Abstract

Glial cells are non-neuronal cells in the nervous system that are crucial for proper brain development and function. Three major classes of glia in the central nervous system (CNS) include astrocytes, microglia and oligodendrocytes. These cells have dynamic morphological and functional properties and constantly surveil neural activity throughout life, sculpting synaptic plasticity. Astrocytes form part of the tripartite synapse with neurons and perform many homeostatic functions essential to proper synaptic function including clearing neurotransmitter and regulating ion balance; they can modify these properties, in addition to additional mechanisms such as gliotransmitter release, to influence short- and long-term plasticity. Microglia, the resident macrophage of the CNS, monitor synaptic activity and can eliminate synapses by phagocytosis or modify synapses by release of cytokines or neurotrophic factors. Oligodendrocytes regulate speed of action potential conduction and efficiency of information exchange through the formation of myelin, having important consequences for the plasticity of neural circuits. A deeper understanding of how glia modulate synaptic and circuit plasticity will further our understanding of the ongoing changes that take place throughout life in the dynamic environment of the CNS.

Keywords: Glia, synapse, plasticity, learning

INTRODUCTION

Neurons in the central nervous system (CNS) communicate via synapses. Elucidation of the involvement of glia in synaptic regulation has been an ongoing pursuit leading to important discoveries of the dynamic properties of the CNS, one of which is glial involvement in synaptic plasticity. Synaptic plasticity refers to the transient or long-lasting changes in strength a synapse may undergo. Glia are the non-action potential generating cells in the CNS; they include astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. They are involved in the development, formation, and pruning of neuronal synapses and circuitry, thus influencing the homeostasis and function of the CNS throughout life (Allen and Barres, 2005; Herculano-Houzel, 2014; Reemst et al., 2016). At the synapse, astrocytes are involved in clearance of neurotransmitters, release of gliotransmitters, and regulation of ion balance (Goubard, Fino and Venance, 2011; Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014; Sibille, Pannasch and Rouach, 2014; Murphy-Royal et al., 2017). In addition to their immune properties as being resident macrophages (Helmut et al., 2011), microglia processes contact other cells including astrocytes, neurons and blood vessels. This allows for constant regulation of synapses, for example microglial elimination of neuronal processes and dendritic spines that fail to form functional connections (Colonna and Butovsky, 2017). Oligodendrocytes originate from oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) throughout life, and are the myelin forming cells in the CNS (Bradl and Lassmann, 2010; Allen and Lyons, 2018). Myelin sheaths regulate the speed of propagation of information through axons and their structural characteristics are dynamic, hence providing plasticity to conduction velocity and efficiency of information exchange between neurons in a circuit (Ronzano et al., 2020).

In this review we will discuss how astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes, with their specific structural and functional properties, contribute to and regulate synaptic plasticity in the dynamic environment of the CNS. Table 1 briefly outlines the characteristics of different forms of synaptic plasticity. This review is non-exhaustive and research regarding how glia are involved in synaptic plasticity has been selected to highlight the present state of the field.

Table 1.

Types of synaptic plasticity

| Type of Synaptic Plasticity | Duration | Forms | Experimental approach | Molecular Mechanisms involved | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term Plasticity | Seconds to minutes | Synaptic

facilitation Augmentation Post-tetanic potentiation |

Paired pulse ratio | Vesicle

availability Release Probability |

(Katz and Miledi, 1968; Thomson, 2000; Hanse and Gustafsson, 2001; Zucker and Regehr, 2002; Araque et al., 2014) |

| Synaptic Depression | |||||

| Long-term Plasticity | Hours to days | Long-term Potentiation (LTP) | Tetanus stimulation In-vivo imaging of dendritic spines Theta-burst stimulation |

Traffic of AMPAR Activation of NMDAR Changes in gene expression New protein synthesis Protein phosphorylation Generation of new synapses, including dendritic spines |

(Malenka and Nicoll, 1999; Malinow, 2003; Citri and Malenka, 2008; Kessels and Malinow, 2009; Kandel, Dudai and Mayford, 2014) |

| Long-term Depression (LTD) |

ASTROCYTES

Astrocyte properties and functions

Astrocytes arise from the neural stem cell lineage (Reemst et al., 2016). They tile the brain, with their bushy, non-overlapping processes forming astrocytic domains and contacting thousands of neuronal synapses (Bushong et al., 2002; Bushong, Martone and Ellisman, 2004). While not all synapses are contacted by astrocytic processes, electron microscopy (EM) and super-resolution imaging techniques have offered a glimpse into the close relationship between neuronal synapses and astrocytic processes (Ventura and Harris, 1999; Kasthuri et al., 2015; Heller and Rusakov, 2017; Octeau et al., 2018). Astrocytes interact with synapses throughout the time of synapse formation and maturation (see Farhy-Tselnicker and Allen, 2018 for a review), and regulate these events through a wide range of matricellular and cell adhesion molecules (see Hillen, Burbach and Hol, 2018 for a comprehensive review). Astrocytic molecules that regulate synapse number and function include, but are not limited to the thrombospondin family, glypican 4, cholesterol, chordin-like 1, astrocytic neuroligins, Hevin, and Sparc (Ullian et al., 2001; Eroglu et al., 2009; Kucukdereli et al., 2011; Allen et al., 2012; Singh et al., 2016; Farhy-Tselnicker et al., 2017; Stogsdill et al., 2017; Blanco-Suarez et al., 2018).

Astrocytes play a prominent role in regulating neuronal excitability and action potential propagation through a number of mechanisms, including by maintaining appropriate levels of extracellular potassium (K+) (Hertz, 1965; Hertz and Chen, 2016; Bellot-Saez et al., 2017). Astrocytes also express high-affinity glutamate uptake transporters, the excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs) (Danbolt, 2001; Rose et al., 2018), with the main subtypes in the hippocampus being EAAT1 (GLAST; glutamate/ aspartate transporter) and EAAT2 (GLT-1; glutamate transporter 1). This astrocyte-mediated uptake of glutamate conserves proper neuronal function and reduces excitotoxicity (Murphy-Royal et al., 2017; Rose et al., 2018). Astrocytic processes also contain membrane-bound receptors for many neurotransmitters and neuromodulators, including glutamate, GABA, adenosine, acetylcholine, and endocannabinoids (Agulhon et al., 2008; Allen, 2014). Most of these receptors are G protein- coupled receptors; some of the most well-known are metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs), which detect excitatory synaptic transmission between neurons (Panatier and Robitaille, 2016). Activation of mGluRs can activate a variety of intracellular signaling cascades in astrocytes, including intracellular calcium (Ca2+) elevations (Panatier and Robitaille, 2016).

One of the most well-characterized mechanisms of astrocytic intracellular Ca2+ signaling is the canonical phospholipase C (PLC) and inositol 1,4,5- triphosphate (IP3) pathway; when GPCRs such as mGluRs are activated, the coupled Gq protein leads to IP3 receptor activation and Ca2+ release from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Agulhon et al., 2008; Volterra, Liaudet and Savtchouk, 2014; Bazargani and Attwell, 2016; Shigetomi, Patel and Khakh, 2016). Astrocytic Ca2+ signaling has been described in the cytosol of the soma in response to neuronal activity (Wang et al., 2006; Winship, Plaa and Murphy, 2007; Schipke, Haas and Kettenmann, 2008; Ding et al., 2013; Lind et al., 2013). Recent studies have also established Ca2+ signaling in astrocytic endfeet and synapse-associated processes in response to neuronal activity (Shigetomi et al., 2013; Otsu et al., 2015; Agarwal et al., 2017; Bindocci et al., 2017a; Stobart et al., 2018). Moreover, Ca2+ transients in astrocytic processes are mediated by Ca2+ influx from the extracellular space through transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, in addition to release from the ER, though the exact contribution of each Ca2+ source remains to be determined (Bazargani and Attwell, 2016).

The relationship between neuronal activity and astrocytes is a bidirectional one, with neuronal activity influencing astrocytic activation, which in turn can affect neuronal activity. One of the most well-studied consequences of intracellular Ca2+ increase is a release of gliotransmitters from astrocytes, such as D-serine, an endogenous co-agonist of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDARs; Yang et al., 2003). Another astrocyte-derived gliotransmitter implicated in plasticity is adenosine tri-phosphate (ATP), which gets degraded into adenosine in the extracellular space. ATP was found to be released from cultured mouse astrocytes upon Ca2+ wave propagation that was induced via extracellular stimulation (Guthrie et al., 1999). ATP released from astrocytes was involved in generating Ca2+ waves via the activation of purinergic receptors in astrocytes (Guthrie et al., 1999). A third proposed gliotransmitter is glutamate, which in certain brain areas and under certain conditions can be released from astrocytes. While astrocytes do not have the enzymes necessary for glutamate synthesis, they take up synaptically-released glutamate after neuronal activation through EAATs (Rose et al., 2018). The exact mechanisms and spatial and temporal scales of gliotransmission are still under investigation (Araque et al., 2014; Sloan and Barres, 2014).

We will discuss experiments demonstrating the role of gliotransmission in neuronal short- and long-term plasticity. Furthermore, we will discuss other ways in which astrocytes can modulate the strength of neuronal synapses including ion and neurotransmitter uptake, transcriptional changes, and secretion of synapse-regulating proteins.

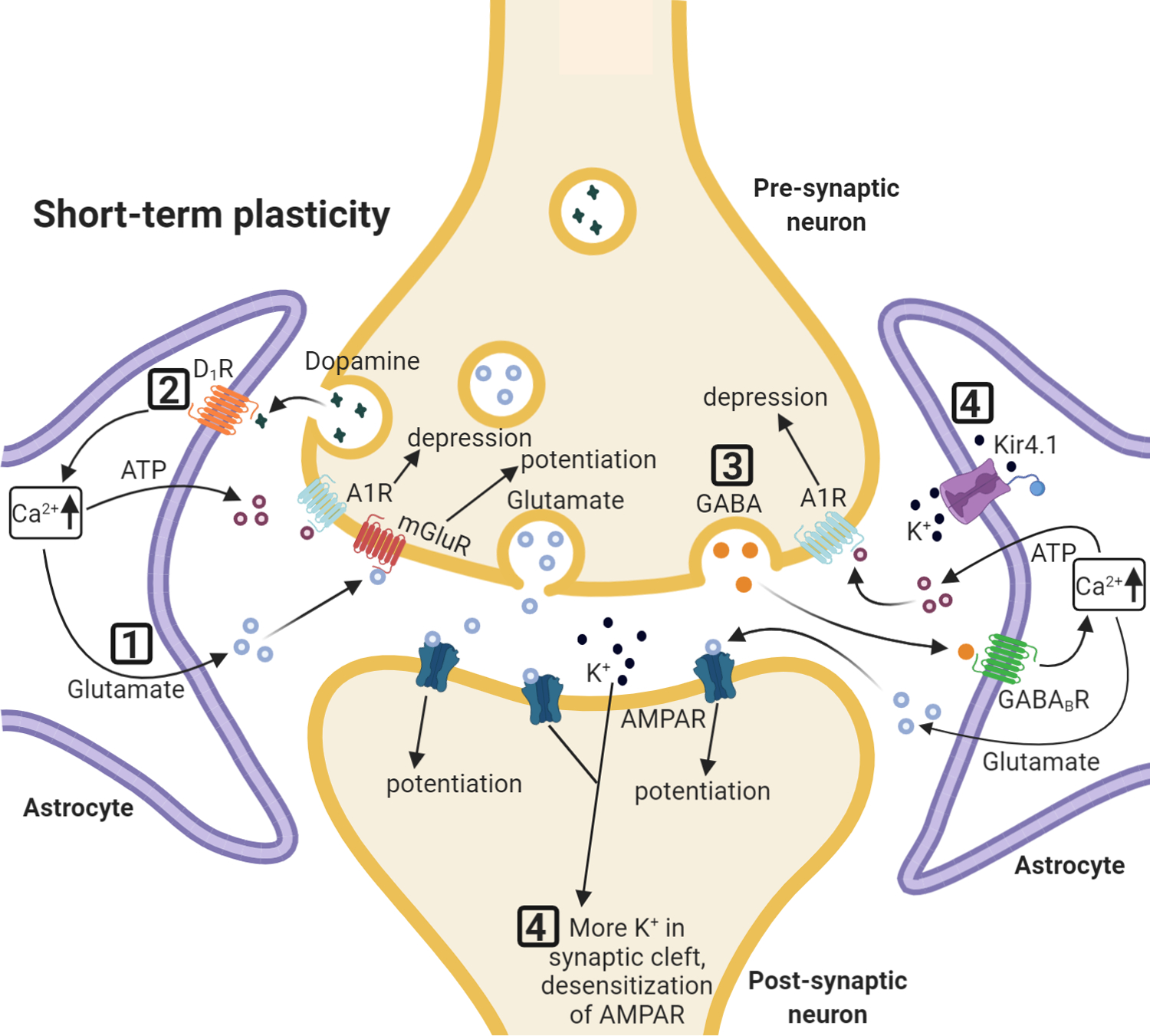

Short-term plasticity

Short-term synaptic plasticity can be regulated by astrocytes in several ways, as they detect changes in neuronal activity and respond with alterations in intracellular Ca2+, which in turn leads to processes that modulate ongoing neuronal activity (Allen, 2014; see Figure 1 for a schematic of pathways). Astrocytic Ca2+ fluctuations are dynamic and regulated by neuronal activity (Sibille et al., 2015). For example, repetitive stimulation of Schaffer collaterals in juvenile mouse hippocampal slices leads to an initial facilitation of glutamatergic synaptic transmission followed by a depression due to a decrease in the availability of glutamate vesicles. Interestingly, astrocyte Ca2+ signaling also increases in response to ongoing stimulation, but in contrast to the neuronal response, which depresses, the astrocyte calcium response is sustained (Sibille et al., 2015). This sustained increase in astrocyte activation suggests that astrocytes have the potential to be regulating ongoing synaptic transmission, through mechanisms outlined below.

Figure 1: Astrocytes and short-term synaptic plasticity.

Selected effects of astrocytic regulation of synaptic short-term plasticity. (1) Increase in Ca2+ leads to astrocytic glutamate release interacting with group I mGluRs on neuronal presynaptic membranes. (2) Synaptic release of dopamine increases Ca2+ in astrocytes via astrocytic D1 receptors, and leads to the release of ATP/adenosine, which causes temporary depression of excitatory synaptic transmission. (3) Astrocytic Ca2+ increase via GABAB receptor activation leads to glutamate and ATP release. Glutamate initially increases synaptic potentiation and is followed by ATP/adenosine induced depression. (4) Astrocytic K+ uptake by astrocytes regulates K+ availability in the synaptic cleft and accumulation of K+ leads to AMPAR desensitization.

Release of gliotransmitters and short-term plasticity

An early indication of a role for astrocytes in regulating short-term plasticity came from experiments in developing mouse hippocampal slices. When Ca2+ increases were evoked in stratum radiatum astrocytes by uncaging IP3, recordings of CA1 pyramidal neurons showed a significant increase in α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptor (AMPAR)-mediated spontaneous excitatory postsynaptic current (sEPSC) frequency (Fiacco and McCarthy, 2004). This transient increase in frequency was due to the release of glutamate from astrocytes interacting with group I mGluRs on excitatory afferent terminals rather than postsynaptic receptors (Fiacco and McCarthy, 2004). Specifically, both presynaptic mGluR1 and mGluR5 are implicated in the astrocyte-mediated transient potentiation of Schaffer collateral synapses in CA1 pyramidal neurons, as blocking them prevented the effect (Perea and Araque, 2007).

Hippocampal astrocytes in juvenile rats can also release ATP/adenosine in response to mGluR5 activation; this released ATP activated presynaptic A2A receptors and increased synaptic efficacy as measured by failure rate (Panatier et al., 2011). Activation of inhibitory interneurons in mouse adult hippocampal slices can elevate Ca2+ in astrocytes via GABAB receptors, causing the release of both glutamate and ATP/adenosine and biphasic effects on nearby synapses. The released glutamate induces an initial synaptic potentiation, while the released ATP subsequently results in synaptic depression (Covelo and Araque, 2018). Application of an mGluR1 antagonist selectively prevents the initial potentiation; application of an A1R antagonist selectively abolishes the delayed depression, identifying the mechanism underlying this effect (Covelo and Araque, 2018). In the nucleus accumbens, synaptic release of dopamine increases intracellular Ca2+ in adult mouse astrocytes via astrocytic D1 receptors leading to release of ATP/adenosine, which depresses excitatory synaptic transmission for up to a minute. This dopamine-evoked depression is abolished in glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-D1−/− mice, where the D1 receptor is specifically removed from astrocytes (Corkrum et al., 2020).

Thus, a particular gliotransmitter such as ATP/adenosine released by astrocytes may act on different neuronal receptors and have opposing effects on short-term plasticity depending on which receptors are activated. A computational model examining how astrocytes induce either synaptic depression or facilitation through glutamate release showed that the differential effect may be regulated by fluctuations in astrocytic intracellular Ca2+ levels, in addition to different types of neuronal receptor (de Pittà et al., 2011). The model took into account the amplitude and frequency of astrocytic Ca2+ oscillations and whether the threshold for glutamate release from astrocytes was reached, as well as considering the identity of the presynaptic glutamate receptors; specifically, variations in the density and biophysical properties of these presynaptic receptors. Furthermore, the model found that if astrocytic regulation leads to facilitation and depression simultaneously, these two effects can cancel each other out, resulting in no change in synaptic release (de Pittà et al., 2011).

Astrocytes can also regulate short-term plasticity in cell- and pathway-specific manner, as shown in the dorsal striatum (Martín et al., 2015). In cortico-striatal slices of developing mice, subsets of astrocytes selectively responded to the activity of either D1 or D2 medium spiny neurons (MSN). Moreover, astrocytes selectively regulate specific synapses. Transient synaptic potentiation was observed in D1 MSNs when activating astrocytes that exclusively responded to D1 MSN activation and in D2 MSNs when activating astrocytes that responded to D2 MSNs (Martín et al., 2015). This suggests that astrocytes selectively regulate synaptic transmission in a cell-type specific manner.

Clearance of ions and neurotransmitters and short-term plasticity

Astrocytes contribute to the regulation of short-term synaptic plasticity by clearing neurotransmitters from the synaptic cleft, which can be monitored as the uptake of released neurotransmitters results in synaptically-activated transporter-mediated currents (STCs) in astrocytes. For example, stimulating the afferents from the somatosensory cortex and dually patch-clamping striatal astrocytes and medium spiny neurons (MSNs) revealed GLT-1 and GABA transporter-mediated STCs in the majority of recorded astrocytes in juvenile rats (Goubard, Fino and Venance, 2011). The importance of this was shown by inhibition of GLT-1 and GABA transporters in astrocytes. This led to decreased cortico-striatal synaptic transmission via the desensitization of AMPA receptors due to increased synaptic glutamate levels, combined with activation of GABAA receptors by synaptic GABA (Goubard, Fino and Venance, 2011). Potassium uptake by astrocytes has also been shown to contribute to short-term plasticity of synaptically evoked currents (Sibille, Pannasch and Rouach, 2014). Stimulating Schaffer collaterals in juvenile mouse hippocampal slices results in short-term synaptic plasticity along with activity-dependent changes of astrocyte membrane currents. Conditional removal of the inwardly rectifying potassium channel Kir4.1 from astrocytes leads to decreased potassium uptake, resulting in reduced synaptic responses to repetitive stimulation and post-tetanic potentiation (Sibille, Pannasch and Rouach, 2014).

Further research is necessary to elucidate the detailed mechanisms by which astrocytes regulate short-term synaptic plasticity. As shown in the computational model described by de Pittà and colleagues, intracellular Ca2+ fluctuations may modulate the dynamisms involved in the complex process of synaptic plasticity and may further explain discrepancies encountered in previous research. Advances in Ca2+ imaging techniques have allowed for the field to advance drastically, from experiments involving Ca2+ indicator dyes like Oregon green BAPTA-1 in hippocampal slices (Fiacco and McCarthy, 2004), to 3D imaging in vivo using genetically encoded Ca2+ sensors like GCaMP under astrocytic specific promoters combined with fast scanning two-photon microscopy (Bindocci et al., 2017b). The emergence of new technology combined with genetics and classic molecular biology will allow for important discoveries in the astrocytic regulation of short-term synaptic plasticity.

Long term plasticity

Release of gliotransmitters and long-term plasticity

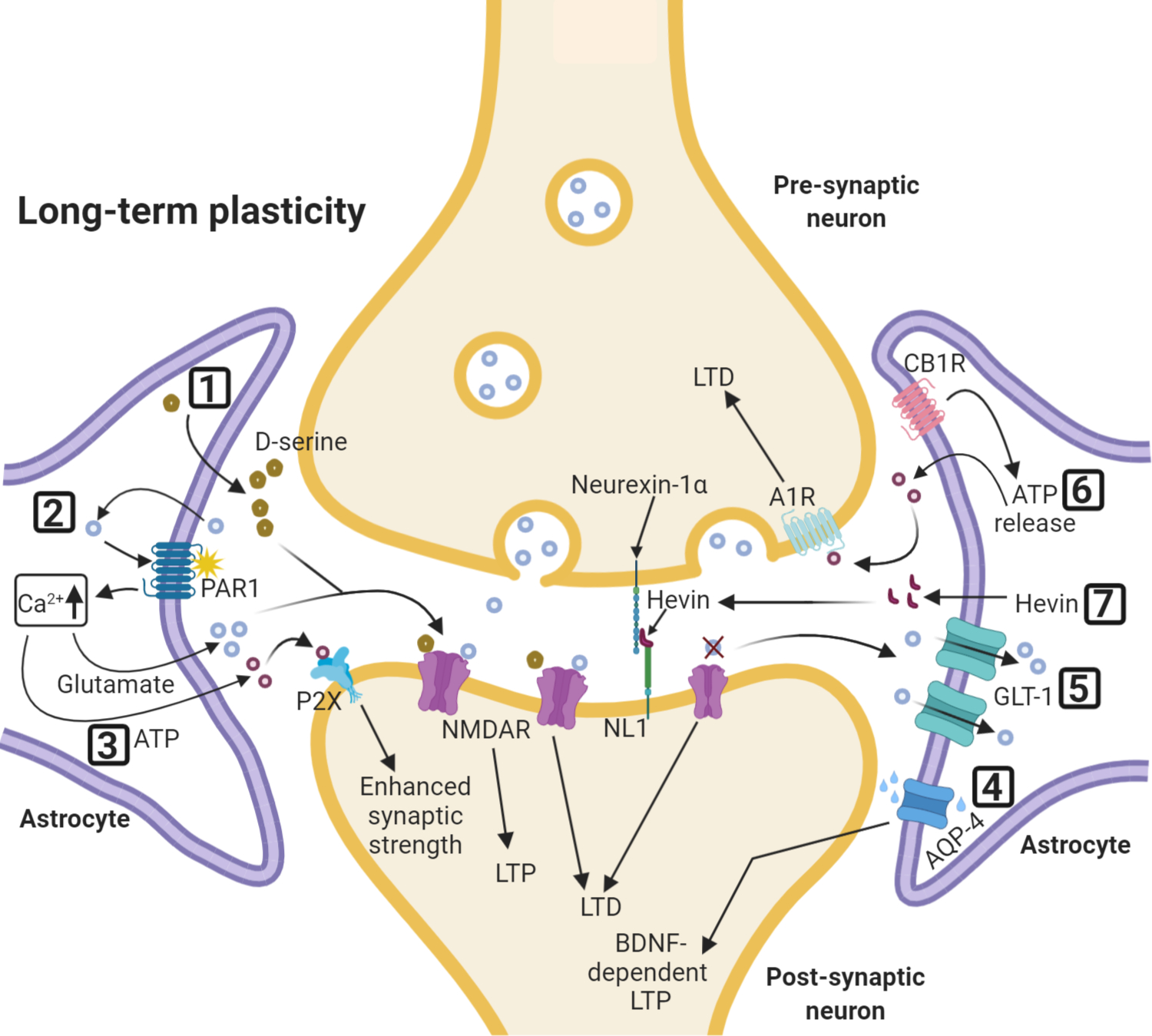

As outlined, release of gliotransmitters from astrocytes occurs upon a rise in intracellular Ca2+. While the exact mechanism of release is a matter of debate, several molecules have been implicated in regulating long-term plasticity including D-serine, glutamate and ATP/adenosine (see Figure 2 for a schematic of pathways).

Figure 2: Astrocytes and long-term synaptic plasticity.

Selected effects of astrocytic regulation of synaptic long-term plasticity. (1) D-serine released by astrocytes enhances NMDAR-mediated LTP. Exogenous D-serine can also affect NMDAR-mediated LTD. (2) Activation of astrocytic protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1) leads to a rise in intracellular Ca2+, releasing glutamate from astrocytes which then binds to neuronal NMDARs. (3) ATP enhances synaptic strength by activating neuronal postsynaptic P2X purinergic receptors. (4) AQP-4 regulates brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)- dependent LTP. (5) GLT-1 glutamate uptake regulates expression of spike timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), both potentiation and depression. (6) CB1R-mediated astrocyte activation leads to the depression of excitatory synapses through A1 adenosine receptors. (7) Astrocyte-secreted Hevin, by linking neurexin-1α and NL1 is necessary for proper expression of ocular dominance plasticity during the visual critical period.

Release of the NMDAR co-agonist D-serine from astrocytes has been extensively studied. For example, astrocyte-derived D-serine enhances NMDAR-mediated LTP in acute slices of adult mouse CA1 (Henneberger et al., 2010). Using juvenile and adult rat hippocampal and prefrontal cortex acute slices, researchers also demonstrated that astrocyte-released D-serine can gate NMDAR-mediated LTP (Yang et al., 2003; Fossat et al., 2012). In addition to potentiating synaptic transmission, experiments in juvenile rats have demonstrated that exogenous D-serine can also mediate NMDAR-mediated LTD, and improve spatial memory retrieval in the Morris water maze (Zhang et al., 2008). In vivo work done in the adult mouse has also demonstrated the role of astrocytic D-serine release in regulating plasticity in the barrel cortex (Takata et al., 2011). Stimulating whiskers and the cholinergic input to the barrel cortex simultaneously results in a potentiation of the whisker-evoked local field potential, which is dependent on astrocytic Ca2+ signaling and consequent D-serine release (Takata et al., 2011). In the adult mouse hippocampus, activation of astrocytes by the Gq-coupled designer receptor exclusively activated by designer drugs (DREADD) hM3Dq induces de novo potentiation of the Schaffer collateral pathway onto CA1 neurons, and this is mediated by astrocytic release of D-serine (Adamsky et al., 2018). Moreover, this astrocytic activation can lead to enhanced spatial and contextual memory as measured by T-maze, open field, and contextual fear conditioning tasks (Adamsky et al., 2018). In short, endogenous D-serine released from astrocytes is critical in regulating NMDAR-mediated LTP and memory.

Glutamate release from astrocytes can also enhance LTP. In vitro studies in juvenile mouse hippocampal slices and cultured rat astrocytes demonstrated that activation of astrocytic protease activated receptor 1 (PAR1) leads to a rise in intracellular Ca2+, releasing glutamate from astrocytes which then binds to neuronal NMDARs (Lee et al., 2007). This results in enhanced synaptic NMDAR-mediated currents. In adult mouse hippocampal slices, this released glutamate also increased the magnitude of theta burst stimulation-induced LTP (Park et al., 2015).

ATP/adenosine release from astrocytes is implicated in multiple forms of long-term plasticity in multiple brain areas. ATP scales up quantal amplitude at glutamatergic synapses in the juvenile mouse hypothalamus by activating neuronal postsynaptic P2X purinergic receptors (Gordon et al., 2009). In the juvenile rat hypothalamus, astrocyte-derived ATP can switch the direction of plasticity at GABA synapses from LTD to LTP by acting on presynaptic P2X receptors to enhance presynaptic activation and prolong GABA release (Crosby et al., 2018). In the central amygdala of juvenile mice, cannabinoid receptor type 1 (CB1R)-mediated astrocyte activation and release of ATP/adenosine can lead to either the depression or enhancement of synaptic responses. This is by adenosine depressing excitatory synapses from the basolateral amygdala through A1 adenosine receptors but enhancing inhibitory synapses from the lateral central amygdala through A2A receptors as measured by a decrease or increase, respectively, in release probability. The combined effect is that astrocyte activation decreases the firing rate output of central amygdala neurons resulting in impaired fear conditioning in adult mice (Martin-Fernandez et al., 2017). Furthermore, experiments done in culture demonstrated a critical role of astrocytic ATP release in maintaining structural long-term plasticity and LTP in primary hippocampal cells and acute slices (Jung et al., 2012). Primary cells treated with Aβ42 lose dendritic spines and Aβ42 leads to a decrease in hippocampal LTP, but Aβ42 stimulated ATP release from astrocytes which was protective in maintaining structural plasticity and LTP (Jung et al., 2012). Thus, astrocytes release a number of molecules that are able to interact influence synaptic strength and plasticity.

The role of astrocyte homeostatic functions in long-term plasticity

A number of essential astrocyte homeostatic functions are also regulated by neuronal activity and have the potential to impact on synaptic strength and plasticity.

A fundamental role of astrocytes is water regulation; this function has also been implicated in the regulation of long-term plasticity. Aquaporin-4 (AQP-4) is a membrane-bound water channel and is enriched in astrocytes (Hubbard, Szu and Binder, 2018). Studies in the hippocampus and amygdala have implicated AQP-4 in synaptic long-term plasticity and learning and memory (Szu and Binder, 2016). For example, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)- dependent LTP is impaired in the hippocampi of adult AQP-4 knockout mice (Skucas et al., 2011). Additionally, AQP-4 knockout mice aged 1.5 – 2 months display impaired BDNF-independent LTP in the hippocampus and impaired memory formation (Yang et al., 2013).

Astrocytes play a critical role in uptake of synaptically-released glutamate, which is essential for proper expression of long-term plasticity within neural circuits (Valtcheva and Venance, 2019). For example, GLT-1 plays a crucial role in spike timing-dependent plasticity (STDP) in MSNs of the rat striatum; either blocking or overexpressing GLT-1 in juvenile rats (P18–42) impairs the expression of STDP, both potentiation and depression (Valtcheva and Venance, 2016). Inhibition of astrocytic GLT-1 leads to an impaired expression of late LTP in juvenile rat hippocampal CA1 slices (Pita-Almenar et al., 2012), while up-regulation of GLT-1 functions leads to a decrease in LTD at mossy fiber-CA3 synapses in adult rats and juvenile mice (Omrani et al., 2009). Additionally, juvenile (P16–25) mice lacking one of the main astrocytic gap junction proteins, connexin 30, have reduced excitatory synaptic strength and deficits in LTP in CA1 and contextual fear conditioning impairments; this is caused by an increased invasion of the synaptic cleft by astrocytic processes, resulting in increased glutamate uptake (Pannasch et al., 2014).

Astrocytes also provide metabolic support to neurons and can consequently regulate long-term plasticity and memory formation. For example, in the adult rat hippocampus, inhibitory avoidance training results in glycogenolysis-dependent lactate release from astrocytes; this lactate is essential for LTP and memory formation (Suzuki et al., 2011). Additionally, lactate supplied to neurons from astrocytes can potentiate NMDAR-mediated EPSCs and Ca2+ responses; this can lead to the expression of plasticity genes in cultured mouse neurons and adult in vivo sensory- motor cortex (Yang et al., 2014). The link between lactate shuttling and metabolic coupling in neurons and astrocytes and long-term plasticity and memory has been extensively described in Steinman, Gao and Alberini, 2016 and Alberini et al., 2018. The homeostatic and maintenance roles of astrocytes are critical for the maintenance and proper regulation of long-term synaptic plasticity and memory.

Other roles of astrocytes in long-term plasticity

Synapse-regulating proteins secreted by astrocytes have been implicated in experience-dependent plasticity. For example, astrocyte-secreted Hevin not only leads to the formation of structural thalamocortical synapses in the developing mouse visual cortex by linking neurexin-1α and Neuroligin 1 (Kucukdereli et al., 2011; Singh et al., 2016), but also is necessary for proper expression of ocular dominance plasticity during the visual critical period (Singh et al., 2016). Additionally, astrocyte-secreted chordin-like 1 is required for synapse maturation in the mouse visual cortex by the recruitment of GluA2-containing AMPARs to the synapse (Blanco-Suarez et al., 2018). In chordin-like 1 knockout mice, ocular dominance plasticity during the critical period (P28) is increased and persists into adulthood (4 months), suggesting that chordin-like 1 acts to restrict plasticity by inducing the maturation of synapses (Blanco-Suarez et al., 2018). In the adult mouse striatum, chemogenetic activation of astrocytes leads to hyperactivity and decreased attention. Upregulation of astrocytic thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) expression, a factor that promotes structural synapse formation (Christopherson et al., 2005; Eroglu et al., 2009; Allen and Eroglu, 2017), was necessary for the increased corticostriatal excitatory transmission, increased striatal firing rates, and increased excitatory synapses, showing that astrocytes can modulate striatal circuits and behavioral patterns (Nagai et al., 2019).

Astrocytes can also play a role in stimulus-specific long-term plasticity. In juvenile and adult mice, stimulus-specific potentiation of neuronal responses in the visual cortex is dependent on cholinergic input from the nucleus basalis (Chen et al., 2012). This cholinergic input directly acts on astrocytes by activating muscarinic acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) and causing Ca2+ elevations in astrocytes. The stimulus-specific potentiation of neural responses is impaired in IP3R2 knockout mice, which have reductions in astrocytic intracellular Ca2+ signals, as measured by in vivo electrophysiology (Chen et al., 2012).

Long-term plasticity of synaptic transmission may also involve changes in the structural relationship between neuronal synapses and astrocytic processes. In the lateral amygdala of adult rats, fear conditioning leads to a transient increase in synapses lacking astrocyte processes as examined by serial section transmission EM (Ostroff et al., 2014). In juvenile to adult (4–8 weeks) mouse hippocampal slices, LTP induces increased motility of astrocytic processes, while in the somatosensory cortex in vivo, certain sensory stimuli also induced similar motility (Perez-Alvarez et al., 2014). Additionally, while the role of sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling has been well-characterized in terms of neuronal structural development, more recent studies have found a role of Shh in astrocytic process elaboration (Ugbode et al., 2017; Cheng, Fleming and Chiang, 2018; Hill et al., 2019). This astrocytic Shh is essential for the turnover of dendritic spines on the apical dendrites of cortical layer V juvenile (P21) mouse neurons (Hill et al., 2019). Other mechanisms of regulating structural plasticity by astrocytes have also been implicated in synaptic plasticity. For example, astrocytes can actively phagocytose synapses via the multiple EGF like domains 10 (MEGF10) and MER proto-oncogene, tyrosine kinase (MERTK) pathways. This process is triggered by neuronal activity and is required for proper formation of retinogeniculate pathways in developing mouse brains and for synapse elimination in adult circuits (Chung et al., 2013).

Finally, transcriptional control of astrocytic gene programs has been implicated in synaptic plasticity. For example, the astrocyte transcriptome can be regulated by neuronal activity; Hrvatin et al. demonstrated that after a period of dark rearing in adult mice, a 4 hour light exposure induces transcriptional changes in astrocytes in the visual cortex that suggest a role in structural remodeling, as many of these differentially regulated genes are components of the extracellular matrix or interact with it (Hrvatin et al., 2018). Furthermore, in mouse adult hippocampus, a conditional deletion of the astrocyte-enriched transcription factor nuclear factor I-A (NFI-A) in astrocytes reduces LTP in CA1 slices via a reduction in astrocytic Ca2+ signaling (Yu-Szu Huang et al., 2020).

These experiments demonstrate the active role of astrocytes in regulating synaptic plasticity and highlight the complexity of how circuit activity in the brain is regulated. More recent in vivo studies involving astrocytes are using some of the tools originally developed to study neurons in order to elucidate novel ways in which astrocytes can participate in the modulation of synaptic plasticity. However, there is still a great need for astrocyte-specific tools to better address the role of these glial cells in orchestrating synaptic plasticity.

MICROGLIA

Microglia properties and functions

In mice, microglia originate from erythromyeloid progenitors in the yolk sac at embryonic day 7.25 and migrate into the brain where they finish differentiation (Hammond, Robinton and Stevens, 2018). Once microglia enter the brain, various critical genes are upregulated that allow microglia to further differentiate; these include transforming growth factor beta (Tgf-β), Spi-1 proto-oncogene (PU.1), and interferon regulatory factor 8 (Irf8) (Kierdorf et al., 2013; Butovsky et al., 2014). Microglia have numerous immune receptors including pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) to detect pathogen or tissue-damage-associated molecular patterns; these include receptors for nucleic acids and C-type lectin receptors (Colonna and Butovsky, 2017). They also express an array of receptors to facilitate the phagocytosis or endocytosis of apoptotic cells, protein aggregates, and lipoprotein particles, as well as an array of chemokine, cytokine, and immunoglobulin superfamily receptors (such as TREM2- triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2).

Microglia can respond to changes in neural activation with morphological or location changes because they express many receptors for neurotransmitters and neuropeptides. These include glutamate receptors, purinergic receptors for ATP, adenosine receptors, and a host of others (Gottlieb and Matute, 1997; Helmut et al., 2011; Liu, Leak and Hu, 2016). These receptors enable microglia to survey neuronal activity and to regulate it by modifying synapse elimination and plasticity. These receptors can also modulate the release of inflammatory cytokines which has a direct impact on neuroinflammation. Activated microglia become amoeboid or rod-shaped and respond to large lesions, strong inflammatory stimuli, or excitotoxicity (Hong, Dissing-Olesen and Stevens, 2016; Colonna and Butovsky, 2017). Resting microglia are typically ramified with numerous processes; however, these processes are still dynamic and respond to local changes in neural activity or small lesions (Nimmerjahn, Kirchhoff and Helmchen, 2005; Tremblay, Lowery and Majewska, 2010). Directly relevant to this review, microglia processes can then phagocytose spines or synapses to regulate neural activity and synaptic plasticity (Hammond, Robinton and Stevens, 2018). Whether microglia engulf the pre- or post-synaptic site versus the entire synapse (or both) remains unclear. In this review, we will discuss the existing evidence for microglial phagocytosis of synapses or synapse components.

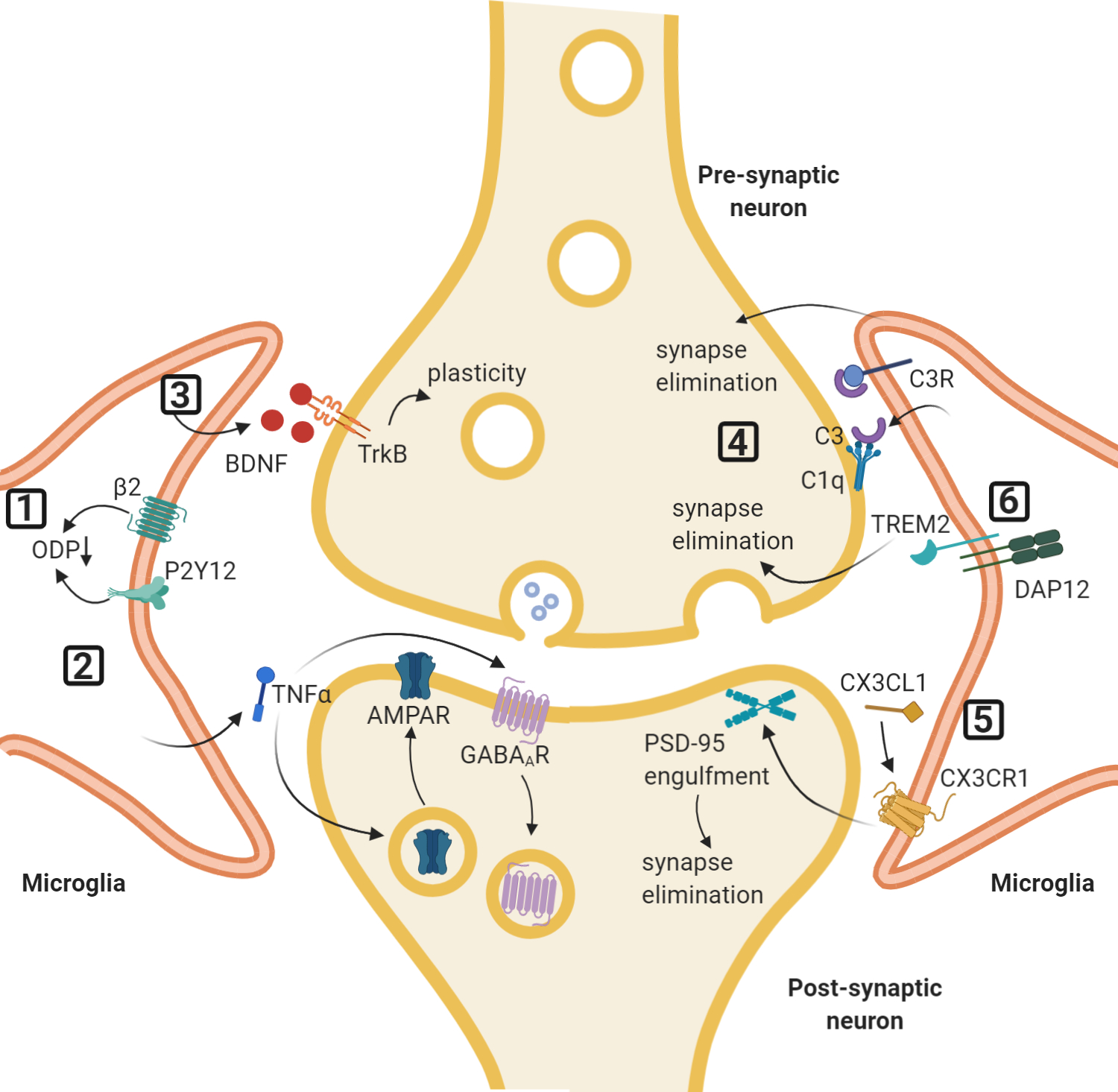

Neurotransmitter and neuromodulator receptors on microglia and plasticity

Microglia have an array of neurotransmitter and neuromodulator receptors used to sense neural and synaptic activity, and then in turn modulate synaptic plasticity by various mechanisms including a release of cytokines, neurotrophic factors, and phagocytosis (see Figure 3). For example, in the mouse visual cortex, non-activated microglia express the Gi/o-coupled P2Y12 purinergic receptor. Monocular deprivation during the visual critical period alters microglial morphology, process motility, and phagocytotic activity (Sipe et al., 2016). Knocking out the P2Y12 receptor in microglia results in a reduction in ramification and process motility immediately following monocular deprivation and a consequent decrease in ocular dominance plasticity (Sipe et al., 2016), demonstrating the role of purinergic signaling onto microglia in promoting visual experience-dependent synaptic plasticity. Microglia in the mouse visual cortex also express β2-adrenergic receptors, which play a role in surveillance and synaptic plasticity (Stowell et al., 2019). 2-photon imaging of microglia in both anesthetized and awake adult mice showed an increase in surveillance in the anesthetized state; during the awake state, the inhibition of microglial surveillance reflected an increase in β2-adrenergic signaling (Stowell et al., 2019). Furthermore, activation of β2-adrenergic receptors on microglia impaired ocular dominance plasticity during the critical period (Stowell et al., 2019). The different outcomes of these two studies as a result of the inhibition of different neurotransmitter receptors on microglia highlights the distinct role of these modulatory pathways in regulating the effects of microglia on synaptic plasticity.

Figure 3: The role of microglia in synaptic plasticity.

Selected pathways of microglial involvement in synaptic plasticity. (1) Activation of the purinergic P2Y12 receptor or inhibition of the β-adrenergic receptor on microglia promotes ocular dominance plasticity (ODP) after monocular deprivation. (2) Release of TNFα from microglia can lead to the exocytosis of AMPARs and endocytosis of GABAA receptors at the postsynaptic membrane. (3) Secretion of BDNF from microglia can promote synaptic plasticity and motor learning. (4) The classical complement cascade, in which soluble C1q initiates the pathway, with microglial-secreted C3 binding to C3 receptors on microglia. This leads to synapse elimination and facilitates memory erasure. (5) CX3CL1 derived from neurons can bind to microglial CX3CR1 to initiate synaptic elimination and promote barrel cortex plasticity after whisker lesioning. (6) TREM2 on microglia is involved in the phagocytosis of synapses.

Cytokines and neurotrophic factors and plasticity

Microglia can release cytokines in response to neuronal activity. TNFα and other cytokines such as interleukin 6 and 1B can affect neuronal excitability by modulating the activity of many types of voltage-gated channels and receptors (see Vezzani & Viviani, 2015 for a review). TNFα from microglia can regulate synaptic scaling and homeostasis; in vitro rat hippocampal studies demonstrated that TNFα increased the exocytosis of GluA2-lacking AMPARs to the postsynaptic membrane, but also the endocytosis of GABAA receptors (Stellwagen et al., 2005). Furthermore, chronically blocking activity in hippocampal cultures via TTX led to an increase in miniature EPSCs, mediated by a TNFα- induced increase in surface AMPARs (Stellwagen and Malenka, 2006). In acute slice preparations of juvenile mouse dentate gyrus, microglial TNFα was necessary for astrocytic glutamate release following P2Y1R activation. This astrocytic glutamate binds to presynaptic NMDARs, increasing EPSC frequency (Santello, Bezzi and Volterra, 2011). Bath-application of lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an inflammatory stimulus, increases AMPAR-mediated EPSC frequency in CA1 pyramidal neurons in a microglia-dependent manner (Pascual et al., 2012). In this context microglia release ATP which binds to P2Y1Rs on astrocytes, which then in turn release glutamate that binds to mGluR5s on the presynaptic membrane resulting in an increase in EPSC frequency; this pathway is TNFα-independent (Pascual et al., 2012).

Microglia are also a source of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), one of whose many roles is the regulation of synaptic plasticity. The secretion of BDNF from microglia is critical for learning-dependent synaptic plasticity in motor cortex after the acquisition of motor tasks. Ablation of diphtheria toxin (DT) receptor-expressing microglia with DT impaired motor learning and reduced the associated formation of excitatory synapses as visualized by in vivo 2-photon imaging in ~P30 mice (Parkhurst et al., 2013). The role of microglia in this context is mediated by BDNF, which increases neuronal tropomyosin-related kinase receptor (TrkB) phosphorylation and promotes experience-dependent synaptic plasticity (Parkhurst et al., 2013). Microglia can also induce filopodia formation in developing mouse somatosensory cortex; microglial processes contacting the dendrite can induce Ca2+ elevations and actin accumulation prior to filopodia extension (Miyamoto et al., 2016). Ablating microglia also reduces the number of functional synapses in juvenile mice (Miyamoto et al., 2016).

Synaptic pruning

Phagocytosis of synaptic components by microglia is one of the most well-studied ways in which they regulate neuronal activity and synaptic plasticity. Electron microscopy and high-resolution in vivo imaging have identified both pre- and post-synaptic components inside lysosomes in microglia (Tremblay, Lowery and Majewska, 2010; Schafer et al., 2012). One of the main pathways responsible for microglia-mediated phagocytosis is the classical complement cascade; complement component 1q (C1q) initiates the pathway resulting in C3 being localized to neuronal membranes, binding to complement receptor 3 (CR3) on microglia, and the target synapse being phagocytosed (Hammond, Robinton and Stevens, 2018). During development of the mouse visual system, immature synapses are tagged by the complement cascade molecules and eliminated by CR3- expressing microglia (Stevens et al., 2007). Additionally, the complement cascade-mediated phagocytosis of presynaptic components of the retinogeniculate pathway depends on neuronal activity; selectively weakening input from one eye during early development increases engulfment of those afferent terminals by microglia (Schafer et al., 2012). Furthermore, depletion of microglia or genetically inhibiting the complement pathway in adult mouse dentate gyrus impairs memory erasure and forgetting in a contextual fear memory task (Wang et al., 2020). In CA1 slices of mice and rats subjected to both hypoxia and LPS, LTD was observed and was dependent on microglial CR3 (J. Zhang et al., 2014). This LTD is dependent on activation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which leads to activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) and endocytosis of AMPARs (Zhang et al., 2014). However, complement-cascade mediated phagocytosis is not merely a developmental feature; depletion of microglia or genetically inhibiting the complement pathway in adult mouse dentate gyrus impairs memory erasure and forgetting in a contextual fear memory task (Wang et al., 2020). This synaptic weakening and LTD may precede microglia-mediated synaptic pruning via phagocytosis.

Synaptic refinement and pruning can also be mediated by the fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) on microglia and its neuronal partner, fractalkine (CX3CL1). In mouse somatosensory cortex, specifically barrel cortex, CX3CR1 signaling in microglia is necessary for the refinement of early postnatal thalamocortical inputs, the formation of whisker “barrels,” and the maturation of postsynaptic glutamatergic receptors (Hoshiko et al., 2012). Microglial CX3CR1 is required for synaptic pruning in mouse hippocampal slices during synaptic maturation. Using super-resolution light microscopy and electron microscopy, the authors demonstrated that microglia engulfed PSD95-immunoreactive puncta, but this engulfment was impaired in CX3CR1-KO mice (Paolicelli et al., 2011). CX3RCR1 is also required for microglia- mediated synapse elimination following whisker lesioning (Gunner et al., 2019). Fractalkine (CX3CL1) is derived from cortical neurons and A Disintegrin and metalloproteinase domain-containing protein 10 (ADAM10), which cleaves CX3CL1 into its secreted form, is upregulated in layer IV neurons and microglia after whisker lesioning, highlighting the importance of neuron-to-microglia communication (Gunner et al., 2019). TREM2 is implicated in phagocytosis of excessive synapses in CA1 of mouse hippocampus during development; TREM2 KO mice have increased excitatory synapse number and sociability impairments as measured by the marble burying, self-grooming, and juvenile play tasks (Filipello et al., 2018). However, these mice do not have Morris water maze spatial navigation or social novelty paradigm task impairments (Filipello et al., 2018).

Highlighting a different mechanism of synapse elimination, light sheet fluorescence microscopy and correlative light and electron microscopy studies of organotypic hippocampal cultures saw no evidence for phagocytosis of postsynaptic structures (Weinhard et al., 2018). The authors did report a trogocytosis or “nibbling” of presynaptic structures in a complement pathway-independent manner; furthermore, the contact of a microglial process to spine heads led to the formation of spine head filopodia, a potential consequence of synaptic plasticity (Weinhard et al., 2018). Microglia-regulated synapse remodeling can also involve structural changes of the extracellular matrix (ECM). In mice that lack matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9), ocular dominance plasticity was reduced and the turnover of dendritic spines was increased during the critical period (Kelly et al., 2015). In these KO mice, microglia inclusions and the extracellular space around microglial processes were increased, suggesting that microglia can mediate the effects of MMP9 (Kelly et al., 2015). After environmental enrichment, adult hippocampal neurons expressing interleukin-33 (IL-33) instruct microglia to engulf the ECM and this induces the formation of a spine head filopodia (Nguyen et al., 2020). IL-33 signaling also contributes to remote fear memory precision (Nguyen et al., 2020), thus demonstrating the importance of microglia in regulating experience-dependent plasticity even in the adult brain. Overall microglial-mediated synapse surveillance and elimination is important for maintaining proper circuit development and function.

OLIGODENDROCYTES

Oligodendrocyte properties and functions

In the rodent forebrain, the first wave of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) originates from the medial ganglionic eminence and the anterior entopeduncular area; the second wave originates from the lateral and caudal ganglionic eminences; the third wave originates from the postnatal cortex (Bradl and Lassmann, 2010). These OPCs then give rise to myelinating oligodendrocytes. In the CNS, the physical properties of myelin can greatly affect the conduction of action potentials along the axon (Ronzano et al., 2020). Myelin is made up of multiple membrane layers and provides electrical insulation and enables metabolic support of the axon. Myelin also has gaps in the sheaths called nodes of Ranvier where ion channels are located; these allow fast saltatory conduction of action potentials. The myelinated axon segment between nodes are called internodes, and their length can vary from axon to axon (Ronzano et al., 2020). Oligodendrocytes selectively wrap axons with a diameter greater than 0.2 um, and each oligodendrocyte can generate between 20 and 60 myelinating processes (Bradl and Lassmann, 2010; Simons and Nave, 2016).

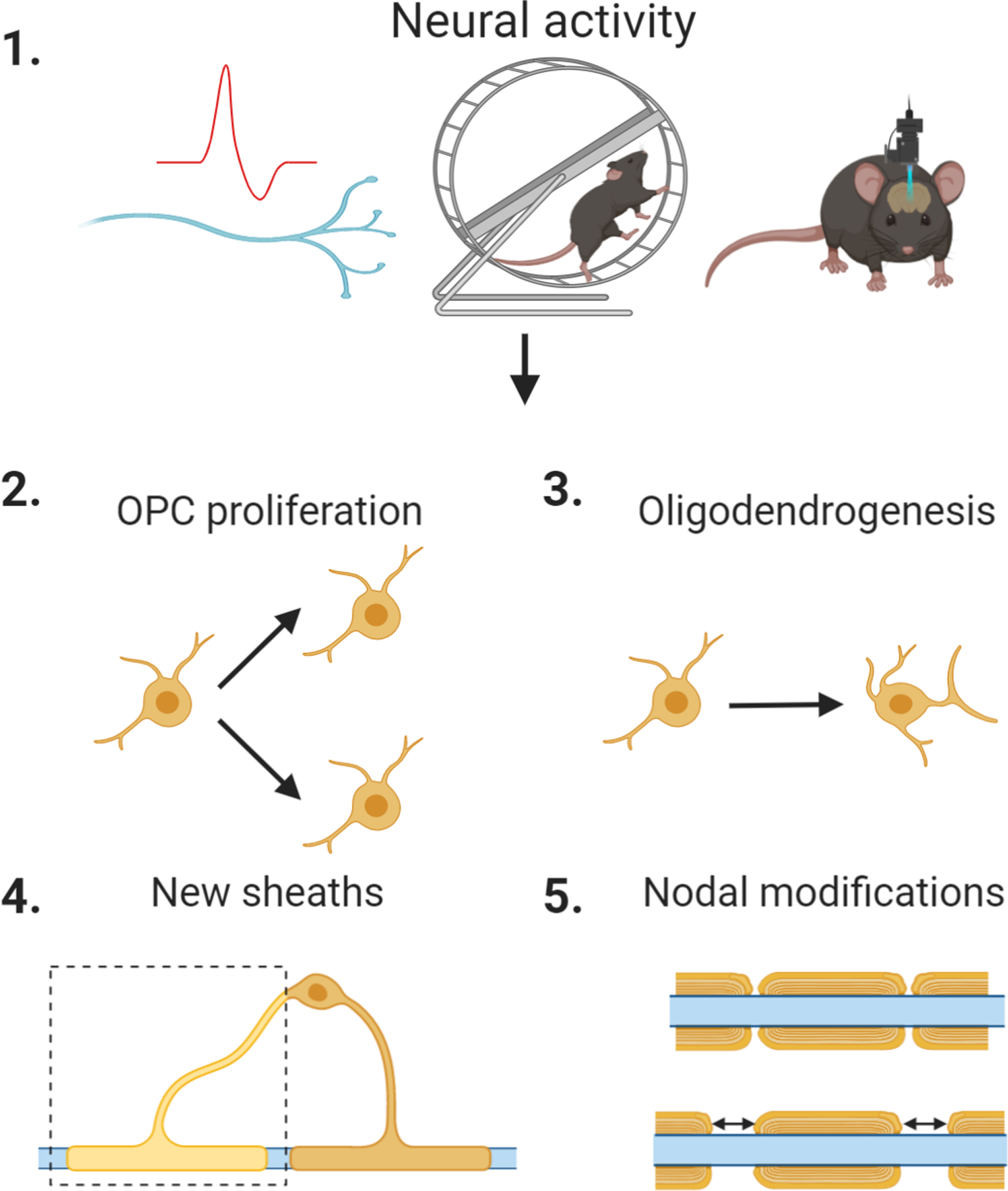

Activity-dependent plasticity and myelination

Neuronal activity is important for oligodendrogenesis and the proper formation and refinement of myelin in rodents (Gyllensten and Malmfors, 1963; Demerens et al., 1996; Korrell et al., 2019; Ronzano et al., 2020). OPCs receive glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses from neurons to sense neuronal activity (Bergles et al., 2000; Lin and Bergles, 2004). For example, in the maturing auditory brainstem, a subset of pre-myelinating oligodendrocytes can fire Nav1.2- driven depolarizations in response to glutamatergic input from neighboring neurons; deleting Nav1.2 channels impairs myelination (Berret et al., 2017). In zebrafish, activity-dependent changes in myelination occur via the release of axonal vesicles from active axons (Mensch et al., 2015; Wake et al., 2015; Etxeberria et al., 2016), but mainly affect increased wrapping of axons and not initiation of myelination (Hines et al., 2015). In the rodent CNS, actin disassembly in the oligodendrocyte process is required for the initiation of wrapping (Zuchero et al., 2015). It follows that oligodendrogenesis and myelin plasticity can also regulate neuronal circuit activity and learning.

OPCs persist into adulthood and are capable of proliferating and subsequently differentiating into myelinating oligodendrocytes throughout life. Thus, it stands to reason that adult oligodendrogenesis and myelin plasticity may be influenced in an experience-dependent manner, and in turn modulate neuronal plasticity (Figure 4). Myelin plasticity in adulthood is associated with oligodendrogenesis, altering the thickness of myelin sheaths, and changing nodal properties (Ronzano et al., 2020). Plugging the ear canals of juvenile mice results in a decrease in trapezoid body axon diameter and myelin thickness, while plugging during early adulthood results in a reduction in myelin thickness, showing that ongoing activity is required to maintain myelin thickness (Sinclair et al., 2017). Computational modeling and experimental studies have demonstrated that action potential timing in gerbil auditory brainstem axons is controlled by the properties of Ranvier nodes and internodes (Ford et al., 2015). Axons from neurons that respond to low-frequency sounds have larger diameters with shorter internodes; additionally, along the distal axon, the internode length decreases and the width of the Ranvier node increased to ensure the precise timing of the action potential arriving at the calyx of Held synapse (Ford et al., 2015). Modeling studies also suggest that changes in the conduction velocity of axons, which can be modulated by myelin thickness or node structure, can result in drastic changes in how neuronal activity is synchronized (Pajevic, Basser and Fields, 2014; Sinclair et al., 2017), which has important implications for synaptic plasticity and memory formation and consolidation (Abel et al., 2013; Klinzing, Niethard and Born, 2019; Puentes-Mestril et al., 2019).

Figure 4. Oligodendrocytes, myelin plasticity, and neuronal plasticity.

(1) Neuronal activity including, but not limited to, action potential firing, motor task training, and optogenetic stimulation (left to right) can induce changes in myelination such as (2) proliferation of new OPCs, (3) maturation of OPCs into myelinating oligodendrocytes, (4) formation of new sheaths or thickening of existing sheaths, and (5) changes to the internode segments or nodes.

Role of myelination in memory and learning

Experimental studies examining the function of myelin in brain oscillations and memory formation and consolidation demonstrate a critical role for active and de novo myelination. Adult mice trained to navigate a Morris water maze have increased oligodendrogenesis in the cortex and white matter tracts (Steadman et al., 2020). Furthermore, impairing de novo myelination results in deficits in memory consolidation and learning-induced ripple-spindle coupling in the hippocampus (Steadman et al., 2020). Additionally, adult mice that were trained to run on a wheel with irregularly spaced rungs had increased oligodendrogenesis in the CNS white matter, while genetically knocking down new myelination impaired learning of the complex wheel task (McKenzie et al., 2014; Xiao et al., 2016). Optogenetically stimulating neurons in the premotor cortex leads to increased oligodendrogenesis and myelination of deep layer axons; this increased oligodendrogenesis and myelination is critical for improved motor performance during a gait test (Gibson et al., 2014). The important role of activity-regulated myelination in non-motor cognitive tasks was also highlighted by using a mouse model of chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment, induced by methotrexate (MTX) treatment (Geraghty et al., 2019). MTX decreases expression of BDNF in microglia, which would normally bind to TrkB on OPCs. This decrease in BDNF results in decreased activity-regulated myelination and an impairment in a novel object recognition task (Geraghty et al., 2019).

Furthermore, contextual fear learning increases oligodendrogenesis and new myelin formation in the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) and is required for fear memory recall (Pan et al., 2020). In adult mice, cuprizone-induced demyelination and oligodendrocyte death results in hyperexcitability in the motor cortex and impairments in motor learning (Bacmeister et al., 2020). Motor learning after demyelination only occurs after an initial period of partial remyelination and restoration of neuronal function and can serve to further enhance oligodendrogenesis and the ability of surviving oligodendrocytes to generate new myelin sheaths (Bacmeister et al., 2020). Thus, after brain injury in the adult rodent, the plasticity of myelin is important for the restoration of neuronal circuit function. The plasticity and on-going refinement of myelin in the brain is important for retaining circuit flexibility in response to learning or injury. Changing the properties of myelin has profound implications for the timing of neuronal activity and consequently for synaptic plasticity.

CONCLUSION

In this review we discuss the roles of three major classes of glial cells in regulating neuronal plasticity. Astrocytes can modulate both short-term and long-term synaptic plasticity via an array of mechanisms including gliotransmission, structural plasticity, spine elimination, and neurotransmitter and ion uptake. Microglia constantly survey synapses with dynamic processes and can promote synapse turnover and homeostasis. Oligodendrocytes contribute to activity-dependent learning via new myelination or modifications of myelin properties, thus changing circuit activity. However, these cells not only communicate with neurons and modulate synaptic plasticity, but they can also interact with each other. For example, astrocytes can communicate with each other via gap junctions, helping to coordinate their activity across an entire circuit (Landis and Reese, no date; Massa and Mugnaini, 1985). There is also evidence for gap junctions among oligodendrocytes (Dermietzel, 1974) and between oligodendrocytes and astrocytes (Masa and Mugnaini, 1982). In fact, the role of astrocytes and microglia in regulating OPCs and myelination has been well-established (see Clemente et al., 2013 for a review). Astrocytes can also promote microglial-mediated synapse engulfment and maturation in the developing visual thalamus via secretion of interleukin 33 (Vainchtein et al., 2018). Additionally, glia-glia communication is critical for regulating neuroinflammation (see Skaper et al., 2018 for a review). Thus, moving forward it will be important not only to understand how glia and neurons communicate with each other to regulate different forms of synaptic plasticity but also how glia interact with each other.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Non-neuronal glial cells regulate synaptic plasticity through multiple mechanisms

Astrocytes and microglia regulate synapse number, function and stability

Oligodendrocytes regulate network level signaling

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank members of the Allen lab for feedback on the manuscript. Funding support for the Allen lab comes from the Pew Foundation, CZI NDCN and NIH NINDS NS105742. Figures were made with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

Declarations of interest: none

REFERENCES

- Abel T et al. (2013) ‘Sleep, plasticity and memory from molecules to whole-brain networks’, Current Biology. Elsevier, 23(17), pp. R774–R788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamsky A et al. (2018) ‘Astrocytic Activation Generates De Novo Neuronal Potentiation and Memory Enhancement’, Cell. Cell Press, 174(1), pp. 59–71.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A et al. (2017) ‘Transient Opening of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Induces Microdomain Calcium Transients in Astrocyte Processes’, Neuron. Elsevier, 93(3), pp. 587–605.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agulhon C et al. (2008) ‘What Is the Role of Astrocyte Calcium in Neurophysiology?’, Neuron, 59(6), pp. 932–946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberini CM et al. (2018) ‘Astrocyte glycogen and lactate: New insights into learning and memory mechanisms’, GLIA [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ et al. (2012) ‘Astrocyte glypicans 4 and 6 promote formation of excitatory synapses via GluA1 AMPA receptors’, Nature [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ (2014) ‘Astrocyte Regulation of Synaptic Behavior’, Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 30(1), pp. 439–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ and Barres BA (2005) ‘Signaling between glia and neurons: Focus on synaptic plasticity’, Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 15(5), pp. 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ and Eroglu C (2017) ‘Cell Biology of Astrocyte-Synapse Interactions’, Neuron [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen NJ and Lyons DA (2018) ‘Glia as arquitects of central nervous system formation and function’, Science, 362(6411), pp. 181–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araque A et al. (2014) ‘Gliotransmitters travel in time and space’, Neuron, 81(4), pp. 728–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacmeister CM et al. (2020) ‘Motor learning promotes remyelination via new and surviving oligodendrocytes’, Nature Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazargani N and Attwell D (2016) ‘Astrocyte calcium signaling: The third wave’, Nature Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group, pp. 182–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellot-Saez A et al. (2017) ‘Astrocytic modulation of neuronal excitability through K+ spatial buffering’, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 77, pp. 87–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergles DE et al. (2000) ‘Glutamatergic synapses on oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus’, Nature [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berret E et al. (2017) ‘Oligodendroglial excitability mediated by glutamatergic inputs and Nav1.2 activation’, Nature Communications [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindocci E et al. (2017a) ‘Neuroscience: Three-dimensional Ca2+ imaging advances understanding of astrocyte biology’, Science, 356(6339). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindocci E et al. (2017b) ‘Neuroscience: Three-dimensional Ca2+ imaging advances understanding of astrocyte biology’, Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science, 356(6339). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Suarez E et al. (2018) ‘Astrocyte-Secreted Chordin-like 1 Drives Synapse Maturation and Limits Plasticity by Increasing Synaptic GluA2 AMPA Receptors’, Neuron. Elsevier Inc, 100(5), pp. 1116–1132.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradl M and Lassmann H (2010) ‘Oligodendrocytes: Biology and pathology’, Acta Neuropathologica, 119(1), pp. 37–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong EA et al. (2002) ‘Protoplasmic astrocytes in CA1 stratum radiatum occupy separate anatomical domains’, Journal of Neuroscience, 22(1), pp. 183–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushong EA, Martone ME and Ellisman MH (2004) ‘Maturation of astrocyte morphology and the establishment of astrocyte domains during postnatal hippocampal development’, International Journal of Developmental Neuroscience, 22(2), pp. 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O et al. (2014) ‘Identification of a unique TGF-β-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia’, Nature Neuroscience, 17(1), pp. 131–143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen N et al. (2012) ‘Nucleus basalis-enabled stimulus-specific plasticity in the visual cortex is mediated by astrocytes’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(41). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng FY, Fleming JT and Chiang C (2018) ‘Bergmann glial Sonic hedgehog signaling activity is required for proper cerebellar cortical expansion and architecture’, Developmental Biology. Elsevier Inc, 440(2), pp. 152–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson KS et al. (2005) ‘Thrombospondins are astrocyte-secreted proteins that promote CNS synaptogenesis’, Cell, 120(3), pp. 421–433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WS et al. (2013) ‘Astrocytes mediate synapse elimination through MEGF10 and MERTK pathways’, Nature. Nature Publishing Group, 504(7480), pp. 394–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citri A and Malenka RC (2008) ‘Synaptic plasticity: Multiple forms, functions, and mechanisms’, Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), pp. 18–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente D et al. (2013) ‘The effect of glia-glia interactions on oligodendrocyte precursor cell biology during development and in demyelinating diseases’, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonna M and Butovsky O (2017) ‘Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration’, Annual Review of Immunology, 35(1), pp. 441–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkrum M et al. (2020) ‘Dopamine-Evoked Synaptic Regulation in the Nucleus Accumbens Requires Astrocyte Activity’, Neuron. Elsevier Inc, 105(6), pp. 1036–1047.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covelo A and Araque A (2018) ‘Neuronal activity determines distinct gliotransmitter release from a single astrocyte’, eLife, 7, pp. 1–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby KM et al. (2018) ‘Cholecystokinin switches the plasticity of gaba synapses in the dorsomedial hypothalamus via astrocytic atp release’, Journal of Neuroscience, 38(40), pp. 8515–8525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt NC (2001) ‘Glutamate uptake’, Progress in Neurobiology, 65(1), pp. 1–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demerens C et al. (1996) ‘Induction of myelination in the central nervous system by electrical activity’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(18), pp. 9887–9892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermietzel R (1974) ‘Junctions in the central nervous system of the cat - III. Gap junctions and membrane-associated orthogonal particle complexes (MOPC) in astrocytic membranes’, Cell and Tissue Research [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F et al. (2013) ‘α1-Adrenergic receptors mediate coordinated Ca2+ signaling of cortical astrocytes in awake, behaving mice’, Cell Calcium. Elsevier Ltd, 54(6), pp. 387–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eroglu Ç et al. (2009) ‘Gabapentin Receptor α2δ−1 Is a Neuronal Thrombospondin Receptor Responsible for Excitatory CNS Synaptogenesis’, Cell, 139(2), pp. 380–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etxeberria A et al. (2016) ‘Dynamic modulation of myelination in response to visual stimuli alters optic nerve conduction velocity’, Journal of Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy-Tselnicker I et al. (2017) ‘Astrocyte-Secreted Glypican 4 Regulates Release of Neuronal Pentraxin 1 from Axons to Induce Functional Synapse Formation’, Neuron. Elsevier Inc, 96(2), pp. 428–445.e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhy-Tselnicker I and Allen NJ (2018) ‘Astrocytes, neurons, synapses: A tripartite view on cortical circuit development’, Neural Development. BioMed Central Ltd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiacco TA and McCarthy KD (2004) ‘Intracellular Astrocyte Calcium Waves In Situ Increase the Frequency of Spontaneous AMPA Receptor Currents in CA1 Pyramidal Neurons’, Journal of Neuroscience, 24(3), pp. 722–732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipello F et al. (2018) ‘The Microglial Innate Immune Receptor TREM2 Is Required for Synapse Elimination and Normal Brain Connectivity’, Immunity. Elsevier Inc, 48(5), pp. 979–991.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MC et al. (2015) ‘Tuning of Ranvier node and internode properties in myelinated axons to adjust action potential timing’, Nature Communications. Nature Publishing Group, 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossat P et al. (2012) ‘Glial D-serine gates NMDA receptors at excitatory synapses in prefrontal cortex’, Cerebral Cortex, 22(3), pp. 595–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraghty AC et al. (2019) ‘Loss of Adaptive Myelination Contributes to Methotrexate Chemotherapy-Related Cognitive Impairment’, Neuron. Cell Press, 103(2), pp. 250–265.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson EM et al. (2014) ‘Neuronal activity promotes oligodendrogenesis and adaptive myelination in the mammalian brain’, Science [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon GRJ et al. (2009) ‘Astrocyte-Mediated Distributed Plasticity at Hypothalamic Glutamate Synapses’, Neuron. Elsevier Ltd, 64(3), pp. 391–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb M and Matute C (1997) ‘Expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunits in glial cells of the hippocampal CA1 area following transient forebrain ischemia’, Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goubard V, Fino E and Venance L (2011) ‘Contribution of astrocytic glutamate and GABA uptake to corticostriatal information processing’, Journal of Physiology, 589(9), pp. 2301–2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunner G et al. (2019) ‘Sensory lesioning induces microglial synapse elimination via ADAM10 and fractalkine signaling’, Nature Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie PB et al. (1999) ‘ATP released from astrocytes mediates glial calcium waves’, Journal of Neuroscience, 19(2), pp. 520–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GYLLENSTEN L and MALMFORS T (1963) ‘Myelinization of the optic nerve and its dependence on visual function--a quantitative investigation in mice.’, Journal of embryology and experimental morphology, 11(March), pp. 255–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond TR, Robinton D and Stevens B (2018) ‘Microglia and the Brain: Complementary Partners in Development and Disease’, Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology, 34(1), pp. 523–544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanse E and Gustafsson B (2001) ‘Paired-pulse plasticity at the single release site level: An experimental and computational study’, Journal of Neuroscience, 21(21), pp. 8362–8369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller JP and Rusakov DA (2017) ‘The nanoworld of the tripartite synapse: Insights from super-resolution microscopy’, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. Frontiers Media S.A [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmut K et al. (2011) ‘Physiology of microglia’, Physiological Reviews, 91(2), pp. 461–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C et al. (2010) ‘Long-term potentiation depends on release of d-serine from astrocytes’, Nature, 463(7278), pp. 232–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herculano-Houzel S (2014) ‘The glia/neuron ratio: How it varies uniformly across brain structures and species and what that means for brain physiology and evolution’, Glia, 62(9), pp. 1377–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L (1965) ‘Possible role of neuroglia [29]’, Nature, 206(4989), pp. 1091–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L and Chen Y (2016) ‘Importance of astrocytes for potassium ion (K+) homeostasis in brain and glial effects of K+ and its transporters on learning’, Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. Elsevier Ltd, 71, pp. 484–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill SA et al. (2019) ‘Sonic hedgehog signaling in astrocytes mediates cell type-specific synaptic organization’, eLife, 8, pp. 1–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillen AEJ, Burbach JPH and Hol EM (2018) ‘Cell adhesion and matricellular support by astrocytes of the tripartite synapse’, Progress in Neurobiology. Elsevier Ltd, pp. 66–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hines JH et al. (2015) ‘Neuronal activity biases axon selection for myelination in vivo’, Nature Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong S, Dissing-Olesen L and Stevens B (2016) ‘New insights on the role of microglia in synaptic pruning in health and disease’, Current Opinion in Neurobiology. Elsevier Ltd, pp. 128–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshiko M et al. (2012) ‘Deficiency of the microglial receptor CX3CR1 impairs postnatal functional development of thalamocortical synapses in the barrel cortex’, Journal of Neuroscience, 32(43), pp. 15106–15111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hrvatin S et al. (2018) ‘Single-Cell Analysis of Experience-Dependent Transcriptomic States in Mouse Visual Cortex HHS Public Access Author manuscript’, Nat Neurosci [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Szu JI and Binder DK (2018) ‘The role of aquaporin-4 in synaptic plasticity, memory and disease’, Brain Research Bulletin. Elsevier Inc, 136, pp. 118–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung ES et al. (2012) ‘Astrocyte-originated ATP protects Aβ 1–42-induced impairment of synaptic plasticity’, Journal of Neuroscience, 32(9), pp. 3081–3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel ER, Dudai Y and Mayford MR (2014) ‘The molecular and systems biology of memory’, Cell. Elsevier Inc, 157(1), pp. 163–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasthuri N et al. (2015) ‘Saturated Reconstruction of a Volume of Neocortex’, Cell [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B and Miledi R (1968) ‘The role of calcium in neuromuscular facilitation’, The Journal of Physiology, 195(2), pp. 481–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly EA et al. (2015) ‘Proteolytic regulation of synaptic plasticity in the mouse primary visual cortex: Analysis of matrix metalloproteinase 9 deficient mice’, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessels HW and Malinow R (2009) ‘Synaptic AMPA Receptor Plasticity and Behavior’, Neuron [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kierdorf K et al. (2013) ‘Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via Pu.1-and Irf8-dependent pathways’, Nature Neuroscience. Nature Publishing Group, 16(3), pp. 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinzing JG, Niethard N and Born J (2019) ‘Mechanisms of systems memory consolidation during sleep’, Nature Neuroscience. Springer US, 22(October). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korrell KV et al. (2019) ‘Differential effect on myelination through abolition of activity-dependent synaptic vesicle release or reduction of overall electrical activity of selected cortical projections in the mouse’, Journal of Anatomy, 235(3), pp. 452–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucukdereli H et al. (2011) ‘Control of excitatory CNS synaptogenesis by astrocyte-secreted proteins hevin and SPARC’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(32). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis DMD and Reese TS (no date) ‘Regional organization of astrocytic membranes in cerebellar cortex’, Neuroscience [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CJ et al. (2007) ‘Astrocytic control of synaptic NMDA receptors’, Journal of Physiology, 581(3), pp. 1057–1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin SC and Bergles DE (2004) ‘Synaptic signaling between GABAergic interneurons and oligodendrocyte precursor cells in the hippocampus’, Nature Neuroscience, 7(1), pp. 24–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind BL et al. (2013) ‘Rapid stimulus-evoked astrocyte Ca2+ elevations and hemodynamic responses in mouse somatosensory cortex in vivo’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(48). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Leak RK and Hu X (2016) ‘Neurotransmitter receptors on microglia’, Stroke and Vascular Neurology, 1(2), pp. 52–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malenka RC and Nicoll RA (1999) ‘Long-term potentiation - A decade of progress?’, Science, 285(5435), pp. 1870–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinow R (2003) ‘AMPA receptor trafficking and long-term potentiation’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 358(1432), pp. 707–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Fernandez M et al. (2017) ‘Synapse-specific astrocyte gating of amygdala-related behavior’, Nature Neuroscience, 20(11), pp. 1540–1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín R et al. (2015) ‘Circuit-specific signaling in astrocyte-neuron networks in basal ganglia pathways’, Science, 349(6249), pp. 730–734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masa PT and Mugnaini E (1982) ‘Cell junctions and intramembrane particles of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes: A freeze-fracture study’, Neuroscience [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massa PT and Mugnaini E (1985) ‘Cell-cell junctional interactions and characteristic plasma membrane features of cultured rat glial cells’, Neuroscience [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie IA et al. (2014) ‘Motor skill learning requires active central myelination’, Science, 346(6207), pp. 318–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensch S et al. (2015) ‘Synaptic vesicle release regulates myelin sheath number of individual oligodendrocytes in vivo’, Nature Neuroscience. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto A et al. (2016) ‘Microglia contact induces synapse formation in developing somatosensory cortex’, Nature Communications [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy-Royal C et al. (2017) ‘Astroglial glutamate transporters in the brain: Regulating neurotransmitter homeostasis and synaptic transmission’, Journal of Neuroscience Research, 95(11), pp. 2140–2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagai J et al. (2019) ‘Hyperactivity with Disrupted Attention by Activation of an Astrocyte Synaptogenic Cue’, Cell [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT et al. (2020) ‘Microglial Remodeling of the Extracellular Matrix Promotes Synapse Plasticity’, Cell. Elsevier Inc, 182(0), pp. 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimmerjahn A, Kirchhoff F and Helmchen F (2005) ‘Resting microglial cells are highly dynamic surveillants of brain parenchyma in vivo’, Neuroforum, 11(3), pp. 95–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Octeau JC et al. (2018) ‘An Optical Neuron-Astrocyte Proximity Assay at Synaptic Distance Scales’, Neuron. Cell Press, 98(1), pp. 49–66.e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omrani A et al. (2009) ‘Up-regulation of GLT-1 severely impairs LTD at mossy fibre-CA3 synapses’, Journal of Physiology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostroff LE et al. (2014) ‘Synapses lacking astrocyte appear in the amygdala during consolidation of pavlovian threat conditioning’, Journal of Comparative Neurology [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsu Y et al. (2015) ‘Calcium dynamics in astrocyte processes during neurovascular coupling’, Nature Neuroscience, 18(2), pp. 210–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajevic S, Basser PJ and Fields RD (2014) ‘Role of myelin plasticity in oscillations and synchrony of neuronal activity’, Neuroscience. Elsevier Ltd, 276, pp. 135–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S et al. (2020) ‘Preservation of a remote fear memory requires new myelin formation’, Nature Neuroscience. Springer US, 23(4), pp. 487–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A et al. (2011) ‘Astrocytes are endogenous regulators of basal transmission at central synapses’, Cell, 146(5), pp. 785–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A and Robitaille R (2016) ‘Astrocytic mGluR5 and the tripartite synapse’, Neuroscience. IBRO, 323(April), pp. 29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannasch U et al. (2014) ‘Connexin 30 sets synaptic strength by controlling astroglial synapse invasion’, Nature Neuroscience [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolicelli RC et al. (2011) ‘Synaptic pruning by microglia is necessary for normal brain development’, Science, 333(6048), pp. 1456–1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H et al. (2015) ‘Channel-mediated astrocytic glutamate modulates hippocampal synaptic plasticity by activating postsynaptic NMDA receptors’, Molecular Brain. BioMed Central Ltd, 8(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkhurst CN et al. (2013) ‘Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor’, Cell. Elsevier Inc, 155(7), pp. 1596–1609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual O et al. (2012) ‘Microglia activation triggers astrocyte-mediated modulation of excitatory neurotransmission’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G and Araque A (2007) ‘Astrocytes potentiate transmitter release at single hippocampal synapses’, Science, 317(5841), pp. 1083–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Alvarez A et al. (2014) ‘Structural and functional plasticity of astrocyte processes and dendritic spine interactions’, Journal of Neuroscience. Society for Neuroscience, 34(38), pp. 12738–12744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pita-Almenar JD et al. (2012) ‘Relationship between increase in astrocytic GLT-1 glutamate transport and late-LTP’, Learning and Memory [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pittà M et al. (2011) ‘A tale of two stories: Astrocyte regulation of synaptic depression and facilitation’, PLoS Computational Biology, 7(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puentes-Mestril C et al. (2019) ‘How rhythms of the sleeping brain tune memory and synaptic plasticity’, Sleep, 42(7), pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reemst K et al. (2016) ‘The indispensable roles of microglia and astrocytes during brain development’, Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10(November2016), pp. 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronzano R et al. (2020) ‘Myelin Plasticity and Repair: Neuro-Glial Choir Sets the Tuning’, Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience, 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]