Abstract

Empirically, α-helical membrane protein folding stability in surfactant micelles can be tuned by varying the mole fraction MFSDS of anionic (sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)) relative to nonionic (e.g., dodecyl maltoside (DDM)) surfactant, but we lack a satisfying physical explanation of this phenomenon. Cysteine labeling (CL) has thus far only been used to study the topology of membrane proteins, not their stability or folding behavior. Here, we use CL to investigate membrane protein folding in mixed DDM-SDS micelles. Labeling kinetics of the intramembrane protease GlpG are consistent with simple two-state unfolding-and-exchange rates for seven single-Cys GlpG variants over most of the explored MFSDS range, along with exchange from the native state at low MFSDS (which inconveniently precludes measurement of unfolding kinetics under native conditions). However, for two mutants, labeling rates decline with MFSDS at 0–0.2 MFSDS (i.e., native conditions). Thus, an increase in MFSDS seems to be a protective factor for these two positions, but not for the five others. We propose different scenarios to explain this and find the most plausible ones to involve preferential binding of SDS monomers to the site of CL (based on computational simulations) along with changes in size and shape of the mixed micelle with changing MFSDS (based on SAXS studies). These nonlinear impacts on protein stability highlights a multifaceted role for SDS in membrane protein denaturation, involving both direct interactions of monomeric SDS and changes in micelle size and shape along with the general effects on protein stability of changes in micelle composition.

Significance

Mixed micelles of sodium dodecyl sulfide (SDS) and nonionic surfactants are useful tools to monitor membrane protein stability because destabilization scales with the mole fraction of SDS. Here, we combine mixed micelles with Cys-labeling kinetics to monitor stability of the membrane protein GlpG. Under native conditions, the native state is labeled more rapidly than the protein unfolds, precluding direct measurement of unfolding kinetics. However, at low SDS mole fractions, several Cys residues are stabilized against labeling. We rationalize these observations as a combination of factors. MD simulations suggest specific SDS binding as stabilizing ligands to certain areas of GlpG, whereas SAXS indicates micelle changes under these conditions. We conclude that anionic surfactants have complex effects on membrane proteins at low mole fractions.

Introduction

Integral α-helical membrane proteins, which have evolved to communicate material and information across lipid membranes, are only stable in the presence of a lipid membrane or a membrane-mimicking environment. An elaborate cellular machinery ensures that the nascent chains of helical membrane proteins are transferred directly from the ribosome into the plasma membrane as the proteins are being synthesized such that the N-terminal part is inserted first and the C-terminal part last (1,2). There has been significant progress in our understanding of the biochemical machinery and biophysical principles that orchestrate this process (3,4), but the level of insight into the physical-chemical basis for these steps and for the stability of the ensuing native state N is far from the level reached for globular proteins (5,6). This gap reflects the challenges involved in working with membrane proteins, which generally are expressed at much lower levels than their water-soluble counterparts because of the limited capacity of the cell membrane, aggregate more easily because of their pronounced hydrophobicity, and are often more difficult to reconstitute as a result of large activation barriers to the insertion into phospholipid membranes (7,8). Once inside the membrane, membrane proteins largely remain in a folded state; the hydrophobic environment of the phospholipid bilayer is a very poor solvent for the unfolded state, providing no alternative hydrogen bonding partners in the hydrocarbon milieu. Even dissociation of individual helices is disfavored because of stabilizing protein-protein interactions at helical interfaces and the relatively poor packing abilities of the large and bulky lipid groups. Thus, despite recent progress in, e.g., monitoring intermolecular membrane protein interactions (9), we still lack a complete thermodynamic description of the folding and unfolding of membrane proteins within membrane-mimicking environments such as synthetic phospholipid membranes, let alone a fully functional plasma membrane.

A first approximation to a membrane-like environment may be made by the use of mixed micelles composed of varying amounts of a nonionic and ionic surfactant pairs, most typically dodecyl maltoside (DDM) and the anionic surfactant sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) (10). Although far from a proper membrane bilayer, the DDM-SDS pair effectively solubilizes most membrane proteins through the formation of mixed micelles, which—unlike many other surfactant pairs—behave essentially ideally, i.e., their molecular composition largely follows the bulk distribution of the two surfactants (11). DDM favors N, whereas SDS tends to disrupt the helical assembly and form more or less isolated helices, which may be considered a reasonable model for the denatured state D (12). Furthermore, previous studies have noted a quantitative relationship between the mole fraction of SDS (MFSDS = [SDS]/([DDM] + [SDS]) and the extent of unfolding, which has been modeled as a linear relationship between the free energy of folding (ΔGD-N) and MFSDS (13). Thus, membrane proteins may be incubated at different MFSDS, and their degree of folding ascertained by techniques such as cofactor binding, fluorescence spectroscopy, or protease resistance. Using this approach, the folding of membrane proteins such as the proton pump bacteriorhodopsin (14,15), the disulfide-bond reducing protein DsbB (16,17), and the rhomboid protease GlpG (18) has been modeled according to a simple two-state scheme involving only N and D under equilibrium conditions. Kinetic studies monitoring the rates of folding and unfolding have expanded these schemes to include transient folding (bacteriorhodopsin) and unfolding (DsbB) intermediates, whereas the study of GlpG’s folding did not reveal any such intermediates. Besides delineating general features of the folding pathway, mixed micelles have been combined with protein engineering and φ-value analysis (19) to reveal residue-level structures of the transition state of folding of these proteins. A comprehensive study of GlpG, which contains six transmembrane helices (TM1–6) as well as two interfacial helices, indicated that the folding nucleus was largely confined to the two N-terminal helices, whereas the four C-terminal helices were essentially unstructured (i.e., without native-like interhelical contacts) (18). In this analysis, numerous residues showed anomalous behavior: mutations that were shown to destabilize the folded state also accelerate the folding transition. Although these anomalous φ-values were initially ascribed to non-native interactions in the transition state, later molecular dynamics simulations using a model that lacks non-native interactions showed that the observed increases in the folding rate upon making mutations that are destabilizing to N could be explained by backtracking, i.e., undoing of native-like substructures during the rate-limiting step when going from D to N (20).

Given the ultimate goal of measuring and understanding membrane protein thermodynamics in the membrane, we wish to use mixed micelles as a testing ground for biophysical techniques that are compatible with the more complex membrane environment. One such approach is Cys labeling, which is based on the premise that a Cys residue can react with a fluoro- or chromophore (leading to a change in fluorescence or absorption) only if it is accessible, i.e., placed in a part of the protein that is solvent exposed. Thus, Cys residues that are buried in N will only become reactive if the protein undergoes a conformational transition through either local or global unfolding. Cys labeling has been used to analyze structural changes in both globular proteins (21, 22, 23, 24) and membrane proteins (25, 26, 27), e.g., when the protein is exposed to a denaturant. The extent of labeling tells us the fraction of Cys residues that are labeled at any given moment, and the rate of labeling under different conditions provides information about the dynamics of conformational transitions. A particularly sophisticated study has been carried out by Udgaonkar and colleagues, who were able to reconstruct the folding mechanism of barstar based on the rates of labeling over a range of denaturant concentrations, allowing them to assess unfolding rates under conditions in which direct measurements based on endogenous Trp fluorescence were not possible (21). A further advantage of Cys labeling over other techniques is that Cys residues can be introduced using standard protein engineering techniques, allowing for residue-level resolution, to compare transitions in different regions of a given protein. The presence of micelles introduces an additional layer of complexity, e.g., a dependence of the exchange rate on MFSDS. Ultimately, such an approach can be used to measure dynamics of folding and unfolding in the membrane, provided that we understand how the membrane environment directly influences Cys-labeling kinetics. In particular, it is necessary to gauge whether Cys residues are truly accessible in D or are shielded by surrounding surfactant or lipid molecules to an extent that significantly diminishes reactivity.

Here, we report on the use of Cys labeling with the chromophore dithionitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) to probe the dynamics of folding and unfolding of GlpG. GlpG naturally has one Cys residue in position 104 in the first transmembrane helix. Thus, wild-type (WT) GlpG can be used to probe the accessibility of the first helix. Cys104 is then replaced by Val to provide a substitution that is as isosteric as possible. To probe the accessibility of the other helices, on a C104V background, we then introduce single Cys residues into each of the six helices at positions M100, L155, S181, V211, G240, and V260, all of which are buried in N according to a crystal structure of GlpG (Protein Data Bank: 2XOV (28)) (Fig. 1). We first ascertain the thermodynamic stability of these eight proteins by monitoring their endogenous Trp fluorescence at 32 different MFSDS values between 0 and 0.8 MFSDS, after which we measure the rate of reaction of the seven Cys-containing mutants with DTNB at each of these MFSDS values (using the Cys-free C104V as a negative control). The data are fitted to a model for chemical exchange in which both the N and D state can exchange (although at different rates), yielding equilibrium constants for unfolding. Because of exchange from the N state, we cannot obtain the kinetics of unfolding at low MFSDS, but the data indicate that the rate of exchange from N is dependent on the micelle composition and is for some variants actually accelerated at low MFSDS. For a selection of these GlpG variants (WT, C104V, V211C, and V260C), we also measure the kinetics of folding and unfolding directly, using stopped flow to investigate possible reasons for this behavior, but do not find this to provide an explanation for the equilibrium changes in stability. Computational studies highlight hotspots for SDS binding in mixed micelles, which may partially explain the nonlinear (stabilizing) effects of SDS at low MFSDS. In addition, small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS) shows that the mixed micelles undergo a nonlinear change in size and shape over a broad MFSDS range which may also affect the stability of the embedded membrane protein. All this highlights a more complex role for SDS as an effector of membrane protein stability in mixed micelles.

Figure 1.

Structure of GlpG (Protein Data Bank: 2NRF) highlighting the seven residues for which Cys either occurs in WT (position 104) or is introduced individually by site-directed mutagenesis in a Cys-free (C104V) background. Numbers indicated residues for which Cys was introduced (same color as the corresponding side chain). Figure generated in Pymol. To see this figure in color, go online.

Materials and methods

This is provided in the Supporting materials and methods and provides details about the chemicals used, protein expression and purification, choice of chromophore for Cys labeling, equilibrium Trp fluorescence and DTNB absorption studies, stopped-flow kinetics, SAXS, and molecular dynamics simulations of GlpG-micelle systems. Briefly, an N-terminally truncated GlpG construct with an N-terminal His6 tail was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified by nickel-nitrilotriacetate (Ni-NTA) chromatography. Three fluorophores were rejected for Cys-labeling experiments because of spectroscopic properties incompatible with micelle assays, and the chromophore DTNB was selected instead. Equilibrium Trp fluorescence of GlpG variants and DTNB absorption changes were both recorded on a plate reader with injection function. This provided parameters for the unfolding of GlpG at increasing MFSDS and time courses in the form of double-exponential decays accompanying DTNB labeling. Stopped-flow kinetics involved rapid mixing of GlpG variants with different MFSDS monitored by Trp fluorescence, leading to rate constants of folding and unfolding at MFSDS of 0.025–0.95. SAXS scattering curves were collected for protein-free mixed micelles of SDS and DDM at MFSDS from 0 to 1 and fitted on absolute scale with a core-shell model. Molecular dynamics simulations included building three different GlpG-micelle systems (involving one GlpG with either 176 DDM molecules and 80 SDS molecules or 158 and 8 DDM and SDS molecules) with CHARMM-GUI (www.charmm-gui.org) and the Gromacs package with an all-atom force field, followed by energy minimization. The GlpG-micelle system was then subjected to 500-ns simulations, and the last 200 ns were used to compute the extent of SDS-GlpG contacts.

Results

Equilibrium Trp fluorescence indicates a major unfolding transition at 0.3–0.6 MFSDS as well as minor changes <0.1 MFSDS

The GlpG construct that we studied (Fig. 1) contains 11 Trp residues that are distributed throughout the protein, with at least one Trp in each transmembrane helix except TM3 and TM6 and three Trp residues in the large loop between helix 1 and 2. Thus, changes in Trp fluorescence report globally on conformational transitions. We recorded equilibrium intrinsic Trp fluorescence emission spectra for all eight single-Cys variants over 0.0–0.8 MFSDS (examples of spectra shown in Fig. S1 A). All emission spectra have a peak roughly centered around 330 nm, but the change in intensity at 330 nm follows a rather broad transition over the whole MFSDS range. Similarly broad transitions have been observed for other membrane proteins (17). However, a clearer transition emerges when we condense each emission spectrum to a single value in the form of the intensity-weighted average wavelength <λ> (Eq. S1) and plot this value versus MFSDS in Fig. 2. For all variants, we observe a sharp unfolding transition at intermediate values of MFSDS (0.3–0.6); however, an additional apparent unfolding transition can be seen <0.1 MFSDS (although it is not immediately obvious from the raw spectra in, e.g., Fig. S1 A and only to a small extent in the normalized data, cf. Fig. S1, B and C). We attribute the ability to detect these transitions so relatively clearly in our measurements to the use of a plate reader, which allows the collection of highly reproducible data (in contrast to the single-cuvette measurements used previously), as well as to the use of a truncated construct of GlpG that lacks the N-terminal cytoplasmic domain (which itself contains two additional Trp residues). This cytoplasmic domain was included in our previous work (18).

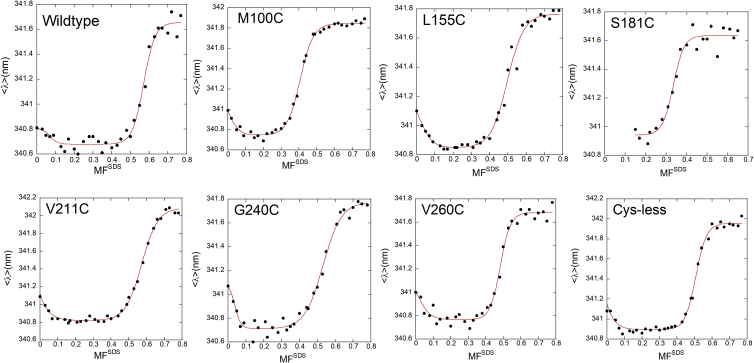

Figure 2.

Intensity-weighted average Trp emission wavelength data points (black circles, Eq. S1) as a function of MFSDS for WT and seven variants of GlpG, of which one (C104V) is without Cys residues. Increases of the intensity-weighted average Trp emission wavelength above the baseline values are clearly observed for all variants at intermediate MFSDS values and for most variants at low MFSDS values. This indicates deviations from a simple two-state unfolding model. Red lines indicate fits to a three-state model for unfolding N ↔ N∗ ↔ D (Eq. S4), where N∗ is a quasinative state. However, the N ↔ N∗ transition is incomplete and does not allow us to determine the associated stability parameters with sufficient certainty. Data associated with the much more well-defined major transition (corresponding to the N∗ ↔ D step in the three-state model) are provided in Table 1. To see this figure in color, go online.

At face value, these plots suggest that GlpG might undergo two transitions, one (between N and another species tentatively called N∗) at very low MFSDS and another (between N∗ and D D) at the previously observed high MFSDS values. The first transition is, however, incomplete because no baseline is observed before the decline in signal. It is therefore not possible to conclude whether the shift in <λ> from 0 MFSDS onwards corresponds to a transition from a population of ∼100% N to N∗ or from a mixture of N and N∗, i.e., it is not possible to determine the extent of accumulation of N vs. N∗. Furthermore, the change in <λ> is not matched by a consistent change in fluorescence intensity, which undergoes different fluctuations for different variants in this MFSDS range (Fig. S1, D–H). Nevertheless, as demonstrated in Fig. 2, the equilibrium data for all six mutants besides WT and S181C can formally be fitted to a three-state transition N ↔ N∗ ↔ D (Eq. S4), but the errors on the parameters associated with the N ↔ N∗ transition are much too large for the parameters to be of actual use. In contrast, the main transition is fitted very well in a simple two-state system to yield well-constrained parameters in which the errors on the mD-N value and midpoint denaturation value MFSDS,50% are around 10 and 1%, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Stability parameters obtained from equilibrium denaturation of WT GlpG and different mutants, monitored by Trp fluorescence

| Parametera,b | WT | M100C | L155C | S181C | V211C | G240C | V260C | Cys-less |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SN (nm) | 340.69 ± 0.01 | 340.74 ± 0.01 | 340.85 ± 0.02 | 340.94 ± 0.03 | 340.82 ± 0.01 | 340.72 ± 0.01 | 340.77 ± 0.01 | 340.89 ± 0.01 |

| SD (nm) | 341.65 ± 0.03 | 341.84 ± 0.01 | 341.76 ± 0.02 | 341.64 ± 0.02 | 342.09 ± 0.02 | 341.77 ± 0.03 | 341.68 ± 0.02 | 341.96 ± 0.01 |

| mD-N | 14.85 ± 2.18 | 11.84 ± 0.58 | 9.71 ± 1.19 | 16.53 ± 3.76 | 9.63 ± 0.47 | 8.61 ± 0.91 | 15.22 ± 1.67 | 14.11 ± 0.99 |

| MFSDS, 50% | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.41 ± 0.01 | 0.50 ± 0.01 | 0.33 ± 0.01 | 0.57 ± 0.01 | 0.53 ± 0.01 | 0.48 ± 0.01 | 0.51 ± 0.01 |

| log KD-NnoSDSc | −8.50 ± 1.25 | −4.82 ± 0.24 | −4.83 ± 0.59 | −5.53 ± 1.26 | −5.53 ± 0.27 | −4.59 ± 0.49 | −7.37 ± 0.81 | −7.17 ± 0.50 |

All data measured at 25°C in buffer B (360 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.0)).

Equilibrium denaturation parameters as used in Eq. S2 and based on a two-state unfolding model (N ↔ D) which discards the initial spectroscopic changes observed at low MFSDS.

Calculated as log KD-Nno SDS = MFSDS,50% × mD-N.

To further investigate the origin of this spectroscopic change and its possible link to conformational transitions, we turned to a kinetic analysis of the unfolding of GlpG, starting with stopped-flow kinetics monitored by endogenous Trp fluorescence.

Stopped-flow kinetics measurements reveals a transient off-pathway folding intermediate

We started out by measuring relaxation folding and unfolding rates by stopped-flow mixing kinetics over a wide MFSDS range for four of the eight GlpG variants. The log of the observed relaxation rates is plotted versus MFSDS in Fig. 3. As described in more detail in the Supporting materials and methods, we observe a “rollover” (deviation from linearity) at low MFSDS, which can be ascribed to a transient off-pathway intermediate I according to the scheme I ↔ D ↔ N (data summarized in Table 2). However, the intermediate is not predicted to be populated significantly under equilibrium conditions and can therefore not directly be coupled to the spectroscopic changes observed at low MFSDS under equilibrium conditions (Fig. 2). For other two-state proteins such as S6, which are known to accumulate such transient species during folding, single-molecule studies do not detect such compact but non-native states to any significant extent at equilibrium (29). Because analysis of these four variants did not resolve the spectroscopic changes observed at low MFSDS, we decided not to investigate the remaining four variants. Instead, we examined the unfolding of GlpG under both native and denaturing conditions by measuring the kinetics of Cys labeling under equilibrium conditions.

Figure 3.

Stopped-flow kinetics data based on changes in intrinsic Trp fluorescence, showing measured rate constants for refolding and unfolding for WT GlpG and three different mutants (black circles). Red lines indicate best fits to a three-state folding mechanism I ↔ D ↔ N, where I is an off-pathway intermediate (Eq. S6). Data are summarized in Table 2. To see this figure in color, go online.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters obtained from fitting stopped-flow kinetics data to a three-state model for unfolding

| Parametera,b | WT GlpG | V211C | Cys-less (C104V) | V260C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log kfno SDS | −0.37 ± 0.33 | −1.70 ± 0.21 | 0.07 ± 1.61 | −0.40 ± 0.07 |

| mf (M−1) | −3.99 ± 0.75 | −1.07 ± 0.52 | −5.74 ± 3.65 | −5.42 ± 0.33 |

| log KIno SDS | 1.94 ± 0.31 | 0.78 ± 0.20 | 2.37 ± 1.58 | ≡ 2c |

| mI (M−1) | −7.11 ± 0.48 | −7.45 ± 2.31 | −6.51 ± 3.03 | ≡ −7c |

| log kuno SDS | −5.74 ± 0.18 | −6.01 ± 0.33 | −5.59 ± 0.20 | −4.99 ± 0.17 |

| mu (M−1) | 5.85 ± 0.22 | 6.05 ± 0.38 | 6.02 ± 0.25 | 5.42 ± 0.22 |

| log KD-NnoSDSd | −5.37 ± 0.38 (−5.43 ± 0.15e) | −4.30 ± 0.39 | −5.66 ± 1.63 | −4.59 ± 0.18 |

| mD-Nf | 9.84 ± 0.79 (−9.04 ± 0.56e) | 7.12 ± 0.65 | 11.77 ± 3.66 | 10.84 ± 0.40 |

| log KD-NnoSDSf | −8.50 ± 1.25 | −5.53 ± 0.27 | −7.37 ± 0.81 | −7.17 ± 0.50 |

| mD-Ne | 14.85 ± 2.18 | 9.63 ± 0.47 | 15.22 ± 1.67 | 14.11 ± 0.99 |

All data measured at 25°C in buffer B (360 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.0)).

Defined in Eq. S3 describing the folding model C ↔ D ↔ N.

Very weak downturn made it unfeasible to determine these parameters. Instead, they were locked to values similar to those of the three other mutants.

Calculated as log KD-Nno SDS = log kuno SDS − log kfno SDS and mD-N = mu − mf.

From previous stopped-flow kinetics work on WT GlpG (18).

Obtained from equilibrium denaturation data (Table 1). Included for comparison.

Cys-labeling kinetics shows a nonmonotonic dependence on MFSDS

We decided to introduce single Cys residues at positions that are buried in the folded structure. This should allow us to measure unfolding kinetics by Cys labeling at very low MFSDS, at which N is the dominant species and unfolding cannot be measured by conventional bulk spectroscopic approaches. We hoped that this would allow us to detect deviations from two-state unfolding under these conditions. Such an approach presupposes that only the unfolded state is sufficiently accessible to undergo Cys labeling or that the population of denatured states was labeled significantly faster than its native-state counterpart. Unfortunately, as we will see below, this assumption turns out to be invalid and therefore severely limits the conclusions that can be drawn. The single significant rate constant obtained from Cys-labeling studies limits us to simple modeling of the folding and unfolding-and-exchange processes and the dependence of these processes on MFSDS.

We subjected all seven Cys-containing variants described in the Introduction to Cys-labeling experiments. As described in the Supporting materials and methods, the conventional chromophore DTNB, commonly used to assess the concentration of free Cys residues (30), turned out to be superior to thiol-reactive fluorophores, which either gave rise to significant unspecific signals or were too unreactive. Even with DTNB, however, we encountered background signals (see Supporting materials and methods and Fig. S2 for details). In our subsequent analysis, we limit our analysis to a single major slow phase of labeling (with a rate constant referred to as kobs, shown for all seven Cys-labeled variants in Fig. 4 and depicted as an idealized function of denaturant conditions in Fig. 5 A, see below). We also confirmed that the upper limit for rate of exchange of Cys residues corresponded to the rate of exchange of a single (and thus more freely accessible) peptide, corresponding to the sixth transmembrane helix of GlpG (see Materials and methods for details along with data in Figs. 5 B and S3 A).

Figure 4.

The observed rate of Cys labeling as a function of MFSDS for all seven Cys-containing variants of GlpG. The measured rates are plotted with black circles, and the fits obtained using Eqs. 1 and 2 are shown with red lines. Data are summarized in Table 3. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 5.

(A) Simulation of the three different linear regimes predicted from Eqs. 1 and 2 using typical values from Table 3. (B) Exchange rate constants for the TM6-Cys peptide plotted alongside corresponding values for full-length WT GlpG and the mutant V211C. Clearly, the rate of exchange of the peptide corresponds to the rate of exchange in D of V211C. To see this figure in color, go online.

Cys-labeling rates are consistent with a two-state unfolding scheme

The log of the observed labeling rate constants vary smoothly with MFSDS (Fig. 4). For each variant, there is a plateau level in the lower MFSDS range, in some cases with a downward slope at very low MFSDS values (particularly clear for V211C and G240C). This is followed by a distinctive rise in the labeling rate over a range of MFSDS values that corresponds to the main unfolding transition observed in the equilibrium fluorescence data, after which the rate stabilizes at a plateau level, sometimes accompanied by a small linear decline. This indicates that there are three distinct regimes in which Cys labeling takes place. The simplest interpretation (as indicated in Fig. 5 A) is that regimes 1–3 correspond respectively to 1) labeling of N limited by the rate of labeling of N , 2) labeling of D limited by the extent of denaturation, and 3) labeling of D limited by the rate of labeling of D . We analyze the labeling data using an exchange scheme depicted in Fig. 6.

Figure 6.

Rate constants associated with the labeling of GlpG by DTNB, either via the native state N or the denatured state D

Here, -SH and -S-TNB refer to the unlabeled and labeled state, respectively. This approach is directly based on the formalism developed for hydrogen-deuterium exchange (31,32), as the same reversible folding/unfolding transition and irreversible exchange steps apply as for Cys labeling. In the classical hydrogen-deuterium model, exchange of H (protium) for D (deuterium) only occurs when the protein opens (unfolds) to a state in which the exchangeable proton is no longer involved in internal hydrogen bonding, as the folded or hydrogen-bonded state does not undergo exchange to any significant extent. Similarly, unfolding of GlpG will lead to much greater exposure of the Cys residue and subsequent reaction with DTNB. However, as we will see below, the data also indicate that it is possible to exchange (i.e., Cys label) the N state, but only when N dominates the population ( > because D will be much more accessible to reactive DTNB and therefore more reactive than N). In practice, this means that it is not possible to derive any information about the extent of unfolding at very low MFSDS, as the very low population levels of D under these conditions allow N to pull ahead in the labeling “race.”

Under conditions in which the labeling agent (here DTNB) is in excess over protein (clearly the case here, as we use 1 mM DTNB and 6 μM GlpG), the following equation describes how the rate constant of labeling is affected by the different rate constants in Fig. 6:

| (1) |

Unlike the original hydrogen-deuterium exchange equation (33), Eq. 1 also includes the term to take into account exchange from N, as the term is the fraction of the time that GlpG spends in the N state from which it can exchange (i.e., react with Cys) at rate .

Equation 1 leads, in practice, to the three different regimes seem in Figs. 4 and 5, depending on 1) whether N dominates over D or vice versa and 2) the relative magnitudes of ku and :

-

1)

Very low MFSDS: . Under these conditions, [N] >> [D], and essentially all the protein will be in the N state, so kf >> ku, ≈ 1, and kf >> , meaning that because KD-N << 1, so kobs ≈ . In other words, this represents conditions in which exchange from (i.e., labeling of) N dominates over that from D.

-

2)

Intermediate MFSDS: kf > ku (i.e., the protein is still predominantly in the N state, corresponding to MFSDS < MFSDS,50%, the concentration at which 50% of GlpG is folded) and kf > kintD (i.e., the protein once unfolded tends to return to N before being labeled). However, now KD-N has increased sufficiently that . This leads to kobs ≈ , corresponding to the well-known EX2 limit.

-

3)

ku > kf (i.e., the protein is predominantly in D) and ku > (which in practice occurs ∼0.1 unit above MFSDS,50%). This reduces Eq. S1 to kobs ≈ , i.e., a situation in which the intrinsic labeling step is rate limiting.

(The EX1 situation in which kintD > ku > kf, leading to kobs ≈ ku, does not occur in practice; under these conditions, log kobs would continue to increase linearly with MFSDS).

Consistent with previous analyses of membrane protein stability in mixed micelles (10,18), we will assume that all three rate constants show a linear dependence on MFSDS as described by the constant mx:

| (2) |

In conventional chemical denaturation, the m-value (which is related to the ability of denaturant to bind unspecifically to the protein surface (34)) is traditionally interpreted as being proportional to the extent of surface exposure upon unfolding (33). When micelles are involved, as with GlpG, this becomes more complicated because of the possibility of specific binding of individual surfactant molecules, particularly SDS. However, the parameter can, to a first approximation, be interpreted in an analogous fashion (17).

All our labeling data can be fitted to the original Eq. 1 in combination with Eq. 2. However, we are unable to determine all four rate constants and their associated m-values in Scheme 1 from this fit. As shown in a simulated plot in Fig. 5 A, the three conditions described above lead to three linear stretches when log kobs is plotted versus MFSDS (red, green, and blue in Fig. 5 A). The red line has an intercept of log and a slope of mintN, the green stretch a slope of (mu + − mf = mD-N + ) and an intercept of (log + log − log = log + log ), and the blue one has a slope of and an intercept of log . Thus. separate fitting of the three linear stretches (in which the blue stretch’s value of log and is used when subsequently fitting the green stretch) allows unequivocal determination of exchange rates from N and D (log and log ), equilibrium stability (log ), and their corresponding m-values. In other words, we can relatively robustly determine KD-N = ku/kf, but not the two individual rate constants. Global fitting of the entire stretch to Eq. 1 (which has four rate constants and four m-values) requires separate information about kf and mf from other sources because the different approximations in regimes 1–3 obviously do not apply globally. In practice, we lock the values log kfDDM and mf-values from direct measurements in stopped-flow experiments (in the case of WT GlpG (18)) or from a closely related mutant (M100A and L155A), or we use the WT values (S181C, V211C, G240C, V260C). We emphasize that we do not directly use these derived rate constants, which in any case are more reliable when combined as KD-N. The six sets of variables (log ku, log kintD, and log kintC and associated m-values), along with the constrained values for kfno SDS and mf and the calculated values of KD-N, are summarized in Table 3. Overall, there is a reasonable agreement between the log KD-N values obtained by the different methods, and in all cases WT is the most stable of the different GlpG variants probed (though very similar in stability to the Cys-less mutant). There is more variation with regards to mD-N values, which in any case are associated with considerable uncertainty as a derivative parameter and typically have errors 5- to 10-fold higher than a directly determined parameter such as the midpoint of denaturation or the intercept of folding (cf. Table 1). Although the data are consistent with a simple two-state unfolding scheme in combination with exchange from both end states, we must emphasize that the apparent ability of N to undergo Cys labeling is a significant limitation to our analysis because it prevents us from directly determining the extent of unfolding at low MFSDS. Also, we do not need to invoke the existence of a separate native-like species like N∗ to model our Cys-labeling data. In all cases, the Cys-labeling data nicely predict that N accumulates (consistent with linear relationships between log KD-N and MFSDS as in Eq. 2) as the MFSDS values decrease below the midpoint of denaturation and eventually become sufficiently populated to take over as main contributor to the labeling output.

Table 3.

Kinetic and equilibrium parameters obtained from fitting Cys-labeling kinetics data to a model involving exchange from both the native and D states in Scheme 1

| Parametersa,b | WT | M100C | L155C | S181C | V211C | G240C | V260C |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| log kfno SDS | ≡ −1.56c | −2.15d | ≡ −1.53e | ≡ −1.56c | ≡ −1.56c | ≡ −1.56c | ≡ −1.56c |

| mf | ≡ −2.11d | −1.8e | ≡ −2.54f | ≡ −2.11c | ≡ −2.1cc | ≡ −2.11c | ≡ −2.11c |

| log kuno SDS | −8.04 ± 0.34 | −6.83 ± 0.17 | −6.42 ± 0.17 | −4.60 ± 0.12 | −7.04 ± 0.11 | −6.60 ± 0.50 | −5.98 ± 0.21 |

| mu | 9.30 ± 0.70 | 9.85 ± 0.55 | 7.49 ± 0.36 | 8.01 ± 0.58 | 7.39 ± 0.25 | 8.40 ± 1.30 | 6.50 ± 0.53 |

| log KD-Nno SDS | −6.48 ± 0.34 | −4.68 ± 0.17 | −4.89 ± 0.32 | −3.04 ± 0.19 | −5.48 ± 0.12 | −5.04 ± 0.50 | −4.42 ± 0.21 |

| mD-N | 11.41 ± 0.71 | 11.65 ± 0.59 | 10.03 ± 0.87 | 10.12 ± 0.65 | 9.50 ± 0.29 | 10.51 ± 1.31 | 8.61 ± 0.55 |

| log KD-Nno SDSg | −8.50 ± 1.25 | −4.82 ± 0.24 | −4.83 ± 0.59 | −5.53 ± 1.26 | −5.53 ± 0.27 | −4.59 ± 0.49 | −7.37 ± 0.81 |

| mD-Ng | 14.85 ± 2.18 | 11.84 ± 0.58 | 9.71 ± 1.19 | 16.53 ± 3.76 | 9.63 ± 0.47 | 8.61 ± 0.91 | 15.22 ± 1.67 |

| log KD-Nno SDSh | −5.37 ± 0.38 | N/A | N/A | N/A | −4.30 ± 0.39 | N/A | −4.59 ± 0.18 |

| mD-Nh | 9.84 ± 0.79 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 7.12 ± 0.65 | N/A | 10.84 ± 0.40 |

| log kint,D, no SDS | −3.33 ± 0.31 | −2.69 ± 0.11 | −2.72 ± 0.21 | −2.65 ± 0.08 | −2.67 ± 0.04 | −3.50 ± 0.30 | −2.65 ± 0.06 |

| log kint,D, 0.6 MFc | −4.22 ± 0.02 | −3.87 ± 0.04 | −3.66 ± 0.03 | −3.34 ± 0.02 | −2.67 ± 0.04 | −4.20 ± 0.05 | −2.65 ± 0.06 |

| mint,D | −1.48 ± 0.44 | −1.97 ± 0.16 | −1.56 ± 0.31 | −1.15 ± 0.13 | ≡ 0i | −1.17 ± 0.44 | ≡ 0i |

| log kint,N, no SDS | −5.66 ± 0.04 | −5.26 ± 0.04 | −5.68 ± 0.03 | −4.84 ± 0.06 | −4.81 ± 0.04 | −4.57 ± 0.07 | −5.21 ± 0.08 |

| mint,N | −0.22 ± 0.21 | −1.22 ± 0.47 | ≡ 0 | ≡ 0 | −4.81 ± 0.41 | −2.74 ± 0.45 | −0.98 ± 0.96 |

N/A, not applicable.

All data measured at 25°C in buffer B (360 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 25 mM MOPS (pH 7.0)).

Intrapolated to 0.6 MFSDS (region of measurement).

Constrained to WT values obtained from stopped-flow studies (18).

Constrained to values for M100A obtained from stopped-flow studies (18).

Constrained to values for L155A obtained from stopped-flow studies (18).

Obtained from equilibrium denaturation experiments based on Trp fluorescence (Fig. 1; Table 1). Included for comparison.

Set to 0 because of short baseline.

GlpG undergoes surprising and residue-specific changes in the rate of exchange at low MFSDS

Given the limited information on folding and unfolding rates from these data, it is perhaps of greater interest to inspect the values of intrinsic labeling of the N and D states at different Cys positions (Table 3). For more robust analysis, we have interpolated kintD-value (which are usually based on values obtained between 0.5 and 0.8 MFSDS) to 0.6 MFSDS to reduce error-prone extrapolation. D generally exchanges 30- to 100-fold faster than N as one would expect for a significantly more accessible state. There is an ∼30-fold variation in kintD-values across the mutants, which no doubt reflects residual structure in the D state and/or the position of the residues within the micellar environment. It is, however, noteworthy that the associated m-values for exchange from D are all of comparable value for the different mutants, indicating that the accessibilities or reactivities of the residues change to the same extent in the denaturation range in which they are directly measured.

For N, there is an ∼10-fold variation in kintN, ranging from the slowest (WT and L155C) to the fastest (G240C). This is relatively modest and to some extent reflects local variations in accessibility. All Cys residues have been placed in residues that are largely buried in N except for Gly240, which is in a loop between TM5 and TM6. Molecular dynamics (MD) studies of the surface accessibilities of Cys residues inserted individually into the six mutated residues and simulated in three independent 500-ns runs (see Supporting materials and methods) confirm that Cys240 is significantly more exposed than the other residues. Cys240 shows an average surface accessibility (ignoring surfactant molecules) of 33 ± 5 Å2, whereas the others range from 12 ± 7 (Cys181), 14 ± 3 (both Cys155 and Cys211), and 18 ± 5 (Cys260) to 23 ± 5 Å2 (Cys100). However, apart from G240C, the ranking of the accessibilities of the different residues do not reproduce the ranking in kintN among the six mutants, indicating that these MD simulations do not satisfactorily reproduce experimental rates of exchange.

Remarkably, mintN-values show a greater variation than mintD-values. Five of the mutants have mintN-values that are close to zero (WT, M100C, and G260C) or cannot be determined accurately because of a relatively short native-state baseline region (L155C and S181C), but two variants (V211C and G240C) show a robustly large and negative mintN-value. These variations across GlpG are possibly the most striking aspects of our Cys-labeling analysis. mintD-values are uniformly negative (except for V211C andV260C, for which a short denatured-state baseline prevents a reliable estimate), indicating that increasing MFSDS tends to suppress exchange kinetics.

Negative mintD-values may reflect electrostatically unfavorable accumulation of negative charge (TNB−) during the reaction with DTNB in increasingly anionic SDS-DDM micelles. The negative mintN-values for V211C and G240C are more difficult to explain. Although there may be differences in local susceptibility to Cys labeling, one would intuitively expect increasing amounts of SDS at low MFSDS to increase local dynamics or breathing of GlpG (not to be confused with global unfolding, which is negligible at low MFSDS) and thus promote exchange. The low density of SDS in the mixed micelles under these conditions would not be expected to inhibit the mechanism of the labeling reaction or at the very least lead to comparable changes for different mutants. This is obviously not the case. We will spend the rest of the Results section discussing possible reasons for this variation.

Scenario I: a separate quasinative state

Let us consider a more compact and less exchange-accessible N∗ state (which appears to accumulate for all mutants, according to equilibrium Trp fluorescence data in Fig. 2). Could this dominate the population at low values of MFSDS? If so, such a state should have “patches of accessibility” such that, e.g., the accessibility of positions 100, 104, 155, and 260 are not significantly altered, whereas 211 and 240 should be more protected in the N∗ state. This explanation seems too contrived to be plausible. In addition, the spectroscopic transition observed in Fig. 2 are all completed by 0.1 MFSDS, but the decline in labeling kinetics in Fig. 4 continues until around 0.2–0.3 MFSDS.

Scenario II: different changes in protein dynamics at low MFSDS

We note that the mutants V211C and G240C contain Cys residues that are in TM4 and TM5, a particularly dynamic part of GlpG involved in the catalytic mechanism. Along with S181C (whose mintN-value cannot be determined accurately because of the very narrow native baseline), these two positions undergo the most rapid exchange of the seven mutants. However, it remains unclear why these dynamics should decline so much for V211C and G240C, i.e., why small amounts of SDS should preferentially stabilize V211C and G240C. We tried to investigate this computationally. As described in the Supporting materials and methods, we simulated the dynamics of WT GlpG structure in DDM-SDS micelles composed of 0, 10, and 100% SDS over a 500-ns period, measuring the fluctuation in position as well as the average surface accessibility of the seven wild-type residues M100, C104, L155, S181, V211, G240, and V260. Somewhat disappointingly, V211C and G240C did not respond to the increase in MFSDS, whereas the remaining five residues showed decreased accessibility and fluctuations in 10% SDS compared to 0% DDM (Fig. S4, A and B). Although the behavior of these latter five residues indicated a general stabilizing effect of 10% SDS, the ranking of V211C and G240C compared to the other five residues contravened our experimental results.

Scenario III: local stabilization by individual SDS molecules

As an alternative approach, we computed the duration of the time of binding of SDS molecules to each individual residue of GlpG in micelles composed of 90% DDM and 10% SDS. The top 10 residues that showed the longest average interaction durations from each simulation were combined (Table S1) and mapped on to the GlpG structure (Fig. S5). Interestingly, the 10 most targeted residues (including V211 itself) cluster around V211, whereas the remaining nine are found in a broad belt around the middle of GlpG. Thus, it could be argued that preferential binding of SDS around residue 211 makes it more difficult for DTNB to access this residue as well as possibly stabilizing N in this area as a local ligand, thus leading to a lower reactivity level for Cys211. SDS does not in a similar manner cluster preferentially around residue 240 (although residues 224–229 targeted by SDS are close in sequence to residue 240). Therefore, though more appealing than scenarios I and II, scenario III still has challenges based on the simulation data to explain the apparent stabilizing effect of SDS around Cys240.

Scenario IV: changes in micelle size and shape

In a final attempt to obtain a feasible explanation for the apparent stabilization of certain parts of GlpG at low MFSDS, we decided to investigate possible changes in the size and/or shape of the micelles. For this, we turned to SAXS measurements on mixed (but protein-free) micelles under the same set of conditions used to study GlpG. The resulting scattering spectra (Fig. S6 A) were fitted to a model (Fig. 7 A) in which the size and eccentricity of an ellipsoidal micelle were allowed to vary as a function of MFSDS, and the results from these fits are plotted in Figs. 6, B and C and S6, B and C. More details are provided in the Supporting materials and methods. This model fitted the data well over the whole SDS range (Fig. S6 A) and provided information on structural changes upon addition of SDS to DDM. Although somewhat noisy, the data show clear and nonmonotonic trends in fitted micelle sizes (Fig. 7 B) and eccentricities (Fig. 7 C) as MFSDS changes from 0.0 to 1.0. The micelles at both low and high MFSDS are relatively small (with aggregation numbers around 80) and only moderately eccentric (with eccentricity values around 2–3). At intermediate values of MFSDS, the micelles become large (nearly doubling in size) and highly eccentric. The eccentricity, ε, is the ratio of the length/width of the micelles (Fig. 7 A) and showed an elongation of the micelles as more and more SDS was added up to a maximal size that was reached around MFSDS of 0.425.

Figure 7.

SAXS analysis of mixed micelles of SDS and DDM. (A) Model used to fit to SAXS scattering curves. This allows us to calculate changes in the aggregation number (B) and the eccentricity (C) of mixed micelles as a function of MFSDS. Changes in the micelles are seen with just a little SDS added. All data were fitted by a model of ellipsoids of revolution. Error bars represent errors from model fittings.

Although these SAXS experiments were performed in the absence of protein, they provide a possible (though rather unspecific) explanation for our Cys-labeling kinetics. At low MFSDS, smaller micelles with higher curvature may lead to a more exposed state, whereas a more compact state may be stabilized by larger micelles of lower curvature (Nagg > 120), which are formed at higher MFSDS. This will be balanced off by the gradual accumulation of more and more SDS molecules, which will eventually lead to expansion of the protein as the electrostatic repulsion between SDS’s charged headgroups forces the different helices apart, even though the micelles formed around 0 and 1 MFSDS have the same size and shape. Such a situation should lead to an optimal MFSDS, away from which protein stability will decline. The details of which parts of the protein are particularly favored at this low-MFSDS optimum will likely depend on the protein and its position in the micelle and could therefore, in principle, lead to different behavior for different residues. As a note of caution, bear in mind that this scenario does not provide predictions for the exchange of specific residues. It is also hampered by an incomplete overlap between the range of declining exchange (from 0 to 0.2–0.3 MFSDS) and the range of increasing micelle size (from 0 to 0.4–0.5 MFSDS). Another complicating factor is that with increasing MFSDS comes an increasingly negative micelle electrostatic potential that will reduce surface pH (because of the increased attraction of protons) and alter ionization properties. Thus, 100% SDS micelles can shift pKa-values of ionizable side chains by 2.3 pH units (35,36), and this effect will scale with MFSDS, potentially affecting intramolecular protein interactions already at low MFSDS. However, simulating these features at the level of individual side chains is an unrealistic ambition at present.

Discussion

The limitations of Cys labeling to investigate the dynamics of membrane protein interactions

Ever since the first deployment of mixed micelles in efforts to systematically determine the stabilities of membrane proteins (10), MFSDS has been considered conceptually equivalent to the concentration of chaotropic agents that are used to unfold soluble proteins. This implies that the higher the MFSDS, the greater the stabilization of expanded (rather than compact) states. Nevertheless, the subtle changes in Trp fluorescence at low MFSDS, along with declines in labeling rates for V211C and G240C at lowMFSDS, indicate that there may be some changes in the micellar environment of the proteins under these conditions that go in the opposite direction.

Although unfolding in SDS is a convenient way of accessing D(s) of a membrane protein, it does not represent a physiologically relevant situation, and the strongest argument for its use has rested on the assumption of being able to extrapolate to native-like conditions, as suggested by studies on the unfolding of membrane proteins such as DAGK (10), bacteriorhodopsin (13), DsbB (17), and GlpG (18). To test this assumption, we initiated these Cys-labeling studies. Our work was further prompted by observations of subtle changes in Trp fluorescence at low MFSDS and possible off-pathway folding intermediates observed by stopped-flow kinetics. We hoped that Cys-labeling kinetics would allow us to gauge the dynamics of membrane protein folding and unfolding under native-like conditions. Unfortunately, this turned out not to be feasible to accomplish because of the relatively rapid Cys labeling of the N state (despite the selection of residues that are expected to be securely buried in the N state), which overrides any contributions from labeling of the very sparsely populated D state. In fact, our data can be rationalized by a simple two-state unfolding scheme with exchange from both D and N state, which confirms the simple N ↔ D transition in the range from 0.1 MFSDS below the start of the major unfolding transition and up to the end of the major transition, at which N and D coexist to significant extents. This rapid exchange also precludes extension of our work to more in vivo conditions in which the D state is likely to be present to an even smaller extent.

The main novelty of our work, to our knowledge, is that it provides information about labeling rates for the N and D states. Labeling rates for the D state are overall comparable, independent of the residues’ position in the protein, and align to a model of D that is essentially equally accessible throughout the sequence. However, the labeling of the N state raises more questions than it answers because it shows that some positions, but not others, are actually rendered less accessible to labeling by small increases in MFSDS. We have proposed four different scenarios to explain this, none of which are particularly convincing on their own, although they may, in combination, contribute to an understanding.

A potential quasinative state observed at very low MFSDS through subtle changes in Trp emission spectra would need to have very contrived properties to explain the differential labeling of Cys residues. MD simulations to gauge residue accessibility and dynamics at 0, 0.1, and 1 MFSDS showed an overall decrease in accessibility between 0 and 0.1 MFSDS. However, the trends for individual positions were exactly the opposite of what we observed experimentally. Simply identifying which residues engage in the longest periods of contact with SDS in micelles containing 10% SDS seems to identify a more promising line of inquiry, as it singled out residue 211 as a hot spot for binding, although it is less straightforward to rationalize the sensitivity of residue 240. Experimental follow-ups to these simulations such as alternative global analyses of protein stability (e.g., thermal denaturation at low MFSDS) are not straightforward; although monomeric SDS may act as a stabilizing ligand by binding to specific sites on N in some positions, these effects may be counterbalanced by denaturing effects of binding elsewhere (e.g., wedging between different helices to drive them apart). Furthermore, the nature of SDS binding may change with temperature and thus make it difficult to extrapolate to ambient conditions (37). We note that it is generally very challenging to simulate the effects of micelles on protein structure. In a previous study on the unfolding of the globular protein ACBP in SDS, we were unable to unfold the protein in the presence of micelles but had to coincubate protein with SDS monomers to allow SDS clustering and micellization to drive unfolding (38). We suspect that a more satisfying explanation for residue-specific variations will have to await more robust simulation methods. Finally, SAXS data indicate that micelles undergo a systematic but nonmonotonic change in structure as MFSDS varies. This observation provides the closest experimental link to our negative mintN-values and remains an interesting proposal. However, the robustness of our fitting is challenged by the different micelle forms of pure SDS and DDM, and the region of change does not coincide completely with the region of negative kintN-values.

Steric trapping provides independent support for the nonmonotonic stability of GlpG in mixed micelles

We will now turn to a general discussion of the lack of monotonic stability change of GlpG in mixed micelles. Ours is not the first study to note the possible existence of nonmonotonic stability of GlpG in mixed detergent micelles. A few years ago, steric trapping was applied to the measurement of GlpG’s stability in mixed SDS-DDM micelles (39). The authors of that study found that GlpG’s stability was nonmonotonic, with a rollover in stability occurring around 0.2 MFSDS, which interestingly enough overlaps with the rollover in stability that we observed to occur using a combination of stopped-flow kinetics, equilibrium tryptophan fluorescence, and cysteine labeling kinetics. At that time, in the absence of information about how the structures of the micelles were changing as a function of MFSDS, the origin of the nonmonotonicity of the stability of GlpG was unclear and therefore not discussed. The authors did note, however, that changes in micelle size and shape as a function of MFSDS could possibly be invoked to explain the differences in the distributions of interhelical distances in the sterically trapped (DDM-solubilized) and high MFSDS unfolded states (39). Our own SAXS data clearly show that the mixed SDS-DDM micelles used to solubilize GlpG in this study are smaller and more spherical at high and low MFSDS compared to the larger and more cylindrical micelles seen at intermediate values of MFSDS. The larger micelles may provide a more favorable embedding of membrane proteins up to a stage at which the destabilizing effects of SDS overtake the favorable micelle size changes.

Which aspects of micelle formation might drive this nonmonotonic behavior? The molecular thermodynamic theory of mixed micellization has been extensively studied, independent of membrane protein biophysics. For mixed micelles for which one or more of the detergents has a charged headgroup, it has been shown that the electrostatic contribution to the micelle free energy is quadratic in the mole fraction of the charged detergent. As a result, the stabilities of spherical and cylindrical micelles can cross multiple times as the mole fraction of charged detergent is varied (40). In short, the theory predicts what we see here: micelles that initially grow and elongate as the MFSDS is initially increased and then become smaller and more spherical as the MFSDS is further increased.

Coupling to a micelle shape transition explains how SDS indirectly influences the stability of the folded state of membrane proteins

The introduction of mixed micelles as a way of solubilizing and reversibly folding and unfolding membrane proteins has contributed tremendously to our understanding of membrane protein biophysics. Nevertheless, it has never been made clear how or why MFSDS is or is not analogous to the concentration of chaotropic agents in the unfolding soluble protein folding. The prevailing assumption in the literature is that the charged headgroup of SDS unfolds proteins by directly interacting preferentially with the unfolded state of the protein. Our SAXS data suggest another previously unrecognized and indirect role of SDS in unfolding membrane proteins: SDS influences the size and shape of micelles, which, in turn, influence the relative stability of the folded and unfolded states of membrane proteins. A complete theory of the stability of membrane proteins that are solubilized in a mixed detergent micelles must consider the composite nature of these objects, and the folding and unfolding transition in mixed micelles might well be understood as a coupled shape transition of a protein-detergent complex that is driven in part by the indirect influence of the charged headgroups of ionic detergents on the intrinsic size and shape preferences of the micelle. Thus, a reduction in curvature due to the introduction of SDS at low MFSDS may lead to more favorable embedding of membrane proteins in the micelle and thus a degree of increased stabilization. Coupled to the possible interactions between monomeric SDS molecules and individual parts of the protein, this leads to a more complex and variegated role for anionic surfactants in the interaction with membrane proteins than a simple preference for a more exposed and denatured state.

The recognition of a possible role of intrinsic micelle size and shape in tuning the relative free energy of the folded and unfolded state of membrane proteins has significant consequences. Further experimental tests of the coupling of micelle and protein shape transitions, as well as the development of quantitative theories for understanding this coupling, could result in the establishment of a truly general framework for understanding membrane protein-micelle complex stability.

An opportunity to efficiently engineer micelle properties for membrane protein solubilization

Experiments on membrane proteins are inherently costly because of the difficulties associated with obtaining pure, soluble, and folded protein. In the absence of a framework for understanding the principles that control membrane protein stability in micelles, many have adopted a try-and-see approach to optimizing membrane protein purification protocols. With a relatively complete understanding of how the intrinsic properties of micelles influence membrane protein stability in hand, however, one can now imagine performing experiments to rationally optimize mixed detergent micelles for membrane protein solubilization. In particular, we suggest optimizing the size and shape of micelles using the molecular thermodynamic theory of the mixed micellization and following up these calculations with experimental tests using, e.g., SAXS before proceeding on to tests involving expensive-to-obtain membrane protein molecules.

Author contributions

D.E.O.: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing; J.N.P.: investigation and writing—original draft; A.K.S.: investigation and writing—original draft; A.C.: investigation; M.J.: investigation; E.H.P.: investigation; J.S.P.: formal analysis, methodology, and writing—original draft; S.U.: investigation and writing—review and editing; N.P.S.: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, and writing—original draft.

Acknowledgments

We are highly indebted to Prof. Sinisa Urban for long-term steadfast help, advice, and general support for our work on GlpG.

D.E.O. and N.P.S. were supported by the Independent Danish Research Foundation, Natural Sciences Grant 4090-00220 and the Carlsberg Foundation Grant CF14-0287. A.K.S. is supported by the Lundbeck Foundation (grant R287-2018-1836).

Editor: Samrat Mukhopadhyay.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2021.08.001.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Pellowe G.A., Booth P.J. Structural insight into co-translational membrane protein folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020;1862 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2019.07.007. 183019 Published online July 11, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cymer F., von Heijne G., White S.H. Mechanisms of integral membrane protein insertion and folding. J. Mol. Biol. 2015;427:999–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2014.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hong H. Toward understanding driving forces in membrane protein folding. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;564:297–313. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neumann J., Klein N., Schneider D. Folding energetics and oligomerization of polytopic α-helical transmembrane proteins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;564:281–296. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianni S., Jemth P. Protein folding: vexing debates on a fundamental problem. Biophys. Chem. 2016;212:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferina J., Daggett V. Visualizing protein folding and unfolding. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:1540–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Otzen D. Membrane protein folding and stability. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2014;564:262–264. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haffke M., Duckely M., Shrestha B. Development of a biochemical and biophysical suite for integral membrane protein targets: a review. Protein Expr. Purif. 2020;167:105545. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2019.105545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christie S., Shi X., Smith A.W. Resolving membrane protein-protein interactions in live cells with pulsed interleaved excitation fluorescence cross-correlation spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020;53:792–799. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lau F.W., Bowie J.U. A method for assessing the stability of a membrane protein. Biochemistry. 1997;36:5884–5892. doi: 10.1021/bi963095j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal P., Mogensen J.E., Otzen D.E. Using micellar mole fractions to assess membrane protein stability in mixed micelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2005;1716:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2005.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Otzen D.E. Proteins in a brave new surfactant world. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2015;20:161–169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joh N.H., Min A., Bowie J.U. Modest stabilization by most hydrogen-bonded side-chain interactions in membrane proteins. Nature. 2008;453:1266–1270. doi: 10.1038/nature06977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlebach J.P., Cao Z., Park C. Revisiting the folding kinetics of bacteriorhodopsin. Protein Sci. 2012;21:97–106. doi: 10.1002/pro.766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tastan O., Dutta A., Klein-Seetharaman J. Retinal proteins as model systems for membrane protein folding. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1837:656–663. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2013.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otzen D.E. Mapping the folding pathway of the transmembrane protein DsbB by protein engineering. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2011;24:139–149. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzq079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otzen D.E. Folding of DsbB in mixed micelles: a kinetic analysis of the stability of a bacterial membrane protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:641–649. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paslawski W., Lillelund O.K., Otzen D.E. Cooperative folding of a polytopic α-helical membrane protein involves a compact N-terminal nucleus and nonnative loops. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:7978–7983. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1424751112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fersht A.R., Matouschek A., Serrano L. The folding of an enzyme. I. Theory of protein engineering analysis of stability and pathway of protein folding. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;224:771–782. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90561-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schafer N.P., Truong H.H., Wolynes P.G. Topological constraints and modular structure in the folding and functional motions of GlpG, an intramembrane protease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:2098–2103. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524027113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramachandran S., Rami B.R., Udgaonkar J.B. Measurements of cysteine reactivity during protein unfolding suggest the presence of competing pathways. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;297:733–745. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isom D.G., Marguet P.R., Hellinga H.W. A miniaturized technique for assessing protein thermodynamics and function using fast determination of quantitative cysteine reactivity. Proteins. 2011;79:1034–1047. doi: 10.1002/prot.22932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Padgette S.R., Huynh Q.K., Kishore G.M. Identification of the reactive cysteines of Escherichia coli 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase and their nonessentiality for enzymatic catalysis. J. Biol. Chem. 1988;263:1798–1802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jha S.K., Marqusee S. Kinetic evidence for a two-stage mechanism of protein denaturation by guanidinium chloride. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:4856–4861. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1315453111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branigan E., Pliotas C., Naismith J.H. Quantification of free cysteines in membrane and soluble proteins using a fluorescent dye and thermal unfolding. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2090–2097. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meuller J., Rydström J. The membrane topology of proton-pumping Escherichia coli transhydrogenase determined by cysteine labeling. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:19072–19080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexandrov A.I., Mileni M., Stevens R.C. Microscale fluorescent thermal stability assay for membrane proteins. Structure. 2008;16:351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinothkumar K.R., Strisovsky K., Freeman M. The structural basis for catalysis and substrate specificity of a rhomboid protease. EMBO J. 2010;29:3797–3809. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Krainer G., Hartmann A., Otzen D.E. SDS-induced multi-stage unfolding of a small globular protein through different denatured states revealed by single-molecule fluorescence. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 2020;11:9141–9153. doi: 10.1039/d0sc02100h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellman G.L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1959;82:70–77. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(59)90090-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hvidt A., Nielsen S.O. Hydrogen exchange in proteins. Adv. Protein Chem. 1966;21:287–386. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60129-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hvidt A., Linderstrøm-Lang K. Exchange of hydrogen atoms in insulin with deuterium atoms in aqueous solutions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1954;14:574–575. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(54)90241-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fersht A.R. Freeman & Co.; New York: 1999. Structure and Mechanism in Protein Science. A Guide to Enzyme Catalysis and Protein Folding. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timasheff S.N. Control of protein stability and reactions by weakly interacting cosolvents: the simplicity of the complicated. Adv. Protein Chem. 1998;51:355–432. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(08)60656-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fromherz P. Lipid coumarin dye as a probe of interfacial electrical potential in biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1989;171:376–387. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(89)71021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Otzen D.E. Protein unfolding in detergents: effect of micelle structure, ionic strength, pH, and temperature. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2219–2230. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)73982-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sehgal P., Otzen D.E. Thermodynamics of unfolding of an integral membrane protein in mixed micelles. Protein Sci. 2006;15:890–899. doi: 10.1110/ps.052031306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poghosyan A.H., Schafer N.P., Otzen D.E. Molecular dynamics study of ACBP denaturation in alkyl sulfates demonstrates possible pathways of unfolding through fused surfactant clusters. Protein Eng. Des. Sel. 2019;32:175–190. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzz037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo R., Gaffney K., Hong H. Steric trapping reveals a cooperativity network in the intramembrane protease GlpG. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016;12:353–360. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shiloach A., Blankschtein D. Predicting micellar solution properties of binary surfactant mixtures. Langmuir. 1998;14:1618–1636. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.