Abstract

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) encompass a wide range of conditions that arise due to progressive degeneration and ultimate loss of nerve cells in the brain and peripheral nervous system. NDDs such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’s disease negatively impact both length and quality of life, without effective disease-modifying treatments. Herein, we review the use of genome-scale metabolic models, network-based approaches and integration with multi-omics data to identify key biological processes that characterize NDDs. We describe powerful systems biology approaches for modeling NDD pathophysiology by leveraging in silico models that are informed by patient-derived multi-omics data. These approaches can enable mechanistic insights into NDD-specific metabolic dysregulations that can be leveraged to identify potential metabolic markers of disease and pre-disease states.

Introduction

Neurodegenerative diseases (NDD) are a major cause of morbidity and dependency among older people. Over the past fifty years these diseases have become increasingly prevalent as global life expectancy increased from 66.2 to 73.0 years [1,2]. Without a change in our trajectory, the number of Alzheimer’s dementia cases in Americans age 65 and above is predicted to be 13.8 million by 2060 [3]. Parkinson’s disease case burden in the US is predicted to rise to more than one million people by 2030 [4]. Aging is a critical risk factor for many NDDs including Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and Huntington’s disease (HD) that afflict millions of people worldwide [5,6]. By definition, these diseases involve progressive damage to cells in the brain and affect the sensory and/or motor functions and cognitive abilities of the individuals [7]. AD is characterized by cognitive impairment, language difficulty, problems with orientation, attention, and carrying out simple daily tasks [8]. Parkinson’s signs and symptoms vary between individuals and can range from tremors, rigid muscles, bradykinesia, gradual decrease in unconscious movements and change in behavior [9]. HD affects the motor, cognitive, behavioral, psychological and emotional faculties of the individual [10]. As diseases with complex etiologies with many different known risk factors, it is important to understand the disease manifestation and pathophysiology in a systems context to inform the development of new therapies for the treatment of the diseases.

Aging is accompanied by progressive declines in energy metabolic capacity in the brain, which is accompanied by substantial individual variability in the rate of this decline [5,6,11]. This decline in metabolic capacity is one of the common physiological processes associated with NDDs. Longitudinal studies of NDDs are hampered by the prolonged prodromal period, and the clear safety issues that impede accessing primary CNS tissue during life. The lack of inexpensive, effective biomarkers coupled with the long prodromal period make it difficult to screen for adequate numbers of at-risk individuals from whom biological samples can be obtained and analyzed in a longitudinal manner. Subsequently, the field often utilizes data generated from postmortem brain tissue samples, from non-invasive imaging, or measures from peripheral sources such as the blood to investigate the physiological changes associated with initiation and progression of NDDs [12,13]. Most in vitro models focus on the function of a specific cell type and, while informative, are unable to adequately capture the complex interactions among immune, neuronal and other cell types important for vascularization, metabolism and aging. Animal model systems of NDDs are also frequently used and provide insight, but there are major challenges in translating findings from these model systems to humans due to profound differences in disease complexity, physiological response, lack of environmental and microbiome exposure and immunological response, and the different time scales of aging [14,15]. In this scenario, to bridge the gap between in vitro and in vivo approaches, in silico techniques that allow us to translate findings in the context of the surrounding systems hold promise to help identify marker patterns associated with the diseases, predict disease trajectories and design novel molecules or identify drugs that might be repositioned for treatment [16–18].

Metabolic dysfunction is an important factor associated with neurodegenerative disorders. Dysfunction in glucose homeostasis is associated with cognitive decline and pathophysiology in AD, PD and HD [19]. Additionally, altered lipid metabolism, mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress are also associated with the negative endophenotypes of AD, PD and HD [20–22]. Challenges abound in performing experimental approach that capture the complexities of the human brain, making modeling an important framework piecing together disparate information to yield mechanistic insights and hypotheses to be tested through the means available in humans (e.g., postmortem brain tissue, peripheral measurements, and neuroimaging). One such computational tool is metabolic network modeling [23]. This approach integrates patient-derived multi-omics data in the form of transcriptomics, proteomics, and/or metabolomics within the context of the enzyme-catalyzed biochemistry of the cell [24,25]. Such models can be used to help identify metabolic changes in the brain contributing to human health and disease. These models include brain region-specific metabolic networks that have been developed to analyze differences in the brains of people with AD compared with control samples [26]. About 30 different brain tissue-specific metabolic networks were constructed using metabolic network topology and expression data [27]. Such models can be used by the research community to explore in silico differences and identify potential metabolic markers that could be monitored prior to disease manifestation [26]. Transcription factors (TFs) are a critically important regulatory layer that drives the expression of metabolic genes and, in turn, influences metabolism. Transcriptional regulatory networks of the brain have helped to identify candidate TFs interacting with metabolic genes and exploring the metabolic regulatory landscape in NDD [26]. In this review, we focus on the initial advances in genome-scale metabolic models, transcriptional regulatory networks (TRNs) and multiscale causal network models for the investigations of NDD, highlighting challenges and scope for future developments.

Genome-scale metabolic models to identify metabolic signatures in neurodegenerative diseases

Genome-scale metabolic models are widely used tools for systems-level metabolic studies and have been used to predict cellular behavior under diverse biological conditions and identify metabolic targets that can inform drug development efforts [23]. These models contain annotated gene-protein-reaction relationships for organisms and are used to predict metabolic fluxes (the rate of enzyme-mediated molecular turnover through a biological reaction) under diverse conditions. Some approaches include a mass balance accounting of molecules as a means to identify differences in metabolic flux between normal and diseased states. Metabolic models have been built for many organisms across the three domains of life: bacteria, archaea and eukarya [28,29]. To understand the role of different types of brain cells in NDDs, in silico metabolic models of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia along with multi-omics data have been used to recapitulate the metabolic interactions between these cell types during normal and pathologic states [30,31]. The cell type-specific models have shown promise by recapitulating observed physiological changes, and simulations show positive concordance with experimental studies [32].

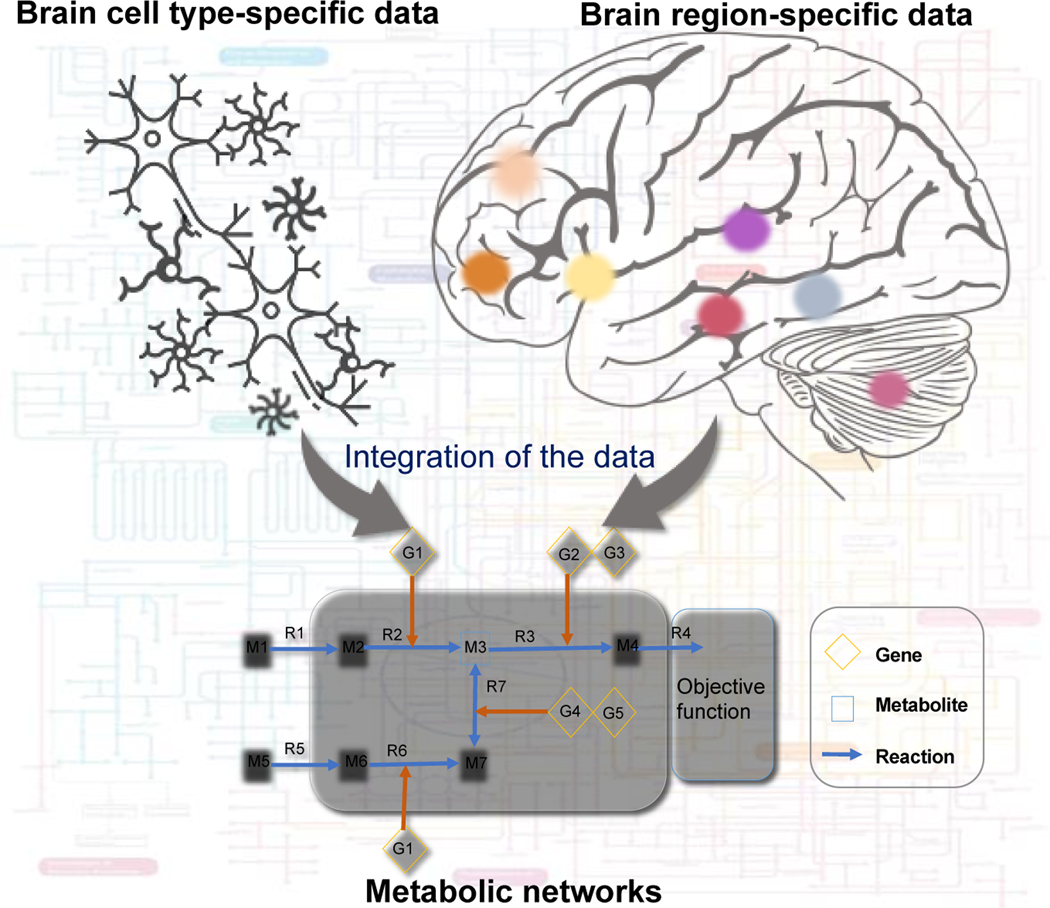

Astrocytes perform many functions in the brain, but primarily provide metabolic support for neurons [33]. The astrocyte metabolic model is a comprehensive representation of known metabolism, and it has been used to simulate the metabolic behavior of astrocytes under normal physiological and ischemia conditions [31]. Using brain cell-specific metabolic models, we can predict metabolic changes in different cell types, decipher metabolic coupling, synergistic activities, cellular interactions, and identify potential drug targets of drugs for NDDs [30]. A recent study used reconstructed brain region-specific metabolic networks to investigate the role of circulating bile acids that may contribute to AD, along with altered cholesterol metabolism [26]. Increasing evidence suggests a role for primary and secondary bile acids, the end-product of cholesterol metabolism as predictors of pathophysiology in AD and PD [26,34,35]. Brain region-specific metabolic networks [26] capture in silico metabolic changes and can potentially identify metabolic markers associated with these NDDs prior to disease manifestation, thus making them useful in interpreting the relevance of interactions and mechanisms between different classes of metabolites and NDD associated pathobiology. Figure 1 shows the application of cell- and tissue-specific metabolic models to understand the metabolic changes in NDD.

Figure 1:

A systems approach for investigating metabolic changes in the brain. Brain cell type-specific and region-specific data has been used to generate metabolic networks and identify metabolic dysregulation in NDDs.

Evaluation of peripheral lipidomic profiles can also offer a valuable perspective on metabolic dysregulation observed in preclinical and clinical AD states. Huynh et al [36] presented a comprehensive lipidomic analysis from plasma samples derived from two independent cross-sectional AD cohorts and reported dysregulation of lipid species including phosphatidylethanolamine and triglycerides that are also dysregulated in AD comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes [37] as well as ether lipids and GM3 gangliosides. This study demonstrated the critical importance of lipidomic profiling platforms that can differentiate between isomeric lipid species which demonstrate complex and heterogeneous associations with AD. Such profiling efforts also potentiate novel integrative opportunities to combine lipidomics with additional layers of multi-omics data collected on these same subjects to illuminate the genetic, epigenetic, transcriptomic, and proteomic context of these observed perturbations.

In order to better use these kinds of in silico models to interrogate NDDs, there is a critical need for longitudinal omics data and cell type-specific data (i.e. single cell RNA seq and metabolomics). To this end, the NIH and other funding agencies have created multiple consortiums to generate large, longitudinal omics datasets. These datasets take years to create, because of both cost and longitudinal nature, but are critical for providing a window into disease risk and progression. While many studies focus on the brain itself, there are also compelling data linking the gut-brain axis and transport of metabolites across the blood brain barrier (BBB) with physiological changes observed in NDD, especially in AD and PD [38]. In silico models of the gut microbiome have been successful in predicting the effect of diet, genetic predisposition and host-microbe interaction that may contribute to NDD [14,39].

Studying the metabolic regulatory landscape in NDD

With many of the loci identified in GWAS studies for NDDs found in non-coding regions enriched for eQTLs, there is an important need for understanding the role of transcriptional regulation of gene expression[40,41]. Transcription factors (TFs) play a key regulatory role in the expression of metabolic genes that encode enzymes [42]. Observed transcriptional changes and identified genetic associations with a disease generally converge on the same regulator TFs. For example, SREBF-1 and SREBF-2 are TFs that regulate lipid and cholesterol metabolism and their variants are associated with AD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorders and dementia risk [43–45]. A haplotype for the myeloid-specific transcription factor PU.1 (also known as SPI1) has been implicated in AD risk [46]. Genome-scale transcriptional regulatory network (TRN) models have been developed to predict TF-target gene interactions [47,48].

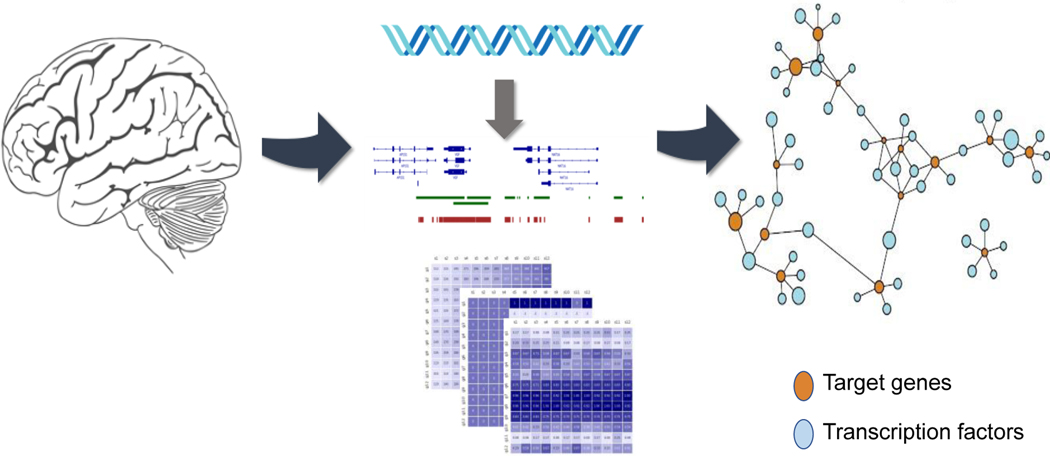

Using DNase footprinting data to help define gene regulatory regions, we constructed TRNs from multiple, independent post-mortem human brain RNA-seq cohorts, to help identify network differences that support a role for herpes viruses in AD [47]. In our aforementioned work looking at the metabolic differences in AD, the same brain TRNs associated TFs like SREBF2, PPARA, RXRG with bile acids and cholesterol metabolism genes previously implicated in AD [26]. Widespread transcriptional changes have been detected throughout the progression of HD, and these kinds of changes are amongst the earliest known phenotypes in HD mouse models [49]. Analysis using TRNs of mouse striatum followed by experimental validation identified SMAD3 as regulating HD-related gene expression with many of SMAD3 target genes found to be downregulated early in HD [49]. A genome-scale human brain has been used to identify key regulator TFs that are associated with both psychiatric disorders and NDDs [47]. Brain gene expression changes have also been studied for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorders, major depression disorder and autism [47]. This network-based approach identified key regulator TFs such as POU3F2, SOX2, NPAS3 and RFX4 that also harbor risk associated DNA variants for schizophrenia and bipolar disorders [47]. Figure 2 represents the generation of genome-scale TRN models for the identification of TFs in the brain.

Figure 2:

Genome-scale TRN model of brain. Brain-specific DNase footprinting data and comprehensive TF-gene co-expression datasets have been used for generating the TRN model for identifying TF-target genes implicated in NDDs.

Using cell type-specific data, it is feasible to generate TRN models for different brain cells [48]. Such models are broadly applicable to future genetic and genomic studies of human diseases and there is scope for their improvement over time as open chromatin data like ATAC-seq [50] and DNase-seq [51] becomes widely available. Integration of these data types will likely provide insights into how variants in non-coding regions convey risk or protection for various NDDs. Using systems approaches that model and integrate both metabolic and the regulatory landscape enable a mechanistic framework to understand the disease etiology of NDDs.

Multiscale causal network models of NDDs

The neurodegenerative patterns in NDDs and the observations of disease-perturbed functional networks indicate a causal relationship, but little is known about the primary pathogenic mechanisms in these diseases across their progression [52]. The information available in causal biological network databases such as PD map and NeuroMMSig have mainly focused on causal relationships between genes, proteins and other biological entities [53]. Using multi-omics datasets (genome, transcriptome, proteome, and/or metabolome) and clinical features of NDDs, multiscale causal networks have been constructed to identify novel critical genes and pathways important in NDD [53,54]. In one such study, probabilistic causal reasoning was employed on a dataset of late-onset AD individuals and controls to construct a predictive multiscale network model of AD that identified VGF as a key driver of AD pathophysiology [53]. Thus, using a priori knowledge of metabolic and transcriptional changes, causal networks can help in generating hypotheses around novel targets, and derive mechanistic insights furthering our understanding of NDDs.

Future perspectives

Systems biology is an important tool to advance neuroscience research, elucidate mechanisms of NDD pathology, and improve clinical outcomes for patients. Although this review focuses on network approaches to understand metabolic dysregulation in NDD, there are many other computational studies of the brain in health and NDD, including drug designing aimed to target multiple drug intervention points in NDDs as well as computational neurotoxicology [55,56]. Machine learning frameworks have been developed to evaluate associations between disease and any biological process that can be described by a set of genes, metabolites or proteins [57]. Increasingly sophisticated approaches that leverage heterogeneous multi-omic and clinical data types for patient subtype identification [58,59] and pseudotemporal trajectory mapping [60] in AD are also emerging. Such frameworks are expected to help accelerate the identification of predictive biomarkers that can improve early diagnosis, track disease progression and help prioritize candidate therapeutic strategies for further evaluation [59].

Summary

This review highlights the importance of in silico models such as genome-scale metabolic and regulatory networks in neuroscience research. We focused on the application of genome-scale metabolic networks of human brain and brain cells to identify alterations in NDD. We also described the importance of TRN models of the brain to identify key transcriptional regulators in HD, AD, and other psychiatric disorders. As the rapid generation of richly phenotyped, patient-derived multi-omic data continues apace, new and increasingly powerful in silico modelling opportunities will continue to emerge that can offer new glimpses into the earliest drivers of NDD. The reciprocal refinement and validation of in silico models with complementary multi-omics, and the exploitation of those models to prioritize the collection of additional molecular data can offer a powerful push-pull relationship that capitalizes on broad cross-disciplinary efforts and expertise within the NDD research community. Though challenging, the coordination of such efforts will be vital for building a cohesive multiscale understanding of NDD that is capable of spanning molecular and clinical domains, and will represent a valuable step towards the development of disease-modifying therapies for these devastating disorders.

Acknowledgements

P.B. acknowledges the support of 5U01AG061359-02 and 5U01AG061359-03 from NIA. C.F. acknowledges the support of R01AG062514, U01AG046139 from NIA. B.R acknowledges the support of U01AG061835, R21AG063068, RF1AG058469, RF1AG059319 from the NIA.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Cao X, Hou Y, Zhang X, Xu C, Jia P, Sun X, Sun L, Gao Y, Yang H, Cui Z, et al. : A comparative, correlate analysis and projection of global and regional life expectancy, healthy life expectancy, and their GAP: 1995–2025. J Glob Health 2020, 10:020407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators: Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2020, 396:1160–1203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2021 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement 2021, 17:327–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marras C, Beck JC, Bower JH, Roberts E, Ritz B, Ross GW, Abbott RD, Savica R, Van Den Eeden SK, Willis AW, et al. : Prevalence of Parkinson’s disease across North America. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2018, 4:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hou Y, Dan X, Babbar M, Wei Y, Hasselbalch SG, Croteau DL, Bohr VA: Ageing as a risk factor for neurodegenerative disease. Nature Reviews Neurology 2019, 15:565–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeve A, Simcox E, Turnbull D: Ageing and Parkinson’s disease: Why is advancing age the biggest risk factor? Ageing Research Reviews 2014, 14:19–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Esopenko C, Levine B: Aging, neurodegenerative disease, and traumatic brain injury: the role of neuroimaging. J Neurotrauma 2015, 32:209–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kumar A, Sidhu J, Goyal A, Tsao JW: Alzheimer Disease. In StatPearls. . StatPearls Publishing; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mahul-Mellier A-L, Burtscher J, Maharjan N, Weerens L, Croisier M, Kuttler F, Leleu M, Knott GW, Lashuel HA: The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply α-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117:4971–4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oosterloo M, de Greef BTA, Bijlsma EK, Durr A, Tabrizi SJ, Estevez-Fraga C, de Die-Smulders CEM, Roos RAC: Disease Onset in Huntington’s Disease: When Is the Conversion? Mov Disord Clin Pract 2021, 8:352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mattson MP, Arumugam TV: Hallmarks of Brain Aging: Adaptive and Pathological Modification by Metabolic States. Cell Metab 2018, 27:1176–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makhouri FR, Ghasemi JB: In Silico Studies in Drug Research Against Neurodegenerative Diseases. Curr Neuropharmacol 2018, 16:664–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ganesana M, Lee ST, Wang Y, Venton BJ: Analytical Techniques in Neuroscience: Recent Advances in Imaging, Separation, and Electrochemical Methods. Anal Chem 2017, 89:314–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rosario D, Boren J, Uhlen M, Proctor G, Aarsland D, Mardinoglu A, Shoaie S: Systems Biology Approaches to Understand the Host-Microbiome Interactions in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Neurosci 2020, 14:716. * This review highlights the potential of genome-scale metabolic models to understand the microbial and host-microbe interactions that contribute to development of the disease or its prevention. They focus on the effect of diet and describe modulation of gut microbiota in NDDs.

- 15.Ambrosini YM, Borcherding D, Kanthasamy A, Kim HJ, Willette AA, Jergens A, Allenspach K, Mochel JP: The Gut-Brain Axis in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Relevance of the Canine Model: A Review. Front Aging Neurosci 2019, 11:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rodriguez S, Hug C, Todorov P, Moret N, Boswell SA, Evans K, Zhou G, Johnson NT, Hyman BT, Sorger PK, et al. : Machine learning identifies candidates for drug repurposing in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature Communications 2021, 12. * This research article presented a machine learning framework that quantified association between early, mid or late stages of AD and any biological process that can be characterized by a list of gene names.

- 17.Fusco FR, Paldino E: Promising Candidates for Drug Repurposing in Huntington’s Disease. Drug Repositioning 2017, doi: 10.4324/9781315373669-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhao K, So H-C: Using Drug Expression Profiles and Machine Learning Approach for Drug Repurposing. Methods in Molecular Biology 2019, doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8955-3_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sweeney MD, Sagare AP, Zlokovic BV: Blood-brain barrier breakdown in Alzheimer disease and other neurodegenerative disorders. Nat Rev Neurol 2018, 14:133–150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jha SK, Jha NK, Kumar D, Ambasta RK, Kumar P: Linking mitochondrial dysfunction, metabolic syndrome and stress signaling in Neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017, 1863:1132–1146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Picard M, McManus MJ: Mitochondrial Signaling and Neurodegeneration. Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disorders 2016, doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-28637-2_5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reeve AK, Krishnan KJ, Duchen MR, Turnbull DM: Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Neurodegenerative Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gu C, Kim GB, Kim WJ, Kim HU, Lee SY: Current status and applications of genome-scale metabolic models. Genome Biology 2019, 20. * This review article provides a comprehensive description of the advances in the reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models attributed to automatic GEM reconstruction tools. The review also describes the application of GEMs in understanding human diseases.

- 24.Ramon C, Gollub MG, Stelling J: Integrating –omics data into genome-scale metabolic network models: principles and challenges. Essays in Biochemistry 2018, 62:563–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heirendt L, Arreckx S, Pfau T, Mendoza SN, Richelle A, Heinken A, Haraldsdóttir HS, Wachowiak J, Keating SM, Vlasov V, et al. : Creation and analysis of biochemical constraint-based models using the COBRA Toolbox v.3.0. Nat Protoc 2019, 14:639–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Baloni P, Funk CC, Yan J, Yurkovich JT, Kueider-Paisley A, Nho K, Heinken A, Jia W, Mahmoudiandehkordi S, Louie G, et al. : Metabolic Network Analysis Reveals Altered Bile Acid Synthesis and Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease. Cell Rep Med 2020, 1:100138. ** This is the first study on human brain region-specific metabolic networks constructed from post-mortem brain data. The study focused on the understanding the role of altered cholesterol and bile acid pathway in Alzheimer’s disease.

- 27.Wang Y, Eddy JA, Price ND: Reconstruction of genome-scale metabolic models for 126 human tissues using mCADRE. BMC Syst Biol 2012, 6:153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulz C, Almaas E: Genome-scale reconstructions to assess metabolic phylogeny and organism clustering. PLoS One 2020, 15:e0240953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correia K, Mahadevan R: Pan-genome-scale network reconstruction: a framework to increase the quantity and quality of metabolic network reconstructions throughout the tree of life. [date unknown], doi: 10.1101/412593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lewis NE, Schramm G, Bordbar A, Schellenberger J, Andersen MP, Cheng JK, Patel N, Yee A, Lewis RA, Eils R, et al. : Large-scale in silico modeling of metabolic interactions between cell types in the human brain. Nat Biotechnol 2010, 28:1279–1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martín-Jiménez CA, Salazar-Barreto D, Barreto GE, González J: Genome-Scale Reconstruction of the Human Astrocyte Metabolic Network. Front Aging Neurosci 2017, 9:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richelle A, Chiang AWT, Kuo C-C, Lewis NE: Increasing consensus of context-specific metabolic models by integrating data-inferred cell functions. PLoS Comput Biol 2019, 15:e1006867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.García-Cáceres C, Balland E, Prevot V, Luquet S, Woods SC, Koch M, Horvath TL, Yi C-X, Chowen JA, Verkhratsky A, et al. : Role of astrocytes, microglia, and tanycytes in brain control of systemic metabolism. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22:7–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hertel J, Harms AC, Heinken A, Baldini F, Thinnes CC, Glaab E, Vasco DA, Pietzner M, Stewart ID, Wareham NJ, et al. : Integrated Analyses of Microbiome and Longitudinal Metabolome Data Reveal Microbial-Host Interactions on Sulfur Metabolism in Parkinson’s Disease. Cell Rep 2019, 29:1767–1777.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. MahmoudianDehkordi S, Arnold M, Nho K, Ahmad S, Jia W, Xie G, Louie G, Kueider-Paisley A, Moseley MA, Thompson JW, et al. : Altered bile acid profile associates with cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease-An emerging role for gut microbiome. Alzheimers Dement 2019, 15:76–92. ** This was one of the first studies to report the association between altered bile acid profile and genetic variants implicated in AD with cognitive impairment in AD. They showed the ratio of secondary to primary bile acids are strongly associated with cognitive decline.

- 36. Huynh K, Lim WLF, Giles C, Jayawardana KS, Salim A, Mellett NA, Smith AAT, Olshansky G, Drew BG, Chatterjee P, et al. : Concordant peripheral lipidome signatures in two large clinical studies of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 2020, 11:5698. * This study used lipidomics approach on ADNI and AIBL cohorts to identify lipid signatures that are associated with AD risk.

- 37.Meikle PJ, Wong G, Barlow CK, Weir JM, Greeve MA, MacIntosh GL, Almasy L, Comuzzie AG, Mahaney MC, Kowalczyk A, et al. : Plasma lipid profiling shows similar associations with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes. PLoS One 2013, 8:e74341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parker A, Fonseca S, Carding SR: Gut microbes and metabolites as modulators of blood-brain barrier integrity and brain health. Gut Microbes 2020, 11:135–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Baldini F, Hertel J, Sandt E, Thinnes CC, Neuberger-Castillo L, Pavelka L, Betsou F, Krüger R, Thiele I: Parkinson’s disease-associated alterations of the gut microbiome predict disease-relevant changes in metabolic functions. BMC Biol 2020, 18:1–21. * This research article highlighted the use of personalized metabolic modeling to predict the potential secretion for 129 microbial metabolites. Their approach identified microbial species that changes significantly in their relative abundances in PD patients and could describe PD-associated microbial patterns.

- 40. Podleśny-Drabiniok A, Marcora E, Goate AM: Microglial Phagocytosis: A Disease-Associated Process Emerging from Alzheimer’s Disease Genetics. Trends Neurosci 2020, 43:965–979. * This review article discusses the AD risk genes identified from GWAS studies and the impact of AD risk variants on microglial functions specifically phagocytosis and debris processing in the system.

- 41.Wightman DP, Jansen IE, Savage JE, Shadrin AA, Bahrami S, Rongve A, Børte S, Winsvold BS, Drange OK, Martinsen AE, et al. : Largest GWAS (N=1,126,563) of Alzheimer’s Disease Implicates Microglia and Immune Cells. medRxiv 2020, [Google Scholar]

- 42.van der Knaap JA, Verrijzer CP: Undercover: gene control by metabolites and metabolic enzymes. Genes Dev 2016, 30:2345–2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poletti S, Aggio V, Bollettini I, Falini A, Colombo C, Benedetti F: SREBF-2 polymorphism influences white matter microstructure in bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging 2016, 257:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Le Hellard S, Mühleisen TW, Djurovic S, Fernø J, Ouriaghi Z, Mattheisen M, Vasilescu C, Raeder MB, Hansen T, Strohmaier J, et al. : Polymorphisms in SREBF1 and SREBF2, two antipsychotic-activated transcription factors controlling cellular lipogenesis, are associated with schizophrenia in German and Scandinavian samples. Mol Psychiatry 2008, 15:463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds CA, Hong M-G, Eriksson UK, Blennow K, Wiklund F, Johansson B, Malmberg B, Berg S, Alexeyenko A, Grönberg H, et al. : Analysis of lipid pathway genes indicates association of sequence variation near SREBF1/TOM1L2/ATPAF2 with dementia risk. Hum Mol Genet 2010, 19:2068–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huang K-L, Marcora E, Pimenova AA, Di Narzo AF, Kapoor M, Jin SC, Harari O, Bertelsen S, Fairfax BP, Czajkowski J, et al. : A common haplotype lowers PU.1 expression in myeloid cells and delays onset of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 2017, 20:1052–1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Pearl JR, Colantuoni C, Bergey DE, Funk CC, Shannon P, Basu B, Casella AM, Oshone RT, Hood L, Price ND, et al. : Genome-Scale Transcriptional Regulatory Network Models of Psychiatric and Neurodegenerative Disorders. Cell Syst 2019, 8:122–135.e7. * This research article discusses the key regulator transcription factors in psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases using a transcriptional regulatory network (TRN) model for the human brain. They experimentally validated the network prediction that links POU3F2 (a TF) to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder

- 48. Funk CC, Casella AM, Jung S, Richards MA, Rodriguez A, Shannon P, Donovan-Maiye R, Heavner B, Chard K, Xiao Y, et al. : Atlas of Transcription Factor Binding Sites from ENCODE DNase Hypersensitivity Data across 27 Tissue Types. Cell Rep 2020, 32:108029. ** This article provides the details of analyzing data from the ENCODE consortium on DNase-seq experiments to create a resource of footprints in 27 human tissues. The authors were able to predict the genomic occupancy of >1500 human TFs in these tissues.

- 49.Ament SA, Pearl JR, Cantle JP, Bragg RM, Skene PJ, Coffey SR, Bergey DE, Wheeler VC, MacDonald ME, Baliga NS, et al. : Transcriptional regulatory networks underlying gene expression changes in Huntington’s disease. Molecular Systems Biology 2018, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bryois J, Garrett ME, Song L, Safi A, Giusti-Rodriguez P, Johnson GD, Shieh AW, Buil A, Fullard JF, Roussos P, et al. : Evaluation of chromatin accessibility in prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Commun 2018, 9:3121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fullard JF, Hauberg ME, Bendl J, Egervari G, Cirnaru M-D, Reach SM, Motl J, Ehrlich ME, Hurd YL, Roussos P: An atlas of chromatin accessibility in the adult human brain. Genome Res 2018, 28:1243–1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Drzezga A: The Network Degeneration Hypothesis: Spread of Neurodegenerative Patterns Along Neuronal Brain Networks. J Nucl Med 2018, 59:1645–1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Beckmann ND, Lin W-J, Wang M, Cohain AT, Charney AW, Wang P, Ma W, Wang Y-C, Jiang C, Audrain M, et al. : Multiscale causal networks identify VGF as a key regulator of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Commun 2020, 11:1–19. ** This research article discusses the data-driven construction of causal network models of AD. The models can be used to identify components and key regulators associated with AD.

- 54.Karki R, Kodamullil AT, Hoyt CT, Hofmann-Apitius M: Quantifying mechanisms in neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) using candidate mechanism perturbation amplitude (CMPA) algorithm. BMC Bioinformatics 2019, 20:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morales-Navarro S, Prent-Peñaloza L, Rodríguez Núñez YA, Sánchez-Aros L, Forero-Doria O, González W, Campilllo NE, Reyes-Parada M, Martínez A, Ramírez D: Theoretical and Experimental Approaches Aimed at Drug Design Targeting Neurodegenerative Diseases. Processes 2019, 7:940. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Linne M-L: Neuroinformatics and Computational Modelling as Complementary Tools for Neurotoxicology Studies . Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2018, 123 Suppl 5:56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vamathevan J, Clark D, Czodrowski P, Dunham I, Ferran E, Lee G, Li B, Madabhushi A, Shah P, Spitzer M, et al. : Applications of machine learning in drug discovery and development. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18:463–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Neff RA, Wang M, Vatansever S, Guo L, Ming C, Wang Q, Wang E, Horgusluoglu-Moloch E, Song W-M, Li A, et al. : Molecular subtyping of Alzheimer’s disease using RNA sequencing data reveals novel mechanisms and targets. Sci Adv 2021, 7. * This study provides details of molecular subtypes of AD that were identified using an integrative network approach. The Multiscale network analysis shown in the article revealed subtype-specific drivers of AD.

- 59.Vogel JW, Young AL, Oxtoby NP, Smith R, Ossenkoppele R, Strandberg OT, La Joie R, Aksman LM, Grothe MJ, Iturria-Medina Y, et al. : Four distinct trajectories of tau deposition identified in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Med 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01309-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mukherjee S, Heath L, Preuss C, Jayadev S, Garden GA, Greenwood AK, Sieberts SK, De Jager PL, Ertekin-Taner N, Carter GW, et al. : Molecular estimation of neurodegeneration pseudotime in older brains. Nat Commun 2020, 11:5781. * This study investigated the temporal molecular changes that lead to disease onset and progression. Using the postmortem bulk RNA-seq data they could infer the AD severity and disease subtypes as well as disease progression.