Abstract

A small series of nitro group-bearing enamides was designed, synthesized (NEA1–NEA5), and evaluated for their inhibitory profiles of monoamine oxidases (MAOs) and β-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1 (β-secretase, BACE1). Compounds NEA3 and NEA1 exhibited a more potent MAO-B inhibition (IC50 value = 0.0092 and 0.016 µM, respectively) than the standards (IC50 value = 0.11 and 0.14 µM, respectively, for lazabemide and pargyline). Moreover, NEA3 and NEA1 showed greater selectivity index (SI) values toward MAO-B over MAO-A (SI of >1652.2 and >2500.0, respectively). The inhibition and kinetics studies suggested that NEA3 and NEA1 are reversible and competitive inhibitors with Ki values of 0.013 ± 0.005 and 0.0049 ± 0.0002 µM, respectively, for MAO-B. In addition, both NEA3 and NEA1 showed efficient BACE1 inhibitions with IC50 values of 8.02 ± 0.13 and 8.21 ± 0.03 µM better than the standard quercetin value (13.40 ± 0.04 µM). The parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) method demonstrated that all the synthesized derivatives can cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) successfully. Docking analyses were performed by employing an induced-fit docking approach in the GLIDE module of Schrodinger, and the results were in agreement with their in vitro inhibitory activities. The present study resulted in the discovery of potent dual inhibitors toward MAO-B and BACE1, and these lead compounds can be fruitfully explored for the generation of newer, clinically active agents for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.

Keywords: monoamine oxidase, β-secretase, nitro group-bearing enamides, potent reversible inhibitor, dual-acting inhibitor, molecular docking

1. Introduction

The development of a new class of molecules for the complex pathology of neurodegenerative disorders, like Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD), is one of the most complicated zones in medicinal chemistry [1]. Multi-target-directed ligands (MTDLs) have led to a new paradigm that has emerged in recent times, in which the newly designed molecular scaffold is able to bind to different types of biologic targets that are interconnected with similar biochemical pathways [2,3]. The MTDLs design strategy includes the combination of two pharmacologically active molecules into a single framework, or keeping the most active functional moieties of different molecules in a single hybrid molecule [4].

The oxidative deamination of monoamine-related neurotransmitters and their regulation in the central and peripheral systems are controlled by flavin-dependent monoamine oxidases (MAOs) isoenzymes, such as MAO-A and MAO-B [5,6]. Selective inhibitions by MAO-B inhibitors are considered to be a promising neuronal pharmacotherapy for AD and PD [7]. The oxidative stress provoked by the metabolism of MAO-B leads to the cognitive destruction and aggregation of neurofibrillary tangles in PD patients [8,9]. Recently, many scaffolds, like chalcones, coumarins, chromones, pyrazolines, quinazolines, isatins, and thiazolidinones, which are derivatives of FDA approved MAO-B inhibitors, showed selective, reversible, and competitive types of MAO-B inhibition [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18].

The presence of α,β-unsaturated ketone, carboxamide, multi-conjugated ketone, and olefinic linkage contribute to the versatility of the pharmacophore features of selective MAO-B inhibitors [19,20,21,22,23,24]. Recently, our group developed a new class of enamide-based MAO-B inhibitors by combining an olefinic linkage to the amide functional group. The resulting enamide linker with nitrophenyl hydrophobic candidate showed potent and selective MAO-B inhibition. The study documented that the presence of an electron-withdrawing nitro group has better binding affinity than electron-donating groups. Compound N-(3-nitrophenyl)prop-2 enamide (AD9) was an effective competitive inhibitor of MAO-B with Ki value of 0.039 ± 0.005 µM [25]. In addition, numerous reports suggested that nitro groups are versatile electron-attracting functional groups, which are used in many of the FDA-approved drugs. This unique functional group can act as a proton acceptor, which can contribute to hydrogen-bonding interactions within the catalytic site of a variety of enzyme targets [26,27]. Prompted by this observation, we expanded our examination of structure activity relationships (SARs) of enamide-based MAO-B inhibitors by keeping nitrophenyl functionalities with other selected classes of enamide-based compounds.

The inhibition of the β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme-1 (BACE1) is one of the other attractive objectives when treating AD [28]. BACE1 inhibitors that are currently in different stages of clinical trials, such as Verubecestat, Elenbecestat, and Atabecestat, have an amide functional moiety as the crucial pharmacophore feature [29]. In this research, we focused our attention on the development of a small library of nitro-substituted enamide derivatives with dual-acting MAO-B and BACE1 inhibitors. The design and development of MTDLs has become authoritative in the selection of the starting scaffolds to develop a multifunctional molecular framework. The objective of the work is the synthesis and characterization of a selected class of nitro-bearing enamides. All the molecules were further subjected to enzyme inhibition studies against MAO-A, MAO-B, and BACE1. The topmost active compounds were exploited for their kinetics, reversibility properties, parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA), and docking analyses.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Chemistry

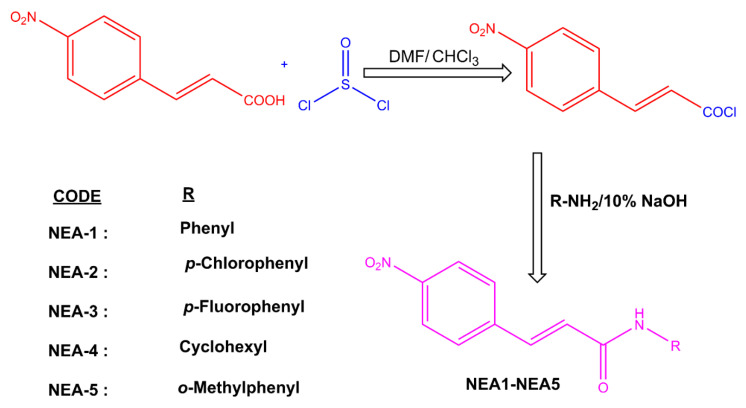

The selected class of compound was synthesized by the following approach (Scheme 1). The spectral data are provided in the Supplementary Materials. The structures of the compounds were verified with reference to previously published literature [30,31].

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of enamides.

2.2. Studies of MAOs and BACE1 Inhibitors

All of the screened compounds effectively inhibited MAO-B with residual activities of <50% at 10 μM. However, these compounds showed a greater residual activity toward MAO-A (>83.5% at 10 μM, except NEA-3) over MAO-B, indicating that these compounds possess greater inhibitory potential for MAO-B (Table 1). Compounds NEA3 and NEA1 exhibited the most potential activity toward MAO-B (IC50 value = 0.0092 and 0.016 μM, respectively) (Table 1). Unsubstituted enamide (NEA1) exerted an IC50 of 0.016 μM. Substitution of numerous functionalities exerted a varied MAO-B inhibitory profile. For instance, a strong electron-withdrawing group (-F atom) at the para position resulted in the formation of a more potent component (NEA3; IC50 = 0.0092 μM) than the parent (NEA3). Interestingly, an electron-donating substituent (NEA5 with methyl functionalities at the ortho side) also resulted in the enhancement of MAO-B inhibition. It is noteworthy that the -Cl atom on the para position in NEA2 resulted in the weakening of MAO-B inhibitory activity. This needs to be investigated further. In these derivatives, MAO-B inhibitory activities increased with the presence of para-F (NEA3) > -H (NEA1) > ortho-CH3 (NEA5) > para-Cl (NEA2) (Table 1). The selectivity for MAO-B over MAO-A was also observed in terms of the selectivity index (SI), where NEA1 and NEA3 exerted high SI values of 2500 and 1652.2, respectively (Table 1). In addition, as represented in Table 1, NEA1, NEA3, and NEA5 exerted great inhibitory potentials toward BACE1 (IC50 = 8.21, 8.02, and 17.7 μM, respectively). The IC50 values of NEA1 and NEA3 were lower than the reference quercetin (IC50 = 13.4 μM). Quercetin has been used as a reference for BACE1 inhibition, and the IC50 values ranged between 8.65 and 20.18 μM [32,33,34]. On the other hand, all of the compounds weakly inhibited acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase, with the residual activities of >76.5% at 10 μM.

Table 1.

MAOs and BACE1 inhibition profiles of nitro-bearing enamides a.

| Compounds | % Residual Activity (at 10 µM) |

IC50 (µM) | SI b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAO-A | MAO-B | BACE1 | MAO-A | MAO-B | BACE1 | ||

| NEA1 | 91.9 ± 5.9 | 3.88 ± 0.6 | 34.9 ± 0.5 | >40 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 8.21 ± 0.03 | >2500.0 |

| NEA2 | 95.0 ± 0.5 | 35.8 ± 6.2 | 88.1 ± 0.3 | >40 | 5.28 ± 0.09 | >7.58 | |

| NEA3 | 61.9 ± 0.4 | 3.04 ± 0.5 | 34.4 ± 0.2 | 15.2 ± 0.6 | 0.0092 ± 0.0003 | 8.02 ± 0.13 | >1652.2 |

| NEA4 | 85.6 ± 1.7 | 9.52 ± 3.5 | 61.2 ± 3.0 | >40 | 0.074 ± 0.020 | >540.5 | |

| NEA5 | 83.5 ± 1.3 | 8.67 ± 2.3 | 44.0 ± 0.2 | >40 | 0.038 ± 0.003 | 17.70 ± 1.70 | >1052.6 |

| Toloxatone | 1.08 ± 0.03 | - | - | ||||

| Lazabemide | - | 0.11 ± 0.02 | - | ||||

| Clorgyline | 0.007 ± 0.001 | - | - | ||||

| Pargyline | - | 0.14 ± 0.01 | - | ||||

| Quercetin | - | - | 13.40 ± 0.04 | ||||

a Results are the means ± S.E.M. of duplicate or triplicate experiments. b Selectivity index (SI) values are expressed for MAO-B as compared with MAO-A.

Recently, our group developed some trimethoxy halogenated chalcones as dual-acting MAO-B and BACE1 inhibitors that exhibited activities in the range of 0.84 to 4.17 µM and 13.6 to 19.8 µM, respectively [35]. In another study, phytochemicals from Rauwolfia serpentina roots were evaluated for their MTDL efficiencies, while indole alkaloids (reserpine and ajmalicine) were evaluated as potential agents for MAO-B and BACE1 inhibition with dose-dependent activities [36]. It is noteworthy that the replacement of chalcones with enamides resulted in the enhancement of overall MAO-B and BACE1 inhibitory activities. Interestingly, the analogues which we tested resulted in potent inhibitory activities in nanomolar ranges towards MAO-B inhibition.

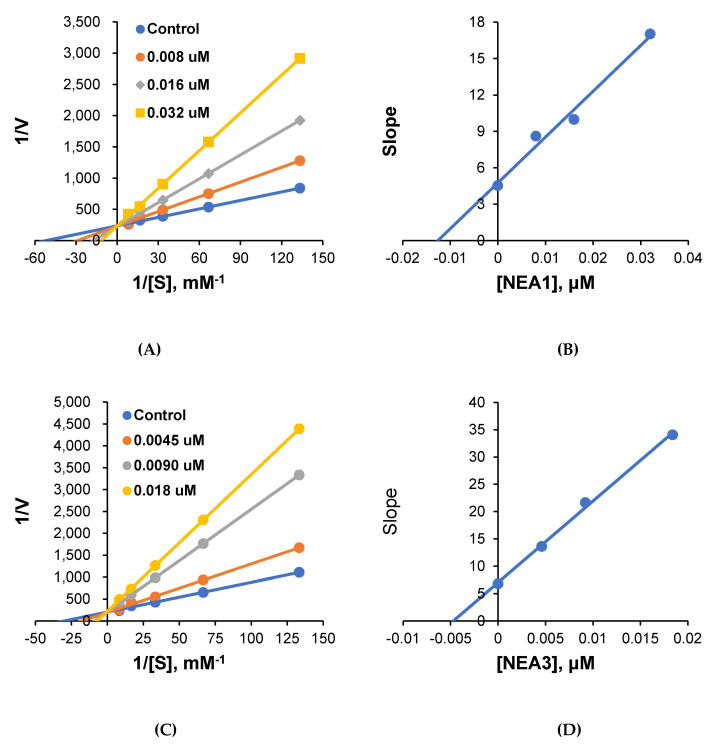

2.3. Kinetics

The most potent compounds, NEA1 and NEA3, were further subjected to enzyme-inhibition kinetics. The obtained results are represented in Figure 1. As represented in Lineweaver–Burk plots, all of the lines converged at the y-intercept (1/Vmax), suggesting the scope of the competitive mode of inhibition by these compounds. The Ki values were deduced from the secondary plot, and were found to be 0.013 ± 0.005 and 0.0049 ± 0.0002 μM for NEA1 and NEA3, respectively. These results suggest the competitive mode of inhibition by these compounds at the active site of MAO-B.

Figure 1.

Lineweaver–Burk plots for MAO-B inhibition by NEA1 and NEA3 (A,C), and their respective secondary plots (B,D) of the slopes vs. inhibitor concentrations.

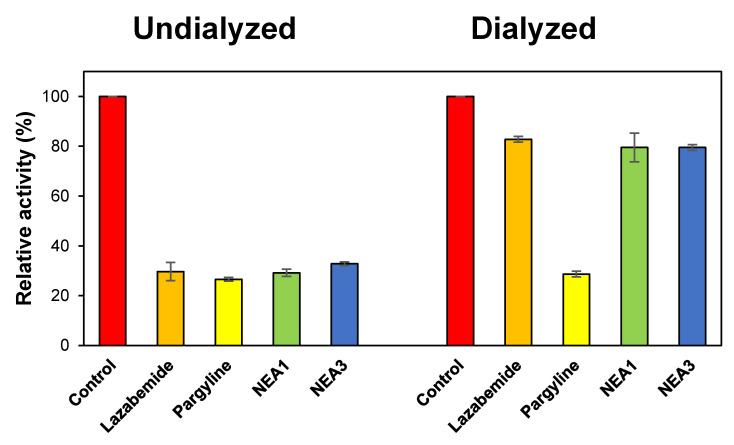

2.4. Reversibility Studies

The reversibility patterns of the potent compounds were analyzed by comparing the relative activities in undialyzed (AU) and dialyzed (AD) samples at the following concentrations: NEA1 = 0.032 μM; NEA3 = 0.020 μM; lazabemide = 0.22 μM; and pargyline = 0.28 μM. Lazabemide is a reversible inhibitor of MAO-B, while pargyline is an irreversible inhibitor of MAO-B; thus, they were selected as reference standards. In the case of NEA1, the MAO-B inhibition was recovered from 29.2% (AU) to 79.5% (AD), while for NEA3 it went from 32.8% to 79.5% (Figure 2). These recovery values were similar to the reversible reference inhibitor (lazabemide), which went from 29.7% to 82.8%, and could be distinguished to pargyline, an irreversible reference inhibitor, which went from 26.6% to 28.7%. These results indicate that NEA1 and NEA3 function as reversible MAO-B inhibitors.

Figure 2.

Recoveries of MAO-B inhibitions by NEA1 and NEA3 using dialysis experiments. Dialysis was performed for 6 h with a buffer change after 3 h with duplicate experiments.

2.5. Blood–Brain Barrier (BBB) Permeation Studies

The CNS bioavailability of the molecules was further ascertained by the PAMPA method [37]. Highly effective permeability and high CNS bioavailability were observed for all the enamides tested, with Pe ranges between 13.46 × 10−6 and 16.43 × 10−6 cm/s (Table 2).

Table 2.

BBB assay of enamide derivatives (NEA1–NEA5) using the PAMPA method.

| Compounds | Bibliography [34] Pe (×10−6 cm/s) |

Experimental Pe (×10−6 cm/s) |

Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| NEA1 | 14.44 ± 0.35 | CNS+ | |

| NEA2 | 13.46 ± 0.26 | CNS+ | |

| NEA3 | 16.43 ± 0.17 | CNS+ | |

| NEA4 | 15.54 ± 0.62 | CNS+ | |

| NEA5 | 15.53 ± 0.44 | CNS+ | |

| Progesterone | 9.3 | 9.12 ± 0.21 | CNS+ |

| Verapamil | 16.0 | 16.33 ± 0.44 | CNS+ |

| Piroxicam | 2.5 | 2.37 ± 0.33 | CNS± |

| Lomefloxacin | 1.1 | 1.31 ± 0.51 | CNS− |

| Dopamine | 0.2 | 0.26 ± 0.04 | CNS− |

CNS+ (high BBB permeation predicted: Pe (10−6 cm/s) > 4.00). CNS− (low BBB permeation predicted: Pe (10−6 cm/s) < 2.00). CNS± (BBB permeation uncertain: Pe (10−6 cm/s) from 2.00 to 4.00).

2.6. Computational Studies

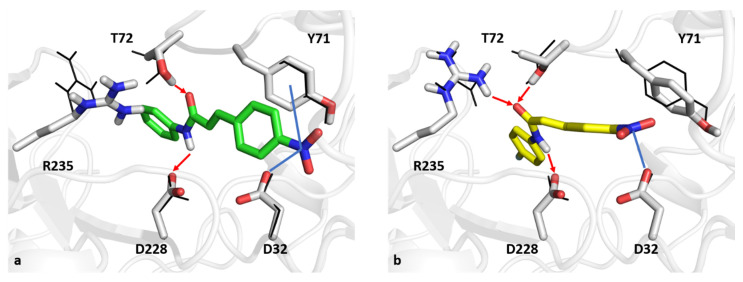

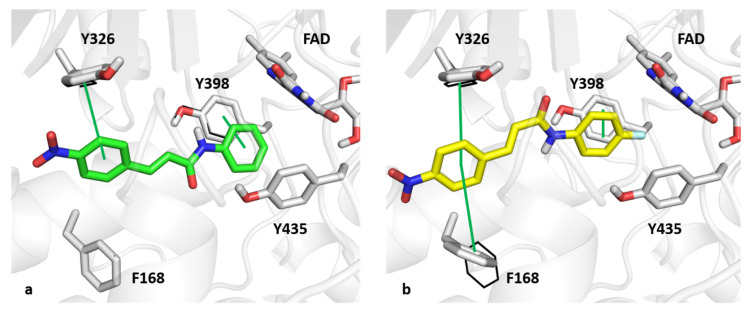

In silico analyses were performed at the molecular level to deepen the interactions between compounds NEA1 and NEA3 and enzymes BACE1 and MAO-B. Figure 3 and Figure 4 show the results of induced-fit docking.

Figure 3.

The best-docked poses of compounds NEA1 (a, green sticks) and NEA3 (b, yellow sticks) in a BACE1 binding pocket. Blue lines and red arrows indicate ion-dipole interactions and hydrogen bonds, respectively. Black wireframes report the original pose of BACE1 sidechains in the binding site.

Figure 4.

The best-docked poses of compounds NEA1 (a, green sticks) and NEA3 (b, yellow sticks) in a MAO-B binding pocket. Green lines indicate p–p contacts. Black wireframes report the original pose of MAO-B sidechains within the binding site.

As far as interactions within BACE1 are concerned, the NEA1 compound can make hydrogen bonds with T72 and the catalytic D228 with its enamide moiety. Moreover, the para-nitro substituent can make an ion-dipole interaction with the catalytic D32 and a dipole interaction with Y71 at S1. On the other hand, the enamide moiety of compound NEA3 can establish hydrogen bonds with the catalytic D228 and T72 as reported for NEA1 and, in addition, with R235. Furthermore, the para-nitro group can interact through ion-dipole interaction with catalytic D32. For the sake of completeness, docking scores for NEA1 and NEA3 were equal to 6.656 and 7.191 kcal/mol, respectively.

As for the MAO-B binding pocket, NEA1 and NEA3 assumed a similar binding mode within the MAO-B active site. The para-nitro aromatic ring of NEA1 was able to make p–p contact with the MAO-B selective residue, Y326, and the phenyl ring that resulted was placed in a network of hydrophobic interactions with FAD, Y435, and Y398, the latter also being involved in p–p contact. Regarding the binding mode of NEA3, the para-nitro aromatic ring that resulted was sandwiched between Y326 and F168. Furthermore, the para-fluorine ring was able to interact with Y398 through p–p contact, which resulted in it being trapped in the aromatic cage that Y398, Y435, and FAD formed. Docking score values obtained from simulations of NEA1 and NEA3 were found to be −9.977 and −10.453 kcal/mol, respectively.

Computational studies have shed light on the interaction between compounds NEA1 and NEA3 toward BACE1 and MAO-B. Interestingly, the induced-fit docking protocol can give a more accurate and detailed description of the binding modes of the two compounds. As far as BACE1 is concerned, the conformation of the two catalytic aspartate residues (D32 and D228) slightly changed for the optimal interaction with the two compounds. In addition, the carbonyl group of the enamides formed a hydrogen bond with the conformation T72 residue located in the FLAP region. Furthermore, R235 was particularly affected by the induced-fit docking, favoring the interaction with the enamide moiety of compound NEA3. As for MAO-B, the only residues involved in a change of its conformation state was F168, whose movement allowed the T-shape p–p contact with the para-nitro aromatic ring of compound NEA3.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Synthesis

The synthesis of the target molecules is depicted in Scheme 1. Initially, 4-nitrocinnamic acid (5 mmol, i.e., 1.0 g) was added into a 100 mL two-neck flask containing 20 mL of chloroform. Four drops of DMF were added slowly to the flask and stirred for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Thionyl chloride (10 mmol, 2 mL) was added and heated to reflux at 50–60 °C for 5 h. After completion of the reaction, the excess thionyl chloride was distilled off to obtain 4-nitrocinnamoyl chloride as a yellow solid. It was then transferred into a 250 mL flask containing a mixture of respective amines (10 mmol) and 50 mL of 10% NaOH. The reaction was stirred at RT until the completion of the reaction was confirmed by TLC. The final compounds were obtained by recrystallization from hot ethanol.

3.1.1. 3-(4-Nitrophenyl)-N-phenylacrylamide (NEA1)

Whitish-yellow powder; M.P. 210–212 °C; Rf value: 0.68 (n-hexane ethyl acetate = 2:0.5); IR (ZnSe): 3305 cm−1 (N-H stretching in amide), 1655 cm−1 (C=O stretching in amide), 1621 cm−1 (Ar-CH=CHR), 1592 cm−1 (Ar C-C stretching), 652 cm−1 (=CH out of plane in trans RHC=CHR); 1H NMR (500 MHz) DMSO-d6 δ ppm: 10.35 (s, 1H, NH), 8.30 (d, J = 5, 1H, CH), 7.91–7.81 (m, 2H), 7.01–7.91 (m, 9H, Ar H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6: 119.28, 123.58, 124.09, 126.55, 128.66, 128.78, 137.61, 138.98, 141.25, 147.57, 162.75; ESI-MS (m/z): 269.0138 [M + 1].

3.1.2. N-(4-Chlorophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylamide (NEA2)

Brownish-yellow powder; M.P. 224–226 °C; Rf value: 0.8 (n-hexane ethyl acetate = 2:0.5); IR (ZnSe): 3377 cm−1 (N-H stretching in amide), 1608 cm−1 (C=O stretching in amide), 815 cm−1 (C-Cl stretching), 1490 cm−1 (Ar C-C stretching), 692 cm−1 (=CH out of plane in trans RHC=CHR); 1H NMR (500 MHz) DMSO-d6 δ ppm: 10.49 (s, 1H, NH), 8.29–8.30 (d, J = 5 2H, CH), 6.98–7.91 (m, 8H, Ar H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6: 24.48, 25.20, 32.36, 47.72, 124.09, 126.84, 128.50, 136.13, 141.65, 147.43, 163.27; ESI-MS (m/z): 301.1145 [M + 1].

3.1.3. N-(4-Fluorophenyl)-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylamide (NEA3)

Whitish-yellow powder; M.P. 208–210 °C; Rf value: 0.61 (n-hexane ethyl acetate = 2:0.5); IR (ZnSe): 3289 cm−1 (N-H stretching in amide), 1606 cm−1 (C=O stretching in amide), 1402 cm−1 (Ar C-C stretching), 958 cm−1 (C-F stretching), 706 cm−1 (=CH out of plane in trans RHC=CHR); 1H NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6 δ ppm: 10.49 (s, 1H, NH), 8.30–8.28 (d, J = 10 2H, CH), 6.97–7.91 (m, 8H, Ar H); 13C NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6: 115.39, 120.95, 124.01, 126.25, 128.61, 135.31, 137.61, 141.12, 147.51, 157.13, 159.04, 162.57; ESI-MS (m/z): 287.0211 [M + 1].

3.1.4. N-Cyclohexyl-3-(4-nitrophenyl)acrylamide (NEA4)

Whitish-yellow powder; M.P. 166–168 °C; Rf value: 0.49 (n-hexane ethyl acetate = 2:0.5); IR (ZnSe): 3370 cm−1 (N-H stretching in amide), 2935 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1618 cm−1 (C=O stretching in amide), 725 cm−1 (=CH out of plane in trans RHC=CHR); 1H NMR (500MHz) DMSO-d6 δ ppm: 8.27–8.25 (d, J = 10, 2H, CH), 8.14 (1H, NH), 6.81–8.12 (m, 4H, Ar-H), 3.65–3.69 (m,1H, cyclohexyl), 1.18–1.82 (m, 10H, cyclohexyl); 13C NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6: 24.48, 25.20, 32.36, 47.72, 124.09, 126.84, 128.50, 136.13, 141.65, 147.43, 163.27; ESI-MS (m/z): 275.0888 [M + 1].

3.1.5. 3-(4-Nitrophenyl)-N-(O-tolyl)acrylamide (NEA5)

Whitish-yellow powder; M.P. 200–203 °C; Rf value: 0.58 (n-hexane ethyl acetate = 2:0.5); IR (ZnSe): 3270 cm−1 (N-H stretching in amide), 1615 cm−1 (C=O stretching in amide), 2918 cm−1 (C-H stretching), 1450 cm−1 (Ar C-C stretching), 720 cm−1 (=CH out of plane in trans RHC=CHR); 1H NMR (500 MHz) DMSO-d6 δ ppm: 9.61 (s,1H, NH), 8.30–8.29 (d, J = 10 2H, CH), 7.09–7.91 (m, 8H, Ar-H), 2.26 (s, 3H, -CH3); 13C NMR (125 MHz) DMSO-d6: 17.82, 124.05, 124.22, 125.10, 125.92, 126.52, 128.62, 130.28, 130.94, 136.05, 137.46, 141.33, 147.51, 162.82; ESI-MS (m/z): 283.0648 [M + 1].

3.2. Enzyme Inhibition Studies

MAO inhibitory assay was assessed in accordance with the previously standardized methods of assessing recombinant MAO-A and MAO-B by using the substrates (0.06 mM kynuramine and 0.3 mM benzylamine, respectively) [38,39,40]. Toloxatone/clorgyline and lazabemide/pargyline were used as reference standards for MAO-A and MAO-B, respectively. The Km of benzylamine for MAO-B was 0.027 mM. The BACE1 activity was measured using a commercially available assay kit (β-secretase, CS0010). An excitation wavelength of 320 nm and an emission wavelength of 405 nm were used in a fluorescence spectrometer (FS-2, Scinco, Seoul, Korea) [41]. Quercetin was used as a reference compound for BACE1. The enzymes and chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

3.3. Enzyme Inhibition and Kinetic Studies

Initially, the inhibitory activities of the synthesized compounds were identified at a concentration of 10 μM against MAO-A, MAO-B, and BACE1. Further, the IC50 of the compounds which had less than 50% of residual activity were identified for each of the respective enzymes. The obtained IC50 values thus compared were used to deduce the SI values. Five different concentrations of the substrates were used in the kinetic experiments. The enzyme kinetics and inhibition patterns were analyzed using the Lineweaver–Burk plots and their secondary plots, under three inhibitor concentrations [42].

3.4. Inhibitor-Reversibility Analysis

The reversibility of MAO-B inhibition by NEA1 and NEA3 was evaluated using a standardized dialysis method [26]. Initially, the enzyme was preincubated with the screened compounds for 30 min at ~2 × IC50 (i.e., 0.032 and 0.020 μM, respectively). Lazabemide (0.22 μM) and pargyline (0.28 μM) were used as reference standards for reversible and irreversible MAO-B inhibitors, respectively. The activities in dialyzed (AD) and undialyzed (AU) samples were compared and reversibility patterns were determined [43].

3.5. Computational Studies

Computational studies of compounds NEA1 and NEA3 were performed on X-ray structures of BACE1 (PDB ID: 3TPP) and MAO-B (PDB ID: 2V5Z), whose crystals were retrieved from the Protein Data Bank [44,45]. Geometrical optimization and energetic minimization steps were carried out on proteins by using the Protein Preparation Tools available on the Schrodinger Suite [46]. Ligands were prepared with the Ligprep Tool. The enclosing boxes were centered on cognate ligands [47]. The induced-fit protocol was used by employing GLIDE software with the OLPS3 force field, for the purpose of inspecting the binding mode of ligands as well as the conformational changes in the targets’ sidechains, thus increasing the accuracy and reliability of the results with respect to the standard docking protocols, for which such structural changes are not detectable. Sidechain refinement was carried out on residues within 6 Å of ligand poses together with Glide SP redocking of each protein–ligand complex structure within 30.0 kcal/mol of the lowest energy [48,49,50,51].

4. Conclusions

A selected class of enamides bearing nitro pharmacophore was designed, synthesized, and evaluated for its dual inhibitory activities against MAO-A, MAO-B, and BACE1. Treatment of 4-nitrocinnamic acid with thionyl chloride resulted in the formation of acid chloride, and further reactions with selected substituted primary amines afforded the analogues (NEA1 to NEA5). Among these compounds, NEA3 and NEA1 exerted more potent MAO-B activities (IC50 = 0.0092 and 0.016 μM, respectively) than the standard drugs (lazabemide and pargyline; IC50 = 0.11 and 0.14 μM, respectively). Moreover, these analogues exerted >1650-fold selectivity toward the MAO-B over MAO-A. A similar trend was observed in the case of BACE1 inhibition, wherein NEA3 and NEA1 exerted inhibitory activities with IC50 values of 8.01 and 8.21 μM, respectively. Enzyme kinetics of these analogues revealed a competitive and reversible inhibitory mode toward MAO-B. Molecular modeling studies further supported the ability of these analogues in their potential inhibitory activities. In summary, the present study identified the potent lead molecules, which will pave the way for new clinical agents for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders.

Acknowledgments

Authors acknowledge Taif University Researchers Supporting Project number (TURSP-2020/68), Taif University, Taif, Saudi Arabia (A.K.), and the Deanship of Scientific Research, Qassim University, Buraidah, Saudi Arabia (E.A.).

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online. 1H- and 13C-NMR spectral data of the compounds are available in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: A.V. (Anusree Venkidath), B.M., S.D. and H.K.; Biological activity: J.M.O.; Kinetics: J.M.O.; Docking analysis: N.G. and O.N.; Synthesis: A.V. (Anusree Venkidath), S.D., S.P.R., A.K., M.A.A. and A.V. (Ajeesh Vengamthodi); PAMPA assay: E.A.; Data curation: J.M.O., G.G. and B.M.; Writing—original draft preparation: J.M.O., N.G. and G.G.; Writing—review and editing: O.N., B.M. and H.K.; Supervision: H.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds used in this study are available from the authors.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Morphy: R., Rankovic Z. Designed multiple ligands. An emerging drug discovery paradigm. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:6523–6543. doi: 10.1021/jm058225d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Geldenhuys W.J., Youdim M.B.H., Carroll R.T., Van der Schyf C.J. The emergence of designed multiple ligands for neurodegenerative disorders. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011;94:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morphy R., Kay C., Rankovic Z. From magic bullets to designed multiple ligands. Drug Discov. Today. 2004;9:641–651. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03163-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-Soacha D.A., Scheiner M., Decker M. Multi-target-directed-ligands acting as enzyme inhibitors and receptor ligands. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019;180:690–706. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar B., Gupta V.P., Kumar V.A. Perspective on monoamine oxidase enzyme as drug target: Challenges and opportunities. Curr. Drug Targets. 2017;18:87–97. doi: 10.2174/1389450117666151209123402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathew B., Mathew G.E., Suresh J., Ucar G., Sasidharan R., Anbazhagan S., Vilapurathu J.K., Jayaprakash V. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: Perspective design for the treatment of depression and neurological disorders. Curr. Enzyme Inhib. 2016;12:115–122. doi: 10.2174/1573408012666160402001715. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tripathi A.C., Upadhyay S., Paliwal S., Saraf S.K. Privileged scaffolds as MAO inhibitors: Retrospect and prospects. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018;145:445–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manzoor S., Hoda N.A. Comprehensive review of monoamine oxidase inhibitors as anti-Alzheimer’s disease agents: A review. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;206:112787. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tripathi R.K.P., Ayyannan S.R. Monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors as potential neurotherapeutic agents: An overview and update. Med. Res. Rev. 2019;39:1603–1706. doi: 10.1002/med.21561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guglielmi P., Mathew B., Secci D., Carradori S. Chalcones: Unearthing their therapeutic possibility as monoamine oxidase B inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020;205:112650. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koyiparambath V.P., Prayaga Rajappan K., Rangarajan T.M., Al-Sehemi A.G., Pannipara M., Bhaskar V., Nair A.S., Sudevan S.T., Kumar S., Mathew B. Deciphering the detailed structure-activity relationship of coumarins as Monoamine oxidase enzyme inhibitors-An updated review. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2021 doi: 10.1111/cbdd.13919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patil P.O., Bari S.B., Firke S.D., Deshmukh P.K., Donda S.T., Patil D.A. A comprehensive review on synthesis and designing aspects of coumarin derivatives as monoamine oxidase inhibitors for depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:2434–2450. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mathew B., Mathew G.E., Petzer J.P., Petzer A. Structural exploration of synthetic chromones as selective MAO-B inhibitors: A Mini Review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2017;20:522–532. doi: 10.2174/1386207320666170227155517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Secci D., Carradori S., Bolasco A., Bizzarri B., D’Ascenzio M., Maccioni E. Discovery and optimization of pyrazoline derivatives as promising monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2012;12:2240–2257. doi: 10.2174/156802612805220057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehuman N.A., Al-Sehemi A.G., Parambi D.G.T., Rangarajan T.M., Nicolotti O., Kim H., Mathew B. Current progress in quinazoline derivatives as acetylcholinesterase and monoamine oxidase inhibitors. ChemistrySelect. 2021;6:7162. doi: 10.1002/slct.202101077. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Helguera A.M., Perez-Machado G., Cordeiro M.N., Borges F. Discovery of MAO-B inhibitors—Present status and future directions part I: Oxygen heterocycles and analogs. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2012;12:907–919. doi: 10.2174/138955712802762301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carradori S., Silvestri R. New frontiers in selective human MAO-B inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:6717–6732. doi: 10.1021/jm501690r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew B. Privileged pharmacophore of FDA approved drugs in combination with chalcone framework: A new hope for Alzheimer’s treatment. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2020;23:842–846. doi: 10.2174/1386207323999200728122627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mellado M., González C., Mella J., Aguilar L.F., Viña D., Uriarte E., Cuellar M., Matos M.J. Combined 3D-QSAR and docking analysis for the design and synthesis of chalcones as potent and selective monoamine oxidase B inhibitors. Bioorg. Chem. 2021;108:104689. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.104689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodríguez-Enríquez F., Viña D., Uriarte E., Laguna R., Matos M.J. 7-Amidocoumarins as multitarget agents against neurodegenerative diseases: Substitution pattern modulation. Chem. Med. Chem. 2021;16:179–186. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sellitepe H.E., Oh J.M., Doğan İ.S., Yildirim S., Aksel A.B., Jeong G.S., Khames A., Abdelgawad M.A., Gambacorta N., Nicolotti O., et al. Synthesis of N′-(4-/3-/2-/Non-substituted benzylidene)-4-[(4-methylphenyl)sulfonyloxy] benzohydrazides and evaluation of their inhibitory activities against monoamine oxidases and β-secretase. Appl. Sci. 2021;11:5830. doi: 10.3390/app11135830. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Legoabe L., Kruger J., Petzer A., Bergh J.J., Petzer J.P. Monoamine oxidase inhibition by selected anilide derivatives. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2011;46:5162–5174. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maliyakkal N., Eom B.H., Heo J.H., Abdullah Almoyad M.A., Parambi D.G.T., Gambacorta N., Nicolotti O., Beeran A.A., Kim H., Mathew B. A new potent and selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibitor with extended conjugation in a chalcone Framework: 1-[4-(Morpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-5-phenylpenta-2,4-dien-1-one. Chem. Med. Chem. 2020;15:1629–1633. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carradori S., Secci D., Petzer J.P. MAO inhibitors and their wider applications: A patent review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018;28:211–226. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2018.1427735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kavully F.S., Oh J.M., Dev S., Kaipakasseri S., Palakkathondi A., Vengamthodi A., Azeez R.F., Tondo A.R., Nicolotti O., Kim H., et al. Design of enamides as new selective monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2020;72:916–926. doi: 10.1111/jphp.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Olender D., Żwawiak J., Zaprutko L. Multidirectional efficacy of biologically active nitro compounds included in medicines. Pharmaceuticals. 2018;11:54. doi: 10.3390/ph11020054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nepali K., Lee H.Y., Liou J.P. Nitro-group-containing drugs. J. Med. Chem. 2019;62:2851–2893. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh A.K., Osswald H.L. BACE1 (β-secretase) inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014;43:6765–6813. doi: 10.1039/C3CS60460H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moussa-Pacha N.M., Abdin S.M., Omar H.A., Alniss H., Al-Tel T.H. BACE1 inhibitors: Current status and future directions in treating Alzheimer’s disease. Med. Res. Rev. 2020;40:339–384. doi: 10.1002/med.21622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pardin C., Keillor J.W., Lubell W.D. Cinnamoyl Inhibitors of Transglutaminase. 9,162,991. U.S. Patent. 2015 November 20;

- 31.Schultz H.W., Wiese G.A. The synthesis of some derivatives of cinnamic acid and their antifungal action. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 1959;48:750–752. doi: 10.1002/jps.3030481215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park J.H., Whang W.K. Bioassay-guided isolation of anti-Alzheimer active components from the aerial parts of Hedyotis diffusa and simultaneous analysis for marker compounds. Molecules. 2020;25:5867. doi: 10.3390/molecules25245867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Youn K., Yoon J.H., Lee N., Lim G., Lee J., Sang S., Ho C.T., Jun M. Nutrients. Discovery of sulforaphane as a potent BACE1 inhibitor based on kinetics and computational studies. Nutrients. 2020;12:3026. doi: 10.3390/nu12103026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagle A., Seong S.H., Zhao B.T., Woo M.H., Jung H.A., Choi J.S. Comparative study of selective in vitro and in silico BACE1 inhibitory potential of glycyrrhizin together with its metabolites, 18alpha- and 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid, isolated from Hizikia fusiformis. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2018;41:409–418. doi: 10.1007/s12272-018-1018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vishal P.K., Oh J.M., Khames A., Abdelgawad M.A., Nair A.S., Nath L.R., Gambacorta N., Ciriaco F., Nicolotti O., Kim H., et al. Trimethoxylated halogenated chalcones as dual inhibitors of MAO-B and BACE1 for the treatment of neurodegenerative disorders. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13:850. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13060850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kashyap P., Kalaiselvan V., Kumar R., Kumar S. Ajmalicine and reserpine: Indole alkaloids as multi-target directed ligands towards factors implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules. 2020;25:1609. doi: 10.3390/molecules25071609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Di L., Kerns E.H., Fan K., McConnell O.J., Carter G.T. High throughput artificial membrane permeability assay for blood-brain barrier. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2003;38:223–232. doi: 10.1016/S0223-5234(03)00012-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mathew B., Baek S.C., Grace Thomas Parambi D., Lee J.P., Joy M., Annie Rilda P.R., Randev R.V., Nithyamol P., Vijayan V., Inasu S.T., et al. Selected aryl thiosemicarbazones as a new class of multi-targeted monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Med. Chem. Comm. 2018;9:1871–1881. doi: 10.1039/C8MD00399H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee J.P., Kang M.G., Lee J.Y., Oh J.M., Baek S.C., Leem H.H., Park D., Cho M.L., Kim H. Potent inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by sargachromanol I from Sargassum siliquastrum and by selected natural compounds. Bioorg. Chem. 2019;89:103043. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.103043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Heo J.H., Eom B.H., Ryu H.W., Kang M.G., Park J.E., Kim D.Y., Kim J.H., Park D., Oh S.R., Kim H. Acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of khellactone coumarin derivatives isolated from Peucedanum japonicum Thurnberg. Sci Rep. 2020;10:21695. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-78782-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jeong G.S., Kang M.G., Han S.A., Noh J.I., Park J.E., Nam S.J., Park D., Yee S.T., Kim H. Selective inhibition of human monoamine oxidase B by 5-hydroxy-2-methyl-chroman-4-one isolated from an endogenous lichen fungus Daldinia fissa. J. Fungi. 2021;7:84. doi: 10.3390/jof7020084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mathew B., Oh J.M., Baty R.S., Batiha G.E., Parambi D.G.T., Gambacorta N., Nicolotti O., Kim H. Piperazine-substituted chalcones: A new class of MAO-B, AChE, and BACE1 inhibitors for the treatment of neurological disorders. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021;28:38855–38866. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13320-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nair A.S., Oh J.-M., Koyiparambath V.P., Kumar S., Sudevan S.T., Soremekun O., Soliman M.E., Khames A., Abdelgawad M.A., Pappachen L.K., et al. Development of halogenated pyrazolines as selective monoamine oxidase-B Inhibitors: Deciphering via molecular dynamics approach. Molecules. 2021;26:3264. doi: 10.3390/molecules26113264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Y., Li M., Greenblatt H., Chen W., Paz A., Dym O., Peleg Y., Chen T., Shen X., He J., et al. Flexibility of the flap in the active site of BACE1 as revealed by crystal structures and molecular dynamics simulations. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:13–25. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911047251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Binda C., Wang J., Pisani L., Caccia C., Carotti A., Salvati P., Edmondson D.E., Mattevi A. Structures of human monoamine oxidase B complexes with selective noncovalent inhibitors: Safinamide and coumarin analogs. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:5848–5852. doi: 10.1021/jm070677y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schrödinger Release 2020-4: Protein Preparation Wizard. Prime, Schrödinger, LLC.; New York, NY, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sastry G.M., Adzhigirey M., Day T., Annabhimoju R., Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013;27:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schrödinger Release 2020-4: LigPrep. Schrödinger, LLC.; New York, NY, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sherman W., Day T., Jacobson M.P., Friesner R.A., Farid R. Novel procedure for modeling ligand/receptor induced fit effects. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:534–553. doi: 10.1021/jm050540c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friesner R.A., Banks J.L., Murphy R.B., Halgren T.A., Klicic J.J., Mainz D.T., Repasky M.P., Knoll E.H., Shelley M., Perry J.K., et al. Glide: A new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1739–1749. doi: 10.1021/jm0306430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Harder E., Damm W., Maple J., Wu C., Reboul M., Xiang J.Y., Wang L., Lupyan D., Dahlgren M.K., Knight J.L., et al. OPLS3: A force field providing broad coverage of drug-like small molecules and proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:281–296. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.