, 76.1%).

TABLE 4.

Convergent validity

| Implementation Leadership Scale | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proactive | Knowledgeable | Supportive | Perseverant | Total | |

| Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire | |||||

| Transformational leadership | |||||

| Inspirational motivation | 0.53 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.57 | 0.63 |

| Intellectual stimulation | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.62 |

| Individualized consideration | 0.40 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Idealized influence | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.60 | 0.55 | 0.63 |

| Transactional leadership | |||||

| Contingent reward | 0.49 | 0.52 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.59 |

p < .001 for all correlations

5. DISCUSSION

Leadership is among the most important components of the organizational process for promoting the integration of EBP and use of research evidence in clinical settings (Aarons et al., 2014; Gifford et al., 2018; Hu & Gifford, 2018). To enhance empirical work in this field, there is a strong need for pragmatic and efficient (i.e. valid, reliable, and brief) tools for measuring implementation leadership. Following our prior study on the translation and linguistic validation of the ILS in the Chinese nursing context (Hu et al., 2019), this study described the content validity, structural validity, convergent validity, internal consistency, aggregation analyses and the acceptability of the ILS. It is anticipated the Chinese ILS will allow scholars to understand the role of leadership in promoting EBP implementation and hold promise as a tool for organizations and leaders to develop implementation leadership in Chinese settings.

The content validity indices and modified Cohen's coefficient kappa values found in this study exceeded the minimum standards of content validity as recommended by Polit (Polit & Beck, 2006; Polit et al., 2007). These findings indicated that the Chinese ILS has an excellent level of content validity relevant to implementation leadership and also confirmed that the translation and linguistic issues previously identified had been fully resolved. Although four participants commented that “challenges” are one part of “ups and downs,” the repetition of ideas asked in different ways is not uncommon in survey scales (Hinkin et al., 1997). Therefore, no changes were made based on these comments.

Confirmatory factor analysis in this current study illustrated that the translated ILS had good structural validity in the Chinese nursing context. It indicated the scores of the ILS had an adequate reflection of the dimensionality of the construct (i.e. implementation leadership) to be measured. Also, it confirmed the same four‐factor implementation leadership model (Aarons Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014; Aarons et al., 2016; Finn et al., 2016; Lyon et al., 2018; Mandrou et al., 2020; Shuman et al., 2020; Torres et al., 2018). The consistent findings from the multiple studies across different settings provide sufficient evidence in relation to the factorial structure and structural validity of the ILS.

The moderate to high correlations (0.40–0.63) between Chinese ILS total and subscale scores and MLQ total and subscale scores in this current study indicated good convergent validity in the Chinese nursing context. The magnitude of the correlations suggested that there is some overlap between implementation leadership and general leadership (i.e. transformational and transactional leadership) but that ILS measures unique aspects of leadership (i.e. EBP implementation) not being captured by MLQ. Interestingly, the magnitude of the correlations in the current study was lower than those in previous studies in different settings, including outpatient mental health programs (0.62–0.75) and substance use disorder treatment organizations (0.57–0.77) in the USA (Aarons Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014; Aarons et al., 2016). This suggested that nurse leaders in hospitals in China, who received education about general leadership (i.e. transformational and transactional leadership) are not necessarily as likely to be effective implementation leaders and thus might need further training on the leadership behaviours necessary for effective EBP implementation.

The Cronbach's alpha indicated that the ILS had good reliability (i.e. high internal consistency) in the Chinese context. It showed that the 12 items in the ILS or the three items in each ILS subscale that propose to measure the same construct produced correlated scores. The weak to moderate magnitudes of ICC and awg, which were identified in aggregation analyses, indicates the acceptable degree of agreement among nursing staff in the same unit for evaluating the same nurse leader. However, the level of aggregation in this current study was lower than those in other ILS validation studies (Aarons Ehrhart, & Farahnak, 2014; Aarons et al., 2016; Finn et al., 2016; Shuman et al., 2020). The relatively strong ICC (type 1) values relative to the awg values seem to indicate that even though there is substantial variability between units in implementation leadership scores, there is also variability in units as well (Bliese, 2000).

These findings may be due to two reasons. First, the concepts of EBP, EBP implementation and implementation leadership were new for nurses in China (Gifford et al., 2018; Hu et al., 2019). Although the definition and example of EBP and EBP implementation were added in the Chinese ILS, respondents may have linked these concepts to different responsibilities which may have influenced their perceptions of their unit leaders’ implementation leadership behaviours. Second, participants in the previous linguistic validation of the Chinese ILS commented that it was challenging for them to evaluate certain leadership behaviours as being knowledgeable about EBP (Hu et al., 2019). They also had difficulties evaluating their leadership behaviours on the five‐point Likert scale (Hu et al., 2019). To help respondents understand the intent behind each question in the Chinese ILS, an instruction reads: “All answers are based on your perception of leadership behavior. If you are not sure, please give the best answer you think” (Hu et al., 2019). These linguistic issues about recall and inference may also cause a lower level of agreement in this study. Nevertheless, the lower level of agreement should not be over‐emphasized in light of the relatively strong ICC (type 1) values, which suggest that the ILS is capturing meaningful between‐unit differences in implementation leadership.

The findings about the acceptability in this current study suggested that the Chinese ILS has a low burden for respondents and is actionable according to the criteria for pragmatic behavioural health measures put forth by Glasgow and Riley (Glasgow & Riley, 2013). As implementation science takes place in real‐world settings, it is important to develop or use pragmatic instruments. It took most participants (N = 202, 86.3%) <2 min (i.e. average 80 s) to complete the Chinese ILS, which meets the required time length for pragmatic measures (Glasgow & Riley, 2013). In addition, no missing data suggest that the Chinese ILS is very efficient with minimum respondent errors and can be used in busy clinical settings (Glasgow & Riley, 2013; Martinez et al., 2014). Lastly, the ease of completion, relevance and clarity of the items identified in this current study illustrated that the Chinese ILS is actionable and of value to respondents (Glasgow & Riley, 2013; Martinez et al., 2014).

5.1. Strengths and limitations

The robust validation process of the ILS in this current study with previous translation and linguistic validation (Hu et al., 2019) provided evidence of comprehensive psychometric properties (i.e. validity, reliability and acceptability) of the ILS in the Chinese context. However, a limitation to this study is that psychometric data were collected from a single organization, specifically, in a general tertiary hospital in Shanghai. The city has more educational resources on leadership and EBP than other smaller cities in China. Therefore, participants in this study might have been more likely to be exposed to the concept of leadership and EBP compared with nurses working in other settings.

5.2. Implications for nursing management

The Chinese ILS is a valid, reliable and brief tool for measuring the extent to which a leader is proactive, knowledgeable, supportive and perseverant in their efforts to promote the EBP implementation in the Chinese context. This tool can be used to investigate nurse leaders’ leadership behaviour for EBP implementation in China and can be used with other contextual instruments to assess organizational context for implementation. It also has the potential to inform interventions for developing implementation leadership and then for improving the integration of EBP in clinical settings. Last, the Chinese ILS and other translated ILS instruments can provide an approach to understand the role of leadership in facilitating EBP implementation across different cultural contexts.

6. CONCLUSIONS

This current study builds on previous research by evaluating the validity, reliability and acceptability of the ILS in the Chinese nursing context. The findings of the study suggest that the Chinese version of ILS is a valid, reliable and pragmatic tool for measuring implementation leadership. Further studies using the ILS to investigate and improve implementation leadership in the nursing context are warranted.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors disclose no conflict of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.H. and W.G. conceived the presented idea. J.H., W.G., H.R., D.H., G.A. and M.E. developed the methods. L.Q., M.H. and N.B. verified the analytical methods. All the authors were actively involved in the data collection and data analysis. J.H. and W.G. took the lead in writing the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback and helped shape the research, analysis and manuscript.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Permission to translate and validate the ILS into the Chinese nursing context was obtained from the developers of the original scale (GAA, ME), and permission to use the Chinese MLQ was obtained from Mind Garden, Inc. that holds the copyright of the questionnaire. Ethical approval for the survey was obtained from the affiliated university (H02‐17‐15) in Canada and the hospital Research Ethics Boards in China (HJY‐2017‐285‐T213). An online consent form was provided to eligible nurses that included an information letter explaining the study emphasizing voluntary and anonymous participation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thanks to all the participants in the study for their time, support and suggestions throughout this study. Also, the authors appreciate Brianna Hammond, Yiyan Zhou, Zeina Al Awar, Leilei Yu and Sarah Running for their efforts and research assistance.

Hu J, Gifford W, Ruan H, et al. Validating the Implementation Leadership Scale in Chinese nursing context: A cross‐sectional study. Nurs Open. 2021;8:3420–3429. 10.1002/nop2.888

Wendy Gifford is the co‐first author and has contributed equally to this work with Jiale Hu.

Funding information

This study was funded by the Gaoyuan Nursing Grant Support of Shanghai Municipal Education (Hlgy1801gj) and University of Ottawa International Research Acceleration Program (2016‐2018). Drs. Aarons and Ehrhart were supported by grants from the United States National Institute on Drug Abuse R01DA049891 and R01DA038466(PI: Aarons) and National Institute of Mental Health R21MH098124 (PI: Ehrhart), R21MH082731 and R01MH072961(PI: Aarons). None of these funders had a role in study design, data collection and analysis, publication decisions, or preparation of the manuscripts or dissertation.

Contributor Information

Jiale Hu, Email: jhu4@vcu.edu, @garyhu11.

Hong Ruan, Email: ruanhong2003@163.com.

Denise Harrison, @dharrisonCHEO.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Aarons, G. A. (2006). Transformational and transactional leadership: Association with attitudes toward evidence‐based practice. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D. C.), 57(8), 1162–1169. 10.1176/appi.ps.57.8.1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G. A. , Ehrhart, M. G. , & Farahnak, L. R. (2014). The Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS): Development of a brief measure of unit level implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 9(1), 45. 10.1186/1748-5908-9-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G. A. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Farahnak, L. R. , & Sklar, M. (2014). The role of leadership in creating a strategic climate for evidence‐based practice implementation and sustainment in systems and organizations. Frontiers in Public Health Services and Systems Research, 3(3), 1–7. 10.13023/FPHSSR.0304.03 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G. A. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Moullin, J. C. , Torres, E. M. , & Green, A. E. (2017). Testing the leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI) intervention in substance abuse treatment: A cluster randomized trial study protocol. Implementation Science, 12(1), 29. 10.1186/s13012-017-0562-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G. A. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Torres, E. M. , Finn, N. K. , & Roesch, S. C. (2016). Validation of the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS) in Substance use Disorder Treatment Organizations. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 68, 31–35. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons, G. A. , Hurlburt, M. , & Horwitz, S. M. (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence‐based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asamani, J. A. , Amertil, N. P. , Ismaila, H. , Akugri, F. A. , & Nabyonga‐Orem, J. (2020). The imperative of evidence‐based health workforce planning and implementation: Lessons from nurses and midwives unemployment crisis in Ghana. Human Resources for Health, 18(1), 16. 10.1186/s12960-020-0462-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass, B. M. , & Avolio, B. J. (1995). MLQ: Multifactor leadership questionnaire (Technical Report). Center for Leadership Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P. D. (2000). Within‐group agreement, non‐independence, and reliability: Implications for data aggregation and analyses. In Klein K. J., & Kozlowski S. W. J. (Eds.), Multilevel theory, research and methods in organizations: Foundations, extensions, and new directions (pp. 349–381). Jossey‐Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Bliese, P. D. (2016). Multilevel: Multilevel Functions. R package version 2.6. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=multilevel [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences, 2nd ed. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L. J. , Aron, D. C. , Keith, R. E. , Kirsh, S. R. , Alexander, J. A. , & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50. 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn, N. K. , Torres, E. M. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Roesch, S. C. , & Aarons, G. A. (2016). Cross‐Validation of the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS) in child welfare service organizations. Child Maltreatment, 21(3), 250–255. 10.1177/1077559516638768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, W. , Davies, B. , Edwards, N. , Griffin, P. , & Lybanon, V. (2007). Managerial leadership for nurses' use of research evidence: An integrative review of the literature. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 4(3), 126–145. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2007.00095.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, W. , Lewis, K. B. , Eldh, A. C. , Fiset, V. , Abdul‐Fatah, T. , Aberg, A. C. , Thavorn, K. , Graham, I. D. , & Wallin, L. (2019). Feasibility and usefulness of a leadership intervention to implement evidence‐based falls prevention practices in residential care in Canada. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5, 103. 10.1186/s40814-019-0485-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, W. , Squires, J. E. , Angus, D. E. , Ashley, L. A. , Brosseau, L. , Craik, J. M. , Domecq, M. C. , Egan, M. , Holyoke, P. , Juergensen, L. , Wallin, L. , Wazni, L. , & Graham, I. D. (2018). Managerial leadership for research use in nursing and allied health care professions: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 13(1), 127. 10.1186/s13012-018-0817-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford, W. , Zhang, Q. , Chen, S. , Davies, B. , Xie, R. , Wen, S. W. , & Harvey, G. (2018). When east meets west: A qualitative study of barriers and facilitators to evidence‐based practice in Hunan China. BMC Nursing, 17, 26. 10.1186/s12912-018-0295-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. E. (2013). What does it mean to be pragmatic? Pragmatic methods, measures, and models to facilitate research translation. Health Education & Behavior, 40(3), 257–265. 10.1177/1090198113486805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow, R. E. , & Riley, W. T. (2013). Pragmatic measures: What they are and why we need them. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(2), 237–243. 10.1016/j.amepre.2013.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grol, R. , & Grimshaw, J. (2003). From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients' care. Lancet, 362(9391), 1225–1230. 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinkin, T. R. , Tracey, J. B. , & Enz, C. A. (1997). Scale construction: Developing reliable and valid measurement instruments. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 21(1), 100–120. 10.1177/109634809702100108 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. , & Gifford, W. (2018). Leadership behaviours play a significant role in implementing evidence‐based practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(7–8), e1684–e1685. 10.1111/jocn.14280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. , Gifford, W. , Ruan, H. , Harrison, D. , Li, Q. , Ehrhart, M. G. , & Aarons, G. A. (2019). Translation and linguistic validation of the implementation leadership scale in Chinese nursing context. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(5), 1030–1038. 10.1111/jonm.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J. , Ruan, H. , Li, Q. , Gifford, W. , Zhou, Y. , Yu, L. , & Harrison, D. (2020). Barriers and facilitators to effective procedural pain treatments for pediatric patients in the Chinese context: A qualitative descriptive study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 54, 78–85. 10.1016/j.pedn.2020.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancet, T. (2012). Science for action‐based nursing. The Lancet, 379(9828), 1763. 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)60741-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBreton, J. M. , & Senter, J. L. (2008). Answers to 20 questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11(4), 815–852. 10.1177/1094428106296642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon, A. R. , Cook, C. R. , Brown, E. C. , Locke, J. , Davis, C. , Ehrhart, M. , & Aarons, G. A. (2018). Assessing organizational implementation context in the education sector: Confirmatory factor analysis of measures of implementation leadership, climate, and citizenship. Implementation Science, 13(1), 5. 10.1186/s13012-017-0705-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandrou, E. , Tsounis, A. , & Sarafis, P. (2020). Validity and reliability of the Greek version of Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS). BMC Psychology, 8(1), 49. 10.1186/s40359-020-00413-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, R. G. , Lewis, C. C. , & Weiner, B. J. (2014). Instrumentation issues in implementation science. Implementation Science, 9, 118. 10.1186/s13012-014-0118-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulaik, S. A. , James, L. R. , Van Alstine, J. , Bennett, N. , Lind, S. , & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness‐of‐fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105(3), 430. 10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.430 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munten, G. , van den Bogaard, J. , Cox, K. , Garretsen, H. , & Bongers, I. (2010). Implementation of evidence‐based practice in nursing using action research: A review. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 7(3), 135–157. 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2009.00168.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , & Beck, C. T. (2006). The content validity index: Are you sure you know what's being reported? Critique and Recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 29(5), 489–497. 10.1002/nur.20147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit, D. F. , Beck, C. T. , & Owen, S. V. (2007). Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health, 30(4), 459–467. 10.1002/nur.20199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichenpfader, U. , Carlfjord, S. , & Nilsen, P. (2015). Leadership in evidence‐based practice: A systematic review. Leadership in Health Services, 28(4), 298–316. 10.1108/LHS-08-2014-0061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter, A. , von Thiele Schwarz, U. , Lornudd, C. , Lundmark, R. , Mosson, R. , & Hasson, H. (2016). iLead‐a transformational leadership intervention to train healthcare managers' implementation leadership. Implementation Science, 11, 108. 10.1186/s13012-016-0475-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett, D. L. , Rosenberg, W. M. , Gray, J. A. , Haynes, R. B. , & Richardson, W. S. (1996). Evidence based medicine: What it is and what it isn't. BMJ, 312(7023), 71–72. 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shuman, C. J. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Torres, E. M. , Veliz, P. , Kath, L. M. , VanAntwerp, K. , Banaszak‐Holl, J. , Titler, M. G. , & Aarons, G. A. (2020). EBP implementation leadership of frontline nurse managers: Validation of the Implementation Leadership Scale in acute care. Worldviews on Evidence‐Based Nursing, 17(1), 82–91. 10.1111/wvn.12402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, V. D. , & Rojjanasrirat, W. (2011). Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross‐cultural health care research: A clear and user‐friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract, 17(2), 268–274. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus, S. E. (2019). Evidence‐based medicine : How to practice and teach EBM, 5th ed. Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Streiner, D. L. (2008). Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use (pp. 248–270). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, E. M. , Ehrhart, M. G. , Beidas, R. S. , Farahnak, L. R. , Finn, N. K. , & Aarons, G. A. (2018). Validation of the Implementation Leadership Scale (ILS) with Supervisors' Self‐Ratings. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(1), 49–53. 10.1007/s10597-017-0114-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Välimäki, T. , Partanen, P. , & Häggman‐Laitila, A. (2018). An integrative review of interventions for enhancing leadership in the implementation of evidence‐based nursing. Worldviews on Evidence‐based Nursing, 15(6), 424–431. 10.1111/wvn.12331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng, Y. H. , Kuo, K. N. , Yang, C. Y. , Lo, H. L. , Chen, C. , & Chiu, Y. W. (2013). Implementation of evidence‐based practice across medical, nursing, pharmacological and allied healthcare professionals: A questionnaire survey in nationwide hospital settings. Implementation Science, 8, 112. 10.1186/1748-5908-8-112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia, R. , Hu, X. , Willcox, M. , Li, X. , Li, Y. , Wang, J. , Li, X. , Moore, M. , Liu, J. , & Fei, Y. (2019). How far do we still need to go? A survey on knowledge, attitudes, practice related to antimicrobial stewardship regulations among Chinese doctors in 2012 and 2016. British Medical Journal Open, 9(6), e027687. 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.