Abstract

Introduction:

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) is a severe developmental defect characterized by the underdevelopment of the left ventricle along with aortic and valvular defects. Multiple palliative surgeries are required for survival. Emerging studies have identified potential mechanisms for the disease onset, including genetic and hemodynamic causes. Genetic variants associated with HLHS include transcription factors, chromatin remodelers, structural proteins, and signaling proteins necessary for normal heart development. Nonetheless, current therapies are being tested clinically and have shown promising results at improving cardiac function in patients who have undergone palliative surgeries.

Areas Covered:

We searched PubMed and clinicaltrials.gov to review most of the mechanistic research and clinical trials involving HLHS. This review discusses the anatomy and pathology of HLHS hearts. We highlight some of the identified genetic variants that underly the molecular pathogenesis of HLHS. Additionally, we discuss some of the emerging therapies and their limitations for HLHS.

Expert Opinion:

While HLHS etiology is largely obscure, palliative therapies remain the most viable option for the patients. It is necessary to generate animal and stem cell models to understand the underlying genetic causes directly leading to HLHS and facilitate the use of gene-based therapies to improve cardiac development and regeneration.

Keywords: Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), pathology, genetic variants, animal model, stem cell, surgery, cell therapy, clinical trials

1. Introduction

Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome (HLHS) is a “single ventricle” malformation which results in the severe underdevelopment of the left ventricle, mitral valve, aortic valve, and ascending aorta. HLHS affects one of every 3,841 newborns, and accounts for nearly 25% of the cardiac deaths in the first year of life1. Children born with this severe congenital heart disease require staged surgical palliation, and in many cases, cardiac transplantation for survival. However, even after surgery, children with HLHS have limited exercise capacity, and are at high risk for developing right ventricular (RV) failure; in cases where there is failed single ventricle palliation, cardiac transplantation is required2.

Numerous genetic variants and molecular pathways implicated in the etiology of HLHS have been discovered in the past few decades; however, a clear understanding of the complex cellular and molecular interactions that cause the observed defects in patients with HLHS is still lacking. Reflecting the need for a diverse array of cell types during normal cardiogenesis, research has expanded to investigate the phenotypes in different cell populations, including endocardial and epicardial cells, in the onset of HLHS.

In this review, we discuss the etiology and key molecular pathways implicated in HLHS, emerging therapeutic targets and strategies for treatment, and provide insight on the future directions of the HLHS research. We primarily use PubMed and clinicaltrials.gov in this manuscript. We included every clinical trial that includes the term “Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome”, as well as the majority of mechanistic papers published in the past decade. Uncovering the molecular pathways involved in the abnormal cardiac development and the cellular dysfunctions found in HLHS will provide the rationale for the development of new therapeutic strategies.

2. Histology and Pathology of HLHS

HLHS is characterized by a spectrum of phenotypes, with an underdeveloped LV as the main one. Based on the anatomical locations, HLHS patients can possess several malformations that lead to the characteristic underdevelopment of the LV (Figure 1). These malformations are the basis of classifying HLHS subtypes. These mainly include aortic or mitral valve stenosis (AS or MS respectively), atresia (AA or MA respectively), or hypoplasia (AH or MH respectively)3, 4. The LV itself may also have different morphologies. These can range from being completely absent, slit-like, miniaturized, or globular 4, 5. Wang et al. measured the RV strain on cardiac magnetic resonance images from 48 HLHS hearts following stage 2 palliation and reported that absent or slit-like LVs were associated with increased longitudinal and radial strain on the RV compared with patients with globular and miniaturized LVs5. Functionally, higher radial strain inhibits fiber shortening and stress, which may be advantageous to patients with absent or slit-like LVs6. Clinically, higher stress in patients with globular and miniaturized LVs could be associated with a higher possibility of subclinical RV dysfunction5, 6. After Fontan palliation, the RV must adapt to become the systemic ventricle. Elevated fiber stress in the RV, as observed in HLHS patients with globular and miniaturized LVs, would require the RV to work harder compared to one with lower fiber stress. This may increase the risk of failing Fontan and the requirement for cardiac transplantation6. Whether these differences in stress and strain between different LV morphologies manifest clinically is still not well understood. More studies are needed to understand the impact of LV morphologies on RV function and outcomes after Fontan palliation. Given its complex presentations, there isn’t a clear consensus on what constitutes HLHS. Anderson et al. suggests that the definition of HLHS should be expanded to include an intact ventricular septum7. This is supported by the fact that it is very rare, almost mutually exclusive, for HLHS to occur simultaneously with ventricular septal defect8. Hattam suggests that surgically disrupting the ventricular septum would equalize the pressures between the LV and RV during development that may provide enough pressure to the LV to promote its growth9. The surgical ventricular septal defect could then be repaired during post-natal surgery. We support the notion to expand the definition of HLHS to include an intact ventricular septum.

Figure 1: Morphological differences between normal and HLHS hearts.

(A) Schematic diagram showing a normal, adult human heart. (B) Schematic diagram of an HLHS heart labelled with the major defects observed in the disease. The purple color indicates mixing of oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood between the aorta and pulmonary arteries.

Based on the pathology of the HLHS hearts, left and right ventricles are reported to have areas of disorganized cardiomyocytes, surrounded by loose connective tissue. These areas possess atypically thin cardiomyocytes with little cytoplasm 10. Surprisingly, HLHS cardiomyocytes ectopically express platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM)-1, an endothelial marker that is not normally expressed in cardiomyocytes10, 11. Ectopic PECAM-1 expression seems to be linked to HLHS phenotypes, as it has not been detected in patients with heart failure10.

Besides the abnormal cardiomyocytes in HLHS, other gross abnormalities have also been observed, including coronary-cameral communications in the form of sinusoidal capillary beds between the epicardial coronary artery and the ventricles3. It is not known the functional impact of these communications on heart function. Nonetheless, patients with such communications have exhibited thickened coronary arteries with focal calcification12. Additionally, HLHS hearts have a propensity for ventricular endocardial fibroelastosis, which often exists with the sinusoidal connections3. More studies are needed to assess the long-term histologic changes in the myocardium and RV, especially following Fontan palliation.

3. Etiology and Prognosis of HLHS

HLHS can be caused by several defects in the left heart, but the most common results from mitral valve stenosis and obstruction of flow into and/or out of the left ventricle, ultimately leading to a hypoplastic left ventricle13. In cases where the aortic valve is defective, increased afterload in the left ventricle leads to the dilation of the ventricle and decreased contractility. As a result, diminished blood flow results in hypoplasia of the left ventricle during fetal development14. Additionally, increased pressure in the left atrium can lead to the reversal of blood flow into the right atrium through the foramen ovale and into the right ventricle, which can become hypertrophic15. The resulting decrease in left ventricular pressure triggers hypoplasia of the left heart. Alternatively, mitral valve atresia or stenosis can lead to decreased preload in the left ventricle, causing hypoplasia14.

A hypoplastic left ventricle is not detrimental during fetal development due to the presence of the ductus arteriosus which diverts most of the cardiac output into the aorta, maintaining coronary and systemic circulations and perfusion pressures. At birth, the ductus arteriosus and foramen ovale simultaneously close, completely separating the left heart structures and systemic circulation from the right side and the pulmonary circulation. Inadequate systemic perfusion will trigger an increase in the cardiac output as a compensatory mechanism 16. In addition, about 22% of patients with HLHS also possess some degree of atrial septal defects that restrict pulmonary blood flow resulting in pulmonary hypertension1. Nonetheless, these compensatory mechanisms fail after birth leading to metabolic acidosis, tissue ischemia, and cyanosis in the newborn17. HLHS has poor prognosis, with symptoms appearing as early as one day after birth. Untreated patients die within the first couple of weeks, with 70% of deaths occurring within the first week of life1.

4. Molecular Mechanisms Underlying HLHS

HLHS is a multi-factorial defect caused by genetic mutations, abnormal mechanical stimulation, and aberrant cell signaling. Given its multi-factorial origin and lack of relevant animal models, the molecular mechanism of HLHS remains largely obscure. Here, we discuss some of the genetic defects that have been implicated in the HLHS development.

4.1. Genetic Defects Underlying HLHS

Work by Liu et al. suggests a digenic etiology where the combined knockout of Sap130 and Pcdha9 is sufficient to cause HLHS-like phenotypes in mice. They showed that Sap130 is required for cardiomyocyte proliferation, whereas protocadherin 9 (Pcdha9) promotes proper valve formation18. It is not surprising to find gene mutations that can cause defective cardiomyocyte proliferation; however, in their digenic model, the combined deletion of Sap130 and Pcdha9 also resulted in a significant proportion of the litter having congenital heart defects (CHDs), as well as ventricular hypoplasia. However, none of the mice develop the multiple phenotypes associated with HLHS. This calls into question the specificity of their animal model for HLHS, but also highlights the necessity of more extensive genetic screening to potentially uncover HLHS-specific mutations. Despite the lack of specificity, this animal model is proof that genetic defects are sufficient to cause complex CHDs. To date, there is no animal model for HLHS, which highlights (1) the complex etiology of HLHS and (2) the necessity to generate animal models to better understand disease onset and progression.

Nonetheless, deregulation of signaling pathways have been implicated in HLHS. For instance, Notch signaling is required for epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and subsequent early cardiogenesis and chamber formation19, 20. Additionally, Notch signaling promotes the differentiation of cardiac valves via its effectors Hes Related Family BHLH Transcription Factor With YRPW Motif (HEY)1 and HEY2 21. As such, defects in the Notch signaling pathway have been implicated in the development of HLHS. HLHS patient-derived human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) also displayed impaired nitric oxide (NO) signaling which was attributed to a deficient Notch1 signaling pathway22. Human HLHS-iPSCs possess a reduced ability to give rise to mature cardiomyocytes that displayed disorganized sarcomeres and reduced beating rate, indicating a genetic basis for HLHS etiology. The reduction in cardiomyocyte came at the expense of cells displaying smooth muscle cell markers23. This altered cell fate has in vivo consequences as it can perturb proper hemodynamics needed for the development of the left ventricle and valves. Multiple studies have shown a strong association between the defective Notch signaling and HLHS23–26. In fact, deleterious variants of all 4 Notch receptors (Notch1-4) were observed in patients with HLHS23. Intriguingly, activating Notch signaling by exogenous Jagged ligand restored the normal beating rate of defective cardiomyocytes23. It is known that Notch signaling promotes the expression of cardiomyocyte markers in mice, a property that appears to be conserved in humans27. An HLHS patient with a compound heterozygous mutation (P1964L and P1256L) for NOTCH1 had decreased expression of the receptor which led to semilunar valve malformation and impaired cardiomyocyte differentiation and myofilament organization. The Notch defect was sufficient to induce HLHS in this patient26. Thus, defective Notch signaling appears to be a characteristic of HLHS.

Other disease-associated genetic variants have also been observed in patients with HLHS, such as in Calcium Voltage-Gated Channel subunits (CACN)23. Next-generation sequencing on patients with HLHS revealed an enrichment for defected myosin heavy chain 6 (MYH6) variants. iPSCs derived from these patients showed decreased cardiomyogenic potential and an altered gene expression profile24. Moreover, connexin 43 (GJA1) expression has been shown to be reduced in HLHS cardiomyocytes28, which is necessary to establish proper electrical signaling between cardiomyocytes and promotes maturation and alignment during cardiogenesis29.

It was previously shown that NKX2-5 and HAND1 are required for the development of the left ventricle25. Moreover, NOTCH1, NKX2-5, and HAND1 were shown to synergistically activate the expression of SRE, TNNT2, and NPPA25. Mutations in both NKX2-5 and HAND1 have been reported in HLHS patients and patient-derived iPSCs. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses revealed an increase in inhibitory H3K27me3 marks on the NKX2-5 promoter, at the expense of a reduction in H3K4me2 marks, which promote transcriptional activation25. This suggests that epigenetics could be an underlying cause in HLHS phenotype and should be further examined in future studies.

In addition to single gene mutation, chromosomal deletions have also been shown to cause CHDs. In particular, patients with Jacobsen syndrome, a chromosomal disorder characterized by the deletion of the distal end of chromosome 11q, often develop serious CHDs, 5–10% of which are HLHS30. Ye et al. showed that deleting ETS-1, a gene found in the distal end of chromosome 11, leads to the development of ventricular septal defects and a non-apex forming LV, a characteristic of HLHS hearts30. This not only highlights the role of ETS-1 in proper cardiogenesis, but also shows that HLHS is a more complex defect that is the result of several contributing factors. Table 1 summarizes some of the genes/chromosomal disorders that have been associated with HLHS directly, or a CHD commonly present in HLHS hearts.

Table 1:

Gene Mutations and Chromosomal Abnormalities Associated with HLHS

| Gene | Model | Phenotype |

|---|---|---|

| Sap130 1 | Mouse and zebrafish | Left ventricular hyperplasia |

| PCHDA13 1 | Mouse and zebrafish | Aortic valve abnormalities |

| NOTCH1-4 2 | Human iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte | Semilunar valve |

| CACN 3 | Human HLHS iPSC | Impaired myogenic potential |

| MYH6 4 | Human HLHS iPSC | Defective cardiomyogenic differentiation |

| Connexin 43/GJA15 | Human heart tissue | HLHS patients with R362G and R376G mutations in GJA1 gene |

| NKX2.5 6 | Human | Atrial septal defect, patent foramen ovale, HLHS, |

| TBX5 7 | Mouse | Hypoplastic LV |

| FOXC1/FOXC2 8 | Human | HLHS |

| PECAM-1 9 | Human | Disorganized bundles of myocytes, scarce cytoplasm in cardiomyocytes ectopic expression of PECAM-1 in cardiomyocytes, expression of fetal isoform of some cardiac proteins |

| ETS1 10 | Human | Non-apex forming left ventricle |

| 10q22 11 | Human | Bicuspid aortic valve |

| 6q23 11 | Human | Bicuspid aortic valve |

| HAND1 12 | Human HLHS iPSC-derived cardiac progenitor cells | HLHS |

| ERBB4 13 | Mouse | Left ventricular outflow tract |

| GATA4 14 | Human | Atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, HLHS |

| PTPRM 15 | Human | Cardiac development |

| Jacobsen. 11q deletion 16 | Human | HLHS |

4.2. Mechanotransduction and Blood Flow

Cells have the ability to directly respond to mechanical stimuli through mechanotransduction that converts physical forces into a biochemical response. Many diseases are associated with abnormal mechanotransduction, including cardiomyopathies, atherosclerosis, and cancers31. Prevailing hypotheses for the developmental onset of HLHS focus on the role of hemodynamics during the heart development. Proper blood flow through the developing heart is instrumental in producing mechanical stimuli that are necessary to activate the cellular pathways that ensure normal cardiogenesis.

Proper hemodynamics are necessary for the heart development and ventricle formation32. Mechanosensitive proteins have been shown to play a role in establishing proper hemodynamic flow. For instance, Kruppel-like factor 2 (Klf2), a bonafide mechanosensitive protein, was shown to be upregulated in response to changes in blood flow and shear forces in the developing valves and endocardium in a zebrafish model, which is needed for their proper development33, 34. Mechanical flow forces are causal to the expression of Klf2, as the morpholino-mediated knockdown of Klf2 lead to defective valve formation in chicken35. Moreover, the expression of endothelin-1 (ET-1) and nitric oxide synthase (NO)-3 have been linked to shear stress in multiple regions of the heart, including the cardiac outflow tract and in the developing chicken heart35. Both Klf2 and ET-1 are needed for proper cardiogenesis36, 37.

Li et al. conducted a large forward genetic screen to identify genes associated with CHDs. They recovered 218 mouse models for various CHDs, including left ventricular hypoplasia. Interestingly, they found the majority of those mutations occurred in cilia, which are important Hedgehog signaling centers involved in the mechanosensation as well as the left-right patterning and differentiation of the heart. Although they did not specify which mutations led to HLHS-like phenotypes, they identified genes whose mutations led to atrioventricular septal defect (ASD) and outflow tract septation defect (Shh) and bicuspid aortic valve (Exoc5)38. Sonic hedgehog signaling is required to induce the expression of Nkx2.5, whose mutation is associated with HLHS39. Additional ciliary mutations in Filamentin-A, Dachsous1, and DAZ Interacting Zinc Finger Protein 1 have been associated with mitral valve prolapse40–43. Although these genes may not be directly causative to HLHS, patients with HLHS often possess these co-morbidities that may predispose them to HLHS due to hemodynamic disturbances. Moreover, primary cilia are involved in heart development through mechanotransduction44, 45.

Based on the information presented in this section, we suggest a feedback mechanism whereby the expression of mechanosensitive genes during early cardiac development promote the expression of transcription factors and structural proteins that are needed for proper cardiogenesis. This in turn, maintains appropriate hemodynamic flow that provides the mechanical stimuli to ensure the correct modeling of the developing myocardium.

4.3. Contribution by Non-cardiomyocytes in the Heart

Other cardiac cell types besides cardiomyocytes are also instrumental for proper cardiogenesis, including endocardial cells, fibroblasts, and epicardial cells. These cells provide necessary signals that direct different aspects of the heart development and cardiomyocyte maturation. Endocardial cells are a source of mesenchymal cells that contribute to parts of the valves and septa of the heart46. Moreover, they produce signals that mediate the trabeculation of the chambers during development21, 47. This cell population was shown to be reduced in patients with HLHS48. Recently, Miao et al. characterized an impaired endocardial cell population in HLHS patients using single cell RNA sequencing and showed that several transcription factors were downregulated in patient iPSC derived endocardial cells compared to controls such as ETS proto-oncogene 1 (ETS1), which is known to be associated with HLHS30. Additionally, chromatin remodelers such as Chromodomain-helicase-DNA-binding including protein (CHD7) were also downregulated49. Fibronectin 1 (FN1) was downstream of the ETS1 in the endocardium, which decreased cardiomyocyte proliferation and possibly contributed to the ventricular hypoplasia49, 50. More studies are needed to assess the roles of non-cardiomyocyte cell populations in CHDs.

4.4. Placental Abnormalities in HLHS

Recent studies have begun to address whether placental abnormalities could also contribute to CHDs, including HLHS. A study by Jones et al. showed a correlation between impaired placental vasculature and HLHS. They found that HLHS fetuses have immature terminal villi, diminished villous vasculature, and reduced overall placental weight51. Using RNA-sequencing and cluster analysis, they identified several key pathways to be deregulated in HLHS fetuses, including those involved in muscle development, heart looping, and left/right patterning51. Another study showed that fetuses at 11–13 weeks of gestation with CHDs, particularly those with valve defects, were shown to have decreased placental growth factor (PlGF) compared to normal fetuses52. PlGF promotes the proliferation and differentiation of endothelial cells53, 54. In addition, fetuses with CHDs developed in an overall anti-angiogenic environment, as they showed elevated levels of fms-like tyrosine kinase-1 (sFLT-1), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and PlGF antagonist throughout the second and third trimesters55. Moreover, they displayed higher levels of markers of chronic hypoxia such as hypoxia inducible factor (HIF)-2a55. Another manifestation of placental dysfunction is the reduced transport of glucose to the developing heart56. Whether fetuses with CHDs also have lower glucose levels in the heart is not well known and requires further studies. In summary, it is critical to assess the relationship between placental defects and CHDs, and whether these defects are causal to HLHS or a comorbidity associated with common deregulated pathways.

5. Current Therapy for HLHS

5.1. Standard 3-stage palliation

The most common treatment for HLHS consists of three consecutive procedures done within the first 4 years of life: the Norwood, Glenn, and Fontan procedures. In brief, the Norwood procedure creates a new systemic circuit in the heart by redirecting blood from the left atrium into the right ventricle and connecting the aorta to the main pulmonary artery via a BT or Sano shunt57, 58. This leads to the mixing of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood in the right ventricle. Despite this connection, pulmonary and systemic circulations are still in parallel. The Glenn procedure separates the superior vena cava from the RA and connects it directly to the pulmonary artery to be taken to the lungs while the inferior vena cava remains connected to the RA. Finally, the Fontan procedure joins the superior and inferior venae cavae to the pulmonary trunk which is separated from the right ventricle, joining the left and right atria, and connecting the aorta to the right ventricle59. At the end of these procedures, the right heart would be solely responsible for the systemic circulation, with the venae cavae emptying directly into the pulmonary artery. A fenestration between the inferior vena cava and the RA remain to help reduce pressure to the lungs while they adjust to the new circulation. At the end of the Fontan procedure, oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor continue to mix in the single-ventricle heart, while the pulmonary and systemic circulations are effectively in series.

5.2. Complications with Fontan surgery

Although the 3 surgeries performed for HLHS patients are palliative, they do provide patients with a functional systemic circulation that can greatly improve their quality of life. However, the extensive rearrangement of the cardiovascular anatomy can have unfavorable complications in many patients. The high pressure in the RV eventually triggers hypertrophy, dilation, and subsequent hypocontractility. In some cases, dilation of the RV leads to arrhythmia and stasis, predisposing the patient to increased risk of blood clot formation. Coronary blood supply may be compromised due to the high pressure in the right atrium60. Coronary veins drain directly into the RA. This continuous flow is predominantly powered by the pressure difference between the veins and RA (higher pressure in veins compared to RA)61. Elevated pressure in the RA, a consequence of Fontan palliation in some patients, could lead to reduced drainage into the RA. This increases the risk of clots and potential myocardium infarction62, 63. Moreover, initial pulmonary artery hypotension leads to increased pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR), which feedbacks to the increased RV contractility, despite the low cardiac output from the single ventricle supplies the systemic circulation. Persistent elevation of pulmonary vascular resistance further exacerbates ventricular hypertrophy and potential arrhythmias64. Thus, the use of drugs designed for patients with pulmonary hypertension in Fontan patients has shown promising results.

Additionally, congestive heart failure can develop due to chronic low cardiac output which can lead to complications in the liver65. Congestive heart failure in failing Fontan circulations leads to elevated sinusoidal pressure in the liver which in turn causes cirrhosis and portal venous hypertension. In some cases, hepatic dysfunction may also result in hepatic encephalopathy66. Hepatic congestion also increases the risk of pulmonary embolisms and strokes, which is the leading cause of complication-related death in Fontan patients63, 64. Furthermore, elevated venous pressure can lead to increased lymphatic pressure which results in lymphedema and chylothorax63.

Despite the potential complications that can ensue, Fontan palliation remains the most effective procedure to provide an adequate quality of life for patients with HLHS. It is essential for physicians and caretakers to detect these complications as they develop to intervene and maximize the patients’ post-operative recovery. Nonetheless, this underscores the importance of translational research to develop and test pharmacological and other forms of treatment to minimize the occurrence of these complications, and to optimize patient quality of life.

6. On-going Research and Clinical Trials in HLHS

Given the limited regenerative capacity of the mature heart, surgery remains the most viable option to treat HLHS postnatally. Multiple clinical trials are underway that utilize different approaches to treat HLHS, typically in combination with surgery. These include cell-based therapies, valvuloplasty, pharmaceutical agents, and oxygenation treatments. These trials are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2:

Clinical Trials involving HLHS

| Name | Year | Study Design | Treatment Type | Route of Administration (if applicable) | Timing/Duration | Status | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoCell-S2 | 2020 | Non-randomized, controlled, Phase II | Autologous Umbilical Cord Blood Derived Mononuclear Cells | Intra-myocardial | During stage II (Glenn) procedure | On-going | NCT03779711 |

| Safety Study of Autologous Cord Blood Stem Cell Treatment in Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome Patients Undergoing the Norwood Heart Operation | 2018 | Single group, Phase I | Autologous Umbilical Cord Blood Derived Mononuclear Cells | Intra-coronary | During stage I (Norwood) procedure | NCT03431480 | |

| CHILD | 2018 | Randomized, controlled, Phase I | ckit+ cardiac stem cells | Intra-myocardial | During stage II (Glenn) procedure | On-going | NCT03406884 |

| ELPIS | 2018 | Randomized, controlled, Phase I/II | Allogenic MSCs | Intra-myocardial | During stage II (Glenn) procedure | On-going | NCT03525418 |

| Mesoblast Stem Cell Therapy for Patients With Single Ventricle and Borderline Left Ventricle | 2017 | Randomized, controlled, Phase I/II | Allogenic mesenchymal progenitor cells | Intra-endocardial | After bidirectional stage II (Glenn) procedure | On-going | NCT03079401 |

| TICAP | 2011 | Non-randomized, controlled, Phase I | Autologous cardiac progenitor cells | Intra-coronary | 1 month after stage III (Fontan) procedure | Completed |

NCT01273857 (Ishigami et al., 2015) |

| PERSEUS | 2013 | Randomized, controlled, Phase II | Autologous cardiac progenitor cells | Intra-coronary | 4 months after palliation | Completed |

NCT01829750 (Ishigami et al., 2017) |

| APOLLON | 2016 | Randomized, controlled, Phase III | Autologous cardiac progenitor cells | Intra-coronary | After stage II (Glenn) or stage III (Fontan) procedures | On-going | NCT02781922 |

| Fetal Intervention for Aortic Stenosis and Evolving Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome | 2012 | Non-randomized, controlled | In utero balloon valvuloplasty | N/A | Around 18 weeks’ gestation | On-going | NCT01736956 |

| Use of Oxandrolone to Promote Growth in Infants with Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome: A Phase I/II Pilot Study | 2019 | Randomized, controlled, Phase I/II | Oxandrolone | Oral | After stage I (Norwood) procedure | On-going | NCT04090697 |

| SAFO | 2007 | Randomized, controlled, Phase II | Sildenafil | Oral | After stage III (Fontan) procedure | Completed | NCT00507819 |

| Safety, Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Hemodynamic Effects of Ambrisentan in Single Ventricle Pediatric Patients | 2015 | Randomized, controlled, Phase II | Ambrisentan | Oral | After stage III (Fontan) procedure | Completed | NCT02080637 |

| TEMPO | 2011 | Randomized, controlled, Phase II | Bosentan | Oral | After stage III (Fontan) procedure | Completed |

NCT01292551 (Hebert et al., 2014) |

| MATCH | 2017 | Non-randomized, Phase I/II | Chronic hyperoxygenation | Nasal prongs | During second and third trimesters of pregnancy | On-going | NCT03136835 |

| Cardiovascular Response to Maternal Hyperoxygenation in Fetal Congenital Heart Disease | 2016 | Non-randomized | Acute hyperoxygenation | Face mask | Various gestational times | On-going | NCT03147014 |

6.1. Cell-Based Therapies

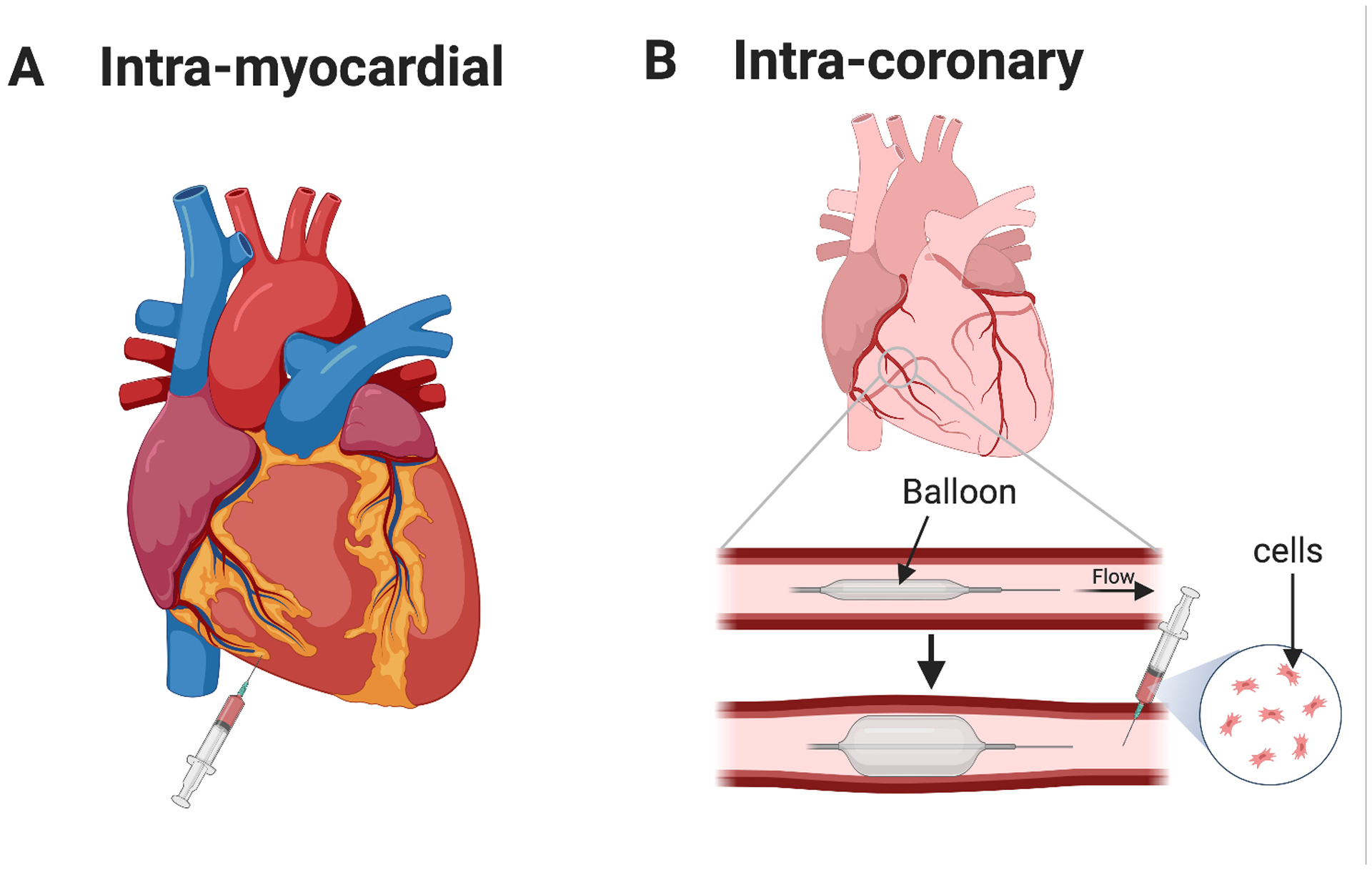

Cell-based therapies have shown promising results in early trials for other CHDs such as dilated cardiomyopathies and myocardial infarction, yet their use in HLHS is still limited. Many of the ongoing clinical trials focus on improving the function of right ventricle following surgery. For instance, the injection of autologous umbilical cord-derived blood cells to the right ventricle is being assessed to increase quality of life, improve ventricular function, and reduce scarring post-surgery (Figure 2B, AutoCell-S2, NCT03779711; NCT01883076; NCT01856049). Another study is assessing the use of these cells via intracoronary injection during Norwood procedures (Figure 2A, NCT03431480). Several clinical trials have utilized mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) for their potential to differentiate into most mesodermal lineages, including muscle and endothelial cells. Moreover, MSCs have low immunogenicity due to their reduced major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and lack of expression of MHC II co-stimulatory molecules. Clinical trials using MSCs have consistently shown that the treatment improves left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and ventricular arrythmias following myocardial infarction67. Allogenic Longeron MSCs are being tested as an adjunct therapy during Glenn procedure in a similar manner to the studies mentioned above (ELPIS, NCT03525418). Although autologous MSCs could be a better approach to minimize a potential immune reaction, allogenic MSCs may provide an alternative cell source when the fetus has a genetic mutation that partly underlies the HLHS phenotype. Another advantage of using allogenic MSCs is the commercialization of the treatment, which overcomes the cost and time required to generate autologous MSCs. Other studies are also utilizing MSCs alongside surgery (NCT03079401).

Figure 2: Modes of administration.

(A) Intra-myocardial injection of cells (or vector) into the myocardium of the right ventricle. (B) Intra-coronary administration of cells. A balloon catheter is inserted into the coronary artery and inflated posterior to the site of injection to temporary stop blood flow. Cells (or vector) are then injected anterior to the balloon, and blood flow is restored.

The CHILD phase I trial (NCT03406884) will assess the safety of injecting autologous c-kit+ cells into the RV during the Glenn procedure and evaluate their effect on myocardial function, tricuspid regurgitation, and heart failure. Alternatively, the TICAP trial (Transcoronary Infusion of CPCs in Patients with Single Ventricle Physiology, NCT01273857) was a phase I clinical trial that aimed to assess the safety and feasibility of intracoronary injection of autologous cardiac progenitor cells (CPCs) 1 month after standard HLHS surgeries were performed. After 18 months of injection, patients who received the treatment showed improved right ventricular ejection fraction, reduction in tricuspid valve annulus, reduction in normalized end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes, and overall improved growth demonstrated by increase in height and weights. These changes were not observed in control patients who only received surgeries but no cell treatment68. This study was followed by the PERSEUS phase II trial which also showed improved RV function and quality of life in patients who received CPCs after a 3-year follow-up (Cardiac Progenitor Cell Infusion to Treat Univentricular Heart Disease, NCT01829750)69. The APOLLON trial is a phase III continuation of these studies that is currently underway (Cardiac Stem/Progenitor Cell Infusion in Univentricular Physiology, NCT02781922).

6.2. Valvuloplasty

With evolving technologies, congenital defects can now be detected in utero with better precision than in the past. These advances open the possibility of earlier intervention which allow the manipulation of the heart during cardiogenesis. A current trial aims to evaluate the efficacy and safety of in utero balloon aortic valvuloplasty in fetuses with severe aortic stenosis (NCT01736956). Aortic stenosis during mid-gestation often evolves into HLHS70. Aortic angioplasty is uncommon in utero but can potentially improve blood flow in the left ventricle which could promote proper chamber development, as well as improve the outcomes of biventricular repair (BVR) surgery after birth. It is worth noting that this prospective study is limited to fetuses with severe aortic stenosis that have not yet developed into HLHS. Intrauterine balloon valvuloplasty would be ineffective if HLHS has already developed in utero. BVR in this case would not be a substitute for standard palliation, but in patients who are high risk for neonatal reconstruction, BVR may improve their chance of survival71. This highlights the importance of early detection of CHDs and intervention to allow better treatment options and prognosis after surgery.

6.3. Pharmacological therapies

In addition to the surgical palliation and cell-based therapy, the use of pharmacological agents, in combination with other treatments, is a potential strategy to further improve cardiac function in HLHS. A study has shown that the use of oxandrolone, an anabolic steroid, in neonates suffering from complex CHD and have underwent the Norwood procedure, significantly reduced weight decline after surgery for the duration of study72. This study is currently being expanded into phase I/II trials and specifically target HLHS neonates (NCT04090697). Pulmonary vasodilators have shown to consistently improve hemodynamics in patients who develop high PVR after having underwent Fontan surgery, including HLHS patients73. A study has shown that the administration of 20 mg of Sildenafil, a phosphodiesterase inhibitor used to treat pulmonary hypertension, significantly improved minute ventilation in children who received Fontan surgery (SAFO, NCT00507819). However, they did not see a significant change in heart rate or oxygen consumption. Moreover, oral administration of Ambrisentan, an endothelin receptor antagonist, significantly lowered the PVR in HLHS following Fontan procedure (NCT02080637). Similar to Ambrisentan, Bosentan improved hemodynamics in patients with single ventricle physiology and reduced PVR and pulmonary arterial hypertension74, 75. Additionally, Bosentan significantly improved peak oxygen consumption and cardiopulmonary exercise capacity in Fontan patients (TEMPO, NCT01292551)76. Lowering PVR in Fontan patients has been shown to improve survival and quality of life after surgery77. However, not all Fontan patients develop high PVR. Thus, these treatments would be targeted towards patients that develop pulmonary arterial hypertension and high PVR. It is important to identify specific subgroups within Fontan patients who may benefit from such treatments. Nonetheless, whether these treatments provide long-term benefits to Fontan patients is yet to be determined.

6.4. Hyperoxygenation

As described earlier, mid-gestation fetuses with CHDs expressed higher levels of hypoxia markers such as HIF-2a55. A phase I/II study (MATCH, NCT03136835) aims to assess the feasibility of chronic hyperoxygenation during pregnancies with HLHS and aortic arch obstruction. Although this study aims to look at the neurodevelopmental outcome of this treatment, the higher oxygen levels may also improve heart and vascular development in these fetuses. Another study aims to evaluate the cardiovascular function in response to a short 10–15 min maternal hyperoxygenation treatment in fetuses with CHDs. Fetal hearts will be assessed for several study parameters via echocardiography (NCT03147014).

7. Conclusion

Since the development of the Norwood procedure, great progress has been made in understanding HLHS etiology and pathology. This has led to the development of multiple therapeutic strategies that are being clinically tested. These range from surgical intervention to cell-based therapy to pharmacological agents. Complications associated with Fontan surgery necessitate the development of adequate combinational treatments to improve post-operative care and quality of life. However, given the complexity of the disease, more translational research and clinical trials are needed in the hopes of achieving comparable quality of life to that of non-HLHS individuals.

8. Expert Opinion

HLHS is a multi-factorial disease that can be caused by several mechanisms. Although we have a general understanding of disease progression, the initial trigger can be quite obscure and different depending on the individual patient. We propose that HLHS is triggered by the dysregulation of key signaling pathways during heart development, either directly through mutation, in response to an environmental stimulus in utero, or both, that in turn, disrupt the mechanotransduction in the developing heart. The disruption of mechanosensation prevents the expression of necessary structural and signaling proteins needed to promote correct heart morphology during development leading to hemodynamic changes that further exacerbate the disease phenotype.

Although HLHS is not an exclusively heritable disease, multiple studies have implicated a genetic contribution18, 78. Disease-associated gene variants have been identified in HLHS patients. These variants occur in genes involved in major developmental pathways such as Notch, as well as in structural components that are crucial for cardiomyocyte function such as myosin22–24, 26, 49. The enrichment of the variants in transcription factors and chromatin remodelers is also an interesting direction to pursue. The genetic basis for CHDs and HLHS opens new avenues for research and treatment. It is important that future studies assess whether these variants are causal to HLHS or whether multiple co-existing factors are needed to trigger the onset of HLHS. A comprehensive assessment of the biochemical consequence of these variants is required to generate adequate mouse models that recapitulate the phenotypes seen in human patients. Given our current understanding of HLHS, it is unlikely that a single gene mutation is sufficient to cause HLHS. The most likely scenario is that disease-associated mutations may trigger a cascade of events that collectively lead to HLHS. If a causal relationship is indeed the case, gene therapy may be a viable option for treatment in utero, especially in families that are known to carry such variants. Gene therapy consists of introducing a DNA construct carrying a therapeutic gene in the form of a plasmid, adenovirus, or adeno-associated vector (AAV). AAV vectors are being tested in clinically relevant models, as well as in several clinical trials for different heart conditions in adults79, 80. Intra-coronary injection of a high dose of AAV vectors successfully inserted into 12% of cardiomyocytes81. Whether this approach is sufficient to improve heart development in utero is not known. This highlights the importance of developing good animal models of HLHS. Combined with improving the ability to detect HLHS phenotypes in utero, it would be interesting to see whether gene therapy could tip the scale towards a less severe defect. Although gene therapy is a potentially powerful clinical intervention, there are many precautions that need to be considered. For instance, transgenes are integrated randomly in the genome, where they could be potentially insert in gene bodies. Additionally, successfully integrated transgenes are often expressed continuously, which may exclude them from regulatory mechanisms that normally regulate the endogenous gene. Appropriately, newer constructs that can be regulated have been developed for new gene therapy approaches. Another limitation of gene therapy is the ability to target the vector to specific cell types, where the insertion of a transgene into nonspecific cell types can have a negative impact on the function of those cells.

One of the biggest limitations of the translational research in HLHS is the lack of availability of experimental animal models. Liu et al. developed a bigenic model for CHDs18. Although their model failed to phenocopy HLHS, it could still be useful to understand disease mechanisms of other CHDs and provide a model to test experimental therapies prior to clinical trials. Animal studies could provide insight into the long-term effects and efficacy of potential therapies.

Despite the lack of specific animal models to study the disease progression, several research techniques are being used to study HLHS. Other experimental modalities provide great insight into some of the cell-intrinsic defects and signaling of cardiomyocytes and other cell types and elucidate their contribution to HLHS. The use of patient-derived iPSCs has allowed us to study the physiology of defective cardiomyocytes in vitro and greatly improved our understanding of HLHS22–25, 30.

Over the past few decades, organoid research has provided great insight into many aspects of disorders that 2D cultures fail to recapitulate. These include tissue-specific phenotypes, cell-matrix interactions, and cell polarity. Although cardiac organoids, or cardioids, are a more faithful model to assess cardiomyocyte function and beating properties, the effect of hemodynamics, which plays a vital role in heart development and remodeling, cannot be assessed. Regardless, HLHS patient-derived cardioids may provide important information on disease development. Drakhlis et al. developed a method to generate cardioids that resemble early-stage cardiogenesis using human iPSCs82. They use these organoids to show that the knockout of NKX2-5 leads to cardiomyocyte hypertrophy and decreased adhesion, similar to the phenotype observed with conditional knockout in mice. Additionally, cardiac organoids can be used for large-scale drug screening. Mills et al. used human cardioids to screen for 105 small molecules that potentially promote heart regeneration83. They were able to identify two small molecules that promote proliferation of the cardioids. They also showed that the mevalonate pathway promoted cardiomyocyte proliferation. Despite the difficulty to recapitulate hemodynamic stimuli in cardioids, Hofbauer et al. developed self-assembling cardioids with chamber-like structures and showed that HAND1 is required for chamber formation84. These studies, and others, highlight the potential of using human cardiac organoids to uncover transcription factors and pathways important in cardiogenesis, model patient-specific phenotypes, and test potential therapies and drugs that may be useful to promote cardiac regeneration. Engineering cardioid complexity is necessary to understand the interplay between different cell types in the developing heart.

When opting for cell-based therapies, it is important to consider the timing and mode of administration of the cells. Much of the cell-based therapies discussed here are administered during or after the Glenn procedure, as opposed to earlier times. Patients receiving a treatment of cardiac progenitor cells (TICAP) at 1 year of age showed a better improvement of RVEF compared to those receiving the treatment at 3 years of age, combined with surgery68, 85. One of the limiting factors of experimental treatments between stage I and II procedures is the high mortality rate associated with these procedures. In fact, the majority of death in patients with single-ventricle phenotypes, such as HLHS, occurs between the Norwood and Glenn procedures86. This high mortality rate makes it more difficult to assess the feasibility and safety of experimental treatments at an earlier intervention point. Regarding the mode of administration, both intramyocardial and intracoronary injections have been utilized in clinical trials (Figure 2). A major determinant regarding which method is optimal is the cell size. MSCs for example, should be administered intramyocardially, as their large size has been shown to occlude capillaries in the heart87.

Cell-based therapies could improve heart function in patients with HLHS based on the results from several ongoing clinical trials. Many of these cells exert their effect through their secretome that modulates different cell types in the heart88, 89. It would be interesting to further understand the effect of different secretome-derived molecules during palliation, as well as the mechanisms through which these molecules act to improve heart function. This would provide novel targets and intracellular pathways to which pharmacological agents could be designed for.

With advances in precision medicine and technology, early detection and intervention are the best strategies to achieve optimal outcome for heart regeneration in HLHS. The heart continues to develop after birth in response to the changes in blood pressure90. The plasticity of the developing heart can potentially be leveraged to direct its growth towards a normal physiology. More studies and trials are needed to fine-tune and optimize the type and timing of treatment to achieve optimum myocardial protection of the RV or improvement of LV in the case if BVR surgery. It is unlikely that a single gene or pathway can be targeted pharmacologically; however, combinatorial approaches will likely produce better quality of life and minimize surgery-related complications in patients with HLHS.

Although achieving heart regeneration is not a realistic goal, improving heart function and minimizing post-Fontan complications in HLHS patients remains the best therapeutic approach. It is without a doubt that HLHS is a very complex, multifactorial disease, and our lack of understanding of its etiology is evident. One of the biggest challenges hindering the development of efficient therapies is our limited understanding of HLHS onset and the impact that individual genetics play in disease progression and post-surgical outcomes. In terms of research and drug testing, a major limitation is the lack of availability of animal models for HLHS. Although the models reviewed here recapitulate many phenotypes observed in HLHS, their specificity remains questionable. Nonetheless, our understanding of HLHS has greatly improved since it was first characterized. Ultimately, research in HLHS should focus on developing good animal models which would allow novel therapies to be envisioned.

Article Highlights:

HLHS is a rare, multifactorial disorder characterized predominantly by the underdevelopment of the left ventricle.

Although not exclusively a genetic disorder, disease-related genes have been identified to contribute to HLHS.

Disruptions in hemodynamics and mechanosensation are the main drivers of disease progression.

There are currently no experimental animal models for HLHS, limiting research in the field.

Several clinical trials, including cell therapy, are underway to test different approaches that can potentially improve patient outcomes after surgery.

New and innovative patient-specific approaches to study HLHS should be used to better understand disease progression and develop therapies that address the wide range of phenotypic abnormalities encompassing HLHS.

Funding

This paper was funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; R00 HL135258

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

Reviewer disclosures

Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest (•) or of considerable interest (••) to readers

- 1.Fruitman DS. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: Prognosis and management options. Paediatr Child Health 2000. May;5(4):219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCormick AD, Schumacher KR. Transplantation of the failing Fontan. Transl Pediatr 2019. October;8(4):290–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baffa JM, Chen SL, Guttenberg ME, Norwood WI, Weinberg PM. Coronary artery abnormalities and right ventricular histology in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 1992. August;20(2):350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crucean A, Alqahtani A, Barron DJ, et al. Re-evaluation of hypoplastic left heart syndrome from a developmental and morphological perspective. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017. August 10;12(1):138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang A, Qureshi MY, Kelle A, et al. Effect of Left Ventricular Morphology on Right Ventricular Systolic Function in Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Pediatrics 2020. 2020-07-01 00:00:00;146:631–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghelani SJ, Colan SD, Azcue N, et al. Impact of Ventricular Morphology on Fiber Stress and Strain in Fontan Patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2018. July;11(7):e006738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson RH, Spicer DE, Crucean A. Clarification of the definition of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021. March;18(3):147–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anderson RH, Smith A, Cook AC. Hypoplasia of the left heart. Cardiol Young 2004. February;14 Suppl 1:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hattam AT. A potentially curative fetal intervention for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Med Hypotheses 2018. January;110:132–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bohlmeyer TJ, Helmke S, Ge S, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome myocytes are differentiated but possess a unique phenotype. Cardiovasc Pathol 2003. Jan-Feb;12(1):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin HS, Shen HM, Yan HC, et al. Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule-1 (PECAM-1/CD31): alternatively spliced, functionally distinct isoforms expressed during mammalian cardiovascular development. Development 1994. September;120(9):2539–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor WN, Cash JB, Cottrill CM, Johnson GL, Noonan JA. Ventriculocoronary connections in hypoplastic left hearts: an autopsy microscopic study. Circulation 1982. November;66(5):1078–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feinstein JA, Benson DW, Dubin AM, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: current considerations and expectations. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012. January 3;59(1 Suppl):S1–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gobergs R, Salputra E, Lubaua I. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: a review. Acta Med Litu 2016;23(2):86–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Frommelt MA. Challenges and controversies in fetal diagnosis and treatment: hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Clin Perinatol 2014. December;41(4):787–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park MK. Pediatric Cardiology for Practitioners E-Book: Elsevier Health Sciences, 2014.

- 17.Physiology Rosenthal A., diagnosis and clinical profile of the hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Progress in Pediatric Cardiology 1996. 1996/02/01/;5(1):19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu X, Yagi H, Saeed S, et al. The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nat Genet 2017. July;49(7):1152–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang AC, Fu Y, Garside VC, et al. Notch initiates the endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition in the atrioventricular canal through autocrine activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase. Dev Cell 2011. August 16;21(2):288–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koenig SN, Bosse K, Majumdar U, Bonachea EM, Radtke F, Garg V. Endothelial Notch1 Is Required for Proper Development of the Semilunar Valves and Cardiac Outflow Tract. J Am Heart Assoc 2016. April 22;5(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de la Pompa JL, Epstein JA. Coordinating tissue interactions: Notch signaling in cardiac development and disease. Dev Cell 2012. February 14;22(2):244–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hrstka SC, Li X, Nelson TJ, Wanek Program Genetics Pipeline G. NOTCH1-Dependent Nitric Oxide Signaling Deficiency in Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome Revealed Through Patient-Specific Phenotypes Detected in Bioengineered Cardiogenesis. Stem Cells 2017. April;35(4):1106–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yang C, Xu Y, Yu M, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell modelling of HLHS underlines the contribution of dysfunctional NOTCH signalling to impaired cardiogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2017. August 15;26(16):3031–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tomita-Mitchell A, Stamm KD, Mahnke DK, et al. Impact of MYH6 variants in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Physiol Genomics 2016. December 1;48(12):912–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kobayashi J, Yoshida M, Tarui S, et al. Directed differentiation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells identifies the transcriptional repression and epigenetic modification of NKX2-5, HAND1, and NOTCH1 in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. PLoS One 2014;9(7):e102796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Theis JL, Hrstka SC, Evans JM, et al. Compound heterozygous NOTCH1 mutations underlie impaired cardiogenesis in a patient with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Hum Genet 2015. September;134(9):1003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder T, Meier-Stiegen F, Schwanbeck R, et al. Activated Notch1 alters differentiation of embryonic stem cells into mesodermal cell lineages at multiple stages of development. Mech Dev 2006. July;123(7):570–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahtab EA, Gittenberger-de Groot AC, Vicente-Steijn R, et al. Disturbed myocardial connexin 43 and N-cadherin expressions in hypoplastic left heart syndrome and borderline left ventricle. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012. December;144(6):1315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Desplantez T, McCain ML, Beauchamp P, et al. Connexin43 ablation in foetal atrial myocytes decreases electrical coupling, partner connexins, and sodium current. Cardiovasc Res 2012. April 1;94(1):58–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ye M, Coldren C, Liang X, et al. Deletion of ETS-1, a gene in the Jacobsen syndrome critical region, causes ventricular septal defects and abnormal ventricular morphology in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2010. February 15;19(4):648–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jaalouk DE, Lammerding J. Mechanotransduction gone awry. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009. January;10(1):63–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boselli F, Freund JB, Vermot J. Blood flow mechanics in cardiovascular development. Cell Mol Life Sci 2015. July;72(13):2545–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vermot J, Forouhar AS, Liebling M, et al. Reversing blood flows act through klf2a to ensure normal valvulogenesis in the developing heart. PLoS Biol 2009. November;7(11):e1000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dietrich AC, Lombardo VA, Veerkamp J, Priller F, Abdelilah-Seyfried S. Blood flow and Bmp signaling control endocardial chamber morphogenesis. Dev Cell 2014. August 25;30(4):367–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Groenendijk BC, Hierck BP, Gittenberger-De Groot AC, Poelmann RE. Development-related changes in the expression of shear stress responsive genes KLF-2, ET-1, and NOS-3 in the developing cardiovascular system of chicken embryos. Dev Dyn 2004. May;230(1):57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Beghetti M, Black SM, Fineman JR. Endothelin-1 in congenital heart disease. Pediatr Res 2005. May;57(5 Pt 2):16R–20R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chiplunkar AR, Lung TK, Alhashem Y, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 is required for normal mouse cardiac development. PLoS One 2013;8(2):e54891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Y, Klena NT, Gabriel GC, et al. Global genetic analysis in mice unveils central role for cilia in congenital heart disease. Nature 2015. May 28;521(7553):520–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang XM, Ramalho-Santos M, McMahon AP. Smoothened mutants reveal redundant roles for Shh and Ihh signaling including regulation of L/R asymmetry by the mouse node. Cell 2001. June 15;105(6):781–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toomer KA, Yu M, Fulmer D, et al. Primary cilia defects causing mitral valve prolapse. Sci Transl Med 2019. May 22;11(493). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dau C, Fliegauf M, Omran H, et al. The atypical cadherin Dachsous1 localizes to the base of the ciliary apparatus in airway epithelia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016. May 13;473(4):1177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Durst R, Sauls K, Peal DS, et al. Mutations in DCHS1 cause mitral valve prolapse. Nature 2015. September 3;525(7567):109–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kyndt F, Gueffet JP, Probst V, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding filamin A as a cause for familial cardiac valvular dystrophy. Circulation 2007. January 2;115(1):40–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garoffolo G, Pesce M. Mechanotransduction in the Cardiovascular System: From Developmental Origins to Homeostasis and Pathology. Cells 2019. December 11;8(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pala R, Jamal M, Alshammari Q, Nauli SM. The Roles of Primary Cilia in Cardiovascular Diseases. Cells 2018. November 27;7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Harris IS, Black BL. Development of the endocardium. Pediatr Cardiol 2010. April;31(3):391–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bressan M, Yang PB, Louie JD, Navetta AM, Garriock RJ, Mikawa T. Reciprocal myocardial-endocardial interactions pattern the delay in atrioventricular junction conduction. Development 2014. November;141(21):4149–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaber N, Gagliardi M, Patel P, et al. Fetal reprogramming and senescence in hypoplastic left heart syndrome and in human pluripotent stem cells during cardiac differentiation. Am J Pathol 2013. September;183(3):720–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Miao Y, Tian L, Martin M, et al. Intrinsic Endocardial Defects Contribute to Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Cell Stem Cell 2020. August 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mittal A, Pulina M, Hou SY, Astrof S. Fibronectin and integrin alpha 5 play requisite roles in cardiac morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2013. September 1;381(1):73–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jones HN, Olbrych SK, Smith KL, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is associated with structural and vascular placental abnormalities and leptin dysregulation. Placenta 2015. October;36(10):1078–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Llurba E, Syngelaki A, Sanchez O, Carreras E, Cabero L, Nicolaides KH. Maternal serum placental growth factor at 11–13 weeks’ gestation and fetal cardiac defects. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2013. August;42(2):169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ziche M, Maglione D, Ribatti D, et al. Placenta growth factor-1 is chemotactic, mitogenic, and angiogenic. Lab Invest 1997. April;76(4):517–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shore VH, Wang TH, Wang CL, Torry RJ, Caudle MR, Torry DS. Vascular endothelial growth factor, placenta growth factor and their receptors in isolated human trophoblast. Placenta 1997. November;18(8):657–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Llurba E, Sanchez O, Ferrer Q, et al. Maternal and foetal angiogenic imbalance in congenital heart defects. Eur Heart J 2014. March;35(11):701–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vannucci RC, Vannucci SJ. Glucose metabolism in the developing brain. Semin Perinatol 2000. April;24(2):107–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Norwood WI, Lang P, Casteneda AR, Campbell DN. Experience with operations for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1981. October;82(4):511–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Norwood WI, Kirklin JK, Sanders SP. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: experience with palliative surgery. Am J Cardiol 1980. January;45(1):87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ohye RG, Schranz D, D’Udekem Y. Current Therapy for Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome and Related Single Ventricle Lesions. Circulation 2016. October 25;134(17):1265–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fredenburg TB, Johnson TR, Cohen MD. The Fontan procedure: anatomy, complications, and manifestations of failure. Radiographics 2011. Mar-Apr;31(2):453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Goodwill AG, Dick GM, Kiel AM, Tune JD. Regulation of Coronary Blood Flow. Compr Physiol 2017. March 16;7(2):321–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monagle P, Karl TR. Thromboembolic problems after the Fontan operation. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg Pediatr Card Surg Annu 2002;5:36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gewillig M The Fontan circulation. Heart 2005. June;91(6):839–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Khambadkone S The Fontan pathway: What’s down the road? Ann Pediatr Cardiol 2008. July;1(2):83–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Deal BJ, Jacobs ML. Management of the failing Fontan circulation. Heart 2012. July;98(14):1098–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kiesewetter CH, Sheron N, Vettukattill JJ, et al. Hepatic changes in the failing Fontan circulation. Heart 2007. May;93(5):579–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jeong H, Yim HW, Park HJ, et al. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Ischemic Heart Disease: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int J Stem Cells 2018. May 30;11(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Tarui S, et al. Intracoronary autologous cardiac progenitor cell transfer in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: the TICAP prospective phase 1 controlled trial. Circ Res 2015. February 13;116(4):653–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Eitoku T, et al. Intracoronary Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Single Ventricle Physiology: The PERSEUS (Cardiac Progenitor Cell Infusion to Treat Univentricular Heart Disease) Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Circ Res 2017. March 31;120(7):1162–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Makikallio K, McElhinney DB, Levine JC, et al. Fetal aortic valve stenosis and the evolution of hypoplastic left heart syndrome: patient selection for fetal intervention. Circulation 2006. March 21;113(11):1401–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Murphy MO, Bellsham-Revell H, Morgan GJ, et al. Hybrid Procedure for Neonates With Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome at High-Risk for Norwood: Midterm Outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2015. December;100(6):2286–90; discussion 91–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Burch PT, Spigarelli MG, Lambert LM, et al. Use of Oxandrolone to Promote Growth in Neonates following Surgery for Complex Congenital Heart Disease: An Open-Label Pilot Trial. Congenit Heart Dis 2016. December;11(6):693–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Castaldi B, Bordin G, Padalino M, Cuppini E, Vida V, Milanesi O. Hemodynamic impact of pulmonary vasodilators on single ventricle physiology. Cardiovasc Ther 2018. February;36(1). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Derk G, Houser L, Miner P, et al. Efficacy of endothelin blockade in adults with Fontan physiology. Congenit Heart Dis 2015. Jan-Feb;10(1):E11–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hirono K, Yoshimura N, Taguchi M, et al. Bosentan induces clinical and hemodynamic improvement in candidates for right-sided heart bypass surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010. August;140(2):346–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hebert A, Mikkelsen UR, Thilen U, et al. Bosentan improves exercise capacity in adolescents and adults after Fontan operation: the TEMPO (Treatment With Endothelin Receptor Antagonist in Fontan Patients, a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study Measuring Peak Oxygen Consumption) study. Circulation 2014. December 2;130(23):2021–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goldberg DJ, Paridon SM. Fontan circulation: the search for targeted therapy. Circulation 2014. December 2;130(23):1999–2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hinton RB Jr., Martin LJ, Tabangin ME, Mazwi ML, Cripe LH, Benson DW. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome is heritable. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007. October 16;50(16):1590–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Katz MG, Fargnoli AS, Weber T, Hajjar RJ, Bridges CR. Use of Adeno-Associated Virus Vector for Cardiac Gene Delivery in Large-Animal Surgical Models of Heart Failure. Hum Gene Ther Clin Dev 2017. September;28(3):157–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cannata A, Ali H, Sinagra G, Giacca M. Gene Therapy for the Heart Lessons Learned and Future Perspectives. Circ Res 2020. May 8;126(10):1394–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kaspar BK, Roth DM, Lai NC, et al. Myocardial gene transfer and long-term expression following intracoronary delivery of adeno-associated virus. J Gene Med 2005. March;7(3):316–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Drakhlis L, Biswanath S, Farr CM, et al. Human heart-forming organoids recapitulate early heart and foregut development. Nat Biotechnol 2021. February 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mills RJ, Parker BL, Quaife-Ryan GA, et al. Drug Screening in Human PSC-Cardiac Organoids Identifies Pro-proliferative Compounds Acting via the Mevalonate Pathway. Cell Stem Cell 2019. June 6;24(6):895–907 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hofbauer P, Jahnel SM, Papai N, et al. Cardioids reveal self-organizing principles of human cardiogenesis. Cell 2021. May 18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tarui S, Ishigami S, Ousaka D, et al. Transcoronary infusion of cardiac progenitor cells in hypoplastic left heart syndrome: Three-year follow-up of the Transcoronary Infusion of Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Patients With Single-Ventricle Physiology (TICAP) trial. The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery 2015. 2015/11/01/;150(5):1198–208.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ohye RG, Schonbeck JV, Eghtesady P, et al. Cause, timing, and location of death in the Single Ventricle Reconstruction trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012. October;144(4):907–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Furlani D, Ugurlucan M, Ong L, et al. Is the intravascular administration of mesenchymal stem cells safe? Mesenchymal stem cells and intravital microscopy. Microvasc Res 2009. May;77(3):370–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ranganath SH, Levy O, Inamdar MS, Karp JM. Harnessing the mesenchymal stem cell secretome for the treatment of cardiovascular disease. Cell Stem Cell 2012. March 2;10(3):244–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sharma S, Mishra R, Bigham GE, et al. A Deep Proteome Analysis Identifies the Complete Secretome as the Functional Unit of Human Cardiac Progenitor Cells. Circ Res 2017. March 3;120(5):816–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Rudolph AM. Myocardial growth before and after birth: clinical implications. Acta Paediatr 2000. February;89(2):129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dasgupta C, Martinez AM, Zuppan CW, Shah MM, Bailey LL, Fletcher WH. Identification of connexin43 (alpha1) gap junction gene mutations in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Mutat Res 2001. August 8;479(1–2):173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Elliott DA, Kirk EP, Yeoh T, et al. Cardiac homeobox gene NKX2-5 mutations and congenital heart disease: associations with atrial septal defect and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003. June 4;41(11):2072–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mori AD, Zhu Y, Vahora I, et al. Tbx5-dependent rheostatic control of cardiac gene expression and morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2006. September 15;297(2):566–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yu S, Shao L, Kilbride H, Zwick DL. Haploinsufficiencies of FOXF1 and FOXC2 genes associated with lethal alveolar capillary dysplasia and congenital heart disease. Am J Med Genet A 2010. May;152A(5):1257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hinton RB, Martin LJ, Rame-Gowda S, Tabangin ME, Cripe LH, Benson DW. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome links to chromosomes 10q and 6q and is genetically related to bicuspid aortic valve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009. March 24;53(12):1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.McBride KL, Zender GA, Fitzgerald-Butt SM, et al. Association of common variants in ERBB4 with congenital left ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2011. Mar;91(3):162–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reamon-Buettner SM, Ciribilli Y, Inga A, Borlak J. A loss-of-function mutation in the binding domain of HAND1 predicts hypoplasia of the human hearts. Hum Mol Genet 2008. May 15;17(10):1397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Carey AS, Liang L, Edwards J, et al. Effect of copy number variants on outcomes for infants with single ventricle heart defects. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013. October;6(5):444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grossfeld PD, Mattina T, Lai Z, et al. The 11q terminal deletion disorder: a prospective study of 110 cases. Am J Med Genet A 2004. August 15;129A(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- 1.Liu X, Yagi H, Saeed S, Bais AS, Gabriel GC, Chen Z, et al. The complex genetics of hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nat Genet 2017. July;49(7):1152–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Theis JL, Hrstka SC, Evans JM, O’Byrne MM, de Andrade M, O’Leary PW, et al. Compound heterozygous NOTCH1 mutations underlie impaired cardiogenesis in a patient with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Hum Genet 2015. September;134(9):1003–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang C, Xu Y, Yu M, Lee D, Alharti S, Hellen N, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell modelling of HLHS underlines the contribution of dysfunctional NOTCH signalling to impaired cardiogenesis. Hum Mol Genet 2017. August 15;26(16):3031–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomita-Mitchell A, Stamm KD, Mahnke DK, Kim MS, Hidestrand PM, Liang HL, et al. Impact of MYH6 variants in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Physiol Genomics 2016. December 1;48(12):912–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasgupta C, Martinez AM, Zuppan CW, Shah MM, Bailey LL, Fletcher WH. Identification of connexin43 (alpha1) gap junction gene mutations in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE). Mutat Res 2001. August 8;479(1–2):173–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elliott DA, Kirk EP, Yeoh T, Chandar S, McKenzie F, Taylor P, et al. Cardiac homeobox gene NKX2-5 mutations and congenital heart disease: associations with atrial septal defect and hypoplastic left heart syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003. June 4;41(11):2072–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori AD, Zhu Y, Vahora I, Nieman B, Koshiba-Takeuchi K, Davidson L, et al. Tbx5-dependent rheostatic control of cardiac gene expression and morphogenesis. Dev Biol 2006. September 15;297(2):566–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu S, Shao L, Kilbride H, Zwick DL. Haploinsufficiencies of FOXF1 and FOXC2 genes associated with lethal alveolar capillary dysplasia and congenital heart disease. Am J Med Genet A 2010. May;152A(5):1257–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bohlmeyer TJ, Helmke S, Ge S, Lynch J, Brodsky G, Sederberg JH, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome myocytes are differentiated but possess a unique phenotype. Cardiovasc Pathol 2003. Jan-Feb;12(1):23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye M, Coldren C, Liang X, Mattina T, Goldmuntz E, Benson DW, et al. Deletion of ETS-1, a gene in the Jacobsen syndrome critical region, causes ventricular septal defects and abnormal ventricular morphology in mice. Hum Mol Genet 2010. February 15;19(4):648–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hinton RB, Martin LJ, Rame-Gowda S, Tabangin ME, Cripe LH, Benson DW. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome links to chromosomes 10q and 6q and is genetically related to bicuspid aortic valve. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009. March 24;53(12):1065–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kobayashi J, Yoshida M, Tarui S, Hirata M, Nagai Y, Kasahara S, et al. Directed differentiation of patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells identifies the transcriptional repression and epigenetic modification of NKX2-5, HAND1, and NOTCH1 in hypoplastic left heart syndrome. PLoS One 2014;9(7):e102796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McBride KL, Zender GA, Fitzgerald-Butt SM, Seagraves NJ, Fernbach SD, Zapata G, et al. Association of common variants in ERBB4 with congenital left ventricular outflow tract obstruction defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2011. March;91(3):162–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reamon-Buettner SM, Ciribilli Y, Inga A, Borlak J. A loss-of-function mutation in the binding domain of HAND1 predicts hypoplasia of the human hearts. Hum Mol Genet 2008. May 15;17(10):1397–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carey AS, Liang L, Edwards J, Brandt T, Mei H, Sharp AJ, et al. Effect of copy number variants on outcomes for infants with single ventricle heart defects. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 2013. October;6(5):444–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grossfeld PD, Mattina T, Lai Z, Favier R, Jones KL, Cotter F, et al. The 11q terminal deletion disorder: a prospective study of 110 cases. Am J Med Genet A 2004. August 15;129A(1):51–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

- Hebert A, Mikkelsen UR, Thilen U, Idorn L, Jensen AS, Nagy E, Hanseus K, Sorensen KE, and Sondergaard L. 2014. Bosentan improves exercise capacity in adolescents and adults after Fontan operation: the TEMPO (Treatment With Endothelin Receptor Antagonist in Fontan Patients, a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled, Double-Blind Study Measuring Peak Oxygen Consumption) study. Circulation. 130:2021–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Eitoku T, Ousaka D, Kondo M, Kurita Y, Hirai K, Fukushima Y, Baba K, Goto T, Horio N, Kobayashi J, Kuroko Y, Kotani Y, Arai S, Iwasaki T, Sato S, Kasahara S, Sano S, and Oh H. 2017. Intracoronary Cardiac Progenitor Cells in Single Ventricle Physiology: The PERSEUS (Cardiac Progenitor Cell Infusion to Treat Univentricular Heart Disease) Randomized Phase 2 Trial. Circ Res. 120:1162–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishigami S, Ohtsuki S, Tarui S, Ousaka D, Eitoku T, Kondo M, Okuyama M, Kobayashi J, Baba K, Arai S, Kawabata T, Yoshizumi K, Tateishi A, Kuroko Y, Iwasaki T, Sato S, Kasahara S, Sano S, and Oh H. 2015. Intracoronary autologous cardiac progenitor cell transfer in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome: the TICAP prospective phase 1 controlled trial. Circ Res. 116:653–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]