Abstract

Calcium signaling in vascular smooth muscle is crucial for arterial tone regulation and vascular function. Several proteins, including Ca2+ channels, function in an orchestrated fashion so that blood vessels can sense and respond to physiological stimuli such as changes in intravascular pressure. Activation of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel, Cav1.2, leads to Ca2+ influx and consequently arterial tone development and vasoconstriction. Unique among Ca2+ channels, the vascular Cav3.2 T-type channel mediates feedback inhibition of arterial tone—and therefore causes vasodilation—of resistance arteries by virtue of functional association with hyperpolarizing ion channels. During aging, several signaling modalities are altered along with vascular remodeling. There is a growing appreciation of how calcium channel signaling alters with aging and how this may affect vascular function. Here, we discuss key determinants of arterial tone development and the crucial involvement of Ca2+ channels. We next provide an updated view of key changes in Ca2+ channel expression and function during aging and how these affect vascular function. Further, this article synthesizes new questions in light of recent developments. We hope that these questions will outline a roadmap for new research, which, undoubtedly, will unravel a more comprehensive picture of arterial tone dysfunction during aging.

Keywords: Myogenic tone, Calcium channel, Vascular smooth muscle, Aging, T-type

1. Vascular tone development

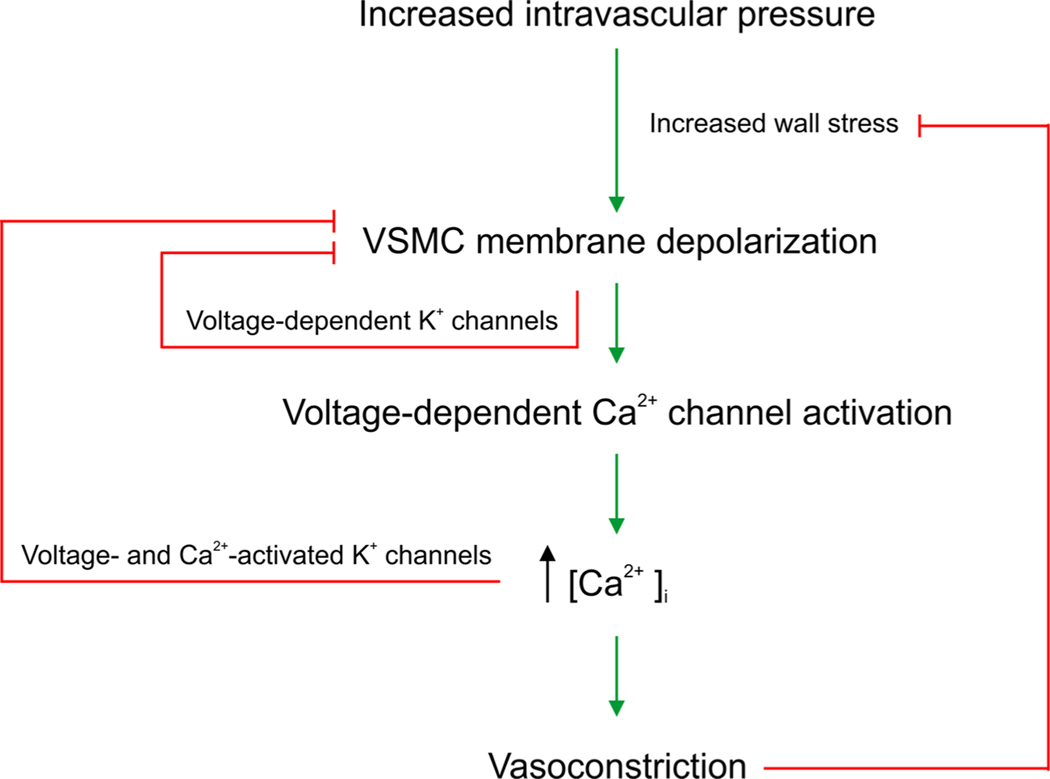

Blood vessels have the ability to change their diameter in response to physiological variables such as local neurotransmitter release and hemodynamic forces. The notion that small arteries and arterioles constrict and dilate to increases and decreases in intravascular pressure, respectively, was first reported by Bayliss (Bayliss, 1902). This phenomenon is known as the myogenic response and is a key feature of resistance arteries (Bayliss, 1902; Knot and Nelson, 1998). A crucial cascade in the so-called myogenic response involves vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) depolarization in response to elevated pressure leading to the opening of L-type voltage-dependent Ca2+ (Cav1.2) channels, Ca2+ influx, VSMC contraction and ultimately vasoconstriction (Fig. 1) (Knot and Nelson, 1998). Cav1.2 channels are therefore crucial determinants of peripheral vascular resistance and blood pressure (Moosmang et al., 2003), which is the basis for the use of calcium channel blockers for the treatment of hypertension. Notably, negative feedback mechanisms, that are intrinsic to VSMCs, help attenuate arterial tone and limit excessive vasoconstriction. Smooth muscle feedback mechanisms involve the activation of hyperpolarizing K+ channels such as the voltage-activated K+ channel (Kv) and the voltage-and Ca2+-activated, big conductance K+ channel (BKCa). While Ca2+ signaling is crucial for arterial tone development and the myogenic response, localized microdomain Ca2+ signaling is an established trigger for feedback BKCa channels that counteract vasoconstriction (Fig. 1) (Nelson et al., 1995; Nelson and Quayle, 1995).

Fig. 1.

A schematic illustrates arterial tone development and shows that increases in arterial transmural pressure (hereby wall stress is increased) depolarize vascular smooth muscle and activate Ca2+influx through voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels. The increase in cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) evokes vasoconstriction. Negative feedback mechanisms activated by VSMC depolarization (e.g., voltage-dependent K+ channels) or Ca2+ and depolarization (BKCa channel) counteract arterial tone development and prevent excessive vasoconstriction. Feed-forward of this cascade at prolonged increased pressure is terminated when wall stress is normalized by vasoconstriction. Wall stress (S) is wall tension (pressure times radius; P⋅r) divided by wall thickness (h): [S =P ⋅r /h].

2. Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in vascular smooth muscle

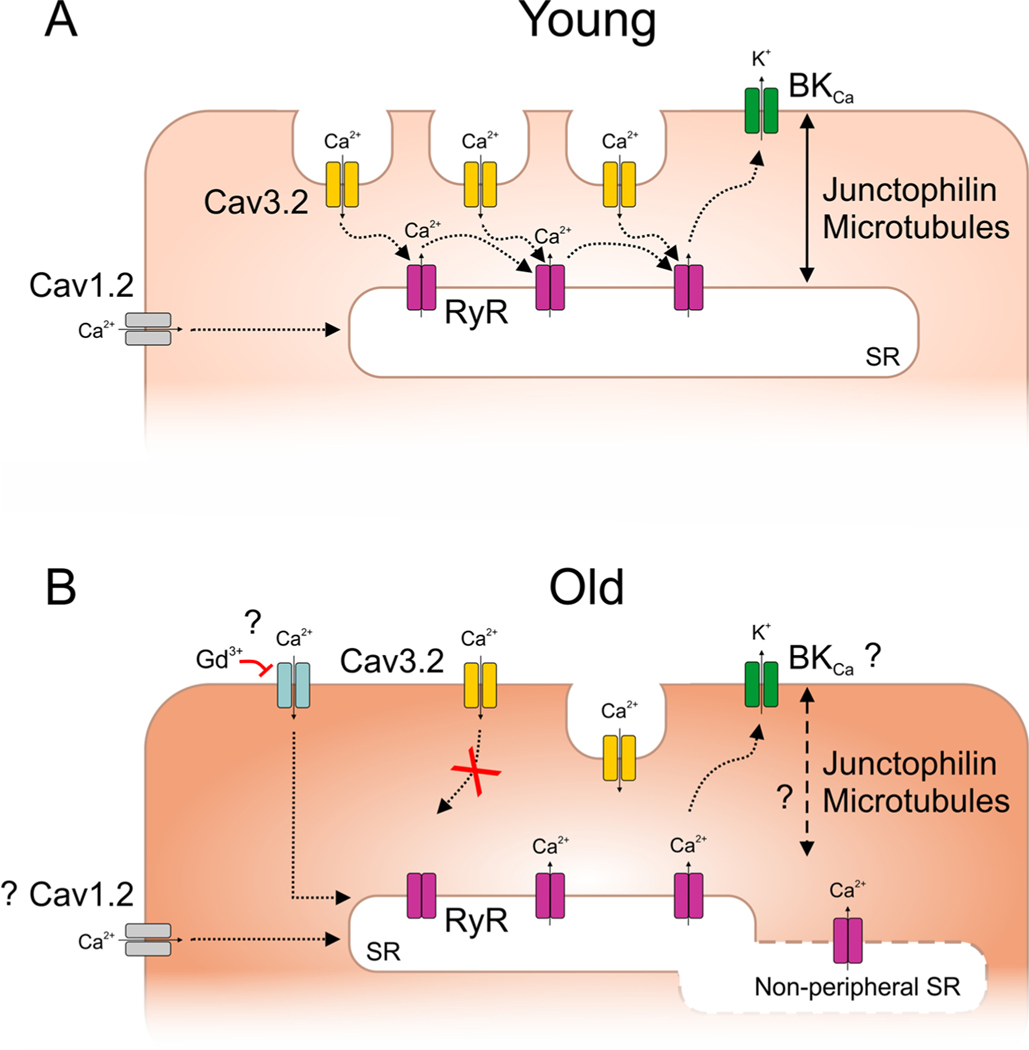

Voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel family comprises 10 members divided into 3 subfamilies, based on their biophysical and pharmacological properties; the Cav1 family (Cav1.1, 1.2, 1.3 and 1.4), the Cav2 family (Cav2.1, 2.2 and 2.3), and the Cav3 family (Cav3.1, 3.2 and 3.3). Over the past years, evidence has accumulated that VSMCs express additional voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels other than Cav1.2, and particularly T-type (Cav3.x) channels have received attention (For reviews, see: Hansen, 2013; Jensen and Holstein-Rathlou, 2009; Jensen et al., 2017). Cav3.1 and Cav3.3 subtypes are differentially expressed in rodents and humans, Cav3.2 channel on the other hand has been consistently reported in different vascular beds and species (Abd El-Rahman et al., 2013; Björling et al., 2013; Braunstein et al., 2009; Chen et al., 2003; Harraz et al., 2014; Harraz et al., 2015b; Harraz and Welsh, 2013; Kuo et al., 2010; Mikkelsen et al., 2016; Vanlandewijck et al., 2018). Despite the low unitary conductance of T-type channels (Perez-Reyes et al., 1998), Cav3.2 channel has an important role in local microdomain signaling to hyperpolarize VSMCs (Fig. 2) (Chen et al., 2003; Harraz et al., 2014). Cav3.2-mediated Ca2+ influx stimulates the cytosolic domain of ryanodine receptors (RyRs) to release Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in the form of Ca2+ sparks (Harraz et al., 2014). The latter are crucial for the activation of BKCa channels leading to K+ efflux and hyperpolarization (Chen et al., 2003; Harraz et al., 2014; Harraz et al., 2015a; Hashad et al., 2017, 2018; Nelson et al., 1995). In order for this signaling to function properly, Cav3.2 channels have to be arranged in close apposition to RyRs. Structural analyses have revealed that Cav3.2 are preferentially localized in plasma membrane invaginations, known as caveolae (Fig. 2) (Harraz et al., 2014). This localization is critical for the functional ability of Cav3.2 to trigger Ca2+ sparks and therefore the feedback inhibition of vasoconstriction (Fan et al., 2018; Hashad et al., 2018). It should be noted, however, that several reports suggested reduced functional coupling between BKCa channels and RyRs in small-diameter arterioles despite the expression of functional BKCa channels and RyRs (Dabertrand et al., 2012; Horiuchi et al., 2002; Taguchi et al., 1995). In particular, BKCa blockers had little effect on cerebral arteriolar diameter (Dabertrand et al., 2012), in a stark contrast to upstream cerebral arteries that constricted robustly to BKCa blockers (Knot et al., 1998; Nelson et al., 1995).

Fig. 2.

Proposed VSMC model for interaction between arterial Cav3.2 channels and RyR/BKCa axis in young (A) vs. old mice (B) according to recent literature. For further details, see text. “?” denotes uncertain or mixed reports.

3. Aging alters L-type Ca2+ channel expression and function

Cardiovascular aging associates with stiffening of large arteries, which elevates systolic blood pressure and pulse pressure (Lakatta, 1989, 2015). Moreover, the Framingham Heart Study showed that mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) increased steadily with age in men and women until the age of ~70, whereafter the MAP trajectory was relatively flat (Cheng et al., 2012). Aging and hypertension, as individual risk factors and particularly in combination, contribute considerably to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular morbidity and mortality. Several studies have shown that age affects vascular L-type calcium channel function. For instance, the protein expression of the pore-forming α1Csubunit of the Cav1.2 L-type channel was downregulated in the aortae of 10-month old Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats (SHR) and their normotensive Wistar-Kyoto (WKY) control rats compared to 2-month old rats (Fukuda et al., 2014). Additionally, mRNA and protein levels of Cav1.2 channels were reduced in mesenteric arteries of 16-month old SHR and WKY rats, compared to 3-month old rats (Liao et al., 2017). Interestingly, the decrease in Cav1.2 channel expression with aging was mirrored by increased expression of miR-328, an epigenetic regulator capable of suppressing Cav1.2 mRNA and protein expression in cultured VSMCs. These findings suggested that vascular L-type Ca2+ channels are targets of epigenetic regulation; conceptually, this could be implicated in aging-related vascular effects (Liao et al., 2017). However, L-type Ca2+ channel current density in coronary artery VSMCs was not different in young (4-month) versus aged (24-month) male F344 rats (Korzick et al., 2005). In distinction, a reduced mRNA expression of Cav1.2 channel in posterior and middle cerebral arteries from old (20–22-month) vs. young (2–3 months) mice was associated with a decreased depolarization-induced vasoconstriction in old mice (Georgeon-Chartier et al., 2013).

In contrast to observations of aging-associated decrease in Cav1.2 expression, DuPont and colleagues reported an increase in Cav1.2 mRNA expression in aged mesenteric arteries (12–15-month) as compared with young mice (3–4 months) (DuPont et al., 2016). This increased Cav1.2 expression by age was concomitantly associated with reduced miR-155 expression. In fact, restoring miR-155 expression in VSMCs from aged mice decreased Cav1.2 expression and attenuated L-type channel-mediated vasoconstriction (DuPont et al., 2016). However, another study showed that L-type current density in small mesenteric artery VSMCs was preserved in old mice (30-month) compared to young mice (6-month); indicating that the functional expression of L-type channels was unchanged (Del Corsso et al., 2006). In another study, no difference was detected between Cav1.2 mRNA expression or depolarization-induced vasoconstriction between small mesenteric arteries from young (2–4-month) and aged (7–13-month) mice (Mikkelsen et al., 2016).

To summarize, there are discrepancies whether aging evokes alterations in vascular L-type channel expression and/or function. These discrepancies between different studies could attribute to investigating different arterial beds, different animal models or different species. It could also be related to inconsistencies in the age-span between young and old counterparts in different studies (see Towards consistency in defining aging in rodents).

4. Aging and T-type Ca2+ channels

Age-dependent changes in the expression and function of T-type Ca2+ channels have been reported, such as functional downregulation in cardiomyocytes from several species (Ono and Iijima, 2010; Vassort et al., 2006), and reduced Cav3.1 channel expression in several brain areas in mice and humans (Rice et al., 2014). Importantly, vascular Cav3.1 expression, in small mesenteric arteries, was downregulated at the mRNA and protein levels in 7–13-month old mice compared to young mice (2–4-month) (Mikkelsen et al., 2016).

4.1. Aging suppresses Cav3.2 T-type Ca2+ channel activity

We have shown that pharmacological inhibition of vascular Cav3.2 channels evokes vasoconstriction and enhances the myogenic tone of cerebral and mesenteric arteries (Harraz et al., 2014; Harraz et al., 2015a, b; Mikkelsen et al., 2016), consistent with the role for Cav3.2 in the Cav3.2-RyR-BKCa signaling axis (Fig. 2). While Cav3.2 blockade enhanced the myogenic tone in small mesenteric arteries from young mice (2–4-month), the same maneuver, however, had no effect in aged mice (7–13-month) (Mikkelsen et al., 2016), suggesting a loss in the Cav3.2 signaling during aging. Furthermore, studies in Cav3.2-deficient mice unraveled an age-dependent role of Cav3.2 in modulating pressure-dependent arterial tone. In particular, there was no difference in the myogenic tone of mesenteric arteries between aged Cav3.2 knock-out (KO) and wild-type (WT) mice (Mikkelsen et al., 2016), despite an enhanced tone in young Cav3.2 KO mice compared to WT controls (Harraz et al., 2015a; Mikkelsen et al., 2016). Furthermore, specific BKCa channel blockers enhanced myogenic tone in young WT mice, but had no effect in Cav3.2 KO mice, confirming the functional coupling between Cav3.2 channels and negative modulation of myogenic tone by BKCa channels and suggesting Cav3.2-BKCa uncoupling during aging (Fig. 2) (Mikkelsen et al., 2016).

A recent study further explored how aging affects Cav3.2-RyR-BKCa signaling in VSMCs (Fan et al., 2020). Using mice of different ages (4 vs. 12-month) and high spatial resolution confocal Ca2+ imaging in VSMCs, the authors showed that aging disrupts the Cav3.2-to-RyR coupling. Protein expression analyses and electron microscopy further revealed that the disruption was likely caused by age-related reduction in Cav3.2 protein expression and structural changes in VSMC caveolae (Fig. 2). The latter membrane structures are essential for Cav3.2 channels to be localized within nanometer-range distance from RyR to enable Ca2+ influx to trigger Ca2+ sparks (Fan et al., 2018, 2019; Hashad et al., 2018; Lian et al., 2019). Moreover, Gollasch and colleagues investigated the contribution of other Ca2+ influx pathways to Ca2+ spark characteristics using pharmacological tools as well as targeted and conditional Cav1.2 channel deletion in VSMCs. In accordance with previous reports (Fan et al., 2018; Hashad et al., 2017; Takeda et al., 2011), Cav3.2 and Cav1.2 channels were together the major contributor to overall Ca2+ spark generation in young mice. Cav3.2 contribution, however, disappeared in old mice—consistent with previous findings (Mikkelsen et al., 2016)— and was replaced by a pathway sensitive to the non-selective channel blocker gadolinium (Gd3+) (Fan et al., 2020) (Fig. 2). It is worthwhile noting that previous studies showed that the expression of the Gd3+-sensitive canonical transient receptor potential TRPC6 channels was not altered in young versus aged mouse mesenteric arteries (Mikkelsen et al., 2016; Toth et al., 2013). Experiments with pressurized arteries confirmed that pharmacological Cav3.2 inhibition had no effect in old mice, consistent with the loss of function of Cav3.2/RyR/BKCa signaling with aging (Fan et al., 2020). Altogether, these observations support the evidence that caveolae are critical for vascular function, not only in VSMCs (Fan et al., 2019, 2018; Hashad et al., 2018; Insel and Patel, 2009), but also in endothelial cells (Chow et al., 2020; Frank et al., 2003).

4.2. Further aspects of aging and Cav3.2 function

A previous study in human cerebral VSMCs did not detect a change in T-type channel activity in older subjects (Harraz et al., 2015b), which presumably aligns with a change downstream of Cav3.2 activation (i.e., coupling to RyRs) but not necessarily a decline in Cav3.2 protein expression. Furthermore, genetic ablation of Cav3.2 channel in mice was not associated with age-related changes in Cav1.2, BKCa or TRPC1/3/6 mRNA expression (Mikkelsen et al., 2016). Previous and recent observations (Fan et al., 2020; Mikkelsen et al., 2016) collectively suggest that Cav3.2 function in small arteries at a young age protects against excessive myogenic constriction, a role that is lost with advanced age. Morel and colleagues have reported key changes to Ca2+ signaling in cerebral VSMCs in aged mice: reduced RyR-mediated Ca2+ signals, SR refilling, Cav1.2 and RyR2 gene expression, and depolarization-induced vasoconstriction (Georgeon-Chartier et al., 2013), all of which could affect the Cav3.2/RyR/BKCa signaling axis. Several studies, however, reported discrepant findings regarding an age-dependent change in BKCa channel expression and function (Albarwani et al., 2010; Carvalho--de-Souza et al., 2013; Hayoz et al., 2014; Marijic et al., 2001).

Because different age stages could be associated with differential effects on different vascular beds, it would be crucial to assess the Cav3.2/RyR/BKCa axis at different ages, in both sexes, and in different arteries (e.g., cerebral, skeletal and mesenteric). Additionally, the functional coupling between intermediary RyRs and BKCa channels needs to be considered. Recent evidence showed that structural elements and proteins (microtubules and junctophilin-2) are essential for maintaining close contacts between VSMC plasma membrane and the SR to modulate contractility (Pritchard et al., 2017, 2019). Whether these structural elements change during aging remains to be tested. In fact, less peripheral localization of sub-membranous SR in aged human mesenteric VSMCs has been reported (Dai et al., 2010), but whether such subcellular changes can be generalized is unknown (Fig. 2). It is conceivable to speculate that structural changes during aging position the SR further away from the plasma membrane and caveolae. While Cav1.2 L-type channels under these circumstances (i.e., distant SR from plasma membrane) would still refill the SR Ca2+ content and facilitate RyR/BKCa activity, Cav3.2 channels would most likely not due to disrupted Cav3.2-to-RyR coupling. Conceptually, the age-dependent loss of arterial Cav3.2/RyR/BKCa signaling could, theoretically, lead to enhanced peripheral resistance and increased blood pressure. However, blood pressure was normal in young Cav3.2−/− mice (Harraz et al., 2015a; Thuesen et al., 2014). Fan and colleagues suggested that Ca2+ influx via Gd3+-sensitive channel(s) may represent a compensatory mechanism to maintain RyR/BKCa functionality in aging; the molecular identity and role of this gadolinium-sensitive mechanism remain to be unraveled (Fig. 2).

5. Towards consistency in defining aging in rodent studies

Throughout this review, the referenced studies have used several different age spans to define “young” vs. “old” mice and rats. However, we believe it would be useful for aging studies to employ well-defined, standard age stages for mature adult mice (3–6-month), middle-aged mice (10–14-month), and old mice (18–24-month) (Flurkey et al., 2007). The life expectancy of a laboratory rat is about 2.5–3 years (30–36 months). Rats become sexually mature at ~2 months of age, but mature adulthood may not be reached until the skeletal growth tapers off at about 7–8 months of age. Reproductive senescence of (female) rats is reached at 15–20 months of age (Pallav Sengupta, 2013; Quinn, 2005). Going by these lifecycle events, we may suggest using the following standard age stages in future aging research in rats: mature adult rats (7–10-month), middle-aged rats (12–18-month), and old rats (22–30-month). Nevertheless, care should be taken when comparing age-related phenomena in rodents and humans due to the obvious differences in anatomy, physiology and normal development.

6. Concluding remarks

In conclusion, recent studies contribute to our developing understanding of calcium channel signaling and the origins of negative feedback control of the myogenic tone in resistance arteries and the impact of aging. With that said, it begs more questions to be answered to unravel a more comprehensive picture of the mechanistic changes underlying altered contractility of arteries in the aging human population.

Acknowledgements

OFH was supported by a Career Development Award (20CDA35310097) and a Postdoctoral Fellowship (17POST33650030) from the American Heart Association, and a Career Development Award from the Cardiovascular Research Institute at the University of Vermont. LJJ was supported by The Danish Council for Independent Research-Medical Sciences, Danish Agency for Science and Higher Education, The Novo Nordisk Foundation, The Danish Heart Foundation, and The A.P. Møller Foundation for the Advancement of Medical Science.

Footnotes

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

References

- Abd El-Rahman RR, Harraz OF, Brett SE, Anfinogenova Y, Mufti RE, Goldman D, Welsh DG, 2013. Identification of L-and T-type Ca2+ channels in rat cerebral arteries: role in myogenic tone development. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 304 (1), H58–71. 10.1152/ajpheart.00476.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albarwani S, Al-Siyabi S, Baomar H, Hassan MO, 2010. Exercise training attenuates ageing-induced BKCa channel downregulation in rat coronary arteries. Exp. Physiol 95 (6), 746–755. 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.051250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss WM, 1902. On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. J. Physiol 28 (3), 220–231. 10.1113/jphysiol.1902.sp000911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Björling K, Morita H, Olsen MF, Prodan A, Hansen PB, Lory P, Jensen LJ, 2013. Myogenic tone is impaired at low arterial pressure in mice deficient in the low-voltage-activated CaV3.1 T-type Ca2+ channel. Acta Physiol. 207 (4), 709–720. 10.1111/apha.12066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunstein TH, Inoue R, Cribbs L, Oike M, Ito Y, Holstein-Rathlou N-H, Jensen LJ, 2009. The role of L-and T-type calcium channels in local and remote calcium responses in rat mesenteric terminal arterioles. J. Vasc. Res 46 (2), 138–151. 10.1159/000151767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carvalho-de-Souza JL, Varanda WA, Tostes RC, Chignalia AZ, 2013. BK channels in cardiovascular diseases and aging. Aging Dis. 10.14336/ad.2013.040038. International Society on Aging and Disease. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CC, Lamping KG, Nuno DW, Barresi R, Prouty SJ, Lavoie JL, Campbell KP, 2003. Abnormal coronary function in mice deficient in α1H T-type Ca2+ channels. Science 302 (5649), 1416–1418. 10.1126/science.1089268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Xanthakis V, Sullivan LM, Vasan RS, 2012. Blood pressure tracking over the adult life course: patterns and correlates in the Framingham heart study. Hypertension (Dallas, Tex.: 1979) 60 (6), 1393–1399. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.201780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow BW, Nuñez V, Kaplan L, Granger AJ, Bistrong K, Zucker HL, Gu C, 2020. Caveolae in CNS arterioles mediate neurovascular coupling. Nature 579 (7797), 106–110. 10.1038/s41586-020-2026-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabertrand F, Nelson MT, Brayden JE, 2012. Acidosis dilates brain parenchymal arterioles by conversion of calcium waves to sparks to activate BK channels. Circ. Res 110 (2), 285–294. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai JM, Syyong H, Navarro-Dorado J, Redondo S, Alonso M, van Breemen C, Tejerina T, 2010. A comparative study of alpha-adrenergic receptor mediated Ca2+ signals and contraction in intact human and mouse vascular smooth muscle. Eur. J. Pharmacol 629 (1–3), 82–88. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.11.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Corsso C, Ostrovskaya O, McAllister CE, Murray K, Hatton WJ, Gurney AM, Wilson SM, 2006. Effects of aging on Ca2+ signaling in murine mesenteric arterial smooth muscle cells. Mech. Ageing Dev 127 (4), 315–323. 10.1016/j.mad.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPont JJ, McCurley A, Davel AP, McCarthy J, Bender SB, Hong K, Jaffe IZ, 2016. Vascular mineralocorticoid receptor regulates microRNA-155 to promote vasoconstriction and rising blood pressure with aging. JCI Insight 1 (14). 10.1172/jci.insight.88942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Kaßmann M, Hashad AM, Welsh DG, Gollasch M, 2018. Differential targeting and signalling of voltage-gated T-type Cav3.2 and L-type Cav1.2 channels to ryanodine receptors in mesenteric arteries. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 596 (20), 4863–4877. 10.1113/JP276923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Cui Y, Gollasch M, Kassmann M, 2019. Elementary calcium signaling in arterial smooth muscle. Channels (Austin, Tex.) 13 (1), 505–519. 10.1080/19336950.2019.1688910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan G, Kaßmann M, Cui Y, Matthaeus C, Kunz S, Zhong C, Gollasch M, 2020. Age attenuates the T-type CaV3.2-RyR axis in vascular smooth muscle. Aging Cell. 10.1111/acel.13134e13134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flurkey K, Currer J, Harrison D, 2007. Mouse models in aging research. Faculty Research 2000–2009. Retrieved from. https://mouseion.jax.org/stfb2000_2009/1685. [Google Scholar]

- Frank PG, Woodman SE, Park DS, Lisanti MP, 2003. Caveolin, caveolae, and endothelial cell function. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 10.1161/01.ATV.0000070546.16946.3A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T, Kuroda T, Kono M, Miyamoto T, Tanaka M, Matsui T, 2014. Attenuation of L-type Ca2+ channel expression and vasomotor response in the aorta with age in both Wistar-Kyoto and spontaneously hypertensive rats. PLoS One 9 (2). 10.1371/journal.pone.0088975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgeon-Chartier C, Menguy C, Prévot A, Morel J-L, 2013. Effect of aging on calcium signaling in C57Bl6J mouse cerebral arteries. Pflugers Arch. 465 (6), 829–838. 10.1007/s00424-012-1195-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen PBL, 2013. Functional and pharmacological consequences of the distribution of voltage-gated calcium channels in the renal blood vessels. Acta Physiol. (Oxf. Engl.) 207 (4), 690–699. 10.1111/apha.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Welsh DG, 2013. Protein kinase a regulation of T-type Ca2+ channels in rat cerebral arterial smooth muscle. J. Cell. Sci 126 (13) 10.1242/jcs.128363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Abd El-Rahman RR, Bigdely-Shamloo K, Wilson SM, Brett SE, Romero M, Welsh DG, 2014. CaV3.2 channels and the induction of negative feedback in cerebral arteries. Circ. Res 115 (7) 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.304056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Brett SE, Zechariah A, Romero M, Puglisi JL, Wilson SM, Welsh DG, 2015a. Genetic ablation of CaV3.2 channels enhances the arterial myogenic response by modulating the RyR-BKCa axis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 35 (8) 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harraz OF, Visser F, Brett SE, Goldman D, Zechariah A, Hashad AM, Welsh DG, 2015b. CaV1.2/CaV3.x channels mediate divergent vasomotor responses in human cerebral arteries. J. Gen. Physiol 145 (5) 10.1085/jgp.201511361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashad AM, Mazumdar N, Romero M, Nygren A, Bigdely-Shamloo K, Harraz OF, Welsh DG, 2017. Interplay among distinct Ca2+ conductances drives Ca2+ sparks/spontaneous transient outward currents in rat cerebral arteries. J. Physiol 595 (4), 1111–1126. 10.1113/JP273329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashad AM, Harraz OF, Brett SE, Romero M, Kassmann M, Puglisi JL, Welsh DG, 2018. Caveolae link CaV3.2 channels to BKCa-mediated feedback in vascular smooth muscle. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 38 (10), 2371–2381. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayoz S, Bradley V, Boerman EM, Nourian Z, Segal SS, Jackson WF, 2014. Aging increases capacitance and spontaneous transient outward current amplitude of smooth muscle cells from murine superior epigastric arteries. Am. J. Physiol. -Heart Circ. Physiol 306 (11), H1512–1524. 10.1152/ajpheart.00492.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horiuchi T, Dietrich HH, Hongo K, Dacey RG, 2002. Mechanism of extracellular K +-induced local and conducted responses in cerebral penetrating arterioles. Stroke 33 (11), 2692–2699. 10.1161/01.STR.0000034791.52151.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel PA, Patel HH, 2009. Membrane rafts and caveolae in cardiovascular signaling. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens 18 (1), 50–56. 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3283186f82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Nielsen MS, Salomonsson M, Sørensen CM, 2017. T-type Ca2+ channels and autoregulation of local blood flow. Channels 11 (3), 183–195. 10.1080/19336950.2016.1273997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen LJ, Holstein-Rathlou N-H, 2009. Is there a role for T-type Ca2+ channels in regulation of vasomotor tone in mesenteric arterioles? Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 87 (1), 8–20. 10.1139/Y08-101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Nelson MT, 1998. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J. Physiol 508 (1), 199–209. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.199br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knot HJ, Standen NB, Nelson MT, 1998. Ryanodine receptors regulate arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat via Ca2+-dependent K+ channels. J. Physiol 508 (1), 211–221. 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.211br.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korzick DH, Muller-Delp JM, Dougherty P, Heaps CL, Bowles DK, Krick KK, 2005. Exaggerated coronary vasoreactivity to endothelin-1 in aged rats: role of protein kinase C. Cardiovasc. Res 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo IY, Ellis A, Seymour VA, Sandow SL, Hill CE, 2010. Dihydropyridine-insensitive calcium currents contribute to function of small cerebral arteries. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 30 (6), 1226–1239. 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta EG, 1989. Arterial pressure and aging. Int. J. Cardiol 25 (Suppl 1(SUPPL. 1)), S81–89. 10.1016/0167-5273(89)90097-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakatta Edward G., 2015. So! What’s aging? Is cardiovascular aging a disease? J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 83, 1–13. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian X, Matthaeus C, Kaßmann M, Daumke O, Gollasch M, 2019. Pathophysiological role of caveolae in hypertension. Front. Med 6, 153. 10.3389/fmed.2019.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao J, Zhang Y, Ye F, Zhang L, Chen Y, Zeng F, Shi L, 2017. Epigenetic regulation of L-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channels in mesenteric arteries of aging hypertensive rats. Hypertens. Res 40 (5), 441–449. 10.1038/hr.2016.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marijic J, Li Q, Song M, Nishimaru K, Stefani E, Toro L, 2001. Decreased expression of voltage-and Ca2+-activated K+ channels in coronary smooth muscle during aging. Circ. Res 88 (2), 210–216. 10.1161/01.res.88.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen MF, Björling K, Jensen LJ, 2016. Age-dependent impact of CaV3.2 T-type calcium channel deletion on myogenic tone and flow-mediated vasodilatation in small arteries. J. Physiol 594 (20), 5881–5898. 10.1113/JP271470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Schulla V, Welling A, Feil R, Feil S, Wegener JW, Klugbauer N, 2003. Dominant role of smooth muscle L-type calcium channel Cav1.2 for blood pressure regulation. EMBO J. 22 (22), 6027–6034. 10.1093/emboj/cdg583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Quayle JM, 1995. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol 268 (4 Pt 1), C799–822. 10.1152/ajpcell.1995.268.4.C799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, Santana LF, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, Lederer WJ, 1995. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science (New York, N. Y.) 270 (5236), 633–637. 10.1126/science.270.5236.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ono K, Iijima T, 2010. Cardiac T-type Ca2+ channels in the heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol 48 (1), 65–70. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta Pallav, 2013. The laboratory rat : relating its age with human’s. Int. J. Prev. Med 4 (6), 624–630. Retrieved from /pmc/articles/PMC3733029/?report=abstract. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes E, Cribbs LL, Daud A, Lacerda AE, Barclays J, Williamson MP, Lee JH, 1998. Molecular characterization of a neuronal low-voltage-activated T-type calcium channel. Nature 391 (6670), 896–900. 10.1038/36110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard HAT, Gonzales AL, Pires PW, Drumm BT, Ko EA, Sanders KM, Earley S, 2017. Microtubule structures underlying the sarcoplasmic reticulum support peripheral coupling sites to regulate smooth muscle contractility. Sci. Signal 10 (497) 10.1126/scisignal.aan2694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard HAT, Griffin CS, Yamasaki E, Thakore P, Lane C, Greenstein AS, Earley S, 2019. Nanoscale coupling of junctophilin-2 and ryanodine receptors regulates vascular smooth muscle cell contractility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116 (43), 21874–21881. 10.1073/pnas.1911304116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn R, 2005. Comparing rat’s to human’s age: How old is my rat in people years? Nutrition. 10.1016/j.nut.2005.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice RA, Berchtold NC, Cotman CW, Green KN, 2014. Age-related downregulation of the CaV3.1 T-type calcium channel as a mediator of amyloid beta production. Neurobiol. Aging 35 (5), 1002–1011. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.10.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taguchi H, Heistad DD, Kitazono T, Faraci FM, 1995. Dilatation of cerebral arterioles in response to activation of adenylate cyclase is dependent on activation of Ca2+-Dependent K+ channels. Circ. Res 76 (6), 1057–1062. 10.1161/01.RES.76.6.1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda Y, Nystoriak MA, Nieves-Cintron M, Santana LF, Navedo MF, 2011. ´ Relationship between Ca2+ sparklets and sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ load and release in rat cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol 301 (6), H2285–H2294. 10.1152/ajpheart.00488.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thuesen AD, Andersen H, Cardel M, Toft A, Walter S, Marcussen N, Hansen PBL, 2014. Differential effect of T-type voltage-gated Ca2+ channel disruption on renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. -Renal Physiol 307 (4) 10.1152/ajprenal.00016.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth P, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Mitschelen M, Tarantini S, Ungvari Z, 2013. Age-related autoregulatory dysfunction and cerebromicrovascular injury in mice with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab 33 (11), 1732–1742. 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlandewijck M, He L, Mäe MA, Andrae J, Ando K, Del Gaudio F, Betsholtz C, 2018. A molecular atlas of cell types and zonation in the brain vasculature. Nature 554 (7693), 475–480. 10.1038/nature25739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassort G, Talavera K, Alvarez JL, 2006. Role of T-type Ca2+ channels in the heart. Cell Calcium 40 (2), 205–220. 10.1016/j.ceca.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]