Abstract

In the 1990s, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis has caused 15 outbreaks in Finland; 12 of them were caused by phage type 1 (PT1) and PT4. Thus far, there has been no clear evidence as to the source of these Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4 strains, so it was necessary to try to characterize them further. Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 (n = 57) and PT4 (n = 43) isolates from different sources were analyzed by genomic pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), plasmid profiling, and antimicrobial resistance testing to investigate the distribution of their subtypes in Finland. It was also hoped that this investigation would help in identifying the sources of the infections, especially the sources of the outbreaks caused by PT1 and PT4 in the 1990s. The results showed that both PFGE and plasmid profiling, but not antimicrobial susceptibility testing, were capable of differentiating isolates of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4. By genotypic methods, it was possible to divide both PT1 and PT4 isolates into 12 subtypes. It could also be shown that all PT1 outbreak isolates were identical and, at least with this collection of isolates, that the outbreaks did not originate from the Baltic countries or from Russia, where this phage type predominates. It was also established that the outbreaks caused by PT4 all had different origins. Valuable information for future investigations was gained on the distribution of molecular subtypes of strains that originated from the tourist resorts that are popular among Finns and of strains that were isolated from livestock.

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis is the most common serovar that causes salmonellosis in humans. Since the 1980s, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of reported findings of this serovar in Europe and worldwide (8, 13, 19). The most frequent reservoir for Salmonella Enteritidis has been poultry, especially eggs (19). The occurrence of the phage types of Salmonella Enteritidis in different geographical areas has varied: phage type 1 (PT1) has been common in the Baltic countries and Russia (7), whereas PT4 most often has been seen in Western European countries (9, 20). PT8 apparently has been a frequent finding in the United States (8).

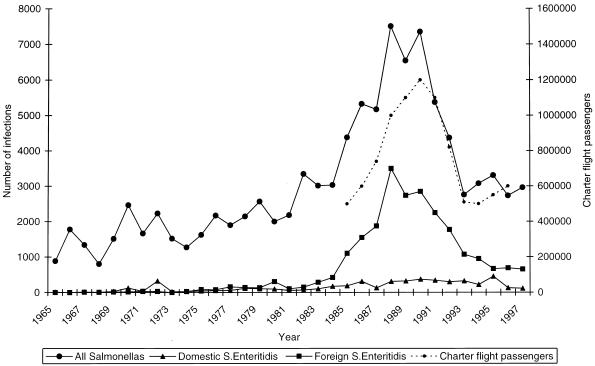

The proportion of Salmonella Enteritidis causing indigenously acquired salmonellosis has greatly increased in Finland in the past few years. The strains that have been the cause of this increase have originated from abroad, whereas the proportion of domestic strains has remained fairly constant (Fig. 1). Salmonella Enteritidis has caused 15 domestic outbreaks during the 1990s; 9, 3, and 3 were caused by Salmonella Enteritidis PT1, Salmonella Enteritidis PT4, and other phage types, respectively (21a).

FIG. 1.

Number of all salmonella infections, number of domestic and foreign Salmonella (S.) Enteritidis infections in Finland between 1965 and 1997 (21a), and number of Finnish passengers on charter flights (statistics of the Civil Aviation Administration and Statistics Finland).

When one is tracing the origin of a salmonella infection, it is important to differentiate between strains in great detail. Traditional epidemiological methods include biotyping, serotyping, and phage typing of isolates, as well as antimicrobial susceptibility testing, although these methods do not always give enough information for epidemiological purposes. Also, phage typing is not available in all laboratories, and certain strains of Salmonella Enteritidis can change phage types (1, 16, 17, 27, 28). Some phage types may predominate in a geographical area, a fact which may limit the use of phage typing in investigating local outbreaks. However, more information can be gathered by analyzing plasmids from the isolates (2, 29) or chromosomal DNA by different molecular techniques, such as ribotyping (6), IS200 typing (23), or pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) (15).

In Finland, data on the epidemiologic characteristics and potential reservoirs of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4 have been insufficient. To gain more detailed information, the highly discriminatory technique PFGE was chosen for subtyping of the strains of these phage types (11, 14, 18). Plasmid analysis and antimicrobial susceptibility testing were used to complement the results of PFGE.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Salmonella isolates.

All strains had previously been phage typed as Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4 according to the scheme of Ward et al. (31) at the Laboratory of Enteric Pathogens and stored at −70°C in sterilized skim milk or at room temperature in nutrient agar tubes. Along with a set of PT1 and PT4 outbreak isolates, representative sets of nonoutbreak isolates from humans, as well as all available PT1 and PT4 isolates from livestock and foodstuffs, were included in the study.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT1.

Fifty-seven strains of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 were studied (Table 1); 26 of the 51 human isolates were of domestic origin, and 6 of them represented the PT1 outbreaks in a 5-year period from 1991 to 1995 (Fig. 2 and Table 2). Two isolates (chicken liver and eggshell) were obtained from the poultry farm that was the source of the outbreaks in Turku, Finland (10). Twenty-five strains were of foreign origin; 4 of them were obtained from the Baltic countries (kindly sent by Unna Jöks, Central Laboratory of Microbiology, Health Protection Inspectorate, Tallinn, Estonia), and 21 were isolated from Finnish tourists who had been abroad preceding their salmonella infections. These nonoutbreak strains were selected randomly to represent strains from various countries. Three nonoutbreak strains were from animals, and one was from foodstuffs.

TABLE 1.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 isolates

| Strain | Geographic origin/source | Yr of isolation | PFGE subtype | Plasmid profile | Antimicrobial resistancea | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IH 68475 | Finland, Jyväskylä | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68476 | Finland, Rovaniemi | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68477 | Finland, Kuopio | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 104209 | Finland, Helsinki | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68473 | Finland, Kuopio | 1996 | 1A | d | Human isolate | |

| IH 69249 | Finland, Haukipudas | 1997 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69250 | Finland, Heinola | 1997 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69257 | Finland, Kajaani | 1997 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69263 | Finland, Helsinki | 1997 | 1A | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68250 | Baltic countries | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68251 | Baltic countries | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68480 | Estonia | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68485 | Norway | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 104498 | Portugal | 1996 | 1A | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68484 | Germany | 1996 | 1A | c | Sul, Tet, Str | Human isolatec |

| IH 68481 | Latvia | 1996 | 1A | d | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69286 | Estonia | 1997 | 1A | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69441 | Estonia | 1998 | 1A | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69043 | Baltic countries | 1998 | 1A | a | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69045 | Baltic countries | 1998 | 1A | a | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68478 | Finland, Helsinki | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 104682 | Finland, Vihti | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68479 | Finland, Helsinki | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69264 | Finland, Seinäjoki | 1997 | 1B | a | Nal | Human isolate |

| IH 68979 | Finland, Ikaalinen | 1998 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69026 | Finland, Helsinki | 1998 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 68875 | Finland, Nummi-Pusula | 1998 | 1B | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 69434 | Finland, Hämeenlinna | 1998 | 1B | e | Human isolate | |

| IH 68489 | Spain | 1993 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68490 | France | 1994 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 67741 | Portugal | 1995 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68482 | Poland | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68483 | Spain | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 68486 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1996 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69241 | Portugal | 1997 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69246 | Germany | 1997 | 1B | f | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69442 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1998 | 1B | a | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69440 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1998 | 1B | a | Nal | Human isolatec |

| IH 69443 | Spain | 1998 | 1B | a | Nal | Human isolatec |

| IH 69435 | Finland/strip of leek | 1995 | 1B | a | Foodstuff | |

| IH 68487 | Finland/cow | 1995 | 1B | a | Animal isolate, sweep sample | |

| IH 68488 | Finland/cow | 1995 | 1B | a | Animal isolate, sweep sample | |

| IH 68474 | Finland, Vihti | 1996 | 1C | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 104210 | Finland, Jyväskylä | 1996 | 1D | g | Human isolate | |

| IH 67791 | Finland/cow | 1994 | 1E | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 59089 | Finland, Vieremä | 1991 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 59439 | Finland, Vieremä | 1991 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 59958 | Finland, Turku | 1992 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 59943 | Finland, Turku | 1993 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 66842 | Finland, Turku | 1994 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 67745 | Finland, Turku | 1995 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 68964 | Finland, Tornio | 1998 | 1F | a | Human isolate | |

| IH 67832 | Finland/chicken liver | 1995 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, animal isolated | |

| IH 67920 | Finland/eggshell | 1995 | 1F | a | Outbreak strain, foodstuffd | |

| IH 59430 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1992 | 1F | b | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69277 | Hungary | 1997 | 1F | b | Human isolatec | |

| IH 69282 | Russia | 1997 | 1G | d | Human isolatec |

The strain is sensitive to ampicillin (Amp), chloramphenicol (Chl), ceftriaxone (Cef), imipenem (Imi), mecillinam (Mec), nalidixic acid (Nal), neomycin (Neo), sulfonamide (Sul), tetracycline (Tet), trimethoprim (Tmp), streptomycin (Str), and ciprofloxacin (Cip) unless resistance is otherwise shown.

The strain was provided by the Central Laboratory of Microbiology, Health Protection Inspectorate, Tallinn, Estonia.

The strain was from a Finnish tourist who had visited the country listed before the salmonella finding.

The strain was from an outbreak in a Finnish commercial layer flock (10).

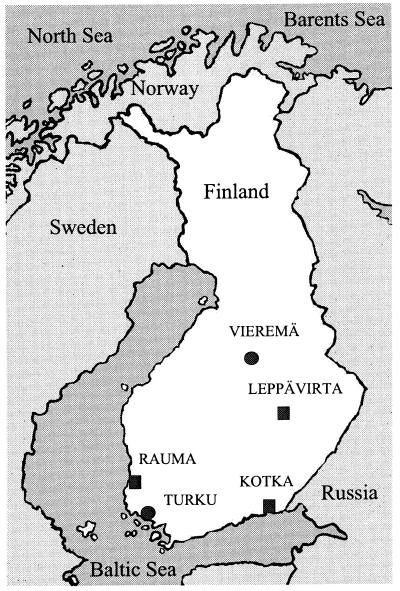

FIG. 2.

Geographic occurrence of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 (●) and PT4 (■) outbreaks in Finland in the 1990s. See Table 2 for the number of infections in each outbreak.

TABLE 2.

Number of infections in outbreaks

| Phage type | Outbreak area | No. of infections during the indicated yr of the outbreak

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | ||

| PT1 | Turkua | 66 | 50 | 38 | 10 | 10 |

| Turkub | 10 | 99 | 180 | |||

| Vieremä | 20 | |||||

| PT4 | Leppävirta | 17 | ||||

| Rauma | 85 | |||||

| Kotka | 12 | |||||

First outbreak.

Second outbreak.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT4.

Forty-three Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 strains were studied (Table 3); 14 of the 32 human isolates were of domestic origin, and 6 of them represented three PT4 outbreaks between 1993 and 1995. Domestic nonoutbreak isolates from 1993 to 1995 were not available, but eight isolates from 1997 to 1998 were included in this study. Eighteen nonoutbreak strains of foreign origin, isolated in Finland from Finnish tourists who had been abroad preceding their salmonella infections, were selected randomly to represent strains from various countries. Eleven strains were from animals.

TABLE 3.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 isolates

| Strain | Geographic origin/source | Yr of isolation | PFGE subtype | Plasmid profile | Antimicrobial resistancea | Additional information |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IH 59741 | Finland, Leppävirta | 1993 | 4A | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 59742 | Finland, Leppävirta | 1993 | 4A | a | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 69444 | Finland, Kuopio | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 68274 | Finland, Tampere | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 69252 | Finland, Helsinki | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 69266 | Finland, Tampere | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 68336 | Finland, Uusi Kaarlepyy | 1997 | 4A | d | Human isolate | |

| IH 69445 | Finland, Juva | 1998 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 69447 | Finland, Palokka | 1998 | 4A | b | Human isolate | |

| IH 68178 | Belgium/pork | 1993 | 4A | b | Animal isolate, imported from Belgium | |

| IH 59883 | Finland/cow | 1993 | 4A | b | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68501 | Finland/cow | 1995 | 4A | b | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68177 | Finland/cow | 1995 | 4A | b | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68232 | England/chicken steak | 1996 | 4A | g | Animal isolate, imported from England | |

| IH 69455 | Finland/cow | 1997 | 4A | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 69261 | Finland/cow | 1997 | 4A | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68651 | Finland/turkey | 1997 | 4A | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 69265 | Finland/turkey | 1997 | 4A | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68502 | France, Belgium | 1993 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68544 | Turkey | 1993 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68503 | Hungary | 1993 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68509 | Belgium | 1995 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68506 | Lithuania | 1995 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68505 | Cyprus | 1995 | 4A | c | Sul, Str | Human isolateb |

| IH 68508 | Germany | 1995 | 4A | d | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69225 | Belgium | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69228 | England | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69245 | Germany | 1997 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69279 | Hungary | 1997 | 4A | e | Mec | Human isolateb |

| IH 69000 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1998 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69453 | Thailand | 1998 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68952 | Dominican Republic | 1998 | 4A | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 69454 | Spain, Canary Islands | 1998 | 4A | c | Sul, Str | Human isolateb |

| IH 68189 | Finland, Kotka | 1995 | 4B | g | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 68190 | Finland, Kotka | 1995 | 4B | g | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 69456 | Finland/cow | 1997 | 4B | g | Animal isolate, feces | |

| IH 68507 | Spain | 1995 | 4B | g | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68545 | Italy | 1993 | 4C | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 68504 | Turkey | 1995 | 4D | b | Human isolateb | |

| IH 67650 | Finland, Rauma | 1995 | 4E | b | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 67651 | Finland, Rauma | 1995 | 4E | b | Outbreak strain, human isolate | |

| IH 69446 | Finland, Mikkeli | 1998 | 4F | c | Sul, Tet | Human isolate |

| IH 68656 | France/turkey | 1997 | 4G | f | Animal isolate, imported from France |

The strain is sensitive to ampicillin (Amp), chloramphenicol (Chl), ceftriaxone (Cef), imipenem (Imi), mecillinam (Mec), nalidixic acid (Nal), neomycin (Neo), sulfonamide (Sul), tetracycline (Tet), trimethoprim (Tmp), streptomycin (Str), and ciprofloxacin (Cip) unless resistance is otherwise shown.

The strain was from a Finnish tourist who had visited the country listed before the salmonella finding.

PFGE.

Salmonella strains were grown overnight on Drigalski-Conradi agar plates at 37°C. Bacterial cells were suspended in 1,200 μl of TEN (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.15 M NaCl, 0.1 M EDTA [pH 7.5]) to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.150 to 0.200. This cell suspension was mixed in equal parts with molten 2% low-melting-point agarose (SeaPlaque agarose; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine), and the mixture was pipetted into plug molds. The plugs were incubated overnight at 55 to 57°C in ES buffer (0.5 M EDTA, 1% N-(auroylsarcosine) with 0.15 mg of proteinase K per ml. The plugs were washed with TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]) for 30 min, with TE buffer–4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride for 30 min to inactivate proteinase K, and with TE buffer three times for 30 min each time. The conditions for restriction endonuclease digestion and PFGE were essentially those described by Thong et al. (26). Chromosomal DNA was digested with 10 U of restriction enzymes XbaI, SpeI, and NotI (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) overnight at 37°C. Electrophoresis was performed at 210 V on 1.0% SeaKem ME agarose gels (FMC BioProducts) with a Gene Navigator system (Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) or with CHEF Mapper systems (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Richmond, Calif.). Running conditions were as follows: XbaI digests, 5 to 70 s for 24 h; SpeI digests, 5 to 40 s for 24 h; and NotI digests, 1 to 20 s for 20 h. A bacteriophage lambda ladder consisting of concatemers in increments of 48.5 kbp (New England BioLabs Inc., Beverly, Mass.) was used as a molecular weight standard. Any difference between two profiles was considered sufficient to distinguish two different PFGE profiles. XbaI-digested PFGE profiles were named with uppercase letters starting at A; the numbers 1 and 4 indicate whether the strain belonged to PT1 or PT4, respectively.

Plasmid profiling.

Plasmid DNA was isolated by the alkaline lysis method as described earlier (5). Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis at 120 V for 70 min on horizontal 0.9% SeaKem ME agarose gels with a CIBCO BRL Horizon 20.25 system (Life Technologies Inc., Gathersburg, Md.). The gels were stained for 30 min with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) and photographed under UV illumination. Plasmid-containing strains RH 4240 (39R861 [30]) and RH 4241 (V517 [12]) were used as controls. Plasmid profiles were named with lowercase letters starting at a.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

The antimicrobial susceptibilities of the strains were determined by the agar diffusion method on semisynthetic Iso-Sensitest medium with the following antimicrobial agents (4): ampicillin, chloramphenicol, ceftriaxone, imipenem, mecillinam, nalidixic acid, neomycin, sulfonamide, tetracycline, trimethoprim, streptomycin, and ciprofloxacin (Neo-Sensitabs; A/S Rosco, Taastrup, Denmark). Inhibition zones were interpreted according to the recommendations of the Swedish Reference Group for Antibiotics (24).

RESULTS

Salmonella Enteritidis PT1.

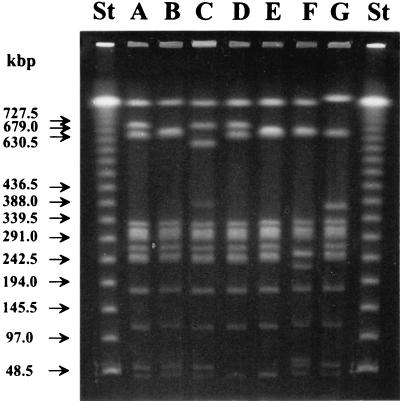

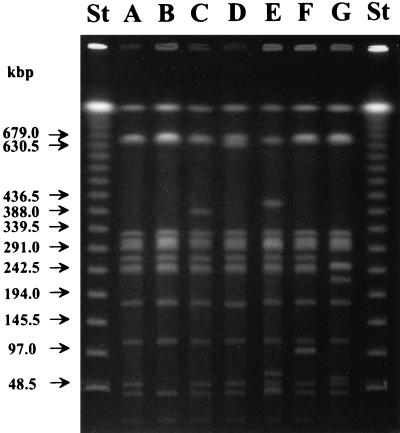

Seven banding patterns (subtypes 1A to 1G) were observed among the 57 PT1 strains studied by PFGE (Table 1 and Fig. 3) when chromosomal DNAs of the strains were digested with restriction enzyme XbaI. Different test conditions showed that subtypes 1B, 1E, and 1F had fragments at 676 and 661 kb, although only one of these was visible in the fragment pattern (Fig. 3). All eight outbreak strains from Turku and Vieremä, in addition to three nonoutbreak strains belonged to PFGE subtype 1F (Table 1). Among the nonoutbreak strains, the most common PFGE subtypes were 1A (20 strains) and 1B (22 strains), whereas subtypes 1C, 1D, and 1E each included only one strain.

FIG. 3.

PFGE banding patterns of different subtypes (1A to 1G) of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 isolates obtained when chromosomal DNA was digested with restriction enzyme XbaI. Lanes St, lambda ladder used as a molecular size marker. Arrows indicate the positions of the marker DNA fragments. Lane F, outbreak strains from Turku and Vieremä.

Six strains—one each from Turku and Vieremä, one from chicken liver, two from the Baltic countries, and one from Finnish cattle—were also digested with restriction enzymes SpeI and NotI. All six SpeI-digested strains had indistinguishable PFGE profiles. When digested with NotI, strains from Turku, Vieremä, and chicken liver had similar PFGE profiles, but they were different from those of the two strains from the Baltic countries and the single strain from Finnish cattle (data not shown).

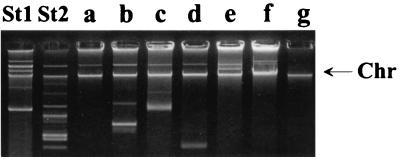

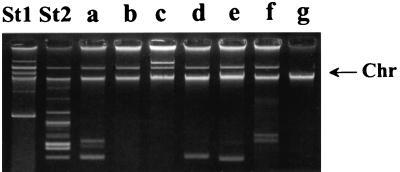

Seven plasmid profiles (a to g) were identified by plasmid analysis (Table 1 and Fig. 4). Profile a had one plasmid; b had four plasmids; c had three; d, e, and f each had two; and g was plasmid free (Fig. 4). Forty-seven of the 57 strains studied, including all 8 outbreak strains, had plasmid profile a, regardless of the origin (human or nonhuman, domestic or foreign) (Table 1).

FIG. 4.

Plasmid profiles (a to g) of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 isolates. Lane St1, Escherichia coli RH 4240 (39R861) (control). Lane St2, E. coli RH 4241 (V517) (control). The arrow indicates the position of the chromosomal DNA fragment.

When the PFGE and plasmid types were compiled, all outbreak strains belonged to subtype 1Fa. Most of the strains associated with Eastern Europe belonged to subtype 1Aa, and those associated with Western Europe belonged to subtype 1Ba. Any other clear categories based on the origin being either domestic or foreign could not be made. Two strains isolated from animals belonged to subtype 1Ba, and one belonged to subtype 1Eg (Table 1).

Twelve subtypes (Aa, Ac, Ad, Ba, Be, Bf, Ca, Dg, Eg, Fa, Fb, and Gd) were observed among the 57 PT1 strains when the results of PFGE and plasmid analyses were compiled. Four nonoutbreak strains were resistant to some antibiotics, but all other strains were sensitive to all antimicrobial agents tested (Table 1).

Salmonella Enteritidis PT4.

Seven banding patterns (subtypes 4A to 4G) were represented among the 43 PT4 strains studied by PFGE after XbaI restriction of genomic DNAs (Table 3 and Fig. 5). With different test conditions, it could be seen that subtypes 4A, 4B, 4C, 4F, and 4G had fragments at 646 and 661 kb, although only one of these was visible in the fragment pattern (Fig. 5). Of the 43 strains studied, 33, including the outbreak strains from Leppävirta, belonged to PFGE subtype 4A (Table 3).

FIG. 5.

PFGE banding patterns of different subtypes (4A to 4G) of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 isolates obtained when chromosomal DNA was digested with restriction enzyme XbaI. Lanes St, lambda ladder used as a molecular size marker. Arrows indicate the positions of the marker DNA fragments. Lane A, outbreak strains from Leppävirta; lane B, outbreak strain from Kotka; lane E, outbreak strain from Rauma.

The outbreak strains (from Leppävirta, Rauma, and Kotka) and three other strains were digested with restriction enzymes SpeI and NotI (data not shown). When digested with SpeI, only the outbreak strain from Kotka differed from the other strains in its PFGE profile. Similarly, the PFGE profile of the outbreak strain from Rauma was the only one that differed from those of the other strains when digested with NotI.

Seven plasmid profiles (a to g) were identified by plasmid analysis (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Profile a had four plasmids; b had one; c, d, and e each had two; f had three; and g was plasmid free (Fig. 6). The most common profiles were b and g; 25 of the 43 strains had the former profile, and 9 had the latter profile (Table 3).

FIG. 6.

Plasmid profiles (a to g) of Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 isolates. Lane St1, E. coli RH 4240 (39R861) (control). Lane St2, E. coli RH 4241 (V517) (control). The arrow indicates the position of the chromosomal DNA fragment.

The six outbreak strains were divided into three subtypes: 4Aa (Leppävirta in 1993), 4Bg (Kotka in 1995), and 4Eb (Rauma in 1995) (Table 3). The subtype distribution among the nonoutbreak strains differed from these. However, subtype 4Bg, which was the cause of the outbreak in Kotka in 1995, was isolated from a patient who had returned from Spain in 1995; this subtype was also isolated from a Finnish cow in 1997 (Table 3).

When the results of PFGE and plasmid analyses were compiled, 12 subtypes (Aa, Ab, Ac, Ad, Ae, Ag, Bg, Cb, Db, Eb, Fc, and Gf) were observed among the 43 PT4 strains. Four nonoutbreak strains were resistant to some antibiotics, whereas all other strains were sensitive to all antimicrobial agents tested (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

A large set of Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4 isolates from different sources was analyzed by PFGE, plasmid profiling, and antimicrobial resistance testing to gain knowledge of the distribution of their potential subtypes in Finland. It was especially hoped that these analyses would help in determining the sources of the several outbreaks caused by PT1 and PT4 isolates in the 1990s.

Finland has traditionally had very strict salmonella control for livestock, a fact which has made it easier to keep indigenously acquired salmonella infections rare, unlike in many other European countries. The European Union allowed Finland to continue with this control system even after it joined the Union. Most of the salmonella infections diagnosed in Finland have been related to a trip abroad (21, 22). In the mid-1980s, infections caused by Salmonella Enteritidis began to increase in parallel with the increasing number of Finns vacationing abroad (Fig. 1). In the 1990s, Salmonella Enteritidis caused 15 outbreaks in Finland; 12 of them were caused by PT1 and PT4. However, it remained unclear from where these outbreaks originated; it was possible that the infections were connected to imported foodstuffs, that they were secondary infections caused by strains of foreign origin, or that there were some hidden reservoirs in Finnish production animals. Thus, it was necessary to try to characterize the PT1 and PT4 isolates further.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 was the cause of eight outbreaks in the area around Turku over a period of 5 years. In 1995, the infection source was finally found to be a poultry farm near Turku. This was the first time that Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 was detected in a Finnish commercial layer flock (10). As a result, the poultry farm was closed down, but the original source of the PT1 strain was never discovered. There were some suspicions that this strain was somehow imported from the Baltic countries, where Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 strains have been the most common Salmonella strains found in eggs (7).

The results of this study confirmed the earlier findings (10) that the Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 1Fa strain that had caused the outbreaks in Turku indeed had originated from the nearby poultry farm. It was interesting that the strains isolated in Estonia and those isolated from the Finnish tourists who had visited the Baltic countries were of type 1Aa, thus differing from the 1Fa outbreak strain and suggesting that the original source was not the Baltic countries. The 1Fa strain was also found to be the cause of the outbreak in Vieremä, which is located about 500 km northeast of Turku. Unfortunately, no connection between the outbreaks caused by identical strains in Vieremä and Turku could be found either at the time of the outbreaks or later on. Subtype 1Fa seemed to be very rare in Finland: only 1 of the 48 nonoutbreak strains belonged to this subtype, which differed from the other nonoutbreak strain subtypes by four to nine chromosomal fragments.

Among the nonoutbreak PT1 strains, subtype 1Aa seemed to be associated with Eastern Europe, and subtype 1Ba seemed to be associated with Western Europe. Type 1Ba also included two isolates from Finnish cattle. This was an important finding because there has been no identified reservoir for Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 in Finland since the commercial layer flock outbreaks in 1991 to 1995.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 has caused three outbreaks in different parts of Finland in the 1990s: the first was in Leppävirta in April 1993, the second was in Rauma in March 1995, and the third was in Kotka in December 1995. No connections were found between these three outbreaks at the time, and their sources were never established.

Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 is the most common phage type that contaminates eggs in Central Europe (20) and in England (9). In Finland, however, Salmonella Enteritidis PT4 has been found very rarely in cattle, less than 10 times in turkeys, and never in eggs. Imported meat has occasionally tested positive for Salmonella Enteritidis PT4.

Most of the PT4 strains belonged to PFGE subtype 4A. However, plasmid profiling was able to distinguish six profiles within this PFGE subtype. Among the 33 subtype 4A strains, only the outbreak strain in Leppävirta belonged to subtype 4Aa. Subtype 4Eb, which caused the outbreak in Rauma, differed from subtype 4Aa by three PFGE and plasmid fragments and was not found in other strains investigated here. The outbreak strain isolated in Kotka belonged to subtype 4Bg, which differed from subtype 4Ab only by one plasmid (about 45 to 60 kb), which was about the same size as the fragment that distinguished subtypes 4B and 4A in PFGE. Thus, strains of subtypes 4Bg and 4Ab could be of the same origin if these strains had lost or acquired a plasmid of this size. This finding suggests that subtypes 4Bg and 4Ab isolated from Finnish cows potentially have a reservoir in Finnish cattle and that this reservoir might have been the source of the outbreak in Kotka if these strains had lost or acquired a plasmid. These suggestions would also explain the 1997 and 1998 human isolates that belonged to subtype 4Ab. In addition, 4Bg and 4Eb differed by four PFGE fragments, whereas 4Bg and 4Aa differed by only one PFGE fragment. This one fragment was also smaller than 125 kb, a result which could indicate interference from an unstable fragment of plasmid DNA (14). However, these two subtypes, 4Bg and 4Aa, differed by four plasmids. Considering all of these results, it seems that the outbreaks in Leppävirta, Rauma, and Kotka had different origins.

This study showed that both PFGE and plasmid profiling were capable of differentiating between Salmonella Enteritidis PT1 and PT4 isolates. Some of the isolates with different PFGE subtypes had a difference of only one or two fragments in their PFGE banding patterns when digested with XbaI. Recent point mutations within a subtype might account for these minor differences (25), although the study of Murase et al. (13) concluded that the PFGE profiles of strains digested with XbaI were not affected by point mutations. Salmonellae can spontaneously lose or acquire plasmids (3), a fact which limits the use of plasmid analysis for epidemiological investigations. In this study, however, if there was a difference of several fragments in the plasmid profiles of two strains, it was considered to support the results of PFGE showing fragment patterns that differed by only a few fragments. Additional tests were done with two other restriction enzymes, SpeI and NotI. The discriminatory power of these two enzymes was, however, lower than that of XbaI.

It is also worth mentioning that without phage typing, PFGE would not have been effective in distinguishing between PT1 and PT4, since some strains showed almost identical PFGE banding patterns (1F and 4G; 1B and 4A), regardless of their phage type. In addition, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was not useful because most of the strains were sensitive to all antimicrobial agents tested.

With this collection of isolates, the genotypic methods used here showed that all PT1 isolates associated with the outbreaks were identical to each other and differed from those associated with the Baltic countries and Russia, where this phage type predominates (7). It was also established that the outbreaks caused by PT4 all had different origins. Furthermore, valuable information for future investigations was gained on the distributions of the molecular subtypes of strains that originated from the tourist resorts that are popular among Finns and of the subtypes of strains isolated from domestic production animals.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Unna Jöks for providing strains from the Baltic countries. We also thank Liisa Immonen, Tarja Heiskanen, and Ritva Taipalinen for skillful technical assistance and advice, Sinikka Pelkonen and Saija Hallanvuo for helpful discussions and useful comments, and Maarit Koukkari for editorial assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown D J, Baggesen D L, Platt D J, Olsen J E. Phage type conversion in Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis caused by the introduction of a resistance plasmid of incompatibility group X (IncX) Epidemiol Infect. 1999;122:19–22. doi: 10.1017/s0950268898001794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown D J, Threlfall E J, Hampton M D, Rowe B. Molecular characterization of plasmids in Salmonella enteritidis phage types. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;110:209–216. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800068126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown D J, Threlfall E J, Rowe B. Instability of multiple drug resistance plasmids in Salmonella typhimurium isolated from poultry. Epidemiol Infect. 1991;106:247–257. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800048391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Casals J B, Pringler N. Antibacterial and antifungal sensitivity testing using Neo-Sensitabs. 9th ed. Taastrup, Denmark: A/S Rosco Diagnostica; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grinsted J, Bennet P M. Preparation and electrophoresis of plasmid DNA. Methods Microbiol. 1988;21:129–142. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gruner E, Martinetti L G, Hoop R K, Altwegg M. Molecular epidemiology of Salmonella enteritidis. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:85–89. doi: 10.1007/BF01717458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasenson L B, Kaftyreva L, Laszló V G, Woitenkova E, Nesterova M. Epidemiological and microbiological data on Salmonella enteritidis. Acta Microbiol Hung. 1992;39:31–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickman-Brenner F W, Stubbs A D, Farmer J J., III Phage typing of Salmonella enteritidis in the United States. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:2817–2823. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.12.2817-2823.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Humphrey T J, Baskerville A, Maver S, Rove B, Hopper S. Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 from the contents of intact eggs: a study involving naturally infected hens. Epidemiol Infect. 1989;103:415–423. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800030818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johansson T M-L, Schildt R, Ali-Yrkkö S, Siitonen A, Maijala R L. The first Salmonella Enteritidis phage type 1 infection of a commercial layer flock in Finland. Acta Vet Scand. 1996;37:471–480. doi: 10.1186/BF03548087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liebisch B, Schwarz S. Molecular typing of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis isolates. J Med Microbiol. 1996;44:52–59. doi: 10.1099/00222615-44-1-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macrina F L, Kopecko D J, Jones K R, Ayers D J, McCowen S M. A multiple plasmid-containing Escherichia coli strain: convenient source of size reference plasmid molecules. Plasmid. 1978;1:417–420. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(78)90056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murase T, Okitsu T, Nakamura A, Matsushima A, Yamai S. An epidemiological study of Salmonella enteritidis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE): several PFGE patterns observed in isolates from a food poisoning outbreak. Microbiol Immunol. 1996;40:873–875. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1996.tb01153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen J E, Skov M N, Threlfall E J, Brown D J. Clonal lines of Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis documented by IS200-, ribo-, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and RFLP typing. J Med Microbiol. 1994;40:15–20. doi: 10.1099/00222615-40-1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Powell N G, Threlfall E J, Chart H, Rowe B. Subdivision of Salmonella enteritidis PT 4 by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: potential for epidemiological surveillance. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1994;119:193–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb06888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powell N G, Threlfall E J, Chart H, Schofield S L, Rowe B. Correlation of change in phage type with pulsed field profile and 16S rrn profile in Salmonella enteritidis phage types 4, 7 and 9a. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;114:403–411. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800052110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rankin S, Platt D J. Phage conversion in Salmonella enterica serotype Enteritidis: implications for epidemiology. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;114:227–236. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ridley A M, Threlfall E J, Rowe B. Genotypic characterization of Salmonella enteritidis phage types by plasmid analysis, ribotyping, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2314–2321. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.8.2314-2321.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodrigue D C, Tauxe R V, Rowe B. International increase in Salmonella enteritidis: a new pandemic? Epidemiol Infect. 1990;105:21–27. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800047609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schroeter A, Ward L R, Rowe B, Protz D, Hartung M, Helmuth R. Salmonella enteritidis phage types in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 1994;10:645–648. doi: 10.1007/BF01719587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siitonen A. 4th World Congress on Foodborne Infections and Intoxications. 1998. Human salmonelloses in Finland; pp. 254–257. [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Siitonen A. Statistics of the Laboratory of Enteric Pathogens. Helsinki, Finland: National Public Health Institute; 1998. . Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siitonen A, Puohiniemi R. Program and abstracts of the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 1997. Epidemiology of human salmonelloses in Finland: findings of domestic and foreign origins. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanley J, Jones C S, Threlfall E J. Evolutionary lines among Salmonella enteritidis phage types are identified by insertion sequence IS200 distribution. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1991;82:83–90. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(91)90425-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swedish Reference Group for Antibiotics. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacteria—a reference and a methodology manual. Stockholm, Sweden: The Swedish Medical Society and Statens Bakteriologiska Laboratorium; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenover F C, Arbeit R D, Goering R V, Mickelsen P A, Murray B E, Persing D H, Swaminathan B. Interpreting chromosomal DNA restriction patterns produced by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: criteria for bacterial strain typing. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2233–2239. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2233-2239.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thong K-L, Cheong Y-M, Puthucheary S, Koh C-L, Pang T. Epidemiologic analysis of sporadic Salmonella typhi isolates and those from outbreaks by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1135–1141. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1135-1141.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Threlfall E J, Chart H. Interrelationship between strains of Salmonella enteritidis. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:1–8. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800056612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Threlfall E J, Chart H, Ward L R, de Sa J D H, Rowe B. Interrelationships between strains of Salmonella enteritidis belonging to phage types 4, 7, 7a, 8, 13, 13a, 23, 24 and 30. J Appl Bacteriol. 1993;75:43–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1993.tb03405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Threlfall E J, Hampton M D, Chart H, Rowe B. Use of plasmid profile typing for surveillance of Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 from humans, poultry and eggs. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:25–31. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Threlfall E J, Rowe B, Ferguson J L, Ward L R. Characterization of plasmids conferring resistance to gentamicin and apramycin in strains of Salmonella typhimurium phage type 204c isolated in Britain. J Hyg. 1986;97:419–426. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400063609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ward L R, de Sa J D H, Rowe B. A phage-typing scheme for Salmonella enteritidis. Epidemiol Infect. 1987;99:291–294. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800067765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]