Abstract

The consumption of a processed foods diet (PD) enriched with refined carbohydrates, saturated fats, and lack of fiber has increased in recent decades and likely contributed to increased incidence of chronic disease and weight gain in humans. These diets have also been shown to negatively impact brain health and cognitive function in rodents, non-human primates, and humans, potentially through neuroimmune-related mechanisms. However, mechanisms by which PD impacts the aged brain are unknown. This gap in knowledge is critical, considering the aged brain has a heightened state of baseline inflammation, making it more susceptible to secondary challenges. Here, we showed that consumption of a PD, enriched with refined carbohydrate sources, for 28 days impaired hippocampal- and amygdalar-dependent memory function in aged (24 months), but not young (3 months) F344 × BN rats. These memory deficits were accompanied by increased expression of inflammatory genes, such as IL-1β, CD11b, MHC class II, CD86, NLRP3, and complement component 3, in the hippocampus and amygdala of aged rats. Importantly, we also showed that when the same PD is supplemented with the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid DHA, these memory deficits and inflammatory gene expression changes were ameliorated in aged rats, thus providing the first evidence that DHA supplementation can protect against memory deficits and inflammatory gene expression in aged rats fed a processed foods diet. Lastly, we showed that while PD consumption increased weight gain in both young and aged rats, this effect was exaggerated in aged rats. Aging was also associated with significant alterations in hypothalamic gene expression, with no impact by DHA on weight gain or hypothalamic gene expression. Together, our data provide novel insights regarding diet-brain interactions by showing that PD consumption impairs cognitive function likely through a neuroimmune mechanism and that dietary DHA can ameliorate this phenomenon.

1. Introduction

The consumption of diets containing high levels of refined carbohydrates impairs learning and memory and leads to significant weight gain in rodents, non-human primates, and humans (Gentreau et al., 2020; Gross et al., 2004; Kanoski and Davidson, 2010; Shively et al., 2019; Spadaro et al., 2015). The mechanisms through which these impairments occur are unclear, although recent evidence suggests neuroimmune signaling as a likely target (Gomes et al., 2020). Moreover, the impacts of refined carbohydrate intake on the aged brain and behavior are unknown. This gap in knowledge is critical, considering the aged brain has a heightened state of baseline inflammation, making it more susceptible to secondary challenges (Barrientos et al., 2015). Indeed, previous work from our lab demonstrated that aged, but not young, rats fed a short-term high fat diet (HFD) have impaired hippocampal- and amygdalar-dependent memory and increased proinflammatory cytokine expression in the hippocampus and amygdala (Spencer et al., 2017). These behavioral deficits were prevented with central infusion of an interleukin-1β receptor antagonist, suggesting a causal link between neuroinflammation and diet-induced cognitive impairment. However, the role of refined carbohydrate consumption has not been tested in this paradigm.

Aging is associated with a decrease in the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), in the brain (Butler et al., 2020; McNamara et al., 2008; Weiser et al., 2016). DHA has a myriad of functions in the brain, including neuronal signaling, altering membrane structure and function, and lipid mediator production (Layé, 2010). Importantly, DHA also plays a major role in the resolution of inflammation in the brain. Briefly, upon an inflammatory challenge, DHA is cleaved from the phospholipid membrane and metabolized into specialized pro-resolving mediators (SPMs) (Layé, 2010; Layé et al., 2018). These SPMs can be released from cells, mainly neurons and astrocytes, and bind to receptors located on microglia, the resident immune cells of the brain, and resolve their proinflammatory phenotype (De Smedt-Peyrusse et al., 2008; Layé et al., 2018; Rey et al., 2016). In this regard, DHA supplementation can prevent or attenuate a variety of inflammatory insults to the brain, including traumatic brain injury, stroke, and age-related cognitive decline (Butt et al., 2017; Labrousse et al., 2012; Layé, 2010). However, whether DHA protects against carbohydrate-induced insults on cognition and neuroinflammation has not been tested. Similar to SPMs from DHA, SPMs from eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) may also play a role in the periphery, but are less abundant in the brain (Chen et al., 2013; Layé, 2010; Layé et al., 2018).

Given the above and that the aged brain has elevated baseline inflammation, declining DHA levels could potentiate the proinflammatory response to unhealthy diet consumption. Thus, in this study we tested the hypothesis that consumption of a processed-foods diet (PD), which is high in refined carbohydrates, would impair cognitive function and increase inflammatory gene expression in aged, but not young, rats. Moreover, we hypothesized that DHA supplementation would ameliorate many of these PD-induced effects. Furthermore, we investigated the impacts of both age and diet on weight gain and hypothalamic gene expression.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Subjects

Three- and 24-month old male F344×BN F1 rats (N=54, n = 7–10 per group; and two per cage) were utilized. Rats were obtained from the National Institute on Aging Rodent Colony maintained by Envigo (Indianapolis, IN), where they are exclusively available. Due to aged female rats of this strain not being available at the time these experiments were conducted, only male rats were used in this study. Future work will include the use of females. Upon arrival at our facility young rats weighed approximately 300 g and aged rats approximately 550 g. The animal colony was maintained at 22 °C on a 12-h light/dark cycle (lights on at 07:00 h). Rats were co-housed two per cage and allowed free access to food and water and were given 1 week to acclimate to colony conditions before experimentation began. All experiments were conducted in accordance with protocols approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

2.2. Diets

At study onset, young and aged rats were randomly assigned to either continue consuming their regular chow (Teklad Diets, TD.8640; energy density of 3.0 kcal/g; 32% calories from protein, 54% from complex carbohydrates, and 14% from fat), an adjusted calorie custom-designed diet to model high intake of processed food (PD; TD.200456, Envigo, energy density of 3.8 kcal/g; 19.6% calories from protein, 63.3% from refined carbohydrates, and 17.1% from fat), or the same PD containing 1% DHA by weight (PD+DHA). DHASCO oil containing 40% DHA was added to the PD+DHA diet with other fat sources slightly modified so macronutrient composition was not altered across the two diets. Carbohydrate sources in the standard chow diet came predominantly from ground wheat and wheat middlings (full ingredients list for Teklad 8604 is available online), whereas carbohydrate sources in the PD and PD+DHA diets came from cornstarch, maltodextrin, and sucrose. The macronutrient distribution for all three diets are listed in Table 1 and full diet compositions for the custom diets (PD and PD+DHA) are listed in Table 2. Rats consumed all diets ad libitum for 28 days. Body weight was measured at the beginning of the study to ensure there were no significant differences in baseline body weight and then measured twice per week for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Macronutrient distribution of diets

| Diet | Standard Chow | Processed Diet | Processed Diet + DHA |

|---|---|---|---|

| % kcal | % kcal | % kcal | |

| Protein | 32 | 19.6 | 19.6 |

| Carbohydrate | 54 | 63.3 | 63.3 |

| Fat | 14 | 17.1 | 17.1 |

Table 2.

Nutrient composition of custom diets (PD and PD+DHA)

| Diet | Processed Diet | Processed Diet + DHA |

|---|---|---|

| g/kg | g/kg | |

| Casein | 210.0 | 210.0 |

| L-Cystine | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Corn Starch | 435.1 | 435.1 |

| Maltodextrin | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| Sucrose | 90.0 | 90.0 |

| Cellulose | 37.15 | 37.15 |

| Mineral Mix, AIN-93G-MX (94046) | 35.0 | 35.0 |

| Calcium Phosphate, dibasic | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Vitamin Mix. AIN-93-VX (94047) | 15.0 | 15.0 |

| Choline Bitartrate | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| Hydrogenated Coconut oil | 31.85 | 31.85 |

| Safflower Oil | 28.0 | 30.128 |

| Olive Oil | 10.15 | 6.23 |

| DHA Oil (DHASCO, 40% DHA) | 1.79 | |

| Red Food Color | 0.1 |

2.3. Contextual Fear Conditioning

After 28 days of consuming their respective diets, rats were taken two at a time from their home cage and each placed separately in a conditioning chamber (26 L × 21 W × 24 H, cm) made of stainless steel with a transparent fiberglass door. Rats were allowed to explore the chamber for 2 minutes before the onset of a 15-second tone (76 dB), followed immediately by a 2-second footshock (1.5 mA) delivered through a removable floor of stainless steel rods that were wired to a shock generator (Coulbourn Instruments, Allentown, PA, USA). To assess lethargy or sickness, locomotion was scored during conditioning. Immediately after the termination of the shock, rats were removed from the chamber and returned to their home cage. At this point, all rats remained on their assigned diets. After 4 days, all rats were tested for fear of the conditioning context, a hippocampal-dependent task, and then for fear of the tone, an amygdala-dependent task. Chambers were cleaned with water before each animal was conditioned or tested. For the context fear test, rats were placed in the exact context in which they were conditioned (in the absence of the tone) and were observed for 6 minutes and manually scored for freezing behavior. For the auditory-cued fear test, rats were placed in a completely novel context (e.g., differently shaped and sized chamber, with bedding, toys, dim lighting) and manually scored for freezing behavior for 3 minutes. Following the 3 minutes, the tone was activated and freezing behavior was scored for an additional 3 minutes. A single tone-shock pairing in our rats consistently yields excellent conditioning (>65% freezing) in a young adult control rat (Baartman et al., 2017; Barrientos et al., 2006; Bilbo et al., 2008; Frank et al., 2010; Kwilasz et al., 2021; Spencer et al., 2017). This is optimal because it allows us to detect increased freezing (which might indicate an enhancement in conditioned memory or an exaggerated fear/anxiety-like response) or decreased freezing (which would indicate an impact on memory degradation) from baseline. Freezing is the rat’s dominant fear response and is a common measure of conditioned fear. In this case, freezing was defined as the absence of all visible movement, except for respiration. Using a time-sampling procedure, every 10 seconds each rat was manually judged in real time as either freezing or active at the instant the sample was taken by two observers who were blind to experimental conditions. Inter-rater reliability exceeded 95% for all experiments. Results are expressed as a percent of the chow-fed groups in young and aged rats.

2.4. Tissue collection

Rats were given a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital and transcardially perfused with ice-cold saline (0.9%) for 3 min to remove peripheral immune leukocytes from the CNS vasculature. Brains were rapidly extracted and placed on ice, and the hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus were dissected from the rest of the brain, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until processing for RT-PCR analysis.

2.5. RNA extraction

Hippocampus, amygdala, and hypothalamus tissues were lysed with Trizol, chloroform was added to each sample at a 1:5 concentration, and the mixture was then spun in a centrifuge at 12,000 rcf for 15 minutes at 4°C. Following centrifugation, the clear aqueous phase was used for RNA precipitation with molecular biology grade isopropanol for 10 minutes, followed by a 10 minute centrifugation at 12,000 rcf at 4°C. The resulting RNA pellet was washed in 75% ethanol and centrifuged again at 7,500 rcf for 5 minutes at 4°C, after which the supernatant was removed and the remaining RNA pellet was dissolved in DNase- and RNase-free water. RNA concentration was measured by nanodrop.

2.6. Real time PCR (RT-PCR) measurement of gene expression

Following RNA measurement, 1μg of RNA was used to synthesize cDNA using qScript cDNA SuperMix (95048-100; Quantabio,) according to kit instructions. cDNA was diluted 1:4 for RT-PCR. A detailed description of the PCR amplification protocol has been published previously (Frank et al., 2006). cDNA sequences were obtained from Genbank at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI;www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Primer sequences were designed using the Qiagen Oligo Analysis & Plotting Tool (oligos.qiagen.com/oligos/toolkit.php?) and tested for sequence specificity using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool at NCBI (Altschul et al.,1997). Primers were obtained from Invitrogen for the following genes: interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), cluster of differentiation 11b (CD11b), major histocompatibility complex class II (MHCII), NLR family pyrin domain containing 3 (NLRP3), complement component 3 (C3), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), cluster of differentiation 86 (CD86), proopiomelanocortin (POMC), neuropeptide Y (NPY), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and growth hormone secretagogue receptor 1 (GHSR1). Primer specificity was verified by melt curve analysis. All primers were designed to exclude amplification of genomic DNA. Primer sequences are listed in Table 2. PCR amplification of cDNA was performed using the Quantitect SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Formation of PCR product was monitored in real time over 40 cycles using the QuantStudio 3 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA). Relative gene expression was determined by the ΔΔCT method of qPCR analysis normalized to β-Actin. The mean ΔΔCT of the young-chow group was used as the calibrator to calculate LOG2 fold-changes (control group set to 0) in mRNA concentrations as we have done previously (Butler et al., 2020). With this method, fold changes lower than 1 (decreased gene expression) are converted to a negative number and fold changes greater than 1 (increased gene expression) are converted to a positive number so values are symmetrical on the same plot.

2.7. Data analysis

All data are presented as means +/− the standard error of the means (SEM). Statistical analyses were computed using GraphPad Prism version 7. Unequal sample sizes both within and across assays are related to the exclusion of subjects due to outliers or contamination during RNA extraction/PCR. In addition, due to animal ordering limitations by the National Institute on Aging, the desired number of animals is not always available, which also contributes to unequal sample sizes. Due to our 3 × 2 factorial design, two-way ANOVA (age × diet) was run for each dependent variable. In the case of significant interactions, Tukey’s multiple comparisons post hoc tests were run. The threshold for significance was set as α = 0.05. Only significant F-values were reported in the results section.

3. Results

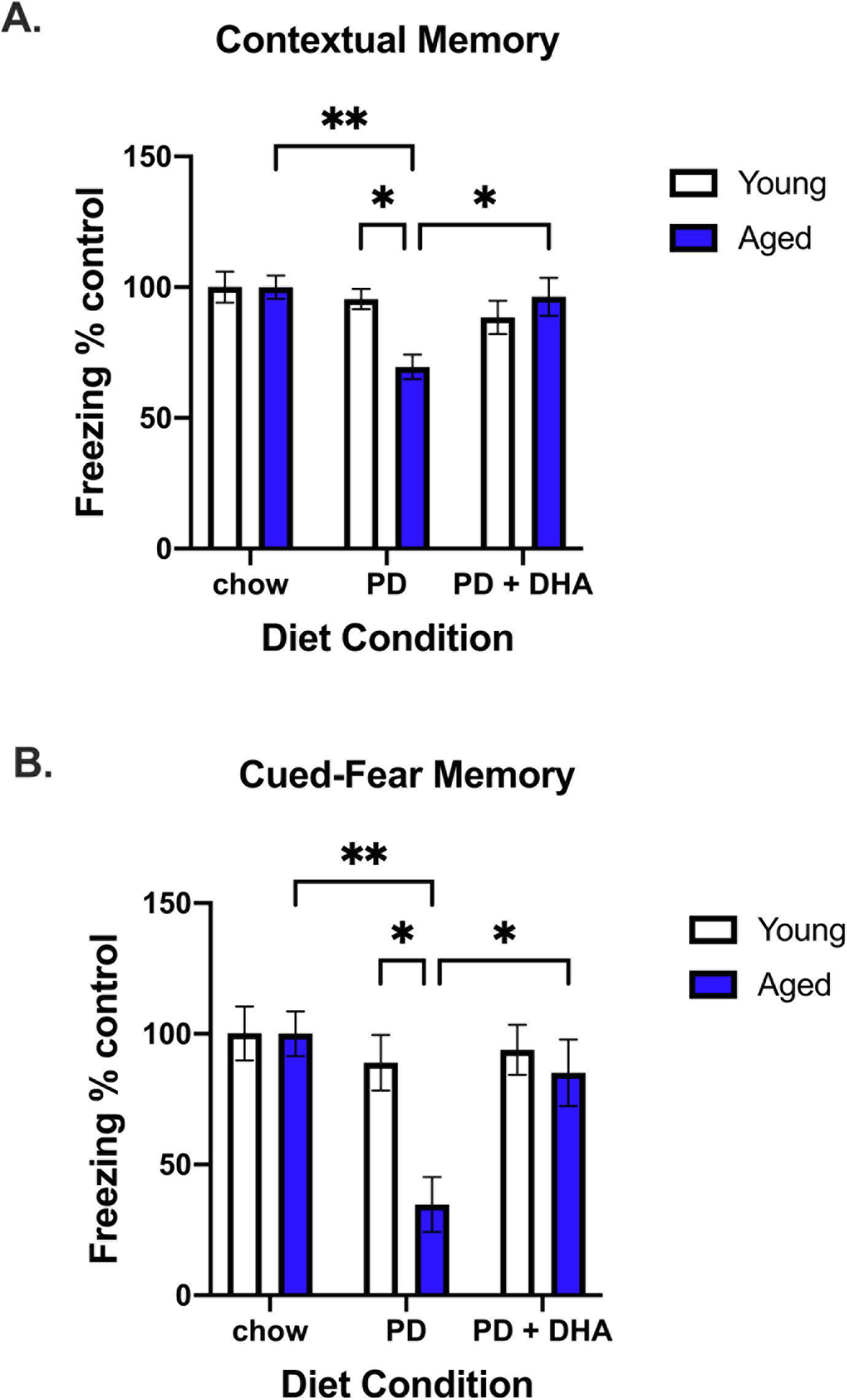

3.1. DHA prevented PD-induced deficits in contextual and cued-fear memory

We investigated the impact of a PD and DHA on both contextual and cued-fear memory. There were no differences in freezing behavior across groups during the conditioning phase (data not shown). For contextual memory, there was a significant interaction between age and diet, where aged animals fed a PD had significantly less freezing behavior than aged animals fed chow or PD+DHA (F(2,41) = 4.45, p < 0.05; Fig. 1A). For cued-fear memory, animals froze for ~ 8% of the time during the pre-tone phase of the test and there were no differences in freezing behavior across any groups during this phase (data not shown). In the presence of the tone, there was a significant age × diet interaction in that aged animals fed a PD had significantly less freezing behavior than aged animals fed a chow or PD+DHA (F(2,41) = 3.60, p < 0.05; Fig. 1B). In both tests, aged animals fed a PD displayed significantly less freezing behavior than young animals fed a PD. There were no differences in behavior on either task in young animals across diet conditions.

Figure 1.

Contextual fear conditioning data from young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) % time animals spent freezing during contextual memory test expressed as a % of age-matched control (B) % time animals spent freezing during cued-fear memory test expressed as a % of age-matched control. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01.

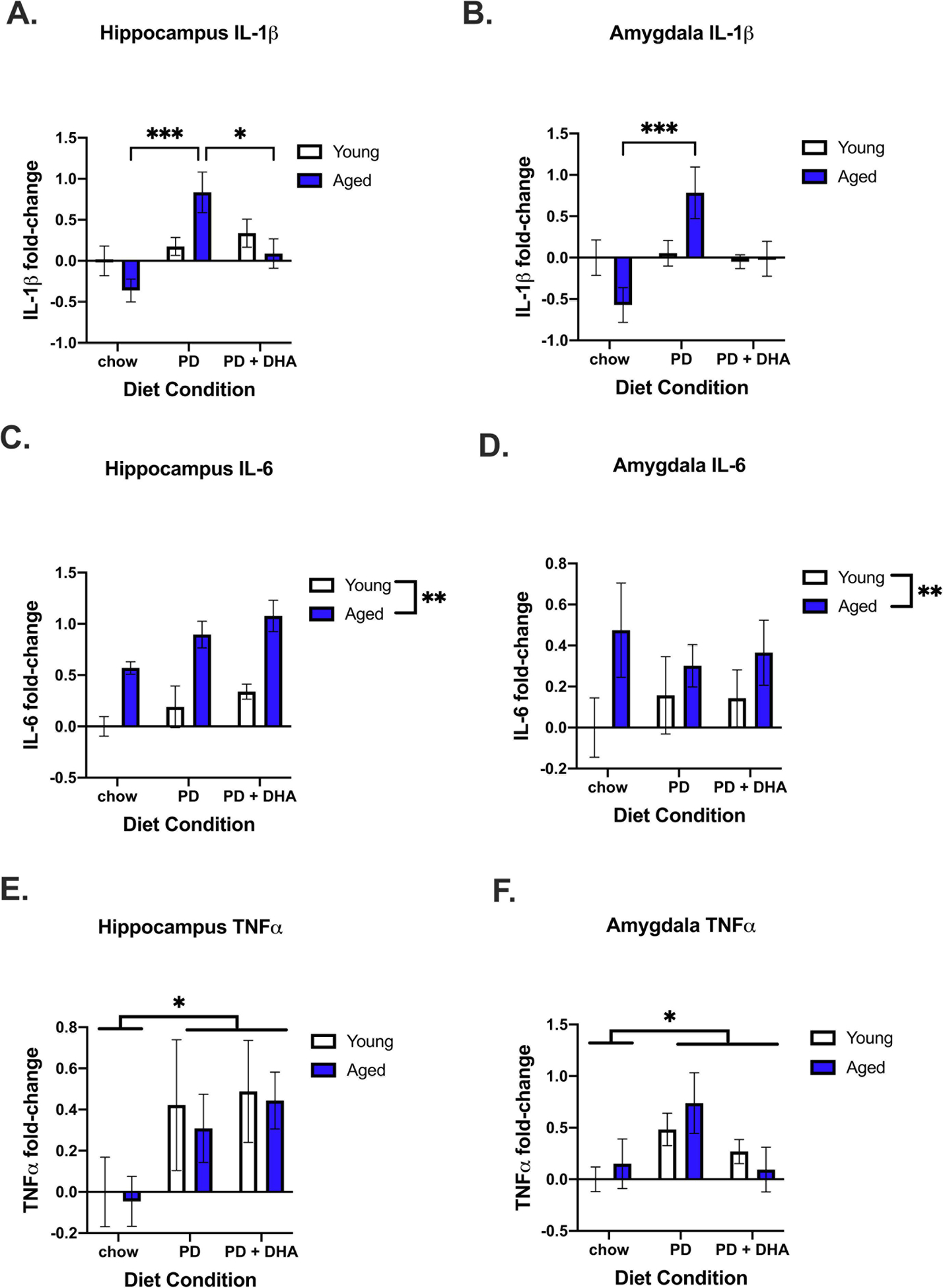

3.2. DHA prevented PD-induced increases in inflammatory gene expression in the hippocampus and amygdala.

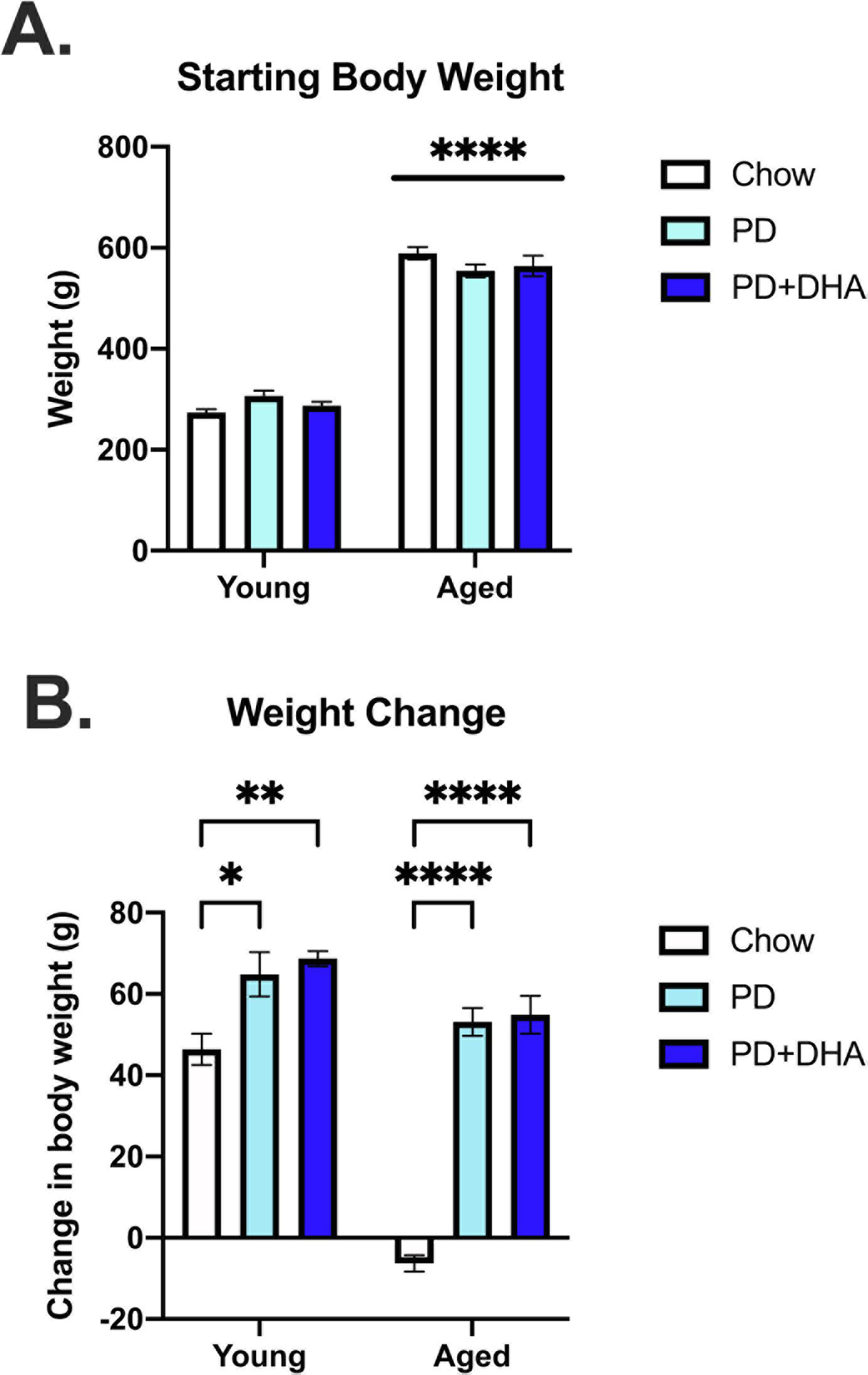

In addition to memory performance, we investigated changes in gene expression in the hippocampus and amygdala. There was a significant age × diet interaction for IL-1β expression in the hippocampus (F(2,42) = 4.619, p < 0.05; Fig. 2A). Post hoc analyses showed that aged animals fed a PD had significantly increased levels relative to aged animals fed a chow and PD+DHA. There was also a significant interaction for IL-1β in the amygdala (F(2,44) = 4.574, p < 0.05; Fig. 2B) with aged-PD animals having higher levels than aged-chow animals. For IL-6 expression, there was a main effect of age (F(1,45) = 39.08, p < 0.0001; Fig. 2C) and diet (F(2,45) = 5.155, p < 0.01; Fig. 2C) in the hippocampus and a main effect of age in the amygdala (F(1,46) = 4.467, p < 0.05; Fig. 2D), with both factors increasing expression. There was a main effect of diet to increase TNFα gene expression in both the hippocampus (F(2,47) = 3.384, p < 0.05; Fig. 2E) and amygdala (F(2,45) = 3.63, p < 0.05; Fig. 2F).

Figure 2.

Gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus and amygdala of young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal IL-1β (B) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar IL-β (C) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal IL-6 (D) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar IL-6 (E) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal TNFα (F) Log2 fold-change amygdalar TNFα. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01

We also investigated changes in genes associated with microglial reactivity. Here, we saw a significant age × diet interaction for changes in CD11b in the hippocampus (F(2,48) = 3.456, p < 0.05; Fig. 3A) and amygdala (F(2,48) = 5.098, p < 0.05; Fig. 3B). In the hippocampus, aged animals fed a PD had increased CD11b compared to aged chow-fed animals. In the amygdala, aged chow-fed animals had increased CD11b relative to young chow-fed animals and young PD-fed animals had increased expression relative to young chow-fed animals. For MHCII expression, there was a main effect of age (F(1,47) = 94.36, p < 0.0001; Fig. 3C) and diet (F(2,47) = 5.058, p < 0.05; Fig. 3C) in the hippocampus, with MHCII being elevated, and a significant interaction between age and diet in the amygdala (F(2,48) = 4.002, p < 0.05; Fig. 3D). In the amygdala, post hoc analysis for group differences in MHCII revealed aged PD-fed animals had significantly higher levels than aged chow and PD+DHA animals. In the hippocampus there was a main effect of diet on NLRP3 expression (F(2,41) = 3.775, p < 0.05; Fig. 3E) and, in the amygdala, a main effect of both age (F(1,41) = 6.421, p < 0.05; Fig. 3F) and diet (F(2,41) = 6.125, p < 0.01; Fig. 3F), with NLRP3 being increased by both variables.

Figure 3.

Microglial reactivity gene expression in the hippocampus and amygdala of young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal CD11b (B) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar CD11b (C) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal MHCII (D) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar C3 (E) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal NLRP3 (F) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar NLRP3. * p < 0.05 **** p < 0.0001.

Lastly, we looked at changes in genes associated with additional innate immune activity and synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus and amygdala. We saw a significant age × diet interaction for complement C3 in the hippocampus (F(2,44) = 12.06, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4A) but no changes in the amygdala (Fig. 4B). There was also a main effect of age with increased ICAM-1 expression in both the hippocampus (F(1,47) = 4.477, p < 0.05; Fig. 4C) and amygdala (F(1,44) = 6.344, p < 0.05; Fig. 4D). For CD86 expression, there was a significant age × diet interaction in the hippocampus (F(2,45) = 3.983, p < 0.05; Fig. 4E), with aged PD-fed animals having increased expression relative to aged chow-fed animals and young PD-fed animals. In the amygdala, there was a main effect of age (F(1,42) = 12.22, p < 0.005; Fig 4F) and diet (F(2,42) = 3.244, p < 0.05; Fig. 4F) for CD86 expression, with CD86 being increased by both variables.

Figure 4.

Additional immune-related gene expression in the hippocampus and amygdala of young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal C3 (B) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar C3 (C) Log2 fold-change in hippocampal ICAM-1 (D) Log2 fold-change in amygdalar ICAM-1 (E) Log2 fold-change in CD86 (F) Log2 fold-change in CD86. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01

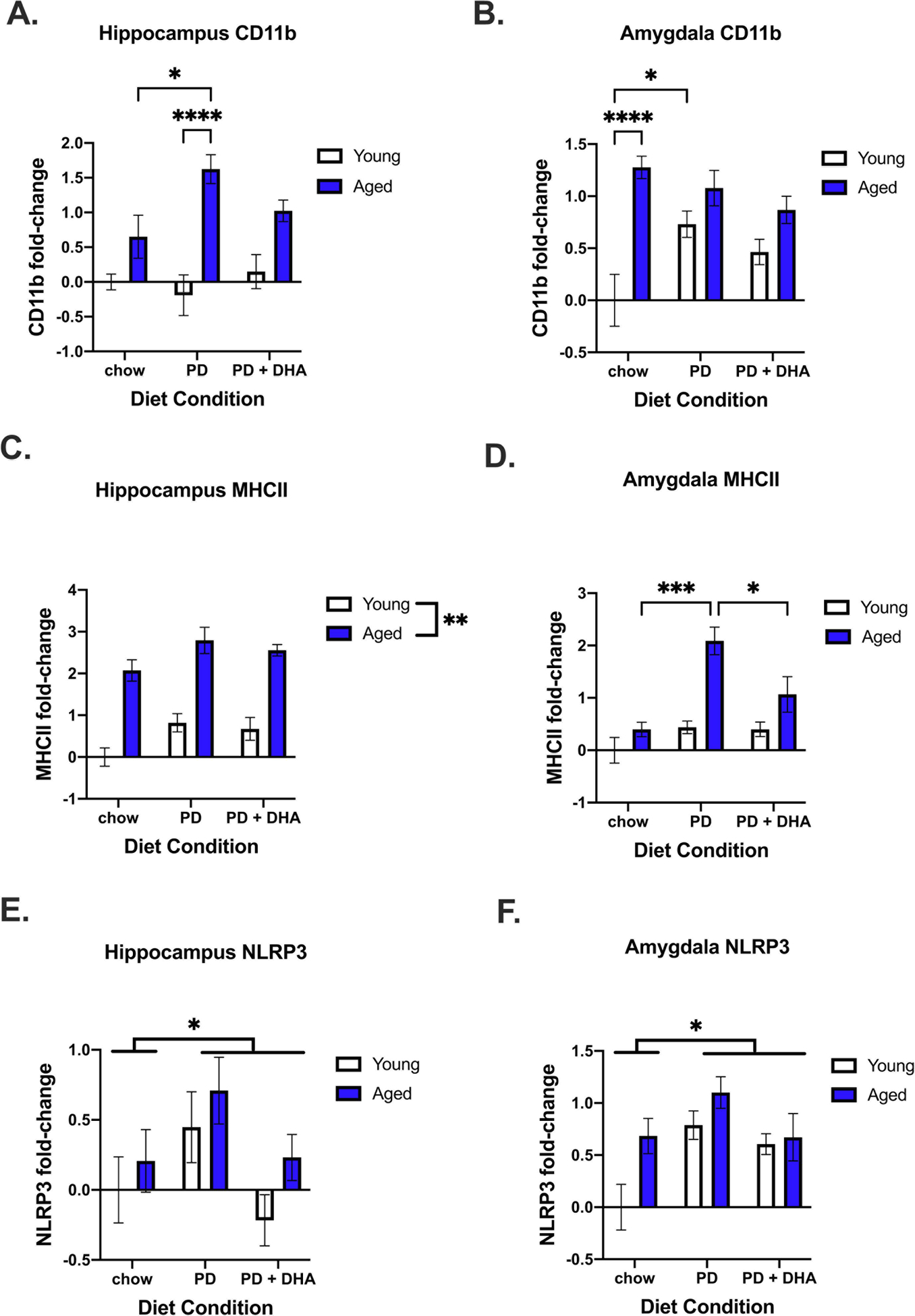

3.3. PD and PD+DHA significantly increased weight gain in young and aged rats

At the start of the experiment, aged animals weighed significantly more than young animals (F(1, 46) = 652.5, p < 0.0001), but were not different across diet condition at diet onset (p > 0.05; Fig. 5A). We investigated the impact of PD and PD+DHA on change in body weight from diet onset until the last day of the experiment. Results indicated a significant age × diet interaction (F(2,46) = 16.98, p < 0.0001; Fig. 5B). Post hoc analyses revealed significant group differences between young animals fed PD and PD+DHA, relative to young animals fed a chow diet, with both PD and PD+DHA-fed weighing more than chow-fed animals. However, this effect was greater in aged animals, relative to young (Fig 6B).

Figure 5.

Starting body weight and weight change data in young and aged rats fed a PD and PD+DHA diet. (A) Starting body weight (B) Change in body weight from beginning of experiment until the end the experiment. ** p <0.01 **** p < 0.0001

Figure 6.

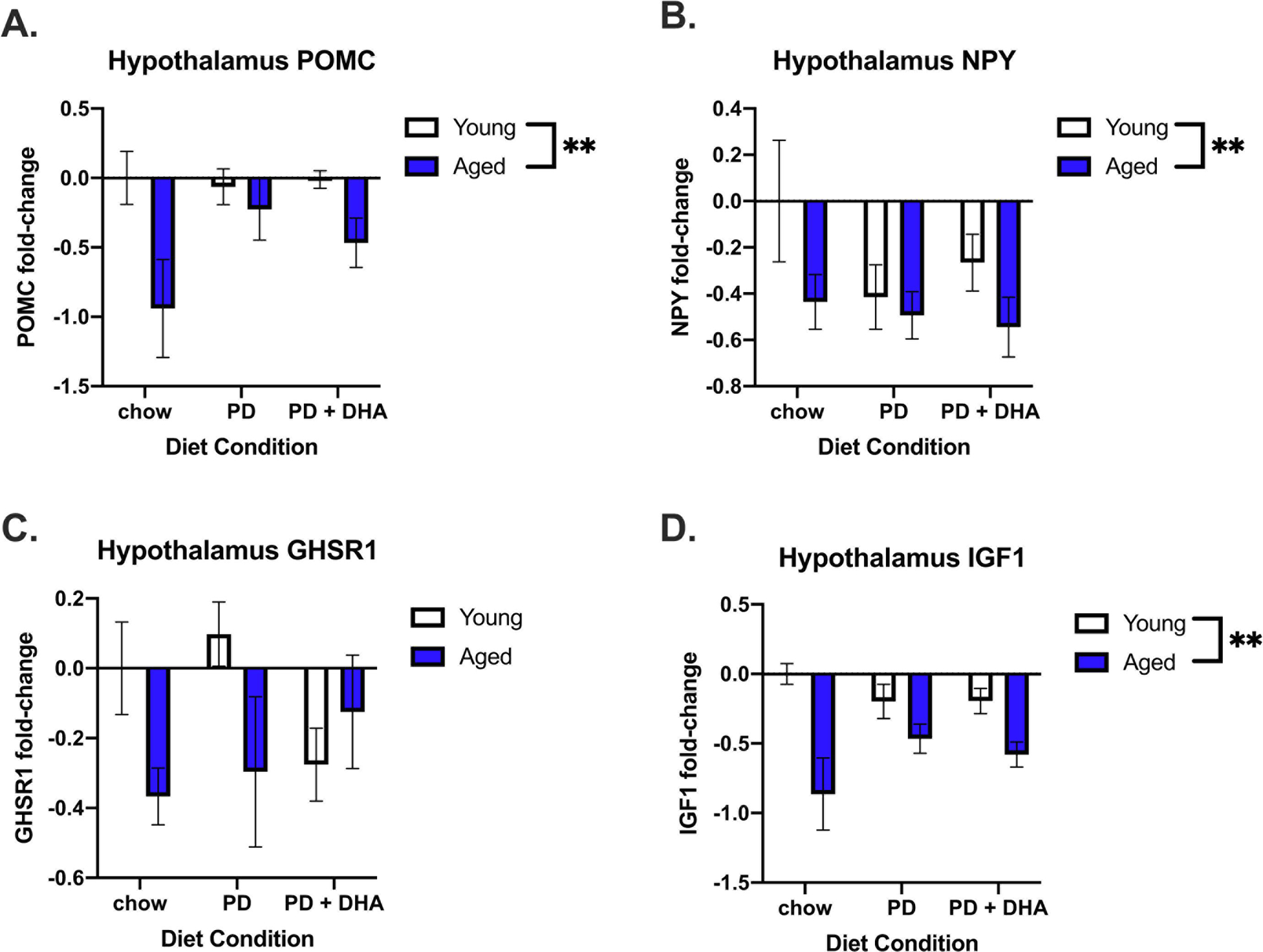

Energy homeostasis- and endocrine-related gene expression in the hypothalamus of young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) Log fold-change in POMC (B) Log fold-change in NPY (C) Log fold-change in GHSR1 (D) Log fold change in IGF-1. ** p < 0.01

3.4. Aging was associated with altered gene expression in the hypothalamus

In the hypothalamus, we investigated changes in genes associated with energy homeostasis. There was a main effect of age on POMC (F(1,45) = 8.012, p < 0.01; Fig. 6A), NPY (F(1,47) = 4.611, p < 0.05; Fig. 6B), and IGF-1 expression (F(1,47) = 16.84, p < 0.0005; Fig. 6D) where aged animals had significantly lower levels of these genes than young animals. There was no change in GHSR1 expression (Fig. 6C).

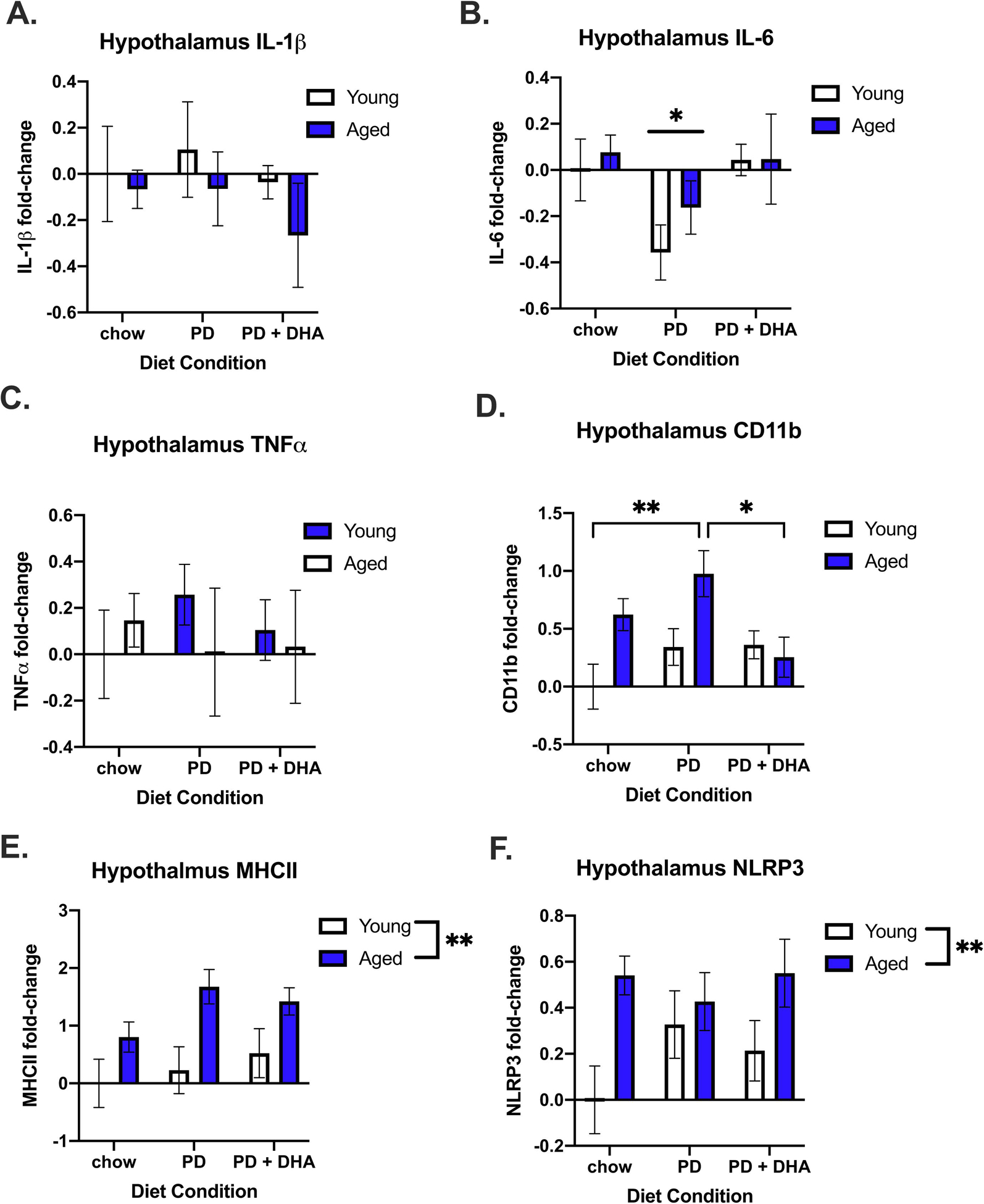

In addition to homeostasis-related genes, we investigated immune-related gene expression in the hypothalamus. There were no changes in mRNA concentration for IL-1β or TNFα across age or diet conditions (p > 0.05); Fig. 7A and 7C). However, there was a main effect of diet on IL-6 (F(1,47) = 3.507, p < 0.05; Fig. 7B), with IL-6 being decreased in PD-fed animals. There was a significant age × diet interaction for CD11b (F(2,46) = 3.309, p < 0.05; Fig. 7D.) with aged animals fed a PD having significantly higher levels than aged animals fed PD+DHA. There was also a main effect of age for MHCII (F(1,43) = 14.86, p < 0.001; Fig. 7E.) and NLRP3 (F(1,44) = 9.043, p < 0.005; Fig. 7F) with these genes being more highly expressed in aged animals than in young animals.

Figure 7.

Inflammatory gene expression in the hypothalamus of young and aged rats fed PD and PD+DHA diets. (A) Log fold-change in IL-1b (B) Log fold-change in IL-6 (C) Log fold-change in TNFa (D) Log fold-change in CD11b (E) Log fold-change in MHCII (F) Log fold-change in NLRP3. * p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01’

4. Discussion

In this study we investigated the impact of PD consumption on cognitive function, neuroinflammatory gene expression, and weight gain in young and aged male rats. Furthermore, we investigated the role of dietary DHA supplementation on mitigating any alterations associated with PD consumption. Taken together, our data suggest PD consumption impaired both hippocampal- and amygdalar-dependent memories in aged, but not young rats, and DHA supplementation prevented these behavioral impairments. Furthermore, PD consumption resulted in upregulation of multiple proinflammatory genes in the hippocampus and amygdala, most of which were ameliorated by DHA supplementation, suggesting a neuroimmune mechanism through which DHA protects against PD insults on neurobiology and behavior. We also report that PD consumption, with or without DHA supplementation, significantly increased weight gain in both young and aged rats, with the most profound increase observed in aged animals. This was accompanied with age-associated dysregulation of melanocortin and neuroendocrine-related genes, as well as age-related increases in microglial reactivity markers in the hypothalamus.

Longer-term (3+ months) PD consumption impairs cognitive function in both rodent models and humans (Gentreau et al., 2020; Kanoski and Davidson, 2010). In the current study, we extend this literature by having demonstrated a shorter-term 28-day PD consumption significantly impaired learning and memory in aged rats, with no effect on young rats at this time point. This finding also extends previous work from our lab that indicated aged animals are more vulnerable to memory impairments elicited by a short-term HFD by reporting that a PD produces similar impairments, albeit at a longer time course (Spencer et al., 2019, 2017). Importantly, we demonstrated for the first time that dietary DHA supplementation prevents cognitive deficits elicited by a PD in aged rodents, suggesting that the likely restoration of declining DHA levels in the aged brain is sufficient to restore memory function following dietary insult to the brain. It is important to note that, like HFD, PD-fed aged rats demonstrated impairments in both contextual and cued-fear memory, which predominantly rely on the hippocampus and amygdala, respectively. Simultaneous impairments of both of these types of memories in aged rats appear to be unique to diet, as other types of acute peripheral insults, such as abdominal surgery and bacterial infection, only impair contextual memory in aged rats (Barrientos et al., 2012, 2009, 2006). This dual effect on hippocampal and amygdalar-dependent memory that appears to be unique to dietary insults could be related to the notion that diet has a broader impact on brain function, impacting hippocampal, amygdalar, and hypothalamic circuitries and neurotransmitter systems that regulate stress and fear (Moon et al., 2014; Mosili et al., 2020; Tannenbaum et al., 1997).

In the hippocampus and amygdala, PD consumption increased IL-1β gene expression in aged, relative to young, rats and DHA supplementation prevented this increase. An increase in IL-1β in the hippocampus can impair learning and memory via direct inhibition of long-term potentiation, which can be mitigated by blocking IL-1β signaling (Barrientos et al., 2015). These data extend our previous findings that demonstrate a central infusion of IL-1RA, an IL-1 receptor antagonist, prevents HFD-induced cognitive impairments (Spencer et al., 2017) by showing that DHA supplementation is also sufficient to lower IL-1β gene expression following consumption of a calorically dense PD. We also report a hippocampal increase in the microglial marker CD11b in aged, PD-fed animals relative to young, with DHA supplementation preventing this increase. Consistent with previous reports (De Smedt-Peyrusse et al., 2008; Layé et al., 2018; Rey et al., 2016), these data suggest DHA might be attenuating diet-induced neuroinflammation via direct effects on microglia/macrophage reactivity. This same inflammatory mechanism is likely at play in the amygdala, where we also see an increase gene expression for IL-1β by PD consumption that was, again, prevented by DHA supplementation. This mirrors our previous findings that central blockade of IL1R also prevents amygdala-dependent memory deficits elicited by HFD in aged rats (Spencer et al., 2017). This vulnerability to diet-induced insults in aged rodents is likely due to increased baseline neuroinflammation driven by the sensitized state of aged microglia (JP et al., 2005; Niraula et al., 2016; Norden and Godbout, 2013; Romano et al., 2020) and/or increased infiltration of peripheral immune cells that occurs with aging (Dulken et al., 2019; Honarpisheh et al., 2020; Ritzel et al., 2016).

In addition to proinflammatory cytokine gene expression, we also measured changes in other indicators of innate immune function and microglial reactivity such as NLRP3, ICAM-1, CD86, and MHCII in both the hippocampus and amygdala. While there was a main effect of diet and age on NLRP3 and ICAM-1 in both regions, respectively, there was a significant interaction with CD86 expression with aged, PD-fed animals having the highest levels, relative to other groups, in the hippocampus. CD86 is another proinflammatory microglial marker that is a co-stimulatory signal required for T-cell activation (Frank et al., 2006). While aging is known to increase CD86 in the brain, this is the first report of diet increasing CD86 gene expression (Frank et al., 2006). These data pair nicely with the MHCII increase observed in the amygdala in aged, PD-fed rats, suggesting the combination of age and diet upregulates antigen presentation genes in the brain. Importantly, DHA supplementation mitigated all of these alterations. Follow-up studies are needed to determine the functional significance of CD86, MHCII, and ICAM-1 increases, with a focus on antigen presentation and T-cell recruitment to the CNS being an intriguing target.

Perhaps the most striking effect of PD consumption was on complement C3 gene expression in the hippocampus, where PD consumption increased C3 in aged animals relative to all other groups and DHA supplementation restored expression levels back to baseline. The complement system is a highly conserved multi-functional system of innate immune function where it plays a pivotal role in the proinflammatory response, interacting with inflammasomes and pattern recognition receptors (Romano et al., 2020). In the CNS, the complement system has been implicated in synapse elimination, mainly via C3 deposition at the synapse, which signals to microglia to eliminate the synapse via phagocytosis (Stevens et al., 2007). Complement C3 has also been implicated in learning and memory and neurodegenerative disease. For instance, C3 expression is increased in the brain and cerebral spinal fluid of humans with Alzheimer’s disease and mice deficient in C3 are protected against age-associated synaptic loss and cognitive decline, suggesting a causal role of C3 in this phenomenon (Shi et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2019). Here, we show for the first time that a PD can increase C3 expression in brain regions relevant to fear-conditioned memory. To the best of our knowledge, this is also the first report of DHA altering the expression of complement-related genes in the brain. Follow-up studies will include further investigation of the complement system and the role it plays in mediating microglial phagocytosis in the context of diet-induced neuroinflammation.

In general, a limitation of the current study is the use of whole hippocampal and amygdalar dissections for mRNA analysis as it does not allow for the delineation of cell-specific contributions to the observed changes in gene expression. Even in the cases of genes such as CD11b, MHCII, or CD86, it is not possible to distinguish between resident microglia and infiltrating macrophages or dendritic cells. Thus, in an effort to understand the cellular mechanisms driving neuroimmune signaling in response to diet, future experiments will involve the isolation of monocytes from brain tissue from all diet and age conditions and identify microglial phenotype as well as the relative contribution of infiltrating macrophages, dendritic cells, and T-cells via flow cytometry and single-cell RNA sequencing.

Overconsumption of refined and processed foods leads to significant weight gain in most species. Indeed, previous studies illustrate that rats fed a diet rich in refined carbohydrates increases weight gain relative to standard chow-fed rats (Kanoski and Davidson, 2010; Spadaro et al., 2015). Because of this, we aimed to directly compare changes in weight gain between young and aged animals fed a PD. Due to our rats being pair-housed to avoid isolation-induced stress and inflammation (Barrientos et al., 2003), accurate food intake data for each individual animal could not be calculated. Thus, differences in the impact of these diets on feeding behavior between young and aged rats and between chow-fed controls is unknown and is an important caveat regarding interpretation of body weight and hypothalamic gene expression data. The data reported here replicate previous findings as rats fed a PD show a significant increase in weight gain across the 28-day study. Our data extend previous reports by doing a direct age comparison that reveals a dramatically elevated weight gain in aged rats fed a PD relative to young, when compared to their respective chow-fed controls. However, it is noteworthy that the young, chow-fed rats are still growing, thus gaining weight whereas the aged, chow-fed rats maintained their baseline body weight over the course of the 28-day study. Therefore, while the young, PD and PD+DHA-fed rats still gained significantly more weight than their chow-fed counterparts, the significance of this increase is harder to appreciate in young rats than it is in aged rats.

Interestingly, DHA supplementation of the PD did not alter its impact on weight gain in young or aged animals. These data are inconsistent with a previous report showing DHA supplementation prevented weight gain in Wistar rats fed a high fat, high carbohydrate diet (Poudyal et al., 2013). This discrepancy could be due to strain differences between the rats, the composition of the diet the DHA was added to, or the time course of the DHA supplementation, which was 8 weeks in the referenced study compared to 4 weeks in the current study. The fact that DHA did not impact weight gain in young or aged rats, but did prevent PD-induced memory deficits, suggest the impact of diet on memory is not yoked to weight gain in this study.

The exaggerated weight gain in aged animals due to PD consumption could be explained by alterations in genes associated with feeding and energy homeostasis, that were not seen in the young rats. Specifically, aged animals showed a significant decrease in POMC and NPY expression, two genes intricately involved in the regulation of body weight (Sohn, 2015). The protein-product of the POMC gene is post-translationally cleaved into several neuropeptides, including alpha melanocyte stimulating hormone, which decreases food intake after binding to melanocortin receptor 4 (Sohn, 2015). On the contrary, NPY is released from NPY neurons and stimulates food intake by binding to PYY receptors (Sohn, 2015). Surprisingly, there was no effect of diet on these genes despite the significant weight gain, although it should be noted we did not measure protein concentrations of these markers so it is unknown if there is a discrepancy between mRNA and protein levels in this study. However, for aged animals, a significant decrease in both genes suggests a dysregulation of the melanocortin system at baseline, which could leave them vulnerable to obesogenic diets. These findings are in line with previous reports that showed both of these genes and/or proteins are decreased in the hypothalamus of aged rodents (Kim and Choe, 2019; Kowalski et al., 1992; Yang et al., 2012).

While previous reports have causally linked hypothalamic inflammation to weight gain induced by HFD consumption (Valdearcos et al., 2014), less is known about the impacts of a relatively low-fat, high refined carbohydrate diet on hypothalamic inflammation. Here, we see no change in mRNA levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the hypothalamus across all age and diet conditions. There was, however, a significant age × diet interaction for changes in CD11b, with aged animals having increased expression relative to young. Interestingly, aged rats fed a DHA-supplemented PD had reduced hypothalamic CD11b expression than PD-fed aged rats, consistent with DHA’s ability to reduce microglial reactivity (Chang et al., 2015; De Smedt-Peyrusse et al., 2008; Layé, 2010). There were also age-associated increases in MHCII, another marker of microglial reactivity, and increases in the NLRP3 mRNA, both of which are consistent with previous studies showing increased inflammatory gene expression in the aged hypothalamus (Kim and Choe, 2019). Aging was also associated with a decrease in hypothalamic IGF-1 gene expression, which has well-documented neuroprotective properties and direct actions on microglia (Bianchi et al., 2017; Serhan et al., 2020). These alterations in hypothalamic neuroimmune-related genes in conjunction with baseline alterations in homeostatic genes associated with aging could explain the increased weight gain observed in aged rats fed the PD, although future studies are required to directly test this hypothesis.

As mentioned earlier, it is important to note that due to aged female F344×BN F1 rats not being available at the time of this study, we were unable to conduct these experiments in both male and female subjects. Thus, these data should not be generalized to females as there are well-documented sex differences in learning and memory, neuroinflammatory signaling, and energy homeostasis (Barrientos et al., 2019; Hwang et al., 2010; Lovejoy and Sainsbury, 2009). Despite the fact several studies have suggested female rats and women have higher plasma DHA levels than males (Giltay et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2016), one study showed there were no sex differences in brain DHA levels of young adult rats fed a standard chow diet (Kitson et al., 2012). However, given the direct effects of sex hormones on microglia function in females and how this changes with age, and the direct effects of DHA on microglia function in both sexes, it is plausible for there to be differential age-associated changes in the anti-inflammatory effects of DHA between males and females (Layé et al., 2018).

Overall, these data provide compelling evidence that a PD enriched with refined carbohydrates impairs cognitive function, increases neuroinflammatory gene expression, and leads to increased weight gain in aged rats. DHA supplementation of the PD prevented these changes in cognitive function and most of the changes in neuroinflammatory gene expression, but not changes in weight gain. The fact that DHA did not impact all genes investigated in this study could be related to differential effects of DHA on cell types contributing to the changes in gene expression. For example, differential effects of DHA on resident versus infiltrating immune cells. Also, there are several instances where DHA supplementation attenuated increases in gene expression but was not statistically significant, likely due to high variability. As mentioned earlier, we do not have accurate food intake data from these rats so it is difficult to determine the exact dose of DHA these animals consumed. However, based on previous experiments, we know rats consume ~ 20–22 g of food per day, which equates to ~ 50 mg/kg/day for a rat, based on the concentration of dietary DHA in this study. This is a similar amount of DHA used in a previous experiment looking at the neuroprotective effects of DHA (Butt et al., 2017). Based on previously published equations for translating dose in rodents to humans, our diet formulation translates to ~ 500mg/day of DHA for a 60kg human, making this a highly translational amount of DHA (Butt et al., 2017; Reagan Shaw et al., 2008).

Importantly, this customized PD is similar to the widely used AIN-93 semi-purified rodent diet, which also contains high levels of refined carbohydrates and low levels of fiber (Klurfeld et al., 2021). Aside from modest, but significant, weight gain, these diets did not impact cognition or gene expression in young rats. While this does not seem to be a concern for researchers using young adult rodents, these data offer important considerations for future studies that utilize a semi-purified/processed diet in aged rodents, especially if these diets are used as control diets, which they often are. Moving forward, future work will investigate specific cellular mechanisms that are driving diet-induced (both PD and HFD) neuroinflammation and cognitive decline in aged rats of both sexes, with a focus on innate and adaptive immune system interactions and the complement system.

Table 3.

Primer sequences used for RT-PCR analysis

| Genes | Species | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1β | Rat | CCTTGTGCAAGTGTCTGAAG | GGGCTTGGAAGCAATCCTTA |

| IL-6 | Rat | AGAAAAGAGTTGTGCAATGGCA | GGCAAATTTCCTGGTTATATCC |

| TNFα | Rat | CAAGGAGGAGAAGTTCCCA | TTGGTGGTTTGCTACGACG |

| CD11b | Rat | CTGGGAGATGTGAATGGAG | ACTGATGCTGGCTACTGATG |

| MHCII | Rat | AGCACTGGGAGTTTGAAGAG | AAGCCATCACCTCCTGGTAT |

| NLRP3 | Rat | AGAAGCTGGGGTTGGTGAATT | GTTGTCTAACTCCAGCATCTG |

| C3 | Rat | CCTCTGACCTCCTCCTCCATCTTC | GCTCAGCATTCCATCGTCCTTCTC |

| ICAM-1 | Rat | TTCCTTCTCTATTACCCCTG | GGTGTTCCTTTTCTTCTCTTGC |

| CD86 | Rat | TAGGGATAACCAGGCTCTAC | CGTGGGTGTCTTTTGCTGTA |

| POMC | Rat | CCTGTGAAGGTGTACCCCAATGTC | CACGTTCTTGATGATGGCGTTC |

| NPY | Rat | CCCGCCCGCCATGATGCTAGG | CCGCCCGGATTGTCCGGCTTG |

| GHSR1 | Rat | GTCGAGCGCTACTTCGC | GTACTGGCTGATCTGAGC |

| IGF1 | Rat | TTTTACTTCAACAAGCCCACA | CATCCACAATGCCCGTCT |

| βAct | Rat | TTCCTTCCTGGGTATGGAAT | GAGGAGCAATGATCTTGATC |

Highlights.

A processed-foods diet (PD) impaired memory in aged male rats

PD increased inflammatory genes in the hippocampus and amygdala of aged rats

DHA supplementation prevented memory deficits in PD-fed aged rats

DHA supplementation ameliorated increases in inflammatory gene expression

PD consumption led to increased weight gain in young and aged rats

Acknowledgements:

This work is supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Aging AG028271 and AG067061 (to R.M.B), from the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (DE014320) to M.J.B., and the Ohio Agriculture Research and Development Center, OSU (to M.A.B.)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baartman TL, Swanepoel T, Barrientos RM, Laburn HP, Mitchell D, Harden LM, 2017. Divergent effects of brain interleukin-1ß in mediating fever, lethargy, anorexia and conditioned fear memory. Behav. Brain Res 324, 155–163. doi: 10.1016/J.BBR.2017.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Brunton PJ, Lenz KM, Pyter L, Spencer SJ, 2019. Neuroimmunology of the female brain across the lifespan: Plasticity to psychopathology. Brain. Behav. Immun doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Hein AM, Frank MG, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2012. Intracisternal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents postoperative cognitive decline and neuroinflammatory response in aged rats. J. Neurosci 32, 14641–14648. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2173-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Higgins EA, Biedenkapp JC, Sprunger DB, Wright-Hardesty KJ, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF, 2006. Peripheral infection and aging interact to impair hippocampal memory consolidation. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 723–732. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Kitt MM, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2015. Neuroinflammation in the normal aging hippocampus. Neuroscience. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Sprunger DB, Campeau S, Higgins EA, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF, 2003. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor mRNA downregulation produced by social isolation is blocked by intrahippocampal interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Neuroscience 121, 847–853. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00564-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos RM, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF, 2009. Characterization of the sickness response in young and aging rats following E. coli infection. Brain. Behav. Immun 23, 450–454. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi VE, Locatelli V, Rizzi L, 2017. Neurotrophic and neuroregenerative effects of GH/IGF1. Int. J. Mol. Sci 18. doi: 10.3390/ijms18112441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilbo SD, Barrientos RM, Eads AS, Northcutt A, Watkins LR, Rudy JW, Maier SF, 2008. Early-life infection leads to altered BDNF and IL-1β mRNA expression in rat hippocampus following learning in adulthood. Brain. Behav. Immun 22, 451–455. doi: 10.1016/J.BBI.2007.10.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MJ, Cole RM, Deems NP, Belury MA, Barrientos RM, 2020. Fatty food, fatty acids, and microglial priming in the adult and aged hippocampus and amygdala. Brain. Behav. Immun doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butt C, Harrison J, Rowe R, Jones J, Wynalda K, Salem N, Lifshitz J, Pauly J, 2017. Selective Reduction of Brain Docosahexaenoic Acid after Experimental Brain Injury and Mitigation of Neuroinflammatory Outcomes with Dietary DHA. Curr. Res. Concussion 04, e38–e54. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1606836 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang PKY, Khatchadourian A, McKinney AA, Maysinger D, 2015. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): A modulator of microglia activity and dendritic spine morphology. J. Neuroinflammation 12, 1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0244-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CT, Domenichiello AF, Trépanier MO, Liu Z, Masoodi M, Bazinet RP, 2013. The low levels of eicosapentaenoic acid in rat brain phospholipids are maintained via multiple redundant mechanisms. J. Lipid Res 54, 2410–2422. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M038505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smedt-Peyrusse V, Sargueil F, Moranis A, Harizi H, Mongrand S, Layé S, 2008. Docosahexaenoic acid prevents lipopolysaccharide-induced cytokine production in microglial cells by inhibiting lipopolysaccharide receptor presentation but not its membrane subdomain localization. J. Neurochem 105, 296–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulken BW, Buckley MT, Navarro Negredo P, Saligrama N, Cayrol R, Leeman DS, George BM, Boutet SC, Hebestreit K, Pluvinage JV, Wyss-Coray T, Weissman IL, Vogel H, Davis MM, Brunet A, 2019. Single-cell analysis reveals T cell infiltration in old neurogenic niches. Nature 571, 205–210. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1362-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Barrientos RM, Biedenkapp JC, Rudy JW, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2006. mRNA up-regulation of MHC II and pivotal pro-inflammatory genes in normal brain aging. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 717–722. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank MG, Barrientos RM, Hein AM, Biedenkapp JC, Watkins LR, Maier SF, 2010. IL-1RA blocks E. coli-induced suppression of Arc and long-term memory in aged F344 × BN F1 rats. Brain. Behav. Immun 24, 254–262. doi: 10.1016/J.BBI.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gentreau M, Chuy V, Féart C, Samieri C, Ritchie K, Raymond M, Berticat C, Artero S, 2020. Refined carbohydrate-rich diet is associated with long-term risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s disease in apolipoprotein E ε4 allele carriers. Alzheimer’s Dement. 16, 1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/alz.12114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giltay EJ, Gooren LJG, Toorians AWFT, Katan MB, Zock PL, 2004. Docosahexaenoic acid concentrations are higher in women than in men because of estrogenic effects. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 80, 1167–1174. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.5.1167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes JAS, Silva JF, Marçal AP, Silva GC, Gomes GF, de Oliveira ACP, Soares VL, Oliveira MC, Ferreira AVM, Aguiar DC, 2020. High-refined carbohydrate diet consumption induces neuroinflammation and anxiety-like behavior in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem 77, 108317. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.108317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross LS, Li L, Ford ES, Liu S, 2004. Increased consumption of refined carbohydrates and the epidemic of type 2 diabetes in the United States: An ecologic assessment. Am. J. Clin. Nutr 79, 774–779. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honarpisheh P, Blixt FW, Blasco Conesa MP, Won W, d’Aigle J, Munshi Y, Hudobenko J, Furr JW, Mobley A, Lee J, Brannick KE, Zhu L, Hazen AL, Bryan RM, McCullough LD, Ganesh BP, 2020. Peripherally-sourced myeloid antigen presenting cells increase with advanced aging. Brain. Behav. Immun 90, 235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.08.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang LL, Wang CH, Li TL, Chang SD, Lin LC, Chen CP, Chen CT, Liang KC, Ho IK, Yang WS, Chiou LC, 2010. Sex differences in high-fat diet-induced obesity, metabolic alterations and learning, and synaptic plasticity deficits in mice. Obesity 18, 463–469. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JP G, C. J, A. J, R. AF, B. BM, K. KW, J. RW, 2005. Exaggerated neuroinflammation and sickness behavior in aged mice following activation of the peripheral innate immune system. FASEB J. 19, 1329–1331. doi: 10.1096/FJ.05-3776FJE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanoski SE, Davidson TL, 2010. Different Patterns of Memory Impairments Accompany Short- and Longer-Term Maintenance on a High-Energy Diet. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Behav. Process 36, 313–319. doi: 10.1037/a0017228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Choe HK, 2019. Role of hypothalamus in aging and its underlying cellular mechanisms. Mech. Ageing Dev doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2018.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitson AP, Smith TL, Marks KA, Stark KD, 2012. Tissue-specific sex differences in docosahexaenoic acid and Δ6-desaturase in rats fed a standard chow diet. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab 37, 1200–1211. doi: 10.1139/h2012-103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klurfeld DM, Gregory JF, Fiorotto ML, 2021. Should the AIN-93 Rodent Diet Formulas be Revised? J. Nutr 151, 1380–1382. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxab041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski C, Micheau J, Corder R, Gaillard R, Conte-Devolx B, 1992. Age-related changes in cortico-releasing factor, somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, methionine enkephalin and β-endorphin in specific rat brain areas. Brain Res. 582, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90314-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwilasz AJ, Todd LS, Duran-Malle JC, Schrama AEW, Mitten EH, Larson TA, Clements MA, Harris KM, Litwiler ST, Wang X, Van Dam AM, Maier SF, Rice KC, Watkins LR, Barrientos RM, 2021. Experimental autoimmune encephalopathy (EAE)-induced hippocampal neuroinflammation and memory deficits are prevented with the non-opioid TLR2/TLR4 antagonist (+)-naltrexone. Behav. Brain Res 396, 112896. doi: 10.1016/J.BBR.2020.112896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labrousse VF, Nadjar A, Joffre C, Costes L, Aubert A, Grégoire S, Bretillon L, Layé S, 2012. Short-term long chain Omega3 diet protects from neuroinflammatory processes and memory impairment in aged mice. PLoS One 7, 36861. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layé S, 2010. Polyunsaturated fatty acids, neuroinflammation and well being. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 82, 295–303. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2010.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layé S, Nadjar A, Joffre C, Bazinet RP, 2018. Anti-inflammatory effects of omega-3 fatty acids in the brain: Physiological mechanisms and relevance to pharmacology. Pharmacol. Rev 70, 12–38. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YH, Brown JA, DiMartino C, Dahms I, Salem N, Hibbeln JR, 2016. Differences in long chain polyunsaturates composition and metabolism in male and female rats. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 113, 19–27. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy JC, Sainsbury A, 2009. Sex differences in obesity and the regulation of energy homeostasis: Etiology and pathophysiology. Obes. Rev doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2008.00529.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNamara RK, Liu Y, Jandacek R, Rider T, Tso P, 2008. The aging human orbitofrontal cortex: Decreasing polyunsaturated fatty acid composition and associated increases in lipogenic gene expression and stearoyl-CoA desaturase activity. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fat. Acids 78, 293–304. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2008.04.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon ML, Joesting JJ, Lawson MA, Chiu GS, Blevins NA, Kwakwa KA, Freund GG, 2014. The saturated fatty acid, palmitic acid, induces anxiety-like behavior in mice. Metabolism 63, 1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/J.METABOL.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosili P, Mkhize BC, Ngubane P, Sibiya N, Khathi A, 2020. The dysregulation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in diet-induced prediabetic male Sprague Dawley rats. Nutr. Metab 2020 171 17, 1–12. doi: 10.1186/S12986-020-00532-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niraula A, Sheridan JF, Godbout JP, 2016. Microglia Priming with Aging and Stress. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017 421 42, 318–333. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norden DM, Godbout JP, 2013. Review: Microglia of the aged brain: primed to be activated and resistant to regulation. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol 39, 19–34. doi: 10.1111/J.1365-2990.2012.01306.X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poudyal H, Panchal SK, Ward LC, Brown L, 2013. Effects of ALA, EPA and DHA in high-carbohydrate, high-fat diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. J. Nutr. Biochem 24, 1041–1052. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2012.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N, 2008. Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 22, 659–661. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-9574lsf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rey C, Nadjar A, Buaud B, Vaysse C, Aubert A, Pallet V, Layé S, Joffre C, 2016. Resolvin D1 and E1 promote resolution of inflammation in microglial cells in vitro. Brain. Behav. Immun 55, 249–259. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritzel RM, Crapser J, Patel AR, Verma R, Grenier JM, Chauhan A, Jellison ER, McCullough LD, 2016. Age-Associated Resident Memory CD8 T Cells in the Central Nervous System Are Primed To Potentiate Inflammation after Ischemic Brain Injury. J. Immunol 196, 3318–3330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1502021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano R, Giardino G, Cirillo E, Prencipe R, Pignata C, 2020. Complement system network in cell physiology and in human diseases. Int. Rev. Immunol doi: 10.1080/08830185.2020.1833877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serhan A, Aerts JL, Boddeke EWGM, Kooijman R, 2020. Neuroprotection by Insulin-like Growth Factor-1 in Rats with Ischemic Stroke is Associated with Microglial Changes and a Reduction in Neuroinflammation. Neuroscience 426, 101–114. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.11.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Q, Colodner KJ, Matousek SB, Merry K, Hong S, Kenison JE, Frost JL, Le KX, Li S, Dodart JC, Caldarone BJ, Stevens B, Lemere CA, 2015. Complement C3-deficient mice fail to display age-related hippocampal decline. J. Neurosci 35, 13029–13042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1698-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shively CA, Appt SE, Vitolins MZ, Uberseder B, Michalson KT, Silverstein-Metzler MG, Register TC, 2019. Mediterranean versus Western Diet Effects on Caloric Intake, Obesity, Metabolism, and Hepatosteatosis in Nonhuman Primates. Obesity 27, 777–784. doi: 10.1002/oby.22436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn JW, 2015. Network of hypothalamic neurons that control appetite. BMB Rep. 48, 229–233. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2015.48.4.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spadaro PA, Naug HL, Du Toit EF, Donner D, Colson NJ, 2015. A refined high carbohydrate diet is associated with changes in the serotonin pathway and visceral obesity. Genet. Res. (Camb) 97. doi: 10.1017/S0016672315000233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, Basri B, Sominsky L, Soch A, Ayala MT, Reineck P, Gibson BC, Barrientos RM, 2019. High-fat diet worsens the impact of aging on microglial function and morphology in a region-specific manner. Neurobiol. Aging 74, 121–134. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer SJ, D’Angelo H, Soch A, Watkins LR, Maier SF, Barrientos RM, 2017. High-fat diet and aging interact to produce neuroinflammation and impair hippocampal- and amygdalar-dependent memory. Neurobiol. Aging 58, 88–101. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens B, Allen NJ, Vazquez LE, Howell GR, Christopherson KS, Nouri N, Micheva KD, Mehalow AK, Huberman AD, Stafford B, Sher A, Litke AMM, Lambris JD, Smith SJ, John SWM, Barres BA, 2007. The Classical Complement Cascade Mediates CNS Synapse Elimination. Cell 131, 1164–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannenbaum BM, Brindley DN, Tannenbaum GS, Dallman MF, McArthur MD, Meaney MJ, 1997. High-fat feeding alters both basal and stress-induced hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity in the rat. 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.6.E1168273. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdearcos M, Robblee MM, Benjamin DI, Nomura DK, Xu AW, Koliwad SK, 2014. Microglia Dictate the Impact of Saturated Fat Consumption on Hypothalamic Inflammation and Neuronal Function. Cell Rep. 9, 2124–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.11.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiser MJ, Butt CM, Mohajeri MH, 2016. Docosahexaenoic acid and cognition throughout the lifespan. Nutrients. doi: 10.3390/nu8020099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, Dejanovic B, Gandham VD, Gogineni A, Edmonds R, Schauer S, Srinivasan K, Huntley MA, Wang Y, Wang TM, Hedehus M, Barck KH, Stark M, Ngu H, Foreman O, Meilandt WJ, Elstrott J, Chang MC, Hansen DV, Carano RAD, Sheng M, Hanson JE, 2019. Complement C3 Is Activated in Human AD Brain and Is Required for Neurodegeneration in Mouse Models of Amyloidosis and Tauopathy. Cell Rep. 28, 2111–2123.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.07.060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SB, Tien AC, Boddupalli G, Xu AW, Jan YN, Jan LY, 2012. Rapamycin ameliorates age-dependent obesity associated with increased mTOR signaling in hypothalamic POMC neurons. Neuron 75, 425–436. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]