Abstract

Context:

Poor health, including mental health and substance use disorder, can be causes and consequences of homelessness. Approximately 2.1 million persons per year in the United States experience homelessness. People experiencing homelessness have high rates of emergency department use, hospitalization, substance use treatment, social service use, arrest, and incarceration.

Objectives:

A standard approach to treating homeless persons with a disability is called Treatment First, requiring clients be “housing ready”—that is, in psychiatric treatment and substance-free—before and while receiving permanent housing. A more recent approach, Housing First, provides permanent housing and health, mental health, and other supportive services without requiring clients to be housing ready. To determine the relative effectiveness of these approaches, this systematic review compared the effects of both approaches on housing stability, health outcomes, and health care utilization among persons with disabilities experiencing homelessness.

Design:

A systematic search (database inception to February 2018) was conducted using eight databases with terms such as “housing first,” “treatment first,” and “supportive housing.” Reference lists of included studies were also searched. Study design and threats to validity were assessed using Community Guide methods. Medians were calculated when appropriate.

Eligibility Criteria:

Studies were included if they assessed Housing First programs in high income nations; had concurrent comparison populations; assessed outcomes of interest; and were written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals or government reports.

Main Outcome Measures:

Housing stability, physical and mental health outcomes, and health care utilization.

Results:

Twenty-six studies in U.S. and Canada met inclusion criteria. Compared with Treatment First, Housing First programs decreased homelessness by 88%, improved housing stability by 41%. For clients living with HIV, Housing First programs reduced homelessness by 37%, viral load by 22%, depression by 13%, emergency departments use by 41%, hospitalization by 36%, and mortality by 37%.

Conclusions:

Housing First programs improved housing stability and reduced homelessness more effectively than Treatment First. In addition, Housing First programs showed health benefits and reduced health services use. Healthcare systems that serve homeless patients may promote their health and well-being by linking them with effective housing services.

Keywords: systematic review, Housing First programs, homelessness, persons living HIV experiencing homelessness

Introduction

Poor health, including mental health and substance use disorders, are causes and consequences of homelessness.1-3 According to the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), approximately 1.4 million people in the United States slept in homeless shelters at least once during 2017.4 Point-in-time estimates showed that approximately 1/3 of homeless persons were unsheltered in 2017.4 Combining the two findings, it can be estimated that about 2.1 million people experienced homelessness that year. Approximately half of those experiencing homelessness have a disabling condition, defined by HUD to include limitations in daily activities, inability to work or live independently, or having HIV infection.4,5 In poor physical and mental health and lacking resources, homeless persons may consume extensive societal resources.6

A standard approach to treating persons living with disabilities and experiencing homelessness, “Treatment First,” requires that clients be “housing ready”—in psychiatric treatment and substance-free—prior to permanent housing.7 An alternative approach, Housing First, provides regular, subsidized, permanent housing and supportive services to persons with disabilities experiencing homelessness without requiring prior treatment or sobriety.7 Housed clients are encouraged, but not required, to receive treatment and maintain sobriety.7 This approach was first assessed in New York City, followed by a collaborative HUD and Veterans Affairs Supportive Housing (HUD-VASH) program for homeless veterans, and a large-scale experiment in Canada. There has been no quantitative systematic review of program effectiveness. This review examined Housing First compared with Treatment First or treatment as usual (TAU) in achieving housing stability, improving health, and reducing health care utilization.

Methods

Guide to Community Preventive Services (“Community Guide”) methods were used for this review.8,9 This review is PRISMA adherent, and the checklist is available at http://links.lww.com/JPHMP/A679. A systematic search used citation databases (inception to February 2018) such as PubMed, Embase, PsycINFO, and ERIC, with terms such as “housing first” and “supportive housing.” Detailed search strategy can be found here. Publications also were identified from study references and review team recommendations.

Studies were included if they assessed Housing First programs implemented in high income nations, reported outcomes of interest, and were written in English and published in peer reviewed journals or government reports. Community Guide methods include a wide array of study designs to better assess effectiveness of public health interventions. Studies were included in this review if they had concurrent comparison groups. Meta-analysis was not conducted due to heterogeneity in study design and intervention characteristics. Study control populations were commonly categorized either as “Treatment First” or “treatment as usual” (TAU) by study authors. When authors didn’t provide the designation, reviewers categorized the control groups by examining intervention descriptions.

Two reviewers screened search results and abstracted qualifying studies; disagreements were reconciled by consensus. Each study was assessed for design and threats to validity, and limitations were assigned for the following potential threats: inadequate description of the intervention and population, failure to describe sampling frame, inadequate measurement of exposure and outcomes, inappropriate analytic methods, high or differential attrition, and failure to consider or control for confounding. Study quality of execution was categorized as good (0–1 limitation), fair (2–4), or limited (>4). Studies of limited quality of execution were excluded from analysis.8,9

Outcomes of interest included homelessness and housing stability, physical and mental health, substance use, quality of life, and health service use. Because outcomes were measured in different ways, relative percent changes were calculated for each study, comparing intervention and control participants. Detailed outcome definitions can be found in the summary evidence table. Relative percent changes for each outcome were combined to assess the overall findings for that outcome. Medians and interquartile intervals (IQI) were calculated for outcomes with >4 data points. Outcomes were reported separately for clients living with HIV infection and veterans enrolled in HUD-VASH.

Results

Search Yield

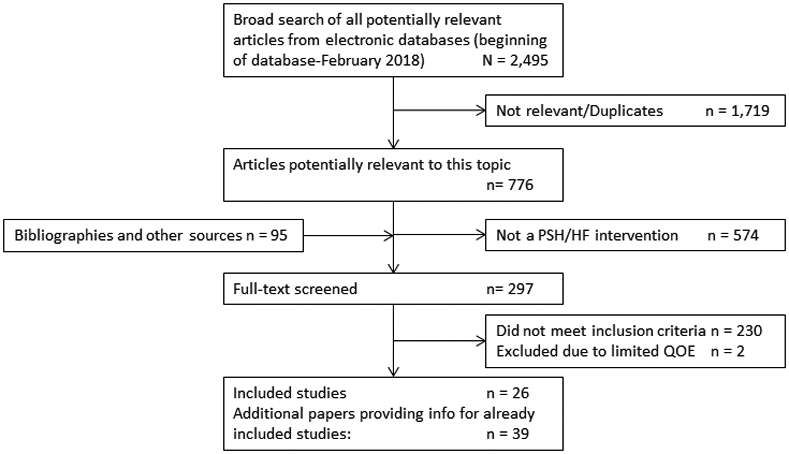

A total of 2,590 citations were screened: 2,495 from the search and 95 from reference lists or team recommendation. Full-text screening was conducted for 297 publications; 28 publications met inclusion criteria, but two10,11 were excluded for limited quality of execution, leaving 266,7,12-35 studies (in 65 publications) with a total of 17,182 participants for the review (Figure 1). Summary evidence table for all included studies can be found here.

Figure 1.

Search results.

Quality of Execution Assessment 1

Studies were either randomized controlled trials7,14,20,22,28,30,32,35 or pre-post studies with concurrent control groups.* They were of good14,18,23,29,34,35 or fair† quality of execution. The most common limitations in this body of evidence were unclear description of the population or intervention,‡ lack of details for sampling frame,§ high attrition,∥ and potential bias due to differential attrition for intervention and control groups.15,16,25,27,28

Study, Intervention, and Participant Characteristics

Included studies evaluated Housing First programs in the United States¶ or Canada.15,20,27 No study from other high-income nations met study inclusion criteria. Included programs were implemented in urban,6,7,12-29,31,33-35 suburban,32 or a combination of these settings;30 no study examined a program in a rural setting. Most programs recruited participants experiencing homelessness and with a mental health disorder,13,16,19,20,31,32 substance use disorder,6,15,22 or a dual diagnosis7,12,17,23,26,30,33,34 that affect their ability to work. Some programs recruited participants experiencing homelessness and having a disabling condition that limits their capacity to work.21,24,27 Three studies18,25,28 examined the HUD-VASH program recruiting veterans with high health and housing needs. Three studies14,29,35 recruited participants living with HIV infection. Only one study recruited homeless families,30 with the rest recruiting individuals experiencing homelessness.

All control groups received health services with or without housing services. Some control groups were enrolled in Treatment First programs7,25,26,30,32-34 while others received TAU with some12-16,18,20-22,27,28,35 or no6,17,19,23,24,29,31 description of health or housing services being provided.

Housing First clients were offered living by themselves in an apartment,7,12,14,15,17-19,21,23,26,27,29,32-35 living with other clients in a group home,6,13,22,31 or a choice between the two options.16,20,24,25,28,30 Clients could choose among services and among housing options that met standards of accessibility and reasonable accommodation. Housing First programs were operational for less than 12 months,13,14,16,18,22,25-27,31 between 12 and 24 months,6,7,15,17,19-21,23,24,30,32,35 or more than 24 months.12,28,29,33,34 Services were provided either through Assertive Community Treatment,12,16,20,26 a centralized system of coordinated services, most often used for clients with more severe problems, or through Intensive Case Management,14,17-19,21,22,28-30 a brokerage system in which clients are referred out for services, often used for clients with more moderate problems.36,37 All offered medical, mental health, and substance use disorder treatment services. Some also offered services to assist with daily tasks7,16,27,32-34 and social integration.7,16,20-22,25,27,28,31-35

The study population had a median age of 42 years,6,7,12-16,18-26,28,30,31,34 74% were male,6,7,12-29,31-35 and most were black6,7,12-14,16-19,22,23,25,26,28-30,32,34,35 (median 50%) or white6,7,12-14,16-19,22,23,25,26,29,30,32,34 (median 32%). The median duration of participant homelessness was 6.4 years, among studies reporting.15,24,27

Effects on Client Housing Status and Health Outcomes (excluding those living with HIV infection)

Housing Stability

Housing First programs reduced homelessness when compared with Treatment First Programs7 (decrease of 88%) or with TAU13,21,24,28 (median decrease of 89%, IQI: −36% to −90%) (Table 1). Homelessness was measured as number of days participants spent homeless13, 21, 24, 28 or proportion of time participants spent homeless7 during the evaluation period. Housing First programs improved housing stability when compared with Treatment First7,25,30,32-34 (median increase of 41%, IQI: 18% to 166%) or with TAU12,15,16,20,24,27,28 (median increase of 54%, IQI: 25% to 1088%) (Table 1). Housing stability was reported as number of days participants were housed24, 27, 28 or proportion of time participants were stably housed7, 12, 15, 16, 20, 25, 30, 32-34 during the evaluation period.

Table 1.

Intervention effectiveness for people experiencing homelessness with a disability.

| Outcome | Comparison Group |

Number of Studies |

Relative Difference | Favorabilitya |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homelessness | Treatment First | 17 | −88% | Favorable |

| Homelessness | Treatment as usual | 413,21,24,28 | −89% Range: −36% to −90% |

Favorable |

| Housing stability | Treatment First | 67,25,30,32-34 | 41% IQI: 18% to 166% |

Favorable |

| Housing stability | Treatment as usual | 712,15,16,20,24,27,28 | 54% IQI: 25% to 1088% |

Favorable |

| Physical health | Treatment as usual | 215,24 | 3.3%, −0.2% | Negligible change observed |

| Mental health | Treatment as usual | 415,20,24,28 | −2% IQI: −5% to 4% |

No change observed |

| Alcohol use | Treatment First | 17 | 57% | Unfavorable |

| Alcohol use | Treatment as usual | 415,22,24,28 | −30% Range: −82% to 36% |

Favorable |

| Illegal drug use | Treatment First | 17 | 11% | Unfavorable |

| Illegal drug use | Treatment as usual | 215,24 | −1%, 62% | Unfavorable |

| Alcohol and drug use | Treatment First | 126 | −71% | Favorable |

| Quality of life | Treatment as usual | 415,20,27,28 | 5% Range: 2% to 10% |

Favorable |

| Community integrationb | Treatment as usual | 320,24,27 | 14% Range: 1% to 227% |

Favorable |

| Emergency department use | Treatment as usual | 318,20,31 | −5% Range: −65% to 20% |

Favorable |

| Hospitalization | Treatment as usual | 218,31 | −36% and −7% | Favorable |

Abbreviations: IQI = interquartile interval, calculated with five or more data points; Range = max and mean of effect estimates, reported with less than five data points

Favorability refers to greater outcome improvement in the intervention population when compared with the control population.

Community integration: Extent to which an individual lives, participates, and socializes in his/her community, measured, for example, in the Wisconsin Quality of Life Index.

Health, Wellness, and Emergency Department and Hospital Utilization

Housing First programs produced similar changes in physical health15,24 and mental health15, 24, 28 scores or symptoms such as suicide attempts20 when compared to TAU (Table 1). Studies comparing Housing First with Treatment First programs7,26 or TAU15,22,24,28 reported mixed results on clients’ alcohol and illegal substance use (Table 1).

Compared with TAU, Housing First programs improved clients’ quality of life score15,20,27,28 and increased their community integration score20,24,27 (Table 1). In the largest randomized trial (2,148 persons with serious mental illness and experiencing homelessness in Canada), Housing First clients were more than twice as likely to report positive life changes and 25% as likely to report negative life changes when compared with clients in TAU.20

Participants of Housing First programs had less emergency department use18,20,31 and hospitalization18,31 when compared with TAU (Table 1).

Effect on Housing and Health Outcomes for Clients Living with HIV Infection

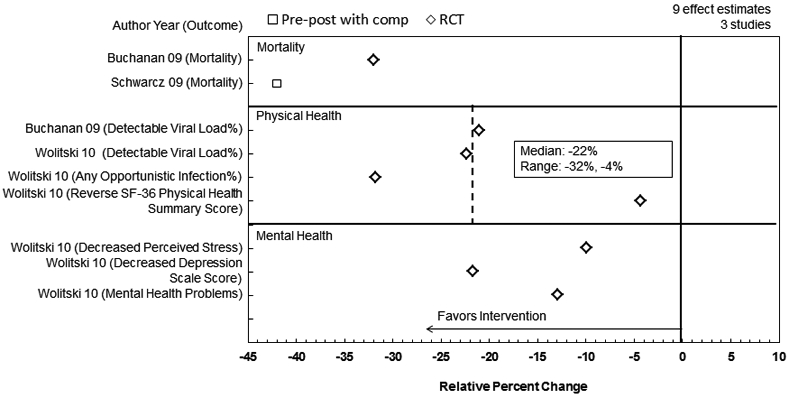

Housing First clients living with HIV infection, when compared with those in TAU, had 63% greater housing stability and 38% less homelessness.35 Client physical health, e.g., detectable viral load and opportunistic infections,14,35 improved by a median relative change of 22% (range: −32% to −4%) (Figure 2). Clients had reduced perceived stress, depression, and other mental health problems.35 Two studies reported decreased mortality of 32% and 42%.14,29

Figure 2.

Intervention effectiveness for people experiencing homelessness and living with HIV/AIDS.

Effect on Housing and Health Outcomes for Veterans in HUD-VASH

Three studies18,25,28 evaluated HUD-VASH programs, focusing on veterans who were homeless and had psychiatric or substance use disorders, or both. HUD-VASH reduced homelessness among veterans by 36% when compared with TAU.28These programs also improved housing stability by 14% when compared with Treatment First25 and by 25% when compared with TAU.28 Clients of HUD-VASH also showed a 51% reduction in alcohol use, a 4% improvement in mental health, and a 10% improvement in quality of life.28 During the first year of the HUD-VASH program, veterans had higher rates of emergency department, mental health, and medical visits as well as hospitalizations than veterans who were still homeless.18,28

Implications for Policy and Practice

Housing First Programs are more effective in improving client housing stability compared with Treatment First Programs or treatment as usual. Housing First Programs examined in this review were implemented in a few metropolitan areas and mostly recruited clients experiencing chronic homelessness who had severe mental health or substance abuse issues or both. More research and resources might be needed to increase the number of programs and evaluate program effectiveness in additional urban settings and in rural areas.

Providing permanent housing to persons living with HIV improved their housing stability and health. Clients showed reduced viral load, which could lead to reduced HIV transmission.

Health care systems, physicians, and allied health professionals can more effectively care for patients if they recognize and respond to the social conditions that are a source of health problems as well as potential solutions to those problems.38 Some strategies have already been taken or are being considered, such as hospital system provision of housing for homeless patients with severe and chronic health problems,39 healthcare providers asking patients about their housing and linking them to needed services,40 provision of public health training to undergraduate medical students, residents, and continuing education for healthcare providers to demonstrate the powerful roles of social determinants in origins of health issues, and inform practitioners of available solutions and resources.41,42

Discussion

Evidence from this systematic review indicates that Housing First programs can more effectively reduce homelessness and improve housing stability for homeless populations with a disability than Treatment First or TAU. Housing First programs offer permanent housing with accompanying health and social services, and their clients are able to maintain a home without first being substance-free or in treatment. Clients in stable housing experienced better quality of life and generally showed reduced hospitalization and emergency department use. For clients living with HIV infection, Housing First programs improved physical and mental health and reduced mortality. With stable housing, clients with HIV infection had a place to receive, store, and take their medications, leading to improved adherence, reduced viral loads, and downstream health benefits.14

Housing First programs produced similar changes in physical and mental health and substance use when compared with Treatment First or TAU, i.e., Housing First yielded no additional health benefit. Housing is an established social determinant of health43 and the current review showed that Housing First programs led to improved housing stability, so it is puzzling that Housing First clients, other than those with HIV infection, did not experience additional health benefit. There are several hypothetical explanations for the absence of additional health benefit with Housing First: 1) included studies reported outcomes for clients who remained in the programs at follow-up. Included studies reported higher attrition for clients in TAU15,16,27,28 and Treatment First Program25 than for Housing First programs, and it is possible that clients in the control populations with more severe issues were lost to follow-up, while those in Housing First were easier to locate because of their housing; 2) the study population has severe and often chronic health issues; longer treatment might be needed to produce health benefit; 3) by requiring clients to be housing ready, Treatment First programs may select for clients more likely to make and maintain behavior changes. Funding available, Housing First accepts all clients, perhaps housing clients with more severe baseline health issues; 4) while Housing First clients are not penalized for substance use, Treatment First clients may lose their housing and thus may underreport this behavior; 5) Treatment First clients were required to continue treatment and may have benefited from required treatment, while for Housing First clients, treatments were optional.

Analysis of the effects of Housing First faced several challenges. Good descriptions of services available to and used by clients in both control types are rare.44 This limits the ability to understand how and why the Housing First program had the observed outcomes, and to inform potential users on program content. Most studies assessed participants at times 2 or fewer years after their receipt of housing; longer term follow-up may be required to assess possible benefits for chronic physical and mental health conditions.

Included studies reported on a wide range of outcomes using various metrics, precluding the possibility of a meta-analysis. In addition, some effect estimates were calculated from small numbers of data points. For example, even though the effect estimates of Housing First for people living with HIV were meaningful and consistent, they were based on only three studies.14,29,35

The findings of this systematic review indicate that Housing First programs are more effective in reducing homelessness and improving housing stability than Treatment First programs or treatment as usual. In addition, Housing First programs provide health benefits to clients living with HIV infection and may reduce healthcare use for homeless clients overall. Attention to the state of housing, particularly for low-income populations, may improve understanding of the patient health issues and provide opportunities for improved health care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors acknowledge Onnalee A. Gomez (formerly Library Science Branch, Division of Public Health Information Dissemination, CDC) for conducting the searches. Stacy A. Benton, from Cherokee Nation Businesses, provided input to the development of the manuscript.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding:

This review was done with NIH as part of an InterAgency Agreement and was partially funded by NIH. The work of Jamaicia Cobb was supported with funds from the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education (ORISE).

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors of this paper do not have financial holdings related to the intervention reviewed.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors of this paper declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Online Supplement Figures

PRISMA style flow-chart of screening process

Contributor Information

Yinan Peng, Community Guide Office, Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy.

Robert A. Hahn, Community Guide Office, Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy.

Ramona K.C. Finnie, Community Guide Office, Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy.

Jamaicia Cobb, Community Guide Office, Office of the Associate Director for Policy and Strategy.

Samantha P. Williams, Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP).

Jonathan E. Fielding, UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Los Angeles, California.

Robert L. Johnson, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey.

Ann Elizabeth Montgomery, University of Alabama at Birmingham School of Public Health & U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, Virginia.

Alex Schwartz, Milano School of Policy, Management, and Environment, Graduate Program in Public and Urban Policy, New School, San Francisco, California.

Carles Muntaner, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada.

Veronica Helms Garrison, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Washington, DC.

Beda Jean-Francois, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Bethesda, Maryland.

Benedict I. Truman, Office of the Associate Director for Science, NCHHSTP CDC, Atlanta, Georgia.

Mindy T. Fullilove, Milano School of Policy, Management, and Environment, Graduate Program in Public and Urban Policy, New School, San Francisco, California.

References

- 1.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, Medicine. Permanent Supportive Housing: Evaluating the Evidence for Improving Health Outcomes Among People Experiencing Chronic Homelessness. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. 10.17226/25133. Accessed September 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischer PJ, Breakey WR. The epidemiology of alcohol, drug, and mental disorders among homeless persons. J Am Psychol. 1991;46(11):1115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Susser E, Moore R, Link B. Risk factors for homelessness. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15(2):546–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The 2017 annual homeless assessment report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 2: Estimates of homelessness in the United States. Washington D.C. https://files.hudexchange.info/resources/documents/2017-AHAR-Part-2.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed September 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Office of the Assistant Secretary for Community Planning and Development. Homeless emergency assistance and rapid transition to housing: defining “chronically homeless.” In: Department of Housing and Urban Development, ed.24 CFR Parts 91 and 578. Docket No. FR-5809-F-01. Washington D.C. Published 2015:75791-75806. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, Atkins DC, Burlingham B, et al. Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349–1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsemberis S, Gulcur L, Nakae M. Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. AJPH. 2004;94(4):651–656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briss P, Zaza S, Pappaioanou M, Fielding J, Wright-De Agüero L, et al. Developing an evidence-based guide to Community Preventive Services-methods. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(15):35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zaza S, Wright-De Agüero LK, Briss PA, Truman BI, Hopkins DP, et al. Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the Guide to Community Preventive Services. Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Am J Prev Med. 2000;18(Suppl 1):44–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kisely S, Parker J, Campbell L, Karabanow J, Hughes J, Gahagan J. Health impacts of supportive housing for homeless youth: A pilot study. AJPH. 2008;122(10):1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipton FR, Nutt S, Sabatini A. Housing the homeless mentally ill: A longitudinal study of a treatment approach. J Psychiatr Serv. 1988;39(1):40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Appel PW, Tsemberis S, Joseph H, Stefancic A, Lambert-Wacey D. Housing First for severely mentally ill homeless methadone patients. J Addict Dis. 2012;31(3):270–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown MM, Jason LA, Malone DK, Srebnik D, Sylla L. Housing First as an effective model for community stabilization among vulnerable individuals with chronic and nonchronic homelessness histories. J Community Psychol. 2016;44(3):384–390. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buchanan D, Kee R, Sadowski LS, Garcia D. The health impact of supportive housing for HIV-positive homeless patients: A randomized controlled trial. AJPH. 2009;99(S3):S675–S680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cherner RA, Aubry T, Sylvestre J, Boyd R, Pettey D. Housing First for adults with problematic substance use. J Dual Diagn. 2017;13(3):219–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark C, Rich AR. Outcomes of homeless adults with mental illness in a housing program and in case management only. J Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(1):78–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crisanti AS, Duran D, Greene RN, Reno J, Luna-Anderson C, Altschul DB. A longitudinal analysis of peer-delivered permanent supportive housing: Impact of housing on mental and overall health in an ethnically diverse population. J Psychiatr Serv. 2017;14(2):141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabrielian S, Yuan AH, Andersen RM, Gelberg L. Diagnoses treated in ambulatory care among homeless-experienced veterans: Does supported housing matter? J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(4):281–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gilmer TP, Manning WG, Ettner SL. A cost analysis of San Diego County's REACH program for homeless persons. J Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(4):445–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goering P, Veldhulzen S, Watson A, Adair C, Kopp B, et al. Mental Health Commission of Canada. National At Home/Chez Soi final report. Calgary, Alberta. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/mhcc_at_home_report_national_cross-site_eng_2_0.pdf. Published 2014. Accessed September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanratty M Impacts of Heading Home Hennepin’s Housing First programs for long-term homeless adults. Hous Policy Debate. 2011;21(3):405–419. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kennedy DP, Osilla KC, Hunter SB, Golinelli D, Maksabedian Hernandez E, Tucker JS. A pilot test of a motivational interviewing social network intervention to reduce substance use among housing first residents. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2018;86:36–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessell ER, Bhatia R, Bamberger JD, Kushel MB. Public health care utilization in a cohort of homeless adult applicants to a supportive housing program. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):860–873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mares AS, Rosenheck RA. A comparison of treatment outcomes among chronically homelessness adults receiving comprehensive housing and health care services versus usual local care. J Adm Policy in Ment Health 2011;38(6):459–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery AE, Hill LL, Kane V, Culhane DP. Housing chronically homeless veterans: Evaluating the efficacy of a Housing First approach to HUD-VASH. J Community Psychol. 2013;41(4):505–514. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Padgett DK, Stanhope V, Henwood BF, Stefancic A. Substance use outcomes among homeless clients with serious mental illness: comparing housing first with treatment first programs. Community Ment Health J. 2011;47(2):227–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pankratz C, Nelson G, Morrison M. A quasi-experimental evaluation of rent assistance for individuals experiencing chronic homelessness. J Community Psychol. 2017;45(8):1065–1079. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenheck R, Kasprow W, Frisman L, Liu-Mares W. Cost-effectiveness of supported housing for homeless persons with mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(9):940–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwarcz SK, Hsu LC, Vittinghoff E, Vu A, Bamberger JD, Katz MH. Impact of housing on the survival of persons with AIDS. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shinn M, Samuels J, Fischer SN, Thompkins A, Fowler PJ. Longitudinal impact of a family critical time intervention on children in high-risk families experiencing homelessness: A randomized trial. Am J Community Psychol. 2015;56(3-4):205–216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srebnik D, Connor T, Sylla L. A pilot study of the impact of housing first–supported housing for intensive users of medical hospitalization and sobering services. AJPH. 2013;103(2):316–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stefancic A, Tsemberis S. Housing First for long-term shelter dwellers with psychiatric disabilities in a suburban county: A four-year study of housing access and retention. J Prim Prev. 2007;28(3-4):265–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsemberis S From streets to homes: An innovative approach to supported housing for homeless adults with psychiatric disabilities. J Community Psychol. 1999;27(2):225–241. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsemberis S, Eisenberg RF. Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51(4):487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolitski RJ, Kidder DP, Pals SL, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of housing assistance on the health and risk behaviors of homeless and unstably housed people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):493–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bratcher K, Burchman H, Casey R, Cho R, Clark C, et al. VA National Center for Homelessness among Veterans. Permanent supportive housing resource guide. Philadelphia, PA. https://www.va.gov/HOMELESS/nchav/docs/Permanent%20Supportive%20Housing%20Resource%20Guide%20-%20FINAL.PDF. Published 2015. Accessed September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Permanent supportive housing: building your program. Rockville, MD. https://store.samhsa.gov/system/files/buildingyourprogram-psh.pdf. Published 2010. Accessed September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berwick DM. To Isaiah. JAMA. 2012;307(24):2597–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuehn BM. Hospitals turn to housing to help homeless patients. JAMA. 2019;321(9):822–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hansen H, Metzl J. Structural competency in the US healthcare crisis: putting social and policy interventions into clinical practice. J Bioeth Inq. 2016;13(2):179–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Geiger HJ. The political future of social medicine: Reflections on physicians as activists. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):282–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sklar DP. Reaching out beyond the health care system to achieve a healthier nation. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):271–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaw M. Housing and public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25(1):397–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burt MR, Pollack D, Sosland A, Mikelson KS, Drapa E, et al. The Urban Institute. Evaluation of continuums of care for homeless people. Final Report. Washington D.C. http://webarchive.urban.org/UploadedPDF/continuums_of_care.pdf. Published 2002. Accessed September 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.