Abstract

Aripiprazole, metformin, and paeoniae–glycyrrhiza decoction (PGD) have been widely used as adjunctive treatments to reduce antipsychotic (AP)-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia. However, the comparative efficacy and safety of these medications have not been previously studied. A network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was conducted to compare the efficacy and safety between aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD as adjunctive medications in reducing AP-induced hyperprolactinemia in schizophrenia. Both international (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases) and Chinese (WanFang, Chinese Biomedical, and Chinese National Knowledge infrastructure) databases were searched from their inception until January 3, 2019. Data were analyzed using the Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulations with the WinBUGS software. A total of 62 RCTs with 5,550 participants were included in the meta-analysis. Of the nine groups of treatments included, adjunctive aripiprazole (<5 mg/day) was associated with the most significant reduction in prolactin levels compared to placebo (posterior MD = −65.52, 95% CI = −104.91, −24.08) and the other eight treatment groups. Moreover, adjunctive PGD (>1:1) was associated with the lowest rate of all-cause discontinuation compared to placebo (posterior odds ratio = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.10, 3.13) and adjunctive aripiprazole (>10 mg/day) was associated with fewer total adverse drug events than placebo (posterior OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.65, 1.77) and other eight treatment groups. In addition, when risperidone, amisulpride, and olanzapine were the primary AP medications, adjunctive paeoniae/glycyrrhiza = 1:1, aripiprazole <5 mg/day, and aripiprazole >10 mg/day were the most effective treatments in reducing the prolactin levels, respectively. Adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD showed beneficial effects in reducing AP-induced hyperprolactinemia in schizophrenia, with aripiprazole (<5 mg/day) being the most effective one.

Keywords: aripiprazole, metformin, paeoniae–glycyrrhiza decoction, hyperprolactinemia, network meta-analysis

Introduction

Hyperprolactinemia (HPRL) is a common adverse effect of antipsychotics (APs), related to the blocking of dopamine receptors (1), which occurs in around 70% patients receiving AP medications (2). The normal plasma level of prolactin is below 25 ng/ml for women and below 20 ng/ml for men, and HPRL refers to sustained prolactin levels above normal (3). HPRL is usually asymptomatic and does not affect the quality of life of patients, but preclinical and clinical evidence indicate that persistent HPRL is associated with an increased risk of sexual dysfunction, weight gain, cardiovascular diseases, and certain mental health problems (e.g., depression) and even cancers (4–6).

Aripiprazole has been shown to effectively reduce the prolactin level due to its partial inhibition of D2 receptors (7). Recently, aripiprazole has been recommended in the guidelines for the treatment of AP-induced HPRL (8). However, aripiprazole is associated with side effects, such as sedation, insomnia, and headache, in some patients (9). Consequently, alternative treatments, such as adjunctive metformin and paeoniae–glycyrrhiza decoction (PGD), have been trialed for AP-induced HPRL.

As a first-line antidiabetic drug, previous studies have found that metformin may reduce weight, insulin resistance, and prolactin levels in patients receiving APs (10). Other studies have also found the benefit of PGD in reducing AP-induced HPRL (11). PGD is a traditional herbal medicine with active ingredients of paeoniae (“shaoyao” in Chinese) and glycyrrhiza (“Gancao” in Chinese), which could modulate D2 receptor expression, inhibit P450 enzymes, and is well-tolerated in schizophrenia patients (12).

The efficacy of aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD in reducing AP-induced HPRL has been separately examined in previous meta-analyses (13–15), but their comparative efficacy and safety have not yet been studied. Network meta-analysis (NMA) is a widely used method which integrates both direct and indirect comparisons based on frequentist model or Bayesian model (16). We thus conducted this NMA of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to compare the efficacy and safety of aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD as adjunctive medications in reducing AP-induced HPRL in schizophrenia.

Methods

This NMA was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Meta-analysis-NMA statement (17) and registered in the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO: CRD42018088004).

Study Criteria

Literature search was performed following the PICOS acronym: participants—adult patients with schizophrenia or schizophrenia spectrum disorders according to study-defined diagnostic criteria; interventions—primary AP plus adjunctive aripiprazole or metformin or PGD; comparators—primary AP plus placebo or AP monotherapy; outcomes—the primary outcome was the mean change of prolactin levels (ng/ml) between baseline and endpoint, while the secondary outcomes included the change in psychotic symptoms as measured by the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (18) or Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (19), adverse drug reactions (e.g., akathisia, somnolence, drooling, fatigue, dizziness, dry mouth, insomnia, and nausea), and all-cause discontinuation; and study type—RCTs with available data on the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and paeoniae–glycyrrhiza decoction for AP-induced hyperprolactinemia. Moreover, head-to-head trials that compared adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD with each other were included, if any. RCTs that used aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD as the primary medications for schizophrenia were excluded.

Study Search and Selection

Three researchers (YX, XL, and DC) independently searched both international (PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Cochrane Library databases) and Chinese (WanFang, Chinese Biomedical, and Chinese National Knowledge infrastructure) databases from inception dates to January 3, 2019 using the combination of medical subject headings and free search terms (Supplementary Materials).

Subsequently, three researchers (YX, XL, and DC) independently screened the title and abstract and then read the full text of the relevant papers. The reference lists of relevant review articles were also checked for additional studies. The first or corresponding authors of related studies were contacted for additional information, if necessary. Any discrepancies in the study selection were resolved by a discussion with a fourth researcher (WZ).

Data Extraction

Two researchers (YX and XL) independently extracted relevant data using a standardized Excel sheet, such as the first author, publication year, country, blinding assessment, use of primary APs and adjunctive medications, diagnosis criteria of schizophrenia, prolactin level, psychotic symptoms, and adverse drug events. Data in figures were extracted using GetData Graph Digitizer 2.2.6 (http://www.getdata-graph-digitizer.com).

Quality Assessment

The Cochrane risk of bias (20) and Jadad scale with three domains (randomization, double blinding, and description withdrawals and dropouts) (21) were used to evaluate the study quality. A Jadad total score of ≥3 was defined as “high quality” (21). The overall quality evidence was examined by the grading of recommendation assessment, development, and evaluation (GRADE) system (22).

Data Analyses

The Bayesian Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation was used to establish the NMA model with the WinBUGS software (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK) (23). Each chain used 20,000 iterations using a burn-in number of 10,000, with a thin interval of 1. We modeled the mean changes of prolactin levels with standard deviations and reported posterior mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The concentration unit of prolactin was unified into nanogram per milliliter using a relevant conversion formula. Standard mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI was calculated as the effect size when pooling the pair-wise results of prolactin level changes. For all-cause discontinuation and adverse drug events, we modeled the odds ratio (OR) with 95%CI.

Use of the random or fixed effects model was determined by the deviance information criteria (DIC), and the model with a smaller DIC was used to perform the NMA (24). In this NMA, the random effects model was used due to a smaller DIC of 1,212.77 (DIC for fixed effects model was 1,309.82). Node-split method was used to calculate the inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence (25). We compared the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD using the surface under the cumulative ranking curve (SUCRA), with the higher area under the curve combined with the higher probability of the best rank indicating better efficacy (26). The final ranks were determined according to the results of Bayesian analyses and SUCRA. Heterogeneity was assessed using I2 (27), with I2 of >50% indicating great heterogeneity. Subgroup (for categorical variables), meta-regression (for continuous variables), and sensitivity analyses were preformed to examine the sources of heterogeneity. Funnel plot and Egger's test were used to assess the pulication bias (28). RCTs with multiple arms were split into several two-arms trials when inputting into Stata (29) (e.g., a RCT with three treatment arms was split into three two-arm studies); therefore, the total number of studies and the overall sample size in Stata (n = 87, sample size = 6,567) were more than in WinBUGS (n = 62, sample size = 5,550). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, with a two-sided test. If adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD were used with the same primary AP, additional NMAs for these studies were performed to directly compare the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD in reducing prolactin levels.

Results

Study Selection

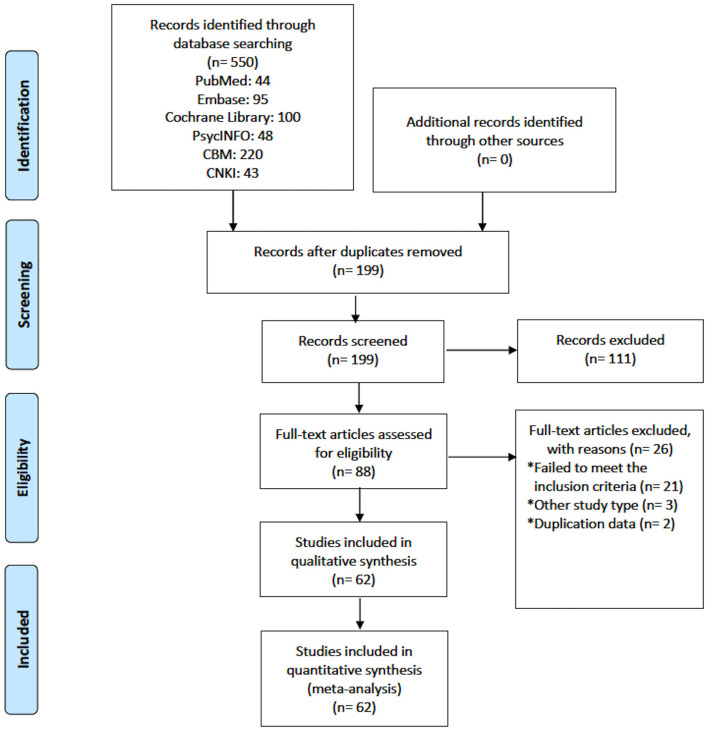

In total, 550 studies were initially identified and, finally, 62 studies with 5,550 participants were included for the analyses. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of the study selection. Fifty-three RCTs used adjunctive aripiprazole, five RCTs used adjunctive PGD, and four RCTs used adjunctive metformin (Table 1). According to the type of primary APs, NMAs were conducted to compare the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole, PGD, and metformin in reducing proclatin levels as follows: any primary APs (62 RCTs), risperidone (22 RCTs), amisulpride (eight RCTs), and olanzapine (seven RCTs). For 25 RCTs with other primary APs (e.g., paliperidone, sulpiride, chlorpromazine, perphenazine, haloperidol, quetiapine, and multiple APs), NMA was not conducted due to the small number of studies and different types of control.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in this meta-analysis.

| No. | First author (Publication Year) | Blind assessment | Sample Size | Age (Years), Mean or range | Male (%) | Trial duration (weeks) | Diagnostic tools | Primary APs | Treatment (dose or paeoniae: glycyrrhizae) | Quality score | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang (2013) | NR | 80 | 32.34 | 41 (51.25) | 12 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | Ari (10–20 mg/d) | 3 | (30) |

| 2 | Li (2016) | NR | 183 | 27.34 | 0 | 8 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | Ari (5 mg/d, 10 mg/d) | 3 | (31) |

| 3 | Li (2016) | NR | 78 | 31.95 | 0 | 12 | DSM-IV | Amisulpride | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (32) |

| 4 | Yang (2016) | NR | 60 | 36.40 | 29 (48.33) | 4 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | Ari (10 mg/d) | 3 | (33) |

| 5 | Lin (2017) | NR | 60 | 35.00 | 60 (100.00) | 8 | CCMD-III | Amisulpride | Ari (10–15 mg/d) | 3 | (34) |

| 6 | Yang (2017) | Double | 41 | 28.48 | 0 | 8 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | PGD (60:30) | 5 | (35) |

| 7 | Sha (2017) | NR | 62 | 42.89 | 62 (100.00) | 8 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | Ari (2.5 mg/d) | 2 | (36) |

| 8 | Jin (2008) | Single | 130 | 25.00 | 0 | 6 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (37) |

| 9 | Liu (2011) | NR | 86 | 36.30 | 46 (53.49) | 4 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d, 10 mg/d) | 2 | (38) |

| 10 | Xia (2011) | NR | 150 | 38.50 | 82 (60.14) | 24 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Metformin (1500 mg/d) | 3 | (39) |

| 11 | Sun (2012) | NR | 34 | 34.95 | 0 | 6 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (40) |

| 12 | Xue (2012) | Single | 68 | 42.40 | 68 (100.00) | 6 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 2 | (41) |

| 13 | Zhu (2012) | Single | 65 | 32.89 | 0 | 8 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (42) |

| 14 | Zhou (2012) | Single | 60 | 34.20 | 0 | 12 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (10 mg/d) | 3 | (43) |

| 15 | Lee (2013) | Double | 35 | 50.74 | 26 (74.28) | 24 | DSM-IV | Risperidone | Ari (10 mg/d) | 3 | (44) |

| 16 | Chen (2013) | Single | 76 | 31.00 | 0 | 6 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (45) |

| 17 | Zhang (2013) | NR | 88 | 36.30 | 42 (47.73) | 4 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (46) |

| 18 | Zhou (2013) | NR | 100 | 18–40 | 0 | 24 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (47) |

| 19 | Zhou (2014) | Double | 170 | 28.02 | 94 (55.29) | 20 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | Metformin (750 mg/d) | 3 | (48) |

| 20 | Shen (2014) | NR | 74 | 30.20 | 74 (100.00) | 9 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (49) |

| 21 | Wang (2014) | NR | 58 | 39.91 | NR | 8 | DSM-IV | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (50) |

| 22 | Chen (2015) | NR | 107 | 55.42 | 0 | 12 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (51) |

| 23 | Chen (2015) | Double | 119 | 33.57 | 58 (48.74) | 8 | DSM-IV | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d, 10 mg/d, 20 mg/d) | 5 | (52) |

| 24 | Xie (2015) | NR | 120 | 18–45 | 0 | 12 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | PGD (30:15, 30:30) | 2 | (53) |

| 25 | Wen (2016) | NR | 200 | 33.90 | 0 | 4 | NR | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d, 10 mg/d, 15 mg/d) | 3 | (54) |

| 26 | Pan (2018) | NR | 90 | 47.60 | 51 (56.67) | 8 | ICD-10 | Amisulpride | Metformin (0.5g/d). Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (55) |

| 27 | Zhang (2018) | Double | 58 | 33.78 | 58 (100) | 8 | DSM-IV | Risperidone | Ari (5 mg/d, 10 mg/d, 20 mg/d) | 4 | (56) |

| 28 | Chen (2012) | NR | 90 | 18–55 | 0 | 8 | CCMD-III | Olanzapine | Ari (10 mg/d) | 2 | (57) |

| 29 | Gu (2016) | NR | 120 | 30.18 | 53 (44.17) | 8 | ICD-10 | Olanzapine | PGD (15:15) | 3 | (58) |

| 30 | Lai (2018) | NR | 136 | 29.20 | 79 (58.09) | 8 | CCMD-III | Olanzapine | Ari (10–30 mg/d) | 2 | (59) |

| 31 | Ping (2018) | NR | 80 | 27.09 | 44 (55.00) | 12 | ICD-10 | Olanzapine | Ari (5 mg/d) | 2 | (60) |

| 32 | Chang (2008) | Double | 62 | 32.43 | 48 (77.42) | 8 | DSM-IV | Clozapine | Ari (5–30 mg/d) | 5 | (61) |

| 33 | Xu (2015) | Open label | 100 | 27.03 | 0 | 8 | ICD-10 | Paliperidone | Ari (10 mg/d) | 1 | (62) |

| 34 | Ren (2011) | Open label | 72 | 18–60 | NR | 8 | ICD-9 | Sulpiride | Ari (10–30 mg/d) | 3 | (63) |

| 35 | Sun (2011) | Open label | 56 | 37.00 | 0 | 12 | ICD-10 | Olanzapine | Ari (10 mg/d) | 3 | (64) |

| 36 | Liang (2014) | Double | 41 | 30.45 | 15 (36.59) | 4 | DSM-IV | Paliperidone | Ari (10 mg/d) | 5 | (65) |

| 37 | Huang (2014) | Open label | 68 | 34.60 | 44 (64.71) | 8 | ICD-10 | Paliperidone | Ari (5 mg/d) | 2 | (66) |

| 38 | Wu (2013) | Open label | 63 | 65.40 | 40 (63.50) | 12 | ICD-10 | Multiple AP | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (67) |

| 39 | Sun (2015) | Open label | 52 | 69.30 | 31 (59.62) | 8 | ICD-10 | NR | Ari (5 mg/d) | 1 | (68) |

| 40 | Song (2009) | Single | 140 | 26.32 | 60 (42.86) | 6 | CCMD-III | Sulpiride | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (69) |

| 41 | Jin (2008) | Open label | 80 | 27.60 | 44 (52.50) | 6 | CCMD-IV | Chlorpromazine | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (37) |

| 42 | Zhang (2017) | Open label | 92 | 35.85 | 48 (52.17) | 12 | NR | Olanzapine | Ari10 mg/d | 3 | (70) |

| 43 | Zhang (2008) | Single | 60 | 25.54 | 25 (41.67) | 6 | CCMD-III | Perphenazine | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (71) |

| 44 | Li (2014) | Open label | 110 | 34.67 | 54 (49.09) | 4 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | Ari (10–30 mg/d) | 2 | (72) |

| 45 | Wang (2016) | Double | 86 | 35.50 | 0 | 8 | CCMD-III | Olanzapine | Ari (5–30 mg/d) | 3 | (73) |

| 46 | Wang (2015) | Open label | 70 | 36.78 | 37 (52.86) | 4 | ICD-10 | Multiple AP | Ari (2.5 mg/d) | 3 | (74) |

| 47 | Sheng (2016) | Open label | 40 | 32.02 | 0 | 8 | ICD-10 | SGAs | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (75) |

| 48 | Wang (2009) | Single | 60 | 33.75 | 0 | 6 | CCMD-III | Haloperidol | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (76) |

| 49 | Tang (2015) | Open label | 150 | 32.87 | NR | 12 | CCMD-III | Risperidone | Ari (5–10 mg/d) | 3 | (77) |

| 50 | Guo (2013) | Single | 86 | 29.84 | 0 | 12 | CCMD-III | Multiple AP | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (78) |

| 51 | Chen (2010) | Single | 60 | NR | 60 (100) | 8 | CCMD-III | Sulpiride | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (79) |

| 52 | Chen (2014) | Double | 116 | 34.04 | 54 (46.55) | 8 | ICD-10 | Risperidone | Ari (10–20 mg/d) | 3 | (80) |

| 53 | Chen (2007) | Open label | 61 | 35.73 | 61 (100.00) | 3 | CCMD-III | Sulpiride | Ari (10 mg/d) | 3 | (81) |

| 54 | Wang (2018) | NR | 60 | 35.55 | 0 | 6 | ICD-10 | Multiple AP | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (82) |

| 55 | Wang (2016) | Open label | 105 | 36.31 | 63 (60.58) | 24 | CCMD-III | Quetiapine + dietary | Metformin (500 mg/d) | 2 | (83) |

| 56 | Wu (2012) | Double | 84 | 26.40 | 0 | 26 | DSM-IV | Multiple AP | Metformin (1000 mg/d) | 5 | (10) |

| 57 | Yue (2016) | Open label | 70 | 32.00 | 33 (47.14) | 4 | DSM-V | NR | PGD (15:10) | 3 | (84) |

| 58 | Man (2016) | Double | 99 | 29.80 | 0 | 16 | ICD-10 | NR | PGD (45g/d) | 5 | (85) |

| 59 | Wang (2017) | Open label | 90 | 36.35 | 43 (47.8) | 8 | ICD-10 | Multiple AP | Ari (5 mg/d,10 mg/d) | 3 | (86) |

| 60 | Xu (2006) | Single | 60 | 24.00 | 0 | 6 | CCMD-III | Multiple AP | Ari (5 mg/d) | 3 | (87) |

| 61 | Shim (2007) | Double | 56 | 39.39 | 22 (40.74) | 8 | DSM-IV | Haloperidol | Ari (15–30 mg/d) | 4 | (88) |

| 62 | Kane (2009) | Double | 323 | 44.20 | 198 (62.30) | 16 | DSM-IV | Multiple AP | Ari (10–15 mg/d) | 4 | (89) |

NR, no report; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition; CCMD-III, Chinese Mental Disorder Classification and Diagnosis, standard 3th edition; ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems; Ari, aripiprazole; PGD, paeoniae-glycyrrhizae decoction; The quality of studies was evaluated by 5-item JADAD scale.

Study Characteristics

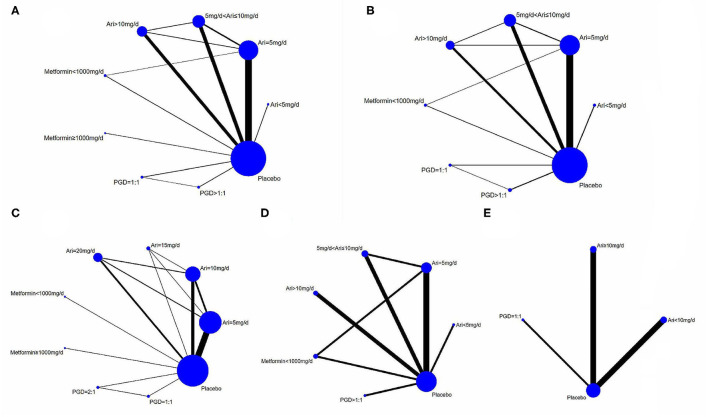

According to the doses of adjunctive aripiprazole, PGD, and metformin, nine groups of treatment were established: aripiprazole (<5 mg/day, n = 2; 5 mg/day, n = 29; 5–10 mg/day, n = 16; >10 mg/day, n = 14), metformin (<1,000 mg/day, n = 3; ≥1,000 mg/day, n = 2), PGD (paeoniae/glycyrrhizae = 1:1, n = 3; paeoniae/glycyrrhizae >1:1, n = 3), and placebo (n = 62) (Figures 2A,B). Following other NMAs (90), the doses are classified according to commonly clinically prescribed dose and the median doses used in the included studies. Eight RCTs had multiple treatment arms that compared different doses of adjunctive aripiprazole, PGD, and metformin (Table 1). The mean age of the participants was 35.2 years, and the median trial duration was 8 weeks. Twenty-three RCTs only included females, while seven RCTs included males. All 62 RCTs reported changes of prolactin levels from baseline to endpoint, while 41 RCTs reported a change in psychotic symptoms as measured by PANSS, 25 reported all-cause discontinuation, and 27 reported adverse drug events.

Figure 2.

Direct comparison of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin and PGD in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia for schizophrenic patients. (A) Direct comparisons of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin and PGD for reducing prolactin levels with all primary antipsychotics. (B) Direct comparisons of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin and PGD in PANSS score changes with all primary antipsychotics. (C–E) Direct comparisons of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin and PGD for reducing prolactin levels when using risperidone, amisulpride and olanzapine respectively as primary antipsychotics, respectively.

Quality Assessment

In the assessment of Cochrane risk of bias, 59 of the 62 studies had a low risk in randomization, and three (48, 62, 68) had a high risk as the patients were randomized to different groups according to the sequence of treatments. The allocation concealment was clearly described in six RCTs but unclear in 45 RCTs and showed a high risk in 11 RCTs. Thirteen RCTs were double-blind, 11 were single-blind, 16 were open-label, and the others did not use blinding methods. Ten RCTs had an unclear risk of bias in incomplete outcome data as they did not report the reasons for the missing data (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Figures 1, 2). The Jadad assessment showed that 41 RCTs (66.1%) were of high quality (Jadad total score ≥3).

The results of GRADE were performed according to direct, indirect, and NMA results separately. In the five node-split direct comparisons, three were considered moderate grade and two were low grade of evidence. Of the 36 indirect comparisons, three (8.3%) were “high” quality, three (8.3%) were “moderate,” four (11.1) were “low,” and others were “very low” (72.2%) grades of evidence. Similarly, of the 36 NMA comparisons, the evidence ranged from “very low” (69.4%), “low” (8.3%), “moderate” (8.3%) to “high” (11.1%) grade. The principal reasons for down-grading included indirectness, large 95%CI, and potential publication bias (Supplementary Table 2).

Overall Primary Antipsychotics

Across the 62 studies, the overall pooled prolactin level decreased from baseline to endpoint significantly when using adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD (SMD = −1.29, 95% CI = −1.35, −1.23, P < 0.01, I2 = 96.5%). In NMA, adjunctive aripiprazole at <5 mg/day showed the most significant decrease in prolactin levels when compared to placebo (posterior MD = −65.52, 95% CI = −104.91, −24.08) and the other eight treatment groups (Table 2) (the best probability, PrBest = 56.3%) (Table 3), followed by aripiprazole at >10 mg/day (posterior MD = −45.85, 95% CI = −60.69, −31.55) and aripiprazole at 5 mg/day (posterior MD = −45.59, 95% CI = −55.89, −35.75).

Table 2.

Network meta-analysis of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD with regard to the mean changes of prolactin levels and PANSS total scores in schizophrenia [mean differences (95% CI)].

| Aripiprazole <5 mg/d (1) | −1.73 (−6.86, 3.57) |

−1.78 (−7.09, 3.74) |

−0.38 (−5.96, 4.97) |

2.70 (−4.09, 9.35) |

−0.87 (−7.95, 5.83) |

−0.46 (−6.72, 5.66) |

−2.54 (−7.37, 2.56) |

−1.73 (−6.86, 3.57) |

| −19.39 (−60.50, 22.54) |

Aripiprazole = 5 mg/d (2) | −0.07 (−2.55, 2.23) |

1.28 (−1.59, 3.98) |

4.36 (−0.66, 9.09) |

0.80 (−4.43, 6.03) |

1.25 (−2.95, 5.43) |

−0.81 (−2.23, 0.54) |

−0.07 (−2.55, 2.23) |

| −23.55 (−65.35, 18.65) |

−3.77 (−19.38, 11.68) |

5 mg/d < Aripiprazole ≤10 mg/d (3) | 1.33 (−1.80, 4.34) |

4.41 (−0.74, 9.53) |

0.89 (−4.60, 6.35) |

1.29 (−3.24, 5.83) |

−0.75 (−2.86, 1.44) |

1.33 (−1.80, 4.34) |

| −19.70 (−61.05, 23.86) |

0.32 (−15.99, 17.62) |

4.02 (−14.91, 23.24) |

Aripiprazole >10 mg/d (4) | 3.19 (−2.03, 8.30) |

−0.47 (−5.95, 5.30) |

−0.04 (−4.67, 4.72) |

−2.07 (−4.54, 0.33) |

3.19 (−2.03, 8.30) |

| −51.97 (−101.27, −2.29) |

−32.67 (−63.87, −0.85) |

−29.04 (−61.64, 4.42) |

−32.54 (−64.68, 0.41) |

Metformin <1,000 mg/d (5) | – | −3.69 (−10.29, 3.35) |

−3.23 (−8.87, 2.91) |

−5.19

(−9.79, −0.35) |

| −50.25 (−110.96, 12.06) |

−30.53 (−80.00, 18.89) |

−26.58 (−75.33, 22.13) |

−30.82 (−80.86, 19.22) |

2.06 (−55.91, 59.97) |

Metformin ≥etformin (6) | – | – | – |

| −42.85 (−92.53, 8.97) |

−22.59 (−55.15, 10.97) |

−18.64 (−53.57, 15.99) |

−22.39 (−56.46, 11.83) |

10.19 (−32.82, 52.12) |

7.78 (−47.80, 66.89) |

PGD = 1:1 (7) | 0.37 (−5.37, 6.01) |

−1.62 (−6.57, 3.47) |

| −36.05 (−86.61, 15.65) |

−15.45 (−48.96, 15.46) |

−11.87 (−46.51, 21.31) |

−15.86 (−51.30, 17.29) |

16.83 (−25.96, 57.14) |

14.76 (−42.82, 69.39) |

6.62 (−32.21, 45.70) |

PGD > 1:1 (8) | −2.03 (−5.95, 1.79) |

|

−65.52

(−104.91, −24.08) |

−45.59 (−55.89, −35.75) |

−41.79 (−55.44, −28.21) |

−45.85 (−60.69, −31.55) |

−13.03 (−43.58, 16.64) |

−15.06 (−63.26, 33.40) |

−22.70 (−54.86, 7.84) |

−30.00 (−59.90, 1.13) |

Placebo (9) |

□ Prolactin level changes. ■ PANSS total score changes.

The results of the random effects NMA model are displayed. Bold values indicate the most effective treatments. Dark gray indicated the nine interventions.

Table 3.

Rankings of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin and PGD in reducing prolactin levels in schizophrenia.

| Outcomes | APs (number of studies) | Treatment | SUCRA (%) | PrBest (%) | Mean Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prolactin level changes | All (n = 62) | Ari < 5 mg/d | 78.8 | 56.3 | 2.7 |

| Ari > 10 mg/d | 90.3 | 36.5 | 1.8 | ||

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 73.6 | 1.7 | 3.1 | ||

| PGD > 1:1 | 58.3 | 1.6 | 4.3 | ||

| PGD = 1:1 | 58.0 | 4.0 | 4.4 | ||

| 5 mg/d < Ari ≤ 10 mg/d | 48.1 | 0.0 | 5.2 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 27.0 | 0.0 | 6.8 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 8.7 | 0.0 | 8.3 | ||

| Placebo | 7.2 | 0.0 | 8.4 | ||

| Risperidone (n = 22) | PGD = 1:1 | 81.0 | 31.2 | 2.5 | |

| Ari = 20 mg/d | 80.4 | 18.8 | 2.6 | ||

| PGD = 2:1 | 78.0 | 24.4 | 2.8 | ||

| Ari = 15 mg/d | 59.2 | 25.4 | 4.3 | ||

| Ari = 10 mg/d | 56.7 | 0.2 | 4.5 | ||

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 48.6 | 0.0 | 5.1 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 15.4 | 0.0 | 7.8 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 15.4 | 0.0 | 7.8 | ||

| Placebo | 15.4 | 0.0 | 7.8 | ||

| Amisulpride (n = 8) | Ari < 5 mg/d | 89.1 | 78.7 | 1.7 | |

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 86.2 | 20.5 | 1.8 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 58.1 | 0.1 | 3.5 | ||

| PGD > 1:1 | 48.0 | 0.5 | 4.1 | ||

| 5 mg/d < Ari ≤ 10 mg/d | 44.9 | 0.2 | 4.3 | ||

| Ari > 10 mg/d | 20.5 | 0.0 | 5.8 | ||

| Placebo | 3.2 | 0.0 | 6.8 | ||

| Olanzapine (n = 7) | Arinzapine | 98.3 | 94.9 | 1.1 | |

| PGD = 1:1 | 61.2 | 5.1 | 2.2 | ||

| Ari <10 mg/d | 39.2 | 0.0 | 2.8 | ||

| Placebo | 1.2 | 0.0 | 4.0 | ||

| PANSS total score changes | All (n = 41) | Metformin < 1,000 mg/d | 71.3 | 42.7 | 3.0 |

| PGD = 1:1 | 53.3 | 24.3 | 4.3 | ||

| PGD > 1:1 | 52.9 | 9.9 | 4.3 | ||

| Ari > 10 mg/d | 51.6 | 6.2 | 4.4 | ||

| Ari <5 mg/d | 48.6 | 14.8 | 4.6 | ||

| 5 mg/d < Ari ≤ 10 mg/d | 46.1 | 1.6 | 4.8 | ||

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 41.4 | 0.4 | 5.1 | ||

| Placebo | 34.9 | 0.0 | 5.6 | ||

| Risperidone (n = 13) | Ari > 10 mg/d | 61.7 | 25.7 | 2.9 | |

| 5 < Ari ≤ 10 mg/d | 65.2 | 25.6 | 2.7 | ||

| PGD > 1:1 | 46.3 | 22.4 | 3.7 | ||

| PGD = 1:1 | 44.7 | 21.3 | 3.8 | ||

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 44.1 | 3.4 | 3.8 | ||

| Placebo | 37.9 | 1.7 | 4.1 | ||

| Amisulpride (n = 7) | Ari < 5 mg/d | 58.1 | 27.1 | 3.5 | |

| Ari = 5 mg/d | 64.3 | 16.1 | 3.1 | ||

| PGD > 1:1 | 53.6 | 9.3 | 3.8 | ||

| Metformin <1,000 mg/d | 49.2 | 17.8 | 4.0 | ||

| 5 mg/d < Ari ≤ 10 mg/d | 47.9 | 15.8 | 4.1 | ||

| Ari > 10 mg/d | 43.6 | 13.7 | 4.4 | ||

| Placebo | 33.5 | 0.2 | 5.0 |

Values in bold are those ranked the first. Ari, aripiprazole; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; PGD, paeoniae-glycyrrhizae decoction; PrBest, the best probability; SUCRA, Surface under the cumulative ranking curve; Aps, antipsychotics.

Similarly, a reduction of PANSS total scores was significantly associated with the use of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD (SMD = −0.12, 95% CI = −1.80, −0.06; P < 0.01, I2 = 60.7%). In NMA, metformin at <1,000 mg/day was most efficacious in reducing the total PANSS score compared to placebo (posterior MD = −5.19, 95% CI = −9.79, −0.35; PrBest = 42.7%) and the other seven treatment groups (Tables 2, 3), followed by PGD = 1:1 (posterior MD = −1.62, 95% CI = −6.57, 3.47). The analyses of BPRS total score were not performed due to an insufficient number of studies.

The NMA of all-cause discontinuation and adverse drug events was performed to evaluate the tolerability and safety of the three adjunctive medications separately. Of the nine treatment groups, PGD >1:1 had the lowest rate of all-cause discontinuation compared to placebo (posterior OR = 0.45, 95% CI = 0.10, 3.13) and the other eight treatment groups (Supplementary Table 3). Moreover, aripiprazole at >10 mg/day led to fewer total adverse drug events than placebo (posterior OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.65, 1.77) and other groups (Supplementary Table 3). For akathisia reported in 10 RCTs, aripiprazole at >10 mg/day showed a lower number of akathisia than placebo (posterior OR = 0.77, 95% CI = 0.25, 2.39), aripiprazole = 5 mg/day (posterior OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.18, 4.47), PGD = 1:1 (posterior OR = 0.39, 95% CI = 0.01, 4.91), and PGD >1:1 (posterior OR = 0.38, 95% CI = 0.05, 5.24). For somnolence, which was reported in 10 RCTs, aripiprazole at <5 mg/day had fewer somnolence than placebo (posterior OR <0.01, 95% CI = 0.00, 2.02) and the other five treatment groups. Aripiprazole at <5 mg/day had likewise the lower number of insomnia (19 RCTs) and nausea (six RCTs) than placebo (posterior OR = 0.81, 95% CI = 0.01, 50.15 for insomnia; posterior OR <0.01, 95% CI = 0.00, 0.65 for nausea) and the other groups. In 14 RCTs with data on headaches, PGD = 1:1 had a lower frequency of headache than placebo (posterior OR = 0.44, 95% CI = 0.00, 41.04) and the other groups.

Risperidone as the Primary Antipsychotic Medication

Twenty-two RCTs used risperidone as primary AP, and the network plot is shown in Figure 2C. In total, nine treatment groups were examined. The pooled pair-wise SMD of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD regarding prolactin level change from baseline to endpoint was −1.28, 95% CI (−1.36, −1.20), P < 0.01, I2 = 94.8%. NMA showed that PGD = 1:1 had the most significant effect on prolactin reduction compared to placebo (posterior MD = −47.58, 95% CI = −114.5, −45.4) and other treatment groups (Supplementary Table 4).

When compared with placebo and other medications, aripiprazole at >10 mg/day had the most significant effect in reducing the PANSS total score from baseline to endpoint across 13 RCTs with the posterior MD of −4.09, 95%CI: −6.55, −1.12 (PrBest = 25.7%). The NMA of all-cause discontinuation and ADRs were not performed due to insufficient studies.

Amisulpride as the Primary Antipsychotic Medication

Eight studies reported a change in prolactin levels with amisulpride as the primary AP. The direct comparisons are shown in Figure 2D. The pooled SMD of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD for the change in prolactin levels was −1.24, 95% CI (−1.42, −1.06), P < 0.01, I2 = 98%. NMA revealed that aripiprazole at <5 mg/day had the most significant effect in reducing the prolactin levels compared to placebo (posterior MD = −74.30, 95% CI = −163.30, −73.88) and the other treatment groups (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 5), followed by aripiprazole at 5 mg/day (posterior MD = −74.30, 95% CI = −163.30, −73.88) and metformin <1,000 mg/day (posterior MD = −25.60, 95% CI = −37.47, −13.75) (Supplementary Table 5). In addition, aripiprazole at <5 mg/day showed the most significant decrease in PANSS total score compared to placebo (posterior MD = −6.76, 95% CI = −83.70, 74.23), followed by aripiprazole at 5 mg/day (posterior MD = −1.65, 95% CI = −42.78, 42.46).

Olanzapine as Primary Antipsychotic Medication

Seven RCTs which used adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD reported prolactin level reduction with olanzapine as the primary AP. The pooled pair-wise SMD was −2.51, 95% CI (−2.73, −2.28), P < 0.01, I2 = 96.5%. Aripiprazole at ≥10 mg/day showed a significant reduction of prolactin levels compared to placebo (posterior MD = −33.77, 95% CI = −51.34, −24.86), followed by aripiprazole at <10 mg/day (posterior MD = −27.64, 95% CI = −45.11, −9.18) and PGD = 1:1 (posterior MD = −17.56, 95% CI = −41.96, −18.23) (Supplementary Table 6). The NMA of PANSS total changes, all-cause discontinuation, and ADRs was not performed due to insufficient studies.

Inconsistency, Publication Bias, and Additional Analyses

The node-split method was performed to explore the inconsistency of prolactin changes between direct and indirect comparisons within loops. Overall, no significant inconsistencies in aripiprazole at 5 mg/day vs. 5 mg/day < aripiprazole ≤ 10 mg/day (P = 0.25), aripiprazole = 5 mg/day vs. aripiprazole >10 mg/day (P = 0.19), aripiprazole = 5 mg/day vs. metformin <1,000 mg/day (P = 0.42), 5 mg/day < aripiprazole ≤ 10 mg/day vs. aripiprazole >10 mg/day (P = 0.83), PGD = 1:1 vs. PGD >1:1 (P = 0.83) were found in primary APs. The details are shown in the GRADE evaluation (Supplementary Table 2). Both Funnel plot and Egger's test found obvious publication bias (t = −9.91, P < 0.01) in the 62 RCTs. Moreover, “trim and fill” method was used, and the “correct” estimations of pooled SMD was −2.18, 95% CI (−2.50, −1.86).

Supplementary Table 7 shows the subgroup analyses of the efficacy of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD in reducing prolactin levels. RCTs which were of single blind design (SMD = −2.45, 95%CI: −2.63, −2.26), involving both male and female genders (SMD = −1.45, 95%CI: −1.54, −1.37), using the CCMD-III (SMD=-1.82, 95%CI: −1.92, −1.71), and having smaller sample size (SMD=-1.50, 95%CI: −1.60, −1.41) exhibited a more obvious reduction in prolactin levels. Meta-regression analyses revealed that mean age (P = 0.27), Jadad quality score (P = 0.11), trial duration (P = 0.46), and total sample size (P = 0.99) were not significantly associated with the heterogeneity of the pooled results. The blinding method was significantly associated with the great heterogeneity (P = 0.03) and explained 4.8% of the heterogeneity.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the first NMA to compare the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD in reducing AP-induced HPRL for schizophrenia. The results showed that aripiprazole (<5 mg/day) was associated with the most significant decrease in AP-induced prolactin levels when compared to placebo and other treatments. The NMA also found that adjunctive PGD (1:1) had the most significant effect in reducing risperidone-induced HPRL. Adjunctive aripiprazole (<5 mg/day) had the most significant effect in reducing amisulpride-induced HPRL, and aripiprazole (>10 mg/day) had the most significant effect in reducing olanzapine-related HPRL. Moreover, PGD (>1:1) was associated with the lowest rate of all-cause discontinuation, and aripiprazole (>10 mg/day) had fewer total ADRs.

The advantage of aripiprazole in reducing HPRL is consistent with previous reviews (13, 91). In addition, the advantage of aripiprazole at the dose of <5 mg/day compared to higher doses suggests that higher doses are unnecessary to reduce the AP-induced prolactin level for schizophrenia. This finding is similar to previous findings that aripiprazole at a low dose (3 mg/day) could reduce HPRL, but with increasing dose, the effect reaches a plateau at doses beyond 6 mg/day (92). This is probably because most D2 receptors are already occupied in the striatum at low-dose aripiprazole (93). Some studies did not find a significant association between prolactin levels and the dose of aripiprazole (94), while others (52) found that the effects of aripiprazole on prolactin reduction were significantly greater at higher doses (10 and 20 mg/day) than at 5 mg/day. In this meta-analysis, aripiprazole at both >10 and 5 mg/day had less effects than at <5 mg/day in reducing the prolactin levels. The dose–response effects of aripiprazole on AP-induced HPRL would require further research.

This NMA also found that the prolactin reduction effects of adjunctive aripiprazole, PGD, and metformin are variable across different primary APs—for example, adjunctive PGD = 1:1 was most effective in reducing risperidone-related HPRL, while adjunctive aripiprazole at doses of <5 and ≥10 mg/day are most effective in reducing amisulpride- and olanzapine-related HPRL, respectively. It is likely that the impact of various antipsychotic medications on prolactin levels is different (90). Due to the relatively slow dissociation rate with D2 receptors and weak blood–brain barrier penetrating ability, risperidone is more likely to elevate prolactin compared to other APs (95). The powerful effect of PGD on risperidone-induced HPRL may be associated with its modulation of D2 receptor and transporters and normalization of sex hormone dysfunction through the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis (96). Of the three adjunctive medications in this NMA, PGD >1:1 was associated with the least all-cause discontinuation rate, which supports the high tolerability in schizophrenia patients. However, the quality standardization of PGD preparation is still lacking, and efficacy studies of PGD on HPRL need to be replicated in countries other than China.

The effect of metformin on the reproductive axis was first found in women with polycystic ovary syndrome (97). Some studies later found that metformin could act on pituitary function and reduce the levels of luteinizing hormone, gonadotropin, and prolactin (98). However, this NMA did not find any significant effect of adjunctive metformin in suppressing the prolactin level, which is probably because metformin may only be effective in reducing AP-induced HPRL at high doses (2.55–3 g/day) and after prolonged treatment courses (99). In this NMA, the doses of adjunctive metformin ranged from 0.5 to 1.5 g/day in five studies, which could explain the non-significant effects. Furthermore, the baseline prolactin level and the different stages of reproductive life could also influence the effectiveness of treatments on HPRL (100). Therefore, long-term metformin treatment at a higher dose may be more clinically useful to treat AP-induced HPRL in those with obesity or diabetes. It should be noted that the long-term use of metformin could decrease the serum levels of folic acid and vitamin B12 and increase serum homocysteine (101). Therefore, the concentration of folic acid, B12, and homocysteine needs to be regularly monitored if long-term metformin treatment for AP-related HPRL and/or metabolic syndrome is given.

Subgroup analyses found that male patients had a greater reduction in prolactin levels when compared to female patients after receiving adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, or PGD, which is similar to previous findings that aripiprazole had a significantly lower risk of HPRL in men but not in women (102). The sex difference in prolactin reduction may be associated with endogenous cholinergic neuronal activity, concentration of estrogen, and genetic variations of D2 receptors (103). Due to the lower response to pharmacotherapy in females, the gender differences in terms of doses, type, and treatment duration of adjunctive medication for AP-related HPRL should be considered.

The strengths of this study include the use of NMA to compare the efficacy and safety of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD for AP-induced HPRL. In addition, the effects of adjunctive aripiprazole, metformin, and PGD are compared with respect to different AP medications (e.g., risperidone, amisulpride, and olanzapine). However, several limitations should be noted. First, the positive and negative symptoms as measured by the PANSS and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and data on sexual dysfunction were not analyzed due to insufficient original data. Most studies did not present data by gender; therefore, the influence of gender on outcomes could not be examined. Second, we manually searched the gray literature, but a significant publication bias remained in the analyses, which is probably associated with unpublished non-significant findings. Third, despite conducting subgroup and meta-regression analyses, there were obvious heterogeneity between studies due to inconsistent samples, methodology, and study quality. Lastly, dose–response relationships were not examined due to insufficient data.

Conclusions

Adjunctive aripiprazole, PGD, and metformin could be effective in reducing AP-induced HPRL in schizophrenia. However, in clinical practice, the selection of an appropriate adjunctive medication for AP-induced HPRL should be individualized according to the needs of the patient.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

LZ, WZ, and Y-TX participated in the study design. HQ, Y-YX, X-HL, and D-BC participated in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. LZ, HQ, and Y-TX drafted the manuscript. CN and GU contributed to the critical revision of the manuscript. All the authors approved the final version for publication.

Funding

This work was supported by The National Key Research and Development Program of China grant number (no. 2016YFC0900600/2016YFC0900603 and no. 2016YFC1307200), the University of Macau (no. MYRG2015-00230-FHS and no. MYRG2016-00005-FHS), the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals Incubating Program (no. PX2016028), and the Beijing Municipal Administration of Hospitals' Ascent Plan (no. DFL20151801).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.728204/full#supplementary-material

References

- 1.Petty RG. Prolactin and antipsychotic medications: mechanism of action. Schizophr Res. (1999) 35:S67–73. 10.1016/S0920-9964(98)00158-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Inder WJ, Castle D. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. (2011) 45:830–7. 10.3109/00048674.2011.589044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, Kleinberg DL, Montori VM, Schlechte JA, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2011) 96:273–88. 10.1210/jc.2010-1692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Froes Brandao D, Strasser-Weippl K, Goss PE. Prolactin and breast cancer: the need to avoid undertreatment of serious psychiatric illnesses in breast cancer patients: a review. Cancer. (2016) 122:184–8. 10.1002/cncr.29714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston AN, Bu W, Hein S, Garcia S, Camacho L, Xue L, et al. Hyperprolactinemia-inducing antipsychotics increase breast cancer risk by activating JAK-STAT5 in precancerous lesions. Breast Cancer Res. (2018) 20:42. 10.1186/s13058-018-0969-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Milano W, D'Acunto CW, De Rosa M, Festa M, Milano L, Petrella C, et al. Recent clinical aspects of hyperprolactinemia induced by antipsychotics. Rev Recent Clin Trials. (2011) 6:52–63. 10.2174/157488711793980138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shapiro DA, Renock S, Arrington E, Chiodo LA, Liu LX, Sibley DR, et al. Aripiprazole, a novel atypical antipsychotic drug with a unique and robust pharmacology. Neuropsychopharmacology. (2003) 28:1400–11. 10.1038/sj.npp.1300203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halperin Rabinovich I, Camara Gomez R, Garcia Mouriz M, Ollero Garcia-Agullo D. [Clinical guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of prolactinoma and hyperprolactinemia]. Endocrinol Nutr. (2013) 60:308–19. 10.1016/j.endonu.2012.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marder SR, McQuade RD, Stock E, Kaplita S, Marcus R, Safferman AZ, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia: safety and tolerability in short-term, placebo-controlled trials. Schizophr Res. (2003) 61:123–36. 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00050-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu RR, Jin H, Gao K, Twamley EW, Ou JJ, Shao P, et al. Metformin for treatment of antipsychotic-induced amenorrhea and weight gain in women with first-episode schizophrenia: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. (2012) 169:813–21. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11091432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada K, Kanba S, Yagi G, Asai M. Herbal medicine (Shakuyaku-kanzo-to) in the treatment of risperidone-induced amenorrhea. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (1999) 19:380–1. 10.1097/00004714-199908000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasani-Ranjbar S, Vahidi H, Taslimi S, Karimi N, Larijani B, Abdollahi M. A systematic review on the efficacy of herbal medicines in the management of human drug-induced hyperprolactinemia; potential sources for the development of novel drugs. Int J Pharmacol. (2010) 6:691–5. 10.3923/ijp.2010.691.695 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Tang Y, Wang C. Adjunctive aripiprazole versus placebo for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e70179. 10.1371/journal.pone.0070179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zheng W, Cai DB, Li HY, Wu YJ, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, et al. Adjunctive Peony-Glycyrrhiza decoction for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Gen Psychiatr. (2018) 31:e100003. 10.1136/gpsych-2018-100003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng W, Yang XH, Cai DB, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, Wang N, et al. Adjunctive metformin for antipsychotic-related hyperprolactinemia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Psychopharmacol. (2017) 31:625–31. 10.1177/0269881117699630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. (2005) 331:897–900. 10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Reprint–preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Phys Ther. (2009) 89:873–80. 10.1093/ptj/89.9.873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. (1987) 13:261–76. 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overall JE GD. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychol Rep. (1962) 10:799–812. 10.2466/pr0.1962.10.3.799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S. editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. (1996) 17:1–12. 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, Eccles M, Falck-Ytter Y, Flottorp S, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. (2004) 328:1490. 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ades AE, Sculpher M, Sutton A, Abrams K, Cooper N, Welton N, et al. Bayesian methods for evidence synthesis in cost-effectiveness analysis. Pharmacoeconomics. (2006) 24:1–19. 10.2165/00019053-200624010-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dias S, Sutton AJ, Ades AE, Welton NJ. Evidence synthesis for decision making 2: a generalized linear modeling framework for pairwise and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Decis Mak. (2013) 33:607–17. 10.1177/0272989X12458724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dias S, Welton NJ, Caldwell DM, Ades AE. Checking consistency in mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. Stat Med. (2010) 29:932–44. 10.1002/sim.3767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salanti G, Ades AE, Ioannidis JP. Graphical methods and numerical summaries for presenting results from multiple-treatment meta-analysis: an overview and tutorial. J Clin Epidemiol. (2011) 64:163–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.03.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. (2003) 327:557–60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. (1997) 315:629–34. 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaimani A, Higgins JP, Mavridis D, Spyridonos P, Salanti G. Graphical tools for network meta-analysis in STATA. PLoS ONE. (2013) 8:e76654. 10.1371/journal.pone.0076654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang XL, Xie J. Aripiprazole combined with amisulpride in the treatment of schizophrenia with negative symptoms (in Chinese). J Qiqihar Med Univ. (2013) 34:1734–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-1256.2013.12.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li M, Zhang SF, Shao YC, Fu HP, Qiu SW. Effect of different dosage aripiprazole on proiactin in female schizophrenia with amisulpride treated (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2016) 24:175–8. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2016.02.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li JG. Efficacy of amisulpride combined with aripiprazole in female patients with schizophrenia (in Chinese). Med Equip. (2016) 29:120–1. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-2376.2016.20.094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang Y, Xia Y, Zhu CJ, Chen YB. Effect of aripiprazole on hyperprolactinemia induced by amisulpride (in Chinese). Chin J Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2016) 21:693–6. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lin YC. Aripiprazole combined w ith amisulpride in the treatment of male schizophrenia patients with hyperprolaetinemia in 30 cases (in Chinese). China Health Stand Manage. (2017) 8:55–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-9316.2017.17.029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang P, Li L, Yang D, Wang C, Peng H, Huang H, et al. Effect of peony-glycyrrhiza decoction on amisulpride-induced hyperprolactinemia in women with schizophrenia: a preliminary study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. (2017) 2017:7901670. 10.1155/2017/7901670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sha JM, Zhang W, Ding JJ, Chen GD. Effect of low-dose aripiprazole combined with amisulpride on sexual function and prolactin in male patients with schizophrenia (in Chinese). Chin Rural Health Serv Administr. (2017) 37:356–8. 10.13479/j.cnki.jip.2018.04.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin JF, Chao YQ, Xu LP, Song ZX, Shao YQ. Clinical study of combined low-dose aripiprazole to improve hyperprolactinemia induced by chlorpromazine (in Chinese). J Psychiatry. (2008) 21:455–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-7201.2008.06.022 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu L, Deng SG, Dong XH, Jiang DZ, Cui FW, Pan QH. A placebo-controlled trial of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole for risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2011) 19:1288–90. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2011.11.046 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xia JX, Wang YB, Gan JG, Cao SL, Duan D, Qian PH, et al. Efficacy of metformin combined behavior intervention in the treatment of metabolic disorders caused by risperidone (in Chinese). Chinese J Clin Pharmacol. (2011) 27:417–9. 10.13699/j.cnki.1001-6821.2011.06.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun XG. Clinical study of low-dose aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia in women with risperidone (in Chinese). Medical J Chin People's Health. (2012) 24:1343–4. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2012.11.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xue L, Zhou LJ, Tan WZ, Zou YF, Hu JW, Huang ZM. Aripiprazole in the treatment of 68 cases of male hyperprolactinemia caused by risperidone (in Chinese). Jilin Yi Xue. (2012) 33:107–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1004-0412.2012.01.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhu JX, Yin JB. A clinical controlled study of aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia in women with risperidone (in Chinese). Chin Commun Doct. (2012) 14:124–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2012.01.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhou HS, Li B, Liu J, Wang HL. The efficacy and safety of aripiprzole in the treatment of female hyperprolact inemia caused by risperidone (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2012) 20:1129–30. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2012.08.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee BJ, Lee SJ, Kim MK, Lee JG, Park SW, Kim GM, et al. Effect of aripiprazole on cognitive function and hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia treated with risperidone. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. (2013) 11:60–6. 10.9758/cpn.2013.11.2.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen SH. Clinical observation of aripiprazole in the treatment of drug-induced amenorrhea caused by risperidone (in Chinese). Med J Chin People's Health. (2013) 25:56–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1672-0369.2013.03.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang HF, Chai YL. Controlled clinical study of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole for risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). Chin J Modern Drug Appl. (2013) 7:18–19. 10.14164/j.cnki.cn11-5581/r.2013.19.195 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhou P, Liu LQ, Hao JF, Zhang HX, Yu J, Li YY, et al. The Study of Aripiprazole on preventing the hyperprolactinemia induced by antipsychotics on female schizophrenic patients (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2013) 23:263–64. 10.13479/j.cnki.jip.2014.02.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou JQ, Dong ZW, Zhou X. Metformin treatment of risperidone starting schizophrenia patients with the influence of bai metabolic control study (in Chinese). Chin J Drug Abuse Prev Treat. (2014) 20144–7+154. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-902X.2014.03.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen ZT. Effect of aripiprazol on increased prolactin caused by risperidone (in Chinese). Pract Pharm Clin Remed. (2014) 17:871–4. 10.14053/j.cnki.ppcr.2014.07.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang W, Wang J, Luo X, Ye ZC, Lin YY. Controlled clinical research on treatment of schizophrenia by risperidone combined with low-dose aripiprazole (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2014) 22:964–6. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2014.07.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Q, Qian ZP, Lu FR, Fei P. Effect of aripiprazole on the hyperprolactinmia induced by risperidone in quinquagenarian female schizophrenia patients (in Chinese). Sichuan Mental Health. (2015) 28:420–3. 10.11886/j.issn.1007-3256.2015.05.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen JX, Su YA, Bian QT, Wei LH, Zhang RZ, Liu YH, et al. Adjunctive aripiprazole in the treatment of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-response study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2015) 58:130–40. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie SS, Ding L, Chen YQ. Effects of peony licorice bolus of risperidone with different proportions on female schizophrenia patients suffered hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). Med Res Educ. (2015) 32:35–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-490X.2015.05.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wen N, Tang W, Pan JS, Zhang JL. Aripiprazole ameliorated the increase of prolactin in female patients with schizophrenia caused by risperidone (in Chinese). Zhejiang Clin Med Jo. (2016) 18:1606–8. Available online at: https://d-wanfangdata-com-cns.vpn.ccmu.edu.cn/periodical/ChlQZXJpb2RpY2FsQ0hJTmV3UzIwMjEwODE4Eg96amxjeXgyMDE2MDkwMTQaCHI2OG9rYXds [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan XO, Ju ML, Wu J, Qian ZS. Therapeutic effects of aripiprazole and metformin on hyperprolactinemia caused by amisulpride medication (in Chinese). Hebei Med J. (2018) 40:2984–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-7386.2018.19.026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang LG, Li YL, Liu Y, Chen JX, Liu YH. Dose-effect relationship of aripiprazole on hyperprolactinemia induced by risperidone in m ale patients (in Chinese). Chinese J New Drugs. (2018) 27:334–8. 10.3969/j.issn.1003-3734.2018.03.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen JH, Wu YF, Liao XZ. Efficacy analysis of olanzapine combined with aripiprazole in the treatment of first-episode schizophrenia in women (in Chinese). Guide Chin. Med. (2012) 10:145–6. 10.15912/j.cnki.gocm.2012.22.274 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gu P, Jin X, Li X, Wu YQ. Treatment of olanzapine-induced hyperprolactinemia by shaoyao gancao decoction (in Chinese). Chinese J Integr Trad Western Med. (2016) 36:1456–9. 10.7661/CJIM.2016.12.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lai ZC. Clinical effect of aripiprazole and olanzapine in the treatment of schizophrenia (in Chinese). Chin Foreign Med Res. (2018) 16:36–8. 10.14033/j.cnki.cfmr.2018.25.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ping JJ, Deng SS, Wan J, Xue SX. Effect of combination of aripiprazole with olanzapine on sex hormone of patients with schizophrenia (in Chinese). Med Innov China. (2018) 15:135–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2018.12.039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang JS, Ahn YM, Park HJ, Lee KY, Kim SH, Kang UG, et al. Aripiprazole augmentation in clozapine-treated patients with refractory schizophrenia: an 8-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. (2008) 69:720–31. 10.4088/jcp.v69n0505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu D, Zhu JJ, Wan HY, Li M. Effect of low-dose aripiprazole on prolactin elevation in patients with schizophrenia induced by amisulpride (in Chinese). Chin J Pract Nerv Dis. (2015) 18:28–9. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ren LZ, Hu M. Preventive effect of aripiprazole on sulpiride-induced hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). Med Inform. (2011) 24:2455. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2011.06.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sun W, Zhang JL, Kang MX. Aripiprazole improves the weight gain and prolactin levels in women with schizophrenia induced by olanzapine (in Chinese). Sichuan Mental Health. (2011) 24:98–100. 10.3969/j.issn.1007-3256.2011.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liang J, Yan J, Zhang XY. Aripirazole reduces paliperidone-induced increase of prolactin in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double blind and placebo-controlled study (in Chinese). Chin J New Drugs. (2014) 23:1300–3+1310. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Huang SN, Yang SZ, Liu XX. Clinical study of paliperidone combined with aripiprazole in the treatment of schizophrenia (in Chinese). Med Inform. (2014) 23:471–2. 10.3969/j.issn.1006-1959.2014.18.573 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wu HL, Lin DD, Li Y, Xu YJ. Influence of aripiprazole on hyperprolactinemia caused by antipsychotics in elderly patients with schizophrenia (in Chinese). J Clin Psychiatry. (2013) 23:263–4. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun W, Ma SF, Gao TF. Efect of aripiprazole on hyperprolactinemia in patients with senile schiz0phr nia induced by antipsychotic drugs (in Chinese). China Foreign Med Treat. (2015) 34:109–10. 10.16662/j.cnki.1674-0742.2015.17.080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Song ZX, Chen Q, Xu LP, Cai ZK, Ji JY, Wang WH, et al. Aripiprazole in the treatment of 70 cases of hyperprolactinemia caused by sulpiride (in Chinese). Herald Med. (2009) 28:479–81. 10.3870/yydb.2009.04.030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang WH, Chen XY, Wang XJ, Zhou HX. Clinical effect of aripiprazole on olanzapine in the treatment of post-schizophrenia patients with increased body weight (in Chinese). Chin J Biochem Pharmaceut. (2017) 37:201–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-1678.2017.03.061 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang B, Wang L, Xu LP, Shi JA, Sun J. Clinical study of aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia caused by perphenazine (in Chinese). J Neurosis Mental Health. (2008) 8:375–6. 10.3969/j.issn.1009-6574.2008.05.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Li YJ, Gao H. Effect of aripiprazole combined with risperidone for lowering serum prolactin in scltlzophrenic patients (in Chinese). China Pharmaceut. (2014) 23:88–90. Available online at: https://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/detail.aspx?dbcode=CJFD&dbname=CJFD2014&filename=YYGZ201413050&v=lK7z3XfJhtwN3J0CgygjqMpXCemBexaommDpuVTVpts9EQaCCv3j4PJAV6fCsa7N [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang HL. Clinical study of aripiprazole and olanzapine in the treatment of female schizophrenia (in Chinese). Modern Diagn Treat. (2016) 27:234–5. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wang YF, Lv BJ, He EB. The effect of combined with aripiprazole to improve hyperprolactinemia caused by antipsychotic drugs (in Chinese). Chin J Prim Med Pharm. (2015) 1187–9. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1008-6706.2015.08.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sheng JH, Lu GH, Qiao Y, Qiao Y. Effect of small dose aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia induced by second generation antipsychotics (in Chinese). J Psychiatry. (2016) 29:245–8. 10.3969/j.issn.2095-9346.2016.04.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang L, Zhang B, Xu LP, Shi JA, Shao YQ. A ciinical study on aripiprzole in the treatment of female hyperprolactinemia by haloperidol (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2009) 17:194–5. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2009.02.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Tang P, Feng J, Xia N. Observation on effect of aripiprazole in treatment of hyperprolactinemia caused by risperidone in schizophrenic patients in 75 cases (in Chinese). China Pharmaceut. (2015) 24:19–20. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Guo JH, Cao CA, Liao CP, Xu YM, Liu YY. A control study on aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprol actinaemaia by antipsychotics (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. (2013) 21:487–9. 10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2013.04.063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chen LJ, Zhuo ZM, Zhuang H. A study of aripiprazole in sulpiride induced male hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). J Clin Psychiatry. (2010) 20:304–5. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen JX, Zhang RZ, Li W. Adjunctive treatment of risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia with aripiprazole: a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study (in Chinese). Chin J New Drugs. (2014) 23:811–4. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chen HZ, Yu BR, Yang SG, Shen ZX, Mi Q, Jiang YH. Effect of aripiprazoleonthe hyperprolactinernia caused by sulpiride in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia—a clinical observation (in Chinese). Herald Med. (2007) 26:1145–6. 10.3870/j.issn.1004-0781.2007.10.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wang XF, Guo HL, Sun KF. Effect of aripiprazole on higher plasma prolactin level caused antipsychotic drugs in female schizophrenic patients (in Chinese). J Clin Psychiatry. (2018) 28:125–7. 10.3969/j.issn.1005-3220.2018.02.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang YG, Huang LG. Research on treatment of glucose and lipid metabolism disorder in patients with Quetiapine-induced schizophrenia with Metformin (in Chinese). China Modern Med. (2016) 23:156–9. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yue LF. The effection of Jiawei Shaoyao Gancao decoction in treating hyperprolactinemia caused by antipsychotics and cognitive function (Thesis in Chinese). Henan: Xinxiang Medical University; (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 85.Man SC, Li XB, Wang HH, Yuan HN, Wang HN, Zhang RG, et al. Peony-glycyrrhiza decoction for antipsychotic-related hyperprolactinemia in women with schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2016) 36:572–9. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wang ZH, Gan B, Zhou H. Efects of aripiprazole on the antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia (in Chinese). Acta Acad Med Wannan. (2017) 36:143–5. 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0217.2017.02.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xu LP, Ji JY, Shi H, Zhai FL, Zhang B, Shao YQ, et al. A control study of aripiprazole in the treatment of hyperprolactinemia by antipsychotics origin (in Chinese). Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. (2006) 15:718–20. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1674-6554.2006.08.019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Shim JC, Shin JG, Kelly DL, Jung DU, Seo YS, Liu KH, et al. Adjunctive treatment with a dopamine partial agonist, aripiprazole, for antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: a placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. (2007) 164:1404–10. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Kane JM, Correll CU, Goff DC, Kirkpatrick B, Marder SR, Vester-Blokland E, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 16-week study of adjunctive aripiprazole for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder inadequately treated with quetiapine or risperidone monotherapy. J Clin Psychiatry. (2009) 70:1348–57. 10.4088/JCP.09m05154yel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Balijepalli C, Druyts E, Zoratti MJ, Wu P, Kanji S, Rabheru K, et al. Change in prolactin levels in pediatric patients given antipsychotics for schizophrenia and schizophrenia spectrum disorders: a network meta-analysis. Schizophr Res Treat. (2018) 2018:1543034. 10.1155/2018/1543034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Meng M, Li W, Zhang S, Wang H, Sheng J, Wang J, et al. Using aripiprazole to reduce antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of currently available randomized controlled trials. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. (2015) 27:4–17. 10.11919/j.issn.1002-0829.215014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yasui-Furukori N, Furukori H, Sugawara N, Fujii A, Kaneko S. Dose-dependent effects of adjunctive treatment with aripiprazole on hyperprolactinemia induced by risperidone in female patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2010) 30:596–9. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181ee832d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grunder G, Fellows C, Janouschek H, Veselinovic T, Boy C, Brocheler A, et al. Brain and plasma pharmacokinetics of aripiprazole in patients with schizophrenia: an [18F]fallypride PET study. Am J Psychiatry. (2008) 165:988–95. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sogawa R, Shimomura Y, Minami C, Maruo J, Kunitake Y, Mizoguchi Y, et al. Aripiprazole-associated hypoprolactinemia in the clinical setting. J Clin Psychopharmacol. (2016) 36:385–7. 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, De Hert M. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs. (2014) 28:421–53. 10.1007/s40263-014-0157-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Haddad PM, Wieck A. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinaemia: mechanisms, clinical features and management. Drugs. (2004) 64:2291–314. 10.2165/00003495-200464200-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Genazzani AD, Battaglia C, Malavasi B, Strucchi C, Tortolani F, Gamba O. Metformin administration modulates and restores luteinizing hormone spontaneous episodic secretion and ovarian function in nonobese patients with polycystic ovary syndrome. Fertil Steril. (2004) 81:114–9. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Billa E, Kapolla N, Nicopoulou SC, Koukkou E, Venaki E, Milingos S, et al. Metformin administration was associated with a modification of LH, prolactin and insulin secretion dynamics in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome. Gynecol Endocrinol. (2009) 25:427–34. 10.1080/09513590902770172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Krysiak R, Kowalcze K, Szkrobka W, Okopien B. The effect of metformin on prolactin levels in patients with drug-induced hyperprolactinemia. Eur J Intern Med. (2016) 30:94–98. 10.1016/j.ejim.2016.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Mann WA. Treatment for prolactinomas and hyperprolactinaemia: a lifetime approach. Eur J Clin Invest. (2011) 41:334–42. 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2010.02399.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Sahin M, Tutuncu NB, Ertugrul D, Tanaci N, Guvener ND. Effects of metformin or rosiglitazone on serum concentrations of homocysteine, folate, and vitamin B12 in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Complicat. (2007) 21:118–23. 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2005.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crespo-Facorro B, Ortiz-Garcia de la Foz V, Suarez-Pinilla P, Valdizan EM, Perez-Iglesias R, Amado-Senaris JA, et al. Effects of aripiprazole, quetiapine and ziprasidone on plasma prolactin levels in individuals with first episode nonaffective psychosis: analysis of a randomized open-label 1 year study. Schizophr Res. (2017) 189:134–141. 10.1016/j.schres.2017.01.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Miura I, Zhang JP, Hagi K, Lencz T, Kane JM, Yabe H, et al. Variants in the DRD2 locus and antipsychotic-related prolactin levels: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. (2016) 72:1–10. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2016.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.