We review current knowledge of the function of the quiescent center during regeneration and the molecular mechanisms guiding its activation and specification following damage.

Keywords: BRAVO, DNA damage, ERF115, positional information, QC, regeneration, root meristem, stem cells

Abstract

Since its discovery by F.A.L Clowes, extensive research has been dedicated to identifying the functions of the quiescent center (QC). One of the earliest hypotheses was that it serves a key role in regeneration of the root meristem. Recent works provided support for this hypothesis and began to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon. There are two scenarios to consider when assessing the role of the QC in regeneration: one, when the damage leaves the QC intact; and the other, when the QC itself is destroyed. In the first scenario, multiple factors are recruited to activate QC cell division in order to replace damaged cells, but whether the QC has a role in the second scenario is less clear. Both using gene expression studies and following the cell division pattern have shown that the QC is assembled gradually, only to appear as a coherent identity late in regeneration. Similar late emergence of the QC was observed during the de novo formation of the lateral root meristem. These observations can lead to the conclusion that the QC has no role in regeneration. However, activities normally occurring in QC cells, such as local auxin biosynthesis, are still found during regeneration but occur in different cells in the regenerating meristem. Thus, we explore an alternative hypothesis, that following destruction of the QC, QC-related gene activity is temporarily distributed to other cells in the regenerating meristem, and only coalesce into a distinct cell identity when regeneration is complete.

Introduction

The origin of the quiescent center (QC) concept was Clowes’s discovery of a group of cells at the distal part of the root meristem that exhibited low mitotic activity (Clowes, 1954, 1956). While the mitotic rate was the defining feature of the QC, later research has identified other biochemical and molecular characteristics which distinguished these cells from other cells in the meristem. The QC region was marked by high levels of synthesis and accumulation of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA; Kerk and Feldman, 1994; Petersson et al., 2009; Brumos et al., 2018) and an oxidized environment, promoted by relatively low levels of ascorbic acid (Kerk and Feldman, 1995; Jiang et al., 2003). Many genes and markers whose expression was enriched or specific to the QC were later identified, establishing the notion of the QC as a distinct identity (Sabatini et al., 1999, 2003; Haecker et al., 2004; Nawy et al., 2005).

In contrast to the comprehensive characterization of the molecular make up of the QC, the function of this cell type remains largely ambiguous. Ablation experiments have shown that specific destruction of QC cells results in the differentiation of adjacent stem cells (van den Berg et al., 1997), suggesting that one of the roles of the QC is to act as a pattern organizing center that maintains the surrounding stem cells by non-autonomous signals (Scheres, 2007). Indeed, blocking QC–stem cell symplastic connectivity by expressing callose synthase under a QC-enriched promoter results in the differentiation of columella stem cells (Liu et al., 2017). Further, loss of function of the QC-enriched WUSCHEL-LIKE HOMEOBOX5 (WOX5) also led to differentiation of the distal columella stem cells (Sarkar et al., 2007), suggesting that WOX5 itself may be a QC-derived signal, moving to the columella stem cells to prevent their differentiation (Stahl et al., 2009). However, recently it was shown that WOX5 mobility is not required for its function (Berckmans et al., 2020), leaving the identity of the putative QC-derived signal unknown. Alternative models have highlighted the distributed nature of many mobile signals in the meristem, suggesting that a central signal may not be required for stem cell specification (Rahni et al., 2016).

One of the earliest hypotheses for the role of the QC was that it serves as a cell reservoir that allows the root meristem to recover from severe damage by replacing dead or missing cells (Clowes, 1959). Indeed, QC cells were shown to have a broad developmental potential. Surgically isolated Zea mays QCs could completely regenerate entire root meristems in culture without an observable callus intermediate (Feldman and Torrey, 1976). Since the introduction of this hypothesis, many studies have examined the role of the QC during response to damage and regeneration. Here, we review these studies and the putative function of the QC emerging from them. We first consider regeneration scenarios when the QC remains unharmed, and then discuss the more complex process of re-formation following the destruction of the QC itself.

The QC as a cell reservoir for reconstituting damaged meristem cells

The hypothesis of the QC serving as a cell reservoir was raised by Clowes as he observed that the QC cells were resistant to irradiation and began to actively divide in response to damage to the root meristem (Clowes, 1959, 1961, 1970; Clowes and Hall, 1963). Later studies showed that the DNA damage-induced cell death in the meristem requires the DNA damage-sensing machinery, suggesting that it is an active process and opening up the possibility to test this hypothesis directly (Fulcher and Sablowski, 2009; Johnson et al., 2018). The gene SUPPRESSOR OF GAMMA RESPONSE1 (SOG1) is required for the activation of DNA damage response following γ-irradiation (Yoshiyama, 2016). When mutant sog1 plants are irradiated, little to no cell death is observed in the meristem and QC cells do not divide, indicating that activation of the QC is dependent on cell death in the meristem. Remarkably, sog1 mutants could not recover from irradiation and their meristems fully differentiated several days following treatment (Johnson et al., 2018). This failure to recover is likely to be caused by loss of cell division activation in the QC as genetic inhibition of mitotic cell division in the QC resulted in similar failure to recover from bleomycin-induced DNA damage (Heyman et al., 2013; Vilarrasa-Blasi et al., 2014). Consistently, when the QC was damaged using a very high concentration of bleomycin, the meristem could not recover (Sanchez-Corrionero et al., 2019, Preprint). Similarly, cold treatments, which cause DNA damage, resulted in cell death of stem cells and their daughters, but no such death was observed in QC cells (Barlow and Rathfelder, 1985; Hong et al., 2017). Upon return of the cold-treated roots to normal growing temperature, cells in the QC increased their cell division rates to replace the damaged cells (Clowes and Stewart, 1967; Barlow and Rathfelder, 1985).

Why QC cells are resistant to DNA damage is not entirely clear. The QC is characterized by high expression of DNA repair genes (Heyman et al., 2013) which, together with the cells’ low mitotic activity, may protect DNA integrity. Indeed, it was shown that as the frequency of mitotic cell division at the QC increases with plant age; QC cells become more sensitive to bleomycin (Timilsina et al., 2019). However, QC resistance to DNA damage may not be entirely cell autonomous. For example, cold treatment causes the death of the columella stem cell daughters, which remodels auxin distribution in the root meristem. Without this cell death, QC cells become sensitive to the genotoxin zeocin. QC resistance to zeocin can be restored if auxin levels are elevated in the meristem (Hong et al., 2017).

In agreement with the proposed function of the QC as a cell reservoir, it is also activated following physical or mechanical damage to the meristem. Even prior to the identification of the QC, Clowes noticed that cells within that region (broadly referred to as the ‘cytoregenerative center’) are activated following surgical injury to the meristem (Clowes, 1953, 1954). Later, it was shown that cells in the QC respond to mechanical removal or genetic ablation of the root cap by entering rapid mitotic cell division to re-form the missing cap before resuming quiescence (Clowes, 1972a; Barlow, 1974; Tsugeki and Fedoroff, 1999).

Several factors have been suggested to mediate the activation of QC cell divisions in response to meristem damage. The transcription factor gene ETHYLENE RESPONSE FACTOR 115 (ERF115) was shown to mark rare QC cell divisions occurring during normal root growth (Heyman et al., 2013). Expression of this AP2-like transcription factor is induced upon bleomycin treatment or wound damage (Heyman et al., 2013, 2016; Marhava et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019; Canher et al., 2020). This induction correlates with QC cell divisions, and inhibition of these divisions using perturbation of ERF115 activity results in a low recovery rate from bleomycin treatment (Heyman et al., 2013). ERF115 was shown to interact with PHYTOCHROME A SIGNAL TRANSDUCTION1 (PAT1) in dividing QC cells upon bleomycin treatment, and loss of either gene resulted in reduction of periclinal cell division of the QC in response to damage (Heyman et al., 2016). Another factor implicated in the control of QC cells’ quiescence is the MYB transcription factor gene BRASSINOSTEROIDS AT VASCULAR AND ORGANIZING CENTER (BRAVO), mutants of which exhibit excessive QC cell divisions. BRAVO was down-regulated upon bleomycin treatment, while its ectopic overexpression resulted in suppression of DNA damage-induced QC cell divisions and the inability to recover from the treatment (Vilarrasa-Blasi et al., 2014). The expression of both ERF115 and BRAVO is regulated by brassinosteroids (Heyman et al., 2013; Vilarrasa-Blasi et al., 2014), consistent with a role for this hormone in damage and stress responses (Planas-Riverola et al., 2019). However, many factors were shown to be involved in regulation of QC cell division rates, including the plant hormones auxin (Barlow, 1969; Kerk and Feldman, 1994; Sabatini et al., 1999; Friml et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2017; Brumos et al., 2018; Matosevich et al., 2020), cytokinin (Zhang et al., 2013), ethylene (Ortega-Martínez et al., 2007), jasmonate (Chen et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2019), salicylic acid (Wang et al., 2020), and abscisic acid (Zhang et al., 2010), as well as non-hormone factors such as reactive oxygen species (Yu et al., 2016), modulation of the RETINOBLASTOMA-RELATED pathway (Cruz-Ramírez et al., 2013), and activity of the BIRD and SCR transcription factors (Sanchez-Corrionero et al., 2019, Preprint). It was even postulated that disruption of QC quiescence is the result of release from mechanical constraints (Clowes, 1972b). Moreover, severe injury, such as removal of the root cap, alters the relative position of the QC and other tissues in the root meristem, which is a major determinant of cell identity (Efroni, 2018). Thus, while factors regulating QC divisions, such as ERF115, were shown to be under hormonal regulation (Heyman et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2019; Canher et al., 2020), the control of QC quiescence is likely to be complex and multifaceted.

It is important to note that the cells of the QC are not unique in their ability to restore damaged cells. Many cells in the meristem can replace adjacent cells and even create whole new organs (Clowes, 1953; Van den Berg et al., 1995; Kidner et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2006; Sena et al., 2009; Sugimoto et al., 2011; Efroni et al., 2016; Marhava et al., 2019; Canher et al., 2020). One theoretical advantage of replenishing damaged cells by cells from the QC is that the QC’s low mitotic rate and high resistance to DNA damage reduces the incorporation of novel mutations into the plant mature tissues (Heyman et al., 2014). However, while it is easy to see why controlling the number of mutations is important in shoot tissue which gives rise to reproductive gametes (Burian et al., 2016; Watson et al., 2016), it is less clear why such feature would be conserved in roots, which, except in very rare cases, only generate somatic tissues. Moreover, this feature only comes as an advantage to the individual root and not to the plant as a whole, which can readily generate new lateral and adventitious roots (Clowes and Stewart, 1967). Thus, while plausible, this hypothesis awaits empirical support.

Regeneration of the QC and its role in meristem recovery

Early experiments relied on cell division patterns to identify the QC. As damage to the meristem induces mitotic activity in QC cells, these cells can no longer be considered quiescent, and thus, the QC, in a strict sense, no longer exists. The proposed interpretation was that the QC is spent in response to the damage and then later reforms de novo (Clowes, 1959; Barlow, 1974). Indeed, when the entire root tip, including the QC, was excised (Feldman, 1976; Rost and Jones, 1988), or when the QC was specifically ablated (Van den Berg et al., 1995; Xu et al., 2006), a new QC could readily regenerate from the remaining cells in the stump.

This raises two important questions, first, how does the new QC form de novo and second, is the new QC important for the specification of new stem cells and the regeneration of the meristem. There is a conceptual difficulty in answering these questions as it is unclear how to identify the QC during the regeneration process when tissue anatomy is dynamic, most cells are dividing, and expression of molecular markers is highly variable (Efroni et al., 2016). The use of different reporter lines for QC markers often results in contradictory and complex interpretations (Sabatini et al., 1999, 2003; Sarkar et al., 2007; Welch et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2018), and even well-established QC markers, such as WOX5, are not specifically expressed in the QC (Haecker et al., 2004; Ron et al., 2014; Pi et al., 2015; Berckmans et al., 2020). To address this complexity, tissue-specific and single-cell-level profiling of the QC has identified a large number of QC-enriched genes whose combined expression can better define tissue identity than a small number of reporter genes (Nawy et al., 2005; Efroni et al., 2015; Denyer et al., 2019). It also should be noted that the QC is not a uniform entity and, in plants with a large QC, a dynamic variability in QC size and cell division rates was observed (Feldman and Torrey, 1975; Clowes, 1981). Even in the Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) QC, which consist only of 4–6 cells, there is a large cell to cell difference in gene expression (Brennecke et al., 2013; Efroni et al., 2015).

Early studies of QC formation utilized radiometric labeling to map cell division patterns following the surgical removal of the maize (Z. mays) root tip, including the cap and the QC. These studies showed that the recovery of the QC was a gradual process, initiating with the appearance of a small group of cells with low mitotic activity only at ~36 h after dissection. This newly formed QC, originating from the remaining cells at the stump, gradually increased in size until ~72 h after dissection (Feldman, 1976). This timing is consistent with the re-establishment of the QC following the removal of the root cap, which activates cell divisions in the QC. Quiescence is only gradually restored in a group of distally located cells at ~96 h following root cap removal (Barlow, 1974). Taken together, this suggests that the regeneration of the QC itself is a gradual, multistep process.

Further support for this hypothesis comes from studying the dynamic expression of marker genes following laser ablation of the QC. During steady-state growth, maintenance of the normal position and activity of the QC relies on auxin distribution and the spatial expression of the transcription factors PLT1/2/3, SCR, and members of the BIRD family. These markers are broadly expressed in the meristem, but they specifically overlap in the QC and therefore their co-expression is a QC marker (Sabatini et al., 1999, 2003; Aida et al., 2004; Galinha et al., 2007; Welch et al., 2007). Early following the complete ablation of the Arabidopsis QC, cells located above the damage site begin to express the auxin-responsive reporter DR5 (Ulmasov et al., 1997). This expression is correlated with ectopic expression of the QC marker WOX5 in distal stele cells. SCR, PLT1/3, and other QC markers then gradually recover their normal pattern by ~72 h post-ablation (Xu et al., 2006; Shimotohno et al., 2018).

Additional advances in understanding QC formation came from a series of experiments involving the dissection of the root tip, including the QC and surrounding cells (Sena et al., 2009; Efroni et al., 2016). Using bulk transcriptional profiling of regenerating root tips, Sena et al. (2009) observed that a large number of QC-enriched markers were up-regulated in the stump very early, starting from 5 h after dissection. However, which cells in the stump expressed these markers was unclear. At 24 h after the dissection, expression of one of the markers, WOX5, was apparent in the stele and ground tissue, but only recovered its normal expression pattern at the center of the meristem at ~72 h after the cut. The recovery of a centrally localized WOX5 expression relied on the polar auxin transport machinery, as its disruption using the chemical inhibitor 1-naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) resulted in broad distal expression of WOX5, similar to uncut roots subjected to the same treatment (Sabatini et al., 1999; Sena et al., 2009). Remarkably, regeneration of other specialized cell types, such as the columella, preceded the formation of a localized QC and could be observed already at 24 h after the cut, suggesting that the QC does not play a role in the re-specification of these tissues. The PLTs were shown to be required for maintaining the QC, and tip regeneration was abolished in quadruple plt1/2/3/4 mutants (Durgaprasad et al., 2019). However, as these factors are not QC specific and are broadly expressed throughout the meristem, it is unknown whether this failure to regenerate is related to disrupted QC specification or to a general disruption of cell proliferation patterns (Galinha et al., 2007; Mähönen et al., 2014).

Lineage tracing in meristems regenerating from tip dissections confirmed previous observations that the newly formed QC is specified from vasculature cells in the stele (Efroni et al., 2016). While Sena et al. (2009) showed QC marker expression at 5 h after the cut, high-resolution, single-cell profiling revealed that QC markers begin to be expressed in specific stele cells even earlier, and were already apparent at 3 h after the cut. However, these cells could not be strictly classified as a QC, as, together with QC markers, they also expressed markers for multiple distal tissues, including the lateral root cap and columella. While cells with coherent columella identity were identified at 16 h after the cut, cells with consistent expression of QC markers were only apparent at 46 h (Efroni et al., 2016).

Taken together, evidence suggest that the QC, as a coherent identity at a central position, is only established late in regeneration, and is the hallmark of a mature meristem rather than a driver of regeneration. This view is consistent with the timing of QC formation during normal development. Indeed, Clowes already noted that the QC is absent in embryos and lateral root primordia, and does not appear until later stages of meristem development (Clowes, 1958). In the Arabidopsis embryo, the QC is first apparent during late globular–early heart stage where it is formed from a single division of the hypophysis (Dolan et al., 1993; Scheres et al., 1994). While it is hard to define the exact point of root meristem formation in the embryo, the bulk of the embryonic root is not derived from the QC, but from its surrounding tissues, which already express tissue-specific markers at this early stage (Scheres et al., 1994; ten Hove et al., 2015).

The formation of a QC also occurs late during the development of the (lateral root) LR meristem, which initiates de novo from designated cells in the pericycle (Trinh et al., 2018). Using promoter fusion markers, QC specification was timed to stage IV–V of LR development, following the establishment of a domed root meristem primordium (Goh et al., 2016). Similar late QC emergence was reported for hypocotyl-derived roots (Rovere et al., 2016). A recent highly detailed single-cell RNA-Seq analysis of early stages of LR initiation provide a unique view of the QC specification process. This study found that QC markers are expressed early in the initiation of the LR, but their expression is distributed amongst different precursor cell types. Cells whose expression profile resembled that of the mature QC only emerge at later stages (Serrano-Ron et al., 2021).

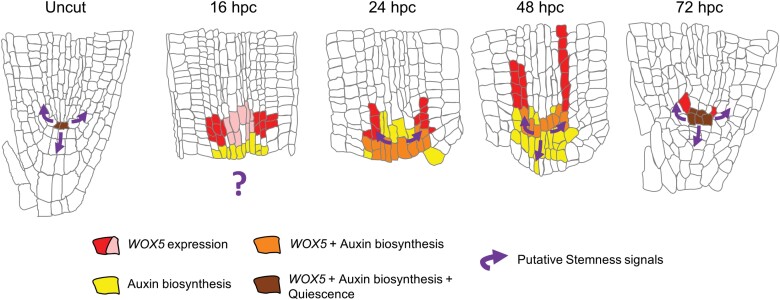

If the QC is formed late during regeneration, one could ask whether it even plays a role in this process. As noted above, the functions of the QC in meristem development are still far from being resolved, making this question hard to address. However, this question may not have a simple yes/no answer. QC-enriched genes are expressed throughout regeneration, but their expression is distributed in the meristem and only progressively assembled at their central position at the end of the process. Thus, a possible interpretation is that at least some QC characteristics are not missing during regeneration, but are transiently distributed to different cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Spatiotemporal distribution of QC characteristics during regeneration. Following the removal of the root tip, including the QC, characteristics of the QC become disperse and converge at the center of the stem cell niche late during the regeneration process. hpc, hours post-cut. Red/pink indicate strong/weak WOX5 expression, respectively. Yellow, auxin-producing cells. Purple arrows indicate putative signals promoting stem cell specification.

One QC-ascribed function relevant for regeneration is the specification of stem cells. Due to the lack of a unique stem cell marker, it is not known when exactly the stem cells are formed during regeneration. By tracing cell division patterns, it was shown that new stem cell-like division patterns appear 24 h after the remove of the root stem cell niche, prior to the formation of a focused QC (Efroni et al., 2016). If the specification of stem cells relies on an organizer-derived mobile signal, it should emanate from a transient group of QC-like cells located at the center of the stele. The expression of WOX5, shown to be important for specification of columella stem cells, is broad at this time point, but does overlap the region of stem cell formation (Fig. 1). However, this hypothesis cannot be directly addressed at this time as the nature of the stem cell specification signal is still unknown.

A different function of the QC is to supply the meristem with locally synthesized auxin (Brumos et al., 2018; Savina et al., 2020). Studying the role of auxin synthesis during regeneration following the removal of the root tip, Matosevich et al. (2020) showed that, similar to the normal growth of the meristem, regeneration requires local production of auxin. However, instead of relying on a newly formed QC, auxin is produced by existing pericycle cells and by newly specified cells near the cut site. These cells provide the temporary auxin supply to support regeneration until the QC and meristem organization is re-established (Matosevich et al., 2020). Notably, these cells differ from the WOX5-expressing cells, highlighting the temporary distributed nature of the process (Fig. 1).

Concluding remarks

Ever since its discovery, the function of the QC has remained a constant topic of interest. Suggestions varied from these cells serving as a cell reservoir, as a signaling center, as a maintainer of stem cell identity, or, as Clowes suggested, perhaps having no specific function at all (Clowes and Stewart, 1967; Clowes, 1972b). Today, we have clear evidence that cells in the position of the QC are required for normal meristem patterning and development (Rahni et al., 2016). However, because plant cells are immobile, their position is highly correlated with their identity, and it remains difficult to identify which functions are performed by the QC due to its inherent identity and which are determined by the relative position of these cells within the meristem. The identification of specific molecular pathways acting in the QC, such as production of hormones (Petersson et al., 2009; Brumos et al., 2018), growth-promoting peptides (Matsuzaki et al., 2010), or symplastic transported signals (Liu et al., 2017; Xu et al., 2021), provides us with the opportunity to study their roles outside the context of the steady-state root meristem. Focusing on specific processes rather than on the QC as a coherent identity can give us a clearer picture of the mechanisms of root regeneration and the function of different cells during this dynamic process.

Acknowledgements

RM is a fellow of the Ariane de Rothschild Women Doctoral Program. This work was supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute International Research Scholar grant (55008730) and the Israel Science Foundation (ISF966/17). The authors declare no conflicting interests.

Author contributions

RM and IE: writing—review & editing.

References

- Aida M, Beis D, Heidstra R, Willemsen V, Blilou I, Galinha C, Nussaume L, Noh YS, Amasino R, Scheres B. 2004. The PLETHORA genes mediate patterning of the Arabidopsis root stem cell niche. Cell 119, 109–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow PW. 1969. Cell growth in the absence of division in a root meristem. Planta 88, 215–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow PW. 1974. Regeneration of the cap of primary roots of Zea mays. New Phytologist 73, 937–954. [Google Scholar]

- Barlow PW, Rathfelder EL. 1985. Cell division and regeneration in primary root meristems of Zea mays recovering from cold treatment. Environmental and Experimental Botany 25, 303–314. [Google Scholar]

- Berckmans B, Kirschner G, Gerlitz N, Stadler R, Simon R. 2020. CLE40 signaling regulates root stem cell fate. Plant Physiology 182, 1776–1792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennecke P, Anders S, Kim JK, et al. 2013. Accounting for technical noise in single-cell RNA-seq experiments. Nature Methods 10, 1093–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumos J, Robles LM, Yun J, Vu TC, Jackson S, Alonso JM, Stepanova AN. 2018. Local auxin biosynthesis is a key regulator of plant development. Developmental Cell 47, 306–318.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burian A, Barbier de Reuille P, Kuhlemeier C. 2016. Patterns of stem cell divisions contribute to plant longevity. Current Biology 26, 1385–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canher B, Heyman J, Savina M, et al. 2020. Rocks in the auxin stream: wound-induced auxin accumulation and ERF115 expression synergistically drive stem cell regeneration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 117, 16667–16677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q, Sun J, Zhai Q, et al. 2011. The basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor MYC2 directly represses PLETHORA expression during jasmonate-mediated modulation of the root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. The Plant Cell 23, 3335–3352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FA. 1961. Effects of beta-radiation on meristems. Experimental Cell Research 25, 529–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1953. The cytogenerative centre in roots with broad columellas. New Phytologist 52, 48–57. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1954. The promeristem and the minimal constructional centre in grass root apices. New Phytologist 53, 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1956. Nucleic acids in root apical meristems of Zea. New Phytologist 55, 29–34. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1958. Development of quiescent centres in root meristems. New Phytologist 57, 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1959. Reorganization of root apices after irradiation. Annals of Botany 23, 205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1970. The immediate response of the quiescent center to X-rays. New Phytologist 69, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1972a. Regulation of mitosis in roots by their caps. Nature 235, 143–144. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1972b. The control of cell proliferation within root meristems. In: Miller MW, Kuehnert CC, eds. The dynamics of meristem cell populations. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL. 1981. The difference between open and closed meristems. Annals of Botany 48, 761–767. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL, Hall EJ. 1963. The quiescent centre in root meristems of Vicia faba and its behaviour after acute X-irradiation and chronic gamma irradiation. Radiation Botany 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar]

- Clowes FAL, Stewart H. 1967. Recovery from dormancy in roots. New Phytologist 66, 115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz-Ramírez A, Díaz-Triviño S, Wachsman G, et al. 2013. A SCARECROW–RETINOBLASTOMA protein network controls protective quiescence in the Arabidopsis root stem cell organizer. PLoS Biology 11, e1001724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denyer T, Ma X, Klesen S, Scacchi E, Nieselt K, Timmermans MCP. 2019. Spatiotemporal developmental trajectories in the Arabidopsis root revealed using high-throughput single-cell RNA sequencing. Developmental Cell 48, 840–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan L, Janmaat K, Willemsen V, Linstead P, Poethig S, Roberts K, Scheres B. 1993. Cellular organisation of the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Development 119, 71–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durgaprasad K, Roy MV, Venugopal M A, Kareem A, Raj K, Willemsen V, Mähönen AP, Scheres B, Prasad K. 2019. Gradient expression of transcription factor imposes a boundary on organ regeneration potential in plants. Cell Reports 29, 453–463.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni I. 2018. A conceptual framework for cell identity transitions in plants. Plant & Cell Physiology 59, 691–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni I, Ip PL, Nawy T, Mello A, Birnbaum KD. 2015. Quantification of cell identity from single-cell gene expression profiles. Genome Biology 16, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efroni I, Mello A, Nawy T, Ip PL, Rahni R, DelRose N, Powers A, Satija R, Birnbaum KD. 2016. Root regeneration triggers an embryo-like sequence guided by hormonal interactions. Cell 165, 1721–1733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LJ. 1976. The de novo origin of the quiescent center regenerating root apices of Zea mays. Planta 128, 207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LJ, Torrey JG. 1975. The quiescent center and primary vascular tissue pattern formation in cultured roots of Zea. Canadian Journal of Botany 53, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman LJ, Torrey JG. 1976. The isolation and culture in vitro of the quiescent center of Zea mays. American Journal of Botany 63, 345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Friml J, Benková E, Blilou I, et al. 2002. AtPIN4 mediates sink-driven auxin gradients and root patterning in Arabidopsis. Cell 108, 661–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulcher N, Sablowski R. 2009. Hypersensitivity to DNA damage in plant stem cell niches. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 106, 20984–20988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galinha C, Hofhuis H, Luijten M, Willemsen V, Blilou I, Heidstra R, Scheres B. 2007. PLETHORA proteins as dose-dependent master regulators of Arabidopsis root development. Nature 449, 1053–1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goh T, Toyokura K, Wells DM, et al. 2016. Quiescent center initiation in the Arabidopsis lateral root primordia is dependent on the SCARECROW transcription factor. Development 143, 3363–3371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haecker A, Gross-Hardt R, Geiges B, Sarkar A, Breuninger H, Herrmann M, Laux T. 2004. Expression dynamics of WOX genes mark cell fate decisions during early embryonic patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana. Development 131, 657–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman J, Cools T, Canher B, et al. 2016. The heterodimeric transcription factor complex ERF115–PAT1 grants regeneration competence. Nature Plants 2, 16165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman J, Cools T, Vandenbussche F, et al. 2013. ERF115 controls root quiescent center cell division and stem cell replenishment. Science 342, 860–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyman J, Kumpf RP, De Veylder L. 2014. A quiescent path to plant longevity. Trends in Cell Biology 24, 443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong JH, Savina M, Du J, Devendran A, Kannivadi Ramakanth K, Tian X, Sim WS, Mironova VV, Xu J. 2017. A sacrifice-for-survival mechanism protects root stem cell niche from chilling stress. Cell 170, 102–113.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Meng YL, Feldman LJ. 2003. Quiescent center formation in maize roots is associated with an auxin-regulated oxidizing environment. Development 130, 1429–1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RA, Conklin PA, Tjahjadi M, Missirian V, Toal T, Brady SM, Britt AB. 2018. SUPPRESSOR OF GAMMA RESPONSE1 links DNA damage response to organ regeneration. Plant Physiology 176, 1665–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerk N, Feldman L. 1994. The quiescent center in roots of maize: initiation, maintenance and role in organization of the root apical meristem. Protoplasma 183, 100–106. [Google Scholar]

- Kerk NM, Feldman LJ. 1995. A biochemical model for the initiation and maintenance of the quiescent center: implications for organization of root meristems. Development 121, 2825–2833. [Google Scholar]

- Kidner C, Sundaresan V, Roberts K, Dolan L. 2000. Clonal analysis of the Arabidopsis root confirms that position, not lineage, determines cell fate. Planta 211, 191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Xu M, Liang N, Zheng Y, Yu Q, Wu S. 2017. Symplastic communication spatially directs local auxin biosynthesis to maintain root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 114, 4005–4010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mähönen AP, Ten Tusscher K, Siligato R, Smetana O, Díaz-Triviño S, Salojärvi J, Wachsman G, Prasad K, Heidstra R, Scheres B. 2014. PLETHORA gradient formation mechanism separates auxin responses. Nature 515, 125–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhava P, Hoermayer L, Yoshida S, Marhavý P, Benková E, Friml J. 2019. Re-activation of stem cell pathways for pattern restoration in plant wound healing. Cell 177, 957–969.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matosevich R, Cohen I, Gil-Yarom N, Modrego A, Friedlander-Shani L, Verna C, Scarpella E, Efroni I. 2020. Local auxin biosynthesis is required for root regeneration after wounding. Nature Plants 6, 1020–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki Y, Ogawa-Ohnishi M, Mori A, Matsubayashi Y. 2010. Secreted peptide signals required for maintenance of root stem cell niche in Arabidopsis. Science 329, 1065–1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawy T, Lee JY, Colinas J, Wang JY, Thongrod SC, Malamy JE, Birnbaum K, Benfey PN. 2005. Transcriptional profile of the Arabidopsis root quiescent center. The Plant Cell 17, 1908–1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega-Martínez O, Pernas M, Carol RJ, Dolan L. 2007. Ethylene modulates stem cell division in the Arabidopsis thaliana root. Science 317, 507–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersson SV, Johansson AI, Kowalczyk M, Makoveychuk A, Wang JY, Moritz T, Grebe M, Benfey PN, Sandberg G, Ljung K. 2009. An auxin gradient and maximum in the Arabidopsis root apex shown by high-resolution cell-specific analysis of IAA distribution and synthesis. The Plant Cell 21, 1659–1668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi L, Aichinger E, van der Graaff E, Llavata-Peris CI, Weijers D, Hennig L, Groot E, Laux T. 2015. Organizer-derived WOX5 signal maintains root columella stem cells through chromatin-mediated repression of CDF4 expression. Developmental Cell 33, 576–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planas-Riverola A, Gupta A, Betego I, Bosch N, Iban M. 2019. Brassinosteroid signaling in plant development and adaptation to stress. 146, dev151894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahni R, Efroni I, Birnbaum KD. 2016. A case for distributed control of local stem cell behavior in plants. Developmental Cell 38, 635–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron M, Kajala K, Pauluzzi G, et al. 2014. Hairy root transformation using Agrobacterium rhizogenes as a tool for exploring cell type-specific gene expression and function using tomato as a model. Plant Physiology 166, 455–469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rost TL, Jones TJ. 1988. Pea root regeneration after tip excisions at different levels: polarity of new growth. Annals of Botany 61, 513–523. [Google Scholar]

- Rovere FD, Fattorini L, Ronzan M, Falasca G, Altamura MM. 2016. The quiescent center and the stem cell niche in the adventitious roots of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Signaling & Behavior 11, e1176660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S, Beis D, Wolkenfelt H, et al. 1999. An auxin-dependent distal organizer of pattern and polarity in the Arabidopsis root. Cell 99, 463–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini S, Heidstra R, Wildwater M, Scheres B. 2003. SCARECROW is involved in positioning the stem cell niche in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Genes & Development 17, 354–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Corrionero A, Perez-Garcia P, Cabrera J, Silva-Navas J, Perianez-Rodriguez J, Gude I, Del Pozo JC, Moreno-Risueno MA. 2019. Root patterning and regeneration are mediated by the quiescent center and involve Bluejay, Jackdaw and Scarecrow regulation of vasculature factors. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/803973. [Preprint]. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar AK, Luijten M, Miyashima S, Lenhard M, Hashimoto T, Nakajima K, Scheres B, Heidstra R, Laux T. 2007. Conserved factors regulate signalling in Arabidopsis thaliana shoot and root stem cell organizers. Nature 446, 811–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savina MS, Pasternak T, Omelyanchuk NA, Novikova DD, Palme K, Mironova VV, Lavrekha VV. 2020. Cell dynamics in WOX5-overexpressing root tips: the impact of local auxin biosynthesis. Frontiers in Plant Science 11, 560169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B. 2007. Stem-cell niches: nursery rhymes across kingdoms. Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 8, 345–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheres B, Wolkenfelt H, Willemsen V, Terlouw M, Lawson E, Dean C, Weisbeek P. 1994. Embryonic origin of the Arabidopsis primary root and root meristem initials. Development 120, 2475–2487. [Google Scholar]

- Sena G, Wang X, Liu HY, Hofhuis H, Birnbaum KD. 2009. Organ regeneration does not require a functional stem cell niche in plants. Nature 457, 1150–1153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano-Ron L, Perez-Garcia P, Sanchez-Corrionero A, Gude I, Cabrera J, Ip P-L, Birnbaum KD, Moreno-Risueno MA. 2021. Reconstruction of lateral root formation through single-cell RNA-seq reveals order of tissue initiation. Molecular Plant 184, 107229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimotohno A, Heidstra R, Blilou I, Scheres B. 2018. Root stem cell niche organizer specification by molecular convergence of PLETHORA and SCARECROW transcription factor modules. Genes & Development 32, 1085–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahl Y, Wink RH, Ingram GC, Simon R. 2009. A signaling module controlling the stem cell niche in Arabidopsis root meristems. Current Biology 19, 909–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugimoto K, Gordon SP, Meyerowitz EM. 2011. Regeneration in plants and animals: dedifferentiation, transdifferentiation, or just differentiation? Trends in Cell Biology 21, 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ten Hove CA, Lu KJ, Weijers D. 2015. Building a plant: cell fate specification in the early Arabidopsis embryo. Development 142, 420–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timilsina R, Kim JH, Nam HG, Woo HR. 2019. Temporal changes in cell division rate and genotoxic stress tolerance in quiescent center cells of Arabidopsis primary root apical meristem. Scientific Reports 9, 3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh CD, Laplaze L, Guyomarc’h S. 2018. Lateral root formation: building a meristem de novo. Annual Plant Reviews Online 1, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Tsugeki R, Fedoroff NV. 1999. Genetic ablation of root cap cells in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 96, 12941–12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmasov T, Murfett J, Hagen G, Guilfoyle TJ. 1997. Aux/IAA proteins repress expression of reporter genes containing natural and highly active synthetic auxin response elements. The Plant Cell 9, 1963–1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg C, Willemsen V, Hage W, Weisbeek P, Scheres B. 1995. Cell fate in the Arabidopsis root meristem determined by directional signalling. Nature 378, 62–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg C, Willemsen V, Hendriks G, Weisbeek P, Scheres B. 1997. Short-range control of cell differentiation in the Arabidopsis root meristem. Nature 390, 287–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vilarrasa-Blasi J, González-García MP, Frigola D, et al. 2014. Regulation of plant stem cell quiescence by a brassinosteroid signaling module. Developmental Cell 30, 36–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Rong D, Chen D, Xiao Y, Liu R, Wu S, Yamamuro C. 2020. Salicylic acid promotes quiescent center cell division through ROS accumulation and down‐regulation of PLT1, PLT2, and WOX5. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology 63, 583–596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson JM, Platzer A, Kazda A, Akimcheva S, Valuchova S, Nizhynska V, Nordborg M, Riha K. 2016. Germline replications and somatic mutation accumulation are independent of vegetative life span in Arabidopsis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA 113, 12226–12231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch D, Hassan H, Blilou I, Immink R, Heidstra R, Scheres B. 2007. Arabidopsis JACKDAW and MAGPIE zinc finger proteins delimit asymmetric cell division and stabilize tissue boundaries by restricting SHORT-ROOT action. Genes & Development 21, 2196–2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Hofhuis H, Heidstra R, Sauer M, Friml J, Scheres B. 2006. A molecular framework for plant regeneration. Science 311, 385–388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Gu X, Yu Q, Liu Y, Bian X, Wang R, Yang M, Wu S. 2021. Time-course observation of the reconstruction of stem cell niche in the intact root. Plant Physiology 85, 1652–1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshiyama KO. 2016. SOG1: a master regulator of the DNA damage response in plants. Genes and Genetic Systems 90, 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Tian H, Yue K, Liu J, Zhang B, Li X, Ding Z. 2016. A P-loop NTPase regulates quiescent center cell division and distal stem cell identity through the regulation of ROS homeostasis in Arabidopsis root. PLoS Genetics 12, e1006175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Han W, De Smet I, Talboys P, Loya R, Hassan A, Rong H, Jürgens G, Paul Knox J, Wang MH. 2010. ABA promotes quiescence of the quiescent centre and suppresses stem cell differentiation in the Arabidopsis primary root meristem. The Plant Journal 64, 764–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Swarup R, Bennett M, Schaller GE, Kieber JJ. 2013. Cytokinin induces cell division in the quiescent center of the Arabidopsis root apical meristem. Current Biology 23, 1979–1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Lozano-Torres JL, Blilou I, Zhang X, Zhai Q, Smant G, Li C, Scheres B. 2019. A jasmonate signaling network activates root stem cells and promotes regeneration. Cell 177, 942–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]