Abstract

Western blotting (WB; immunoblotting) is a widely used tool for the serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis (LB), but so far, no generally accepted criteria for performance and interpretation have been established in Europe. The current study was preceeded by a detailed analysis of WB with whole-cell lysates of three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (U. Hauser, G. Lehnert, R. Lobentanzer, and B. Wilske, J. Clin. Microbiol. 35:1433–1444, 1997). In that study, interpretation criteria for a positive WB result were developed with the data for 330 serum samples (from patients with LB in different stages [n = 189] and from a control group [n = 141]) originating mostly from southern Germany. In the present work, the interpretation criteria for strains PKo (Borrelia afzelii) and PBi (Borrelia garinii) developed in the previous study were reevaluated with 224 serum samples (from patients with LB in different stages [n = 97] and from a control group [n = 127]) originating from throughout Europe that were provided by the European Union Concerted Action on Lyme Borreliosis (EUCALB). De novo criteria were developed on the basis of the reactivities of the EUCALB sera and were evaluated with the data for the samples from southern Germany. Comparison of all results led to the following recommendations: For WB for immunoglobulin G (IgG), at least two bands among p83/100, p58, p43, p39, p30, OspC, p21, p17, and p14 for PKo and at least one band among p83/100, p39, p30, OspC, p21, and p17b for PBi; for WB for IgM, at least one band among p39, OspC, and p17 or a strong p41 band for PKo and at least one band among p39 and OspC or a strong p41 band for PBi. WB with PKo was the most sensitive, and this strain is recommended for use in WB for the serodiagnosis of LB throughout Europe.

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is a global tick-borne disease caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. The disorder develops in stages and has different manifestations that mainly involve the skin, nervous system, and joints. The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based on the recognition of typical clinical signs and is assisted by laboratory tests, especially if the clinical picture is not clear (26). Routine testing comprises mostly serological methods including screening tests like the enzyme immunoassay (EIA) and confirmation tests such as Western blotting (WB; immunoblotting). However, there has been little standardization of serological assays for LB so far, resulting in tests with various levels of sensitivity and specificity. In Europe, three species of B. burgdorferi that are pathogenic for humans (3) and at least eight outer surface protein A (OspA) serotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (28, 30) are known. This heterogeneity further complicates the comparability and standardization of assay systems.

In a study involving 330 serum samples from patients with clinically defined LB and a control group collected primarily from southern Germany, we have previously developed interpretation criteria for WB of different species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (15). That study included identification of a series of key proteins with monoclonal antibodies and densitometric determination of the molecular masses of all visually distinguishable bands (more than 40 bands per strain) separately for each of the three strains used.

A principal aim of the current investigation was to evaluate the performance of our published WB criteria when applied to a panel of sera collected from throughout Europe by the European Union Concerted Action on Lyme Borreliosis (EUCALB). In addition, we developed de novo criteria for WB on the basis of the data obtained with the EUCALB sera and evaluated these using the serum samples from patients in south Germany. Both the results obtained with these two panels of sera and the interpretation criteria for WB developed in the present and in the previous study were compared.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sera provided by EUCALB.

The 224 serum samples from EUCALB included in this study are summarized in Table 1. Sera were classified into four study groups: group A (n = 51), serum samples from patients with onset of symptoms of LB less than or equal to 4 months prior to collection of samples; group B (n = 46), serum samples from patients with onset of symptoms of LB more than 4 months prior to collection of samples; group C (n = 37), potentially cross-reactive serum samples from patients with diseases other than LB; and group D (n = 90), serum samples from healthy blood donors. Only sera from patients matching the case definitions for LB published by EUCALB (26) were included in groups A and B.

TABLE 1.

Serum samples collected by EUCALB and included in this study

| Study group | No. of samples | Clinical symptom(s) | Country |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 10 | EM | Austria |

| 3 | EM | Germany | |

| 14 | EM | Hungary | |

| 5 | EM | Italy | |

| 1 | EM | Russia | |

| 4 | EM | Sweden | |

| 2 | EM | Switzerland | |

| 1 | EM, arthritis | Hungary | |

| 1 | EM, headache | Hungary | |

| 1 | EM, lymphocytoma | Hungary | |

| 3 | EM, arthralgias | Hungary | |

| 1 | EM, neuroborreliosis | Germany | |

| 3 | EM, neuroborreliosis | Hungary | |

| 1 | Neuroborreliosis | Germany | |

| 1 | Neuroborreliosis | Russia | |

| Group B | 2 | EM | United Kingdom |

| 1 | EM, flu-like symptoms | United Kingdom | |

| 3 | EM, arthritis | Hungary | |

| 1 | Lymphocytoma | United Kingdom | |

| 1 | Neuroborreliosis | Hungary | |

| 2 | Neuroborreliosis | Italy | |

| 1 | Neuroborreliosis | Sweden | |

| 2 | Neuroborreliosis | United Kingdom | |

| 1 | Neuroborreliosis, arthralgias | Hungary | |

| 2 | Arthritis | Austria | |

| 2 | Arthritis | Germany | |

| 4 | Arthritis | Hungary | |

| 3 | Arthritis | Italy | |

| 1 | Arthritis | Switzerland | |

| 1 | ACA, arthritis | Hungary | |

| 13 | ACA | Austria | |

| 3 | ACA | Germany | |

| 1 | ACA | Hungary | |

| 2 | ACA | Sweden | |

| Group C | 2 | Arthralgias | Hungary |

| 1 | Asthma bronchiale | Hungary | |

| 1 | Raynaud syndrome | Hungary | |

| 3 | Positive for rheumatoid factor | Germany | |

| 2 | Acute Epstein-Barr virus infection | Italy | |

| 1 | Infection with Chlamydia trachomatis | Germany | |

| 1 | Infection with Rickettsia conori | Portugal | |

| 5 | Leptospirosis | Portugal | |

| 1 | Leptospirosis | United Kingdom | |

| 1 | Q fever | Germany | |

| 2 | Syphilis | Germany | |

| 8 | Syphilis | Italy | |

| 1 | Neurosyphilis | Portugal | |

| 1 | Syphilis | Russia | |

| 5 | Syphilis | Sweden | |

| 1 | Tick-borne encephalitis | Switzerland | |

| 1 | Yersiniosis | Germany | |

| Group D | 5 | Blood donors | Germany |

| 1 | Blood donor | Hungary | |

| 5 | Blood donors | Italy | |

| 1 | Blood donor | Russia | |

| 4 | Blood donors | Sweden | |

| 2 | Blood donors | Switzerland | |

| 72 | Blood donors | United Kingdom |

Sera from southern German patients and blood donors included in previous study.

Sera from the following study groups comprising patients with LB (n = 189) and controls (n = 141) were investigated.

Sixty-six serum samples were obtained from unselected, untreated patients with erythema migrans (EM). A neuroborreliosis group (n = 83) included 39 patients from whose cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) B. burgdorferi sensu lato was isolated and 44 other patients with typical signs of acute neuroborreliosis, CSF pleocytosis, and specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) CSF/serum indices of ≥2.0 (27). A group of patients with late LB (n = 40) comprised 30 patients with acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) and 10 patients with Lyme arthritis. Possible differential diagnoses were excluded. All LB patients matched the EUCALB case definitions (26). Sera from 120 healthy blood donors, 11 patients with syphilis in stage II or III, and 10 patients with rheumatoid factor concentrations of ≥45 IU/ml served as a control group. The healthy blood donors had no history of frequent tick bites, erythemas, neurological symptoms, or joint disorders.

For the current work, a data bank of all visually distinguishable bands reactive by WB that was created during the previous study was reused. No additional laboratory investigations were performed with these sera for the present study.

Methods.

All methods have previously been described in detail (15, 16), and only brief descriptions will be given here.

Preparation of antigens.

Borrelial strains PKo (Borrelia afzelii OspA serotype 2) and PBi (Borrelia garinii OspA serotype 4) (30) were used for antigen preparation. Only passages of strains abundantly expressing OspA (4) and OspC (11, 31) were taken for this study.

WB.

Cell lysate was electrophoresed (19) with 12.5% polyacrylamide gels of 17 cm in length. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose by semidry blotting (18). After blocking of nonspecific binding sites, membranes were incubated in sera diluted 1:200 for WB for IgG and 1:100 for WB for IgM, washed, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG and IgM antibodies, respectively (Dakopatts, Copenhagen, Denmark). Color was developed by adding diaminobenzidine and H2O2.

Analysis of Western blots and evaluation of various interpretation criteria.

The blots were assessed blindly and, to minimize any variation in interpretation, were always assessed by the same individual. Only bands that had been shown to be of diagnostic value or that could be mistaken for certain diagnostically important bands (15) were documented for this study. In addition to the bands that were included in the proposed interpretation criteria (15) for WB for both IgG and IgM with the two strains, p60 (homolog of the Escherichia coli heat shock protein GroEL) and OspA were also read for both strains to document the discrimination from p58 and p30, respectively. The bands with apparent molecular masses of 49.7 kDa (referred to as p50) for strain PKo and 54.1 and 47.8 kDa (referred to as p54 and p48, respectively) for strain PBi were included since they had shown considerable discriminatory ability when they were evaluated as individual bands in the previous study (15). p35 of PKo was included because it was reported to be a sensitive band by investigators in the United States (10). Band intensities were determined semiquantitatively by visual comparison with band intensities for defined control sera (very faint [interpreted as negative], weak [interpreted as positive], strong, and very strong). Data were imported into a data bank for further analyses. Criteria consisting of combinations of reactive bands were evaluated systematically as previously described in detail (16). Putative criteria were sorted according to the resulting overall sensitivities and specificities. From all band combinations resulting in the same specificity, only those with the highest sensitivities were extracted for presentation in Table 3 (see Results).

TABLE 3.

Evaluation of various interpretation criteria for positive WB resultsa

| Immunoglobulin class | Strain | No. of bands requiredb | Bands taken into considerationc

|

Sera from EUCALB

|

Sera from previous study

|

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p83/100 | p60 | p58 | p43 | p41 | Strong p41d | p39 | p35 | p30 | OspC | p21 | p17 | p17b | p14 | Sensitivity (%)e | Specificity (%)f | Sensitivity (%)g | Specificity (%)h | |||

| IgG | PKo | ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 73 | 98 | 54 | 98 | |||||

| ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 73 | 97 | 56 | 98 | |||||||

| ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 74 | 97 | 57 | 97 | ||||||

| ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 76 | 95 | 56 | 96 | ||||||

| PBi | ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 58 | 99 | 39 | 100 | ||||||||

| ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 58 | 99 | 42 | 99 | ||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | + | + | 60 | 97 | 56 | 97 | |||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | 64 | 97 | 59 | 95 | ||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | 64 | 96 | 59 | 94 | |||||||||

| IgM | PKo | ≥2 | + | + | + | 29 | 100 | 14 | 100 | |||||||||||

| ≥2 | + | + | + | + | + | 31 | 98 | 20 | 99 | |||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | 45 | 98 | 36 | 99 | ||||||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | 47 | 97 | 38 | 99 | |||||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | + | 47 | 96 | 42 | 99 | ||||||||||||

| PBi | ≥2 | + | + | + | 27 | 100 | 22 | 100 | ||||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | 53 | 96 | 38 | 98 | |||||||||||||||

| ≥1 | + | + | + | 53 | 94 | 40 | 98 | |||||||||||||

Results of the best combinations for the respective serum panels are boxed.

Criteria requiring more than two bands were evaluated as well but were not beneficial in terms of discriminatory ability.

Consideration of bands not mentioned in this table but indicated in Fig. 1 was not beneficial.

Band intensity equal to or greater than the band intensity of a strongly reactive control serum sample.

For WB for IgG, sensitivities were determined from the reactivities of the serum samples from both groups A and B (n = 97); for WB for IgM, only group A sera were considered (n = 51).

Specificities were determined from the reactivities of the serum samples from both groups C and D (n = 127).

For WB for IgG, sensitivities were determined from the reactivities of the serum samples from all LB patients (n = 189); for WB for IgM only sera from patients with early stages (EM or neuroborreliosis) were considered (n = 149).

Specificities were determined from the reactivities of the serum samples from the total control group (n = 141).

Statistics.

Whenever appropriate, results were analyzed by McNemar’s χ2 test (paired proportions) or Fisher’s exact test (independent proportions). All statistical tests were performed two-sided.

RESULTS

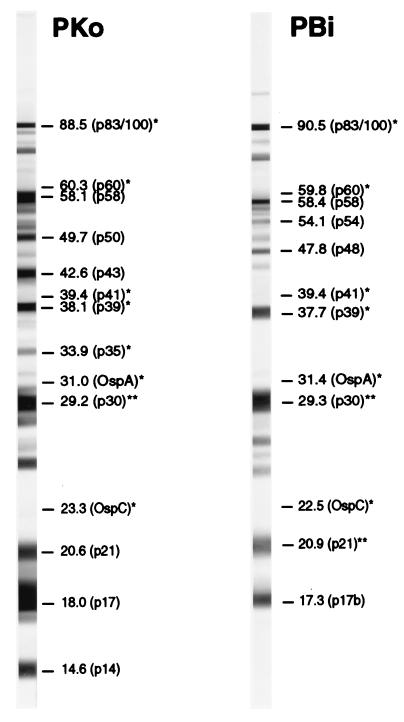

Figure 1 shows representative WB strips of the two strains incubated with serum from a patient with arthritis. All bands read and documented for the present study are indicated.

FIG. 1.

Representative WB strips of the indicated borrelial strains incubated in our broadly reactive (IgG) reference serum sample (obtained from a patient with arthritis). All bands referred to in this study are indicated by apparent molecular masses (in kilodaltons) and familiar designations (in parentheses). Certain bands were not recognized by this serum sample. ∗, molecular characterized antigens; ∗∗, antigens identified with monoclonal antibodies. For details of band identification, see reference 15.

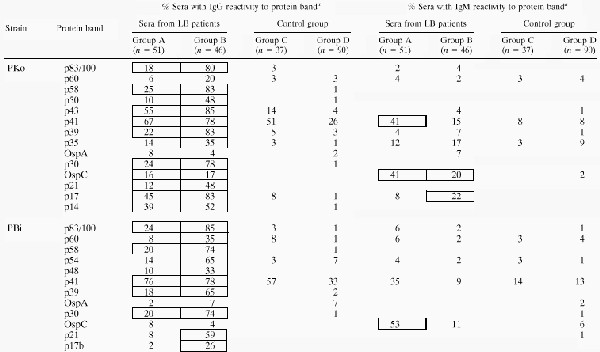

Table 2 summarizes the frequency of recognition of the bands indicated in Fig. 1 by the sera in the different EUCALB study groups. The frequencies of band recognition for each study group with LB (group A and group B separately) in comparison to those for the control group (groups C and D) were analyzed statistically. Bands showing highly significant differences between patients and controls are boxed (P < 0.001). p41 of both strains was the band most frequently recognized by WB for IgG by the group A samples but was also recognized by many control group sera. For group A, recognition of none of the other bands of PBi reached sensitivities of 25% or more by WB for IgG, whereas the unique proteins of PKo, p43, p17, and p14, were recognized considerably more frequently. From Table 1 it is evident that group A mostly comprised samples from patients with EM. p43, p58, p39, p17, and p83/100 of PKo were recognized by at least 80% of the group B sera by WB for IgG. Differences in IgM reactivities between group A and the control group were highly significant (P < 0.001) only for p41 of PKo and OspC of both strains. In group B, highly significant differences in IgM reactivity could be shown only for OspC and p17 of PKo.

TABLE 2.

Frequency of recognition of proteins by sera from EUCALB panel

|

Frequencies of band recognition of sera from patients with LB versus that for the total control group (n = 127) were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test. If P was <0.001, the frequencies are boxed. Values of zero are not shown to improve clarity.

Table 3 shows the results of an evaluation of various interpretation criteria for positive WB results. Separate calculations of sensitivities and specificities on the basis of reactivities of the sera provided by EUCALB as well as the sera included in our previous study were performed, and the results were compared. The results for the interpretation criteria (band combinations) that we considered most favorable for the respective serum panels are boxed. For WB for IgG with strain PKo, all interpretation rules resulting in optimal discriminatory abilities encompassed at least two reactive bands among p83/100, p58, p43, p39, p30, OspC, p21, and p14 plus one or two additional bands. In the previous study, p17 was included in this combination; however, for the EUCALB serum panel, omission of p17 and inclusion of p60 resulted in slightly superior results. Four samples (3%) in the EUCALB control group had shown IgG reactivity to p17 as well. For WB for IgG with strain PBi, the best criterion found in the preceding study was at least one reactive band among p83/100, p39, OspC, p21, and p17b. According to the results obtained with the EUCALB sera, inclusion of p30 in this combination would be favorable. However, three samples (2%) from the control group in the previous study with sera from patients in southern Germany were also reactive to p30 of PBi. If at least two reactive bands were required for a positive WB result, all of the band combinations resulting in optimal discriminatory abilities showed specificities of at least 99%, but this strict criterion resulted in a significant loss of sensitivity, primarily if the sera from patients in southern Germany were considered (56 versus 42%; P < 0.01). Of this panel, 11 (13%) and 6 (7%) serum samples from patients with neuroborreliosis as well as 5 serum samples (8%) and 1 (2%) serum sample from patients with EM showed isolated reactivities to OspC and to p39, respectively.

For WB for IgM with either of the two strains, any definition of criteria requiring at least two reactive bands resulted in a significant loss of sensitivity (southern German panel, P < 0.01; EUCALB panel, P < 0.05). The criteria recommended according to the results of the study with southern German samples were as follows: at least one band among p39, OspC, or p17 or a strong p41 band for PKo and at least one band among p39 or OspC or a strong p41 band for PBi (15). For both strains, inclusion of p39 did not improve sensitivity with the EUCALB panel. For WB with PBi, for the EUCALB study samples, consideration of reactivity with OspC only was as sensitive as the assessment of the combination with the other proteins mentioned above. However, two and nine samples from southern German patients with early LB with positive results by WB for IgM with PBi and PKo, respectively, were detected only if strong p41 bands or p39 bands were considered a positive result. One and seven of these serum samples, respectively, were also negative by WB for IgG with the respective strains. In view of these data, we kept our interpretation criteria as recommended previously.

Table 4 summarizes the sensitivities of WB with the two strains for various clinical manifestations determined with the EUCALB serum panel. The interpretation criteria proposed previously were used for WB for IgG and IgM with strain PKo and for WB for IgM with strain PBi. For WB for IgG with PBi, p30 was included in the band combination recommended in the preceding paper (15). Given these interpretation rules, WB for IgG with PKo was significantly more sensitive for the detection of sera from patients with EM than WB for IgG with PBi (55 versus 38%; P < 0.05). There was no difference in sensitivity for the sera originating from patients with neuroborreliosis, arthritis, or ACA. For IgM detection the two strains performed approximately equally. PKo was slightly more sensitive for sera from patients with late manifestations.

TABLE 4.

Sensitivities of WB with different strains for various clinical manifestationsa

| Immunoglobulin class | Strain | No. of bands required | % Sensitivity with serum samples from patients with:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EM (n = 47) | Neuroborreliosis (n = 10) | Arthritis (n = 12) | ACA (n = 19) | |||

| IgG | PKo | ≥2 of p83/100, p58, p43, p39, p30, OspC, p21, p17, and p14 | 55 | 80 | 100 | 100 |

| PBi | ≥1 of p83/100, p39, p30, OspC, p21, and p17b | 36 | 80 | 100 | 100 | |

| IgM | PKo | ≥1 of strong p41, p39, OspC, and p17 | 49 | 30 | 33 | 37 |

| PBi | ≥1 of strong p41, p39, and OspC | 51 | 20 | 25 | 21 | |

| IgG or IgMb | PKo | 74 | 90 | 100 | 100 | |

| PBi | 68 | 90 | 100 | 100 | ||

Sensitivities were calculated for samples from the EUCALB panel which could be classified unequivocally.

Sensitivities were calculated from positive results by either WB for IgG or WB for IgM, or both.

DISCUSSION

In this study we compared interpretation criteria for WB with different strains of B. burgdorferi sensu lato on the basis of the results obtained with two broad panels of sera: one originating mostly from patients in southern Germany and the other originating from patients from throughout Europe. In contrast to many other studies, in our previous work there was no preselection by serological findings for the sera from the 66 patients with EM and 39 of the serum samples from patients with neuroborreliosis selected due to culture positivity of CSF for B. burgdorferi sensu lato. The high percentage of sera from patients with neuroborreliosis in this panel did not represent the actual prevalence of neuroborreliosis among the patients with different manifestations of LB. However, in contrast to EM, which is the most frequent manifestation of early LB and which is primarily diagnosed clinically, the diagnosis of neuroborreliosis can be quite difficult. On the other hand, approximately half of the samples in the EUCALB panel originated from patients with EM. In our previous work, the recommended interpretation rules were developed and evaluated with the same data, and thus, a bias results. To overcome this, in the present analysis, the criteria developed with one panel were tested with the other panel and vice versa. Due to the different compositions of the panels and the different grades of preselection by serological screening, the resulting sensitivities can be compared only among sera in one group, i.e., the EUCALB panel or the southern German samples.

Since in Europe the immune response of patients with LB seems to be more restricted than that in North America (7), the interpretation criteria for positive WB results recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (1, 8, 10) cannot be used. Interpretation rules must be referred to the borrelial strains for which they have been developed (15). Other European investigators (9, 21–23, 25) proposed the use of criteria that require more reactive bands than the number that we recommend from our results, but none of them systematically evaluated a series of different criteria. These proposals seem to be rather arbitrary. Direct comparison of studies by different investigators is not possible since a variety of strains and different WB protocols have been used. Furthermore, not all bands mentioned in different studies have been identified with monoclonal antibodies.

In principle, an interpretation rule that requires at least two reactive bands among a given combination of bands will be more reliable than a rule that requires only one reactive band, as was previously discussed in detail (16). For WB for IgG with strain PBi, however, a criterion of at least two bands would lead to considerable loss of sensitivity for sera from patients with early LB. Inclusion of sensitive but rather nonspecific antigens in the band combination did not improve the discriminatory ability, as was also shown previously for both strains PKo and PBi (15, 16).

Usually, sera from patients with late-stage LB show a broad band pattern on WB (15), and thus, more strict interpretation rules could be used for such samples. However, for routine purposes, the use of different criteria for sera from patients with early and late stages of disease does not seem to be reasonable. For the current work, grading of band intensities was included only in the analysis for p41 in WB for IgM. More extended evaluation of different band intensities was performed in the previous study but did not seem to be beneficial (15).

For WB for IgG with strain PKo the criterion of at least two reactive bands among p83/100, p58, p43, p39, p30, OspC, p21, p17, and p14 for a positive WB result was established in the preceding study. Considering the reactivities of the EUCALB sera, omission of p17 and inclusion of p60 in this combination seemed slightly superior. However, a 60-kDa protein is recognized by cross-reactive antibodies to many other related and nonrelated bacterial species, as was also shown by Bruckbauer et al. (5). Repeated probing of the rabbit hyperimmune sera obtained by Bruckbauer et al. (5) by our highly resolving WB showed that these reactions of the sera raised against Salmonella typhimurium, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Shigella flexneri, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, Borrelia hermsii, Leptospira interrogans serovar grippotyphosa, and E. coli were actually directed against heat shock protein p60 (13, 17, 20). Thus, problems might occur, for example, for the differential diagnosis of unspecific arthritis caused by either B. burgdorferi sensu lato or any of the species mentioned above. This has not yet been tested with patient sera since the selection of patients by clinical data is almost impossible. On the other hand, for selection by serology, differentiation between true-positive and false-positive results (i.e., cross-reactivity) would be necessary. However, the current results suggest that the differentiation between p60 and the highly specific p58 (15), which is possible only by using highly resolving WB, is not crucial if an interpretation criterion that requires at least two reactive bands is being applied. For strains for which a rule requiring only one reactive band is used, p58 should be omitted from the band combination if discrimination from p60 is not possible.

A few of the serum samples from the EUCALB control group of sera recognized p17, an unique antigen of PKo and other B. afzelii strains. Isolated reactivity to p17 might indicate asymptomatic or past infection with B. burgdorferi sensu lato (14). For this reason this band should not be considered nonspecific, but linking of a band pattern consisting primarily of a strong but almost isolated p17 band with active LB must be done with caution.

For WB for IgM false-positive findings may occur because of the presence of antibodies that cross-react with OspC (5). Faint reactions with OspC should not be taken as positive findings. However, due to the significant loss of sensitivity by use of a rule that requires at least two reactive bands, a clear OspC band by WB for IgM must be considered a positive result. Careful comparison with well-adjusted control sera or pools of sera should be performed. This is also especially important for p41 since only reactions with strong intensities account for a positive result by WB for IgM. Under this premise, no false-positive findings were observed, for example, by testing sera from patients with syphilis or leptospirosis. Since quantification of antigen-antibody reactions can be performed more easily by EIA than by WB, the use of an EIA with recombinant antigens might be a promising approach for confirmatory testing of IgM reactions, too (12, 24).

Considering the results obtained with both panels of sera, we further recommend the previously proposed interpretation rules (15) for WB for IgM with both strains and for WB for IgG with PKo. For WB for IgG with PBi, p30 was included in the band combination proposed previously. WB is used as a confirmatory assay; therefore, specificities of at least 96% were required. By applying these criteria to the panel of sera provided by EUCALB, high sensitivities were obtained for sera from patients with all manifestations of LB (Table 4). Preferential reactivities of sera from patients with different manifestations of LB with different species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato have been reported repeatedly (2, 6, 22, 29). We could show considerable differences between the sensitivities of individual antigens, but if the total combination of antigens that were assessed was considered, only minor differences in sensitivity occurred with sera from patients with most manifestations (15). For sera from patients with EM, B. afzelii PKo proved to be by far the most sensitive. For these reasons and because PKo expresses the highly sensitive antigens p43, p17, and p14 (in contrast to the other strains tested so far) and allows the use of a criterion of at least two reactive bands, we recommend that this strain be used in WB for the serodiagnosis of LB in Europe. Since even in this strain expression of some of the diagnostically important proteins can be downregulated (17a), sufficient expression should be confirmed prior to use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to the European Union Concerted Action on Lyme Borreliosis (EU BIOMED 1 Programme Concerted Action contract BMHI-CT93-1183) for providing sera and clinical descriptions. We thank Edward Guy, Public Health Laboratory Service, Swansea, United Kingdom, for assistance with the manuscript and, together with other members of EUCALB, for valuable discussion. We acknowledge Sofia Reinecke for help with the manuscript. We thank Jürgen Heesemann for generous support of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Association of State and Territorial Public Health Laboratory Directors and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Proceedings of the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Washington, D.C: Association of State and Territorial Public Health Laboratory Directors; 1995. pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Nevot P, Baranton G. Western blot analysis of sera from Lyme borreliosis patients according to the genomic species of the Borrelia strains used as antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01967256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J-C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barbour A G, Tessier S L, Todd W J. Lyme disease spirochetes and ixodid tick spirochetes share a common surface antigenic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1983;41:795–804. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.795-804.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruckbauer H, Preac-Mursic V, Fuchs R, Wilske B. Cross-reactive proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02098084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunikis J, Olsen B, Westman G, Bergström S. Variable serum immunoglobulin responses against different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species in a population at risk for and patients with Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1473–1478. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1473-1478.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dressler F, Ackermann R, Steere A C. Antibody responses to the three genomic groups of Borrelia burgdorferi in European Lyme borreliosis. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:313–318. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.2.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dressler F, Whalen J A, Reinhardt B N, Steere A C. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:392–400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dunand V A, Bretz A-G, Suard A, Praz G, Dayer E, Peter O. Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans and serologic confirmation of infection due to Borrelia afzelii and/or Borrelia garinii by immunoblot. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:159–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00381.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engström S M, Shoop E, Johnson R C. Immunoblot interpretation criteria for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:419–427. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.419-427.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs R, Jauris S, Lottspeich F, Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Soutschek E. Molecular analysis and expression of a Borrelia burgdorferi gene encoding a 22 kDa protein (pC) in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:503–509. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber M A, Shapiro E D, Bell G L, Sampieri A, Padula S J. Recombinant outer surface protein C ELISA for the diagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:724–727. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.3.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen K, Bangsborg J M, Fjordvang H, Pedersen N S, Hindersson P. Immunochemical characterization and isolation of the gene for a Borrelia burgdorferi immunodominant 60-kilodalton antigen common to a wide range of bacteria. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2047–2053. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2047-2053.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hauser U, Krahl H, Peters H, Fingerle V, Wilske B. Impact of strain heterogeneity on Lyme disease serology in Europe: comparison of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using different species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:427–436. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.427-436.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauser U, Lehnert G, Lobentanzer R, Wilske B. Interpretation criteria for standardized Western blots for three European species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1433–1444. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1433-1444.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hauser U, Lehnert G, Wilske B. Diagnostic value of proteins of three Borrelia species (Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato) and implications for development and use of recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1998;5:456–462. doi: 10.1128/cdli.5.4.456-462.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauser, U., and B. Wilske. Unpublished data.

- 17a.Jauris-Heipke, S., B. Roessle, G. Wanner, C. Habermann, D. Roessler, V. Fingerle, G. Lehnert, R. Lobentanzer, I. Pradel, B. Hillenbrand, U. Schulte-Spechtel, and B. Wilske. Osp17, a novel immunodominant outer surface protein of Borrelia afzelii: recombinant expression in Escherichia coli and its use as a diagnostic antigen for serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med. Microbiol. Immunol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Kyhse-Andersen J. Electroblotting of multiple gels: a simple apparatus without buffer tank for rapid transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide to nitrocellulose. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984;10:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luft B J, Gorevic P D, Jiang W, Munoz P, Dattwyler R J. Immunologic and structural characterization of the dominant 66- to 73-kDa antigens of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 1991;146:2776–2782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moskophidis M, Luther B. Wertigkeit des Immunoblots in der Serodiagnostik der Lyme-Borreliose. Lab Med. 1995;19:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norman G L, Antig J M, Bigaignon G, Hogrefe W R. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii Western blots (immunoblots) J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1732–1738. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1732-1738.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Péter O, Bretz A-G, Postic D, Dayer E. Association of distinct species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato with neuroborreliosis in Switzerland. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1997;3:423–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1997.tb00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rauer S, Spohn N, Rasiah C, Neubert U, Vogt A. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using recombinant OspC and the internal 14-kDa flagellin fragment for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:857–861. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.857-861.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryffel K, Péter O, Binet L, Dayer E. Interpretation of immunoblots for Lyme borreliosis using a semiquantitative approach. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1998;4:205–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.1998.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stanek G, O’Connell S, Cimmino M, Aberer E, Kristoferitsch W, Granström M, Guy E, Gray J. European Union concerted action on risk assessment in Lyme borreliosis: clinical case definitions for Lyme borreliosis. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1996;108:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wilske B, Bader L, Pfister H W, Preac-Mursic V. Diagnostik der Lyme-Neuroborreliose (Nachweis der intrathekalen Antikörperbildung) Fortschr Med. 1991;109:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilske B, Busch U, Eiffert H, Fingerle V, Pfister H-W, Rössler D, Preac-Mursic V. Diversity of OspA and OspC among cerebrospinal fluid isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from patients with neuroborreliosis in Germany. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;184:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02456135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wilske B, Fingerle V, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris-Heipke S, Hofmann A, Loy H, Pfister H-W, Rössler D, Soutschek E. Immunoblot using recombinant antigens derived from different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:43–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00193630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Göbel U B, Graf B, Jauris-Heipke S, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Zumstein G. An OspA serotyping system for Borrelia burgdorferi based on reactivity with monoclonal antibodies and OspA sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:340–350. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.340-350.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Schierz G, von Busch K. Immunochemical and immunological analysis of European Borrelia burgdorferi strains. Zentbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Mikrobiol Hyg Ser A. 1986;263:92–102. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]