Abstract

The bacterial flagellar motor, a remarkable rotary machine, can rapidly switch between counterclockwise (CCW) and clockwise (CW) rotational directions to control the migration behavior of the bacterial cell. The flagellar motor consists of a bi-directional spinning rotor surrounded by torque-generating stator units. Recent high-resolution in vitro and in situ structural studies have revealed stunning details of the individual components of the flagellar motor and their interactions in both the CCW and CW senses. In this review, we discuss these structures and their implications for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying flagellar rotation and switching.

Keywords: Rotary machine, bacterial motility, rotor-stator interactions, torque generation, rotational switching

Bacterial motility and chemotaxis

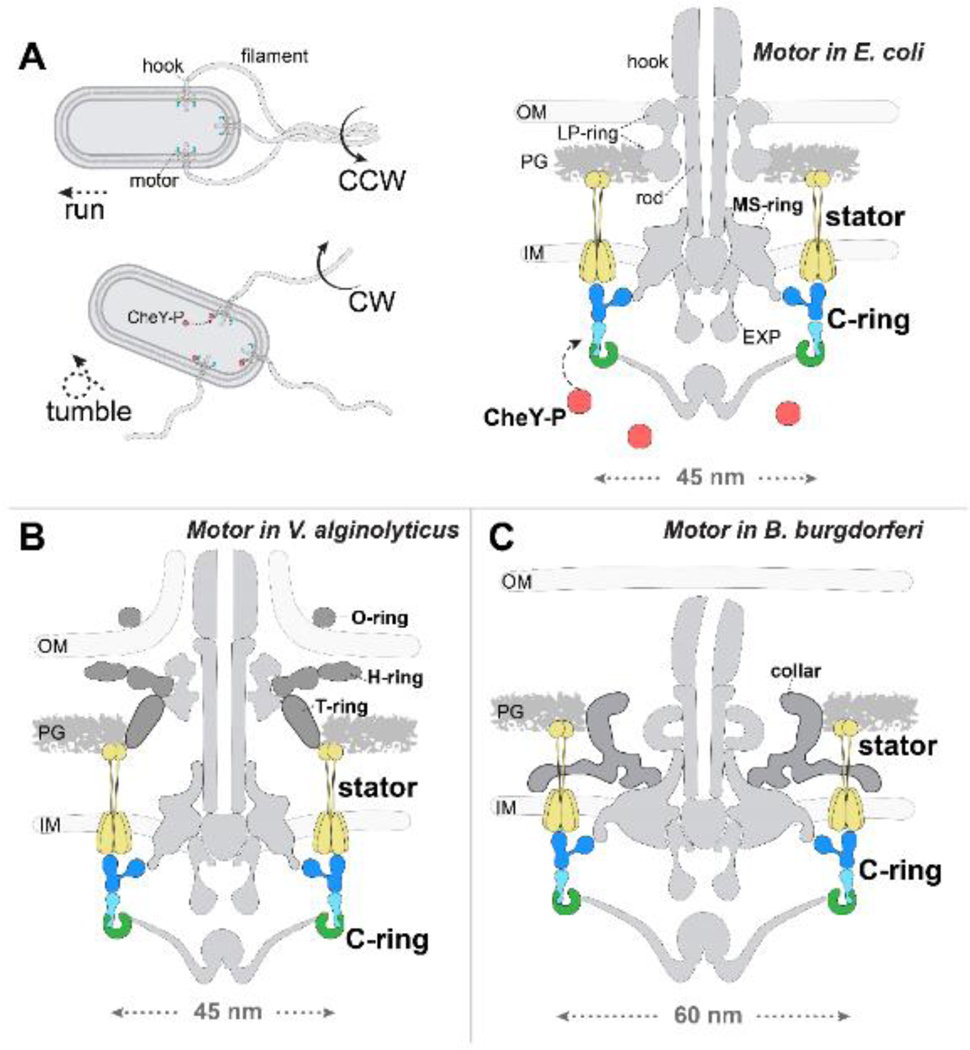

Bacterial motility is often required for bacterial survival and pathogenicity [1, 2]. Numerous bacterial species utilize the flagellum to swim in liquid medium or swarm on solid surfaces [3–5]. Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica (hereafter referred to as Salmonella), the most commonly studied flagellar organisms, have a two-step swimming pattern: when the flagellum rotates counterclockwise (CCW as viewed from the flagellar filament to the motor), the cell “runs” to move forward, and when it rotates clockwise (CW), the cell “tumbles” and changes direction (Figure 1A) [3–5]. A sophisticated chemotaxis signaling system allows bacteria to sense temporal changes in the environment and transmits this information via the chemotactic signaling protein phospho-CheY (CheY-P) to regulate the direction of flagellar rotation [6]. In the default state (without CheY-P), the flagellum rotates CCW, while the flagellum switches to CW rotation in the presence of CheY-P (Figure 1A). Collectively, the chemotaxis-mediated rotational switching of the flagellum enables bacteria to move toward favorable and away from undesirable environments.

Figure 1. Bacterial flagellar motility is controlled by the direction of flagellar rotation.

(A) A flagellum is composed of the flagellar motor, hook, and filament. In E. coli and Salmonella, bacterial flagella form a bundle when rotating in the CCW direction and drive the bacteria to “run” forward (top left); the bundle is disrupted when some flagella rotate in the CW direction due to the chemosensory protein CheY-P binding on the motor, enabling bacteria to “tumble” and change direction (bottom left). The E. coli flagellar motor consists mainly of the stator, C-ring, export apparatus (EXP), MS-ring, LP-ring, and rod (right). Motor rotation is powered by the ion flow through the stator channel. IM: inner membrane. PG: peptidoglycan. OM: outer membrane. Flagellar motors in Vibrio and B. burgdorferi, compared to E. coli, have additional periplasmic components. The Vibrio motor has H- and T-rings (B), while the B. burgdorferi motor has a “collar” component (C).

The mechanisms underlying flagellar rotation and directional switching have been the subject of extensive biochemical, structural, and functional studies for several decades [3–5, 7–9]. Many fundamental questions remain elusive, such as: How does the flagellum couple the ion gradient with torque generation? And how does the flagellum control rotational switching? Here, we discuss some of the most recent breakthroughs in structural characterization of the flagellum and their impact on our understanding of this fascinating molecular machine.

The bacterial flagellar motor

The bacterial flagellum consists of three parts (Figure 1A): the motor, a rotary machine that provides the power for rotation; the filament, a helical propeller; and the hook, a joint connecting the filament to the motor [10, 11]. The flagellar motor possesses a rotor and multiple stator units. The stator unit is a torque generator powered by ion flow across the inner membrane (Figure 1A) [12]. The rotor consists of the MS-ring and C-ring, and the LP-rings and rod function as the bushing and central drive shaft, respectively (Figure 1A). The MS-ring, a transmembrane complex composed of the protein FliF [13], is the base for the assembly of the export apparatus, the C-ring, and the rod [13–15]. The C-ring attaches to the cytoplasmic face of the MS-ring [16–18] and is essential for rotation and for directional switching of the motor.

Although the core components of the flagellar motors are highly conserved, many bacteria have evolved additional species-specific features to enhance flagellar functions [8, 19]. The marine bacterium Vibrio alginolyticus has a single sheathed polar flagellum that is capable to rotate up to 1,700 r.p.s [20]. The V. alginolyticus motor has two Vibrio-specific periplasmic components, the H- and T-rings, and one additional O-ring around the outer membrane sheath (Figure 1B) [21]. These Vibrio-specific features are important for the recruitment of the stator units and the formation of the outer membrane sheath, and likely contribute to high-speed flagellar rotation. The Lyme disease-causing spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi has 7–12 flagella at each cell pole that uniquely remain in the periplasmic space and perform both structural and motility roles [8, 22]. The flagellar motor of B. burgdorferi is noticeably larger than that of E. coli or Vibrio (Figure 1) and possesses a spirochete-specific “collar” in the periplasmic space (Figure 1C). The collar is directly involved in the interaction with the stator units and thus crucial for both stator assembly and bacterial motility [23, 24]. Importantly, the collective information derived from different flagellar motors provides a better understanding of flagellar assembly, conservation, and diversity.

The structure and assembly of the C-ring

The C-ring, also called the switch complex, forms a cylindrical wall structure in the cytoplasm consisting of “Y”-shaped subunits (Figure 2A, D). Each C-ring subunit contains the FliG, FliM, and FliN proteins [25–28]. FliG interacts with the stator complex and is thus directly involved in motor rotation [29]. The C-terminal domain of FliG (FliGC) consists of two subdomains, FliGCC and FliGCN, connected by an MFXF motif. FliGCC contains a helix essential for torque generation, with two highly conserved residues, Arg281 and Asp289, directly interacting with charged residues in the cytoplasmic domain of the stator [30]. The MFXF motif is highly flexible and, upon rearrangement, induces a 180° rotation of FliGCC relative to FliGCN to reorient the charged residues [31, 32], likely essential for directional switching. FliM connects FliG with FliN and sits at the center of the C-ring wall. FliN and FliM were reported to form a FliM1/FliN4 or FliM1/FliN3 complex. In the first model, four FliN monomers form a ring at the base of the C-ring [28, 33, 34]. In the second model, three FliN copies together with one FliM C-terminal domain (FliMC) form a FliMC/FliN3 complex [27]. This FliMC/FliN3 complex interacts with the neighboring subunits to assemble a spiral ring at the base of the C-ring (Figure 2G). The C-ring structures revealed by cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) analyses agree well with 1:1:3 stoichiometry. However, a higher resolution in situ structure of the C-ring will be required to verify the model.

Figure 2. Architecture of the C-ring and its conformational change during directional switching.

(A-F) The “Y” shaped C-ring subunits assemble into a ring with different diameters in different bacteria by changing the number of subunits. The C-ring in the V. alginolyticus motor has 34-fold symmetry and is ~50 nm in diameter (A-C)[37]. By contrast, the C-ring in the B. burgdorferi motor has 46-fold symmetry and is ~60 nm in diameter (D-F)[38]. (C) and (F) are the cartoon models corresponding to (B) and (E), respectively, showing the symmetry and diameter of the FliG ring. (G) Surface view of the CCW and CW C-rings in B. burgdorferi showing the C-ring subunits connected by the spiral ring at the base. CheY-P binding on the C-ring induces a diameter change of the FliG ring (left) and a tilt of the subunit within the C-ring wall plane (right).

The structure and composition of the C-ring subunits are relatively conserved, whereas the diameter and symmetry of the C-ring vary across bacterial species. Early cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) studies suggested that the C-ring in Salmonella has a rotational symmetry from 32- to 36-fold and a diameter of approximately 50 nm [35, 36]. Recent cryo-ET studies provided evidence that the C-ring of the V. alginolyticus motor has 34-fold symmetry and is ~50 nm in diameter (Figure 2A–C) [37], while the C-ring in the B. burgdorferi motor has a higher symmetry (46-fold) and a larger diameter (~60 nm) (Figure 2D–F) [38]. Given that a larger C-ring can potentially interact with more stator units, enabling higher torque generation [39], the in situ structures suggest that bacteria have evolved a conserved mechanism to assemble the C-ring with different diameters to better suit specific cellular functions and needs.

Conformational changes of the C-ring during rotational switching

The unique architecture of the C-ring provides the basis for understanding the switch between CCW and CW. Cryo-ET study [37] of two V. alginolyticus strains in which the motor is locked in the CW (FliG G215A) sense or biased to the CCW (FliG G214S) sense provided structural evidence that the C-ring undergoes a large remodeling during switching. A related cryo-ET study from B. burgdorferi [38] presented evidence that CheY3-P binding facilitates a large conformational change of the C-ring. Importantly, the C-ring undergoes similar conformational changes in both V. alginolyticus and B. burgdorferi, while the spiral structure at the base of the C-ring remains unchanged during directional switching (Figure 2G) [37, 38]. It is worth noting that the C-rings observed in both studies maintain the same species-specific symmetry during directional switching [37, 38], consistent with a symmetrical process of the torque generation in both the CCW and CW rotational directions [40], but different from the compositional change of the C-ring previously reported in E. coli [41, 42]. Pseudo-atomic models of the C-ring based on in situ density maps and crystal structures of the three components indicate that the large-scale C-ring dynamics can be attributed to a tilt of FliM proteins within the C-ring wall plane (Figure 2G right) [37, 38] and to a diameter change of the FliG ring relative to the motor axis (Figure 2G left) [37, 38]. These conformational changes are consistent with previous studies (for review [9]): the binding of CheY-P with FliM/FliN induces the tilt of FliM and alters interactions between adjacent FliM proteins, further inducing conformational changes of the FliG proteins, and ultimately altering interactions between the C-ring and stator and triggering a rotational switch [43, 44].

The stator structure and assembly

The stator is the torque generator that converts energy from the ion gradient across the inner membrane into torque [12]. Each stator unit is a transmembrane complex composed of proteins MotA and MotB [38, 45, 46]. MotB has a C-terminal peptidoglycan-binding domain and a single transmembrane helix (TMH)[47] that contains the highly conserved residue Asp32 directly involved in proton transport [48]. MotA is composed of four TMHs and a large cytoplasmic loop containing two highly conserved charged residues, Arg90 and Glu98, which are critical for stator function [49]. Each stator unit associates with and dissociates from the motor in a dynamic fashion in response to ion concentration [50, 51] and external load on the flagellum [52, 53]. At maximum power, about a dozen stator units associate with the motor, forming a ring-like structure surrounding the rotor, as revealed by freeze-fracture electron microscopy (Figure 3A) [54]. Similar stator rings were recently observed in V. alginolyticus and B. burgdorferi by cryo-ET [23, 37, 38], although the stator ring in V. alginolyticus and B. burgdorferi motors is composed of 13 or 16 units, with diameters around 50 and 60 nm, respectively (Figure 3B, C). It appears that the diameter of the stator ring and the number of stator units vary among species in a way that is proportional to the diameter of the corresponding C-ring (Figure 2A–D).

Figure 3. Architecture of the stator and the “rotational” model for torque generation.

Multiple stator units assemble into a ring structure with different diameters in different bacteria, as revealed by a freeze-fracture electron microscopy study in E. coli (A)[54] and cryo-ET studies of the flagellar motors of V. alginolyticus (B)[37] and B. burgdorferi (C)[38]. (D) Schematic model of MotA and MotB proteins. (E) Two MotB and five MotA proteins form a stator unit. A stator model shown with the crystal structure of Salmonella MotB periplasmic domain (5Y40[58]) on top of the cryo-EM structure of the Campylobacter jejuni stator cytoplasmic domain (6KYP[46]). (F) The bottom view of the MotA pentamer in the C. jejuni stator with the conserved charged residues Arg90 and Glu98 (using E. coli numbering) shown in blue and red, respectively. (G) A cartoon model showing the stator “rotational” model for torque generation (view from periplasm to cytoplasm). Two MotB subunits are surrounded by a MotA pentamer. Ion flow leads to rotation of the MotA pentamer through alternating formation of MotB-ion-MotA interactions between two MotB subunits and the MotA subunits that rotate around them. (E-G) are adapted from [45].

Recent cryo-EM structures revealed the stator complex is a pentamer of MotA and a dimer of MotB, a surprising discovery as MotA was previously believed to form a tetramer (Figure 3E) [45, 46]. The charged residues of MotA involved in motor rotation form a ring at the base of the pentamer (Figure 3F) [45, 46]. Comparison of the unplugged and protonation-mimicking (the conserved Asp replaced with Asn) versions of MotAB structures in Campylobcater jejuni provided evidence for a stator “rotational” model (Figure 3G) [45, 46], whereby the proton, upon binding to the conserved aspartate residue of MotB1, is shuttled through the channel, triggering CW rotation (view from periplasm to cytoplasm) of the MotA pentamer by ~36°. One rotation step of the MotA pentamer brings MotB2 into the same position as the starting position of MotB1 relative to MotA. Proton transmission through the MotB2 channel then drives the MotA pentamer to rotate another ~36°. Therefore, ten proton binding events are required for a full 360° rotation of the MotA pentamer. In this model, the aspartate residues of two MotB copies transport protons alternately, and each proton binding event is identical at the molecular level. Altogether, the rotation of the MotA pentamer is unidirectional and provides a “power stroke” to rotate the rotor. It is worth noting that the stator unit was previously presumed not to rotate and that torque generation was expected to be powered by a large rearrangement of the MotA cytoplasmic domain [11, 55, 56].

Rotor-stator interactions are critical for torque generation

In the absence of the rotor, the stator units are in an inactive state with the stator channel plugged (Figure 4A, B, Key Figure). When the stator unit contacts the rotor, the interaction between MotA and FliG triggers rearrangement of the C-terminal domain of MotB (MotBC) such that the PG-binding domain of MotB extends to the PG layer, enabling activation of its ion channel and generation of torque (Figure 4A, D) [57, 58]. The cryo-EM structure of the stator complex reveals that the five MotA chains in one pentamer fall into two main configurations, differing in the degree of flexing in the cytoplasmic regions relative to membrane-embedded regions [45]. Therefore, the MotA-FliG interactions likely induce rearrangement of the MotA TMHs, leading to interactions between MotA and MotB, and between MotBC and the PG layer. The stator-rotor interaction also alters the conformation of the C-ring. Cryo-ET analyses of Vibrio Fischeri and C. jejuni motors [39] showed that the C-ring is more flexible in the absence of the stator units. A similar analysis of B. burgdorferi motors [23] indicates that rotor-stator interactions induce a tilt of the C-ring wall, along with a slight diameter shrinkage of the C-ring (Figure 4A–F). High resolution structural information is clearly needed to better understand the critical rotor-stator interaction and the mechanisms for torque generation.

Figure 4 (Key Figure). Rotor-stator interactions for torque generation and directional switching.

Stator units float along the inner membrane (IM) when they are not associated with a motor (A-C). The interaction between MotA and FliG triggers stator association (D). MotB extends its PG-binding domain and attaches to the PG layer (D). The C-ring slightly tilts into the motor axis (E) and shrinks in diameter (F) to interact with the inner side of the stator ring. When ions flow through the channel, the stator units spin in the CW direction and drive the C-ring to rotate CCW (F). CheY-P binding on the C-ring alters the interactions between MotA and FliG (G-H). The FliG ring expands ~7 nm in diameter to interact with the outer side of the stator ring (H, I). Because the charged residues Arg90 and Glu98 of MotA between the inner and outer surfaces of the MotA pentamer are mirrored, the charged residues Arg281 and Asp289 in FliG also rotate ~180° during directional switching (G), preserving interactions between MotA-Arg90-FliG-Asp289 and MotA-Glu98-FliG-Arg281, respectively (D and G). Adapted from [38].

A model of flagellar rotation and switching

The rotational sense of the flagellar motor is controlled by the interaction modes between the C-ring and stator ring, as revealed by the cryo-ET analysis in B. burgdorferi [38]. During directional switching, the C-ring undergoes large conformational changes [37, 38], while the stator ring appears to be stably attached to the spirochete-specific collar in both the CCW and CW states [38]. CheY-P binding to the C-ring induces a tilt of the FliM protein, resulting in rearrangement of FliG and altering the interaction sites between FliG and MotA. During CCW rotation, FliG interacts with the inner side (closer to the motor axis) of the MotA pentamer (Figure 4D, E), whereas in the CW state, the FliG ring expands ~7 nm in diameter and interacts with the outer side of the MotA pentamer (Figure 4G, H). This swapping of interaction sites between FliG and MotA enables the CW-spinning MotA pentamers to drive the C-ring in either the CCW or CW direction (Figure 4F, I). Due to the mirroring of the charged residues Arg90 and Glu98 of MotA between the inner and outer surfaces of the MotA pentamer (Figure 3F), the charged residues Arg281 and Asp289 in FliG also rotate ~180° during the directional switch, by rearrangement of the MFXF motif in FliGC [31, 32]. Therefore, the key interactions between MotA-Arg90-FliG-Asp289 and MotA-Glu98-FliG-Arg281 remain during the switching (Figure 4C, E). Overall, the stator ring, which is formed by multiple stator units powered by ion gradient, acts as a set of small cogwheels that keep spinning in a CW sense to drive the C-ring to rotate. The flagellar motor changes its rotational direction by swapping interaction sites between the C-ring and the stator ring to switch gears.

The flagellar switching model presented here is consistent with the evidence that all switching-related chemotaxis mutations are related with the C-ring proteins rather than the stator unit [9, 59]. Interestingly, the model also explains that the reversal of proton gradient through the stator units has the potential to reverse the stator spinning direction from CW to CCW and hence reverse the flagellar rotation direction, as previously observed in E. coli [60] and Streptococcus [61–63].

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

The bacterial flagellar motor is a remarkable nanomachine that is capable of high-speed rotation in both CCW and CW and rapid switching between them. Recent studies [37, 38, 45, 46] have revealed new structural information about this fascinating rotary machine, providing mechanistic insights into how the motor undergoes extensive remodeling to control rotational switching. Powered by the ion gradient, the MotA pentamer undergoes turning that drives the C-ring rotation in CCW through specific MotA and FliG interactions. Upon binding of the signaling protein CheY-P, the C-ring undergoes major remodeling to alter its interactions with the stator ring, thereby switching the rotational direction from CCW to CW. Given that both C-ring and stator complex are conserved, key aspects of the molecular mechanisms underlying flagellar rotation and directional switching discussed in this review are most likely shared across a wide spectrum of bacterial species.

Along with the proposed model of flagellar rotation and switching, many questions arise concerning rotor-stator interactions (see Outstanding Questions box), perhaps the most important being: Is the MotA pentamer actually spinning to generate torque? If so, ion flux through the stator channel must be tightly coupled with motor rotation, but such coupling remains to be quantitatively examined. Atomic structures of the MotA pentamer during torque generation will be required to determine the mechanisms. How exactly, then, does MotA interact with FliG during torque generation, and what role, if any, does FliF play in directional switching?

Outstanding Questions.

How does the interaction between FliG and MotA unplug the ion channel and trigger stator association?

Is the MotA pentamer of the stator unit spinning during torque generation?

How do the C-ring subunits transfer conformational changes cooperatively?

What role, if any, does the MS-ring play in the directional switch?

The flagellar motors in some bacterial species, compared to E. coli and Salmonella, have additional periplasmic components for higher torque generation, like the H- and T-rings in Vibrio and collar in B. burgdorferi. What roles do these additional components have in stator assembly and retention? How do they help to increase torque generation?

The stator units associate with and dissociate from the motor in a dynamic fashion; the fraction of time that the stator unit interacts with the rotor defines the duty ratio of the motor. A theoretical model [64] has predicted that the duty ratio is very small, close to zero, when the motor operates at extremely low load, whereas the duty ratio becomes high enough for the motor to generate much larger torque at high load. This model was supported by recent studies [65–68], in which the dissociation rate of the stator unit from the motor is much faster at extremely low load than at high load. The proposed rotational model (Figure 4) derived from the cryo-EM and cryo-ET analyses suggests that the stator units are firmly associated with the rotor at all times during flagellar rotation, which agrees well with the observed high duty ratio of the motor at high load but cannot explain why the duty ratio becomes smaller at low load. Further analysis is required to understand how the stator units control association, dissociation, and interaction with the rotor at extremely low load. Moreover, what roles do the additional periplasmic components in some bacterial species, like the H- and T-rings in Vibrio and the collar in B. burgdorferi, play in stator assembly and retention? How do they help to increase torque generation?

In summary, flagellum-mediated motility is vital for many bacterial pathogens and their life cycle and plays important roles in bacterial-host interactions [69–71]. The flagellar motor is the key component that responds to chemotactic signals to redirect bacteria toward beneficial environments. Recent high-resolution in vitro and in situ structural analyses enable major advances toward understanding flagellar rotation and switching at the molecular level. Further expansion of structural and functional studies promises to complete the elucidation of the mechanism by which this complex nanomachine operates. A better structural and functional understanding of the bacterial flagellar motor holds important implications for comprehending bacterial motility and behavior and also enables discoveries of novel antibacterial targets to cure or prevent infectious diseases.

Highlights.

The bi-directional flagellar motor consists of a rotor ring surrounded by multiple stator units and is controlled by a chemotaxis system that enables bacteria to move to favorable environments.

The C-ring, also called the switch complex, can spin in both CCW and CW directions. It has a different diameter and symmetry in different bacteria but shares similar building blocks and conformational changes during directional switching.

The stator units form a ring structure surrounding the C-ring. The diameter and symmetry of the stator ring vary across bacterial species to accommodate different C-ring diameters.

The stator unit, powered by an ion gradient across the inner membrane, spins in the clockwise sense, driving C-ring rotation.

The C-ring alters its interaction sites with the stator ring to enable the directional switch of the flagellar motor.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Aronson and two anonymous reviewers for critical reading and suggestions. The work in the Liu laboratory was supported by grants GM107629 and R01AI087946 from National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Haiko J and Westerlund-Wikstrom B. (2013) The role of the bacterial flagellum in adhesion and virulence. Biology (Basel) 2 (4), 1242–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duan Q. et al. (2013) Flagella and bacterial pathogenicity. J Basic Microbiol 53 (1), 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berg HC (2003) The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 19–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chevance FF and Hughes KT (2008) Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol 6 (6), 455–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terashima H. et al. (2008) Flagellar motility in bacteria structure and function of flagellar motor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 270, 39–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parkinson JS et al. (2015) Signaling and sensory adaptation in Escherichia coli chemoreceptors: 2015 update. Trends Microbiol 23 (5), 257–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan S. (2020) The Architectural Dynamics of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor Switch. Biomolecules 10 (6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroll BL and Liu J. (2020) Structural Conservation and Adaptation of the Bacterial Flagella Motor. Biomolecules 10 (11). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minamino T. et al. (2019) Directional Switching Mechanism of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 17, 1075–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minamino T and Namba K. (2004) Self-assembly and type III protein export of the bacterial flagellum. Journal of molecular microbiology and biotechnology 7 (1–2), 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakamura S and Minamino T. (2019) Flagella-Driven Motility of Bacteria. Biomolecules 9 (7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blair DF and Berg HC (1988) Restoration of torque in defective flagellar motors. Science 242 (4886), 1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson S. et al. (2020) Symmetry mismatch in the MS-ring of the bacterial flagellar rotor explains the structural coordination of secretion and rotation. Nat Microbiol 5 (7), 966–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ueno T. et al. (1992) M ring, S ring and proximal rod of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium are composed of subunits of a single protein, FliF. Journal of Molecular Biology 227 (3), 672–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawamoto A. et al. (2020) Native structure of flagellar MS ring is formed by 34 subunits with 23-fold and 11-fold subsymmetries. bioRxiv, 2020.10.11.334888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lynch MJ et al. (2017) Co-Folding of a FliF-FliG Split Domain Forms the Basis of the MS:C Ring Interface within the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Structure 25 (2), 317–328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xue C. et al. (2018) Crystal structure of the FliF-FliG complex from Helicobacter pylori yields insight into the assembly of the motor MS-C ring in the bacterial flagellum. Journal of Biological Chemistry 293 (6), 2066–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Francis NR et al. (1992) Localization of the Salmonella typhimurium flagellar switch protein FliG to the cytoplasmic M-ring face of the basal body. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 89 (14), 6304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen S. et al. (2011) Structural diversity of bacterial flagellar motors. The EMBO Journal 30 (14), 2972–2981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magariyama Y. et al. (1994) Very fast flagellar rotation. Nature 371 (6500), 752–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu S. et al. (2017) Molecular architecture of the sheathed polar flagellum in <em>Vibrio alginolyticus</em>. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (41), 10966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Charon NW et al. (2012) The unique paradigm of spirochete motility and chemotaxis. Annu Rev Microbiol 66, 349–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang Y. et al. (2019) Structural insights into flagellar stator-rotor interactions. Elife 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu H. et al. (2020) BB0326 is responsible for the formation of periplasmic flagellar collar and assembly of the stator complex in Borrelia burgdorferi. Molecular Microbiology 113 (2), 418–429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown PN et al. (2007) Mutational Analysis of the Flagellar Protein FliG: Sites of Interaction with FliM and Implications for Organization of the Switch Complex. Journal of Bacteriology 189 (2), 305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paul K. et al. (2011) Architecture of the flagellar rotor. The EMBO Journal 30 (14), 2962–2971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDowell MA et al. (2016) Characterisation of Shigella Spa33 and Thermotoga FliM/N reveals a new model for C-ring assembly in T3SS. Molecular Microbiology 99 (4), 749–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown PN et al. (2005) Crystal Structure of the Flagellar Rotor Protein FliN from Thermotoga maritima. Journal of Bacteriology 187 (8), 2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kojima S and Blair DF (2004) The Bacterial Flagellar Motor: Structure and Function of a Complex Molecular Machine. In International Review of Cytology, pp. 93–134, Academic Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lloyd SA et al. (1999) Structure of the C-terminal domain of FliG, a component of the rotor in the bacterial flagellar motor. Nature 400, 472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lam KH et al. (2012) Multiple conformations of the FliG C-terminal domain provide insight into flagellar motor switching. Structure 20 (2), 315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miyanoiri Y. et al. (2017) Structural and Functional Analysis of the C-Terminal Region of FliG, an Essential Motor Component of Vibrio Na(+)-Driven Flagella. Structure 25 (10), 1540–1548 e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarkar MK et al. (2010) Chemotaxis signaling protein CheY binds to the rotor protein FliN to control the direction of flagellar rotation in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107 (20), 9370–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarkar MK et al. (2010) Subunit organization and reversal-associated movements in the flagellar switch of Escherichia coli. Journal of Biological Chemistry 285 (1), 675–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thomas DR et al. (2006) The Three-Dimensional Structure of the Flagellar Rotor from a Clockwise-Locked Mutant of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium. Journal of Bacteriology 188 (20), 7039–7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thomas DR et al. (1999) Rotational symmetry of the C ring and a mechanism for the flagellar rotary motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 96 (18), 10134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carroll BL et al. (2020) The flagellar motor of Vibrio alginolyticus undergoes major structural remodeling during rotational switching. Elife 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang Y. et al. (2020) Molecular mechanism for rotational switching of the bacterial flagellar motor. Nat Struct Mol Biol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Beeby M. et al. (2016) Diverse high-torque bacterial flagellar motors assemble wider stator rings using a conserved protein scaffold. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113 (13), E1917–E1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakamura S. et al. (2010) Evidence for symmetry in the elementary process of bidirectional torque generation by the bacterial flagellar motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107 (41), 17616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lele PP et al. (2012) Mechanism for adaptive remodeling of the bacterial flagellar switch. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109 (49), 20018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Delalez NJ et al. (2014) Stoichiometry and Turnover of the Bacterial Flagellar Switch Protein FliN. mBio 5 (4), e01216–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paul K. et al. (2011) A molecular mechanism of direction switching in the flagellar motor of <em>Escherichia coli</em>. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108 (41), 17171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dyer CM et al. (2009) A molecular mechanism of bacterial flagellar motor switching. J Mol Biol 388 (1), 71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deme JC et al. (2020) Structures of the stator complex that drives rotation of the bacterial flagellum. Nat Microbiol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Santiveri M. et al. (2020) Structure and Function of Stator Units of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Cell 183 (1), 244–257 e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kojima S. et al. (2009) Stator assembly and activation mechanism of the flagellar motor by the periplasmic region of MotB. Molecular microbiology 73 (4), 710–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou J. et al. (1998) Function of Protonatable Residues in the Flagellar Motor of Escherichia coli: a Critical Role for Asp 32 of MotB. Journal of Bacteriology 180 (10), 2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou J. et al. (1998) Electrostatic interactions between rotor and stator in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 95 (11), 6436–6441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Leake MC et al. (2006) Stoichiometry and turnover in single, functioning membrane protein complexes. Nature 443, 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fukuoka H. et al. (2009) Sodium‐dependent dynamic assembly of membrane complexes in sodium‐driven flagellar motors. Molecular Microbiology 71 (4), 825–835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lele PP et al. (2013) Dynamics of mechanosensing in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110 (29), 11839–11844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tipping MJ et al. (2013) Load-Dependent Assembly of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. mBio 4 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Khan S. et al. (1988) Effects of mot gene expression on the structure of the flagellar motor. Journal of Molecular Biology 202 (3), 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kojima S and Blair DF (2004) Solubilization and Purification of the MotA/MotB Complex of Escherichia coli. Biochemistry 43 (1), 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nishihara Y and Kitao A. (2015) Gate-controlled proton diffusion and protonation-induced ratchet motion in the stator of the bacterial flagellar motor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112 (25), 7737–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hosking ER et al. (2006) The Escherichia coli MotAB Proton Channel Unplugged. Journal of Molecular Biology 364 (5), 921–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kojima S. et al. (2018) The Helix Rearrangement in the Periplasmic Domain of the Flagellar Stator B Subunit Activates Peptidoglycan Binding and Ion Influx. Structure 26 (4), 590–598.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Afanzar O. et al. (2021) The switching mechanism of the bacterial rotary motor combines tight regulation with inherent flexibility. EMBO J, e104683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fung DC and Berg HC (1995) Powering the flagellar motor of Escherichia coli with an external voltage source. Nature 375 (6534), 809–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Manson MD et al. (1980) Energetics of flagellar rotation in bacteria. Journal of molecular biology 138 (3), 541–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Khan S. et al. (1990) Energy transduction in the bacterial flagellar motor. Effects of load and pH. Biophysical journal 57 (4), 779–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Berg HC et al. (1982) Dynamics and energetics of flagellar rotation in bacteria. Symp Soc Exp Biol 35, 1–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nirody JA et al. (2016) The Limiting Speed of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor. Biophysical Journal 111 (3), 557–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nord AL et al. (2017) Speed of the bacterial flagellar motor near zero load depends on the number of stator units. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (44), 11603–11608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nakamura S. et al. (2020) Direct observation of speed fluctuations of flagellar motor rotation at extremely low load close to zero. Molecular Microbiology 113 (4), 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sato K. et al. (2019) Evaluation of the Duty Ratio of the Bacterial Flagellar Motor by Dynamic Load Control. Biophysical Journal 116 (10), 1952–1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nord AL et al. (2017) Catch bond drives stator mechanosensitivity in the bacterial flagellar motor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 114 (49), 12952–12957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Josenhans C and Suerbaum S. (2002) The role of motility as a virulence factor in bacteria. International Journal of Medical Microbiology 291 (8), 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Haiko J and Westerlund-Wikström B (2013) The Role of the Bacterial Flagellum in Adhesion and Virulence. Biology 2 (4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chaban B. et al. (2015) The flagellum in bacterial pathogens: For motility and a whole lot more. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology 46, 91–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]