Abstract

In recent years, nanomaterials have aroused extensive research interest in the world's material science community. Electrospinning has the advantages of wide range of available raw materials, simple process, small fiber diameter and high porosity. Electrospinning as a nanomaterial preparation technology with obvious advantages has been studied, such as its influencing parameters, physical models and computer simulation. In this review, the influencing parameters, simulation and models of electrospinning technology are summarized. In addition, the progresses in applications of the technology in biomedicine, energy and catalysis are reported. This technology has many applications in many fields, such as electrospun polymers in various aspects of biomedical engineering. The latest achievements in recent years are summarized, and the existing problems and development trends are analyzed and discussed.

Introduction

Nanowires, nanowhiskers, nanofibers, nanotubes and other one-dimensional nanostructured materials have excellent performance in improving the optical, electrical, thermal and mechanical properties of functional materials and composites. Dielectric and semiconductor nanomaterials made of these one-dimensional materials are widely used in the fields of photocatalysis, sensors, drug delivery, bifunctional materials and so on [1–10].

Many nanofiber fabrication techniques have been developed [11], such as splitting of bicomponent fibers [12], melt blowing [13], physical drawing [14], dry–wet spinning [15], phase separation [16], self-assembling [17], centrifugal spinning [18] and electrospinning [19].

Electrospinning is one of the most versatile, simplest and effective technologies compared with template polymerization and melt spraying [20–23]. It is also the only method for large-scale production of continuous nanofibers in industry [24, 25]

Electrospinning also has the advantages of wide range of available raw materials, simple process, small fiber diameter and high porosity. Although electrospinning technology originated in the early twentieth century, it was not widely used until around 2000. There are quite a few research results on the instrument development and the influence of process parameters.

History

Electrospinning technology can be traced back to 1897. Rayleigh et al. [26–29] studied the phenomenon of charged liquid changing from cylinder to bead. In 1900, Cooley [30] applied for the world's first patent for electrospinning and invented four types of indirectly charged spinning heads—a conventional head, a coaxial head, an air assisted model and a spinneret featuring a rotating distributor. It generally believes that this is the beginning of electrospinning industrialization. However, Morton's 1902 patent on electrospinning lacks some key details [31]. Then, Zeleny [32–37] mathematically simulated the behavior of a fluid under static electricity. Anton [38–44] applied for many patents in the USA, France and other countries between 1931 and 1944, contributing to the electrospinning technology. In 1936, Norton [45] applied for the patent of melt electrospinning. Cellulose acetate nanofibers were prepared by electrospinning with dichloroethane and ethanol as solvents in 1938 by N.D. Rozenblum and I.V. Petryanov Sokolov in 1938. The cellulose acetate nanofibers were applied to filter materials to enhance the toughness and durability of the materials. The materials were produced in a large quantity by Tver antivirus surface ware factory in 1939 [46]. From 1964 to 1966, Taylor [47–49] established the "leaky dielectric model" for electrospinning technology, which laid a theoretical foundation for the "Taylor cone." In 1966, Simons [50] invented a process for printing nonwoven fabrics using electrospinning technology. In 1971, Baumgarten [51] prepared acrylic fibers with DMF as solvent by electrospinning. In 1978, Annis et al. [52] published work examining electrospun polyurethane mats for use as vascular pros thesis. In 1981, Larrondo and St. John Manley [53–55] carried out electrospinning of polyethylene and polypropylene fibers from the melt. In 1985, Fisher et al. [56] studied electrospinning applications in arterial repair materials. In 1996, Reneker and Chun [57] successfully prepared more than 20 kinds of polymer nanofibers by electrospinning technology. In 2009, Jirsak et al. [58] invented a needleless electrospinning technology, and then, the Czech company Elmarco produced the world's first industrial electrospinning machine, Nanospider.

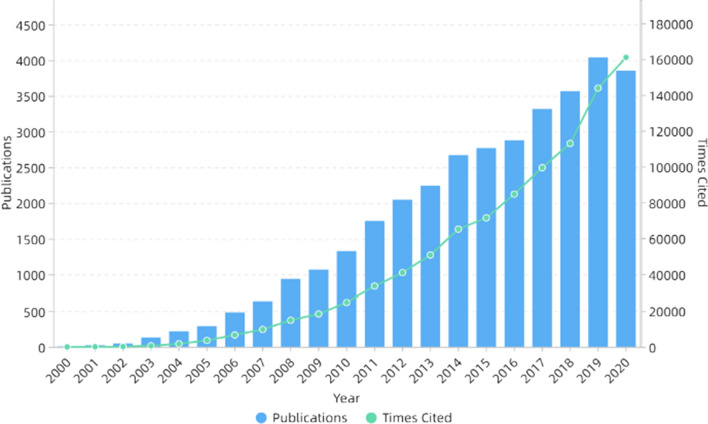

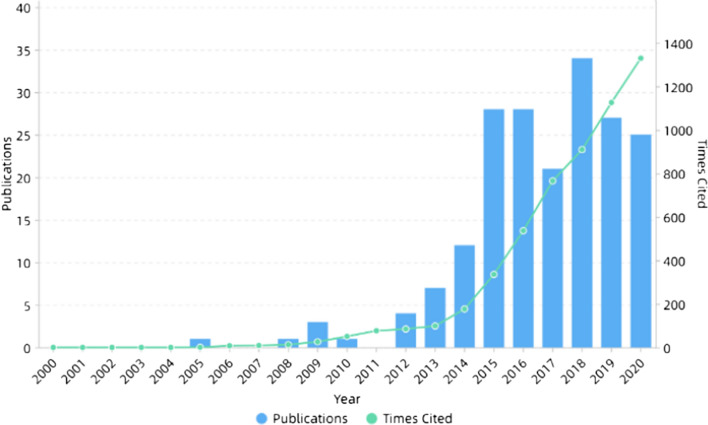

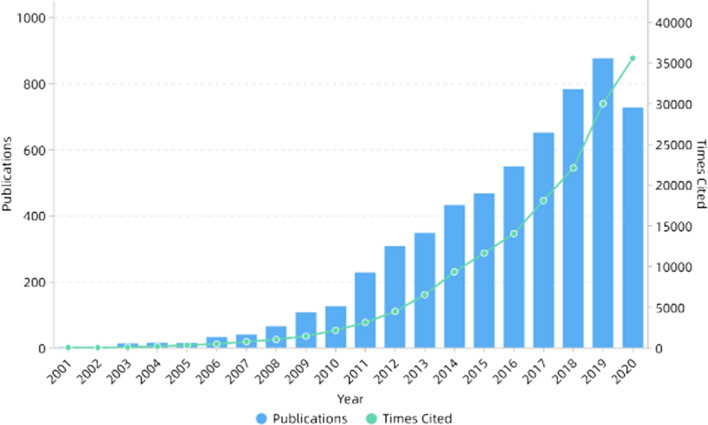

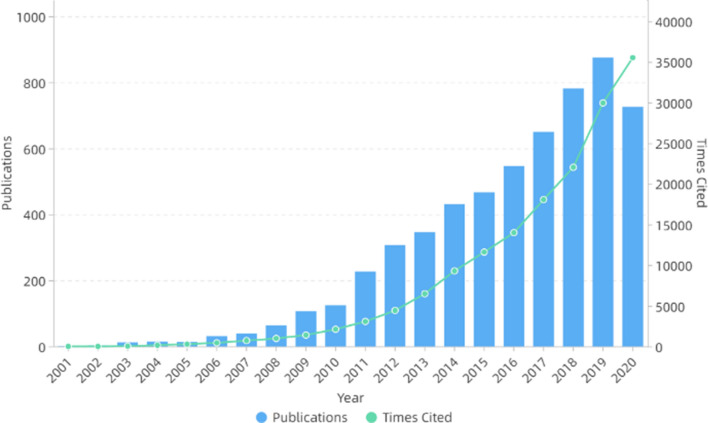

In the next decade or so, electrospinning technology was not only widely used in the biomedical field [59–61], but also widely used in energy [62–64], catalysis [65–67] and other fields because of its simple process and wide applicability. In addition, electrospinning can also be used to prepare self-assembled nanocomposites [68–72]. The number of publications and cited frequency of electrospinning increased year by year, as shown in Fig. 1. Figure 2 shows the number of publications on electrospinning in various countries. It can be seen that China published the most, followed by the USA and South Korea.

Figure 1.

Number of publications and times cited on electrospinning. All the data used are from Web of Science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Figure 2.

Number of publications on electrospinning in various countries. All the data used are from Web of Science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Process

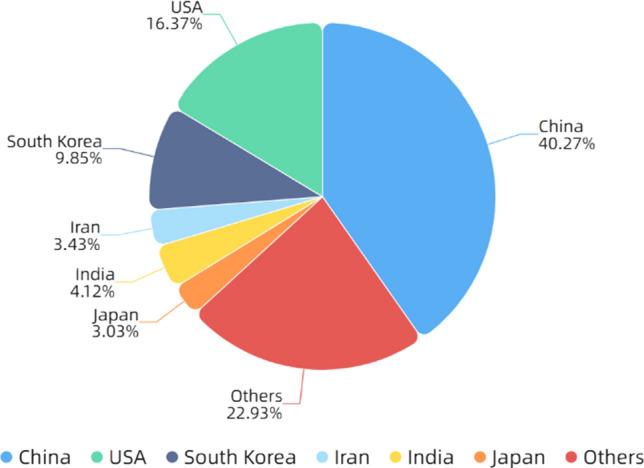

The basic principle of electrospinning is that solution, suspension or melt is sprayed in a strong electric field to form continuous fibers. The basic electrospinning device consists of three parts (a) a high voltage power supply (b) a spinneret (c) a collector. Figure 3 shows the basic device of electrospinning. In the case of solution electrospinning, first, because of the surface tension of the solution, droplets are formed on the spinneret with induced charge on the surface [73]. When the electrostatic force is equivalent to the surface tension of the solution, the droplet changes from hemispheric shape to cone shape, which is called Taylor cone [49]. When the electrostatic force is greater than the surface tension, the solution can overcome the surface tension and form jets. In the process of reaching the collection device, the electrostatic force makes the jets stretched and the solvent evaporated, leaving only solid fibers. The collection device can collect the solid fibers with complex network structure [74]. The same is true for melt and suspension electrospinning.

Figure 3.

The basic equipment of electrospinning. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Electrospinning. Accessed 3 August 2021

There are many types of electrospinning equipment on the market, most of which is innovative only in the jet device and collection device [75]. The traditional instrument uses electrode material as spinneret. In recent years, the needleless nozzle has been developed, which can be divided into two types: the rotary nozzle and the static nozzle. It can address the problems of needle clogging and low yield. It can be used in industrial production, but it is difficult to control the morphology and distribution of nanofibers [76]. The collection device is generally divided into vertical arrangement and horizontal arrangement [77, 78]. The difference between the two is the droplet formation power is different. When the spinneret and collecting plate are arranged horizontally, droplets are generated by electrostatic force, and gravity is also involved in the horizontal arrangement [79, 80].

Up to now, more than 100 kinds of nanofibers of polymers and blends have been successfully prepared by electrospinning, with diameters ranging from several nanometers to hundreds of microns [81]. Besides, if the same polymer is dissolved in different solvents, the morphology of nanofibers prepared will be different [82, 83].

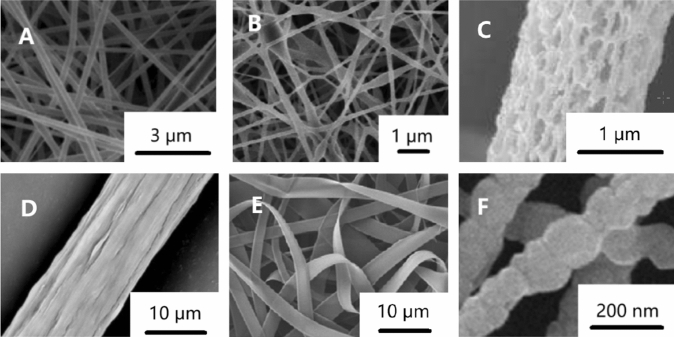

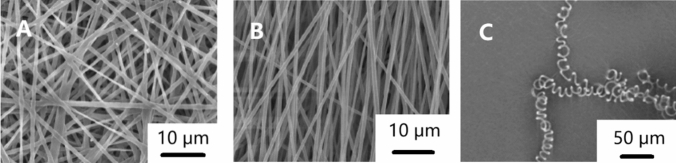

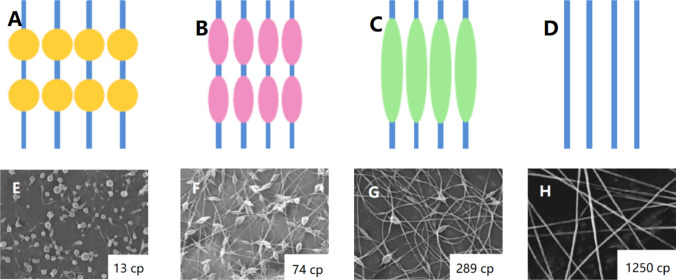

Electrospun nanofibers can be classified into many types according to different classification methods [11]. According to the chemical composition, they can be divided into inorganic nanofibers [84], organic nanofibers [85, 86], carbonaceous nanofibers [87, 88] and inorganic–organic hybrid nanofibers [89]. According to the morphology of nanofibers, as shown in Fig. 4, they can be divided into columnar nanofibers [90], beaded nanofibers [91], porous nanofibers [92], grooved nanofibers [93], nanograin nanofibers [94], nanobelt nanofibers [95] and so on. As shown in Fig. 5, according to the fiber orientation, it can be divided into random-distributed nanofibers [96], aligned nanofibers [96], crimped nanofibers [97] and so on.

Figure 4.

Morphology of electrospun nanofibers a columnar nanofibers [90] b beaded nanofibers [91] c porous nanofibers [92] d grooved nanofibers [93] e nanobelt nanofibers [95] f nanograin nanofibers [94].

Reproduced with permission from reference [90]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [91]. Copyright 2012, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [92]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier Ltd. Reproduced with permission from reference [93]. Copyright 2016, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [94]. Copyright 2013, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [95]. Copyright 2011, Elsevier Ltd

Figure 5.

Orientation of electrospun nanofibers a random-distributed arrangement [96] b aligned nanofibers [96] c crimped nanofibers [97].

Reproduced with permission from reference [96]. Copyright 2015, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [97]. Copyright 2014, American Chemical Society

Parameters

Besides the advantages of simple process and wide range of raw materials, electrospinning can control the morphology, orientation and pore size of nanofibers by adjusting the parameters [98, 99]. There are many parameters affecting electrospinning, some of which are uncontrollable. The controllable parameters can be divided into solution parameters, processing parameters and ambient parameters [100]. The solution parameters include concentration, viscosity, molecular weight, conductivity, surface tension and solvent type. The process parameters include applied voltage, flow rate and distance from jet device to collection device. The ambient parameters include temperature and humidity. However, if the parameters are adjusted appropriately, uniform and bead-free nanofibers with suitable diameter can be prepared. Although the National Science Foundation defines fibers with diameter less than 100 nm as nanofibers, in fact, submicron fibers are more widely used in many fields such as tissue engineering [101].

Solution parameters

Concentration

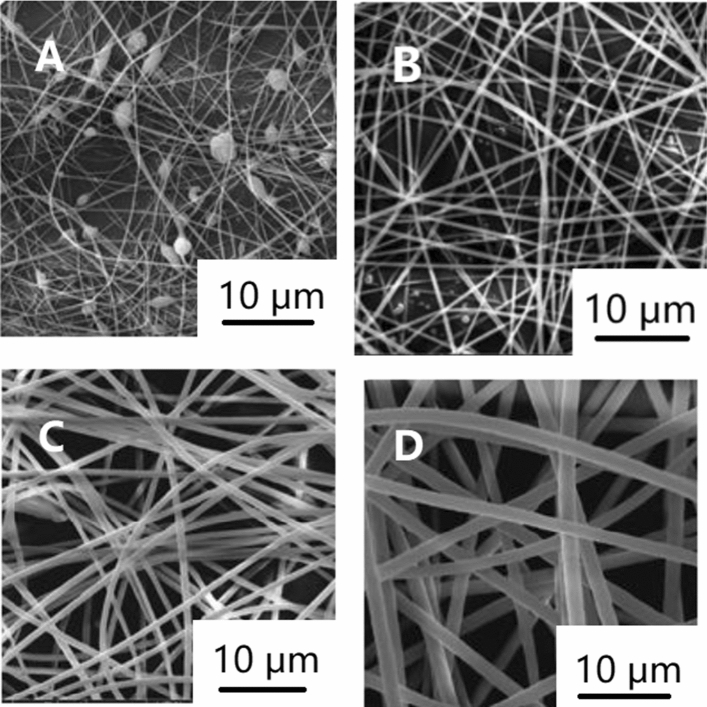

The concentration of the solution plays a decisive role in forming nanofibers. There is a minimum spinnability concentration. When the solution concentration is lower than this value, because of the low concentration and high surface tension, the interaction between the electric field force and surface tension will cause the entangled polymer to be disentangled before reaching the collection device [102, 103]. This produces many beads rather than fibers [104–106]. With the increase in the concentration and viscosity, the entanglement concentration of polymer increases and the surface tension decreases, resulting in more and more fibers, and finally, uniform and smooth nanofibers without beads are formed [107]. At this time, the concentration is the best. When the solution concentration is higher than the optimal concentration, the solution is easy to block the spinneret, resulting in coarse and uneven ribbon fiber [103, 108]. The optimal concentration is a range. As shown in Fig. 6, the nanofibers become coarser with the increase in the concentration in this range [105, 106, 109–111]. Some studies have also shown the solution viscosity can be improved by adding cosolvents at a certain polymer concentration. Increasing the concentration can usually improve the morphology of nanofibers or make it easier to electrospin polymers that are difficult. For example, sodium alginate can be electrospun into uniform and smooth nanofibers by adding glycerol or PEO [112, 113]. It has been found that if there are many kinds of polymers in the solution, even if the viscosity is the same, different polymer concentration ratio will change the diameter of nanofibers, which is caused by the interaction between polymers [113]. Some researchers have also changed the solution concentration and prepared microspheres instead of nanofibers by electrospinning, which provides a new idea [114].

Figure 6.

SEM images of electrospun polyimide nanofibers with different concentrations a 10%, b 15% c 20% d 25% [105].

Reproduced with permission from reference [105]. Copyright 2017, De Gruyter

Viscosity

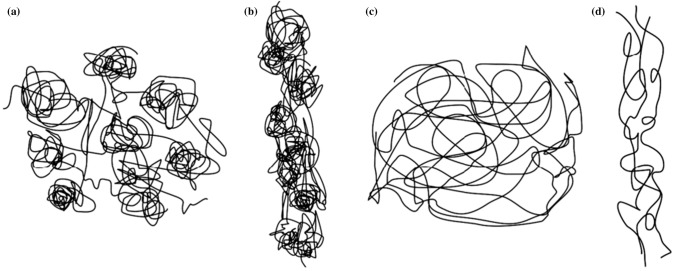

The viscosity of the solution is closely related to the concentration and molecular weight, which is one of the main parameters affecting the diameter and morphology of nanofibers [115]. If the viscosity is too low or too high, the bead structure will be formed [75]. If the viscosity is too low, it means the polymer entanglement is low and the surface tension is dominant, the droplets cannot connect into fibers and form spray [116]. With the increase in the viscosity, the stress relaxation time of the polymer becomes longer, which is conducive to forming nanofibers with larger and uniform diameter, as shown in Fig. 7 [117]. However, when the viscosity is too high, it is difficult for jets to form fiber [118]. Therefore, there is a best range of viscosity suitable for electrospinning nanofibers [102]. Some studies have shown the solution with viscosity of 1–20 P and surface tension of 35–55 dyn/cm2 is suitable for electrospinning nanofibers [119]. When the solution viscosity is too high to carry out electrospinning, some researchers propose using vibration technology to solve this problem [120]. For example, ultrasonic vibration can decrease the van der Waals force between polymer chains to achieve the purpose of temporarily reducing the viscosity of the solution, as shown in Fig. 8. At the same time, attention should be paid to avoid the rapid evaporation of the solvent during the vibration process [121]. The viscosity of the solution can be controlled by adjusting the polymer concentration. The viscosity of the solution can be increased with the increase in the solubility when the conductivity is high, but the change of the diameter of the nanofiber can be ignored, because the conductivity will also increase with the increase in the concentration. The increase in the conductivity will cause the diameter of the nanofiber to become smaller [110]. The solution concentration can also be increased by adding nanoparticles to the solution. Although the diameter of the nanofibers increases with the increase in the content of nanoparticles, the nanofibers will be rougher and more uneven because of the increase in the friction and viscosity between particles [122].

Figure 7.

Morphology of nanofibers with increasing viscosity a–d schematic diagram [123] and e–h SEM images of electrospun PEO nanofibers [104].

Reproduced with permission from reference [104]. Copyright 1999, Elsevier B.V. Reproduced with permission from reference [123]. Copyright 2013, MDPI (Basel, Switzerland)

Figure 8.

Influence of ultrasonic vibration on polymer molecular chain. a Entangled molecular chains in polymer solution without sonic vibration treatment, b entangled molecular chains in electrospun fiber without sonic vibration treatment, c molecular chains in polymer solution disentangled after sonic vibration treatment and d disentangled molecular chains in electrospun fiber with sonic vibration treatment [121].

Reproduced with permission from reference [121]. Copyright 2019, SAGE Publications Ltd

Molecular weight

The molecular weight of the polymer can affect the rheological and electrical properties of the solution such as viscosity, surface tension and conductivity [124]. When the molecular weight is large, the intermolecular force is large, and the polymer may also generate more hydrogen bonds between the solvents, making the polymer expand, thus increasing the viscosity value [125, 126]. Because of the inhomogeneity of polymer conductive system, the interchain conductivity is much lower than intrachain, and the larger the molecular weight, the smaller the degree of interchain discontinuity, the larger the interchain conductivity, and the larger the macroscopic conductivity [127–129]. However, some experiments have found the molecular weight has little relationship with the conductivity [130]. Similar to the effect of viscosity and concentration, the polymer with low molecular weight has insufficient entanglement degree, short chain length, small molecular friction force, difficult to resist unstable whipping, interrupted jet and difficult to form fibers [131]. In general, the diameter of nanofibers will also increase with the increase in the molecular weight. However, excessive molecular weight will produce ribbon fibers [132, 133]. Researchers have also found that intermolecular forces can be used to counter surface tension when the molecular weight is low [98].

Conductivity

The charged particles of polymer have great influence on jet formation. When the conductivity of the solution is too low, there will be beads and it is difficult to form uniform nanofibers. However, high conductivity may lead to bending whiplash and uneven diameter or formation of ribbon fibers [134]. The diameter of nanofibers decreases with the increase in the conductivity [113, 135]. Some researchers also found the conductivity has negligible effect on the fiber diameter [126]. It has been found that theoretically the jet radius is inversely proportional to the cube root of the solution conductivity [51]:

| 1 |

where r0 is jet or filament radius, Q is the mass flow rate, ε is the permittivity, σ is the electric conductivity, ρ is the density. The conductivity of the solution can be improved by adding some inorganic salts such as sodium chloride, lithium chloride, magnesium chloride and copper chloride to the solution. This helps forming beadless fibers with smaller diameters and increases uniformity [136]. Some researchers discovered the opposite [137]. Some organic compounds are also feasible, such as pyridinium formate [138], benzyl trialkylammonium chloride [139], dodecyltrimethyl ammonium bromide (DTAB) [140], tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBAC) [140], triethylbenzyl ammonium chloride (TEBAC) [141] and tetraethylammonium bromide (TEAB). However, their conclusions are not compatible. PH also affects the conductivity of the solution [106]. The electrospinning properties of polystyrene solutions with 18 kinds of common organic solvents were measured [142]. It was found that only 1,2-dichloroethane, DMF, ethylacetate, MEK and THF could meet the needs of electrospinning.

Surface tension

Surface tension is affected by many factors, including molecular weight, solution concentration, solvent type and temperature [126]. However, adding surfactant can also effectively decrease the surface tension, which only has to be removed in the subsequent process. When the surface tension is low, the beads are fewer and the nanofibers are finer and smoother [143, 144]. Some researchers believe the surface tension has little effect on the fiber diameter [145]. However, if the surface tension is too low, the jet will be unstable, the diameter distribution of nanofibers will be uneven [146] or even beads will be formed [147, 148]. In general, the surface tension of water is higher than that of ethanol. Ethanol can be added to the solution to decrease the surface tension [104]. A little surfactant can decrease the surface tension of the solution, such as sodium dodecyl benzene sulfonate (SDBS) [149], dodecyltrimethylammonium bromide (DTAB) [140], tetrabutylammonium chloride (TBAC) [140] and Tween 80 [110]. However, some surfactants, such as Triton X-405 [140], have little effect, and even more Triton X-100 (TX100) may increase the fiber diameter [150].

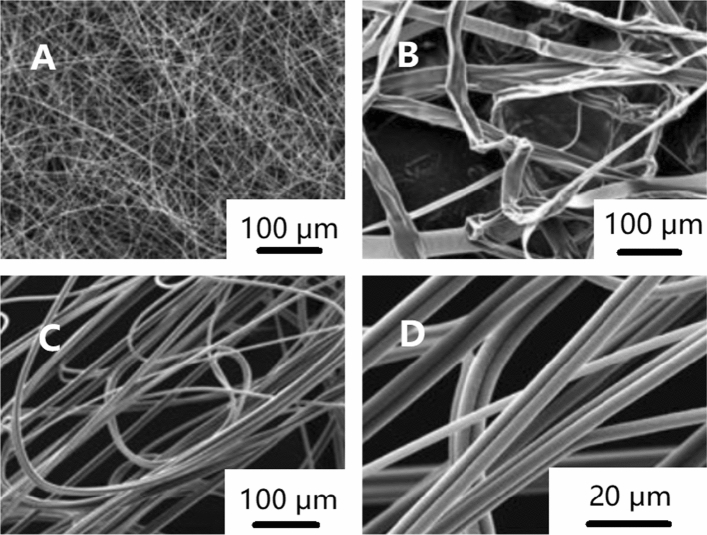

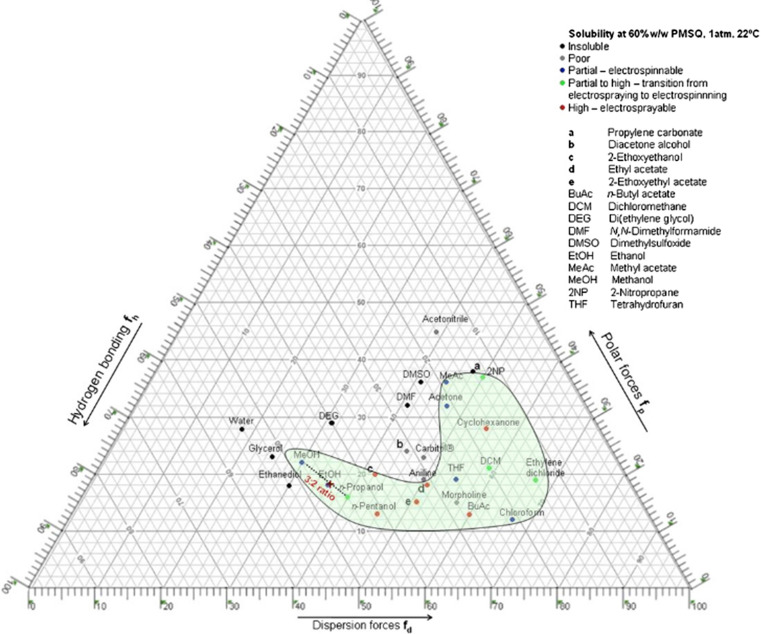

Solvent

There is no doubt the choice of solvent is important. The properties of the solvent, including surface tension, dielectric constant, boiling point, density, as well as the interaction between solvent and solute, as shown in Fig. 9, will affect electrospinning [145]. For example, the volatility of the solvent is directly related to whether it can volatilize before reaching the collection device, and has a great impact on whether beads will appear or not [151]. The polarity and dielectric constant of the solvent will affect the conductivity of the solution [151]. Because of the toxicity of many organic solvents, if they cannot be completely removed, they would not be used in biological and food fields [152]. The influence of solvent types on electrospinning is complex. There is no clear theory to judge whether electrospinning can be carried out with a certain solvent [153–155]. According to Hansen solubility parameters, a ternary solubility diagram has been made by some researchers, as shown in Fig. 10. The three edges represent the dispersion component (δd), polar component (δp) and hydrogen bonding component (δh), respectively, which can be used for in-depth study of solvent solubility [156–160]. The solvents in the green region is expected to dissolve the polymer. For example, when MeOH and PrOH are mixed, a good solvent such as EtOH can be found near their connecting line. The volume ratio of the two solvents can be calculated by the length ratio from the closest point to EtOH to both ends. The effects of solubility of polycaprolactone [161], polyethylene terephthalate (PET) [162] and polymethylsilsesquioxane (PMSQ) [159] in different solvents on electrospinning have been studied. When the solubility is low, it is easy to form nanofibers, and high dielectric constant will make the diameter of nanofibers smaller [159]. Kohse et al. [105] found the electrospinning of polyimide in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) produced smooth and round shaped nanofibers, but only ribbon shaped fibers were formed in 1,1,1,3,3,3-jexafluoro-2propanol (HFIP) and smooth but stucked fibers in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO).

Figure 9.

SEM of electrospun polyimide nanofibers in different solvents [105]. a DMF, b HFIP, c and d DMSO.

Reproduced with permission from reference [105]. Copyright 2017, De Gruyter

Figure 10.

Ternary solubility diagram of polymethylsilsesquioxane in different solvents. The solvent with good solubility is in the green region [159].

Reproduced with permission from reference [159]. Copyright 2010, Elsevier B.V

Processing parameters

Applied voltage

The applied voltage is also a key parameter in the electrospinning process. Only when the critical voltage is reached can the droplet be ejected and finally reach the collection device. The applied voltage also affects the morphology and diameter of nanofibers. If the applied voltage is too high or too low, it will lead to forming beads [163]. The diameter of nanofibers decreases with the increase in the applied voltage; because the electrostatic force is large, the droplets are stretched longer [164–169]. But in fact, according to previous studies, there is no consensus on the effect of applied voltage on nanofibers. Some researchers believe the diameter of nanofibers will increase with the increase in the voltage because of the increase in the jet velocity [170–172]. Kim et al. [173] also found the nanofibers first decreased and then increased with the increase in the applied voltage, and made some mechanical analysis. In addition, some researchers found that with the increase in the voltage, the diameter distribution of nanofibers is more uneven [168, 171]. The effect of applied voltage on the diameter of nanofibers may vary with the polymer solution concentration and the distance from jet device to collection device [174–176]. More research is needed on the effect of applied voltage on the diameter of nanofibers.

Flow rate

The flow rate also affects the diameter and morphology of nanofibers. The diameter of nanofibers increases with the increase in the flow rate [146, 168, 176, 177]. If the flow rate is too high, the solvent cannot completely evaporate before reaching the collection device, which will lead to forming beads [178] or ribbons [177]. Therefore, when the flow rate is moderate, the Taylor cone is more stable, and it is easier to generate smooth and uniform nanofibers [179]. Some researchers believe there is an ideal flow rate, and deviation from the optimal value will lead to the coarsening of nanofibers [180]. When the solution viscosity is low, the flow rate has little effect on the diameter of nanofibers [175, 176]. When the applied voltage is higher, the effect of flow rate is more significant.

Distance from jet device to collection device

The distance from jet device to collection device can also be used to control the diameter and morphology of electrospun nanofibers [181]. The distance from jet device to collection device needs to be large enough to allow the solvent to evaporate. If the distance is too small, there will be beads [177]. However, the distance should not be too large. If the distance is too large, the jet will not be stable enough, and there will be beads. In fact, the distance from jet device to collection device has less effect on the diameter of nanofibers than other parameters [170, 176, 182]. However, some researchers believe the distance has a great influence on the fiber diameter [183]. Generally speaking, the larger the distance, the greater the bending instability, resulting in the overlap of some nanofibers, resulting in larger fiber diameter [173, 184]. However, if the distance is small, the solvent evaporation time is not enough, and coarse nanofibers will be formed [116, 178, 185, 186].

Ambient parameters

Temperature

Generally speaking, the higher the temperature, the lower the viscosity and surface tension, the higher the solubility [147, 187, 188]. The increase in the temperature will lead to the decrease in the diameter of nanofibers and smoother surface [147, 187–189]. Yang et al. [189] studied the relationship between temperature and evaporation rate of PVP anhydrous ethanol solution using Knudsen layer theory. They found there was an inflection point in the relationship between temperature and nanofiber diameter, which was related to many properties of solution affected by temperature. However, De Vrieze et al. [147] also used the absolute ethanol solution of PVP and drew the opposite conclusion for the same temperature range.

Humidity

The influence of environmental humidity on electrospinning is also complex. When the humidity is low, the evaporation rate of solvent is faster, which will make the diameter of nanofibers larger [147, 190–193]. However, because of the different hydrophilicity of solvents, some organic solvents such as ethanol will absorb the moisture in the air, which makes the solvent more difficult to evaporate, and the electrostatic force is decreased, which makes the nanofibers thinner [147, 194]. Therefore, this should depend on the type and solubility of solvents [195]. Some researchers have also found there is no obvious relationship between ambient humidity and the thickness of nanofiber mats [106, 196, 197]. When the humidity is too high, the diameter distribution of nanofibers is more uneven, the surface is more rough, and the pores or fibers are less [106, 191, 197, 198]. Ding et al. [199] found that under the condition of high voltage and low humidity, the rapid separation of polymer and solvent can produce nanowebs with overlapping layers, uniform pore size and fine fiber.

Models and simulation

It is of great significance to simulate electrospinning by computer. Because the phenomena observed in many experiments are sometimes difficult to explain, we need to use theoretical models and computer simulation to help us better understand various problems. Although electrospinning technology has been widely concerned, there are few studies on simulation. In fact, because of the complex parameters affecting electrospinning, many researchers have put forward some empirical relationships. For example, Wang et al. [200, 201] obtained some empirical scaling laws of parameters and diameter through experiments, and Yousefi et al. [202] did some similar experiments. However, because of the lack of systematization and characterization, the applicability of the empirical model is limited [203]. By establishing a perfect mathematical and physical model for electrospinning simulation, the morphology and properties of nanofibers can be well predicted, which could improve the work efficiency of researchers and expand the electrospinning technology application.

Physical models

Models of electric field

Taylor [49] first studied the initial stage of the jet. In principle, when the electric field force and surface tension are equal, the viscous droplet will form a cone with the half vertex angle of 49.3° and the state is called the Rayleigh stability limit [28].

Taylor [48] gave the critical voltage of viscous fluid jet:

| 2 |

where Vk is the potential at breakdown, H is the distance between jet device and collection device, L is the injector length, R is the injector radius and T is the surface tension of the liquid.

Besides, they introduced the leaky dielectric model to explain the behavior of droplets deformed by a steady field, which laid the foundation for the later theoretical research.

Hendricks et al. [204] gave an empirical formula for the critical voltage of hemispheric suspension droplets:

| 3 |

where V is the critical voltage, γ is the surface tension, and a is the capillary radius.

Of course, Taylor's and Hendricks' studies assumed the droplet is in a stable state at the capillary port, and the model only applies to weakly conductive liquids, without considering the effects of liquid conductivity and viscosity.

Interestingly, Yarin et al. [205] confirmed theoretically and experimentally the half angle of Taylor cone should be 33.5° instead of 49.3°. This may be because of the existence of non-self-similar solutions for hyperboloid shape in equilibrium with its own electric field under the surface tension action.

Models of jet

When the applied voltage is higher than the critical voltage and the electric field force is greater than the surface tension, the jet will first go through the stable stage and then enter the unstable stage.

Stable stage

In the stable stage, the polymer jet does uniaxial stretching, and the jet shape does not change with time. In this process, the jet radius is the focus of research, because it directly affects the diameter of nanofibers.

Baumgarten [51] derived the jet radius from the relationship between transfer current and conduction current:

| 4 |

where r0 is jet or filament radius, Q is the mass flow rate, ε is the permittivity, σ is the electric conductivity and ρ is the density.

However, the axial voltage gradient in jet in units still needs to be obtained.

According to the equations of mass balance, electric charge balance and momentum balance, Spivak et al. [206, 207] established a simple one-dimensional model of nonlinear power-law fluid:

| 5 |

where z is the axial coordinate, R is the dimensionless jet radius, NW is the dimensionless Weber number, NE is the dimensionless parameter, NR is the effective Reynolds number and m is the flow index.

However, the one-dimensional linear symmetrical model is too simple, which is different from the actual.

Later, according to the leaky dielectric model and the slender body theory, Hohman et al. [208, 209] introduced the free charge and obtained the approximate model of jet dynamics:

| 6 |

where h is the radius of jet, v is the fluid velocity parallel to axis of jet, σ is the surface charge density, K* is the dimensionless conductivity, E is the electric field parallel to axis of jet, , ν* is the dimensionless viscosity, Χ is the aspect ratio and Ω0 is the dimensionless external field strength.

However, this model is not suitable for non-Newtonian fluid. After that, Feng [210] improved it and considered the non-Newtonian fluid:

| 7 |

where v is the axial velocity, Pe is the Electric Peclet number, Fr is the Froude number, Re is the Reynolds number, η is the viscosity, E is the axial field, z is the axial position, We is the Weber number, , is the dielectric constant of the ambient air, , Χ is the aspect ratio and E∞ is the external field.

Unstable Stage

The unstable stage is much more complicated than the stable stage, and researchers have made great efforts. The instability is caused by the charge repulsion in the jet. There are three kinds of instability in the unstable stage of electrospinning [211]: the classical Rayleigh mode (axisymmetric) instability, electric field-induced axisymmetric conducting mode (bending) instability and whipping conducting mode instabilities. These instabilities change with the applied voltage, the distance from jet device to collection device and the solution parameters, which affect the morphology and distribution of nanofibers [212].

Strutt and Rayleigh [26] first proposed and found the axisymmetric instability, and derived the relationship between the instability deviation distance and the potential and other factors. Unfortunately, there is no effective experimental support.

Huebner and Chu [213] analyzed the influence of surface tension and electrodynamic effect on jet radius on the basis of empirical formula, but also lacked experimental support.

Reneker et al. [214] established a three-point-like charges model and analyzed the cause of the bending instability:

| 8 |

where m is the mass, δ is the distance, l is the length and e is the charge.

They also proposed a viscoelastic model of a rectilinear electrified liquid jet. The linear Maxwell equations were used to describe the jet flow. The spinning process was simplified as a system of beads:

| 9 |

where σ is the stress, t is the time, l is the length, G is the elastic modulus, μ is the viscosity, , m is the mass, e is the charge, , V0 is the voltage, h is the distance from pendent drop to grounded collector, a is the radius and ki is the jet curvature.

| 10 |

According to Yarin et al. [215], the main cause of instability is the electric bending force, and the wave number Χ* and the growth rate γ of the fastest growing bending perturbation are derived:

| 11 |

| 12 |

where ρ is the density, a0 is the jet cross-sectional radius which does not change for small perturbations, μ is the viscosity, L is the cutoff length, a is the cross-sectional radius of the jet element and σ is the surface tension.

Hohman et al. [208, 209] developed the slender body theory and established a jet dynamic model to clarify the influence of the surrounding electric field on the jet charge:

| 13 |

where X is the oscillation of the centerline, s is the arc length, ν* is the dimensionless viscosity, is the air dielectric constant, , Ω0 is the dimensionless external field strength, P is the dipole density, σ0 is the dimensionless background free charge density, R is the radius, σD is the dipolar component of free charge density, Χ is the aspect ratio and ξ is the coordinate in the principal normal direction.

Shin et al. [216] also proposed the whipping instability model and gave the amplification factor for a perturbation convected a distance downstream:

| 14 |

where Γ is the amplification factor, E∞ is the applied electric field, Q is the flow rate, A is the amplitude of a perturbation, d is the distance, ω is the growth rates, E is the local electric field, h is the radius of the jet and σ is the surface charge distribution.

After that, Fridrikh et al. [217] established a mathematical model of the influence of parameters and obtained the equation of motion of the jet:

| 15 |

where ρ is the density, h is the jet diameter, x is the motion for normal displacements of the centerline of the jet, E∞ is the applied electric field, is the unit vectors normal to the centerline of the jet, γ is the surface tension, is the dielectric constant, is the unit vectors tangential to the centerline of the jet, Χ is the dimensionless wavelength of the instability responsible for the normal displacements and R is the radius of curvature.

Theron et al. [218] studied the parameters of electrospinning with the help of empirical formulas.

Carroll et al. [219] calculated the expected growth rate of the axisymmetric beads, as well as the expected bead wave number, and analyzed the instability mechanism from the perspective of energy. They found that electrical forces mainly drive the unstable axisymmetric mode for electrically driven, highly conducting jets:

| 16 |

where , , , , , , , , , , , , , , .

Using JETSPIN software package, Carroll and Joo [219] studied the effect of gas flow on electrospinning by using nonlinear Langevin-like approach and made experimental comparison:

| 17 |

where σi is the stress on the ith dumbbell which connects the bead i with the bead i + 1, li is the length of the element, G is the elastic modulus, μ is the viscosity of the fluid jet, t is the time, vi is the velocity of the ith bead, fel,i is the electric force, fc,i is the net coulomb force, fve,i is the viscoelastic force, fst,i is the force due to the surface tension, fg,i is the force due to the gravity, fdiss,i is the dissipative force, frand is the random force and ri is the position vector of the ith bead.

Yousefi et al. [220] used a physics-based computational model, mass–springdamper (MSD) approach to incorporate the mechanical properties of the fibers in predicting the formation and morphology of the electrospun fibers:

| 18 |

where ri is the position vector of bead i, mi is the mass of bead i, , , is the viscoelastic forces acting on bead i, is the surface tension force, is the electric attraction force and is the Columbic force.

Molecular simulation

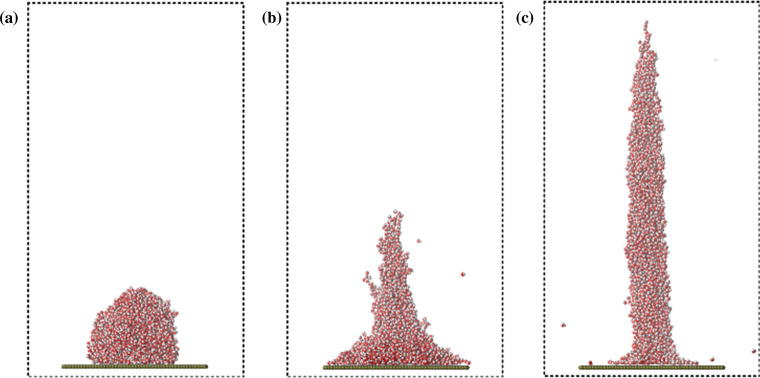

Molecular simulation technology includes Monte Carlo method and molecular dynamics method [83, 221]. Monte Carlo method is based on statistics and is suitable for equilibrium system. Molecular dynamics method is a deterministic method based on classical mechanics, which can solve the equations of motion of all particles in the system, and is suitable for studying time-dependent phenomena. In electrospinning, molecular dynamics method is commonly used to study the interaction of composite materials and the adsorption or surface interaction of nanofiber products with drugs or proteins. Jirsák et al. [222] used Monte Carlo method and molecular dynamics method to simulate the initial stage of the jet, as shown in Fig. 11. The results obtained by the two methods are qualitatively consistent with the experimental results and found the balance of ion concentration and field strength affects forming beads in nanofibers. Danwanichakul et al. [223] used Monte Carlo method to simulate the deposition stage of nanofibers, obtained the positive correlation between the concentration and the pore size of the fibers, and tested the filtration performance of polystyrene particles, which was consistent with the experimental results. Sarmadi et al. [224] simulated the protein adsorption capacity of electrospun PCL/PVA nanofibers by molecular dynamics method, which was consistent with the experimental results. In addition, Vao-soongnern [225] analyzed the effect of molecular weight and chain conformation of polymers on the structure and properties of electrospun nanofibers using Monte Carlo method. Steffens et al. [226] simulated the interaction between PVA nanofibers and drug-loaded dacarbazine using quantum mechanics calculations, molecular modeling techniques and molecular dynamics simulation, thus explaining the principle of controlled drug release.

Figure 11.

Sequence of snapshots showing the transformation of a droplet on the wall modeling the apex of the Taylor cone to a jet. a System before the field was applied, b the instant soon after the field was applied, and c a later instant when the droplet is transformed to the jet. Colored spheres represent atoms and ions as follows: red–oxygen, white–hydrogen, blue–sodium cation and cyan–chloride anion [222].

Reproduced with permission from reference [222]. Copyright 2014, American chemical society

Others

As well as the above models and simulation methods, there are some other interesting methods. For example, lattice Boltzmann method, which is an advanced computational fluid dynamics method, has the characteristics of mesoscopic model between micro-molecular dynamics model and macro-continuous model. Karra [227] modified the discrete bead model and proposed a hybrid numerical scheme that couples lattice Boltzmann method with the finite difference method to solve Oldroyd-B viscoelastic problem. Finite element model is equally a commonly used model in physics. Yin et al. [228] used representative volume element to analyze the relationship between the nanofiber membrane performance and single nanofiber performance, and verified the correctness of the conclusion through experiments. Neural network is a hot machine learning algorithm recently, but its application in electrospinning is still less. Sarkar et al. [229] used neural network algorithm, taking concentration, conductivity, flow rate and electric field strength as input variables, can well predict the change of fiber diameter, but only consider the influence of four variables, which is not suitable for complex electrospinning process.

Applications

Biomedicine

Tissue engineering

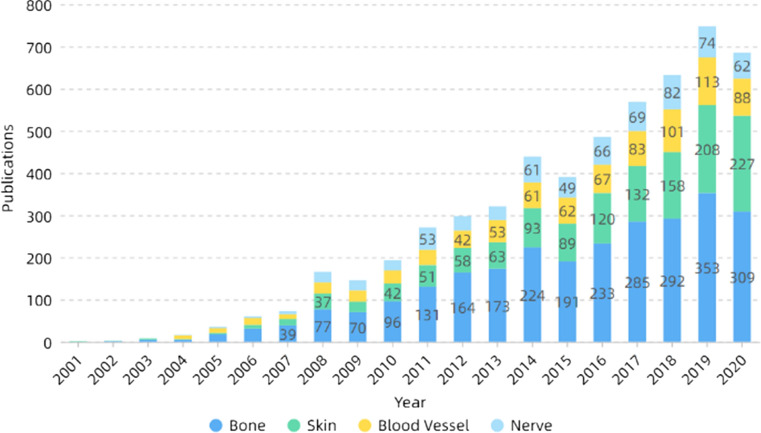

Tissue engineering is a major branch of biomedical engineering, whose main purpose is the repair and regeneration of organs or tissues [230–233]. Tissue engineering consists of three parts: scaffold materials, growth factors and cells. The nanofibers prepared by electrospinning have the characteristics of high porosity and large specific surface area, which are similar to the structure of extracellular matrix (ECM). They can provide sites for cell adhesion and facilitate the transport of nutrients and wastes [234–236]. Besides, the electrospinning parameters are mostly controllable, which can prepare nanofibers with ideal diameters and shapes, as well as nanoparticles or nanotubes and other structures, and have a wide application prospect in tissue engineering [214, 237, 238]. Figure 12 shows the number of publications on electrospinning in different directions of tissue engineering. It can be seen that researchers mainly focus on bones and skin, and less on blood vessels and nerves.

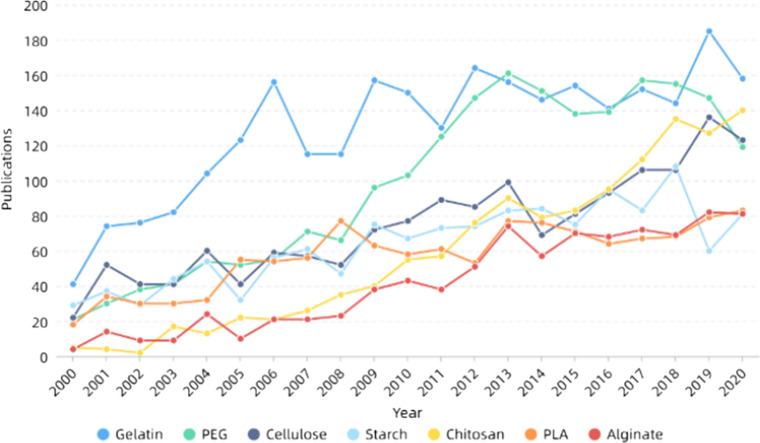

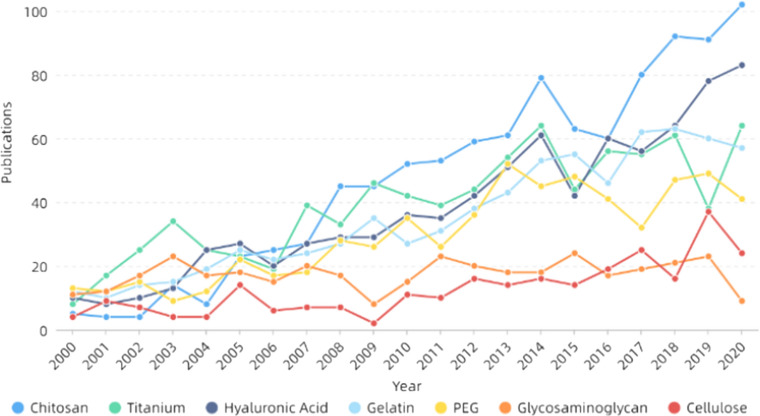

Figure 12.

Number of publications on electrospinning in different directions of tissue engineering. All the data used are from Web of Science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Bones

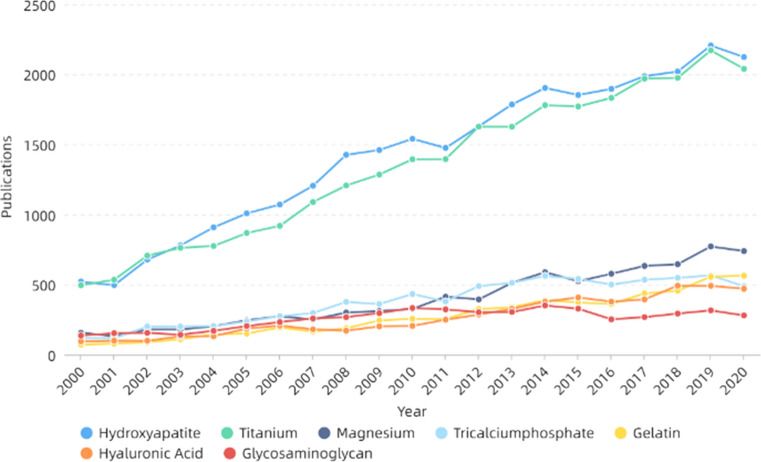

Bone is a complex nanocomposite comprising about 70% hydroxyapatite (HAP) and about 30% collagen fibers [239, 240]. When human bones are damaged by disease or accident, tissue engineering techniques can be utilized to repair or regenerate them. Electrospinning technology has great potential in bone repair [241, 242]. Bone repair materials can fall into three categories: metal, polymer and ceramic. Figure 13 and Table 1 both show that hydroxyapatite and titanium-related materials are widely used in bone repair, which are the two most important bone repair materials in metal and ceramics. Metal materials have excellent biocompatibility and mechanical properties, but they are generally non-biodegradable and have less effect on surrounding tissues. Polymers and ceramics have good biological activity, some with good mechanical properties are more suitable for bone tissue engineering [243]. Hydroxyapatite (HA), the main inorganic component of human bones, has good biocompatibility and is suitable for use as a bone repair material [244, 245]. Besides, HA can also promote growth and proliferation of osteoblasts and induce bone mineralization [246]. However, its mechanical properties are poor, brittle and easy to break, so it needs to be modified or compounded with other materials. In recent years, preparing hydroxyapatite-related materials by electrospinning has been widely studied. Many studies have shown that hydroxyapatite can be combined with gelatin [247], collagen [248], silk [249], PCL [250], chitosan [251] and so on, making it more suitable for bone repair. For example, Chen et al. [252] prepared gelatin–chitosan core–shell structure nanofibers using coaxial electrospinning technology. Hydroxyapatite was wet deposited on the surface of the fibers, which was conducive to the adhesion and proliferation of osteocytes, improved mineralization efficiency of hydroxyapatite, then cultured MG-63 cells for evaluation. It was noted the cell activity was significantly improved, indicating that its biocompatibility was good. Ko et al. [253] coated glycidoxypropyltrimethoxysilane (GPTMS) on the surface of hydroxyapatite to improve the dispersion in silk fibroin solution and added PEO to improve the stability of electrospinning. After electrospinning, polydopamine (PDA) and hydroxyapatite nanoparticles were coated on the surface, and a new nanofibrous scaffold material was obtained. Tests showed the coating improved the compressive resistance of the material. Then the human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (hADMSCs) activated by TAZ transcription regulator were cultured on the scaffold material, which further improved the osteoconductivity of the material, developed osteogenic ability of the cells and promoted the formation of bone. At the same time, it was found the concentration of hydroxyapatite had a great impact on the osteogenic ability, and its importance is self-evident. Using hydroxyapatite–TSF composite nanoparticles as the inner layer and pure tussah fibroin as the outer layer, Shao et al. [254] prepared nanofibers with different core–shell mass ratio using coaxial electrospinning technology, which was conducive to the proliferation and adhesion of MG-63 cells. Alkaline phosphatase, osteocalcin and matrix mineralization at different times were also measured, indicating the materials made bone development and maturation faster.

Figure 13.

Number of publications of some bone repair materials in recent years. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Table 1.

Some progress of electrospinning in bones in recent years

| Material | Solvent | Flow rate (mL/h) | Distance (cm) | Voltage (kV) | Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan/PEO/halloysites | Water | 1.2 | 15 | 19–26 | NHOst | [255] |

| PHB/keratin | Chloroform/DMF | 0.96 | 25 | 13 | MG-63 | [256] |

| PLGA/β-TCP particles | DCE/DMF | 1 | 25 | 18 | MC3T3 | [257] |

| Chitosan/PHB/alumina nanowires | TFA | 0.6 | 25 | 22 | MG-63 | [258] |

| PCL/nanomagnesium phosphate/nanohydroxyapatite/hyperbranched polyglycerol | DMF/CHCl3 | 0.5 | 11 | 9–13 | MG-63/hMSCs | [259] |

| Deacetylated cellulose acetate | Acetone/water | 2–4 | 12–15 | 20–22 | MC3T3 | [260] |

| Zein/trimethylolpropane triglycidyl ether (TMPGE) | Ethanol/water | 2.5 | 25 | 17–20 | MC3T3 | [261] |

| silk fibroin/PLCL/parathyroid hormone | HFIP | 1 | 12/15 | 12/15 | BMMSCs | [262] |

| PCL/amine-functionalized single-walled carbon nanotube | DCM/DMF | 2 | 23 | 17 | rMSCs | [263] |

| PHB/PCL/levofloxacin/sol–gel derived silica | Chloroform/DMF | 4 | 15 | 15 | MG-63 | [264] |

| PCL/chitosan or carboxymethyl chitosan | Acetic acid/formic acid | 0.1–0.7 | 16–20 | 18–30 | MG-63 | [265] |

| PCL/F18 bioactive glass | DCM/DMF | 3 | 18 | 17 | MG-63 | [266] |

| PLLA/synthetic glass-reinforced hydroxyapatite | DMC/DMF | 0.5 | 20 | 25 | MG-63 | [267] |

| PLLA/glass-reinforced hydroxyapatite microparticles | DMF/dichloromethane/DCM | 0.5 | 20 | 25 | MG-63 | [268] |

| PCL/gelatin | TFE/acetic acid/ethanol | 3 | 18 | 20 | MC3T3 | [269] |

| Cellulose/nanohydroxyapatite | LiCl/DMAc | 0.24 | 10 | 20 | HDFCs | [270] |

| Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)/silicate containing hydroxyapatite nanoparticles | Chloroform | 2 | 5 | 7 | hMSCs | [271] |

| Polyamide-6,6/chitosan | Acetic acid/HFIP | 0.5 | 17 | 20 | MC3T3 | [272] |

| PHB/hydroxyapatite nanoparticles | Chloroform | 1 | 20 | 15 | MSCs | [273] |

| Zein/calcium lactate/PCL | DMF/DCM | 1 | 18 | 17 | MC3T3 | [274] |

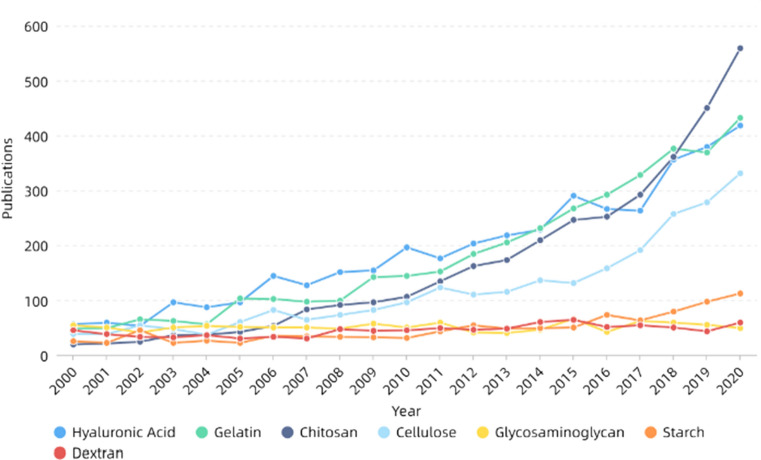

Skin

Skin is the largest organ of the human body, the first defense line of the matrix from dehydration, injury and infection, and a barrier to prevent from invading external microorganisms. The main functions are protection, sensation, regulation of body temperature, absorption, secretion and excretion, respiration, metabolism and so on [275, 276]. Skin tissue engineering is one of the most important components in skin repair. Ideal skin repair materials should have good biocompatibility, degradability, mechanical properties and so on and need to ensure the transport of gases and nutrients and prevent bacterial infections as well as the loss of body fluids and proteins [276, 277]. Electrospinning can prepare nanofibers with similar structure to extracellular matrix, which have the advantages of controllable pore size, large specific surface area and good permeability. It is conducive to cell attachment, proliferation and differentiation and is suitable for skin repair [278–281]. Table 2 and Fig. 14 show that gelatin, hyaluronic acid and cellulose are of high concern in skin repair. Gelatin, derived from partial hydrolysis of collagen, is one of the commonly used natural polymers. Its low molecular weight can make electrospinning more stable and the nanofibers have smoother and uniform morphology. It also has many binding sites that are beneficial to cell adhesion, proliferation and differentiation [282, 283]. However, its poor mechanical properties limit its application in skin repair and even tissue engineering. In recent years, researchers have combined gelatin with keratin [284], PCL [285], PHB [286], PU [287] and so on to improve the mechanical properties of the materials, which has a wider application in skin repair. For example, Baghersad et al. [288] prepared gelatin/aloe vera/PCL composite scaffolds using double-nozzle electrospinning technology, studied the effect of parameters on the performance and morphology of nanofibers. They found the materials had high antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, while improving the cell activity of NIH 3T3 fibroblast cells. In addition, Adeli-Sardou et al. [285] prepared nanofibers using coaxial electrospinning with PCL as shell polymer and gelatin–lawsone blend as core polymer, and found that they could significantly improve the biological activity of human gingiva fibroblast cells (HGF) and promote cell adhesion and proliferation. Then the in vitro gene expression of transforming growth factor β (TGF-B1), collagen (COL1) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) was monitored using RT-qPCR technique, and it was believed the material could effectively promote the regeneration of skin tissue. Shi et al. [289] prepared nanofiber membranes by mixing trimethoxysilylpropyl octadecyldimethyl ammonium chloride (QAS) with PCL/gelatin solution, and phase separation occurred. The nanofibers were mainly PCL inside and gelatin outside. The materials had broad-spectrum bactericidal effect and had no toxic side effects to L929 cells. They were suitable for use as skin antimicrobial materials.

Table 2.

Some progress of electrospinning in skin in recent years

| Material | Solvent | Flow rate (mL/h) | Distance (cm) | Voltage (kV) | Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silk fibroin/PCL/PEO | Formic acid/TFE | 1/2.3 | 10–12 | 28 | NHDF | [290] |

| PCL/chitosan/PEO/aloe vera extract/keratin | Formic acid/acetic acid | 0.1 | 10–12 | 15/16 | L929 | [291] |

| PCL/gelatin/MgO particles | HFIP | 2 | 22 | 24 | hEnSCs | [292] |

| Chitosan/PVA/glyoxal/halloysite nanotubes | Acetic acid | 0.2 | 6 | 15 | Human normal fibroblast cells | [293] |

| Silk fibroin/PCL/PEO | Formic acid | 0.3 | 12 | 17.5 | Human BJ fibroblast cells | [294] |

| PCL/Althea Officinalis Extract/gelatin | Formic acid/acetic acid | 0.3 | 10 | 15–17 | L929 | [295] |

| PCL/N-(2-hydroxy)-propyl-3-trimethylammonium chitosan chloride | Formic acid/acetic acid | 0.9 | 15 | 25 | HDFn | [296] |

| PCL/chitosan/hyaluronic acid/PEO | Formic/acetone | 1.2/1/0.1 | 15/18/10 | 16/18–20/11 | Vero cells | [297] |

| PCL/zein/gum arabic | Formic acid/acetic acid | 0.2 | 15 | 18 | L929 | [298] |

| PEO/casein/silver nanoparticles | SDS | 0.3 | 15 | 20 | NIH-3T3 | [59] |

| Cellulose acetate/gelatin/nanohydroxyapatite | HFP | 0.8 | 13 | 18 | L929 | [299] |

| PCL/Maillard reaction products/glucose–arginine or fructosearginine | TFE | 2.5 | 14 | 25 | NHDF | [300] |

| PDLLA/PCL/Cu2S nanoparticles | DMF/THF | 0.9 | 15 | 8–12 | HDFs/HUVECs/murine B16F10 melanoma cells/human A375 melanoma | [301] |

| Chitosan/PEO/henna leaves extract | Acetic acid | 0.1–1.5 | 10–20 | 5–25 | NHF | [302] |

| Gelatin/PVA/keratin | Formic acid | 0.1 | 10 | 20 | L929 | [284] |

| PLA/hyperbranched polyglycerol/curcumin | Chloroform/methanol | 0.5 | 12 | 13–15 | 3T3 | [303] |

| Gelatin/sulfated hyaluronan/chondroitin sulfate | TFE | 0.75 | 13 | 20 | HaCaT/Hs27/hMSCs | [304] |

| PCL/chitosan | Chloroform/methanol/acetic acid | 0.18 | 10 | 22 | Human fibroblast/keratinocyte | [305] |

| PCL/cellulose acetate/chitosan/PEO | Chloroform/methanol/acetic acid | 2 | 15 | 20/25 | L929 | [306] |

| Gelatin/TEA/BDDGE | Acetic acid | 0.4 | 12 | 11 | hDNF | [307] |

| PCL/chitosan/PEO/aloe vera | TFE | 2.5/4 | 15/12 | 25/28 | NHDF | [308] |

| PLGA | DMF/THF | 0.8 | 15 | 28 | HDF/HaCat | [309] |

| Silk fibroin/PEO/NaCl | Water | 1.2 | 15 | 22 | HDF/HaCAT | [310] |

| Chitosan/bacterial cellulose/PEO/nanodiamond | Acetic acid | 0.3 | 10 | 20–22 | L929 | [311] |

| Cellulose acetate | Acetone/NaOH | 5 | 20 | 15 | L929 | [312] |

| PEUU/gelatin | HFIP | 1.5 | 15 | 12.5 | L929 | [313] |

| PHB/gelatin | HFIP | 1.5 | 12 | 18 | NIH 3T3/HaCaT | [286] |

| Silk fibroin/PEO/gold nanoparticle | Water | 0.8–2 | 13–23 | 12–19 | L929 | [314] |

| PLGA/collagen | HFIP | 1 | 17 | 28 | HDF/HaCat | [315] |

Figure 14.

Number of publications of some skin repair materials. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Blood vessels

In recent years, cardiovascular disease has been the leading cause of death among non-communicable diseases. Atherosclerosis is one of the main causes of cardiovascular diseases [316]. The arteries are mainly composed of three layers: the tunica intima, the tunica media and the tunica adventitia. Among them, the tunica intima is the main part of vascular repair materials [317]. Electrospinning has been extensively used in vascular repair because of its controllable diameter and porosity of the prepared nanofibers [317–319]. Besides biocompatibility and mechanical properties, vascular repair materials also need to prevent thrombosis and vascular calcification [320, 321]. Some recent progress in electrospinning of blood vessels are listed in Table 3. It can be seen from Fig. 15 that the heat of gelatin in vascular repair has remained high, while PEG has been on the top in recent years and received extensive attention. PEG is a synthetic polymer with good biocompatibility. However, their biodegradability and mechanical strength are not ideal [322, 323]. But relative to blood vessels, PEG has excellent hemocompatibility, can inhibit hemolysis and has a certain anticoagulant capacity, can inhibit thrombosis, so it is suitable for use as a vascular repair material [324–327]. Yin et al. [328] used PEGylated chitosan and PLCL mixed solution as the inner layer and PLCL/PEG as the outer layer, and prepared nanofiber materials by coaxial electrospinning technology. They found the mechanical properties were good, the strength was higher than that of human blood vessels, the compliance was close to human blood vessels, and the degradation rate was appropriate. The patency of the material was studied by femoral artery replacement model, and the positive endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells grew well, with high levels of related protein expression and good calcification, and are suitable for vascular repair.

Table 3.

Some progress of electrospinning in blood vessels in recent years

| Material | Solvent | Flow rate (mL/h) | Distance (cm) | Voltage (kV) | Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVA/alginate or chitosan | Acetic acid/DMSO | 4 | 8 | 8 | HMEC-1 | [329] |

| PCL/Pluronic P123/cilostazol | Chloroform/methanol | 2 | 15 | 10 | HUVECs/PASM | [330] |

| PU/gelatin/single-walled carbon nanotube | HFIP | 0.3 | 12 | 18 | myocardial myoblast/endothelial cells | [331] |

| PU/cedarwood oil/cobalt nitrate | DMF | 0.3 | 20 | 11 | HDF | [332] |

| PCL/PLCL | chloroform/ethanol/acetic acid | 1.5 | 20 | 15 | 3T3 | [333] |

| PCL/gelatin/cysteine-terminated REDV peptide | TFE/acetic acid | 0.4 | 15 | 10 | VEC/L929 | [334] |

| Acrylamide-terminated glycine–arginine–glycine–aspartic peptides modified PEUU | HFIP | 0.5–1 | 14 | 8.45–10 | HUVECs | [335] |

| Zinc oxide nanoparticles/poly(vinylidene fluoride-trifluoroethylene) | Acetone | 1.5 | 10 | 18 | hMSCs | [336] |

| PCU | DMF/THF | 1.5 | 13 | 16 | MEF | [337] |

| PCL/PU | THF/DMF/MEK | 1.1 | 20 | 15 | EA.hy926 | [338] |

| PCL/europium hydroxide nanorods | chloroform/methanol | 1 | 15 | 18 | HUVECs/EA.hy926 | [339] |

| PET | TFA/DCM | 1.5 | 15 | 18 | 3T3 | [340] |

| PU/PEG or PC | THF/DMF | 0.01 | 15 | 22–23 | HUVECs | [341] |

| PCL/gelatin | TFE/acetic acid | 1 | 20 | 20 | hMSCs | [342] |

| PU/PEG/cerium oxide nanoparticles/VEGF | THF/DMF | 0.8–1 | 10–15 | 8–10 | EPCs | [343] |

Figure 15.

Number of publications of some blood vessel repair materials. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Nerves

Neural repair is an important component of tissue engineering, which is closely related to everyone's life [344–346]. The directionally aligned nanofibers prepared by electrospinning technology are conducive to the growth of nerve cells [347] and may have a good effect on cell synapses, which can be well applied in nerve tissue repair. Besides orientation, both morphology and surface coating of nanofibers affect nerve regeneration [348–350]. Some recent progress in electrospinning of nerves is listed in Table 4. Figure 16 shows that there are many kinds of nerve repair materials without obvious concentration, among which chitosan and cellulose have become the hot spots in recent years. Interestingly, these two materials are the two most abundant polymers in nature [351, 352]. Cellulose is a natural polymer produced by photosynthesis and is the most abundant polymer in nature. It can be converted into many derivatives, such as cellulose esters and cellulose ethers, which have good biocompatibility [353–355], and have better mechanical properties of other natural polymers [356], which are suitable for nerve conduit materials. Hou et al. [357] prepared PLGA outer conduit by electrospinning technology to bridge the sciatic nerve and then prepared oxidized bacterial cellulose-collagen sponge fillers by freeze-drying technology to facilitate nerve regeneration across the injured nerve gap. When combined into nerve conduit, it can increase the efficiency of gap bridge rebuilding and effectively promote the functional restoration of gastrocnemius muscle. Farzamfar et al. [358] mixed gelatin and cellulose for electrospinning and added gabapentin, a drug that can promote nerve remyelination, and found that it can improve the activity of Schwann cells and promote their proliferation. The regeneration effect of sciatic nerve was indirectly evaluated using rat gastrocnemius muscles and found the material can improve the regeneration ability of the injured site. However, the porosity of this material does not meet the requirements of ideal scaffolds.

Table 4.

Some progress of electrospinning in nerves in recent years

| Material | Solvent | Flow rate (mL/h) | Distance (cm) | Voltage (kV) | Cells | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLGA/Nimodipine | THF/DMF | 0.5–1 | 10–15 | 4.5–9 | SW10/RN33B/C8-D1A | [359] |

| PLLA | Chloroform | 2.08 | 5 | 15 | Dorsal root ganglia | [360] |

| PVA/poly(glycerol sebacate)/Kraft lignin nanoparticle | Water/DMF | 0.5 | 30 | 19 | PC12 | [361] |

| PDLLA/β-TCP/collagen | DCM/ethyl acetate | 0.8 | 15 | 3 | RSC96 | [362] |

| PCL | Methanol/chloroform | 5 | 20 | 12 | Schwann cells/dorsal root ganglions | [363] |

| PGS/PLLA | DMF/DCM | 0.5 | 15 | 25 | A59 | [364] |

| PLLA/NGF/VEGF | Dichloromethane/span-80/methanol/water | 0.8 | 12 | 16 | iPSCs-NCSCs | [365] |

| PLA/cellulose acetate | 1, 4-dioxane/acetone | 1 | 10 | 18 | Schwann cells | [366] |

| PCU | DMF/THF | 1 | 15 | 20 | DPSCs | [367] |

| PCL/collagen/nano bioglass | Acetic acid | 1 | 8 | 15–18 | hEnSCs | [368] |

| PVDF/gold colloidal nanoparticles | DMAC/acetone | 0.5 | 18 | 15 | PC-12 | [369] |

| Silk fibroin/PEO | Water | 1.2 | 14 | 12 | Schwann cells | [370] |

| PLLA/gum tragacanth | HFP | 1 | 14 | 13 | PC12 | [371] |

| PGS-poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate copolymers | HFP | 1 | 15 | 10 | PC12 | [372] |

| PS | THF/DMF | 0.2 | 4–5 | 5–14 | U373 | [373] |

| PELA-PPY | Trifluoroethanol | 1 | 15 | 20 | PC-12 | [374] |

Figure 16.

Number of publications of some nerve repair materials. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Drug delivery

Drug delivery refers to the use of carriers to transport drugs or biomolecules to certain areas, controllably release drugs and improve regional drug concentration [375–377]. Nanofibers have many advantages, such as large specific surface area, high drug loading, high porosity, high mechanical strength, easy surface modification and functionalization, and have been widely used to treat various diseases [378–380]. The diameter, porosity and drug binding mechanism of nanofibers all affect the drug release rate [102, 381–383]. There are two main methods, hybrid electrospinning and coaxial electrospinning, to combine drugs, as shown in Table 5 [384, 385]. As shown Fig. 17, PEG and chitosan are the main materials for drug delivery. Chitosan, a polysaccharide made by deacetylation of chitin, has been used in drug delivery in various forms such as films [386], microspheres [387], hydrogels [388] and nanofibers [389]. However, electrospinning of chitosan is difficult and needs to be compounded with other materials, such as PVA [390], pullulan [391] and xanthan gum [392]. Using electrospinning PVA/chitosan-loaded tetracycline hydrochloride (TCH), Alavarse et al. [393] found the drug could be evenly distributed and the material had good antibacterial property and cell compatibility. Balagangadharan et al. [394] developed a new approach by using ionic gelation technique to prepare sinapic acid/chitosan nanoparticles loaded on electrospun PCL nanofibers, which could promote the differentiation of osteoblasts, increase the expression levels of ALP, type Icollagen and osteocalcin. They further analyzed the effects of materials on the osteogenesis process and found that they actived various signaling pathways, such as TGF-β, BMP and FGF2. The calvarial bone defects in rats also showed the effect of materials to promote bone regeneration. In addition, Fazli et al. [395] mixed fumed silica nanoparticles with cefazolin and added them into chitosan–PEO solution for electrospinning to obtain nanofibrous mats. The results showed that drug molecules were coated by nanoparticles, and the nanofiber membranes had higher thermal stability, acid–base stability, tensile strength and better antimicrobial effect, and can promote skin healing.

Table 5.

Some progress of electrospinning in drug delivery in recent years

| Material | Solvent | Flow rate (mL/h) | Distance (cm) | Voltage (kV) | Type | Drug | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cellulose acetate/gliadin | HFIP/TFA | 0.1–0.5 | 20 | 15 | Coaxial | Ferulic acid | [396] |

| Hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin | Water | 0.5 | 15 | 15 | Blend | Ibuprofen | [397] |

| PLA/PVP/multiwall carbon nanotubes | DMF/THF | 0.3–1 | 22.5 | 15 | Blend | Tetracycline hydrochloride | [398] |

| PCL/PEO | DCM/DMF | 0.1–0.6 | 10–15 | 12/15 | Blend | Doxycycline | [399] |

| poly(glycolide-ε-caprolactone)/PLGA | DCM | 2 | 15 | 20 | Blend | papaverine hydrochloride | [400] |

| Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide)/Eudragit L100-55 | Ethanol | 1 | 20 | 16 | Blend | Ketoprofen | [401] |

| Carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals/cellulose acetate | acetone/DMAc | 1 | 15 | 25 | Blend | Tetracycline hydrochloride | [402] |

| PLA/PCL | DCM/DMF | 2 | 15 | 20/25 | Blend | Bovine serum albumin | [403] |

| PCL | Chloroform/methanol | 2 | 15 | 10 | Blend | Cilostazol | [404] |

| Silk fibroin/gelatin | Formic acid | 0.3 | 10 | 20 | Blend | Thyme essential oil/doxycycline monohydrate | [405] |

| Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/methyl acrylate/PEO | DMF/chloroform/methanol | 3 | 18 | 18 | Coaxial | Tetracycline hydrochloride | [406] |

| PVA/chitosan/functionalized graphene oxide | Acetic acid | 0.6 | 14 | 22 | Blend | Curcumin | [407] |

| Ethyl hydroxy ethyl cellulose or hydrophobically modified ethyl hydroxy ethyl cellulose/PVA/citric acid | THF | 0.2 | 15 | 27 | Blend | Chlorhexidine Digluconate | [408] |

| PLA/PVA | DMF/chloroform | 1.5 | 9 | 15 | Blend | Dexamethasone | [409] |

| Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose/PEO/methyl acrylate | DMF/chloroform/methanol | 3/0.4 | 18 | 15 | Coaxial/Blend | Tetracycline hydrochloride | [406] |

| PCL-PEG-PCL | DCM/hexane | 6 | 12 | 18 | Blend | Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles | [410] |

|

Poly(3- hydroxybutyrate-co-3-hydroxyvalerate)/cellulose nanocrystals |

DMF/chloroform/acetone | 1 | 18 | 15 | Blend | Tetracycline hydrochloride | [411] |

| PVA/montmorillonite | Acetic acid | 1–10 | 10–25 | 10–25 | Blend | Bovine serum albumin | [412] |

| Zein | Ethanol | 0.12 | 12 | 24 | Blend | Progesterone | [413] |

| Glutinous rice starch/PVA | Water | 0.3 | 15 | 18–20 | Blend | Chlorpheniramine maleate | [414] |

| PEG/PLGA/Au@Fe2O3 nanoparticles | DMF/DCM | 1 | 15 | 30 | Coaxial | Silibinin | [415] |

| PLLA | HFIP | 0.6 | 12 | 15 | Blend | Lovastatin | [416] |

| TPU | DMF | 1 | 20 | 13 | Blend | Naproxen | [417] |

| PCL/gum tragacanth | Acetic acid | 1 | 15 | 15 | Blend | Curcumin | [418] |

| Chitosan/phospholipids | TFA/DCM | 1.2 | 10 | 25 | Blend | Vitamin B12/curcumin/diclofenac | [419] |

| PCL | Chloroform/methanol | 0.5/0.6 | 9 | 12 | Coaxial | Ampicillin | [420] |

| PU/hydroxypropyl cellulose | DMF | 1 | 15 | 15 | Blend | Donepezil | [421] |

| PVA/collagen | Acetic acid | 0.4 | 15 | 18 | Blend | Salicylic acid | [422] |

| PVA/sodium alginate | Water | 0.3 | 10 | 14 | Blend | Moxifloxacin hydrochloride | [423] |

| Gelatin | Acetic acid | 0.3 | 10 | 12 | Blend | Piperine | [424] |

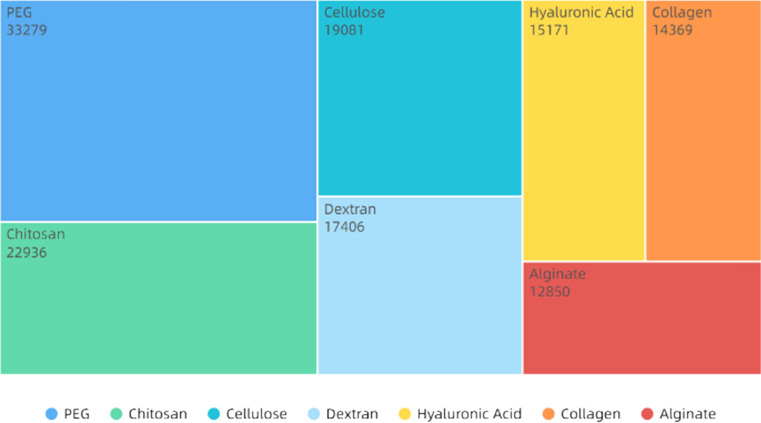

Figure 17.

Publications of drug delivery materials. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Diagnosis

Medical diagnosis is of great importance in the early stage of disease. Medical diagnostic indicators are characterized by specificity and sensitivity. Biosensors are important in medical diagnosis. They have the advantages of low cost, fast detection speed, convenience and small side effects. The high specific surface area of nanofibers can improve the detection sensitivity. The biosensors prepared by electrospinning nanofibers mainly include electrochemical biosensors, organic gas sensors, fluorescent chemical sensors and immunosensors. As shown in Fig. 18, there are more researches on the application of electrospinning technology in medical diagnosis this year. Electrochemical sensors are mainly used for the molecular biological detection of glucose [425–427], proteins [428–430] and genes [431], which are generally composed of the working electrode, counter electrode and reference electrode [432]. Organic gas sensors mainly sense some specific volatile organic compounds, such as aromatic amines [433], acetaldehyde [434] and ammonia. They can be used for the diagnosis of lung cancer, kidney disease [435, 436] and so on. Cancer cells can also be diagnosed by detecting the oxygen concentration [437, 438]. Using tin dioxide and PEO as raw materials, Mehrabi et al. [439] developed a sensor for methanol and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by electrospinning, which can recognize smokers. Fluorescent chemical sensors are mainly used to detect amines in solution [440]. Immunosensors target antigens and antibodies [440]. In addition, Zhao et al. [441] developed a pulse measurement device that can be used to monitor heart rate using the piezoelectric characteristics of PLLA nanofibers along the fiber direction (d33). For cancer cells, targeting molecules include antibodies [442], DNA aptamers [443], E-selectins [444] and peptides, and modification methods include covalent coupling [445] and biotin–streptavidin-specific binding [446]. However, because targeting molecules mostly employed for only a single phenotype of cancer cells, the capture efficiency for multiple types of cancer cells is limited [446]. Pimentel et al. [447] developed a PLLA membrane-based microfluidic substrate for colorimetric detection of glucose, which has many advantages over conventional paper-based substrates. Xu et al. [448] developed a hyaluronic acid and PLGA nanofibers microfluidic chip that can selectively capture CD44 + carcinoma of various origins, especially for HeLa cancer cells and its effectiveness, which can be separated for further analysis.

Figure 18.

Number of publications and times cited on electrospinning in diagnosis. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Energy

Nanomaterials are considered as good advanced materials in the energy field because of their good interfacial chemical reaction rate and easy conduction of charges because of nanosize effect [449–451]. In recent years, there have been many review articles on the application of electrospun nanofibers in energy, which have attracted much attention as shown in Fig. 19 [62, 452–456]. New devices in the energy field include solar cells, fuel cells, lithium-based batteries, sodium-ion batteries and supercapacitors. Lithium-ion batteries, lithium–sulfur batteries and lithium–oxygen batteries, collectively known as lithium-based batteries, are one of the most important energy storage devices. The advantages of nanofibers, such as electrochemical activity, mechanical strength, specific surface area and porosity, indicate that they can improve many shortages of traditional energy storage devices. Wu et al. [457] constructed a core–shell structure of silicon/honeycomb-like carbon framework composite fibers using coaxial electrospinning technology, which showed stable cycle performance and high specific capacity, and was a good anode material. Darbar et al. [458] compared the differences between oxalate decomposition method and electrospinning method for preparing magnesium cobalt oxide negative electrode material, and found the negative electrode material prepared by electrospinning method had better cycling performance. Fuel cells include proton exchange membrane fuel cells, methanol fuel cells, alkaline fuel cells, phosphoric acid fuel cells, solid oxide fuel cells and molten carbonate fuel cells. Park et al. [459] prepared perfluorosulfonic acid (PFSA)/polyphenylsulfone (PPSU) composite nanofiber membranes with high ion conductivity, which are good electrode materials for fuel cells. Supercapacitors can be divided into electrical double-layer supercapacitors and pseudocapacitors (Faradaic supercapacitors) [460]. Kabir et al. [461] studied Fe–N-C platinum group metal-free nanofiber electrodes and found the electric double-layer capacitance increased, the electrode proton transport reduced, and the bulk electrode gas transport properties improved significantly. Pant et al. [462] also studied the electrode materials of supercapacitors. They used titanium dioxide nanoparticles embedded in carbon nanofibers, and their performance was improved. Li et al. [463] prepared ordered mesoporous carbons fiber webs using low molecular resin as carbon precursors, F127 as structure directed agent and PVP as fiber forming agent. They can be directly used as electrode materials of supercapacitor without binders or conductive additives and has high specific capacitance. In addition, the characteristics of electrospun nanofibers make them widely used in the field of oil–water separation. The oil–water separation permeability of electrospinning nanofiber membrane is high, the separation efficiency is high and the energy consumption is low [464]. Obaid et al. [465] incorporated NaOH nanoparticles into PSF nanofibers and a layer of polyamide film on the surface of PSF nanofiber mats by interfacial polymerization of MPD and TMC. The results show that the contact angle of the modified membrane is obviously reduced, and the membrane has good hydrophilicity and permeability, high water flux and can be reused. Li et al. [466] prepared two smart membranes through solution-casting method and electrospinning technology, respectively, based on temperature-responsive copolymer PMMA-b-PNIPAAm and found that the electrospinning membrane has obvious advantages.

Figure 19.

Number of publications and times cited on electrospinning in energy. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Catalysis

In recent years, there are more and more applications of electrospinning in catalysis, as shown in Fig. 20. Because the morphology, particle size and structure of the catalyst will affect its activity, the specific surface area, pore size, porosity and uniformity of electrospun nanofibers have great advantages. Some nanofibers can be directly used as catalysts after chemical treatment. In addition, catalyst immobilization on the surface of nanofibers is also widely used [467]. Nanofiber catalysts can be mainly divided into polymers, metals and oxides according to the materials. Nanofibers can immobilize enzymes [468], metals [469] and oxides [67, 470, 471]. Ternero-Hidalgo et al. [472] prepared V-Zr-O submicron fibers by electrospinning, which can be widely used in partial oxidation of alkanes. Lu et al. [473] prepared PAN/iron nitrate nanofibers and then converted them into carbon/iron nanofibers by one-pot carbonization process, which can be used as nanoadsorbents for Cr(VI). Xu et al. [474] prepared cellulose nanofibers and then deposited silver nanoparticles on the surface of the fibers, which was conducive to the reduction of p-nitrophenol. In addition, Hu et al. [475] used electrospun PVA/PEI nanofibers loaded with Au/Ag bimetallic nanoparticles to reduce 4-nitrophenol. Ma et al. [470] prepared PVP/[PW12 + Ti(OC4H9)4] composite nanofibers, which showed good desulfurization catalytic performance. NiO nanofibers were prepared by Hosseini et al. [476], which were effective for ethylene glycol oxidation after modification of carbon paste electrodes. Hosseini et al. [67] also prepared PVA/Cu(OAc)2-Ni(OAc)2 composite nanofibers to improve the electrocatalytic activity of the modified electrode. Interestingly, Chen et al. [477] prepared a kind of Fe3O4 nanofibers as peroxidase mimics with good catalytic activity for the oxidation of 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) by hydrogen peroxide.

Figure 20.

Number of publications and times cited on electrospinning in catalysis. All the data used are from web of science. The functions we used are analyze results and create citation report

Conclusion