Introduction

The mismatch repair (MMR) system maintains the genomic stability through the correction of base mispairing generated during DNA replication (1). Its deficiency has a relevant role in the tumorigenesis and tumor progression of a subset of breast cancers (2).

In an interesting study, Ren and collaborators (3) focus the attention on triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC). Using MMR immunohistochemistry (IHC) and microsatellite instability (MSI) PCR on a retrospective cohort of 440 patients, the Authors found only 1 (0.2%) MMR-deficient (dMMR) case, showing loss of MSH2 alone and low-frequency MSI (MSI-L). No MSI-high (MSI-H) tumors were observed, although overall 14 (7.2%) samples were MSI-L. The Authors confirm the low incidence of dMMR/MSI-H (4) and the high rate of discrepancy between MMR IHC/MSI PCR in TNBC (5). Finally, their analyses revealed no significant associations between MSI-L and other clinicopathological and prognostic features.

The topic is of great importance considering the growing interest on the implementation of consistent MMR testing for prognostication, immune checkpoints inhibitors (ICI) prediction, and identification of therapy resistance/susceptibility in both adjuvant and neoadjuvant settings (6–8). To date, in the neoadjuvant setting, several clinical trials have examined the efficacy of programmed death-1/programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) blockade in early high-risk TNBC (9–11). The results of the KEYNOTE-522 study have recently led to the approval of pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy for patients with locally recurrent unresectable or metastatic TNBC whose tumors express PD-L1 with combined positive score (CPS) ≥10 (10). Despite these remarkable achievements, additional biomarkers would be helpful in this setting. Therefore, this elegant work by Ron et al. is an excellent opportunity to reflect on the possibilities and challenges of MMR analysis for patients with TNBC.

Frequency and Spectrum of Mismatch Repair Alterations in TNBC

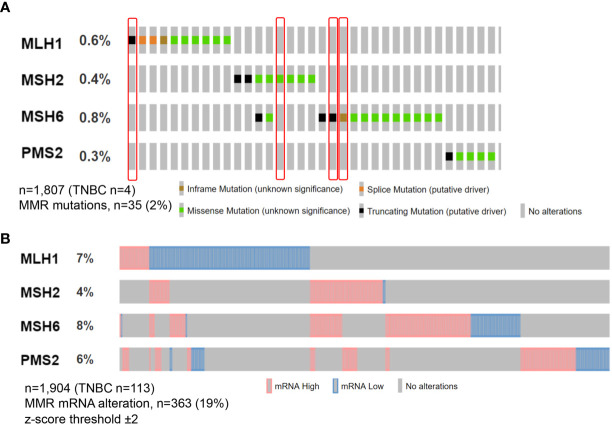

Types of MMR alterations described in TNBC, include gene mutations, hypermethylation, RNA downregulation, and alterations in the expression patterns of the protein complexes (5, 12–16). The actual frequency of dMMR in TNBC, however, is controversial, since MMR mutations are reported in ∼2% of cases, while an impaired protein expression seems to be more frequent (15, 17, 18), probably due to post-transcriptional modifications ( Figure 1 ). Interestingly, dMMR TNBC often present a single protein loss (19), as also noted by Ren et al.

Figure 1.

Oncoprint visualization of molecular alterations in the MMR genes in triple-negative breast cancer. Alterations across all breast cancer subtypes are color-coded on the basis of the legends on the bottom. Each column represents a sample, each row an MMR gene. Somatic MMR mutations (A) are seen in 35 (2%) of queried patients from MSK study with the majority showing missense mutation, while MMR mRNA alterations (B) in n = 363 (19%) from METABRIC study. Tumors included in this analysis have been retrieved from cbioportal.org.

The Rationale for MMR Clinical Testing in TNBC

The previously reported significant prognostic role of dMMR in TNBC (6, 15) has not been confirmed by Ren et al. because they found only 1 IHC dMMR and no MSI-H cases. In this respect, a study by our group focusing on MMR patterns of expression showed a better prognosis for TNBC tumors with MMR proteins perturbations (5). Regarding the predictive role, although data on MMR alterations in TNBC are still being generated (20), the existing evidence is limited and therefore, further studies to establish its clinical value are expected. Hence, only a few TNBC were included in the basket trials that led to the ICI MMR-based histology-agnostic approval (21). Furthermore, the notion that relates the sensitivity to ICI to the adaptative immune response against neo-antigens, generated by super-mutator cancer cells, is another facet that needs further clarification in TNBC (22). Indeed, the tumor mutation burden observed in dMMR TNBC is overall lower than in other types of dMMR cancers, albeit significantly higher than in hormone receptor (HR)-positive breast cancers (2, 23). The interaction between MMR and other immune-related biomarkers in TNBC could be explored in the near future to improve a tailored MMR testing. Lately, it has been shown that dMMR TNBC preferentially show high stromal T-cell predominant tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and higher expression of PD-L1 and CD8 than those with an MMR proficient status (4, 24). In another study, patients with TILs-high TNBC revealed an inverse correlation between MLH1 and PD-L1 expression in stromal immune cells (25). As pointed by Ren et al., large multicentric cohorts are needed improve our understanding of the relationship between MMR and the other actionable biomarkers in TNBC.

Currently Available Testing Methods and Guidelines

What we know so far is that MMR data in TNBC may vary according to the employed testing method, such as IHC for the four MMR proteins, MSI PCR, and next-generation sequencing (NGS) (26). Among these, IHC is usually employed as a first-line testing method due to its reliability, cost-effectiveness, and large availability (8, 27). Lately, we proposed phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) as a complementary biomarker in breast cancer, as its wild-type expression by IHC had a 100% positive predictive value for MMR proficiency in several subtypes, including TNBC (16). MSI analysis using mononucleotide markers, also employed by Ren et al., is a highly sensitive method, albeit not specific for breast cancer (28–31). Given that NGS-based panels can screen a larger number of microsatellite loci compared to RT-PCR and allow for the simultaneous identification of other actionable genetic alterations, this technology is currently gaining momentum in cancers with lower MSI-H/dMMR frequency, such as TNBC (32–35). Regrettably, all these methods are generally molded on those approved for the archetypal Lynch syndrome tumors, where MSI occurs way more frequently than in TNBC (colorectal cancer predominantly) (36). To ensure optimal specificity and sensitivity in breast cancer, these diagnostic strategies might need to be re-developed or at least re-validated.

Conclusion

The diagnosis and treatment of TNBC have remarkably progressed during the recent decades, yet many patients develop resistance to pharmacotherapy and die of this disease. The pathological identification of dMMR TNBC, albeit promising, has proven to be tremendously difficult due to the constraints of the existing methods and the scarcity of research. The study by Ren et al. represents another step forward in the discussion on the clinical utility of MMR testing in breast cancer. Further translational research studies and clinical trials encompassing tumor-specific guidelines for analytical and preanalytical phases are warranted to improve the characterization of the MMR status in TNBC.

Author Contributions

All the authors equally participated in the writing and reviewing of the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

NF has received honoraria for consulting, advisory role, and/or speaker bureau from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- 1. Pećina-Šlaus N, Kafka A, Salamon I, Bukovac A. Mismatch Repair Pathway, Genome Stability and Cancer. Front Mol Biosci (2020) 7:122–. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barroso-Sousa R, Jain E, Cohen O, Kim D, Buendia-Buendia J, Winer E, et al. Prevalence and Mutational Determinants of High Tumor Mutation Burden in Breast Cancer. Ann Oncol (2020) 31(3):387–94. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ren X -Y, Song Y, Wang J, Chen L-Y, Pang J-Y, Zhou L-R, et al. Mismatch Repair Deficiency and Microsatellite Instability in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Retrospective Study of 440 Patients. Front Oncol (2021) 11(368). doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.570623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wen YH, Brogi E, Zeng Z, Akram M, Catalano J, Paty PB, et al. DNA Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Breast Carcinoma: A Pilot Study of Triple-Negative and Non-Triple-Negative Tumors. Am J Surg Pathol (2012) 36(11):1700–8. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182627787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fusco N, Lopez G, Corti C, Pesenti C, Colapietro P, Ercoli G, et al. Mismatch Repair Protein Loss as a Prognostic and Predictive Biomarker in Breast Cancers Regardless of Microsatellite Instability. JNCI Cancer Spectr (2018) 2(4):pky056. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dasgupta H, Islam S, Alam N, Roy A, Roychoudhury S, Panda CK. Hypomethylation of Mismatch Repair Genes MLH1 and MSH2 Is Associated With Chemotolerance of Breast Carcinoma: Clinical Significance. J Surg Oncol (2019) 119(1):88–100. doi: 10.1002/jso.25304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Punturi NB, Seker S, Devarakonda V, Mazumder A, Kalra R, Chen CH, et al. Mismatch Repair Deficiency Predicts Response to HER2 Blockade in HER2-Negative Breast Cancer. Nat Commun (2021) 12(1):2940. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-23271-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Corti C, Sajjadi E, Fusco N. Determination of Mismatch Repair Status in Human Cancer and Its Clinical Significance: Does One Size Fit All? Adv Anat Pathol (2019) 26(4):270–9. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0000000000000234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mittendorf EA, Zhang H, Barrios CH, Saji S, Jung KH, Hegg R, et al. Neoadjuvant Atezolizumab in Combination With Sequential Nab-Paclitaxel and Anthracycline-Based Chemotherapy Versus Placebo and Chemotherapy in Patients With Early-Stage Triple-Negative Breast Cancer (Impassion031): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet (2020) 396(10257):1090–100. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31953-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schmid P, Cortes J, Pusztai L, McArthur H, Kümmel S, Bergh J, et al. Pembrolizumab for Early Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med (2020) 382(9):810–21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gianni L, Huang C-S, Egle D, Bermejo B, Zamagni C, Thill M, et al. Abstract GS3-04: Pathologic Complete Response (Pcr) to Neoadjuvant Treatment With or Without Atezolizumab in Triple Negative, Early High-Risk and Locally Advanced Breast Cancer. Neotripapdl1 Michelangelo Randomized Study. Cancer Res (2020) 80(4 Supplement):GS3–04. doi: 10.1158/1538-7445.SABCS19-GS3-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mills AM, Dill EA, Moskaluk CA, Dziegielewski J, Bullock TN, Dillon PM. The Relationship Between Mismatch Repair Deficiency and PD-L1 Expression in Breast Carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol (2018) 42(2):183–91. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pereira B, Chin SF, Rueda OM, Vollan HK, Provenzano E, Bardwell HA, et al. The Somatic Mutation Profiles of 2,433 Breast Cancers Refines Their Genomic and Transcriptomic Landscapes. Nat Commun (2016) 7:11479. doi: 10.1038/ncomms11479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Anurag M, Ellis MJ, Haricharan S. DNA Damage Repair Defects as a New Class of Endocrine Treatment Resistance Driver. Oncotarget (2018) 9(91):36252–3. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.26363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cheng AS, Leung SCY, Gao D, Burugu S, Anurag M, Ellis MJ, et al. Mismatch Repair Protein Loss in Breast Cancer: Clinicopathological Associations in a Large British Columbia Cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2020) 179(1):3–10. doi: 10.1007/s10549-019-05438-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lopez G, Noale M, Corti C, Gaudioso G, Sajjadi E, Venetis K, et al. PTEN Expression as a Complementary Biomarker for Mismatch Repair Testing in Breast Cancer. Int J Mol Sci (2020) 21(4):1461. doi: 10.3390/ijms21041461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lopez G, Fusco N. RE: Mismatch Repair Protein Loss in Breast Cancer: Clinicopathological Associations in a Large British Columbia Cohort. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2020) 180:265–6. doi: 10.1007/s10549-020-05530-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Helleday T, Eshtad S, Nik-Zainal S. Mechanisms Underlying Mutational Signatures in Human Cancers. Nat Rev Genet (2014) 15(9):585–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg3729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sajjadi E, Venetis K, Piciotti R, Invernizzi M, Guerini-Rocco E, Haricharan S, et al. Mismatch Repair-Deficient Hormone Receptor-Positive Breast Cancers: Biology and Pathological Characterization. Cancer Cell Int (2021) 21(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-01976-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Viale G, Trapani D, Curigliano G. Mismatch Repair Deficiency as a Predictive Biomarker for Immunotherapy Efficacy. BioMed Res Int (2017) 2017:4719194. doi: 10.1155/2017/4719194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boyiadzis MM, Kirkwood JM, Marshall JL, Pritchard CC, Azad NS, Gulley JL. Significance and Implications of FDA Approval of Pembrolizumab for Biomarker-Defined Disease. J Immunother Cancer (2018) 6(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0342-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Subbiah V, Kurzrock R. The Marriage Between Genomics and Immunotherapy: Mismatch Meets Its Match. Oncologist (2019) 24(1):1–3. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Haricharan S, Bainbridge MN, Scheet P, Brown PH. Somatic Mutation Load of Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Tumors Predicts Overall Survival: An Analysis of Genome Sequence Data. Breast Cancer Res Treat (2014) 146(1):211–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-014-2991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hou Y, Nitta H, Parwani AV, Li Z. PD-L1 and CD8 Are Associated With Deficient Mismatch Repair Status in Triple-Negative and HER2-Positive Breast Cancers. Hum Pathol (2019) 86:108–14. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Horimoto Y, Thinzar Hlaing M, Saeki H, Kitano S, Nakai K, Sasaki R, et al. Microsatellite Instability and Mismatch Repair Protein Expressions in Lymphocyte-Predominant Breast Cancer. Cancer Sci (2020) 111:2647–54. doi: 10.1111/cas.14500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Venetis K, Sajjadi E, Haricharan S, Fusco N. Mismatch Repair Testing in Breast Cancer: The Path to Tumor-Specific Immuno-Oncology Biomarkers. Trans Cancer Res (2020) 9(7):4060–4. doi: 10.21037/tcr-20-1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shia J. The Diversity of Tumours With Microsatellite Instability: Molecular Mechanisms and Impact Upon Microsatellite Instability Testing and Mismatch Repair Protein Immunohistochemistry. Histopathology (2020) 78:485–97. doi: 10.1111/his.14271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cicek MS, Lindor NM, Gallinger S, Bapat B, Hopper JL, Jenkins MA, et al. Quality Assessment and Correlation of Microsatellite Instability and Immunohistochemical Markers Among Population- and Clinic-Based Colorectal Tumors Results From the Colon Cancer Family Registry. J Mol Diagn (2011) 13(3):271–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2010.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bai H, Wang R, Cheng W, Shen Y, Li H, Xia W, et al. Evaluation of Concordance Between Deficient Mismatch Repair and Microsatellite Instability Testing and Their Association With Clinicopathological Features in Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Manag Res (2020) 12:2863–73. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S248069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zeinalian M, Hashemzadeh-Chaleshtori M, Salehi R, Emami MH. Clinical Aspects of Microsatellite Instability Testing in Colorectal Cancer. Advanced Biomed Res (2018) 7:28–. doi: 10.4103/abr.abr_185_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. De Craene B, Van de Velde J, Rondelez E, Vandenbroeck L, Peeters K, Vanhoey T, et al. Detection of Microsatellite Instability (MSI) in Colorectal Cancer Samples With a Novel Set of Highly Sensitive Markers by Means of the Idylla MSI Test Prototype. J Clin Oncol (2018) 36(15_suppl):e15639–e. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.e15639 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bonneville R, Krook MA, Chen H-Z, Smith A, Samorodnitsky E, Wing MR, et al. Detection of Microsatellite Instability Biomarkers via Next-Generation Sequencing. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton NJ) (2020) 2055:119–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9773-2_5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Middha S, Zhang L, Nafa K, Jayakumaran G, Wong D, Kim HR, et al. Reliable Pan-Cancer Microsatellite Instability Assessment by Using Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing Data. JCO Precis Oncol (2017) 2017:PO.17.00084. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Albayrak A, Garrido-Castro AC, Giannakis M, Umeton R, Manam MD, Stover EH, et al. Clinical Pan-Cancer Assessment of Mismatch Repair Deficiency Using Tumor-Only, Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing. JCO Precis Oncol (2020) 4):1084–97. doi: 10.1200/PO.20.00185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Angerilli V, Galuppini F, Pagni F, Fusco N, Malapelle U, Fassan M. The Role of the Pathologist in the Next-Generation Era of Tumor Molecular Characterization. Diagnostics (2021) 11(2):339. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics11020339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kucab JE, Zou X, Morganella S, Joel M, Nanda AS, Nagy E, et al. A Compendium of Mutational Signatures of Environmental Agents. Cell (2019) 177(4):821–36.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]