Abstract

Background and Aims

The global impact of SARS-CoV-2 on liver transplantation (LT) practices across the world is unknown. The goal of this survey was to assess the impact of the pandemic on global LT practices.

Method

A prospective web-based survey (available online from 7th September 2020 to 31st December 2020) was proposed to the active members of the EASL-ESOT/ELITA-ILTS in the Americas (including North, Central, and South America) (R1), Europe (R2), and the rest of the world (R3). The survey comprised 4 parts concerning transplant processes, therapy, living donors, and organ procurement.

Results

Of the 470 transplant centers reached, 128 answered each part of the survey, 29 centers (23%), 64 centers (50%), and 35 centers (27%) from R1, R2, and R3, respectively. When we compared the practices during the first 6 months of the pandemic in 2020 with those a year earlier in 2019, statistically significant differences were found in the number of patients added to the waiting list (WL), WL mortality, and the number of LTs performed. At the regional level, we found that in R2 the number of LTs was significantly higher in 2019 (p <0.01), while R3 had more patients listed, higher WL mortality, and more LTs performed before the pandemic. Countries severely affected by the pandemic (“hit” countries) had a lower number of WL patients (p = 0.009) and LTs (p = 0.002) during the pandemic. Interestingly, WL mortality was still higher in the “non-hit” countries in 2020 compared to 2019 (p = 0.022).

Conclusion

The first wave of the pandemic differentially impacted LT practices across the world, especially with detrimental effects on the “hit” countries. Modifications to the policies of recipient and donor selection, organ retrieval, and postoperative recipient management were adopted at a regional or national level.

Lay summary

The health emergency caused by the coronavirus pandemic has dramatically changed clinical practice during the pandemic. The first wave of the pandemic impacted liver transplantation differently across the world, with particularly detrimental effects on the countries badly hit by the virus. The resilience of the entire transplant network has enabled continued organ donation and transplantation, ultimately improving the lives of patients with end-stage liver disease.

Keywords: Sars-Cov-2, pandemic, COVID, Liver Transplantation, survey

Graphical abstract

Introduction

In late 2019, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) emerged in China as a serious threat to public health.1 Since then, SARS-CoV-2 has become a devastating pandemic that has overwhelmed healthcare systems around the world, resulting in more than 168 million infections with a death toll exceeding 3.5 million as of May 2021.2 Additionally, the collateral damage of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been extensive, disrupting the clinical management of patients with acute and chronic diseases globally.[3], [4], [5]

The early days of the pandemic had demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 affected liver transplantation (LT) at the organizational level, as well as the individual patient and provider level.6 The operation of the LT program, including evaluation and selection of potential candidates, waiting list management, donor evaluation, transplantation, and subsequent recipient and living donor follow-up, requires substantial resources and infrastructure that were compromised, especially early in the pandemic, as demonstrated by regional studies.7 In countries with primarily deceased donations, the situation was further complicated as individual LT programs depend on the donor networks to continue LT.8 Patients with cirrhosis9 and recipients of LTs10 are thought to be at a higher risk of morbidity and mortality from SARS-CoV-2. Liver donor to recipient transmission has also been reported.11 Frontline healthcare workers have been at a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection,12 causing a large proportion of the workforce to be temporarily out of service. These factors have led LT centers worldwide to adopt various strategies to mitigate the risk to their patients and care providers. These strategies involved every aspect of the LT process, including managing infected or exposed patients on the waiting list, pausing or limiting transplant and donor operations, implementing new policies regarding retrieval of the donated organs, adjusting post-transplant immunosuppression, and adopting virtual technology for patient follow-up, among other policies.13 Currently, there is insufficient data on the changes in these practices and/or risk mitigation approaches and policies. Therefore, a task force was formed in mid-2020 by the European Association for the Study of Liver disease (EASL), International Liver Transplantation Society (ILTS), and the European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association (ELITA) of the European Society of Organ Transplantation (ESOT) to investigate the global impact of the first wave of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on LT centers and their patient care practices using a multidisciplinary online survey. Herein, we report the results of the survey and their implications, which may help the LT centers to operate better if they continue to encounter the sequelae of the current pandemic and optimize these programs for future pandemics.

Materials and methods

A prospective cross-sectional web-based survey (available online from 7th September 2020 to 31st December 2020) was designed by a group of investigators dedicated to the care of patients in need of LTs from 3 international societies: EASL, ESOT-ELITA, and ILTS. The survey was created using Google Forms (Google LLC, Mountain View, CA, USA) and consisted of single-choice items and open-answer questions.

The study protocol conformed to the ethical guidelines and was approved by the institutional review board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center, USA. The survey was available on the websites of all 3 societies, and all members of the societies were invited by email to respond, ensuring not to duplicate the emails or the personnel at each center. The survey was also promoted via social media platforms (Twitter and Facebook accounts of the participating societies). Participants were given a choice to disclose their transplant center names and contact information; 97% of participants disclosed this information. Non-respondents were contacted at least twice. The survey was divided into 4 independent parts. Section 1 assessed the influence of the pandemic on LT programs across the globe, evaluating different topics such as listing, transplant volumes, mortality, and others, compared to the same period in the previous year. Section 2 evaluated the impact of special precautions, modifications, and demands required for the continuation of services during the first wave of the pandemic. Section 3 dealt with different aspects of living donations during the pandemic. Finally, Section 4 highlighted the effects of the pandemic on deceased liver donations, especially regarding strategies to recover organs (Supplementary Section 1).

Data was collected and categorized into 3 regions: the Americas (including North, Central, and South America) (R1), Europe (R2), and the rest of the world (R3).

Statistical analysis

Data was expressed as a median and interquartile range, while categorical variables were expressed as percentages. Continuous variables were compared by unpaired Student’s t test, Mann- Whitney U test. The equality of matches pairs of observations was assessed using the Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. Distribution was assessed by normality plots and the Shapiro-Wilk test. Categorical variables were compared by determining X2 values by performing Fisher’s exact test. Trends in the number of patients listed for LT, waiting list mortality, and the number of LTs performed between similar periods before and after the pandemic were expressed as a ratio (e.g., variable between 1st January and 1st July in 2019/variable between 1st January and 1st July in 2020) and changes were assessed by multivariable linear regression after adjusting for COVID-19 case-fatality rate, living donor activity and country. Analysis of subgroups was performed to assess outcomes according to the continents “hit” vs. “non-hit” countries, and volume of living donor activity. Continents were classified as Africa (Egypt, South Africa); the Americas (Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Mexico, the United States of America); Asia (China, India, Japan, Jordan, Oman, Pakistan, the Republic of the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea); and Europe (Austria, Belgium, Croatia, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Spain, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom). In order to define “hit” and “non-hit” countries a multivariate adaptive regression splines was modeled, considering 3 gradients per spline, in order to define the best cut-off explaining a change in the trend of the number of patients listed for LT, mortality on the waiting list, and the number of LTs performed pre- and post-pandemic, according to the case-fatality rate of COVID-19 across the countries, see Supplementary Section 2 Fig. S1 (data obtained from the World Health Organization, https://covid19.who.int). The best cut-off was chosen, and Bayesian credibility intervals were assessed. Centers in which more than 30% of LTs were living donor liver transplants (LDLTs) were considered as having a high volume of LDLT activity. Post hoc Bayesian credibility intervals and correction for multiple comparisons were performed by the Bonferroni test. Missing data were treated by list-wise deletion. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA 15/IC.1 (StataCorp. 2017; Stata Statistical Software: Release 15; College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Results

Transplant processes

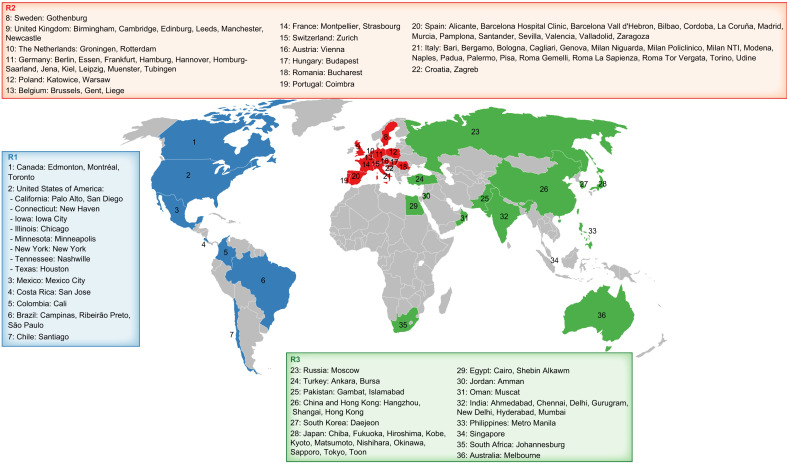

A total of 470 LT centers were reached across the world. Among these, 128 centers responded by filling in all parts of the survey. This included 29 centers (23%), 64 centers (50%), and 35 centers (27%) from R1, R2, and R3, respectively (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Section 3 Table S1).

Fig. 1.

The global distribution of centers that responded to our survey. (This figure appears in color on the web.)

Most hospitals (62.1–71.4%) across the globe had specific areas dedicated to COVID-19, and very few remained COVID-19-free hospitals. Most transplant centers withheld donor deceased LT services for up to a month (R1 = 45.5%, R2 = 50%, and R3 = 28.6%). Nevertheless, acute liver failure (ALF) remained an exemption to this hold (R1 = 52.6%, R2 = 54.8%, and R3 = 31.2%), and patients were managed in most centers on a case-by-case basis.

Globally, 30–50% of the centers performed transplants on recipients with a previous diagnosis of COVID-19 (R1: 52.4%, R2: 28.8, and R3: 29.4%). About 30% of the centers reported that fear of COVID-19 was the cause of the denial of the transplant proposal.

Comparing the overall transplant practices across the globe during the first 6 months of the pandemic with the corresponding period from 2019 revealed significant differences in the number of wait-listed candidates (32.5% vs. 60.7% of centers had more wait-listed candidates in 2020 vs. 2019, p = 0.004, respectively), waiting list mortality (52.3% vs. 26.1% of centers had higher waiting list mortality in 2020 vs. 2019, p = 0.006) and number of LTs performed (36.4% vs. 59.5% of centers performed more LTs in 2020 vs. 2019, p = 0.001) (Table 1 ). A further sub-analysis to assess the impact of the geographical heterogeneity of the pandemic on regional LT services across countries and continents showed that Asia had fewer wait-listed patients in 2020 than at a similar period in the previous year (33.3% vs. 63.3% of centers had more wait-listed candidates in 2020 vs. 2019, p = 0.040) (Table 2 ). Europe also showed a non-significant trend with fewer wait-listed patients in 2020 (59.4% and 31.3% of centers in 2019 and 2020, respectively) (Table 2). In 2020, waiting list mortality was higher in Asia (p = 0.041), while showing a non-significant trend in Europe (Table 2). Correspondingly, a higher number of LTs were performed in 2019 than in 2020 in Asia and Europe (p = 0.011 for both continents), while these trends were not observed in the Americas (Table 2). However, corrections for post hoc comparisons showed no significant difference across the continents (corrected significance of p ≤0.006). With low respondents from Africa and Australia, these continents were excluded from the analyses (Table 2, Supplementary Section 2 Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Percentage of centers with a higher number of candidates listed, higher waiting list mortality, and higher number of LTs performed between 2019 and 2020.

| Global |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | p value | |

| Centers with more candidates listed | 60.7% | 32.5% | 0.004 |

| Centers with higher waiting list mortality | 26.1% | 52.3% | 0.006 |

| Centers performing more LTs | 59.5% | 36.4% | 0.001 |

The sum of percentages does not reach 100% because of the centers with the same level of activity in 2019 and 2020: e.g., 60.7% of centers had a higher number of listed patients in 2019; 32.5% had a higher number of listed patients in 2020 and 6.8% had the same number of listed patients. Values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Table 2.

Percentage of centers with a higher number of candidates listed, higher waiting list mortality, and higher number of LTs performed between 2019 and 2020 based on geographic area (R1: Americas, R2. Europe, R3: rest of the world).

| R1 |

R2 |

R3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | p value | 2019 | 2020 | p value | 2019 | 2020 | p value | |

| Centers with more candidates listed | 60.0% | 35.0% | 0.490 | 59.4% | 31.3% | 0.072 | 63.3% | 33.3% | 0.040 |

| Centers with higher waiting list mortality | 23.5% | 47.1% | 0.301 | 27.4% | 51.6% | 0.100 | 20.7% | 58.6% | 0.041 |

| Centers performing more LTs | 52.4% | 42.9% | 0.958 | 59.4% | 35.9% | 0.011 | 63.6% | 33.3% | 0.011 |

| Corrected p value was ≤0.006 | |||||||||

The sum of percentages does not reach 100% because of the centers with the same level of activity in 2019 and 2020. Values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Out of the 33 countries, Egypt had a greater number of patients listed in 2019 than in 2020 (ß 3.386, 95% CI 0.963; 5.808, p = 0.007). India and Mexico had a similar trend (ß 2.011, 95% CI -0.871; 4.109, p = 0.060 and ß 2.163, 95% CI -0.259; 4.585, p = 0.079, respectively). The ratio of LTs performed in 2019 compared to 2020 was significantly higher in India, Oman, and the Philippines (ß 2.470, 95% CI 0.1208; 4.820, p = 0.040; ß 8.121, 95% CI 4.940; 11.303 p <0.001 and 3.288, 95% CI; 0.106; 6.469, p = 0.043, respectively) compared the other countries. These results were confirmed by Bayesian inference (Supplementary Section 3 Table S2).

“Hit” vs. “non-hit” countries

A COVID-19 case-fatality rate of 3.4% was considered the best cut-off for “hit” vs. “non-hit” countries, with a 95% of probability of falling between 0.028 and 0.051 bounds based on the main outcomes of LT activity.

“Hit” countries had a lower number of wait-listed patients (p = 0.009) and LTs (p = 0.002) (Table 3 ) during the pandemic compared to a similar period in 2019. Moreover, the “non-hit” countries had a similar number of wait-listed patients (p = 0.097) and LT numbers (p = 0.109) (Table 3) during the pandemic compared to 2019. Interestingly, waiting list mortality was higher in the “non-hit” countries than in the “hit” countries in 2020. However, only wait-listed patients and the number of LTs performed in “hit countries” were significantly diminished in the pandemic era after post hoc comparison correction (corrected p ≤0.013) (Supplementary Section 2 Fig. S3).

Table 3.

Percentage of centers with a higher number of candidates listed, higher waiting list mortality, and higher number of LTs performed between 2019 and 2020 in hit vs. non-hit countries.

| Non-hit countries |

Hit countries |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | p value | 2019 | 2020 | p value | |

| Centers with more candidates listed | 56.5% | 34.8% | 0.097 | 66.7% | 29.2% | 0.009 |

| Centers with higher waiting list mortality | 25.4% | 54.0% | 0.022 | 27.1% | 50.0% | 0.124 |

| Centers performing more LTs | 52.1% | 43.8% | 0.109 | 47.9% | 25.0% | 0.002 |

| Corrected p value was ≤0.013 | ||||||

The sum of percentages does not reach 100% because of the centers with the same level of activity in 2019 and 2020. Values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Living donor liver transplantation

Another subgroup analysis of LDLT centers categorized as low volume (≤30% LDLT activity) and high volume (>30% LDLT activity) showed that the influence of the pandemic was more obvious in high volume LDLT centers. There were significantly fewer wait-listed patients (p = 0.005) and fewer LTs performed in high volume LDLT centers (p = 0.013) (Table 4 ) after the pandemic compared to in 2019 (Table 4). The “low volume” LDLT centers were predominantly from the Americas and Europe and had a similar number of wait-listed patients, but a lower number of LTs performed in 2020 compared to 2019 (p = 0.006). However, waiting list mortality in both high and low volume LDLT centers was similar across the 2 periods (Table 4). Moreover, waiting list mortality was not associated with the COVID-19 case-fatality rate once adjusted for country and LDLT activity. Data were confirmed after post hoc comparison correction (corrected p ≤0.013) (Supplementary Section 2 Fig. S4).

Table 4.

Percentage of centers with a higher number of candidates listed, higher waiting list mortality, and higher number of LTs performed between 2019 and 2020 in areas of low LDLT activity vs. high LDLT activity.

| Low LDLT activity |

High LDLT activity |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2020 | p value | 2019 | 2020 | p value | |

| Centers with more candidates listed | 57.7% | 33.8% | 0.100 | 70.3% | 27.0% | 0.005 |

| Centers with higher waiting list mortality | 29.0% | 47.8% | 0.123 | 25.7% | 57.1% | 0.089 |

| Centers performing more LTs | 59.7% | 34.7% | 0.006 | 62.5% | 35.0% | 0.013 |

| Corrected p value was ≤0.013 | ||||||

The sum of percentages does not reach 100% because of the centers with the same level of activity in 2019 and 2020. Values in bold indicate statistical significance.

Organ donation

Most transplant teams (R1 = 83.3%, R2 = 42.6%, and R3 = 44.1%) made specific policy changes to their organ recovery protocols for safety during the pandemic. Only 12–17% of the centers transplanted organs from previously SARS-CoV-2-infected donors, mostly when the disease-to-donation interval was over a month. Four LDLT donors from R1 and R3 were diagnosed with COVID-19 in the postoperative period. Three of them had an uneventful course and were discharged; no data were available on the 4th donor.

Recipient outcomes

Between 18.2% and 36.4% of the recipients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 after LT with a mortality rate of R1 = 25%, R2 = 20%, and R3 = 8.3% across the 3 regions. Only 23% of the centers retested donors/recipients for COVID-19 at discharge.

Immunosuppression and anticoagulation

Only 8–14% of the centers routinely reduced calcineurin inhibitor doses in LT recipients following COVID-19 infection. Most centers managed immunosuppression on a case-by-case basis (52.8–75%). The regular use of anticoagulants in recipients differed significantly across the 3 regions (R1 = 45.8%, R2 = 38.2%, and R3 = 64.3%; p = 0.03).

Telemedicine

Nearly all transplant centers depended heavily on virtual technology during the pandemic, and very few centers did not use telemedicine (R1 = 0%, R2 = 12.3%, and R3 = 14.3%).

Discussion

SARS-CoV-2, an invisible microorganism, has put the whole world under pressure, with devastating health, human and economic costs.14 Yet, it is crucial to recognize that the frequency of pandemics have increased over the past 20 years and it is unlikely that SARS-CoV-2 will be the last global health crisis that we witness, as discussed by Drs. Morens and Fauci in their recent publication “Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19”..15 Therefore, the lessons learned from the current pandemic including the impact on the individual areas of medical practice could be critical knowledge for the future in the instance of a new health crisis.

Although it has been recognized that the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic had a profound impact on the healthcare system, data about the global impact of the virus on LT practices across the world are limited.

This survey showed an early cessation of activity in LT centers, generally for 4 weeks. However, an exception was made for patients referred to the centers in severe conditions (ALF, high model for end-stage liver disease [MELD], and acute-on-chronic liver failure). Before the first wave, little was known regarding the impact of an immunosuppressed state on COVID-19 and vice-versa, and most recommendations were extrapolated from previous SARS/MERS epidemics. Scientific evidence remained scarce, and strategies were based only on expert opinion. This is also reflected in results of our survey, wherein there remained a heterogeneity in the answers with regards to transplantation of infected patients, their ‘cooling off’ period, and the urgency of operation. In those more uncertain times, based on available evidence, various transplant societies across the world came up with their recommendations.[16], [17], [18], [19], [20] Interestingly, a study based on consensus-based guidance derived from individual information from 22 transplant societies highlighted a high degree of consensus.21 Fourteen of 19 societies recommended either a temporary suspension or reduction of elective transplantation to a minimum. It was recommended that the decision to perform LT should be made on a case-by-case basis, giving priority to those who were unstable or had an MELD of over 25 or 30. Furthermore, a relaxation of rules was based on the availability of intensive care unit beds and staff required for the transplantation procedure. More recently, strong evidence-based data, e.g. from the ELITA/ELTR cohort, corroborate previously suggested recommendations with regards to the urgency and safety of transplanting patients with high MELD scores.22 Furthermore, reducing transplantation activities allowed for the establishment of necessary COVID-19 wards, freeing the intensive care units for the management of COVID-19-affected critically ill patients, and allowing the mobilization of health personnel (both medical and non-medical) to COVID-19-affected areas.

Interestingly in some cases, patients on the waiting list for a transplantation withdrew their consent for transplantation because of fear of being infected, probably due to more hypochondriasis. It is likely that transplant patients, particularly those who are more vulnerable and have impaired self-awareness, may need more information about their illness, about the possible changes and fears associated with the spread of an infectious disease, their medication and treatment strategies for stress reduction, and about how to protect themselves from being infected with SARS-CoV-2.23 Based on the fears and information deficits reported by patients in a German survey,24 transplant centers are advised to intensify communication strategies and consider implementing telehealth in order to provide optimum medical care for LT recipients and patients on the waiting list. As underlined by Holmes et al.,25 feeling distressed or anxious is understandable for many going through such unprecedented times. Clearly, for those who are vulnerable, it is important to be vigilant to mitigate risks to mental health. We also need to consider longer term preventive approaches more broadly, so that we are more responsive to the chronic outcomes of the current pandemic as well as being better prepared for future public health crises.

As expected, the regions most affected by the pandemic were the ones that had fewer patients added to the LT waiting list and fewer LTs performed in the first 6 months of 2020 compared to 2019. However, the survey showed an interesting result, a higher waiting list mortality in non-hit countries compared to hit countries. This could have been due to the severe lockdown in these regions during the pandemic. This hypothesis fits with another interesting result in our survey, i.e., the areas with high living transplant activity had more patients added to the waiting list and more LTs performed in 2019 compared to 2020. Although cessation of transplant activity, especially in the setting of living donation, is prudent during a pandemic, special attention should be paid to sick patients on the waiting list. If increased waiting list mortality in non-hit countries during the pandemic was the result of severe lockdowns or the fear of seeking medical care, then a reassessment of how we manage patients with chronic liver disease during a pandemic would be warranted.[25], [26], [27]

In the survey, only a percentage of the transplant centers decided to consider previous positive candidates for transplantation. In a recent international series,22 patients with prior COVID-19 had favorable outcomes, with early survival of 96% (25/26) after receiving a LT. Median ICU and total hospital stay were 3 (IQR 3–6) and 11 (IQR 8–19) days, which concur with what is observed in more recent series.28 The ideal timing for readmission of patients to the transplant waiting list is not yet clear; however, in clinical practice, most guidelines suggest to consider patients after at least 2 weeks from the negative swab.29 , 30 However, a negative RT-PCR rhinopharyngeal swab and an additional negative swab at the time of LT should be enough to readmit the patient to the waiting list, because to date, zero cases of SARS-CoV-2 recurrence have been observed after LT. With the paucity of data, it is not known if patients recently affected by COVID-19 can be safely transplanted.

Immunosuppression in these patients may result in adverse outcomes, and the optimal disease-free interval is currently unknown.[31], [32], [33], [34], [35] For the reduction of immunosuppression to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection, most centers evaluated recipients on a case-by-case basis. The EASL guidelines confirmed these findings, suggesting that reduction should only be considered under special circumstances (e.g., medication-induced lymphopenia or bacterial/fungal superinfection in case of severe COVID-19).36 The results from the ELITA-ELTR multicenter study demonstrated that the use of tacrolimus was associated with better survival in 243 symptomatic LT recipients.37 Recent data from Spanish transplant centers showed that the baseline immunosuppression using mycophenolate was an independent predictor of severe COVID-19 and it was dose-dependent.38

We also found a discrepancy in the prophylactic use of subcutaneous anticoagulants to prevent thromboembolism. In most of the European centers and a few centers from other regions, heparin or heparin-like drugs were routinely administered in transplant patients.

Another issue raised by the survey was whether donors/recipients were tested for SARS-CoV-2 at discharge. Most transplant centers did not check for infection because, as suggested by the survey, transplant patients were hospitalized in COVID-19-free areas, where both patients and health personnel were subjected to serial swabs. Most of the transplant centers adopted the policy of repeating the swab at the time of discharge only if the patient was symptomatic or for specific reasons.

Our survey has some limitations. Given the rapid development of the pandemic that placed an extraordinary burden on healthcare providers, the overall response rate for our survey was only 27%, ranging between 23-50%; however, the authors felt that the timely report on specific practices by transplant centers in different world regions during the first wave of the pandemic was a valuable addition to the transplant literature. Particularly, as the world lives through recurrent waves of the pandemic, the information from our report may alert transplant centers to the processes of waiting list activation, management, and transplant decisions. First of all, the impact of the first wave of SARS-CoV-2 infection was different across the world, so it is difficult to compare the consequences at a global level. Another limitation of the survey is that unfortunately we do not have the absolute number of patients belonging to the centers that responded, but the percentages of responses of colleagues who report their experience. Even with a large number of responses, we cannot exclude a global underestimation of the impact of COVID-19 in the transplant setting. Finally, while analyzing the data at a global scale, we cannot exclude missing some peculiarities of the impact of the infection at a local scale. Specifically, center-based COVID-19-related epidemiologic data were not available at the time of the study. Therefore, the analyses were done based on the available country- or state-based data.”

Nevertheless, our study has strengths, including real-time data collection by the international multi-society collaborative survey. Importantly, the global nature of this study offered a unique opportunity to demonstrate intercontinental and interregional differences in LT-related outcomes and practices. Furthermore, these observations may serve as lessons to guide how LT programs handle future waves of this pandemic, other pandemics, or other hurdles of this magnitude.

In conclusion, this international survey suggests that the first wave of the pandemic impacted LT across the world differently, with particularly detrimental effects on the hit countries. However, the survey has shown the resilience of the entire transplantation network to support liver donation and transplantation during testing times.

Abbreviations

ALF, acute liver failure; LDLT, living donor liver transplantation; LT, liver transplant(ation); MELD, model for end-stage liver disease; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2.

Financial support

This manuscript received no financial support.

Authors’ contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design, the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data, FPR, MI, AS, VAK, TDM drafted the article and made critical revisions for important intellectual content. TDM performed statistical analysis. All authors approved the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the article are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest

The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Please refer to the accompanying ICMJE disclosure forms for further details.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely and deeply acknowledge all respondents for their precious participation in this time- sensitive survey (all the centers are listed in the Supplementary Section 3, table 1).

We would like to acknowledge Luca Segantini from the European Society for Organ Transplantation for the preparation of the survey, Rossana Mirabella, Joel Walicki and Ben Hainsworth from The European Association for the Study of the Liver and Jwana Ribeiro da Silva from the International Liver Transplant Society for their continuous technical support throughout the survey period.

Footnotes

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2021.09.041.

Supplementary data

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(8):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH . 2021. WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sud A., Jones M.E., Broggio J., Loveday C., Torr B., Garrett A., et al. Collateral damage: the impact on outcomes from cancer surgery of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:1065–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chu K., Reddy C.L., Makasa E., AfroSurg C. The collateral damage of the COVID-19 pandemic on surgical health care in sub-Saharan Africa. J Glob Health. 2020;10 doi: 10.7189/jogh.10.020347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moroni F., Gramegna M., Ajello S., Beneduce A., Baldetti L., Vilca L.M., et al. Collateral damage: medical care avoidance behavior among patients with myocardial infarction during the COVID-19 pandemic. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1620–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar D., Manuel O., Natori Y., Egawa H., Grossi P., Han S.H., et al. COVID-19: a global transplant perspective on successfully navigating a pandemic. Am J Transpl. 2020;20:1773–1779. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Carlis R., Vella I., Incarbone N., Centonze L., Buscemi V., Lauterio A., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on liver donation and transplantation: a review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27(10):928–938. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v27.i10.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trotter J.F. Liver transplantation around the world. Curr Opin Organ Transpl. 2017;22:123–127. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merola J., Schilsky M.L., Mulligan D.C. The impact of COVID-19 on organ donation, procurement and liver transplantation in the United States. Hepatol Commun. 2020;5(1):5–11. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iavarone M., D'Ambrosio R., Soria A., Triolo M., Pugliese N., Del Poggio P., et al. High rates of 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID-19. J Hepatol. 2020;73:1063–1071. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Belli L.S., Duvoux C., Karam V., Adam R., Cuervas-Mons V., Pasulo L., et al. COVID- a. 19 in liver transplant recipients: preliminary data from the ELITA/ELTR registry. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:724–725. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(20)30183-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heinz N., Griesemer A., Kinney J., Vittorio J., Lagana S.M., Goldner D., et al. A case of an Infant with SARS-CoV-2 hepatitis early after liver transplantation. Pediatr Transpl. 2020;24 doi: 10.1111/petr.13778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nguyen L.H., Drew D.A., Graham M.S., Joshi A.D., Guo C.G., Ma W., et al. Risk of COVID-19 among frontline healthcare workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e475–e483. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30164-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Russo F.P. COVID-19 in Padua, Italy: not just an economic and health issue. Nat Med. 2020;26(6):806. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0884-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morens D.M., Fauci A.S. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we Got to COVID-19. Cell. 2020;182(5):1077–1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tschopp J., L’Huillier A.G., Mombelli M., Mueller N.J., Khanna N., Garzoni C., et al. (STCS) STCS. First experience of SARS-CoV-2 infections in solid organ transplant recipients in the Swiss Transplant Cohort Study. Am J Transpl. 2020;20(10):2876–2882. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Surgery C . 2020. Guidance from the international society of heart and lung transplantation regarding the SARS CoV-2 pandemic; pp. 2–16.https://ishlt.org/ishlt/media/documents/SARS-CoV-2_-Guidance-for-Cardiothoracic-Transplant-and-VAD-centers.pdf [Internet] [cited 2020 Jun 5] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Transplantation CSo. https://profe du.blood.ca/sites/msi/files/20200 327_covid -19_conse nsus_guida nce_final.pdf. Accessed July 31,2021;

- 19.Service BNH. https://www.odt.nhs.uk/deceased-donation/covid-19-advice-for-clinicians/. Accessed July 31, 2021.

- 20.Liu H., He X., Wang Y., Zhou S., Zhang D., Zhu J., et al. Management of COVID-19 in patients after liver transplantation: Beijing working party for liver transplantation. 2020 Jul;14(4):432–436. doi: 10.1007/s12072-020-10043-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ritschl P.V., Nevermann N., Wiering L., Wu H.H., Moroder P., Brandl A., et al. Solid organ transplantation programs facing lack of empiric evidence in the COVID-19 pandemic: a By-proxy Society Recommendation Consensus approach. Am J Transpl. 2020;20(7):1826–1836. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Belli L.S., Duvoux C., Cortesi P.A., Facchetti R., Iacob S., Perricone G., et al. 2021 Jul 19. COVID-19 in liver transplant candidates: pretransplant and post-transplant outcomes - an ELITA/ELTR multicentre cohort study. gutjnl-2021-324879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Connor R.C., Hotopf M., Worthman C.M., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic - authors' reply. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020 Jul;7(7):e44–e45. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30247-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reuken P.A., Rauchfuss F., Albers S., Settmacher U., Trautwein C., Bruns T., et al. Between fear and courage: attitudes, beliefs, and behavior of liver transplantation recipients and waiting list candidates during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Transpl. 2020;20(11):3042–3050. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmes E.A., O'Connor R.C., Perry V.H., Tracey I., Wessely S., Arseneault L., et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–560. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30168-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Saqib M.A.N., Siddiqui S., Qasim M., et al. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on patients with chronic diseases. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(6):1621–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapper E.B., Asrani S.K. The COVID-19 pandemic will have a long-lasting impact on the quality of cirrhosis care. J Hepatol. 2020 Aug;73(2):441–445. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rana A., Witte E.D., Halazun K.J., Sood G.K., Mindikoglu A.L., Sussman N.L., et al. Liver transplant length of stay (LOS) index: a novel predictive score for hospital length of stay following liver transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2017;31(12) doi: 10.1111/ctr.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/2021–03/AASLD-COVID19 ExpertPanelConsensusStatement-March92021.pdf.

- 30.https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en.

- 31.Di Maira T., Berenguer M. COVID-19 and liver transplantation. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Sep;17(9):526–528. doi: 10.1038/s41575-020-0347-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhand A., Bodin R., Wolf D.C., Schluger A., Nabors C., Nog R., et al. Successful liver transplantation in a patient recovered from COVID-19. Transpl Infect Dis. 2021;23 doi: 10.1111/tid.13492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martini S., Patrono D., Pittaluga F., Brunetto M.R., Lupo F., Amoroso A., et al. Urgent liver transplantation soon after recovery from COVID-19 in a patient with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Hepatol Commun. 2020;5(1):144–145. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raut V., Sonavane A., Shah K., Raj C.A., Thorat A., Sawant A., et al. Successful liver transplantation immediately after recovery from COVID-19 in a highly endemic area. Transpl Int. 2021;34:376–377. doi: 10.1111/tri.13790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gambato M., Germani G., Perini B., Gringeri E., Feltracco P., Plebani M., et al. A challenging liver transplantation for decompensated alcoholic liver disease after recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Transpl Int. 2021;34:756–757. doi: 10.1111/tri.13842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boettler T., Marjot T., Newsome P.N., Mondelli M.U., Maticic M., Cordero E., et al. Impact of COVID-19 on the care of patients with liver disease: EASL-ESCMID position paper after six months of the pandemic. JHEP Rep. 2020;2:100169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Belli L.S., Fondevila C., Cortesi P.A., Conti S., Karam V., Adam R., et al. Protective role of tacrolimus, deleterious role of age and comorbidities in liver transplant recipients with covid- 19: results from the ELITA/ELTR multi-center European study. Gastroenterology. 2021 Mar;160(4):1151–1163.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Colmenero J., Rodríguez-Perálvarez M., Salcedo M., Arias-Milla A., Muñoz-Serrano A., Graus J., et al. Epidemiological pattern, incidence, and outcomes of COVID-19 in liver transplant patients. J Hepatol. 2021 Jan;74(1):148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author.