Abstract

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) is a chemical commonly used as a plasticizer to render polyvinyl chloride products more durable and flexible. Although exposure to DEHP has raised many health concerns due to the identification of DEHP as an endocrine disruptor, it is still used in consumer products, including polyvinyl chloride plastics, medical tubing, car interiors, and children’s toys. To investigate the impact of early life exposure to DEHP on the ovary and testes, newborn piglets were orally dosed with DEHP (20 or 200 mg/kg/day) or vehicle control (tocopherol-stripped corn oil) for 21 days. Following treatment, ovaries, testes, and sera were harvested for histological assessment and measurement of steroid hormone levels. In male piglets, progesterone and pregnenolone levels were significantly lower in both treatment groups compared to control, whereas in female piglets, progesterone was significantly higher in the 20 mg group compared to control, indicating sex-specific effects in a non-monotonic manner. Follicle numbers and gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes and apoptotic factors were not altered in treated ovaries compared to controls. In DEHP-treated testes, germ cell migration was impaired and germ cell death was significantly increased compared to controls. Overall, the results of this study suggest that neonatal exposure to DEHP in pigs leads to sex-specific disruption of the reproductive system.

Keywords: Pigs, phthalates, steroidogenesis, endocrine disruption

I. Introduction

Phthalates are a family of chemical compounds composed of ortho esters of phthalic acid. One of the most commonly used phthalates is di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), which is used as a plasticizer to improve durability, flexibility, and appearance of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plastics. DEHP is found in many everyday products, including food packaging, car interiors, building supplies, and children’s toys [1]. It can also be found in medical equipment, including fluid bags, administrative tubing, catheters, masks, and surgical gloves. Hundreds of millions of pounds of DEHP are used for plastic production in the US every year, despite numerous studies reporting endocrine disrupting properties [2–4].

DEHP has been shown to have harmful effects in both male and female mammals, particularly on the reproductive system [5]. In humans, DEHP exposure is associated with decreased anogenital distance and altered semen parameters in males and altered timing of puberty and preterm birth in females [2,3]. In rodents, DEHP exposure disrupts steroidogenesis [6,7] and induces premature reproductive senescence in both sexes [8,9].

One of the most highly exposed human populations is infants in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), who require use of many medical devices containing DEHP-containing PVC plastics. Biomonitoring studies of NICU infants indicate that exposure levels can reach 2–3 orders of magnitude higher than average human exposure, into the mg/kg range [10,11]. Although most developmental studies focus on prenatal exposure, limited studies in rodents indicate that postnatal exposure to DEHP also impacts health, suggesting that additional studies on early postnatal exposure to DEHP and other phthalates are needed [12–15]. The developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis, which posits that early life exposures during sensitive periods of development can results in later life disease, further underscores the importance of postnatal as well as prenatal phthalate exposure studies [16].

Due to their handleability, affordability, and shorter life spans, mice are commonly used for reproductive toxicology studies. Although the reproductive systems of mice and humans are similar, animal models such as pigs are robust and more physiologically and biochemically relevant to humans [17]. In female development, a major difference between rodents and humans is the formation of the primordial follicle pool, which occurs postnatally in rodents and prenatally in humans and pigs [18,19]. Thus, pigs are a better model of human female postnatal development than rodents. In addition porcine gonads are highly sensitive to endocrine disrupting chemicals, with most documented effects related to steroidogenesis [17].

Based on extensive evidence of the endocrine disrupting activity of DEHP in rodents, pigs represent an appropriate next step for human translational studies. Thus, this manuscript describes a pilot study on the impact of neonatal exposure to DEHP on the reproductive systems of male and female piglets. As the early postnatal period is a key time of gonadal organization, indicators of cell migration, growth, and death were analyzed histologically. Serum sex steroid hormone levels were measured in both sexes. Additional gene expression analysis of steroidogenic enzymes and apoptosis regulators were performed in ovarian tissue. This study tested the hypothesis that early life exposure to DEHP disrupts development in both sexes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

Piglets were obtained from the University of Illinois Swine Research Center and were transferred to the AAALAC-approved animal facilities in the Edward R. Madigan Laboratory on the University of Illinois campus where they were housed throughout the study. The piglets were offspring of L359 boars mated to Camborough females (Pig Improvement Company, Hendersonville, TN). Per standard agricultural protocol, pigs were administered an intramuscular injection of iron hydrogenated dextran (1 mL, Butler Schein Animal Health, Dublin, OH, USA) and a prophylactic antibiotic (0.3 mL of ceftiofur crystalline free acid, Exceed, Zoetis, Parsippany, NJ, USA) within 24 h of birth. Piglets had access to their mother’s colostrum for 48 hours after birth. To balance initial weight and sex, piglets were randomized to one of three dietary treatments described below and were housed individually in specialized neonatal piglet cages within environmentally controlled rooms (27 °C) with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Additional heat was provided with heating pads and space heaters. All animal and experimental procedures were in accordance with the National Research Council Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and approved by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol # 18112).

2.2. Study Design

Piglets were randomly assigned to receive DEHP at the concentrations of 0, 20, or 200 mg/kg body weight (BW) (N = 8 per dietary treatment, four per sex). DEHP (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in tocopherol-stripped corn oil and added to the feeding bowl prior to the first feeding of the day from study day (SD) 1–21, beginning on the third day of life. Piglets were fed a nutritionally adequate sow-milk replacer (LiquiWean, Milk Specialties, Eden Prairie, MN) reconstituted at 18.3% weight/volume. Piglet body weight was measured daily and the volume of formula provided was calculated based on BW at 300 mL and 325 mL/kg BW/d from study days 1–5 and 6–21, respectively.

The doses of 20 and 200 mg/kg of DEHP were chosen for comparison to previous studies of DEHP in rodents and to represent estimated exposure of NICU infants [10,11,20]. The dosing window was selected because it is a sensitive period of development [21]. In postnatal male mammals, germ cells are migrating, multiplying, and dying, whereas in females, primordial follicles are beginning the first stages of folliculogenesis [22,23].

2.3. Sample Collection

On study day 21, animals were sedated with an intramuscular injection of Telazol® (Tiletamine HCl and Zolazepam HCl, 3.5mg/kg BW each, Pfizer Animal Health, Fort Dodge, IA) and blood was collected via cardiac puncture for serum hormone analysis. Piglets were then euthanized by an intravenous injection of 86 mg/kg BW sodium pentobarbital (Euthasol, Virbac AH, Inc., Fort Worth, TX). Ovaries were aseptically removed, weighed, and placed in Dietrich’s fixative or frozen at −80°C. Testes and epididymis were removed, weighed, fixed in Bouin’s solution (Ricca Chemical Co., Arlington, TX) for 24 hours, and then transferred to 70% ethyl alcohol until processing.

2.4. Analysis of Sex Steroid Hormone Levels

Sera were separated by centrifugation at 2,200 g for 20 minutes at 4°C in a benchtop centrifuge (CS-6R Centrifuge, Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Indianapolis, IN). Sera levels of testosterone, progesterone, estrone, pregnenolone, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and 17β-estradiol were measured by enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; DRG Instruments, Germany) following manufacturer’s protocols and performed in duplicates. The detection ranges were 0.0083–16 ng/mL for testosterone, 0–40 ng/mL for progesterone, 10.6 pg/mL–2000 pg/mL for 17β-estradiol, 8.1–2400 pg/mL for estrone, 0.05–25.6 ng/mL for pregnenolone, and 0.07–30 ng/mL for DHEA. Intra-assay coefficients of variation were <11% for all hormones except estradiol, for which the inter-assay coefficient of variation was 23% despite repetition.

2.5. Histological Evaluation of Follicle Numbers

Fixed ovaries were placed in paraffin blocks and serially sectioned at 8 μm, mounted on glass slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and covered with a glass coverslip using a xylene:perform racemic mixture. The stained slides were cured for at least 24 hours before digital scanning with a Hamamatsu NanoZoomer 2.0 HT (scanner model C9600-12) using NDP.scan 3.2.15. The 20X objective was used to capture images, which were then scaled up 40X magnification using NDP.view 2.7.25. The scanning areas or sections were defined by the user. Once the scanning areas were defined, either automatic or manual focus areas were chosen on each section and slide. Automatic focus settings were used for large sections, whereas manual focus settings were used for small sections. For manual settings, 4 to 5 focus areas were defined per ovary section. To ensure overall representation and uniformity, all follicles in the ovary section were scanned at multiple layers, specifically using z-stacks of each ovary section at every 2-micron thickness. The images were then viewed on NDP.view 2.7.25 and exported as JPEG images. Follicles were quantified using the ImageJ cell counter plugin.

Every 20th section of the ovary was used to count the number of germ cells, primordial follicles, primary follicles, preantral follicles, and abnormal follicles as previously described [19,24,25]. Briefly, germ cells were identified as round in appearance with a nucleus and found in clusters or nests. Primordial follicles were identified as follicles with an oocyte, surrounded by a single layer of squamous granulosa cells. Primary follicles consisted of an oocyte, surrounded by a single layer of cuboidal granulosa cells. Preantral follicles contained an oocyte surrounded by multiple layers of cuboidal granulosa cells and by theca cells. Abnormal follicles consisted of multi-oocyte follicles or follicles that were clustered together and did not have proper granulosa/theca cell allocation between follicles (Figure S1).

2.6. Gene expression analysis

qPCR analyses for gene expression were performed on collected ovaries (n = 4 animals per treatment group). Ovaries were snap frozen and stored at −80°C until RNA extraction. RNA was isolated using a RNeasy Mini Kit (catalog no. 74004, Qiagen, Inc., Valencia, CA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA was eluted in RNase-free water and the concentration was determined using a NanoDrop (λ = 260 nm; ND 1000; Nanodrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, DE). Total RNA (400 ng) was reverse transcribed to complementary DNA using the iScript RT kit (catalog no. 1708890, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Analysis of qPCR was conducted using the CFX96 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) and gene expression was calculated with CFX Manager Software according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Porcine-specific qPCR primers (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, Iowa) for the genes investigated (Guanine nucleotide-binding protein subunit beta-2-like 1 (GNB2L1), B cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (BCL2), Bh3-interacting domain death agonist (BID), Bcl2-related ovarian killer (BOK), cytochrome P450 11A1 (CYP11A1), cytochrome P450 17A1 (CYP17A1), cytochrome P450 19A1 (CYP19A1), 17-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (HSD17B1), 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 1 (HSD3B1), and steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR)) are listed in Table S1. PCR reactions were performed with 6.67 ng complementary DNA, forward and reverse primers (7.5 pmol each), and SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix for a reaction volume of 10 μL. The qPCR program consisted of an enzyme activation step (95 °C for 1 min), an amplification and quantification program (36 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 10 s, 72°C for 10 s, and a single fluorescence reading), a melt curve (65–95°C heating, 0.5°C/sec with continuous fluorescence readings), and a final step at 72°C for 5 min per the manufacturer’s protocol. All gene expression data were normalized to the housekeeper GNB2L1 [26]. Relative fold changes were calculated as the ratio to control group level and were analyzed using the Pfaffl model for relative quantification of real-time PCR data [33].

2.7. Testicular Histopathology

Fixed testes were processed using an automated tissue processor (Miles Scientific Tissue Tek VIP 2000) and embedded into paraffin blocks. The tissues were sectioned at 7 μm thickness, stained with hematoxylin and eosin, and examined using light microscopy (Olympus BX 51). The number of gonocytes cell in the lumen of somniferous tubule was counted and represented as the average number of the gonocytes per tubule.

2.8. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) analysis

Testes were examined to determine the degree of cell apoptosis. Apoptotic assay was performed by using ApopTag Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Detection Kit S7100 (Millipore) with diaminobenzidine and hematoxylin according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The frequency of apoptotic cells within seminiferous tubules was expressed as the average number of apoptotic cells (brown nuclei) within 20 seminiferous tubules.

2.9. Statistical Analyses

Data were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Data were analyzed by comparing treatment groups to control using IBM SPSS version 26 software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Outliers were removed by the Grubb’s test using GraphPad outlier calculator software (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA). All data were continuous and assessed for normal distribution by Shapiro-Wilk analysis. If data met assumptions of normal distribution and homogeneity of variance, data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey HSD or Dunnett 2-sided post-hoc comparisons. However, if data met assumptions of normal distributions, but not homogeneity of variance, data were analyzed by ANOVA followed by Games-Howell or Dunnett’s T3 post-hoc comparisons. If data were not normally distributed, the independent sample Kruskal-Wallis H followed by Mann-Whitney U non-parametric tests were performed. For all comparisons, statistical significance was determined by p-value ≤ 0.05. If p-values were greater than 0.05, but less than 0.10, data were considered to exhibit a trend towards significance.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on body weight and organ weights

Neonatal exposure of DEHP did not significantly alter body, epididymes, or testes weights in male piglets at SD21 (equivalent to postnatal day 23) compared to controls (Figure S2). In female piglets, body, ovary, and uterus weight were also not significantly different than controls (Figure S3). No significant differences were observed when organ weights were normalized to body weight (Figures S2 and S3).

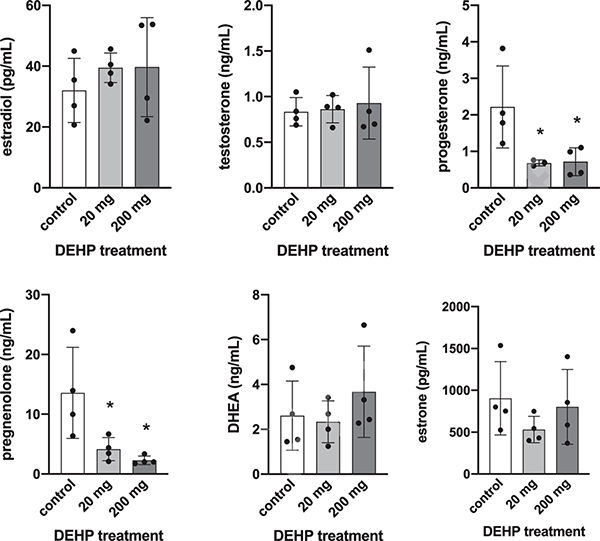

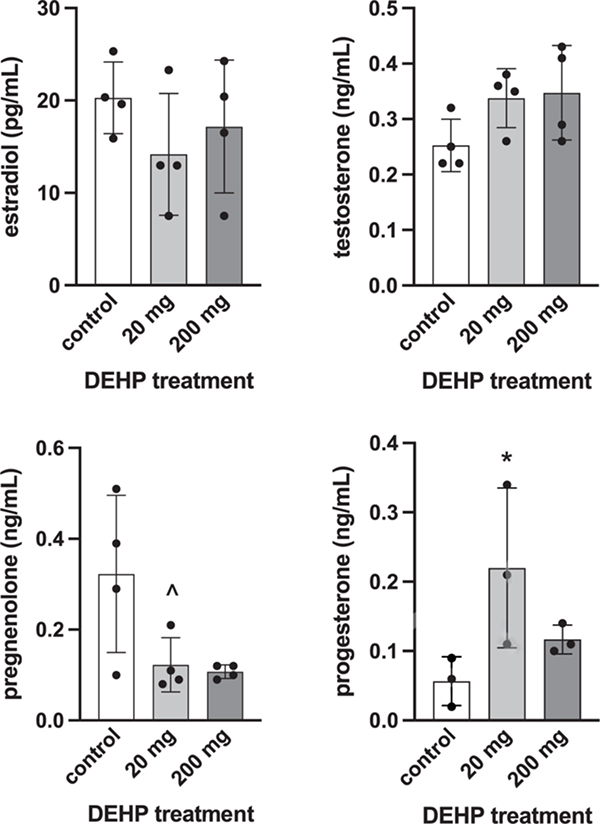

3.2. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on serum sex steroid hormone levels

Serum levels of sex steroid hormones were altered in male and female piglets at SD21 following neonatal exposure to DEHP. In male piglets, serum levels of progesterone and pregnenolone were significantly lower in the 20 mg (p = 0.044 and 0.03, respectively) and 200 mg groups (p = 0.035 and 0.012, respectively) compared to control (Figure 1). In female piglets, progesterone was significantly higher in the 20 mg group compared to control (p = 0.05) and pregnenolone was trending towards a lower level in the 20 mg group compared to control (p = 0.083, Figure 2).

Figure 1:

Effects of neonatal exposure to DEHP on serum sex steroid hormone levels at SD21 in male piglets. Sera were subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 2:

Effects of neonatal exposure to DEHP on serum sex steroid hormone levels at SD21 in female piglets. Sera were subjected to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Estrone and DHEA values were below the limit of detection (data not shown). Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from the control (p ≤ 0.05) and (^) indicates marginally nonsignificant differences (0.05 < p ≤ 0.10).

3.3. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on steroidogenic enzymes and apoptosis regulators

Gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes and apoptosis regulating genes in ovaries from female piglets identified no significant changes in the 20 or 200 mg groups compared to control. The expression of STAR tended to be lower in the 200 mg group compared to control (p = 0.068, Figure 3).

Figure 3:

Effects of neonatal exposure to DEHP on steroidogenic enzyme and apoptosis regulator gene expression changes at SD21 in female piglet ovaries. All gene expression is relative to the housekeeping gene, GNB2L1. Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. ^ indicates difference trending towards significance (0.05 < p ≤ 0.10).

3.4. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on folliculogenesis

DEHP treatment did not alter the number of germ cells, primordial follicles, primary follicles, preantral follicles, or abnormal follicles in the ovaries of female piglets compared to controls (Figure 4). The percent of each follicle type, which normalizes the data to the size of the ovary, was also not different from controls (Figure 4).

Figure 4:

Effect of neonatal exposure of DEHP on total follicle numbers (A) and percentages (B) of follicle types at SD21 in piglets. Ovaries were subjected to histological evaluation of follicle numbers. Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (p ≤ 0.05).

3.5. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on testicular development

In male piglets exposed to DEHP, migration of germ cells towards the basal lamina of the seminiferous tubules was impaired compared to controls (Figure 5). In treated animals, numerous germ cells were visible in the center of the seminiferous tubules in histological cross sections, whereas control animals showed few centralized germ cells (arrows, Figure 5B). Significantly higher numbers of germ cells were counted in the 20 mg (p = 0.001) and 200 mg (p = 0.002) treatment groups compared to control.

Figure 5:

Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on testicular gonocyte maturation. Representative images of testes from each treatment group at 10 X magnification (A) and 20 X magnification (B). Arrows indicate gonocyte cells in the lumen of seminiferous tubules in the DEHP treated testes, n = 3–4 per treatment group. The number of gonocytes in the lumen was counted for all treatment groups (C). Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. Asterisks (*) indicate significant differences from the control (p ≤ 0.05).

3.6. Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on testicular germ cell death

In the testes of male piglets exposed to 20 and 200 mg of DEHP, significantly higher numbers and percent of apoptotic germ cells were counted in seminiferous tubules treated with 20 mg (p = 0.001 for both number and percent) and 200 mg (p = 0.003 and 0.002, respectively) compared to control (Figure 6). In addition, the number and percent of apoptotic cells were significantly higher in the 20 mg group compared to the 200 mg group (p = 0.001 and p = 0.009, respectively, Figure 6).

Figure 6:

Effects of neonatal DEHP exposure on the testicular cell death at SD21. Representative images of TUNEL stained testes of each treatment group examined at 20X magnification (A). Arrows indicate areas of stained cells. The number of apoptotic cells per 20 seminiferous tubules (B) and percent of apoptotic cells per tubule (C) were counted for all treatment groups. Graphs represent means ± SEM from 3–4 animals per treatment group. Asterisks (* and **) indicate that each treatment group is significantly different from the others (p ≤ 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, 2-day-old piglets were orally dosed with DEHP for 21 days and assessed for developmental and endocrine disruption to test the hypothesis that early life exposure to DEHP disrupts steroidogenesis and germ cell function in neonatal piglets. Previously, we have investigated developmental and endocrine disruption by DEHP and other phthalates in in vitro and rodent models [9,27–35]. This study in pigs builds upon previous work to improve the human physiological relevance of evidence on the endocrine disrupting properties of DEHP in early postnatal life, a critical period of development for the reproductive system and a window of high DEHP exposure for hospitalized human infants.

Serum hormone levels were disrupted in DEHP-exposed piglets of both sexes. Previous studies of endocrine disrupting chemicals in porcine models have identified steroidogenesis as highly sensitive to disruption. Methoxychlor and dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene decreased progesterone synthesis in cultured porcine granulosa cells [36]. Polybrominated diphenyl ether flame retardants increased ovarian testosterone production and altered expression and activity of steroidogenic enzymes in cultured porcine follicles [37]. Perfluorooctane sulfonate and perfluorooctanoic acid have also been shown to disrupt porcine ovarian steroidogenesis [38]. In male boars, prepubertal exposure to DEHP increased testosterone levels and altered Leydig cell morphology [39]. In this study, DEHP exposure resulted in decreased pregenolone levels in both males and females compared to control, whereas progesterone was increased in females and decreased in males compared to control. Gene expression of steroidogenic enzymes was investigated in female piglets, but no significant differences were observed in treated animals compared to control. Future experiments will examine steroidogenic gene expression in males. The lack of gene expression changes in females may indicate that other pathways were disrupted, such as hormone metabolizing enzymes outside of the ovary, or that the sample size was too small to detect differences, as suggested by the trending decrease in expression in Star expression.

The proliferation and migration of male germ cells (gonocytes) towards the seminiferous tubule basal lamina was assessed histologically. The migration of gonocytes during early life and subsequent proliferation is required for cell survival and development into spermatogonia during spermatogenesis [23]. Phthalates, including dibutyl phthalate (DBP) and DEHP, are well-characterized testicular toxicants, especially in young rats [40]. Phthalates have been shown to target Sertoli cells, leading to decreased adhesion between germ cells and Sertoli cells [40,41]. In this study, male piglets exposed to DEHP showed impaired germ cell migration, with gonocytes visible in the centers of the seminiferous tubules of the treated groups. Germ cells must past through the tight junctions of the Sertoli cells to reach the basal lamina; thus, these results suggest that germ cell-Sertoli cell interactions may be disrupted in exposed piglets, consistent with previous studies in rodents. In addition, gonocytes without proper Sertoli cell interactions are more susceptible to apoptosis [40]. In DEHP-exposed male piglets, there was a statistically significantly higher number of apoptotic cells visible in TUNEL-stained seminiferous tubule cross sections compared to unexposed animals. In previous studies, DBP has been shown to induce the formation of multinucleated gonocytes in male rats, but no multinucleated gonocytes were observed in this study [42].

Sex differences were observed with respect to progesterone levels, with DEHP causing opposite effects in males and females. Research on animals of both sexes that considers sex as a biological variable is a special priority of the NIH, as biomedical research has historically defaulted to males [43,44]. As this study demonstrates, environmental chemicals such as phthalates can have different effects on each sex that would not be noticeable if the sexes were analyzed together or only one was studied. Additionally, non-monotonic dose response curves, a hallmark of endocrine disrupting chemicals, were observed in both sexes [45]. Progesterone was increased in females in the 20 mg group only. In the analysis of apoptotic cells in seminiferous tubules, significantly higher numbers of stained cells were observed in the 20 mg group compared to the 200 mg group, suggesting an inverted-U shaped dose response curve.

Although this was a pilot study with a small sample size, statistically significant effects of phthalate exposure on neonatal piglet hormone levels were observed. The small sample size combined with high variability in some results may have also resulted in Type II errors and misleading results. The use of piglets as a complex model that is more physiologically relevant to humans is a major strength of this study. Piglets were dosed orally to best represent human exposure and a sensitive window of development was chosen. The doses of DEHP are higher than average human exposure, but neonatal infants are one of the mostly highly exposed human populations, with NICU infant exposure reaching into the mg/kg range [10,11]. Future studies on pigs will include lower doses, larger samples sizes, additional periods of exposure, and longer follow-up times to determine whether early life exposure has longer-term reproductive outcomes.

5. Conclusions

Piglets orally exposed to DEHP in early life had altered hormone levels with sex-specific differences. In addition, gonocyte migration was impaired in male piglets in response to DEHP, with increased apoptosis in treated testes. Collectively, these results are consistent with previous studies in rodents showing that DEHP disrupts gonadal development in early postnatal life. The evidence for the endocrine disrupting effects of DEHP across species emphasizes the need to reassess its use in everyday life.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The reproductive system of pigs is a strong model for humans

Early life exposure to phthalates can disrupt development

Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate disrupts steroidogenesis in piglets

Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate alters gonocyte development in piglets

Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate causes sex-specific effects in piglets

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the members of the Flaws Lab, especially Liying Gao and Karen Chiu.

Funding

This work was supported by the Billie A. Field Fellowship in Reproductive Biology (SR); National Institutes of Health [R01ES032163 (JAF), F31 ES030467 (SR), T32 ES007326 (GRW, SR, DDM), and K99 ES031150 (GRW)].

Abbreviations

- DEHP

Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- PVC

polyvinyl chloride

- NICU

neonatal intensive care unit

- BW

body weight

- SD

study day

- DHEA

dehydroepiandrosterone

- ELISA

enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- TUNEL

terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- DBP

dibutyl phthalate

- EW

epididymis weight

- TW

testes weight

- OW

ovary weight

- UW

uterus weight

- SEM

standard error of the mean

Footnotes

Competing interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease, Toxicological Profile for Di(2-Ethylhexyl)Phthalate (DEHP), (2019) 1–484. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/es/index.html. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Radke EG, Glenn BS, Braun JM, Cooper GS, Phthalate exposure and female reproductive and developmental outcomes: a systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence, Environ. Int. 130 (2019) 104580. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Radke EG, Braun JM, Meeker JD, Cooper GS, Phthalate exposure and male reproductive outcomes: A systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence, Environ. Int. 121 (2018) 764–793. 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].National Toxicology Program, Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate, in: Rep. Carcinog. Fourteenth Ed, 2010: pp. 2009–2011. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hauser R, Calafat AM, Phthalates and human health, Occup. Environ. Med. 62 (2005) 806–818. 10.1136/oem.2004.017590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Barakat R, Seymore T, Lin PCP, Park CJ, Ko CMJ, Prenatal exposure to an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture disrupts testicular steroidogenesis in adult male mice, Environ. Res. 172 (2019) 194–201. 10.1016/j.envres.2019.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hannon PR, Flaws JA, The effects of phthalates on the ovary, Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 6 (2015) 1–19. 10.3389/fendo.2015.00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chiang C, Lewis LR, Borkowski G, Flaws JA, Exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and diisononyl phthalate during adulthood disrupts hormones and ovarian folliculogenesis throughout the prime reproductive life of the mouse, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 393 (2020) 114952. 10.1016/j.taap.2020.114952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Barakat R, Lin PCP, Rattan S, Brehm E, Canisso IF, Abosalum ME, Flaws JA, Hess R, Ko CM, Prenatal exposure to DEHP induces premature reproductive senescence in male mice, Toxicol. Sci. 156 (2017) 96–108. 10.1093/toxsci/kfw248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sjoberg P, Bondesson U, Sedin E, Gustafsson J, Exposure of newborn infants to plasticizers. Plasma levels of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate during exchange transfusion, Transfusion. 25 (1985) 424–428. 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25586020115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Calafat AM, Needham LL, Silva MJ, Lambert G, Exposure to Di-(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Among Premature Neonates in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Pediatrics. 113 (2004) e429. 10.1097/PCC.0b013e3182455558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Smith CA, MacDonald A, Holahan MR, Acute postnatal exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate adversely impacts hippocampal development in the male rat, Neuroscience. 193 (2011) 100–108. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.06.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ge RS, Chen GR, Dong Q, Akingbemi B, Sottas CM, Santos M, Sealfon SC, Bernard DJ, Hardy MP, Biphasic effects of postnatal exposure to diethylhexylphthalate on the timing of puberty in male rats, J. Androl. 28 (2007) 513–520. 10.2164/jandrol.106.001909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Liu J, Wang W, Zhu J, Li Y, Luo L, Huang Y, Zhang W, Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) influences follicular development in mice between the weaning period and maturity by interfering with ovarian development factors and microRNAs, Environ. Toxicol. 33 (2018) 535–544. 10.1002/tox.22540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang Y, Mu X, Gao R, Geng Y, Liu X, Chen X, Wang Y, Ding Y, Wang Y, He J, Foetal-neonatal exposure of Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate disrupts ovarian development in mice by inducing autophagy, J. Hazard. Mater. 358 (2018) 101–112. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Heindel JJ, Vandenberg LN, Developmental Origins of Health and Disease: A Paradigm for Understanding Disease Etiology and Prevention, Curr Opin Pediatr. 27 (2015) 248–253. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000191.Developmental. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Yang C, Song G, Lim W, Effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals in pigs, Environ. Pollut. 263 (2020) 114505. 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hirshfield AN, Development of follicles in the mammalian ovary, Int. Rev. Cytol. 124 (1991) 43–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Oxender D, Colenbrander B, Development in Fetal and Prepubertal Pigs retard an in and neonatal development rabbit fetuses from the fetal survival on studied that days the fetal ovary Gulyas to could by be The primordial ovaries ovulation caused follicular calves Follicular lating o, (1979) 715–721. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Lyche JL, Gutleb AC, Bergman Å, Eriksen GS, Murk AJ, Ropstad E, Saunders M, Skaare JU, Reproductive and Developmental Toxicity of Phthalates, J. Toxicol. Environ. Heal. Part B. 12 (2009) 225–249. 10.1080/10937400903094091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM, Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans., Environ. Health Perspect. 101 (1993) 378–84. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1519860&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Oxender D, Colenbrander B, Development in Fetal and Prepubertal Pigs retard an in and neonatal development rabbit fetuses from the fetal survival on studied that days the fetal ovary Gulyas to could by be The primordial ovaries ovulation caused follicular calves Follicular lating o, Biol. Reprod. (1979) 715–721.497327 [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peters H, Migration of Gonocytes Into the Mammalian Gonad and Their Differentiation, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 259 (1970) 91–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Warner GR, Meling DD, De La Torre KM, Wang K, Flaws JA, Environmentally relevant mixtures of phthalates and phthalate metabolites differentially alter the cell cycle and apoptosis in mouse neonatal ovaries, Biol. Reprod. 104 (2021) 806–817. 10.1093/biolre/ioab010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Flaws JA, Doerr JK, Sipes IG, Hoyer PB, Destruction of preantral follicles in adult rats by 4-vinyl-1-cyclohexene diepoxide, Reprod. Toxicol. 8 (1994) 509–514. 10.1016/0890-6238(94)90033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Martínez-Giner M, Noguera JL, Balcells I, Fernández-Rodríguez A, Pena RN, Selection of Internal Control Genes for Real-Time Quantitative PCR in Ovary and Uterus of Sows across Pregnancy, PLoS One. 8 (2013). 10.1371/journal.pone.0066023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hannon PR, Niermann S, Flaws JA, Acute Exposure to Di(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate in Adulthood Causes Adverse Reproductive Outcomes Later in Life and Accelerates Reproductive Aging in Female Mice, Toxicol. Sci. 150 (2016) 97–108. 10.1093/toxsci/kfv317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hannon PR, Peretz J, Flaws JA, Daily Exposure to Di(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate Alters Estrous Cyclicity and Accelerates Primordial Follicle Recruitment Potentially Via Dysregulation of the Phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase Signaling Pathway in Adult Mice1, Biol. Reprod. 90 (2014) 1–11. 10.1095/biolreprod.114.119032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Zhou C, Gao L, Flaws JA, Prenatal exposure to an environmentally relevant phthalate mixture disrupts reproduction in F1 female mice, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 318 (2017) 49–57. 10.1016/j.taap.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Brehm E, Rattan S, Gao L, Flaws JA, Prenatal exposure to Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate causes long-term transgenerational effects on female reproduction in mice, Endocrinology. 159 (2018) 795–809. 10.1210/en.2017-03004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hannon PR, Brannick KE, Wang W, Flaws JA, Mono(2-Ethylhexyl) Phthalate Accelerates Early Folliculogenesis and Inhibits Steroidogenesis in Cultured Mouse Whole Ovaries and Antral Follicles, Biol. Reprod. 92 (2015) 120–120. 10.1095/biolreprod.115.129148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Hannon PR, Brannick KE, Wang W, Gupta RK, Flaws JA, Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate inhibits antral follicle growth, induces atresia, and inhibits steroid hormone production in cultured mouse antral follicles, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 284 (2015) 42–53. 10.1016/j.taap.2015.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rattan S, Brehm E, Gao L, Flaws JA, Di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate exposure during prenatal development causes adverse transgenerational effects on female fertility in mice, Toxicol. Sci. 163 (2018) 420–429. 10.1093/toxsci/kfy042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Rattan S, Beers HK, Kannan A, Ramakrishnan A, Brehm E, Bagchi I, Irudayaraj JMK, Flaws JA, Prenatal and ancestral exposure to di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate alters gene expression and DNA methylation in mouse ovaries, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 379 (2019) 114629. 10.1016/j.taap.2019.114629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Barakat R, Lin PC, Park CJ, Zeineldin M, Zhou S, Rattan S, Brehm E, Flaws JA, Ko CMJ, Germline-dependent transmission of male reproductive traits induced by an endocrine disruptor, di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate, in future generations, Sci. Rep 10 (2020) 1–18. 10.1038/s41598-020-62584-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chedrese PJ, Feyles F, The diverse mechanism of action of dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE) and methoxychlor in ovarian cells in vitro, Reprod. Toxicol. 15 (2001) 693–698. 10.1016/S0890-6238(01)00172-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Karpeta A, Rak-Mardyła A, Jerzak J, Gregoraszczuk EL, Congener-specific action of PBDEs on steroid secretion, CYP17, 17β-HSD and CYP19 activity and protein expression in porcine ovarian follicles, Toxicol. Lett. 206 (2011) 258–263. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Chaparro-Ortega A, Betancourt M, Rosas P, Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Chavira R, Bonilla E, Casas E, Ducolomb Y, Endocrine disruptor effect of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) on porcine ovarian cell steroidogenesis, Toxicol. Vitr. 46 (2018) 86–93. 10.1016/j.tiv.2017.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ljungvall K, Karlsson P, Hultén F, Madej A, Norrgren L, Einarsson S, Rodriguez-Martinez H, Magnusson U, Delayed effects on plasma concentration of testosterone and testicular morphology by intramuscular low-dose di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate or oestradiol benzoate in the prepubertal boar, Theriogenology. 64 (2005) 1170–1184. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Boekelheide K, Johnson KJ, Chapter 20 - Sertoli Cell Toxicants, Sertoli Cell Biol. (2005) 345–382. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Fisher JS, Environmental anti-androgens and male reproductive health: Focus on phthalates and testicular dysgenesis syndrome, Reproduction. 127 (2004) 305–315. 10.1530/rep.1.00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Howdeshell KL, Rider CV, Wilson VS, Gray LE, Mechanisms of action of phthalate esters, individually and in combination, to induce abnormal reproductive development in male laboratory rats, Environ. Res. 108 (2008) 168–176. 10.1016/j.envres.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Shansky RM, Murphy AZ, Considering sex as a biological variable will require a global shift in science culture, Nat. Neurosci. 24 (2021) 457–464. 10.1038/s41593-021-00806-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Clayton JA, Collins FS, NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies, Nature. 509 (2014) 282–283. 10.1038/509282a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Vandenberg LN, Colborn T, Hayes TB, Heindel JJ, Jacobs DR, Lee D-H, Shioda T, Soto AM, Vom Saal FS, V Welshons W, Zoeller RT, Myers JP, Hormones and Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals: Low-Dose Effects and Nonmonotonic Dose Responses., Endocr. Rev. 33 (2012) 1–78. 10.1210/er.2011-1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.